Botulinetoxine – bij cerebrale spasticiteit

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de effectiviteit van intramusculaire injecties met botulinetoxine bij volwassenen met cerebrale spasticiteit?

Aanbeveling

Behandel focale spiertonusverhoging als gevolg van cerebrale spasticiteit, welke leidt tot klachten of hinder bij dagelijkse activiteiten, primair met intramusculaire botulinetoxine injecties in een zo laag mogelijke, effectieve dosering. Maak daarbij gebruik van het principe ‘start low and go slow’ en handel zoveel mogelijk binnen de door de fabrikant gestelde doseringskaders per spier. Streef bij herhaling naar de laagst mogelijke behandelfrequentie op basis van terugkeer van symptomen.

Laat botulinetoxine behandeling altijd gepaard gaan met actieve en/of passieve (rek) oefeningen om een zo goed en lang mogelijk functioneel resultaat te bereiken, bij voorkeur op vaardigheidsniveau.

Selecteer de te injecteren spieren voor botulinetoxine injecties op basis van gedegen, liefst interdisciplinaire, functionele diagnostiek en vaststelling van individuele functionele doelen, bij voorkeur op vaardigheidsniveau.

Behandel de onderste extremiteit bij voorkeur op basis van geïnstrumenteerde gangbeeldanalyse (inclusief oppervlakte elektromyografie), vooral indien een verbetering van het lopen (looppatroon en/of loopvaardigheid) wordt nagestreefd.

Evalueer de uitkomsten van de behandeling met botulinetoxine aan de hand van de vooraf vastgestelde doelen.

Behandel pijn bij een spastische parese niet primair met botulinetoxine injecties, tenzij de causaliteit met de spasticiteit overtuigend is.

Streef bij langdurige behandeling met botulinetoxine injecties naar zo lang mogelijke intervallen voor optimale veiligheid en doelmatigheid. Overweeg in deze gevallen ook alternatieve behandelingen zoals orthopedische en neurochirurgische ingrepen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Op basis van de eerdere versie van deze richtlijn kon worden geconcludeerd dat er sterk bewijs is voor het effect van botulinetoxine op vermindering van spiertonus van de bovenste en van de onderste extremiteit, zoals gemeten met de (M)AS. In de herziening werd daarom gekeken naar het behoud en de eventuele versterking van dit effect na meerdere behandelcycli. Alle zes studies die hiernaar hebben gekeken vonden aanwijzingen voor behoud en zelfs een (lichte) verbetering van het tonusreducerende effect na meerdere behandelcycli, zowel voor de bovenste als voor de onderste extremiteit. Dit positieve effect was veel minder uitgesproken in de twee studies die het effect op pijn na meerdere behandelcycli hebben onderzocht. Omdat deze lange termijn effecten alleen werden onderzocht in zogenoemde ‘open-label extension’ (OLEX) periodes, zonder controleconditie, kon de bewijskracht van de lange termijnresultaten niet worden vastgesteld. Ze komen evenwel overeen met de klinische ervaring.

Kijkend naar verschillende studies over de onderste extremiteit vallen de volgende zaken op:

- Twee studies (Kaji, 2010; Kerzoncuf 2020) laten slechts het effect na één behandelcyclus zien, waarbij in beide studies de triceps surae en tibialis posterior van het onderbeen (GCM, GCL, SOL, TP; 300E onabotulinetoxine-A) werden behandeld voor spastische equino(varus). De gemiddelde effectgrootte over spieren en tijdstippen (4-8 weken) in deze studies was een vermindering van de MAS van circa 0.5 punten. Hierbij moet worden aangetekend dat 1 studie (Kaji, 2010) de MAS (een 0-4 schaal met een separate score 1+) niet - zoals gebruikelijk - voor de analyse heeft geconverteerd naar een 0-5 schaal, waardoor deze studie aan meetsensitiviteit verliest.

- Drie andere studies (Gracies, 2017; Wein, 2018; Masakado, 2022) laten zien dat bij herhaalde injecties er een significant grotere tonusafname te zien is. De studie van Gracies (2017) gericht op de triceps surae (GCM, GCL, SOL; totaal 1500E abobotulinetoxine-A) voor pes equinus hanteert na de RCT-fase een open-label extensie met nog eens 4 behandelcycli, waarin de initiële MAS afname van 0.6 punt (RCT-fase) toeneemt tot een afname van 1.0 vanaf de 2e extra cyclus. Daarna is er een stabiel effect van 1.0 punt in vergelijking met baseline. De studie van Wein (2018) gericht op de dorsale spieren van het onderbeen (GCM, GCL, SOL, TP; 300E onabotulinetoxine-A) voor pes equinovarus hanteert na de RCT-fase een open-label extensie van 3 behandelcycli, waarbij de initiële MAS afname van 0.8 punt toeneemt tot een afname van ca 1.3 punt (stabiel vanaf 1e extra cyclus). Van belang is ook dat Wein (2018) de proportie deelnemers vergelijkt die na 1 cyclus (RCT-fase) een verbetering van tonus laten zien van minimaal 1.0 punt op de MAS. Deze is over alle tijdspunten na injectie (2, 4, 6, 8, 12 weken) significant groter in de behandelde groep in vergelijking met placebo, met een NNT (number-needed-to-treat) van 8 (bij 2,4, 6 weken) en 11 (bij 8,12 weken). In de open-label fase, vanaf de 1e extra cyclus, laat 76% van de patiënten een verbetering van minimaal 1.0 punt op de MAS zien. In de studie van Masakado (2022) gericht op de plantairflexoren, neemt de gemiddelde MAS na elke behandelcyclus iets af, waar er na 4 cycli een afname van 0.83 is.

Bij langdurig gebruik van botulinetoxine is van belang om te beoordelen of de kans op bijwerkingen in de tijd toeneemt. In de eerste versie van de richtlijn waren er geen aanwijzingen dat bijwerkingen, van welke aard ook (b.v. pijn, infecties, spierzwakte), bij CVA patiënten vaker zouden voorkomen na BoNT-A dan na placebo injecties. Op basis van de bevindingen in deze richtlijn kan nog steeds dezelfde conclusie worden getrokken. Met betrekking tot de kans op een valincident laten de studies van de onderste extremiteit zien dat het aantal vallers na meerdere behandelcycli tussen de 1% en 6% ligt. Dit getal afkomstig uit de OLEX data kan niet worden vergeleken met een controleconditie, maar is relatief laag en past bij het feit dat patiënten met een CVA een aanzienlijk grotere valkans hebben dan gezonde leeftijdsgenoten.

In deze eerdere versie van deze richtlijn werd ook vastgesteld dat er redelijk sterk bewijs is voor het feit dat botulinetoxine de passieve vaardigheden van de bovenste extremiteit na CVA verbetert. Daarbij kan worden gedacht aan het aantrekken van een jas of een handschoen, maar ook het verzorgen of positioneren van de aangedane arm en hand. Dit heeft naar verwachting gunstige consequenties voor de kwaliteit van leven, maar dit werd niet gemeten in de betreffende studies. Op basis van de OLEX data in deze richtlijn (Masakado, 2020) kan worden geconcludeerd dat dit gunstige effect op passieve vaardigheden na meerdere behandelcycli behouden blijft en zelfs nog wat verder toeneemt. De bewijskracht hiervan kon niet worden vastgesteld, maar ook dit resultaat is congruent met klinische ervaring. Het veronderstelde incrementele effect op spiertonus én op passieve arm-handvaardigheid kan ertoe leiden dat in de klinische praktijk bij deze doelgroep soms een behandelinterval langer dan de gebruikelijk 3 maanden kan worden bereikt, vooral als parallel aan de BoNT-A behandeling met succes kan worden ingezet op rek- en steunoefeningen van de bovenste extremiteit.

Wat betreft het verbeteren van actieve vaardigheden door inzet van BoNT-A behandeling kon geen evidentie worden gevonden; niet na een enkelvoudige injectie in gecontroleerd onderzoek, en niet na meervoudige behandelcycli in ongecontroleerde OLEX perioden. Hierbij is het van belang dat voor de bovenste extremiteit 4 studies hebben gekeken naar het add-on effect van BoNT-A ten opzichte van placebo bij gelijktijdige fysiotherapiebehandeling (Prazeres, 2018; Wallace, 2020), neuromusculaire elektrostimulatie (Lindsay, 2021), of ‘usual care’ (Ward, 2014). Alle 4 studies, waarvan slechts één met de mogelijkheid tot meerdere behandelcycli, toonden geen meerwaarde van BoNT-A voor het verwerven van actieve vaardigheid, waardoor deze conclusie met redelijke zekerheid kan worden getrokken, in ieder geval voor de korte termijn (één behandelcyclus).

Voor wat betreft de onderste extremiteit toonden twee van de drie studies met een OLEX periode (Gracies, 2017; Wein 2018) wel aanwijzingen voor het feit dat de loopsnelheid zou kunnen verbeteren na meerdere behandelcycli, tot wel 25% na 4 cycli (Gracies, 2017), ondanks het feit dat geen van beide studies duidelijk melding maakt van parallelle oefentherapie. Ook waren er aanwijzingen voor hogere scores op de Clinician Global Impression Scale (CGI) of de Physician Global Assessment (PGA) in 3 studies (Kaji, 2010; Wein, 2018; Gracies, 2017) en op het behalen van individuele (passieve) doelen (Wein, 2018). De klinische ervaring leert dat gerichte BoNT-A injecties bij goed geselecteerde CVA patiënten ook kunnen helpen om het looppatroon te verbeteren. Bekende voorbeelden hiervan zijn (niet uitputtend) BoNT-A behandeling van:

- m. soleus om hinderlijke knie-overstrekking tijdens de standfase van het gaan te verminderen.

- m. tibialis posterior om hinderlijke inversieneiging tijdens de standfase van het gaan te verminderen.

- teenflexoren om hinderlijk teenklauwen tijdens de standfase van het gaan te verminderen.

- m. rectus femoris om voldoende knieflexie tijdens de zwaaifase van het gaan te verkrijgen.

Er zouden derhalve meer gecontroleerde studies moeten komen die, behalve naar progressieve verbetering van de loopsnelheid en loopafstand na meerdere behandelcycli en in combinatie met gerichte oefentherapie, gericht kijken naar de verbetering van het looppatroon, bijv. gunstige beïnvloeding van pes equinovarus, waardoor minder behoefte aan een orthesevoorziening, of van ‘stiff knee gait’, waardoor minder risico op struikelen en vallen.

Tot slot dient nog te worden opgemerkt dat, zowel voor de bovenste als onderste extremiteit, (herhaalde) BoNT-A injecties ook kunnen worden gebruikt om - bij ernstige spasticiteit - rekoefeningen te vergemakkelijken, met als doel op de langere termijn spierverkortingen te voorkómen. Spierverkortingen hebben immers een grote impact op de bewegingsvaardigheid en zijn bij volwassenen zeer lastig te behandelen door intensieve rektherapie (zie module Passief rekken). In dergelijke gevallen rest dan alleen nog chirurgische interventie (zie module Chirurgische behandelingen aan de bovenste en onderste extremiteit).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers):

Het is van groot belang dat focale spasticiteitsbehandeling middels BoNT-A injecties zoveel mogelijk gebeurt op basis van ‘shared decision making’ en het stellen van individuele doelen. In het algemeen zijn patiënten met cerebrale spasticiteit en/of hun naasten/verzorgers goed in staat om hierover actief mee te denken, evenals over mogelijke (focale) behandelalternatieven (zie module Organisatie van zorg). Het vertalen van behandeldoelen naar een behandelplan gericht op geselecteerde spieren is primair aan de behandelend arts, waarbij het in complexe gevallen aan te bevelen is om paramedici (i.h.b. fysiotherapeut en/of ergotherapeut) te consulteren om het behandelplan te optimaliseren. Voor de onderste extremiteit, bij het streven naar een gunstig effect op het lopen, verdient het de aanbeveling om – voordat met BoNT-A behandeling wordt gestart – een vorm van geïnstrumenteerde gangbeeldanalyse met oppervlakte-EMG in te zetten. Alleen middels een geïnstrumenteerde gangbeeldanalyse kan worden vastgesteld of een spier die bij lichamelijk onderzoek als ‘spastisch’ wordt geïdentificeerd, ook daadwerkelijk hinderlijk actief is tijdens het lopen.

Qua timing zijn er aanwijzingen dat botulinetoxine mogelijk effectiever is wanneer vroeg gestart wordt na CVA (binnen 3 maanden) ten opzichte van starten tussen 3 tot 6 maanden na CVA. Ook in de chronische fase lijkt een vroege start van de behandeling geassocieerd met een betere uitkomst. Dit is echter gebaseerd op schaarse en niet consistente literatuur (zie ook Module 14).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Behandeling met BoNT-A injecties wordt in de 2e en 3e lijn vergoed op basis van daarvoor beschikbare revalidatiegeneeskundige DBC’s. In het verpleeghuis (of andere instelling voor langdurige zorg) kan BoNT-A behandeling ook worden vergoed door de zorgverzekeraar, mits er sprake is van een DBC uitgevoerd door een revalidatiearts, en mits er sprake is van een ‘eigen zorgvraag’ vanuit de patiënt. Het eigen risico is hierbij van toepassing en de behandeling valt onder een eventueel productieplafond zoals afgesproken met het revalidatiecentrum of ziekenhuis waar de revalidatiearts werkzaam is. De revalidatiearts mag geen DBC openen als er sprake is van een vraag gericht op verbetering van de verzorgbaarheid, gesteld vanuit het behandelteam in de betreffende instelling. Er dient dan sprake te zijn van onderlinge dienstverlening, welke door de instelling moet worden bekostigd.

Gezien de goede resultaten is het verantwoord dat BoNT-A behandeling uit algemene middelen c.q. het basispakket wordt bekostigd. Daarbij dient rekening te worden gehouden met het feit dat BoNT-A injecties geen stand-alone behandeling horen te zijn, onderdeel zijn van een step-up benadering, en dat goed gemonitord wordt of de behandeling effectief is. Het advies is om bij onvoldoende resultaat de behandeling te staken.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Behandeling met BoNT-A injecties blijkt in de 2e en 3e lijn zeer aanvaardbaar en haalbaar, hoewel er in sommige revalidatiecentra en ziekenhuizen een tekort is aan professionals die over de juiste vaardigheden beschikken of een tekort aan behandelcapaciteit om andere redenen. Dit vormt een reëel risico op onderbehandeling. Dit risico is uiteraard nog groter in andere instellingen, zoals de verpleeghuis- en VG-sector.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Onderstaande aanbevelingen zijn, behalve op basis van bovengenoemde overwegingen, gebaseerd op de bevindingen en aanbevelingen zoals vermeld in de eerdere versie van deze richtlijn.

Onderbouwing

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Effects of single injection cycle

1a. active skills and abilities

|

LOW GRADE |

Botulinum toxin may result in little to no difference in active skills and abilities when compared to placebo in patients with upper limb spasticity due to stroke.

Sources: (McCrory, 2009; Lindsay, 2021; Rosales, 2012; Wallace, 2020) |

|

LOW GRADE |

Botulinum toxin may result in little to no difference in active skills and abilities when compared to placebo in patients with lower limb spasticity due to stroke.

Sources: (Gracies, 2017; Kaji, 2010; Kerzoncuf, 2020; Masakado, 2022; Wein, 2018) |

2. Effects of multiple injection cycles

2a. Active skills and abilities

|

LOW GRADE |

Botulinum toxin may result in little to no difference in active skills and abilities when compared to placebo in patients with upper or lower limb spasticity due to stroke.

Sources: (McCrory, 2009; Masakado, 2022; Gracies, 2017; Wein, 2018) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Twelve studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are shown in table 2. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables. First, the studies only injecting 1 cycle of BoNT-A are described, and subsequently the studies assessing multiple injection cycles.

Description of studies

The study characteristics of all 12 studies on BoNT-A for stroke-related spasticity are summarized below in table 2.

1. Evaluation after single injection cycle

(Upper extremity) Lindsay (2021) evaluated the effect of BoNT-A injections on arm-hand ability using the Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) among stroke patients in a tertiary care unit who had developed spasticity and scored two or lower on the grasp subsection of the ARAT. Patients were randomized using random permuted blocks in pseudorandom sequence, in which 45 patients were injected with predetermined doses of BoNT-A in all six muscles of the affected arm, and 48 patients injected similarly with sodium-chloride as placebo. Electrical stimulation of the wrists was provided as therapy to all patients in the trial. This RCT entailed independent research funded by the NHIR. BoNT-A was provided by Allergan, but they had no other role in this study. The authors declared having received honorarium and funding to attend courses from Allergan, Ipsen and Merz as potential conflicts of interests.

(Upper extremity) Wallace (2020) studied the effect of BoNT-A (100 units) on arm-hand ability compared to placebo, among 28 hospitalized adult stroke patients presenting with focal spasticity with a MAS of ≥2 in the affected joint. Injection sites were identified using electrical stimulation. In this study, all enrolled patients received 10 sessions of intensive standardized physiotherapy over 4 weeks. This study assessed the ARAT and the Nine-hole peg test as outcome measures. The study was funded by the UK Stroke Association. As potential conflicts of interests, some authors declared receiving honoraria and consultancy fees of several pharmaceutical companies, including Allergan.

(Upper extremity) Rosales (2012) was included from the previous version of this guideline, and studied the efficacy and safety of early administration of BoNT-A in patients with upper limb spasticity, who had experienced a first stroke 2 to 12 weeks prior, with a MAS score of at least 1+ in the wrist or elbow joint. A total of 163 patients were enrolled, of which 83 received a placebo and 80 received 500 units of BoNT-A injected into the affected muscles. Outcomes of interest were the Barthel Index and Motor Assessment Scores of hand and upper arm. The study was sponsored by Ipsen.

(Lower extremity) In another multicenter RCT, Kerzoncuf (2020) assessed the effects of injecting BoNT-A into the lower limb muscles of people with hemiparesis at least 12 months post-stroke, specifically to measure balance impairments in terms of patients’ postural sway. Patients were randomized to receive either a maximum dose of 300 units (n = 23) or placebo injection (n = 26). Sway area and walking speed were assessed. The study was funded by the Protocole Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique. One author declared potential conflicts of interest with Allergan, Merz, and Ipsen.

(Lower extremity) Kaji (2010b) was included form the previous version of this guideline, and investigated the efficacy and safety of single injections of BoNT-A in patients with spasticity in the lower limbs due to stroke. A total of 300 units was injected. In total, 120 patients were included, with 58 patients randomized to the active arm and 62 patients to the placebo arm. The study assessed gait speed (10m Walking Test) after 12 weeks. This study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline.

(Both extremities) Prazeres (2018) assessed whether BoNT-A injections with physical therapy as add-on (n = 20) were superior to sham injection and physical therapy (n=20) in patients with post-stroke spasticity. Treatment dose and injected muscles were not reported for the intervention arm. The control-arm received placebo injections prepared with saline solution. Besides BoNT-A and placebo, all patients were included in a standardized protocol of physical exercises including muscle strength, endurance, functional training and flexibility for three months, with two weekly sessions of 30 minutes. Outcomes assessed were the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, and 6-min walking test. The ratio of upper- and lower-limb spasticity patients was not reported; spasticity was only reported using the MAS elbow score and MAS wrist score. The study was funded by the Brazilian National Institutes of Science, CAPES, and UFBA and authors declared no conflicts of interest.

2. Evaluation after single and multiple injection cycles

(Upper extremity) The RCT by Masakado (2020) evaluated the efficacy of a single BoNT-A injection (400 units) compared to placebo. A total of 100 adult patients with unilateral post stroke upper-limb spasticity were randomized, who had a MAS of either ≥ 3 for wrist flexors or ≥2 for finger flexors, a Disability Assessment Scale (DAS) of ≥ 2 for at least one functional domain, and a clinical need for 400 units of botulinum toxin. Patients received either BoNT-A 400 units; a high-dose placebo; BoNT-A 250 units; or a low-dose placebo at a ratio of 4:2:2:1. This study also included an open-label extension period (OLEX) starting at week 12. This OLEX period was not controlled by a placebo group and duration was up to an additional 32-40 weeks, with 3 additional injection cycles (ranging from 10-14 weeks). Outcomes of interest from the OLEX were 10-meter Walking Test, DAS, MAS and adverse events. The study was funded Merz Pharmaceuticals, and three authors were either employee or consultant for the company.

(Upper extremity) McCrory (2009) compared two cycles of BoNT-A-injections to placebo in patients with cerebral spasticity of the upper limbs following a stroke. A dose of 750-1000 units of BoNT-A was administered. The selection of muscles and single or multiple injection sites per muscle were at the discretion of the treating physician. A total of 96 patients were included, with 54 receiving botulinum toxin injections and 42 receiving a placebo. Patients received re-treatment at week 12 with a total dose range of 500 to 1000 units according to their response in the first treatment cycle. This study was funded by Ipsen, who had no influence on the interpretation of data and the final conclusions drawn.

(Lower extremity) The multicenter RCT of Masakado (2022) investigated the efficacy and safety of a single BoNT-A injection cycle compared to placebo, among adult patients with unilateral lower limb spasticity with equinus foot deformity caused by a stroke that occurred at least 6 months prior to enrolling. Patients were only enrolled if there was a clinical need for 400 units of BoNT-A, which was decided based on the patient’s spasticity status and expected improvement BoNT-A could provide, according to the investigator. The study included a main period and open-label extension (OLEX) period. Patients (n = 208) were randomized to either 400 units of BoNT-A (n = 104) or placebo (n = 104). Besides muscle tone (MAS), pain (Patient’s Assessment of Spasticity, Pain and Spasms scale), walking speed (10-min walking test) and adverse events were assessed. The OLEX period started at week 12 and was not controlled by a placebo group. Duration was up to an additional 32-40 weeks, with 3 additional injection cycles (ranging from 10-14 weeks). The study was funded by Merz Pharmaceuticals. Conflicts of interests were not reported, but three authors were employees at Merz Pharmaceuticals.

(Lower extremity) Wein (2018) assessed the efficacy and safety of BoNT-A injections for treating post-stroke lower limb spasticity of the ankle in a multicenter RCT carried out in Europe, North America, Russia and Asia. Adult patients (n = 468) were included when they had a MAS score of ≥ 3 in the affected ankle, had an equinus or equinovarus foot deformity and a stroke at least 3 months before enrollment. In the intervention group (n = 233), 300 units of BoNT-A were injected, evenly distributed over 4 predetermined leg muscles (75 units per muscle). When clinically indicated, an optional dose of 100 units or lower could be injected into additional muscles. Outcome measures were MAS and walking speed. After completing the 12-week double blind period, eligible patients of both the intervention- and placebo group entered the open-label extension (OLEX) of the study, in which patients could receive up to 400 unit of BoNT-A at approximately 12-week intervals in three more cycles. The study was funded by Allergan. Two of the authors were Allergan employees.

(Lower extremity) In a multicenter RCT among adults with chronic hemiparesis due to stroke, Gracies (2017) assessed the efficacy and safety of BoNT-A injections of either 1000 units (n=125) or 1500 units (n=128) when compared to placebo (n= 128). Both intervention and control consisted of a single injection into both the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles in the calf and one or more other lower limb muscles, as selected by the investigator. Outcomes of interest were speed in the 10-meter Walking Test, muscle tone (MAS) and adverse events.

This study included an open-label extension (OLEX) starting at week 12 with a second injection of 1500 units. After that, patients were retreated after 12, 16, 20, or 24 weeks, based on the investigator’s judgement. This study was sponsored by Ipsen and four of the authors were Ipsen employees.

(Both extremities) In a multicenter RCT, Ward (2014) assessed change in muscle tone and adverse events when comparing BoNT-A plus standard of care (SC) with placebo plus SC in patients with post-stroke spasticity in either the upper or lower limbs. The study randomized 273 patients with spasticity due to a cerebrovascular accident; 139 patients received injections at baseline and after 12 weeks with a maximum of 800 units at the discretion of the treating physician, and 135 received a placebo injection. Patients could receive a second dose at a minimum of 12 weeks, if the treating physician thought they would benefit from a second treatment. After this, patients could enter the open-label extension (OLEX), in which patients from both treatment arms were eligible to receive BoNTA- injections, with a minimum inter-injection interval of 12 weeks. Follow-up was 1 year. The study was conducted in Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Canada and funded and cowritten by Allergan.

Table 2. study characteristics, outcome measures and results for cerebral spasticity

|

Study; design |

Sample size |

Type and characteristics BoNTA |

Type and characteristic Placebo |

Outcomes of interest reported Study quality assessment |

Length of follow-up |

Remarks regarding sponsoring |

|

||||||

|

Lindsay, 2021 RCT |

93 |

onabotulinumtoxin-A injections to six muscles of the affected arm in predetermined doses + Electrical stimulation to the wrist extensors, n = 45 |

Placebo (0.9 mg of sodium chloride injection) + Electrical stimulation to the wrist extensors n = 48 |

Moderate risk of bias |

12 weeks |

Allergan provided study drug; no other role within this study. |

|

Wallace, 2020 RCT |

28 |

onabotulinumtoxin-A + standardized physiotherapy with 10 sessions in 4 weeks n= 14 |

Placebo injection (saline) + standardized physiotherapy with 10 sessions in 4 weeks n = 14 |

Low risk of bias |

5 weeks |

Study funded by the UK Stroke Association |

|

Rosales, 2012 RCT |

163 |

abobotulinumtoxinA 500 U n = 80 |

Placebo (visually identical) n = 83 |

Moderate risk of bias |

4 weeks, 12 weeks, |

Study was funded by Ipsen |

|

Kerzoncuf, 2020 RCT |

40 |

onabotulinumtoxin-A injection, maximum dose 300 U n = 23 |

Placebo (physiologic serum) n = 26 |

Moderate risk of bias |

4-6 weeks |

Study was funded by the Protocole Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique. |

|

Kaji, 2010 RCT |

120 |

onabotulinumtoxin-A single injection of 300 U + 75 U into 4 muscles n = 58 |

Placebo (visually identical, same amount of injection) n = 62 |

Moderate risk of bias |

4 weeks, 12 weeks |

Study sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline |

|

Prazeres, 2018 RCT |

40 |

onabotulinumtoxin-A (dose not reported) + physical therapy according to a standardized protocol including muscle strength, flexibility, endurance and functional training twice a week n = 20 |

Placebo (saline solution) + physical therapy according to a standardized protocol including muscle strength, flexibility, endurance and functional training twice a week n = 20

|

Low risk of bias |

12 weeks |

Study funded by the Brazilian National Institutes of Science, CAPES, and UFBA and authors declared no conflicts of interest |

|

||||||

|

Masakado, 2020 RCT |

100 |

Incobotulinumtoxin-A injections n1 (high 400 U) = 44 n2 (low 250 U) = 23 |

2 groups: high dose placebo, n=22 low dose placebo, n=11 |

High risk of bias |

4 weeks, 12 weeks OLEX: 24 weeks, 36 weeks, 48 weeks |

Study funded by Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH, and three authors are either employee or consultant for the company |

|

McCrory, 2009 RCT |

96 |

Abobotulinumtoxin-A, with a total dose range of 750-1000 U, re-treatment at week 12. n = 54 |

Placebo (visually identical) n = 42 |

Low risk of bias |

20 weeks |

Study funded by Ipsen, who had no influence on the interpretation of data and the final conclusions drawn. |

|

Masakado, 2022 RCT |

208 |

single injection cycle of incobotulinumtoxin-A 400 U in the plantar flexors n = 104 |

Placebo (visually identical) n = 104 |

Moderate risk of bias |

4 weeks, 12 weeks OLEX: 24 weeks, 36 weeks, 48 weeks |

Study funded by Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH, conflicts of interests were not reported, but three authors were employees at Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH. |

|

Wein, 2018 RCT |

468 |

onabotulinumtoxin-A 300 U, with optional additional =<100 U n = 233 |

Placebo (0.9 mg of sodium chloride injection) n = 235 |

Moderate risk of bias |

4 weeks, 12 weeks OLEX: 24 weeks, 36-42 weeks, 60 weeks |

Study was funded by Allergan plc;. two of the authors were Allergan employees |

|

Gracies, 2017 RCT |

381 |

one lower limb injection abobotulinumtoxin-A 1000 U (n = 125); abobotulinumtoxin-A 1500 U) (n = 128) |

Placebo (not reported) n = 128 |

High risk of bias |

4 weeks, 12 weeks, OLEX: 24 weeks, 36 weeks, 48 weeks |

Study was sponsored by Ipsen; four of the authors were Ipsen employees |

|

Ward, 2014 RCT |

273 |

onabotulinumtoxin -A, maximum dose of 800 U. Combined with standard of care. Optional re-injection at 12-24 weeks n = 139 |

Placebo + standard of care (SC), which could be more intensive care than prior to study, such as physical therapy, occupational therapy and SC focused on active functional goal achievement n= 134 |

High risk of bias |

12 weeks after first injection, 10 weeks after second injection, OLEX: 12 months |

Allergan employees were involved in: (i) the design and conduct of the study; and (ii) the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the study data. The authors had sole control over the preparation, review, and approval of this manuscript. |

*Abbreviations: ARAT= Action Research Arm Test; AS= Ashworth score; DAS= Disability Assessment scale; LS = least squares analysis; MAS = Modified Ashworth score; MMAS = Modified Motor Assessment Scale NHPT= Nine-hole peg test; TUG= Timed up-and-go test; VAS= Visual Analogue Scale

Results

Below the results are addressed in the following order:

- After single BoNT-A injection

-

- 1a. Active skills and abilities

- After multiple BoNT-A injection cycles

-

- 2a. Active skills and abilities

- 2b. Passive skills and abilities

- 2c. Muscle tone

- 2d. Pain

- 2e. Adverse events

When no mean group difference (MD) was provided for post-intervention scores, these were calculated based on means and standard deviation using Review Manager. Change-from-baseline MDs were used if post intervention scores were not available.

1. Evaluation after a single injection cycle

1a. Active skills and abilities

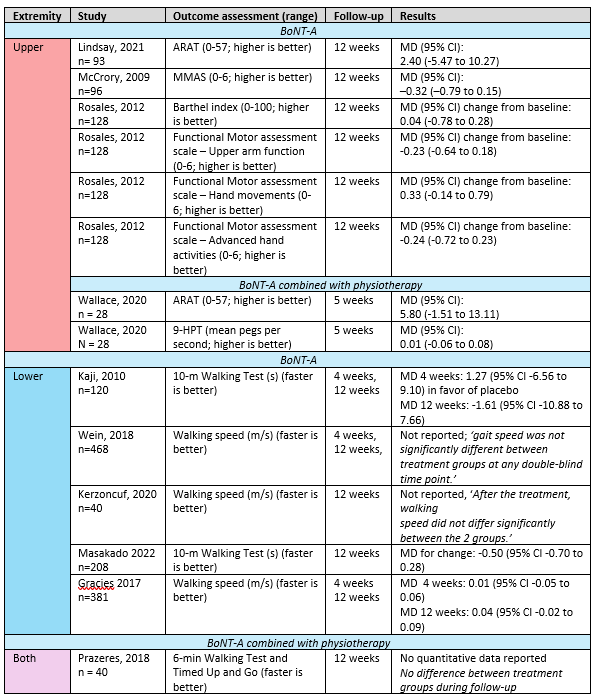

Ten RCTs reported on one or more active functional outcome measures; four in the upper extremity, five in the lower extremity and one in both extremities. In Table 3, the studies, their outcome measures (split up for upper and lower extremity, and for the use of concomitant physical therapy) and the mean group differences are shown.

Data could not be pooled due to heterogeneity in outcome measurements, control groups and follow-up assessment. For all outcomes, no clinically relevant difference was found between BoNT-A and control.

Table 3. Active skills and abilities in stroke patients with spasticity

Abbreviations: 9-HPT: 9-hole peg test, ARAT: Action Research Arm Test, CI: confidence interval, MD: Mean difference, MMAS: Modified Motor Assessment Scale

2. Evaluation after multiple injection cycles

2a. Active skills and abilities

Upper extremity

McCrory (2009) assessed active motor ability via the Modified Motor Assessment Scale (MMAS) after more than one injection cycle comparing BoNT-A with control at 20 weeks. They reported an MD of –0.22 (95% CI –0.75 to 0.31) in favor of BoNT-A. However, this was not significant or clinically relevant.

Lower extremity

Three other studies reported long-term active skills and abilities regarding the lower extremities. However, they were open-label extension (OLEX) of controlled studies, so no comparison with control could be made, and results below are descriptive.

In the study from Masakado (2022) 176 of the 201 patients that entered the OLEX ended the trial, but the final measurement of the 10-meter Walking Test after approximately 36 weeks of treatment in the OLEX period was reported for only 93 patients. A mean change from baseline of -0.2 m/s (SD: 10.2) was found, which is not clinically relevant.

In Gracies (2017) 136/352 patients entering the OLEX were treated for four cycles and had a final assessment. They reported that barefoot walking speed progressively increased across treatment cycles. It had increased 25.4% (95% CI 17.5 to 33.2) at week 4 of cycle 4 compared to baseline, which is clinically relevant.

Wein (2018) assessed gait speed as well, but did not report any outcome data for the OLEX. However, they stated that gait speed scores generally improved within three treatment cycles.

2b. Passive skills and abilities

Upper extremity - Masakado (2020) assessed passive arm-hand abilities via the Disability Assessment Scale (DAS; range 0-3) at week four of each open-label injection cycle (cycles two to four) during their open-label extension of 36 weeks. Least squares mean difference between groups after 8 weeks during the controlled period of the study was 0.40 for BoNT-A 400U and 0.53 for BoNT-A 250U.

During the OLEX period, the mean change from study baseline increased each cycle with BoNT-A, as the mean absolute changes in DAS scores (SD) after injection cycles two, three and four were 0.78 (0.83), 0.94 (0.87), and 0.99 (0.91), respectively. DAS score improved more among patients who had received BoNT-A in the main blinded-period than in those who received placebo, but no difference between high (400 units) and low (250 units) dose in main period was observed for DAS after more injection cycles.

2c. Muscle tone

Muscle tone after more than one injection cycle was measured in two studies for the upper extremity, three studies for the lower extremity and one for both extremities, using the Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS) (ranging from 0 to 5). Three studies did so in the open-label extension period of their RCT, and did therefore not compare it to a control. All studies suggested further muscle tone improvements across repeated injection cycles.

Table 4. MAS scores in stroke patients with spasticity

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval, MD: Mean difference, REPAS-26: REsistance to PAssive movement Scale Summated

2d. Pain

Upper extremity

McCrory (2009) assessed pain using a visual analogue scale (VAS), ranging from 0 to 100. At 20 weeks (after two injection cycles) they found a mean difference (MD) in change from baseline of 10.14 (-8.1 to 27.4) between BoNT-A (n= 53) and placebo (n=38). This effect did not reach the predetermined level of clinical relevance (16.5).

Lower extremity

One study reported on the effect of more than one BoNT-A injection on pain. Masakado (2020) did not compare pain between BoNT-A and control, but reported on pain in their open-label extension (OLEX) period via the Ankle pain score item of the Patient’s Assessment of Spasticity, Pain and Spasms scale. They reported a further decrease in pain in the second injection cycle, after which the pain scores remained stable with a mean (SD) change from baseline at week 4 of cycle 2 of -1.0 (2.7), and -1.1 (2.7) in week four of cycles three and four.

2e. Adverse events

Only one study reported the comparison of adverse events after multiple injection cycles (after 24 weeks;McCrory, 2009). In the BoNT-A group, 36 out of 54 (66.7%) experienced adverse events, and 26 out of 42 (61.9%) in the control group (RR 1.08; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.46).

Ward (2014) monitored the occurrence of treatment emergent adverse events for both BoNT-A (n = 139) and placebo (n = 134) for 24 weeks. This resulted in an RR of 1.17 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.89) and an RD of 0.04 (-0.08 to 0.16). This was not a statistically significant or clinically relevant difference.

Of which were falls:

Upper extremity

McCrory (2009) reported on the difference of falling events after two BoNT-A injection cycles (n = 54) when compared to placebo injection (n = 42). This resulted in an RR of 0.58 (95% CI 0.22 to 1.55), an RD of -0.08 (95% CI -0.22 to 0.07) and NNT of 13 in favor of BoNT-A (reduction of falls in BoNT-A). This is a clinically relevant difference.

Lower extremity

Two studies described the amount of falling events among patients receiving more than one BoNT-A injection.

Masakado (2022) reported falling events for their OLEX injection cycles. In the second injection cycle, 2/202 (1%) patients experienced a falling event. In cycle three and four no patients experienced any falling events. Gracies (2017) also reported the number of falling events in their OLEX injection cycles. In the first cycle of their OLEX, 17/345 (5%) patients experienced a falling event. In cycle two, three, and four, this was 17/297 (6%), 9/224 (4%) and 5/139 (4%) respectively.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for every outcome started as high, since it was based on RCTs. Publication bias was not assessed.

|

Outcome measure |

Domains |

Level of evidence |

|

|

Single injection cycle |

Active skills and abilities |

Upper and lower extremities: -1 risk of bias of included studies, -1 imprecision (confidence interval crossing the border of clinical relevance) |

LOW |

|

Multiple injection cycles |

Active skills and abilities |

Upper and lower extremities: -1 risk of bias of included studies, -1 imprecision (confidence interval crossing the border of clinical relevance) |

LOW |

|

Passive skills and abilities |

Non-controlled studies assessed, therefore no GRADE applied |

NO GRADE |

|

|

Muscle tone |

Non-controlled studies assessed, therefore no GRADE applied |

NO GRADE |

|

|

Pain |

Non-controlled studies assessed, therefore no GRADE applied |

NO GRADE |

|

|

Adverse events |

Non-controlled studies assessed, therefore no GRADE applied |

NO GRADE |

|

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness of intramuscular botulinum toxin-injections as compared to usual care, placebo and/or physical therapy in adults with cerebral or spinal spasticity?

| P: | Patients with cerebral or spinal spasticity and bothersome focal spasticity |

| I: | Intramuscular injections with botulinum toxin (with or without exercise therapy) |

| C: | Placebo injections (with or without exercise therapy) or usual care |

| O: |

1. after single injection cycle: effects on active skills and abilities (e.g. reaching, grasping, balance, walking, ADL) 2. after multiple injection cycles: effect on active skills and abilities, spasticity symptoms (i.e. muscle tone, cramps, pain), passive abilities, and adverse events (e.g. falling) |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered effects on active skills and abilities as crucial outcome measures for decision making; and effects on spasticity symptoms, passive skills and abilities, adverse events and falling as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Definitions and minimal clinically important differences for assessed outcome measures

|

Outcome units |

Outcome measures |

Definition |

Minimal clinically (patient) important difference |

|

After single injection cycle ánd two or more injection cycles (separately) |

|||

|

Effects on skills and abilities |

Active skills / abilities |

For example measured with:

|

12 points on the ARAT, 0.1 m/s gait speed difference for 10-meter WT; 54 meter difference for 6MWT (Wise, 2005); 6 points on Berg Balance Scale |

|

Activities of Daily Living (ADL) |

For example using Barthel Index |

Barthel Index: 1.85 points (Hsieh, 2007) |

|

|

Only after two or more injection cycles |

|||

|

Effects on skills and abilities |

Passive skills / abilities |

Measured with the Disability Assessment Scale (DAS) |

10% change on mean DAS |

|

Effects on body functions and structures (impairments) |

Muscle tone |

measured with the (modified) Ashworth scale (AS), Penn Spasm Frequency Scale (PSFS) or (modified) Tardieu scale (TS) |

1 point on the (m)AS, PSFS or (m)TS |

|

Cramps and pain |

measured with Visual Analogue Scale, or Numeric (Pain) Rating Scale |

1.65 points difference (scale 0 to 10) or 16.55 (scale 0 to 100) (Bahreini, 2020) |

|

|

Adverse events |

See glossary of terms |

||

The working group defined a 25% difference for both continuous outcome measures and dichotomous outcome measures informing on relative risk (RR ≤ 0.80 and ≥ 1.25) as clinically relevant. For standardized mean difference (SMD) an SMD >0.5 was considered clinically relevant.

Search and select (Methods)

In a previous version of this module, literature from 2000 until 2015 was searched and studies were selected based on a similar PICO (see appendix 1). From this previous search, 5 studies fulfilled the selection criteria above and were included in this update.

To update the guideline, the databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms in an additional search from September 2015 until 22nd of August 2023. The detailed search strategy is available upon request. The systematic additional search resulted in 849 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses.

- Included adults with cerebral or spinal spasticity.

- Described intramuscular botulinum toxin injections as intervention.

- Described placebo (with or without physical therapy) or usual care as comparison.

- Described at least one of the outcome measures as described in the PICO.

- Were published in the English language.

- Included at least ten participants per treatment-arm.

From this additional search, 49 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 40 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 9 studies were included.

Together with the 5 studies eligible from the previous search, this results in 14 included studies, of which 12 studies about stroke, one about MS and one about spinal cord injury.

Referenties

- Bahreini M, Safaie A, Mirfazaelian H, Jalili M. How much change in pain score does really matter to patients? Am J Emerg Med. 2020 Aug;38(8):1641-1646. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.158489. Epub 2019 Nov 4. PMID: 31744654.

- Gracies JM, Esquenazi A, Brashear A, Banach M, Kocer S, Jech R, Khatkova S, Benetin J, Vecchio M, McAllister P, Ilkowski J, Ochudlo S, Catus F, Grandoulier AS, Vilain C, Picaut P; International AbobotulinumtoxinA Adult Lower Limb Spasticity Study Group. Efficacy and safety of abobotulinumtoxinA in spastic lower limb: Randomized trial and extension. Neurology. 2017 Nov 28;89(22):2245-2253. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004687. Epub 2017 Nov 1. PMID: 29093068; PMCID: PMC5705248.

- Hsieh YW, Wang CH, Wu SC, Chen PC, Sheu CF, Hsieh CL. Establishing the minimal clinically important difference of the Barthel Index in stroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2007 May-Jun;21(3):233-8. doi: 10.1177/1545968306294729. Epub 2007 Mar 9. PMID: 17351082.

- Kaji R, Osako Y, Suyama K, et al. Botulinum toxin type A in post-stroke lower limb spasticity: A multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Neurology. 2010b;257(8):1330-7.

- Kerzoncuf M, Viton JM, Pellas F, Cotinat M, Calmels P, Milhe de Bovis V, Delarque A, Bensoussan L. Poststroke Postural Sway Improved by Botulinum Toxin: A Multicenter Randomized Double-blind Controlled Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020 Feb;101(2):242-248. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2019.04.024. Epub 2019 Aug 27. PMID: 31469982.

- Lindsay C, Ispoglou S, Helliwell B, Hicklin D, Sturman S, Pandyan A. Can the early use of botulinum toxin in post stroke spasticity reduce contracture development? A randomised controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2021 Mar;35(3):399-409. doi: 10.1177/0269215520963855. Epub 2020 Oct 11. PMID: 33040610; PMCID: PMC7944432.

- Masakado Y, Abo M, Kondo K, Saeki S, Saitoh E, Dekundy A, Hanschmann A, Kaji R; J-PURE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of incobotulinumtoxinA in post-stroke upper-limb spasticity in Japanese subjects: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (J-PURE). J Neurol. 2020 Jul;267(7):2029-2041. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09777-5. Epub 2020 Mar 26. PMID: 32219557; PMCID: PMC7320940.

- Masakado Y, Kagaya H, Kondo K, Otaka Y, Dekundy A, Hanschmann A, Geister TL, Kaji R. Efficacy and Safety of IncobotulinumtoxinA in the Treatment of Lower Limb Spasticity in Japanese Subjects. Front Neurol. 2022 Mar 17;13:832937. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.832937. PMID: 35370917; PMCID: PMC8970182.

- McCrory P, Turner-Stokes L, Baguley IJ, et al. Botulinum toxin A for treatment of upper limb spasticity following stroke: a multi-centre randomized placebo-controlled study of the effects on quality of life and other person-centred outcomes. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2009;41(7):536-44.

- Prazeres A, Lira M, Aguiar P, Monteiro L, Vilasbôas Í, Melo A. Efficacy of physical therapy associated with botulinum toxin type A on functional performance in post-stroke spasticity: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Neurol Int. 2018 Jul 4;10(2):7385. doi: 10.4081/ni.2018.7385. PMID: 30069286; PMCID: PMC6050449.

- Rosales RL, Kong KH, Goh KJ, et al. Botulinum toxin injection for hypertonicity of the upper extremity within 12 weeks after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabilitation & Neural Repair. 2012;26(7):812-21.

- Wallace AC, Talelli P, Crook L, Austin D, Farrell R, Hoad D, O'Keeffe AG, Marsden JF, Fitzpatrick R, Greenwood R, Rothwell JC, Werring DJ. Exploratory Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial of Botulinum Therapy on Grasp Release After Stroke (PrOMBiS). Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2020 Jan;34(1):51-60. doi: 10.1177/1545968319887682. Epub 2019 Nov 20. PMID: 31747825.

- Ward AB, Wissel J, Borg J, Ertzgaard P, Herrmann C, Kulkarni J, Lindgren K, Reuter I, Sakel M, Säterö P, Sharma S, Wein T, Wright N, Fulford-Smith A; BEST Study Group. Functional goal achievement in post-stroke spasticity patients: the BOTOX® Economic Spasticity Trial (BEST). J Rehabil Med. 2014 Jun;46(6):504-13. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1817. PubMed PMID: 24715249.

- Wein T, Esquenazi A, Jost WH, Ward AB, Pan G, Dimitrova R. OnabotulinumtoxinA for the Treatment of Poststroke Distal Lower Limb Spasticity: A Randomized Trial. PM R. 2018 Jul;10(7):693-703. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.12.006. Epub 2018 Jan 9. PMID: 29330071.

- Wise RA, Brown CD. Minimal clinically important differences in the six-minute walk test and the incremental shuttle walking test. COPD. 2005 Mar;2(1):125-9. doi: 10.1081/copd-200050527. PMID: 17136972.

Evidence tabellen

Risk of bias table

|

Study reference

|

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

|

Was the allocation adequately concealed? |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented? |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

|

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting? |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias? |

Overall risk of bias |

|

Lindsay, 2021 |

Deflnitely yes;

computer generated with random permuted blocks in pseudo-random sequence. |

Definitely yes;

Patients assigned by independent research pharmacist according to randomizaton |

Probably yes;

patient, injecting clinician and assessor were all blinded to the treatment being delivered (blinding of data collectors and analysts not reported) |

definitely no;

Loss to follow-up was 10-20%, being higher in botox group. In case of missing values the last value was carried forward. Did not assess intention to treat population. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns |

|

Wallace, 2020 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Central randomization with computer generated random numbers |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Opaque, sealed envelopes were used and opened by an independent researcher. |

Definitely yes,

Patients were blinded. All staff involved in assessment, treatment, or with any clinical contact with the patient were blinded.

|

definitely yes;

Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. Intention to treat population was analysed, imputation was used in case of missing values |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

low |

|

Masakado, 2020 |

Not reported |

Not reported |

Not reported.

The study is reported to be double blind, but no further information is given |

Probably yes;

flow diagram shows no patients lost to follow-up, but no futther information reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely no;

The study was funded by the pharmaceutical manufacturer of the intervention, Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH, and three authors are employee or consultant for the company. |

High |

|

Rosales, 2012 |

definitely yes

Eligible patients were allocated to receive BoNT-A or placebo in a 1:1 ratio according to a predetermined randomization schedule (block size of 4) generated by the sponsor-assigned biostatistician. |

Definitely yes

The sponsor-assigned randomization manager provided treatment allocation codes to the drug supplier and drug safety officer, with the master listing kept confidential and secured by the sponsor representative. |

Probably yes,

Blinding of all involved until data collection complete. Unclear whether analysts were blinded as well. |

definitely yes,

Intention to treat analysis with all randomized patients. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely no;

The study was funded by Ipsen, three authors were employees at Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH. |

Some concerns |

|

McCrory, 2009 |

Definitely yes,

A computer-generated master list of randomized treatment allocation codes was prepared centrally by an independent organization with a 1:1 proportion of patients assigned to each group. |

Probably yes,

sequential allocation of treatment packs from the hospital pharmacy with pre-assigned randomization numbers. |

Definitely yes,

The patients, investigators and treating teams were all blinded to group assignment. The master randomization list was supplied only after the database had been locked and the statistical plan approved. |

definitely yes,

Intention to treat analysis with all randomized patients. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes,

this study was funded by Ipsen, who had no influence on the interpretation of data and the final conclusions drawn. |

low |

|

Wein, 2018 |

Definitely yes,

Patients were randomly assigned (1:1, block size 4). An automated interactive voice- or Web-response system managed randomization and treatment assignment, based on a randomization scheme prepared by Allergan Biostatistics, |

Definitely yes,

Sites dispensed medication according to the instructions received from the interactive voice- or Web-response system. Treatments were provided in identical packaging. |

Probably yes,

The injector and patient were blinded to treatment allocation. Not reported for others involved in study |

Probably yes,

Efficacy was evaluated using the intent-to-treat population. Handling of missing data not reported. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably no,

This study was funded by Allergan plc. Two of the authors were Allergan employees. |

Some concerns |

|

Kerzoncuf, 2020 |

Probably yes,

A blocked randomization sequence was used in this trial. |

Not reported |

Definitely yes,

None of the participants, investigators, treating clinicians, nurses, or PRM specialists were informed about any of the patients’ treatment status. |

Definitely no,

No intention-to-treat analysis for efficacy |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes |

Some concerns |

|

Masakado, 2022 |

Definitely yes, Subjects were randomized 1:1 to incobotulinumtoxinA or placebo using a computerized randomization program that assigned an individual number to each subject. |

Not reported |

Probably yes,

Placebo vials had the same appearance as incobotulinumtoxinA vials to allow double blinding of the subject and investigator. Blinding of others involved not reported |

definitely yes,

Efficacy was evaluated using the intent-to-treat population.

Proper imputation techniques were used. |

Not reported,

Study protocol not published? |

Probably no

The study was funded by Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH. Conflicts of interests were not reported, but three authors were employees at Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH. |

Some concerns

|

|

Gracies, 2017 |

Probably yes,

Participants were randomized (1:1:1) using a block design to receive abobotulinumtoxin-A 1,000 U, 1,500 U, or placebo and stratified by toxin baseline status (naive and non-naive; e-Methods). |

Not reported |

Not reported,

Only mentioned that is was a double-blind study |

probably no,

Efficacy was evaluated using the intent-to-treat population, but this was defined by patients who had no missings for the primary outcome

|

Not reported,

Study protocol not published? |

Probably no,

This study was sponsored by Ipsen. Four of the authors were Ipsen employees. |

high |

|

Kaji, 2010 |

Probably yes

The person responsible for randomization prepared a randomization code table |

Probably yes,

Randomization code table was concealed from all investigators and all study personnel |

Not reported |

definitely yes,

Intention to treat analysis with all randomized patients. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

definitely no,

This study was sponsored and written by GlaxoSmithKline |

Some concerns |

|

Prazeres, 2018 |

Definitely yes,

Eligible subjects were allocated into two intervention groups through a randomized block system (blocks of ten) |

Probably yes,

Subjects were allocated with codified numbers drawn from an opaque envelope. |

Probably yes,

The files that identified the group allocation were archived and investigators and patients remained blinded during all study procedures. Blinding of others involved not reported |

definitely no,

No intention to treat analysis or imputation methods |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes,

Nothing noted |

low |

|

Ward, 2014 |

Unclear,

Patients were randomized to onabotulinumtoxinA) + standard of care or placebo + SC (in a 1:1 ratio) and the treatment arms were stratified according to location of spasticity (UL or LL).

|

Not reported |

Not reported |

probably yes,

Intention to treat analysis with all randomized patients. Furthermore, 12% and 20% of the participants were lost to follow up. However, data was imputed (imputed a clean data were not reported separately). |

Definitely no,

not all pre specified outcomes are reported in the publication; |

Probably no

Allergan employees were involved in: (i) the design and conduct of the study; and (ii) the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the study data. The authors had sole control over the preparation, review, and approval of this manuscript. |

high |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Bakheit AM, Pittock S, Moore AP, Wurker M, Otto S, Erbguth F, Coxon L. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in upper limb spasticity in patients with stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2001 Nov;8(6):559-65. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00277.x. PMID: 11784339. |

Study limitations, limited reporting of methodology and results |

|

Bhakta BB, Cozens JA, Chamberlain MA, Bamford JM. Impact of botulinum toxin type A on disability and carer burden due to arm spasticity after stroke: a randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000 Aug;69(2):217-21. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.217. Erratum in: J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001 Jun;70(6):821. PMID: 10896696; PMCID: PMC1737061. |

Study limitations, limited reporting of results |

|

Pittock SJ, Moore AP, Hardiman O, Ehler E, Kovac M, Bojakowski J, Al Khawaja I, Brozman M, Kanovský P, Skorometz A, Slawek J, Reichel G, Stenner A, Timerbaeva S, Stelmasiak Z, Zifko UA, Bhakta B, Coxon E. A double-blind randomised placebo-controlled evaluation of three doses of botulinum toxin type A (Dysport) in the treatment of spastic equinovarus deformity after stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;15(4):289-300. doi: 10.1159/000069495. PMID: 12686794. |

Study limitations, limited reporting of results |

|

Barnes M, Schnitzler A, Medeiros L, Aguilar M, Lehnert-Batar A, Minnasch P. Efficacy and safety of NT 201 for upper limb spasticity of various etiologies--a randomized parallel-group study. Acta Neurol Scand. 2010 Oct;122(4):295-302. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2010.01354.x. Epub 2010 Apr 26. PMID: 20456248. |

Wrong outcome measures |

|

Hokazono A, Etoh S, Jonoshita Y, Kawahira K, Shimodozono M. Combination therapy with repetitive facilitative exercise program and botulinum toxin type A to improve motor function for the upper-limb spastic paresis in chronic stroke: A randomized controlled trial. J Hand Ther. 2022 Oct-Dec;35(4):507-515. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2021.01.005. Epub 2021 Jan 26. PMID: 33820711. |

Study limitations: limited reporting of results. |

|

Diniz de Lima F, Faber I, Servelhere KR, Bittar MFR, Martinez ARM, Piovesana LG, Martins MP, Martins CR Jr, Benaglia T, de Sá Carvalho B, Nucci A, França MC Jr. Randomized Trial of Botulinum Toxin Type A in Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia - The SPASTOX Trial. Mov Disord. 2021 Jul;36(7):1654-1663. doi: 10.1002/mds.28523. Epub 2021 Feb 17. PMID: 33595142. |

Study limitations, wrong design (cross-over) |

|

Yu HX, Liu SH, Wang ZX, Liu CB, Dai P, Zang DW. Efficacy on gait and posture control after botulinum toxin A injection for lower-limb spasticity treatment after stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Front Neurosci. 2023 Jan 16;16:1107688. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.1107688. PMID: 36726851; PMCID: PMC9884969. |

Study limitations, limited reporting of results |

|

Dong Y, Wu T, Hu X, Wang T. Efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A for upper limb spasticity after stroke or traumatic brain injury: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017 Apr;53(2):256-267. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.16.04329-X. Epub 2016 Nov 11. PMID: 27834471. |

bevat geen nieuwe studies, alleen Elovic (2016), ook in deze search |

|

Pennati GV, Da Re C, Messineo I, Bonaiuti D. How could robotic training and botolinum toxin be combined in chronic post stroke upper limb spasticity? A pilot study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015 Aug;51(4):381-7. Epub 2014 Oct 31. PMID: 25358636. |

pilot study, sample size too small, zat ook al in oude search |

|

Abramovich SG, Drobyshev VA, Pyatova AE, Yumashev AV, Koneva ES. Comprehensive Use of Dynamic Electrical Neurostimulation and Botulinum Toxin Therapy in Patients with Post-Stroke Spasticity. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020 Nov;29(11):105189. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105189. Epub 2020 Aug 6. PMID: 33066944. |

Veel beperkingen in studieopzet |

|

Andraweera ND, Andraweera PH, Lassi ZS, Kochiyil V. Effectiveness of Botulinum Toxin A Injection in Managing Mobility-Related Outcomes in Adult Patients With Cerebral Palsy: Systematic Review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2021 Sep 1;100(9):851-857. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001653. PMID: 33252471. |

bevat alleen studies van <2015 |

|

Andringa A, van de Port I, van Wegen E, Ket J, Meskers C, Kwakkel G. Effectiveness of Botulinum Toxin Treatment for Upper Limb Spasticity Poststroke Over Different ICF Domains: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019 Sep;100(9):1703-1725. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2019.01.016. Epub 2019 Feb 21. PMID: 30796921. |

2 studies voldoen aan pico en timing, zitten ook in deze search. Verder is de data van meta-analyse niet te onderscheiden per studie, dus studies los meenemen |

|

Baker JA, Pereira G. The efficacy of Botulinum Toxin A on improving ease of care in the upper and lower limbs: a systematic review and meta-analysis using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach. Clin Rehabil. 2015 Aug;29(8):731-40. doi: 10.1177/0269215514555036. Epub 2014 Oct 28. PMID: 25352614. |

bevat alleen studies van < july 2014 |

|

Baker JA, Pereira G. The efficacy of Botulinum Toxin A for limb spasticity on improving activity restriction and quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis using the GRADE approach. Clin Rehabil. 2016 Jun;30(6):549-58. doi: 10.1177/0269215515593609. Epub 2015 Jul 6. PMID: 26150020. |

bevat alleen studies van <2015 |

|

Baricich A, Battaglia M, Cuneo D, Cosenza L, Millevolte M, Cosma M, Filippetti M, Dalise S, Azzollini V, Chisari C, Spina S, Cinone N, Scotti L, Invernizzi M, Paolucci S, Picelli A, Santamato A. Clinical efficacy of botulinum toxin type A in patients with traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, or multiple sclerosis: An observational longitudinal study. Front Neurol. 2023 Apr 6;14:1133390. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1133390. PMID: 37090974; PMCID: PMC10117778. |

verkeerde studie design |

|

Cofré Lizama LE, Khan F, Galea MP. Beyond speed: Gait changes after botulinum toxin injections in chronic stroke survivors (a systematic review). Gait Posture. 2019 May;70:389-396. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2019.03.035. Epub 2019 Apr 4. PMID: 30974394. |

bevat ook observationele studies. 5 vd 22 studies > half 2015 |

|

Dashtipour K, Chen JJ, Walker HW, Lee MY. Systematic literature review of abobotulinumtoxinA in clinical trials for adult upper limb spasticity. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2015 Mar;94(3):229-38. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000208. PMID: 25299523; PMCID: PMC4340600. |

bevat alleen studies <2013 |

|

Dashtipour K, Chen JJ, Walker HW, Lee MY. Systematic Literature Review of AbobotulinumtoxinA in Clinical Trials for Lower Limb Spasticity. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Jan;95(2):e2468. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002468. PMID: 26765447; PMCID: PMC4718273. |

bevat alleen studies <2013 |

|

Doan TN, Kuo MY, Chou LW. Efficacy and Optimal Dose of Botulinum Toxin A in Post-Stroke Lower Extremity Spasticity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Toxins (Basel). 2021 Jun 18;13(6):428. doi: 10.3390/toxins13060428. PMID: 34207357; PMCID: PMC8234518. |

bevat een aantal studies van oude en nieuwe search, maar niet alle oude en ook geexcludeerde studies die niet voldoen aan PICO |

|

Esquenazi A, Wein TH, Ward AB, Geis C, Liu C, Dimitrova R. Optimal Muscle Selection for OnabotulinumtoxinA Injections in Poststroke Lower-Limb Spasticity: A Randomized Trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019 May;98(5):360-368. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001101. PMID: 31003229. |

Wein 2018 en Patel 2020, |

|

Esquenazi A, Brashear A, Deltombe T, Rudzinska-Bar M, Krawczyk M, Skoromets A, O'Dell MW, Grandoulier AS, Vilain C, Picaut P, Gracies JM. The Effect of Repeated abobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport®) Injections on Walking Velocity in Persons with Spastic Hemiparesis Caused by Stroke or Traumatic Brain Injury. PM R. 2021 May;13(5):488-495. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12459. Epub 2020 Sep 11. PMID: 32741133; PMCID: PMC8246752. |

zelfde data/trial als Gracies 2017,maar alleen prospectieve analyses, geen vergelijkende groep/controle meer (alleen secondary open label results van studie) |

|

Gupta AD, Chu WH, Howell S, Chakraborty S, Koblar S, Visvanathan R, Cameron I, Wilson D. A systematic review: efficacy of botulinum toxin in walking and quality of life in post-stroke lower limb spasticity. Syst Rev. 2018 Jan 5;7(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0670-9. PMID: 29304876; PMCID: PMC5755326. |

verkeerder comparison (alleen placebo) en geen studies > half 2015 |

|

Hara T, Momosaki R, Niimi M, Yamada N, Hara H, Abo M. Botulinum Toxin Therapy Combined with Rehabilitation for Stroke: A Systematic Review of Effect on Motor Function. Toxins (Basel). 2019 Dec 5;11(12):707. doi: 10.3390/toxins11120707. PMID: 31817426; PMCID: PMC6950173. |

maar 3 studies voldoen aan PICO, allen in huidige search. Redenen voor exclusie niet beschreven |

|

Hwang W, Kang SM, Lee SY, Seo HG, Park YG, Kwon BS, Lee KJ, Kim DY, Kim HS, Lee SU. Efficacy and Safety of Botulinum Toxin Type A (NABOTA) for Post-stroke Upper Extremity Spasticity: A Multicenter Phase IV Trial. Ann Rehabil Med. 2022 Aug;46(4):163-171. doi: 10.5535/arm.22061. Epub 2022 Aug 31. PMID: 36070998; PMCID: PMC9452292. |

Geen vergelijkende groep, prospectieve studie |

|

Jia S, Liu Y, Shen L, Liang X, Xu X, Wei Y. Botulinum Toxin Type A for Upper Limb Spasticity in Poststroke Patients: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020 Jun;29(6):104682. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104682. Epub 2020 Apr 15. PMID: 32305277. |

alle studies <2015 |

|

Kaňovský P, Elovic EP, Hanschmann A, Pulte I, Althaus M, Hiersemenzel R, Marciniak C. Duration of Treatment Effect Using IncobotulinumtoxinA for Upper-limb Spasticity: A Post-hoc Analysis. Front Neurol. 2021 Jan 22;11:615706. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.615706. PMID: 33551974; PMCID: PMC7862578. |

verkeerde studie design |

|

Lam K, Lau KK, So KK, Tam CK, Wu YM, Cheung G, Liang KS, Yeung KM, Lam KY, Yui S, Leung C. Can botulinum toxin decrease carer burden in long term care residents with upper limb spasticity? A randomized controlled study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012 Jun;13(5):477-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.03.005. Epub 2012 Apr 20. PMID: 22521630. |

wrong year of publication (<2012) |

|

Lam K, Lau KK, So KK, Tam CK, Wu YM, Cheung G, Liang KS, Yeung KM, Lam KY, Yui S, Leung C. Use of botulinum toxin to improve upper limb spasticity and decrease subsequent carer burden in long-term care residents: a randomised controlled study. Hong Kong Med J. 2016 Feb;22 Suppl 2:S43-5. PMID: 26908344. |

zelfde studie als lam 2012 |

|

Lannin NA, Ada L, Levy T, English C, Ratcliffe J, Sindhusake D, Crotty M. Intensive therapy after botulinum toxin in adults with spasticity after stroke versus botulinum toxin alone or therapy alone: a pilot, feasibility randomized trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018 May 22;4:82. doi: 10.1186/s40814-018-0276-6. PMID: 29796293; PMCID: PMC5963180. |

pilot study, sample size too small (<10 per arm) |

|

Leung J, King C, Fereday S. Effectiveness of a programme comprising serial casting, botulinum toxin, splinting and motor training for contracture management: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2019 Jun;33(6):1035-1044. doi: 10.1177/0269215519831337. Epub 2019 Feb 27. PMID: 30813776. |

te kleine steekproef |

|

Marciniak C, Munin MC, Brashear A, Rubin BS, Patel AT, Slawek J, Hanschmann A, Hiersemenzel R, Elovic EP. IncobotulinumtoxinA Efficacy and Safety in Adults with Upper-Limb Spasticity Following Stroke: Results from the Open-Label Extension Period of a Phase 3 Study. Adv Ther. 2019 Jan;36(1):187-199. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0833-7. Epub 2018 Nov 27. PMID: 30484117; PMCID: PMC6318229. |

verkeerde studie design, prospective extension period |

|

Marciniak C, Munin MC, Brashear A, Rubin BS, Patel AT, Slawek J, Hanschmann A, Hiersemenzel R, Elovic EP. IncobotulinumtoxinA Treatment in Upper-Limb Poststroke Spasticity in the Open-Label Extension Period of PURE: Efficacy in Passive Function, Caregiver Burden, and Quality of Life. PM R. 2020 May;12(5):491-499. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12265. Epub 2020 Jan 22. Erratum in: PM R. 2020 Jul;12(7):736. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12439. PMID: 31647185. |

verkeerde studie design, prospective extension period |

|

Nasb M, Shah SZA, Chen H, Youssef AS, Li Z, Dayoub L, Noufal A, Allam AES, Hassanien M, El Oumri AA, Chang KV, Wu WT, Rekatsina M, Galluccio F, AlKhrabsheh A, Salti A, Varrassi G. Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy Combined With Botulinum Toxin for Post-stroke Spasticity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus. 2021 Sep 1;13(9):e17645. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17645. PMID: 34646693; PMCID: PMC8486367. |

komt maar 1 RCT naar voren >2015, studie van zelfde auteur en ook in deze search |

|

Patel AT, Ward AB, Geis C, Jost WH, Liu C, Dimitrova R. Impact of early intervention with onabotulinumtoxinA treatment in adult patients with post-stroke lower limb spasticity: results from the double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 REFLEX study. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2020 Dec;127(12):1619-1629. doi: 10.1007/s00702-020-02251-6. Epub 2020 Oct 27. PMID: 33106968; PMCID: PMC7666298. |

zelfde studie als esquenazi 2019 en Wein 2018, , benaderen als 1 studie |

|

Rosales RL, Efendy F, Teleg ES, Delos Santos MM, Rosales MC, Ostrea M, Tanglao MJ, Ng AR. Botulinum toxin as early intervention for spasticity after stroke or non-progressive brain lesion: A meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2016 Dec 15;371:6-14. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.10.005. Epub 2016 Oct 11. PMID: 27871449. |

bevat alleen studies van voor september 2015 |

|

Sun LC, Chen R, Fu C, Chen Y, Wu Q, Chen R, Lin X, Luo S. Efficacy and Safety of Botulinum Toxin Type A for Limb Spasticity after Stroke: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Biomed Res Int. 2019 Apr 7;2019:8329306. doi: 10.1155/2019/8329306. PMID: 31080830; PMCID: PMC6475544. |

bevat 5 studies >2015, welke allemaal in deze search. + geen bias assessment |

|

Turcu-Stiolica A, Subtirelu MS, Bumbea AM. Can Incobotulinumtoxin-A Treatment Improve Quality of Life Better Than Conventional Therapy in Spastic Muscle Post-Stroke Patients? Results from a Pilot Study from a Single Center. Brain Sci. 2021 Jul 15;11(7):934. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11070934. PMID: 34356168; PMCID: PMC8303388. |

pilot study & wrong outcome (QoL) |

|

Varvarousis DN, Martzivanou C, Dimopoulos D, Dimakopoulos G, Vasileiadis GI, Ploumis A. The effectiveness of botulinum toxin on spasticity and gait of hemiplegic patients after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Toxicon. 2021 Nov;203:74-84. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2021.09.020. Epub 2021 Oct 7. PMID: 34626599. |

bevat ook observationele studies. 5 studies van na 2015, zitten ook in deze search |

|

Wu T, Li JH, Song HX, Dong Y. Effectiveness of Botulinum Toxin for Lower Limbs Spasticity after Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2016 Jun;23(3):217-23. doi: 10.1080/10749357.2016.1139294. Epub 2016 Feb 8. PMID: 27077980. |

bevat alleen studies van < week 23, 2015 |

|

Jia S, Liu Y, Shen L, Liang X, Xu X, Wei Y. Botulinum Toxin Type A for Upper Limb Spasticity in Poststroke Patients: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020 Jun;29(6):104682. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104682. Epub 2020 Apr 15. PMID: 32305277. |

Bevat alleen studies van <2012 |

|

Yang Y, Liang Q, Wan X, Wang L, Chen S, Wu Q, Zhang X, Yu S, Shang H, Yao C. Safety and efficacy of botulinum toxin type A made in China for treatment of post-stroke upper limb spasticity: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Chinese Journal of Neurology. 2018.51. 355-363. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1006-7876.2018.05.006. |

full tekst niet beschikbaar |

|

Rosales RL, Balcaitiene J, Berard H, Maisonobe P, Goh KJ, Kumthornthip W, Mazlan M, Latif LA, Delos Santos MMD, Chotiyarnwong C, Tanvijit P, Nuez O, Kong KH. Early AbobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport®) in Post-Stroke Adult Upper Limb Spasticity: ONTIME Pilot Study. Toxins (Basel). 2018 Jun 21;10(7):253. doi: 10.3390/toxins10070253. PMID: 29933562; PMCID: PMC6070912. |

Did not report outcomes of interest |

|

Elovic EP, Munin MC, Kaňovský P, Hanschmann A, Hiersemenzel R, Marciniak C. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of incobotulinumtoxina for upper-limb post-stroke spasticity. Muscle Nerve. 2016 Mar;53(3):415-21. doi: 10.1002/mus.24776. Epub 2015 Dec 15. Erratum in: Muscle Nerve. 2016 Jun;54(1):170. doi: 10.1002/mus.25182. PMID: 26201835; PMCID: PMC5064747. |

Did not report outcomes of interest |

|

Kaji R, Osako Y, Suyama K, et al. Botulinum toxin type A in post-stroke upper limb spasticity. Current Medical Research & Opinion. 2010a;26(8):1983-92. |

Did not report outcomes of interest |

|

Kanovsky P, Slawek J, Denes Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of botulinum neurotoxin NT 201 in poststroke upper limb spasticity. Clinical Neuropharmacology. 2009;32(5):259-65. |

Did not report outcomes of interest |

|

Brashear A, Gordon MF, Elovic E, et al. Intramuscular injection of botulinum toxin for the treatment of wrist and finger spasticity after a stroke. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(6):395-400. |

Did not report outcomes of interest |

|

Gracies JM, Brashear A, Jech R, et al. Safety and efficacy of abobotulinumtoxinA for hemiparesis in adults with upper limb spasticity after stroke or traumatic brain injury: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurology. 2015;14(10):992-1001. |

Did not report outcomes of interest |

|

Shaw L, Rodgers H, Price C, et al. BoTULS: a multicentre randomised controlled trial to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treating upper limb spasticity due to stroke with botulinum toxin type A. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England). 2010;14(26):1-113, iii-iv. |

Did not report outcomes of interest |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 06-01-2026

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 06-01-2026

De Nederlandse Vereniging van Revalidatieartsen geeft bestuurlijke goedkeuring onder voorwaarde van autorisatie door de ALV van 17 april 2026.

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2023 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met Cerebrale en/of spinale spasticiteit.

Werkgroep

- prof. dr. A.C.H. Geurts (voorzitter), hoogleraar neurorevalidatie, Radboud UMC en Sint Maartenskliniek, namens de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Revalidatieartsen

- drs. A.M.V. Dommisse, revalidatiearts, Isala Klinieken Zwolle, namens de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Revalidatieartsen

- drs. P.J. van Dongen, patiëntvertegenwoordiger bij Hersenletsel.nl

- Dr. M. van Eijk, specialist ouderengeneeskunde, Marnix Medisch B.V., namens Verenso

- dr. J.F.M. Fleuren, revalidatiearts, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis / Tolbrug, ‘s Hertogenbosch, namens de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Revalidatieartsen

- F. van Gorp-Swart, MSc, ziekenhuisapotheker, Diakonessenhuis, Utrecht/Zeist/Doorn, namens de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Ziekenhuisapothekers

- prof. dr. G. Kwakkel, hoogleraar neurorevalidatie, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, namens het Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie

- drs. E. Kurt, neurochirurg, Radboud UMC en Canisius Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis, Nijmegen, namens de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurochirurgie

- Prof. dr. C.G.M. Meskers, hoogleraar revalidatiegeneeskunde, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, namens de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Revalidatieartsen