Hoe herken je kwetsbaarheid bij patiënten van ≥70 jaar in de preoperatieve setting?

Uitgangsvraag

Hoe herken je kwetsbaarheid bij patiënten van ≥70 jaar in de preoperatieve setting?

Aanbeveling

Verricht bij alle patiënten van ≥70 jaar die een indicatie hebben voor een operatie met verwachte opnameduur ≥2 dagen preoperatief een screening naar kwetsbaarheid.

Geschikte screeningsinstrumenten zijn de CFS, G8 (oncologische patiënten), GFI, EFS en de ISAR of ISAR-HP. Ook kan een (verkort) geriatrisch assessment gebruikt worden ter screening.

Verwijs bij afwijkende screening naar de geriater/internist-ouderengeneeskunde voor een Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment.

Overwegingen

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar verschillende screeningsinstrumenten die preoperatief worden ingezet om de mate van kwetsbaarheid te schatten bij oudere patiënten. De resultaten laten klinisch relevante verschillen van vergelijkbare grootte in voor de patiënt relevante uitkomstmaten zien, die in onderstaande paragrafen beschreven worden.

Kwetsbaarheid screening in relatie tot postoperatieve complicaties

Kwetsbare ouderen lopen een 2- tot 4-maal verhoogd risico op postoperatieve complicaties, waarbij de grootste verschillen te zien waren bij ouderen die als kwetsbaar werden geclassificeerd door het gebruik van de Clinical Frailty Score (CFS), Edmonton Fail Scale (EFS) of de Geriatric 8 (G8). De CFS is in 9 studies onderzocht, zowel in de electieve als acute chirurgische setting. In de gepoolde analyse hebben patiënten die kwetsbaar zijn 2x zoveel kans op postoperatieve complicaties. Hierbij moet wel opgemerkt worden dat in de studies verschillende CFS afkappunten voor frailty worden gebruikt, variërend van een score van 3 of hoger tot een score van 7 of hoger. De EFS is in 4 studies onderzocht in electieve setting. In de gepoolde analyse hebben patiënten die kwetsbaar zijn 4x zoveel kans op postoperatieve complicaties. Ook hier verschilt het afkappunt voor frailty van 4 of hoger tot 7 of hoger. De G8 werd in 8 studies onderzocht, waarbij de gepoolde analyse laat zien dat patiënten die kwetsbaar zijn 3x zoveel kans hebben op postoperatieve complicaties. De bewijskracht van de literatuur t.a.v. de CFS, EFS en G8 is laag. De Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI) en VMS-vragen werden in respectievelijk 2 studies en 1 studie onderzocht, met lage tot zeer lage bewijskracht.

Kwetsbaarheid screening in relatie tot postoperatieve mortaliteit

De grootste verschillen in risico op postoperatieve mortaliteit waren te zien bij patiënten die geclassificeerd waren ten aanzien van hun kwetsbaarheid door CFS, EFS of de Identification of Seniors At Risk (ISAR) of ISAR-hospitalized patients (ISAR-HP). In de gepoolde analyses van de CFS studies geeft kwetsbaarheid een 2,5 keer hoger risico op postoperatieve sterfte. Voor mortaliteit was het bewijs over het algemeen van lage kwaliteit, behalve voor ISAR, waarvoor het bewijs redelijk van kwaliteit was (door het grote aantal geïncludeerde patiënten).

Kwetsbaarheid screening in relatie tot postoperatieve ontslagbestemming

Classificatie door ISAR en VMS liet de grootste verschillen zien ten aanzien van de ontslagbestemming. Kwetsbare patiënten konden minder vaak naar huis na ontslag. Het bewijs voor ISAR was van redelijke kwaliteit, voor de overige instrumenten van lage kwaliteit, en voor CFS van zeer lage kwaliteit (door de grote onzekerheid van de resultaten).

Kwetsbaarheid screening in relatie tot postoperatief fysiek functioneren.

Patiënten die als kwetsbaar werden geclassificeerd door CFS en ISAR lieten een lager niveau van fysiek functioneren zien. Het bewijs voor ISAR was redelijk van kwaliteit, voor CFS was de kwaliteit laag.

Kwetsbaarheid screening in relatie tot opnameduur

Ten aanzien van de opnameduur werd bewijs gevonden voor kwetsbaarheid geclassificeerd door EFS, G8 en ISAR-HP. De kwaliteit van het bewijs was laag.

Samenvattend lijkt kwetsbaarheid van ouderen een groter risico te geven op nadelige uitkomsten. De grootte van de risico’s verschilt tussen de verschillende screeningsinstrumenten, net als de kwaliteit van het bewijs. Het bewijs ten aanzien van het instrument ISAR heeft een redelijke kwaliteit; het verschil met het niveau van bewijs voor andere screeningsinstrumenten zit in het aantal deelnemende patiënten en daarmee een grotere precisie van de effectschattingen.

Internationale richtlijnen rondom screening op kwetsbaarheid in de preoperatieve setting

De internationale richtlijnen voor perioperatieve zorg bevelen aan om bij ouderen in de preoperatieve fase een screeningstool te gebruiken om kwetsbaarheid te identificeren, dit is gebaseerd op hoge kwaliteit bewijs (Engel et al., 2023). Ook wordt in internationale richtlijnen geadviseerd dat bij een afwijkende screening de patiënt verwezen wordt voor een CGA (review door Engel et al, 2023).

Twee internationale richtlijnen zijn verschenen nadien en niet meer meegenomen in bovenstaande review. Dit betreft:

1. De ‘Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Evaluation and Management of Frailty Among Older Adults Undergoing Colorectal Surgery’ (Saur et al., 2022), van de American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons beveelt aan dat ouderen preoperatief gescreend moet worden op kwetsbaarheid (grade A, strong recommendation, high-quality evidence). De richtlijn noemt als mogelijke screeningsinstrumenten onder andere de G8, de Multidimensional Prognostic Index, de Timed Up and Go Test, loopsnelheid en de vraag naar een valincident in de afgelopen 6 maanden.

2. Een richtlijn van de Royal College of Anesthesists (2023) uit het Verenigd Koninkrijk stelt dat patiënten die kwetsbaar zijn een verhoogd risico hebben op ongunstige postoperatieve uitkomsten. Oudere patiënten die intermediair- en hoog-risico chirurgie ondergaan, moeten dan ook preoperatief gescreend moeten worden op kwetsbaarheid met een erkende screeningstool.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het doel van preoperatieve screening op kwetsbaarheid is om kwetsbare ouderen een CGA te bieden waardoor de risico’s van een operatie goed in kaart worden gebracht en waar mogelijk patiënten te optimaliseren. Ook helpt een CGA om de wensen van patiënten helder te krijgen. Ouderen scoren behoud van zelfstandigheid vaak als een belangrijker behandeldoel dan zo lang mogelijk leven. Het CGA kan helpen om de kans op behoud van zelfstandigheid in te schatten en tevens om het behoud en herstel van zelfstandigheid postoperatief te bevorderen (NVKG, 2021).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er zijn geen studies naar kosteneffectiviteit van screening op kwetsbaarheid in de preoperatieve setting. Screening neemt hooguit enkele minuten in beslag.

Een gerandomiseerde en dubbelblind gecontroleerde studie bij vaatchirurgische patiënten toonde dat een preoperatief uitgevoerd CGA leidde tot minder postoperatieve complicaties, minder delier, wondinfectie, en kortere opnameduur (Partridge et al., 2017). Een vervolganalyse toonde aan dat deze interventie kosteneffectief was (Partridge et al., 2021).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het gehele zorgpad voor (kwetsbare) ouderen die een indicatie hebben voor chirurgie dient de volgende onderdelen te bevatten: screening op kwetsbaarheid alsook op cognitieve stoornissen (zie module 2.2), een CGA op indicatie, en gezamenlijke besluitvorming in een multidisciplinair overleg (zie module 3 van deze richtlijn).

De screening kan plaatsvinden op de polikliniek van de snijdend hoofdbehandelaar of op de preoperatieve polikliniek van de anesthesiologie. De screening kan door verschillende personen worden uitgevoerd (verpleegkundige, verpleegkundig specialist, PA, arts). Vooraf dienen de personen die de screening gaan uitvoeren kort getraind te worden, dit betreft met name de cognitieve screening (zie module 2.2). Een (verkort) GA vraagt wat meer tijd en training, en kan door een verpleegkundige, verpleegkundig specialist of PA worden afgenomen. In het geval de verwijsbrief van de huisarts al vermeldt dat het om een kwetsbare patiënt gaat, kan de snijdend specialist ook direct naar de geriater/ internist ouderengeneeskunde verwijzen voor een CGA.

Een studie onder Nederlandse anesthesisten gaf aan dat 99% van de respondenten vond dat kwetsbaarheid het anesthesiologische beleid kan veranderen (Bouwhuis et al., 2021). Voor de praktische uitvoering is het belangrijk om de logistieke afspraken voor screening, en de samenwerking met snijdende specialismen enerzijds en de geriatrie/ ouderengeneeskunde anderzijds goed vorm te geven. In dezelfde studie gaf slechts 43% van de anesthesisten aan dat er een adequate samenwerking met geriaters was.

Onafhankelijk van welke werkwijze er gekozen wordt, moet er dus een specialist met geriatrische expertise betrokken zijn bij een protocol waarin de risico’s en de interventies beschreven worden. Lokaal kunnen afspraken worden gemaakt wie verantwoordelijk is voor de interventies.

Screening van de acute chirurgische patiënt

Spoedoperaties worden in de Nederlandse setting ingedeeld in 4 categorieën, namelijk een operatie moet starten: 1. binnen (30) minuten, 2. binnen uren (8 uur), 3. binnen dagen (bij voorkeur dezelfde dag), of 4. binnen 1 week (zie richtlijn ‘Beleid rondom spoedoperaties’ (NVvH 2018)). Voor categorie 3 en 4 is de werkgroep van mening dat er voldoende tijd is om bij oudere patiënten een screening uit te voeren in de klinische setting. Voor operaties die binnen uren uitgevoerd moeten worden, categorie 2, zal de screening vaker op de SEH uitgevoerd moeten worden. Hiervoor zou gebruik gemaakt kunnen worden van de APOP screener die op veel SEH’s al geïmplementeerd is en tevens de cognitieve functie screent (zie richtlijn ‘Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment’ (NVKG 2021)). Een tweede mogelijkheid is het gebruik van de Clinical Frailty Scale, ook deze is snel af te nemen. Meerdere systematische reviews beschrijven dat frailty in de acute chirurgische patiënt een sterke relatie toont met ongunstige postoperatieve uitkomsten (Fehlmann et al., 2022; Kennedy et al., 2022; Leiner et al., 2022; Ward et al., 2019).

Screening van patiënten <70 jaar

Het kan zinvol zijn om patiënten jonger dan 70 te screenen, met name als het om specifieke patiëntengroepen waarbij de biologisch leeftijd vaak ouder is dan de kalenderleeftijd. Dit betreft bijvoorbeeld patiënten met hoofd-halskanker (Bakas et al., 2023). Het is uiteraard ook mogelijk om patiënten jonger dan 70 voor een CGA te verwijzen wanneer de snijdend hoofdbehandelaar kwetsbaarheid of cognitieve problemen vermoedt.

Rationale van de aanbeveling:

Ouderen die kwetsbaar zijn hebben een 2- tot 4-maal hoger risico op nadelige postoperatieve uitkomsten en een hoger risico op postoperatieve sterfte vergeleken met ouderen die niet kwetsbaar zijn. Daarom is het belangrijk voor de operatie kwetsbare ouderen te identificeren bijvoorbeeld d.m.v. een korte screening. Voor de richtlijn is gekeken naar screeningsinstrumenten die in de Nederlandse setting gebruikt worden en ook in de literatuur onderzocht zijn. De belangrijkste screeningsinstrumenten in de preoperatieve setting zijn de Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), de Edmonton Frail Scale (EFS), de G8, de Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI) en de ISAR(-HP). De G8 is speciaal ontwikkeld voor de oudere kankerpatiënt en is een bruikbaar instrument gebleken voor de oncologische populatie (zie Richtijn Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA)). De grootte van de risico’s op ongunstige uitkomsten is verschillend tussen de diverse screeningsinstrumenten, net als de kwaliteit van het bewijs. De werkgroep adviseert om de screening altijd in samenwerking met de geriater/ internist ouderengeneeskunde van het ziekenhuis op te zetten, omdat een afwijkende screening een reden is om de patiënt te verwijzen voor een Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) voor nadere diagnostiek, risico-inventarisatie en voor eventuele optimalisatie en behandeling van kwetsbaarheid. De korte screening kan door verschillende personen worden afgenomen, kost enkele minuten en is weinig belastend voor de patiënt. Daarnaast is het ook mogelijk een verkort Geriatric Assessment (GA) uit te voeren, bijvoorbeeld bestaande uit een combinatie van een screeningstest en functionele testen zoals handknijpkracht of een loopsnelheid. Het uitvoeren van een verkort GA vraagt wel enige scholing, maar kan ook door verpleegkundigen worden uitgevoerd. Screening voorkomt dat fitte ouderen ten onrechte verwezen worden voor een CGA. Tenslotte sluit de aanbeveling aan bij internationale richtlijnen voor de perioperatieve zorg bij (kwetsbare) ouderen.

Onderbouwing

Conclusies

CFS

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with frailty as classified by CFS (≥5) have a higher risk of postoperative complications compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Ahola, 2022; Arteaga, 2020; Covino, 2022; Miguelena-Hycka, 2019; Niemeläinen, 2021; Sun, 2020; Tanaka, 2019; Tanaka, 2022; Yamada, 2021 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with frailty as classified by CFS have a higher risk of mortality compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Arteaga, 2020; Artiles-Armas, 2021; Covino, 2022; Hill, 2020; Miguelena-Hycka, 2019; Sanchez Arteaga, 2022; Sun, 2020; Tanaka, 2019; Tanaka, 2022; Vilches-Moraga, 2020; Wu, 2021; Yamada, 2021 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the risk of not returning home at discharge for patients with frailty as classified by CFS compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Ahola, 2022; Hill, 2020; Sun, 2020 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with frailty as classified by CFS have an impaired physical functioning after surgery compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Sun, 2020 |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome discharge destination, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

EFS

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with frailty as classified by EFS have a higher risk of postoperative complications compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Amabili, 2019 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with frailty as classified by EFS have a higher risk of mortality compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Dal Moro, 2017; Dasgupta, 2009; He, 2020; Nishijima, 2021 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with frailty as classified by EFS have a higher risk of not returning home at discharge compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Amabili, 2019; Dasgupta, 2009 |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with frailty as classified by EFS have a longer length of stay compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Dasgupta, 2009 |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome quality of life, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

G8

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with frailty as classified by G8 have a higher risk of postoperative complications compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Fagard, 2017; Kaibori, 2016; Kenig, 2020; Krenzlin, 2021; Niemeläinen, 2021; Nishijima, 2021; Souwer, 2018; Traunero, 2022 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with frailty as classified by G8 have a slightly higher risk of mortality compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Kaibori, 2016; Kenig, 2020; Krenzlin, 2021; Souwer, 2018 |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome discharge destination, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with frailty as classified by G8 have a longer length of stay compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Kaibori, 2016; Souwer, 2018 |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome quality of life, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

GFI

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with frailty as classified by GFI have a higher risk of postoperative complications compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Kenig, 2020; Krenzlin, 2021 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the risk of death after surgery or during follow-up for patients with frailty as classified by GFI compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Kenig, 2020; Krenzlin, 2021; Winters, 2018 |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome discharge destination, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome discharge destination, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

ISAR and ISAR-HP

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome complications, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Patients with frailty as classified by ISAR (Knauf) or ISAR-HP (Souwer) likely have a higher risk of mortality compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Knauf, 2022; Souwer, 2018 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Patients in the acute surgical setting (proximal femur fracture) with frailty as classified by ISAR likely have a higher risk of being discharged towards a healthcare facility compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Knauf, 2022 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Patients in the acute surgical setting (proximal femur fracture) with frailty as classified by ISAR likely have a higher risk of being unable to walk independently or at all, compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Knauf, 2022 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with frailty as classified by the ISAR-HP have a slightly longer mean length of hospital stay compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Souwer, 2018 |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated |

Mini-Cog

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the risk of complications after surgery or during follow-up for patients with possible cognitive impairment as classified by Mini-Cog compared to patients who are classified as a normal cognition.

Source: Heng, 2016; Korc-Grodzicki, 2015; Susano, 2020; Weiss, 2022 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with possible cognitive impairment as classified by Mini-Cog have a higher risk of mortality compared to patients who are classified as a normal cognition.

Source: Heng, 2016 and Weiss, 2022 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with possible cognitive impairment as classified by Mini-Cog have a higher risk of not returning home at discharge compared to patients who are classified as a normal cognition.

Source: Puustinen, 2016; Weiss, 2022 |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome discharge destination, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

VMS

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the risk of complications after surgery or during follow-up for patients with frailty as classified by VMS compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Van der Zanden, 2021 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with frailty as classified by VMS have a slightly higher risk of mortality compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Van der Zanden, 2021; Winters, 2018 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that patients with frailty as classified by VMS have a higher risk of not returning home at discharge compared to patients who are classified as not frail.

Source: Van der Zanden, 2021 |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome discharge destination, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

|

No GRADE |

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning, therefore the quality of the evidence could not be rated. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Ahola (2022) performed a retrospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (complications, discharge destination) related to frailty according to assessment according to the CFS screening tool. 95 patients with a minimum age of 80 years were included.

Amabili (2019) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, discharge destination) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the EFS screening tool. 254 patients with a median age of 80 years were included, of whom 20% were classified as frail.

Arteaga (2020) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the CFS screening tool. 92 patients with a mean age of 79 years were included.

Artiles-Armas (2021) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the CFS screening tool. 149 patients with a median age of 75 years were included, of whom 40% were classified as frail.

Covino performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the CFS screening tool. 1039 patients with a median age of 85 years were included, of whom 18% were classified as frail.

Dal Moro (2017) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the EFS screening tool. 78 patients with a mean age of 78.5 years were included, of whom 22% were classified as frail.

Dasgupta (2009) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (complications, discharge destination, length of stay) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the EFS screening tool. 12 patients with a mean age of 77.4 years were included.

Fagard (2017) performed a retrospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the EFS screening tool. 190 patients with a median

age of 77 years were included, of whom 61% were classified as frail.

He (2020) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the EFS screening tool. 134 patients with a mean age of 74 years were included, of whom 10% were classified as frail.

Heng (2016) performed a retrospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications) related to possible cognitive impairment according to preoperative assessment according to the Mini-Cog screening tool. 513 patients with a median age of 83 years were included, of whom 35% were classified as cognitive impaired.

Hill (2020) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications, discharge destination) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the CFS screening tool. 233 patients with a mean age of 84 years were included, of whom 44% were classified as frail.

Kaibori (2016) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications, length of stay) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the G8 screening tool. 71 patients with a median age of 71 years were included, of whom 55% were classified as frail.

Kenig (2020) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the G8 and GFI screening tools. 272 patients with a median age of 272 years were included, of whom 83% (G8) and 51% (GFI) were classified as frail.

Knauf (2022) performed a retrospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, discharge destination, physical functioning) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the ISAR screening tool. 15,099 patients with a median age of 85 years were included, of whom 81% were classified as frail.

Korc-Grodzicki (2015) performed a prospective retrospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (complications, i.e., delirium) related to possible cognitive impairment according to preoperative assessment according to the Mini-Cog screening tool. 416 patients with a median age of 80 years were included, of whom 31% were classified as cognitive impaired.

Krenzlin (2021) performed a retrospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the G8 and GFI screening tools. 104 patients with a mean age of 77 years were included, of whom 51% (G8) and 59% (GFI) were classified as frail.

Miguelena-Hylcka (2019) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the CFS screening tool. 143 patients with a mean age of 78 years were included, of whom 13% were classified as frail.

Niemeläinen (2021) performed a retrospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the CFS G8 screening tool. 161 patients with a mean age of 85 years were included, of whom 47% were classified as frail.

Nishjima (2021) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the EFS and G8 screening tools. 114 patients with a median age of 80 years were included, of whom 15% were classified as frail.

Puustinen (2016) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (discharge destination) related to possible cognitive impairment according to preoperative assessment according to the Mini-Cog screening tool. 52 patients with a mean age of 79 years were included, of whom 32% were classified as cognitive impaired.

Sanches Arteaga (2022) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the CFS screening tool. 92 patients with an approximate mean age of 77 years were included, of whom 9% were classified as frail.

Souwer (2018) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to both the ISAR-HP and G8 screening tool. 139 patients with a mean age of 77.7 years were included, of whom 14% were classified as frail.

Sun (2020) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications, discharge destination, physical functioning) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the CFS screening tool. 82 patients with a mean age of 82 years were included, of whom 32% were classified as frail.

Susano (2020) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (complications) related to possible cognitive impairment according to preoperative assessment according to the Mini-Cog screening tool. 229 patients with a median age of 75 years were included, with a median Mini-Cog score of 4.

Tanaka (2019) performed a retrospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the CFS screening tool. 96 patients with a median age of 82 years were included, of whom 17% were classified as frail.

Tanaka (2022) performed a retrospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the CFS screening tool. 36 patients with a median age of 77 years were included, of whom 44% were classified as frail.

Traunero (2022) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the G8 screening tool. 162 patients with a median age of 76 years were included, of whom 56% were classified as frail.

Van der Zanden (2021) performed a retrospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications, discharge destination) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the VMS screening tool. 157 patients with a median age of 74 years were included, of whom 39% were classified as frail.

Vilches-Moraga (2020) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the CFS screening tool. 113 patients with a mean age of 82 years were included, of whom 33% were classified as frail.

Weiss (2022) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications, discharge destination) related to possible cognitive impairment according to preoperative assessment according to the Mini-Cog screening tool. 1,338 patients with a mean age of approximately 77 years were included, of whom 21% were classified as cognitive impaired.

Winters (2018) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the GFI and VMS screening tools. 286 patients with a mean age of 83 years were included, of whom 26% (VMS) and 30% (GFI) were classified as frail.

Wu (2021) performed a retrospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the CFS screening tool. 397 patients with a mean age of 84 years were included, of whom 46% were classified as frail.

Yamada (2021) performed a prospective cohort study to assess the incidence of postoperative outcomes (mortality, complications) related to frailty according to preoperative assessment according to the CFS screening tool. 82 patients with a mean age of 80 years were included, of whom 23% were classified as frail.

No studies were found that reported on the relevant outcomes and screened for frailty using the instruments Fried frailty, Frailty index, Tilburg Frailty Indicator, 6-CIT, MMSE, and MOCA.

Results

CFS

Complications

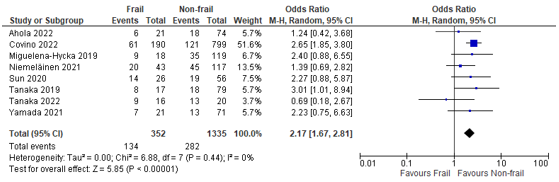

In total, nine (9) studies reported on postoperative complications in patients classified as frail according to the CFS, compared to patients not classified as frail (Ahola, 2022; Arteaga, 2020; Covino, 2022; Miguelena-Hycka, 2019; Niemeläinen, 2021; Sun, 2020; Tanaka, 2019; Tanaka, 2022; Yamada, 2021). When we summarized the results, a pooled odds ratio of 2.17 (95% CI: 1.67 to 2.81) could be calculated, which can be interpreted as a higher risk of complications in frail patients compared to non-frail patients. (Figure 1)

Figure 1 – Pooled estimate of risk of postoperative complications according to frailty status (CFS).

Mortality

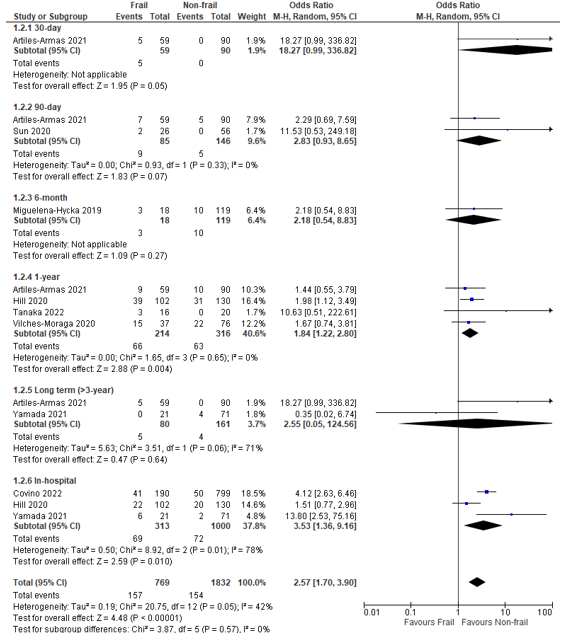

In total, twelve (12) studies reported on postoperative mortality in patients classified as frail according to the CFS, compared to patients not classified as frail (Arteaga, 2020; Artiles-Armas, 2021; Covino, 2022; Hill, 2020; Miguelena-Hycka, 2019; Sanchez Arteaga, 2022; Sun, 2020; Tanaka, 2019; Tanaka, 2022; Vilches-Moraga, 2020; Wu, 2021; Yamada, 2021).

When we summarized the results, a pooled odds ratio of 2.57 (95% CI: 1.70 to 3.90) could be calculated, which can be interpreted as a higher risk of mortality in frail patients compared to non-frail patients. (Figure 2) Studies reported mortality over different follow-up durations. We performed subgroup analyses of the results by follow-up duration.

Figure 2 – Pooled estimate of risk of postoperative mortality according to frailty status (CFS).

Discharge destination

In total, three (3) studies reported on postoperative discharge destination in patients classified as frail according to the CFS, compared to patients not classified as frail (Ahola, 2022; Hill, 2020; Sun, 2020). Ahola (2022) reported an OR of 1.17 (95% CI: 0.37 to 8.47); Hill (2020) reported 0.55 (95% CI: 0.35 to 0.95), and Sun (2020) reported 0.10 (95% CI: 0.01 to 0.95)

Physical functioning

In total, one (1) study reported on postoperative physical functioning in patients classified as frail according to the CFS, compared to patients not classified as frail (Sun, 2020). They reported an OR of 2.5 (95% CI 1.4 to 4.6) for a decline in ADL for each point increase in CFS.

Length of stay

No studies reported on the outcome length of stay.

Quality of life

No studies reported on the outcome quality of life.

EFS

Complications

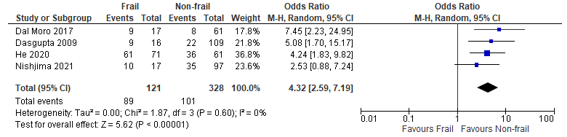

In total, four (4) studies reported on postoperative complications in patients classified as frail according to the EFS, compared to patients not classified as frail (Dal Moro, 2017; Dasgupta, 2009; He, 2020; Nishijima, 2021). When we summarized the results, a pooled odds ratio of 4.32 (95% CI: 2.59 to 7.19) could be calculated, which can be interpreted as a higher risk of complications in frail patients compared to non-frail patients. (Figure 3)

Figure 3 – Pooled estimate of risk of postoperative complications according to frailty status (EFS)

Mortality

In total, one (1) study reported on postoperative mortality in patients classified as frail according to the EFS, compared to patients not classified as frail (Amabili, 2019). They reported an odds ratio of 3.90 (95% CI: 1.42 to 10.67) which can be interpreted as a higher risk of mortality in frail patients compared to non-frail patients.

Discharge destination

In total, two (2) studies reported on postoperative discharge destination in patients classified as frail according to the EFS, compared to patients not classified as frail (Amabili, 2019; Dasgupta, 2009)

Amabili (2019) reported an adjusted odds ratio for being admitted to a healthcare facility of 1.7 (95% CI, 0.8-3.8), and an adjusted odds ratio for returning home for non-frail patients compared to frail patients of 2.6; 95% CI, 1.2-5.3.

Dasgupta (2009) reported an odds ratio for returning home of 0.27 (95% CI 0.09 to 0.81) for frail patients.

Physical functioning

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning.

Length of stay

In total, one (1) study reported on postoperative length of stay in patients classified as frail according to the EFS, compared to patients not classified as frail (Dasgupta, 2009). They reported a mean difference of 2.90 days (95% CI 1.22 to 4.58).

Quality of life

No studies reported on the outcome quality of life.

G8

Complications

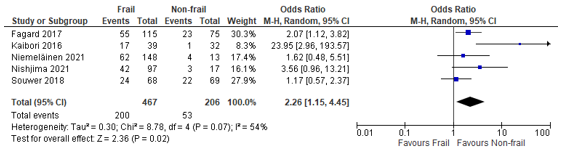

In total, nine (9) studies reported on postoperative complications in patients classified as frail according to the G8, compared to patients not classified as frail (Fagard, 2017; Kaibori, 2016; Kenig, 2020; Krenzlin, 2021; Niemeläinen, 2021; Nishijima, 2021; Souwer, 2018; Traunero, 2022)

When we summarized the results, a pooled odds ratio of 2.26 (95% CI: 1.15 to 4.45) could be calculated, which can be interpreted as a higher risk of complications in frail patients compared to non-frail patients. (Figure 4)

Figure 4 – Pooled estimate of risk of postoperative complications according to frailty status (G8)

Kenig (2020) reported a sensitivity of 94% (95% CI: 92 to 96), a specificity of 39% (24 to 52), a positive predictive value (PPV) of 80% (73 to 85), a negative predictive value (NPV) of 80% (73 to 85) and an area under the curve (AUC) of (95%CI) 0.75 (0.66 to 0.81) for complications.

Krenzlin (2021) reported an odds ratio of 3.68 (95% CI: 1.11 to 15.15).

Nishijima (2021) reported an odds ratio of 3.56 (95% CI: 0.96 to 13.21).

Traunero (2022) reported an odds ratio of 21.36 (7.98 to 74.58).

Mortality

In total, four (4) studies reported on postoperative mortality in patients classified as frail according to the G8, compared to patients not classified as frail (Kaibori, 2016; Kenig, 2020; Krenzlin, 2021; Souwer, 2018). They reported different outcome measures, therefore the results could not be pooled.

Kaibori (2016) reported an odds ratio of 8.24 (95% CI 0.43 to 159.04) for 1-year mortality.

Kenig (2020) reported a sensitivity of 98% (95% CI: 93 to 99), a specificity of 42% (27 to 55), a positive predictive value (PPV) of 34% (18 to 50), a negative predictive value (NPV) of 98% (93 to 99) and an area under the curve (AUC) of (95%CI) 0.74 (0.65 to 0.81) for 1-year mortality. They reported a sensitivity of 98% (95% CI: 93 to 99), a specificity of 49% (35 to 61), a positive predictive value (PPV) of 39% (24 to 52), a negative predictive value (NPV) of 97% (93 to 99) and an area under the curve (AUC) of (95%CI) 0.71 (0.61 to 0.78) for 30-day mortality.

Krenzlin (2021) reported a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.74 (95% CI 1.12 to 2.71).

Souwer (2018) reported an odds ratio of 1.0 (95%CI 0.2 to 5.2) for 30-day mortality and 1.4 (95% CI 0.3 to 6.4) for 6-month mortality.

Discharge destination

No studies reported on discharge destination.

Physical functioning

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning.

Length of stay

In total, two (2) studies reported on postoperative length of stay in patients classified as frail according to the G8, compared to patients not classified as frail (Kaibori, 2016; Souwer, 2018).

Kaibori (2016) reported an odds ratio of 3.33 (95% CI 1.25 to 8.86) for the risk of a length of hospital stay of 13 days or longer.

Souwer (2018) reported a mean (SD) length of hospital stay of frail patients of 8.3 (7.0) and non-frail patients of 9.0 (6.7).

Quality of life

No studies reported on the outcome quality of life.

GFI

Complications

In total, two (2) studies reported on postoperative complications in patients classified as frail according to the GFI, compared to patients not classified as frail (Kenig, 2020; Krenzlin, 2021)

Kenig (2020) reported a sensitivity of 58% (95% CI: 45 to 68), a specificity of 60% (48 to 70), a positive predictive value (PPV) of 63% (51 to 72), a negative predictive value (NPV) of 55% (42 to 66) and an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.60 (0.48 to 0.70) for 1-year mortality.

Krenzlin (2021) reported an odds ratio of 4.0 (95% CI: 1.07 to 14.90) for complications.

Mortality

In total, three (3) studies reported on postoperative mortality in patients classified as frail according to the GFI, compared to patients not classified as frail (Kenig, 2020; Krenzlin, 2021; Winters, 2018). They reported different outcome measures, therefore the results could not be pooled.

Kenig (2020) reported a sensitivity of 75% (95% CI: 63 to 79), a specificity of 56% (43 to 66), a positive predictive value (PPV) of 28% (12 to 42), a negative predictive value (NPV) of 90% (86 to 92) and an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.65 (0.54 to 0.74) for 1-year mortality. They reported a sensitivity of 73% (95% CI: 64 to 90), a specificity of 55% (42 to 66), a positive predictive value (PPV) of 24% (10 to 39), a negative predictive value (NPV) of 91% (88 to 93) and an area under the curve (AUC) of (95%CI) 0.64 (0.53 to 0.73) for 30-day mortality.

Krenzlin (2021) reported a hazard ratio of 1.67 (95% CI 1.09 to 2.57) for mortality.

Winters (2018) reported an odds ratio of 2.3 (95% CI 1.2 to 4.1) for 3-year mortality.

Discharge destination

No studies reported on the outcome discharge destination.

Physical functioning

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning.

Length of stay

No studies reported on the outcome length of stay.

Quality of life

No studies reported on the outcome quality of life.

ISAR and ISAR-HP

Mortality

In total, two (2) studies reported on postoperative mortality in patients classified as frail according to the ISAR (Knauf) or ISAR-HP (Souwer), compared to patients not classified as frail (Knauf, 2022; Souwer, 2018).

Knauf, 2022 reported an odds ratio of 3.45 (95% CI 2.44 to 5.03) for an increased risk of in-hospital mortality in patients with an acute proximal femoral fracture who were classified as frail according to the ISAR.

Souwer (2018) reported an odds ratio of 3.6 (95%CI 0.7 to 18.7) for 30-day mortality and 4.9 (95% CI 1.1 to 23.4) for 6-month mortality.

Complications

No studies reported on postoperative complications.

Discharge destination

Discharge destination was reported by Knauf, 2022; they reported an odds ratio of 0.42 (95% CI 0.38 to 0.47) for a decreased probability of returning home at hospital discharge for patients with an acute proximal femoral fracture who were classified as frail according to the ISAR.

Physical functioning

Physical functioning was reported by Knauf, 2022; they reported a odds ratio for walking ability 7 days postoperatively. The odds ratio for the risk of only being able to walk with walker for frail patients was 3.69 (95% CI 3.24 to 4.21), and the odds ratio for not being able to walk anymore was 12.52 (95% CI 10.13 to 15.48).

Length of stay

One (1) study reported on length of hospital stay in patients classified as frail according to the ISAR-HP, compared with patients not classified as frail (Souwer, 2018). They reported a mean (SD) length of hospital stay of frail patients of 10.3 (6.0) and non-frail patients of 8.9 (9.4).

Quality of life

No studies reported on the outcome quality of life.

Mini-Cog

Complications

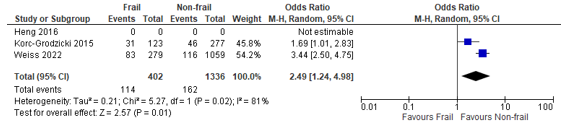

In total, four (4) studies reported on postoperative complications in patients classified as having possible cognitive impairment according to the Mini-Cog, compared to patients classified as having a normal cognition (Heng, 2016; Korc-Grodzicki, 2015; Susano, 2020; Weiss, 2022). Three studies were excluded because of the inclusion criteria of age ≥65 years, instead of ≥70 years (Culley, 2017; Tiwari, 2021; Yaima 2022). When we summarized the results of the 4 included studies, a pooled odds ratio of 2.49 (95% CI: 1.24 to 4.98) could be calculated, which can be interpreted as a higher risk of complications in possibly cognitive impaired patients compared to non-impaired patients. (Figure 5). Susano 2020) only reported a p-value of 0.333 without underlying data, this study could therefore not be pooled.

Figure 5 – Pooled estimate of risk of postoperative complications according to frailty status (Mini-Cog)

Mortality

In total, two (2) studies reported on postoperative mortality in patients classified as frail according to the Mini-Cog, compared to patients not classified as frail (Heng, 2016 and Weiss, 2022).

Heng (2016) reported adjusted hazard ratios (95%CI), adjusted for age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and fracture type:

- 1-year mortality: 1.41 (0.88 to 2.26)

- 6-month: 1.81 (0.97 to 3.39)

- 90-day: 1.81 (95% CI 0.97 to 3.39)

Weiss (2022) reported a crude odds ratio (95%CI) 1-year mortality: 1.50 (0.69 to 3.28) and an adjusted OR of 1.3 (95% CI: 0.6 to 2.6)

Discharge destination

In total, two (2) studies reported on postoperative discharge destination in patients classified as frail according to the Mini-Cog, compared to patients not classified as frail (Puustinen, 2016; Weiss, 2022).

Puustinen (2016) reported Mini-Cog scores of 2.68 (sd 1.25) for those patients discharged home, and 3.53 (sd 1.13) for those discharged to a healthcare center. The mean difference was 0.85 (95% CI: 0.13 to 1.57)

Weiss (2022) reported an odds ratio of 1.83 (95% CI: 1.23 to 2.72) to be discharged not home.

Physical functioning

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning.

Length of stay

No studies reported on the outcome length of stay.

Quality of life

No studies reported on the outcome quality of life.

VMS

Complications

In total, one (1) study reported on postoperative complications in patients classified as frail according to the VMS, compared to patients not classified as frail (Van der Zanden, 2021). They reported an odds ratio of 2.20 (95% CI: 1.07 to 4.54), indicating an increased risk of complications within the first 30 days after surgery for patients who were classified as frail according to VMS.

Mortality

In total, two (2) studies reported on postoperative mortality in patients classified as frail according to the VMS, compared to patients not classified as frail (Van der Zanden, 2021; Winters, 2018).

Van der Zanden (2021) reported an OR of 4.66 (95% CI: 0.19 to 116.20) for death within 90 days after surgery, indicating an increased risk of mortality for patients who were classified as frail according to VMS.

Winters (2018) presented hazard ratios (HR) for the risk of death during the 3 years after surgery. The 3-year survival HR was 3.5 (95% CI: 2.1 to 5.7), indicating an increased risk of mortality for patients who were classified as frail according to VMS.

Discharge destination

In total, one (1) study reported on postoperative complications in patients classified as frail according to the VMS, compared to patients not classified as frail (Van der Zanden, 2021). They reported an odds ratio of 2.86 (95% CI: 1.37 to 9.94), indicating an increased risk of being discharged not towards home for patients who were classified as frail according to VMS.

Physical functioning

No studies reported on the outcome physical functioning.

Length of stay

No studies reported on the outcome length of stay.

Quality of life

No studies reported on the outcome quality of life.

Level of evidence of the literature

|

|

Complications |

Mortality |

Discharge destination |

Physical functioning |

Length of stay |

Quality of life |

||||||

|

|

Effect size and direction |

Quality of evidence |

Effect size and direction |

Quality of evidence |

Effect size and direction |

Quality of evidence |

Effect size and direction |

Quality of evidence |

Effect size and direction |

Quality of evidence |

Effect size and direction |

Quality of evidence |

|

CFS |

↑↑F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

↑↑ F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

? |

⊕ Very Low GRADE* |

↓↓ F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

|

EFS |

↑↑F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

↑↑F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

↑ (not home) F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

↑F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

|

G8 |

↑↑F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

↑F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

↑↑ F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

|

GFI |

↑F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

↑F |

⊕ Very Low GRADE* |

⊕ No GRADE |

⊕ No GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

|

ISAR/ ISAR-HP |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

↑↑ F |

⊕⊕⊕ Moderate GRADE† |

↑↑ (not home) F |

⊕⊕⊕ Moderate GRADE† |

↓↓ F |

⊕⊕⊕ Moderate GRADE† |

↑ |

⊕ Low GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

|

Mini-Cog |

↑F |

⊕ Very Low GRADE* |

↑F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

↑ (not home) F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

|

VMS |

↑F |

⊕ Very Low GRADE* |

↑F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

↑↑ (not home) F |

⊕⊕ Low GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

No evidence |

⊕ No GRADE |

* Downgraded for uncertainty (confidence interval crosses the border of clinical relevance).

† Upgraded for large effect.

Zoeken en selecteren

Question 1: Which screening instruments for frailty and/or cognitive impairment that are already used in the Netherlands predict postoperative adverse outcomes for patients aged 70 years or older?

P: Patients aged 70 years or older with an indication for surgery

I: Screening instruments for frailty and/or cognitive impairment that are already used in the Netherlands

O: Test properties (positive/negative predictive value, sensitivity, specificity) for:

- Mortality: postoperative mortality, mortality at discharge, mortality at follow-up

- Complications: length of stay, readmission, pulmonary-cardiac, delirium, pressure ulcers, urinary tract infection, wound infection, falling

- Discharge destination: instituationalization after discharge, geriatric rehabiliation at discharge, independently living at home

- Physical functioning: functionering at discharge, functional decline, mobility, falls, walking independently/with walking aid

- Cognitive functioning

- Quality of life

- Social participation

- Pain

- Patient’s goal (attained?)

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered all outcome measures relevant in the patient-centred decision-making process. Whether an outcome measure is critical or important depends on the individual patient, so the working group did not distinguish critical or important outcome measures.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until October 6, 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 766 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic review of randomized controlled trials or observational studies, randomized controlled trials or observational studies, no case-control studies, no case reports or case series, written in English or Dutch, 49 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, sixteen (16) studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 33 studies were included.

Results

33 studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Bakas AT, Polinder-Bos HA, Streng F, Mattace-Raso FUS, Ziere G, de Jong RJB, Sewnaik A. Frailty in Non-geriatric Patients With Head and Neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023 Jun 2. doi: 10.1002/ohn.388. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37264978.

- Bouwhuis A, van den Brom CE, Loer SA, Bulte CSE. Frailty as a growing challenge for anesthesiologists - results of a Dutch national survey. BMC Anesthesiol. 2021 Dec 6;21(1):307. doi: 10.1186/s12871-021-01528-x. PMID: 34872523; PMCID: PMC8647406.

- Engel JS, Tran J, Khalil N, Hladkowicz E, Lalu MM, Huang A, Wong CL, Hutton B, Dhesi JK, McIsaac DI. A systematic review of perioperative clinical practice guidelines for care of older adults living with frailty. Br J Anaesth. 2023 Mar;130(3):262-271. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2022.12.010. Epub 2023 Jan 25. PMID: 36707368.

- Fehlmann CA, Patel D, McCallum J, Perry JJ, Eagles D. Association between mortality and frailty in emergency general surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022 Feb;48(1):141-151. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01578-9. Epub 2021 Jan 9. PMID: 33423069; PMCID: PMC8825621.

- Kennedy CA, Shipway D, Barry K. Frailty and emergency abdominal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgeon. 2022 Dec;20(6):e307-e314. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2021.11.009. Epub 2021 Dec 31. PMID: 34980559.

- Leiner T, Nemeth D, Hegyi P, Ocskay K, Virag M, Kiss S, Rottler M, Vajda M, Varadi A, Molnar Z. Frailty and Emergency Surgery: Results of a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Mar 31;9:811524. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.811524. PMID: 35433739; PMCID: PMC9008569.

- NVKG. Richtlijn Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA). Richtlijnendatabase; 2021. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/comprehensive_geriatric_assessment_cga/startpagina_-_comprehensive_geriatric_assessment_cga.html

- NVvH. Richtlijn Beleid rondom spoedoperaties. Richtlijnendatabase; 2018. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/beleid_rondom_spoedoperaties/classificatiesystemen_spoedoperaties.html

- Partridge JS, Harari D, Martin FC, Peacock JL, Bell R, Mohammed A, Dhesi JK. Randomized clinical trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and optimization in vascular surgery. Br J Surg. 2017 May;104(6):679-687. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10459. Epub 2017 Feb 15. PMID: 28198997.

- Partridge JSL, Healey A, Modarai B, Harari D, Martin FC, Dhesi JK. Preoperative comprehensive geriatric assessment and optimisation prior to elective arterial vascular surgery: a health economic analysis. Age Ageing. 2021 Sep 11;50(5):1770-1777. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afab094. PMID: 34120179.

- Royal College of Anesthesists. Chapter 2: Guidelines for the Provision of Anaesthesia Services for the Perioperative Care of Elective and Urgent Care Patients 2023. RCOA; https://rcoa.ac.uk/gpas/chapter-2

- Saur NM, Davis BR, Montroni I, Shahrokni A, Rostoft S, Russell MM, Mohile SG, Suwanabol PA, Lightner AL, Poylin V, Paquette IM, Feingold DL; Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Evaluation and Management of Frailty Among Older Adults Undergoing Colorectal Surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022 Apr 1;65(4):473-488. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000002410. PMID: 35001046.

- Ward MAR, Alenazi A, Delisle M, Logsetty S. The impact of frailty on acute care general surgery patients: A systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019 Jan;86(1):148-154. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002084. PMID: 30399129.

Evidence tabellen

Er wordt een preoperatieve screening naar kwetsbaarheid verricht bij patiënten van ≥70 jaar die indicatie hebben voor operatie met verwachte opnameduur ≥2 dagen. Indien afwijkend, wordt de patiënt verwezen voor een CGA.

Evidence tables

Research question: Hoe herken je kwetsbaarheid bij ouderen preoperatief?

Table of quality assessment – prognostic factor (PF) studies

Based on: QUIPSA (Haydn, 2006; Haydn 2013)

Research question: Hoe herken je kwetsbaarheid bij ouderen preoperatief?

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Study participation

Study sample represents the population of interest on key characteristics?

(high/moderate/low risk of selection bias) |

Study Attrition

Loss to follow-up not associated with key characteristics (i.e., the study data adequately represent the sample)?

(high/moderate/low risk of attrition bias) |

Prognostic factor measurement

Was the PF of interest defined and adequately measured?

(high/moderate/low risk of measurement bias related to PF) |

Outcome measurement

Was the outcome of interest defined and adequately measured?

(high/moderate/low risk of measurement bias related to outcome) |

Study confounding

Important potential confounders are appropriately accounted for?

(high/moderate/low risk of bias due to confounding) |

Statistical Analysis and Reporting

Statistical analysis appropriate for the design of the study?

(high/moderate/low risk of bias due to statistical analysis) |

|

Ahola, 2022 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Low risk No loss to follow-up reported |

Moderate risk Score calculated retrospectively |

Low risk Hospital records were used |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Amabili, 2019 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Low risk No loss to follow-up reported |

Low risk

|

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Arteaga, 2020 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Low risk No loss to follow-up reported |

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

|

Artiles-Armas, 2021 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Low risk No loss to follow-up reported |

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

|

Covino, 2022 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Low risk No loss to follow-up reported |

Low risk

|

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Dal Moro, 2017 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Low risk No loss to follow-up reported |

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

|

Dasgupta, 2009 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Low risk No loss to follow-up reported |

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

|

Fagard, 2017 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Low risk No loss to follow-up reported |

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

|

Geiss, 2021 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Moderate risk 24% loss to follow-up reported, without provision of reasons |

Low risk

|

Low risk

|

Moderate risk Unclear what the role of geriatric assessment has been.

|

High risk

Numbers don’t add up

|

|

He, 2020 |

Low risk |

Moderate risk

8/142 patients excluded because of cancelled or declined surgery, leading to risk of bias |

Low risk

Blinded assessment |

Low risk Hospital records used |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Heng, 2016 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Moderate risk Not reported |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk (appropriate adjustment) |

Low risk |

|

Hill, 2020 |

Moderate risk Only patients who stayed at the ICU for 24 hours or more were included, which may introduce survivorship bias. |

Moderate risk Not reported |

Moderate risk CFS potentially collected after recovery |

Low risk Family member follow-up |

Moderate risk |

|

|

Kaibori, 2016 |

Low risk |

Moderate risk Not reported |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk (prognostic research) |

Low risk |

|

Kenig, 2020 |

Low risk |

Low risk Low proportion loss to follow-up |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Knauf, 2022 |

Low risk |

Moderate risk High proportion of loss to follow-up |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Korc-Grodzicki, 2015 |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Krenzlin, 2021 |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Miguelena-Hycka, 2019 |

Low risk |

Moderate risk High proportion of loss to follow-up |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Niemeläinen, 2021 |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Nishijima, 2021 |

Moderate risk Large number of excluded patients, unclear |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

|

|

Puustinen, 2016 |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Sanchez Arteaga, 2022 |

High risk Patient flow unclear for large proportion of patients |

Moderate risk Outcomes unclear for large proportion of patients |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

High risk Unclear which patients were analysed |

|

Souwer, 2018 |

Low risk |

Low risk Low proportion loss to follow-up |

Low risk |

Low risk

Hospital records were used |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Sun, 2020 |

Moderate risk Exclusion criteria not clear, more patients excluded due to not having certain characteristics |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Susano, 2020 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Tanaka, 2019 |

Moderate risk

Retrospective analysis |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Tanaka, 2022 |

Moderate risk

Retrospective analysis |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Traunero, 2022 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Van der Zanden, 2021 |

Moderate risk

Retrospective analysis |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Vilches-Moraga, 2020 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Weiss, 2022 |

Moderate risk

Retrospective analysis |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Winters, 2018 |

Moderate risk

Retrospective analysis |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Wu, 2021 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

|

Yamada, 2021 |

Low risk Consecutive patients |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Low risk |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Geiss (2021) |

Numbers don’t add up |

|

Mezera (2022) |

Wrong I (postoperative asessement) |

|

Bessems (2021) |

Wrong I |

|

Abdullahi (2021) |

Wrong P |

|

Gronewold (2017) |

Wrong I |

|

Kaibori (2021) |

Wrong I |

|

Kenig (2015) |

Wrong I |

|

Mima (2021) |

Wrong P |

|

Rajeev (2019) |

No comparison |

|

Ruiz de Gopegui (2022) |

Wrong I |

|

Ruiz de Gopegui (2021) |

Wrong I |

|

Wang (2020) |

Wrong P |

|

Yajima (2022) |

Wrong P |

|

Aitken (2021) |

Wrong P |

|

Aucoin (2020) |

Wrong P |

|

Campi (2022) |

Wrong P |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 09-04-2024

Laatst geautoriseerd : 09-04-2024

Geplande herbeoordeling : 09-04-2028

Algemene gegevens

In samenwerking met : bovenstaande partijen, Verenso, Verpleegkundigen en Verzorgenden Nederland – Verpleegkundig Specialisten en Genero

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijn.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij chirurgie bij kwetsbare ouderen.

Werkgroep

Dr. D.E. (Didy) Jacobsen (voorzitter), Nederlandse Vereniging voor Klinische Geriatrie

Dr. H.A. (Harmke) Polinder-Bos, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Klinische Geriatrie

Dr. S. (Suzanne) Festen, Nederlandse Internisten Vereniging

N.S. (Niamh) Landa-Hoogerbrugge, MSc Verpleegkundigen en Verzorgenden Nederland en Verpleegkundigen en Verzorgenden Nederland – Verpleegkundig Specialisten

Dr. H.P.A. (Eric) van Dongen, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Anesthesiologie

Dr. J. (Juul) Tegels, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde

Drs. P.E. (Petra) Flikweert, Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging

Drs. H.P.P.R. (Heike) de Wever, Verenso

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger

M.R. (Marike) Abel- van Nieuwamerongen, Genero

Met ondersteuning van

Drs. E.A. (Emma) Gans, adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Drs. L.A.M. (Liza) van Mun, junior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Dr. T. (Tim) Christen, adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Dr. J.F. (Janke) de Groot, senior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Y. (Yvonne) van Kempen, projectsecretaresse, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Naam |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Persoonlijke Financiële Belangen |

Persoonlijke Relaties |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek |

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie |

Overige belangen |

Datum |

Actie |

|

Didy Jacobsen (voorzitter) |

Internist-ouderengeneeskunde, academisch medisch specialist, Radboudumc afdeling geriatrie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

- |

Niet aanwezig. |

Nieuwe onderzoeksvoorstel op het gebied van zorgpadoptimalisatie/zorgpadontwikkeling voor ouderen met hoogrisico plaveiselcelcarcinoom. Vanuit dermatologie (Radboudumc) wordt dit opgezet. Ik denk mee voor geriatrisch perspectief. |

30-09-2021 |

Geen restricties |

|

Heike de Wever |

Specialist ouderengeneeskunde, kaderarts geriatrische revalidatie bij de stichting TanteLouise |

Lid van kerngroep kaderartsen geriatrische revalidatie van Verenso (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Neen |

Neen |

Neen |

Neen |

1-12-2021 |

Geen restricties |

|

Suzanne Festen |

Internist ouderengeneeskunde |

Nvt |

Geen belangenverstrengeling |

Geen belangenverstrengeling |

Betrokken bij ZIN subsidie en KWF subsidie |

Behoudens dat de inhoud raakt aan mijn expertise in klinisch werk en onderzoek geen belangen. |

Nvt |

11-11-2021 |

Geen restricties |

|

Eric van Dongen |

Anesthesioloog maatschap anesthesiologie, ic en pijnbestrijding |

Bestuur E infuse, vacatiegelden |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Co-founder AGE MDO, ketenzorg perioperatief proces kwetsbare oudere |

Geen |

11-10-2021 |

Geen restricties |

|

Harmke Polinder- Bos |

Klinisch Geriater, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

2021: COOP-studie |

Behoudens dat de inhoud raakt aan mijn expertise in klinisch werk en onderzoek geen belangen. |

Geen |

4-10-2021 |

Geen restricties |

|

Niamh Landa - Hoogerbruggen |

Verpleegkundig specialist GE-chirurgie/klinische geriatrie Maasstad ziekenhuis |

Bestuurslid V&VN geriatrie en gerontologie |

Nee |

Nee |

Nee |

Neveneffect kan zijn meer expertise ontwikkelen op dit gebied en zodoende integreren in huidig zorgpad dieontwikkeld is |

Nee |

29-09-2021 |

Geen restricties |

|

Juul Tegels |

Lid richtlijnwerkgroep |

Traumachirurg, fellow |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Geen |

18-3-2022 |

Geen restricties |

|

Petra Flikweert |

Orthopedisch chirurg, Reinier haga orthopedisch centrum, zoetermeer. Vanuit de NOV gemandateerde voor de werkgroep. |

Commissie kwaliteit - Haga ziekenhuis - onbetaald Commissie kwaliteit - NOV - onbetaald Onderwijscommissie NOV - onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

3-9-2023 |

Geen restricties |

|

Marike Abel- van Nieuwamerongen |

Lid ouderen- en mantelzorgforum; Genero (onbezoldigd> onkostenvergoeding) |

Lid RvT landelijke medezeggenschapsorganisatie cliënten Lid Cliëntenraad ziekenhuis in Tilburg Lid Cliëntenraad 1e lijnsorganisatie in Etten-Leur (onbetaalde functies, wel onkostenvergoeding) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

6-9-2023 |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en KBO-PCOB voor de schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Genero, KBO-PCOB en Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er [waarschijnlijk geen/ mogelijk] substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst kwalitatieve raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Preoperatieve herkenning van kwetsbaarheid |

geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de werkgroep de knelpunten in de chirurgische zorg voor kwetsbare ouderen. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbevelingen uit de eerdere richtlijnmodule (NVKG, 2016) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door betrokken partijen via een schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen