De detectie van Lynch syndroom middels tumor analyse

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het optimale beleid voor moleculair onderzoek op populatieniveau naar Lynch syndroom en bij onverklaarde MMR-deficiëntie?

De uitgangsvraag omvat de volgende deelvragen:

- Wat is de opbrengst van standaard tumoronderzoek (IHC MMR) en aanvullend moleculair onderzoek naar Lynch syndroom op populatieniveau bij patiënten >70 jaar met darm- en baarmoederkanker?

- Is er uitbreiding nodig van standaard tumoronderzoek (IHC MMR) en aanvullend moleculair onderzoek naar Lynch syndroom bij patiënten met andere Lynch-geassocieerde tumoren (ovariumkanker, pancreascarcinoom, galweg- en galblaascarcinoom, urotheelcarcinoom, dunnedarmcarcinoom, maagcarcinoom, hersentumoren, talgkliertumoren) en prostaatcarcinoom en naar andere leeftijdsgroepen?

- Welke adviezen zijn optimaal voor onverklaard (unexplained) MMRd (UMMRd) patiënten?

Aanbeveling

Aanbeveling-1

Verricht voor de detectie van Lynch syndroom routinematig IHC van de MMR-eiwitten en/of moleculaire MSI-analyse bij de volgende tumoren gediagnostiseerd < 70 jaar:

- Adenocarcinoom van de dikke en dunne darm

- Endometriumcarcinoom

- Niet-sereus epitheliaal ovariumcarcinoom

- Urotheelcelcarcinoom van de hogere urinewegen

- Talgklier tumoren

Verricht voor de detectie van Lynch syndroom routinematig IHC van de MMR-eiwitten en/of moleculaire MSI-analyse bij de volgende tumoren gediagnostiseerd < 50 jaar:

- Adenocarcinoom van de alvleesklier of galwegen (inclusief papil van Vater) en galblaas

- Adenocarcinoom van de maag

- Urotheelcelcarcinoom van de blaas

Aanbeveling 2

Voor routinematig onderzoek naar aanwijzing voor Lynch syndroom voldoet IHC-analyse van MLH1, MSH2, PMS2 en MSH6. In laboratoria kan bij CRC en EC ook gekozen worden voor initieel IHC PMS2 en MSH6 met in 2e instantie bij afwijkende of onduidelijke kleuring ook MLH1 en MSH2 analyse.

In geval van immunohistochemisch MLH1 (en PMS2) verlies, dient bij de onderzochte tumoren <70 jaar aanvullend MLH1 promoter methylatie (PM) onderzoek in de tumor te worden gedaan.

Verwijs voor kiembaandiagnostiek <50 jaar:

- Bij afwezige kleuring van MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 en/of PMS2

Verwijs voor kiembaandiagnostiek 50-70 jaar:

- Bij afwezige kleuring van, MSH2, MSH6 en/of PMS2

- Bij afwezige MLH1 kleuring, tenzij sprake is van MLH1-PM.

Indien bij IHC-onderzoek (dat wordt ingezet om andere redenen dan Lynch syndroom detectie) >70 jaar afwijkende MMR-kleuring wordt gevonden, verwijs dan voor kiembaan diagnostiek:

- Bij afwezige kleuring van alleen (geïsoleerd) MSH6 of PMS2

In algemeen geldt dat buiten deze criteria een belaste voorgeschiedenis of familieanamnese een reden kan zijn om toch te verwijzen naar de klinische genetica, zie de flowchart en submodule Verwijscriteria voor klinisch genetisch onderzoek bij CRC en genpanelanalyse

NB: omdat het aantonen van Lynch syndroom soms gevolgen kan hebben voor chirurgische behandelkeuzes (subtotale colectomie of segmentresectie en bij vrouwen eventueel gelijktijdige preventieve operatie van uterus en/of ovaria, zie submodule Chirurgische behandeling van Lynch syndroom), moet in deze gevallen patiënt met spoed worden verwezen naar de Klinische genetica.

Gebruik voor het rapporteren van de IHC MMR uitslag door de pathologie de standaard teksten via PALGA.

Aanbeveling-3

Bij negatieve IHC MMR zonder MLH1-PM in de tumor en geen kiembaan MMR-defect dient aanvullend somatisch DNA-analyse van de MMR genen in de tumor gedaan te worden in patiënten met een leeftijd van diagnose <60 jaar of bij blijvende aanwijzing voor een mogelijk kiembaan MMR-gendefect vanwege een belaste voor- of familieanamnese zoals beschreven in de flowchart en submodule Verwijscriteria voor klinisch genetisch onderzoek bij CRC en genpanelanalyse.

In geval dat er geen kiembaan of somatische verklaring voor afwijkende IHC MMR en/of MSI-High profiel in de tumor wordt gevonden, spreekt men van onverklaard MMRd (UMMRd). Afhankelijk van leeftijd en familieanamnese kan bij sterke verdenking gemist Lynch syndroom, Lynch-syndroom advies worden gegeven, of als voldaan wordt aan FCC-criteria een FCC-advies (zie submodule Incidentie, risico’s en surveillance bij familiair colorectaal carcinoom, submodule Colorectaal kankerrisico en surveillance bij het Lynch syndroom en submodule Extracolonische kankerrisico en surveillance bij het Lynch syndroom), In andere gevallen is het advies deel te nemen aan het bevolkingsonderzoek voor darmkanker.

Overwegingen

Er is literatuuronderzoek gedaan naar de opbrengst van standaard en aanvullend moleculair (tumor)onderzoek naar Lynch syndroom op populatieniveau. De vraag werd gesteld of moleculair tumoronderzoek moet worden uitgebreid naar >70 jaar bij CRC en EC en naar andere Lynch-geassocieerde maligniteiten en prostaatkanker. Voor deze uitgangsvraag is voor darm-, baarmoedercarcinoom gebruik gemaakt van recente reviews en meta-analyses aangevuld met bij de commissie bekende relevante literatuur, voor de andere tumor typen is een analyse gedaan van studies van de afgelopen 10 jaar. Wat betreft adviezen voor onverklaard MMRd (UMMRD) cases is ook gebruikt gemaakt van recente reviews en meta-analyses aangevuld met bij de commissie bekende relevante literatuur.

Balans tussen gewenste en ongewenste effecten

Algemene tekst

Lynch syndroom is de meest voorkomende vorm van erfelijke darmkanker, waarbij ook een verhoogd risico op baarmoederkanker en in mindere mate ook op andere vormen van kanker aanwezig is. Dit syndroom erft autosomaal-dominant over. Het wordt veroorzaakt door kiembaan pathogene varianten (PV) in genen betrokken bij een DNA-herstel systeem, genaamd mismatch repair (MMR). De genen waar het om gaat zijn MLH1, MSH2, PMS2 en MSH6. Deleties van het EPCAM-gen kunnen ook leiden tot MSH2 functieverlies en daarmee Lynch syndroom. Bij het MMR-systeem zijn nog meer eiwitten betrokken, maar tot nu toe is niet duidelijk aangetoond dat mono-allelische varianten in deze genen ook leiden tot een hoger kanker risico. Wel is er voor MSH3 en MLH3 bekend dat bi-allelische mutatie dragers een verhoogd risico hebben op onder andere polyposis. Hier wordt in de submodule over genetische testen bij adenomateuze polyposis (zie submodule Genetische testen bij adenomateuze polyposis) kort ingegaan. De dragerschapsfrequentie in de bevolking van één van de vier vormen van Lynch syndroom is 1 op 274 (Win, 2017); voor de individuele genen is dit: MLH1: 1 op 1,946, MSH2: 1 op 2,841, MSH6: 1 op 758, PMS2: 1 op 714.

In een cel treedt verlies van het MMR-systeem op als een of meerdere MMR-eiwitten niet meer worden aangemaakt. Dit gebeurt als beide gen kopieën coderend voor het betreffende MMR-eiwit worden uitgeschakeld. Uitschakeling van een gen in een tumor kan worden veroorzaakt door (i) een constitutionele (kiembaan) PV, (ii) een somatische PV, (iii) somatische uitschakeling door methylatie van de promotersequentie (iv) kiembaan uitschakeling door promoter methylatie (v) of verlies van het hele allel (LOH) waar het gen op ligt. Bij iemand met een kiembaan PV (Lynch syndroom) is er alleen uitschakeling van de tweede gen kopie nodig voordat MMR-deficiëntie ontstaat -bij iemand zonder kiembaan PV moeten in beiden gen kopieën nieuwe events optreden.

Technieken om MMR-deficiëntie aan te tonen zijn moleculaire microsatelliet (MSI) analyse en immunohistochemisch onderzoek van de MMR-eiwitten (IHC MMR). Beide technieken zijn vergelijkbaar wat betreft het opsporen van Lynch syndroom. Voor routinematig screenen van tumoren voor Lynch syndroom werd in de richtlijn van 2015 immunohistochemisch onderzoek geadviseerd, omdat dit goedkoper en sneller is en daarbij makkelijker te implementeren in ieder pathologisch laboratorium. Wel wordt het traditionele MSI-onderzoek met gebruik van met name voor darm- en baarmoederkanker gevalideerde markers in toenemende mate vervangen door op NGS gebaseerde MSI-analyse. Zie ook de landelijke richtlijn darmkanker Richtlijn colorectaal carcinoom voor beschrijving MMR/MSI onderzoek bij CRC.

Sinds 2015 is het in Nederland standaard beleid om in elke darmkanker (CRC) en baarmoederkanker (EC) bij patiënten onder de 70 jaar na te gaan of er sprake is van mismatch repair deficiëntie (MMRd) middels immunohistochemisch onderzoek (IHC MMR) van de tumor. Indien er geen aankleuring is van 1 of 2 van de MMR-eiwitten, en er in geval van afwezige kleuring van MLH1 en PMS2 geen methylatie van de MLH1 promoter aanwezig is in de tumor, is er indicatie om na te gaan of sprake is van een kiembaan pathogene variant in één van de MMR genen via de klinisch geneticus. Door dit beleid is het aantal families met de diagnose Lynch syndroom toegenomen.

Inmiddels is er een andere belangrijke reden voor MMR-deficiëntie (MMRd)-onderzoek bij gekomen. Het is namelijk ook van belang de MMR-status van tumoren te weten omdat behandelkeuzes hiervan af kunnen hangen: MMRd tumoren (zowel bij sporadisch als in het kader van Lynch syndroom) kunnen gevoeliger zijn voor immuuntherapie en minder voor reguliere chemotherapie. Veel laboratoria doen daarom inmiddels ook MMRd-analyse middels IHC MMR of moleculair onderzoek bij CRC en EC-patiënten >70 jaar en andere tumoren. Een richtlijn voor informatie en informed consent bij moleculaire tumor diagnostiek en een leidraad voor verwijzing voor kiembaan diagnostiek bij het vinden van een aanwijzing voor een erfelijke aanleg voor kanker zijn ontwikkeld, zie ook: Erfelijke-aanleg-voor-kanker. Deze submodule richt zich op de rol van tumordiagnostiek bij de detectie van Lynch syndroom.

De vraag nu is wat de opbrengst van MMRd-analyse in verschillende leeftijdsgroepen en tumortypen is en of een aanpassing van het huidige richtlijn advies nodig is. Ook is de vraag in hoeverre kiembaan en/of somatische MMR-gen analyse verricht moet worden indien MMRd in een tumor wordt aangetoond en wat het beleid is indien de MMRd onverklaard (UMMRd) blijft.

