Therapie bij Helicobacter pylori-infectie

Uitgangsvraag

a. Wat is de optimale primaire behandelstrategie voor kinderen van 0-18 jaar met een H. pylori-infectie?

b. Wat is de optimale behandelstrategie voor kinderen van 0-18 jaar met een resistente H. pylori-infectie?

Aanbeveling

Bepaal de eradicatietherapie op basis van de H. pylori antibioticaresistentiebepaling (zie module Diagnostiek bij gastroduodenoscopie). De aanbevolen therapie wordt in onderstaande tabel weergegeven.

|

Gevoeligheid H. pylori stam voor CLA |

Aanbevolen therapie |

|

Bekend gevoelig voor CLA |

1ste keus: PPI-AMO-CLA 14 dagen 2e keus: PPI-AMO-MET 14 dagen |

|

Bekend resistent tegen CLA |

PPI-AMO-MET 14 dagen met hoge dosering voor AMO |

|

Gevoeligheid onbekend |

PPI-AMO-MET 14 dagen met hoge dosering voor AMO |

AMO = amoxicilline; CLA = claritromycine; MET = metronidazol; PPI = protonpompremmers (omeprazol of esomeprazol)

Doseringen volgens www.kinderformularium.nl

- Gebruik tripeltherapie met claritromycine (als gevoelig) en metronidazol bij penicillineallergie. Als de H. pylori stam resistent is tegen claritromycine, wordt tripeltherapie met tetracycline, PPI, en metronidazol aanbevolen bij kinderen > 8 jaar oud. Bij kinderen < 8 jaar: overweeg om fluorochinolonen toe te voegen aan de tripeltherapie. Overweeg om bismuth* toe te voegen voor een nog betere effectiviteit.

* Bismut is op dit moment niet verkrijgbaar in Nederland en moet daarom via de internationale apotheek komen wanneer dit wordt voorgeschreven.

Als na controle op eradicatie blijkt dat de behandeling niet effectief is geweest (zie onderaan de aanbeveling), wordt er een tweede behandeling geadviseerd. Baseer deze op de eerdere H. pylori antibioticaresistentiebepaling (als bekend) en de vorige eradicatietherapie.

Overweeg opnieuw een gastroduodenoscopie met biopten te verrichten, om de gevoeligheid van H. pylori te bepalen bij een gefaalde eradicatietherapie met een adequate therapietrouw.

|

Gevoeligheid H. pylori stam voor CLA |

Vorige therapie |

Aanbevolen “rescue” therapie |

|

Bekend gevoelig voor CLA |

PPI-AMO-CLA 14 dagen |

PPI-AMO-MET 14 dagen |

|

Bekend gevoelig voor CLA |

PPI-AMO-MET 14 dagen |

PPI-AMO-CLA 14 dagen |

|

Bekend resistent tegen CLA |

PPI-AMO-MET 14 dagen met hoge dosering voor AMO |

Overweeg toevoegen bismut |

|

Gevoeligheid onbekend |

PPI-AMO-MET 14 dagen met hoge dosering voor AMO |

Overweeg toevoegen bismut

|

Bespreek met de patiënt en ouders het belang van therapietrouw voor een succesvolle eradicatie van H. pylori.

Test zes tot acht weken na beëindigen van de therapie het succes van de behandeling door middel van een non-invasieve test (feces-antigeentest of 13C-ureum-ademtest [UBT]).

Wacht tot ten minste twee weken na stoppen van protonpompremmers (PPI’s) en vier weken na stoppen van antibiotica en bismut voor het inzetten van de non-invasieve test. Indien PPI’s niet gestaakt kunnen worden, overweeg dan om H2-antagonisten voor te schrijven (naast endoscopische bevindingen).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek gedaan naar de (kosten-)effectiviteit van sequentiële therapie in vergelijking met standaard tripeltherapie bij kinderen met een H. pylori-infectie. Er werden vijf studies geïncludeerd, waarvan één systematische review. Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat effectiviteit van de behandeling konden de data van de studies worden gepooled, waarbij werd gevonden dat sequentiële therapie effectiever zou kunnen zijn in het behandelen van een H. pylori-infectie dan standaard tripeltherapie bij kinderen. Echter is de gevonden risk ratio van 1.14 niet klinisch relevant en is de bewijskracht hiervan laag, waardoor er veel onzekerheid over deze conclusie is. Dit wordt veroorzaakt doordat veel studies niet blindeerden, de randomisatieprocedure niet helder werd omschreven en de gevonden resultaten in de verschillende studies inconsistent zijn.

Als onderdeel van de literatuuranalyse werden ook subgroepen-analyses uitgevoerd, waarbij geen verschil werd gevonden tussen sequentiële therapie bestaande uit tinidazol en metronidazol. Wel werd er verschil gevonden in effectiviteit afhankelijk van welke controle werd gebruikt. Zo bleek sequentiële therapie effectiever dan de controle als dit werd vergeleken met tripeltherapie bestaande uit een PPI, amoxicilline en claritromycine en als de tripeltherapie 7 of 10 dagen werd gegeven. Echter is de bewijskracht van deze studies ook laag, waardoor er geen duidelijke conclusies kunnen worden getrokken. Er werden geen studies geïncludeerd die de belangrijke uitkomstmaten antibioticaresistentie en kosteneffectiviteit rapporteerden.

Er zijn voor- en nadelen van het behandelen van een H. pylori-infectie bij kinderen.

Het primaire doel is het behandelen van de klachten en complicaties, die zijn veroorzaakt door de infectie met H. pylori. Verder zijn potentiële voordelen van een eradicatie de preventie van toekomstige complicaties zoals het ontstaan van een ulcus, atrofie of metaplasie, MALT- lymfoom en maagkanker. Echter is het risico bij kinderen om een ulcus pepticum te ontwikkelen laag en het risico op ontstaan van ernstige complicaties zeer laag in Nederland en Europa (Kori, 2018). Een ander voordeel van het behandelen kan zijn de angst van ouders voor de consequenties van het “niet behandelen” te reduceren.

Nadelen van het behandelen zijn de toenemende antibiotica-resistentie, mogelijke bijwerkingen van antibiotica en hun negatieve invloed op het microbioom. Ook mee te nemen in de overweging en een potentiele nadelen zijn het risico op falen van de behandeling en hiermee de noodzaak om opnieuw te behandelen en het risico op een re-infectie. De laatste tijd wordt ook een potentiële beschermende werking van H. pylori op chronische ziekten in kinderen bediscussieerd, dit is echter nog niet voldoende onderzocht.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Als de H. pylori stam gevoelig is voor claritromycine kan met patiënten en/of hun verzorgers besproken worden of zij een voorkeur hebben voor tripeltherapie of sequentiële therapie. Hierbij kan worden benoemd dat op basis van de huidige literatuur de ene therapie niet boven de andere therapie te prefereren is als er wordt gekeken naar effectiviteit. Het voordeel van sequentiële therapie is de kortere behandelduur van 10 dagen ten opzichte van 14 dagen bij tripeltherapie. Echter, is het antibioticaschema complexer wat de therapietrouw nadelig kan beïnvloeden. Hierbij moet besproken worden dat een lage therapietrouw geassocieerd is met een verminderde effectiviteit en daardoor een grotere kans op de noodzaak om opnieuw te moeten behandelen. Een ander nadeel van sequentiële therapie is de blootstelling aan 3 verschillende antibiotica in plaats van 2 antibiotica bij tripeltherapie. Dit kan nadelige effecten hebben op het darmmicrobioom en het risico op andere antibiotica-geassocieerde bijwerkingen vergroten.

Daarnaast kan in overleg met patiënten en/of hun verzorgers worden overwogen om bismut toe te voegen aan de eradicatietherapie. Met name bij een re-infectie of penicillineallergie in combinatie met een onbekende of resistentie claritromycine gevoeligheidsbepaling wordt het toevoegen van bismut aanbevolen om de effectiviteit van de eradicatietherapie te vergroten. Aangezien bismut niet wordt vergoed dient deze beslissing samen met patiënt en/of hun verzorgers te worden gemaakt.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er werd geen literatuur gevonden over de kosteneffectiviteit van de verschillende behandelstrategieën.

