Reusables versus disposables

Uitgangsvraag

2.1 Hoe kunnen reusables en disposables op een operatiecomplex op de meest duurzame manier worden gebruikt?

2.2 Hoe kunnen specifieke reusable en disposable medische instrumenten op een operatiecomplex op de meest duurzame manier worden gebruikt?

Zie een schematisch overzicht van de module in ‘Samenvatting’.

Aanbeveling

Gebruik bij voorkeur reusables, omdat disposables een grotere (negatieve) impact hebben op het milieu (R4-Reuse).

- Beoordeel kritisch of het gebruik van een product daadwerkelijk nodig is (R1-Refuse).

- Indien disposables toch noodzakelijk zijn bij de operatie, probeer dan het gebruik te minimaliseren (R2-Reduce).

Om de milieu-impact van reusables te verlagen:

- Optimaliseer het reiniging-, desinfectie- en sterilisatieproces

(bijv. door het gebruik van duurzame energie, energiezuinige apparatuur. - Beoordeel of sterilisatie noodzakelijk is naast reiniging en desinfectie. Raadpleeg hiervoor de SRI richtlijnen.

- Optimaliseer het transport (bijv. door een meer duurzame manier van transport, verkorten van de transport afstand).

- Geef de voorkeur aan reusables met de langste levensduur, omdat dit de laagste (negatieve) impact heeft op het milieu.

Neem duurzaamheid mee in het (her)ontwerp van producten, instrumenten en apparatuur (R3-Redesign).

- Wijs de industrie op het belang van het aanbieden van duurzame medische hulpmiddelen.

- Neem afvalverwerking mee in het herontwerp (bijv. door het gebruik van minder soorten materialen, duidelijke aanduiding afvalscheiding, stimuleren van circulariteit).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de milieu-impact van disposables en reusables die worden gebruikt op operatiekamers. Twintig studies zijn gevonden (PICO1 n=9; PICO2 n=11). Hiervan zijn achttien studies een LCA, één studie is een review (Drew, 2021) en één studie behelst een observationeel onderzoek (Namburar, 2022). De studies vergelijken verschillende medische hulpmiddelen, bijvoorbeeld: naaldencontainers, operatiejassen, isolatiejassen, anesthesie medicatietrays, scopes, specula, anesthesieapparatuur, bloeddrukbanden en chirurgisch instrumentarium. Omdat de studies van beide PICO’s medische hulpmiddelen bevatten, worden deze als één groep beschouwd in de overwegingen en aanbevelingen en zullen de PICO’s niet afhankelijk worden behandeld.

De bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten ‘climate change’ en ‘waste’ komt uit op laag. De bewijskracht voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten komt uit ook uit op laag. Op basis van de GRADE beoordeling van de literatuur kunnen geen sterke conclusies geformuleerd worden over de precieze mate van milieu-impact van reusables en disposables. Echter, ondanks de methodologische verschillen tussen de LCA’s, wijzen de resultaten wel dezelfde richting op. De resultaten van deze LCA’s worden ondersteunt door twee CE Delft studies die zijn uitgevoerd voor de UMC Utrecht (CE Delft, 2022a; CE Delft, 2022b). Gezien deze consequente richting, geïdentificeerde hotspots en de urgentie om de milieu-impact te verminderen, beschouwt de werkgroep dit als afdoende ondersteuning om sterke aanbevelingen te formuleren. De werkgroep hoopt hiermee bewustwording te creëren bij zorgverleners en zo concreet mogelijk handvatten te bieden.

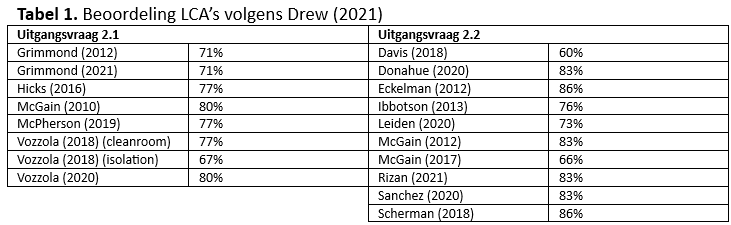

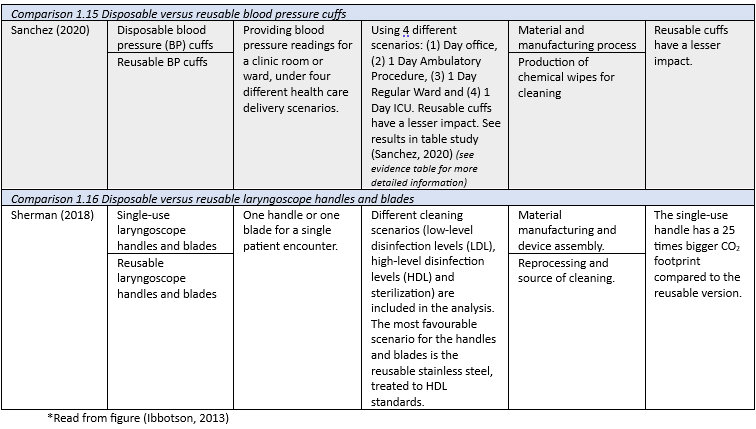

De LCA’s (n=18) zijn kritisch beoordeeld op basis van de beoordeling volgens Drew (2021). De kwaliteit van de studies wordt hiermee beoordeeld op basis van de methodologie van een LCA. Dit scoresysteem bestaat uit 16 beoordelingscriteria, die zijn verdeeld over de verschillende fasen van een LCA. Het behandelt een reeks indicatoren voor studiekwaliteit, zoals interne validiteit, externe validiteit, consistentie, transparantie en bias. De procentuele score geeft een indicatie van de algehele studiekwaliteit. Een hogere score duidt op een hogere algehele studiekwaliteit (zie bijlage 2). Een beknopt overzicht van de scores staat weergegeven in tabel 1.

Indien disposables en reusables met elkaar worden vergeleken, moet de gehele levenscyclus en levensduur van de producten in acht worden genomen. Indien een reusable bijvoorbeeld 75 keer kan worden hergebruikt, wordt dit vergeleken met 75 disposable producten voor eenmalig gebruikt. Hierbij is dus niet de gehele levensduur van de reusable variant meegenomen, wat leidt tot een ongelijke vergelijking. Daarnaast zal men zich bewust moeten zijn dat in de studie van Leiden (2020) de reusable instrument set uit veel meer instrumenten bestaat dan de disposable set. In andere LCA’s wordt aangetoond dat bij meermalig gebruik van de reusable de negatieve milieu-impact afneemt, in vergelijking met de disposable variant (Drew, 2021; Grimmond, 2012; Grimmond, 2021; Hicks, 2016; McGain, 2010; McPherson, 2019; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2020; Donahue, 2020; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018). Deze 14 LCA’s impliceren dat het gebruik van reusables een lagere milieu-impact heeft in vergelijking tot het gebruik van disposables.

McGain (2017) vergeleek reusable en disposable anesthesie apparatuur en concludeerde dat de milieu-impact van hetzelfde type apparatuur (bijvoorbeeld reusable) kan variëren tussen verschillende continenten. Waar de disposables een lagere milieu-impact lijken te hebben in Australië, suggereren de resultaten dat de impact voor reusables lager zijn in de Verenigde Staten (VS), het Verenigd Koninkrijk (VK) en in Europa. Dit komt door het verschil in energiemix. Er zijn verschillende primaire energiebronnen, waaruit secundaire energie voor direct gebruik (zoals elektriciteit) wordt geproduceerd. Steenkool als energiebron voor de energiemix, zoals in Australië, leidt tot een grotere milieu-impact voor de reusables in vergelijking tot het gebruik van een andere energiemix (zoals bijv. energiebronnen van wind- en zonne-energie). De ‘hotspot’ in de levenscyclus van disposables is het productieproces.

Geïdentificeerde hotspots uit de studies worden geëvalueerd middels het ‘10R model circulariteit’ (zie Figuur 1, gebaseerd op Cramer, 2014; Hanemaaijer; 2018; Potting, 2016; Reike, 2018). Deze R-ladder laat zien dat de hoogste prioriteit om duurzaam te werken ‘refuse’ is, oftewel, niet gebruiken. Hoe lager het grondstofgebruik, des te hoger op de R-ladder en hoe dichter je bij circulair werken bent.

Figuur 1. Prioriteitsvolgorde circulariteit strategieën

Refuse (R1) en Reduce (R2)

De werkgroep adviseert om kritisch te beoordelen of het gebruik van een product daadwerkelijk nodig is (R1-Refuse). Kijk hierbij kritisch of de gehele inhoud van steriele (instrument) netten en operatietrays daadwerkelijk gebruikt moeten worden en verminder de inhoud indien mogelijk. Aangezien LCA’s laten zien dat het gebruik van disposables een grote negatieve milieu-impact heeft (met als ‘hotspot’ het productieproces), adviseert de werkgroep daarnaast om zoveel mogelijk met reusables te werken en disposables niet te gebruiken (R1-Refuse).

Indien het gebruik van disposables noodzakelijk lijkt te zijn, wees dan bewust van de hogere impact en probeer de hoeveelheid zo laag mogelijk te houden (R2-Reduce). Bepaal van tevoren de mate van inzet van een product of instrument. Bijvoorbeeld of een disposable multifunctioneel instrument (coaguleren en snijden) de voorkeur heeft of dat een reusable bipolaire schaar kan worden gebruikt. Dit scheelt zowel kosten als een minder negatieve milieu-impact. Daarnaast draagt een kleinere verpakking bij aan verlaging van de milieu-impact door minder materiaalgebruik. Indien er minder opslagruimte nodig is, kunnen met minder reisbewegingen ook hetzelfde aantal producten worden getransporteerd.

Redesign (R3)

Duurzaamheid zal als standaard moeten worden meegenomen in het (her)ontwerp van producten en instrumenten. De industrie zal leidend moeten zijn, door het aanbieden van producten met een langere levensduur. Hierbij moet worden samengewerkt om tot kwalitatief goede en duurzame producten te komen. De zorgverlener zal hierbij leiding moeten nemen en de industrie moeten wijzen op het belang van het aanbieden van duurzame medische hulpmiddelen.

In het ontwerp van disposables liggen ook kansen om de milieu-impact te beperken. Rizan (2021) vergelijkt hybride instrumentarium (deels reusable en deels disposable) met geheel disposable, waarbij het hybride instrumentarium milieuvriendelijker blijkt te zijn. Indien het niet mogelijk is om een chirurgisch instrument geheel reusable te maken en dezelfde functie te laten uitoefenen (bijvoorbeeld vanwege het niet kunnen reinigen en steriliseren door complex ontwerp), zou de ontwikkeling tot een hybride instrument de milieu-impact kunnen verlagen. Hier ligt de uitdaging voor ontwerpers om reusables of hybride instrumenten te ontwikkelen met dezelfde functie als de huidige disposables. Indien het onderdeel weer hergebruikt kan worden, leidt dit uiteindelijk tot minder grondstofverbruik en een lagere impact op het milieu.

Daarnaast zal de afvalverwerkingsfase moeten worden meegenomen in het ontwerp. Een product moet gemakkelijk te demonteren zijn (indien het uit meerdere onderdelen bestaat) en het moet duidelijk zijn uit welke materialen het bestaat, zodat afvalscheiding wordt vereenvoudigd.

Verder zal bij ontwikkeling van nieuwe producten of herontwerp van bestaande producten infectiepreventie moeten worden meegenomen. Zoek hierbij de samenwerking met infectiepreventie voor een adequate risicoafweging waarbij de risico’s van een infectie/besmetting afgezet wordt tegen verduurzamingsmaatregelen.

Denk bij herontwerp ook aan een andere manier van het gebruik van instrumenten. Een standaard disposable hechting verwijder set wordt steriel verpakt en bestaat geheel uit disposable materialen. De vraag is of het nodig is om met een steriel set te werken, en of het disposable moet zijn. In overleg met de arbeidshygiënist of deskundige infectiepreventie is het mogelijk om alternatieven te exploreren.

Re-use (R4)

In de loop van de tijd is binnen de gezondheidszorg een wegwerpcultuur ontstaan en zijn de disposables niet meer weg te denken. Ook de grondstof schaarste zal op den duur problemen kunnen opleveren in de toeleveringsketen van disposables en daarnaast zal dit kunnen leiden tot een toename in kosten.

De meeste studies wijzen erop dat reusables een minder grote negatieve impact hebben op het milieu in vergelijking met disposables. Bij studies waar disposables een lagere milieu-impact hebben, hanteren de studies een andere energiemix dan wij in Europa hebben (Davis, 2018; McGain, 2017) of nemen ze niet de gehele levensduur van de reusables mee (Leiden, 2020; McGain, 2012). Deze laatste studies (Leiden, 2020; McGain, 2012) laten wel dezelfde hotspots zien als studies waarbij de reusables een lagere milieu-impact hebben (Drew, 2021; Grimmond, 2012; Grimmond, 2021; Hicks, 2016; McGain, 2010; McPherson, 2019; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2020; Donahue, 2020; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018), namelijk het productieproces van de disposables. Vanwege het productieproces, is de verwachting dat gebruik van disposables een grotere impact heeft op het milieu dan de reusables. Een ‘schone’ elektrische bron (bijvoorbeeld zonne- of windenergie) kan de impact van het productieproces verlagen (Grimmond, 2012; McPherson, 2019). De overstap van een CO2-intensief naar een minder CO2-intensief elektriciteitsnet resulteert in een reductie van CO2-uitstoot (Donahue, 2020). Ongeacht welk elektriciteitsnet wordt gebruikt, de CO2-uitstoot van reusables blijft lager in vergelijking met disposables.

Bij reusables geeft het reiniging en sterilisatieproces de grootste milieubelasting. Daarbij horen de volgende hotspots: energie en stoom voor autoclaven, transport, waterverbruik en de hoeveelheid instrumenten die tegelijkertijd worden gesteriliseerd (Donahue, 2020; Eckelman, 2012; Grimmond, 2012; Grimmond, 2021; McPherson, 2019). De werkgroep acht het belangrijk om nader dit te evalueren. In specifieke gevallen kan desinfectie voldoende zijn en hoeft er geen sterilisatie plaats te vinden. Desinfectie vraagt minder energie en is duurzamer. Hierin kan de Deskundige Steriele Medische Hulpmiddelen (DSMH) adviseren op basis van een risicoafweging. In de richtlijnen van het Samenwerkingsverband Richtlijnen Infectiepreventie (SRI) staat meer informatie over reiniging, desinfectie en sterilisatie van medische hulpmiddelen.

Eckelman (2012) vergelijkt het effect van alternatieve vervoerswijzen met spoorweg transport. Het effect van alternatieve vervoerswijzen (vervoer over de weg of door de lucht) ten opzichte van spoorweg transport is vrij klein voor reusables. Daarentegen leidt dit bij disposables tot een groot verschil ten opzichte van spoorweg transport, met name bij het vervoer door de lucht (sterke toename in CO2-uitstoot).

Daarnaast rijst de vraag of het mogelijk is om disposable instrumenten opnieuw te gebruiken. Indien de fabrikant aangeeft dat dit niet mogelijk is, wordt hergebruik in de praktijk nagenoeg niet uitgevoerd. Indien dit wel het geval is, dan is de fabrikant niet meer verantwoordelijk, maar de eindgebruiker is dat zelf. Dit weerhoudt eindgebruikers om toch te hergebruiken. Geadviseerd wordt om actief samenwerking op te zoeken met de industrie om de mogelijkheden te onderzoeken en in te zetten op optimalisatie van de wetgeving (Medical Device Regulation – MDR) met als doel de regels rondom hergebruik te verruimen.

Repair (R5), Refurbish (R6), Remanufacture (R7)

De factoren R5-Repair, R6-Refurbish en R7-Remanufacture hangen nauw met elkaar samen. Eckelman (2012) stelt dat verkorting van de levensduur van reusables direct effect heeft op de uitstoot van broeikasgassen. Het verlengen van de hergebruikcyclus van reusable laryngeal mask airways (LMA) van 10 naar 100 cycli leidt tot een daling van 58% in CO2-uitstoot. Voordat een product of apparaat wordt afgedankt, is het dus van belang om opnieuw te kijken of de levensduur verlengd kan worden. De werkgroep adviseert om het repareren of opknappen van producten standaard te overwegen.

Repurpose (R8), Recycling (R9), Recover (R10)

Indien een instrument of product niet meer gebruikt kan worden waarvoor het is bedoeld, kan worden gekeken naar een nieuw doeleinde (R8-Repurpose). Grimmond (2012) laat zien dat terugwinning van energie en materialen de milieu-impact van het productieproces kan verlagen (R9-Recycling en R10-Recover). Een voorbeeld is het inzamelen van gebruikte middelen met als doel om hoogwaardig gebruikte materialen terug te winnen (zoals bijvoorbeeld het inzamelen van staplers).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor de patiënt en zorgverlener is het van belang dat instrumenten en producten die worden gebruikt in de zorgverlening veilig en effectief zijn. Daarnaast heeft duurzaamheid van het product ook indirect een positief effect op de gezondheid van de mens. De werkgroep vindt het van belang om duurzaamheid naast andere overwegingen mee te nemen in de keuze tussen reusable en disposable producten.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Grimmond (2012) berekent een kostenbesparing van 19% bij het overstappen van disposables naar reusables. In de praktijk worden veelal op korte termijn beslissingen gemaakt wat betreft de keuze voor een instrument of product. Op de korte termijn is een disposable vaak goedkoper, echter een reusable zal initieel duurder zijn bij aanschaf maar door het hergebruik zal het zich in de meeste gevallen terugbetalen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De keuze voor reusables of disposables ligt bij de zorgverlener, wat wordt bepaald door veel verschillende factoren (bijvoorbeeld gebruiksgemak, patiëntvriendelijkheid veiligheid, effectiviteit). Kennisgebrek over de impact van disposables en reusables op het milieu zal een rol spelen in het maken van een beslissing. Het vergt bewustwording over de impact van de verschillende interventies en hun hotspots om duurzaamheid mee te kunnen laten wegen in een beslissing. De werkgroep voorziet geen grote barrières met betrekking tot aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Het is echter aan de Raad van Bestuur van ziekenhuizen om het verschil te maken door duurzame initiatieven te prioriteren.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Op dit moment is de bewijskracht van LCA’s laag tot zeer laag. Hoewel de literatuur heterogeen is en enkele methodologische beperkingen omvat, heeft de werkgroep een voorkeur voor het gebruik van reusables.

Gezien het feit dat de resultaten van de LCA’s consequent dezelfde richting op wijzen (i.e. hotspots duidelijk zijn), de urgentie om de milieu-impact te verminderen de positieve praktijk ervaring van de werkgroep met reusables, beschouwt de werkgroep dit als afdoende ondersteuning om sterke aanbevelingen te formuleren. Als op basis van de literatuurconclusies en overwegingen geen duidelijke voorkeur is, gebruik dan reusables.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De afgelopen decennia is er sprake van een toename in het aantal disposables in de klinische praktijk. Deze toename is te wijten aan de verschuiving van reusables naar disposables vanwege zorgen over steriliteit, gebruiksgemak, complexe apparatuur die niet goed schoon te maken is en het mogelijk falen van reusables (Siu, 2016). Omdat disposables maar eenmalig kunnen worden gebruikt, leidt dit tot hoge productiecijfers en relatief veel afval, wat een extra belasting op het milieu geeft. Het is echter onduidelijk welke impact het gebruik van reusables op het milieu heeft, in vergelijking met disposables. In deze module worden duurzaamheidsuitkomsten van disposables en reusables met elkaar vergeleken. Hierbij is onderscheidt gemaakt tussen algemene disposables/reusables en specifieke disposable/reusable medische instrumenten door twee deelvragen op te stellen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Given that all comparisons involve the assessment of reusable versus disposable medical devices, conclusions regarding the level of evidence of literature from sub question 2.1 and sub question 2.2 are presented in one overview.

1. Climate Change

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that reusables have less impact on climate change when compared to disposables in the operating room for patients who undergo surgery.

Sources: Grimmond, 2012; Grimmond, 2021; McPherson, 2019; Hicks, 2016; McGain, 2010; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2020; Davis, 2019; Donahue, 2020; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Leiden, 2020; McGain, 2012; McGain, 2017; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018 |

2. Waste

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that reusables decrease waste when compared to disposables in the operating room for patients who undergo surgery.

Sources: Grimmond, 2012; Grimmond, 2021; McPherson, 2019; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2020; Davis, 2018; McGain, 2017; Namburar, 2022 |

3. Acidification

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that reusables have less impact on acidification when compared to disposables in the operating room for patients who undergo surgery.

Sources: Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Leiden, 2020; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018 |

4. Eutrophication

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that reusables have less impact on eutrophication when compared to disposables in the operating room for patients who undergo surgery.

Sources: Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Leiden, 2020; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018 |

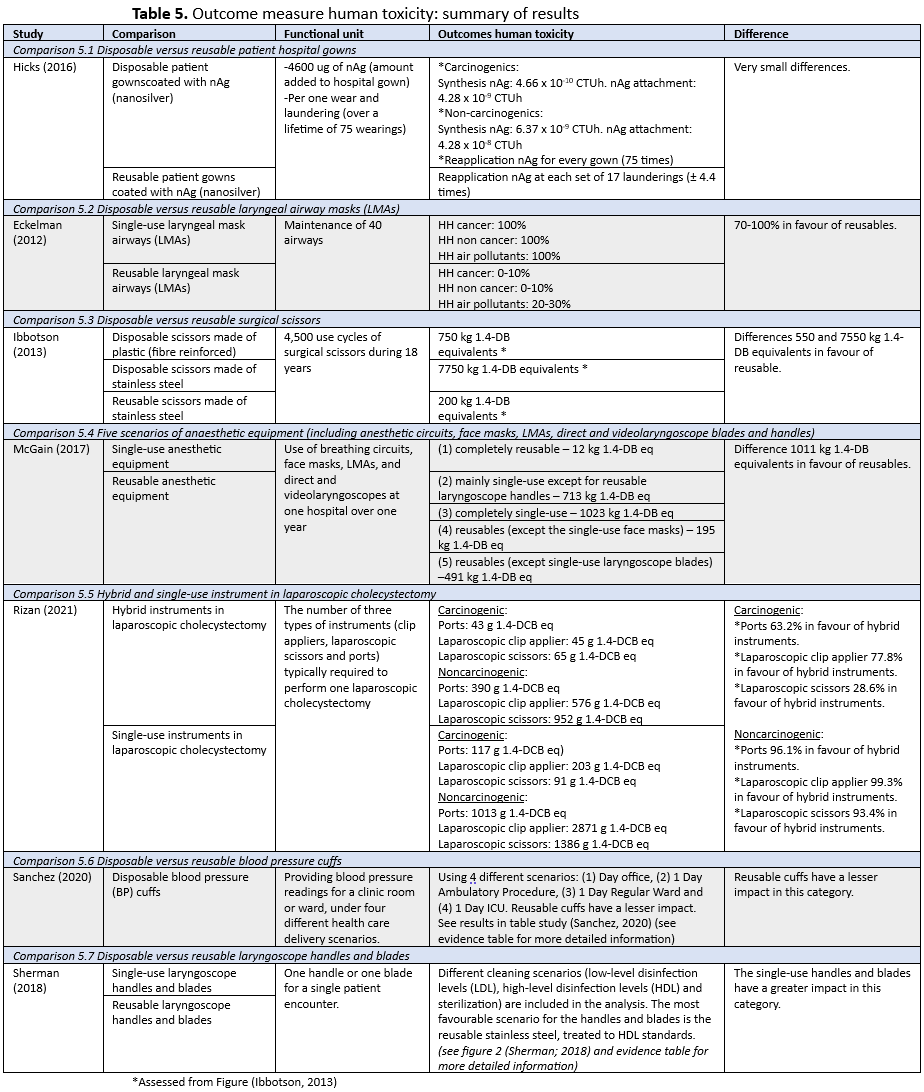

5. Human toxicity

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that reusables have less impact on human toxicity when compared to disposables in the operating room for patients who undergo surgery.

Sources: Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; McGain, 2017; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018 |

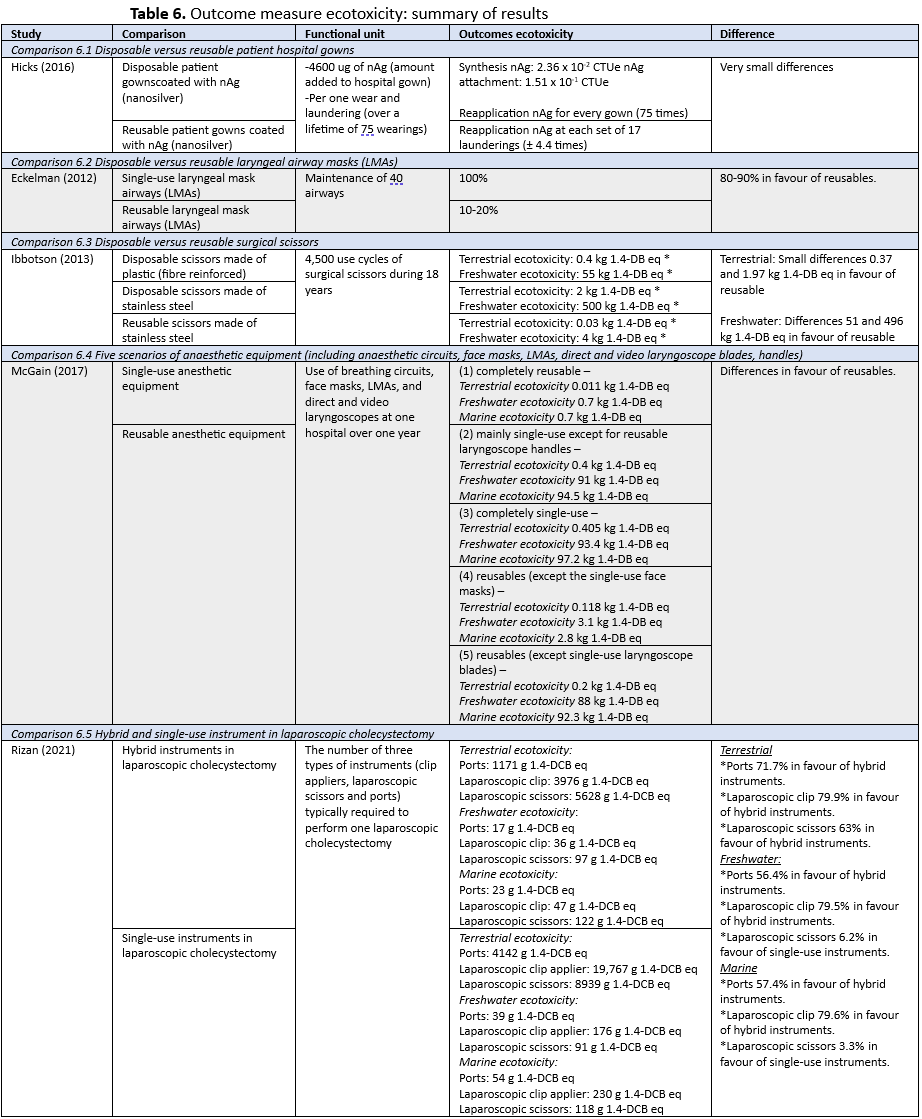

6. Ecotoxicity

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that reusables have less impact on ecotoxicity when compared to disposables in the operating room for patients who undergo surgery.

Sources: Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; McGain, 2017; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018 |

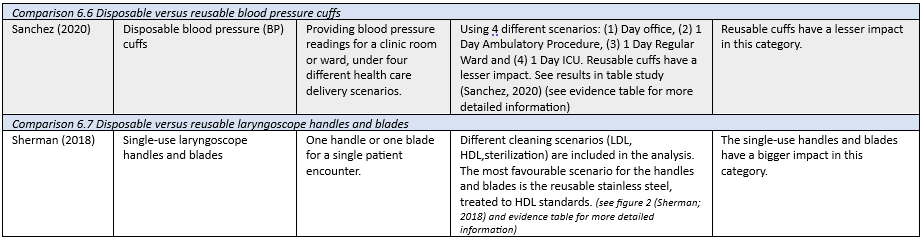

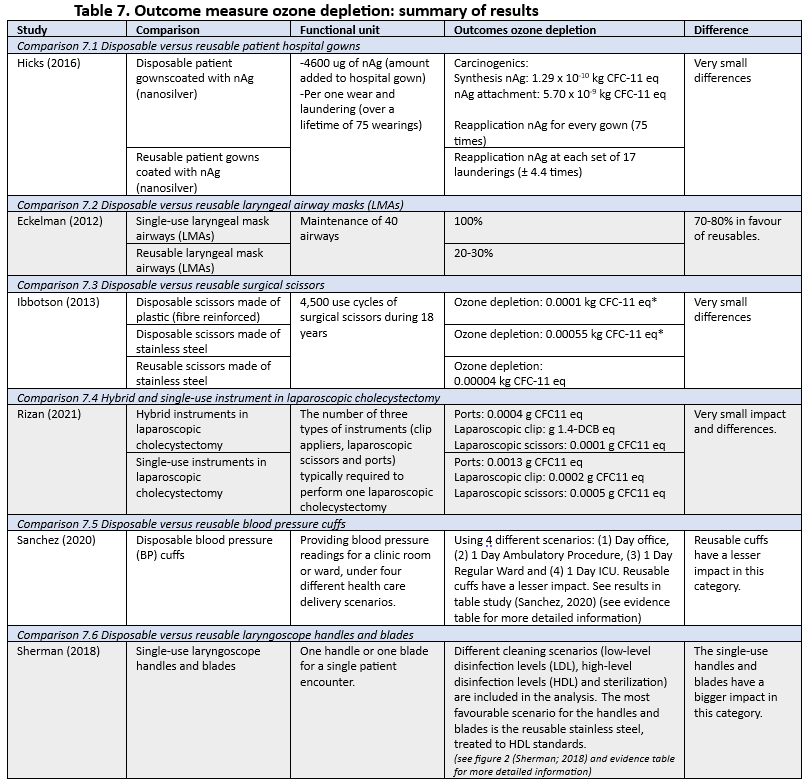

7. Ozone depletion

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that reusables have less impact on ozone depletion when compared to disposables in the operating room for patients who undergo surgery.

Sources: Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Summary of literature – Sub-question 2.1 reusables versus disposables

Description of studies

Drew (2021) describes a systematic review of life cycle assessments (LCAs) in anaesthetic and surgical care. It aims to summarize the state of LCA practice via review of literature assessing the environmental impact of related services, procedures, equipment and pharmaceuticals. The review was guided by using STARR-LCA, which is a PRISMA-based framework. Studies were included if they assessed the environmental impact(s) of (1) an operating room(s) using LCA, (2) a specific surgical procedure(s) using LCA or (3) equipment or pharmaceuticals used in surgical settings. In total 44 studies were included. Of these studies, one study examined the impact contributions from ORs generally, 10 studies from specific surgical procedures and 33 assessed the environmental impact from provision and use of surgical or anaesthetic equipment or pharmaceuticals. Eligible studies varied in terms of quality, completeness and risk of bias, with critical appraisal scores varying between 44% and 89%. Relevant outcome measures included climate change, waste, acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, ecotoxicity and ozone depletion.

Grimmond (2012) compared the environmental impact of a reusable sharps container system with a single-use one. A life cycle assessment (LCA) framework was used to assess the climate impact of the two different sharps container systems. The single use sharps containers (SSC) were evaluated for over a 12-month period prior to Northwestern Memorial Hospital's transition to a reusable-based system. The reusable sharps containers (RSC) (certified for 500 applications) were assessed over the following 12-month period, excluding the transition month from the analysis to avoid data overlap. Data was collected regarding the size, type, and number of reusable sharps containers used, as well as protocols with information about the changeout when the containers were full. Data was extracted from a variety of industry and government sources and combined with a Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)/LCA tool developed by the Waterman Group UK, which included all the energy dependent processes required for any needle collection system. The outcome measures were climate change and waste. A limitation was that this study is conducted in the USA with all processes related to 1 hospital, which might limit the generalizability.

Grimmond (2021) compared the global warming potential (GWP) of hospitals converting from single-use sharps containers (SSC) to reusable sharps containers (RSC) by using an attributional LCA model. The intervention was the conversion from SSC to RSC in 40 NHS hospitals in the United Kingdom. A 12-month period of usage of SSC was compared with a 12-month usage of RSC. The functional unit was total fill line litres (FLL) of sharps containers needed to dispose of sharps for a 1-year period. SSC and RSC usage details in 17 baseline hospitals immediately prior to 2018 were applied to the RSC usage details of the 40 trusts using RSC in 2019. The outcome measures were climate change and waste. A limitation could be that the results of SSC has been extrapolated from 17 hospitals to 40 and therefore the representativeness of data might not be accurate.

Hicks (2016) conducted an LCA to compare the environmental impact of reusable patient hospital gowns coated with nanoscale silver (nAg) product compared to the use of nAg-coated disposable gowns in a case study. First, the environmental impact of 4600 ug nAg was determined (the amount added to a hospital gown). Second, the life cycle impacts of nAg-enabled reusable hospital gowns per one wear are modelled and midpoint environmental data are compared. The outcome measures were climate change acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, ecotoxicity and ozone depletion. Limitations were that only one attachment and synthesis process was analyzed, the environmental impact of excess silver during synthesis and the silver lost was not explored, and that the comparisons of reusable and disposable gowns relied on prior work and utilizes only one impact category.

McGain (2010) modelled the financial and environmental costs of two commonly used anaesthetic drug trays using LCA. This study was performed at a single-centre in Australia. Three trays were compared: 1) reusable tray, 2) single-use tray, and 3) single-use tray with cotton and paper. Data was collected directly from measurements and from databases (EcoInvent). The single-use trays were plastic Chinese-made trays (group 2, 3), and the reusable trays (group 1) were Australian-made nylon trays. The outcome measure was climate change. Since not all data was available, a European energy mix was used, although the Chinese energy mix might be more coal reliant and thus have a higher environmental impact.

McPherson (2019) examined the life cycle carbon footprint of disposable sharps containers (DSC) and reusable sharps containers (RSC) over a 12-month period of facility-wide usage at a hospital geographically distant from manufacturing and processing plants, and include all unit processes in manufacture, transport, washing and treatment and disposal stages. A cradle to-grave life cycle inventory (LCI) and a product-system assessment tool were utilized. This study was perfect in a multi-centre setting in the US. The outcome measures were climate change and waste. A few limitations were considered. First, the assumption was made regarding the location of the polymer manufacturer for DSC, since there was no actual data available. Second, a UK database was used to measure the impact of transport.

Vozzola (2018) conducted an LCA to assess the environmental impacts of two different isolation gowns: reusable and disposable. The functional unit was 1000 isolation gowns uses. This study is an analysis from cradle to grave including manufacturing, use and end-of-life stages of the gown systems. The Environmental Clarity, Inc. LCA database was used to evaluate the life cycles of both isolation gown systems. Sixteen disposable isolations gowns from 5 suppliers were studied, composed primarily of nonwoven polypropylene fabric. Eight reusable isolation gowns were studied, composed of primarily woven polyester fabric. The outcome measures were climate change and waste.

Vozzola (2018) conducted an LCA to assess the environmental impacts of two different cleanroom coveralls: reusable and disposable. This study is an analysis from cradle to crave, quantifying parameters such as energy use and GHG emissions, including different phases: raw material extraction, production, packaging, transport, reuse and disposal in the USA. The outcome measures were climate change and waste. Although Vozzola did compare the packaging material between the reusable and disposable cleanroom coveralls, it was not exactly quantified. The packaging materials vary between the supply companies, and in this study representative materials are used for the different companies, which are therefore not precisely defined per company. This means the data used may deviate from the actual data.

Vozzola (2020) analysed the life cycle of reusable versus disposable gowns to assess the environmental impact of these surgical gowns in the USA. An LCA was conducted according to the standards from the International Organization for Standardization. The Environmental Clarity, Inc. LCA database was used to evaluate the life cycles of both surgical gown systems. The outcome measures were climate change and waste.

Summary of literature – Sub-question 2.2 specific reusable medical instruments versus disposable medical instruments

Description of studies

Davis (2018) compared the environmental impact of single-use flexible ureteroscopes with reusable flexible ureteroscopes. An LCA of the LithoVue single-use digital flexible ureteroscope and Olympus Flexible Video Ureteroscope (URV-F) was performed. Data on raw material extraction, manufacturing, reuse and disposal of the instruments was obtained. The solid waste generated (kg) and energy consumed (kWh) during each case were quantified and used to calculate the CO2 footprint. The outcome measures were climate change and waste. It should be mentioned that data are compared per case, while reusable ureteroscopes can be used multiple times. This might underestimate the actual environmental impact.

Donahue (2020) applied life cycle assessment methods to evaluate the carbon footprints of 3 vaginal specula: a single-use acrylic model and two reusable stainless steel models (grade 304 speculum and grade 316 speculum). Data were obtained regarding packaging composition and weight. As there were no data available on production processes, assumptions were made. For the acrylic specula injection molding was assumed and for the reusable specula a combination of hot extrusion, milling/turning, deformation and heat treatment was assumed, based on literature. The transportation was based on manufacturer and general industry data. Reuse for the steel reusable specula was estimated based on autoclave manufacturer specifications. Disposal was modelled with the use of the EPA WARM model, which estimates the average greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that are associated with disposal of various materials in the USA. Outcome measure was climate change.

Eckelman (2012) assessed the environmental impacts of two types of laryngeal mask airways (LMAs): single-use and reusable (40 lifetime uses) by an LCA. The functional unit was 40 cycles, which meant 40 disposable LMA uses or 40 uses of 1 reusable LMA in the Yale New Haven Hospital, USA. Raw material extraction, production, packaging, transport, reuse and disposal were included in the analysis. The material composition and weights were established on the basis of manufacturer information and density testing. Materials were matched with the most appropriate Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) records from EcoInvent (database). Production processes for hard and soft plastics were assumed to be injection molding and thermoforming, respectively. Data was obtained from distributors to estimate distances and mode of transport. Reprocessing of reusable LMAs was estimated using data from Yale New Haven Hospital and autoclave specifications. Disposal was modelled using US average statistics for solid waste. Outcome measures were climate change, acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, ecotoxicity and ozone depletion.

Ibbotson (2013) The environmental and financial impacts of three surgical scissors which are (1) disposable scissors made of plastic (fibre reinforced), (2) disposable scissors made of stainless steel, and (3) reusable scissors made of stainless steel were assessed using an LCA and life cycle costing method. Data was compared for the use of 4,500 cycles in Germany. The data on raw material, manufacturing (including electricity consumption), transport, and disposal process were obtained from a medical company in Europe. Missing data (e.g. sterilization processes for reusable scissors) were obtained from the literature or expert opinion. Electricity data that was missing was adjusted from the International Energy Agency (IEA). Incineration of plastics, cardboard and municipal solid waste were assumed based on Swiss plants in 2000 (from EcoInvent). The outcome measures were climate change, acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, ecotoxicity and ozone depletion. Due to missing data another energy mix and recycling data was used. Data sources were not comparable between the scissors, since the plastic disposable and stainless steel reusable data was obtained from company data and the stainless steel disposable scissor data was obtained from literature.

Leiden (2020) compared a reusable and a disposable instrument set for one single surgery lumbar fusion in Germany. Data on manufacturing was based on weight, material and form of instruments, data of transportation on mode and calculated distances between producer, distributor, and hospital and washing and steam sterilization data was specific to a German hospital. Disposal was modelled using EcoInvent waste incineration processes. Outcome measures were climate change and acidification. An important limitation could be that only one surgery is compared, which seems invalid for the reusable set. In the sensitivity analysis the impact of the reusable set for 300 use cycles is quantified, however this is compared to one use cycle of the disposable set, and therefore not accurate. Furthermore, the comparison was made between a reusable set comprising six boxes with eleven trays (weight 45.5 kg) with a very lean disposable set (2 kg). For comparison purposes it is also important to note that sterilisation was performed outside the hospital, which increases the environmental impact because of transportation. The study was funded by Neomedical S.A., the producer of the disposable instrument set.

McGain (2012) assessed the environmental and financial impacts of a single-use and a reusable venous catheter insertion kit at the Western Health group of hospitals in Australia. They also investigated the effect of the source of electricity on CO2 emissions. The functional unit was the use of one central venous catheter kit to aid insertion of a single-use, central venous catheter in an operating room. Data on the components was obtained by weighing and manufacturer data. Direct data regarding materials and energy were collected using a "time-in-motion" study. Other inputs were acquired from LCI databases or industry data. Electricity and hot and cold water used by the washer and sterilizer were measured. Data on waste disposal processes were obtained indirectly from industry data. The outcome measure was climate change. A limitation of the study was that the reusable insertion kit is compared to the disposable for one use of inserting the single-use central venous catheter. Calculating the difference between the outcomes when reusing this kit is not taken into account and could yet obtain more accurate results.

McGain (2017) assessed the environmental and financial impact of reusable and single-use anaesthetic equipment through a consequential LCA approach. Five scenarios were assessed and included: (1) "all reusable anaesthetic equipment", (2) "all disposable anaesthetic equipment except for reusable handles for direct laryngoscopes", (3) "all disposable/single-

use anaesthetic equipment (including single-use direct laryngoscope handles; modelled practice)", (4) "replace only reusable face masks with single-use face masks", (5) "replace only direct laryngoscope reusable blades with single-use blades". Data on equipment were obtained from two hospitals in Melbourne, Australia in 2015 and each piece of equipment was weighed with an electronic balance. Sterilization records and input from one hospital were used to define sterilization mode and load information. Washer and steam sterilizer utility usage data were taken from a previous study by the same authors, while electricity consumption of a standard H2O2 sterilizer was directly measured over several days. All other data were sourced from inventory databases based on average industry inputs. Outcome measures were climate change, eutrophication, waste, human toxicity and ecotoxicity.

Namburar (2022) performed an audit of waste generated during endoscopic procedures at a low and high endoscopy volume academic medical centre in the USA over a 5-day work period in 2020. Colonoscopies, upper endoscopies, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography were included. The waste from the pre-procedure area, examination room and post-procedure area was collected. In the high volume hospital the waste from endoscope reprocessing was also obtained. An estimation of the contribution of single-use (compared to reusable) waste was made in the following three scenarios: (1) all reusable endoscopes, (2) colonoscopies and ERCPs were performed with single-use endoscopes (colonoscopes/duodenoscopes) and (3) all single-use endoscopes. Outcome measure was waste. The study aims to estimate the environmental impact of an endoscopic procedure, however, only describes the amount of waste and does not calculate the actual environmental impact.

Rizan (2021) assessed environmental and financial impacts of hybrid and single-use instruments in laparoscopic cholecystectomy using an LCA. The number of three types of instruments (clip appliers, laparoscopic scissors, ports) were included in the analysis (two small diameter ports, two large diameter ports, one laparoscopic scissor and one laparoscopic clip applier). The stages of raw material extraction, manufacture, transport, disposal and decontamination for reusable components of hybrid instruments were included. Data was obtained from manufacturers and databases. Outcomes were climate change, acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, ecotoxicity and ozone depletion.

Sanchez (2020) assessed the environmental and economic impacts of reusable and disposable blood pressure cuffs by using LCA. Data on materials and manufacturing was gathered through manufacturer information and physical testing (by weighing component on a scale), components were identified and matched with information from inventory databases (US-EI LCI database), and the US EPA database was used for transport packaging information. Multiple cleaning scenarios were developed to represent a diversity of clinical settings in using and cleaning. For disposal data landfill and incineration were included. The lifespan of the reusable cuff is taken to be three years, as described in the manufacturer’s specifications. Outcome measures were climate change, acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, ecotoxicity and ozone depletion. There is data uncertainty associated with some of the modelling parameters (e.g. energy, blood pressure cuff materials).

