Conservatieve behandelopties bij achilles tendinopathie

Uitgangsvraag

Welke conservatieve behandeling is het meest effectief voor patiënten met achilles tendinopathie?

Aanbeveling

Midportion achilles tendinopathie en Insertie achilles tendinopathie

Adviseer in samenspraak met de patiënt een actieve behandeling. De behandeling dient verzorgd te worden door een zorgverlener die voldoende gekwalificeerd is (medisch of paramedisch zorgverlener).

Bespreek de initiële actieve behandelopties samen met de patiënt. Start bij de behandeling van patiënten met midportion achilles tendinopathie en insertie achilles tendinopathie met:

- Patiënt educatie:

- uitleg over de aandoening;

- uitleg over de prognose;

- pijn educatie.

- Belasting adviezen:

- tijdelijk staken van provocerende (sport)belasting;

- tijdelijk vervangen van provocerende (sport)belasting door niet-provocerende (sport)belasting;

- geleidelijke opbouw van (sport)belasting;

- gebruik een pijnschaal om de mate van klachten gerelateerd aan (sport)belasting te monitoren en aan te passen.

- Opbouwende krachtoefeningen van de kuitspieren gedurende minimaal 12 weken. De vorm van oefentherapie dient afgestemd te worden met de individuele patiënt. Overweeg hierin de motivatie, tijdsbelasting, pijnmonitoring en beschikbaarheid van faciliteiten een rol te laten spelen. Overweeg bij insertie achilles tendinopathie om de oefeningen initieel uit te voeren vanaf een vlakke ondergrond.

Indien patiënt educatie is toegepast en na 3 maanden structurele oefentherapie en opvolgen van belastingadviezen geen verbetering is opgetreden, overleg dan met de patiënt welke aanvullende behandelopties in overweging genomen kunnen worden. Bespreek de onzekerheid van het aanvullende effect en de voor- en nadelen van iedere aanvullende behandeling. In samenspraak met de patiënt kan dan tot de beste behandeloptie worden besloten.

De volgende aanvullende behandelopties kunnen bij onvoldoende effectiviteit van patiënt educatie, belasting adviezen en adequate oefentherapie worden overwogen in combinatie met oefentherapie:

- Extracorporale shockwave therapie (ESWT).

- Andere passieve modaliteiten (het gebruik van een nachtspalk, inlays, gebruik van collageen supplementen, toepassen van ultrageluid en frictie massages, laser therapie en licht therapie).

- Injectie behandelingen (injecties met polidocanol, lidocaïne, autoloog bloed, plaatjes-rijk plasma, stromale vasculaire fractie, hyaluronzuur, prolotherapie of een hoog-volume injectie) en acupunctuur (of intratendineuze needling).

Wees terughoudend met het toepassen van de volgende aanvullende behandelopties:

- Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs).

- Corticosteroïd injecties.

Overwegingen

In deze uitgangsvraag is de effectiviteit van conservatieve behandelopties bij patiënten met achilles tendinopathie beoordeeld.

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Uit de resultaten blijkt dat er veel verschillende behandelopties voorhanden zijn voor achilles tendinopathie, met name voor het subtype midportion achilles tendinopathie. De bewijskracht voor deze behandelingen is echter in bijna alle gevallen laag tot zeer laag en de geschatte behandeleffecten overlappen elkaar grotendeels in vrijwel alle behandelcategorieën. Daar waar er geen overlap is, zijn de resultaten gebaseerd op twee kleine RCT’s (voor zowel acupunctuur als oefentherapie+shockwave therapie) met een hoog risico op bias (Rompe, 2009; Zhang, 2013). Dit geeft weer dat er een sterke onzekerheid is in de schattingen van de behandeleffecten en dat er dus ook geen sterke aanbevelingen mogelijk zijn. Daarnaast is het aantal studies voor insertie achilles tendinopathie zeer beperkt, waardoor ook voor dit subtype sterke aanbevelingen niet mogelijk zijn. De werkgroep is van mening dat voor veel behandelcategorieën de adviezen geëxtrapoleerd kunnen worden naar patiënten met insertie tendinopathie. In een klein aantal gevallen zal de aanbeveling echter zijn om deze entiteit anders te behandelen. Daar waar dit het geval is, zal dit duidelijk worden geëxpliciteerd.

De werkgroep tracht in deze overwegingen uiteen te zetten hoe het uiteindelijk tot de aanbevelingen is gekomen. De effectiviteit van de behandeling, de veiligheid van de behandeling, de tijd die de patiënt in de behandeling moet investeren, de kosten van de behandeling (voor de patiënt en/of de maatschappij indien het binnen de vergoede zorg valt) en de beschikbaarheid van de behandeling op nationaal niveau, evenals de klinische expertise van de behandelaar en voorkeuren van patiënten zijn in deze overwegingen meegenomen. De werkgroep is van mening dat bij het bespreken van de behandelopties sterk moet worden overwogen om het ‘shared decision-making’ model toe te passen, om zo de kans op een succesvolle uitkomst van de behandeling te verhogen (Bowen, 2020; Dijkstra, 2017; Spinnewijn, 2020).

Een actieve behandeling lijkt superieur aan een overwegend afwachtend beleid bij patiënten met midportion achilles tendinopathie. Omdat er gemiddeld een klinisch relevant verschil is tussen alle actieve behandelvormen en een overwegend afwachtend beleid, adviseert de werkgroep om een vorm van actieve behandeling toe te passen bij patiënten met achilles tendinopathie. Hoewel dit niet specifiek is onderzocht voor insertie achilles tendinopathie, acht de werkgroep het aannemelijk dat deze resultaten geëxtrapoleerd kunnen worden naar dit subtype tendinopathie. Andersom betekent dit dus dat de werkgroep adviseert om geen overwegend afwachtend beleid te hanteren. Dit advies is gebaseerd op onderzoeken bij patiënten met chronische achilles tendinopathie (langer dan 8 tot 12 weken bestaande klachten). Het is discutabel of dit kan worden geëxtrapoleerd naar de groep patiënten met kort bestaande (reactieve) achilles tendinopathie. Bij kort bestaande achilles tendinopathie kan wel eerst een korte periode van relatieve rust worden geïnitieerd als overbelasting een evidente risicofactor is in de anamnese van de individuele patiënt (Cook, 2009). De werkgroep adviseert echter ook voor patiënten met kort bestaande (reactieve) achilles tendinopathie een adequate follow-up af te spreken en actieve behandeling toe te passen om de belastbaarheid van de pees te vergroten en een geleidelijke terugkeer naar (sport)belasting te faciliteren. Onderstaande principes kunnen ook daar worden toegepast.

Patiënt educatie en het geven van belasting adviezen zijn niet eerder in RCT’s onderzocht op effectiviteit voor patiënten met achilles tendinopathie. De werkgroep geeft aan dat in de praktijk behandelingen normaliter worden gecombineerd met patiënt educatie en belasting adviezen. De werkgroep is van mening dat patiënt educatie bijdraagt aan een adequaat verwachtingsmanagement en plannen van meer realistische doelstellingen. De belasting adviezen hebben als belangrijk doel om de patiënt zelfbewuster en zelfredzamer te maken. Op basis van klinische expertise adviseert de werkgroep om patiënt educatie en belasting adviezen te overwegen als basis van de behandeling van achilles tendinopathie.

De term patiënt educatie wordt gebruikt voor het uitwisselen van kennis tussen de zorgverlener en patiënt op een interactieve manier. Effecten van patiënt educatie worden vaak onderbelicht. Recent onderzoek bij patiënten met gluteus medius tendinopathie laat zien dat patiënt eductie in combinatie met oefentherapie effectiever is dan een overwegend afwachtend beleid of een injectie met corticosteroïden (Mellor, 2018). Patiënt educatie voor patiënten met achilles tendinopathie heeft volgens de werkgroep 3 elementen: uitleg over de aandoening, uitleg over de prognose en pijn educatie. Concreet houdt dit in dat er uitleg wordt gegeven over het degeneratieve aspect van de aandoening met vaak langdurige klachten. Deze klachten kunnen een terugkerend karakter hebben, vooral indien de specifieke provocerende (sport)belasting wordt gecontinueerd. Pijn educatie houdt in dat zorgverleners hun kennis over pijn delen met de patiënt. Dit omvat uitleg van de neurofysiologie van acute en chronische pijn (inclusief centrale sensitisatie). In de vroege fase van een reactieve tendinopathie kan er nog sprake zijn van een acute (fysiologische) pijn, terwijl in de chronische fase de pijn pathologisch (dysfunctioneel) kan zijn (Rio, 2014). Naast lichamelijke factoren komt er steeds meer aandacht voor de invloed van psychosociale aspecten op langdurige pijnklachten. Uit recent onderzoek blijken deze psychosociale factoren ook een belangrijke rol te spelen bij patiënten met achilles tendinopathie (Mc Auliffe, 2017). Relatieve rust kan kortdurend waarschijnlijk de pees beschermen in de vroege (reactieve) fase van de tendinoapthie. Echter, factoren zoals angst voor het ontstaan van meer schade of een volledige ruptuur, bewegingsangst en catastroferen van de klachten, kunnen vooral bij langer bestaande klachten het herstel negatief beïnvloeden. Bij de aanwezigheid van dit soort factoren kan pijn educatie effectief zijn in het verbeteren van ervaren gezondheid en verminderen van de zorgconsumptie. Dit is voornamelijk bij patiënten met lage rugpijn onderzocht, maar nog niet bij patiënten met achilles tendinopathie (Louw, 2014).

Belasting advies bestaat uit het tijdelijk vervangen van provocerende (sport)belasting door niet-provocerende (sport)belasting, geleidelijke opbouw van (sport)belasting en het gebruik van een pijnschaal om de mate van pijnklachten gerelateerd aan (sport)belasting te monitoren en aan te passen. Hoewel ook deze strategie geaccepteerd is voor patiënten met tendinopathie, is het effect hiervan niet in een gerandomiseerde studie onderzocht (Davenport, 2005). Deze belasting adviezen hangen nauw samen met de patiënt educatie, waarbij het van belang is om beweging voldoende te stimuleren maar risicovol gedrag met een ‘flare-up’ van pijn juist te vermijden. Uiteindelijk zouden patiënten met deze strategie in staat moeten zijn om de belasting geleidelijk te verhogen binnen de acceptabele pijngrenzen.

De werkgroep adviseert bij de behandeling van patiënten met achilles tendinopathie te starten met een vorm van krachtoefeningen van de kuitspieren en de achillespees. Deze behandeling wordt geadviseerd voor een duur van minimaal 12 weken; op dit tijdstip mag na adequate oefentherapie verbetering in ervaren klachten worden verwacht en dit vormt een goede basis om de oefeningen verder op te bouwen. Dit advies wordt verstrekt aangezien de resultaten van oefentherapie veelal vergelijkbaar zijn met de resultaten van andere conservatieve behandelopties. Er zijn echter nog veel vragen over de rol van de krachtoefeningen en hoe deze gedoseerd moeten worden. Er zijn bij patiënten met achilles tendinopathie meerdere vormen van krachtoefeningen beschikbaar, waaronder excentrische oefentherapie, concentrische oefentherapie, opbouwende krachtoefeningen en ‘heavy slow resistance’ oefeningen. Er zijn geen duidelijke verschillen gevonden in de effectiviteit van deze vormen van oefentherapie. Daarnaast is er beperkte of onvoldoende kennis over de invloed van factoren zoals het optimale aantal sessies per week, het aantal herhalingen, het gebruik van externe gewichten en de mate van pijn tijdens oefeningen. Uit de resultaten van de submodule ‘Operatieve behandelopties’ komt naar voren dat er zeer laag bewijs is dat er geen invloed is van (1) de mate van therapietrouwheid gedurende het oefenprogramma, (2) de mate van toevoeging van extra gewicht waarmee de oefentherapie uitgevoerd is en (3) of de oefeningen technisch correct worden uitgevoerd op de effectiviteit van het programma. De keuze voor de vorm van oefentherapie dient daarom afgestemd te worden op het individu. Het toevoegen van gewichten kan worden overwogen, met name als de patiënt een hoge (sport)belasting van de pees eist. De werkgroep adviseert om de mate van pijn tijdens en na de oefeningen een rol te geven in de opbouw van dit programma (Stevens, 2014). Het gegeven dat de techniek van uitvoering van de oefeningen geen prominente rol speelt impliceert dat het gebruik van informatiefolders en websites met foto- en film materiaal opties zijn om de oefeningen uit te leggen aan patiënten.

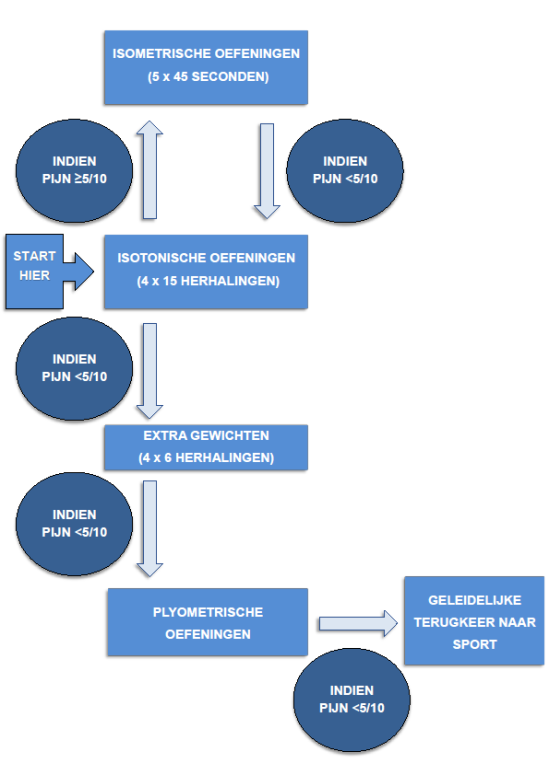

Het meeste onderzoek is verricht naar de effectiviteit van excentrische oefentherapie. Omdat deze vorm als pijnlijk kan worden ervaren door patiënten, kan hiermee rekening worden gehouden in de opbouw. De werkgroep adviseert om de patiënt een serie van 15 isotonische oefeningen van de kuitspieren te laten uitvoeren en de mate van pijn te laten evalueren tijdens en na de oefeningen. Indien het pijn niveau (score 0 tot 10) op een score van vijf punten of hoger uitkomt of als de spiervermoeidheid het niet of nauwelijks mogelijk maakt om één serie uit te voeren, dan kan de patiënt starten met isometrische oefenvormen. De ervaring van de werkgroep is dat deze isometrische oefenvormen bij sommige patiënten minder pijn uitlokken. In die groep kan deze stap nuttig zijn. Recent onderzoek laat zien dat isometrische oefeningen bij patiënten met achilles tendinopathie gemiddeld genomen geen analgetisch effect hebben (O'Neill, 2019b; Van der Vlist, 2019b). Als de patiënt geen pijnreductie ervaart bij isometrische oefeningen, dan adviseert de werkgroep over te gaan naar minder zware isotonische vormen (door bijvoorbeeld tijdelijk met 2 benen te trainen of door het aantal herhalingen per serie te verlagen). Indien de isometrische oefeningen wel pijnreducerend zijn en de pijnscore vijf punten of minder is, dan kan de patiënt starten met isotonische vormen en deze opbouwen met gewichtstraining als de condities het toelaten. In de opbouw van deze oefeningen zal de mate van pijn tijdens en na de oefeningen steeds leidend zijn in de progressie (een pijnscore van vijf of minder kan worden geaccepteerd). Afhankelijk van de sportwens kan na afronding van een isotonische fase nog een fase plyometrische oefeningen worden gedaan. Zie figuur 3 voor een schematisch overzicht van deze patiënt-gecentreerde benadering, dat als voorbeeld dient.

Het overgrote deel van de onderzoeken die de effectiviteit van oefentherapie hebben beoordeeld zijn uitgevoerd in patiënten met een midportion achilles tendinopathie. Er dient daarom meer onderzoek uitgevoerd te worden naar de effectiviteit van oefentherapie bij patiënten met een insertie achilles tendinopathie. Er is onderzoek met zeer lage bewijskracht waaruit blijkt dat oefentherapie vanaf vlakke ondergrond effectiever is dan oefentherapie waarin er wordt getraind met een diepe dorsaalflexiehoek van de enkel bij patiënten met insertie achilles tendinopathie (niet geïncludeerd in de resultaten van deze uitgangsvraag) (Fahlstrom, 2003; Jonsson, 2008). De theorie is dat er in diepe dorsaalflexiehoeken een grotere compressiekracht is van de calcaneus en bursa retrocalcaneï op de achillespees insertie (Fahlstrom, 2003). Deze verhoogde druk kan leiden tot een zogeheten compressie tendinopathie (Cook, 2012). Het wegnemen van deze compressie in de eerste fase van oefentherapie kan hypothetisch effectief zijn. Hoogwaardige wetenschappelijke literatuur hiervoor ontbreekt momenteel echter.

In de praktijk wordt bij het inrichten van de oefentherapie ook vaak aandacht geschonken aan de rol van de kinetische keten en correctie daarvan. Met de kinetische keten wordt bedoeld dat het lichaam als één geheel functioneert en de eigenschappen van één gewricht daarom waarschijnlijk niet verklarend zijn voor het optreden van een blessure. Er is beperkt onderzoek gedaan naar de risicofactoren in de kinetische keten voor het ontstaan van achilles tendinopathie. Daarnaast is er geen onderzoek voorhanden over de effectiviteit van correcties op de kinetische keten. Om die reden heeft de werkgroep dit niet in de aanbevelingen opgenomen.

Er is een zeer lage tot lage bewijskracht dat acupunctuur en oefentherapie+shockwave therapie de meest effectieve behandelopties zijn na 3 maanden. Deze resultaten zijn echter gebaseerd op twee kleine gerandomiseerde studies die beiden een hoog risico op bias hadden. Voor de acupunctuur geldt daarnaast nog dat de procedure van de behandeling in de studie matig is beschreven en daardoor moeilijk reproduceerbaar is. Het is zeer discutabel of de onderzochte behandeling de klassieke vorm van acupunctuur betreft en of er geen sprake is geweest van intratendineuze needling. Daarnaast laten de betrouwbaarheidsintervallen een grote onzekerheid zien in de schattingen van de behandeleffecten. Beide studies tonen enkel de resultaten na 3 maanden, waardoor onbekend is wat het effect van deze behandelingen is op langere termijn. De resultaten bij 12 maanden follow-up wijzen uit dat andere conservatieve behandelingen (orthesen en injectiebehandelingen) niet effectiever zijn dan oefentherapie. Deze effectiviteit van de conservatieve behandelopties uit de andere behandelcategorieën worden onderstaand besproken.

Een frequent toegepaste medicamenteuze behandeling in de klinische praktijk is anti-inflammatoire medicatie. De effectiviteit van een transcutane (gel) vorm en tablet vorm is in twee RCT’s onderzocht (Auclair, 1989; Heinemeier, 2017). Patiënten met kortdurende (< 1 maand) en chronische (> 3 maanden) klachten zijn in deze onderzoeken geïncludeerd. De effecten van deze Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) zijn daarin niet effectief gebleken op cruciale patiënt-gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten op korte termijn (1 tot 3 weken).

De effectiviteit van shockwave (radiale drukgolf) therapie is in meerdere RCT’s onderzocht (Lynen, 2017; Njawaya, 2017; Rompe, 2008; Rompe, 2009; Rompe, 2007). Op basis van de network meta-analysis kan worden geconcludeerd dat shockwave effectiever lijkt wanneer deze behandeling wordt gecombineerd met oefentherapie. Als shockwave therapie wordt overwogen, dan adviseert de werkgroep om dit toe te passen als aanvullende behandeling naast de krachtoefeningen voor de kuitspieren. Alle geïncludeerde RCT’s in de netwerk meta-analyse passen shockwave therapie toe in 3 sessies met een wekelijks interval, er is een spreiding in aantal shockwaves van 1500 tot 2000 pulses per sessie waarin de puls frequentie varieert van 4 tot 15 Hz en de druk/energiedichtheid niet consistent is beschreven in de betreffende onderzoeken. Na 3 sessies zou er dus een effect van shockwave therapie moeten worden verwacht. Er is bewijs dat het richten van de shockwave therapie op de locatie van de meeste klachten van de patiënt net zo effectief is als het richten van de shockwave op de locatie van de meeste echografische afwijkingen (Njawaya, 2017). In deze onderzoeken werd steeds radiale shockwave therapie toegepast en geen gefocusseerde shockwave therapie. Het is dus onbekend of deze resultaten geëxtrapoleerd kunnen worden naar de effecten van toepassing van gefocusseerde shockwave therapie. Wel is het effect van shockwave therapie onderzocht bij zowel insertie achilles tendinopathie als midportion achilles tendinopathie. Hoewel de resultaten op het gebeid van de insertie achilles tendinopathie niet konden worden meegenomen in een network meta-analysis, was de trend van een positief effect ook bij dit subtype tendinopathie zichtbaar.

Andere passieve behandelingen die in gerandomiseerde onderzoeken zijn onderzocht, zijn het gebruik van een nachtspalk, inlays, gebruik van collageen supplementen, toepassen van ultrageluid en frictie massages, laser therapie en licht therapie. De effecten van deze behandelingen op de VISA-A score, terugkeer naar sport en/of patiënttevredenheid lijken in het algemeen minder groot dan voor shockwave therapie. De onzekerheid van de geschatte behandeleffecten zijn ook hier echter groot. Een praktisch probleem bij het testen van de effectiviteit is het feit dat er veel aanpassingen op de behandelingen mogelijk zijn. Zo kan een nachtspalk in vele vormen en met verschillende materialen worden gemaakt en is de dorsaalflexiehoek van de enkel vaak variabel in te stellen. Een ander voorbeeld is het testen van de effectiviteit van inlays. Er bestaan geprefabriceerde inlays, maar deze kunnen ook ‘custom-made’ worden vervaardigd op basis van specifieke patiënt karakteristieken (lichamelijk onderzoek, standsafwijkingen en/of een dynamisch gangpatroon). Omdat deze laatste categorie een klinisch inzicht vereist en dus afhankelijk is van de individuele behandelaar, zal het altijd moeilijk blijven om de resultaten van een RCT op dit gebied te vertalen naar de lokale klinische praktijk.

Voor het toepassen van injectietherapie zijn er verschillende opties. Onderzochte opties in RCT’s zijn injecties met polidocanol, lidocaïne, autoloog bloed, plaatjes-rijk plasma, stromale vasculaire fractie, hyaluronzuur, prolotherapie, high-volume injectie. Andere behandelingen waarbij gebruik is gemaakt van naalden zijn acupunctuur en dry needling. Ook voor deze behandelingen geldt dat de onzekerheid van de geschatte behandeleffecten groot zijn. Op basis van de analyses die gedaan zijn naar effecten van de afzonderlijke types injectievloeistoffen, is er niet één type injectie dat superieur blijkt te zijn in effectiviteit boven de andere. Een praktisch probleem bij het testen van de effectiviteit is het feit dat er veel manieren zijn om de injecties toe te passen. De locatie van de injectie, gebruik van echografie tijdens de injectie, het volume en de dosering van de geïnjecteerde vloeistof, het toepassen van co-interventies en het aantal injecties zijn allemaal factoren die invloed kunnen hebben op de uitkomst.

Een aparte entiteit binnen de behandelcategorie injectietherapie zijn de corticosteroïden. Deze injectiebehandeling is niet in de network meta-analysis geïncludeerd omdat er geen geschikt onderzoek voorhanden was. Er is wel 1 kleine placebo-gecontroleerde RCT gepubliceerd die laat zien dat een peritendineuze injectie met corticosteroïden geen effect heeft bij patiënten met midportion achilles tendinopathie (DaCruz, 1988). Het gebruik van corticosteroïden bij tendinopathieën in het algemeen wordt ontraden wegens het slechte effect op lange termijn (Coombes, 2010).

Bijwerkingen of complicaties als gevolg van oefentherapie, orthosen, shockwave therapie, medicamenteuze therapie, acupunctuur en injectie therapie zijn weinig frequent voorkomend (tabel 5). Geen van deze conservatieve behandelopties lijkt te leiden tot serieuze bijwerkingen of complicaties. Van de oefentherapie, shockwave therapie en injectie therapie is beschreven dat deze behandelingen in de initiële fase kunnen leiden tot een toename van klachten. Shockwave therapie en injectie therapie kunnen daarnaast leiden tot respectievelijk prikkeling en roodheid van de lokale huid en zwelling van de pees. Specifiek voor corticosteroïd injecties is een verhoogde kans op een peesruptuur gerapporteerd, die toeneemt bij de toename in het aantal injecties (Seeger, 2006). Orthesen kunnen leiden tot klachten van discomfort en drukneuropathie. Medicamenteuze behandelingen zijn in een laag percentage van de gevallen geassocieerd met een milde allergische reactie. In de studie naar effecten van acupunctuur werden bijwerkingen niet gerapporteerd.

Een aantal aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen voor achilles tendinopathie is niet in RCT’s onderzocht, maar wordt wel in de praktijk toegepast. Voorbeelden daarvan zijn het toepassen van een hakverhoging, myofasciale technieken (dry needling) en Percutane Electrolyse Therapie (EPTE ofwel PNE). De werkgroepleden hebben de ervaring dat een schoenaanpassing of een hakverhoging kan leiden tot klachtenvermindering, met name als er een hoog klachten niveau in algemeen dagelijks functioneren is, zoals bij lang staan of wandelen. In de werkgroep is geen ervaring met myofasciale dry needling en Percutane Electrolyse Therapie. Gezien het ontbreken van voldoende gegevens over de effectiviteit, de veiligheid en het kostenaspect, heeft de werkgroep besloten dit soort behandelingen niet in de aanbevelingen mee te nemen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van individuen met achilles tendinopathie

Informatievoorziening over de uitvoering van oefentherapie is belangrijk voor patiënten. Welke informatie en kennis aan een patiënt moet worden overgedragen, wanneer en hoe vaak en op welke wijze de overdracht aan de patiënt optimaal kan verlopen is echter onvoldoende onderzocht en op dit moment onduidelijk. De werkgroep is van mening dat mondelinge informatie goed kan worden ondersteund door een andere vorm van informatie, bijvoorbeeld een informatiefolder of relevante informatie op betrouwbare internet bronnen (bijvoorbeeld www.sportzorg.nl). Er dient bij deze informatievoorziening tevens rekening gehouden te worden met het onderscheid tussen patiënten met een midportion achilles tendinopathie en patiënten met een insertie achilles tendinopathie. Voor de mondelinge overdracht van de informatie over tendinopathie, de monitoring van klachten, bespreken van doelen en verzorgen van persoonlijke begeleiding zijn sportartsen en (sport)fysiotherapeuten specifiek opgeleid. Andere zorgverleners met ervaring op dit gebied kunnen echter ook adequaat geëquipeerd zijn om deze taken uit te voeren. Welke specifieke zorgverlener de informatievoorziening en begeleiding verzorgt zal afhangen van de voorkeuren van de individuele patiënt. Daarnaast dient er nog rekening te worden gehouden met een patiëntengroep die een voorkeur hebben voor ‘self-management’. Communicatie om de specifieke wensen van de individuele patiënt te achterhalen is hierin van eminent belang volgens de werkgroep.

Bij de uitvoering van oefentherapie wordt er gevraagd om een tijdsbelasting voor de patiënt. Dit is vooral bij excentrische oefentherapie het geval (180 herhalingen per dag). In één studie is de duur van excentrische oefentherapie vergeleken met de duur van ‘heavy slow resistance’ oefeningen (Beyer, 2015). De duur van het excentrische oefenprogramma was 308 minuten per week, tegenover 107 minuten per week voor de ‘heavy slow resistance’ oefeningen. Deze ‘heavy slow resistance’ oefentherapie is echter praktisch lastig uit te voeren, omdat voor de oefeningen gebruik gemaakt dient te worden van een kuitspier machine in de sportschool of er dient specifieke apparatuur te worden aangeschaft.

Daarnaast adviseert de werkgroep om de patiënt te betrekken bij het opstellen van het oefentherapie programma. Eén studie heeft de effectiviteit van excentrische oefentherapie vergeleken met dosering van het aantal herhalingen van de excentrische oefentherapie binnen de acceptabele pijngrenzen. Hierbij bleken de patiënten die zelf het aantal herhalingen konden bepalen middels pijnmonitoring een betere uitkomst te hebben op korte termijn. Deze pijnmonitoring speelt ook bij de opbouwende oefentherapie een belangrijke rol (Figuur 3). Bij pijnklachten door druk van schoeisel op de achillespees tijdens de uitvoering van de oefeningen adviseert de werkgroep om de oefeningen zonder schoeisel uit te voeren.

Figuur 3 Voorgesteld stroomschema om krachtoefeningen van de kuitspieren (gastrocnemius en soleus spieren) en plyometrische oefeningen op te bouwen. De mate van pijn (gemeten middels VAS-score of NRS-schaal) die tijdens en na de oefeningen voelbaar zijn en de spier vermoeidheid zijn leidend voor de snelheid van de opbouw

Kosten

Er zijn geen studies uitgevoerd naar de (kosten)effectiviteit van het geven van patiënt educatie, belasting adviezen en adviseren en begeleiden van oefentherapie. Verwacht wordt echter dat de kosten voor de initiële uitvoering van oefentherapie laag zijn, aangezien deze grotendeels zelfstandig uitgevoerd kunnen worden. De werkgroep geeft aan dat het kan worden overwogen om de patiënt educatie, belasting adviezen en advisering en instructie van de oefentherapie in de eerste fase te laten begeleiden door een gekwalificeerde zorgverlener. Hierbij kan de informatievoorziening mondeling worden gedaan, kunnen de oefeningen worden geïnstrueerd, en is er mogelijkheid tot het stellen van vragen. Informatie via folders of via een website kunnen dit ondersteunen en de noodzaak tot frequente vervolgbezoeken terugdringen.

De directe kosten als gevolg van behandeling met orthosen, shockwave therapie, medicamenteuze therapie, acupunctuur en injectie therapie zijn naar verwachting hoger dan het geven van patiënt educatie, belasting adviezen en adviseren en begeleiden van oefentherapie. Omdat dit echter niet eerder is onderzocht in een kosteneffectiviteit studie en er geen zicht is op de beïnvloeding van indirecte kosten, zal hier niet dieper op in worden gegaan.

Aanvaardbaarheid voor de overige stakeholders

Het verstrekken van informatie en educatie kost tijd, terwijl de huidige praktijkvoering hier vaak niet op ingericht is. Daarom dient hiervoor voldoende tijd vrijgemaakt te kunnen worden. Tevens dienen platformen waarop patiënten ingelicht worden onderhouden te worden, zodat patiënten met achilles tendinopathie aldaar een deel van de voorlichting en educatie kunnen vinden. Nader onderzoek is nodig hoe dit het beste in de klinische praktijk kan worden georganiseerd: zoals door wie (de behandelend arts, paramedisch zorgverlener of een zorgondersteuner), en in welke vorm (één-op-één, via een internetplatform, et cetera).

Haalbaarheid en implementatie

Voor het verstrekken van volledige en gestandaardiseerde informatie en educatie omtrent de aandoening en de advisering en uitvoering van oefentherapie is het wenselijk dat er overeenstemming is tussen de verschillende zorgverleners. Voor de Nederlandse situatie, waar veel disciplines betrokken zijn bij de behandeling van achilles tendinopathie, is nadere uitwerking daarvan waarschijnlijk bevorderlijk voor de implementatie.

Balans tussen de argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

Gezien de vergelijkbare resultaten tussen de verschillende conservatieve behandelopties, het lage risico op complicaties, de goede praktische uitvoerbaarheid en beschikbaarheid en de verwachte lage kosten adviseert de werkgroep om behandeling te starten met patiënt educatie, belasting adviezen en opbouwende oefentherapie.

Bij de overweging voor aanvullende conservatieve behandeling adviseert de werkgroep een aantal zaken mee te nemen. De werkgroep acht de volgende overwegingen voor het toepassen van aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen van belang: 1) de veiligheid; 2) de tijdsinvestering van de patiënt; 3) de kosten en 4) de beschikbaarheid. Op basis van deze overwegingen kan de werkgroep een advies uitbrengen over het toepassen van aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen.

Indien patiënt educatie, belasting adviezen en een adequaat uitgevoerd programma met opbouwende krachtoefeningen van de kuitspieren na 3 maanden geen effect op de klachten geven, kunnen andere conservatieve behandelopties worden overwogen. Bovenstaande gegevens laten echter zien dat er veel onzekerheid is over het toegevoegde klinisch relevante effect van aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen, zowel op korte - als lange termijn. Dit gegeven hoeft er niet per definitie toe te leiden dat aanvullende behandelingen niet moeten worden overwogen. Wel geeft de werkgroep aan dat communicatie met de patiënt over de onzekerheid van de toegevoegde waarde van de behandeling vooraf noodzakelijk is en dat de overwegingen voor het toepassen van aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen moeten worden besproken met de patiënt. Op basis hiervan kan met de individuele patiënt een gewogen keuze worden gemaakt uit onderstaande aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen:

Shockwave therapie kan worden overwogen naast het continueren van de krachtoefeningen voor de kuitspieren. Shockwave therapie is veilig en voldoende beschikbaar. Deze behandeling leidt wel in de meeste gevallen tot hogere directe kosten dan de initiële behandelingen (patiënt educatie, belasting adviezen en oefentherapie). De werkgroep adviseert om na 3 sessies een evaluatie te doen en de shockwave behandeling te staken bij weinig tot geen effect of bij een volledig herstel. Indien er verbetering is opgetreden zonder volledig herstel, adviseert de werkgroep om maximaal 5 sessies shockwave therapie te overwegen. De werkgroep acht het niet aannemelijk dat het toepassen van meer dan 5 sessies een klinisch relevant verschil zal geven.

Andere aanvullende passieve behandelingen (het gebruik van een nachtspalk, inlays, gebruik van collageen supplementen, toepassen van ultrageluid en frictie massages, laser therapie en licht therapie) kunnen volgens de werkgroep worden overwogen. Het is van belang om met de patiënt te delen dat voor een aantal van deze behandelingen binnen de behandelcategorie geldt dat het geen grotere effectiviteit heeft dan oefentherapie na 1 jaar follow-up. De veiligheid van deze behandelingen is voldoende gewaarborgd en in het algemeen zijn deze behandelingen beschikbaar. Het leidt wel in de meeste gevallen tot hogere directe kosten dan de initiële behandelingen.

Het toepassen van injectietherapie (injecties met polidocanol, lidocaïne, autoloog bloed, plaatjes-rijk plasma, stromale vasculaire fractie, hyaluronzuur, prolotherapie of een high-volume injectie) of acupunctuur (intratendineuze needling) kunnen worden overwogen. Het is van belang om met de patiënt te delen dat voor een aantal van deze behandelingen binnen de behandelcategorie geldt dat het geen grotere effectiviteit heeft dan oefentherapie na 1 jaar follow-up. De veiligheid van deze behandelingen is voldoende gewaarborgd en bij gecontroleerd gebruik, zoals in de RCT’s zijn geen serieuze bijwerkingen of complicaties gerapporteerd. Bij ongecontroleerd of frequent gebruik hebben injectie behandelingen mogelijk een groter complicatie risico (infectie en peesruptuur zijn gemeld post-injectie) (Redler, 2020; Seeger, 2006). Tevens is de ervaring van de werkgroep dat injectie behandelingen door de patiënt vaak als pijnlijk worden ervaren. De beschikbaarheid van injectie behandelingen in de Nederlandse setting is goed. Het leidt wel in de meeste gevallen tot hogere directe kosten dan de initiële behandelingen. Dit wordt mede veroorzaakt doordat artsen deze behandeling uitvoeren en doordat de geïnjecteerde medicatie leidt tot hogere directe kosten. In sommige gevallen (injecties met plaatjes-rijk plasma en prolotherapie) lijkt er een effectiviteit te zijn bij herhaalde injecties, waardoor de directe kosten verder toenemen.

De werkgroep adviseert terughoudend te zijn in het voorschrijven of toepassen van een aantal aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen. De effecten van Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) zijn niet effectief gebleken. De NSAIDs hebben, met name bij ouderen, ook een ongunstig bijwerkingsprofiel. Een ander potentieel nadeel van deze medicatie is het pijnstillende effect op korte termijn en daardoor de interferentie met de belasting adviezen die de werkgroep adviseert. Het gebruik van een pijnschaal wordt hierdoor namelijk minder betrouwbaar en dit maskerende effect van de medicatie kan ertoe leiden dat patiënten meer belaste activiteiten ontplooien dan op dat moment door de achillespees kan worden verdragen. Om die reden adviseert de werkgroep terughoudend te zijn met het voorschrijven of adviseren van NSAIDs voor de behandeling van achilles tendinopathie.

De werkgroep adviseert terughoudend te zijn met het gebruik van injecties met corticosteroïden. Zoals bovenstaand vermeld, zijn er aanwijzingen dat deze behandeling niet effectief is bij patiënten met midportion achilles tendinopathie, het een ongunstig effect heeft op lange termijn, en er problemen zijn met de veiligheid van deze behandeling (dit geldt met name bij een toename in het aantal injecties) (Coombes, 2010; DaCruz, 1988; Seeger, 2006). Om bovenstaande redenen adviseert de werkgroep terughoudend te zijn met het toepassen van NSAIDs en corticosteroïd injecties.

In voorgaande nationale en internationale richtlijnen zijn er ook aanbevelingen gedaan voor de behandeling van achilles tendinopathie. In de multidisciplinaire richtlijn Chronische achilles tendinopathie (2007) is het onderwerp behandeling als aparte module beschreven. De werkgroep van de voorgaande richtlijn heeft op basis van de beschikbare literatuur beoordeeld dat de behandeling initieel dient te bestaan uit excentrische oefentherapie. In de richtlijn van 2007 wordt geadviseerd om niet te behandelen met NSAID’s, corticosteroïden en shockwave therapie. Behandelmethoden zoals scleroserende injecties en de nachtspalk dienden nader onderzocht te worden. In de NICE database zijn twee richtlijnen opgenomen over het gebruik van shockwave therapie en autoloog bloed injecties voor de behandeling van achilles tendinopathie. Hierin werd geconcludeerd dat er conflicterend bewijs van lage kwaliteit is voor het gebruik van zowel shockwave alsook autoloog bloed injecties, maar dat er geen belangrijke veiligheidsrisico’s zijn. Daarom werd aanbevolen om voor het gebruik van beide therapieën duidelijk kenbaar te maken aan de patiënt dat de effectiviteit van shockwave therapie en autoloog bloed injecties onduidelijk is. In de richtlijn van de Orthopedische sectie van de ‘American Physical Therapy Association’ worden de volgende aanbevelingen overwogen voor patiënten met midportion achilles tendinopathie: minimaal 2 maal per week oefentherapie binnen de acceptabele pijngrenzen, rekoefeningen indien er een beperkte dorsaalflexie van de enkel is, neuromusculaire oefeningen voor correctie van de kinetische keten ter vermindering van excentrische krachten op de achillespees, manuele therapie ter bevordering van range of motion van gewrichten, continueren van (sport)belasting binnen de pijngrenzen (geen complete rust), patiënt educatie, rigide taping ter vermindering van rekkrachten op de achillespees, iontoforese met dexamethason en dry needling ("Achilles Pain, Stiffness, and Muscle Power Deficits: Midportion Achilles Tendinopathy Revision 2018: Using the Evidence to Guide Physical Therapist Practice," 2018). In deze richtlijn was er onvoldoende bewijskracht om de volgende behandelingen te adviseren: een hakverhoging, een nachtspalk, orthosen en laser therapie. Behandeling met shockwave therapie, corticosteroïd injecties en plaatjes-rijk plasma injecties vielen buiten de scope van de betreffende richtlijn. Uit bovenstaande gegevens kan worden opgemaakt dat er enkele overeenkomsten en verschillen zijn met de aanbevelingen in bestaande richtlijnen. In grote lijnen komt in de verschillende richtlijnen de initiële behandeling (patiënt educatie, belasting adviezen en oefentherapie) als basis steeds naar voren en dit ondersteunt de werkgroep in de keuze om te starten met deze behandelstrategie.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Probleemstelling

Bij de diagnose achilles tendinopathie wordt normaal gesproken gestart met een conservatieve behandeling. Deze conservatieve behandelingen kunnen onderverdeeld worden in verschillende categorieën. De evaluatie van de effectiviteit van conservatieve behandelingen kan middels verschillende controle groepen worden geëvalueerd. Om die reden zijn de volgende conservatieve interventies gedefinieerd: overwegend afwachtend beleid (‘wait-and-see’), placebo behandeling, oefentherapie, orthosen, shockwave therapie, medicamenteuze therapie, acupunctuur, injectie therapie en multimodale behandelingen. Het merendeel van de patiënten ontvangt meerdere behandelingen uit deze behandelcategorieën, wat een belangrijke impact heeft op de zorgconsumptie (van der Plas, 2012). Dit wordt voornamelijk veroorzaakt doordat er onvoldoende kennis is over de effectiviteit van de verschillende behandelingen ten opzichte van elkaar.

Definities

Bij het classificeren van achilles tendinopathie heeft de werkgroep initieel de factoren locatie en klachtenduur een prominente rol gegeven. Een reactieve tendinopathie werd gedefinieerd als korter dan 6 weken bestaand en een chronische tendinopathie 3 maanden of langer bestaand (Challoumas, 2019b). Omdat er gedurende het proces van de richtlijnontwikkeling duidelijk werd dat er weinig literatuur voorhanden was van de reactieve achilles tendinopathie, er in de literatuur inconsistente definities van een reactieve tendinopathie waren en er binnen de werkgroep verschillende opvattingen waren over de definitie van deze entiteit, werd ervoor gekozen om dit onderscheid niet te maken. Er zijn daardoor twee verschillende subclassificaties van achilles tendinopathie gedefineerd. Het onderscheid tussen deze subclassificaties is gebaseerd op de locatie en geobserveerde pathologie. Een insertie tendinopathie is gelokaliseerd binnen de eerste 2 cm van de aanhechting van de achillespees op het hielbeen. Er kan hierbij sprake zijn van een tendinopathie van de achillespees insertie, een geassocieerde prominentie van de calcaneus (Haglund morfologie) en/of een bursitis retrocalcaneï (Brukner, 2012). Een midportion tendinopathie is > 2 cm boven deze aanhechting gelokaliseerd en dit betreft volgens de huidige consensus een geïsoleerde tendinopathie van het middendeel van de achillespees (Brukner, 2012). Het onderscheid tussen deze twee subclassificaties is daarnaast gerechtvaardigd, omdat er een verschil in prognose lijkt te zijn tijdens conservatieve behandeling (Fahlstrom, 2003).

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Uitkomstmaat VISA-A score

Midportion achilles tendinopathie

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Alle volgende behandelcategorieën lijken effectiever te zijn dan een overwegend afwachtend beleid na 3 maanden: oefentherapie, injectie therapie, oefentherapie+injectie therapie, shockwave therapie, oefentherapie+shockwave therapie, oefentherapie+nachtspalk, acupunctuur en mucopolysacchariden supplementen+oefentherapie.

Bronnen: (van der Vlist, 2019c) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Acupunctuur is mogelijk na 3 maanden superieur aan placebo injectie therapie, injectie therapie, oefentherapie, shockwave therapie, oefentherapie+injectie therapie en oefentherapie+nachtspalk, maar niet vergeleken met oefentherapie+shockwave therapie en mucopolysacchariden supplementen+oefentherapie.

Bronnen: (van der Vlist, 2019c) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Oefentherapie+shockwave therapie is mogelijk na 3 maanden superieur aan een placebo injectie therapie, injectie therapie, oefentherapie, shockwave therapie, oefentherapie+injectie therapie en oefentherapie+nachtspalk, maar niet vergeleken met acupunctuur en mucopolysacchariden supplementen+oefentherapie.

Bronnen: (van der Vlist, 2019c) |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Na 12 maanden lijken oefentherapie, oefentherapie+injectie therapie en oefentherapie+nachtspalk een vergelijkbare uitkomst te hebben met injectie therapie.

Bronnen: (van der Vlist, 2019c) |

Insertie achilles tendinopathie

|

- GRADE |

Er is onvoldoende literatuur van voldoende kwaliteit beschikbaar om de effectiviteit van behandelopties bij insertie achilles tendinopathie te kunnen weergeven. |

Midportion en insertie tendinopathie

|

- GRADE |

Er is geen literatuur beschikbaar om de effectiviteit van de volgende veelgebruikte behandelopties te beoordelen: • Patiënt educatie. • Belasting advies. • Hakverhoging. • Percutane Electrolyse Therapie. • Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory (NSAIDs). • Corticosteroïden injectie. |

Uitkomstmaat terugkeer naar sport

Midportion en insertie achilles tendinopathie

|

- GRADE |

Er is onvoldoende literatuur van voldoende kwaliteit beschikbaar om de effectiviteit van behandelopties middels de uitkomstmaat terugkeer naar sport te kunnen beoordelen. |

Uitkomstmaat patiënttevredenheid

Midportion en insertie achilles tendinopathie

|

- GRADE |

Er is onvoldoende literatuur van voldoende kwaliteit beschikbaar om de effectiviteit van behandelopties middels de uitkomstmaat patiënttevredenheid te kunnen beoordelen. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Beschrijving studies

Voor de beantwoording van deze uitgangsvraag zijn in totaal 29 gerandomiseerde studies geïncludeerd. De karakteristieken en belangrijkste resultaten van deze studies zijn terug te vinden in tabel 1. Het overgrote deel van de onderzoeken (25/29 studies) onderzocht de effectiviteit van de conservatieve behandeling bij patiënten met een midportion achilles tendinopathie. De overige vier studies voerden het onderzoek uit bij patiënten met een insertie achilles tendinopathie (2 studies) en bij patiënten met een niet-gespecificeerde achilles tendinopathie (2 studies). In twee gevallen was er sprake van meerdere publicaties van één studie (de Jonge, 2010; de Jonge, 2011b; De Vos, 2010; de Vos, 2007).

De populatiegrootte varieerde tussen de 28 en de 75 deelnemers (mediaan 54) waarbij het percentage ‘lost to follow-up’ varieerde van 0 tot 26% (mediaan 10%). De gemiddelde leeftijd lag tussen de 40 en 50 jaar (mediaan 48). Het percentage mannelijke deelnemers was groter in 11 studies, tegenover 13 studies waarin het percentage vrouwelijke deelnemers groter was (mediaan percentage mannelijke deelnemers 47%). In twee studies was de verhouding man/vrouw 50% en in drie studies is deze verhouding niet gerapporteerd. Het percentage van de populatie dat sportief actief was varieerde van 31% tot 100% (mediaan 72%) in de 12 studies die dit gerapporteerd hebben. De follow-up periode voor de studies varieerde tussen de 6 en 52 weken (mediaan 25 weken).

In totaal zijn er 38 behandelopties onderzocht bij patiënten met een midportion achilles tendinopathie, twee bij patiënten met een insertie achilles tendinopathie en vier bij patiënten met een niet nader gespecificeerde achilles tendinopathie. De resultaten zijn weergegeven voor de VISA-A score als cruciale uitkomstmaat en voor de secundaire uitkomstmaten patiënttevredenheid en de terugkeer naar sport. Er is een onderverdeling gemaakt voor deze drie uitkomstmaten, waarbij voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat een netwerk meta-analyse uitgevoerd is. De secundaire uitkomstmaten zullen descriptief gepresenteerd worden.

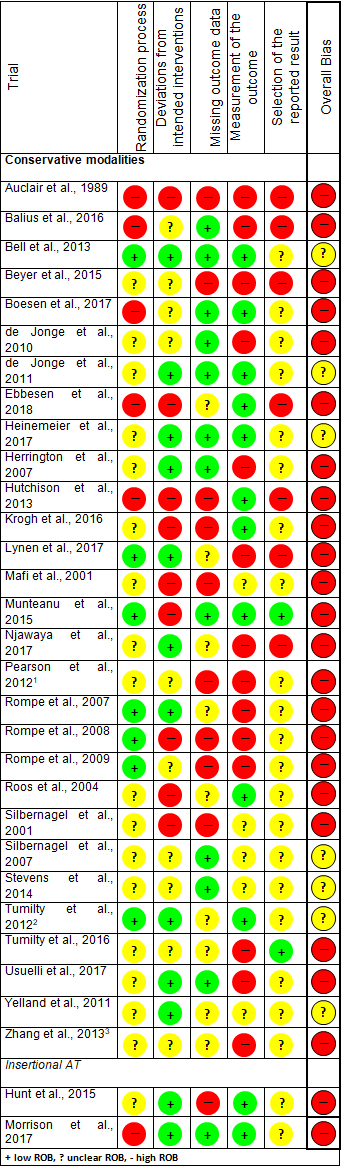

De beoordeling van het risico op bias werd door twee onafhankelijke beoordelaars gedaan met de Cochrane risk of bias 2.0 tool (Sterne, 2019). Bij een afwijkende beoordeling tussen beide beoordelaars werd er consensus gezocht en werd een 3e beoordelaar geconsulteerd indien dit noodzakelijk was. Tweeëntwintig studies (76%) lieten een hoog risico op bias zien en de overige zeven studies (24%) lieten enig risico op bias zien (tabel 2). Er waren geen studies met een laag risico op bias. Voor de gedetailleerde uitkomsten van de beoordeling van de kwaliteit van de studies verwijzen we naar tabel 2. De bewijskracht is eveneens door twee onafhankelijke beoordelaars uitgevoerd middels GRADE (Guyatt, 2008).

Resultaten

De resultaten voor deze uitgangsvraag zullen descriptief gepresenteerd worden op het niveau van behandelcategorieën. De onderverdeling van behandelopties in behandelcategorieën is weergegeven in tabel 3. Voor specificatie van de behandeling verwijzen we graag naar tabel 1. De resultaten van de netwerk meta-analyse (NMA) voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat (VISA-A score) zullen aan het einde van de resultatensectie beschreven worden (van der Vlist, 2019c). Daarin zal ook de mate van bewijskracht meegenomen worden.

Tabel 3 Onderverdeling van behandelopties in behandelcategorieën (‘classes’) van geïncludeerde studies in de NMA

|

Treatments |

Studies |

Classes |

|

Placebo-injection + eccentric exercises (high-dose) |

Bell 2013, Boesen 2017, De Jonge 2011 |

Exercise therapy + placebo injection |

|

Autologous blood injection + eccentric exercises (high-dose) |

Bell 2013, Pearson 2012 |

Exercise + injection therapy |

|

High-volume injection + eccentric exercises (high-dose) |

Boesen 2017 |

Exercise + injection therapy |

|

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) -injection + eccentric exercises (high-dose) |

Boesen 2017, De Jonge 2011 |

Exercise + injection therapy |

|

Eccentric exercises (high-dose) |

Pearson 2012, Beyer 2015, De Jonge 2010, Silbernagel 2007, Yelland 2011, Rompe 2007, Rompe 2009, Zhang 2013, Balius 2016, Stevens 2014,, Roos 2004, Mafi 2001 |

Exercise therapy |

|

Heavy slow resistance exercises |

Beyer 2015 |

Exercise therapy |

|

Night splint + eccentric exercises (high-dose) |

De Jonge 2010, Roos 2004 |

Exercise + night splint therapy |

|

Continued sports activity + eccentric exercises (high-dose) |

Silbernagel 2007 |

Exercise therapy |

|

Prolotherapy injections |

Yelland 2011 |

Injection therapy |

|

Prolotherapy injections + Eccentric exercises (high-dose) |

Yelland 2011 |

Exercise + injection therapy |

|

Shockwave therapy |

Rompe 2007 |

Shockwave therapy |

|

Wait-and-see |

Rompe 2007 |

Wait-and-see |

|

Shockwave therapy + eccentric exercises (high-dose) |

Rompe 2009 |

Exercise + shockwave therapy |

|

Acupuncture treatment |

Zhang 2013 |

Acupuncture therapy |

|

Mucopolisaccharides supplement + eccentric exercises (high-dose) |

Balius 2016 |

Exercise + mucopolysaccharides supplement therapy |

|

Mucopolisaccharides supplement + passive stretching |

Balius 2016 |

Exercise + mucopolysaccharides supplement therapy |

|

Eccentric exercises as tolerated |

Stevens 2014 |

Exercise therapy |

Midportion achilles tendinopathie

Overwegend afwachtend beleid

Overwegend afwachtend beleid versus oefentherapie: Een overwegend afwachtend beleid was inferieur aan excentrische oefentherapie na 16 weken follow-up. De VISA-A score na 16 weken follow-up was 55,0 (SD 12,9) in de groep die een overwegend afwachtend beleid kreeg en 75,6 (SD 18,7) in de groep die excentrische oefentherapie uitvoerde (p<0,001) (Rompe, 2007).

Placebo behandeling

In totaal bestonden twee gerandomiseerde studies uit minstens één behandelarm met enkel een placebo behandeling zonder co-interventie. Er waren geen statistisch significante verschillen in patiënt-gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten na 1 tot 12 weken follow-up tussen de placebo behandeling en ibuprofen of lasertherapie (Heinemeier, 2017; Hutchison, 2013).

Oefentherapie

In totaal bestonden 12 gerandomiseerde studies uit minstens één behandelarm met alleen oefentherapie zonder co-interventie.

Oefentherapie versus overwegend afwachtend beleid: Excentrische oefentherapie was superieur aan een overwegend afwachtend beleid (wait-and-see) na 16 weken follow-up. De VISA-A score na 16 weken follow-up was 75,6 (SD 18,7) in de groep die excentrische oefentherapie uitvoerde en 55,0 (SD 12,9) in de groep die een overwegend afwachtend beleid kreeg (p<0,001) (Rompe, 2007).

Oefentherapie versus Shockwave: Er is conflicterend bewijs voor de effectiviteit van shockwave therapie in vergelijking met oefentherapie. Excentrische oefentherapie was inferieur aan shockwave therapie (3 behandelingen) na 16 weken follow-up in één van de twee geïncludeerde studies. De VISA-A score na 16 weken follow-up was in deze studie 86,5 (SD 16,0) in de groep die shockwave behandelingen onderging en 73,0 (SD 19,0) in de groep die excentrische oefentherapie uitvoerde (p=0,0016) (Rompe, 2009). Een eerdere studie van deze onderzoeksgroep met drie behandelarmen liet geen significant verschil zien in de patiënt-gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten tussen excentrische oefentherapie en shockwave therapie (3 behandelingen) na 16 weken follow-up. De VISA-A score na 16 weken follow-up was 70,4 (SD 16,3) in de groep die shockwave behandelingen onderging en 75,6 (SD 18,7) in de groep die excentrische oefentherapie uitvoerde (Rompe, 2007).

Oefentherapie versus Nachtspalk (in combinatie met oefentherapie): Twee studies rapporteerden geen significante verschillen in patiënt-gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten na 12-52 weken follow-up tussen oefentherapie en het gebruik van een nachtspalk naast de uitvoering van oefentherapie (de Jonge, 2010; Roos, 2004). Eén van de deze studies vergeleek tevens de effectiviteit van oefentherapie met een nachtspalk als monotherapie, waarbij de terugkeer naar sport hoger lag in de groep die oefentherapie uitvoerde (63% versus 10%). Er zijn geen statistische testen uitgevoerd om de significantie van de verschillen weer te geven (Roos, 2004).

Oefentherapie versus Injectie: Twee studies vergeleken excentrische oefentherapie zonder co-interventie met een vorm van injectietherapie. De eerste studie liet zien dat de VISA-A score significant hoger was na 6 tot 52 weken follow-up in de groep waarbij prolotherapie werd toegediend (4 tot 12 behandelingen) in combinatie met excentrische oefentherapie, in vergelijking met excentrische oefentherapie alleen (p<0,01). De VISA-A score na 52 weken follow-up was 91,4 (SD 9,9) in de groep die prolotherapie ondergingen in combinatie met excentrische oefentherapie en 84,9 (SD 18,2) in de groep die enkel excentrische oefentherapie uitvoerde. Er was geen significant verschil tussen excentrische oefentherapie en het alleen toepassen van prolotherapie (4 tot 12 behandelingen, zonder vorm van oefentherapie) op alle tijdspunten (Yelland, 2011). De tweede studie liet geen significante verschillen zien in VISA-A score na 6 tot 12 weken follow-up tussen excentrische oefentherapie en een injectie met autoloog bloed in combinatie met excentrische oefentherapie (Pearson, 2012).

Vergelijking tussen verschillende soorten oefentherapie programma’s: In vijf studies werden twee soorten oefentherapie programma’s direct met elkaar vergeleken. Twee studies lieten een significant effect van een specifieke vorm van oefentherapie zien. In de eerste studie was de patiënttevredenheid na 12 weken follow-up significant hoger in de groep die excentrische oefentherapie uitvoerde (88% tevreden), in vergelijking met de groep die concentrische oefentherapie uitvoerde (36% tevreden) (Mafi, 2001). In de tweede studie was de VISA-A score na 3 weken follow-up significant hoger in de groep die excentrische oefentherapie uitvoerde in een aantal dagelijkse herhalingen dat binnen de acceptabele pijngrenzen uitvoerbaar was (VISA-A score 56,2, SD 19,7), in vergelijking met de groep die een vast aantal van 180 herhalingen per dag voor dezelfde oefentherapie uitvoerde (41,0, SD 13,0, p=0,004). Na 6 weken follow-up waren er geen significante verschillen in VISA-A score tussen beide groepen. Daarnaast was er geen significant verschil in patiënttevredenheid tussen beide groepen na 6 weken follow-up (Stevens, 2014).

Drie studies lieten geen significante verbetering door een specifieke vorm van oefentherapie zien. In de eerste studie bestond er geen significant verschil in VISA-A score en patiënttevredenheid na 12 tot 52 weken follow-up tussen excentrische oefentherapie en ‘heavy slow resistance’ oefentherapie (Beyer, 2015). De tweede studie liet geen significant verschil in VISA-A score zien na 6 tot 52 weken follow-up tussen het voortzetten van de sportbelasting met een pijnschaal (maximale pijnscore 5 op een schaal van 10) in de eerste 6 weken van het herstel versus het staken van belastende sporten voor de achillespees in deze fase. Beide groepen voerden daarnaast excentrische oefentherapie uit (Silbernagel, 2007). De laatste studie liet geen significant verschil in terugkeer naar sport zien na 52 weken follow-up tussen isotone oefentherapie en geleidelijk opbouwende oefentherapie (gefaseerd programma van rekoefeningen naar concentrische en uiteindelijk excentrische oefenvormen). Beide groepen voerden daarnaast rekoefeningen uit (Silbernagel, 2001).

Orthosen

In totaal bestond één gerandomiseerde studie uit minstens één behandelarm met enkel een nachtspalk zonder co-interventie. Er zijn geen statistische testen uitgevoerd naar de verschillen in terugkeer naar sport. Wel bestond er de indruk dat de terugkeer naar sport lager was indien een nachtspalk als monotherapie toegepast werd (10%), in vergelijking met oefentherapie als monotherapie (63%) en met een combinatie van oefentherapie en een nachtspalk (38%) (Roos, 2004).

Shockwave therapie

In totaal bestonden twee gerandomiseerde studies uit minstens één behandelarm met enkel shockwave therapie zonder co-interventie. De eerste studie liet zien dat shockwave therapie (3 behandelingen) superieur is aan een overwegend afwachtend beleid na 16 weken follow-up. De VISA-A score na 16 weken follow-up was 70,4 (SD 16,3) in de groep die shockwave therapie onderging en 55,0 (SD 12,9) in de groep die een overwegend afwachtend beleid kreeg (p<0,001). Er was binnen deze zelfde studie met drie behandelarmen geen sprake van een significant verschil tussen shockwave therapie (3 behandelingen) en excentrische oefentherapie (Rompe, 2007). In de tweede studie was de VISA-A score na 12 en 26 weken follow-up significant lager in de groep die shockwave therapie onderging (VISA-A score na 12 weken 47,5 (SD 15,0), na 26 weken 52,0 (SD 15,0), in vergelijking met een tweetal peritendineuze hyaluronzuur injecties (VISA-A score na 12 weken 73,0 (SD 24,0), na 26 weken (75,0 (SD 22,0)) (Lynen, 2017).

Overige passieve modaliteiten

In totaal bestonden twee gerandomiseerde studies uit minstens één behandelarm met enkel een passieve modaliteit zonder co-interventie. In de eerste studie waren er geen statistisch significante verschillen in patiënt-gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten na 6 tot 12 weken follow-up tussen Intense Pulse Light (IPL; flitslamp) en een placebo behandeling met IPL (Hutchison, 2013). De tweede studie liet zien dat het toevoegen van excentrische oefentherapie aan passieve modaliteiten bestaande uit massage, therapeutisch ultrageluid en rekoefeningen een verbetering geeft ten opzichte van de passieve modaliteiten als monotherapie. De VISA-A score was 81 (SD 1) bij de passieve modaliteiten als monotherapie en 98 (SD 2) bij het toevoegen van excentrische oefeningen (p=0,01).

Medicatie

In totaal bestonden twee gerandomiseerde studies uit minstens één behandelarm met enkel een medicamenteuze behandeling zonder co-interventie. Er waren geen statistisch significante verschillen in patiënt-gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten na 1 tot 3 weken follow-up tussen de placebo behandeling en topicale NSAIDs (één studie) of ibuprofen tabletten (één studie) (Auclair, 1989; Heinemeier, 2017).

Acupunctuur

In totaal bestond één gerandomiseerde studies uit minstens één behandelarm met enkel acupunctuur behandeling zonder co-interventie. Deze studie liet zien dat de VISA-A score significant hoger was na 8 tot 24 weken follow-up in een groep die behandeld is met acupunctuur (24 behandelingen), in vergelijking met excentrische oefentherapie (P<0,0001). Na 24 weken follow-up was de VISA-A score in de acupunctuur groep 73,3 (SD 3,6) en in de groep die excentrische oefentherapie uitvoerde 62,4 (SD 4,2) (Zhang, 2013).

Injectiebehandeling

In totaal bestonden drie gerandomiseerde studies uit minstens één behandelarm met enkel een injectiebehandeling zonder co-interventie. Alle studies onderzochten een andere vorm van injectietherapie. De eerste studie liet zien dat de VISA-A score na 12 en 26 weken follow-up significant hoger was in de groep die twee peritendineuze hyaluronzuur injecties kreeg (VISA-A score na 12 weken 73,0 (SD 24,0), na 26 weken 75,0 (SD 22,0), in vergelijking met shockwave therapie (VISA-A score na 12 weken 47,5 (SD 15,0) en na 26 weken 52,0 (SD 15,0) (Lynen, 2017). De tweede studie liet geen significant verschil zien tussen excentrische oefentherapie en het alleen toepassen van prolotherapie (4 tot 12 behandelingen, zonder vorm van oefentherapie) (Yelland, 2011). De derde studie vergeleek twee verschillende injectietechnieken met elkaar, namelijk een injectie met Stromal Vascular Fraction (SVF, verkregen uit vetweefsel) en een intratendineuze injectie met plaatjesrijk-plasma. Deze studie liet zien dat de VISA-A score op zeer korte termijn (2 tot 4 weken follow-up) significant hoger was in de groep die een SVF injectie kreeg (VISA-A score na 4 weken 59,1 (SD 19,8), in vergelijking met de intratendineuze PRP-injectie (VISA-A score na 12 weken 47,5 (SD 15,9)). Na 4, 9, 17 en 26 weken waren er geen significante verschillen tussen de twee groepen (Usuelli, 2017).

Multimodale behandelopties

Er zijn in totaal 11 multimodale behandelingen (waarin twee of meer behandelingen tegelijkertijd zijn toegepast per behandelarm) in gerandomiseerde studies met elkaar vergeleken. Een overzicht van deze multimodale behandelingen is weergegeven in tabel 4.

Tabel 4 Overzicht van gerandomiseerde studies die multimodale behandelopties hebben vergeleken bij de behandeling van patiënten met een midportion achilles tendinopathie. De aanwezigheid van effectieve multimodale behandelopties is gemarkeerd middels een grijsgekleurde balk. Voor de bewijskracht verwijzen we naar de evidence tabellen.

|

Comparison |

Study (first author) |

|

|

Injection-based multimodal treatment |

|

|

|

Autologous blood injection+eccentric exercises (high-dose) versus. Dry-needling (placebo-injection)+eccentric exercises (high-dose) |

Bell = |

|

|

High-volume injection+eccentric exercises (high-dose) versus. Placebo injection + Eccentric training (high-dose) |

Boesen ↑ |

|

|

PRP-injection+eccentric exercises (high-dose) versus. Placebo injection + Eccentric training (high-dose) |

Boesen ↑, de Jonge = |

|

|

PRP-injection+eccentric training (low-dose) versus. placebo injection+eccentric exercises (low-dose) |

Krogh = |

|

|

Medication-based multimodal treatment |

|

|

|

MCVC tablet+eccentric exercises (high-dose) versus. MCVC tablets+passive stretching |

Balius = |

|

|

Orthoses-based multimodal treatment |

|

|

|

Customised foot orthoses+eccentric exercises (high-dose) versus. Sham foot orthoses+eccentric exercises (high-dose) |

Munteanu = |

|

|

Passive modalities-based multimodal treatment |

|

|

|

Continued sports activity+progressive Achilles tendon-loading strengthening program (high-dose) versus. Active rest group+progressive Achilles tendon-loading strengthening program (high-dose) |

Silbernagel 2007 = |

|

|

Low-level laser therapy + eccentric exercise therapy (high-dose) versus. Placebo laser therapy + eccentric exercise therapy (high-dose) |

Tumilty 2012 =, Tumilty 2016 = |

|

|

Low-level laser therapy + eccentric exercise therapy (low-dose) versus. Placebo laser therapy + eccentric exercise therapy (low-dose) |

Tumilty 2016 ↑ |

|

|

Low-level laser therapy + eccentric exercise therapy (high-dose) versus. Placebo laser therapy + eccentric exercise therapy (low-dose) |

Tumilty 2016 = |

|

|

Low-level laser therapy + eccentric exercise therapy (low-dose) versus. Placebo laser therapy + eccentric exercise therapy (high-dose) |

Tumilty 2016 ↑ |

|

|

Abbreviations: PRP, Platelet-rich plasma; MCVC, mucopolysaccharides, collagen type I, and vitamin C. |

|

|

Insertie achilles tendinopathie

Oefentherapie

Oefentherapie versus Shockwave: Excentrische oefentherapie was inferieur aan shockwave therapie (3 behandelingen) na 16 weken follow-up in één studie. De VISA-A score na 16 weken follow-up was in deze studie 79,4 (SD 10,4) in de groep die shockwave behandelingen onderging en 63,4 (SD 12,0) in de groep die excentrische oefentherapie uitvoerde (p=0,005) (Rompe, 2008).

Overwegend afwachtend (wait-and-see) beleid, placebo behandeling, orthesen, shockwaven therapie, medicatie, injectiebehandeling of multimodale behandelopties

Er zijn geen studies verricht die het effect van een overwegend afwachtend beleid, placebo behandeling, orthesen, shockwaven therapie, medicatie, injectiebehandeling of multimodale behandelopties hebben onderzocht.

Midportion en insertie achilles tendinopathie (niet gespecificeerd)

Shockwave therapie

Eén gerandomiseerde studie heeft onderzocht of er sprake is van een verschil in patiënt-gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten wanneer de plaats van shockwave toepassing wordt aangegeven door de patiënt (klinisch geleid) of wanneer deze wordt bepaald middels afwijkingen op beeldvorming (echografisch geleid). Er bleek geen significant verschil te zijn tussen beide groepen na 12 weken follow-up (Njawaya, 2017).

Injectiebehandeling

Eén gerandomiseerde studie bestond uit minstens één behandelarm met enkel een injectiebehandeling zonder co-interventie. Deze studie vergeleek de effectiviteit van een polidocanol injectie met een placebo injectie. Er was daarin geen verschil in patiënt-gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten tussen beide groepen (Ebbesen, 2018).

Overwegend afwachtend (wait and see) beleid, placebo behandeling, oefentherapie, orthesen, medicatie, injectiebehandeling of multimodale behandelopties

Er zijn geen studies verricht die het effect van een overwegend afwachtend beleid, placebo behandeling, oefentherapie, orthesen, medicatie, injectiebehandeling of multimodale behandelopties hebben onderzocht.

Netwerk meta-analyse (uitkomstmaat VISA-A score)

Midportion achilles tendinopathie

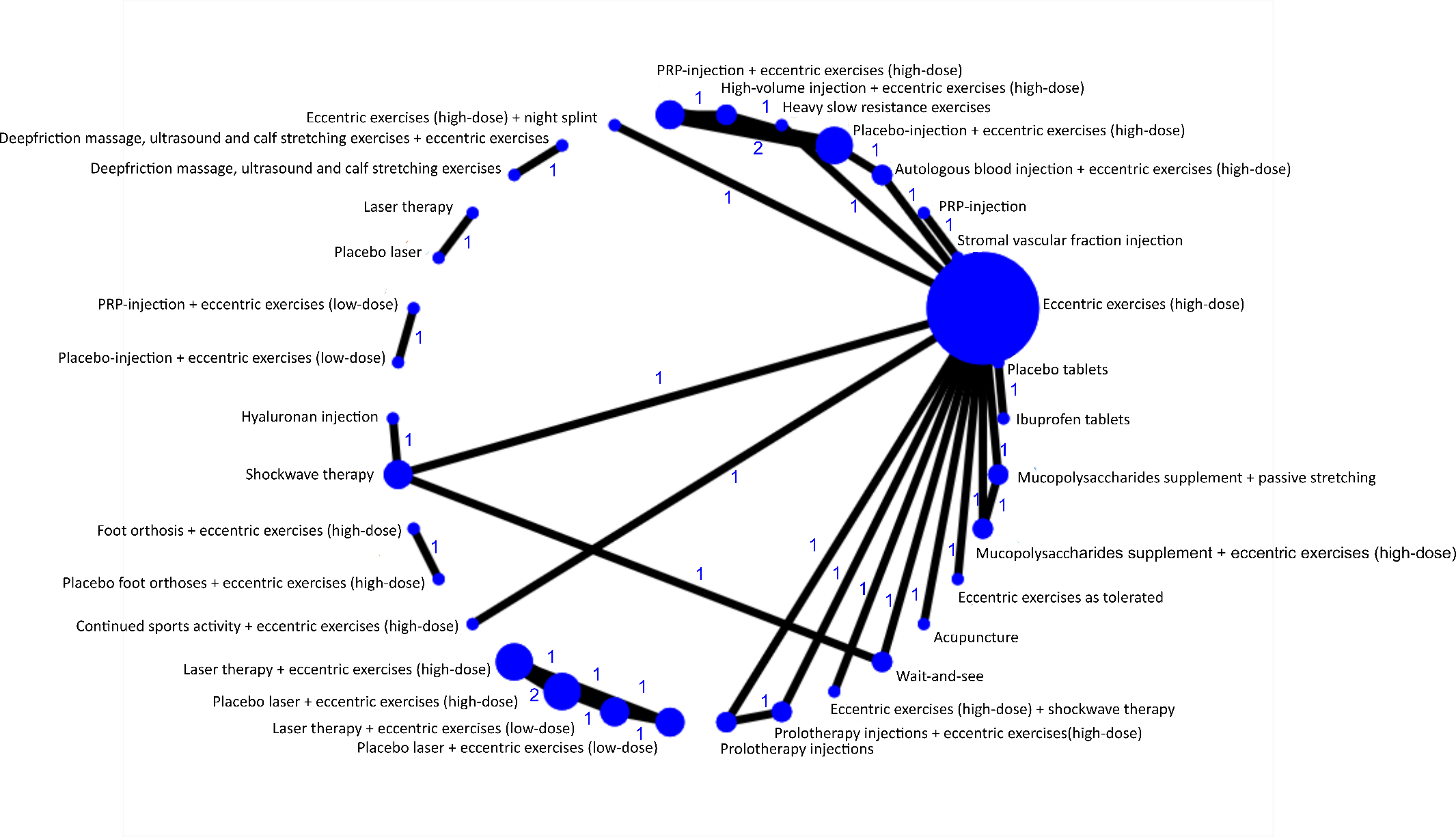

Figuur 1 a-c laten de directe vergelijkingen zien in studies waarbij een populatie met midportion achilles tendinopathie is geïncludeerd. Er zijn vanuit de overkoepelende categorie ‘multimodale behandeling’ meerdere behandelcategorieën gedefinieerd voor het vormen van het netwerk in de netwerk meta-analyse (tabel 3). Er konden 10 verschillende behandelcategorieën met in totaal 180 vergelijkingen in behandeling meegenomen worden in de NMA voor een midportion achilles tendinopathie met de VISA-A score als uitkomstmaat (van der Vlist, 2019c). Tabel 6 a-b laat de resultaten van de NMA op 3 en 12 maanden zien voor de behandelcategorieën. Deze kon niet uitgevoerd worden voor het tijdspunt van 6 maanden doordat er onvoldoende studies beschikbaar waren voor het vormen van een netwerk. De resultaten voor de vergelijkingen op het niveau van de afzonderlijke behandelingen wordt weergegeven in tabel 6.

VISA-A score op 3 maanden

Figuur 1a. Weergave van netwerk voor de VISA-A score, gemeten na afzonderlijke behandelingen na 3, 6 en 12 maanden bij patiënten met een midportion achilles tendinopathie. De grootte van de cirkel geeft het aantal patiënten dat een behandeling heeft ondergaan weer en het cijfer de hoeveelheid vergelijkingen. PRP = Plaatjesrijk-plasma, VISA-A = Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment-Achilles.

Op het tijdspunt 3 maanden leek elke behandeling superieur te zijn ten opzichte van een overwegend afwachtend beleid omdat alle actieve behandelingen gemiddeld op 15 punten of hoger uitkomen: oefentherapie+placebo injectietherapie (gemiddelde verschil 19, 95%BI -3 tot 34), injectie therapie (23, 8 tot 38), oefentherapie (20, 11 tot 30), shockwave therapie (15, 6 tot 24), oefentherapie+injectie therapie (22, 7 tot 36), oefentherapie+shockwave therapie (34, 21 tot 47), oefentherapie+nachtspalk (21, 4 tot 39), acupunctuur (35, 25 tot 45) en mucopolysacchariden supplementen+oefentherapie (28, 14 tot 41).

Acupunctuur was superieur aan placebo injectie therapie ( gemiddelde verschil 16, 4 tot 30), injectie therapie (13, 0 tot 25), oefentherapie (15, 11 tot 19), shockwave therapie (20, 9 tot 31), oefentherapie+injectie therapie (13, 2 tot 25) en oefentherapie+nachtspalk (14, -1 tot 30), maar niet aan oefentherapie+shockwave therapie (1, -9 tot 11) en mucopolysacchariden supplementen+oefentherapie (7, -3 tot 19).

Oefentherapie+shockwave therapie was superieur aan placebo injectie therapie (gemiddelde verschil 15, 1 tot 31), injectie therapie (11, -4 tot 26), oefentherapie (14, 5 tot 23), shockwave therapie als monotherapie (19, 5 tot 32), oefentherapie+injectie therapie (12, -2 tot 27) en oefentherapie+nachtspalk (13, -4 tot 30), maar niet vergeleken met acupunctuur (-1, -11 tot 9) en mucopolysacchariden supplementen+oefentherapie (6, -7 tot 20).

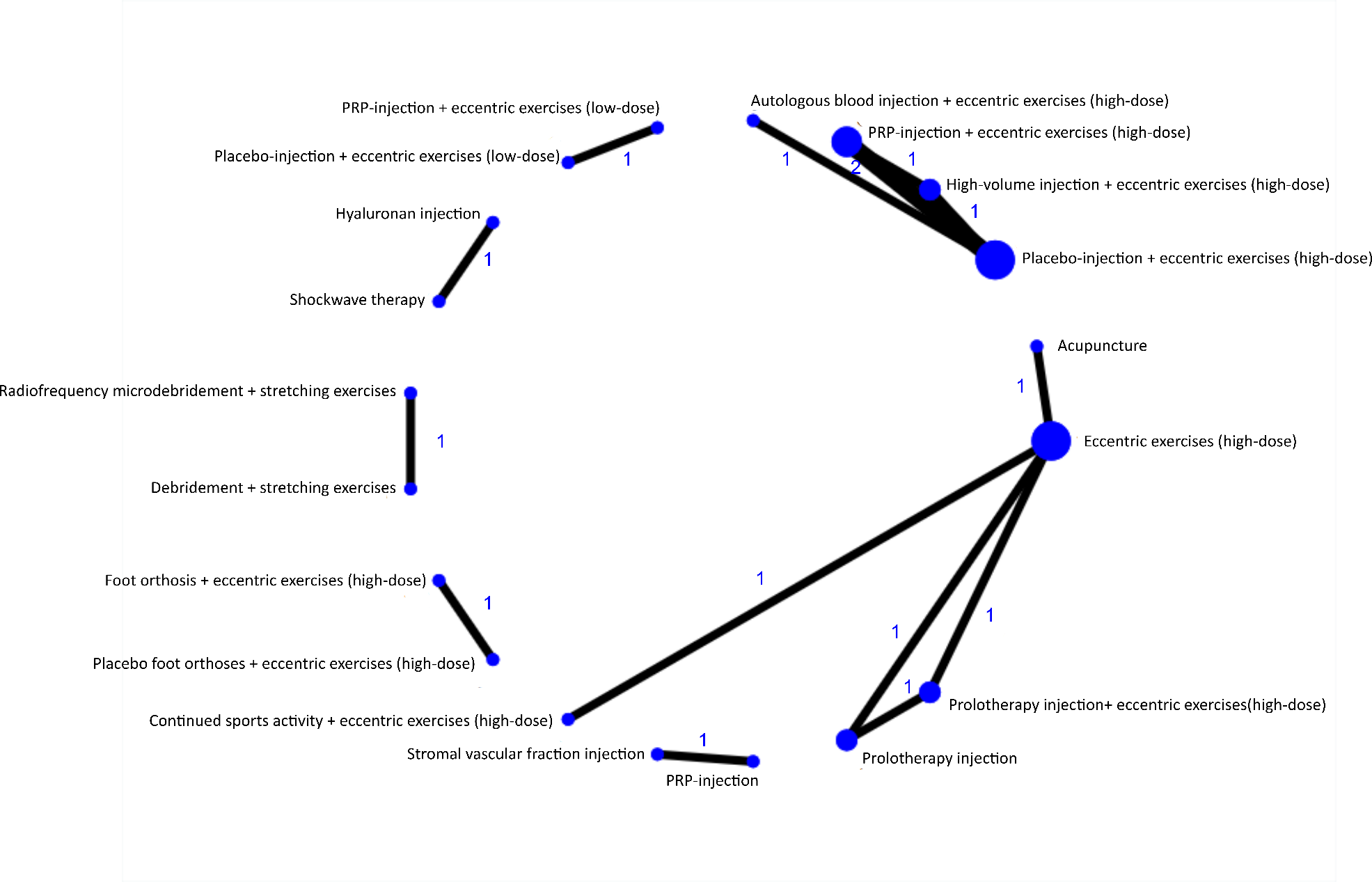

VISA-A score op 6 maanden

Figuur 1b. Weergave van netwerk voor de VISA-A score, gemeten na afzonderlijke behandelingen na 3, 6 en 12 maanden bij patiënten met een midportion achilles tendinopathie. De grootte van de cirkel geeft het aantal patiënten dat een behandeling heeft ondergaan weer en het cijfer de hoeveelheid vergelijkingen. PRP = Plaatjesrijk-plasma, VISA-A = Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment-Achilles.

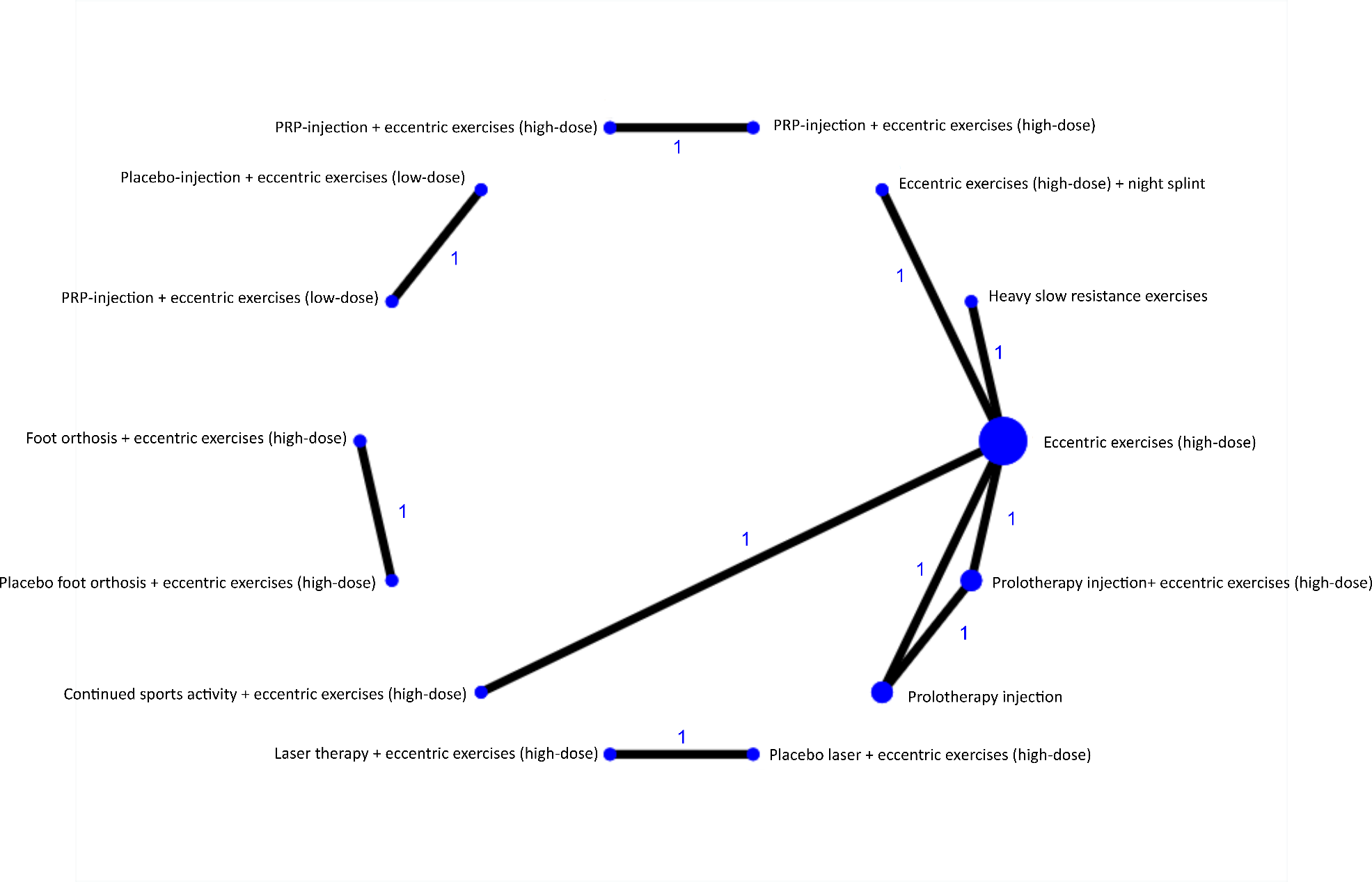

VISA-A score op 12 maanden

Figuur 1c. Weergave van netwerk voor de VISA-A score, gemeten na afzonderlijke behandelingen na 3, 6 en 12 maanden bij patiënten met een midportion achilles tendinopathie. De grootte van de cirkel geeft het aantal patiënten dat een behandeling heeft ondergaan weer en het cijfer de hoeveelheid vergelijkingen. PRP = Plaatjesrijk-plasma, VISA-A = Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment-Achilles.

Op het tijdspunt 12 maanden konden vier behandelcategorieën vergeleken worden in een netwerk. Oefentherapie (gemiddelde verschil -5, -19 tot 9), oefentherapie+injectie therapie (2, -10 tot 13) en oefentherapie+nachtspalk (3, -16 tot 22) hadden een vergelijkbare uitkomst met injectie therapie.

Insertie achilles tendinopathie

Voor insertie achilles tendinopathie en midportion en insertie achilles tendinopathie (niet gespecificeerd) konden door de kleine hoeveelheid studies zonder vergelijkbare behandelingen geen netwerken gevormd worden.

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

De bewijskracht is gebaseerd op resultaten uit RCT’s en start derhalve hoog. Alle vergelijkingen uit de NMA werden gegradeerd als laag-zeer laag, behalve voor oefentherapie+injectie met autoloog bloed versus oefentherapie+placebo injectie waarbij sprake was van een redelijke bewijskracht. De voornaamste reden om de bewijskracht te verlagen waren studie limitaties (n=180 vergelijkingen, 100%) en imprecisie (n=158 vergelijkingen, 88%) (tabel 7).

Netwerk meta-analyse (uitkomstmaten terugkeer naar sport en patiënttevredenheid)

Midportion en insertie achilles tendinopathie

Door een kleine hoeveelheid vergelijkingen in de studies die deze uitkomstmaten rapporteren heeft de werkgroep besloten om geen netwerk analyse uit te voeren voor de beantwoording van de huidige submodule.

Zoeken en selecteren

Voor de beantwoording van submodules ‘Conservatieve behandelopties’, ‘Operatieve behandelopties’ en ‘Factoren die de effectiviteit behandeling beïnvloeden’ is één systematische literatuuranalyse uitgevoerd, die is gericht op gerandomiseerde studies die de effectiviteit van behandelopties voor achilles tendinopathie beoordeeld hebben. Deze resultaten zullen ook apart gepubliceerd worden in een wetenschappelijk tijdschrift. De volgende PICO werd opgesteld voor de beantwoording van deze vraag:

P: patiënten met achilles tendinopathie;

I: actieve conservatieve behandelopties;

C: Overwegend afwachtend beleid, wachtlijst controle of een andere actieve behandeling;

O: ervaren klachten (VISA-A score, patiënttevredenheid en terugkeer naar sport).

Relevante uitkomstmaten

Relevante uitkomstmaten zijn bepaald op basis van informatie van vragenlijstonderzoek dat is uitgevoerd in samenwerking met de Patiëntenfederatie onder 97 patiënten met achilles tendinopathie. Daarnaast is er nog een diepte interview uitgevoerd bij negen patiënten met midportion achilles tendinopathie. De cruciale uitkomstmaat voor submodules ‘Overwegend afwachted (wait-and-see) beleid’, ‘Conservatieve behandelopties’ en ‘Operatieve behandelopties’ is de Victorian Institute of Sports Assessment-Achilles (VISA-A) score tijdens de laatste follow-up meting van het onderzoek. De gevalideerde VISA-A vragenlijst bestaat uit acht vragen die drie domeinen omvatten: pijn in ADL activiteiten, tijdens functie testen en (sport)belasting (Robinson, 2001). Een score van 100 punten is optimaal en staat voor een volledig belastbare achillespees zonder aanwezigheid van pijnklachten, een score van 0 punten representeert een zeer laag belastbare achillespees met de aanwezigheid van ernstige pijnklachten. Belangrijke (maar niet cruciale) uitkomstmaten zijn de patiënttevredenheid en terugkeer naar sport. De patiënttevredenheid dient patiënt-gerapporteerd te zijn, waarbij het type gehanteerde schaal niet een exclusie criterium is voor deze richtlijn. De terugkeer naar sport dient tevens patiënt-gerapporteerd te zijn, waarbij de gehanteerde schaal wederom niet een exclusie criterium is voor deze richtlijn. Bijwerkingen en complicaties van de behandeling werden ook in overweging genomen om de veiligheid van de verschillende behandelopties te beoordelen.

Klinisch relevante verschillen voor de VISA-A score zijn gerapporteerd in eerdere onderzoeken, maar kennen een grote spreiding van 6,5 tot 25 punten (de Jonge, 2010; Iversen, 2012; Khan, 2003; McCormack, 2015; Tumilty, 2008). In een recent onderzoek is er in een grote patiëntenpopulatie met de meest geaccepteerde ‘anchor-based’ methode berekend dat het klinisch relevante verschil van de VISA-A score 15 punten is na 3 maanden conservatieve behandeling (Lagas, 2019c). Omdat deze studie het meest betrouwbaar is en de waarde ook midden in de spreiding van de andere onderzoeksresultaten valt, baseert de werkgroep zich op het klinisch relevante verschil van 15 punten. De uitkomstmaten patiënttevredenheid en terugkeer naar sport zijn niet gevalideerd en daarvoor zijn geen klinisch relevante verschillen beschikbaar. Om die reden worden deze belangrijke uitkomstmaten ook in de overweging geïnterpreteerd, zonder het gebruik van vooraf gedefinieerde afkappunten.

Zoeken en selecteren (methode)

In samenwerking met de medische bibliothecaris van het Erasmus MC is op 26 februari 2019 een zoekopdracht opgesteld naar gerandomiseerde studies waarin de effectiviteit van een behandeloptie voor achilles tendinopathie beoordeeld is (zie werkwijze onder het tabblad verantwoording). Er is gezocht naar relevante literatuur in de volgende databases: Embase, Medline Ovid, Web of Science, Cochrane CENTRAL, CINAHL EBSCOhost, SportDiscuss EBSCOhost en Google Scholar. Er zijn geen taalrestricties gehanteerd. Potentieel relevante studies werden op basis van de onderstaande criteria beoordeeld.

Inclusiecriteria:

- Het artikel onderzoekt de effectiviteit van een conservatieve behandeloptie voor achilles tendinopathie.

- De diagnose achilles tendinopathie is gesteld op basis van klinische bevindingen (lokale pijn en verminderde belastbaarheid).

- De onderzoekspopulatie is 18 jaar of ouder.

- Het artikel heeft een gerandomiseerd studie design.

Exclusiecriteria:

- 10 of minder patiënten per behandelarm.

- Geen adequate controlegroep (bijvoorbeeld achillespees contralaterale zijde).

- Het design is een preklinisch onderzoek (dierstudie of in vitro design).

Voor de beantwoording van de uitgangsvraag is daarnaast gezocht naar de aanwezigheid van bestaande nationale en internationale richtlijnen: de multidisciplinaire richtlijn Chronische achilles tendinopathie (2007) en (inter)nationale richtlijndatabases van het Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap (NHG), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), National Guidelines Clearinghouse (NGC) en Guidelines International Network (G-I-N).

Resultaten

De systematische zoekactie naar de effectiviteit van behandelopties leverde in totaal 2779 referenties op na verwijdering van duplicaties. Alle gevonden referenties werden op titel en abstract beoordeeld. Na deze voorselectie werd de volledige tekst beoordeeld van 147 artikelen. In totaal werden 118 van deze artikelen geëxcludeerd. In de aanverwante producten is een flowchart opgenomen, met daarin de redenen voor exclusie. Uiteindelijk voldeden 29 studies aan de criteria en deze zijn geïncludeerd in de literatuuranalyse voor de effectiviteit van behandelopties. Twee studies betroffen een vervolgonderzoek van een eerder gepubliceerde studie (De Vos, 2010; de Vos, 2007).

Daarnaast heeft de werkgroep zich gebaseerd op de nationale richtlijn Chronische achilles tendinopathie, in het bijzonder de tendinosis, bij sporters (VSG, 2007). In de databases van de NHG, NICE, NGC en G-I-N werden geen bestaande richtlijnen op het gebied van behandeling van achilles tendinopathie gevonden. In de NICE database zijn twee richtlijnen opgenomen over het gebruik van shockwave therapie en autoloog bloed injecties voor de behandeling van achilles tendinopathie, welke door de werkgroep in overweging zijn genomen.

Referenties

- Achilles Pain, Stiffness, and Muscle Power Deficits: Midportion Achilles Tendinopathy Revision 2018: Using the Evidence to Guide Physical Therapist Practice. (2018). J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 48(5), 425-426.

- Archambault, J. M., Wiley, J. P., Bray, R. C., Verhoef, M., Wiseman, D. A., & Elliott, P. D. (1998). Can sonography predict the outcome in patiënts with achillodynia? J Clin Ultrasound, 26(7), 335-339.

- Auclair, J., Georges, M., Grapton, X., Gryp, L., D'Hooghe, M., Meiser, R. G.,... Schmidtmayer, B. (1989). A double-blind controlled mutlicenter study of percutaneous niflumic acid gel and placebo in the treatment of Achilles heel tendinitis. CURR THER RES CLIN EXP, 46(4), 782-788.

- Balius, R., Álvarez, G., Baró, F., Jiménez, F., Pedret, C., Costa, E., & Martínez-Puig, D. (2016). A 3-Arm Randomized Trial for Achilles Tendinopathy: Eccentric Training, Eccentric Training Plus a Dietary Supplement Containing Mucopolysaccharides, or Passive Stretching Plus a Dietary Supplement Containing Mucopolysaccharides. CURR THER RES CLIN EXP, 78, 1-7.

- Bell, K. J., Fulcher, M. L., Rowlands, D. S., & Kerse, N. (2013). Impact of autologous blood injections in treatment of mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy: Double blind randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Online), 346(7908).

- Beyer, R., Kongsgaard, M., Hougs Kjær, B., Øhlenschlæger, T., Kjær, M., & Magnusson, S. P. (2015). Heavy Slow Resistance Versus Eccentric Training as Treatment for Achilles Tendinopathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. AM J SPORTS MED, 43(7), 1704-1711.

- Boesen, A. P., Hansen, R., Boesen, M. I., Malliaras, P., & Langberg, H. (2017). Effect of High-Volume Injection, Platelet-Rich Plasma, and Sham Treatment in Chronic Midportion Achilles Tendinopathy: A Randomized Double-Blinded Prospective Study. AM J SPORTS MED, 45(9), 2034-2043.

- Bowen, L., Gross, A. S., Gimpel, M., Bruce-Low, S., & Li, F. X. (2019). Spikes in acute:chronic workload ratio (ACWR) associated with a 5-7 times greater injury rate in English Premier League football players: a comprehensive 3-year study. Br J Sports Med.

- Brukner, P., & Khan, K. (2012). Brukner & Khan's Clinical Sports Medicine. Sydney: McGraw-Hill.

- Challoumas, D., Clifford, C., Kirwan, P., & Millar, N. L. (2019). How does surgery compare to sham surgery or physiotherapy as a treatment for tendinopathy? A systematic review of randomised trials. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med, 5(1), e000528.

- Cook, J. L., & Purdam, C. (2012). Is compressive load a factor in the development of tendinopathy? Br J Sports Med, 46(3), 163-168.