Technieken om MMR-deficiëntie op te sporen

Voor de detectie van mismatch repair deficiëntie kan immunohistochemische kleuring (IHC) van de MMR-eiwitten MLH1, PMS2, MSH2 en MSH6 verricht worden. Omdat MLH1- en MSH2-deficiëntie praktisch altijd samengaat met respectievelijk PMS2- en MSH6-verlies, kan eerst PMS2- en MSH6-kleuring worden verricht. Bij een verlies van aankleuring volgt kleuring van MLH1 en MSH2, mede om te bepalen of MLH1-promoter-methylatieonderzoek nodig is en als aanwijzing welk gen meest waarschijnlijk aangedaan is. Een twee-antilichaam MMR-teststrategie leidt niet tot significante fouten in de identificatie van dMMR en bespaart kosten, zoals aangetoond in meerdere Nederlandse studies (Stello, 2017; Post, 2021; Vink-Börger, 2024). Ook Snowsill (2020) bevestigde de betrouwbaarheid en kosteneffectiviteit van deze aanpak.

IHC-evaluatie van MMR-eiwitten is niet altijd eenvoudig. Interpretatie is afhankelijk van de expertise van de patholoog en de kwaliteit van technieken en materialen. Uitdagend zijn de interpretatie van heterogene of subclonale kleuringspatronen, en zwakkere kleuring intensiteiten, die ten onrechte geduid kunnen worden als intacte MMR-expressie. De sensitiviteit van IHC-MMR kan afnemen door somatische of kiembaan missense-mutaties, die leiden tot een weliswaar stabiel eiwit met behouden antilichaambinding, maar zonder MMR-functie. Bou Farhat (2024) toonde aan dat bij 1% van de CRC/EC's dMMR wordt gemist bij gebruik van alleen IHC-MMR. Zij pleiten voor NGS in de diagnostiek, al lijken de resultaten overschat door methodologische beperkingen. Hechtman (2020) rapporteerde dat in 6% van de MMRd-patiënten (door kiembaan- of somatische mutaties) intacte MMR-kleuring aanwezig was, voor de praktijk zou dit dan kunnen betekenen dat rond de 0,5% van MMRd EC en CRC worden gemist met standaard IHC MMR in deze groepen tumoren. Deze 6% intacte kleuring in MMRd patiënten is echter mogelijk ook een overschatting. Singh et al. geven in antwoord op dit onderzoek aan dat niet alleen volledige afwezigheid van kleuring, maar bijvoorbeeld ook heterogene kleuring of ‘dot-like nuclear kleuring’ reden is tot verder onderzoek (Singh 2021).

Bij moleculaire MSI-analyse wordt gekeken naar microsatellieten, korte repetitieve DNA-sequenties. Bij een defect MMR-systeem zal de lengte van microsatellieten gaan variëren, wat leidt tot MSI (van Lier, 2010). Waar in het verleden gebruik werd gemaakt van fragmentlengte-analyse van vijf gestandaardiseerde markers (klassieke pentaplex-MSI), wordt MSI-analyse tegenwoordig doorgaans verricht via NGS-analyse van veel meer markers, zeker als het onderdeel is van een veel bredere moleculaire analyse van de tumor. Hoewel de MSI-test een belangrijk alternatief blijft voor IHC bij MMRd-detectie, is deze in algemene zin duurder, duurt de uitslag langer en is de test minder breed toepasbaar in pathologie laboratoria.

Conclusie: IHC-MMR en MSI-tests blijven relatief gevoelige, snelle en kosteneffectieve methoden voor MMRd-detectie en Lynch syndroom screening.

MLH1 promoter methylatie (PM) in tumor en kiembaan

MLH1-PM komt voor in 4-10% van alle CRC en 18-20% van de EC (Eikenboom, 2022, Ryan, 2019; Loong, 2024), neemt sterk toe met leeftijd en is sterk geassocieerd met een BRAF hotspot mutatie, rechtszijdig CRC, bepaalde histologische kenmerken en vrouwelijk geslacht (Advani, 2021; Christenson, 2023). Bijna altijd gaat het om een somatisch, nieuw ontstane verandering. Het is daarom wenselijk dat alvorens bij afwezige MLH1 (en PMS2) kleuring in een tumor kiembaan diagnostiek te adviseren, eerst MLH1-PM analyse wordt verricht.

In een klein deel van de met name jonge patiënten kan sprake zijn van kiembaan of post zygotisch MLH1-PM, vaak in mozaïek (Hitchins, 2023). Deze mensen hebben een verhoogde kans op nogmaals tumorvorming en het is daarom belangrijk om dit te weten voor vervolg controles. Vaak ontstaat deze kiembaan MLH1-PM de-novo als gevolg van een "primaire epimutatie" zonder duidelijke genetische basis; dragers hebben daarom meestal geen aangedane familiegeschiedenis. Er kan echter ook sprake zijn van een onderliggende variant in de MLH1 promoter regio, waarbij familieleden wel een verhoogde kans hebben op ook kiembaan MLH1-PM.

Het voorkomen MLH1-PM in de kiembaan (constitutional MLH1 promoter methylation) betreft in ongeselecteerde CRC-cohorten ongeveer 0,6-1,0% van alle mensen met een negatieve IHC MLH1, (Ward, 2013; Castillejo, 2015; Pearlman, 2017; Zyla, 2021; Niessen, 2009; Joo, 2023; Helderman, 2024). In cohorten geselecteerd op jonge leeftijd en familiegeschiedenis ligt dit tussen de 4 tot 16% (Castillejo, 2015; Niessen, 2009; van Roon, 2010; Pineda, 2012; Crucianelli, 2014 Goel, 2011) met diagnose-leeftijd variërend tussen de 18-60 jaar. De Amerikaanse studie uit 2023 van Hitchins (2023) beschrijft een analyse in 2 population-based, ongeselecteerde cohorten van respectievelijk 1,566 en 3310 CRC waar in 105 (6,7%) en 281 (8.5%) CRCs respectievelijk MLH1-PM was aangetoond in de tumor. In deze studie werd vervolgens, indien DNA beschikbaar was voor verder onderzoek, MLH1 kiembaan PM aangetoond in respectievelijk 4% (4/95) en 1.4% (4/281). Op één na (een man met CRC op 74 jaar) waren al deze patiënten met kiembaan MLH1-PM 55 jaar of jonger. Ondanks dat kiembaan (post-zygotisch) MLH1-PM zeldzaam is in het totale cohort, is het frequent aanwezig in CRC met MLH1 PM < 50 jaar. Een eerdere studie uit 2021 is onderdeel van dit cohort en wordt niet apart besproken (Pearlman, 2021). In het eerste cohort waren er 10 van de 105 (9,5%) gevallen met MLH1-PM < 60 jaar; In het tweede grotere cohort was dit 35 van de 281 (11%). Het testen van deze patiënten met MLH1-PM in de tumor op kiembaan MLH1-PM geeft een detectie ratio van 16% (7/45). In de leeftijdsgroep 55-59 jaar is dit echter slechts 1 op de 21. De auteurs stellen daarom voor om de leeftijdsgrens voor kiembaan analyse op 55 jaar te stellen. In een Nederlandse studie is ook maar één keer kanker op 60-jarige leeftijd gevonden (van Roon, 2010). Ook is beschreven dat MLH1-PM en kiembaan MMR-varianten elkaar niet uitsluiten (Helderman, 2024), dus dat MLH1-PM de 2e hit in de tumor is. Het lijkt daarom voor nu raadzaam om ook bij het detecteren van MLH1-PM in de tumor te verwijzen voor kiembaan MLH1-PM en MLH1 DNA-onderzoek bij darmkankerpatiënten met een leeftijd van diagnose <50 jaar naast andere factoren die wijzen op een mogelijk MMR-gendefect.

Er is meer onderzoek nodig om te zien of deze leeftijdgrens van <50 jaar sensitief genoeg is. Om die reden is hierover ook een kennisvraag geformuleerd.

Over het voorkomen van kiembaan MLH1-PM in geval van EC en andere tumoren zijn nog weinig data beschikbaar. Een kleinere studie beschrijft drie losse patiënten met EC met MLH1 kiembaan PM en daarnaast een EC-cohort studie (bestaande uit twee verschillende population-based cohorten van EC-patiënten met MLH1-PM) waarin één patiënt met een laag-niveau mozaïek MLH1-PM werd aangetoond. Dit komt neer op 2% van de patiënten onder 60 jaar (1/45 EC met MLH1-PM) en 17% (1/6 met MLH1-PM) van de patiënten onder/gelijk aan 50 jaar (Hitchins, 2023). Daarnaast is beschreven dat MLH1-PM ook bij EC voor kan komen bij patiënten met een onderliggend MMR-kiembaan defect (Helderman, 2024). Van belang is wel dat MLH1-PM veel vaker voorkomt bij EC dan bij CRC, ook onder de 60 jaar (Kahn, 2019, Loong, 2024; Andersson, 2024; Kaya, 2024). Voor andere tumoren is niet goed bekend hoe vaak MLH1-PM voorkomt en hoe vaak dit kiembaan methylatie betreft. Voor nu is, gezien ook de kleine aantallen en ten behoeve van de uniformiteit het voorstel om alle Lynch geassocieerde tumoren met MLH1-PM <50 jaar door te verwijzen voor aanvullend MLH1-PM onderzoek in kiembaan/ normaal weefsel en onderzoek naar een eventueel onderliggend MMR-defect, omdat MLH1-PM ook een second hit kan zijn of los kan staan van onderliggend MMR-kiembaan defect.

De opbrengst van tumoronderzoek naar Lynch syndroom bij patiënten met Lynch geassocieerde maligniteiten

MMRd-analyse in andere tumoren dan darm-/baarmoeder kanker voor de detectie van Lynch syndroom

In toenemende mate wordt MMRd-analyse verricht in het kader van het afstemmen van behandeling. Hierbij wordt met enige regelmaat MMRd gevonden in andere tumoren dan CRC en EC, waarbij de vraag rijst of er kiembaan diagnostiek verricht moet worden en of MMRd analyse niet ook routinematig in andere tumoren dan CRC en EC verricht zou moeten worden. Een studie door Latham (2019) heeft MSI en IHC-analyse verricht in 15,054 patiënten met meer dan 50 verschillende carcinomen en laat zien dat 50% van de gedetecteerde Lynch syndroom patiënten (met een bewezen kiembaan mutatie) carcinomen heeft anders dan colorectaal of endometriumcarcinoom.

In de literatuur werd gezocht naar prevalenties van MMRd of MSI-H en MMRd gerelateerd aan MLH1 promoter methylatie, kiembaan mutaties, somatische mutaties en onverklaarde MMRd van de diverse tumorsoorten. In eerste instantie werden per tumortype systematische reviews en meta-analyses geselecteerd. Dit is vervolgens aangevuld met cohortstudies voor de tumortypen waarvoor geen meta-analyses beschikbaar waren. Alle geselecteerde onderzoeken beschreven per tumortype, al dan niet volledig, de prevalentie van afwijkende IHC-MMR en/of MSI-H, MLH1-PM, Lynch syndroom en somatische varianten. Een samenvatting hiervan is gegeven in tabel 2.

Ovarium kanker:

Op basis van de meta-analyse van Mitric (2023) kan geconcludeerd worden dat 6% van de ovariumtumoren een MMRd profiel laat zien afhankelijk of immunohistochemie of moleculaire MSI is verricht. In endometroïd type ovariumcarcinoom, de meest voorkomende vorm van ovariumcarcinoom bij Lynch syndroom, toont zowel immunohistochemisch als moleculair 12% van de tumoren een MSI-profiel, in sereuze tumoren is dat 1% (Mitric 2023).

Afhankelijk van type ovariumtumor wordt in 1-3% Lynch syndroom aangetoond, waarbij het minst frequent in sereus type ovariumcarcinoom, wat de meest voorkomende vorm van ovariumcarcinoom is. Alle ovariumcarcinomen worden in het kader van tumor first diagnostiek voor een BRCA aanleg moleculair getest, Het meest doelmatig lijkt echter om alleen in niet-sereuze ovariumcarcinomen moleculaire MSI of IHC MMR analyse te verrichten. Omdat bij 76% van de MSI-H tumoren, met een MLH1-profiel, sprake was van methylatie van de MLH1 promoter moet MLH1-PM eerst uitgesloten worden, voordat de patiënt verwezen wordt naar de klinische genetica voor kiembaan diagnostiek, tenzij sprake is van MLH1-PM <50 jaar.

Pancreas, galblaas, galweg (inclusief papil van Vater) kanker:

Waarschijnlijk kan in ongeveer 5% van de pancreas en galweg-, galblaas adenocarcinomen IHC dMMR worden aangetoond, hoewel bij galblaaskanker zelden een MMRd profiel lijkt te worden gevonden. In totaal wordt bij ongeveer 1% Lynch syndroom aangetoond. Deze getallen stijgen naarmate leeftijd van diagnose jonger is; 2,8-4,5% bij diagnose <50 jaar. Routinematig verrichten van IHC dMMR lijkt daarom doelmatig bij diagnose <50 jaar. Hoewel data beperkt zijn, lijkt ook methylatie van de MLH1-promoter bij deze tumoren in de tumor verantwoordelijk te kunnen zijn voor een MLH1-profiel. Indien sprake is van MLH1-PM <50 jaar lijkt verwijzing naar de klinische genetica op dit moment wel zinvol.

Urotheel cel carcinoom hogere urinewegen en blaas:

Op basis van de huidige gegevens komt bij waarschijnlijk 5-10% van de hogere urineweg urotheelcel carcinomen (UTUC) dMMR en/of MSI voor en wordt in ongeveer de helft daarvan een kiembaan PV gevonden met name in MSH6 of MSH2. Omdat naar verwachting ook bij deze tumoren de kans op een kiembaan aanleg afneemt met toenemende leeftijd, lijkt het doelmatig om IHC MMR te verrichten in alle UTUC gediagnostiseerd <70 jaar. Methylatie van de MLH1-promoter is ook bij deze tumoren beschreven en dient uitgesloten te zijn bij een MLH1-profiel in de tumor, alvorens te verwijzen voor kiembaan diagnostiek, tenzij er sprake is van MLH1-PM <50 jaar.

Gezien het veel frequenter voorkomen van blaas urotheelcelcarcinoom (BUC), met een lage frequentie van MMRd (1,5%) en Lynch syndroom (1%), wordt routinematig MMRd analyse in BUC niet doelmatig geacht, tenzij dit op ongebruikelijk jonge leeftijd (<50 jaar) voor komt.

Dunne darmkanker en maagkanker:

Op basis van de beschikbare studies heeft 20-30% van de adenocarcinomen van de dunne darm een MMRd profiel met name die in het duodenum. In 5-10% wordt een kiembaan aanleg voor Lynch syndroom aangetoond. Gezien de zeldzaamheid van de tumor kan overwogen worden routinematig IHC MMR analyse te doen in alle dunne darmtumoren, maar dit dient in ieder geval bij diagnose <70 jaar te gebeuren. Omdat bij afwijkende aankleuring MLH1/PMS2 regelmatig methylatie van de MLH1-promoter gerapporteerd is, dient, alvorens te verwijzen naar de klinische genetica voor kiembaan diagnostiek eerst MLH1-PM in de tumor uitgesloten te zijn bij dit profiel, tenzij er sprake is van MLH1-PM <50 jaar.

Ongeveer 10% van de adenocarcinomen van de maag vertonen IHC dMMR. Echter, op basis van de beperkte data wordt slechts bij ongeveer 1% Lynch syndroom aangetoond. Routinematige MMRd-analyse voor de detectie van Lynch syndroom lijkt bij maagkanker daarom op dit moment alleen geïndiceerd wanneer deze op ongebruikelijk jonge leeftijd (<50 jaar) gediagnostiseerd wordt.

Hersentumoren:

Bij Lynch syndroom kunnen gliale hersentumoren voorkomen. Rodriguez-Hernández (2013) beschrijven dat IHC MMR eiwit expressie afwijkingen frequent (43%) voorkomen in laag- en hooggradige astrocytomen. Met moleculaire MSI-analyse wordt aanzienlijk minder MSI aangetoond. Ook Hadad (2023) vinden maar in 2% van glioblastomen MSI. Zowel IHC van de MMR-eiwitten als MSI is in de praktijk lastig te interpreteren. Het is ook bijzonder dat deze studie naast methylatie van de MLH1-promoter ook methylatie van de MSH2- en MSH6-promoter meldt, welke ook niet overeenkomt met het IHC-profiel van deze tumoren. Meest waarschijnlijk is de frequentie van 43% zoals gevonden door Rodriquez-Hernandez een sterke overschatting. In 1-5% van de gliale hersentumoren bleek sprake van Lynch syndroom. Op basis de huidige data is routinematig testen van gliale hersentumoren op MSI voor de detectie van Lynch syndroom niet aan de orde.

Talgkliertumoren:

Talgkliertumoren horen bij het tumor spectrum van Lynch syndroom, voorheen benoemd als Muir-Torre syndroom. In Nederland komen ongeveer 200 patiënten met een adnextumoren van de huid (waaronder talgkliertumoren) per jaar voor, waarvan 50 onder de 70 jaar (IKNL, 2022-2023). Takliertumoren worden ingedeeld in talgklieradenomen, talgklierepitheliomen (=sebaceoma) en talgkliercarcinomen. De ligging wordt verdeeld in (1) perioculair/ooglid en extraoculair (Ferreira, 2020).

Twee studies lieten zien dat MMR-deficiëntie in 30- 50% van de onderzochte talgkliertumoren voorkwam (Cook 2023, Kataapuram 2023). In de laatste studie werd in 15% Lynch syndroom aangetoond, maar in deze studie betrof dit wel een mogelijk geselecteerde groep aangezien maar in een deel verdere diagnostiek verricht werd.

Over het algemeen zijn talgklieradenomen en extra-oculaire laesies vaker MMR deficiënt, maar de frequentie van Lynch syndroom is in alle talgklier tumoren >10% (Gaskin, 2011; Sinson, 2023; Singh, 2008). Dit percentage zal waarschijnlijk lager liggen in de oudere leeftijdsgroepen, maar dit is niet uitgebreid onderzocht. Gezien de huidige data en omdat het een vrij zeldzame tumor betreft, lijkt het doelmatig in ieder geval routinematig IHC MMR te verrichten bij diagnose <70 jaar. Bij de casus boven de 70 jaar kan alsnog IHC MMR en/of kiembaan analyse ingezet worden in geval van een talgklieradenoom, een extra-oculaire ligging, een voorgeschiedenis van Lynch geassocieerde tumoren en/of belaste familieanamnese. Er zijn beperkt data in hoeverre methylatie van de MLH1-promoter voorkomt, maar dit lijkt zeldzaam; wel zijn enkele casus beschreven met kiembaan MLH1-PM (tussen 45-55 jaar) en dit moet overwogen worden in patiënten onder de 50 jaar (Walker, 2023; Zyla, 2021).

Prostaatkanker:

MSI is zeldzaam in prostaatkanker (3% of minder) en Lynch Syndroom nog zeldzamer. Mede gezien het een veel voorkomende tumor betreft, is er geen plaats voor routinematig testen van prostaatkanker op MMRd. Indien MMRd niet-routinematig wordt aangetoond, kan de leidraad voor verwijzing bij aanwijzing voor erfelijke aanleg voor kanker na tumor diagnostiek (www.artsengenetica.nl) gebruikt worden om te bepalen of verwijzing voor kiembaan diagnostiek geadviseerd wordt.

De opbrengst van tumoronderzoek naar Lynch syndroom bij patiënten met darmkanker en baarmoederkanker.

Colorectaal carcinoom (CRC)

Een Nederlandse studie van Vos (2020) liet de opbrengst zien van universeel IHC MMR en kiembaan analyse in een prospectief Nederlands cohort. In 3602 nieuw gediagnosticeerde CRCs jonger dan 70 jaar uit 19 ziekenhuizen, werd onderzoek gedaan naar MMR-deficiëntie (MMRd), MLH1-promoter methylatie (MLH1-PM), kiembaan en biallelische somatische MMR-events. De opbrengst werd geëvalueerd met behulp van gegevens uit het Nederlands Pathologie Register (PALGA) en twee regionale genetische centra. Pathologen pasten routinematig MMR-testen toe bij 84% van de CRCs en 10% bleek MMRd, waarvan 8% MLH1/PMS2 gerelateerd, grotendeels als gevolg van somatische MLH1-PM (66%). Van de patiënten met MMRd CRC zonder MLH1-PM werd 69% doorverwezen voor kiembaan diagnostiek, waarvan 55% verklaard werd door Lynch syndroom en 43% door somatische biallelisch MMR-events. De prevalentie van Lynch syndroom was 18% in CRC <40 jaar, 1,7% in CRC tussen de 40-64 jaar en 0,7% in CRC tussen de 65-69 jaar. De meeste gevallen met een dMMR tumor werden gevonden in de leeftijd 65-69 jaar, waarbij dMMR als gevolg van somatische oorzaken (13%) 20 keer vaker voorkwam dan het Lynch syndroom. In deze studie concluderen de auteurs dat tot de leeftijd van 65 jaar routinematige diagnostiek van (niet-) erfelijke oorzaken van dMMR CRCs effectief het Lynch syndroom identificeert en onverklaarde MMRD-diagnose vermindert. Boven de leeftijd van 64 jaar is de kans op Lynch syndroom echter klein.

Een meta-analysis in 2022 (Eikenboom, 2022) keek naar het aandeel patiënten met Lynch syndroom, met een sporadische MMRd tumor en onverklaarbare gevallen van MMRd-tumoren (UMMRd) in 58.580 niet-geselecteerde CRCs. Ongeveer 1 op de 10 CRCs had een MMR-deficiëntie, dit werd in ongeveer de helft verklaard door MLH1-promoter methylatie (MLH1-PM). Van alle patiënten met MMRd, die kiembaan genetisch onderzoek ondergingen, werd bij 38% een pathogene MMR-kiembaanvariant geïdentificeerd. In 2% van alle CRCs werd een kiembaan MMR pathogene variant (PV) aangetoond. Dit percentage steeg tot 7% en 5% van alle CRCs bij patiënten jonger dan respectievelijk 50 en 70 jaar. Verder werd duidelijk dat het percentage biallelische somatische events of kiembaanvarianten afhankelijk is van het specifieke MMR-eiwit dat ontbreekt bij kleuring. Voor MSH6 en PMS2 wordt de afwijkende eiwitkleuring vaker verklaard door een kiembaan PV voor dan voor MLH1 en MSH2. In 4% van het totale cohort werd geen verklaring voor de MMRd gevonden. Dit percentage bevat waarschijnlijk veel sporadische MMR-deficiënte CRCs omdat in meeste studies geen somatische test gedaan is. Volledige diagnostiek leidde tot een percentage onverklaarde MMRd (UMMRd) van slechts 0,6%.

Een retrospectieve cohortstudie van Christonson (2023) onderzocht 544 CRCs met next-generation sequencing en mismatch repair (MMR)-analyse. Ze vergeleken moleculaire en klinische kenmerken van 251 patiënten met CRC gediagnostiseerd tussen de 50-69 jaar en 60 patiënten met CRC >80 jaar. CRC kwam vaker rechtszijdig voor (82% vs. 35%), toonde vaker MMR-deficiëntie (35% vs. 8%) en BRAF p.V600E-mutaties (35% vs. 8%), maar toonde minder vaak stadium IV-ziekte (15% vs. 28%) en APC-mutaties (52% vs. 78%) in de groep >80 jaar. De toename van MMR-deficiëntie bij oudere patiënten werd vooral gezien bij vrouwen (48% vs. 10% bij mannen). BRAF p.V600E-mutaties kwamen vaker voor bij MMR-deficiënte CRC op latere leeftijd (67%). De conclusie van deze studie is dat CRC op latere leeftijd wordt gekenmerkt door een hogere frequentie van MMR-deficiëntie en BRAF p.V600E-mutaties, vooral bij vrouwen.

McRonald (2024) analyseerden de nationale dataset van de “National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service (NCRAS)”. Van alle patiënten met colorectale kanker (CRC), die in 2019 in Engeland werden gediagnosticeerd, werden uitslagen van dMMR-analyse (via immunohistochemie of microsatelliet instabiliteit), MLH1-promoter methylatie (MLH1-PM) en BRAF status, en kiembaan analyse van de MMR genen geïnventariseerd. Van de 8000 geteste CRC-patiënten waren 6000 bij diagnose ≤70 jaar oud. Slechts 44% van de CRCs werd getest op mismatch repair-deficiëntie (dMMR); 16% daarvan vertoonde dMMR of microsatellietinstabiliteit (MSI). Van deze dMMR/MSI-gevallen onderging slechts 51% verdere diagnostische tests. Van de MLH1-deficiënte tumoren had 67% (275/413) MLH1-PM. Slechts 1,3% van alle CRC-patiënten onderging een kiembaan (germline) MMR-genetische test; tot 37% van deze tests werd uitgevoerd buiten de NICE-richtlijnen. Van de dMMR-gevallen zonder MLH1-PM had 49% (103/210) een kiembaan pathogene variant (PV) in een MMR-gen, waarvan 25 in MLH1. Concluderend werd een aanzienlijk deel van de CRC-patiënten niet getest op dMMR of onderging geen verdere diagnostiek. Daarnaast werden veel kiembaan MMR-tests buiten richtlijnen uitgevoerd.

Abu-Ghazaleh (2022) deden een systematische review en meta-analyse van de literatuur in MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase en Web of Science om de prevalentie van Lynch syndroom in CRC-patiënten te berekenen. In totaal werden 51 studies geanalyseerd. De geschatte prevalentie van Lynch syndroom was 2,2% op basis van alle detectiemethoden. Studies die kiembaan (germline) tests uitvoerden op alle CRC-patiënten vonden een hogere prevalentie (5,1%) dan studies die alleen kiembaan tests deden bij patiënten met mismatch repair-deficiëntie (1,6%) of microsatellietinstabiliteit (1,1%). Echter, de hogere prevalentie bij directe kiembaan analyse is waarschijnlijk overschat omdat veel studies vooraf hoog-risicopatiënten selecteerden. Studies die CRC-patiënten ouder dan 75 jaar includeerden, rapporteerden een lagere Lynch syndroom-prevalentie (1,7% [95% CI = 1,3%–2,1%]) dan studies zonder deze oudere patiënten (4,4% [95% CI = 3,2%-5,5%]). Concluderend varieert de geschatte prevalentie van Lynch syndroom afhankelijk van de screeningsmethode en hebben oudere CRC-patiënten (>75 jaar) een lagere detectiekans van Lynch syndroom.

Kunnackal (2022) voerden een systematische review van alle publicaties in de MEDLINE-database tussen 2005 en 2017 uit om de effectiviteit van universele screening voor Lynch syndroom en de detectie van kiembaanmutaties in mismatch repair (MMR)-genen bij verschillende Lynch syndroom -gerelateerde tumoren te analyseren. De opbrengst van Lynch syndroom -screening en MMR-kiembaanmutaties verschilde significant per type tumor (p < 0.001) en was in endometriumkanker (EC) respectievelijk 22,65% en 2,6% en in colorectale kanker (CRC) 11,9% en 1,8%. Lynch syndroom -screening in EC detecteerde significant meer biallelische somatische events dan in CRC (16,94% vs. 5,23%, p < 0.0001). Routine Lynch syndroom -screening wordt aanbevolen voor meerdere tumortypen, maar er zijn geen gegevens over de invloed van leeftijd op de detectie van kiembaanmutaties.

West (2021) beschrijft een prospectieve studie, waarin alle nieuw gediagnosticeerde CRC van 50 jaar of ouder werd verwezen voor Lynch syndroom screening. De testen bestonden uit immunohistochemie voor MLH1, PMS2, MSH2 en MSH6, gevolgd door BRAF-mutatieanalyse ± MLH1-promotermethylatie (MLH1-PM) testen in gevallen die MLH1-verlies vertoonden. 15% van de patiënten vertoonden dMMR. 95% van de MLH1-deficiënte tumoren vertoonden MLH1-PM. Van de patiënten die in de uiteindelijke analyse waren opgenomen, hadden 81 (2,9%) een indicatie voor kiembaananalyse.

Endometriumcarcinoom (EC)

Een meta-analysis van Ryan (2019) bekeek 53 studies, waaronder 12.633 EC-patiënten. Het totale aandeel endometriumtumoren met microsatellietinstabiliteit of MMRd bij immunohistochemisch onderzoek was respectievelijk 0,27 (95% [CI] 0,25-0,28, I2: 71%) en 0,26 (95% CI 0,25-0,27, I2: 88%). Van de vrouwen met abnormale tumortesten had 0,29 (95% CI 0,25-0,33, I2: 83%) een kiembaan MMR-gen PV, zodat ongeveer 3% van de EC’s kan worden toegeschreven aan Lynch syndroom

Kunnackal John (2022) adviseert een verschillend beleid bij CRC en EC vanwege het feit dat MMR-deficiëntie bij EC veel vaker wordt verklaard door somatische events, namelijk om in die groep te beginnen met DNA-analyse in de tumor en niet in de kiembaan. Dit leidt echter tot minder eenduidige aanbevelingen met mogelijk juist weer averechts effect.

Kahn (2019) and Gordhandas (2020) identificeerden uit 29 geïncludeerde studies 6649 patiënten met endometriumkanker, waarvan 206 (3%) Lynch syndroom bleken te hebben. Van de patiënten had 28%-31% MMRd of MSI. De geschatte prevalentie van Lynch syndroom was 15% bij afwijkende IHC en 19% bij een MSI-high profiel; 13,7% van de MLH1-defiënte tumoren vertoonde geen promoter methylatie (PM), waarvan 32 (2.8% uit de gehele groep, 22,4% van de MLH1-deficiënte casus) een kiembaanvariant in MLH1 hadden. Screening op alleen familiegeschiedenis zou 43% van de Lynch syndroom gevallen hebben gemist. Patiënten met Lynch syndroom waren jonger (51,1 jaar), hadden een lager BMI en werden minder vaak in stadium I gediagnosticeerd. MLH1-PM patiënten waren gemiddeld ouder.

Jumaah (2021) heeft in een systematische review de prevalentie van MMRd bij endometriumkanker (EC) onderzocht in 25 studies met in totaal 7.459 patiënten. Een meta-analyse met een random-effect model berekende een totale MMRd frequentie van 24,5% (95% BI: 21,0%-28,1%). Bij Lynch syndroom was de MMRd frequentie 22,9% (95% BI: 14,9%-32,1%). Type I EC had een hogere MMRd (25,8%) dan type II (13,7%). MMRd was het hoogst bij stadium I-II (79,4%) en graad I-II (65,7%), en het laagst bij stadium III-IV (20,2%) en graad III (21,5%). Odds ratio’s toonden associaties met laag stadium EC (1,57), lymfovasculaire invasie (1,77) en diepe myometriuminvasie (1,27).

Loong (2024) verrichtten een retrospectieve, nationale, populatie-studie in de “English National Cancer Registration Dataset”. Ze includeerden alle endometriumcarcinomen (EC) gediagnostiseerd in 2019 en onderzochten frequentie en uitkomst van MMRd-analyse en kiembaan analyse van de MMR-genen. Van alle patiënten was 44% (3514/7928) ouder dan 70 jaar. Bij 17,8% (1408/7928) van de EC in 2019 werd immunohistochemie (IHC)- of microsatellietinstabiliteit (MSI)-analyse verricht; 31% (431/1405) van de geteste tumoren vertoonde MMRd; 80% (346/431) van de MMRd-tumoren was MLH1-negatief en/of MSI-positief; 43,1% (149/346) van de MLH1-negatieve/MSI-positieve tumoren onderging een MLH1-promoter methylatie (PM) test, waarvan 85% (126/149) methylatie vertoonde (MLH1-PM). Van de patiënten met EC die in aanmerking kwamen voor kiembaanonderzoek, kreeg 25% (26/104) een kiembaan MMR-test, waarbij 15 patiënten Lynch syndroom bleken te hebben. Concluderend laat deze studie zien dat slechts een klein percentage EC-patiënten in 2019 werd getest op MMRd en MLH1-PM.

Andersson (2024) screenden 221 EC gediagnostiseerd tussen 2008 en 2012 op het verlies van mismatch repair (MMR)-eiwitten via immunohistochemie (IHC) en het voorkomen van kiembaan MMR-gen pathogene varianten (PV); 24,4% (54/221) van de tumoren vertoonde verlies van ten minste één MMR-eiwit. De gemiddelde diagnoseleeftijd was 68,3 jaar in de MMR-deficiënte groep versus 65,3 jaar in de groep met normale MMR. Verdeling van het eiwitverlies: 83,3% (45/54): verlies van MLH1 en PMS2, 3,7% (2/54): verlies van MSH2 en MSH6, 11,1% (6/54): verlies van alleen MSH6, 1,9% (1/54): verlies van MLH1, PMS2 en MSH6, waarbij MSH2 niet beoordeeld kon worden. Van de 45 tumoren met MLH1/PMS2-verlies hadden 43 normale kiembaanresultaten. Er werden 5 kiembaan PV gevonden: 1 MLH1, 1 MSH2, 3 MSH6. Alle 5 kiembaan PV werden gedetecteerd bij patiënten jonger dan 70 jaar. Deze studie laat dus zien dat MMR-deficiëntie in EC vaak samenhangt met MLH1/PMS2-verlies. De meeste patiënten met MLH1/PMS2-verlies hadden geen erfelijke (kiembaan) PV en alle gedetecteerde kiembaan PV kwamen voor bij patiënten jonger dan 70 jaar, wat suggereert dat zeker op latere leeftijd MLH1-PM een belangrijke rol speelt.

Kaya (2024) beschrijft in een gecombineerde analyse van de PORTEC-1, -2, en -3 trials (n = 1254) dat 84 gevallen van MMRd endometriumkanker (EC) werden geïdentificeerd die niet gerelateerd waren aan MLH1-PM. Van deze gevallen was 37% geassocieerd met Lynch syndroom (MMRd EC), 38% was het gevolg van biallelisch somatische events (DS-MMRd EC), en 25% bleef onverklaard. MMRd EC vertoonde hogere percentages van MSH6-verlies (52% vs. 19%) of PMS2-verlies (29% vs. 3%) dan DS-MMRd EC, en vertoonde uitsluitend MMR-deficiënte klierfoci. DS-MMRd EC had hogere percentages van gecombineerd MSH2/MSH6-verlies (47% vs. 16%), verlies van meer dan 2 MMR-eiwitten (16% vs. 3%), en somatische POLE exonuclease domeinmutatie (25% vs. 3%) dan Lynch syndroom-MMRd.

Post (2021) rapporteert de uitkomsten van moleculair onderzoek in een studiecohort van (PORTEC-1, -2, en -3) 1336 EC's, waarvan 410 (30,7%) MMRd. In totaal waren er 380 (92,7%) volledig getriageerd: 275 (72,4%) waren MLH1-PM MMRd-EC's; 36 (9,5%) Lynch syndroom MMRd-EC's en 69 (18,2%) MMRd-EC's als gevolg van andere oorzaken. In totaal was de Lynch syndroom prevalentie in de onderzoekspopulatie 2,8% en onder MMRd-EC's 9,5%. Op verzoek werden extra gegevens verstrekt over het 70+ cohort. Het betrof in totaal 461 EC-patiënten, van wie er 108 MLH1-PM gerelateerde MMRd, 12 een andere vorm van somatisch MMRd en 6 Lynch-geassocieerde MMRd hadden. Lynch syndroom werd dus aangetoond in 1,3% (6/461) van het totale cohort en 33% (6/18) van de (niet-MLH1 PM) MMRd ECs. Een beperking was het ontbreken van kiembaan Lynch syndroom sequencing bij de hele onderzoekspopulatie, zodat de gevoeligheid van de op IHC gebaseerde triage om Lynch syndroom -patiënten te identificeren, niet kan worden beoordeeld.

In de studie van Hampel (2022) met 341 EC patiënten werd genetische testing uitgevoerd; 27% van de tumoren toonde MMRd, waarbij de meerderheid MLH1-PM vertoonde. Van de 22 (6,5%) gevallen met MMRd, die niet verklaard werden door MLH1-PM, werd bij 10 (2,9% van het totaal) Lynch syndroom vastgesteld (6 MSH6, 3 MSH2, 1 PMS2). Biallelische somatische MMR-events verklaarden de resterende 12 MMRd-gevallen (3,5% van het totaal). Tumoren in oudere leeftijdsgroepen vertoonden vaker MMRd en MLH1-PM, maar geen gevallen van Lynch syndroom. In de leeftijdsgroepen ouder dan 60 jaar werd opvallend geen Lynch syndroom aangetoond, van de tumoren tussen de 60 en 69 jaar (n=124) waren er 37 MMRd (30%), 31 met MLH1-PM. In de leeftijdsgroepen van 70-79 jaar (n=38) en 80-89 jaar (n=8) waren er 15 MMRd (33%), waarvan 14 met MLH1-PM.

Is er voor de detectie van Lynch syndroom reden voor uitbreiding van MMRd-analyse CRC en EC >70 jaar?

MMRd-analyse middels IHC MMR wordt sinds 2016 routinematig in Nederland verricht in CRC en EC gediagnostiseerd <70 jaar. MMRd-analyse wordt echter tegenwoordig bij CRC en EC vaker ook boven de 70 jaar uitgevoerd in het kader van de behandelkeuze. Er is twijfel of het doelmatig is patiënten met een MSI-high tumor in deze groep ook nadere diagnostiek aan te bieden naar Lynch syndroom, of dat het met name somatische afschakeling betreft in het bijzonder door methylatie van de MLH1 promoter (MLH1-PM). De groep met CRC > 70 is bijna net zo groot als het hele cohort onder de 70 (4300 vs. 5086, NKR-cohort 2020). Analyse van deze groep is moeilijk omdat er weinig studies zijn, die zich apart op de 70+ groep richten. Bovendien zijn de data binnen Nederland beperkt, omdat de vorige richtlijn zich tot de groep <70 beperkte. Zoals hierboven al vermeld, heeft Vos (2020) zich daarom gericht op de groep tussen 65 en 70. Van alle CRC-patiënten onder de 70, was 34% tussen de 65 en 70 jaar oud. 12% van deze groep had MLH1-PM in de tumor, 2% had MMRd zonder methylatie. 30% van die laatste groep had Lynch syndroom, maar opgemerkt moet worden dat de totale groep erg klein was (n=10, waarvan 3 met Lynch syndroom). Rond de 0,7% van de groep CRC 65-70 jaar had dus Lynch syndroom.

Eikenboom (2022) voerde een systematische review uit, waarin data werden verzameld van bijna 60.000 patiënten met CRC. 2% van de gehele groep had een kiembaanvariant (PV) in één van de MMR-genen. In de groep <50 jaar lag dit op 7,3%, en <70 op 5,0%. Boven de 70 kon dit niet worden bepaald. De Europese richtlijn van EHTG en ESCP adviseren iedere CRC-tumor te testen op MMRd/MSI (Seppala, 2021). Waarom de groep boven de 70 getest zou moet worden, wordt echter niet onderbouwd. Boven de 65 jaar vertonen veel tumoren met MLH1-afschakeling methylatie van de MLH1-promoter, wat de kosteneffectiviteit verlaagt omdat dit eerst moet worden uitgesloten. Christonson (2023) vergeleek de groep <70 met de groep >80. Het percentage MMRd was in de groep >80 veel hoger dan in de groep <70, maar dit was met name het geval bij vrouwen (50% vs. 10%). BRAF V600E, bij dMMR een marker voor MLH1- PM, was bij oudere vrouwen ook sterker toegenomen dan bij mannen (40% vs. 25%). 67% van alle (bij mannen en vrouwen) dMMR tumoren >80 en 63% van de MMRd tumoren tussen de 60 en 69 had een BRAF V600E mutatie (onder de 50 jaar ligt dat percentage onder de 25%). Daarbij moet worden aangemerkt dat slechts ~70% van alle CRCs met MLH1- PM de BRAF V600E mutatie hebben, terwijl deze praktisch afwezig is bij de niet-MLH1- PM MMRd tumoren (Deng, 2004; Parsons, 2012). Genoemde getallen zijn dus een onderschatting van het percentage MLH1- PM tumoren bij CRC op oudere leeftijd.

Dit wordt ondersteund door de Britse praktijk waar volgens de NICE guidelines alle CRCs getest moeten worden op MSI. Uit een recent overzicht (McRonald, 2024) blijkt dat 67% van de MLH1-deficiënte tumoren MLH1- PM vertoont. De groep 70-plussers maakte de helft van de totale groep uit (8000 van 16000, tabel 2). Het is al met al aannemelijk dat die het grootste deel van de MLH1- PM voor hun rekening nemen, al is dat niet aangegeven in dit artikel.

Om de kleine groep Lynch patiënten (volgens Vos (2020) maximaal 0,7%) uit alle MMRd tumoren te identificeren, zal dus in een significante groep eerst MLH1- PM moeten worden uitgesloten, hetgeen financiële en logistieke consequenties zal hebben. Aangezien dit probleem niet speelt bij MSH2/MSH6 of geïsoleerde PMS2-deficiënte tumoren, zou overwogen kunnen worden deze groep boven de 70 wel te verwijzen voor kiembaandiagnostiek. Echter, ook daar zal een groter deel van de MMRd tumoren verklaard worden door somatische varianten, vergeleken bij jongere patiënten (Elze, 2021).

Er is dus op grond van het vóórkomen van Lynch syndroom in deze groep geen reden routinematig IHC MMR/MSI in te zetten bij de groep CRC 70+. Als dit gedaan wordt ten bate van behandelkeuze, is het risico op Lynch syndroom bij de groep met afwijkende IHC van MLH1 en MSH2 waarschijnlijk klein, tenzij er bij patiënt of in de familie meer aanwijzing is voor Lynch syndroom.

Gezien de hogere gemiddelde leeftijd van CRC bij MSH6 en PMS2 PV dragers (zie submodule Colorectaal kankerrisico en surveillance bij het Lynch syndroom. risico CRC bij Lynch syndroom), kan in die situatie bij afwezige (geïsoleerde) MSH6 of PMS2 kleuring wel overwogen worden verwijzing voor kiembaan diagnostiek te adviseren, hoewel de kanker risico’s bij PMS2 wel veel lager liggen dan bij MSH6, zie ook submodule Colorectaal kankerrisico en surveillance bij het Lynch syndroom. Indien bij afwijkende PMS2 kleuring >70 jaar aanvullende MLH1 kleuring nodig is om te bepalen of sprake is van geïsoleerd PMS2 verlies, kan aanvullende kleuring en verwijzing wat betreft de werkgroep dan ook achterwege gelaten worden.

Wat betreft baarmoederkanker en de kans op Lynch syndroom bij diagnose >70 jaar, is nog minder bekend dan voor CRC. Wel lijkt het aandeel MLH1-PM nog groter dan bij CRC; Meerdere studies (Kahn, 2019; Loong, 2024; Andersson, 2024; Post, 2022) beschreven 25-30% MMRd/MSI in EC, waarbij rond de 3% sprake is van Lynch syndroom. Het overgrote deel van de MMRd/MSI lijkt in EC veroorzaakt te worden door MLH1-promotor methylatie (PM); >80% heeft afwijkende MLH1/PMS2 kleuring, waarvan >80% door MLH1-PM, terwijl deze onderzoeken geen puur 70+ groep beschrijven. Wel beschrijft Post (2022) dat 6 van de totaal 36 Lynch syndroom patiënten (17%) ouder dan 70 jaar waren, vijf hiervan hadden een MSH6 en één een PMS2 PV. Het is niet bekend of deze patiënten eerder al Lynch geassocieerde tumoren hadden (dit was het geval overigens in maar 11% van totaal Lynch syndroom -cohort) of een belast familieverhaal. In tegenstelling tot deze studie laat de studie van Hampel (2021) in de leeftijdsgroep 70-79 jaar (totaal n=38) en 80-89 jaar n= 8) zien dat er van de 15 met MMR-deficiëntie niemand Lynch syndroom had en 14 hadden MLH1-PM.

Van belang verder is nog dat uit kankerrisico-studies (zie ook submodule Colorectaal kankerrisico en surveillance bij het Lynch syndroom) voor met name MSH6 een toename blijkt in risico op EC vanaf 70 jaar (13% CR op 70 jaar naar 23% op 80 jaar, bij de PLSD is er van 70 naar 80 jaar een toename te zien (PLSD 2023, CR 41% op 70 jaar naar 46% op 80 jaar). Het is daarom mogelijk met name MSH6 PV draagsters met EC >70 jaar te missen bij routinematig tumor analyse <70 jaar. Aangezien in ieder geval een deel hiervan, op basis van een positieve voorgeschiedenis of familiegeschiedenis, Lynch syndroom -diagnostiek aangeboden zal krijgen, betreft dit echter waarschijnlijk een kleine groep. Vanuit praktische en doelmatige overwegingen lijkt het de commissie op dit moment verdedigbaar om ook bij EC vast te houden aan routinematige tumoranalyse op aanwijzing voor Lynch syndroom bij diagnose <70 jaar.

Als IHC MMR analyse gedaan wordt ten bate van behandelkeuze >70 jaar, is het risico op Lynch syndroom bij de groep met afwijkende IHC bij MLH1 en MSH2 waarschijnlijk net als bij CRC klein, tenzij er bij patiënt of in de familie meer aanwijzing is voor Lynch syndroom. Gezien de hogere gemiddelde leeftijd van CRC bij MSH6 en PMS2 (zie submodule Colorectaal kankerrisico en surveillance bij het Lynch syndroom) en de eenduidigheid is ook het advies bij bekend geïsoleerd MSH6 en PMS2 verlies te verwijzen voor kiembaan onderzoek. Wel kan, gezien de lagere tumor risico’s bij PMS2, indien MLH1 kleuring (nog) niet gedaan is, ervoor gekozen worden MLH1 kleuring en verwijzing achter wegen te laten.

Concluderend is het advies vooralsnog om routinematig IHC MMR/MSI in te zetten voor het opsporen van Lynch syndroom bij CRC en EC ≤70 jaar. Als >70 jaar analyse gedaan wordt ten bate van behandelkeuze, is het risico op Lynch syndroom bij de groep met afwijkende MLH1 of MSH2 IHC waarschijnlijk klein, tenzij er bij patiënt of in de familie aanwijzing is voor Lynch syndroom. Verdere analyse in de vorm van methylatie onderzoek van de MLH1-promoter en/of kiembaandiagnostiek dienen daarom te worden overwogen indien er bij patiënt of in de familie aanwijzing is voor Lynch syndroom zoals ook aangegeven in de flowchart en in submodule Verwijscriteria voor klinisch genetisch onderzoek bij CRC en genpanelanalyse. Gezien de latere gemiddelde leeftijd van diagnose bij MSH6 en PMS2 zou bij geïsoleerd afwijkende MSH6 of PMS2 IHC >70 jaar wel verwijzing voor kiembaan diagnostiek overwogen kunnen worden. Gezien de lagere tumor risico’s bij PMS2, dient aanvullende diagnostiek in de vorm van IHC MLH1 bij PMS2 beperkt te worden en kan als dit niet bekend is van verwijzing worden afgezien.

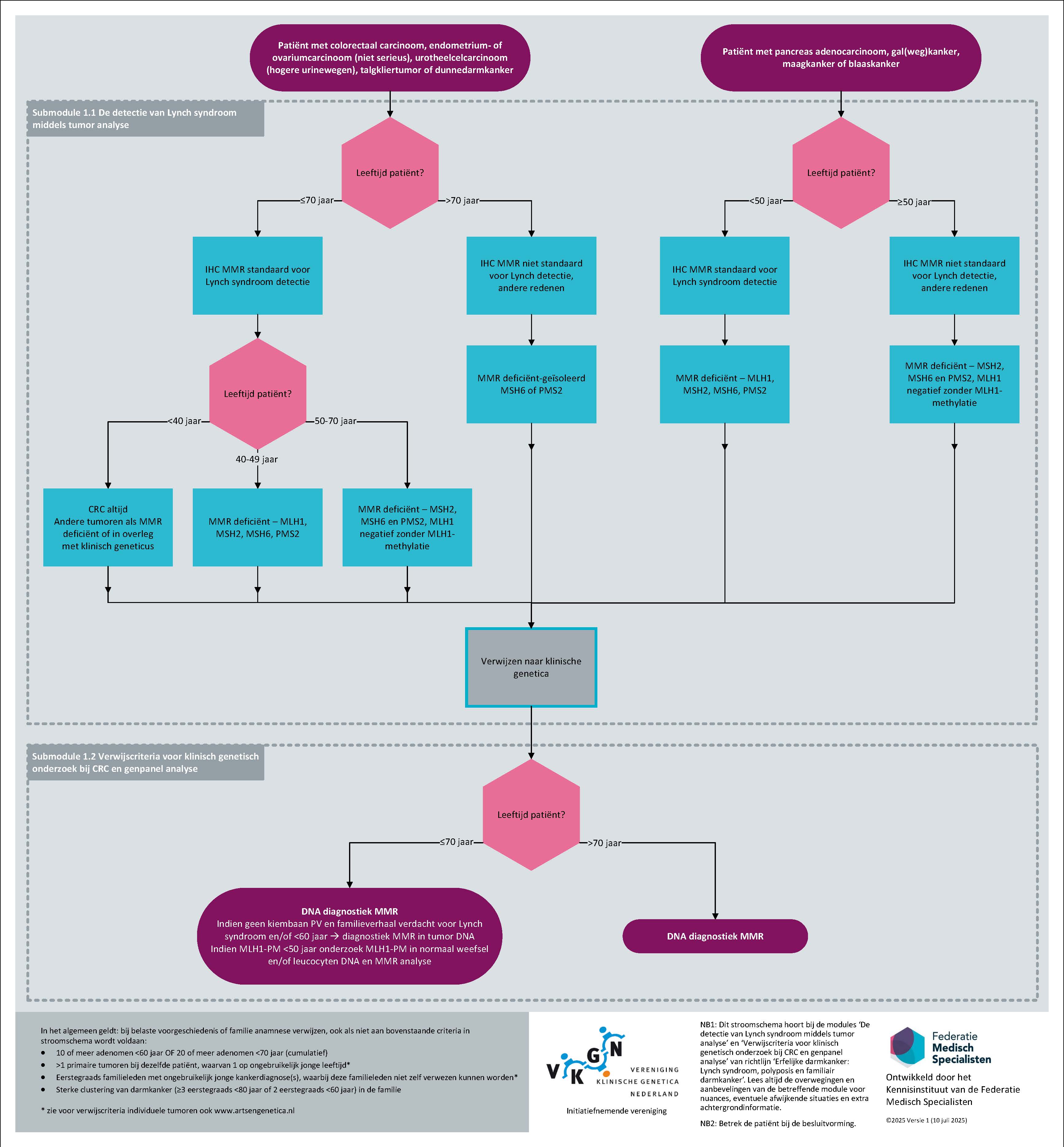

Figuur 1 flowchart (submodule De detectie van Lynch syndroom middels tumor analyse en submodule Verwijscriteria voor klinisch genetisch onderzoek bij CRC en genpanelanalyse); Beleid wanneer IHC MMR en DNA-diagnostiek vanwege verdenking Lynch syndroom

Beleid bij aanwijzing voor Lynch syndroom op basis van tumor analyse

Als er sprake is van een deficiëntie van het MMR-systeem, is er een kans op Lynch syndroom; deze kans verschilt sterk per betrokken gen en per type tumor. Met name afwijkende MLH1-(en PMS2) -kleuring wordt vaak veroorzaakt door methylatie van de MLH1-promoter (MLH1-PM). Belangrijk is ook te realiseren dat MMR-deficiëntie een andere vorm van erfelijke darmkanker niet uitsluit. Daarnaast is het zo dat niet alle tumoren bij een persoon met Lynch syndroom MMR deficiënt zijn en er kan sprake zijn van een sporadische tumor bij iemand met Lynch syndroom in de familie, een fenocopie. Bij blijvende verdenking is het daarom verstandig moleculaire MSI of IHC-analyse van een 2e tumor bij de patiënt of een aangedaan familielid te verrichten.

De betekenis van zowel een positieve als een negatieve test moet in de rapportage van de resultaten duidelijk worden verwoord. Hiervoor zijn ten bate van de patholoog/KMBP’er standaardformuleringen ontwikkeld (zie hiervoor: PALGA moleculaire diagnostiek).

Een flowchart voor verwijzing voor kiembaan diagnostiek naar de Klinische genetica bij MMRd in de tumor is bij aanbevelingen toegevoegd.

Tenslotte dient goede opvolging van patiënten met een MMRd tumor gewaarborgd te zijn en counseling voor kiembaan analyse aangeboden te worden aan alle patiënten en/of hun familieleden voor wie dit relevant kan zijn.

Welke adviezen zijn optimaal bij onverklaard MMRd (UMMRd)?

UMMRd Literatuur

Elze (2021) voerden een studie uit met twee cohorten. Cohort 1 bestond uit patiënten (N = 304) met een MMRd CRC of EC zonder MLH1-promotor methylatie (PM) verwezen naar de Klinische genetica voor verder onderzoek. Hiervan hadden 151 patiënten bewezen Lynch syndroom en 153 patiënten met MMRd CRC (n = 130) of EC (n = 23) geen kiembaan MMR-variant. Het tweede cohort bestond uit patiënten (N = 125) met MMRd CRC (n = 101) of EC (n = 28), waarbij Lynch syndroom en MLH1-PM elders waren uitgesloten. In totaal werd somatische MMRd geïdentificeerd in 88,8% van de geanalyseerde MMRd CRCs (182/205) en 80,9% van de EC's (38/47). Concluderend bleef na somatische analyse slecht een klein deel (2,7%; 32/252 tumoren) onverklaard (UMMRd).

De meta-analyse van Eikenboom (2022) keek naar het aandeel Lynch syndroom, sporadische MMRd en onverklaarde MMRd-gevallen in 58.580 niet-geselecteerde CRCs. In 4.42% van het totale cohort werd geen verklaring voor de MMRd gevonden. Dit percentage bevat waarschijnlijk veel sporadische MMRd CRCs omdat in meeste studies geen somatische test gedaan is. Volledige diagnostiek leidde tot een percentage onverklaarde MMRd van slechts 0,61%. In een literatuur review en analyse van een groot klinisch cohort vonden Eikenboom (2022) respectievelijk 14 en 7 onverklaarde MMRd (UMMRd) cases, waarbij de laatsten suspect bleven voor een gemist somatisch of kiembaan MMR-event. In 2 cases werd met longread sequencing alsnog een complexe MMR PV aangetoond.

Nugroho (2023) verrichtten een systematische review van studies, die kankerrisico's bij Lynch-like syndroom (LLS) onderzochten, waarin zes studies geïncludeerd zijn. De resultaten lieten zien dat de incidentie van CRC bij LLS-patiënten vergelijkbaar was met die van de algemene bevolking, maar lager dan bij Lynch syndroom-patiënten. De incidentie van CRC was hoger bij eerstegraadsverwanten van LLS-patiënten dan bij de algemene bevolking, maar lager dan bij Lynch syndroom-eerstegraadsverwanten. Ook EC kwam vaker voor bij LLS-patiënten dan bij de algemene bevolking, maar minder vaak dan bij Lynch syndroom -patiënten.

In een studie die gegevens van het Duitse Consortium voor Familiair Intestinaal Kanker analyseerde, werden 1448 patiënten prospectief gevolgd in een intensief coloscopisch screeningsprogramma (Bucksch 2022). De cumulatieve risico's voor adenomen en CRC werden vergeleken tussen drie risicogroepen: Lynch syndroom, Lynch-like syndroom (LLS) en familiaire colorectale kanker zonder de typische genetische kenmerken (FCCX). Het risico op CRC was het hoogst bij Lynch syndroom gevolgd door LLS, en het laagst bij FCCX. Er werd ook een verschil gevonden in de risico's voor eerste en tweede primaire CRC tussen de drie groepen, hoewel de risico's voor adenomen vergelijkbaar waren.

In hoeverre moet somatische MMR-gen analyse verricht worden indien geen MLH1-PM of Lynch syndroom aangetoond wordt bij MMRd een tumor?

Patiënten worden aangeduid als patiënten met onverklaard MMRd (UMMRd) of met het Lynch-like syndroom (LLS). Beter is, zoals Katz eerder hebben opgemerkt, dat het gebruik van de term LLS wordt vermeden aangezien dit onterecht toch suggereert dat Lynch syndroom waarschijnlijk is, en dat UMMRd voortaan als volgt wordt gedefinieerd: tumoren die, bij MMR-deficiënte eiwitkleuring voor ten minste 1 MMR-eiwit, niet (genoeg) verklaard zijn door pathogene MMR, somatische dan wel kiembaan, events. Zie ook begrippenlijst met de definitie UMMRd.

Op dit moment zijn alleen voor CRC en EC-data beschikbaar ten aanzien van onverklaarde (UMMRd).

De meta-analyse van Eikenboom (2022) laat zien dat het percentage gevallen van UMMRd voor CRC sterk afhankelijk is van de volledigheid en het type diagnostiek dat wordt gebruikt. In studies die alle diagnostische stadia voltooiden, werden kiembaanvarianten gevonden in ongeveer 3% van de CRCs. Bovendien leidde volledige diagnostiek tot een percentage UMMRd van slechts 0,61%. Dit lage percentage UMMRd in CRC bij volledige diagnostiek wordt bevestigd in de literatuur review en retrospectieve studie van een klinisch cohort van dezelfde onderzoeksgroep, waarbij in een groot klinisch cohort slechts 7 patiënten met een UMMRd over blijven, waarvan bij 2 alsnog een complexe kiembaan variant wordt aangetoond met longread sequencing. Deze worden nader beschreven in de studie van te Paske (2022), waarin bij 8/32 (18,8%) patiënten met UMMRd een kiembaan PV in een niet-coderende sequentie van een MMR-gen wordt aangetoond.

Onder andere Elze (2021) en de Vos (2020) tonen aan dat het percentage somatisch verklaarde MMRd, zowel door MLH1-PM als biallelische MMR-gen events in de tumor, met de leeftijd toe neemt voor alle MMR-genen. De kans dat na uitsluiting van MLH1-PM in de tumor (indien relevant) en negatieve kiembaan diagnostiek toch sprake is van Lynch syndroom is dus afhankelijk van leeftijd van diagnose en uiteraard ook familiegeschiedenis (indien informatief) en neemt sterk af >65 jaar (Hitchins 2023). Het lijkt op dit moment het meest doelmatig om bij een MMRd tumor en negatieve kiembaan diagnostiek alleen bij blijvende verdenking op Lynch syndroom verdere diagnostiek naar (gemiste) somatische en kiembaan afwijkingen te verrichten. Deze grens kan arbitrair gelegd worden bij diagnose <60 jaar, tenzij de voor- of familiegeschiedenis verdacht is voor Lynch syndroom, waarbij ook eventueel onderzoek bij andere familieleden uitsluitsel kan geven of een gemiste MMR-gen kiembaan aanleg waarschijnlijk is of niet.

Wat is het klinisch beleid indien de MMRd onverklaard (UMMRd) blijft?

Enkele studies hebben naar het darmkanker risico in (eerstegraads familieleden (FDR) van) mensen met onverklaarde mismatch repair deficiënte (UMMRd) tumoren gekeken, in de meeste gevallen is overigens geen somatische tumor analyse gedaan. Nugroho (2023) beschrijft zes studies, waarbij het merendeel een hoger CRC-incidentie in “Lynch-like-syndroom” (LLS) FDRs vonden dan in de algemene bevolking maar lager dan bij Lynch syndroom FDRs. Ook was het risico op EC hoger in LLS-patiënten dan in de algemene bevolking, maar lager dan in Lynch syndroom patiënten. Ook de studie van Bucksch (2022) beschrijft het hoogste CRC-risico in Lynch syndroom, gevolgd door LLS het laagst in FCC.

Bij benadering zou er sprake zijn van een gemiddeld twee keer verhoogd risico op CRC en lijkt er geen onderbouwing voor een Lynch controle advies in de meerderheid van deze families. Afhankelijk van leeftijd en familieanamnese kan een advies gebaseerd op de familiair CRC (FCC)-criteria worden gegeven, als aan FCC-criteria wordt voldaan, zie submodule Incidentie, risico’s en surveillance bij familiair colorectaal carcinoom .

Bij een sterk belaste voor- of familiegeschiedenis of MMRd tumor bij een tweede familielid en geen kiembaan MMR-gen PV of somatische verklaring, kan intensievere darm- en eventueel baarmoeder surveillance (volgens Lynch syndroom protocol) worden overwogen.

Kwaliteit van bewijs

Niet van toepassing, want de gebruikte studies zijn niet met GRADE beoordeeld.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun naasten/verzorgers)

Vanuit de patiënten wordt aangegeven dat zij het van groot belang achten dat iedere Lynch patiënt gediagnostiseerd wordt, niet alleen voor optimaal beleid voor de patiënt maar ook zodat familieleden van preventieve opties gebruik kunnen maken. Routinematig IHC-MMR/IHC analyse, ook bij andere Lynch syndroom geassocieerde tumoren, draagt hier in grote mate aan bij, hoewel goede opvolging bij een afwijkende tumor analyse nog wel een punt van zorg is. Ook dient een afweging gemaakt te worden wat betreft doelmatigheid, zodat moleculaire analyses en klinische genetische zorg beschikbaar blijven voor degenen met het hoogste risico.

Kostenaspecten

Verschillende studies, waaronder Nederlandse, hebben de kosteneffectiviteit van routinematige tumor analyse voor de detectie van Lynch syndroom in CRC en EC <70 jaar aangetoond. Gezien de opbrengst van tumor analyse en identificatie van Lynch syndroom in andere Lynch syndroom geassocieerde tumoren, is naar alle waarschijnlijkheid uitbreiding van indicatie van routinematige tumor analyse op MMd/ IHC bij diagnose <70 of <50 jaar bij andere Lynch syndroom geassocieerde tumoren ook kosteneffectief (Snowsill, 2020; Stinton, 2021; Leenen, 2016; Goverde, 2016).

Gelijkheid ((health) equity/equitable)

Aangezien de aanbevelingen het routinematig testen van tumoren op aanwijzing voor Lynch syndroom betreffen, leidt dit naar verwachting tot meer gelijkheid van zorg ten opzichte van de huidige praktijk, waarbij bij veel Lynch syndroom geassocieerde tumoren nog afgegaan wordt op familieanamnese, welke minder betrouwbaar kan zijn bij verminderde gezondheidsvaardigheden van patiënten en onvoldoende systematisch uitvragen van de familiegeschiedenis door de zorgverleners.

Aanvaardbaarheid:

Sinds de richtlijn van 2015 wordt routinematige tumor analyse op aanwijzing voor Lynch syndroom al landelijk toegepast voor alle CRC en EC-patiënten gediagnostiseerd <70 jaar. Bij afwijkende tumor analyse kunnen patiënten kiezen voor verdere kiembaan analyse naar Lynch syndroom of niet. De huidige adviezen wijken hier niet van af, alleen is de indicatie voor tumor-analyse verbreed.

Het opsporen van dragers van een aanleg voor Lynch syndroom en aanbieden van surveillance, leidt tot een afname van morbiditeit en mortaliteit in deze groep. Het voorkomt kanker diagnoses en behandeling, met name ook bij jonge mensen, die nog een belangrijke maatschappelijke rol hebben. De adviezen in deze richtlijn, worden daarom door de werkgroep als aanvaardbaar beoordeeld.

Haalbaarheid

In de aanbevelingen is nadrukkelijk rekening gehouden met de haalbaarheid van uitbreiding van analyse door bij frequente tumoren, waarbij opbrengst laag lijkt af te zien van routinematig IHC-MMR/MSI-testen of een leeftijdsgrens aan te houden, welke doelmatig lijkt.

Op basis van de ervaring met routinematige tumor analyse op Lynch syndroom bij alle CRC en EC <70 jaar, welke sinds 2015 in Nederland verricht wordt, worden de voorgestelde aanbevelingen haalbaar geacht.

Rationale van aanbeveling-1: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

Op basis van de prevalentie van Lynch syndroom bij andere Lynch syndroom geassocieerde tumoren dan CRC en EC, is het zinvol routinematig IHC-MMR/MSI analyse uit te breiden naar een groot deel van deze tumoren. Hierbij is per tumor op grond van de huidige gegevens afgewogen voor welke leeftijdscategorie deze analyse het meest doelmatig is.

Eindoordeel:

Sterke aanbeveling voor (Doen)

Rationale van aanbeveling-2: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Ondanks de beperkingen blijven IHC-MMR en de traditionele moleculaire MSI-testen relatief gevoelige, snelle en kosteneffectieve methoden voor het detecteren van MMRd met als doel het opsporen van Lynch syndroom. Omdat bij een MLH1- en MSH2-aanleg ook afwijkende kleuring van respectievelijk PMS2 en MSH6 verwacht wordt, kan ervoor gekozen worden in eerste instantie MSH6 en PMS2 kleuring te verrichten en indien afwijkend ook kleuring van de andere 2 MMR eiwitten te verrichten, mede om te bepalen of verder onderzoek naar MLH1-promoter methylatie (PM) nodig is. MLH1-PM is vaak sporadisch, maar indien de diagnose <50 jaar is of er een belaste familieanamnese is, dan is er een reële kans dat er alsnog een kiembaan MLH1 pathogene variant, dus Lynch syndroom, aanwezig is.

Eindoordeel: Sterke aanbeveling voor (Doen)

Rationale van aanbeveling-3: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Indien in geval van een MMRd tumor zonder MLH1-promoter methylatie (PM) geen kiembaan aanleg wordt aangetoond, hangt de kans dat alsnog sprake is van Lynch syndroom samen met de eigen voorgeschiedenis en familieanamnese van de patiënt. Hoe ouder de patiënt bij diagnose en hoe minder suspect de familie (indien informatief), des te kleiner de kans dat sprake is van Lynch syndroom. Dit dient meegenomen te worden in de afweging of verdere (dure) somatische analyse zinvol is en of familieleden blootgesteld moeten worden aan intensieve controles.

Bij benadering zou er sprake zijn van een gemiddeld twee keer verhoogd risico op CRC en lijkt er geen onderbouwing voor een Lynch controle advies in de meerderheid van deze families. Afhankelijk van leeftijd en familieanamnese kan een advies gebaseerd op de familiair CRC (FCC)-criteria worden gegeven, als aan FCC-criteria wordt voldaan, zie submodule Incidentie, risico’s en surveillance bij familiair colorectaal carcinoom. Bij een sterk belaste voor- of familiegeschiedenis of MMRd tumor bij een tweede familielid en geen kiembaan MMR-gen PV of somatische verklaring, kan intensievere darm- en eventueel baarmoeder surveillance (volgens Lynch syndroom protocol, submodule Colorectaal kankerrisico en surveillance bij het Lynch syndroom en submodule Extracolonische kankerrisico en surveillance bij het Lynch syndroom worden overwogen.

Eindoordeel:

Sterke aanbeveling voor (Doen)

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Lynch Syndrome is the most common hereditary colorectal (CRC) and endometrial cancer (EC) syndrome, with an estimated prevalence of 2-3% of patients with CRC and EC. It is caused by pathogenic germline variants in one of the mismatch repair (MMR) genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 or a deletion of the 3’ end of the EPCAM gene. Tumors with defective MMR display a microsatellite instability (MSI) phenotype. Since 2015, it has been standard policy in the Netherlands to perform immunohistochemical staining (IHC) for mismatch repair deficiency (MMRd) for every patient <70 years old with CRC or EC, to diagnose Lynch Syndrome. The question has risen whether this policy should be extended to CRC and EC patients> 70 years of age and to other Lynch-associated malignancies (ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, biliary tract and gall bladder cancer, urothelial cancer, small bowel cancer, stomach cancer, brain tumors, sebaceous gland tumors) and prostate cancer. Extension of the policy to other Lynch-associated malignancies will lead to better detection of Lynch syndrome and to reduced incidence and mortality from especially CRC through colonoscopy surveillance programs. However, this must be weighed against additional costs for IHC staining and possible unnecessary somatic and germline testing. In case no germline PV in one of the MMR genes is found in a patient with an MMRd tumor, somatic tumor analysis may exclude the diagnosis Lynch syndrome by finding biallelic somatic MMR gene events in the tumor. However, it should be weighted to what extent somatic analysis should be performed and what advice should be given in case the MMRd remains unexplained (UMMRd). These questions will be addressed in this chapter of the revised guideline.

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

A total of 35 studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in Table 2. A description of each study categorized per cancer type, is provided below. The risk of bias of included studies was not assessed. Therefore, the risk of bias table was not included.

Epithelial ovarian cancer

Mitric (2023) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis in which the aim was to assess the prevalence of MMR deficiency (MMRd), microsatellite instability (MSI)-high, and Lynch syndrome, in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) of any histologic subtype. The search date was February 2nd, 2022. Related to the intervention and outcome, studies were included that met the following criteria: 1) IHC MMR testing, if tested for at least three MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6), 2) MSI testing using the national cancer institute NCI five markers and 3) germline sequencing if tested for at least three MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6). Included study designs were cohort, cross-sectional, and case-series. The outcomes relevant for this literature analysis included prevalence of MMRd, MSI-H, and Lynch syndrome.

Pancreatic cancer, biliary tract cancer and gallbladder cancer

Agaram (2010) performed a retrospective cohort study of 54 cases with ampullary carcinoma, to investigate the prevalence of MMRd by IHC. The tumor samples were resected at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, and were selected from the pathology database. IHC was assessed with antibodies against MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2. Lack of nuclear staining in the invasive carcinoma cells was defined as abnormal. The outcomes relevant for this literature analysis were the prevalence of MMRd and prevalence of MMRd patients with lost MLH1/PMS2 expression.

Hu (2018) performed a retrospective cohort study in which the aim was to investigate the prevalence of MMRd in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Between January 2006 and July 2017, the MSKCC institutional tumor registry was searched for PDAC tumor samples. Finally, 833 patients were included. MMRd was tested using IHC, germline testing, or tumor and germline DNA sequencing using MSK-IMPACT. IHC was assessed with antibodies against MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2. MSI analysis was performed using the five microsatellite loci by PCR or MSI sensor analysis. MSI-H was defined as microsatellite instability at ³2 loci or as >10% of the microsatellite loci showing microsatellite instability. NGS was conducted using the MSK-IMPACT assay. Outcomes relevant for this literature analysis included the proportion of patients with overall MMRd, with lost MLH1 and/or PMS2 expression, and with Lynch syndrome.

Christakis (2019) performed a study in which the aim was to determine the prevalence of microsatellite instability in upper gastrointestinal tract cancers and to screen for patients with Lynch syndrome. In total, 645 patients with upper gastrointestinal tract cancers were prospectively enrolled in an institutional cohort study at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and were sequenced using NGS. From these upper gastrointestinal tract cancers, pancreatic carcinoma (n=199), gastric carcinomas (n=97), bile duct carcinomas (n=60), small bowel carcinomas (n=29), and gallbladder carcinomas (n=19) were relevant for this literature analysis. Then, microsatellite instability was defined as >3 microsatellite indel events per megabase pair in the targeted genome. All samples with microsatellite instability detected by NGS, and with available pathology material, were assessed for MMRd by IHC for MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, and MSH6 expression using a case-control study design. Each case (microsatellite instable) was matched with ³2 controls (microsatellite stable). Depending on tissue availability, IHC was also performed on all samples greater than 2 but fewer than 3 microsatellite indel events per megabase pair. Tumor samples were additionally assessed for MLH1 promoter methylation status. Outcomes relevant for this literature analysis included the proportion of patients with overall MMRd, with lost MLH1 and/or PMS2 expression, with MLH1 promoter hypermethylation, with Lynch syndrome, and with somatic mutations.

Abrha (2020) performed a retrospective review of all patients with extracolonic gastrointestinal (GI) malignancies at Stanford Comprehensive Cancer Institute screened for MMRd via IHC between January 2016 and December 2017. A total of 1425 gastrointestinal malignancies of non-squamous etiology were screened. After exclusion of cases with insufficient medical information or unknown primary location, 1374 gastrointestinal cancer patients were left for analyses. Among those gastrointestinal malignancies, pancreatic carcinoma (n=244), gastric carcinoma (n=150), gallbladder carcinoma (n=41), and small bowel cancer (n=20) were relevant for this literature analysis. IHC was performed for the 4 MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2). Germline testing for Lynch syndrome was performed in tumor material deficient for MSH2/MSH6, MSH6 alone or PMS2 alone or if the following criteria were met: MLH1/PMS2 deficient, BRAF mutation negative, and/or MLH1 promoter methylation negative. In case of negative Lynch syndrome testing, specimens were sent for somatic tumor sequencing. Outcomes relevant for this literature analysis included the prevalence of overall MMRd, MLH1 promoter methylation, biallelic somatic pathogenic events, and Lynch syndrome.

Mettman (2020) performed a retrospective cohort study in which the aim was to determine the prevalence of MMRd in pancreatic adenocarcinoma in fine-needle aspiration (FNA) specimens. The medical record system of the University of Kansas Medical Center was reviewed to identify all FNA specimens with a diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. IHC staining was conducted for the 4 MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2) to cases with sufficient tumor material only. In total, 184 pancreatic FNA specimens were identified, of which 65 contained sufficient material to perform IHC staining. Outcomes relevant for this literature analysis included the prevalence of overall MMRd.

Grant (2021) performed a retrospective cohort study in which the aim was to better understand MMRd pancreatic cancer. The Ontario Pancreas Cancer Study was used for this purpose, and this study prospectively collected epidemiological data and biospecimens from patients with pancreatic cancer in Ontario, Canada. IHC for MMR testing was conducted for the 4 MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2) as well as whole-genome and transcriptome sequencing. MMRd was defined as one of the following: somatic loss of a pair of MMR proteins by IHC or biallelic pathogenic events from whole-genome sequencing. MSI was detected using MSIsensor2. Outcomes relevant for this literature analysis included the prevalence of overall MMRd, lost MLH1/PMS2 expression, with a germline pathogenic variant, and of somatic mutations.

Kryklyva (2022) conducted a retrospective cohort study aiming to explore the prevalence of MMRd in early-onset carcinomas of duodenal (DC), ampullary (AC, and pancreatic (PC) origin. A nationwide retrospective search in the Nationwide Network and Registry of Histopathology and Cytopathology (PALGA) was performed to identify all patients with DC, AC and PC under the age of 50 in the Netherlands between January 2002 and December 2012. IHC MMR was performed using standard procedures. MSI status was assessed using five mononucleotide markers. Cases with more than one unstable marker were classified as having a high degree of MSI (MSI-H). MLH1 promoter methylation was detected using MS-MLPA on tumor DNA from MLH1- and PMS2-deficient cases. The outcomes relevant for this literature analysis were the proportion of patients with MMRd, MLH1 promoter methylation, and Lynch.

Kubo (2022) performed a retrospective cohort study in which the aim was to determine the prevalence of MSI-H status in hepato-biliary-pancreatic malignancies. In total, 283 patients from 7 hospitals in the Kansai Hepato-Biliary Oncology Group (KHBO) were included. Patients with MSI status detected by NGS were excluded from the study. Relevant malignancies for this literature analysis were intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (n=88), gallbladder carcinoma (n=18), and pancreatic carcinoma (n=144). MSI status was assessed by PCR fragment analysis, with MSI-H defined as ³2 unstable markers. The outcomes relevant for this literature analysis were the proportion of patients with overall MMRd, MLH1 promoter methylation, and Lynch syndrome.

Moy (2015) performed a retrospective cohort study in which the aim was to determine the prevalence of MMRd in patients with gallbladder carcinoma. The surgical pathology files of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston were searched and cases from 1988 to 2012 were selected. Protein expression of 4 MMR proteins were evaluation by IHC staining. MSI was defined as complete loss of nuclear staining for ³1 of the 4 MMR proteins. Lynch syndrome was assessed in the group with MSI. Hot spot mutations were detected using SNaPshot, which is a mutation assay. The outcomes relevant for this literature analysis were the prevalence of overall MMRd, loss of expression of MLH1 and/or PMS2, and Lynch syndrome.

Goeppert (2019) performed a retrospective cohort study in which the aim was to determine the prevalence of MSI among gallbladder carcinomas. The cohort included tumor material from 69 patients who underwent hepatobiliary surgery at the University Hospital Heidelberg between 1995 and 2010. None of the patients received radio- and/or chemotherapy prior to surgery. All tumors classified as MSI were analyzed by IHC staining to determine the prevalence of MMRd proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2). MMR-induced MSI status was assessed using the MSI marker panel. One outcome relevant for this literature analysis included the prevalence of overall MMRd.

Ju (2020) performed a retrospective cohort study in which the aim was to determine the prevalence of MMRd/MSI in patients with cholangiocarcinomas. In total, 96 cases diagnosed between 1993 and 2014 were identified after a search in the Citrix Copath and EPIC Hyperspace database. MMRd was assessed by IHC staining on 4 MMR genes. All cases with any MMR loss on IHC were tested for MSI status. MSI status was evaluated using the MSI Analysis System, analyzing 5 mononucleotide regions. MSI-H was defined as having novel allele peaks in the tumor sample with absence in the corresponding normal sample at 2 or more of the 5 mononucleotide repeat markers tested. MSI-L was defined as any cases with peak shifts in only 1 of the 5 regions tested. Cases were considered MMRd if the tumor sample had loss of expression of ³1 MMR proteins on IHC and MSI-L or -H status. Cases with lost MLH1/PMS2 expression were additionally tested for MLH1 promoter methylation. The outcomes relevant for this literature analysis included the prevalence of overall MMRd, loss of expression of MLH1 and/or PMS2 with MLH1 promoter methylation, and Lynch syndrome.

Ando (2022) performed a retrospective cohort study in which the aim was to determine the prevalence of MMRd/MSI-H among biliary tract carcinomas. In total, 116 patients diagnosed with biliary tract carcinoma and undergoing surgery between January 2008 and December 2017 at Kagawa University Hospital in Japan, were enrolled in the study. IHC staining of 4 MMR proteins was performed. Abnormal staining was defined as the absence of nuclear staining in the tumor cells while there is presence of nuclear staining of non-neoplastic cells. MSI status was performed in patients with MMRd and in patients with a family history of Lynch syndrome -associated cancers, using the MSI analysis system. MSI-H was defined as ³2 markers demonstrating altered numbers of repeats. The outcomes relevant for this literature analysis included the prevalence of overall MMRd and loss of expression of MLH1 and/or PMS2.

Upper tract urothelial cancer (UTUC) and bladder cancer