Interventies gericht op psychische doelen

Uitgangsvraag

Welk bewijs is er voor de effectiviteit van interventies gericht op psychische doelen bij patiënten met coronaire hartziekte die hartrevalidatie ondergaan?

Aanbeveling

Bied individuele behandeling aan wanneer het gaat om een ernstig verstoord emotioneel evenwicht (afhankelijk van onderliggend substraat) of psychische problematiek volgend op doormaken van een cardiaal incident.

Bied groepsbehandeling ((E)PEP-module) wanneer er sprake is van een verstoord emotioneel evenwicht (afhankelijk van onderliggend substraat) dan wel risicofactoren op psychologisch vlak.

Bied in een psychologische groepsinterventie ((E)PEP-module) cognitief gedragstherapeutische technieken en technieken vanuit de mindfulness aan. Bied aanvullend daarop een bewegingsprogramma aan.

Bied patiënten met een subklinisch niveau van angst- of depressieve symptomen dan wel een angst- of depressieve stoornis na een cardiaal incident een individuele interventie (cognitieve gedragstherapie, relaxatie, mindfulness) en een bewegingsprogramma.

Schakel bij moeilijk te doorbreken angst- en/of stemmingsklachten de huisarts of psychiater in ter beoordeling van inzet van een aanvullende medicamenteuze behandeling;

- TCA’s zijn gecontra-indiceerd als behandeling van depressieve stoornissen bij cardiaal belaste patiënten vanwege arrhythmische eigenschappen;

SSRI’s en mirtazapine zijn medicamenten van eerste keus ter behandeling van depressieve stoornissen bij cardiaal belaste patiënten.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Voor deze module is een literatuuranalyse gedaan naar de psychologische en klinische (cardiale) uitkomsten van een psychologische interventie bij coronaire hartpatiënten, vergeleken met standaard zorg. Er is één systematische review beschreven, waarbij studies met een minimale follow-up tijd van 6 maanden zijn geïncludeerd. De psychologische interventies omvatten voornamelijk relaxatietherapie, cognitieve gedragstherapie en emotionele support. Hierbij werd onder andere gefocust op het reduceren van stress, depressie en angst. Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat cardiovasculaire mortaliteit was de bewijskracht gemiddeld voor een positief effect van een psychologische interventie. Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten depressie, angst, stress en niet-fataal myocardinfarct was de bewijskracht laag. Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten boosheid, algehele mortaliteit en revascularisatie was de bewijskracht zeer laag. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat kwaliteit van leven is geen bewijskracht berekend, vanwege inconsistentie in het meten van uitkomstmaat. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten slaap en vermoeidheid zijn geen resultaten gevonden. De bewijskracht werd gelimiteerd door het risico op bias (ontbreken van informatie of het randomisatieproces) en een breed betrouwbaarheidsinterval van de effectschatter. Op basis van klinische praktijkervaring en secundaire wetenschappelijke analyses zou er rekening gehouden kunnen worden met verschillen tussen mannen en vrouwen, en verschillen die verband houden met etnische achtergrond.

Er zijn verscheidene studies gedaan die bewijs leveren voor het bestaan van verschillen tussen mannen en vrouwen wat betreft de effectiviteit van psychologische behandeling in het kader van hartrevalidatie. Zo laat een secundaire analyse van de ENRICHD-trial zien dat alleen behandelde witte mannen een verbetering laten zien op morbiditeit en mortaliteit, terwijl de depressieklachten bij iedereen verminderen (Schneiderman, 2004). Ook zijn er vrouwspecifieke kenmerken die een behandeling meer effectief maken in vrouwen. Deze hebben te maken met sociale aspecten van de behandeling, zoals de therapeut relatie, en samenstelling van de groep (vrouwen halen meer resultaat in groepen met alleen maar vrouwen) (Supervía, 2017). Een en ander wordt ook beschreven in de module Interventies gericht op diversiteit.

Kwalitatief onderzoek naar de ervaringen van patiënten met hartrevalidatie laat zien dat culturele aspecten zoals religieuze overwegingen, taalbarrière, gepercipieerde controle (beliefs) over eigen gezondheidsgedrag, en houding ten opzichte van stressreductie oefeningen individuele verschillen in de effectiviteit van hartrevalidatie bepalen (Carew Tofani 2023). Bewust zijn van deze culturele verschillen kan helpen om de psychologische behandeling binnen de hartrevalidatie effectiever te maken.

Patiënten met een lage sociaaleconomische positie (SEP) starten vaker niet met hartrevalidatie en vallen ook vaker uit (Svendsen 2022). Voor cognitieve gedragstherapie is het bekend dat de cognitieve oriëntatie (verbale vaardigheden en huiswerk opdrachten) moeilijkheden kan opleveren voor patiënten met een lage SEP, waardoor ze makkelijker uitvallen (Allart-van Dam & Hosman, 2003). Voor bepaalde groepen kan het voordelig zijn om depressieve klachten en stress met alleen sport of sport+psycho-educatie aan te pakken (van der Waerden, 2013).

In de intake zou in samenspraak met de patiënt (shared decision making) moeten worden nagegaan in hoeverre er sprake is van een emotionele disbalans en psychologische problematiek, en daarna wat er wel en niet aangegaan wordt in het kader van de hartrevalidatie. Een gestandaardiseerd diagnostisch protocol bepaalt op welk van de twee psychologische interventieniveaus de behandeling plaats zal vinden: het groepsprogramma (PEP) of individuele begeleiding. Zie hiervoor de module Screening psychische doelen. Anderstaligen en mensen met cognitieve stoornissen kunnen vaak niet mee in groepsverband. Daarom heeft het de voorkeur deze patiënten individueel te behandelen. Wat er binnenskamers gebeurt bij de individuele behandeling wordt afgestemd op behoeften en capaciteiten van de patiënt.

Om in het algemeen voor individuele behandeling in aanmerking te komen moet de patiënt een vermoedelijke depressie of angststoornis hebben, waarvoor het het meest gangbaar is om cognitieve gedragstherapie te geven. Voor deze patiënten kan bij succesvolle behandeling een risicoreductie op psychologisch en medisch vlak verwacht worden en eventueel een verbetering in de kwaliteit van leven. Zie ook de richtlijn Depressie en de richtlijn Angststoornissen.

Patiënten met een matig verstoord emotioneel evenwicht komen in aanmerking voor de PEP module. Deze groepstherapie richt zich op het aanpakken van risicofactoren, zoals stress en alledaagse irritaties en leefstijl, en voorziet in lotgenotencontact (sociale steun). De mix van psycho-educatie in combinatie met cognitief-gedragstherapeutische technieken leidt tot meer inzicht en bewustwording van de rol van deze factoren in hun cardiale gezondheid. Daardoor wordt een reductie bewerkstelligd in stress, en een herstel van emotionele balans.

Behandelingen en behandelthema’s ter aanvulling op de literatuursamenvatting

Mindfulness interventies

Mindfulness-gebaseerde interventies combineren elementen van de mindfulness-gebaseerde stressreductie training met cognitief-gedragstherapeutische elementen met als doel stress te verminderen en psychologisch en fysiek welzijn te bevorderen. Een recente meta-analyse (Zou, 2021) analyseerde de gepoolde effecten van negen trials in patiënten met coronair lijden. Mindfulness-gebaseerde interventies reduceerden significant depressieve klachten (7 studies, 370 deelnemers; SMD = -0.72 (95%CI: -1.23 tot -0.21) en stress (3 studies, 150 deelnemers; SMD = -0.67 (95%CI: -1.00 tot -0.34). Het effect op angst was niet significant (7 studies, 370 deelnemers; SMD =

-0.42 (95%CI: -1.17 tot 0.33). Heterogeniteit voor het effect op depressie- en angstreductie was hoog. Daarom werden subgroepanalyses gedaan. Hieruit bleek dat de soort mindfulness-gebaseerde therapie en het op baseline aanwezige niveau van emotionele disstress belangrijke effect moderatoren waren (Zou, 2021). Belangrijk om op te merken, deze effecten verdwenen als vergeleken werd met een actieve controlegroep, die bijvoorbeeld progressieve spierontspanning of een zelfhulp boekje kreeg. De effecten werden gemeten over een relatief korte follow-up periode (1 studie van de 9 had een 1-jaars follow-up, de rest tussen de 1-5 maanden). Naar de effecten op kwaliteit van leven en cardiometabole uitkomstmaten zal nader onderzoek gedaan moeten worden. Er waren te weinig studies om daar conclusies over te trekken. Over het algemeen zijn grotere en studies van hogere kwaliteit nodig om zekerheid over deze uitkomsten te vergroten.

Boosheid-/hostiliteitsreductie

Bekend is dat boosheid en hostiliteit een risicofactor vormen voor de toename van hartincidenten in een gezonde populatie (Chida, 2009). Bij mensen die reeds hartpatiënt zijn, resulteren boosheid en hostiliteit in een slechtere prognose. Met name mannen zijn meer gevoelig voor de schadelijke effecten van woede en hostiliteit op het hart (Chida 2009). Zowel de klinische psychologie als psychiatrie hebben zich ingespannen om een breed scala aan behandelingen te testen voor personen die periodes van boosheid en agressie kennen. Wanneer de mogelijkheden voor psychologische interventies worden nagegaan, lijkt cognitieve gedragstherapie een veel gebruikte interventievorm, net als positieve psychologie. Cognitieve- en gedragsmatige technieken omvatten veelal relaxatietraining, emotieregulatie, cognitieve herstructurering en oplossingsgerichte therapie om met de fysiologische arousal en negatieve emoties om te gaan (Blagys 2002; Suls 2013). Tevens is er bewijs voor positief effect van de inzet van psychofarmaca als selectieve serotonineheropnameremmers (SSRI’s). Met name omdat serotonine agressie moduleert en hostiliteit dus zou verminderen wanneer SSRI's ten minste twee maanden op dagelijkse basis worden geslikt (Kamarck 2009).

Psychofarmaca

Mentale stoornissen vormen een risico voor het ontwikkelen van een cardiovasculaire ziekte en vice versa (Correll, 2017; Hare, 2014; Kahl, 2022) Wanneer hartpatiënten vergeleken worden met de algemene populatie komen aanpassingsstoornissen, angststoornissen en depressie vaker voor (Celano, 2011; Rudisch, 2003). Bij ernstiger problematiek is psychofarmaca een vaak gebruikte behandelvorm waarbij SSRI’s en mirtazepine medicamenten van eerste keus zijn. TCA’s zijn gecontra-indiceerd als behandeling van depressieve stoornissen bij cardiaal belaste patiënten vanwege arrhythmische eigenschappen (Kahl, 2022).

Slaaphygiëne

Slaap speelt een belangrijke rol in het reguleren van onze mentale gezondheid. Verstoringen in de slaap of insomnia, zorgen voor een allostatische overbelasting waardoor de neuroplasticiteit van de hersenen alsook de neurologische paden voor stress-immuniteit worden aangetast (Palagini, 2022). Wanneer de mogelijkheden voor psychologische interventies worden nagegaan, is bekend dat cognitieve gedragstherapie de voorkeur kent boven farmacologische interventies (Hertenstein 2022). Cognitieve gedragstherapie is een multidimensionale behandeling waarbinnen psycho-educatie wordt gegeven aangaande slaap, gedragsinterventies worden gedaan als beperkingen in slaaptijden en stimuluscontrole, relaxatie en cognitieve therapie (Hertenstein, 2015; Morin, 2006). Cognitieve gedragstherapie kent gunstig effect in de behandeling van slapeloosheid, stresssystemen, neuro-inflammatie en neuroplasticiteit (Pallagini, 2022). Met gunstig effect voor stressniveaus en stresssystemen speelt cognitieve gedragstherapie in preventieve zin een belangrijke rol op het gebied van cardiale risicofactoren. Tevens draagt het op positieve wijze bij aan verdere behandeling gericht op psychische gevolgen na doormaken van een cardiaal incident omdat met behandeling de belastbaarheid wordt vergroot.

Trauma

PTSS veroorzaakt door cardiaal lijden komt bij een substantieel aantal hartpatiënten voor (Eisenberg 2022; Princip 2023). Relaxatietherapie en verschillende typen psychotherapie, zoals cognitieve gedragstherapie (imaginaire exposure) en EMDR zijn effectief gebleken om symptomen van PTSS te reduceren na het doormaken van een cardiaal incident (Haerizadeh, 2020; von Känel, 2018). Tevens is het gebruik van SSRI’s effectief gebleken (Princip, 2023). Belangrijk te vermelden is dat therapievormen die zich toespitsen op trauma de voorkeur kennen boven therapievormen die zich niet specifiek toespitsen op trauma in het reduceren van PTSS-symptomen (von Känel, 2022).

Psychologische interventies dragen niet alleen bij in psychologisch welzijn maar ook aan vermindering van zorgkosten. Een voorbeeld hiervan zijn hartpatiënten bekend met angstproblematiek. Deze patiëntengroep is geneigd om geruststelling te zoeken bij een HAP/SEH, (huis)arts of ander lid van het hartrevalidatieteam. Wanneer tijdige psychologische interventie kan worden ingezet worden onnodige zorgkosten door onnodige consultatie daarmee gedrukt. Wanneer specifiek gekeken wordt naar de interventievorm, individuele- dan wel groepsbehandeling, heeft de PEP-module voorkeur omdat meerdere patiënten door eenzelfde therapeut gezien kunnen worden op hetzelfde moment. De PEP-module wordt steeds vaker in een ‘blended’ vorm aangeboden, binnen de zogenaamde E-PEP. Patiënten kunnen modules in hun thuisomgeving doorlopen en maken daardoor minder gebruik van directe zorgmomenten. Daarentegen vraagt de E-PEP voorzieningen (zie module Op afstand begeleide gedragsverandering en bevordering emotioneel welbevinden (E-PEP-PSY met telesessies)) als een online omgeving waarbij gebruik gemaakt wordt van externe voorzieningen waaraan licentiekosten verbonden zijn.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het literatuuroverzicht laat zien dat cognitieve gedragstherapie bewezen nut heeft om medische uitkomsten (overleving en cardiale events) alsmede het functioneren van de hartpatiënt te verbeteren. Het literatuuroverzicht geeft ook aan dat thema’s als stressmanagement en het reduceren van angst en stemmingsklachten en woede/hostiliteit centraal zouden moeten staan in de aangeboden groepsinterventie (PEP module). Het advies is om hierbij te handelen volgens het sociaal-cognitieve model (Bandura, 2004). Dit model biedt een veelzijdige structuur waarin overtuigingen aangaande zelfeffectiviteit samengaan met doelen, verwachte uitkomsten en belemmerende en faciliterende factoren bij het reguleren van motivatie, gedrag en welzijn. In de dagelijkse praktijk wordt dit reeds toepast bij aanvang van een behandeltraject en gedurende het verloop daarvan. Bij aanvang worden de behoeften van de patiënt geïnventariseerd en naar aanleiding daarvan worden doelen opgesteld, rekening houdend met de sociale context en het uitganggsniveau van de patiënt. Gedurende het behandeltraject wordt gemonitord of de patiënt de doelen behaalt en eventuele bijsturing nodig is.

De PEP-module is een bestaand onderdeel van het hartrevalidatietraject en wordt vergoed vanuit de basisverzekering, waarmee het voor elke patiënt toegankelijk is, mits deze aan de behandelcriteria voldoet. Er zijn geen belemmerende factoren voor de continuering van het PEP-programma binnen de hartrevalidatie. Wel zouden zorgverleners zoals artsen, fysiotherapeuten en verpleegkundigen beter geïnformeerd kunnen worden over passende verwijsvragen voor de medische psychologie. Laatstgenoemde geldt overigens niet alleen voor het indiceren voor de PEP-module, maar ook voor individuele behandeling.

Rationale van de aanbevelingen: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De werkgroep is van mening dat gedurende de intakefase (vragenlijsten, intakegesprek medisch psycholoog) op basis van de verkregen (hetero-)anamnestische informatie een passend individueel aanbod of groepsaanbod moet worden geformuleerd. Afhankelijk van de problematiek wordt afgewogen welke interventie het best passend is en zal deze na overleg met patiënt worden ingezet (‘shared decision making’).

Er is veel onderzoek gedaan naar de effectiviteit van psychologische interventies bij hartpatiënten. In reviews wordt echter geen onderscheid gemaakt tussen individuele- en groepsinterventies. Vanuit klinisch oogpunt is de inzet van een groepsmodule geïndiceerd wanneer behandelthema’s zich richten op algemene risicofactoren en preventie. Wanneer het gaat om gevolgen van het doormaken van een hartincident is het in de praktijk gebleken dat een groepsaanbod onvoldoende specifiek is en op inhoudelijk niveau onvoldoende aansluit. Het maken van onderscheid in patiëntengroepen is wenselijk om een programma op maat te bieden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

The 2011 guideline for cardiac rehabilitation showed that psychological risk factors are associated with poor prognosis and mortality. In terms of screening and treatment, the 2011 guideline is mainly focusing on cardiac patients with emotional disturbances and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Cardiac patients with other psychological risk factors such as chronic stress, hostility, anger, Type D personality and post-traumatic stress disorder(PTSD)/trauma may be overlooked for psychological treatment. Moreover, as treatment for heart disease has been improving, with more advanced revascularization and pharmaceutical options, the attention should shift from survival to managing the chronic disease, and thus on improving or maintaining quality of life. The current search was meant to find interventions for the broad array of risk factors, as well examine quality of life and improvement in psychological functioning as main outcome measures, in addition to clinical outcomes.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Depression

|

Low GRADE |

Psychological interventions may reduce depression symptoms when compared with usual care in post-ACS patients and cardiac arrest patients.

Richards, 2018 |

Anxiety

|

Low GRADE |

Psychological interventions may reduce anxiety symptoms when compared with usual care in post-ACS patients and cardiac arrest patients.

Richards, 2018 |

Stress

|

Low GRADE |

Psychological interventions may reduce stress symptoms when compared with usual care in post-ACS patients and cardiac arrest patients.

Richards, 2018 |

Anger

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of psychological interventions on anger symptoms when compared with usual care in post-ACS patients and cardiac arrest patients.

Richards, 2018 |

Health-related quality of life

|

No GRADE |

No conclusion can be drawn on the effect of psychological interventions on health-related quality of life in post-ACS patients and cardiac arrest patients as the data were too different to perform a meta-analysis.

Richards, 2018 |

Total mortality

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of psychological interventions on total mortality when compared with usual care in post-ACS patients and cardiac arrest patients.

Richards, 2018 |

Cardiovascular mortality

|

Moderate GRADE |

Psychological interventions likely reduce the risk of cardiovascular mortality when compared with usual care in post-ACS patients and cardiac arrest patients.

Richards, 2018 |

Non-fatal myocardial infarction

|

Low GRADE |

Psychological interventions may result in little to no difference in risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction when compared with usual care in post-ACS patients and cardiac arrest patients.

Richards, 2018 |

Revascularization

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of psychological interventions on the risk of revascularization when compared with usual care in post-ACS patients and cardiac arrest patients.

Richards, 2018 |

Sleep, fatigue

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of psychological interventions on sleep and fatigue in post-ACS patients and cardiac arrest patients as the data were too different to perform a meta-analysis.

Richards, 2018 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of study

The systematic review and meta-analysis of Richards (2017) evaluated the effect of psychologic interventions compared with usual care for people with CHD after a cardiac event or procedure. Both psychologic interventions and usual care could be part of cardiac rehabilitation. A previous Cochrane review by Richards (2011) was updated with a search until April 2016 in the databases CENTRAL in the Cochrane Library, Medline, Embase, PsycINFO and Cinahl. Selection criteria included RCTs that compared the independent effect of psychological intervention versus a usual care comparator. The psychological intervention could be part of cardiac rehabilitation if this was also part of usual care. Inclusion criteria for patient population included adult patients with CHD (with or without clinical psychopathology) who experienced a myocardial infarction (MI), revascularization procedure (CABG/PCI), angina or an angiographically defined CHD. Studies with ≥50% patients with other cardiac conditions (e.g. heart failure, atrial fibrillation, ICD implant) or with a follow-up period of <6 months were excluded.

A total of 35 RCTs were included, with a total of 10.703 patients of which 66% were post-MI and 25% underwent a revascularization procedure (CABG/PCI). Interventions included relaxation techniques (number of studies: n = 20), self-awareness and self-monitoring (n = 20), emotional support and client-led discussion (n = 15) and cognitive challenge/restructuring techniques (n = 15). Details can be found in the table with study characteristics in the study article by Richards (2017). Length of follow-up ranged from six months to 10.7 years. The proportion of males in the total study population was 77% and mean age ranged between 53 to 67 years. Relevant study outcomes include total mortality, cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, revascularization procedures, depression, anxiety, stress, and anger. Study limitations include lack of information on randomization procedure and allocation concealment. Besides, about 25% of included studies had incomplete data outcome reporting.

Results

Depression

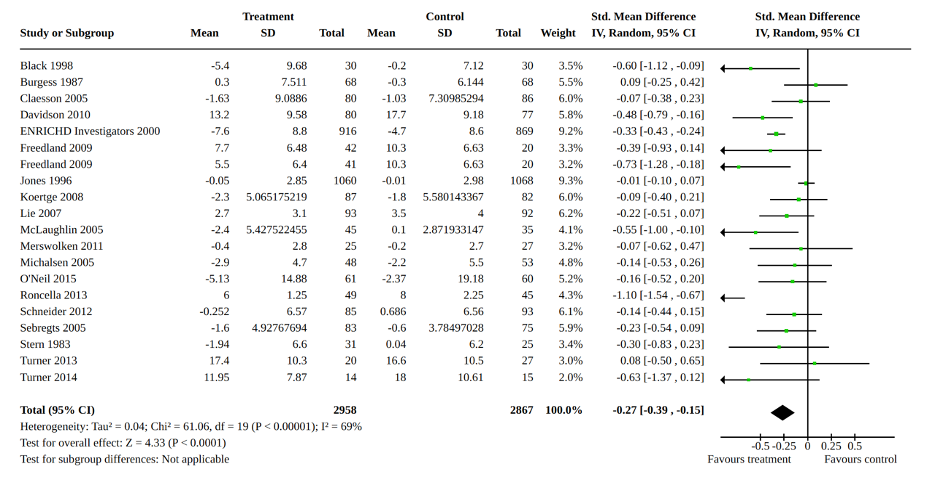

Nineteen RCTs reported on depression for a total of 5825 patients. Results are shown in Figure 2. The standardized mean difference (SMD, 95%CI) for the effect of psychological interventions on depression in CHD-patients is -0.27 (-0.39 to -0.15), indicating a small benefit for psychological interventions compared to usual care.

Figure 2 Effect of psychological interventions on depression compared to usual care in CHD-patients at minimal 6 months follow-up (Richards, 2017)

Anxiety

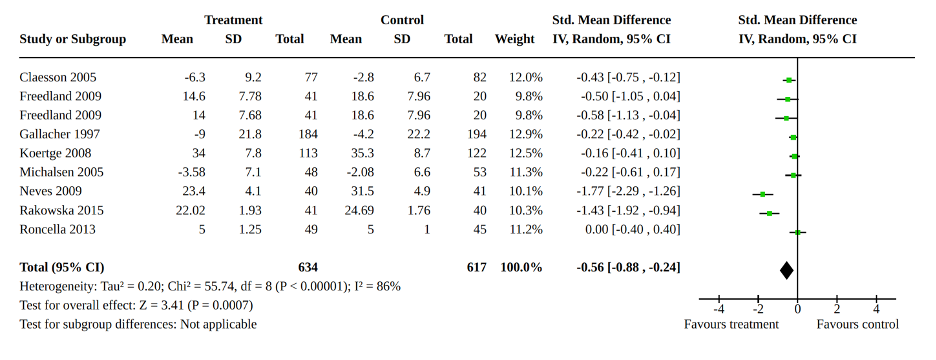

Twelve RCTs reported on anxiety for a total of 3161 patients. Results are shown in Figure 3. The SMD for the effect of psychological interventions on anxiety in CHD-patients is -0.24 (95%CI -0.38 to -0.09), indicating a small benefit for psychological interventions compared to usual care.

Figure 3 Effect of psychological interventions on depression compared to usual care in CHD-patients at minimal 6 months follow-up (Richards, 2017)

Stress

Eight RCTs reported on stress for a total of 1251 patients. Results are shown in Figure 4. The SMD (95%CI) for the effect of psychological interventions on stress in CHD patients is -0.56 (-0.88 to -0.24), indicating a moderate benefit for psychological interventions compared to usual care.

Figure 4 Effect of psychological interventions on stress compared to usual care in CHD-patients at minimal 6 months follow-up (Richards, 2017)

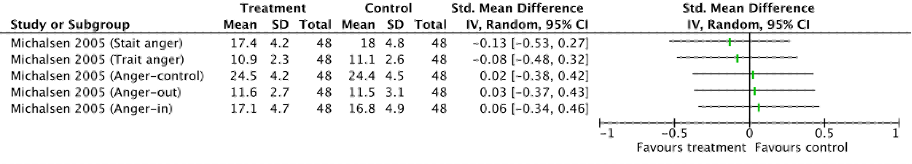

Anger

One study reported on how a lifestyle and stress management intervention in CAD patients influenced levels of anger (Michalsen, 2005), reported by the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI), as state anger, trait anger, anger-in, anger-out and anger-control. Results for the individual subscales (not pooled) are shown in Figure 5. For all subscales, the SMD is within the range -0.2 to 0.2, indicating no benefit for either psychological interventions or usual care in CHD patients.

Figure 5 Effect of psychological interventions on anger compared to usual care in CHD-patients at minimal 6 months follow-up (Michalsen, 2005; Richards, 2017)

Health-related quality of life

Ten studies reported on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (Appels 2005; Claesson 2005; ENRICHD Investigators 2000; Freedland 2009; Lie 2007; Mayou 2002; Michalsen 2005; O’Neil 2015; Rakowska 2015; Roncella 2013). However, it was not possible to pool the results, due to difference in measures and subscales used to assess HRQoL. Six studies found no differences in HRQoL for psychological interventions, compared to usual care (Appels 2005; Claesson 2005; Lie 2007; Mayou 2002; Michalsen 2005; O’Neil 2015; Rakowska 2015; Roncella 2013. Four studies found positive results for one of multiple (sub)scales for HRQoL. Compared to the usual care group, in the ENRICHED investigators study (2000), positive results were found for the Ladder of Life score, Life Satisfaction Scale and the mental component score of the SF-12 for the intervention group. Likewise, in both the studies by Rakowska (2015) and Freedland (2009), positive results were found regarding the physical and mental score of the SF-36. In the study by Roncella (2013), positive results were found regarding only the physical score of the MacNew Questionnaire.

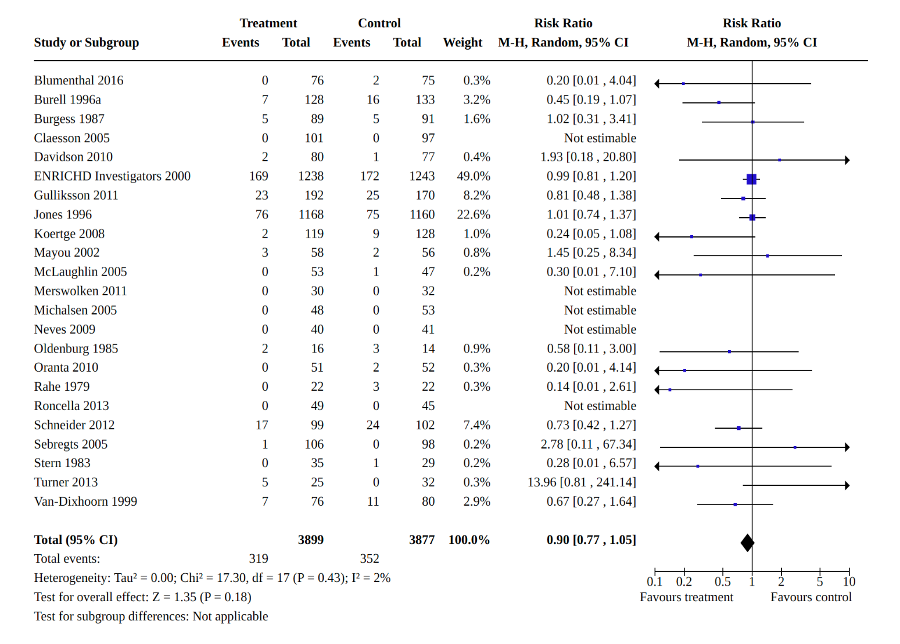

Total mortality

Twenty-three RCTs reported on total mortality for a total of 7776 patients. Results are shown in Figure 6. The risk ratio (RR, 95%CI) for the effect of any psychological intervention on total mortality in CHD-patients is 0.90 (0.77 to 1.05), indicating a reduced risk of total mortality with a psychological intervention compared to usual care in patients with CHD. The corresponding absolute risk difference was -1.14% (95%CI -2.43% to 0.15%). This absolute risk difference was a clinically relevant effect as it is more than -0.1% at one year follow-up.

Figure 6 Effect of psychological interventions on total mortality compared to usual care in CHD-patients at minimal 6 months follow-up (Richards, 2017)

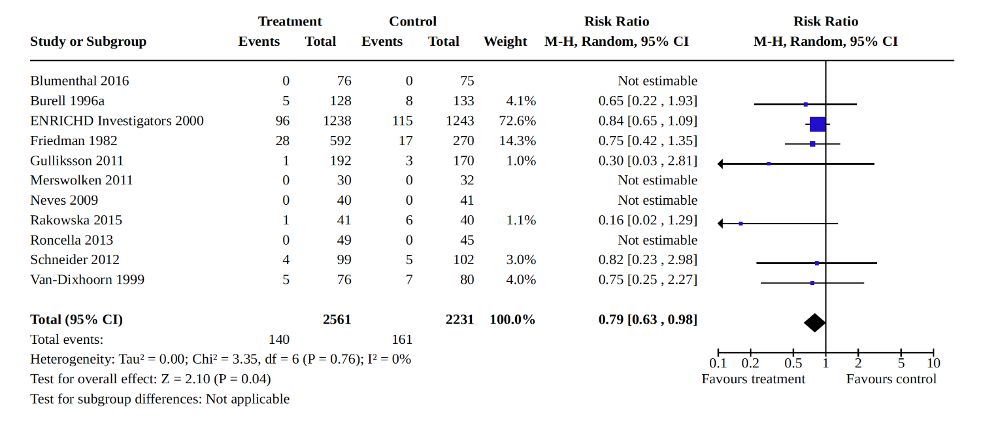

Cardiovascular mortality

Eleven RCTs reported on cardiovascular mortality for a total of 4792 patients. Results are shown in Figure 7. The RR (95%CI) for the effect of any psychological intervention on cardiovascular mortality in CHD-patients is 0.79 (0.63 to 0.98), indicating a reduced risk of cardiovascular mortality with a psychological intervention compared to usual care in patients with CHD. The corresponding absolute risk difference was -1.57% (95%CI -2.88% to -0.27%). This absolute risk difference was a clinically relevant effect as it is more than -0.5% at one year follow-up.

Figure 7 Effect of psychological interventions on cardiovascular mortality compared to usual care in CHD-patients at minimal 6 months follow-up (Richards, 2017)

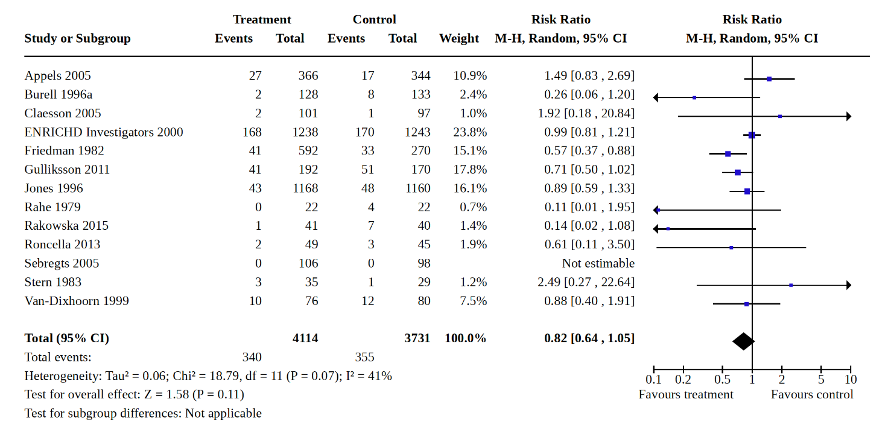

Non-fatal MI

Thirteen RCTs reported on non-fatal MI for a total of 7845 patients. Results are shown in Figure 8. The RR (95%CI) for the effect of any psychological intervention on non-fatal MI in CHD-patients is 0.82 (0.64 to 1.05), indicating a reduced risk of non-fatal MI with a psychological intervention compared to usual care in patients with CHD. The corresponding absolute risk difference was -1.83% (95%CI -4.05% to 0.39%). This absolute risk difference is a clinically relevant effect as it is more than -0.5% at one year follow-up.

Figure 8. Effect of psychological interventions on cardiovascular mortality compared to usual care in CHD-patients at minimal 6 months follow-up (Richards, 2017)

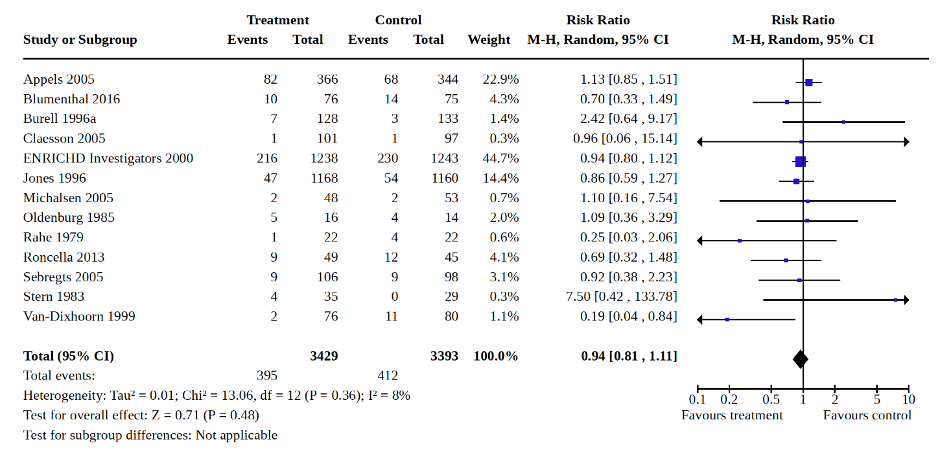

Revascularization (CABG + PCI)

Thirteen RCTs reported on revascularization for a total of 6822 patients. Results are shown in Figure 9. The RR (95%CI) for the effect of any psychological intervention on revascularization in CHD-patients is 0.94 (0.81 to 0.98), indicating a reduced risk of revascularization with a psychological intervention compared to usual care in patients with CHD. The corresponding absolute risk difference was -0.40% (95%CI -1.56% to 0.76%). This absolute risk difference was a clinically non-relevant effect as it is less than -0.5% at one year follow-up.

Figure 9. Effect of psychological interventions on cardiovascular mortality compared to usual care in CHD-patients at minimal 6 months follow-up (Richards, 2017)

Sleep, fatigue

No results were found for the outcomes sleep and fatigue.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence came from RCTs and therefore started as high.

Depression: The level of evidence was downgraded by two level to low, due to risk of bias (no blinding for participants and absence of information on randomization process in most studies, -1 level) and imprecision (confidence interval of the effect estimate crosses the boundary for no effect, -1 level).

Anxiety: The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels to low, due to risk of bias (no blinding for participants and absence of information on randomization process in most studies, -1 level) and imprecision (confidence interval of the effect estimate crosses the boundary for no effect, -1 level).

Stress: The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels to very low, due to risk of bias (no blinding for participants and absence of information on randomization process in most studies, -1 level) and imprecision (confidence interval of the effect estimate crosses the boundaries for large and small effect, -2 levels).

Anger: The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels to low GRADE, due to imprecision (optimal information size not reached, -2 levels). Although a per-protocol analysis was used by Michalsen (2005), no downgrading was performed for risk of bias as loss-to-follow-up was zero.

Health-related quality of life: The level of evidence could not be assessed, as the data were too different to perform a meta-analysis. Therefore, no further GRADE assessment was performed.

Total mortality: The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels to very low GRADE, due to risk of bias and imprecision (confidence interval of the effect estimate crosses the boundaries for both no effect and detrimental effect, -2 levels). Seven trials had potential high risk of bias. A sensitivity analysis excluding these trials, did change the pooled estimate ((RR 0.94, 95%CI 0.80 to 1.11), -1 level for risk of bias).

Cardiovascular mortality: The level of evidence was downgraded by one level to moderate GRADE, due to imprecision (confidence interval of the effect estimate crosses the boundary for no effect, -1 level). Two trials had potential high risk of bias. A sensitivity analysis excluding these trials, did not change the pooled estimate (RR 0.80, 95%CI 0.63 to 1.00). Therefore, Therefore, the level of evidence was not downgraded for risk of bias.

Non-fatal myocardial infarction: The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels to low GRADE, due to inconsistency (heterogeneity between effect estimates in studies, including larger study of Appels (2005)) and imprecision (confidence interval of the effect estimate crosses the boundaries for no effect, -1 level). Four trials had potential high risk of bias. A sensitivity analysis excluding these trials, did change the pooled estimate in favor of the intervention (RR 0.75, 95%CI 0.57 to 0.99). Therefore, the level of evidence was not downgraded for risk of bias.

Revascularization: The level of evidence was downgraded by one level to very low GRADE, due to inconsistency (heterogeneity between effect estimates in studies, including larger study of Appels (2005)) and imprecision (confidence interval of the effect estimate crosses the boundaries for both no effect and detrimental effect, -2 levels). Five trials had potential high risk of bias. A sensitivity analysis excluding these trials, did not change the pooled estimate (RR 0.89, 95%CI 0.77 to 1.03). Therefore, the level of evidence was not downgraded for risk of bias.

Sleep, fatigue: No results were found. Therefore, the level of evidence was not assessed.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What are the effects of psychological interventions on psychological and clinical outcomes in CAD patients?

Table 1 PICO

|

Patients |

Patients with coronary artery disease |

|

Intervention |

Psychoeducation, stress management; anger management; relaxation therapy; cognitive behavioral therapy |

|

Control |

Usual care |

|

Outcomes |

Psychological outcomes (depression, anxiety, anger, stress, sleep, fatigue, health related quality of life), clinical outcomes (cardiac events (mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), PCI, CABG)) |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered change in psychological outcomes (excluding fatigue), MACE and (cardiovascular) mortality as critical outcome measures for decision making; and quality of life, fatigue and sleep as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

Cardiovascular mortality, MI, PCI, CABG: The working group defined absolute risk reduction of > 5% over ten years as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference, which corresponds with a reduction of > 0.5% per year.

Total mortality: The working group defined absolute risk reduction of > 1% over ten years as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference, which corresponds with a reduction of > 0.1% per year.

Depression, anxiety, anger, stress, sleep, fatigue, HRQoL: The working group defined standardized mean differences of 0.2 to 0.5 as small, 0.5 to 0.8 as medium and > 0.8 as large effect.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 17 July 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 912 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria systematic reviews or RCTs based on the PICO. Due to the large number of RCTs, reviews were selected. After reading the full text, 26 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and one study was included (Richards 2017). This review performed a search more than two years ago. Our search found no RCTs after search date of these reviews. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables of the included systematic reviews.

Results

One study was included in the analysis of literature, due to the restriction that an EMBASE search had to be done. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables of the included systematic reviews.

Referenties

- Allart-van Dam E, Hosman CMH, Hoogduin CAL, Schaap CPDR. The Coping with Depression course: Short-term outcomes and mediating effects of a randomized controlled trial in the treatment of subclinical depression. Behavior Therapy. 2003;34(3):381-396. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80007-2

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004 Apr;31(2):143-64. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. PMID: 15090118.

- Blagys MD, Hilsenroth MJ. Distinctive activities of cognitive-behavioral therapy. A review of the comparative psychotherapy process literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002 Jun;22(5):671-706. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00117-9. PMID: 12113201.

- Celano CM, Huffman JC. Depression and cardiac disease: a review. Cardiol Rev. 2011 May-Jun;19(3):130-42. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e31820e8106. PMID: 21464641.

- Chida Y, Steptoe A. The association of anger and hostility with future coronary heart disease: a meta-analytic review of prospective evidence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Mar 17;53(11):936-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.044. PMID: 19281923.

- Correll CU, Solmi M, Veronese N, Bortolato B, Rosson S, Santonastaso P, Thapa-Chhetri N, Fornaro M, Gallicchio D, Collantoni E, Pigato G, Favaro A, Monaco F, Kohler C, Vancampfort D, Ward PB, Gaughran F, Carvalho AF, Stubbs B. Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: a large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry. 2017 Jun;16(2):163-180. doi: 10.1002/wps.20420. Erratum in: World Psychiatry. 2018 Feb;17 (1):120. PMID: 28498599; PMCID: PMC5428179.

- Eisenberg R, Fait K, Dekel R, Levi N, Hod H, Matezki S, Vilchinsky N. Cardiac-disease-induced posttraumatic stress symptoms (CDI-PTSS) among cardiac patients' partners: A longitudinal study. Health Psychol. 2022 Oct;41(10):674-682. doi: 10.1037/hea0001175. Epub 2022 Apr 7. PMID: 35389689.

- Haerizadeh M, Sumner JA, Birk JL, Gonzalez C, Heyman-Kantor R, Falzon L, Gershengoren L, Shapiro P, Kronish IM. Interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms induced by medical events: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2020 Feb;129:109908. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109908. Epub 2019 Dec 19. PMID: 31884302; PMCID: PMC7580195.

- Hare DL, Toukhsati SR, Johansson P, Jaarsma T. Depression and cardiovascular disease: a clinical review. Eur Heart J. 2014 Jun 1;35(21):1365-72. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht462. Epub 2013 Nov 25. PMID: 24282187.

- Hertenstein, E., Spiegelhalder K., Johann, A., Riemann, D.D.. Prävention und Psychotherapie der Insomnie. July 2015. 1st ed.Kohlhammer Verlag Stuttgart

- Hertenstein E, Trinca E, Wunderlin M, Schneider CL, Züst MA, Fehér KD, Su T, Straten AV, Berger T, Baglioni C, Johann A, Spiegelhalder K, Riemann D, Feige B, Nissen C. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in patients with mental disorders and comorbid insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2022 Apr;62:101597. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101597. Epub 2022 Feb 9. PMID: 35240417.

- Kahl KG, Stapel B, Correll CU. Psychological and Psychopharmacological Interventions in Psychocardiology. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Mar 16;13:831359. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.831359. PMID: 35370809; PMCID: PMC8966219.

- Kamarck TW, Haskett RF, Muldoon M, Flory JD, Anderson B, Bies R, Pollock B, Manuck SB. Citalopram intervention for hostility: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009 Feb;77(1):174-88. doi: 10.1037/a0014394. PMID: 19170463; PMCID: PMC2745900.

- Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, Edinger JD, Espie CA, Lichstein KL. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia:update of the recent evidence (1998-2004). Sleep. 2006 Nov;29(11):1398-414. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.11.1398. PMID: 17162986.

- Palagini L, Hertenstein E, Riemann D, Nissen C. Sleep, insomnia and mental health. J Sleep Res. 2022 Aug;31(4):e13628. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13628. Epub 2022 May 4. PMID: 35506356.

- Princip M, Ledermann K, von Känel R. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder as a Consequence of Acute Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2023 Jun;25(6):455-465. doi: 10.1007/s11886-023-01870-1. Epub 2023 May 2. PMID: 37129760; PMCID: PMC10188382.

- Richards SH, Anderson L, Jenkinson CE, Whalley B, Rees K, Davies P, Bennett P, Liu Z, West R, Thompson DR, Taylor RS. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Apr 28;4(4):CD002902. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002902.pub4. PMID: 28452408; PMCID: PMC6478177.

- Rudisch B, Nemeroff CB. Epidemiology of comorbid coronary artery disease and depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003 Aug 1;54(3):227-40. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00587-0. PMID: 12893099.

- Schneiderman N, Saab PG, Catellier DJ, Powell LH, DeBusk RF, Williams RB, Carney RM, Raczynski JM, Cowan MJ, Berkman LF, Kaufmann PG; ENRICHD Investigators. Psychosocial treatment within sex by ethnicity subgroups in the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease clinical trial. Psychosom Med. 2004 Jul-Aug;66(4):475-83. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000133217.96180.e8. PMID: 15272091.

- Suls J. Anger and the heart: perspectives on cardiac risk, mechanisms and interventions. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013 May-Jun;55(6):538-47. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.03.002. Epub 2013 Apr 6. PMID: 23621963.

- Supervía M, Medina-Inojosa JR, Yeung C, Lopez-Jimenez F, Squires RW, Pérez-Terzic CM, Brewer LC, Leth SE, Thomas RJ. Cardiac Rehabilitation for Women: A Systematic Review of Barriers and Solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017 Mar 13:S0025-6196(17)30026-5. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.01.002. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 28365100; PMCID: PMC5597478.

- Svendsen ML, Gadager BB, Stapelfeldt CM, Ravn MB, Palner SM, Maribo T. To what extend is socioeconomic status associated with not taking up and dropout from cardiac rehabilitation: a population-based follow-up study. BMJ Open. 2022 Jun 21;12(6):e060924. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-060924. Erratum in: BMJ Open. 2022 Jul 5;12(7):e060924corr1. PMID: 35728905; PMCID: PMC9214391.

- van der Waerden JE, Hoefnagels C, Hosman CM, Souren PM, Jansen MW. A randomized controlled trial of combined exercise and psycho-education for low-SES women: short- and long-term outcomes in the reduction of stress and depressive symptoms. Soc Sci Med. 2013 Aug;91:84-93. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.015. Epub 2013 May 28. PMID: 23849242.

- von Känel R, Meister-Langraf RE, Barth J, Znoj H, Schmid JP, Schnyder U, Princip M. Early Trauma-Focused Counseling for the Prevention of Acute Coronary Syndrome-Induced Posttraumatic Stress: Social and Health Care Resources Matter. J Clin Med. 2022 Apr 2;11(7):1993. doi: 10.3390/jcm11071993. PMID: 35407601; PMCID: PMC8999513.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic reviews

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Richards, 2017

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to April, 2016

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: See Richards, 2017 for details. All studies except one were performed in Western countries.

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Twelve studies did not report funding sources; seven received government research grants; six from charities; six rom a mix of charities and government funding; two a mix of private companies, government and charities; one university funded. |

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

35 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: See Richards, 2017 for details.

|

A psychological intervention.

Common aims of treatments included:

Common components of psychological treatments included:

|

Common form of comparator was either 'usual medical care' or a 'cardiac rehabilitation programme in addition to usual medical care'. |

Endpoint of follow-up: See Richards, 2017 for details. Range 6 months to 10 years.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? See Richards, 2017 for details.

|

Depression 19 RCTs included. Pooled estimate: SMD (95%CI)-0.27 (-0.39 to -0.15)

Anxiety 12 RCTs included. Pooled estimate: SMD (95%CI) -0.24 (-0.38 to -0.09)

Stress 8 RCTs included. Pooled estimate: SMD(95%CI) -0.56 (-0.88 to -0.24)

Anger 1 RCT included (Michalsen 2005). Subscales from STAXI reported. SMD (95%CI): State-anger -0.13 (-0.53 to 0.27) Trait-anger -0.08 (-0.48 to 0.32) Anger-control 0.02 (-0.38 to 0.42) Anger-out 0.03 (-0.37 to 0.43) Anger-in 0.06 (-0.34 to 0.46)

HRQoL Ten RCTs included. Direct comparisons between studies were difficult due to the different types of measures used to assess HRQoL.

Total mortality 23 RCTs included. Pooled estimate: RR (95%CI) 0.90 (0.77 to 1.05), I² = 2%

Cardiovascular mortality 11 RCTs included. Pooled estimate: RR (95%CI) 0.79 (0.63 to 0.98), I² = 0%

Non-fatal myocardial infarction 13 RCTs included. Pooled estimate: RR (95%CI) 0.82 (0.64 to 1.05), I² = 41%

Revascularization 13 RCTs included. Pooled estimate: RR (95%CI) 0.94 (0.81 to 1.11), I² = 8%

|

Risk of bias (high, some concerns or low): Cochrane Risk of Bias tool See Richards, 2017 for details.

|

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Albus C, Herrmann-Lingen C, Jensen K, Hackbusch M, Münch N, Kuncewicz C, Grilli M, Schwaab B, Rauch B; German Society of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (DGPR). Additional effects of psychological interventions on subjective and objective outcomes compared with exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation alone in patients with cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019 Jul;26(10):1035-1049. doi: 10.1177/2047487319832393. Epub 2019 Mar 11. PMID: 30857429; PMCID: PMC6604240. |

Incorrect control group (exercise-based intervention)

|

|

Ryan EM, Creaven AM, Ní Néill E, O'Súilleabháin PS. Anxiety following myocardial infarction: A systematic review of psychological interventions. Health Psychol. 2022 Sep;41(9):599-610. doi: 10.1037/hea0001216. PMID: 36006699. |

Specific study population, incorrect search methods

|

|

Dickens C, Cherrington A, Adeyemi I, Roughley K, Bower P, Garrett C, Bundy C, Coventry P. Characteristics of psychological interventions that improve depression in people with coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-regression. Psychosom Med. 2013 Feb;75(2):211-21. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31827ac009. Epub 2013 Jan 16. PMID: 23324874. |

More recent review available

|

|

Dekker RL. Cognitive therapy for depression in patients with heart failure: a critical review. Heart Fail Clin. 2011 Jan;7(1):127-41. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2010.10.001. PMID: 21109215; PMCID: PMC3018846. |

More recent review available

|

|

Ramamurthy G, Trejo E, Faraone SV. Depression treatment in patients with coronary artery disease: a systematic review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(5):PCC.13r01509. doi: 10.4088/PCC.13r01509. Epub 2013 Oct 24. PMID: 24511449; PMCID: PMC3907329. |

More recent review available

|

|

Williams JW Jr, Nieuwsma JA, Namdari N, Washam JB, Raitz G, Blumenthal JA, Jiang W, Yapa R, McBroom AJ, Lallinger K, Schmidt R, Kosinski AS, Sanders GD. Diagnostic Accuracy of Screening and Treatment of Post–Acute Coronary Syndrome Depression: A Systematic Review [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2017 Nov. Report No.: 18-EHC001-EF. PMID: 29697225. |

Mostly studies on screening. Only two relevant studies included. |

|

Thombs BD, Roseman M, Coyne JC, de Jonge P, Delisle VC, Arthurs E, Levis B, Ziegelstein RC. Does evidence support the American Heart Association's recommendation to screen patients for depression in cardiovascular care? An updated systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e52654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052654. Epub 2013 Jan 7. PMID: 23308116; PMCID: PMC3538724. |

More recent review available

|

|

Shi Y, Lan J. Effect of stress management training in cardiac rehabilitation among coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2021 Dec 22;22(4):1491-1501. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm2204153. PMID: 34957788. |

Review on stress management, although studies without cognitive behavioural therapy were excluded.

|

|

Reavell J, Hopkinson M, Clarkesmith D, Lane DA. Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression and Anxiety in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychosom Med. 2018 Oct;80(8):742-753. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000626. PMID: 30281027. |

Strict inclusion criteria on intervention (purely cognitive behavioural therapy, no co-intervention).

|

|

Li YN, Buys N, Ferguson S, Li ZJ, Sun J. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy-based interventions on health outcomes in patients with coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry. 2021 Nov 19;11(11):1147-1166. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v11.i11.1147. PMID: 34888180; PMCID: PMC8613762. |

Incorrect search methods (not fully retracable)

|

|

Nuraeni A, Suryani S, Trisyani Y, Sofiatin Y. Efficacy of Cognitive Behavior Therapy in Reducing Depression among Patients with Coronary Heart Disease: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of RCTs. Healthcare (Basel). 2023 Mar 24;11(7):943. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11070943. PMID: 37046869; PMCID: PMC10094182. |

Although according to PICO, too specific on depression.

|

|

Magán I, Casado L, Jurado-Barba R, Barnum H, Redondo MM, Hernandez AV, Bueno H. Efficacy of psychological interventions on psychological outcomes in coronary artery disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2021 Aug;51(11):1846-1860. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720000598. Epub 2020 Apr 6. PMID: 32249725. |

Incorrect search strategy

|

|

Magán I, Jurado-Barba R, Casado L, Barnum H, Jeon A, Hernandez AV, Bueno H. Efficacy of psychological interventions on clinical outcomes of coronary artery disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2022 Feb;153:110710. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110710. Epub 2021 Dec 25. PMID: 34999380. |

Incorrect search strategy

|

|

Gathright EC, Salmoirago-Blotcher E, DeCosta J, Balletto BL, Donahue ML, Feulner MM, Cruess DG, Wing RR, Carey MP, Scott-Sheldon LAJ. The impact of transcendental meditation on depressive symptoms and blood pressure in adults with cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2019 Oct;46:172-179. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.08.009. Epub 2019 Aug 16. PMID: 31519275; PMCID: PMC7046170. |

Too specific intervention, many studies included that only studied in patients with hypertension

|

|

Pedersen SS, Skovbakke SJ, Skov O, Carlbring P, Burg MM, Habibović M, Ahm R. Internet-Delivered, Therapist-Assisted Treatment for Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence-Base and Challenges. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2023 Jun;25(6):443-453. doi: 10.1007/s11886-023-01867-w. Epub 2023 Apr 29. PMID: 37119450. |

Narrative review

|

|

Akosile W, Tiyatiye B, Colquhoun D, Young R. Management of depression in patients with coronary artery disease: A systematic review. Asian J Psychiatr. 2023 May;83:103534. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103534. Epub 2023 Feb 28. PMID: 36871435. |

Review with strict inclusion criteria, mostly studies on pharmacological treatments. Many studies on cognitive behavioural therapy not included. |

|

Yu H, Ma Y, Lei R, Xu D. A meta-analysis of clinical efficacy and quality of life of cognitive-behavioral therapy in acute coronary syndrome patients with anxiety and depression. Ann Palliat Med. 2020 Jul;9(4):1886-1895. doi: 10.21037/apm-20-974. Epub 2020 Jun 10. PMID: 32576008. |

According to PICO, but specific intervention. |

|

Younge JO, Gotink RA, Baena CP, Roos-Hesselink JW, Hunink MG. Mind-body practices for patients with cardiac disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015 Nov;22(11):1385-98. doi: 10.1177/2047487314549927. Epub 2014 Sep 16. PMID: 25227551. |

Too specific intervention, not according to PICO

|

|

Marino F, Failla C, Carrozza C, Ciminata M, Chilà P, Minutoli R, Genovese S, Puglisi A, Arnao AA, Tartarisco G, Corpina F, Gangemi S, Ruta L, Cerasa A, Vagni D, Pioggia G. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Physical and Psychological Wellbeing in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2021 May 29;11(6):727. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11060727. PMID: 34072605; PMCID: PMC8227381. |

Incorrect search, vague exclusion criteria. |

|

Marino F, Failla C, Carrozza C, Ciminata M, Chilà P, Minutoli R, Genovese S, Puglisi A, Arnao AA, Tartarisco G, Corpina F, Gangemi S, Ruta L, Cerasa A, Vagni D, Pioggia G. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Physical and Psychological Wellbeing in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2021 May 29;11(6):727. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11060727. PMID: 34072605; PMCID: PMC8227381. |

Older review, intervention is not according to PICO

|

|

Tully PJ, Ang SY, Lee EJ, Bendig E, Bauereiß N, Bengel J, Baumeister H. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for depression in patients with coronary artery disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Dec 15;12(12):CD008012. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008012.pub4. PMID: 34910821; PMCID: PMC8673695. |

Incorrect search strategy

|

|

Cojocariu SA, Maștaleru A, Sascău RA, Stătescu C, Mitu F, Cojocaru E, Trandafir LM, Leon-Constantin MM. Relationships between Psychoeducational Rehabilitation and Health Outcomes-A Systematic Review Focused on Acute Coronary Syndrome. J Pers Med. 2021 May 21;11(6):440. doi: 10.3390/jpm11060440. PMID: 34063747; PMCID: PMC8223782. |

Incorrect search strategy

|

|

van Dixhoorn J, White A. Relaxation therapy for rehabilitation and prevention in ischaemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005 Jun;12(3):193-202. doi: 10.1097/00149831-200506000-00002. PMID: 15942415. |

Old review with no full data on relevant outcomes

|

|

Zou H, Cao X, Chair SY. A systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness-based interventions for patients with coronary heart disease. J Adv Nurs. 2021 May;77(5):2197-2213. doi: 10.1111/jan.14738. Epub 2021 Jan 12. PMID: 33433036. |

Study on mind-fullness therapy, incorrect search methods (not fully retracable)

|

|

Zhang Y, Liang Y, Huang H, Xu Y. Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological intervention on patients with coronary heart disease. Ann Palliat Med. 2021 Aug;10(8):8848-8857. doi: 10.21037/apm-21-1623. Epub 2021 Jul 27. PMID: 34328010. |

Study on mind-fullness therapy, incorrect search methods (not fully retracable)

|

|

Farquhar JM, Stonerock GL, Blumenthal JA. Treatment of Anxiety in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease: A Systematic Review. Psychosomatics. 2018 Jul-Aug;59(4):318-332. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2018.03.008. Epub 2018 Mar 27. PMID: 29735242; PMCID: PMC6015539. |

Large review with only short conclusion on study (no detailed results)

|

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 02-10-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 17-09-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met hart- en vaatziekten.

Werkgroep

- Prof. dr. A.W.J. (Arnoud) van ‘t Hof, cardioloog, werkzaam in het Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum te Maastricht en Zuyderland MC te Heerlen [NVVC] (voorzitter)

- Dr. T. (Tom) Vromen, cardioloog, werkzaam in het Máxima Medisch Centrum te Eindhoven [NVVC]

- Dr. M. (Madoka) Sunamura, cardioloog, werkzaam in het Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland en Stichting Capri Hartrevalidatie te Rotterdam [NVVC]

- Dr. V.M. (Victor) Niemeijer, sportarts, werkzaam in het Elkerliek ziekenhuis te Helmond [VSG]

- Dr. J.A. (Aernout) Snoek, sportarts, werkzaam in het Isalaziekenhuis te Zwolle [VSG]

- D.A.A.J.H. (Dafrann) Fonteijn, revalidatiearts, werkzaam in het Reade centrum voor revalidatie en reumatologie te Amsterdam [VRA]

- Dr. H.J. (Erik) Hulzebos, klinisch inspanningsfysioloog-fysiotherapeut, werkzaam in het Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht te Utrecht [KNGF]

- E.A. (Eline) de Jong, Gezondheidszorgpsycholoog, werkzaam in het VieCuri Medisch Centrum te Venlo en Venray [LVMP] (vanaf mei 2023)

- Dr. N. (Nina) Kupper, associate professor, werkzaam in de Tilburg Universiteit te Tilburg [LVMP] (vanaf juli 2022)

- S.C.J. (Simone) Traa, klinisch psycholoog, werkzaam in het VieCuri Medisch Centrum te Venlo [LVMP] (tot mei 2023)

- Dr. V.R. (Veronica) Janssen, GZ-psycholoog in opleiding tot klinisch psycholoog, werkzaam in het Leids Universitair medisch centrum te Leiden [LVMP] (tot maart 2022)

- I.G.J. (Ilse) Verstraaten MSc., beleidsadviseur, werkzaam bij Harteraad te Den Haag [Harteraad] (vanaf december 2021)

- H. (Henk) Olk, ervaringsdeskundige [Harteraad] (vanaf juni 2022)

- A. (Anja) de Bruin, beleidsadviseur, werkzaam bij Harteraad te Den Haag [Harteraad] (tot november 2021)

- Y. (Yolanda) van der Waart, ervaringsdeskundige [Harteraad] (tot maart 2022)

- K. (Karin) Verhoeven-Dobbelsteen, gedifferentieerde hart en vaat verpleegkundige werkzaam als hartrevalidatie verpleegkundige, werkzaam in het Bernhoven Ziekenhuis te Uden [NVHVV] (vanaf juni 2022)

- R. (Regie) Loeffen, gedifferentieerde hart en vaat verpleegkundige werkzaam als hartrevalidatie verpleegkundige, werkzaam in het Canisius Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis te Nijmegen [NVHVV] (vanaf juni 2022)

- M.J. (Mike) Kuyper, MSc, verpleegkundig specialist, werkzaam in de Ziekenhuisgroep Twente te Almelo [NVHVV] (tot juni 2022)

- K.J.M. (Karin) Szabo-te Fruchte, gedifferentieerde hart en vaat verpleegkundige werkzaam als hartrevalidatie verpleegkundige, werkzaam in het Medisch Spectrum Twente te Enschede [NVHVV] (tot juni 2022)

Meelezers:

- Drs. I.E. (Inge) van Zee, revalidatiearts, werkzaam in Revant te Goes [VRA]

- T. (Tim) Boll, GZ-psycholoog, werkzaam in het St Antonius Ziekenhuis te Nieuwegein [LVMP]

- K. (Karin) Keppel-den Hoedt, medisch maatschappelijk werker, werkzaam in de Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep te Den Helder [BPSW] (vanaf mei 2023)

- C. (Corrina) van Wijk, medisch maatschappelijk werker, werkzaam in het rode Kruis Ziekenhuis te Beverwijk [BPSW] (tot mei 2023)

- D. Daniëlle Conijn, beleidsmedewerker en richtlijnadviseur Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap Fysiotherapie [KNGF]

Meelezers bij de module Werkhervatting, vanuit de richtlijnwerkgroep Generieke module Arbeidsparticipatie:

- Jeannette van Zee (senior adviseur patiëntbelang, PFNL)

- Michiel Reneman (hoogleraar arbeidsrevalidatie UMCG)

- Theo Senden (klinisch arbeidsgeneeskundige)

- Asahi Oehlers (bedrijfsarts, namens NVAB)

- Frederieke Schaafsma (bedrijfsarts en hoogleraar AmsterdamUMC)

- Anil Tuladhar (neuroloog)

- Ingrid Fakkert (arts in opleiding tot verzekeringsarts)

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. B.H. (Bernardine) Stegeman, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. J.M.H. (Harm-Jan) van der Hart, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Mogelijke restrictie |

|

Van 't Hof (voorzitter) |

Hoogleraar Interventie Cardiologie Universiteit Maastricht |

|

|

Geen |

|

Fonteijn |

Revalidatiearts |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Hulzebos |

Klinisch Inspanningsfysioloog - (sport)Fysiotherapeut |

|

Geen |

Geen |

|

Jong |

GZ-psycholoog, betaald, (poli-)klinische behandelcontacten binnen het ziekenhuis. |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Kupper |

Associate professor bij Tilburg University (betaald) |

Associate editor bij Psychosomatic Medicine (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Loeffen |

Hartrevalidatieverpleegkundige |

werkgroep hartrevalidatie NVHVV |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Niemeijer |

Sportarts Elkerliek Ziekenhuis Helmond |

Dopingcontrole official Dopingautoriteit 4u/mnd betaald (tot eind 2023) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Olker |

Patiëntenvertegenwoordiger |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Snoek |

Sportarts |

|

Geen |

Geen |

|

Sunamura |

Cardioloog |

Cardioloog, verbonden aan Stichting Capri Hartrevalidatie |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Verhoeven |

Hartrevalidatieverpleegkundige |

NVHVV voorzitter werkgroep Hartrevalidatie |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Verstraaten |

Beleidsadviseur Harteraad |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Vromen |

Cardioloog |

Commissie Preventie en Hartrevalidatie NVVC (Onbetaald) Interdisciplinair Netwerk Hartrevalidatie (INH) (onbetaald) + Werkgroeplid KNGF Richtlijn hartrevalidatie 2024. |

Werkzaamheden voor PROFIT-trial, onderzoek naar het effect van hartrevalidatie/leefstijl bij stabiele angina pectoris. Onderzoek (maar niet mijn eigen bijdrage) gefinancierd door ZonMW |

Geen |

|

Werkgroepleden die niet langer meer participeren |

||||

|

De Bruin |

Beleidsadviseur |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Janssen |

LUMC: GZ-psycholoog (0,4 fte) |

Docent NPi: cursus Hartrevalidatie |

CVON2016-12 (gaat over eHealth voor hartrevalidatie, sponsor: ZonMw en de Hartstichting) gepubliceerd Betrokken bij de ontwikkeling van een leidraad voor een online PEP-module Hartrevalidatie.

|

Geen |

|

Kuyper |

Verpleegkundig specialist cardiologie, Ziekenhuisgroep Twente (betaald, vast in loondienst) |

Werkgroeplid NVHVV (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Szabo-te Fruchte |

Verpleegkundig coördinator hartrevalidatie |

Nederlandse Vereniging voor Hart- en Vaatverpleegkundigen (NVHVV) werkgroeplid hartrevalidatie |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Traa |

Klinisch psycholoog - psychotherapeut bi VieCuri Medisch Centrum, afdeling Medische Psychologie |

1 x per jaar docent RINO Zuid - GZ- & KP-opleiding |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door afgevaardigde patiëntenvereniging en patiëntvertegenwoordiger in de werkgroep. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Harteraad en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Interventies gericht op psychische doelen |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met hart- en vaatziekten. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijnmodule (NVVC, 2011) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen tijdens een invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 en R Studio werden gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Voor de volgende modules is gebruik gemaakt van ChatGPT voor het schrijven van de overwegingen:

- Module Diagnosegroepen;

- Module Screening van fysieke capaciteit en activiteit.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Algemene informatie

|

Cluster/richtlijn: NVVC Multidisciplinaire richtlijn Hartrevalidatie |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag/modules: Welk bewijs is er voor de effectiviteit van behandeling van de psychologische risicofactoren in CHD patiënten wat betreft psychologische uitkomsten (inclusief kwaliteit van leven)? |

|

|

Database(s): Embase.com, Ovid/Medline |

Datum: 17 juli 2023 |

|

Periode: vanaf 1999 |

Talen: geen restrictie |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Alies van der Wal |

Rayyan review: https://rayyan.ai/reviews/726363 |

|

BMI-zoekblokken: voor verschillende opdrachten wordt (deels) gebruik gemaakt van de zoekblokken van BMI-Online https://blocks.bmi-online.nl/ Bij gebruikmaking van een volledig zoekblok zal naar de betreffende link op de website worden verwezen. |

|

|

Toelichting: Voor deze vraag is gezocht op de elementen:

Het sleutelartikel wordt gevonden met deze search |

|

|

Te gebruiken voor richtlijnen tekst: Nederlands In de databases Embase.com en Ovid/Medline is op 17 juli 2023 systematisch gezocht naar systematische reviews, RCTs en observationele studies over (bepaalde) psychologische interventies bij CHD patiënten. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 912 unieke treffers op.

Engels On the 17th of July 2023, a systematic search was performed in the databases Embase.com and Ovid/Medline for systematic reviews, RCTs and observational studies about (certain) psychological interventions in CHD patients. The search resulted in 912 unique hits. |

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

EMBASE |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SR |

179 |

156 |

221 |

|

RCT |

507 |

483 |

691 |

|

Observationele studies |

242 |

165 |

299 |

|

Totaal |

928 |

804 |

912* |

*in Rayyan

Zoekstrategie

Embase.com

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#13 |

#10 OR #11 OR #12 |

928 |

|

#12 |

#5 AND (#8 OR #9) NOT (#10 OR #11) = observationeel |

242 |

|

#11 |

#5 AND #7 NOT #10 = RCT |

507 |

|

#10 |

#5 AND #6 = SR |

179 |

|

#9 |