Sherman (2018) assessed the environmental and financial impacts of three different types of rigid laryngoscope handle and tongue blade: plastic single-use, metal single-use, and stainless steel reusable by using LCA and life cycle costing. To determine the material composition of handles and blades a combination of manufacturer specifications, deconstruction, and density testing were used, and after each material was weighed. Foreground data were collected, including transportation mode and distance; washer and autoclave-related energy, water, and chemical use. Reusable components were assumed to have a lifespan of 4000 uses and require refurbishment every 40 uses, according to rated lifetimes of each component. For disposal data recycling, incineration and landfill were included. Outcome measures were climate change, acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, ecotoxicity and ozone depletion.

Results

In this module the results and environmental hotspots are presented in a separate table per outcome measure to provide an overview. A more detailed summary of the methods, results, and interpretation is depicted in the evidence table. The results could not be pooled due to different functional units, assumptions, methods, and comparison. Given that all comparisons involve the assessment of reusable versus disposable medical devices, the results from sub question 2.1 (n=9: Grimmond, 2012; Grimmond, 2021; Hicks, 2016; McGain, 2010; McPherson, 2019; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2020) and sub question 2.2 (n= 11: Davis, 2018; Donahue, 2020; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Leiden, 2020; McGain, 2012; McGain, 2017; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Scherman, 2018) are presented in one overview.

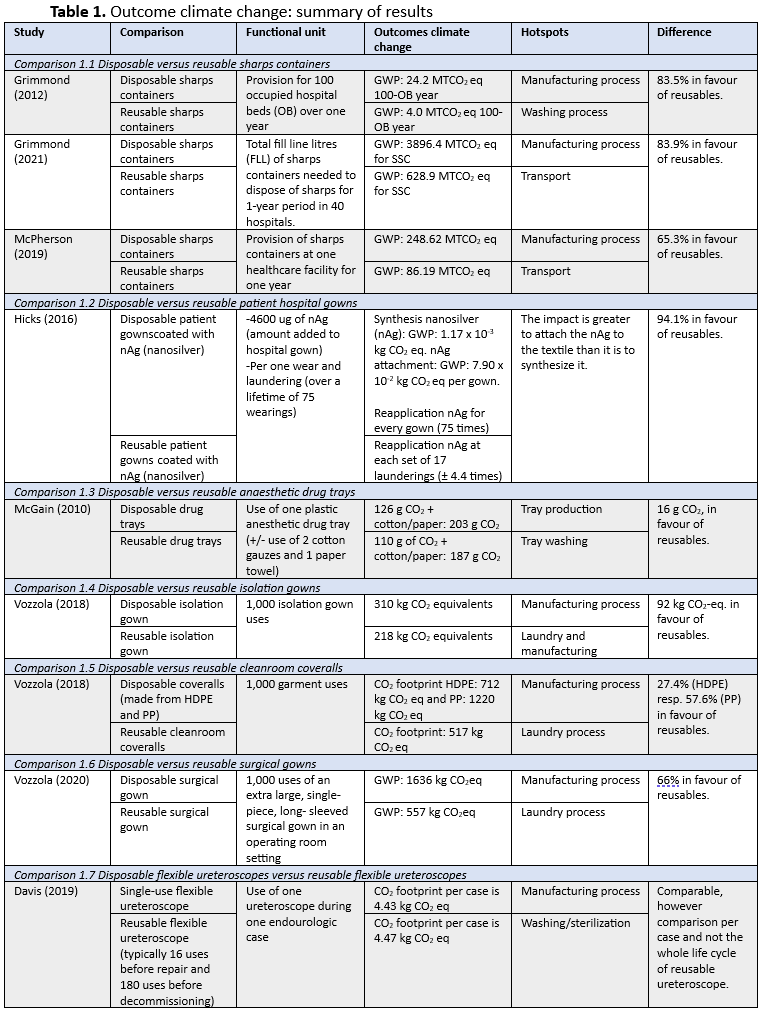

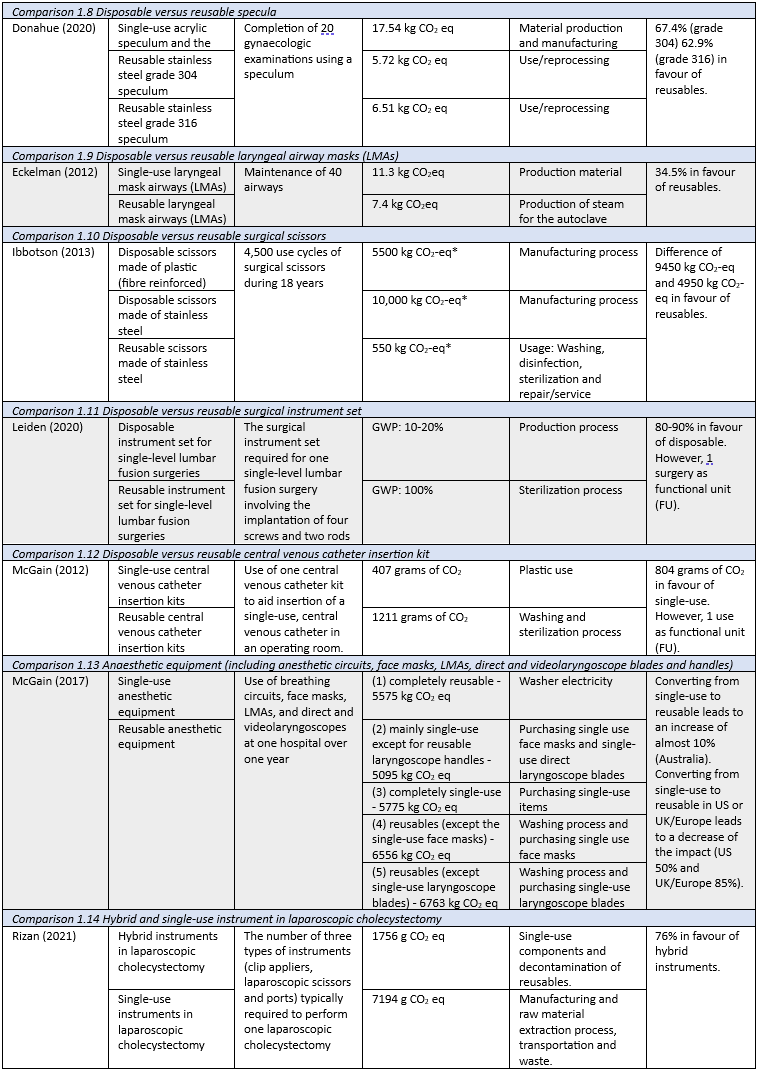

1. Climate Change

Eighteen out of twenty studies reported on the outcome climate change (Grimmond, 2012; Grimmond, 2021; McPherson, 2019; Hicks, 2016; McGain, 2010; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2020; Davis, 2019; Donahue, 2020; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Leiden, 2020; McGain, 2012; McGain, 2017; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018). The 18 studies contained 16 comparisons. A summary of the results is presented in Table 1. Most studies resulted in a difference in favour of reusables.

*Read from figure (Ibbotson, 2013)

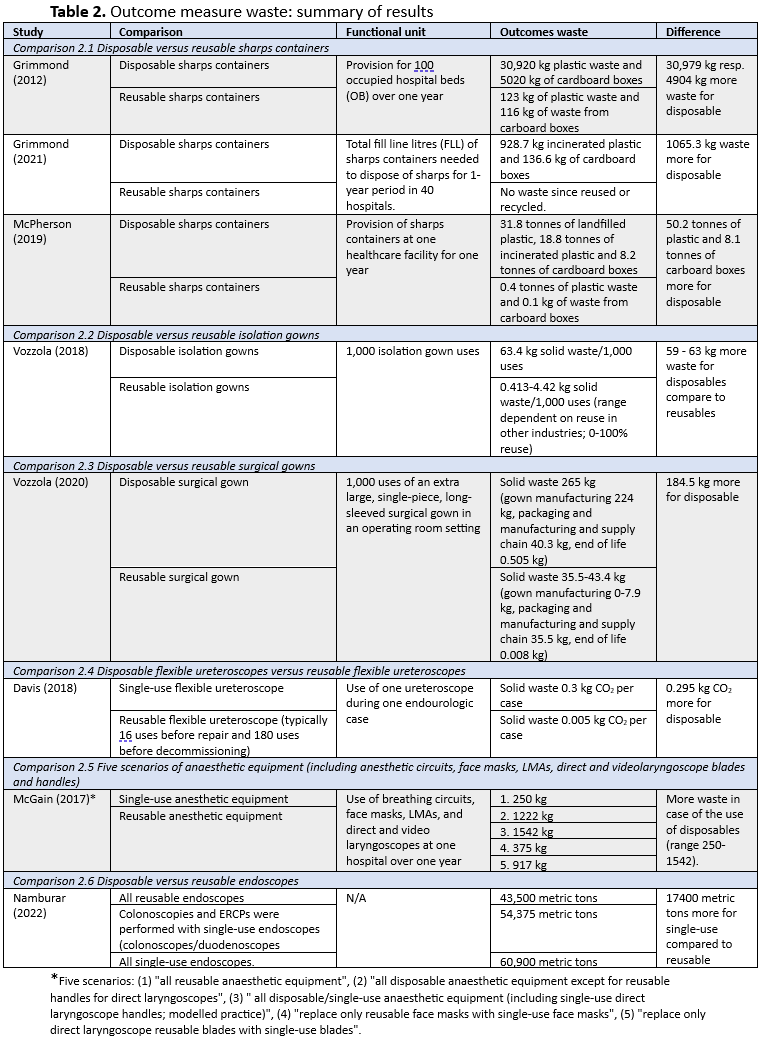

2. Waste

Eight out of twenty studies reported on the outcome waste (Grimmond, 2012; Grimmond, 2021; McPherson, 2019; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2020; Davis, 2018; McGain, 2017; Namburar, 2022). The eight studies contained 6 comparisons. A summary of the results is presented in Table 2. All studies resulted in a difference in favour of reusables.

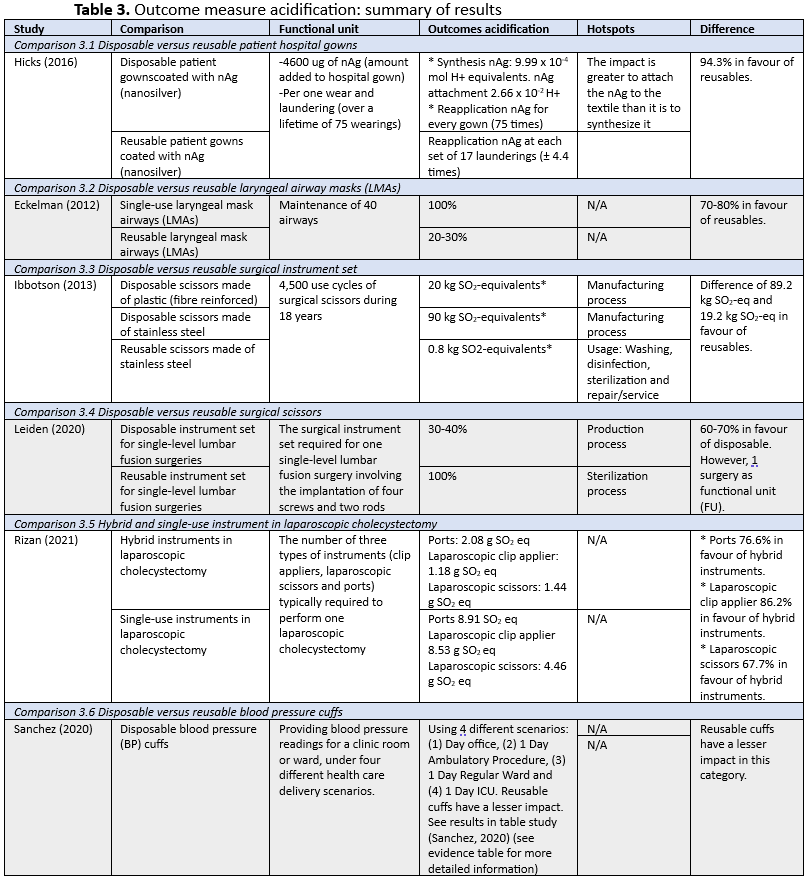

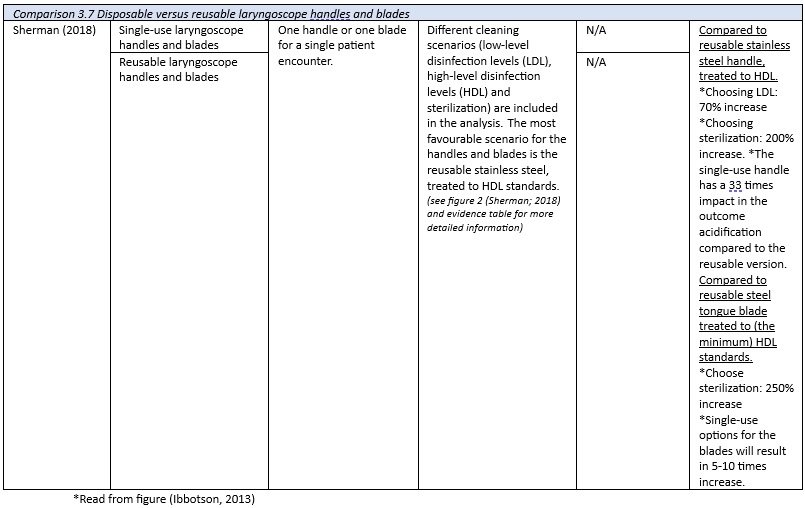

3. Acidification

Seven out of twenty studies reported on the outcome acidification (Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Leiden, 2020; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018). The seven studies contained seven comparisons. A summary of the results is presented in Table 3. Most studies resulted in a difference in favour of reusables.

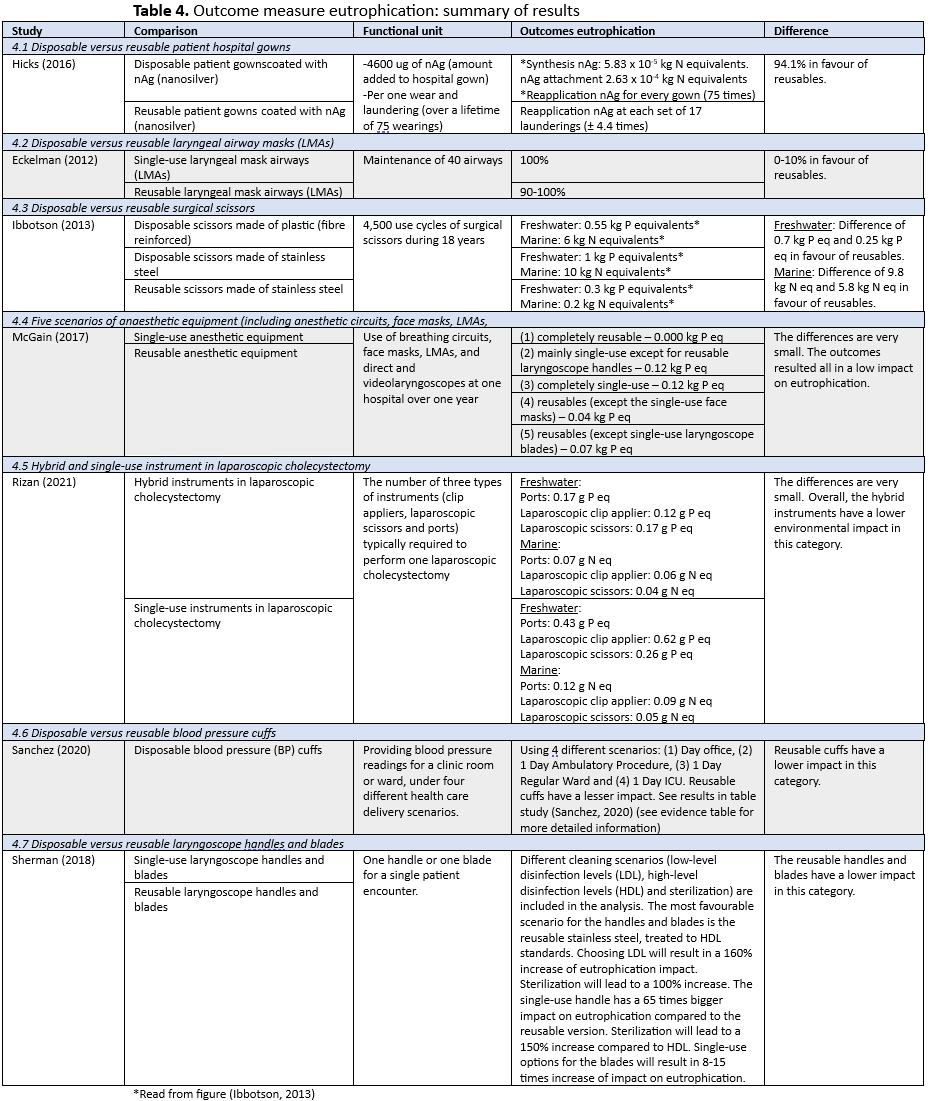

4. Eutrophication

Seven out of twenty studies reported on the outcome eutrophication (Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; McGain, 2017; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018). The seven studies contained seven comparisons. A summary of the results is presented in Table 4. The majority of the studies resulted in favour of reusables.

5. Human toxicity

Seven out of twenty studies reported on the outcome human toxicity (Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; McGain, 2017; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018). A summary of the results is presented in Table 5. Most studies resulted in favour of reusables.

6. Ecotoxicity

Seven out of twenty studies reported on the outcome ecotoxicity (Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; McGain, 2017; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018). A summary of the results is presented in Table 5. Most studies resulted in favour of reusables.

7. Ozone depletion

Seven out of twenty studies reported on the outcome ozone depletion (Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; McGain, 2017; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018). A summary of the results is presented in Table 7. Most studies resulted in favour of reusables.

Level of evidence of the literature

The working group assessed the level of evidence of LCAs using GRADE and used the critical appraisal of LCAs (Drew, 2021) to provide an indication of the study quality. See module 'operatietechnieken' for more details. As mentioned before, given that all comparisons involve the assessment of reusable versus disposable medical devices, the level of evidence of literature from sub question 2.1 and sub question 2.2 are presented in one overview.

1. Climate Change

Eighteen studies reported on the outcome ´climate change´ (Grimmond, 2012; Grimmond, 2021; McPherson, 2019; Hicks, 2016; McGain, 2010; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2020; Davis, 2019; Donahue, 2020; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Leiden, 2020; McGain, 2012; McGain, 2017; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018). The 18 studies contained 16 comparisons. The level of evidence starts at grade high. The level of evidence was downgraded with 2 levels to low because of risk of bias (-1; limitations on functional unit, limited transparency on characterization, sensitivity/uncertainty analyses were lacking, limitations inadequately critically appraised) and indirectness (-1; heterogeneity of interventions, limited representativeness of data).

2. Waste

Eight studies reported on the outcome ´waste´ (Grimmond, 2012; Grimmond, 2021; McPherson, 2019; Vozzola, 2018; Vozzola, 2020; Davis, 2018; McGain, 2017; Namburar, 2022). As seven out of eight studies contain LCAs, the level of evidence starts at grade high. The level of evidence was downgraded with 2 levels to low because of risk of bias (-1; unclear rational, limitations on functional unit, unclear system boundaries or stages, limited transparency on characterization, sensitivity/uncertainty analyses were lacking, limitations inadequately critically appraised) and indirectness (-1; heterogeneity of interventions, limited representativeness of data).

3. Acidification

Seven studies reported on the outcome acidification (Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Leiden, 2020; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018). The level of evidence starts at grade high. The level of evidence was downgraded with 2 levels to low because of risk of bias (-1; unclear system boundaries or stages, sensitivity/uncertainty analyses were lacking, limitations inadequately critically appraised) and indirectness (-1; heterogeneity of interventions, limited representativeness of data).

4. Eutrophication

Seven studies reported on the outcome ´eutrophication´ (Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Leiden, 2020; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018). The level of evidence starts at grade high. The level of evidence was downgraded with 2 levels to low because of risk of bias (-1; unclear system boundaries or stages, sensitivity/uncertainty analyses were lacking, limitations inadequately critically appraised) and indirectness (-1; heterogeneity of interventions, limited representativeness of data).

5. Human toxicity

Seven studies reported on ´human toxicity´ (Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Leiden, 2020; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018). The level of evidence starts at grade high. The level of evidence was downgraded with 2 levels to low because of risk of bias (-1; unclear system boundaries or stages, sensitivity/uncertainty analyses were lacking, limitations inadequately critically appraised) and indirectness (-1; heterogeneity of interventions, limited representativeness of data).

6. Ecotoxicity

Seven studies reported on the outcome ecotoxicity (Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Leiden, 2020; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018). The level of evidence starts at grade high. The level of evidence was downgraded with 2 levels to low because of risk of bias (-1; unclear system boundaries or stages, sensitivity/uncertainty analyses were lacking, limitations inadequately critically appraised) and indirectness (-1; heterogeneity of interventions, limited representativeness of data).

7. Ozone depletion

Seven studies reported on the outcome ozone depletion (Hicks, 2016; Eckelman, 2012; Ibbotson, 2013; Leiden, 2020; Rizan, 2021; Sanchez, 2020; Sherman, 2018). The level of evidence starts at grade high. The level of evidence was downgraded with 2 levels to low because of risk of bias (-1; unclear system boundaries or stages, sensitivity/uncertainty analyses were lacking, limitations inadequately critically appraised) and indirectness (-1; heterogeneity of interventions, limited representativeness of data).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

PICO1: What is the difference in sustainability of reusables compared to disposables in the operating room for patients who undergo surgery?

P = Patients who undergo a surgical procedure

I = Reusables, such as: surgical gowns, scrub caps, gloves, glasses, perioperative textiles (i.e. blue drapes, band aids), packing materials, or laryngeal masks

C = Disposables, such as: surgical gowns, scrub caps, gloves, glasses, perioperative textiles (blue drapes, band aids), packing materials or laryngeal masks

O = Climate change (CO2 footprint/Global Warming Potential (GWP)), waste, acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, ecotoxicity, ozone depletion

PICO2: What is the difference in sustainability of specific reusable medical instruments compared to disposable medical instruments in the operating room for patients who undergo surgery?

P = Patients who undergo a surgical procedure

I = Reusable medical instruments, such as: specula, instruments, scopes

(e.g reusable instruments in a surgical tool kit: scissor, Kocher, tweezer, scalpel, needle driver, ligasure, harmonic, stapler, surgical drill; reusable scopes: duodenoscope, ureterorenoscope, bronchoscope, cystoscope, laryngeal scope; reusable meniscal sutures; reusable suture anchors).

C = Disposable medical instruments, such as: specula, instruments, scopes

(e.g disposable instruments in a surgical tool kit: scissor, Kocher, tweezer, scalpel, needle driver, vessel sealer, stapler, surgical drill; disposable scopes: duodenoscope, ureterorenoscope, bronchoscope, cystoscope, laryngeal scope; disposable meniscal sutures; disposable suture anchors).

O = Climate change (CO2 footprint/Global Warming Potential (GWP)), waste, acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, ecotoxicity, ozone depletion

Relevant outcome measures

Life cycle assessment (LCA) is a methodological tool used to quantitatively analyse the life cycle of products/activities within the context of environmental impact. The assessment comprises all stages needed to produce and use a product, from the initial development to the treatment of waste (the total life cycle). An LCA is mainly based on four phases: 1) goal and scope definition, 2) inventory analysis, 3) impact assessment, and 4) interpretation. The third phase is the life cycle impact assessment (LCIA), in which emissions and resource extractions are translated into a limited number of environmental impact scores by means of so-called characterisation factors. The ReCiPe model is a method for the impact assessment in an LCA (Huijbregts, 2016, Huijbregts, 2017). To determine the outcome measures regarding environmental impact, the ReCiPe model of the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (in Dutch: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu, RIVM) was used.

The outcomes determined by the working group are based on the ReCiPe framework. The working group considered climate change (CO2 footprint/Global Warming Potential) and waste as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, ecotoxicity and ozone depletion as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Outcomes focused on environmental life cycle assessment (LCA) impact categories are relatively new in healthcare. Given the variety in scopes and methods of performing and reporting LCAs, the working group did not define a priori the minimal important difference. Differences between the disposables and reusables were evaluated by the working group after data extraction.

A glossary including the outcome measures is found in module ‘operatietechnieken’.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Pubmed (via NCBI), Embase (via OVID), Web of Science (via Webofscience), Cochrane (via Cochrane library) and Emcare (via OVID) were searched with relevant search terms from 2000 until 7 December 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 694 hits in total. Studies for this module were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic reviews (searched in at least two databases, with a detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available), randomized controlled trials, (observational) comparative studies, life cycle assessments, CO2 footprint studies and environmental impact studies;

- Full-text English language publication; and

- Studies according to the PICO. Studies that compared disposables with reusables related to the OR and included at least one of the following outcomes: climate change, waste, acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, ecotoxicity, ozone depletion.

After reading the full text, 20 studies were included in the literature summary of this module.

Results

Twenty studies were included in the analysis of the literature (sub question 2.1: 9, sub question 2.2: 11). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables (Appendix 1). The quality assessment of the studies is summarized in Appendix 2.

Referenties

- Acero, 2015. Greendelta, LCIA methods: Impact assessment methods in Life Cycle Assessment and their impact categories. Version: 1.5.4. Date: 16 March 2015. Accessed at: https://www.openlca.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/LCIA-METHODS-v.1.5.4.pdf

- Aiolfi A, Lombardo F, Matsushima K, Sozzi A, Cavalli M, Panizzo V, Bonitta G, Bona D. Systematic review and updated network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing open, laparoscopic-assisted, and robotic distal gastrectomy for early and locally advanced gastric cancer. Surgery. 2021 Sep;170(3):942-951. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2021.04.014. Epub 2021 May 20. PMID: 34023140.

- Berners-Lee M. How Bad are Bananas; the Carbon Footprint of Everything. London: Profile Books; 2010.

- CE Delft, 2022a. Klimaatimpact herbruikbare en eenmalige specula - Screening LCA voor het UMC Utrecht. Delft, CE Delft, oktober 2022. Publicatienummer: 22.210358.128. Link: https://ce.nl/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CE_Delft_210358_Klimaatimpact_herbruikbare_en_eenmalige_specula_DEF.pdf

- CE Delft, 2022b. Eenmalige of herbruikbare partusen hechtsets? Milieukundige vergelijking voor het UMC Utrecht Update 2022. Delft, CE Delft, november 2022. Publicatienummer: 22.220162.176. Link: https://ce.nl/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CE_Delft_220162_Eenmalige_of_herbruikbare_partus-_en_hechtsets_Def.pdf

- Davis NF, McGrath S, Quinlan M, Jack G, Lawrentschuk N, Bolton DM. Carbon Footprint in Flexible Ureteroscopy: A Comparative Study on the Environmental Impact of Reusable and Single-Use Ureteroscopes. J Endourol. 2018 Mar;32(3):214-217. doi: 10.1089/end.2018.0001. Epub 2018 Feb 21. PMID: 29373918.

- Donahue LM, Hilton S, Bell SG, Williams BC, Keoleian GA. A comparative carbon footprint analysis of disposable and reusable vaginal specula. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Aug;223(2):225.e1-225.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.007. Epub 2020 Feb 15. PMID: 32067971.

- Drew J, Christie SD, Tyedmers P, Smith-Forrester J, Rainham D. Operating in a Climate Crisis: A State-of-the-Science Review of Life Cycle Assessment within Surgical and Anesthetic Care. Environ Health Perspect. 2021 Jul;129(7):76001.

- Eckelman M, Mosher M, Gonzalez A, Sherman J. Comparative life cycle assessment of disposable and reusable laryngeal mask airways. Anesth Analg. 2012 May;114(5):1067-72. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824f6959. Epub 2012 Apr 4. PMID: 22492190.

- Grimmond T, Reiner S. Impact on carbon footprint: a life cycle assessment of disposable versus reusable sharps containers in a large US hospital. Waste Manag Res. 2012 Jun;30(6):639-42. doi: 10.1177/0734242X12450602. Epub 2012 May 23. PMID: 22627643.

- Grimmond TR, Bright A, Cadman J, Dixon J, Ludditt S, Robinson C, Topping C. Before/after intervention study to determine impact on life-cycle carbon footprint of converting from single-use to reusable sharps containers in 40 UK NHS trusts. BMJ Open. 2021 Sep 27;11(9):e046200. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046200. PMID: 34580089; PMCID: PMC8477330.

- Hicks, A. L., et al. "Environmental impacts of reusable nanoscale silver-coated hospital gowns compared to single-use, disposable gowns." Environmental Science: Nano 3.5 (2016): 1124-1132.

- Huijbregts, M. A., Steinmann, Z. J., Elshout, P. M., Stam, G., Verones, F., Vieira, M., ... & van Zelm, R. (2017). ReCiPe2016: a harmonised life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 22(2), 138-147.

- Huijbregts MAJ, Steinmann ZJN, Elshout PMF, Stam G, Verones F, Vieira MDMManagement Duurzame Melkveehouderij, Hollander A, Van Zelm R, 2016. ReCiPe2016: A harmonized life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. RIVM Rapport 2016-0104. Bilthoven, The Netherlands.

- Ibbotson, S., Dettmer, T., Kara, S. et al. Eco-efficiency of disposable and reusable surgical instrumentsa scissors case. Int J Life Cycle Assess 18, 11371148 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-013-0547-7Muaddi H, Hafid ME, Choi WJ, Lillie E, de Mestral C, Nathens A, Stukel TA, Karanicolas PJ. Clinical Outcomes of Robotic Surgery Compared to Conventional Surgical Approaches (Laparoscopic or Open): A Systematic Overview of Reviews. Ann Surg. 2021 Mar 1;273(3):467-473. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003915. PMID: 32398482.

- Leiden, Alexander, et al. "Life cycle assessment of a disposable and a reusable surgery instrument set for spinal fusion surgeries." Resources, Conservation and Recycling 156 (2020): 104704.

- McGain F, McAlister S, McGavin A, Story D. The financial and environmental costs of reusable and single-use plastic anaesthetic drug trays. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2010 May;38(3):538-44. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1003800320. PMID: 20514965.

- McGain F, Muret J, Lawson C, Sherman JD. Environmental sustainability in anaesthesia and critical care. Br J Anaesth. 2020 Nov;125(5):680-692. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.055. Epub 2020 Aug 12. PMID: 32798068; PMCID: PMC7421303.

- McGain F, McAlister S, McGavin A, Story D. A life cycle assessment of reusable and single-use central venous catheter insertion kits. Anesth Analg. 2012 May;114(5):1073-80. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824e9b69. Epub 2012 Apr 4. PMID: 22492185.

- McGain F, Story D, Lim T, McAlister S. Financial and environmental costs of reusable and single-use anaesthetic equipment. Br J Anaesth. 2017 Jun 1;118(6):862-869. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex098. PMID: 28505289.

- McPherson B, Sharip M, Grimmond T. The impact on life cycle carbon footprint of converting from disposable to reusable sharps containers in a large US hospital geographically distant from manufacturing and processing facilities. PeerJ. 2019 Feb 22;7:e6204. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6204. PMID: 30809428; PMCID: PMC6388662.

- Namburar S, von Renteln D, Damianos J, Bradish L, Barrett J, Aguilera-Fish A, Cushman-Roisin B, Pohl H. Estimating the environmental impact of disposable endoscopic equipment and endoscopes. Gut. 2022 Jul;71(7):1326-1331.

- Rizan C, Bhutta MF. Environmental impact and life cycle financial cost of hybrid (reusable/single-use) instruments versus single-use equivalents in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2022 Jun;36(6):4067-4078. doi: 10.1007/s00464-021-08728-z. Epub 2021 Sep 24. PMID: 34559257; PMCID: PMC9085686.

- Sanchez A., Eckelman M.J., Sherman J.D. Environmental and economic comparison of reusable and disposable blood pressure cuffs in multiple clinical settings. Resources, Conservation and Recycling Vol. 155, Pages 104643 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104643

- Siu J, Hill AG, MacCormick AD. Systematic review of reusable versus disposable laparoscopic instruments: costs and safety. ANZ J Surg. 2017 Jan;87(1-2):28-33. doi: 10.1111/ans.13856. Epub 2016 Nov 23. PMID: 27878921.

- Sherman JD, Raibley LA 4th, Eckelman MJ. Life Cycle Assessment and Costing Methods for Device Procurement: Comparing Reusable and Single-Use Disposable Laryngoscopes. Anesth Analg. 2018 Aug;127(2):434-443. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002683. PMID: 29324492.

- The Carbon Trust (2018) Carbon Footprinting. https://www.carbontrust.com/resources/carbon-footprinting-guide

- Vozzola E, Overcash M, Griffing E. Life Cycle Assessment of Reusable and Disposable Cleanroom Coveralls. PDA J Pharm Sci Technol. 2018 May-Jun;72(3):236-248. doi: 10.5731/pdajpst.2017.007864. Epub 2018 Feb 14. PMID: 29444994.

- Vozzola E, Overcash M, Griffing E. Environmental considerations in the selection of isolation gowns: A life cycle assessment of reusable and disposable alternatives. Am J Infect Control. 2018 Aug;46(8):881-886.

- Vozzola E, Overcash M, Griffing E. An Environmental Analysis of Reusable and Disposable Surgical Gowns. AORN J. 2020 Mar;111(3):315-325. doi: 10.1002/aorn.12885. PMID: 32128776.

Evidence tabellen

Appendix 1. Evidence tables

Evidence table for systematic reviews

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Product/service characteristics |

Intervention (I) and Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Drew (2021)

|

SR of LCAs in anaesthetic and surgical care. It aims to summarize the state of LCA practice via review of literature assessing the environmental impact of related services, procedures, equipment and pharmaceuticals.

Literature search up to may 2020

The review was guided by using STARR-LCA, which is a PRISMA-based framework.

Study design: LCA

Setting and Country: Anaesthetic and surgical care, Canada.

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: None stated.

|

Inclusion criteria SR: Studies which assessed the environmental impact(s) of (1) an operating room(s) using LCA, (2) a specific surgical procedure(s) using LCA or (3) equipment or pharmaceuticals used in surgical settings.

Exclusion criteria SR: No access, no English language, no research in relation to healthcare, healthcare related but not related to surgery or anaesthesiology, no use of LCAs.

44 included studies |

These studies examined the impact contributions from (A) ORs generally (n=1) (B) specific surgical procedures (n=10) (C) provision and use of surgical or anaesthetic equipment or pharmaceuticals (n=33) |

End-point of follow-up: N/A

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N/A

|

(A) Operating rooms The climate impact of the hospitals’ surgical suites ranged from 3,200,000 to 5,200,000 kg CO2e per year and between 146 and 232 kg CO2e per operation (when compared on a caseload basis).

(B) Surgical procedures The outcomes on climate change were found to vary considerably (6-1,007 kg CO2e). See figure 2 (Drew, 2021).

(C) Equipment and materials and pharmaceuticals Most disposable equipments/materials were more harmful for the environment compared to reusables. Figure 4 (Drew, 2021) includes the other outcome measures for provision and use of disposables relative to functionally equivalent reusables. For use of pharmaceuticals, GHG emissions from propofol were considerably lower than inhalational agents (i.e., desflurane, isoflurane and sevoflurane).

|

Authors conclusion: LCA data indicates the environmental burden attributable to the services is substantial and effective mitigation strategies are already available. Eligible studies varied in terms of quality, completeness and risk of bias, with critical appraisal scores varying between 44% and 89%.

(A) Only one study is found comparing different ORs on environmental impact and identifying hotpots. Results could not be pooled. (B) The studies varied considerably in their system boundaries and functional units, which leads to heterogeneity of the studies. Results could not be pooled. (C) Functional units varied considerably between the studies. There is a high degree of heterogeneity, in terms of studied items and methodology.

Interpretation of results (A) For the OR certain emission hotspots were identified: use of anaesthetic gases and use of HVAC. (B) OR energy was a great hotspot, mainly due to HVAC. Next to that provision and use of anaesthetic gases and production of equipment and consumables contribute mainly. (C) Considering the life cycle of single-use items, the most contributing phase is the production phase. Single-use items are more often worse for the environment compared to reusables. When using reusables the energy source has to be taken into account, since the reuse phase is the biggest contributor, which requires energy. |

Evidence table for LCA studies

1Goals and scope: ‘Phase of life cycle assessment in which the aim of the study, and in relation to that, the breadth and depth of the study is established’

2Functional unit: Quantified description of the function of a product or process that serves as the reference basis for all calculations regarding impact assessment

Appendix 2. Critical appraisal of LCAs (based on Drew, 2021)

Drew (2021) developed a critical appraisal pro forma, based on Weidema’s guidelines for critical review of LCA (Weidema, 1997). This scoring system consists of 16 appraisal criteria, which are divided between the different phases of an LCA. It addresses a range of study quality indicators, such as internal validity, external validity, consistency, transparency, and bias. The percentage score provides an indication of the overall study quality. A higher score indicates a higher overall study quality. The points that can be obtained are displayed in the column labeled "appraisal criteria".

|

Appraisal criteria |

Indicator(s) |

Key effect modifiers |

Grimmond (2012) |

Grimmond (2021) |

Hicks (2016) |

McGain (2010) |

McPherson (2019) |

Vozzola (2018) CC* |

Vozzola (2018) IG** |

Vozzola (2020) |

Davis (2018) |

Donahue (2020) |

|

Phase 1: Goal & Scope (13 points) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Study goal is clearly stated, including the study's rationale (1), intended application (1), and intended audience (1) |

Transparency |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2

|

3 |

|

|

Lifecycle assessment method is clearly stated (1) |

Transparency |

Process-based life-cycle assessment, which is well suited to product-level analysis, may underestimate environmental impacts (i.e. from truncation error); economic input-output lifecycle assessment (EIO-LCA), which uses aggregate data and is well-suited to sector-level analysis, may overestimate environmental impacts |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

Functional unit is clearly defined and measurable (1), justified (1), and consistent with the study's intended application (1) |

Consistency |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

|

|

The system to be studied is adequately described with clearly stated system boundaries (1), lifecycle stages (1), and appropriate justification of any omitted stages (1) |

Transparency; Bias |

Assessments with narrow system boundaries that exclude a number of lifecycle stages are prone to underestimating life-cycle environmental impacts |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

|

The system covers production (1), use/reuse (1) and disposal (1) of materials and energy (half mark if only for energy and vice versa) |

Internal Validity, Completeness |

|

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

Phase 2: Inventory analysis (7 points) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The data collection process is clearly explained, including the source(s) of foreground material weights and energy values (1); the source(s) of reference data (e.g. inventory database; 1); and what data are included (e.g. production and disposal of unit processes; 1) |

Transparency, Internal Validity |

|

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

|

Representativeness of the data is discussed (1), differences in electricity generating mix are accounted for (1), and the potential significance of exclusions or assumptions is addressed (1) |

Internal validity; External validity |

|

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

Allocation procedures, where necessary, are described and appropriately justified (1; mark given if no allocation used) |

Transparency; Bias |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Phase 3: Impact assessment (6 points) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Impact categories (1), characterization method (1), and software used (1) are documented transparently |

Transparency |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|

|

Results are clearly reported in the context of the functional unit (1) (0.5 if graphically, 0 if only normalized results reported) |

Consistency; Transparency |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

A contribution analysis is performed and clearly reported (1), and hotspots are identified (1) |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

||

|

Phase 4: Interpretation (9 points) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conclusions are consistent with the goal and scope (1) and supported by the impact assessment results (1) |

Internal validity; Consistency |

|

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Results are contextualized through the use of sensitivity analysis (1) and uncertainty analysis (1) |

Internal validity |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Limitations are adequately discussed (1), and the potential impact of omissions or assumptions on the study's outcomes are described (1) |

Bias |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

The assessment has been critically appraised (i.e. peer review if journal article or independent, external critical review if report/thesis; 1) |

Bias |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Source(s) of funding and any potential conflict(s) of interest are disclosed (1), and are unlikely to be a source of bias (1) |

Bias |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0.5 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Total (/35) |

25 |

25 |

27 |

28 |

27 |

27 |

23.5 |

28 |

21 |

29 |

||

|

Percentage score |

71% |

71% |

77% |

80% |

77% |

77% |

67% |

80% |

60% |

83% |

*CC: Cleanroom Coveralls, ** IG: Isolation Gowns

|

Appraisal criteria |

Indicator(s) |

Key effect modifiers |

Donahue (2020) |

Eckelman (2012) |

Ibbotson (2013) |

Leiden (2020) |

McGain (2012) |

McGain (2017) |

Rizan (2021) |

Sanchez (2020) |

Sherman (2018) |

|

Phase 1: Goal & Scope (13 points) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Study goal is clearly stated, including the study's rationale (1), intended application (1), and intended audience (1) |

Transparency |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

|

Lifecycle assessment method is clearly stated (1) |

Transparency |

Process-based life-cycle assessment, which is well suited to product-level analysis, may underestimate environmental impacts (i.e. from truncation error); economic input-output lifecycle assessment (EIO-LCA), which uses aggregate data and is well-suited to sector-level analysis, may overestimate environmental impacts |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Functional unit is clearly defined and measurable (1), justified (1), and consistent with the study's intended application (1) |

Consistency |

2 |

3 |

3

|

3 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

|

|

The system to be studied is adequately described with clearly stated system boundaries (1), lifecycle stages (1), and appropriate justification of any omitted stages (1) |

Transparency; Bias |

Assessments with narrow system boundaries that exclude a number of lifecycle stages are prone to underestimating life-cycle environmental impacts |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

|

The system covers production (1), use/reuse (1) and disposal (1) of materials and energy (half mark if only for energy and vice versa) |

Internal Validity, Completeness |

|

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

Phase 2: Inventory analysis (7 points) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The data collection process is clearly explained, including the source(s) of foreground material weights and energy values (1); the source(s) of reference data (e.g. inventory database; 1); and what data are included (e.g. production and disposal of unit processes; 1) |

Transparency, Internal Validity |

|

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

Representativeness of the data is discussed (1), differences in electricity generating mix are accounted for (1), and the potential significance of exclusions or assumptions is addressed (1) |

Internal validity; External validity |

|

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

Allocation procedures, where necessary, are described and appropriately justified (1; mark given if no allocation used) |

Transparency; Bias |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Phase 3: Impact assessment (6 points) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Impact categories (1), characterization method (1), and software used (1) are documented transparently |

Transparency |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

|

Results are clearly reported in the context of the functional unit (1) (0.5 if graphically, 0 if only normalized results reported) |

Consistency; Transparency |

|

1 |

1 |

0.5 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

A contribution analysis is performed and clearly reported (1), and hotspots are identified (1) |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

||

|

Phase 4: Interpretation (9 points) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conclusions are consistent with the goal and scope (1) and supported by the impact assessment results (1) |

Internal validity; Consistency |

|

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Results are contextualized through the use of sensitivity analysis (1) and uncertainty analysis (1) |

Internal validity |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Limitations are adequately discussed (1), and the potential impact of omissions or assumptions on the study's outcomes are described (1) |

Bias |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

The assessment has been critically appraised (i.e. peer review if journal article or independent, external critical review if report/thesis; 1) |

Bias |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Source(s) of funding and any potential conflict(s) of interest are disclosed (1), and are unlikely to be a source of bias (1) |

Bias |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Total (/35) |

29 |

30 |

26.5 |

25.5 |

29 |

23 |

29 |

29 |

30 |

||

|

Percentage score |

83% |

86% |

76% |

73% |

83% |

66% |

83% |

83% |

86% |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 07-02-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 08-01-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze Leidraad Duurzaamheid (bestaande uit Deel A - Methodologische Handreiking en Deel B - Inhoudelijke duurzaamheidsmodules) werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Doel en doelgroep

Het doel van dit project is om algemene handvatten te ontwikkelen voor het opnemen van duurzaamheid met betrekking tot het milieu bij revisie van bestaande of ontwikkeling van nieuwe landelijke richtlijnen in de snijdende disciplines. Met deze Methodologische Handreiking wil deze werkgroep toekomstige richtlijncommissies van professionele standaarden (e.g. leidraden, richtlijnen, modules) kaders bieden om duurzaamheid op de juiste wijze mee te nemen.