Operatietechnieken

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de rol van duurzaamheid bij robot-geassisteerde laparoscopische chirurgie in vergelijking met conventionele laparoscopische chirurgie of open chirurgie bij patiënten met een indicatie voor een operatie?

Zie een schematisch overzicht van de module in ‘Samenvatting’.

Aanbeveling

Wees bewust dat robot-geassisteerde chirurgie een grotere (negatieve) impact heeft op het milieu dan andere operatietechnieken. Dit wordt met name veroorzaakt door het hoge energieverbruik en de inzet van disposables bij robot-geassisteerde chirurgie.

Duurzaamheid moet worden meegenomen in de overwegingen voor een operatietechniek. Als op basis van de literatuurconclusies en overwegingen geen duidelijke voorkeur is, zet dan de meest duurzame operatietechniek in.

Overweeg de patiënt te informeren over de milieu-impact van de behandeling en neem duurzaamheid mee in de gezamenlijke besluitvorming.

Indien chirurgie wordt toegepast:

- Laat duurzaamheid meewegen in de te kiezen operatietechniek bij de indicatiestelling (R1-Refuse).

- Besteed aandacht aan het reduceren van het gebruik van disposables (R2-Reduce).

- Optimaliseer de inzet van duurzame energie en energiezuinige apparatuur (R2-Reduce).

- Neem duurzaamheid mee in het (her)ontwerp van technologieën (R3-Redesign) en wijs de industrie hierop.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Op basis van de beschikbare literatuur is gekeken naar de milieu-impact van verschillende operatietechnieken. Er zijn drie Life Cycle Assessments (LCA’s) geïncludeerd in de literatuursamenvatting. Deze LCA’s verschillen onder andere in methodiek (EIO-LCA, Attributional LCA, Hybrid LCA-ISO 14040-44), databases en aannames. Daarnaast zijn er enkele methodologische beperkingen (risk of bias, indirectheid). De bewijskracht van de literatuur is daardoor laag voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten ‘climate change’ en ‘waste’. Op basis van de GRADE methode ter beoordeling van de literatuur kunnen geen sterke conclusies geformuleerd worden over de precieze mate van milieu-impact van de operatietechnieken. Echter, ondanks de methodologische verschillen tussen de LCA’s, wijzen de resultaten wel dezelfde richting op. Gezien deze consequente richting, geïdentificeerde hotspots en de urgentie om de milieu-impact te verminderen, beschouwt de werkgroep dit als afdoende ondersteuning om sterke aanbevelingen te formuleren.

De geïncludeerde LCA’s zijn kritisch beoordeeld volgens Drew (2021), zie de bijlage 2 ‘Critical appraisal of LCA’s’. De kwaliteit van de studies wordt hiermee beoordeeld op basis van de methodologie van een LCA. Dit scoresysteem bestaat uit 16 beoordelingscriteria, die zijn verdeeld over de verschillende fasen van een LCA. Het behandelt een reeks indicatoren voor studiekwaliteit, zoals interne validiteit, externe validiteit, consistentie, transparantie en bias. De procentuele score geeft een indicatie van de algehele studiekwaliteit. Een hogere score duidt op een hogere algehele studiekwaliteit. Thiel (2015) scoort met 80% het hoogst in vergelijking met Power (2012) en Woods (2015), die respectievelijk 54% en 57% scoren.

In de drie studies (Power, 2012; Thiel, 2015; Woods, 2015) worden verschillende operatietechnieken met elkaar vergeleken op duurzaamheidsuitkomsten. De werkgroep heeft klinische uitkomsten (bijv. complicaties, overleving, opnameduur) in deze module niet meegenomen. De werkgroep wil er echter wel op wijzen dat klinische uitkomsten van belang zijn in duurzaamheidsvraagstukken.

Hoewel de bewijskracht van de cruciale uitkomstmaten uit komt op laag, wijzen de resultaten er consistent op dat robot-geassisteerde laparoscopische chirurgie de grootste milieu-impact heeft, in vergelijking met conventionele laparoscopische chirurgie of open chirurgie (Power, 2012; Thiel, 2015; Woods, 2015). Open chirurgie komt uit de LCA’s als operatietechniek met de laagste negatieve milieu-impact. Hierbij is het belangrijk te benadrukken dat in de LCA’s de postoperatieve periode niet is meegenomen en in de analyses alleen specifiek is gekeken naar de operatie zelf. De werkgroep is zich ervan bewust dat postoperatieve factoren (zoals complicaties, heropnames, opnameduur) de milieu-impact kunnen veranderen en dat dit moet worden meegenomen in de overwegingen voor een operatietechniek.

Het is van belang om te evalueren waar in deze operatietechnieken de milieu ‘hotspots’ met de grootste milieu-impact zitten. In die ‘hotspots’ zit immers de grootste verbeterruimte. De drie LCA’s identificeren verschillende ‘hotspots’: energieverbruik (o.a. voor chirurgische machines, verlichting, verwarming/ventilatie/air-conditioning), gebruik van gassen (o.a. verschillende anesthesiegassen en CO2 voor abdominale insufflatie) en het gebruik van disposables en reusables (o.a. productie, reiniging en sterilisatie, afvalverwerking). In module ‘disposables versus reusables’ en module ‘anesthesie’ wordt de milieu-impact hiervan geëvalueerd.

De hotspots worden geëvalueerd middels de ‘R-ladder (strategieën van circulariteit)’ (zie figuur 1, gebaseerd op Cramer, 2014; Hanemaaijer; 2018; Potting, 2016; Reike, 2018). De R-ladder laat zien dat de hoogste prioriteit om duurzaam te werken ‘refuse’ is, oftewel, niet gebruiken. Hoe lager het grondstofgebruik, des te hoger op de R-ladder en hoe dichter je bij circulair werken bent.

Figuur 1. Prioriteitsvolgorde circulariteit strategieën

Refuse (R1) en Reduce (R2)

De drie LCA’s impliceren dat robot-geassisteerde laparoscopie de grootste negatieve milieu-impact heeft. Soms is het mogelijk eenzelfde operatie met verschillende operatietechnieken uit te voeren. De werkgroep stelt dat duurzaamheid met andere overwegingen moet worden meegenomen in de beslissing voor een specifieke operatietechniek. De werkgroep adviseert om voor de techniek met de laagste milieu-impact te kiezen, als op basis van de literatuurconclusies en overwegingen geen duidelijke voorkeur is. Bepaalde operatietechnieken kunnen op deze manier ‘geweigerd’ (R1-Refuse) worden, door bijvoorbeeld het aanscherpen van indicatiestellingen. Indien de operatietechniek ‘best practice’ is, kan er worden gekeken of de hotspots kunnen worden aangepakt om toch de milieu-impact van de desbetreffende operatietechniek te verlagen.

Een LCA laat tevens zien waar de grootste milieu-impact (‘hotspot’) in het proces zit. Twee LCA’s (Woods, 2015; Thiel, 2015) laten zien dat de robot-geassisteerde laparoscopie de meeste energie verbruikt, waarbij inzet van het robotsysteem dit verschil bewerkstelligt. De hotspot ‘energie’ kan worden onderverdeeld in energie voor chirurgische machines en instrumentaria, energie voor verlichting, verwarming, ventilatie en airconditioning en er wordt energie verbruikt voor het verkrijgen van CO2 voor insufflatie bij minimaal invasieve chirurgie (MIC). Thiel (2015) laat zien dat verwarming, ventilatie en luchtbehandeling op operatiekamers de grootste bijdrage leveren aan het totale energieverbruik. Daarnaast is de productie van disposables een belangrijke milieu ‘hotspot’ en draagt dit voor het grootste deel bij aan de totale milieu-impact (Thiel, 2015). Ten aanzien van R1-Refuse, zou het niet verbruiken van energie de beste keuze zijn. Indien een operatiekamer niet in gebruik is, wordt geadviseerd om eventuele machines, luchtbehandeling of verlichting uit te zetten. Wanneer het niet mogelijk is om dit uit te schakelen, is het verminderen van het verbruik van energie (R2-Reduce) een optie. Bijvoorbeeld middels het efficiënter inzetten van luchtbehandeling (zie ook module ‘luchtbehandeling’), het regelmatig onderhouden van mechanische apparatuur/ instrumentaria, het vernieuwen van mechanische instrumentaria en filters, het beperken van energielekken of door intensievere toepassing van meer duurzame energiebronnen.

Redesign (R3)

Operatietechnieken hebben zich over de afgelopen decennia in rap tempo doorontwikkeld. Nieuwe robotsystemen doen hun intrede en steeds complexere instrumentaria worden voor MIC ontwikkeld. In het design van apparatuur en instrumenten zal, in het kader van de negatieve milieu-impact, duurzaamheid moeten worden meegenomen.

Het robotsysteem gebruikt relatief veel energie en produceert veel afval (Woods, 2015; Thiel, 2015). Dit biedt kansen voor verbeteringen in het design. De drie LCA’s identificeren het gebruik van disposables als één van de ‘hotspots’, mede vanwege de hoeveelheid afval. Echter de productie van disposables blijkt voornamelijk van grote invloed te zijn op de uitkomstmaten ‘CO2 footprint’, ‘ozone depletion’ en ‘acidification’ (Thiel, 2015). Binnen de robotchirurgie worden instrumenten wel al hergebruikt, maar hier zit vaak al snel een maximum aan. De uitdaging ligt bij de industrie om instrumenten zodanig te ontwerpen dat deze zoveel mogelijk hergebruikt kunnen worden (verlengen van de levensduur), zonder het risico op patiëntveiligheid (zoals infecties) aan te tasten (zie ook module ‘disposables versus reusables’). De industrie zal moeten worden uitgedaagd om hieraan mee te werken in de context van een circulaire economie.

Daarnaast draagt ook de hotspot ‘insufflatie van de buik’ bij laparoscopische operaties in grote mate bij aan de ‘CO2 footprint’ en ‘ozone depletion’ (Thiel 2015; Power, 2012). Door een duurzamere manier te ontwikkelen (R3-Redesign) voor CO2 winning, valt milieuwinst te behalen. Denk bijvoorbeeld aan een duurzamere productiemethode of duurzaam transport. Het verkrijgen van CO2 voor MIC (productie, opwekken/leveren, gasextractie, transport) leidt gemiddeld tot 141 kg aan CO2 emissies per MIC operatie (Power, 2012). Dit is vergelijkbaar met een enkele autorit (benzineauto, verbruik 1:14) van Amsterdam naar Stuttgart (±620km). De werkgroep stelt dat er meer aandacht moet komen voor een duurzame CO2 winning om op dit gebied milieuwinst te behalen. Daarnaast is het mogelijk om met minder CO2 voor insufflatie te werken, dus door een lagere druk te gebruiken. Met deze lagere druk wordt minder CO2 verbruikt, wat positief bijdraagt aan de impact op het milieu (R2-Reduce). Dit kan bijvoorbeeld worden uitgevoerd met het AirSeal® systeem, dat naast het behoud van een pneumoperitoneum met lagere drukken ook het gas CO2 recirculeert en onnodig verlies voorkomt (Sroussi, 2017; Herati, 2009; Luketina, 2014; Bucur, 2016; George, 2015).

Wat betreft R3-Redesign is het van belang dat duurzaamheid al in de ontwikkelingsfase van medische hulpmiddelen wordt geïntegreerd. Het is daarom aan zorgverleners om de industrie bewust te maken van de noodzaak van duurzame medische hulpmiddelen. Daarnaast is voor een succesvolle implementatie samenwerking nodig tussen zorgverleners, zorginstellingen en de industrie (zoals bijvoorbeeld fabrikanten, leveranciers).

Re-use (R4)

Binnen de verschillende apparaten en disposables die worden gebruikt bij de verschillende operatietechnieken, kan hergebruik een grote rol spelen. Het is van belang om goed te kijken hoe ‘oude’ apparatuur opnieuw ingezet kan worden. Daarnaast tonen de drie LCA’s aan dat de productie van disposables een grote impact op het milieu heeft. Indien de patiëntveiligheid het toelaat, is hergebruik van materialen en apparatuur dan ook een uiterst relevante optie. De industrie moet ertoe worden aangezet om hergebruik mogelijk te maken en de milieu-impact te verlagen. Daarnaast speelt regelgeving een belangrijke rol. Optimalisatie van de wetgeving (Medical Device Regulation – MDR) met als doel de regels rondom hergebruik te verruimen zal positief kunnen bijdragen.

Repair (R5), Refurbish (R6), Remanufacture (R7)

De factoren R5-Repair, R6-Refurbish en R7-Remanufacture gaan binnen de operatietechnieken nauw met elkaar samen. Voordat een product of apparaat wordt afgedankt, is het van belang om opnieuw te kijken of de levensduur nog verlengd kan worden. Indien een product modulair is opgebouwd, geeft dat de mogelijkheid om bepaalde delen te vervangen en andere delen langer mee te laten gaan. De werkgroep adviseert om het repareren of opknappen van producten standaard te overwegen.

Repurpose (R8), Recycling (R9), Recover (R10)

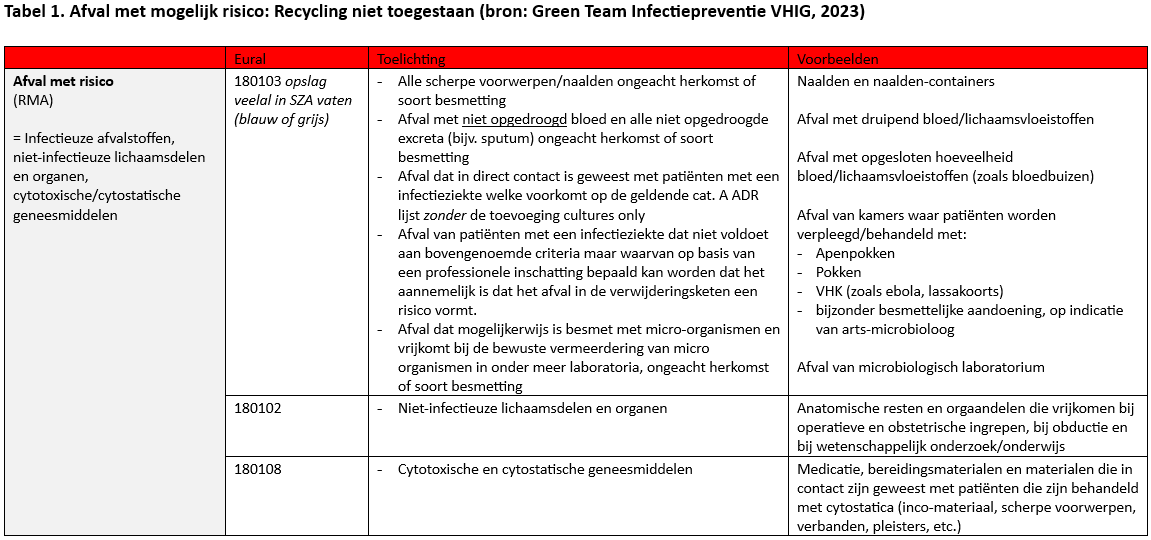

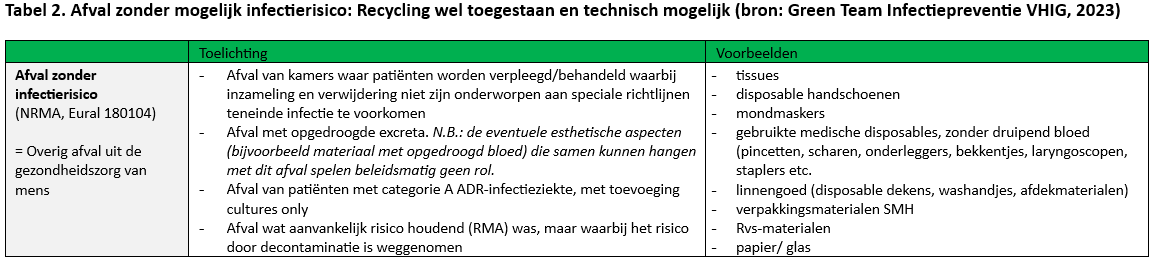

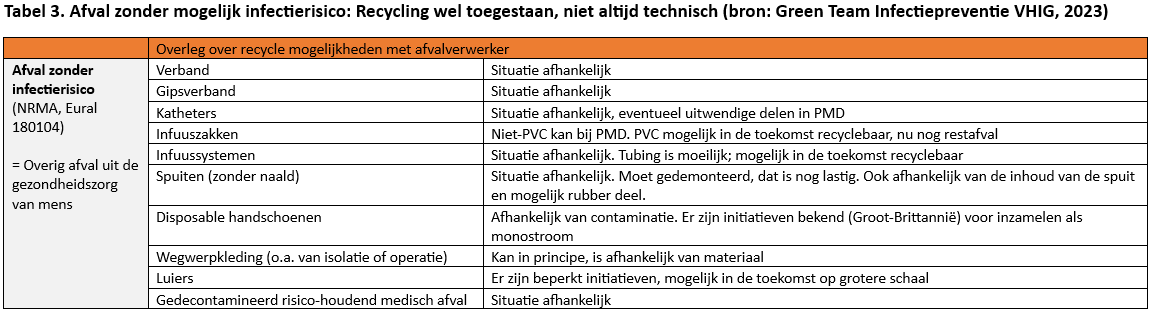

Indien medische apparatuur of producten die gebruikt worden bij de verschillende operatietechnieken niet meer gebruikt kunnen worden waarvoor zij zijn bedoeld, kan er worden gekeken naar een nieuw doeleinde (R8-Repurpose) of het hergebruiken (R9-Recycling) van de grondstoffen van het product. Kijk of het mogelijk is om samen te werken met de afvalverwerker van het ziekenhuis.. Een deel van het afval van een operatie zal moeten worden verbrand als het Specifiek Ziekenhuis Afval (SZA) betreft. In Tabel 1-3 zijn de criteria en het proces weergeven waarop in ziekenhuizen het onderscheid tussen restafval (afval zonder risico) en SZA (afval met risico) gemaakt kan worden en waar recycling mogelijk wordt geacht (Green Team Infectiepreventie VHIG, 2023) (R9-Recycling). Indien afval moet worden verbrand, moet er naar worden gestreefd om dit met zoveel mogelijk energieterugwinning te laten plaatsvinden (R10-Recover).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Om meer duurzame zorg te realiseren en duurzaamheidsinitiatieven te initiëren, is het cruciaal om voldoende maatschappelijk draagvlak te hebben bij patiënten en zorgverleners. Meer duurzame keuzes in de zorg vraagt gedragsverandering van zowel de patiënt als zorgverlener. Goede voorlichting en bewustwording is hierbij van groot belang. Meer informatie en bewijs zal hier in de toekomst aan bijdragen. Vanzelfsprekend is het belangrijk dat patiënten goed meegenomen worden in besluitvorming.

Duurzamere alternatieven in gebruik rondom een operatie zullen indirect ook voor patiënten een positief effect hebben. Voor de patiënt en zorgverlener staat een veilige en effectieve behandeling voorop.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De werkgroep verwacht dat in veel gevallen de behandelopties met de laagste milieu-impact zullen resulteren in kostenbesparing. Indien wordt gekozen voor het hoogst haalbare op de ladder van circulariteit (R1-Refuse, R2-Reduce), zullen bijvoorbeeld bepaalde producten niet of minder gebruikt worden. De werkgroep adviseert dan ook bij de keuze voor een bepaalde operatietechniek naast klinische uitkomsten duurzaamheid mee te nemen in de overwegingen. De winst in duurzaamheid weegt op tegen de eventueel hogere kosten (bijv. investering voor reusable instrumenten, investering in technologische ontwikkeling). Daarnaast heeft de investering in technologische ontwikkeling van open chirurgie naar minimaal invasieve chirurgie (laparoscopie, robot) geleid tot een kortere opnameduur voor de patiënt met daarbij gepaard gaand lagere kosten voor het postoperatieve traject (Laudicella, 2016; Diaz, 2022) en leidt een kortere opnameduur tevens tot een lagere milieu-impact.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De keuze van een operatietechniek ligt bij de zorgverlener en de patiënt, en wordt bepaald door veel verschillende factoren (bijv. (kosten-)effectiviteit, risico op complicaties, tijd tot herstel, indicatie). De werkgroep vermoedt dat duurzaamheid met betrekking tot de keuze in operatietechnieken nog niet als doorslaggevende factor beschouwd wordt. Het vergt bewustwording over de impact van de verschillende interventies en hun hotspots om duurzaamheid mee te kunnen laten wegen in een beslissing. Daarnaast zal het aanvaarden van het meenemen van duurzaamheid in de keuze voor een operatietechniek een mogelijke drempel zijn. Het is van belang dat patiëntveiligheid voorop staat, maar de werkgroep acht het cruciaal dat duurzaamheid naast andere overwegingen wordt meegenomen. Het is aan richtlijncommissies om per casus te bepalen welke afwegingen acceptabel zijn bij de keuze tot een specifieke operatietechniek.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Op basis van de gevonden literatuur is de bewijskracht voor duurzaamheidsuitkomsten laag tot zeer laag. Echter, wijzen de resultaten van de LCA’s consequent dezelfde richting op, wat inzicht geeft in waar de grootste milieu-impact zich bevindt. Daarnaast benadrukt de werkgroep de urgentie om de milieu-impact te verminderen. De werkgroep beschouwt dit tezamen als afdoende ondersteuning om sterke aanbevelingen te doen. Overwegingen richten zich voornamelijk op R1-Refuse, R2-Reduce en R3-Redesign. De werkgroep acht het uiterst belangrijk om meer bewustwording op het gebied van duurzaamheid te creëren in de zorg.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Met het ondertekenen van de ‘Green Deal Duurzame Zorg’ dient de gezondheidszorg rekening te houden met de invloed van behandelingen op het milieu (Green Deal, 2022). Opereren gaat gepaard met een relatief grote hoeveelheid afval en mogelijk varieert de milieu-impact tussen verschillende operatietechnieken. In het algemeen zijn er drie operatietechnieken beschikbaar (robot-geassisteerde-, laparoscopische- en open chirurgie) voor dezelfde indicatie. De robot-geassisteerde operatietechniek wordt steeds vaker uitgevoerd in de Nederlandse praktijk (Tummers, 2021). De meest recente studies tonen geen grote verschillen in effectiviteit aan tussen robot-geassisteerde en laparoscopische chirurgie (Aiolfi, 2021; Muaddi, 2021). Wanneer de uitkomsten van operatietechnieken voor de patiënt vergelijkbaar zijn, kan er overwogen worden om te kiezen voor de meest duurzame operatietechniek. Het is momenteel nog onduidelijk welke invloed de betreffende operatietechniek heeft op duurzaamheid. In deze module worden de duurzaamheidsuitkomsten van de drie verschillende operatietechnieken met elkaar vergeleken.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Climate change (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery has a larger impact on climate change (CO2 footprint/Global Warming Potential) when compared to conventional laparoscopic surgery or open surgery.

Sources: Power, 2012; Woods, 2015; Thiel, 2015 |

2. Waste (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery has a larger waste production when compared to conventional laparoscopic surgery or open surgery.

Sources: Power, 2012; Woods, 2015; Thiel, 2015 |

3. Acidification (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect on acidification when robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery is compared to conventional laparoscopic surgery or open surgery.

Source: Thiel, 2015 |

4. Eutrophication (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect on eutrophication when robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery is compared to conventional laparoscopic surgery or open surgery.

Source: Thiel, 2015 |

5. Human toxicity (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect on human toxicity when robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery is compared to conventional laparoscopic surgery or open surgery.

Source: Thiel, 2015 |

6. Ecotoxicity (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect on ecotoxicity when robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery is compared to conventional laparoscopic surgery or open surgery.

Source: Thiel, 2015 |

7. Ozone depletion (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect on ozone depletion when robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery is compared to conventional laparoscopic surgery or open surgery.

Source: Thiel, 2015 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Power (2012) describes an LCA to quantify the CO2 footprint of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) compared to open surgery in the United States. MIS included robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery and laparoscopic surgery. A total of 2,520,223 MIS procedures from the year 2009 were included. The analysis compared MIS procedures to traditional open surgery, using an Economic Input-Output-LCA (EIO-LCA). Therefore, prior to the analysis, varying aspects between MIS and open surgery were determined and only these factors were included in the analysis to quantify the CO2 footprint. Other fixed components of the overall CO2 footprint common to surgery in general (e.g. operating theatre, electricity use, patient travel, paper products used) were considered equivalent and were not taken into account. Different scopes of emissions were identified:

- Scope 1 CO2 emissions: The CO2 emission was defined as the amount of gas that was used for insufflation during MIS.

- Scope 2 and 3 CO2 emissions: The CO2 emissions were defined as all other processes before and after the MIS procedure. Furthermore, manufacturing and transportation of CO2 cylinders, used to transport the CO2 for insufflation, were taken into account.

Emissions related to the manufacturing process of the disposable instruments and to the postoperative stay were not included in the analysis. Thereby, not all disposable instruments were taken into account. Next to that, electricity use was considered equivalent, although it is expected to differ between the operating techniques, in particular between MIS and open surgery. MIS uses electricity driven instruments and cameras and in addition the robot uses robotic arms which require electricity. The relevant outcome measure was climate change (defined as CO2 footprint).

Woods (2015) retrospectively reviewed 150 procedures of the consecutive and most recent patients to have undergone a staging procedure for endometrial cancer for three surgical modalities (50 per arm): robot-assisted laparoscopy (RA-LSC), conventional laparoscopy (LSC) and laparotomy. The functional unit was one endometrial staging procedure. Collected clinical data from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, NY, USA, spanning the years 2008-2011, consisted of: age, body mass index (BMI), procedure type, operating time, history of prior abdominal surgery, length of stay, uterine weight, and surgical instruments used. The relevant outcome measures included climate change (defined as CO2 footprint) and waste. CO2 footprint was calculated by using an attributional LCA method (PAS 2050, GHG Protocol). Only energy and waste were included in this analysis. Data on energy and waste were obtained from previous studies, the National Energy Foundation and the US Energy Information Administration. Waste production (in kg) was determined based on operating room instrument data, specific to each modality. Disposal of 1 kg waste in a municipal landfill was considered equivalent to 1 kg CO2 equivalents. Energy expenditure (in kWh) was calculated based on independent source data. Energy consumption was categorized in environmental, instrumental, robotic system and equipment. The total energy consumed per category was multiplied by the operative time, to establish a unique energy consumption value for each surgery. Emissions for transport and manufacturing of instruments and goods and for postoperative stay were not considered.

Thiel (2015) used a hybrid LCA framework (ISO 14040-44) to quantify the environmental emissions of four types of hysterectomy (vaginal, abdominal, laparoscopic, robotic). The functional unit of the study was one hysterectomy. This research used a hybrid LCA framework, by incorporating process LCA data and Economic Input Output LCA (EIO-LCA) data. Monte Carlo simulations were used to quantify the variability and uncertainty in emissions for each component of a hysterectomy. Waste (in kg) was deduced from the surgeries of patients that underwent an abdominal, a laparoscopic, or a robotic hysterectomy for noncancer related reasons. For one year, waste from 62 cases of each type of hysterectomy were quantified and characterized (17 laparoscopic and 15 abdominal, vaginal, and robotic). A life cycle inventory was conducted of the data collected through waste audits and site assessments, followed by the life cycle impact assessment, where environmental impacts for the inputs and outputs of the four types of hysterectomy were calculated for both process LCA and EIO-LCA. Relevant outcome measures included climate change (defined as CO2 footprint), waste, acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, ecotoxicity, and ozone depletion. The environmental impact of postoperative stay was not considered.

Results

1. Climate Change

All three studies (Power, 2012; Woods, 2015; Thiel, 2015) reported on CO2 footprint.

Power (2012) reported that MIS had more CO2 emissions (355,924 tonnes/year) in comparison to open surgery. Scope 1, gas that was used during MIS for insufflation, resulted in 303 tonnes of CO2-emissions. Scope 2-3, CO2 emissions (CO2 capture/compression, transportation of CO2 cylinders and incineration of disposable instruments) resulted in 355,621 tonnes of CO2-emissions. This LCA of MIS, showed that the biggest contributor in CO2 emissions is the capture/compression of CO2 for insufflation. This is mainly caused by industrial gas manufacturing, followed by the actual use of the CO2 for insufflation, the transportation of the gas, and the incineration of the disposable instruments.

Woods (2015) reported that the CO2 footprint (based on waste and consumed energy) was 4,498 CO2 equivalents for all 150 endometrial staging procedures. This corresponds with 30 kg CO2 equivalents/patient. A robotic-assisted laparoscopy (RA-LSC) procedure resulted in a CO2 footprint of 40.3 kg CO2 equivalents/patient, a laparoscopy (LSC) procedure in 29.2 kg CO2 equivalents/patient, and a laparotomy (LAP) in 22.7 kg CO2 equivalents/patient. The CO2 footprint of the RA-LSC represents a 38% and 77% increase over LSC and LAP, respectively. The emission of 40.3 kg CO2 equivalents is comparable to a car ride from Amsterdam to Antwerp (±160 km, petrol car, 1:14). Comparing the three techniques, the RA-LSC has the biggest CO2 footprint. Both energy use and waste contribute most to this CO2 footprint. Due to the Da Vinci robot, the energy consumption of RA-LSC is the highest. The energy use for equipment is highest in the LSC group. Energy use adds more to the CO2 footprint than waste.

Thiel (2015) reported a difference in CO2 footprint between four types of hysterectomy. For all outcomes in this LCA, the surgical modality with the highest impact is defined as 100% and the other modalities are relatively compared to the modality with the highest impact. Robotic hysterectomies have the highest impact (100%), followed by the laparoscopic (65-70%), abdominal (35-40%) and vaginal modality (30-35%). In other words, the laparoscopic modality resulted in 30-35% less contribution to CO2 footprint than a robotic modality. This LCA showed the biggest environmental impact is attributable to the robotic and laparoscopic surgical approaches for a hysterectomy. Within these modalities, the use of single-use instruments, single-use materials (e.g. gowns, gloves), and anesthetic gases are the biggest contributors.

2. Waste

All three studies (Power, 2012; Woods, 2015; Thiel, 2015) reported on waste. Power (2012) only reported a total of 208,441 kg/year from disposable trocar and laparoscopic instrument use for MIS. No other data regarding waste was provided in this study.

Woods (2015) reported that the LAP group produced 8.3 kg CO2 equivalents of solid waste, the LSC group 11.2 kg CO2 equivalents, and the RA-LSC group 11.2 kg CO2 equivalents, respectively. Thus, RA-LSC represented a 74% and 36% increase over LAP and LSC, respectively. The solid waste consisted of four categories: infection control waste, single-use devices, consumable waste, and sterile wraps (see Table 1). The consumable waste was the largest contributor to solid waste for all surgical techniques. The largest amount of single-use device waste was generated by the LSC, followed by RA-LSC and LAP. The largest amount of waste for infection control was generated by the RA-LSC, followed by LAP and LSC. Sterile wraps contributed the least on waste for all surgical techniques.

Table 1. Types of waste described in Woods (2015)

|

Types of waste |

Description |

RA-LSC |

LSC |

LAP |

|

Infection control |

Drapes, Gowns, gloves |

4.035 kg CO2 eq. per patient (28% of total solid waste) |

1.60 kg CO2 eq. per patient (14% of total solid waste) |

1.60 kg CO2 eq. per patient (19% of total solid waste) |

|

Consumable |

Blue pack items (e.g. basins, suction tubing, towels, sponges) |

6.90 kg CO2 eq. per patient (48% of total solid waste) |

6.03 kg CO2 eq. per patient (54% of total solid waste) |

5.86 kg CO2 eq. per patient (71% of total solid waste) |

|

Sterile wrap |

Disposable blue wrap to maintain instrument sterility |

0.88 kg CO2 eq. per patient (6% of total solid waste) |

0.99 kg CO2 eq. per patient (9% of total solid waste) |

0.44 kg CO2 eq. per patient (5% of total solid waste). |

|

Single-use device |

Single-use devices (e.g. disposable energy-based surgical instruments, skin stapler) |

2.47 kg CO2 eq. per patient (17% of total solid waste) |

3.35 kg CO2 eq. per patient (30% of total solid waste) |

0.82 kg CO2 eq. per patient (10% of total solid waste) |

Thiel (2015) reported that the robotic approach for a hysterectomy produced the highest amount of waste, following the laparoscopic, abdominal, and vaginal approaches. Robotic hysterectomies produced 13.7 kg municipal solid waste (MSW) per patient, which resulted in a total of 30% more waste compared to the other approaches.

This consisted of 50% gloves and other plastics, 22% by weight by gowns, drapes and bluewraps, 18% paper, and 5% cotton.

Abdominal hysterectomies had an average of 9.2 kg of MSW production and produced the largest amount of cotton waste per surgery. Across all four surgeries, the gowns, drapes and bluewraps were the majority of the MSW (robotic: 22%, laparoscopic: 35%). Other types of plastics, from thin film packaging wrappers to hard plastic trays, ranged from 36% MSW for vaginal hysterectomies to 46% for robotic hysterectomies.

3. Acidification

Only Thiel (2015) reported on acidification for the four surgical hysterectomies. The robotic approach had the highest impact on acidification (100%), followed by laparoscopic (70-75%), abdominal (25%), and vaginal approach (20%).

4. Eutrophication

Only Thiel (2015) reported a difference in eutrophication for the four surgical hysterectomies. The robotic approach had the highest impact on eutrophication (100%), followed by the laparoscopic (70-75%), abdominal (60-65%), and vaginal approach (55%).

5. Human toxicity

Only Thiel (2015) reported a difference in human toxicity for the four surgical hysterectomies. Human toxicity was divided into two subcategories: carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic potential. The robotic approach had the highest impact in both carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic potential categories (100%). Regarding the carcinogenic impact, the robotic approach was followed by the abdominal (90-100%), laparoscopic (80%), and vaginal approach (80%). Regarding the non-carcinogenic impact, the robotic approach was followed by the laparoscopic (85-90%), abdominal (80-90%), and vaginal approach (70-75%).

6.Ecotoxicity

Only Thiel (2015) reported a difference in ecotoxicity for the four surgical hysterectomies. The robotic approach had the highest impact on ecotoxicity (100%), followed by the laparoscopic (90-95%), abdominal (90%), and vaginal approach (75%).

7. Ozone depletion

Only Thiel (2015) reported a difference in ozone depletion for the four surgical hysterectomies. The robotic approach had the highest impact on ozone depletion (100%), followed by the laparoscopic (60-65%), abdominal, and vaginal approach (0-5%).

Level of evidence of the literature

There are currently no widely recognized guidelines for designing, conducting, or reporting systematic reviews in LCA (Zumsteg, 2012). The Standardized Technique for Assessing and Reporting Reviews of LCA (STARR-LCA) checklist was developed based on the PRISMA statement (which was designed to help systematic reviewers transparently report why the review was done, what the authors did, and what they found) (Page, 2021; Zumsteg, 2012; Costa, 2019; Drew, 2021). The STARR-LCA proposed a critical appraisal tool to assess the level of evidence of LCAs (Drew, 2021) which is used in this module to provide an indication of the study quality (see Appendix 2 ‘Critical appraisal of LCAs’). This tool consists of 16 assessment criteria for the different phases of an LCA, covering a set of quality indicators (such as internal validity, external validity, consistency, transparency, bias). The score gives an indication of the current study quality (a higher score indicates a higher study quality).

The use of the GRADE approach in environmental and occupational health is relatively new, and likely to grow in coming years, as systematic reviews become more common in the field of LCAs and the limitations of expert-based narrative review methods are increasingly recognized (Aiassa, 2015; EFSA, 2010; Mandrioli, 2015; Morgan, 2016; Woodruff, 2014). Further research is warranted in this field (Morgan, 2019), which is acknowledged by the working group. Although standards for using GRADE for LCAs are lacking, the working group decided that the level of evidence starts for LCAs starts at grade high. After all, the working group is mainly interested in which interventions have the greatest impact on environmental sustainability and LCAs are the best method to assess this (see also the report: ‘Leidraad Duurzaamheid in richtlijnen’ (NVvH, 2023). Furthermore, the GRADE standards are followed as much as possible.

As the three included studies contained LCAs (Power, 2012; Woods, 2015; Thiel, 2015), the level of evidence started at grade high.

1. Climate Change

Three studies (Power, 2012; Woods, 2015; Thiel, 2015) reported on ‘climate change’. The level of evidence of this outcome measure was downgraded with 2 levels to low due to: risk of bias (-2; limitations on functional unit, unclear system boundaries or stages, missing system coverage, limited representativeness of data, limited transparency on characterization, sensitivity/uncertainty analyses were lacking, limitations inadequately critically appraised).

2. Waste

Three studies (Power, 2012; Woods, 2015; Thiel, 2015) reported on ‘waste’. The level of evidence of this outcome measure was downgraded with 2 levels to low due to: risk of bias (-2; limitations on functional unit, unclear system boundaries or stages, missing system coverage, limited representativeness of data, limited transparency on characterization, sensitivity/uncertainty analyses were lacking, limitations inadequately critically appraised).

3. Acidification

One study (Thiel, 2015) reported on ‘acidification’. The level of evidence of this outcome measure was downgraded with 3 levels to very low due to: risk of bias (-2; unclear system boundaries or stages, limited transparency on characterization, unclear reported results, sensitivity/uncertainty analyses were lacking, limitations inadequately critically appraised) and indirectness (-1; limited representativeness as data were only collected from one study including 62 hysterectomy cases).

4. Eutrophication

One study (Thiel, 2015) reported on ‘eutrophication’. The level of evidence of this outcome measure was downgraded with 3 levels to very low due to: risk of bias (-2; unclear system boundaries or stages, limited transparency on characterization, unclear reported results, sensitivity/uncertainty analyses were lacking, limitations inadequately critically appraised) and indirectness (-1; limited representativeness as data were only collected from one study including 62 hysterectomy cases).

5. Human toxicity

One study (Thiel, 2015) reported on ‘human toxicity’. The level of evidence of this outcome measure was downgraded with 3 levels to very low due to risk of bias (-2; unclear system boundaries or stages, limited transparency on characterization, unclear reported results, sensitivity/uncertainty analyses were lacking, limitations inadequately critically appraised) and indirectness (-1; limited representativeness as data were only collected from one study including 62 hysterectomy cases).

6. Ecotoxicity

One study (Thiel, 2015) reported on ‘ecotoxicity’. The level of evidence of this outcome measure was downgraded with 3 levels to very low due to risk of bias (-2; unclear system boundaries or stages, limited transparency on characterization, unclear reported results, sensitivity/uncertainty analyses were lacking, limitations inadequately critically appraised) and indirectness (-1; limited representativeness as data were only collected from one study including 62 hysterectomy cases).

7. Ozone depletion

One study (Thiel, 2015) reported on ‘ozone depletion’. The level of evidence of this outcome measure was downgraded with 3 levels to very low due to risk of bias (-2; unclear system boundaries or stages, limited transparency on characterization, unclear reported results, sensitivity/uncertainty analyses were lacking, limitations inadequately critically appraised) and indirectness (-1; limited representativeness as data were only collected from one study including 62 hysterectomy cases).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the role of environmental sustainability of robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery compared with conventional laparoscopic surgery or open surgery?

P: Patients who underwent surgery

I: Robot-assisted surgery

C: Conventional laparoscopic surgery or open surgery

O: Climate change (CO2 footprint/Global Warming Potential (GWP)), waste, acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, ecotoxicity, ozone depletion

Relevant outcome measures

Life cycle assessment (LCA) is a methodological tool used to quantitatively analyse the life cycle of products/activities within the context of environmental impact. The assessment comprises all stages needed to produce and use a product, from the initial development to the treatment of waste (the total life cycle). An LCA is mainly based on four phases: 1) goal and scope definition, 2) inventory analysis, 3) impact assessment, and 4) interpretation. The third phase is the life cycle impact assessment (LCIA), in which emissions and resource extractions are translated into a limited number of environmental impact scores by means of so-called characterisation factors. The ReCiPe model is a method for the impact assessment in an LCA (Huijbregts, 2016, Huijbregts, 2017). To determine the outcome measures regarding environmental impact, the ReCiPe model of the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (in Dutch: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu, RIVM) was used.

The outcomes determined by the working group are based on the ReCiPe model. The working group considered climate change (CO2 footprint/Global Warming Potential) and waste as critical outcome measures for decision making; and acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, ecotoxicity and ozone depletion as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Outcomes focused on environmental life cycle assessment (LCA) impact categories are relatively new in healthcare. Given the variety in scopes and methods of performing and reporting LCAs, the working group did not define a priori the minimal important difference. Differences between the techniques were evaluated by the working group after data extraction.

Glossary

- Acidification: Reduction of the pH due to acidifying effects of emissions. Acid deposition of acidifying contaminants on soil, groundwater, surface waters, biological organisms, ecosystems, and substances. Expressed in SO2 (sulfur dioxide) equivalents (Acero, 2015).

- Climate change: In the outcome category “climate change” we include two types of outcome measures:

- CO2 footprint: The total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions caused by an individual, organization, event, or product given a period of time. Expressed in CO2 equivalents adopting the GWP (The Carbon Trust, 2018).

- Global Warming Potential (GWP): A measure of how much energy 1 kg of a specific GHG will absorb over a given period of time, relative to the emission of 1 kg of carbon dioxide (CO2). The GWP is 1 for CO2. GWP was developed to allow comparisons of the global warming impacts of different gases (EPA, 2021). The larger the GWP, the more that a given gas contributes to climate change (the greater the global warming effect of the gas).

- Economic input-output life cycle assessment (EIO-LCA): EIO-LCA uses annual input–output economy models and links monetary values of the industry sector (such as building sector) to their environmental inputs/outputs.

- Ecotoxicity: Toxic effects of chemicals on ecosystems. Environmental toxicity is measured as three separate impact categories which examine freshwater (e.g. lakes and rivers), marine (e.g. estuaries and the ocean) and land. Ecotoxicity describes exposure and the effects of toxic substances on the environment (Acero, 2015). Common environmental toxicants are diethyl phthalate (enters environment through industries manufacturing cosmetics, plastic and many other commercial products), bisphenol A (found in many mass-produced products such as, medical devices, food packaging, cosmetics, computers), pesticides, and oil. It is expressed in 1,4-dichlorobenzene (DB) equivalents.

- Energy mix: All sources of energy used from which energy is produced that can be directly used, e.g. in the form of electricity. Sources can be coal, oil, natural gas, hydro, nuclear and other renewables (e.g. wind, solar, thermal).

- Eutrophication: Accumulation of nutrients in water. Eutrophication includes the effects on ecosystems found in land or water due to over-fertilization or excess supply of nutrients (e.g. algal bloom), which can lead to changes in ecosystems and diversity of species. Expressed in PO4 (phosphate) equivalents (Acero, 2015). This leads to ecosystem damage and has a negative effect on the climate.

- Hotspot: In a life cycle assessment (LCA) an "environmental hotspot" refers to a specific stage where a significant environmental impact is detected, presenting a significant opportunity for improvement.

- Human toxicity: Toxic effect of chemicals on humans. Human toxicity reflects the potential harm of a unit of chemical released into the environment, and it is based on the inherent toxicity of a compound and its potential dose (Acero, 2015). It is differentiated as non-cancer and cancer toxicity and affects human health. It is expressed in 1,4-dichlorobenzene (DB) equivalents.

- Hybrid instruments: Instruments which are partly disposable and partly reusable.

- Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): This is a methodology for assessing environmental impacts associated with all the stages of the life cycle of a commercial product, process, or service. An LCA mainly consists of four steps: 1) goal and scope, 2) inventory analysis, 3) impact assessment, and 4) interpretation.

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): This is the third phase of an LCA, which aims to evaluate the potential environmental and human health impacts resulting from the elementary flows determined in the LCI.

- Ozone depletion: Reduction of the stratospheric ozone layer due to emissions of ozone depleting substances. Damage to the ozone layer reduces its ability to prevent ultraviolet (UV) light entering the earth’s atmosphere, increasing the amount of carcinogenic UV light reaching the earth’s surface. Expressed in kg CFC-11 equivalents (Acero, 2015).

- Waste: Total amount of waste expressed in kilograms, such as for example plastics or (disposable) instruments.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Pubmed (via NCBI), Embase (via OVID), Web of Science (via Webofscience), Cochrane (via Cochrane library) and Emcare (via OVID) were searched with relevant search terms from 2000 until 7 December 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 202 hits. Studies for this module were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic reviews in which searches were performed in at least two databases, with a detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available, randomized controlled trials, (observational) comparative studies, Life Cycle Assessments;

- Full-text English or Dutch language publication; and

- Studies according to the PICO. This included studies that compared robot-assisted surgery with conventional laparoscopic or open surgery and included at least one of the outcomes conform the PICO.

Three studies were included for full text analysis. After reading the full text, all three studies were included in the literature summary of this module.

Results

Three studies were included in the analysis of the literature, which were all Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in Appendix 1 ‘Evidence table of LCAs’. The quality assessment of the studies is summarized in Appendix 2 ‘Critical appraisal of LCAs’.

Referenties

- Acero, 2015. Greendelta, LCIA methods: Impact assessment methods in Life Cycle Assessment and their impact categories. Version: 1.5.4. Date: 16 March 2015. Accessed at: https://www.openlca.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/LCIA-METHODS-v.1.5.4.pdf

- Aiolfi A, Lombardo F, Matsushima K, Sozzi A, Cavalli M, Panizzo V, Bonitta G, Bona D. Systematic review and updated network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing open, laparoscopic-assisted, and robotic distal gastrectomy for early and locally advanced gastric cancer. Surgery. 2021 Sep;170(3):942-951. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2021.04.014. Epub 2021 May 20. PMID: 34023140.

- Aiassa E, Higgins JP, Frampton GK, Greiner M, Afonso A, Amzal B, Deeks J, Dorne JL, Glanville J, Lövei GL, Nienstedt K, O'connor AM, Pullin AS, Raji? A, Verloo D. Applicability and feasibility of systematic review for performing evidence-based risk assessment in food and feed safety. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015;55(7):1026-34. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2013.769933. PMID: 25191830.

- Berners-Lee M. How Bad are Bananas; the Carbon Footprint of Everything. London: Profile Books; 2010.

- Bucur P, Hofmann M, Menhadji A, Abedi G, Okhunov Z, Rinehart J, Landman J. Comparison of Pneumoperitoneum Stability Between a Valveless Trocar System and Conventional Insufflation: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Urology. 2016 Aug;94:274-80. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.04.022. Epub 2016 Apr 27. PMID: 27130263.

- Cramer, J. (2014). Milieu: Elementaire Deeltjes: 16.

- Costa D, Quinteiro P, Dias AC. A systematic review of life cycle sustainability assessment: Current state, methodological challenges, and implementation issues. Sci Total Environ. 2019 Oct 10;686:774-787. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.435. Epub 2019 May 30. PMID: 31195285.

- Diaz SE, Lee YF, Bastawrous AL, Shih IF, Lee SH, Li Y, Cleary RK. Comparison of health-care utilization and expenditures for minimally invasive vs. open colectomy for benign disease. Surg Endosc. 2022 Oct;36(10):7250-7258. doi: 10.1007/s00464-022-09097-x. Epub 2022 Feb 22. PMID: 35194661; PMCID: PMC9485164.

- Drew J, Christie SD, Tyedmers P, Smith-Forrester J, Rainham D. Operating in a Climate Crisis: A State-of-the-Science Review of Life Cycle Assessment within Surgical and Anesthetic Care. Environ Health Perspect. 2021 Jul;129(7):76001. doi: 10.1289/EHP8666. Epub 2021 Jul 12. PMID: 34251875; PMCID: PMC8274692.

- EFSA, 2010. European Food Safety Authority; Application of systematic review methodology to food and feed safety assessments to support decision making. EFSA Journal 2010; 8(6):1637. [90 pp.]. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1637. Available online: www.efsa.europa.eu

- Elferink S, Kremer J, Steemers R. Uitstootcijfers geven grip op verduurzaming. Passende zorg bespaart CO2. Medisch Contact. 2023 feb.

- George AK, Wimhofer R, Viola KV, Pernegger M, Costamoling W, Kavoussi LR, Loidl W. Utilization of a novel valveless trocar system during robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. World J Urol. 2015 Nov;33(11):1695-9. doi: 10.1007/s00345-015-1521-8. Epub 2015 Mar 1. PMID: 25725807.

- Green Deal, 2022. C-238 Green Deal 3.0: Samen werken aan duurzame zorg. Gepubliceerd op 04 november 2022. Link: https://www.greendeals.nl/green-deals/green-deal-samen-werken-aan-duurzame-zorg

- Groene OK, 2021. Landelijk Netwerk Groene OK. Meerjarenplan Landelijk Netwerk de Groene OK 2022 - 2025. Link: https://degroeneok.nl/over-ons/over-de-groene-ok/

- Hanemaaijer, A., Delahaye, R., Hoekstra, R., Ganzevles, J., & Lijzen, J. (2018). Circulaire economie: wat we willen weten en kunnen meten: Systeem en nulmeting voor monitoring van de voortgang van de circulaire economie in Nederland.

- Herati AS, Atalla MA, Rais-Bahrami S, Andonian S, Vira MA, Kavoussi LR. A new valve-less trocar for urologic laparoscopy: initial evaluation. J Endourol. 2009 Sep;23(9):1535-9. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.0376. PMID: 19694520.

- Huijbregts, M. A., Steinmann, Z. J., Elshout, P. M., Stam, G., Verones, F., Vieira, M., ... & van Zelm, R. (2017). ReCiPe2016: a harmonised life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 22(2), 138-147.

- Huijbregts MAJ, Steinmann ZJN, Elshout PMF, Stam G, Verones F, Vieira MDMManagement Duurzame Melkveehouderij, Hollander A, Van Zelm R, 2016. ReCiPe2016: A harmonized life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. RIVM Rapport 2016-0104. Bilthoven, The Netherlands.

- Laudicella M, Walsh B, Munasinghe A, Faiz O. Impact of laparoscopic versus open surgery on hospital costs for colon cancer: a population-based retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016 Nov 3;6(11):e012977. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012977. PMID: 27810978; PMCID: PMC5128901.

- Luketina RR, Knauer M, Köhler G, Koch OO, Strasser K, Egger M, Emmanuel K. Comparison of a standard CO? pressure pneumoperitoneum insufflator versus AirSeal: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014 Jun 20;15:239. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-239. PMID: 24950720; PMCID: PMC4078359.

- MinisterieIenW, beleidstekst sectorplan LAP3, tweede wijziging (geldig vanaf 2 maart 2021). https://lap3.nl/sectorplannen/sectorplannen/gezondheid/

- Muaddi H, Hafid ME, Choi WJ, Lillie E, de Mestral C, Nathens A, Stukel TA, Karanicolas PJ. Clinical Outcomes of Robotic Surgery Compared to Conventional Surgical Approaches (Laparoscopic or Open): A Systematic Overview of Reviews. Ann Surg. 2021 Mar 1;273(3):467-473. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003915. PMID: 32398482.

- Morgan RL, Thayer KA, Bero L, Bruce N, Falck-Ytter Y, Ghersi D, Guyatt G, Hooijmans C, Langendam M, Mandrioli D, Mustafa RA, Rehfuess EA, Rooney AA, Shea B, Silbergeld EK, Sutton P, Wolfe MS, Woodruff TJ, Verbeek JH, Holloway AC, Santesso N, Schünemann HJ. GRADE: Assessing the quality of evidence in environmental and occupational health. Environ Int. 2016 Jul-Aug;92-93:611-6. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.01.004. Epub 2016 Jan 27. PMID: 26827182; PMCID: PMC4902742.

- Morgan RL, Beverly B, Ghersi D, Schünemann HJ, Rooney AA, Whaley P, Zhu YG, Thayer KA; GRADE Working Group. GRADE guidelines for environmental and occupational health: A new series of articles in Environment International. Environ Int. 2019 Jul;128:11-12. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.04.016. Epub 2019 Apr 24. PMID: 31029974; PMCID: PMC6737525.

- Mandrioli D, Silbergeld EK. Evidence from Toxicology: The Most Essential Science for Prevention. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 Jan;124(1):6-11. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1509880. Epub 2015 Jun 19. PMID: 26091173; PMCID: PMC4710610.

- NVvH, 2023. Leidraad Duurzaamheid in richtlijnen - Toevoegen van duurzaamheidsaspecten in richtlijnontwikkeling. Nog niet geautoriseerd: Commentaarfase, mei 2023.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021 Jun;134:178-189. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.001. Epub 2021 Mar 29. PMID: 33789819.

- Potting, J., Hekkert, M. P., Worrell, E., & Hanemaaijer, A. (2016). Circulaire economie: Innovatie meten in de keten.

- Power NE, Silberstein JL, Ghoneim TP, Guillonneau B, Touijer KA. Environmental impact of minimally invasive surgery in the United States: an estimate of the carbon dioxide footprint. J Endourol. 2012 Dec;26(12):1639-44. doi: 10.1089/end.2012.0298. Epub 2012 Oct 16. PMID: 22845049; PMCID: PMC3521130.

- Reike, D., Vermeulen, W. J., & Witjes, S. (2018). The circular economy: new or refurbished as CE 3.0?exploring controversies in the conceptualization of the circular economy through a focus on history and resource value retention options. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 135, 246-264.

- Sroussi J, Elies A, Rigouzzo A, Louvet N, Mezzadri M, Fazel A, Benifla JL. Low pressure gynecological laparoscopy (7mmHg) with AirSeal® System versus a standard insufflation (15mmHg): A pilot study in 60 patients. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2017 Feb;46(2):155-158. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2016.09.003. Epub 2017 Jan 30. PMID: 28403972.

- The Carbon Trust (2018) Carbon Footprinting. https://www.carbontrust.com/resources/carbon-footprinting-guide

- Thiel CL, Eckelman M, Guido R, Huddleston M, Landis AE, Sherman J, Shrake SO, Copley-Woods N, Bilec MM. Environmental impacts of surgical procedures: life cycle assessment of hysterectomy in the United States. Environ Sci Technol. 2015 Feb 3;49(3):1779-86. doi: 10.1021/es504719g. Epub 2015 Jan 14. PMID: 25517602; PMCID: PMC4319686.

- Tummers FHMP, Hoebink J, Driessen SRC, Jansen FW, Twijnstra ARH. Decline in surgeon volume after successful implementation of advanced laparoscopic surgery in gynecology: An undesired side effect? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021 Nov;100(11):2082-2090.

- Weidema B.P. (1997). Guidelines for Critical Review of Product LCA. SPOLD, Brussels, 14. https://lca-net.com/files/critical_review.pdf

- Woods DL, McAndrew T, Nevadunsky N, Hou JY, Goldberg G, Yi-Shin Kuo D, Isani S. Carbon footprint of robotically-assisted laparoscopy, laparoscopy and laparotomy: a comparison. Int J Med Robot. 2015 Dec;11(4):406-12. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1640. Epub 2015 Feb 22. PMID: 25708320.

- WHO, 2021. World Health Organization. Fact sheet: Climate change and health. Accessed at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health. 30 October 2021.

- Woodruff TJ, Sutton P. The Navigation Guide systematic review methodology: a rigorous and transparent method for translating environmental health science into better health outcomes. Environ Health Perspect. 2014 Oct;122(10):1007-14. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307175. Epub 2014 Jun 25. PMID: 24968373; PMCID: PMC4181919.

- Zumsteg JM, Cooper JS, Noon MS. Systematic Review Checklist: A Standardized Technique for Assessing and Reporting Reviews of Life Cycle Assessment Data. J Ind Ecol. 2012 Apr;16(Suppl 1):S12-S21. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00476.x. PMID: 26069437; PMCID: PMC4461004.

Evidence tabellen

Appendix 1. Evidence table for LCA studies

1Goals and scope: ‘Phase of life cycle assessment in which the aim of the study, and in relation to that, the breadth and depth of the study is established’

2Functional unit: Quantified description of the function of a product or process that serves as the reference basis for all calculations regarding impact assessment.

Appendix 2. Critical appraisal of LCAs (based on Drew, 2021)

Drew (2021) developed a critical appraisal pro forma, based on Weidema’s guidelines for critical review of LCA (Weidema, 1997). This scoring system consists of 16 appraisal criteria, which are divided between the different phases of an LCA. It addresses a range of study quality indicators, such as internal validity, external validity, consistency, transparency, and bias. The percentage score provides an indication of the overall study quality. A higher score indicates a higher overall study quality. The points that can be obtained are displayed in the column labeled "appraisal criteria".

|

Appraisal criteria |

Indicator(s) |

Key effect modifiers |

Power (2012) |

Thiel (2015) |

Woods (2015) |

|

Phase 1: Goal & Scope (13 points) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Study goal is clearly stated, including the study's rationale (1), intended application (1), and intended audience (1) |

Transparency |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

|

Lifecycle assessment method is clearly stated (1) |

Transparency |

Process-based life-cycle assessment, which is well suited to product-level analysis, may underestimate environmental impacts (i.e. from truncation error); economic input-output lifecycle assessment (EIO-LCA), which uses aggregate data and is well-suited to sector-level analysis, may overestimate environmental impacts |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Functional unit is clearly defined and measurable (1), justified (1), and consistent with the study's intended application (1) |

Consistency |

0 |

3 |

0 |

|

|

The system to be studied is adequately described with clearly stated system boundaries (1), lifecycle stages (1), and appropriate justification of any omitted stages (1) |

Transparency; Bias |

Assessments with narrow system boundaries that exclude a number of lifecycle stages are prone to underestimating life-cycle environmental impacts |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

The system covers production (1), use/reuse (1) and disposal (1) of materials and energy (half mark if only for energy and vice versa) |

Internal Validity, Completeness |

|

2 |

3 |

2 |

|

Phase 2: Inventory analysis (7 points) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The data collection process is clearly explained, including the source(s) of foreground material weights and energy values (1); the source(s) of reference data (e.g. inventory database; 1); and what data are included (e.g. production and disposal of unit processes; 1) |

Transparency, Internal Validity |

|

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

Representativeness of the data is discussed (1), differences in electricity generating mix are accounted for (1), and the potential significance of exclusions or assumptions is addressed (1) |

Internal validity; External validity |

|

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

Allocation procedures, where necessary, are described and appropriately justified (1; mark given if no allocation used) |

Transparency; Bias |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Phase 3: Impact assessment (6 points) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Impact categories (1), characterization method (1), and software used (1) are documented transparently |

Transparency |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Results are clearly reported in the context of the functional unit (1) (0.5 if graphically, 0 if only normalized results reported) |

Consistency; Transparency |

|

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

A contribution analysis is performed and clearly reported (1), and hotspots are identified (1) |

2 |

2 |

2 |

||

|

Phase 4: Interpretation (9 points) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conclusions are consistent with the goal and scope (1) and supported by the impact assessment results (1) |

Internal validity; Consistency |

|

0 |

2 |

2 |

|

Results are contextualized through the use of sensitivity analysis (1) and uncertainty analysis (1) |

Internal validity |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

Limitations are adequately discussed (1), and the potential impact of omissions or assumptions on the study's outcomes are described (1) |

Bias |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

The assessment has been critically appraised (i.e. peer review if journal article or independent, external critical review if report/thesis; 1) |

Bias |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Source(s) of funding and any potential conflict(s) of interest are disclosed (1), and are unlikely to be a source of bias (1) |

Bias |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Total (/35) |

19 |

28 |

20 |

||

|

Percentage score |

54% |

80% |

57% |

Module 1: Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Terra 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong intervention, wrong study design |

|

Alshowaikh 2021 |

Wrong outcome |

|

McKenzie 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population |

|

Scarcella 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong study design |

|

Sugita 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong study design |

|

Hirano 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Kagiyama 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong study design |

|

Bakr 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong study design |

|

Wang 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population |

|

AlJamal 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Bertolo 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Sun 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Mahmud 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population |

|

Scott 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong study design |

|

Leitsmann 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong study design |

|

Simianu 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Lenfant 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Hanaoka 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Tampio 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population |

|

Patel 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population |

|

Sobel 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Fulla 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Kim 2020 |

Wrong outcome, foreign language, wrong study design |

|

Rassweiler 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong intervention |

|

Aggarwal 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Khoraki 2020 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Grewal 2020 |

Wrong population, wrong intervention |

|

Chen 2019 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong study design |

|

Pennington 2019 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong intervention |

|

Akpinar 2019 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Weidert 2019 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong intervention, wrong study design |

|

Rosenfeld 2018 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Han 2019 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Abdelmoaty 2019 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Sardari Nia 2019 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong study design |

|

Schuetze 2019 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong study design |

|

Laviana 2018 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Gao 2018 |

Wrong population, wrong intervention |

|

Hahn 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Patti 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Manning 2018 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Moukarzel 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Unger 2017 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Pellegrino 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Kaminski 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong intervention |

|

Agzarian 2016 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population |

|

Pellegrino 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Hollis 2016 |

Wrong outcome |

|

van der Steen-Banasik 2016 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Manjila 2016 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong intervention |

|

Schwein 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong intervention, wrong study design |

|

El Hachem 2016 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Lee 2016 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population |

|

Rault 2016 |

Wrong population, wrong intervention |

|

Herling 2016 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Shrikhande 2015 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Ludwig 2015 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Suh 2016 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Park 2015 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison, wrong population |

|

Weinberg 2015 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Rossi 2015 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Park 2015 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Stark 2015 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong study design |

|

Gupta 2014 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Liu 2014 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Angioli 2015 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Asimakopoulos 2014 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Sumila 2014 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Lukens 2014 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Tapper 2014 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Datino 2014 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Hart 2013 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Liang 2014 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Barzilay 2014 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Koutlidis 2014 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Ozyigit 2014 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong intervention |

|

Chesson 2013 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Lee 2013 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Grandhi 2012 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong intervention |

|

Fleming 2012 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Ferguson 2012 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Liu 2012 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Hyde 2012 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong intervention |

|

Guillotreau 2012 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Behera 2012 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Norbash 2011 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Thakur 2012 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Camps 2011 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Rebuck 2011 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Barnett 2010 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Bondiau 2010 |

Wrong outcome, foreign language, wrong intervention |

|

Judd 2010 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Holtz 2010 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Riga 2010 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Smith 2010 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Siu 2010 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Cosentino 2009 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Schmidt 2009 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong population |

|

Gibbs 2009 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison, wrong population |

|

Hyams 2008 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Schabowsky 2008 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison, wrong population |

|

Steinberg 2008 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Marecik 2008 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design, wrong population |

|

Nakadi 2006 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Van Brakel2004 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design, wrong population |

|

Balaji 2004 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Fuchs 2002 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Chiu 2000 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Puri 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Darwood 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong population |

|

Lin 2021 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Lemos 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population |

|

Mun 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Liu 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population |

|

Gerull 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population |

|

Buschbaum 2015 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Pizzighella 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Ross 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Yun 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population |

|

Petro 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population |

|

Perile 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong study design |

|

Kim 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong study design, wrong population |

|

Peak 2021 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Ishii 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong study design |

|

Rodin 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Belline 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Law 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Emile 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Cotter 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Rose 2019 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Bayne 2019 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison, wrong study design |

|

Benabid 2019 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong population |

|

Ciocirlan 2019 |

Wrong intervention, wrong study design |

|

Vercellini 2018 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong study design |

|

Raheem 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong comparison, wrong population |

|

Sanguedolce 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Scheurs 2018 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong study design, wrong population |

|

Prins 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong intervention |

|

Rogers 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Johnson 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Backelandt 2016 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Zaman 2016 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Mathuriya 2016 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong population |

|

Chi 2015 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population |

|

White 2015 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Biehn Stewart 2014 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Smorgick 2014 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Woelk 2014 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Pai 2014 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Vuckovic 2013 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Geraerts 2013 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Weisz 2013 |

Wrong outcome, wrong pupulation |

|

Eldefrawy 2013 |

Wrong study design, wrong intervention |

|

Nayeemuddin 2013 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Ahmed 2012 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Leitao 2012 |

Wrong study design |

|

Nakamura 2012 |

Wrong population, wrong study design |

|

Michel 2012 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Linte 2011 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong population |

|

Cheetham 2010 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Pow-Sang 2007 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Lund 2004 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Perrier 2002 |

Foreign language |

|

Hoque 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong study design |

|

Sharma 2021 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Jia 2021 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Marlicz 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Shetty 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison, wrong population |

|

Stroberg 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Ji 2020 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Merola 2020 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Garbin 2019 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Lin 2019 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison, wrong population |

|

Kim 2018 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Takizawa 2018 |

Wrong outcome, wrong study design |

|

Redondo 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Mateen 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Cheng 2017 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Singh 2013 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Gomes 2011 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Nct 2018 |

Registered trial, wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Nct 2019 |

Registered trial, wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Nct 2009 |

Registered trial, wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Nct 2016 |

Registered trial, wrong outcome |

|

Nct 2013 |

Registered trial, wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Actrn 2021 |

Registered trial, wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Nct 2017 |

Registered trial, wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Nct 2016 |

Registered trial, wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Jang 2019 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Lu 2015 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention |

|

Mukherjee 2009 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong study design, wrong population |

|

Borwn-Clerk 2008 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong study design, wrong population |

|

Fischer 2007 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong study design |

|

Ro 2005 |

Wrong outcome, wrong population, wrong study design |

|

Lee 2005 |

Wrong outcome |

|

Maassen 2004 |

Wrong outcome, wrong intervention, wrong population |

|

Nebot 2003 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison |

|

Luketich 2002 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison, wrong population |

|

Li 2000 |

Wrong outcome, wrong comparison, wrong population |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 07-02-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 08-01-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze Leidraad Duurzaamheid (bestaande uit Deel A - Methodologische Handreiking en Deel B - Inhoudelijke duurzaamheidsmodules) werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Doel en doelgroep

Het doel van dit project is om algemene handvatten te ontwikkelen voor het opnemen van duurzaamheid met betrekking tot het milieu bij revisie van bestaande of ontwikkeling van nieuwe landelijke richtlijnen in de snijdende disciplines. Met deze Methodologische Handreiking wil deze werkgroep toekomstige richtlijncommissies van professionele standaarden (e.g. leidraden, richtlijnen, modules) kaders bieden om duurzaamheid op de juiste wijze mee te nemen.

Duurzaamheid is een breed begrip, en de verschillende betekenissen kunnen een ander doel hebben. Zo is duurzame ontwikkeling een ontwikkeling die tegemoetkomt aan de levensbehoeften van de huidige generatie, zonder die van toekomstige generaties tekort te doen. Daaronder worden zowel economische, sociale als leefomgevingsbehoeften geschaard (CBS, 2023). De werkgroep focust zich in deze Leidraad voornamelijk op duurzaamheid met betrekking tot het milieu, waarin de nadruk ligt op gezond milieu en leefomgeving. Dat wil zeggen, zo min mogelijk uitstoot van broeikasgassen, geen uitputting van grondstoffen, geen vervuiling en het in stand houden van ecosystemen. Aanbevelingen die zijn geformuleerd om duurzaamheid mee te nemen in richtlijnontwikkeling, richten zich specifiek op het verbeteren van de milieu-impact, de (negatieve) invloed die het menselijk handelen heeft op de natuurlijke omgeving en op de ecosystemen van de aarde.

Het doel van deze Leidraad is richtlijncommissies en -adviseurs op een uniforme wijze te ondersteunen in het implementeren van duurzaamheid in medisch specialistische richtlijnen. Deze Leidraad is uiteraard een eerste stap en verkenning op dit gebied, de werkgroep acht dat evaluatie en implementatie zal worden bewaakt.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de Methodologische Handreiking en bijbehorende richtlijnmodules is in 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten op operatiekamers.

Werkgroep

- Dhr. prof. dr. F.W. Jansen (voorzitter), gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Mevr. prof. dr. N.D. Bouvy, chirurg, NVVH

- Mevr. drs. I.R. van den Berg, uroloog, NVU

- Dhr. drs. P.W. van Egmond, orthopedisch chirurg, NOV

- Dhr. dr. R.J.H. Ensink, KNO arts, NVKNO

- Mevr. drs. N. de Haas, plastische (hand-)chirurg, NVPC (vanaf januari 2022)

- Mevr. dr. A. Kwee, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Mevr. dr. N.C. Naus-Postema, oogarts, NOG

- Mevr. drs. K.E. van Nieuwenhuizen, arts-onderzoeker, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum

- Dhr. drs. N.A. Noordzij, plastisch chirurg, NVPC (tot december 2021)

- Mevr. drs. C.S. Sie, anesthesioloog, NVA

- Dhr. dr. E.S. Smits, plastisch chirurg, NVPC

- Mevr. dr. K.E. Veldkamp, arts-microbioloog, NVMM

- Mevr. drs. F.J.M. Westerlaken, deskundige Infectiepreventie, VHIG

Meelezers in klankbordgroep