De gemiddelde kosten voor een tripelbehandeling met metronidazol liggen lager in vergelijking met claritromycine. De precieze kosten zijn echter afhankelijk van de fabrikant (medicijnkosten.nl).

Bismut is niet verkrijgbaar in de Nederlandse apotheken. Het is wel mogelijk om bismut te importeren vanuit de internationale apotheek. Hiervoor is een artsenverklaring nodig, deze is te vinden op de website: https://www.igj.nl/zorgsectoren/geneesmiddelen/beschikbaarheid-van-geneesmiddelen/leveren-op-artsenverklaring. De kosten voor bismut liggen op dit moment bij €19,58 per 50 capsules van 120 mg. Deze kosten worden op dit moment niet vergoed door de Nederlandse zorgverzekeringen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De verlenging van de therapieduur van 7 naar 14 dagen kan de therapietrouw nadelig beïnvloeden. Het is hierbij belangrijk dat de behandelend arts de tijd neemt om het belang van de therapietrouw uit te leggen in het consult (denk aan voordelen van geslaagde behandeling en het risico op re-infectie en opnieuw behandelen).

De verschillende antibiotische behandelschema’s (tripel-, quadrupel- en sequentiële therapie) kunnen door de patiënten en hun ouders/verzorgers als ingewikkeld worden ervaren. Zorg er daarom, samen met de apotheek, voor dat de patiënt en ouders/verzorgers een duidelijk schema meekrijgen met daarop de instructies voor het gebruik van elk middel op verschillende tijdstippen van de dag. Een andere optie is om aan de apotheek te vragen een ‘baxterrol’ met de medicijnen voor twee weken aan de patiënt en ouders/verzorgers mee te geven. Aangezien het antibiotische schema van sequentiële therapie complexer is in vergelijking met tripeltherapie, heeft deze therapie niet de voorkeur in verband met het risico op een lagere therapietrouw en daarmee een negatief effect op de antibioticaresistentie.

Het implementeren van bismut in de eradicatietherapie van H. pylori bij kinderen wordt belemmerd doordat dit middel niet wordt vergoed door de Nederlandse zorgverzekeringen. Het is mogelijk om bismut te importeren waarbij de patiënt en ouders/verzorgers de kosten zelf dienen te betalen. Echter kan dit leiden tot ongelijkheid in behandeling.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De effectiviteit van een eradicatietherapie neemt af als de H. pylori stam resistent is tegen één van de gebruikte antibiotica. In de afgelopen twee decennia is de antibioticaresistentie, met name tegen claritromycine, wereldwijd en ook in Nederland toegenomen. De literatuur over resistentie tegen claritromycine en metronidazol bij kinderen met een H. pylori-infectie in Nederland is beperkt en gedateerd. In de periode van 2000–2009 bedroeg de resistentie tegen claritromycine 6.5-7.2% en tegen metronidazol 10.4-11.7% (n = 72) (Mourad-Baars, 2014). Twee recentere studies bij volwassenen laten echter een grote stijging zien in resistentiecijfers sinds het jaar 2010.

Het Leiden Universitair Medisch Centrum deed in de periode van 2006–2015 onderzoek naar de resistentie tegen metronidazol en claritromycine bij 707 volwassenen met een H. pylori-infectie (vastgesteld middels een kweek). Voor claritromycine werd er een toename in resistentie gezien van 9.8% in de periode 2006–2010 naar 18.1% in de periode 2011–2015. Een stijging van 20.7% naar 23.3% werd ook waargenomen voor metronidazol tussen deze twee periodes (Ruiter, 2017). De studie van Veenendaal en collega’s analyseerde H. pylori resistentie data, verkregen uit 16 Nederlandse microbiologische centra in de periode 2010–2020. Hierbij werd tussen 2010 - 2019 een sterke toename gezien in de resistentie tegen claritromycine (van 7% naar 40%) en metronidazol (14% tot 45%) (Veenendaal, 2022). Er is een verwachting dat de resistentiecijfers onder kinderen in Nederland met een H. pylori-infectie ook zijn toegenomen. Het empirische gebruik van claritromycine wordt aanbevolen als de resistentie minder dan 15% bedraagt (Homan, 2024). Daarom wordt in deze geüpdatete module aanbevolen om eerst de gevoeligheid van H. pylori voor claritromycine te testen (zie module 3) en de keuze voor de eradicatietherapie hierop te baseren.

Het wordt niet aanbevolen om standaard de resistentie tegen metronidazol te testen (Homan, 2024). De reden hiervoor is dat in vitro resistentie niet goed correleert met in vivo resistentie. Daarnaast werd in een recente Europese multicenter studie aangetoond dat bij metronidazol resistentie (in vitro) tripeltherapie met metronidazol voor 14 dagen nog steeds succesvol kon zijn voor eradicatie van H. pylori bij kinderen (Homan, 2024; Le Thi 2023).

In verband met de vieze smaak is therapietrouw een groter probleem bij metronidazol dan bij claritromycine. Aan de andere kant is metronidazol goedkoper dan claritromycine. Concluderend is het ene medicijn niet goed te prefereren boven het andere als de H. pylori stam gevoelig is voor claritromycine.

Sequentiële therapie gedurende 10 dagen (5 dagen PPI en amoxicilline, gevolgd door 5 dagen metronidazol + claritromycine) kan een alternatief zijn voor de tripeltherapie bij een gevoeligheid voor claritromycine. De gepoolde resultaten van de beschikbare literatuur bij kinderen lieten zien dat sequentiële therapie even effectief is als tripeltherapie met een behandelduur van 14 dagen (Habib, 2013; Horvath, 2012; Huang, 2013; Iwanczak, 2016; Rosu, 2022). Ondanks de kortere behandelduur van sequentiële therapie, is de werkgroep van mening dat deze niet de voorkeur heeft boven tripeltherapie vanwege de blootstelling aan drie verschillende antibiotica en de complexiteit van het behandelschema. Dit kan namelijk leiden tot een lagere therapietrouw en de antibioticaresistentie negatief beïnvloeden. Daarnaast moet rekening worden gehouden met de negatieve effecten op het darmmicrobioom en het risico op bijwerkingen.

In de Internationale richtlijn (Homan, 2024) wordt voor een nog betere effectiviteit bismut-quadrupel therapie (bismut, PPI, amoxicilline en metronidazol) als alternatief aanbevolen in het geval van een onbekende resistentiebepaling of wanneer de H. pylori stam resistent is tegen claritromycine. Daarnaast wordt deze quadrupel therapie aanbevolen bij penicillineallergie in combinatie met claritromycineresistentie (Homan, 2024). Echter tot op heden is bismut niet verkrijgbaar in Nederland. Wegens de toegenomen antibioticaresistentie en de bewezen effectiviteit van bismut-eradicatietherapie bij een H. pylori-infectie, is de werkgroep van mening dat bismut beschikbaar zou moeten komen in Nederland. Vanwege het niet beschikbaar zijn van bismut in Nederland en het daardoor ontbreken van doseringen in het Kinderformularium is hieronder een doseringstabel (Tabel 1 – Dosering bismut subcitraat) opgenomen zoals in de ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN guideline uit 2024 (Homan 2024) aanbevolen:

Tabel 1 - Dosering bismut subcitraat

|

|

Lichaamsgewicht (kg) |

Dosering ochtend; middag; avond |

|

Bismut subcitraat |

15-24 |

60 mg; 60 mg; 60 mg |

|

|

25-34 |

120 mg; 60 mg; 60 mg |

|

|

35-49 |

120 mg; 120 mg; 120 mg |

|

|

>50 |

180 mg; 120 mg; 120 mg |

Het toevoegen van probiotica aan de eradicatietherapie kan mogelijk een positief effect hebben. Zo lijkt de kans op succesvolle eradicatie met 10% toe te nemen en de kans op gastro-intestinale bijwerkingen af te nemen als naast de standaard tripel therapie gelijktijdig probiotica worden toegediend (Fang, 2019; Lü, 2016; Szajewska, 2023). Een meta-analyse (5 studies; 484 kinderen) liet zien dat suppletie met Lactobacillus de incidentie van diarree significant verminderde (Fang, 2019). De ESPGHAN position paper (Szajewska, 2023) beschrijft dat suppletie met Saccharomyces boulardii het eradicatiesucces en gastro-intestinale bijwerkingen positief kan beïnvloeden bij kinderen met een H. pylori-infectie. Het bewijs is echter beperkt en gebaseerd op een klein aantal studies met ook heterogeniteit in dosis, duur en type probiotica. Hierdoor kunnen wij, op dit moment, het geven van specifieke probiotica (nog) niet aanbevelen als onderdeel van de eradicatiebehandeling.

Het wordt aanbevolen om zes tot acht weken na beëindigen van de therapie het succes van de behandeling te testen door middel van een non-invasieve test (feces-antigeentest of UBT, zie module Testen op feces en module Serologie volbloed/speeksel/urine en ureum-ademtest voor de non-invasieve testen). Test niet eerder dan zes weken in verband met het risico op een fout-negatieve uitslag en niet later dan acht weken vanwege het risico op re-infectie. Voor zowel de feces-antigeentest en de UBT bestaat er een kans op fout-negatieve uitslagen ten gevolge van de eradicatietherapie. Wacht daarom tot ten minste twee weken na stoppen van PPI’s en vier weken na stoppen van antibiotica en bismut voor het inzetten van de non-invasieve test. Wanneer PPI’s bij een patiënt niet gestaakt kunnen worden, overweeg dan om te wisselen naar H2-antagonisten alvorens het succes van de eradicatietherapie te evalueren (Homan, 2024). In het geval van een gefaalde eradicatietherapie wordt een tweede behandeling geadviseerd, zoals weergegeven in de tabel in de aanbevelingen. Het kan nuttig zijn om te evalueren of er een oorzaak was voor het falen van de behandeling zoals matige therapietrouw, bijwerkingen, geen resistentiebepaling verricht of niet adequaat gedoseerd. Er kan worden overwogen om opnieuw een gastroduodenoscopie met biopten te verrichten om de gevoeligheid van H. pylori te bepalen, met name bij twee gefaalde eradicaties ondanks adequate therapietrouw.

In tegenstelling tot de volwassen richtlijnen (Malfertheiner, 2022), wordt antibiotische behandeling met fluorochinolonen en rifabutine niet standaard aanbevolen als “rescue” therapie in verband met de beperkte literatuur bij kinderen.

In de toekomst komen mogelijk nieuwe zuurremmers beschikbaar: potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs). Deze lijken in onderzoeksverband het eradicatiepercentage te verbeteren, met name bij patiënten met resistente infecties. Deze zijn echter voor de klinische praktijk nog niet beschikbaar.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Over the past two decades, an increasing resistance of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) to clarithromycin and metronidazole has been observed, which are included in the eradication therapy used in children (Ruiter, 2017; Veenendaal, 2022). The increasing resistance contributes to a reduced effectivity of the eradication therapy (Graham, 2010; Homan, 2024). This shows the need for renewed recommendations regarding antibiotic treatment regimens, such as sequential therapy and quadrupel therapy, and/or extension of the duration of therapy. The recommendations in this updated module are based on the resistance determinations and prescription authorisation in the Dutch practice.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Low GRADE |

Sequential therapy might be more effective in eradicating H. pylori-infections in children, compared to standard triple therapy.

Sources: Habib, 2013; Horvath, 2012; Huang, 2013; Iwanczak, 2016; Rosu, 2022. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found for the effect of sequential therapy on antibiotic resistance when compared to standard triple therapy in children with H. pylori-infections.

|

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found on cost-effectiveness for sequential therapy when compared to standard triple therapy in children with H. pylori-infections.

|

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Horvath (2012) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the evidence for sequential therapy compared with triple therapy on H. pylori eradication rates in children.

The literature search was performed until May 2012 in the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE and EMBASE databases. Ten studies were included in the review and meta-analysis, but abstracts were only available of five studies. In general, standard triple therapy consisted of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and two or three antibiotics, mostly including clarithromycin, for a duration of five to 14 days. Sequential therapy consisted of a PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and amoxicillin administered for the first five or seven days, and then a PPI and two antibiotics administered for the next five or seven days. A total of 857 participants were included in the literature analysis and most studies were performed in Europe. Antibiotic resistance rates were not reported in the review. Primary outcome was H. pylori eradication rate, measured using generally accepted measures (13C-urea breath test, histopathology, or rapid urease test), and secondary outcomes were adverse effects and compliance. The length of follow-up varied between four and eight weeks, and incomplete outcome data varied from 0% to 26%. The authors performed risk of bias assessments, which resulted in unclear or high risk for the most studies.

Habib (2013) performed a single-center RCT in the Middle East to investigate the efficacy of a sequential or standard eradication regimen in children with H. pylori-infection. Eighteen boys between 12 and 15 years were included in the study, of which nine received standard eradication therapy consisting of rabeprazole 20 mg, clarithromycin 250 mg and amoxicillin 500 mg each administered orally twice daily for 10 days. The other nine received sequential eradication therapy consisting of rabeprazole 20 mg and amoxicillin 500 mg for 5 days, followed by rabeprazole 20 mg clarithromycin 250 mg and tinidazole 500 mg for another 5 days, each administered orally twice daily. The mean age and resistance rates are not reported in the study. Primary outcome was H. pylori eradication rate, measured using urea breath test, and the secondary outcome was serum ferritin. Follow-up length was six weeks, and two (22%) patients were lost to follow-up due to poor compliance.

Huang (2013) performed a prospective, multicenter, open-label RCT in China to assess the effectiveness of 10-day sequential therapy and standard triple therapy in children with H. pylori-infection. A total of 360 patients were included in three study arms. 118 children received sequential therapy, consisting of omeprazole (0.8–1.0 mg/kg/d) plus amoxicillin (30 mg/kg/d) for the first 5 days, followed by omeprazole (0.8–1.0 mg/kg/d), clarithromycin (20 mg/kg/d) and metronidazole (20 mg/kg/d) for the remaining 5 days. 118 children received standard triple therapy consisting of omeprazole (0.8–1.0 mg/kg/d), amoxicillin (30 mg/kg/d) and clarithromycin (20 mg/kg/d) for 7 and 124 children received this for 10 days. Mean age was 8.7 ± 4.1 in the sequential therapy group, 9.7 ± 3.8 in the seven days triple therapy group, and 7.9 ± 3.4 in the ten days triple therapy group. The groups were comparable at baseline. Resistance rates were not reported in the article. Primary outcome was H. pylori eradication rate, measured using H. pylori stool antigen test, and the secondary outcomes were adverse events and gastrointestinal symptom relief, measured using a daily reporting card. Follow-up length was four weeks, and 11 (9.3%) patients were lost to follow-up in the sequential therapy group, 15 (12.7%) patients in the seven days triple therapy group, and 16 (12.9%) patients in the ten days triple therapy group.

Iwanczak (2016) performed a prospective RCT in Poland to investigate the efficacy of ten-day sequential therapy compared with seven-day standard therapy in children with H. pylori-infection. A total of 69 patients were included in three study arms. 23 children received sequential therapy consisting of omeprazole (1 mg/kg/d) and amoxicillin (50 mg/kg/d) for 5 days followed by 5 days the treatment with omeprazole (1 mg/kg/d), clarithromycin (15 mg/kg/d) and metronidazole (20 mg/kg/d). 23 children received standard therapy consisting of seven days omeprazole (1 mg/kg/d), amoxicillin (50 mg/kg/d), and clarithromycin (15 mg/kg/d). 23 children received standard therapy consisting of seven days omeprazole (1 mg/kg/d), amoxicillin (50 mg/kg/d), and metronidazole (20 mg/kg/d). Age ranged between five and 17, and the groups were comparable at baseline. Resistance of H. pylori strains was reported, in total nine strains were clarithromycin resistant, 12 strains were metronidazole resistant, no strains were amoxicillin resistant, and one strain was both clarithromycin and metronidazole resistant. Primary outcome was H. pylori eradication rate, measured using the culture of biopsy specimens sampled from the stomach, and secondary outcomes were adverse events and compliance. Length of follow-up was six to eight weeks after completion of the treatment, and no patients were lost to follow-up.

Rosu (2022) performed a single-center prospective comparative study in Romania to assess the compare the effectiveness of sequential therapy, standard triple therapy using metronidazole and standard triple therapy using clarithromycin in children with H. pylori-infection. A total of 149 patients were included in three study arms. 38 children received sequential therapy consisting of PPI and amoxicillin 5 days followed by PPI, clarithromycin, and metronidazole for 5 days. 62 patients received PPI, amoxicillin, and metronidazole for 14 days and 49 patients received PPI, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin for 14 days. Doses were based on body weight, see table 1. Mean age was 13.20 ± 3.30 years and 69% was female. Resistance rates were unknown. Primary outcome was H. pylori eradication rate, measured using fecal antigen testing, and the secondary outcomes were side effects and compliance. Length of follow-up was four to eight weeks from the end of the treatment, and no patients were lost to follow-up.

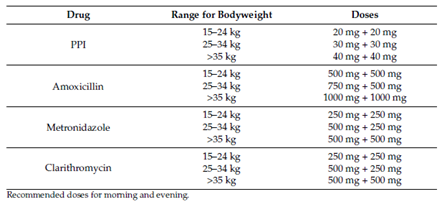

Table 1. Standard PPI and antibiotic prescription doses for body weight used in the study of Rosu (2022). Table is directly retrieved from the article of Rosu (2022)

Results

Treatment efficacy

All five included studies reported treatment efficacy, in terms of H. pylori eradication rate.

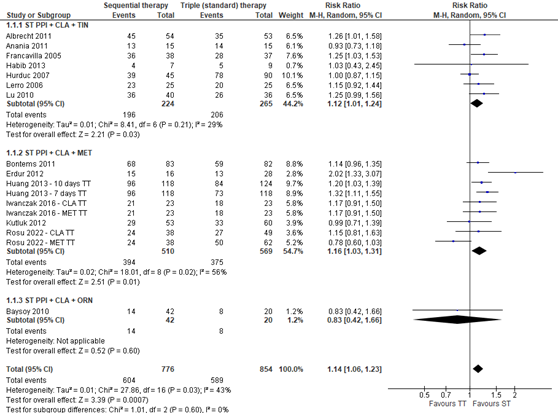

The review of Horvath (2012) performed a meta-analysis and found a RR of 1.14 (95%CI 1.06-1.23). Data from the additional four studies was added to the meta-analysis and additional subgroup analysis were performed.

Pooling of all studies shows that sequential therapy significantly increases the risk on H. pylori eradication (RR 1.14; 95%CI 1.06 to 1.23), see figure 1. This means that sequential therapy is more effective than standard triple therapy. However, this risk ratio is not clinically important. Heterogeneity of the data is moderate (I2 = 43%). The absolute risk difference is 10% (95%CI 0.04 to 0.16) in favor of the sequential therapy. The Number Needed to Treat (NNT) is 10, which means that 10 patients need to be treated with sequential therapy, in order to eradicate H. pylori in one patient.

Figure 1. Forest plot of the studies reporting eradication rates for sequential versus standard triple therapy in children with H. pylori-infections. The studies of Huang (2013), Iwanczak (2016), and Rosu (2022) were three arm studies with two control groups

CLA: clarithromycin, MET: metronidazole, ST: sequential therapy, TT: triple therapy

Subgroup analysis was performed to determine the effect of tinidazole, metronidazole or ornidazole used in the second five days of sequential therapy on eradication rates. Only Baysoy (2010) used ornidazole. The difference between the subgroups receiving tinidazole or metronidazole is minimal, see figure 2. The risk ratios remain not clinically important. The heterogeneity in the data in the subgroup of patients receiving metronidazole is larger than in the subgroup receiving tinidazole, I2 = 56% and I2 = 29% respectively. The NNT in the subgroup receiving tinidazole is 10 and in the subgroup receiving metronidazole 8. This means that less patients need to be treated with sequential therapy containing metronidazole to eradicate H. pylori in one patient, compared with sequential therapy containing tinidazole.

Figure 2. Forest plot with subgroup analysis of the efficacy on eradication rates in studies using sequential therapy containing tinidazole and sequential therapy containing metronidazole in children with H. pylori-infections. Omeprazole was used as PPI in all studies except Baysoy (2010), Erdur (2012), and Kutluk (2012), which used lansoprazole, and Habib (2013), which used rabeprazole. The studies of Huang (2013), Iwanczak (2016), and Rosu (2022) were three arm studies with two control groups

CLA: clarithromycin, MET: metronidazole, ORN: ornidazole, PPI: proton pump inhibitor, ST: sequential therapy, TIN: tinidazole, TT: triple therapy

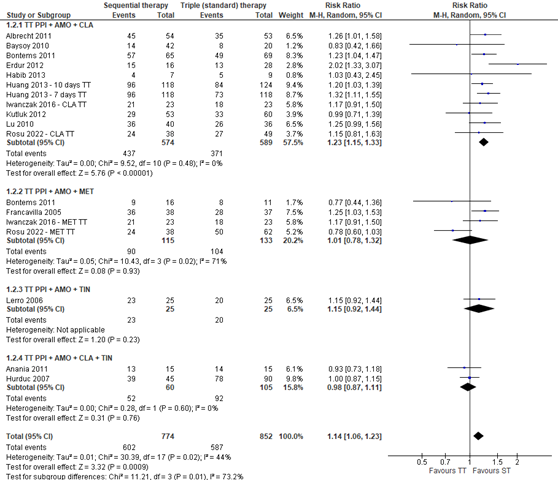

Another subgroup analysis was performed to determine the effect of the additional antibiotic(s) next to amoxicillin in standard triple therapy, see figure 3. The subgroup analysis shows that only triple therapy containing clarithromycin has a significant risk ratio (RR 1.23; 95%CI 1.15 to 1.33), in comparison with triple therapy containing metronidazole, tinidazole, and both clarithromycin and tinidazole. This risk ratio is clinically important. This means that sequential therapy is more effective and will also be noticeable for patients in eradicating H. pylori when compared with triple therapy using clarithromycin, compared with triple therapy containing metronidazole, tinidazole, or both clarithromycin and tinidazole. Heterogeneity in this data is not present (I2 = 0%). The NNT is 6, which means that six patients need to be treated with sequential therapy, compared to triple therapy with clarithromycin, to eradicate H. pylori in one patient.

Figure 3. Forest plot with subgroup analysis of the efficacy on eradication rates in studies using different types of standard triple therapy in children with H. pylori-infections. Omeprazole was used as PPI in all studies except Baysoy (2010), Erdur (2012), and Kutluk (2012), which used lansoprazole, and Habib (2013), which used rabeprazole. The studies of Bontems (2011), Huang (2013), Iwanczak (2016), and Rosu (2022) were three arm studies with two control groups. The data of Bontems (2011), included in Horvath (2012), were derived from the individual study

AMO: amoxicillin, CLA: clarithromycin, MET: metronidazole, ORN: ornidazole, PPI: proton pump inhibitor, ST: sequential therapy, TIN: tinidazole, TT: triple therapy

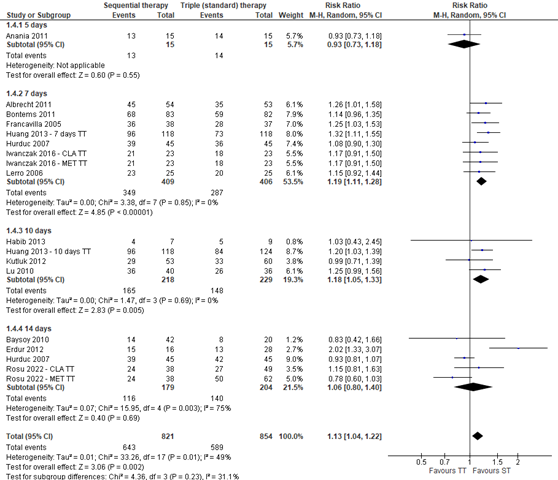

Lastly, subgroup analysis was performed to determine the effect of the duration of standard triple therapy. This analysis was also performed by Horvath (2012), who found that sequential therapy compared with 7-day standard triple therapy resulted in a higher eradication rate (RR 1.17; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.28). No significant effect was found when sequential therapy was compared with 5-day, 10-day, or 14-day triple therapy. When combining the data from Horvath (2012) with the additional studies, sequential therapy is effective when compared to 7-days and 10-days standard triple therapy (see figure 4). No difference is found with 5-days and 14-days standard triple therapy. These risk ratios are clinically important, which means that sequential therapy is more effective and will also be noticeable for patients in eradicating H. pylori when compared with 7-day and 10-day triple therapy.

Figure 4. Forest plot with subgroup analysis of the efficacy on eradication rates in studies using different durations of standard triple therapy in children with H. pylori-infections. The studies of Huang (2013), Hurduc (2007), Iwanczak (2016), and Rosu (2022) were three arm studies with two control groups

ST: sequential therapy, TT: triple therapy

Huang (2013) reported on gastrointestinal symptom relief measured using a daily reporting card. No differences were found in symptom relief between sequential therapy (93.5% relief), 7-day triple therapy (85.4% relief), and 10-day triple therapy (95.6% relief).

Antibiotic resistance

No studies reported on antibiotic resistance.

Cost-effectiveness

No studies reported on cost-effectiveness.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure treatment efficacy was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and conflicting results (inconsistency) to LOW.

No evidence was found for the outcome measure antibiotic resistance.

No evidence was found for the outcome measure cost-effectiveness.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the benefits and risks of sequential therapy compared with triple therapy children with H. pylori-infection?

| P: | Children (0-18 years old) with a diagnosed H. pylori-infection |

| I: |

Sequential therapy |

| C: |

Standard therapy (PPI + amoxicillin + metronidazole or clarithromycin) |

| O: |

Treatment success/failure, antibiotic resistance, cost effectiveness |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered treatment efficiency as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and antibiotic resistance and cost effectiveness as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined RR < 0.80 and RR > 1.25 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 13th of October 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 81 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic review or RCTs, helicobacter pylori, children, and quadruple therapy. Nineteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 14 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five studies were included.

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Ali Habib HS, Murad HA, Amir EM, Halawa TF. Effect of sequential versus standard Helicobacter py-lori eradication therapy on the associated iron deficiency anemia in children. Indian J Pharma-col. 2013 Sep-Oct;45(5):470-3. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.117757. PMID: 24130381; PMCID: PMC3793517.

- Chey WD, Mégraud F, Laine L, López LJ, Hunt BJ, Howden CW. Vonoprazan Triple and Dual Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Infection in the United States and Europe: Randomized Clinical Trial. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):608-619. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.055. Epub 2022 Jun 6. PMID: 35679950.

- Fang, HR., Zhang, GQ., Cheng, JY. et al. Efficacy of Lactobacillus-supplemented triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in children: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pediatr 178, 7–16 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-018-3282-z

- Graham DY, Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut. 2010 Aug;59(8):1143-53. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.192757. Epub 2010 Jun 4. PMID: 20525969.

- Horvath A, Dziechciarz P, Szajewska H. Meta-analysis: sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012 Sep;36(6):534-41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05229.x. Epub 2012 Jul 25. PMID: 22827718.

- Huang J, Zhou L, Geng L, Yang M, Xu XW, Ding ZL, Mao M, Wang ZL, Li ZL, Li DY, Gong ST. Random-ised controlled trial: sequential vs. standard triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese children-a multicentre, open-labelled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013 Nov;38(10):1230-5. doi: 10.1111/apt.12516. Epub 2013 Oct 5. PMID: 24117692.

- Iwańczak BM, Borys-Iwanicka A, Biernat M, Gościniak G. Assessment of Sequential and Standard Triple Therapy in Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Children Dependent on Bacte-ria Sensitivity to Antibiotics. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2016 Jul-Aug;25(4):701-8. doi: 10.17219/acem/38554. PMID: 27629844.

- Jones NL, Koletzko S, Goodman K, Bontems P, Cadranel S, Casswall T, Czinn S, Gold BD, Guarner J, Elitsur Y, Homan M, Kalach N, Kori M, Madrazo A, Megraud F, Papadopoulou A, Rowland M; ESPGHAN, NASPGHAN. Joint ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN Guidelines for the Management of Heli-cobacter pylori in Children and Adolescents (Update 2016). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 Jun;64(6):991-1003. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001594. PMID: 28541262.

- Kanu JE, Soldera J. Treatment of Helicobacter pyloriwith potassium competitive acid blockers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2024 Mar 7;30(9):1213-1223. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i9.1213. PMID: 38577188; PMCID: PMC10989498.

- Kori M, Daugule I, Urbonas V. Helicobacter pylori and some aspects of gut microbiota in children. Helicobacter. 2018 Sep;23 Suppl 1:e12524. doi: 10.1111/hel.12524. PMID: 30203591.

- Le Thi TG, Werkstetter K, Kotilea K, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection in paediatric patients in Europe: results from the EuroPedHp registry. Infection. 2023;51(4): 921‐934.

- Lü M, Yu S, Deng J, Yan Q, Yang C, Xia G, Zhou X. Efficacy of Probiotic Supplementation Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Eradication: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS One. 2016

- Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, Rokkas T, Gisbert JP, Liou JM, Schulz C, Gasbarrini A, Hunt RH, Leja M, O'Morain C, Rugge M, Suerbaum S, Tilg H, Sugano K, El-Omar EM; European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report. Gut. 2022 Aug 8:gutjnl-2022-327745. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327745.

- Mourad-Baars PE, Wunderink HF, Mearin ML, Veenendaal RA, Wit JM, Veldkamp KE. Low antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori in The Netherlands. Helicobacter. 2015 Feb;20(1):69-70. doi: 10.1111/hel.12175. Epub 2014 Dec 12. PMID: 25495199.

- Rosu OM, Gimiga N, Stefanescu G, Ioniuc I, Tataranu E, Balan GG, Ion LM, Plesca DA, Schiopu CG, Diaconescu S. The Effectiveness of Different Eradication Schemes for Pediatric Helicobacter pylori Infection-A Single-Center Comparative Study from Romania. Children (Basel). 2022 Sep 14;9(9):1391. doi: 10.3390/children9091391. PMID: 36138699; PMCID: PMC9497595.

- Ruiter R, Wunderink HF, Veenendaal RA, Visser LG, de Boer MGJ. Helicobacter pylori resistance in the Netherlands: a growing problem? Neth J Med. 2017 Nov;75(9):394-398. PMID: 29219812.

- Veenendaal RA, Woudt SHS, Schoffelen AF, de Boer MGJ, van den Brink G, Molendijk I, Kuijper EJ. Verontrustende toename van antibioticaresistentie bijHelicobacter pylori [Important rise in antibiotic resistance rates inHelicobacter pyloriin the Netherlands]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2022 Mar 14;166:D6434. Dutch. PMID: 35499541.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Horvath, 2012

[individual study characteristics deduced from [Horvath, 2012]]

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to May 2012

A: Albrecht, 2011 B: Anania, 2011 C: Baysoy, 2010 D: Bontems, 2011 E: Erdur, 2012 F: Francavilla, 2005 G: Hurduc, 2007 H: Kutluk, 2012 I: Lerro, 2006 J: Lu, 2012.

Study design: two-armed RCTs (except Hurduc 2007)

Setting and Country: The studies were undertaken in European countries, such as Belgium, France, Italy, Poland, Romania, and Turkey, or in Asia (China). Except for one multi-centre trial, the included studies were single-centre trials.

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: No personal and funding interests |

Inclusion criteria SR: (i) participants: children aged 0–18 years and H. pylori-infected, as assessed using generally accepted methods [e.g. culture, the13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT), histopathology, or the rapid urease test], (ii) intervention: sequential therapy, (iii) comparison: standard triple H. pylori eradication therapy, (iv) the primary outcome measure: the rate of H. pylori eradication, which had to be confirmed by a negative13C-UBT or other generally accepted method at least 4 weeks after treatment and (v) the secondary outcome measures: the frequencies of adverse effects (overall and specific, including diarrhoea, taste disturbance, nausea, vomiting, bloating, loss of appetite, abdominal pain and constipation), compliance and the need for discontinuation of the H. pylori therapy.

Exclusion criteria SR: NR

10 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline

N, age A: 107 patients, age 3-18 years B: 30 patients, age 4.8-16.7 years C: 62 patients, age 4-18 years D: 165 patients, age median 10.0 and 11.1 years E: 44 patients, age 4-17 years F: 75 patients, age 3.3-16 years G: 135 patients, age 3-18 years H: 113 patients, age 3-18 years I: 50 patents, age median 11.9 and 12.3 years J: 76 patients, age 10.2 ± 2.8 and 10.7 ± 2.4 years

Groups comparable at baseline? NR |

A: Sequential therapy of a PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and amoxicillin administered for the first 5 days and then a PPI and two antibiotics administered for the next 5 days. B: Sequential therapy of a PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and amoxicillin administered for the first 5 days and then a PPI and two antibiotics administered for the next 5 days. C: Sequential therapy of a PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and amoxicillin administered for the first 5 days and then a PPI and two antibiotics administered for the next 5 days. D: Sequential therapy of a PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and amoxicillin administered for the first 5 days and then a PPI and two antibiotics administered for the next 5 days. E: Sequential therapy of a PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and amoxicillin administered for the first 7 days and then a PPI and two antibiotics administered for the next 7 to 30 days. F: Sequential therapy of a PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and amoxicillin administered for the first 5 days and then a PPI and two antibiotics administered for the next 5 days. G: Sequential therapy of a PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and amoxicillin administered for the first 5 days and then a PPI and two antibiotics administered for the next 5 days. H: Sequential therapy of a PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and amoxicillin administered for the first 5 days and then a PPI and two antibiotics administered for the next 5 days. I: Sequential therapy of a PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and amoxicillin administered for the first 5 days and then a PPI and two antibiotics administered for the next 5 days. J: Sequential therapy of a PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and amoxicillin administered for the first 5 days and then a PPI and two antibiotics administered for the next 5 days.

See figure 1 for more details.

|

A: Triple therapy consisting of PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and two antibiotics. Duration of triple therapy was 7 days. B: Triple therapy consisting of PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and three antibiotics. Duration of triple therapy was 5 days. C: Triple therapy consisting of PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and two antibiotics. Duration of triple therapy was 14 days. D: Triple therapy consisting of PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and two antibiotics. Duration of triple therapy was 7 days. E: Triple therapy consisting of PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and two antibiotics. Duration of triple therapy was 14 days. F: Triple therapy consisting of PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and two antibiotics. Duration of triple therapy was 7 days. G: Triple therapy consisting of PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and three antibiotics. Duration of triple therapy was 14 days. H: Triple therapy consisting of PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and two antibiotics. Duration of triple therapy was 10 days. I: Triple therapy consisting of PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and two antibiotics. Duration of triple therapy was 7 days. J: Triple therapy consisting of PPI (omeprazole or lansoprazole) and two antibiotics. Duration of triple therapy was 10 days.

In almost all the trials, clarithromycin was one of the antibiotics used.

See figure 1 for more details. |

End-point of follow-up: A: 6-8 weeks B: 8 weeks C: 8 weeks D: 8 weeks E: 4 weeks F: 8 weeks G: NR H: 6-8 weeks I: 6 weeks J: 4 weeks

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? A: 4% B: 0% C: 26% D: 9% E: 0% F: 1% G: 0% H: 0% I: 0% J: 7%

|

H. pylori eradication rates Measured using 13C-urea breath test.

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.06–1.23 favouring sequential therapy, n=10. Heterogeneity (I2): 47%.

NNT = 15 (95%CI 8-88).

Only sequential eradication therapy compared with 7-day standard triple therapy resulted in a higher eradication rate (five RCTs, n = 487, RR 1.17, 95% CI 1.07–1.28). No such effect was reported when sequential therapy was compared with 10-day or 14-day triple therapy.

|

Risk of bias (judgement by the authors): A: Low B: Unclear C: High D: High E: High F: High G: Unclear H: Unclear I: Unclear J: High

Only abstracts (no full text) were available from:

Funnel plot is not equally divided. Authors state that there is no publication bias.

Antibiotic resistance rate is not reported in the review or in the evidence table of the review. |

Figure 1. Details of the intervention and control therapies of the studies included in Horvath, 2012. The figure is directly retrieved from Horvath, 2012

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Habib, 2013 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Middle East

Funding and conflicts of interest: This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, (DSR), King Abdulaziz University (KAU), Jeddah, under grant number (332/140/1431). The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

No conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Male children aged 12-15 years, recently diagnosed H. pylori positive; otherwise apparently healthy. They were tested for H. pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody and those positives were subjected to UBT to detect active infection.

Exclusion criteria: Children who consumed acid inhibitors, bismuth compounds or antibiotics during the previous 4 weeks or those with known allergy to antibiotics were excluded.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 9 Control: 9

Important prognostic factors: NR

Groups comparable at baseline? NR |

Sequential eradication therapy consisting of rabeprazole 20 mg and amoxicillin 500 mg for 5 days, followed by rabeprazole 20 mg clarithromycin 250 mg and tinidazole 500 mg for another 5 days, each administered orally twice daily.

|

Standard eradication therapy consisting of rabeprazole 20 mg, clarithromycin 250 mg and amoxicillin 500 mg each administered orally twice daily for 10 days.

|

Length of follow-up: 6 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%): 2 (22%) Reasons: poorly compliant

Control: N (%): 0

|

Effectiveness of therapy Measured using the urea breath test: IG: negative 57.1% Positive: 42.9% CG: negative 55.6% Positive: 44.4%

|

Data on serum ferritin not reported here. |

|

Huang, 2013 |

Type of study: Prospective, multicentre, open-label RCT

Setting and country: Four tertiary medical centres in China

Funding and conflicts of interest:

This study was funded in full by Key Projects of the National Science & Technology Pillar Program of China, No. 2007BAI04B02.

No conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: We included children 3–16 years of age who were referred for upper endoscopy and confirmed to have H. pylori infection.

Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded if they had taken proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists or antibiotics in the 4 weeks prior to the study. Patients with known antibiotic allergy, hepatic impairment or kidney failure were also excluded.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 118 Control 7-day: 118 Control 10-day: 124

Important prognostic factors: Age ± SD: I: 8.7 ± 4.1 C 7-day: 9.7 ± 3.8 C 10-day: 7.9 ± 3.4

Sex (boys/girls) I: 71/47 C 7-day: 70/45 C 10-day: 69/55

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Sequential therapy consists of omeprazole (0.8–1.0 mg/kg/d) plus amoxicillin (30 mg/kg/d) for the first 5 days, followed by omeprazole (0.8–1.0 mg/kg/d), clarithromycin (20 mg/kg/d) and metronidazole (20 mg/ kg/d) for the remaining 5 days.

|

Standard triple therapy consists of omeprazole (0.8–1.0 mg/kg/d), amoxicillin (30 mg/kg/d) and clarithromycin (20 mg/kg/d) for 7 or 10 days.

|

Length of follow-up: 4 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%): 11 (9.3%) Reasons: NR

Control 7-days: N (%): 15 (12.7%) Reasons: NR

Control 10-days: N (%): 16 (12.9%) Reasons: NR

|

Eradication rate (effectiveness) Measured by H. pylori stool antigen test: The eradication rate achieved with the sequential therapy was significantly higher than with either the 7-day or 10-day standard triple therapy.

RR sequential therapy to 7-day triple therapy: 1.32 (95% CI, 1.06–1.48)

RR sequential therapy to 10-day triple therapy: 1.20 (95% CI, 1.03–1.39)

GI symptom relief (n (%)) Measured by using daily reporting card: Sequential therapy: 100 (93.5%) Triple therapy 7-days: 88 (85.4%) Triple therapy 10-days: 100 (95.6%) No statistical difference. |

Data on adverse events not reported here.

Resistance rates not reported in the article. |

|

Iwanczak, 2016 |

Type of study: Prospective RCT Setting and country: Poland

Funding and conflicts of interest: The study was funded by the grant No. ST-821.

No conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Children with H. pylori infection who had not been eradicated earlier.

Exclusion criteria: Receiving antibiotics or PPI for 4 weeks before the beginning of the study, and those in whom hypersensitivity to antibiotics was observed.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 23 Control MET: 23 Control CLA: 23

Important prognostic factors: Median age (range): I: 12.4 (5-17) years C MET: 10.2 (5-15) years C CLA: 12.1 (5-17) years

Sex: I: 35% M C MET: 52% M C CLA: 61% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Omeprazole and amoxicillin for 5 days followed by 5 days the treatment with omeprazole, clarithromycin and metronidazole

1–5 days: PPI-omeprazole 1 mg/kg of body weight per 24 h, max 20 mg/24 h twice daily amoxicillin 50 mg/kg of body weight per 24 h, max 1000 mg/24 h twice daily

6–10 days: PPI-omeprazole 1 mg/kg of body weight per 24 h, max 20 mg/24 h twice daily clarithromycin 15 mg/kg of body weight per 24 h, max 500 mg/24 h twice daily metronidazole 20 mg/kg of body weight per 24 h, max 500 mg/24 h twice daily |

Group 1: 7 days with omeprazole, amoxicillin and clarithromycin

Group 2: 7 days with omeprazole, amoxicillin and metronidazole

|

Length of follow-up: 6-8 weeks after completion of the treatment

Loss-to-follow-up: 0

|

Resistant strains (n(%)) Measured using the culture of biopsy specimens sampled from the stomach: CLA resistant strains: I: 2 (8.70%) C MET: 3 (13.04%) C CLA: 4 (17.39%)

MET resistant strains: I: 4 (17.39%) C MET: 4 (17.39%) C CLA: 4 (17.39%)

AMO resistant strains: All three groups: 0

CLA and MET resistant strains: I: 0 C MET: 0 C CLA: 1 (4.35%)

Treatment eradication (n(%)) Measured using the culture of biopsy specimens sampled from the stomach: Successful rates of eradication: I: 21 (91.3%) C MET: 18 (78.2%) C CLA: 18 (78.2%) All no significant difference.

H. pylori strains susceptible to CLA: I: 19 (90.5%) C MET: 15 (75%) C CLA: 18 (100%) Only significant difference between C MET and C CLA (p=0.023).

H. pylori strains susceptible to MET: I: 18 (94.7%) C MET: 15 (78.9%) C CLA: 14 (77.7%) All no significant difference.

H. pylori strains susceptible to both CLA and MET: I: 16 (94.1%) C MET: 12 (75%) C CLA: 14 (100%) Only significant difference between C MET and C CLA (p=0.044).

CLA resistant strains: I: 2 (100%) C MET: 3 (100%) C CLA: 0

MET resistant strains: I: 3 (75%) C MET: 3 (75%) C CLA: 4 (100%)

CLA and MET resistant strains: All 0.

Treatment eradication rates of C CLA vs I (OR (95%CI)): H. pylori strains susceptible to CLA: 0.21 (95%CI 0.009-4.69)

H. pylori strains susceptible to MET: 5.14 (95%CI 0.51-51.3)

H. pylori strains susceptible to CLA and MET: 0.38 (95%CI 0.014-10.06)

Treatment eradication rates of C MET vs I (OR (95%CI)): H. pylori strains susceptible to CLA: 3.17 (95%CI 0.54-18.7)

H. pylori strains susceptible to MET: 4.8 (95%CI 0.48-47.7)

H. pylori strains susceptible to CLA and MET: 5.33 (95%CI 0.53-54.0) |

Data on adverse events not reported here. |

|

Rosu, 2022 |

Type of study: Prospective comparative study

Setting and country: Single centre study in Romania

Funding and conflicts of interest: No external funding.

No conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Children aged between 6 and 17 years, who performed upper digestive endoscopy for various gastroenterological conditions.

Exclusion criteria: patients under 6 years old and over 18 years, those who received PPI treatment, antibiotics or antibacterial treatment four weeks before the procedure, and patients with associated pathologies, such as Celiac Disease or Crohn’s Disease.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 38 Control MTZ: 62 Control CLR: 49

Important prognostic factors: Age (for whole sample) 6-9 years: 18% 10-14 years: 36% 15-17 years: 47%

Sex (for whole sample) 31% M

Groups comparable at baseline? NR |

According to ESPGHAN guidelines, the prescribed treatment was based on body weight.

Proton pomp inhibitor and amoxicillin 5 days followed by proton pomp inhibitor, clarithromycin, and metronidazole for 5 days.

PPI 15–24 kg 20 mg + 20 mg 25–34 kg 30 mg + 30 mg >35 kg 40 mg + 40 mg Amoxicillin 15–24 kg 500 mg + 500 mg 25–34 kg 750 mg + 500 mg >35 kg 1000 mg + 1000 mg Metronidazole 15–24 kg 250 mg + 250 mg 25–34 kg 500 mg + 250 mg >35 kg 500 mg + 500 mg Clarithromycin 15–24 kg 250 mg + 250 mg 25–34 kg 500 mg + 250 mg >35 kg 500 mg + 500 mg

Recommended doses for morning and evening.

|

According to ESPGHAN guidelines, the prescribed treatment was based on body weight.

C MTZ Proton pomp inhibitor, amoxicillin, and metronidazole for 14 days.

OR

C CLR Proton pomp inhibitor, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin for 14 days.

PPI 15–24 kg 20 mg + 20 mg 25–34 kg 30 mg + 30 mg >35 kg 40 mg + 40 mg Amoxicillin 15–24 kg 500 mg + 500 mg 25–34 kg 750 mg + 500 mg >35 kg 1000 mg + 1000 mg Metronidazole 15–24 kg 250 mg + 250 mg 25–34 kg 500 mg + 250 mg >35 kg 500 mg + 500 mg Clarithromycin 15–24 kg 250 mg + 250 mg 25–34 kg 500 mg + 250 mg >35 kg 500 mg + 500 mg

Recommended doses for morning and evening. |

Length of follow-up: 4-8 weeks or more from the end of the treatment

Loss-to-follow-up: 0

|

Effectiveness (% (n)) Measured using faecal antigen testing: I: 63.15% (24/38) C MTZ: 80.64% (50/62) C CLR: 55.11% (27/49)

|

Authors: Due to unknown resistance of H. pylori to antibiotics and because the determination of antibiotic resistance was not possible, eradication regimens were randomly assigned to patients.

Data on side effects not reported here. |

Risk of bias tables

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

Risk of bias |

|

Horvath, 2012 |

Yes

PICO is clearly formulated. |

Yes

Search period and strategy are described, and CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE were searched. |

No

Characteristics of excluded trials and reasons for exclusion are available on request. |

Yes

Comprehensive evidence table. |

Not applicable

Only RCTs included. |

Yes

Risk of bias is determined, and assessment is described. |

Yes

Studies are comparable and I2 is reported in meta-analysis. |

Yes

Funnel plot is added to supplements. |

Yes

Funding is reported from both individual studies and SR. |

Some concerns |

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Habib, 2013 |

Probably no;

Reason: Randomisation process not described. |

Probably no;

Reason: Randomisation process not described. |

Probably no;

Reason: Blinding not described. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Two patients were lost to follow-up, but this had a lot of impact due to the small sample size. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably no;

Reason: No baseline characteristics described. |

HIGH |

|

Huang, 2013 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: A computer random number generator was used. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization was conducted by an investigator not involved in the study. Sealed envelopes were used. |

Definitely yes:

Reason: Investigators, study coordinators, and patients were blinded. |

Probably yes;

Reason: 10-12% was lost to follow-up, but this was evenly distributed in all groups. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems that could result in bias. |

Some concerns |

|

Iwanczak, 2016 |

Probably no;

Reason: Randomisation process not described. |

Probably no;

Reason: Randomisation process not described. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Only described that physician was blinded. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems that could result in bias. |

HIGH |

|

Rosu, 2022 |

Probably no;

Reason: Randomisation process not described. |

Probably no;

Reason: Randomisation process not described. |

Probably no;

Reason: Blinding not described. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems that could result in bias. |

HIGH |

Table of excluded studies

|

Title |

Year |

Authors |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Ten-day sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in children; a systematic review of randomized controlled trials |

2013 |

He, J. D. and Liu, L. and Zhu, Y. J. |

article in chinese and not accessible |

|

[A 10-day sequential therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in children] |

2012 |

Huang, J. and Gong, S. T. and Ou, W. J. and Pan, R. F. and Geng, L. L. and Huang, H. and He, W. E. and Chen, P. Y. and Liu, L. Y. and Zhou, L. Y. |

article in chinese and not accessible |

|

Clinical effects of different therapeutic regimens for Helicobacter pylori infection in children |

2017 |

Zhu, X. L. and Liu, Z. and Wu, Z. Q. and Li, D. and Jiang, A. P. and Yu, G. X. |

article in chinese and not accessible |

|

Comparison of sequential and standard therapy for helicobacter pylori eradication in children and investigation of clarithromycin resistance |

2012 |

Erdur, B. and Ozturk, Y. and Gurbuz, E. D. and Yilmaz, O. |

retracted article |

|

Effectiveness of sequential v. Standard triple therapy for treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in children in Nairobi, Kenya |

2013 |

Laving, A. and Kamenwa, R. and Sayed, S. and Kimang'a, A. N. and Revathi, G. |

wrong population |

|

Sequential therapy compared with standard triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in children: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial |

2011 |

Albrecht, P. and Kotowska, M. and Szajewska, H. |

in SR |

|

Sequential therapy versus standard triple therapy for helicobacter pylori eradication in children: Any advantage in clarithromycin-resistant strains? |

2014 |

Kutluk, G. and Tutar, E. and Bayrak, A. and Volkan, B. and Akyon, Y. and Celikel, C. and Ertem, D. |

in SR |

|

Sequential therapy versus tailored triple therapies for helicobacter pylori infection in children |

2011 |

Bontems, P. and Kalach, N. and Oderda, G. and Salame, A. and Muyshont, L. and Miendje, D. Y. and Raymond, J. and Cadranel, S. and Scaillon, M. |

in SR |

|

Comparison of multiple treatment regimens in children with Helicobacter pylori infection: A network meta-analysis |

2023 |

Liang, M. and Zhu, C. and Zhao, P. and Zhu, X. and Shi, J. and Yuan, B. |

quality |

|

Joint ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN Guidelines for the Management of Helicobacter pylori in Children and Adolescents (Update 2016) |

2017 |

Jones, N. L. and Koletzko, S. and Goodman, K. and Bontems, P. and Cadranel, S. and Casswall, T. and Czinn, S. and Gold, B. D. and Guarner, J. and Elitsur, Y. and Homan, M. and Kalach, N. and Kori, M. and Madrazo, A. and Megraud, F. and Papadopoulou, A. and Rowland, M. |

guideline |

|

Therapeutic eradication choices in Helicobacter pylori infection in children |

2023 |

Manfredi, M. and Gargano, G. and Gismondi, P. and Ferrari, B. and Iuliano, S. |

narrative review |

|

Treatment of Pediatric Helicobacter pylori Infection |

2022 |

Lai, Hung-Hsiang and Lai, Ming-Wei |

narrative review |

|

Update on peptic ulcers in the pediatric age |

2012 |

Guariso, G. and Gasparetto, M. |

narrative review |

|

Agreement of monoclonal fecal test (amplified IDEA™ hp star™) with the urease breath test, before and after the eradication treatment of h. pylori in children |

2012 |

Albrecht, P. and Kotowska, M. and Miśko, E. and łazowska-Przeorek, I. and Karolewska-Bochenek, K. and Banaszkiewicz, A. and Gawrońska, A. and Banasiuk, M. and Dziekiewicz, M. and Radzikowski, A. |

wrong PICO |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 25-06-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 24-04-2025

Algemene gegevens

Belangrijkste wijzigingen t.o.v. vorige versie: De vorige richtlijn stamde uit 2012, sindsdien zijn de inzichten in knelpunten veranderd, alsmede de stand van wetenschap en het antibioticaresistentiepatroon van infecties met H. pylori. Tevens is er in 2024 een nieuwe internationale richtlijn over H. pylori gepubliceerd door de ESPHGAN/NASPGHAN. Deze richtlijn tracht hier zoveel als mogelijk bij aan te sluiten met inachtneming van de situatie in Nederland.

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kinderen met een verdachte of bevestigde H. pylori-infectie of klachten die hierbij passen.

Werkgroep

- Dr. A. (Angelika) Kindermann, kinderarts MDL, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVK, voorzitter

- Dr. R.W.B. (Renske) Bottema, kinderarts MDL, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, Ede, NVK

- Dr. P.E.C. (Nel) Mourad-Baars, kinderarts MDL n.p., NVK

- Dr. M. (Marianne) Almaç – Linthorst, jeugdarts, CJG Rijnmond, Rotterdam, AJN

- Dr. L.C. (Leo) Smeets, arts-microbioloog, Reinier Haga MDC, Delft, NVMM, vanaf maart 2024

- Dr. J. (Jasmijn) Jagt, ANIOS kindergeneeskunde, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, Ede, persoonlijke titel

- E.C. (Esen) Doganer, junior projectmanager/ beleidsmedewerker, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis, tot maart 2023 en vanaf mei 2024

- M. (Marjolein) Jager, beleids-/projectmedewerker, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis, maart 2023 tot mei 2024

- Dr. W.A. (Wink) de Boer, MDL-arts, Bernhoven, Uden, NVMDL, tot maart 2024

- Dr. R.A.G. (Robert) Huis in ’t Veld, arts-microbioloog, UMCG, Groningen, tot maart 2024

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. J. (Janneke) Hoogervorst-Schilp, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. T. (Tim) Christen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- J. (Julia) Hofkes, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Mevr. dr. A. (Angelika) Kindermann (NVK, voorzitter) |

Kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Mevr. (Esen) Doganer MSc (Stichting Kind&Ziekenhuis) |

Projectmanager beleidsmedewerker, Stichting Kind&Ziekenhuis |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Mevr. M. (Marjolein) Jager (Stichting Kind&Ziekenhuis) |

Beleids-/projectmedewerker, Stichting Kind&Ziekenhuis |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Mevr. dr. R.W.B. (Renske) Bottema (NVK) |

Kinderarts-MDL, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, Ede |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Mevr. dr. P.E.C. (Nel) Mourad-Baars (NVK) |

Kinderarts-MDL n.p. |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Mevr. Dr. M. (Marianne) Almaç – Linthorst (AJN) |

Jeugdarts KNMG, CJG Rijnmond |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Dhr. Dr. L.C. (Leo) Smeets (NVMM) |

Arts-microbioloog, Reinier Haga MDC, Delft |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Mevr. Dr. J. (Jasmijn) Jagt (persoonlijke titel) |

ANIOS kindergeneeskunde, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, Ede |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Dhr. Dr. W.A. (Wink) de Boer (NVMDL, tot maart 2024) |

MDL-arts, Bernhoven, Uden |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Dhr. Dr. R.A.G. (Robert) Huis in ’t Veld (NVMM, tot maart 2024) |

Arts-microbioloog, UMCG, Groniningen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Klankbordgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis voor de schriftelijke invitational conference en een afgevaardigde van Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis in de werkgroep. Het verslag van de invitational conference is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de patiëntenvereniging en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Therapie bij Helicobacter pylori-infectie bij kinderen |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Module beschrijft zorg die voor het overgrote deel reeds aan deze aanbeveling voldoet. |

De kwalitatieve raming volgt na de commentaarfase.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 3.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor kinderen met H. pylori-infectie De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijnmodule (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde, 2012) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door medisch specialisten en verpleegkundigen door middel van een invitational conference.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werden de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |