Diagnosegroepen

Uitgangsvraag

Welke groepen patiënten (diagnosegroepen) komen in aanmerking voor (onderdelen van) hartrevalidatie?

Aanbeveling

Verwijs patiënten met de volgende ‘absolute indicaties’ altijd voor hartrevalidatie:

- Patiënten met een uiting van coronairlijden, zowel acuut als chronisch, te weten:

- Patiënten met een acuut coronair syndroom , waaronder een acuut myocardinfarct en instabiele angina pectoris;

- Patiënten met stabiele angina pectoris;

- Patiënten die een Percutane Coronaire Interventie hebben ondergaan;

- Patiënten die een omleidingsoperatie (Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting) of open hartklepoperatie hebben gehad.

- Patiënten met chronisch hartfalen.

Overweeg verwijzing naar hartrevalidatie voor patiënten met de volgende ‘relatieve indicaties’.

- Patiënten met een aangeboren hartafwijking;

- Patiënten die een harttransplantatie hebben ondergaan;

- Patiënten die een hartklepoperatie hebben ondergaan;

- Patiënten die een ICD (Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator) of een pacemaker hebben gekregen;

- Patiënten met atriumfibrilleren of andere (behandelde) ritmestoornissen;

- Patiënten met atypische thoracale pijnklachten (hartangst);

- Patiënten die een reanimatie hebben doorgemaakt en vanwege hun onderliggend lijden niet onder een van de absolute indicaties vallen;

- Patiënten met overige cardiothoracale chirurgische ingrepen.

Beoordeel bij de individuele patiënt met een relatieve indicatie vooral of hartrevalidatie het beloop van de aandoening positief kan beïnvloeden, met name als:

- Er sprake is van beweegangst;

- Er een ernstige beperking van het fysiek functioneren bestaat als gevolg van de hartaandoening die positief beïnvloed kan worden door een revalidatieprogramma

- Leefstijlfactoren het beloop van de ziekte negatief beïnvloeden;

- Er andere factoren zijn die participatie binnen de samenleving verhinderen en waarbij het vermoeden bestaat dat deze positief beïnvloed kunnen worden door een revalidatieprogramma.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Voor deze module is een literatuuranalyse gedaan naar de effectiviteit van hartrevalidatie bij verschillende diagnosegroepen. Hierbij is er in het bijzonder gekeken naar patiënten met coronairlijden (CAD), atriumfibrilleren (AF) of hartfalen (HF).

- Patiënten met CAD

De bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat was redelijk. De bewijskracht voor belangrijke uitkomstmaten was hoog tot laag. Hartrevalidatie bij patiënten met CAD verlaagt het risico om te overlijden en resulteert in een verlichting van depressieve symptomen en leidt niet tot een verandering in het aantal ziekenhuisopnames. Mogelijk leidt hartrevalidatie ook tot een verlaging in het risico op nieuwe hart- en vaatziekten.

- Patiënten met AF

De bewijskracht voor de cruciale en belangrijke uitkomstmaten was laag. Hartrevalidatie bij patiënten met AF heeft mogelijk geen effect op ziekenhuisopnames of verlichting van depressieve symptomen. Mogelijk resulteert hartrevalidatie wel in verbetering van angststoornissen.

- Patiënten met HF

De bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten was laag tot zeer laag. De bewijskracht voor belangrijke uitkomstmaten was redelijk tot zeer laag. Hartrevalidatie bij patiënten met HF verlaagt op de korte termijn (6 tot 12 maanden) mogelijk het risico op ziekenhuisopnames en verbetert mogelijk de kwaliteit van leven. We zijn onzeker over de effectiviteit van hartrevalidatie op mortaliteit. Op de lange termijn (> 12 maanden) zorgt hartrevalidatie mogelijk voor een afname in het risico op hart- en vaatziekten.

Het is belangrijk nog te benoemen dat er gefocust is op literatuur met een lange follow-up (> 12 maanden). Mogelijkerwijs kunnen er korte termijneffecten (< 12 maanden) zijn, maar deze zijn in de huidige analyse niet bekeken (behalve voor hartfalenpatiënten tussen 6 en 12 maanden). Daarnaast waren de interventies toegepast in de trials divers. Ondanks deze diversiteit aan vormen van hartrevalidatie blijven de positieve effecten op de genoemde uitkomsten behouden.

Indicaties: diagnosegroepen voor hartrevalidatie

Na het (recent) doormaken van een cardiaal incident worden de meeste hartpatiënten verwezen voor hartrevalidatie. Daarnaast kunnen ook hartpatiënten met een meer chronische ziekte in aanmerking komen voor hartrevalidatie. Al kan de timing van het verwijzen naar hartrevalidatie bij chronische ziekten soms lastig zijn. In het bijzonder bij patiënten met stabiele angina pectoris kan dit een issue zijn. Veelal worden patiënten verwezen na een cardiale interventie zoals een PCI of CABG, maar ook slechts een medicamenteuze behandeling is een voorkomende verwijsreden. Stabiele angina pectoris is, net al andere vormen van coronairlijden, onderdeel van het chronisch coronair syndroom. Het onderliggende lijden, te weten artherosclerose, is bij alle uitingen van coronairlijden hetzelfde. De meeste studies die gedaan zijn bij patiënten met coronairlijden includeren patiënten langs het hele spectrum van het chronisch coronair syndroom of enkel mensen na een acuut coronair syndroom of cardiale interventie. Aangezien studies naar patiënten met stabiele angina pectoris, in het bijzonder medicamenteus behandeld of met een PCI, niet voor handen zijn en het onderliggend lijden hetzelfde is, is voor de literatuuranalyse gekozen om te zoeken naar literatuur bij patiënten met coronairlijden. Uit deze analyse is naar voren gekomen dat hartrevalidatie bij patiënten met coronairlijden het risico om te overlijden verlaagt en mogelijk het risico hart- en vaatziekten verlaagt. Naast de literatuuranalyse onder patiënten met coronairlijden laat ook een recente Nederlandse observationele studie een positief effect zien op mortaliteit bij patiënten met stabiele angina pectoris. Uit deze studie (Eijsvogels, 2020) met een subgroepanalyse onder bijna 25.000 deelnemers met stabiele angina pectoris wordt een verlaagd risico op overlijden gevonden (HR 0,69 95%BI 0,63 tot 0,76, geadjusteerd voor belangrijke confounders). Tezamen nemend is er voldoende bewijs dat ook bij patiënten met stabiele angina pectoris, ongeacht de behandeling, hartrevalidatie baat heeft.

Hartrevalidatie is vrijwel altijd mogelijk, omdat het programma op maat wordt aangeboden (Jolliffe, 2001). Deze richtlijn maakt onderscheid in absolute indicatie (patiënten met aandoeningen waarvoor in principe altijd een indicatie voor hartrevalidatie geldt) en relatieve indicaties (patiënten waarbij in voorkomende gevallen een indicatie voor hartrevalidatie kan zijn)

Absolute indicaties

De diagnosegroepen die vallen onder de absolute indicaties en op basis hiervan altijd doorverwezen moeten worden zijn:

- Patiënten met een uiting van coronairlijden, hetzij acuut of chronisch (oftewel ongeacht welke vorm) te weten:

- Patiënten met een acuut coronair syndroom, waaronder een acuut myocardinfarct en instabiele angina pectoris;

- Patiënten met stabiele angina pectoris;

- Patiënten die een Percutane Coronaire Interventie hebben ondergaan;

- Patiënten die een omleidingsoperatie (Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG)) of open hartklepoperatie hebben gehad.

- Patiënten met chronisch hartfalen, ongeacht de gemeten linkerventrikelejectiefractie (dat wil zeggen, inclusief HFpEF, HFmrEF, HFrEF) en ongeacht of patiënten al dan niet een left ventricular assist device (LVAD) of ander cardiaal device hebben. Hierbij is de werkgroep wel van mening dat voor patiënten met een LVAD de revalidatie, gezien beperkte ervaring hiermee, het best kan worden verricht in een centrum dat hier expertise in heeft. Zie hiervoor ook module Complexe Hartrevalidatie.

Op grond van de literatuur kan gesteld worden dat voor bovenstaande groepen patiënten het bewijs is geleverd dat hartrevalidatie zinvol en effectief is. Met hartrevalidatie kunnen bij deze patiënten afhankelijk van de diagnose de volgende effecten worden bereikt:

- Afname van de cardiale mortaliteit;

- Afname van het risico op nieuwe of verergering van bestaande hart- en vaatziekten;

- Toename van inspanningscapaciteit;

- Toename van myocardiale oxygenatie;

- Verbetering van het lipidenprofiel (daling van LDL- en stijging van HDL-cholesterol);

- Toename van het zelfvertrouwen;

- Vermindering van depressieve symptomen en angstsymptomen.

Relatieve indicaties

Voor een aantal patiëntengroepen is het wetenschappelijk bewijs wat minder sterk. De projectgroep adviseert om bij de volgende patiëntengroepen, samen met de patiënt, hartrevalidatie te overwegen:

- Patiënten met een aangeboren hartafwijking;

- Patiënten die een harttransplantatie hebben ondergaan;

- Patiënten die een hartklepoperatie hebben ondergaan;

- Patiënten die een ICD (Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator) of een pacemaker hebben gekregen;

- Patiënten met atriumfibrilleren of andere (behandelde) ritmestoornissen;

- Patiënten met atypische thoracale pijnklachten (hartangst);

- Patiënten die een reanimatie hebben doorgemaakt en vanwege hun onderliggend lijden niet onder een van de absolute indicaties vallen;

- Patiënten met overige cardiothoracale chirurgische ingrepen.

Bij twijfel dient een patiënt in elk geval te worden doorverwezen. Tijdens het intakegesprek kan via screening worden vastgesteld of er een indicatie voor hartrevalidatie is.

Contra-indicaties voor hartrevalidatie

Er bestaan voldoende relatief belemmerende factoren voor hartrevalidatie maar bijna geen absolute contra-indicaties voor hartrevalidatie an sich. Het komt vaker voor dat er een contra-indicatie is voor individuele onderdelen van de hartrevalidatie. Hiervoor verwijzen wij graag naar respectievelijk, de modules Contra-indicaties fysieke doelen en Contra-indicaties met betrekking tot psychisch functioneren. Ook kan er bijvoorbeeld een indicatie zijn voor gespecialiseerde revalidatie. Denk hierbij aan patiënten na een harttransplantatie en patiënten met een LVAD. Hiervoor verwijzen wij graag naar de module Complexe Hartrevalidatie.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het is belangrijk op te merken dat de waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten voor hartrevalidatie sterk kunnen variëren, omdat ze afhankelijk zijn van de individuele behoeften, doelen en omstandigheden van de patiënt. Over het algemeen kunnen de volgende punten worden beschouwd als waarden en voorkeuren die veel patiënten belangrijk vinden in het kader van hartrevalidatie:

- Kwaliteit van leven: Patiënten geven vaak de hoogste prioriteit aan het herstellen van hun kwaliteit van leven na een hartaandoening. Ze willen in staat zijn om dagelijkse activiteiten uit te voeren, weer actief te zijn en hun onafhankelijkheid te behouden.

- Informatie en educatie: Patiënten willen goed geïnformeerd worden over hun aandoening, behandelingsmogelijkheden en leefstijlveranderingen. Educatieve hulpmiddelen en voorlichting zijn belangrijk.

- Monitoren en meten van vooruitgang: Patiënten willen hun vooruitgang kunnen volgen en begrijpen. Het gebruik van meetbare doelen en regelmatige evaluaties kan nuttig zijn.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De kosteneffectiviteit van hartrevalidatie voor patiënten met hart- en vaatziekten kan variëren afhankelijk van verschillende factoren, waaronder de specifieke programma's, de gezondheidstoestand van de patiënt, de behandelingskosten en de uitkomsten die worden gemeten. Over het algemeen heeft hartrevalidatie aangetoond dat het kosteneffectief kan zijn, hoewel de exacte cijfers afhankelijk zijn van verschillende variabelen.

Hier zijn enkele punten om te overwegen:

- Verbetering van de gezondheid: Hartrevalidatieprogramma's richten zich op lichamelijke activiteit, dieetaanpassingen, psychosociale ondersteuning en educatie. Door deel te nemen aan deze programma's kunnen patiënten hun fysieke conditie verbeteren, risicofactoren verminderen en hun algemene gezondheidstoestand verbeteren, wat kan leiden tot een betere kwaliteit van leven en mogelijk lagere toekomstige gezondheidskosten.

- Voorkomen van heropnames: Hartrevalidatie kan helpen bij het verminderen van heropnames voor hart- en vaatziekten, waardoor de totale kosten van de gezondheidszorg kunnen worden verminderd.

- Productiviteit en arbeidsdeelname: Door de gezondheid van patiënten te verbeteren, kan hartrevalidatie hen in staat stellen om weer aan het werk te gaan of actief te blijven, wat de economische productiviteit kan bevorderen.

- Kosten van het programma: De kosteneffectiviteit kan ook afhangen van de kosten van het hartrevalidatieprogramma zelf, zoals de kosten van begeleiding, apparatuur, en de duur van het programma.

Over het algemeen suggereren veel studies en analyses dat hartrevalidatie kosteneffectief kan zijn, vooral op lange termijn, vanwege de gezondheidsvoordelen en de mogelijke kostenbesparingen in de gezondheidszorg. Echter, de exacte cijfers en conclusies kunnen variëren afhankelijk van de specifieke situatie en regio. Kosteneffectiviteitsanalyses kunnen worden uitgevoerd om de specifieke voordelen en kosten van hartrevalidatie in een bepaalde context te beoordelen. Het is belangrijk om te overleggen met zorgprofessionals en beleidsmakers om de meest relevante gegevens en aanbevelingen te verkrijgen voor uw specifieke situatie.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Hartrevalidatie is een belangrijk onderdeel van de behandeling en zorg voor patiënten met hart- en vaatziekten. Hier zijn argumenten voor de aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie van hartrevalidatie:

Aanvaardbaarheid:

- Klinisch bewezen effectiviteit: Hartrevalidatieprogramma's hebben een aanzienlijke verbetering aangetoond in de klinische uitkomsten bij patiënten met hart- en vaatziekten. Dit maakt ze aanvaardbaar voor patiënten, omdat ze weten dat ze echt kunnen profiteren van deelname.

- Verbeterde levenskwaliteit: Hartrevalidatie kan de levenskwaliteit van patiënten verbeteren door hen te helpen fysiek en emotioneel sterker te worden en de angsten en zorgen over hun gezondheid aan te pakken.

- Individuele aanpassing: Hartrevalidatieprogramma's zijn vaak flexibel en kunnen worden aangepast aan de individuele behoeften van patiënten, wat de aanvaardbaarheid verhoogt.

Haalbaarheid:

- Beschikbaarheid van programma's: Hartrevalidatieprogramma's zijn wijdverspreid en toegankelijk, wat de haalbaarheid vergroot. Ze worden aangeboden in ziekenhuizen, klinieken en zelfs online.

- Interdisciplinaire aanpak: Hartrevalidatie omvat meerdere disciplines, waaronder cardiologen, fysiotherapeuten, diëtisten en psychologen, wat de haalbaarheid van een uitgebreide zorgbenadering verbetert.

- Verzekeringsdekking: Veel zorgverzekeringen dekken hartrevalidatieprogramma's, wat de financiële haalbaarheid vergroot voor patiënten.

Implementatie:

- Training van zorgverleners: Het trainen van zorgverleners om hartrevalidatieprogramma's op te zetten en uit te voeren, is essentieel voor de succesvolle implementatie.

- Ondersteuning van patiënten: Het betrekken van patiënten en hen informeren over het belang van hartrevalidatie en hoe ze kunnen deelnemen, is cruciaal voor een succesvolle implementatie.

- Technologische hulpmiddelen: Technologische vooruitgang maakt het mogelijk om hartrevalidatie op afstand aan te bieden, wat de implementatie vergemakkelijkt, vooral in landelijke of afgelegen gebieden.

Samengevat is hartrevalidatie aanvaardbaar en haalbaar vanwege de klinische voordelen, de beschikbaarheid van programma's en de interdisciplinaire benadering. De implementatie ervan kan worden verbeterd door training, patiënteneducatie en technologische ondersteuning. Het is belangrijk om hartrevalidatie te promoten als een integraal onderdeel van de zorg voor patiënten met hart- en vaatziekten om hun gezondheid en kwaliteit van leven te verbeteren.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Coronairlijden

Uit de literatuur komt naar voren dat er een reductie van de mortaliteit is na het volgen van een hartrevalidatieprogramma. Hierin wordt geen onderscheid gemaakt tussen verschillende uitingen van coronairlijden. Elke patiënt met coronairlijden heeft dus een absolute indicatie voor het volgen van een hartrevalidatieprogramma. Bij acute diagnoses is de timing hiervan eenvoudig. Denk hierbij aan een acuut myocardinfarct of interventie zoals een PCI of CABG. Bij een chronische diagnose zoals stabiele angina pectoris is timing van verwijzing minder duidelijk en dient dit dus gaandeweg het ziektebeeld besproken te worden met de patiënt. Bij voorkeur vindt verwijzing plaats bij een patiënt die stabiel is ingesteld op medicatie, en die op dat moment gemotiveerd is om te werken aan een gezonde leefstijl.

Atriumfibrilleren

Uit de literatuur komt geen duidelijke evidence naar voren, dat alle patiënten met atriumfibrilleren baat hebben bij hartrevalidatie. Derhalve blijft deze diagnose een relatieve indicatie houden. Echter, er is wel bewijs dat leefstijlfactoren en het beïnvloeden hiervan een grote rol kunnen spelen in het ontstaan of onderhouden van atriumfibrilleren. Daarnaast is bekend dat het beïnvloeden van risicofactoren kan zorgen voor betere ritme-controle (Rienstra, 2018; Pathak, 2014). Hartrevalidatie dient dus met name overwogen te worden bij patiënten met atriumfibrilleren waarbij het vermoeden bestaat dat leefstijl gerelateerde factoren een belangrijke rol spelen in het veroorzaken of onderhouden van het atriumfibrilleren. Voorbeelden hiervan zijn: overgewicht, stress, alcoholgebruik en fysieke inspanning. Het hartrevalidatieprogramma dient in deze gevallen met name gericht te zijn op het beïnvloeden van deze factoren, zoals ook aanbevolen in de ESC-richtlijn atriumfibrilleren 2020.

Hartfalen

Uit de literatuur komt naar voren dat er op de korte termijn een positief effect lijkt te zijn in het verminderen van het aantal ziekenhuisopnames en een verbeterde kwaliteit van leven. Op de lange termijn kunnen we dit resultaat niet bevestigen vanwege het ontbreken van evidence met een hoge kwaliteit. Wel lijkt er een positief effect te zijn in het verminderen van het risico op MACE (Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events) op de lange termijn. Over mortaliteit kan op basis van de literatuur geen uitspraak gedaan worden. Belangrijk nog om te vermelden is dat er geen nieuwe systematische literatuuranalyse gedaan is naar het effect van hartrevalidatie op de fysieke capaciteit (ook wel inspanningscapaciteit) bij patiënten met hartfalen. In de vorige editie van deze richtlijn werd reeds een positief effect beschreven van hartrevalidatie op de inspanningscapaciteit. Dit is echter onderbouwd door veelal gedateerde literatuur. Desalniettemin achtte de werkgroep het niet nodig hier een systematisch literatuuronderzoek naar te verrichten. Een recente meta-analyse (met een mix van studies van voor en na publicatie van de vorige richtlijn) toonde een verbetering van de inspanningscapaciteit (Peak VO2) in 17/18 geïncludeerde studies, waarbij bij de enige studie met een negatief resultaat er een significant verschil ten nadele van de HR-groep in op baseline gezien werd (Bjarnason-Wehrens, 2020). Hiermee acht de werkgroep het positieve effect van hartrevalidatie op de inspanningscapaciteit voldoende bewezen.

Hartrevalidatie heeft voor patiënten met hartfalen dus met name invloed op zachtere uitkomstmaten zoals kwaliteit van leven, ziekenhuisopnames en inspanningscapaciteit. Voor patiënten met hartfalen die vaak ernstige beperkingen in de inspanningscapaciteit hebben en vaak opgenomen worden in het ziekenhuis, beschouwt de werkgroep dit als zeer belangrijke uitkomstmaten en is de werkgroep ook van mening dat voor deze patiënten een absolute indicatie voor hartrevalidatie geldt. Dit is in lijn met de Europese richtlijn Hartfalen (McDonagh, 2022).

Overige relatieve indicaties

Voor ziektebeelden of interventies met een relatieve indicatie voor hartrevalidatie (zie lijst hierboven) is de werkgroep van mening dat hartrevalidatie met name overwogen dient te worden als er sprake is van:

-

- Beweegangst;

- Ernstige beperking van het fysiek functioneren als gevolg van de hartaandoening die positief beïnvloed kan worden door een revalidatieprogramma;

- Leefstijlfactoren die het beloop van de ziekte negatief beïnvloeden;

- Als er een cardiochirurgische interventie heeft plaatsgevonden;

- Andere factoren die participatie binnen de samenleving verhinderen en waarbij het vermoeden bestaat dat deze positief beïnvloed kunnen worden door een revalidatieprogramma.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

This module describes which groups of patients are eligible for (parts of) cardiac rehabilitation. It also discusses contraindications for participating in a rehabilitation program. The role of the cardiologist as a gatekeeper for cardiac rehabilitation is also explained, as well as the various ways in which this role can be fulfilled.

Compared to the previous guideline recommendations, the working group assessed for which indications new research might change the recommendations. Therefore, atrial fibrillation and heart failure were selected for a literature search.

In addition, the view has changed somewhat for patients with various forms of coronary artery disease (CAD) in recent years. In the previous guideline, an absolute indication is given for different manifestations of coronary artery disease (myocardial infact, unstable and stable angina pectoris). Internationally, coronary artery disease is often talked about as chronic coronary syndrome, which includes all its different manifestations. From a pathophysiological point of view, according to the working group (supported by the chronic coronary syndromes guideline of the ESC (Knuuti, 2020)), it is not useful to distinguish between different forms of coronary artery disease and the benefit of cardiac rehabilitation for these patients. The underlying disease (atherosclerosis) is the same in all patients. The working group has therefore chosen to search for evidence for cardiac rehabilitation in patients with coronary artery disease in general and to no longer distinguish between different manifestations of the disease.

Literature analysis

For the update of this module, three searches and literature analyses were performed focusing on patients with CAD, AF, or HF, respectively. The focus was on these three diagnosis groups because the assumption was that new literature could potentially change the recommendation.

1. Literature analysis of patients with CAD

2. Literature analysis of patients with AF

3. Literature analysis of patients with HF

Samenvatting literatuur

PICO 1 - CAD

Description of studies

Three systematic reviews were included. All three reviews included patients with CAD. The focus was slightly different for cardiac rehabilitation. Dibben (2021) studied exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation, Anderson (2017) patient education as part of CR and Richards (2017) a psychological intervention. Only trials with a minimum follow-up period of 13 months were included and described. In the table, a summary is given for each of the included reviews and included trials. See evidence table for more details.

|

Author, year |

Patients |

Intervention |

Outcomes (N studies) |

|

Dibben, 2021 |

Adult men and women who have had a MI, CABG or PCI, or have angina pectoris, or coronary artery disease.

|

Exercise-based CR

Defined as a supervised or unsupervised inpatient, outpatient, community- or home-based intervention which includes some form of exercise training that is applied to a cardiac patient population.

|

Hospital admissions (9 studies) MACE (21 studies) All-cause mortality (27 studies)

|

|

Anderson, 2017 |

Adults who had experienced a myocardial infarction (MI); who underwent revascularisation (coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery stenting); or who had angina pectoris or CHD defined by angiography.

|

Patient education as part of CR

Defined as: 1. instructional activities 2. delivered as an inpatient, or outpatient in a community-based intervention setting or programme 3. included some form of structured knowledge transfer about CHD and 4. delivered in a face-to-face format, in groups or on a one-to-one basis. |

Hospital admissions (2 studies) MACE (1 study) All-cause mortality (7 studies)

|

|

Richards, 2017 |

Adults of all ages with CHD, with or without clinical psychopathology, managed in either hospital or community settings.

|

A psychological intervention.

Common aims of treatments included:

|

Hospital admissions (2 studies) MACE (8 studies) All-cause mortality (10 studies) Psychosocial recovery (5 studies) |

MACE, Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events.

Results

- Quality of life

All three reviews were not able to perform a meta-analysis for the results of quality of life. Primarily this was because of the different outcomes and methods used to assess quality of life. Dibben (2021) reported: “There were not enough data reported across trials at medium- and long-term follow-up for meta-analysis to be performed.” Anderson (2017) stated: “The wide variation in HRQoL outcomes and methods of reporting meant we were unable to meta-analyse results. Richards (2017) stated: “Direct comparisons between studies were difficult due to the different types of measures used to assess HRQoL.”

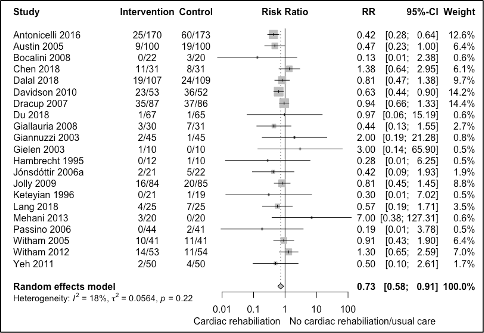

- Hospital admissions

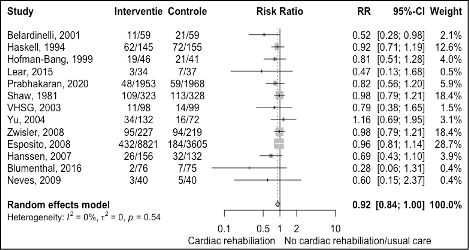

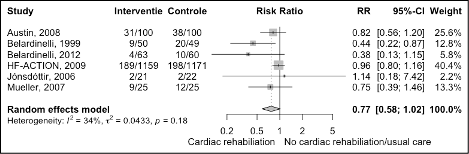

The results are shown in figure 1. The pooled effect was a risk ratio of 0.92 (95%CI 0.84 to 1.00) meaning the risk of a hospital admission was potentially similar with cardiac rehabilitation compared with standard care among patients with CAD.

Figure 1 Meta-analyse of outcome hospitalization for cardiac rehabilitation versus usual care in patients with CAD

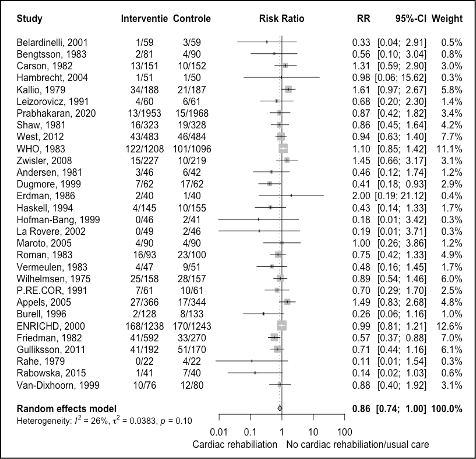

- MACE (Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events)

The results are shown in figure 2. The pooled effect was a risk ratio of 0.86 (95%CI 0.74 to 1.00) meaning the risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event was potentially reduced with cardiac rehabilitation compared with standard care among patients with CAD. The absolute risk difference was -1.27% (95%CI -2.41% to -0.13%) at follow-up > 12 months. This absolute risk difference was a clinically relevant effect as it is more than -0.5% at one year follow-up.

Figure 2 Meta-analyse of outcome MACE for cardiac rehabilitation versus usual care in patients with CAD

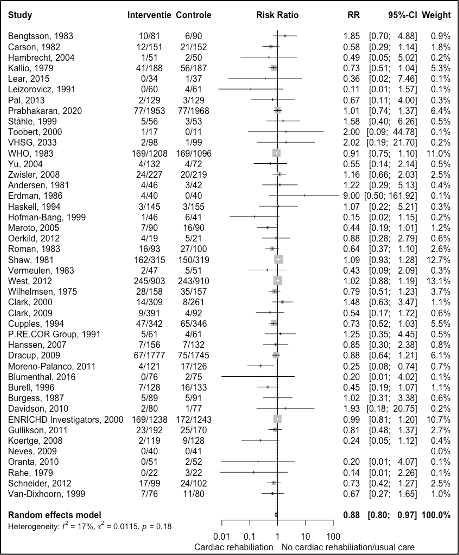

- All-cause mortality

The results are shown in figure 3. The pooled effect was a risk ratio of 0.88 (95%CI 0.80 to 0.97) meaning the risk of mortality was reduced with cardiac rehabilitation compared with standard care among patients with CAD. The corresponding absolute risk difference was -1.12% (95%CI -1.89% to -0.35%) at follow-up > 12 months. This absolute risk difference was a clinically relevant effect as it is more than -0.1% at one year follow-up.

Figure 3 Meta-analyse of outcome all-cause mortality for cardiac rehabilitation versus usual care in patients with CAD

- Psychosocial recovery

Only the review by Richards (2017) assessed the outcome psychosocial recovery. The authors of this review reported data on depression symptoms and anxiety levels.

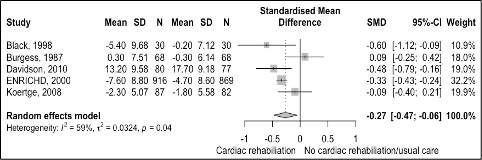

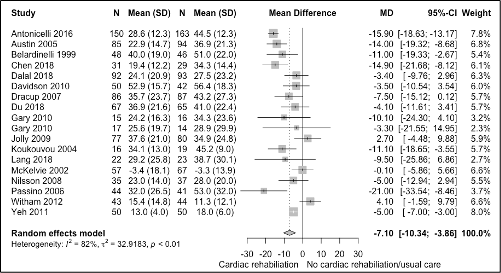

Depression symptoms

Five studies with a follow-up of > 12 months were included. The result of the meta-analysis is shown in Figure 4. After cardiac rehabilitation, there was a reduction in symptoms of depression compared with usual care (SMD -0.27 95%CI -0.47 to -0.06). The overall effect was a small benefit for cardiac rehabilitation.

Figure 4 Meta-analyse of outcome depression symptoms for cardiac rehabilitation versus usual care in patients with CAD

Anxiety levels

Two studies reported on anxiety with a follow-up of > 12 months. Results were not pooled. One study (Burgess, 1987; SMD 0.05 95%CI -0.29 to 0.38) indicated no effect of cardiac rehabilitation on anxiety levels, while the other study showed a decrease in anxiety levels for cardiac rehabilitation (Davidson, 2010; SMD -0.34 95%CI -0.66 to -0.03).

Level of evidence of the literature

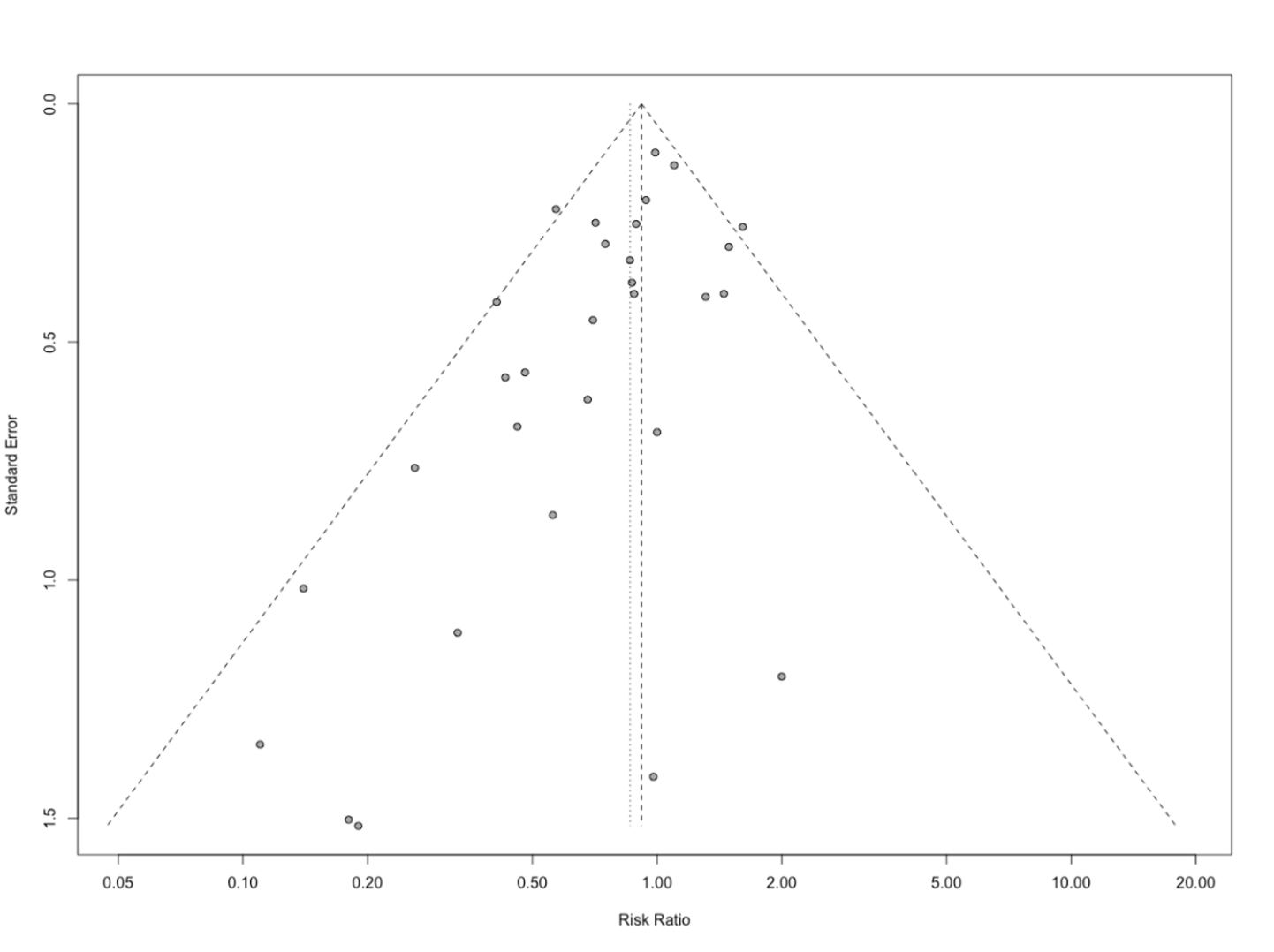

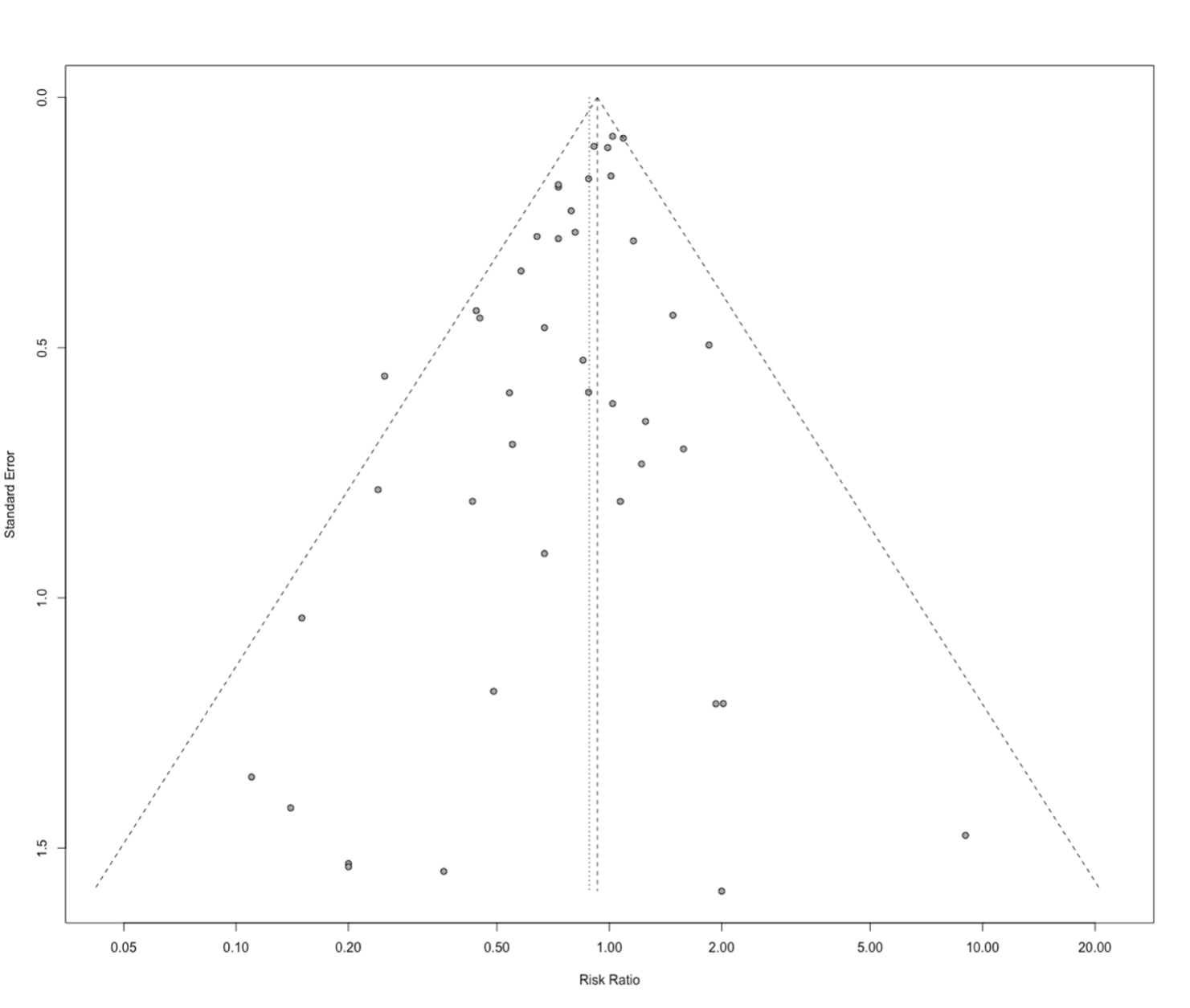

Hospitalizations: The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of publication bias (see appendix for funnel plot; small and middle-sized studies with a potential increased risk of hospitalizations are missing).

MACE: The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels; one level because of imprecision (one clinically important boundary is crossed) and one level because of publication bias (see appendix for funnel plot; small and middle-sized studies with a potential increased risk are missing).

All-cause mortality: The level of evidence was not downgraded. Ten trials had potential high risk of bias. The sensitivity analysis excluded these trials with potential high risk of bias, did not change the pooled estimate (RR 0.86 95%CI 0.76 to 0.97). Therefore, the level of evidence was not downgraded for risk of bias. We also found no evidence for publication bias (see appendix for funnel plot).

Psychosocial recovery (depression symptoms): The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of imprecision (boundary of a small effect was crossed by confidence interval); number of studies was too few to make a funnel plot.

Conclusions

Quality of life

|

- GRADE |

No conclusion can be drawn on the effect of cardiac rehabilitation in patients with CAD as the data were too different to perform a meta-analysis.

Source: Dibben, 2021; Anderson, 2017; Richards, 2017 |

Hospitalization

|

Moderate GRADE |

Cardiac rehabilitation likely results in little to no difference in the risk of hospitalization when compared with usual care in patients with CAD.

Source: Dibben, 2021; Anderson, 2017; Richards, 2017 |

MACE (Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events)

|

Low GRADE |

Cardiac rehabilitation may reduce the risk of MACE when compared with usual care in patients with CAD.

Source: Dibben, 2021; Anderson, 2017; Richards, 2017 |

All-cause mortality

|

High GRADE |

Cardiac rehabilitation reduces all-cause mortality when compared with usual care in patients with CAD.

Source: Dibben, 2021; Anderson, 2017; Richards, 2017 |

Depression symptoms

|

Moderate GRADE |

Cardiac rehabilitation probably results in a slight reduction in depressive symptoms when compared with usual care in patients with CAD.

Source: Richards, 2017 |

PICO 2 - AF

Description of studies

Risom (2020) performed a randomized controlled trial (CopenHeartRFA) to assess the effect of cardiac rehabilitation on hospitalization, quality of life and psychosocial recovery for patients treated for AF. A total of 210 patients from two Danish university hospitals treated with ablation for AF were included.

Patients were randomized either to cardiac rehabilitation (n=105) plus usual care or usual care alone (n=105). Cardiac rehabilitation consisted of a 12-week physical exercise program and psycho-educational consultations. The psychoeducational intervention consisted of education and information about AF which prepared the patients for expected symptoms and aimed to provide emotional support and improve coping skills and illness appraisal. The control group received usual care which was the standard medical follow-up for patients treated for AF. Follow-up was 24 months.

Patients receiving cardiac rehabilitation were 60 years of age (SD 9), and patients receiving usual care were 59 years (SD 12). The majority in both groups was male (74% and 77%, respectively).

De With (2019) performed a multicenter, randomized, open-label trial (RACE3) and investigated the effect of cardiac rehabilitation on quality of life in patients with early persistent AF and HF. Participants were recruited between May 2009 and November 2015 from 14 centers in the Netherlands and 3 in the UK. Patients were randomized to either targeted (n=114) or conventional therapy (n=116). The targeted group received on top of conditional therapy four additional therapies: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; statins; angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and/or receptor blockers; and cardiac rehabilitation. Cardiac rehabilitation consisted of physical activity, dietary restrictions, and counselling.

In total 230 patients with a mean age of 65 (SD 9) were included. 87% of the patients were male. Follow-up duration was 1 year.

Results

- Hospitalization (crucial)

Risom (2020) reported on hospitalization among patients with AF. During twenty-four months of follow-up (71 out of 105) 68% in the intervention group vs (60 out of 105) 57% in the control group were hospitalized. The authors did not rapport an effect estimate. Using the numbers provided in the article, the risk ratio was calculated. The risk of hospitalization is potentially 18% increased among patients receiving cardiac rehabilitation compared with usual care (RR 1.18 95%CI 0.96 to 1.46).

- Quality of life (crucial)

Risom (2020) and de With (2019) reported on quality of life using the SF-36 questionnaire. The results of the eight domains of the SF-36 are reported separately. Results could not be pooled because Risom (2020) did not report any measure of variation such as a SD or SE.

2.1 Bodily pain

Risom (2020) reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 77.97 at baseline and 85.69 after 24 months. In the usual care group, the mean score at baseline was 73.96 and after 24 months 85.84. The p-value between-group change was 0.12.

De With reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 80 (SD 22) at baseline and 85 (SD 21) after 12 months. In the usual care group, the mean score at baseline was 77 (SD 25) and after 12 months 81 (SD 22). The p-value between-group change was 0.83.

2.2 General health perception

Risom (2020) reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 65.34 at baseline and 62.64 after 24 months. In the usual care group, the mean baseline score at baseline was 65.85 and after 24 months 66.9. The p-value between-group change was 0.63.

De With reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 59 (SD 19) at baseline and 68 (SD 19) after 12 months, p-value <0.001. In the usual care group, the mean score at baseline was 59 (SD 19) and after 12 months 59 (SD 21), p-value 0.866. The p-value between-group change was <0.001.

2.3 Mental health index

Risom (2020) reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 69.05 at baseline and 78.82 after 24 months. In the usual care group, the mean baseline score at baseline was 70.38 and after 24 months 81.41. The p-value between-group change was 0.28.

De With reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 79 (SD 16) at baseline and 83 (SD 14) after 12 months, p-value 0.001. In the usual care group, the mean score at baseline was 77 (SD 15) and after 12 months 80 (SD 15), p-value 0.027. The p-value between-group change was 0.405.

2.4 Physical functioning index

Risom (2020) reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 81.40 at baseline and 86.61 after 24 months. In the usual care group, the mean baseline score at baseline was 80.45 and 86.95 after 24 months. The p-value between-group change was 0.95.

De With reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 67 (SD 23) at baseline and 79 (SD 21) after 12 months, p-value <0.001. In the usual care group, the mean score at baseline was 69 (SD 25) and after 12 months 75 (SD 23), p-value 0.024. The p-value between-group change was 0.007.

2.5 Role emotional index

Risom (2020) reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 67.51 at baseline and 80.17 after 24 months. In the usual care group, the mean baseline score at baseline was 58.21 and after 24 months 78.73. The p-value between-group change was 0.43.

De With reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 74 (SD 41) at baseline and 86 (SD 30) after 12 months, p-value 0.009. In the usual care group, the mean score at baseline was 77 (SD 38) and after 12 months 84 (SD 34), p-value 0.136. The p-value between-group change was 0.414.

2.6 Role physical index

Risom (2020) reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 44.38 at baseline and 74.22 after 24 months. In the usual care group, the mean baseline score at baseline was 49.88 and after 24 months 75.61. The p-value between-group change was 0.43.

De With reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 43 (SD 43) at baseline and 75 (SD 37) after 12 months, p-value <0.001. In the usual care group, the mean score at baseline was 51 (SD 45) and after 12 months 68 (SD 41), p-value 0.001. The p-value between-group change was 0.018.

2.7 Social functioning index

Risom (2020) reported on in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 75.39 at baseline and 88.89 after 24 months. In the usual care group, the mean baseline score at baseline was 77.87 and after 24 months 89.13. The p-value between-group change was 0.81.

De With reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 77 (SD 24) at baseline and 86 (SD 19) after 12 months, p-value 0.001. In the usual care group, the mean score at baseline was 81 (SD 20) and after 12 months 86 (SD 17), p-value 0.026. The p-value between-group change was 0.277.

2.8 Vitality index

Risom (2020) reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 50.73 at baseline and 66.37 after 24 months. In the usual care group, the mean baseline score at baseline was 50.51 and after 24 months 66.36. The p-value between-group change was 0.85.

De With reported in the cardiac rehabilitation group a mean score of 58 (SD 22) at baseline and 66 (SD 20) after 12 months, p-value <0.001. In the usual care group, the mean score at baseline was 60 (SD 21) and after 12 months 66 (SD 19), p-value 0.001. The p-value between-group change was 0.361.

- Psychosocial recovery (important):

Risom (2020) reported the HADS-A and HADS-D scores. A subscale score > 8 denotes anxiety or depression.

3.1 HADS-A

In the cardiac rehabilitation group, the mean HADS-A score was 5.81 points at baseline and 3.90 points after 24 months. HADS-A improved with 2.91 points. In the usual care group, the mean HADS-A score was 4.47 points at baseline and 4.73 after 24 months. HADS-A worsened with 0.26 points. Overall, HADS-A showed a improvement over time in favor of the cardiac rehabilitation group, p-value 0.004.

3.2 HADS-D

In the cardiac rehabilitation group, the mean HADS-D score was 3.25 points at baseline and 2.57 points after 24 months. HADS-D improved with 0.68 points. In the usual care group, the mean HADS-D score was 3.31 points at baseline and 2.86 after 24 months. HADS-D improved with 0.45 points. No difference over time was observed between the cardiac rehabilitation group and the usual care group, p-value 0.28.

- Mortality

Only Risom (2020) reported data on mortality. During the follow-up period, 1 patient died in each group. No conclusion will be drawn based on these few numbers.

- MACE (Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events) and cardiovascular disease

De With (2019) and Risom (2020) did not report any data on these outcome measures.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hospitalization was downgraded by two levels because confidence interval crossed a boundary of clinical important difference (imprecision). Although participants were not blinded, the outcome assessors were blinded. Data on hospitalization also came from a registry. Therefore, the level of evidence was not downgraded for risk of bias.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life (per domain) was not graded, because of baseline difference between intervention and control group and lack of measures of variation in one study.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure psychosocial recovery was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, participants were not blinded) and optimal information size not met (imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was not graded because of too few numbers (one death in each group).

None of the included studies reported data on the effect of cardiac rehabilitation in patients with AF on the outcome measures MACE, and cardiovascular disease.

Conclusions

Hospitalization

|

Low GRADE |

Cardiac rehabilitation compared with usual care results in little to no difference on hospitalization in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Sources: Risom, 2020 |

Quality of life

|

- GRADE |

Because of baseline differences between intervention and control groups and lack of measures of variation in one study, no conclusion could be drawn on the effect of cardiac rehabilitation compared with usual care in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Sources: Risom, 2020; de With, 2019 |

Psychosocial recovery

|

Low GRADE |

Cardiac rehabilitation compared with usual care might improve anxiety in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Sources: Risom, 2020 |

|

Low GRADE |

Cardiac rehabilitation in comparison with usual care results in little to no difference on depression in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Sources: Risom, 2020 |

Mortality

|

- GRADE |

Because of too few numbers, no conclusion could be drawn on the effect of cardiac rehabilitation compared with usual care in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Sources: Risom, 2020 |

MACE (Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events)and cardiovascular disease

|

- GRADE |

None of the included studies reported data on the effect of cardiac rehabilitation on the outcome measures MACE or cardiovascular disease in patients with atrial fibrillation. |

PICO 3 - HF

Description of studies

Seven randomized controlled trials (Austin, 2008; Belardinelli, 1999; Belardinelli, 2012; Cowie, 2011; HF-ACTION, 2009; Jónsdóttir, 2006; Mueller, 2007) researched the effect of exercise training compared with usual care in patients with heart failure. Number of included participants ranged from 31 to 2331. Most participants were male (at least 64%) and with an average age of at least 53 years. The follow-up time in all trials was 2 years or more. See the evidence table for more details.

Results

- Quality of life

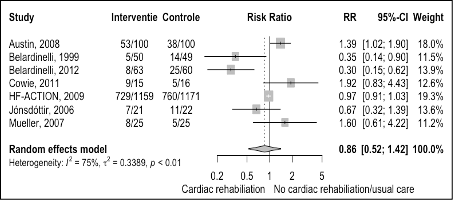

Short-term follow-up (6 to 12 months)

A total of 17 trials (one trial (Gary, 2010) with two comparisons) reported data on quality of life. All trials used the MLHF-HRQL questionnaire. The results of the pooled analysis are shown in figure 1. Overall, quality of life improved with cardiac rehabilitation compared with usual care for patients with heart failure (MD -7.10 (95%CI -10.34 to -3.86). However, the confidence interval crossed the boundary of a minimal clinically important difference of -5.

Figure 1 Meta-analysis of the short-term effect of cardiac rehabilitation on quality of life in heart failure patients

Long-term follow-up (>12 months)

Three trials (Austin, 2008; Belardinelli, 1999; Belardinelli, 2012) reported data on quality of life. All three used the MLHF-HRQL questionnaire. However, it was not possible to pool the results. One trial reported an average score for the groups, but it was unclear at which moment during follow-up these results were measured. The two other trials reported either no difference in score or a decrease in total score in favor of the intervention group. Therefore, no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of cardiac rehabilitation in patients with heart failure.

- Hospital admissions

Short-term follow-up (6 to 12 months)

The pooled results are shown in figure 2. The risk of hospital admissions is 27% lower with cardiac rehabilitation compared with usual care in patients with heart failure (Figure 2, RR 0.58 95%CI 0.58 to 0.92). This effect is clinically relevant.

Figure 2 Meta-analysis of the short-term effect of cardiac rehabilitation on hospitalizations in heart failure patients

Long-term follow-up (>12 months)

All seven trials reported data on hospital admissions. All but one reported the number of participants who had at least on admission during follow-up. The pooled results are shown in figure 3. The risk of hospital admissions is 14% lower with cardiac rehabilitation compared with usual care in patients with heart failure (Figure 1, RR 0.86 95%CI 0.52 to 1.42). This effect is not clinically relevant according to the minimally important difference.

Figure 3 Meta-analysis of the effect of cardiac rehabilitation on hospital admissions in heart failure patients

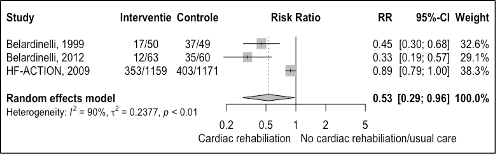

- MACE (Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events)

Long-term follow-up (>12 months)

Only three trial reported data on MACE. The results are shown in figure 4. The risk of cardiovascular disease is 47% lower with cardiac rehabilitation compared with usual care in patients with heart failure (RR 0.53 95%CI 0.29 to 0.96). The absolute risk difference was -27.02% (95%CI -51.94% to -2.10%). This absolute risk difference was a clinically relevant effect as it is more than -1.0% at two-year follow-up.

Figure 4 Meta-analysis of the effect of cardiac rehabilitation on cardiovascular diseases in heart failure patients

- All-cause mortality

Long-term follow-up (>12 months)

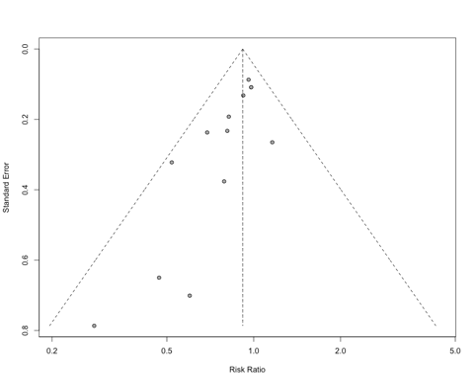

All but one trial reported data on mortality. Figure 5 shows the results of a meta-analysis. The risk of dying is decreased with 23% in patients who received cardiac rehabilitation compared with usual care (RR 0.77 95%CI 0.58 to 1.02). The absolute risk difference was -6.45% (95%CI -13.23 to 0.34). This absolute risk difference was a clinically relevant effect as it is more than -1.0% at two-year follow-up.

Figure 5 Meta-analysis of the effect of cardiac rehabilitation on mortality in heart failure patients

- Psychosocial recovery

None of the included trials reported any results on psychosocial recovery after cardiac rehabilitation.

Level of evidence of the literature

Quality of life:

- The level of evidence for short- term (Follow-up 6 to 12 months) was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias; majority of trials reported no information on randomization or allocation concealment) and inconsistency. We did not downgrade for imprecision as the broad confidence interval is linked to inconsistency.

- The level of evidence for long-term (Follow-up >12 months) was not graded because the results could not be pooled.

Hospital admissions:

- The level of evidence for short-term (Follow-up 6 to 12 months) was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias; majority of trials reported no information on randomization or allocation concealment) and imprecision (boundary of clinical important difference was crossed ).

- The level of evidence for long-term (Follow-up >12 months) was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, one trial had issue with adherence to therapy. Five trials had some concerns due to no information on randomization or allocation concealment. One trial (Cowie, 2011) had high risk of bias because of selective outcome reporting); conflicting results (inconsistency); imprecision (confidence interval includes both boundaries of a minimally important difference).

MACE: The level of evidence for long-term (Follow-up >12 months) was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias; two trials reported no information on randomization or allocation concealment).

All-cause mortality: The level of evidence for long-term (Follow-up >12 months) was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, one trial had issue with adherence to therapy and five trials had some concerns due to no information on randomization or allocation concealment); conflicting results (inconsistency); imprecision (confidence interval includes one boundary of minimally important difference).

Psychosocial recovery: The level of evidence was not graded as none of the included trials reported any data on this outcome.

Conclusions

Quality of life

|

Low GRADE

- GRADE |

Short-term (Follow-up 6 to 12 months) Cardiac rehabilitation may improve quality of life when compared with usual care in patients with heart failure.

Source; Long, 2019

Long-term (Follow-up >12 months) No conclusion was drawn regarding the effect of cardiac rehabilitation on quality of life when compared with usual care in patients with heart failure because of inability to pool the results.

Source: Austin, 2008; Belardinelli, 1999; Belardinelli, 2012 |

Hospital admissions

|

Low GRADE

Very low GRADE |

Short-term (Follow-up 6 to 12 months) Cardiac rehabilitation may reduce the risk of hospital admissions when compared with usual care in patients with heart failure.

Source; Long, 2019

Long-term (Follow-up >12 months) The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of cardiac rehabilitation on hospital admissions when compared with usual care in patients with heart failure.

Source: Austin, 2008; Belardinelli, 1999; Belardinelli, 2012; Cowie, 2011; HF-ACTION, 2009; Jónsdóttir, 2006; Mueller, 2007 |

MACE (Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Long-term (Follow-up >12 months) Cardiac rehabilitation likely reduces the risk of MACE when compared with usual care in patients with heart failure.

Source: Belardinelli, 1999; Belardinelli, 2012; HF-ACTION, 2009 |

All-cause mortality

|

Very low GRADE |

Long-term (Follow-up >12 months) The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of cardiac rehabilitation on all-cause mortality when compared with usual care in patients with heart failure.

Source: Austin, 2008; Belardinelli, 1999; Belardinelli, 2012; HF-ACTION, 2009; Jónsdóttir, 2006; Mueller, 2007 |

Psychosocial recovery

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of cardiac rehabilitation on psychosocial recovery when compared with usual care in patients with heart failure, as none of the included trials reported any data on this outcome. |

Zoeken en selecteren

Search and select

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the favourable and unfavourable effects of cardiac rehabilitation compared with standard care for patients with coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation or heart failure?

Table 1 PICO

|

Patients |

With:

|

|

Intervention |

Cardiac Rehabilitation |

|

Control |

Standard care |

|

Outcomes |

MACE (Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events), cardiovascular disease, mortality, quality of life, hospitalizations, psychosocial recovery |

|

Other selection criteria |

Study design: systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials Minimum follow-up: one year (preferably 5 for mortality) |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered quality of life, and hospitalizations as critical outcome measures for decision making; and MACE, cardiovascular disease, mortality, and psychosocial recovery as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measure MACE listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Minimal clinically important differences

Hospitalization: The working group defined a relative risk of 0.8 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

MACE: The working group defined absolute risk reduction of > 5% over ten years as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference, which corresponds with a reduction of > 0.5% per year.

All-cause mortality: The working group defined absolute risk reduction of > 1% over ten years as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference, which corresponds with a reduction of > 0.1% per year.

Psychosocial recovery: The working group defined standardized mean differences of 0.2 to 0.5 as small, 0.5 to 0.8 as medium and > 0.8 as large.

Search and select (Methods) – PICO1

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 20 April 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 617 hits. For the selection criteria, see the PICO table. 33 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 31 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included (systematic reviews: Dibben, 2021 and Anderson, 2017). One additional review (Richards, 2017) was included from the reference list of a potential study. Of the three included reviews, two reviews (Anderson, 2017; Richards, 2017) performed a search more than two years ago. Our search found no RCTs after search date of these reviews.

Results – PICO1

Three studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables of the included systematic reviews.

Search and select (Methods) - PICO 2

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 20 October 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 211 hits. For the selection criteria, see the PICO table. 6 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 4 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included (CopenHeartRFA trial (Risom, 2020) and RAE3 trial (De With, 2019)).

Results - PICO 2

Two studies concerning AF were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Search and select (Methods) - PICO 3

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 20 April 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 1124 hits. For the selection criteria, see the PICO table. 16 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 15 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and one study was included, a systematic review by Long (2019). This review included 44 trials comparing exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation with no exercise control in patients with heart failure. No other relevant trials were published after the search date by Long (2019). Authors performed analyses separately for trails with a follow-up of 6 to 12 months and trials with a follow-up of at least 13 months. In line with the literature analysis for PICO1 and PICO2, these analyses separated by follow-up were also adopted for this clinical question.

Results - PICO 3

Seven studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Anderson L, Brown JP, Clark AM, Dalal H, Rossau HK, Bridges C, Taylor RS. Patient education in the management of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jun 28;6(6):CD008895. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008895.pub3. PMID: 28658719; PMCID: PMC6481392.

- Austin J, Williams WR, Ross L, Hutchison S. Five-year follow-up findings from a randomized controlled trial of cardiac rehabilitation for heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008 Apr;15(2):162-7.

- Belardinelli R, Georgiou D, Cianci G, Purcaro A. Randomized, controlled trial of long-term moderate exercise training in chronic heart failure: effects on functional capacity, quality of life, and clinical outcome. Circulation. 1999 Mar 9;99(9):1173-82.

- Belardinelli R, Georgiou D, Cianci G, Purcaro A. 10-year exercise training in chronic heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 Oct 16;60(16):1521-8.

- Bjarnason-Wehrens B, Nebel R, Jensen K, Hackbusch M, Grilli M, Gielen S, Schwaab B, Rauch B; German Society of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (DGPR). Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: The Cardiac Rehabilitation Outcome Study in Heart Failure (CROS-HF): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020 Jun;27(9):929-952.

- Cowie A, Thow MK, Granat MH, Mitchell SL. A comparison of home and hospital-based exercise training in heart failure: immediate and long-term effects upon physical activity level. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2011 Apr;18(2):158-66.

- De With RR, Rienstra M, Smit MD, Weijs B, Zwartkruis VW, Hobbelt AH, Alings M, Tijssen JGP, Brügemann J, Geelhoed B, Hillege HL, Tukkie R, Hemels ME, Tieleman RG, Ranchor AV, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Crijns HJGM, Van Gelder IC. Targeted therapy of underlying conditions improves quality of life in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: results of the RACE 3 study. Europace. 2019 Apr 1;21(4):563-571.

- Dibben G, Faulkner J, Oldridge N, Rees K, Thompson DR, Zwisler AD, Taylor RS. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Nov 6;11(11):CD001800. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001800.pub4. PMID: 34741536; PMCID: PMC8571912.

- Eijsvogels TMH, Maessen MFH, Bakker EA, Meindersma EP, van Gorp N, Pijnenburg N, Thompson PD, Hopman MTE. Association of Cardiac Rehabilitation With All-Cause Mortality Among Patients With Cardiovascular Disease in the Netherlands. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Jul 1;3(7):e2011686.

- Jolliffe JA, Rees K, Taylor RS, Thompson D, Oldridge N, Ebrahim S. Exercise-based rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1):CD001800.

- Jónsdóttir S, Andersen KK, Sigurosson AF, Sigurosson SB. The effect of physical training in chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006 Jan;8(1):97-101.

- Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, Capodanno D, Barbato E, Funck-Brentano C, Prescott E, Storey RF, Deaton C, Cuisset T, Agewall S, Dickstein K, Edvardsen T, Escaned J, Gersh BJ, Svitil P, Gilard M, Hasdai D, Hatala R, Mahfoud F, Masip J, Muneretto C, Valgimigli M, Achenbach S, Bax JJ; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 14;41(3):407-477.

- Long L, Mordi IR, Bridges C, Sagar VA, Davies EJ, Coats AJ, Dalal H, Rees K, Singh SJ, Taylor RS. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jan 29;1(1):CD003331.

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Crespo-Leiro MG, Farmakis D, Gilard M, Heymans S, Hoes AW, Jaarsma T, Jankowska EA, Lainscak M, Lam CSP, Lyon AR, McMurray JJV, Mebazaa A, Mindham R, Muneretto C, Piepoli MF, Price S, Rosano GMC, Ruschitzka F, Skibelund AK; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2022 Jun;75(6):523

- Mueller L, Myers J, Kottman W, Oswald U, Boesch C, Arbrol N, Dubach P. Exercise capacity, physical activity patterns and outcomes six years after cardiac rehabilitation in patients with heart failure. Clin Rehabil. 2007 Oct;21(10):923-31.

- O'Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, Keteyian SJ, Cooper LS, Ellis SJ, Leifer ES, Kraus WE, Kitzman DW, Blumenthal JA, Rendall DS, Miller NH, Fleg JL, Schulman KA, McKelvie RS, Zannad F, Piña IL; HF-ACTION Investigators. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009 Apr 8;301(14):1439-50.

- Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Lau DH, Mehta AB, Mahajan R, Twomey D, Alasady M, Hanley L, Antic NA, McEvoy RD, Kalman JM, Abhayaratna WP, Sanders P. Aggressive risk factor reduction study for atrial fibrillation and implications for the outcome of ablation: the ARREST-AF cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Dec 2;64(21):2222-31.

- Rienstra M, Hobbelt AH, Alings M, Tijssen JGP, Smit MD, Brügemann J, Geelhoed B, Tieleman RG, Hillege HL, Tukkie R, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Crijns HJGM, Van Gelder IC; RACE 3 Investigators. Targeted therapy of underlying conditions improves sinus rhythm maintenance in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: results of the RACE 3 trial. Eur Heart J. 2018 Aug 21;39(32):2987-2996.

- Richards SH, Anderson L, Jenkinson CE, Whalley B, Rees K, Davies P, Bennett P, Liu Z, West R, Thompson DR, Taylor RS. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Apr 28;4(4):CD002902. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002902.pub4. PMID: 28452408; PMCID: PMC6478177.

- Risom SS, Zwisler AD, Sibilitz KL, Rasmussen TB, Taylor RS, Thygesen LC, Madsen TS, Svendsen JH, Berg SK. Cardiac Rehabilitation for Patients Treated for Atrial Fibrillation With Ablation Has Long-Term Effects: 12-and 24-Month Follow-up Results From the Randomized CopenHeartRFA Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020 Nov;101(11):1877-1886.

Evidence tabellen

PICO 1 - CAD

Evidence table for PICO1

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Dibben, 2021

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature searched up to June 2021

Only the results for a follow-up period of 13 months or more were described.

See Dibben, 2021 for details.

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: See Dibben, 2021 (56% were undertaken in Europe).

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: 59% were funded by not-for-profit organisations; 33% did not report funding sources; 1% was funded by the industry; 7% were funded by a combination of industry and not-for-profit organisations. |

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

heart valve surgery, with heart failure, atrial fibrillation or heart transplants, or implanted with either cardiac-resynchronisation therapy or implantable cardiovertor defibrillators.

75 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: See Dibben, 2021 for details.

|

Exercise-based CR is defined as a supervised or unsupervised inpatient, outpatient, community- or home-based intervention which includes some form of exercise training that is applied to a cardiac patient population. The intervention could be exercise training alone or exercise training in addition to psychosocial or educational interventions, or both (i.e. "comprehensive CR"). |

All CR interventions were compared to a 'no exercise' control, and both the intervention and control group received usual medical care. Usual care could include standard medical care, such as drug therapy, but without any form of structured exercise training or advice. |

End-point of follow-up: See Dibben, 2021 for details. Results were pooled at three follow-up timings: short-term (6 to 12 months); medium-term (> 12 to 36 months); and long-term (> 36 months).

Only the results of the medium-term and long-term were included.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? See Dibben, 2021 for details.

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as quality of life (crucial)

” There were not enough data reported across trials at medium- and long-term follow-up for meta-analysis to be performed.”

Outcome measure-2 Defined as hospital admissions (crucial)

Medium-term (> 12 to 36 months) I: 392/3017 C: 417/2978 Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 0.92 [95% CI 0.82 to 1.03] favoring exercise-based CR Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-3 Defined as MACE / cardiovascular disease. In the review defined as fatal or nonfatal MI.

Medium-term (> 12 to 36 months) I: 264/4830 C: 237/4735 Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.07 [95% CI 0.91 to 1.27] favoring usual care. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Long-term (> 36 months) I: 65/776 C: 102/784 Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 0.67 [95% CI 0.50 to 0.90] favoring Exercise-based CR. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-4 Defined as all-cause mortality.

Medium-term (> 12 to 36 months) I: 467/5611 C: 498/5462 Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 0.90 [95% CI 0.80 to 1.02] favoring exercise-based CR. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Long-term (> 36 months) I: 476/1902 C: 493/1926 Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 0.91 [95% CI 0.75 to 1.10] favoring exercise-based CR. Heterogeneity (I2): 35%

Outcome measure-5 Defined as psychosocial recovery.

Not reported for medium-term or long-term. |

Risk of bias (high, some concerns or low): Cochrane Risk of Bias tool See Dibben, 2021 for details.

|

|

Anderson, 2017

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs.

Literature search up to June, 2016

Only the results for a follow-up period of 13 months or more were described.

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: See Anderson, 2017 for details (Eleven studies out of 22 were undertaken in Europe)

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Eleven studies were funded by not-for-profit organisations; six studies did not report funding sources; one study was funded by the industry; four studies were funded by health insurance companies. |

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR: studies of education programmes which included participants who:

22 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: See Anderson, 2017 for details.

|

Patient education as part of CR

Defined as: 1. instructional activities organised in a systematic way involving personal direct contact between a health professional and CHD patients with or without significant others: e.g. spouse, family member; 2. delivered as an inpatient, or outpatient in a community-based intervention setting or programme; 3. included some form of structured knowledge transfer about CHD, its causes, treatments, or methods of secondary prevention; and 4. delivered in a face-to-face format, in groups or on a one-to-one basis. We also included alternative interactive methods of educational delivery such as 'telehealth' (telephone, e-mail, Internet and teleconference between educator and patient). |

Usual care |

End-point of follow-up: See Anderson, 2017 for details.

Only the results of a follow-up of at less 13 months were included.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? See Anderson, 2017 for details.

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as quality of life (crucial)

” The wide variation in HRQoL outcomes and methods of reporting meant we were unable to meta-analyse results.”

Outcome measure-2 Defined as hospital admissions (crucial)

Follow-up > 12 months, n/N Esposito, 2008 I: 432/8821 C: 184/3605 RR 0.96 [95%I 0.81 to 1.14] Hanssen, 2007 I: 26/156 C: 32/132 RR 0.69 [95%CI 0.43 to 1.09]

Results were not pooled as only two trials reported on hospitalizations with a follow-up of > 12 months.

Outcome measure-3 Defined as MACE / cardiovascular disease. In the review defined as fatal or non-fatal MI

Follow-up > 12 months, n/N P.RE.COR Group, 1991 I: 7/61 C: 10/61 RR 0.70 [95% CI 0.29 to 1.72]

Outcome measure-4 Defined as all-cause mortality.

Follow-up > 12 months I: 153/3157 C: 184/2855 Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 0.78 [95% CI 0.60 to 1.02] favoring education. Heterogeneity (I2): 19%

Outcome measure-5 Defined as psychosocial recovery.

Not reported. |

Risk of bias (high, some concerns or low): Cochrane Risk of Bias tool See Anderson, 2017 for details.

|

|

Richards, 2017

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to April, 2016

Only the results for a follow-up period of 13 months or more were described.

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: See Richards, 2017 for details (51% of studies were undertaken in Europe)

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Twelve studies did not report funding sources; seven received government research grants; six from charities; six rom a mix of charities and government funding; two a mix of private companies, government and charities; one university funded. |

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

35 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: See Richards, 2017 for details.

|

A psychological intervention.

Common aims of treatments included:

Common components of psychological treatments included:

|

Common form of comparator was either 'usual medical care' or a 'cardiac rehabilitation programme in addition to usual medical care'. |

End-point of follow-up: See Richards, 2017 for details.

Only the results of a follow-up of at less 13 months were included.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? See Richards, 2017 for details.

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as quality of life (crucial)

”Direct comparisons between studies were difficult due to the different types of measures used to assess HRQoL.”

Outcome measure-2 Defined as hospital admissions (crucial)

Follow-up > 12 months, n/N Blumenthal, 2016 I: 2/76 C: 7/75 RR 0.28 [95%I 0.06 to 1.31] Neves, 2009 I: 3/40 C: 5/40 RR 0.43 [95%CI 0.15 to 1.19]

Results were not pooled as only two trials reported on hospitalizations with a follow-up of > 12 months.

Outcome measure-3 Defined as MACE / cardiovascular disease. In the review defined as non-fatal MI.

Follow-up (> 12 months); only included relevant studies for these results I: 290/2655 C: 302/2302 Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 0.76 [95% CI 0.54 to 1.07] favoring Cardiac rehabilitation. Heterogeneity (I2): 59%

Outcome measure-4 Defined as all-cause mortality.

Follow-up (> 12 months); only included relevant studies for these results I: 232/2210 C: 270/2214 Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 0.77 [95% CI 0.59 to 1.01] favoring Cardiac rehabilitation. Heterogeneity (I2): 12%

Outcome measure-5 Defined as psychosocial recovery.

Depression Only relevant studies with follow-up > 12 months included (Black, 1998; Burgess, 1987; Davidson, 2010; Enrichd investigators, 2000; Koertge, 2008) Pooled effect (random effects model): SMD -0.27 (-0.47 to -0.06) favoring cardiac rehabilitation. Heterogeneity (I2): 59%

Anxiety Two studies reported on anxiety with a follow-up of > 12 months. Results were not pooled. Mean (SD), n Burgess, 1987 I: -0.5 (6.9), 68 C: -0.8 (0.2), 68 SMD 0.05 (-0.29 to 0.38) Davidson, 2010 I: 6.7 (4.3), 80 C: 8.4 (5.2), 77 SMD -0.34 (-0.66 to -0.03)

|

Risk of bias (high, some concerns or low): Cochrane Risk of Bias tool See Richards, 2017 for details.

|

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Deka P, Pathak D, Klompstra L, Sempere-Rubio N, Querol-Giner F, Marques-Sule E. High-Intensity Interval and Resistance Training Improve Health Outcomes in Older Adults With Coronary Disease. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2022;23(1):60-5. |

Follow-up too short (8 weeks)

|

|

Bagheri H, Shakeri S, Nazari AM, Goli S, Khajeh M, Mardani A, et al. Effectiveness of nurse-led counselling and education on self-efficacy of patients with acute coronary syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Nursing open. 2022;9(1):775-84. |

Follow-up too short (1 month) |

|

Shi Y, Lan J. Effect of stress management training in cardiac rehabilitation among coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reviews in cardiovascular medicine. 2021;22(4):1491-501. |

SR included trials with CR as control group. |

|

Mustansar A, Noor R, Mahmood S, Yaqoob T, Latif W, Laique T. Outcome of cardiac rehabilitation in improving quality of life among women having IHD: A randomized controlled trail. Pakistan Journal of Medical and Health Sciences. 2021;15(1):488-90. |

Unclear if participants were randomized; follow-up too short (6 months) |

|

Mansilla-Chacón M, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Martos-Cabrera MB, Albendín-García L, Romero-Béjar JL, Cañadas-De La Fuente GA, et al. Effects of supervised cardiac rehabilitation programmes on quality of life among myocardial infarction patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2021;8(12). |

SR; majority of included trials had a too short follow-up

|

|

Kim C, Choi I, Cho S, Kim AR, Kim W, Jee S. Do Cardiac Rehabilitation Affect Clinical Prognoses Such as Recurrence, Readmission, Revascularization, and Mortality After AMI?: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Annals of rehabilitation medicine. 2021;45(1):57-70. |

Only 2 RCT were included, specific population of acute MI.

|

|

Khan Z, Musa K, Abumedian M, Ibekwe M. Prevalence of Depression in Patients With Post-Acute Coronary Syndrome and the Role of Cardiac Rehabilitation in Reducing the Risk of Depression: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2021;13(12):e20851. |

Unclear which studies were included

|

|

Hu Y, Li L, Wang T, Liu Y, Zhan X, Han S, et al. Comparison of cardiac rehabilitation (exercise + education), exercise only, and usual care for patients with coronary artery disease: A non-randomized retrospective analysis. Pharmacology Research and Perspectives. 2021;9(1). |

Not a RCT |

|

Cojocariu SA, Maștaleru A, Sascău RA, Stătescu C, Mitu F, Cojocaru E, et al. Relationships between psychoeducational rehabilitation and health outcomes—a systematic review focused on acute coronary syndrome. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021;11(6). |

SR on psycho-education interventions; Cochrane review available with a meta-analysis of results. |

|

Prabhakaran D, Chandrasekaran AM, Singh K, Mohan B, Chattopadhyay K, Chadha DS, et al. Yoga-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation After Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Randomized Trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2020;75(13):1551-61. |

Trial included in SR from Dibben |

|

McGregor G, Powell R, Kimani P, Underwood M. Does contemporary exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation improve quality of life for people with coronary artery disease? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open. 2020;10(6):e036089. |

SR into CR versus no CR with a focus on the outcome QoL (selection of included Cochrane review). |

|

Lee J, Lee R, Stone AJ. Combined Aerobic and Resistance Training for Peak Oxygen Uptake, Muscle Strength, and Hypertrophy After Coronary Artery Disease: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of cardiovascular translational research. 2020;13(4):601-11. |

Outcomes not of interest |

|

Candelaria D, Randall S, Ladak L, Gallagher R. Health-related quality of life and exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in contemporary acute coronary syndrome patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Quality of Life Research. 2020;29(3):579-92. |

SR into CR versus no CR with a focus on the outcome QoL (selection of included Cochrane review). |

|

Campo G, Tonet E, Chiaranda G, Sella G, Maietti E, Bugani G, et al. Exercise intervention improves quality of life in older adults after myocardial infarction: randomised clinical trial. Heart. 2020;106(21):1658-64. |

Education on lifestyle, etc. as controle group |

|

Bubnova MG, Aronov DM. Physical rehabilitation after acute myocardial infarction: Focus on body weight. Russian Journal of Cardiology. 2020;25(5):15-23. |

Included in Cochrane review Dibben

|

|

Avila A, Claes J, Buys R, Azzawi M, Vanhees L, Cornelissen V. Home-based exercise with telemonitoring guidance in patients with coronary artery disease: Does it improve long-term physical fitness? European journal of preventive cardiology. 2020;27(4):367-77 |

Participants already received CR phase II; randomisation to CR level III

|

|

Zheng X, Zheng Y, Ma J, Zhang M, Zhang Y, Liu X, et al. Effect of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation on anxiety and depression in patients with myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart and Lung. 2019;48(1):1-7. |

SR of trials with a follow-up of less than 1 year. |

|

Hegewald J, Ewegewitz U, Euler U, Van Dijk JL, Adams J, Fishta A, et al. Interventions to support return to work for people with coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019;2019(3). |

Cochrane review with focus on work-related interventions. Possible trials were all included in review by Dibben, 2021. |

|

Rauch B, Davos CH, Doherty P, Saure D, Metzendorf M-I, Salzwedel A, et al. The prognostic effect of cardiac rehabilitation in the era of acute revascularisation and statin therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized studies - The Cardiac Rehabilitation Outcome Study (CROS). European journal of preventive cardiology. 2016;23(18):1914-39. |

SR with similar inclusion criteria to Dibben. |

|