Beoordeling valrisicoverhogende medicatie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van het gebruik van instrumenten om valrisicoverhogende medicatie te identificeren en/of af te bouwen bij ouderen?

De uitgangsvraag omvat de volgende deelvraag:

- Welke instrumenten kun je gebruiken om valrisicoverhogende medicatie te identificeren en/of af te bouwen bij ouderen?

Aanbeveling

1. Voer altijd een gestructureerd medicatiereview met passende medicatieafbouw uit als onderdeel van een multifactoriële valrisico beoordeling.

2. Gebruik een gestructureerd medicatiereview instrument, bij voorkeur de STOPPFall, ter ondersteuning van het in kaart brengen van valrisicoverhogende en de gepersonaliseerde stappen van passende medicatieafbouw te ondersteunen, zowel bij routine medicatiereviews als bij medicatiereviews gericht op valpreventie bij ouderen.

Zie bijlage STOPPFall medicatielijst en adviezen voor medicatie afbouw)+ bijlage Overzicht van risicoverschillen voor STOPPFall medicatielijst & het interactieve STOPPFall instrument

3. Neem het valrisico mee in de overweging om valrisicoverhogende medicatie bij ouderen wel of niet voor te schrijven. Vraag hiertoe voorafgaand aan het voorschrijven of iemand in het afgelopen jaar gevallen is, moeite heeft met bewegen, lopen of balans houden en/of bezorgd is om te vallen.

Overwegingen

Associatie tussen medicatie en valrisico

Medicijnen kunnen via verschillende mechanismen een val veroorzaken, ofwel als gevolg van een bijwerking, of als gevolg van (relatieve) overdosering. Gezien de aanzienlijke stijging van medicatiegebruik en polyfarmacie bij ouderen sinds de jaren ’80, is de impact van medicatiebijwerkingen zoals vallen op deze groep zeer groot (Craftman, 2016). Juist bij ouderen spelen medicatiebijwerkingen een belangrijke rol bij het ontstaan van vallen, onder andere door het veelvuldige gebruik van medicatie, polyfarmacie, waardoor een hoger risico op interacties ontstaat (zie ook de multidisciplinaire richtlijn Polyfarmacie bij Ouderen). Daarnaast speelt bij ouderen toegenomen gevoeligheid voor bijwerkingen een rol, door onder andere veranderde lichaamssamenstelling, veranderde receptorgevoeligheid en verminderde reservecapaciteit van organen. Voorbeelden van medicatie die ten grondslag kan liggen aan een val zijn: cardiovasculaire medicatie, middelen met een sederende werking (bv psychofarmaca) en middelen met een hypoglycemische werking. Om medicatie die deze interacties en bijwerkingen veroorzaken te identificeren en eventueel af te bouwen, wordt in de richtlijn Polyfarmacie bij ouderen sterk aanbevolen een systematische werkwijze te hanteren.

Effectiviteit van medicatiereview met passende afbouw

Gezien de associatie tussen medicatie en valrisico, is het identificeren van valrisicoverhogende medicatie en het eventuele afbouwen hiervan een belangrijke factor voor de verlaging van het valrisico (Montero-Odasso, 2022). Gepubliceerde literatuur, waaronder een recente systematische review met netwerkanalyse bevestigt dat er sterk bewijs is dat een beoordeling en aanpassing van valrisicoverhogende medicatie één van de effectieve onderdelen van de multifactoriële valrisicobeoordeling is (Dautzenberg, 2021; Hopewell 2018, Montero-Odasso, 2022; Montero-Odasso, 2021). In de recent (gepubliceerde wereldrichtlijn Valpreventie (Montero-Odasso, 2022) staat op basis van GRADE beoordeling van deze literatuur de sterke aanbeveling om om een gestructureerde medicatiereview met passende medicatieafbouw standaard uit te voeren als onderdeel van de multifactoriële valrisicobeoordeling. Daarnaast is door de werkgroep van de wereldrichtlijn onderzocht in een systematisch review of een (algemeen) medicatiereview als enkelvoudige interventie ook effectief is (Seppala, 2022a). Dit bleek niet het geval. Dit benadrukt de noodzaak om het medicatiereview gericht op passende afbouw van valrisicoverhogende medicatie uit te voeren in de context van een multifactoriële valrisicobeoordeling, idealiter in de vorm van een comprehensive geriatric assessment (Montero-Odasso, 2022; Seppala, 2022b; van der Velde, 2022). Mogelijkerwijs is in de verpleeghuissetting een medicatiereview als enkelvoudige interventie wel al effectief (Seppala, 2022a). Gezien de multifactoriële aard van vallen heeft het desalniettemin toch de sterke voorkeur om altijd een multifactoriële valrisicobeoordeling uit te voeren in deze kwetsbare, hoog-risico populatie, uiteraard met een medicatiereview als vast onderdeel (Seppala, 2022; Montero-Odasso, 2022).

Om onnodig valrisico te voorkomen, heeft het daarnaast conform de wereldrichtlijn de sterke voorkeur om in algemene zin bij ouderen al voorafgaand aan het voorschrijven van valrisicoverhogende medicatie het valrisico (inclusief valhistorie) in kaart te brengen en dit mee te nemen in de besluitvorming om wel of niet valrisicoverhogende medicatie voor te schrijven (Montero-Odasso, 2022).

Medicatiereviewinstrumenten voor valrisicoverhogende medicatie

Ten aanzien van de optimale aanpak van een medicatiereview zijn de wereldrichtlijn valpreventie (Montero-Odasso, 2022) en de multidisciplinaire richtlijn Polyfarmacie bij Ouderen eenduidig. In beide richtlijnen staat de sterke aanbeveling om een medicatiereview gepersonaliseerd en gestructureerd uit te voeren met behulp van een instrument (Montero-Odasso 2022).

Algemene medicatiereview instrumenten bevatten veelal een categorie ‘valrisicoverhogende medicatie’ (STOPP/START, BEERS, etc). Deze beperken zich meestal tot de meest gebruikte, hoog-risico medicatie. De werkgroep is van mening dat het de voorkeur heeft om een instrument te gebruiken dat specifiek ontwikkeld is om valrisicoverhogende medicatie in kaart te brengen, en zowel veel gebruikte als minder frequent voorgeschreven middelen bevat. Daarnaast is de werkgroep van mening dat een instrument idealiter informatie verschaft over (1) de symptomen/bijwerkingen waarop gelet dient te worden (bv. Duizeligheid) evenals (2) welke symptomen en klachten na afbouw vervolgd dienen te worden (bv. stemmingsklachten). Dit om zowel de positieve als mogelijke negatieve effecten van de medicatieafbouw te kunnen vervolgen. Advies ten aanzien van de frequentie van follow-up is hierbij ook van belang (Seppala, 2020; van der Velde, 2023) . Een voorbeeld van een Delphi consensus instrument, waarin rekening is gehouden met bovenstaande punten is de STOPPFall (Seppala, 2021), ontwikkeld door Europese experts. In bijlage STOPPFall medicatielijst en adviezen voor medicatie afbouw) vindt u het overzicht van de consensuslijst van valrisicoverhogende medicatie conform STOPPFall. In bijlage Overzicht van risicoverschillen vindt u een overzicht van risicoverschillen tussen subklassen van valrisicoverhogende medicatie, gebaseerd op appendix III van de Delphi studie over de ontwikkeling van de STOPFall (Seppala, 2021). Voor meer gedetailleerde informatie ten aanzien van verschillende bijwerkingenprofielen van subklassen van valrisicoverhogende medicatie en individuele middelen wordt verwezen naar een serie van clinical reviews over dit onderwerp (van Poelgeest, 2023; Korkatti-Puoskari, 2023; Capiau, 2022; Ilhan, 2023; Portlock, 2023; Welsh, 2023; Virnes; 2022; van Poelgeest, 2021).

Om een weloverwogen gezamenlijke keuze te kunnen maken zijn onderstaande punten belangrijk om mee te nemen (Seppala, 2021):

- Of de patiënt(e) en behandelaar goed op de hoogte zijn van de indicatie waarvoor het medicijn gegeven wordt en of de indicatie nog wel bestaat;

- Indien er een behandelindicatie is, besproken wordt of de dosering verlaagd moet worden of het doseerinterval of -tijdstip aangepast moet worden, en of er mogelijk veiliger (niet-) medicamenteuze alternatieven er beschikbaar zijn;

- Indien geen aanpassingen in dosering en geen veiliger alternatieven mogelijk zijn: in samenspraak met de patiënt en andere behandelaars de behandeldoelen prioriteren met specifieke aandacht voor bijwerkingen die kunnen leiden tot vallen.

- Welke symptomen zouden kunnen terugkeren na afbouwen van het betreffende medicijn, en of er onttrekkingsverschijnselen zouden kunnen optreden.

Bij deze stappen is in de STOPPFall de relevante informatie beschikbaar in de beslisbomen. Een interactieve versie van het STOPPFall instrument is vrij beschikbaar. Ter ondersteuning van deze besluitvorming is daarnaast recent een serie reviewartikelen verschenen van de Europese werkgroep naar valrisicoverhogende medicatie, waarin nog diepgaander voor de meest voorgeschreven groepen van valrisicoverhogende medicatie per medicatiesubgroep de indicaties, veiligere alternatieven, en de mogelijke symptomen die kunnen leiden tot vallen als benodigde follow-up worden beschreven. Onder andere bevatten deze klinische reviews een tabel waarin per medicijn en per bijwerking semi-kwantitatief de prevalentie wordt weergegeven, zodat makkelijker een veiliger alternatief gevonden kan worden (Capiau, 2022; van Poelgeest, 2021; van Poelgeest, 2023; Virnes, 2022; Korkatti-Puoskari, 2023; Ilhan, 2023; Portlock, 2023; Welsh, 2023). Daarnaast kunnen ook geneesmiddelteksten van EPHOR app (Expertisecentrum pharmacotherapie bij ouderen) ter ondersteuning van de besluitvorming worden gebruikt, aangezien daarin standaard de voor vallen relevante bijwerkingen worden gerapporteerd (o.a. duizeligheid, valneiging, orthostatische hypotensie).

De werkgroep wil benadrukken dat de STOPPFall consensus lijst van valrisicoverhogende medicatie de meest belangrijke valrisicoverhogende medicamenten bevat, maar dat deze niet uitputtend is. De lijst van medicijnen die bijwerkingen kunnen hebben die tot valincidenten kunnen leiden is vele malen langer. Bij een medicatiebeoordeling is het zodoende van belang om niet strikt aan een instrument vast te houden, maar deze als leidraad te gebruiken en specifieke aandacht te hebben voor de mogelijke relevante bijwerkingen voor de individuele patiënt(e). In de genoemde EPHOR app worden mogelijke relevante bijwerkingen in het kader van valrisico per geneesmiddel beschreven.

Voor- en nadelen van de beschikbare instrumenten en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Aangezien het reeds bekend is welke medicatie valrisicoverhogend is en dat een gestructureerd medicatiereview een effectief onderdeel van de multifactoriële valanalyse is uit de recente literatuursearch van de Wereldrichtlijn Valpreventie, is de bewijsvoering en GRADE beoordeling van de Wereldrichtlijn valpreventie overgenomen in de aanbevelingen van de huidige richtlijn. Maar omdat het nog onduidelijk is welk instrument het beste gebruikt kan worden voor de uitvoer van een medicatiereview in het kader van valpreventie, iseen literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de voorspellende en diagnostische waarde van bestaande instrumenten om valrisicoverhogende medicatie te identificeren bij ouderen van 65 jaar en ouder. Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat, de voorspellende waarde, zijn negen studies geïncludeerd. Echter, de bewijskracht voor deze uitkomstmaat is zeer laag omdat het kleine observationele studies betreffen. Geen van de geïncludeerde studies rapporteert de diagnostische waarde van de instrumenten. Hier ligt een kennislacune.

Ten aanzien van diagnostische waarde is het nog onduidelijk welk instrument het beste in staat is om patiënten te identificeren die een hoog risico hebben om te vallen op basis van hun medicatiegebruik. Op basis van de gevonden literatuur kan er dan ook geen conclusie worden getrokken over welk instrument het beste kan worden gebruikt. Om toch antwoord te kunnen geven op deze vraag, worden argumenten ontleend aan aanpalende literatuur, internationale richtlijnen en expert opinion binnen de richtlijn werkgroep.

Naar aanleiding van de literatuursearch is in tabel 2 een overzicht gegeven van alle instrumenten die gebruikt kunnen worden om valrisicoverhogende medicatie in kaart te brengen als onderdeel van een medicatiereview. De meeste instrumenten zijn algemene medicatiereview instrumenten gericht op Potentially Inappropriate Medications (PIMs) en Potentially Omitted Medications (POMs) in de brede zin. Sommige hebben een specifieke sectie voor valrisicoverhogende medicatie (STOPP/START sectie K). Voor de STOPP/START lijst is ook een Nederlandse gevalideerde versie beschikbaar: STOPP/START NL 2020.

De werkgroep sluit zich aan bij de sterke aanbevelingen in de internationale richtlijn valpreventie (Montero-Odasso, 2022) om een gestructureerde medicatiebeoordeling met specifieke aandacht voor valrisicoverhogende medicatie, uit te voeren met behulp van een ondersteunend instrument. Bij voorkeur wordt hiervoor een instrument gebruikt dat (1) een lijst van alle relevante valrisicoverhogende medicatie behelst en daarnaast (2) ondersteuning biedt bij alle stappen van een gestructureerde medicatiebeoordeling. Hierdoor zijn instrumenten die zich op slechts één of enkele groepen valrisicoverhogende medicatie richten (zoals de DBI) minder geschikt voor deze toepassing. Een breder instrument zoals STEADI-Rx of STOPP-sectie K zijn vollediger, maar beperken zich tot een set veel voorgeschreven en/of zeer sterk valrisicoverhogende medicatie. Zodoende adviseert de werkgroep om het STOPPFall instrument als ondersteunend instrument in te zetten voor een gestructureerde medicatiebeoordeling in het kader van valpreventie. Dit omdat het:

1) Niet alleen een screeningslijst omvat maar ook alle stappen van medicatiebeoordeling per geneesmiddelgroep bevat en specifieke informatie geeft ten aanzien van diagnoses, klachten en symptomen die per geneesmiddelgroep in ogenschouw genomen moeten worden, inclusief een follow-up advies

2) ontwikkeld is met het specifieke doel om valrisicoverhogende medicatie te identificeren en zowel veel voorgeschreven als minder vaak voorgeschreven middelen bevat

3) gebaseerd is op de bestaande bewijsvorming in de literatuur aangevuld met input van Europese experts;

4) een uitgebreide Delphi procedure heeft doorlopen, met als gevolg een breed gedragen consensus van Europese en internationale experts.

Validatie van het instrument moet echter nog plaatsvinden, dit is een kennislacune.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Gezamenlijke besluitvorming is cruciaal bij medicatiebeoordeling en –optimalisatie in het kader van valpreventie. Er zijn aanwijzingen dat de kans op succes van medicatieafbouw hierdoor wordt vergroot (zie richtlijn Polyfarmacie, module minderen en stoppen van medicatie). Het betrekken van de patiënt(e) is zodoende een absolute voorwaarde voor het succes van minderen en stoppen van medicatie (richtlijn Polyfarmacie bij ouderen). Richtlijnen met bijbehorend patiënten informatiefolders over minderen en stoppen van medicatie kunnen kennis vergroten en helpen bij verwachtingenmanagement (richtlijn Polyfarmacie bij ouderen). Conform de gestructureerde stappen van medicatiebeoordeling dient bij besluitvorming ten aanzien van minderen en stoppen van medicijnen altijd meegenomen worden wat de wensen en doelen van een individuele patiënt(e) zijn (richtlijn Polyfarmacie bij ouderen, statementpaper T&F group (Van der Velde, 2023). Eerdere studies hebben laten zien dat veel ouderen met een verhoogd valrisico minder vallen en bijwerkingen verkiezen boven een lager cardiovasculair risico (Tinetti, 2008). In een algemene oudere populatie bleek ruim 75% zelfredzaamheid en behoud van functioneren te verkiezen boven overlijden, evenals boven pijn of andere symptomen (Fried, 2011). Goede individuele afstemming waar de behandeling op gericht is (levensverlengend, voorkomen van cardiovasculair event, voorkomen van vallen of verbeteren van fysiek functioneren bijvoorbeeld) is zodoende essentieel. Visuele instrumenten die patiënten kunnen helpen bij complexe medicatie-keuze momenten (wensen, doelen) kunnen hierbij helpen (richtlijn Polyfarmacie bij ouderen, Schuling, 2013; van Summeren, 2016; van Summeren, 2017).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

In het algemeen zijn er aanwijzingen dat minderen en stoppen van medicatie, ongeacht de setting waarin het gebeurt, kan leiden tot lagere directe geneesmiddelenkosten (MDR-polyfarmacie). Er is in de literatuur slechts een klein aantal economische evaluaties beschikbaar van interventies gericht op het minderen en stoppen van medicijnen bij thuiswonende ouderen. De meesten bleken kosteneffectief volgens de afkapwaarde van de WHO (Romano, 2022). Kosteneffectiviteitsstudies naar het toepassen van een instrument voor beoordeling van valrisicoverhogende medicatie ontbreken in de literatuur. Een systematische review liet wel zien dat in algemene zin (dus zonder focus op valrisicoverhogende medicatie) de toepassing van STOPP-START geneesmiddelkosten kan verlagen (Hill-Taylor, 2016). Ten aanzien van valrisicoverhogende medicatie zijn er aanwijzingen dat medicatie-gerelateerde valincidenten substantiële verborgen (gezondheidszorg-) kosten met zich meebrengen (Tannenbaum, 2015). Een Nederlandse studie heeft laten zien dat een gestructureerde beoordeling van valrisicoverhogende medicatie/afbouw en staken van valrisicoverhogende medicatie kosteneffectief was en zelfs leidde tot een aanzienlijke besparing van de kosten (netto €1.691 per patiënt of €491 per val) op korte termijn (van der Velde, 2007).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Zowel bij artsen als bij patiënten is er terughoudendheid ten aanzien van afbouw en stoppen van medicatie. Hierbij speelt zowel kennis ten aanzien van (prevalentie) van bijwerkingen (onderschatting) als kennis ten aanzien van beoogde effecten van de medicatie (overschatting) een rol (van der Velde, 2023). Gezondheidsvaardigheden van oudere patiënten en specifieke groepen spelen hierbij een rol. Dit behoeft extra aandacht. Een recente systematische review naar minderen en stoppen van medicijnen als enkelvoudige interventie in het kader van valpreventie liet zien dat de aanbevelingen van bijvoorbeeld een apotheker of klinische beslissingsondersteuning in beperkte mate werden opgevolgd door voorschrijvers (Seppala 2022). Ook de procesevaluaties van 2 recente grote RCTs naar het effect van medicatiereviews met STOPP/START V2 lieten zien dat implementatie niet succesvol was, onder meer als gevolg van terughoudendheid bij patiënten en behandelaars, alsmede transmurale informatieoverdracht en timing van de interventie (Blum, 2021; Dalton, 2020). Uit een recente Europese survey studie onder geriaters (in opleiding) kwam naar voren dat de belangrijkste barrières om medicatie te stoppen of te minderen waren: ontbreken bereidheid patiënten, angst voor negatieve gevolgen, gebrek aan tijd en slechte communicatie tussen voorschrijvers (Van Poelgeest, 2022). Factoren die minderen en stoppen van medicijnen juist bevorderen waren: betere informatie-uitwisseling tussen verschillende voorschrijvers, richtlijnen voor minderen en stoppen van medicijnen, en meer scholing en training (Van Poelgeest, 2022).

Implementatie strategieën voor het effectief minderen en stoppen van medicatie moeten zodoende gericht zijn op meerdere lagen van het gezondheidszorgsysteem. Eerder beschreven elementen/stappen voor implementatie van valpreventie die hierbij doorlopen kunnen worden zijn (1) creëer draagvlak, (2) breng de beginsituatie in kaart, (3) bepaal prioriteiten en doelstellingen, (4) werk acties uit, (5) evalueer en stuur bij en (6) veranker zoals beschreven in de module organisatie van zorg bij valpreventie ouderen en het handboek valkliniek (van der Velde, 2020). Daarnaast is het belangrijk dat het verwijsproces voor een medicatiebeoordeling voor ouderen met een hoog medicatie-gerelateerd valrisico eenvoudig moet zijn met zo min mogelijk tussenstappen, omdat bij iedere stap in het verwijsproces er uitval is (Bhasin, 2020; Bruce, 2021). Er is momenteel beperkte adaptatie in de implementatie van wetenschapsliteratuur naar het gebied van medicatiebeoordelingen en minderen en stoppen van medicatie (Ailabouni, 2022). Dit is een kennislacune.

Rationale van de Aanbevelingen

Aanbeveling-1

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Conform de voor deze richtlijn overgenomen GRADE literatuurbeoordeling van de recent gepubliceerde wereldrichtlijn valpreventie, is er sterk bewijs dat bepaalde medicatie het risico op vallen verhoogt (Montero-Odasso, 2022). In de wereldrichtlijn valpreventie wordt geconcludeerd dat een medicatiereview met passende afbouw is een bewezen effectief onderdeel van de multifactoriële valrisicobeoordeling en dient naar de mening van de werkgroep hier dan ook altijd onderdeel van uit te maken (GRADE 1B). Voor de effectiviteit van een medicatiereview als enkelvoudige interventie is geen bewijs. Daarom, en gezien de multifactoriële aard van vallen, is de mening van de werkgroep dat een medicatiereview altijd als onderdeel van een multifactoriële valrisicobeoordeling uitgevoerd moet worden. Dit geldt zowel bij thuiswonende ouderen als in de verpleeghuisetting, gezien juist de laatste groep een kwetsbare hoog-risico populatie betreft. Een Nederlandse studie heeft laten zien dat een gestructureerde beoordeling en afbouw van valrisicoverhogende medicatie kosteneffectief is en zelfs een aanzienlijke besparing van de kosten kan opleveren.

Aanbeveling-2

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

In de wereldrichtlijn valpreventie (Montero-Odasso, 2022) en de richtlijn Polyfarmacie bij ouderen wordt aanbevolen de medicatie op een gestructureerde wijze in kaart te brengen en daarbij ondersteunende instrumenten te gebruiken De werkgroep sluit zich bij deze aanbevelingen aan. Ondanks dat er op basis van de geïncludeerde geen sterk bewijs voor is gevonden ten faveure van een van de beschikbare instrumenten, is de werkgroep toch van mening dat een ondersteunend instrument van toegevoegde waarde is. In de praktijk is er vaak terughoudendheid ten aanzien van het afbouwen en stoppen van medicatie. Een ondersteunend instrument dat zowel een lijst van relevante valrisicoverhogende medicatie als een overzicht van de te nemen stappen bij beoordeling bevat, kan helpend zijn bij het afbouwen en stoppen. De voorkeur van de werkgroep valt hierbij op het STOPPFall instrument. Dit omdat dit instrument specifiek is ontwikkeld voor de identificatie van valrisicoverhogende medicatie en gebaseerd is op bestaande bewijsvorming aangevuld met de input van Europese experts. Ook bevat het instrument naast een screeningslijst ook alle stappen van medicatiebeoordeling per geneesmiddelengroep en specifieke informatie ten aanzien van diagnoses, klachten en symptomen die in ogenschouw genomen moeten worden, inclusief een follow-up advies. Er is voor dit instrument een uitgebreide Delphi procedure doorlopen, wat heeft geleid tot een breed gedragen consensus van experts. Het ontbreken van bereidheid van de patiënt is één van de belangrijkste barrières om medicatie te stoppen. Er zijn aanwijzingen dan de kans op succes van medicatieafbouw wordt vergroot door gezamenlijke besluitvorming. De werkgroep is dan ook van mening dat een gepersonaliseerde aanpak en gezamenlijke besluitvorming noodzakelijk zijn voor een succesvol minderen en stoppen van medicatie. Om weloverwogen keuzes te maken samen met de patiënt moet gewerkt worden volgens de gestructureerde stappen van medicatiebeoordeling. Hierin worden de wensen en doelen van de individuele patiënt meegewogen en wordt ook met de patiënt samen gekeken naar de indicatie, alternatieven, dosering, bijwerkingen en symptomen die opnieuw zouden kunnen optreden bij stoppen van een middel. In de STOPPFall is bij deze stappen de relevante informatie beschikbaar in beslisbomen (zie bijlage STOPPFall medicatielijst en adviezen voor medicatie afbouw). Een interactieve digitale versie van de beslisbomen is online beschikbaar via STOPPFall instrument. Een instrument moet gezien worden als een leidraad, maar is niet uitputtend. Individuele afwegingen van mogelijke bijwerkingen van andere groepen van medicatie die mogelijk het valrisico verhogen zijn essentieel. In de geneesmiddelenteksten van de EPHOR app (Expertisecentrum pharmacotherapie bij ouderen) worden mogelijke relevante bijwerkingen (zoals duizeligheid, orthostatische hypotensie, valrisico) in het kader van valrisico per geneesmiddel beschreven(Van der Velde, 2023; van Poelgeest, 2023; Korkatti-Puoskari, 2023; Capiau, 2022; Ilhan, 2023; Portlock, 2023; Welsh, 2023; Virnes; 2022; van Poelgeest, 2021).

Aanbeveling-3

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Zoals onder andere beschreven in de internationale richtlijn valpreventie (Montero-Odasso, 2022), de clinical review series overzichten en de richtlijn Polyfarmacie bij ouderen, kan medicatie n via verschillende mechanismen een val veroorzaken, onder andere als gevolg van bijwerkingen. Juist bij ouderen spelen medicatiebijwerkingen een belangrijke rol, dit door het veelvuldige gebruik van medicatie, polyfarmacie, waardoor een hoger risico op interacties. Daarnaast is er bij ouderen sprake van een toegenomen gevoeligheid voor bijwerkingen, door onder andere veranderde lichaamssamenstelling, veranderde receptorgevoeligheid en verminderde reservecapaciteit. De werkgroep is daarom van mening dat voorafgaand aan het voorschrijven van valrisicoverhogende medicatie een inschatting moet worden gemaakt van het valrisico (inclusief valhistorie). Dit moet worden meegenomen in de overweging om valrisicoverhogende medicatie te starten. Eventuele veiliger alternatieven moeten overwogen worden Als starten van valrisicoverhogende medicatie toch nodig is, moet gekozen worden voor de minimale effectieve dosis en een zo kort mogelijke duur.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Eén van de belangrijkste behandelbare valrisicofactoren is het gebruik van valrisicoverhogende medicatie (NL Richtlijn 2017; Hopewell, 2018; Montero-Odasso 2022;). Conform eerder gepubliceerde literatuur en richtlijnen bevestigt een recente systematische review met netwerkanalyse dat een beoordeling en aanpassing van valrisicoverhogende medicatie één van de effectieve onderdelen van de multifactoriële valrisicobeoordeling is (Dautzenberg, 2021). De recent (eind 2022) gepubliceerde wereldrichtlijn Valpreventie (Montero-Odasso, 2022) beveelt dan ook aan om standaard als onderdeel van de multifactoriële valrisicobeoordeling een gestructureerde medicatiereview met passende medicatieafbouw uit te voeren. Dit is in overeenstemming met de module Verlaging valrisico bij thuiswonende ouderen van de Nederlandse richtlijn ‘Preventie van valincidenten bij ouderen’. Er is veel onderzoek gedaan naar de associatie tussen verschillende medicatie groepen en valrisico. Psychotrope medicatie is een onafhankelijke risicofactor voor vallen. Ook anti-epileptica, anticholinergica en sommige klassen van cardiovasculaire medicatie zijn valrisico verhogend (Deandra, 2010; De Vries, 2018; Hartikainen, 2007; Leipzig, 1999a; Leipzig, 1999b; Park, 2015; Seppala, 2018a; Seppala, 2018b; Woolcott, 2009).

Mede gezien de onderliggende aandoening – die ook valrisicoverhogend kan zijn – is een gepersonaliseerde afweging ten aanzien van wel of niet afbouwen van het mogelijk valrisicoverhogende medicijn wenselijk (Montero-Odasso, 2022). Zodoende dient deze informatie meegenomen te worden in de medicatiebeoordeling, en de daaropvolgende besluitvorming om wel of niet af te bouwen. Gezien de complexiteit wordt een gestructureerde aanpak aanbevolen. In algemene zin wordt in de richtlijnmodule Medicatiebeoordeling van de richtlijn Polyfarmacie bij ouderen aanbevolen om bij een medicatiereview gestructureerde instrumenten te gebruiken. Dit is in overeenstemming met de wereldrichtlijn Valpreventie (Montero-Odasso, 2022).

In de huidige situatie wordt zowel door zorgverleners als door patiënten vallen als mogelijke medicatiebijwerking veelal niet herkend. Ook ontbreekt er een gevalideerde en gestructureerde aanpak voor uitvoering van de medicatiereview in het kader van valpreventie. Het is onduidelijk of en welk instrument hiervoor het beste gebruikt kan worden. Ook is het onduidelijk hoe het vervolg na medicatieafbouw in het kader van valpreventie er idealiter uit zou moeten zien.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the predictive value of risk for falls based on a medication review tool when compared with no tool or another tool in older adults (≥ 65 years old). Source: Blalock, 2020a; Byrne, 2019; Cardwell, 2020; Damoiseau-Volman, 2022; Lavrador, 2021; Lukazewski, 2012; Nyborg, 2017; Prudent, 2008; Stewart, 2021 |

|

no GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the diagnostic accuracy of a medication review tool when compared with no tool or another tool in older adults (≥ 65 years old). Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Blalock (2020a) examined the association between the drug burden index (DBI) and medication-related fall risk using a retrospective cohort study design. Adults (age 65 or older) using four or more chronic medications or at least one medication associated with an increased risk of falling were included from community pharmacies (n=1562). Pharmacy staff screened patients by asking the following key questions derived from the Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, & Injuries (STEADI) Initiative:

- Have you fallen in the past year?

- Do you feel unsteady when standing or walking?

- Do you worry about falling?

In addition, patients who reported one or more falls within the past year were asked if any of the falls had resulted in injury. Patients who answered ‘yes’ to any of the key STEADI questions were classified as having screened positive for increased fall risk. These patients were eligible to receive medication review provided by a pharmacist using evidence-based algorithms developed by the study team to 1) identify medications associated with an increased risk of falling, and 2) provide therapeutic recommendations to reduce risk. In total, 1058 of the included patients were screened for fall risk using the STEADI questions. The DBI was used to assess each participant’s cumulative exposure to medications with anticholinergic or sedative properties during the 1-year follow-up time. The DBI is a validated measure used to assess a person’s total exposure to medications with anticholinergic and sedative properties. The following relevant outcome measure was reported: predictive value.

Byrne (2019) validated the drug burden index (DBI) by examining the association of the DBI score with important health outcomes in Irish community-dwelling older people. This was a cohort study using data from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) with linked pharmacy claims data. Individuals aged ≥65 years participating in TILDA and enrolled in the General Medical Services scheme were eligible for inclusion. The drug burden index (DBI) score was determined by applying the DBI tool to participants’ medication dispensing data. In total, 1924 participants were included, and the outcomes were assessed at the time of interview (cohort 1). The DBI is a validated measure used to assess a person’s total exposure to medications with anticholinergic and sedative properties. The follow-up was 12 months. The following relevant outcome measure was reported: predictive value.

Cardwell (2020) aimed to determine whether a higher DBI was associated with poorer outcomes (hospitalization, falls, mortality, cognitive function, and functional status) over 36 months follow-up. Data from the Life Living in Advanced Age, a Cohort study in New Zealand (LiLACS NZ) was used for this study. LiLACS NZ consist of two cohorts: Māori (the Indigenous population of New Zealand) aged ≥80 years and non-Māori aged 85 years at the time of enrolment. For this guideline module, only the non-Māori population was included to increase the generalizability of the study towards the Dutch population. In total, 404 non-Māori patients were included at baseline. Medications with anticholinergic and/or sedative properties (i.e. medications with a DBI > 0) were identified using the Monthly Index of Medical Specialities (MIMS) medication formulary, New Zealand. The DBI was calculated for everyone enrolled at each time point. The DBI is a validated measure used to assess a person’s total exposure to medications with anticholinergic and sedative properties. The follow-up was 36 months. The following relevant outcome measure was reported: predictive value.

Damoiseaux-Volman (2022) investigated the effect of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) on inpatient falls and to identify whether PIMs as defined by STOPPFall, STOPP/START v2, or the designated section K for falls of STOPP v2 have a stronger association with inpatient falls when compared to the general tool STOPP v2. The STOPPFAll is an instrument to identify fall risk inducing drugs. STOPP/START is a general list with potentially inappropriate drugs, including a designated section K, which is a specific section to identify high risk fall risk inducing drugs. This retrospective observational study used an electronic health records dataset of patients ≥70 years admitted to an academic hospital due to a fall. In total, 16,687 patients were included in this study. The PIM exposure was calculated as the number of PIMs (sum of the unique PIMs each day) administered during hospital stay, divided by the hospital length of stay in days. The follow-up was at least 24 hours but was not further specified. The following relevant outcome measure was reported: predictive value.

Nyborg (2017) performed a cross-sectional observation study and assessed the level of inappropriate medication use in older nursing home residents in Norway according to the NORGEP-NH (≥ 65 years old). The NORGEP criteria were developed in Norway in 2008, intended for use in general practice and for a home-dwelling older population. In order to have an updated tool for assessment of medication use in nursing homes that was also suited for the Norwegian pharmaceutical market, the NORGEP-NH criteria were developed. The NORGEP-NH criteria consist of three parts: single substance criteria (criteria to avoid for regular use whenever possible), combination criteria (criteria of drug combinations that should be avoided when possible), and deprescribing criteria (criteria for continuation). The participants in the study constitute the part of the nursing home population in need of antibiotic or intravenous fluid therapy during the study period. In total, 881 patients were included. All these patients were evaluated according to the NORGEP-NH criteria. There was no control group available. The length of follow-up was not specified. The following relevant outcome measure was reported: predictive value.

Lavrador (2020) evaluated the effect size of the associations between the anticholinergic scales on cumulative anticholinergic burden instruments with peripheral or central anticholinergic adverse outcomes in older patients. This case-control study was conducted in patients over 65 years who were admitted to two internal medicine wards of a Portuguese university hospital. The Anticholinergic Drug Scale (ADS), Anticholinergic Risk scale (ARS), Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale (ACBS), and Drug Burden Index (DBI) were used to calculate the patients’ anticholinergic burden. In total, 250 patients were included. There is no control group available. The association between falls in the preceding 6 months and the anticholinergic burden scales scores were reported. The length of follow-up was not specified. The following relevant outcome measure was reported: predictive value.

Lukazewski (2012) evaluated the effectiveness of a web-based program, Monitor-Rx, in identifying adults at risk for drug-related geriatric syndromes or inappropriate medicines. One of the geriatric problems that Monitor-Rx could identify is falls. This prospective pilot study compared medication-related risks generated by the Web-based program with those identified by a certified geriatric pharmacist (CGP). Eligible patients were members of Supporting Active Independent Lives (SAIL), a community-based grass roots organization intended to help older adults age in place in their homes. Monitor-Rx correlates medication effects with physical, functional, and cognitive decline in older adults by identifying medications as a cause or aggravating factor contributing to common geriatric conditions. The program also identifies medications with anticholinergic effects and medications inappropriate for use in older adults (≥ 65 years old). The study compared the incidence of falls identified by the Monitor-Rx versus identification by the GCP. In total, 29 patients were included. The participants were not followed-up over time. The following relevant outcome measure was reported: predictive value.

Prudent (2008) studied the consumption of potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) among patients aged ≥75 years, paying particular attention to psychotropic drugs and the factors influencing the use of potentially inappropriate psychotropics (PIPs). This cross-sectional analysis of a prospective multicenter cohort including 1176 hospitalized French patients aged ≥75 years. The Beers list as updated in 2003 defined which medications were considered PIPs. There was no follow-up as the analysis is cross-sectional. The following relevant outcome measure was reported: predictive value.

Stewart (2021) compared the evidence behind anticholinergic burden (ACB) measures in relation with their ability to predict risk of falling in older people. Medline (OVID), EMBASE (OVID), CINAHL (EMBSCO) and PsycINFO (OVID) were searched from 2006 until september 2020. Inclusion criteria included: participants aged 65years and older, use of one or more ACB measure(s) as a prognostic factor, cohort or case-control in design, and reporting falls as an outcome. In total, 8 studies reporting temporal associations between ACB and falls were included. The identified ACB measures were the anticholinergic cognitive burden scale (ACBS) and the anticholinergic risk score (ARS). The evidence supports an association between moderate to high ACB and risk of falling in older people, but no conclusion can be made regarding which ACB scale offers best prognostic value in older people. The following relevant outcome measure was reported: predictive value.

Sixteen studies did not comply with the PICO and were therefore not included in the literature summary and GRADE assessment. The data of these studies is not incorporated in the Evidence tables and risk of bias tables as these studies did not report the relevant outcome measures. To be able to give an overview of all available instruments to identify fall-risk increasing drugs, the studies are described shortly below. Table 2 gives an overview of all available instruments for medication review.

Ackroyd-Stolarz (2009) examined the association between potentially inappropriate prescribing of benzodiazepines, as defined by the Beers criteria, by older adults (at least 65 years of age) and the risk of having a fall during acute inpatient care.

Aizenberg (2002) retrospectively assessed the characteristics of older psychiatric inpatients (≥ 65 years old) that had sustained a fall during hospitalization. Patients that were aged ≥65 years and intact cognition were included in the study. The control group consisted of the previous and next admission of an older patient to the same ward. The anticholinergic burden score (ABS) was calculated for each patient.

Arnold (2017) conducted a retrospective chart review covering all patients aged ≥ 65 years who were admitted to Evangelisches Krankenhaus Göttingen-Weende. Potentially inappropriate psychotropic drugs were identified according to the PRISCUS list. The PRISCUS list is an expert opinion-based general list of potentially inappropriate drugs in older adults (≥ 65 years old) that is currently used as a guideline in Germany. Psychotropic drugs that were prescribed in this study were antipsychotics, antidepressants, Z-drugs and benzodiazepines. In total, 2130 patients were included.

Blalock (2020b) evaluated the effects of a community pharmacy-based fall prevention intervention (STEADI-Rx) on the risk of falling and use of medications associated with an increased risk of falling. This randomized controlled trial included adults (age ≥ 65 years) using either four or more chronic medications or one or more medications associated with an increased risk of falling and continuous insurance coverage through Medicare Part D and NC Medicaid for the entire study period. Pharmacy staff screened patients for fall risk using questions from the Stopping Elderly Accidents Deaths and Injuries (STEADI) algorithm. The Steady-Rx includes tricyclic antidepressants, antispasmodics, antihistamines, sedative hypnotics, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, opioid, antipsychotics, and antidepressants. Patients who screened positive were eligible to receive a pharmacist-conducted review, with recommendations sent to patient’s healthcare providers following the review. In total, 1,467 patients were included, of which 1000 were screened and 467 of the patients were not screened.

Cardwell (2015) identified tools used to quantify anticholinergic medication burden and aimed to determine the most appropriate tool for use in longitudinal research, conducted in those aged 80 years and older. An electronic search was performed in Ovid Medline, Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and international Pharmaceutical Abstracts from the inception of each database until February 2015. Inclusion criteria were published in the English literature, including populations with an average age ≥ 80 years, studies with an intention to quantify anticholinergic medication burden, and those with outcome measures that included at least one of the clinical outcome measures of interest (cognitive function, physical function, frequency of falls, hospitalization, and all-cause mortality).

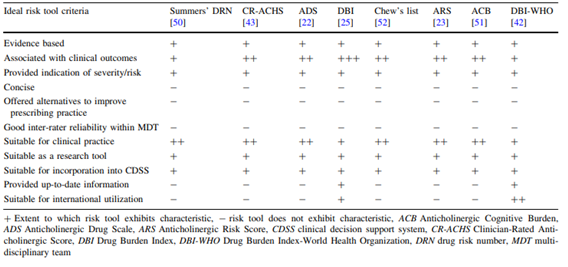

In total, 13 studies were eligible for inclusion and 8 tools were identified. The identified tools were Drug Burden Index (DBI), modified Anticholinergic Risk Scale (mARS), Drug Burden Index-World Health Organization (DBI-WHO), Clinician-Rated Anticholinergic Score (CR-ACHS), Summers’ Drug Risk Number (DRN), Anticholinergic Drug Scale (ADS), Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden (ACB) score, Anticholinergic Risk Scale (ARS), and Chew’s list. The criteria used to identify the most appropriate tool for use in longitudinal research are shown below (Table 1). The drug burden index (DBI) exhibited most of the key attributes of an ideal anticholinergic risk tool.

Table 1. Criteria used to identify the most appropriate tool for use in longitudinal research. From: Cardwell (2015).

Di Martino (2020) applied the Beers (2015 version), STOPP/START criteria (2014 version) and Improving Prescribing in the Elderly Tool (IPET) criteria (2000 version) as key tool to improve the quality of prescribing. The Beers, STOPP/START, and IPET criteria are general lists of potentially inappropriate drugs. Adult patients (≥65 years old) admitted to the Mediterranean Institute for Transplantation and Advanced Specialists Therapies were included. These criteria were used to assess the medication use in older patients in terms of PIMs and PPOs.

Di Martino (2020) applied the Beers (2015 version), STOPP/START criteria (2014 version) and Improving Prescribing in the Elderly Tool (IPET) criteria (2000 version) as key tool to improve the quality of prescribing. The Beers, STOPP/START, and IPET criteria are general lists of potentially inappropriate drugs. Adult patients (≥65 years old) admitted to the Mediterranean Institute for Transplantation and Advanced Specialists Therapies were included. These criteria were used to assess the medication use in older patients in terms of PIMs and PPOs.

Frankenthal (2014) assessed the effect of a Screening Tool of Older Persons potentially inappropriate Prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment (STOPP/START) medication intervention on clinical and economic outcomes. The STOPP/START is a general list with potentially inappropriate drugs, including section K specific for fall risk inducing drugs. This parallel group randomized trial was performed in a chronic care geriatric facility. Residents aged 65 and older prescribed with at least one medication (N=359) were randomized to receive usual pharmaceutical care or undergo medication intervention. The intervention group (N=183) received a medication review by the study pharmacist at study opening, and at 6 and 12 months. The STOPP/START criteria were applied to identify potentially inappropriate prescriptions (PIPs) and potentially prescription omissions (PPOs). The control group (N=176) received usual pharmaceutical care. The follow-up was 12 months. The following relevant outcome measure was reported: predictive value (accepted recommendations by physician).

Frankenthal (2016) assessed the effect of a Screening Tool of Older Persons potentially inappropriate Prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment (STOPP/START) medication intervention on clinical and economic outcomes at 24-months of follow-up. The STOPP/START is a general list with potentially inappropriate drugs, including section K specific for fall risk inducing drugs. For study details, see Frankenthal (2014).

Jamieson (2019) evaluated the association between the Drug Burden Index (DBI) and hip fractures, after correcting for mortality and multiple potential confounding factors. Patients included home-based people aged 65 years and older. The DBI exposure was calculated for medicines with anticholinergic and sedative properties. The DBI is a validated measure used to assess a person’s total exposure to medications with anticholinergic and sedative properties. In total, 70,553 individuals from a community-dwelling older population were included in the study.

Kimura (2016) evaluated the prevalence of PIMs and the efficacy of hospital pharmacists’ assessment and intervention based on STOPP criteria version 2. New inpatients aged ≥65 years who were prescribed ≥1 daily medicine were included in the study. Pharmacists assessed and detected PIMs based on STOPP criteria version 2 and considered the patient’s intention to change the prescription at the time of admission of each patient. The pharmacist and doctors discussed and finally decided whether or not to change the PIMs or not. A total of 822 patients were included in this study. Patients were not followed-up over time. The STOPP v2 is a general list with potentially inappropriate drugs, including section K specific for fall risk inducing drugs.

McMahon (2014) performed a before-and-after cohort study to assess if prescribing modification occurs in older people presenting to an emergency department due to a fall over a 4-year period. In total, 1016 patients were included in the study. The STOPP screening tool and Beers prescribing criteria were applied to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing. The individual STOPP, STOPP section K, psychotropic medication, and beers criteria were compared in the 12 months pre- and post-fall. The STOPP is a general list of potentially inappropriate drugs. STOPP includes a section K specific for fall risk inducing drugs.

Onatade (2013) determined the prevalence and types of potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) in older people admitted to and discharged from an Acute UK hospital and to determine how often PIMs prescribed on discharge are accompanied by a plan for follow-up. Patients aged ≥65 years admitted to the Specialist Health and Ageing Unit were included. Data were obtained by applying STOPP criteria to electronic admission and discharge medication lists. In total, the admission and discharge medication lists were assessed for 195 patients. STOPP is a general list of potentially inappropriate drugs. STOPP includes a section K specific for fall risk inducing drugs. STOPP includes a section K specific for fall risk inducing drugs. Section K PIMS were among the most common identified PIMS on admission and discharge.

Seppala (2021) describes a comprehensive STOPPFall by Delphi consensus by a European expert group. The STOPPFall was created by two facilitators based on evidence from recent meta-analyses and national fall prevention guidelines in Europe. Twenty-four panelists chose their level of agreement on a Likert scale with the items in the STOPPFall in three Delphi panel rounds. A threshold of 70% was selected for consensus a priori. The panelists agreed on 14 medication classes to be included in the STOPPFall, including benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, benzodiazepine-related drugs, opioids, antidepressants, anticholinergics, antiepileptics, diuretics, alpha-blockers used as antihypertensives, alpha-blockers for prostate hyperplasia, centrally acting antihypertensives, antihistamines, vasodilators used in cardiac diseases, and overactive bladder and urge incontinence medications. They indicated 18 differences between pharmacological subclasses regarding fall-risk-increasing properties. In addition, practical deprescribing guidance was developed for STOPPFall medication classes.

Shaver (2020) determined whether there was an increase in fall risk increasing drug prescribing and if this is concurrent with an increase in fall-related mortality in persons 65 years and older in the United States. This serial cross-sectional analysis utilized data from both the National Vital Statistics System, as the medical expenditure panel survey for years 1999-2017. Adults aged 65 years and older were evaluated for death due to falls and for prescription fills of fall risk increasing drugs using the STEADI-Rx tool. The STEADI-Rx tool is a specific list of fall risk increasing drugs, comprising of the following FRID: tricyclic antidepressants, antispasmodics, antihistamines, sedative hypnotics, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, opioid, antipsychotics, and antidepressants. The analysis included 374.972 fall-related mortalities and 7.858.177.122 fills of fall risk increasing drugs.

Thevelin (2019) aimed to compare the prevalence and types of drug-related admissions identified by STOPP/START version 1 and STOPP/START version 2. The STOPP/START is a general list with potentially inappropriate drugs, including section K specific for fall risk inducing drugs. They applied the STOPP/START version 2 criteria to a subset of 100 consecutively admitted geriatric patients selected from our original cross-sectional study of 302 patients. A geriatrician and a pharmacist adjudicated whether the identified PIMs and PPOs were related to acute hospitalization.

Walsh (2019) performed a before-and-after cohort study to explore patterns of relevant potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people with fall-related hospitalizations. Adults hospitalized due to a fall, fracture, or syncope were included in the study. For participants who experiences more than one fall-related hospitalization, only the first eligible record was selected to avoid overlapping and interdependence of observations. In total, 927 individuals were identified as having a fall-related hospitalization within the study timeframe and had prescription data available. These individuals were included in the study. Fall-related prescribing was defined using the STOPP/START section K. Medication use including sedatives (benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, and neuroleptics), vasodilators, and vitamin D was compared prior and post hospitalization.

Table 2. Overview of instruments to identify fall-risk inducing drugs

|

Reference |

Tool |

Population of interest |

Brief description |

|

Aizenberg, 2002 |

ABS |

Adults aged ≥65 years |

Tool to assess the anticholinergic burden. |

|

Stewart, 2021 Lavrador, 2021 |

ACBS |

Adults aged ≥65 years |

Tool to assess the anticholinergic burden. |

|

Stewart, 2021 Lavrador, 2021 |

ARS |

Adults aged ≥65 years |

Tool to assess the anticholinergic burden. |

|

Lavrador, 2021 |

ADS |

Adults aged ≥65 years |

Tool to assess the anticholinergic burden. |

|

McMahon, 2014 Prudent, 2008 Di Martino, 2020 Ackroyd-Stolar, 2009 |

Beers list |

Adults aged > 70 years |

Screening tools to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIPs). Including a section on fall-risk increasing drugs. |

|

Byrne, 2019 Cardwell, 2020 Blalock, 2020a Jamieson, 2018 Lavrador, 2021 |

DBI |

Adults aged ≥65 years |

The DBI is a risk assessment tool to quantify older individuals’ cumulative exposure to medications with clinically significant anticholinergic and/or sedative effects. |

|

Di Martino, 2020 |

IPET |

Adults aged ≥65 years |

The IPET criteria (2000 version) consist of a list of 14 PIMs identified by a panel of Canadian experts. |

|

Arnold, 2017 |

PRISCUS |

Adults aged ≥65 years |

A list of potentially inappropriate drugs in older adults (≥ 65 years old) that is currently used as a guideline in Germany. |

|

Blalock, 2020a, Blalock, 2020b Shaver, 2020 |

STEADI-Rx |

Adults aged ≥65 years |

The STEADI algorithm is adapted for use in the community pharmacy setting and provides a list of fall-risk increasing drugs. |

|

Frankenthal, 2014 Frankenthal, 2016 Walsh, 2019 Di Martino, 2020 |

STOPP-START |

Adults aged ≥65 years |

Screening tool to identify potentially inappropriate prescriptions (PIPs) and potential prescription omissions (PPOs). In section K fall-risk increasing drugs are listed. |

|

Thevelin, 2019 |

STOPP/START version 2 |

Adults aged ≥65 years |

Screening tool to identify potentially inappropriate prescriptions (PIPs) and potential prescription omissions (PPOs). In section K fall-risk increasing drugs are listed. |

|

McMahon, 2014 Onatade, 2013 |

STOPP |

Adults aged >65 years |

Screening tools to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIPs). In section K fall-risk increasing drugs are listed. |

|

Kimura, 2016 Damoiseaux-Volman, 2022 |

STOPP version 2 |

Hospital patients who were prescribed ≥1 daily medicine |

Screening tool to identify potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs). In section K fall-risk increasing drugs are listed. |

|

Damoiseaux-Volman, 2022 |

Section K for falls of STOPP version 2 |

Adults aged ≥70 years |

Screening tools to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIPs). This section contains fall-risk increasing drugs. |

|

Seppala, 2021 Damoiseaux-Volman, 2022 |

STOPPFall |

Older adults with high fall risk |

Comprehensive screening tool developed by Delphi consensus to identify fall risk increasing drugs and practical deprescribing guidance for STOPPFall medication classes. Consensus was achieved for 14 medication classes to create a comprehensive list of fall-risk inducing drugs. |

|

Lukozewski, 2012 |

Monitor-Rx |

Eligible patients were members of Supporting Active Independent Lives (SAIL), a community-based grass roots organization intended to help older adults age in place in their homes. |

Web-based program which associates medication effects with geriatric problems (including falls) to identify older adults at risk who would benefit from a comprehensive or targeted medication review. The program also identified medications with anticholinergic effects and medications inappropriate for use in older adults (≥ 65 years old). |

|

Nyborg, 2017 |

NORGEP-NH criteria |

The participants in the study constitute the part of the nursing home population in need of antibiotic or intravenous fluid therapy during the study period |

Screening tool to identify substances to avoid for regular use, drug combinations that should be avoided, and criteria for continuation. In section A and B, several fall-risk inducing drugs are listed. |

ABS: anticholinergic burden score, ACBS: anticholinergic cognitive burden scale, ARS: anticholinergic risk score, ADS: Anticholinergic Drug Scale, DBI: Drug Burden Index, IPET: Improving Prescribing in the Elderly Tool, STEADI: Stopping Elderly Accidents Deaths and Injuries, STEADI-Rx: Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries-Rx, STOPP: Screening Tool of Older Persons potentially inappropriate Prescriptions, STOPP-START: Screening Tool of Older Persons potentially inappropriate Prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment, NORGEP-N: Norwegian General Practice Nursing Home, PIPs: potentially inappropriate prescribings, PPOs: potential prescription omissions.

Results

Predictive value of risk for falls based on a medication review tool

Nine studies reported the predictive value at risk for falls based on risk medication use according to the respectively assessed tools (Blalock, 2020a; Byrne, 2019; Cardwell, 2020; Damoiseau-Volman, 2022; Lavrador, 2021; Lukazewski, 2012; Nyborg, 2017; Prudent, 2008; Stewart, 2021). The included studies presented the predictive value as association (OR, RR or AUC) between scores on a medication review tool and outcomes (falls). Due to study heterogeneity, the results were not pooled.

Blalock (2020a) reported the predicting odds of screening positive for fall risk for a low (0 to < 0.20), moderate (0.20 to <0.50), high (0.50 to < 1.0) and very high DBI (≥1.0). The adjusted odds ratio (OR) for a low DBI was 1.55 (95%CI 1.00 to 2.39), for a moderate DBI 2.41 (95%CI 1.54 to 3.78), for a high DBI 3.08 (2.02 to 4.69), and for a very high DBI 3.27 (95%CI 2.07 to 5.16). The OR was adjusted for age, prescription fills and sex. This suggests that there was an association between the DBI and positive fall risk screening.

Byrne (2019) reported the association of the DBI score with the adverse health outcome falls (one or more self-reported falls in the previous 12 months). Patients with a low DBI score (>0 to <1) had an OR of 1.40 (95%CI 1.08 to 1.81), and patients with a high DBI score (≥1) had an OR of 1.50 (95%CI 1.03 to 2.18). This suggests that there was an association between the DBI and the adverse health outcome falls.

Cardwell (2020) reported the association between a higher DBI at baseline and an increased rate of falls at 12, 24 and 26 months of follow-up: RR 1.09 (95%CI 0.76 to 1.56), RR 1.06 (95%CI 0.75 to 1.51), and RR 1.13 (95%CI 0.80 to 1.62), respectively. This suggests that there was an association between the DBI and the adverse health outcome falls.

Damoiseaux-Volman (2022) reported the effect of exposure to potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) on falls. The adjusted OR for STOPP was 2.24 (95%CI 2.01 to 2.49), the adjusted OR for STOPP Section K (= section Fall risk increasing drugs) was 7.89 (95%CI 6.06 to 10.26), and the adjusted OR for STOPPFall was 1.42 (95%CI 1.30 to 1.54). This suggests there was an association between the PIM exposure identified with different tools and falls.

Nyborg (2017) reported the association with potentially inappropriate medications according to the NORGEP-NH single substance and combined criteria and falls (adjusted OR 1.10 (95%CI 0.76 to 1.36). This suggests that there was an association between the NORGEP-NH criteria and falls.

Lukazewski (2012) reported the predictive value of the Monitor-Rx instrument and compared this with the judgement of a certified geriatric pharmacist (CGP). In total, all 29 patients included in the study were identified at risk for falls by both Monitor-Rx and the CGP. The predictive value for the outcome measure at risk for falls is 100%.

Lavrador (2021) reported the effect sizes (measured as areas under the curve) of the association between anticholinergic burden scales scores and the occurrence of the anticholinergic adverse outcome falls. The AUC of the ADS was 0.527 (95%CI 0.434 to 0.620), the AUC of the ARS was 0.591 (95%CI 0.496 to 0.687), the AUC of the ACB was 0.524 (95%CI 0.428 to 0.619), and the AUC of the DBI was 0.569 (0.477 to 0.662). This suggests that the anticholinergic burden scales alone are poor predictors for fall risk.

Prudent (2008) reported the association between patients taking psychotropics with at least one potentially inappropriate psychotropic (PIP) identified using the 2003 Beers list and fall risk (adjusted OR 1.1, 95%CI 0.8 to 1.6). This suggests that there was an association between the predictive value of the Beers list and falls.

The systematic review from Stewart (2021) reported the pooled analysis of adjusted HR, suggesting a modest increase in risk of falling attributed to the anticholinergic burden (HR 1.21, 95%CI 1.08 to 1.36). This suggests that there is an association between the anticholinergic burden scores and risk of falling.

Diagnostic accuracy

None of the included studies reported the outcome measure diagnostic accuracy.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for the outcome measure predictive value comes from an RCT and observational studies and therefore starts low. The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and because of a low number of included patients (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is therefore very low.

The level of evidence for the outcome measure diagnostic accuracy could not be established as none of the included studies reported the outcome measure.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the predictive/diagnostic value of using an instrument to identify and/or reduce fall-risk increasing drugs in older adults (≥ 65 years old)?

| P: patients | Adults (≥ 65 years old) |

| I: intervention | Instrument to identify fall-risk increasing drugs |

| C: control | No instrument or comparison between instruments |

| O: outcome measure | Predictive value of risk for falls based on a medication review tool, diagnostic value |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered the predictive value as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and the diagnostic value as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following differences as a minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

- Predictive value: prevention of every single fall is clinically relevant for older adults.

- Diagnostic value: A difference of 10% in diagnostic value was considered clinically relevant.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 07 June 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 497 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews or comparative studies on instruments to identify fall-risk inducing risks in adults ≥ 65 years old. In total, 59 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 50 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 9 studies were included.

Results

Nine studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Ackroyd-Stolarz S, Mackinnon NJ, Sketris I, Sabo B. Potentially inappropriate prescribing of benzodiazepines for older adults and risk of falls during a hospital stay: a descriptive study. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009 Jul;62(4):276-83. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v62i4.808. PMID: 22478905; PMCID: PMC2826959.

- Ailabouni NJ, Reeve E, Helfrich CD, Hilmer SN, Wagenaar BH. Leveraging implementation science to increase the translation of deprescribing evidence into practice. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2022 Mar;18(3):2550-2555. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.05.018. Epub 2021 Jun 6. PMID: 34147372.

- Aizenberg D, Sigler M, Weizman A, Barak Y. Anticholinergic burden and the risk of falls among elderly psychiatric inpatients: a 4-year case-control study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002 Sep;14(3):307-10. doi: 10.1017/s1041610202008505. PMID: 12475091.

- Arnold I, Straube K, Himmel W, Heinemann S, Weiss V, Heyden L, Hummers-Pradier E, Nau R. High prevalence of prescription of psychotropic drugs for older patients in a general hospital. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017 Dec 4;18(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s40360-017-0183-0. PMID: 29202811; PMCID: PMC5715648.

- Bhasin S, Gill TM, Reuben DB, Latham NK, Ganz DA, Greene EJ, Dziura J, Basaria S, Gurwitz JH, Dykes PC, McMahon S, Storer TW, Gazarian P, Miller ME, Travison TG, Esserman D, Carnie MB, Goehring L, Fagan M, Greenspan SL, Alexander N, Wiggins J, Ko F, Siu AL, Volpi E, Wu AW, Rich J, Waring SC, Wallace RB, Casteel C, Resnick NM, Magaziner J, Charpentier P, Lu C, Araujo K, Rajeevan H, Meng C, Allore H, Brawley BF, Eder R, McGloin JM, Skokos EA, Duncan PW, Baker D, Boult C, Correa-de-Araujo R, Peduzzi P; STRIDE Trial Investigators. A Randomized Trial of a Multifactorial Strategy to Prevent Serious Fall Injuries. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul 9;383(2):129-140. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002183. PMID: 32640131; PMCID: PMC7421468.

- Blalock SJ, Renfro CP, Robinson JM, Farley JF, Busby-Whitehead J, Ferreri SP. Using the Drug Burden Index to identify older adults at highest risk for medication-related falls. BMC Geriatr. 2020a Jun 12;20(1):208. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01598-5. PMID: 32532276; PMCID: PMC7291506.

- Blalock SJ, Ferreri SP, Renfro CP, Robinson JM, Farley JF, Ray N, Busby-Whitehead J. Impact of STEADI-Rx: A Community Pharmacy-Based Fall Prevention Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020b Aug;68(8):1778-1786. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16459. Epub 2020 Apr 21. PMID: 32315461.

- Blum MR, Sallevelt BTGM, Spinewine A, O'Mahony D, Moutzouri E, Feller M, Baumgartner C, Roumet M, Jungo KT, Schwab N, Bretagne L, Beglinger S, Aubert CE, Wilting I, Thevelin S, Murphy K, Huibers CJA, Drenth-van Maanen AC, Boland B, Crowley E, Eichenberger A, Meulendijk M, Jennings E, Adam L, Roos MJ, Gleeson L, Shen Z, Marien S, Meinders AJ, Baretella O, Netzer S, de Montmollin M, Fournier A, Mouzon A, O'Mahony C, Aujesky D, Mavridis D, Byrne S, Jansen PAF, Schwenkglenks M, Spruit M, Dalleur O, Knol W, Trelle S, Rodondi N. Optimizing Therapy to Prevent Avoidable Hospital Admissions in Multimorbid Older Adults (OPERAM): cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2021 Jul 13;374:n1585. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1585. Erratum in: BMJ. 2022 Dec 1;379:o2859. PMID: 34257088; PMCID: PMC8276068.

- Bruce J, Hossain A, Lall R, Withers EJ, Finnegan S, Underwood M, Ji C, Bojke C, Longo R, Hulme C, Hennings S, Sheridan R, Westacott K, Ralhan S, Martin F, Davison J, Shaw F, Skelton DA, Treml J, Willett K, Lamb SE. Fall prevention interventions in primary care to reduce fractures and falls in people aged 70 years and over: the PreFIT three-arm cluster RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2021 May;25(34):1-114. doi: 10.3310/hta25340. PMID: 34075875; PMCID: PMC8200932.

- Byrne CJ, Walsh C, Cahir C, Bennett K. Impact of drug burden index on adverse health outcomes in Irish community-dwelling older people: a cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2019 Apr 29;19(1):121. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1138-7. PMID: 31035946; PMCID: PMC6489229.

- Capiau A, Huys L, van Poelgeest E, van der Velde N, Petrovic M, Somers A; EuGMS Task, Finish Group on FRIDs. Therapeutic dilemmas with benzodiazepines and Z-drugs: insomnia and anxiety disorders versus increased fall risk: a clinical review. Eur Geriatr Med. 2022 Dec 28. doi: 10.1007/s41999-022-00731-4. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36576689.

- Cardwell K, Hughes CM, Ryan C. The Association Between Anticholinergic Medication Burden and Health Related Outcomes in the 'Oldest Old': A Systematic Review of the Literature. Drugs Aging. 2015 Oct;32(10):835-48. doi: 10.1007/s40266-015-0310-9. PMID: 26442862.

- Cardwell K, Kerse N, Ryan C, Teh R, Moyes SA, Menzies O, Rolleston A, Broad J, Hughes CM. The Association Between Drug Burden Index (DBI) and Health-Related Outcomes: A Longitudinal Study of the 'Oldest Old' (LiLACS NZ). Drugs Aging. 2020 Mar;37(3):205-213. doi: 10.1007/s40266-019-00735-z. PMID: 31919805.

- Craftman ÅG, Johnell K, Fastbom J, Westerbotn M, von Strauss E. Time trends in 20 years of medication use in older adults: Findings from three elderly cohorts in Stockholm, Sweden. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016 Mar-Apr;63:28-35. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.11.010. Epub 2015 Nov 28. PMID: 26791168.

- Dalton K, Curtin D, O'Mahony D, Byrne S. Computer-generated STOPP/START recommendations for hospitalised older adults: evaluation of the relationship between clinical relevance and rate of implementation in the SENATOR trial. Age Ageing. 2020 Jul 1;49(4):615-621. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa062. PMID: 32484853.

- Damoiseaux-Volman BA, Raven K, Sent D, Medlock S, Romijn JA, Abu-Hanna A, van der Velde N. Potentially inappropriate medications and their effect on falls during hospital admission. Age Ageing. 2022 Jan 6;51(1):afab205. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afab205. PMID: 34673915; PMCID: PMC8753037.

- Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F, Foschi R, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2010 Sep;21(5):658-68. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e89905. PMID: 20585256.

- de Vries M, Seppala LJ, Daams JG, van de Glind EMM, Masud T, van der Velde N; EUGMS Task and Finish Group on Fall-Risk-Increasing Drugs. Fall-Risk-Increasing Drugs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: I. Cardiovascular Drugs. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018 Apr;19(4):371.e1-371.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.013. Epub 2018 Feb 12. PMID: 29396189.

- Di Martino E, Provenzani A, Polidori P. Evidence-based application of explicit criteria to assess the appropriateness of geriatric prescriptions at admission and hospital stay. PLoS One. 2020 Aug 25;15(8):e0238064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238064. PMID: 32841285; PMCID: PMC7446960.

- Eckstrom E, Parker EM, Lambert GH, Winkler G, Dowler D, Casey CM. Implementing STEADI in Academic Primary Care to Address Older Adult Fall Risk. Innov Aging. 2017 Sep;1(2):igx028. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igx028. PMID: 29955671; PMCID: PMC6016394.

- Frankenthal D, Israeli A, Caraco Y, Lerman Y, Kalendaryev E, Zandman-Goddard G, Lerman Y. Long-Term Outcomes of Medication Intervention Using the Screening Tool of Older Persons Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions Screening Tool to Alert Doctors to Right Treatment Criteria. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017 Feb;65(2):e33-e38. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14570. Epub 2016 Dec 9. PMID: 27943247.

- Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L, O'Leary JR, Towle V, Van Ness PH. Health outcome prioritization as a tool for decision making among older persons with multiple chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Nov 14;171(20):1854-6. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.424. Epub 2011 Sep 26. PMID: 21949032; PMCID: PMC4036681.

- Hartikainen S, Lönnroos E, Louhivuori K. Medication as a risk factor for falls: critical systematic review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007 Oct;62(10):1172-81. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1172. PMID: 17921433.

- Hill-Taylor B, Walsh KA, Stewart S, Hayden J, Byrne S, Sketris IS. Effectiveness of the STOPP/START (Screening Tool of Older Persons' potentially inappropriate Prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert doctors to the Right Treatment) criteria: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016 Apr;41(2):158-69. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12372. Epub 2016 Mar 17. PMID: 26990017.

- Hopewell S, Adedire O, Copsey BJ, Boniface GJ, Sherrington C, Clemson L, Close JC, Lamb SE. Multifactorial and multiple component interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Jul 23;7(7):CD012221. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012221.pub2. PMID: 30035305; PMCID: PMC6513234.

- Ilhan, B., Erdo?an, T., Topinková, E., Bahat, G., & EuGMS Task and Finish Group on FRIDs (2023). Management of use of urinary antimuscarinics and alpha blockers for benign prostatic hyperplasia in older adults at risk of falls: a clinical review. European geriatric medicine, 14(4), 733-746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-023-00798-7

- Jamieson HA, Nishtala PS, Scrase R, Deely JM, Abey-Nesbit R, Hilmer SN, Abernethy DR, Berry SD, Mor V, Lacey CJ, Schluter PJ. Drug Burden Index and Its Association With Hip Fracture Among Older Adults: A National Population-Based Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019 Jun 18;74(7):1127-1133. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly176. PMID: 30084928.

- Kimura T, Ogura F, Yamamoto K, Uda A, Nishioka T, Kume M, Makimoto H, Yano I, Hirai M. Potentially inappropriate medications in elderly Japanese patients: effects of pharmacists' assessment and intervention based on Screening Tool of Older Persons' Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions criteria ver.2. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017 Apr;42(2):209-214. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12496. Epub 2016 Dec 31. PMID: 28039932.

- Korkatti-Puoskari, N., Tiihonen, M., Caballero-Mora, M. A., Topinkova, E., Szczerbińska, K., Hartikainen, S., & on the Behalf of the EuGMS Task & Finish group on FRIDs (2023). Therapeutic dilemma's: antipsychotics use for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, delirium and insomnia and risk of falling in older adults, a clinical review. European geriatric medicine, 14(4), 709-720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-023-00837-3

- Lavrador M, Cabral AC, Figueiredo IV, Veríssimo MT, Castel-Branco MM, Fernandez-Llimos F. Size of the associations between anticholinergic burden tool scores and adverse outcomes in older patients. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021 Feb;43(1):128-136. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01117-x. Epub 2020 Aug 29. PMID: 32860598.

- Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999a Jan;47(1):30-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01898.x. PMID: 9920227.

- Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: II. Cardiac and analgesic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999b Jan;47(1):40-50. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01899.x. PMID: 9920228.

- Lukazewski A, Mikula B, Servi A, Martin B. Evaluation of a web-based tool in screening for medication-related problems in community-dwelling older adults. Consult Pharm. 2012 Feb;27(2):106-13. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2012.106. PMID: 22330951.

- McMahon CG, Cahir CA, Kenny RA, Bennett K. Inappropriate prescribing in older fallers presenting to an Irish emergency department. Age Ageing. 2014 Jan;43(1):44-50. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft114. Epub 2013 Aug 8. PMID: 23927888.

- Montero-Odasso MM, Kamkar N, Pieruccini-Faria F, Osman A, Sarquis-Adamson Y, Close J, Hogan DB, Hunter SW, Kenny RA, Lipsitz LA, Lord SR, Madden KM, Petrovic M, Ryg J, Speechley M, Sultana M, Tan MP, van der Velde N, Verghese J, Masud T; Task Force on Global Guidelines for Falls in Older Adults. Evaluation of Clinical Practice Guidelines on Fall Prevention and Management for Older Adults: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Dec 1;4(12):e2138911. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.38911. PMID: 34910151; PMCID: PMC8674747.

- Montero-Odasso M, van der Velde N, Martin FC, Petrovic M, Tan MP, Ryg J, Aguilar-Navarro S, Alexander NB, Becker C, Blain H, Bourke R, Cameron ID, Camicioli R, Clemson L, Close J, Delbaere K, Duan L, Duque G, Dyer SM, Freiberger E, Ganz DA, Gómez F, Hausdorff JM, Hogan DB, Hunter SMW, Jauregui JR, Kamkar N, Kenny RA, Lamb SE, Latham NK, Lipsitz LA, Liu-Ambrose T, Logan P, Lord SR, Mallet L, Marsh D, Milisen K, Moctezuma-Gallegos R, Morris ME, Nieuwboer A, Perracini MR, Pieruccini-Faria F, Pighills A, Said C, Sejdic E, Sherrington C, Skelton DA, Dsouza S, Speechley M, Stark S, Todd C, Troen BR, van der Cammen T, Verghese J, Vlaeyen E, Watt JA, Masud T; Task Force on Global Guidelines for Falls in Older Adults. World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age Ageing. 2022 Sep 2;51(9):afac205. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afac205. PMID: 36178003; PMCID: PMC9523684.

- Nyborg G, Brekke M, Straand J, Gjelstad S, Romøren M. Potentially inappropriate medication use in nursing homes: an observational study using the NORGEP-NH criteria. BMC Geriatr. 2017 Sep 19;17(1):220. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0608-z. PMID: 28927372; PMCID: PMC5606129.

- Onatade R, Auyeung V, Scutt G, Fernando J. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in patients on admission and discharge from an older peoples' unit of an acute UK hospital. Drugs Aging. 2013 Sep;30(9):729-37. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0097-5. PMID: 23780641.

- Park H, Satoh H, Miki A, Urushihara H, Sawada Y. Medications associated with falls in older people: systematic review of publications from a recent 5-year period. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015 Dec;71(12):1429-40. doi: 10.1007/s00228-015-1955-3. Epub 2015 Sep 26. PMID: 26407688.

- Portlock, G. E., Smith, M. D., van Poelgeest, E. P., Welsh, T. J., & EuGMS Task and Finish Group on FRIDs(Fall-Risk-Increasing Drugs) (2023). Therapeutic dilemmas: cognitive enhancers and risk of falling in older adults-a clinical review. European geriatric medicine, 14(4), 721-732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-023-00821-x

- Prudent M, Dramé M, Jolly D, Trenque T, Parjoie R, Mahmoudi R, Lang PO, Somme D, Boyer F, Lanièce I, Gauvain JB, Blanchard F, Novella JL. Potentially inappropriate use of psychotropic medications in hospitalized elderly patients in France: cross-sectional analysis of the prospective, multicentre SAFEs cohort. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(11):933-46. doi: 10.2165/0002512-200825110-00004. PMID: 18947261.

- Romano S, Figueira D, Teixeira I, Perelman J. Deprescribing Interventions among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Economic Evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2022 Mar;40(3):269-295. doi: 10.1007/s40273-021-01120-8. Epub 2021 Dec 16. PMID: 34913143.

- Schuling J, Sytema R, Berendsen AJ. Aanpassen medicatie: voorkeur oudere patiënt telt mee [Adjusting medication: elderly patient's preference counts]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2013;157(47):A6491. Dutch. PMID: 24252406.

- Seppala LJ, Wermelink AMAT, de Vries M, Ploegmakers KJ, van de Glind EMM, Daams JG, van der Velde N; EUGMS task and Finish group on fall-risk-increasing drugs. Fall-Risk-Increasing Drugs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: II. Psychotropics. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018a Apr;19(4):371.e11-371.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.098. PMID: 29402652.