Testen op feces

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de rol van testen op feces door middel van een feces antigeentest (stool antigen test (SAT)) en Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAAT) zoals polymerase chain reaction (PCR) voor de detectie van H. pylori en het vaststellen van resistentie bij kinderen van 0-18 jaar?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg een monoclonale feces antigeentest bij oudere kinderen met een eerstegraads familielid met maagcarcinoom.

Overweeg een monoclonale feces antigeentest als één van de mogelijke testen ter controle op succesvolle eradicatie (zie module Therapie bij Helicobacter pylori-infectie bij kinderen).

Wacht tot ten minste twee weken na stoppen van protonpompremmers (PPI’s) en vier weken na stoppen van antibiotica en bismut voor het inzetten van een feces antigeentest. Indien PPI’s niet gestaakt kunnen worden, overweeg dan om H2-antagonisten voor te schrijven (deze dienen dan twee dagen voor de test gestopt te worden).

Voer geen H. pylori PCR op feces uit.

Gebruik geen feces-antigeensneltests.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek gedaan naar de rol van PCR en antigeentest bij de detectie van resistentie in H. pylori op feces bij de diagnose van een H. pylori-infectie bij kinderen van 0-18 jaar. Drie studies werden geïncludeerd in de literatuuranalyse, waarbij één studie gaat over de feces-antigeentest, één studie gaat over het detecteren van antibiotica resistentie en de andere studie over eradicatie-effect. Er is geen literatuur gevonden over kosteneffectiviteit.

De Cochrane review van Best (2018) liet zien dat er grote onzekerheid is over de diagnostische accuratesse van de feces antigeentest. De bewijskracht was zeer laag vanwege brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen en een hoog risico op vertekening van de resultaten.

De studie van Scaletsky (2011), over het detecteren van antibiotica resistentie middels PCR testen op feces, vond ten opzichte van PCR op maagbiopten een sensitiviteit van 69% voor het detecteren van H. pylori in feces. Voor het juist detecteren van claritromycine resistentie was ten opzichte van maagbiopten de sensitiviteit 83.3%, de specificiteit 100% en de accuratesse van de test was 95.6%. De bewijskracht hiervoor was matig vanwege imprecisie.

PPI gebruik maakt de sensitiviteit van de feces-antigeentest lager (Parente, 2000), een negatieve uitslag is daarom minder betrouwbaar. Zoals ook in module 6 wordt besproken, wordt aanbevolen om zes tot acht weken na beëindigen van de therapie het succes van de behandeling te testen door middel van een non-invasieve test (feces-antigeentest of UBT, zie ook module Serologie volbloed/speeksel/urine en ureum-ademtest voor de non-invasieve testen). Test niet eerder dan zes weken in verband met het risico op een fout-negatieve uitslag en niet later dan acht weken vanwege het risico op re-infectie. Voor zowel bij de feces-antigeentest als de UBT bestaat er een kans op fout-negatieve uitslagen ten gevolge van de eradicatietherapie. Wacht daarom tot ten minste twee weken na stoppen van PPI’s en vier weken na stoppen van antibiotica en bismut voor het inzetten van de non-invasieve test. Wanneer PPI’s bij een patiënt niet gestaakt kunnen worden, overweeg dan om H2-antagonisten voor te schrijven alvorens het succes van de eradicatietherapie te evalueren. Deze dienen dan twee dagen voor de test gestopt te worden. (Homan, 2024)

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het verkrijgen van een ontlastingmonster is bij kinderen niet altijd eenvoudig: hulp van ouders daarbij is meestal nodig: jongere kinderen laten het vaak niet weten als ze naar de wc gaan en bij oudere kinderen speelt schaamte vaak een rol. Ook ouders hebben soms moeite met het verzamelen en inleveren van ontlasting van hun kinderen. Praktische instructie, hulpmiddelen en een goede uitleg kunnen hierbij helpen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

We hebben beperkt overzicht over de kosten van de verschillende diagnostische middelen, het lijkt wel dat PCR op dit moment duurder is dan een antigeentest.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

PCR voor H. pylori in feces is zowel voor detectie als voor resistentiebepaling in de praktijk vaak niet succesvol en (nog) niet algemeen beschikbaar in Nederland.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de diagnostische procedure

Non-invasief testen op aanwezigheid van H. pylori wordt in deze leeftijdscategorie in vrijwel geen enkele situatie in de primaire diagnostiek aanbevolen. Een positieve non-invasieve test is namelijk op zichzelf geen behandelindicatie (zie module Welke kinderen van 0-18 jaar moeten worden getest op H. pylori-infectie?). Vrijwel alle diagnoses die een indicatie vormen voor eradicatie van H. pylori worden gesteld op basis van een gastroscopie, en tijdens de gastroscopie kan dan direct een biopt met resistentiebepaling worden ingezet. Een uitzondering is een kind met een eerstegraads familielid met maagkanker. Dit is een indicatie voor een non-invasieve test. Het is daarbij te overwegen om te wachten tot late kinderleeftijd of volwassen leeftijd omdat de kans op herbesmetting het grootst is in de kindertijd.

Bij het stellen van indicaties voor moleculaire bepaling van resistentie tegen macroliden (waaronder Claritromycine) speelt dezelfde overweging. Bovendien is PCR voor H. pylori in feces zowel voor detectie als voor resistentiebepaling in de praktijk vaak niet succesvol en (nog) niet algemeen beschikbaar in Nederland. Specifiek voor detectie is nog relevant dat de PCR op dit moment duurder kan zijn dan een antigeentest, maar dit is afhankelijk van lokale afspraken.

De feces-antigeensneltests worden door de werkgroep op basis van oudere literatuur en de internationale richtlijn afgeraden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

This module will discuss non-invasive diagnostic options for H. pylori and their utility. Both, the stool antigen test (SAT) and the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test are non-invasive diagnostic tests performed on feces. The SAT is simple to perform and cheap compared to the urea breath test. PCR testing on feces could potentially be a non-invasive alternative to gastric biopsy for the detection of antimicrobial resistance to macrolides. However, the feces PCR test is not yet sufficiently reproducible and not widely available.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Very low GRADE |

It is very uncertain whether antigen testing on faeces increases diagnostic accuracy to detect a H. pylori infection in children suspected of a H. pylori-infection.

Source: Feng, 2022 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Using PCR likely increases antibiotic resistance detection when compared with culture in children with H. pylori-infection.

Source: Scaletsky, 2011 |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is very uncertain whether treatment strategies based on PCR increase eradication rate when compared with treatment strategies based on culture in children with H. pylori-infection.

Source: Feng, 2022 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect using PCR on cost-effectiveness when compared with culture in children with H. pylori-infection. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Best (2018) performed a systematic literature review to compare the diagnostic accuracy of urea breath test, serology, and stool antigen test, alone or in combination, for diagnosis of H. pylori infection in symptomatic and asymptomatic people. MEDLINE, Embase, the Science Citation Index and the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Database were searched until 4 March 2016. Diagnostic accuracy studies were included that evaluated at least one of the index tests (urea breath test using isotopes such as 13C or 14C, serology and stool antigen test) against the reference standard (endoscopic biopsy with Haemotoxylin & Eosin stain, special stains, or combination of Haemotoxylin & Eosin and special stains) in people suspected of having H. pylori-infection. Reports were excluded if they described how the diagnosis of H. pylori was made in an individual patient or group of patients, and if they did not provide sufficient diagnostic test accuracy data (i.e. the number of true positives, false positives, false negatives, and true negatives). Case-control studies were excluded, as well as studies that looked at repeat testing to monitor the success of treatment. The review included 101 studies with 11,003 participants, of which 5839 participants (53.1%) had H. pylori-infection. Twelve studies (N=1,097) included only children, those are the studies that we focus on for the purpose of this guideline. Main outcome measures of the study were sensitivity and specificity. Limitations of this study were that there was heterogeneity in the thresholds used for the index tests and studies did not often prespecify or clearly report thresholds used. Risk of bias was generally high or unclear with respect to the selection of participants, and the conduct and interpretation of the index tests and reference standard. Applicability concerns were also generally high or unclear with respect to selection of participants. Additionally, the interval between the index test and reference standard was unclear for 10/12 (83%) studies in children.

Feng (2022) performed a retrospective study of all patients between 6 and 18 years old with H. pylori-infection between September 2017 to October 2020 that were referred for endoscopy due to gastrointestinal symptoms. Patients underwent both culture and genetic testing for clarithromycin (CLA) resistance. A total of 71 patients with CLA-susceptible strains were allocated to the phenotype-guided therapy group and 87 patients without point mutations to the genotype-guided therapy group. Patients were offered either triple therapy (2 weeks, omeprazole, amoxicillin, and CLA) or sequential therapy (first week, omeprazole plus amoxicillin; second week, omeprazole plus CLA and metronidazole). Main outcome measures were eradication rate and antimicrobial resistance.

Scaletsky (2011) performed a retrospective study to validate a real-time assay in stool specimen. The study was conducted in Brazil and included 217 dyspeptic children between ages 1 to 18 years old. DNA from gastric biopsies and stool specimens were obtained and submitted to the real time assay for H. pylori detection and clarithromycin susceptibility testing. Main outcome measures were sensitivity, specificity, and test accuracy.

Results

Diagnostic accuracy to detect H. pylori-infection

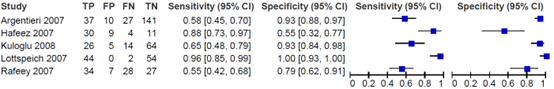

Best (2018) reported the diagnostic accuracy of the stool antigen test, compared to the reference standard (biopsy with haematoxylin and eosin stain, and Giemsa stain). The prevalence of H. pylori-infection varied from 29 to 65%. The sensitivity varied from 0.55 to 0.96, while the specificity of the stool antigen test varied from 0.55 to 1.00.

Diagnostic accuracy to detect antibiotic resistance

The study of Scaletsky (2011) reported the diagnostic accuracy of a faeces PCR test to detect clarithromycin resistance. The prevalence of H. pylori-infection was 20.7%. The sensitivity was reported to be 83.3%, the specificity to be 100% and the test’s accuracy was 95.6%. Confidence intervals were not reported.

Eradication rate

The study of Feng (2022) reported the eradication rate after treating patients according to either genotype-guided therapy or phenotype-guided therapy. Treatment success was achieved in 70.4% (95% CI: 58.4 to 80.7%) of patients under phenotype-guided therapy and in 92.0% (95% CI: 84.1 to 96.7%) of patients under genotype-guided therapy. We then calculated a relative risk ratio which resulted in 0.27 (95% CI: 0.12 to 0.60) for eradication.

Cost-effectiveness

No literature on cost-effectiveness was found.

Level of evidence of the literature

Diagnostic accuracy to detect H. pylori-infection

The level of evidence regarding the outcome diagnostic accuracy started as Low (observational studies), and was downgraded by two levels to Very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and low number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Diagnostic accuracy to detect antibiotic resistance

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure diagnostic accuracy to detect antibiotic resistance started as High (diagnostic studies) and was downgraded by one level to Moderate because of low number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Eradication rate

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure eradication rate started as Low (observational studies) and was downgraded by two levels to Very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and low number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Cost-effectiveness

No level of evidence was determined due to no literature being found.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the diagnostic accuracy of PCR to determine antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori in feces in children diagnosed with a Helicobacter pylori-infection?

| P: |

Children (0-18 years old) with diagnosed H. pylori-infection |

| I: |

Fecal/stool sample or gastric biopsy PCR antibiotic resistance determination |

| C: |

Other diagnostic methods |

| R: |

Gold standard endoscopy with culture |

| O: |

Diagnostic accuracy to detect antibiotic resistance, treatment success/failure, cost effectiveness |

| T/S: | After diagnosis with H. pylori |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered diagnostic accuracy to detect antibiotic resistance as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and treatment success/failure and cost effectiveness as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases [Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com)] were searched with relevant search terms until July 11th, 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 114 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: applicable to the research question, and published after 2011. Twelve studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, ten studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included. One study was added to the analysis, while it was selected for a different PICO (Best, 2018)

Results

Three studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Best LM, Takwoingi Y, Siddique S, Selladurai A, Gandhi A, Low B, Yaghoobi M, Gurusamy KS. Non-invasive diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Mar 15;3(3):CD012080. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012080.pub2. PMID: 29543326; PMCID: PMC6513531.

- Feng Y, Hu W, Wang Y, Lu J, Zhang Y, Tang Z, Miao S, Zhou Y, Huang Y. Efficacy of Phenotype-vs. Genotype-Guided Therapy Based on Clarithromycin Resistance for Helicobacter pylori Infec-tion in Children. Front Pediatr. 2022 Mar 29;10:854519. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.854519. PMID: 35425727; PMCID: PMC9002118.

- Parente F, Sainaghi_M, Maconi_G, Imbesi_V, Cucino_C, Porro_GB. Not all short-term proton pump inhibitors (ppi) impair the accuracy of c-13-urea breath test and h.Pylori stool antigen assay. Gut 2000;46(Suppl 2):A86.

- Scaletsky IC, Aranda KR, Garcia GT, Gonçalves ME, Cardoso SR, Iriya K, Silva NP. Application of real-time PCR stool assay for Helicobacter pylori detection and clarithromycin susceptibility testing in Brazilian children. Helicobacter. 2011 Aug;16(4):311-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00845.x. PMID: 21762271.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for diagnostic test accuracy studies

Research question: What is the diagnostic accuracy of PCR to determine antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori in feces in children diagnosed with a Helicobacter pylori infection?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics

|

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Best, 2018

|

SR and meta-analysis

Literature search up to 4 March 2016.

A: Behrens, 1999 B: Czerwionka-Szaflarska, 2007 C: Delvin, 1999 D: Dinler, 1999 E: Eltumi, 1999 F: Hafeez, 2007 G: Kalach, 1998 H: Kuloglu, 2008 I: Lottspeich, 2007 J: Ogata, 2001 K: Vandenplas, 1992 L: Yoshimura, 2001

Study design: A: unclear B: retrospective study C: prospective study D: unclear E: prospective study F: unclear G: prospective study H: prospective study I: unclear J: prospective study K: unclear L: unclear

Setting and Country: A: secondary care, Germany B: secondary care, Poland C: secondary care, Canada D: secondary care, Turkey E: tertiary care, UK F: secondary care, Pakistan G: secondary care, France H: secondary care, Turkey I: secondary care, Germany J: secondary care, Brazil K: secondary care, Belgium L: secondary care, Japan

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: This report is independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR Cochrane Programme Grants, 13/89/03 - Evidence-based diagnosis and management of upper digestive, hepato-biliary, and pancreatic disorders). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

|

Inclusion criteria SR: Diagnostic accuracy studies that evaluated at least one of the index tests (urea breath test using isotopes such as 13C or 14C, serology and stool antigen test) against the reference standard (endoscopic biopsy with Haemotoxylin & Eosin stain, special stains, or combination of Haemotoxylin & Eosin and special stains) in people suspected of having H pylori infection. Regardless of language or publication status, or whether data were collected prospectively or retrospectively.

Exclusion criteria SR: Reports that describe how the diagnosis of H pylori was made in an individual patient or group of patients, and which do not provide sufficient diagnostic test accuracy data (i.e. the number of true positives, false positives, false negatives, and true negatives. They also exclude case-control studies.

101 studies included (N=11,003), of which 12 studies (N=1,097) included only children.

N, mean age A: 252; 3-18 years B: 100; 13 years C: 79; age not stated D: 77; 13 years E: 50; 11 years F: 60; age not stated G: 100; 11 years H: 109; 12 years I: 56; 10 years J: 47; 12 years K: 95; 9 years L: 72; 13 years

Sex (% M): A: - B: 34% in total group C: - D: 37.7% in total group E: 66% in total group F: - G: 65% in total group H: 66.8% in total group I: - J: 42.6% in total group K: 67.4% in total group L: 52.8% in total group |

Describe index and comparator tests* and cut-off point(s):

A: urea breath test -13C (criteria for positive diagnosis: delta over baseline > 5.0% (30 minutes and 60 minutes)) B: urea breath test -13C (criteria for positive diagnosis: delta over baseline > 4.0 % (time not stated)) C: urea breath test -13C (Different criteria for positive diagnosis:

D: serology (Criteria for positive diagnosis: not stated) E-1: urea breath test -13C (criteria for positive diagnosis: delta over baseline > 5 units/ml (40 minutes)) E-2: serology (criteria for positive diagnosis: not stated) F-1: urea breath test -13C (criteria for positive diagnosis: delta over baseline > 4.0% (10 minutes, 20 minutes, and 30 minutes)) G: serology (Criteria for positive diagnosis: > 6 IU /ml) H: urea breath test-14C (Criteria for positive diagnosis: Counts per minute > 50 (10 minutes)) I: urea breath test -13C (criteria for positive diagnosis: delta over baseline > 5.0% (30 minutes)) J-1: urea breath test -13C (criteria for positive diagnosis: 3% excretion (time not stated)) J-2: serology (criteria for positive diagnosis: 7 U/ml) K-1: urea breath test -13C (criteria for positive diagnosis: not clearly stated) K-2: serology (criteria for positive diagnosis:> Mean + 3 standard deviations above normal level) L-1: urea breath test -13C (criteria for positive diagnosis: delta over baseline > 3.0% (20 minutes and 30 minutes)) L-2: serology (criteria for positive diagnosis: ≥ 1.8)

|

Describe reference test and cut-off point(s):

A: endoscopic biopsy with H & E stain B: endoscopic biopsy with H & E stain C: endoscopic biopsy with H & E stain and Warthin-Starry stain D: endoscopic biopsy (staining not reported, probably H & E) E: endoscopic biopsy with H & E stain and Warthin-Starry stain F: endoscopic biopsy with Giemsa stain G: endoscopic biopsy with H & E stain H: endoscopic biopsy with H & E stain and Giemsa stain I: endoscopic biopsy with H & E stain or Giemsa stain J: endoscopic biopsy with H & E stain and Giemsa stain K: endoscopic biopsy with H & E stain and Giemsa stain L: endoscopic biopsy with H & E stain and Giemsa stain

Prevalence (%) Not clearly described per study

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not clearly specified

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Not clearly specified

|

Endpoint of follow-up: Not clearly described per study |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Outcome measure-1/2 Sensitivity: A: 0.95 (95% CI: 0.90, 0.98) B: 0.68 (95% CI: 0.49, 0.83) C: 1.00 (95% CI: 0.74, 1.00) D: 0.83 (95% CI: 0.71, 0.91) E-1: 0.89 (95% CI: 0.67, 0.99) E-2: 0.95 (95% CI: 0.74, 1.00) F: 0.91 (95% CI: 0.76, 0.98) G: 0.84 (95% CI: 0.70, 0.93) H: 0.93 (95% CI: 0.80, 0.98) I: 1.00 (95% CI: 0.91, 1.00) J-1: 0.96 (95% CI: 0.78, 1.00) J-2: 1.00 (95% CI: 0.85, 1.00) K-1: 0.89 (95% CI: 0.71, 0.98) K-2: 0.89 (95% CI: 0.71, 0.98) L-1: 0.95 (95% CI: 0.85, 0.99) L-2: 0.93 (95% CI: 0.81, 0.99)

Specificity: A: 0.93 (95% CI: 0.87, 0.97) B: 0.93 (95% CI: 0.84, 0.98) C: 1.00 (95% CI: 0.95, 1.00) D: 0.42 (95% CI: 0.20, 0.67) E-1: 0.90 (95% CI: 0.74, 0.98) E-2: 0.81 (95% CI: 0.63, 0.93) F: 0.60 (95% CI: 0.36, 0.81) G: 0.88 (95% CI: 0.76, 0.95) H: 0.86 (95% CI: 0.75, 0.93) I: 1.00 (95% CI: 0.78, 1.00) J-1: 0.67 (95% CI: 0.45, 0.84) J-2: 0.67 (95% CI: 0.45, 0.84) K-1: 0.93 (95% CI: 0.84, 0.98) K-2: 0.96 (95% CI: 0.88, 0.99) L-1: 0.89 (95% CI: 0.72, 0.98) L-2: 0.89 (95% CI: 0.72, 0.98)

Pooled characteristic per index test and cut-off point: Cannot be used for our review, because we are only interested in children and Best (2018) presents results for children and adults combined

Outcome measure-3 TP, FP, FN, TN: A: 129, 7, 7, 98 B: ?, 5, 10, 64 C: 12, 0, 0, 67 D: 48, 11, 10, 8 E-1: 17, 3, 2, 28 E-2: 18, 6, 1, 25 F: 31, 8, 3, 12 G: 37, 7, 7, 49 H: 37, 10, 3, 59 I: 41, 0, 0, 15 J-1: 22, 8, 1, 16 J-2: 23, 8, 0, 16 K-1: 24, 5, 3, 63 K-2: 24, 3, 3, 65 L-1: 42, 3, 2, 25 L-2: 41, 3, 3, 25

|

Study quality (ROB): Tool used by authors: QUADAS-2, see table “Risk of bias assessment diagnostic accuracy studies” for individual study qualifications

Place of the index test in the clinical pathway: Not clearly described

Choice of cut-off point: Not clearly described per study

Author’s conclusion (for their whole study population, so not only in children) In people with no history of gastrectomy and those who have not recently had antibiotics or proton pump inhibitors, urea breath tests had high diagnostic accuracy while serology and stool antigen tests had lower accuracy to detect H pylori infection. Although susceptible to bias due to confounding, this conclusion is based on evidence from indirect test comparisons, as evidence from direct comparisons was based on few studies or was unavailable. There was high or unclear risk of bias for many studies with respect to the selection of participants, and the conduct and interpretation of the index tests and reference standard. The thresholds used for these tests were highly variable, thus there is insufficient evidence to identify specific thresholds that might be useful in clinical practice.

Personal remarks on study quality, conclusions, and other issues (potentially) relevant to the research question Limitations:

|

|

Feng, 2022 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort

Setting and country: Children hospital’s outpatient department, China

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients aged between 6 and 18 years with H. pylori infection were referred for endoscopy due to gastrointestinal symptoms, and who agreed to undergo both culture and genetic testing for CLA resistance were eligible for enrolment. Patients receiving tailored therapy based on traditional culture (phenotype-guided therapy) or genetic testing (genotype-guided therapy) results were ultimately included.

Exclusion criteria: use of antibiotics or bismuth agents within 4 weeks or proton pump inhibitors within 2 weeks before the examination; previous eradication therapy; allergies or contraindications to the therapeutic drugs in this study; or complications with other chronic or serious diseases.

Number of patients I: N=87 R: N=71

Prevalence: 100%

Mean age (SD): I: 9.7 (2.6) R: 10.2 (2.5)

Sex: I: 66.7% M/ 33.3% F |

Deoxyribonucleic acid from gastric biopsies was extracted with the TIANamp Micro DNA Kit (DP316, Beijing, China). PCR-based amplification of the 23S rRNA was performed to detect CLA-resistant mutations (A2142G, A2142C, and A2143G). Primers as followed (Jieli Bio): forward, 1,820–1,839 (5’-CCCAGCGATGTGGTCCAG-3’) and reverse, 2,244–2,225 (5’-CTCCATAAGAGCCAAAGCCC-3’). Reaction in 25μl mixture contained 1 μl of template DNA (<1 ug), 1 μl of each primer (10μM), 22 μl of 1.1×T3 super PCR mix (Tsingke, TSE030) and conducted using the following program: 1 cycle at 98◦C for 3min, 35 cycles at 98◦C for 15 s, 65◦C for 15 s, and 72◦C for 30 s and final 1 cycle at 72◦C for 7min. The 425-bp PCR products were sent to a biotechnology company for sequencing (ABI 3730XL, Jieli Bio). Finally, Chromas 2 software was used to analyze mutations at positions 2,142 and 2,143.

Cut-off point(s): minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) > 0.5 mg/l

|

Culture

Cut-off point(s): NA

|

Time between the index test and reference test: NA

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? 0

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

Eradication rate: I: 92.0% (95% CI; 84.1% to 96.7%) R: 70.4% (95% CI; 58.4% to 80.7%) |

|

|

Scaletsky, 2011 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort

Setting and country: University hospital, Brazil

Funding and conflicts of interest: This work was supported by Fundacão de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo. |

Inclusion criteria: Children between 1-18 with dyspeptic symptoms

Exclusion criteria: Patients previously treated for H. pylori infections were not included

N=217 children

Prevalence: 20.7%

Mean age: 10 yrs; no SD reported

Sex: 51.6% M / 48.4% F |

Helicobacter pylori ClariRes assay (Ingenetix, Vienna, Austria) is a novel commercially available real-time PCR assay allowing H. pylori detection and clarithromycin susceptibility testing in either gastric biopsy or stool specimens. ClariRes assay is a modified version of the biprobe 23S rRNA gene real-time PCR assay published by Schabereiter-Gurtner et al.

Cut-off point(s): NA

|

Culture

Cut-off point(s): NA

|

Time between the index test and reference test: NA

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? 0

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

Antibiotic resistance detection Sensitivity: 83.3%

Specificity: 100%

Accuracy: 95.6%

|

|

|

Vecsei, 2011 |

Type of study: retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: pediatric hospital, Austria

Funding and conflicts of interest: Drs Hirschl and Makristathis have received consultancy fees from Ingenetics. |

Inclusion criteria: children after an initial course of tailored triple eradication therapy.

Exclusion criteria: Previously treated children having failed 1 or more courses of therapy

N= 96

Prevalence of resistance: 16.7%

Mean age ± SD: 10.8 y (3.8)

Sex: 48% M / 52% F

Other important characteristics:

|

Describe index test: biopsy samples were homogenized and cultured followed by antibiogram

Cut-off point(s): Breakpoints of resistance to clarithromycin, metronidazole, amoxicillin, levofloxacin, tetracycline, and rifampin were minimal inhibitory concentration values of ≥1, 16, 4, 2, 2, and 4mg/mL, respectively.

|

Describe reference test: Using 200 mg stool, DNA was extracted with a QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Stool DNA extracts were analyzed by fluorescence resonance energy transfer real-time PCR and melting curve analysis (H pylori ClariRes assay, Ingenetix, Vienna, Austria) in combination with LightCycler-FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany). A DNA probe labeled with the fluorophore Cy5 includes the sites of the mutations on the H pylori 23S rRNA gene responsible for resistance to clarithromycin and has 100% homology to the sensitive wild-type genotype.

Cut-off point(s): A melting temperature of 638C corresponds to the clarithromycin-sensitive wild-type genotype; in resistant genotypes the melting temperature is 548C for mutationsA2142GandA2143Gand 588Cfor mutationA2142C. |

Time between the index test and reference test: Not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

Eradication rate ratio: 0.94 (0.57 to 1.53) |

|

* Due to incomplete reporting, this systematic review was described as a singular study

Risk of bias assessment

Research question: What is the diagnostic accuracy of PCR to determine antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori in feces in children diagnosed with a Helicobacter pylori infection?

|

Study reference |

Patient selection

|

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Feng, 2022 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? NA

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

|

|

Scaletsky, 2011 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? NA

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

|

Study reference |

Patient selection

|

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Best, 2018

A: Hafeez, 2007 (antigen test faeces) B: Kuloglu, 2008 (antigen test faeces) C: Lottspeich, 2007 (antigen test faeces) D: Rafeey, 2007 (antigen test faeces) E: Argentieri, 2007 (antigen test faeces) |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? A: no B: no C: no D: no E: no

Was a case-control design avoided? A: yes B: yes C: yes D: yes E: yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? A: unclear B: unclear C: unclear D: unclear E: unclear

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? A: unclear B: unclear C: unclear D: unclear E: unclear

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? A: unclear B: unclear C: unclear D: unclear E: unclear

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? A: yes B: no C: no D: yes E: yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? A: unclear B: yes C: unclear D: unclear E: unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? A: yes B: unclear C: yes D: unclear E: unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Unclear

Did patients receive the same reference standard? A: yes B: yes C: yes D: yes E: yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? A: no B: no C: unclear D: unclear E: unclear |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? Yes Best (2018) includes all ages, while our guideline focuses on children

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

Author, year |

Selection of participants

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population?

|

Exposure

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?

|

Outcome of interest

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study?

|

Confounding-assessment

Can we be confident in the assessment of confounding factors?

|

Confounding-analysis

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these confounding variables?

|

Assessment of outcome

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome?

|

Follow up

Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? In particular, was outcome data complete or imputed?

|

Co-interventions

Were co-interventions similar between groups?

|

Overall Risk of bias

|

|

Vescei, 2011 |

Probably no

Reason: Inclusion and exclusion criteria may be related to outcome

|

Probably yes

Reason: Exposure was provided by pharmacy

|

Probably yes

Reason: Relevant methods were used to evaluate status of resistance

|

Probably no

Reason: only some confounders were measured

|

Definitely no

Reason: No adjustment was performed

|

Definitely yes

Reason: sensitive measurement was used

|

Probably yes

Reason: not reported

|

Probably yes

Reason: Not reported

|

Some concerns

|

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Angol DC, Ocama P, Ayazika Kirabo T, Okeng A, Najjingo I, Bwanga F. Helicobacter pylori from Peptic Ulcer Patients in Uganda Is Highly Resistant to Clarithromycin and Fluoroquinolones: Results of the GenoType HelicoDR Test Directly Applied on Stool. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:5430723. doi: 10.1155/2017/5430723. Epub 2017 May 7. PMID: 28555193; PMCID: PMC5438841. |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

Güven B, Gülerman F, Kaçmaz B. Helicobacter pylori resistance to clarithromycin and fluoroquinolones in a pediatric population in Turkey: A cross-sectional study. Helicobacter. 2019 Jun;24(3):e12581. doi: 10.1111/hel.12581. Epub 2019 Apr 4. PMID: 30950125. |

Wrong intervention: no faeces sample |

|

Hansomburana P, Anantapanpong S, Sirinthornpunya S, Chuengyong K, Rojborwonwittaya J. Prevalence of single nucleotide mutation in clarithromycin resistant gene of Helicobacter pylori: a 32-months prospective study by using hybridization real time polymerase chain reaction. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012 Mar;95 Suppl 3:S28-35. PMID: 22619884. |

Wrong population: adults |

|

Kargar, Mohammad & Ghorbani-Dalini, Sadegh & Doosti, Abbas & Baghernejad, Maryam. (2011). Molecular assessment of clarithromycin resistant Helicobacter pylori strains using rapid and accurate PCR-RFLP method in gastric specimens in Iran. African Journal of Biotechnology. 10. 7675-7678. |

Wrong population: adults |

|

Khalifehgholi M, Shamsipour F, Ajhdarkosh H, Ebrahimi Daryani N, Pourmand MR, Hosseini M, Ghasemi A, Shirazi MH. Comparison of five diagnostic methods for Helicobacter pylori. Iran J Microbiol. 2013 Dec;5(4):396-401. PMID: 25848511; PMCID: PMC4385167. |

Wrong population: adults |

|

Leal YA, Cedillo-Rivera R, Simón JA, Velázquez JR, Flores LL, Torres J. Utility of stool sample-based tests for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011 Jun;52(6):718-28. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182077d33. PMID: 21478757. |

Wrong design: no comparison |

|

Miendje Deyi VY, Burette A, Bentatou Z, Maaroufi Y, Bontems P, Lepage P, Reynders M. Practical use of GenoType® HelicoDR, a molecular test for Helicobacter pylori detection and susceptibility testing. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011 Aug;70(4):557-60. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.05.002. Epub 2011 Jun 22. PMID: 21696906. |

Wrong population: adults |

|

Osaki T, Mabe K, Zaman C, Yonezawa H, Okuda M, Amagai K, Fujieda S, Goto M, Shibata W, Kato M, Kamiya S. Usefulness of detection of clarithromycin-resistant Helicobacter pylori from fecal specimens for young adults treated with eradication therapy. Helicobacter. 2017 Oct;22(5). doi: 10.1111/hel.12396. Epub 2017 May 22. PMID: 28544222. |

Wrong population: adults |

|

Vécsei A, Innerhofer A, Graf U, Binder C, Giczi H, Hammer K, Bruckdorfer A, Hirschl AM, Makristathis A. Helicobacter pylori eradication rates in children upon susceptibility testing based on noninvasive stool polymerase chain reaction versus gastric tissue culture. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011 Jul;53(1):65-70. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318210586d. PMID: 21694538. |

Wrong population: children already received treatment |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 25-06-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 24-04-2025

Algemene gegevens

Belangrijkste wijzigingen t.o.v. vorige versie: De vorige richtlijn stamde uit 2012, sindsdien zijn de inzichten in knelpunten veranderd, alsmede de stand van wetenschap en het antibioticaresistentiepatroon van infecties met H. pylori. Tevens is er in 2024 een nieuwe internationale richtlijn over H. pylori gepubliceerd door de ESPHGAN/NASPGHAN. Deze richtlijn tracht hier zoveel als mogelijk bij aan te sluiten met inachtneming van de situatie in Nederland.

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kinderen met een verdachte of bevestigde H. pylori-infectie of klachten die hierbij passen.

Werkgroep

- Dr. A. (Angelika) Kindermann, kinderarts MDL, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVK, voorzitter

- Dr. R.W.B. (Renske) Bottema, kinderarts MDL, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, Ede, NVK

- Dr. P.E.C. (Nel) Mourad-Baars, kinderarts MDL n.p., NVK

- Dr. M. (Marianne) Almaç – Linthorst, jeugdarts, CJG Rijnmond, Rotterdam, AJN

- Dr. L.C. (Leo) Smeets, arts-microbioloog, Reinier Haga MDC, Delft, NVMM, vanaf maart 2024

- Dr. J. (Jasmijn) Jagt, ANIOS kindergeneeskunde, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, Ede, persoonlijke titel

- E.C. (Esen) Doganer, junior projectmanager/ beleidsmedewerker, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis, tot maart 2023 en vanaf mei 2024

- M. (Marjolein) Jager, beleids-/projectmedewerker, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis, maart 2023 tot mei 2024

- Dr. W.A. (Wink) de Boer, MDL-arts, Bernhoven, Uden, NVMDL, tot maart 2024

- Dr. R.A.G. (Robert) Huis in ’t Veld, arts-microbioloog, UMCG, Groningen, tot maart 2024

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. J. (Janneke) Hoogervorst-Schilp, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. T. (Tim) Christen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- J. (Julia) Hofkes, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Mevr. dr. A. (Angelika) Kindermann (NVK, voorzitter) |

Kinderarts-MDL, Amsterdam UMC |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Mevr. (Esen) Doganer MSc (Stichting Kind&Ziekenhuis) |

Projectmanager beleidsmedewerker, Stichting Kind&Ziekenhuis |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Mevr. M. (Marjolein) Jager (Stichting Kind&Ziekenhuis) |

Beleids-/projectmedewerker, Stichting Kind&Ziekenhuis |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Mevr. dr. R.W.B. (Renske) Bottema (NVK) |

Kinderarts-MDL, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, Ede |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Mevr. dr. P.E.C. (Nel) Mourad-Baars (NVK) |

Kinderarts-MDL n.p. |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Mevr. Dr. M. (Marianne) Almaç – Linthorst (AJN) |

Jeugdarts KNMG, CJG Rijnmond |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Dhr. Dr. L.C. (Leo) Smeets (NVMM) |

Arts-microbioloog, Reinier Haga MDC, Delft |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Mevr. Dr. J. (Jasmijn) Jagt (persoonlijke titel) |

ANIOS kindergeneeskunde, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, Ede |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Dhr. Dr. W.A. (Wink) de Boer (NVMDL, tot maart 2024) |

MDL-arts, Bernhoven, Uden |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Dhr. Dr. R.A.G. (Robert) Huis in ’t Veld (NVMM, tot maart 2024) |

Arts-microbioloog, UMCG, Groniningen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

|

Klankbordgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis voor de schriftelijke invitational conference en een afgevaardigde van Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis in de werkgroep. Het verslag van de invitational conference is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de patiëntenvereniging en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Testen op feces |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Module beschrijft zorg die voor het overgrote deel reeds aan deze aanbeveling voldoet. |

De kwalitatieve raming volgt na de commentaarfase.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 3.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor kinderen met H. pylori-infectie De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijnmodule (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde, 2012) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door medisch specialisten en verpleegkundigen door middel van een invitational conference.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werden de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Algemene informatie

|

Cluster/richtlijn: NVK Helicobacter pylori-infectie bij kinderen |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag/modules: Wat is de rol van PCR op faeces of maagbiopten bij de detectie van resistentie in Helicobacter pylori op faeces of maagbiopten bij de diagnose van een H. pylori-infectie bij kinderen van 0-18 jaar? |

|

|

Database(s): Embase.com, Ovid/Medline |

Datum: 11 juli 2023 |

|

Periode: vanaf maart 2011 |

Talen: geen restrictie |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Alies van der Wal |

Rayyan review: https://rayyan.ai/reviews/720999 |

|

BMI-zoekblokken: voor verschillende opdrachten wordt (deels) gebruik gemaakt van de zoekblokken van BMI-Online https://blocks.bmi-online.nl/ Bij gebruikmaking van een volledig zoekblok zal naar de betreffende link op de website worden verwezen. |

|

|

Toelichting: Voor deze vraag is gezocht op de elementen:

àVier van de sleutelartikelen gaan niet over kinderen en worden daarom niet gevonden met deze search. Na overleg is besloten om de search toch op kinderen te richten en eventueel in de overwegingen te refereren naar de sleutelartikelen over volwassenen. |

|

|

Te gebruiken voor richtlijnen tekst: Nederlands In de databases Embase.com en Ovid/Medline is op 11 juli 2023 systematisch gezocht naar systematische reviews, RCTs en observationele studies over de waarde van PCR test bij kinderen met helicobacter pylori. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 114 unieke treffers op.

Engels On the 11th of July 2023, a systematic search was performed in the databases Embase.com and Ovid/Medline for systematic reviews, RCTs and observational studies on the value of PCR test in children with helicobacter pylori. The search resulted in 114 unique hits. |

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

EMBASE |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SR |

9 |

3 |

8 |

|

RCT |

9 |

4 |

11 |

|

Observationele studies |

92 |

14 |

95 |

|

Totaal |

110 |

21 |

114* |

*in Rayyan

Zoekstrategie

Embase.com

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#15 |

#12 OR #13 OR #14 |

110 |

|

#14 |

#7 AND (#10 OR #11) NOT (#12 OR #13) = observationeel |

92 |

|

#13 |

#7 AND #9 NOT #12 = RCT |

9 |

|

#12 |

#7 AND #8 = SR |

9 |

|

#11 |

'case control study'/de OR 'comparative study'/exp OR 'control group'/de OR 'controlled study'/de OR 'controlled clinical trial'/de OR 'crossover procedure'/de OR 'double blind procedure'/de OR 'phase 2 clinical trial'/de OR 'phase 3 clinical trial'/de OR 'phase 4 clinical trial'/de OR 'pretest posttest design'/de OR 'pretest posttest control group design'/de OR 'quasi experimental study'/de OR 'single blind procedure'/de OR 'triple blind procedure'/de OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/6 trial):ti,ab,kw) OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/6 (study OR studies)):ti,ab,kw) OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/1 active):ti,ab,kw) OR 'open label*':ti,ab,kw OR (((double OR two OR three OR multi OR trial) NEAR/1 (arm OR arms)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((allocat* NEAR/10 (arm OR arms)):ti,ab,kw) OR placebo*:ti,ab,kw OR 'sham-control*':ti,ab,kw OR (((single OR double OR triple OR assessor) NEAR/1 (blind* OR masked)):ti,ab,kw) OR nonrandom*:ti,ab,kw OR 'non-random*':ti,ab,kw OR 'quasi-experiment*':ti,ab,kw OR crossover:ti,ab,kw OR 'cross over':ti,ab,kw OR 'parallel group*':ti,ab,kw OR 'factorial trial':ti,ab,kw OR ((phase NEAR/5 (study OR trial)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((case* NEAR/6 (matched OR control*)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((match* NEAR/6 (pair OR pairs OR cohort* OR control* OR group* OR healthy OR age OR sex OR gender OR patient* OR subject* OR participant*)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((propensity NEAR/6 (scor* OR match*)):ti,ab,kw) OR versus:ti OR vs:ti OR compar*:ti OR ((compar* NEAR/1 study):ti,ab,kw) OR (('major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR 'observational study'/de OR 'cross-sectional study'/de OR 'multicenter study'/de OR 'correlational study'/de OR 'follow up'/de OR cohort*:ti,ab,kw OR 'follow up':ti,ab,kw OR followup:ti,ab,kw OR longitudinal*:ti,ab,kw OR prospective*:ti,ab,kw OR retrospective*:ti,ab,kw OR observational*:ti,ab,kw OR 'cross sectional*':ti,ab,kw OR cross?ectional*:ti,ab,kw OR multicent*:ti,ab,kw OR 'multi-cent*':ti,ab,kw OR consecutive*:ti,ab,kw) AND (group:ti,ab,kw OR groups:ti,ab,kw OR subgroup*:ti,ab,kw OR versus:ti,ab,kw OR vs:ti,ab,kw OR compar*:ti,ab,kw OR 'odds ratio*':ab OR 'relative odds':ab OR 'risk ratio*':ab OR 'relative risk*':ab OR 'rate ratio':ab OR aor:ab OR arr:ab OR rrr:ab OR ((('or' OR 'rr') NEAR/6 ci):ab))) |

14236747 |

|

#10 |

'major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'case control study'/de OR 'family study'/de OR 'longitudinal study'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR 'prospective study'/de OR 'comparative study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR ((cohort NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('case control' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('follow up' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (observational NEAR/1 (study OR studies)) OR ((epidemiologic NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('cross sectional' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) |

7728902 |

|

#9 |

'clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR 'prospective study'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti |

3827532 |

|

#8 |

'meta analysis'/exp OR 'meta analysis (topic)'/exp OR metaanaly*:ti,ab OR 'meta analy*':ti,ab OR metanaly*:ti,ab OR 'systematic review'/de OR 'cochrane database of systematic reviews'/jt OR prisma:ti,ab OR prospero:ti,ab OR (((systemati* OR scoping OR umbrella OR 'structured literature') NEAR/3 (review* OR overview*)):ti,ab) OR ((systemic* NEAR/1 review*):ti,ab) OR (((systemati* OR literature OR database* OR 'data base*') NEAR/10 search*):ti,ab) OR (((structured OR comprehensive* OR systemic*) NEAR/3 search*):ti,ab) OR (((literature NEAR/3 review*):ti,ab) AND (search*:ti,ab OR database*:ti,ab OR 'data base*':ti,ab)) OR (('data extraction':ti,ab OR 'data source*':ti,ab) AND 'study selection':ti,ab) OR ('search strategy':ti,ab AND 'selection criteria':ti,ab) OR ('data source*':ti,ab AND 'data synthesis':ti,ab) OR medline:ab OR pubmed:ab OR embase:ab OR cochrane:ab OR (((critical OR rapid) NEAR/2 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ti) OR ((((critical* OR rapid*) NEAR/3 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ab) AND (search*:ab OR database*:ab OR 'data base*':ab)) OR metasynthes*:ti,ab OR 'meta synthes*':ti,ab |

942968 |

|

#7 |

#6 AND [01-03-2011]/sd |

124 |

|

#6 |

#5 NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal'/exp OR 'animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

226 |

|

#5 |

#1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 |

288 |

|

#4 |

'sensitivity and specificity'/de OR sensitivity:ab,ti OR sensitive:ab,ti OR specificity:ab,ti OR predict*:ab,ti OR 'roc curve':ab,ti OR 'receiver operator':ab,ti OR 'receiver operators':ab,ti OR likelihood:ab,ti OR 'diagnostic error'/exp OR 'diagnostic accuracy'/exp OR 'diagnostic test accuracy study'/exp OR 'inter observer':ab,ti OR 'intra observer':ab,ti OR interobserver:ab,ti OR intraobserver:ab,ti OR validity:ab,ti OR kappa:ab,ti OR reliability:ab,ti OR reproducibility:ab,ti OR ((test NEAR/2 're-test'):ab,ti) OR ((test NEAR/2 'retest'):ab,ti) OR 'reproducibility'/exp OR accuracy:ab,ti OR 'differential diagnosis'/exp OR 'validation study'/de OR 'measurement precision'/exp OR 'diagnostic value'/exp OR 'reliability'/exp OR ppv:ti,ab,kw OR npv:ti,ab,kw OR (((false OR true) NEAR/3 (negative OR positive)):ti,ab) |

6697243 |

|

#3 |

'nucleic acid amplification techniques'/exp OR 'nucleic acid amplification test'/exp OR 'qpcr'/exp OR 'sanger sequencing'/exp OR 'lamp system'/exp OR 'pcr':ti,ab,kw OR 'pcrs':ti,ab,kw OR 'qpcr':ti,ab,kw OR 'rtpcr':ti,ab,kw OR 'polymerase chain reaction*':ti,ab,kw OR 'poly merase chain reaction*':ti,ab,kw OR 'polymer ase chain reaction*':ti,ab,kw OR ((('nucleic acid' OR dna OR rna) NEAR/3 (amplification OR test*)):ti,ab,kw) OR nat:ti,ab,kw OR naat:ti,ab,kw OR lamp:ti,ab,kw OR (('loop mediated' NEAR/3 amplification):ti,ab,kw) OR (((sanger* OR 'chain termination') NEAR/3 (sequenc* OR method*)):ti,ab,kw) |

1650364 |

|

#2 |

'adolescent'/exp OR 'baby'/exp OR 'boy'/exp OR 'child'/exp OR 'minors'/exp/mj OR 'pediatric patient'/exp OR 'pediatrics'/exp OR 'schoolchild'/exp OR infan*:ti,ab,kw OR newborn*:ti,ab,kw OR 'new born*':ti,ab,kw OR perinat*:ti,ab,kw OR neonat*:ti,ab,kw OR baby*:ti,ab,kw OR babies:ti,ab,kw OR toddler*:ti,ab,kw OR minors*:ti,ab,kw OR boy:ti,ab,kw OR boys:ti,ab,kw OR boyfriend:ti,ab,kw OR boyhood:ti,ab,kw OR girl*:ti,ab,kw OR kid:ti,ab,kw OR kids:ti,ab,kw OR child*:ti,ab,kw OR children*:ti,ab,kw OR schoolchild*:ti,ab,kw OR adolescen*:ti,ab,kw OR juvenil*:ti,ab,kw OR youth*:ti,ab,kw OR teen*:ti,ab,kw OR pubescen*:ti,ab,kw OR pediatric*:ti,ab,kw OR paediatric*:ti,ab,kw OR peadiatric*:ti,ab,kw OR school:ti,ab,kw OR school*:ti,ab,kw OR prematur*:ti,ab,kw OR preterm*:ti,ab,kw |

5745259 |

|

#1 |

'helicobacter pylori'/exp/mj OR 'helicobacter infection'/exp/mj OR 'helicobacter'/mj OR (((helicobacter OR 'h') NEAR/3 pylori):ti,ab,kw) OR 'helicobacter':ti,ab,kw |

73998 |

Ovid/Medline

|

# |

Searches |

Results |

|

15 |

12 or 13 or 14 |

21 |

|

14 |

(7 and (10 or 11)) not (12 or 13) = observationeel |

14 |

|

13 |

(7 and 9) not 12 = RCT |

4 |

|

12 |

7 and 8 = SR |

3 |

|

11 |

Case-control Studies/ or clinical trial, phase ii/ or clinical trial, phase iii/ or clinical trial, phase iv/ or comparative study/ or control groups/ or controlled before-after studies/ or controlled clinical trial/ or double-blind method/ or historically controlled study/ or matched-pair analysis/ or single-blind method/ or (((control or controlled) adj6 (study or studies or trial)) or (compar* adj (study or studies)) or ((control or controlled) adj1 active) or "open label*" or ((double or two or three or multi or trial) adj (arm or arms)) or (allocat* adj10 (arm or arms)) or placebo* or "sham-control*" or ((single or double or triple or assessor) adj1 (blind* or masked)) or nonrandom* or "non-random*" or "quasi-experiment*" or "parallel group*" or "factorial trial" or "pretest posttest" or (phase adj5 (study or trial)) or (case* adj6 (matched or control*)) or (match* adj6 (pair or pairs or cohort* or control* or group* or healthy or age or sex or gender or patient* or subject* or participant*)) or (propensity adj6 (scor* or match*))).ti,ab,kf. or (confounding adj6 adjust*).ti,ab. or (versus or vs or compar*).ti. or ((exp cohort studies/ or epidemiologic studies/ or multicenter study/ or observational study/ or seroepidemiologic studies/ or (cohort* or 'follow up' or followup or longitudinal* or prospective* or retrospective* or observational* or multicent* or 'multi-cent*' or consecutive*).ti,ab,kf.) and ((group or groups or subgroup* or versus or vs or compar*).ti,ab,kf. or ('odds ratio*' or 'relative odds' or 'risk ratio*' or 'relative risk*' or aor or arr or rrr).ab. or (("OR" or "RR") adj6 CI).ab.)) |

5464865 |

|

10 |

Epidemiologic studies/ or case control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or Case control.tw. or cohort.tw. or Cohort analy$.tw. or (Follow up adj (study or studies)).tw. or (observational adj (study or studies)).tw. or Longitudinal.tw. or Retrospective*.tw. or prospective*.tw. or consecutive*.tw. or Cross sectional.tw. or Cross-sectional studies/ or historically controlled study/ or interrupted time series analysis/ [Onder exp cohort studies vallen ook longitudinale, prospectieve en retrospectieve studies] |

4482444 |

|

9 |

exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw. |

2609251 |

|

8 |

meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (metaanaly* or meta-analy* or metanaly*).ti,ab,kf. or systematic review/ or cochrane.jw. or (prisma or prospero).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or scoping or umbrella or "structured literature") adj3 (review* or overview*)).ti,ab,kf. or (systemic* adj1 review*).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or literature or database* or data-base*) adj10 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((structured or comprehensive* or systemic*) adj3 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((literature adj3 review*) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ti,ab,kf. or (("data extraction" or "data source*") and "study selection").ti,ab,kf. or ("search strategy" and "selection criteria").ti,ab,kf. or ("data source*" and "data synthesis").ti,ab,kf. or (medline or pubmed or embase or cochrane).ab. or ((critical or rapid) adj2 (review* or overview* or synthes*)).ti. or (((critical* or rapid*) adj3 (review* or overview* or synthes*)) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ab. or (metasynthes* or meta-synthes*).ti,ab,kf. |

679922 |

|

7 |

6 and 20110301:20230711.(dt). |

46 |

|

6 |

5 not (comment/ or editorial/ or letter/) not ((exp animals/ or exp models, animal/) not humans/) |

116 |

|

5 |

1 and 2 and 3 and 4 |

121 |

|

4 |

exp "Sensitivity and Specificity"/ or (sensitivity or sensitive or specificity).ti,ab. or (predict* or ROC-curve or receiver-operator*).ti,ab. or (likelihood or LR*).ti,ab. or exp Diagnostic Errors/ or (inter-observer or intra-observer or interobserver or intraobserver or validity or kappa or reliability).ti,ab. or reproducibility.ti,ab. or (test adj2 (re-test or retest)).ti,ab. or "Reproducibility of Results"/ or accuracy.ti,ab. or Diagnosis, Differential/ or Validation Study/ or ((false or true) adj3 (negative or positive)).ti,ab. |

5364131 |

|

3 |

exp Nucleic Acid Amplification Techniques/ or 'pcr'.ti,ab,kf. or 'pcrs'.ti,ab,kf. or 'qpcr'.ti,ab,kf. or 'rtpcr'.ti,ab,kf. or 'polymerase chain reaction*'.ti,ab,kf. or 'poly merase chain reaction*'.ti,ab,kf. or 'polymer ase chain reaction*'.ti,ab,kf. or (('nucleic acid' or dna or rna) adj3 (amplification or test*)).ti,ab,kf. or nat.ti,ab,kf. or naat.ti,ab,kf. or lamp.ti,ab,kf. or ('loop mediated' adj3 amplification).ti,ab,kf. or ((sanger* or 'chain termination') adj3 (sequenc* or method*)).ti,ab,kf. |

1071598 |

|

2 |

(child* or schoolchild* or infan* or adolescen* or pediatri* or paediatr* or neonat* or boy or boys or boyhood or girl or girls or girlhood or youth or youths or baby or babies or toddler* or childhood or teen or teens or teenager* or newborn* or postneonat* or postnat* or puberty or preschool* or suckling* or picu or nicu or juvenile?).tw. |

2912833 |

|

1 |

exp Helicobacter pylori/ or exp Helicobacter Infections/ or exp Helicobacter/ or ((helicobacter or 'h') adj3 pylori).ti,ab,kf. or 'helicobacter'.ti,ab,kf. |

53730 |