Postoperatieve samenwerking bij chirurgie bij kwetsbare ouderen

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de meerwaarde van het betrekken van geriatrische expertise in de postoperatieve fase bij kwetsbare ouderen na acute- en of electieve chirurgie?

Aanbeveling

Organiseer een samenwerkingsvorm waar medebehandeling door de geriatrie/ouderengeneeskunde samen met de hoofdbehandelaar laagdrempelig of standaard ingezet wordt bij kwetsbare ouderen die electieve of acute chirurgie hebben ondergaan.

Richt een multidisciplinair overlegmoment in, waarbij alle betrokken (para)medische disciplines vertegenwoordigd zijn, om de zorg van gecompliceerde en langdurig opgenomen kwetsbare ouderen te evalueren ten opzichte van diens doelen en wensen.

Inventariseer gezamenlijk en vroegtijdig de benodigde nazorg en ontslagbestemming voor kwetsbare ouderen en streef ernaar om de huisarts en/of specialist ouderengeneeskunde hierbij te betrekken.

Investeer in goede samenwerkingsverbanden met de eerste lijn, en de geriatrische revalidatiezorg in het bijzonder, om snel ontslag naar de juiste bestemming te bevorderen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Uit een literatuuranalyse voor de richtlijn CGA en een literatuuranalyse voor de proximale femurfractuur bij ouderen, onderdeel van de oudere versie van de richtlijn Behandeling kwetsbare ouderen bij chirurgie, blijkt dat structurele medebehandeling door een geriatrisch expertise team bij patiënten ouder dan 70 jaar met een heupfractuur leidt tot minder postoperatieve complicaties tijdens de opname. Ook zijn er aanwijzingen dat de kans op overlijden afneemt, de kans op herstel tot oorspronkelijk functieniveau toeneemt en ook de kans op ontslag naar oorspronkelijke woonsituatie toeneemt.

In de huidige literatuuranalyse, die zich niet beperkt tot patiënten met een heupfractuur maar zich richt op kwetsbare ouderen die chirurgie hebben ondergaan, wordt een zeer lage tot lage bewijskracht gevonden voor de effectiviteit van (mede) behandeling van een professional(s) met geriatrische expertise (hierna: co-management) bij kwetsbare ouderen die een chirurgische ingreep hebben ondergaan. De belangrijkste reden voor de lage kwaliteit van bewijs is de inclusie van cohortstudies, en het gebrek aan RCT’s, wat kan leiden tot vertekening van de resultaten. Daarnaast zijn veel uitkomstmaten maar bij kleine aantallen patiënten onderzocht. Verder bestond de interventie vaak niet alleen uit co-management, maar werd aanvullend een preoperatief comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) gedaan of werd er een snellere doorstroming van opname tot ontslag gewaarborgd bij de interventiegroep, terwijl dit niet bij de controlegroep werd gedaan.

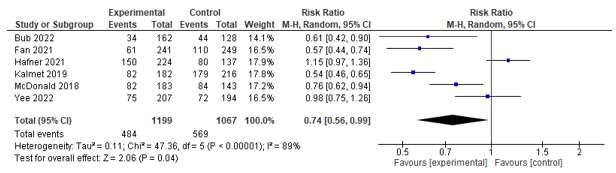

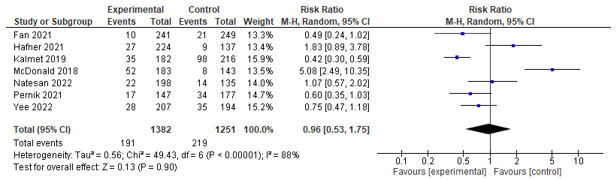

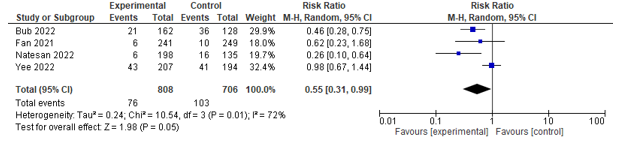

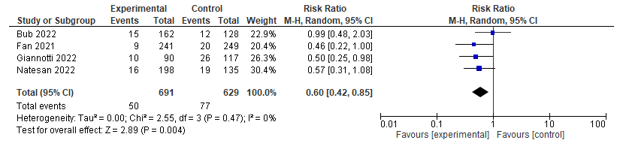

De gevonden studies laten een positief en duidelijk significant effect van co-management zien op enkele patiëntuitkomsten: postoperatieve complicaties (overall) met een relatieve risicoreductie van 26% (Hafner (2021) Yee (2022) Bub (2022) Fan (2021) Kalmet (2019) McDonald (2018)), postoperatieve urineweginfecties (Bub (2022) Fan (2021) Yee (2022) Natesan (2022)) en pneumonie (Bub (2022) Fan (2021) Giannotti (2022) Natesan (2022)), en heropname na 30 dagen (McDonald (2018) Giannotti (2022) Natesan (2022) Pernik (2021)). De bewijskracht hiervan is laag te noemen. Er werd ook een positief effect gevonden op zelfstandig functioneren (ADL) (Yee (2022)), maar de bewijskracht hiervan is zeer laag. Voor de andere gedefinieerde uitkomstmaten zoals delier, kwaliteit van leven, mortaliteit, opnameduur en ontslagbestemming, werd geen effect aangetoond. Ook van deze laatste uitkomstmaten is de bewijskracht zeer laag te noemen.

Desondanks is een deel van de factoren die de studies vertekenen ten dele wel toe te schrijven aan de interventie, zoals het doen van een CGA. Welk deel van de interventie precies tot welk gevolg leidt, is dan echter niet te onderscheiden. De werkgroep is van mening dat de gevonden positieve effecten toch representatief kunnen zijn voor het werkelijke effect van co-management bij deze patiëntengroep.

Specificering van de meest doelmatige invulling van geriatrische medebehandeling is niet te geven door de heterogeniteit van de interventies. Daarnaast is bij deze literatuurstudie gezocht met de term ‘co-management´ als synoniem voor de Nederlandse term medebehandeling. De term ‘multidomain intervention´ of ‘multidisciplinary management’ wordt echter ook regelmatig gebruikt in Engelse literatuur om medebehandeling te omschrijven.

Internationale richtlijnen

Met de aanbevelingen in deze module sluiten wij aan bij een internationale beweging om de postoperatieve zorg voor kwetsbare ouderen multidisciplinair in te richten, waarbij geriatrische expertise wordt geborgd. In internationale richtlijnen worden vergelijkbare adviezen gegeven om óf geriatrische medebehandeling óf specifieke geriatrische zorg te bieden in de postoperatieve fase om de kans op complicaties te verkleinen.

In de richtlijn Hip fracture management, laatst geüpdatet in 2023, van het National Institute of Health and Care excellence (NICE) uit de Verenigd Koninkrijk wordt bijvoorbeeld aanbevolen om ‘multidisciplinary management’ te bieden bij patiënten die orthopedische chirurgie ondergaan waarbij specifiek geadviseerd wordt om postoperatief te beoordelen op een delier en delierpreventieve maatregelen in te zetten (NICE, 2023).

In de richtlijn The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Evaluation and Management of Frailty Among Older Adults Undergoing Colorectal Surgery (Saur et al., 2022) wordt beschreven dat kwetsbare ouderen mogelijk baat hebben van een multidisciplinaire aanpak van perioperatieve zorg met daarbij specifiek betrokkenheid van een zorgprofessional met geriatrische expertise. Hierbij refereren zij o.a. naar de studie van Shahrokni et al. uit 2022. Deze studie beschrijft dat de kans op 90 dagen mortaliteit in de groep van kwetsbare ouderen met meer dan 50% afnam nadat geriatrische medebehandeling na oncologische chirurgie werd ingevoerd. Ook werd er meer gebruik gemaakt van paramedische inzet. Een andere studie beschrijft dat er minder ´geriatrische´ complicaties voorkomen in de geriatrische medebehandeling groep (Tarazona-Santabalbina et al., 2019). The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons voerde een review van 12 andere studies uit, waaruit ook blijkt dat geriatrische medebehandeling leidt tot korte opnameduur, lagere mortaliteit en kleinere kans op heropnames. Ook adviseren zij sterk dat er postoperatief beoordeeld moet worden op een delier met zonodig behandeling. Op basis van deze aanbevelingen is een programma ontwikkeld om perioperatieve zorg te optimaliseren voor de kwetsbare ouderen genaamd de Geriatric Surgery Verification Program in 2019 (American College of Surgeons, 2019). Ook hier adviseren zij om postoperatief bij hoog risicopatiënten (die als zeer kwetsbaar beschouwd worden op basis van geriatrische screeningsinstrumenten) multidisciplinaire zorg te bieden met onder andere een zorgprofessional met geriatrische expertise. Daarnaast adviseren zij ook dat kwetsbare ouderen postoperatief gescreend moeten worden op een delier en hier adequaat voor behandeld moeten worden.

Ook de richtlijn ‘Perioperative Care of People Living with Frailty van Centre of Perioperative Care’ (Centre for Perioperative Care, 2021) uit het Verenigd Koningrijk beschrijft dat elk ziekenhuis een perioperatief ´kwetsbaarheid´ team zou moeten hebben met geriatrische expertise die gedurende het gehele zorgpad aangeboden wordt. Hierbij dient specifiek aandacht te zijn voor postoperatieve complicaties, revalidatie en ontslagbestemming, proactieve zorgplanning, effectieve communicatie met patiënt en familie en er moet zorg worden gedragen voor gestructureerde samenwerking met andere zorgprofessionals van andere specialismen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

In het kader van postoperatieve zorg bij kwetsbare ouderen zijn de wensen en behoeftes van de patiënt en zijn omgeving erg belangrijk. Het is belangrijk dat de behoefte en niveau van benodigde ondersteuning wordt ingeschat alsook de omvang en belastbaarheid van het sociaal vangnet waarover de patiënt beschikt. Herstel- en revalidatiedoelen moeten worden besproken.

De doelen en wensen van de patiënt zijn bij voorkeur preoperatief al in kaart gebracht (zie module 3). Echter, in geval van spoed chirurgie kan dit in sommige gevallen pas postoperatief plaatsvinden. In dat geval moeten de doelen en wensen geïnventariseerd worden op het vroegst mogelijk moment in de postoperatieve zorg van de patiënt.

In het beste geval gebeurt deze inventarisatie multidisciplinair in het kader van co-management waarbij gelet kan worden op praktische (on)mogelijkheden op basis van beschikbaarheid van disciplines (of diens vertegenwoordigers), moment van de dag (avond- nacht- en weekend), aard en ernst van eventuele spoedeisendheid van de ingreep.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Kosteneffectiviteit van gestructureerde postoperatieve geriatrische medebehandeling is met name onderzocht voor de orthogeriatrische samenwerking. Allereerst concludeerde een systematic review en meta-analyse van Van Heghe et al. (2022) op basis van vijf eerdere studies dat orthogeriatrische samenwerking waarschijnlijk leidt tot lagere kosten. Met name de geïncludeerde studie van Miura et al. (2009) liet een significante afname van kosten zien na invoering van de samenwerking. Nieuwe studies laten ook een significante kostenreductie zien door orthogeriatrische samenwerking (Breda et al., 2023). Baji et al. (2023) identificeerde organisatie-gerelateerde factoren die geassocieerd waren met mortaliteit en kosten bij ouderen (>60 jaar) met een heupfractuur met behulp van een grote registratiedatabase van 178.757 patiënten uit 172 ziekenhuizen in het Verenigd Koninkrijk. Deze studie toonde dat betrokkenheid van een orthogeriater (geriater met orthopedische expertise) binnen 72 uur na opname geassocieerd was met een gemiddelde kostenbesparing van £529 (95% CI £148-910) per patiënt. Wanneer een orthogeriater daarnaast ook aanwezig was bij de grote visite was dit geassocieerd met een kostenreductie van £356 (95% CI £188-525) per patiënt. Naar kosteneffectiviteit van gestructureerde postoperatieve geriatrische medebehandeling bij andere vormen van (electieve of acute) chirurgie is weinig onderzoek gedaan. Een retrospectieve studie van Cizginer et al. (2023) bij oudere patiënten met colorectale chirurgie liet een kostenreductie van $10.297 per patiënt zien na invoering van structurele postoperatieve geriatrische medebehandeling. Op gebied van arbeidsintensiteit, benodigd personeel en middelen zal medebehandeling duurder zijn. Echter, het is aannemelijk dat wanneer medebehandeling van de kwetsbare oudere leidt tot een afname van complicaties en ligduur, dit ook bij andere typen operaties tot kostenreductie zal leiden. Bovendien kan intensievere begeleiding en oog voor patiënt, omgeving en hun kwaliteit van leven tot positievere ervaring van het ziekteproces leiden en daarmee ook tot goed sociaal en maatschappelijk draagvlak voor co-management.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De literatuur voorziet niet specifiek in een advies, heldere onderbouwing of praktische invulling van postoperatieve samenwerking bij kwetsbare ouderen na chirurgie. De samenwerkingsvormen die beschreven worden in de gevonden literatuur betreffen vaak een preoperatief CGA en postoperatief structurele medebehandeling met dagelijkse, twee- of driewekelijkse beoordelingen van een zorgprofessional met geriatrische expertise samen met het chirurgische team en daarnaast ook dagelijks of wekelijks een multidisciplinair overleg.

Voor de postoperatieve zorg van kwetsbare ouderen is aan te bevelen dat er afspraken worden gemaakt over de samenwerkingsvorm met de geriatrie/ouderengeneeskunde. Bij voorkeur moet er sprake zijn van intensieve samenwerking waarbij de geriatrie/ouderengeneeskunde standaard in medebehandeling is bij kwetsbare ouderen. De vorm waarin deze medebehandeling geboden wordt, kan op verschillende manieren ingezet worden, bijvoorbeeld standaard medebehandeling de eerste 3 dagen na operatie, of aansluiten van het geriatrisch expertise team bij een reguliere (multidisciplinaire) bespreking, danwel het overdragen van het hoofdbehandelaarschap wat bij de orthogeriatrische patiënten vaak gedaan wordt. De precieze functie van de afvaardigingen van de betrokken disciplines (bijvoorbeeld medisch specialist, arts-assistent, verpleegkundig specialist, physician assistant etc.) kan ook variabel zijn. Hierbij moeten duidelijke lokale afspraken gemaakt worden over de betrokkenheid van elk van deze disciplines.

Op geleide van de gezamenlijke beoordeling van de patiënt kunnen laagdrempelig andere disciplines betrokken worden. Hierbij kan gedacht worden aan vertegenwoordiging van fysiotherapie, diëtiek, ergotherapie, maatschappelijk werk etc. De anesthesioloog is standaard betrokken in de pre- en peroperatieve fase, en postoperatief vaak in de vorm van het acute pijnteam. De intensive care kan laagdrempelig gevraagd worden om een kwetsbare oudere mee te beoordelen in de kliniek indien nodig.

Een wekelijkse bijeenkomst waarin vertegenwoordigers van alle betrokken disciplines aanwezig zijn, kan de samenwerking en kwaliteit van zorg mogelijk verder verbeteren. In de praktijk lijkt het bij kwetsbare ouderen die een gecompliceerd beloop hebben of langdurig zijn opgenomen moeilijk om de behandeling aan te passen dan wel te stoppen als hun kwaliteit van leven sterk verminderd lijkt te zijn met beperkte kans op herstel. Specifiek bij deze patiëntengroep is het evalueren van de zorg, eventueel opnieuw op basis van de vier assen van de geriatrie/ouderengeneeskunde, zeer belangrijk. Dit kan laagdrempelig worden gedaan in deze wekelijkse bijeenkomst waarbij ook de benodigde nazorg en passende ontslagbestemming besproken kan worden

Voor veelvoorkomende patiënt categorieën kunnen deze werkafspraken in een lokaal nazorgprotocol worden vastgelegd die centraal via de instelling beschikbaar zijn.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

In de voorgaande versie van de richtlijn ‘Behandeling kwetsbare ouderen bij chirurgie’ en de richtlijn ‘Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment’ zijn de bewijskracht en overwegingen voor geriatrische medebehandeling bij patiënten met een heupfractuur uitgebreid beschreven. Dit leidde tot de aanbeveling om structurele geriatrische medebehandeling in te zetten voor patiënten van 70 jaar en ouder met en heupfractuur (Zie richtlijn Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, module 8.3). Voor patiënten met electieve operaties, of een niet-orthopedische acute operatie is minder bewijskracht. Dit wordt veroorzaakt door het grotendeels afwezig zijn van randomised controlled trials (RCT’s) en de heterogeniteit van de interventies. Echter, vele observationele voor-na studies laten een gunstig effect zien van geriatrische medebehandeling op het verbeteren van postoperatieve uitkomsten voor ouderen. Op basis van de meta-analyse van de literatuur voor deze richtlijn is geriatrische medebehandeling geassocieerd met een lagere kans op postoperatieve complicaties en heropnames <30 dagen, en infecties. Het is dan ook aannemelijk dat het organiseren van een samenwerkingsvorm met postoperatief geriatrische medebehandeling voor kwetsbare ouderen zal leiden tot een significante verbetering van het postoperatief beloop en herstel, patiënttevredenheid en het postoperatief functioneren.

Specificering van de meest doelmatige invulling van geriatrische medebehandeling is niet te geven door de heterogeniteit van de interventies. Het van belang dat er voor de daadwerkelijke invulling van de postoperatieve samenwerking gekeken wordt naar de lokale behoeftes en mogelijkheden. In Nederland zijn verschillende soorten samenwerkingsvormen ontstaan die als ´best practices´ gezien kunnen worden, waaronder de Geriatrische Trauma Unit. In 2024 zal er een handboek verschijnen waarin wordt beschreven hoe dit het beste te organiseren. Belangrijk is dat voor de invulling van de postoperatieve samenwerking voor kwetsbare ouderen op lokaal niveau, de snijdende specialismen en de geriatrie/interne geneeskunde-ouderengeneeskunde samen de verbinding zoeken om dit uit te voeren en te coördineren.

Een potentieel nadeel van geriatrische medebehandeling en betrokkenheid van andere (para)medische diensten is de arbeidsintensiteit en daarmee gepaard gaande kosten. Echter, de verwachting is ook dat deze investering zal leiden tot minder complicaties, kortere ligduur, en minder heropnames. Hiermee worden ook kosten bespaard. Ook is aangetoond dat orthogeriatrische samenwerkingen voor de kwetsbare ouderen met heupfracturen kosteneffectief is. Tevens zal deze multidisciplinaire inspanning ertoe leiden dat het behandelplan voor patiënten met een gecompliceerd beloop regelmatig geëvalueerd zal worden, en dat de wensen en doelen van de patiënt hierin worden meegenomen. Ook zal dit bijdragen aan vroegtijdige nazorg en ontslagplanning. In het bijzonder indien er ook geïnvesteerd wordt in een (structurele) samenwerkings- of overlegvorm met de eerstelijns- of geriatrische revalidatiezorg. Daarbij heeft het ook de voorkeur om de ontslagbestemming reeds preoperatief te bespreken met patiënt, familie, (mede)behandelaren zowel in de eerstelijns- als geriatrische revalidatiezorg. Deze inspanningen zullen leiden tot het leveren van passende zorg op de juiste plek en snellere doorstroming.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Kwetsbare ouderen worden steeds vaker naar het ziekenhuis verwezen voor een operatieve behandeling. Dit kan zowel acuut als electief zijn. Op dit moment bestaat er praktijkvariatie óf, en op welke manier het specialisme geriatrie of interne geneeskunde-ouderengeneeskunde betrokken wordt in de postoperatieve fase. In de postoperatieve fase zijn er in de Nederlandse zorg verschillende samenwerkingsvormen ontstaan. Samenwerking kan variëren van een eenmalig consult tot aan een geïntegreerd team met geriatrische en chirurgische expertise dat gezamenlijk intensieve zorg biedt in het postoperatieve traject. Het bekendste voorbeeld daarvan is de Geriatrische Trauma Unit (GTU) waarbij er standaard medebehandeling is van het geriatrisch expertise team bij patiënten van 70 jaar of ouder met een heupfractuur. Op dit moment is het onduidelijk hoe de postoperatieve samenwerking het beste ingericht kan worden en wat de effectiviteit daarvan is. Deze module beschrijft de verschillende samenwerkingsvormen die er zijn vanuit de literatuur met daarbij postoperatieve uitkomsten en geeft aanbevelingen hoe dit in de dagelijkse praktijk te organiseren.

Conclusies

Functioning

Mobility

Postoperative mobilization

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on postoperative mobilization when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Hafner (2021); Pernik (2021) |

Transfers

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on the ability to make transfers when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Yee (2022) |

Activities of daily living

|

Very low GRADE

|

Co-management may increase independence in ADL when compared with control in frail older patients. The evidence is very uncertain.

Source: Yee (2022) |

Instrumental activities of daily living

|

No GRADE

|

No evidence was found regarding the effect of co-management on instrumental activities of daily living when compared with control in frail older patients. |

Cognitive disorders

|

No GRADE

|

No evidence was found regarding the effect of co-management on cognitive disorders in frail older patients. |

Quality of life

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on quality of life when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Kalmet (2019) |

Post-operative Complications

|

Low GRADE

|

Co-management may reduce the incidence of overall post-operative complications when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Bub (2022); Fan (2021); Hafner (2021); Kalmet (2019); McDonald (2018); Yee (2022) |

Delirium

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on post-operative delirium when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Fan (2021); Hafner (2021); Kalmet (2019); McDonald (2018); Natesan (2022); Pernik (2021); Yee (2022) |

Infections

Urinary tract infection

|

Low GRADE

|

Co-management may reduce the occurrence of post-operative urinary tract infections compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Bub (2022); Fan (2021); Natesan (2022); Yee (2022) |

Pneumonia

|

Low GRADE

|

Co-management may reduce the occurrence of post-operative pneumonia compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Bub (2022); Fan (2021); Natesan (2022); Giannotti (2022) |

Sepsis

|

Very low GRADE

|

Co-management may reduce the occurrence of post-operative sepsis compared with control in frail older patients. The evidence is very uncertain.

Source: Giannotti (2022) |

Falls

In-hospital falls

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on in-hospital falls when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Hafner (2021) |

Cardiopulmonary complications

Pulmonary complications

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on post-operative pulmonary complications when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Hafner (2021) |

Cardiac complications

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on post-operative cardiac complications when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Hafner (2021) |

Myocardial infarction

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on post-operative myocardial infarction when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Bub (2022); Natesan (2022); Fan (2021) |

Thromboembolic complications

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on post-operative thromboembolic complications when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Bub (2022); Fan (2021) |

Cerebral vascular accident

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on post-operative cerebral vascular accidents when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Bub (2022); Fan (2021) |

Haematological complications

|

Very low GRADE

|

Co-management may reduce haematological complications when compared with control in frail older patients. The evidence is very uncertain.

Source: Giannotti (2022) |

Length of stay

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on length of stay when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Bub (2022); Fan (2021); Giannotti (2022); Hafner (2021); Kalmet (2019); McDonald (2018); Natesan (2022); Shahrokni (2020); Pernik (2021); Yee (2022) |

Discharge destination

Facility

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on discharge destination when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Bub (2022); McDonald (2018) |

Returning home (with self-care)

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on returning home when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Bub (2022); McDonald (2018); Yee (2022) |

Usage of health services when returning home

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on usage of health services when returning home when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: McDonald (2018) |

Readmission

7-days readmission

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on 7-days readmission when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: McDonald (2018); Pernik (2021) |

28-days readmission

|

Very Low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on 28-days readmission rates when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Yee (2022) |

30-days readmission

|

Low GRADE

|

Co-management may reduce 30-days readmission rates when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: McDonald (2018); Natesan (2022); Pernik (2021); Giannotti (2022) |

90-days readmission

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on 90-days readmission when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Giannotti (2022); Pernik (2021) |

1-year readmission

|

Very low GRADE

|

Co-management may reduce rates of 1-year readmissions when compared with control in frail older patients. The evidence is very uncertain.

Source: Giannotti (2022) |

Mortality

30-day mortality

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on 30-day mortality when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Fan (2021); Giannotti (2022); Kalmet (2019); Yee (2022) |

90-day mortality

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on 90-day mortality when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Giannotti (2022); Shahrokni (2020) |

1-year mortality

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on 1-year mortality when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Giannotti (2022); Kalmet (2019); Yee (2022) |

In-hospital mortality

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of co-management on in-hospital mortality when compared with control in frail older patients.

Source: Bub (2022); Fan (2021); Hafner (2021) |

Overgenomen zoekvraag

De zoekvraag en samenvatting van de literatuur uit de module ‘Herstelmaatregelen na proximale femurfractuur’ uit 2016 is toegevoegd, omdat voor de literatuursearch bij de nieuwe richtlijn studies geïncludeerd zijn vanaf 2016. De bewijskracht van alle eerdere studies is echter van blijvende relevantie voor met name de oudere patiënten met een proximale femurfractuur.

Uitgangsvraag

Welke maatregelen kunnen functioneel herstel bevorderen en mortaliteit voorkomen bij een kwetsbare oudere patiënt na een operatie voor een proximale femurfractuur?

Literatuurconclusies

Overgenomen van de module structurele medebehandeling van de richtlijn CGA bij consult en medebehandeling (NVKG, 2013).

|

Niveau 2 |

Het is aangetoond dat structurele medebehandeling dan wel structurele ortho-geriatrische medebehandeling door een geriatrisch expertise team bij patiënten ouder dan 70 jaar met proximale femurfractuur, leidt tot minder postoperatieve complicaties tijdens de ziekenhuisopname.

Bronnen (B: Fisher, 2006; Friedman, 2009; Lundstrum, 1998; Stenvall, 2007a; Stenvall, 2007b; Vidan, 2005) |

|

Niveau 3 |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat structurele ortho-geriatrische medebehandeling voor patiënten ouder dan 70 jaar met proximale femurfractuur de kans op herstel tot oorspronkelijk functieniveau en de kans op behoud van de mobiliteit vergroot.

Bronnen (B: Leung, 2011; Lundstrum, 1998; Shyu, 2008; Stenvall, 2007a; Swanson, 1998; Vidan, 2005) |

|

Niveau 3 |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat structurele ortho-geriatrische medebehandeling de kans op vallen en het valrisico verlaagt.

Bronnen (B: Stenvall, 2007b) |

|

Niveau 3 |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat structurele ortho-geriatrische medebehandeling voor patiënten ouder dan 70 jaar met proximale femurfractuur de kans op ontslag naar oorspronkelijke woonsituatie verhoogt.

Bronnen (B: Lundstrum, 1998; Stenvall, 2007b) |

|

Niveau 3 |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat structurele ortho-geriatrische medebehandeling voor patiënten ouder dan 70 jaar met proximale femurfractuur de kans op mortaliteit na 30 dagen en na één jaar vermindert.

Bronnen (B: Leung, 2011; Shyu, 2008) |

|

Niveau 3 |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat structurele geriatrische medebehandeling bij patiënten ouder dan 70 jaar met proximale femurfractuur het aantal opnamedagen in het ziekenhuis verkort.

Bronnen (B: Friedman, 2009; Naglie, 2003; Stenvall, 2007a; Stenvall, 2007b; Swanson, 1998;) |

|

Niveau 2 |

Het is aannemelijk/waarschijnlijk dat standaard geïntegreerde orthopedische en geriatrische zorg voor patiënten ouder dan 70 jaar met proximale femurfractuur de kans op overlijden in het ziekenhuis vermindert.

Bronnen (A2: Fisher, 2006; Vidan, 2005) |

NOTE: Voor bovenstaande conclusies is de bewijskracht beoordeeld met behulp van de EBRO-methodiek. Dit is in tegenstelling met wat in de methodiek voor de ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn beschreven staat. Dit komt doordat bovenstaande conclusies letterlijk zijn overgenomen van de richtlijn CGA bij consult en medebehandeling (NVKG, 2013).

Samenvatting literatuur

In total, ten articles studied the effects of co-treatment of geriatricians in frail older people. All studies were cohort studies comparing a pre-intervention with post-intervention cohort. Most studies (n=5) focused on fragility hip fractures (Bub, 2022; Fan, 2022; Hafner, 2021; Kalmet, 2019; Yee, 2022), other studies focused on vascular surgery (Natesan, 2022), spine surgery (Pernik, 2021), abdominal surgery (McDonald, 2018), gastrointestinal surgery (Giannotti, 2022), surgery for various cancer types (Shahrokni, 2022).

Description of the included studies

Bub (2022) conducted a retrospective chart review study in patients ≥65 years with low-energy hip fractures at a large urban academic tertiary centre in the USA. They evaluated whether the implementation of a geriatrics-focused orthopaedic and hospitalist co-management program improved perioperative outcomes, including time to operating room, length of stay, perioperative complications, and mortality. This was compared with a historical cohort, in which patients with hip fractures were admitted to either orthopaedics or hospitalist service with the other on board as a consultant. The co-management program consisted of a hospitalist (e.g., trained geriatrics comanager) who comanaged all patients. Additionally, team members from orthopaedics, hospital medicine, nursing, and geriatrics rounded together two times a day and discussed medical and surgical management as well as psychosocial and discharge issues. The intervention group consisted of 162 patients, and the control group of 128 patients.

Fan (2021) conducted a pre-post retrospective study in patients ≥60 years with fragility fractures at a level 1 trauma centre in China. They assessed the efficacy of a multidisciplinary team co-management program (n=241) on time-to-surgery, length of stay, and postoperative complications within 30-days, compared with the historical traditional care model (n=249). The multidisciplinary team co-management program involved orthopaedic surgeons, geriatricians, anaesthesiologists, specialists of the intensive care unit, and physiotherapists. In this program, the geriatrician managed comorbidities and polypharmacy to make patients clinically stable and ready for surgery. The historical traditional care model did not include geriatric expertise.

Giannotti (2022) conducted a pre-post retrospective study in patients aged ≥ 70 years admitted for elective gastrointestinal cancer surgery or palliative treatments and required a hospital stay of at least one day, in a hospital in Italy. They studied the effects of a geriatric co-management model (n=90) to a surgeon-led model (n=117) and assessed post-operative complications. The geriatric co-management model consisted of daily targeted geriatrician-led ward rounds focusing on older patients with cancer. Prior to surgery, patients received a CGA and frailty assessment. During the inpatient postoperative period, patients were followed by the same geriatrician in a consulting role, with the surgical team in a primary role. The geriatric co-management group included a daily board round led by a geriatrician who discussed the care management during the clinical sessions. The surgeon-led model consisted of optional referral for a preoperative CGA based on clinical judgement, not on a formal frailty screening team. During hospitalization and the perioperative phase, patients were assessed daily by the surgical team and medical consultants were called in as needed.

Hafner (2021) performed a retrospective single-centre cohort study in patients ≥70 years with fragility fractures in a university hospital in Germany. They studied the effects of an ortho-geriatric model (n=224) on complications, delirium, mortality, time-to-surgery, length of stay, and other clinical outcomes, compared with usual care (n=137) before implementation of the intervention. The ortho-geriatric model involved patients who were admitted to and treated at the trauma surgery ward, with the routine consultation of a geriatrician in an interdisciplinary ward round twice a week and an interdisciplinary team conference once a week. Moreover, representatives of nursing, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, and case management took part in the treatment process from admission until discharge.

Kalmet (2019) conducted a retrospective cohort study in patients ≥65 years with a surgically treated low-energy fracture in a university hospital in the Netherlands. They compared patient-reported outcomes, such as pain and quality of life, between patients treated in the context of a multidisciplinary clinical pathway (n=182) and patients receiving usual care before implementation of the intervention (n=216). Quality of life was measured using the SF-12. The SF-12 measures various aspects of physical and mental health from which physical composite score (PCS) and mental composite score (MCS) can be calculated, ranging from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 100 (Ware, 2002). The multidisciplinary clinical pathway involved an orthopaedic trauma surgeon, a geriatrician, an anaesthesiologist, and a physiotherapist. These disciplines are all actively involved in the decision-making process from presentation at the emergency department until discharge and other specialities could be involved when necessary.

McDonald (2018) performed a prospective cohort study in patients ≥85 years and patients ≥65 years at risk for complications who underwent elective abdominal surgery in a university hospital in the USA. They assessed clinical outcomes in patients receiving a collaborative intervention by surgery, geriatrics, and anaesthesia focused on perioperative health optimization (n=183) compared to a comparable group of patients before implementation of the intervention (n=143). The collaborative intervention consisted of a team including a geriatrician, geriatric resource nurse, social worker, program administrator, and nurse practitioner. These were all present during the preoperative visit and all participated in rounds on the in-patient geriatrics consult service.

Natesan (2022) performed a single-centre retrospective cohort study in patients ≥65 years, with one or more geriatric syndromes and one or more comorbidities, who were scheduled for vascular surgery or endovascular intervention in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. They studied the efficacy of a co-management model between geriatric medicine and vascular surgery services, on length of stay, readmission, mortality, and postoperative complications, compared to a retrospective similar cohort before implementation of the care model. The co-management model consisted of the geriatric team who visited patients once preoperative to optimize outcomes and postoperative on a daily basis to optimize comorbidity treatments and address postoperative complications early. Additionally, a practice geriatric nurse identified social support, caregiver stress, and rehabilitation potential. The intervention group included 198 patients and the control group consisted of135 patients.

Pernik (2021) conducted a retrospective cohort study in patients with an increased perioperative risk of adverse outcomes undergoing elective spine surgery in the USA. The study assessed the impact of an interdisciplinary perioperative intervention involving geriatrics, surgery, and anaesthesiology (n=147) compared to a matched historical control group treated with usual care (n=177) on delirium incidence, length of stay, and readmission rates. The interdisciplinary perioperative intervention consisted of a pre-operative assessment with a geriatrician, including a comprehensive assessment, which was communicated to the anaesthesia and surgical teams. Patients and families received specific education on delirium and delirium prevention. Approximately one or two weeks later, anaesthesia planning was performed in coordination with the geriatric and surgical teams. Postoperatively, patients were co-managed by the primary surgical and geriatric consult team daily until discharge. The geriatric team assisted with adherence to nonpharmacologic delirium prevention strategies, management of medical comorbidities, pain management, optimizing bowel and bladder function, nutritional status, avoidance of high-risk medications, administration of a daily delirium screen, and facilitating smooth transition to post-acute care.

Shahrokni (2020) conducted a retrospective cohort study in patients aged ≥ 75 years who underwent cancer related surgical treatment of various cancer types, and a hospital stay of at least 1 day. They studied the effects of a geriatric co-management model (n=1020) to a surgeon-led model (n=872), and assessed length of stay, 90-day mortality and adverse surgical outcomes within 30 days (major complications, readmission or emergency room visit). The geriatric co-management consisted of two phases: preoperative and postoperative care. Referral for pre-operative geriatric evaluation was based on the surgery teams’ clinical judgment. Preoperative evaluation consisted of a Rapid Fitness Assessment, discussion with the surgery and anaesthesiology team, and recommendations to optimize the patients’ status. Postoperatively, the geriatrics team visits all inpatients on day 1 and day 3, and further follow up if necessary. They assist with management of comorbid conditions, medication management, delirium-reducing interventions, stimulate early mobility, prevent complications and pain management. For the control group, the patients are not evaluated pre-operatively by a geriatrician and post-operatively only upon request.

Yee (2022) performed a prospective cohort study in patients ≥65 years with a low-energy hip fracture in three hospitals in Hong Kong. They studied the effect of an orthogeriatric co-management model on clinical outcomes (n=207), compared to a historical cohort (n=194) before implementation of the intervention (usual care). The orthogeriatric co-management model included a geriatrician during the postoperative phase, who co-managed the patient. Patients were co-managed by a geriatrician during combined ward rounds three times a week on the acute ward or in care of medical problems on the rehabilitation ward. The geriatrician actively reviewed all hip fracture patients to allow prompt diagnosis and management of medical complications, optimization of pain control and monitoring of comorbidities.

Results

Functional status

Postoperative mobilization

The cohort study of Hafner (2021) demonstrated that the number of patients with fragility fractures who were mobilized on the first day after surgery was statistically significantly (P<0.001) higher in the ortho-geriatric model compared with usual care before implementation of the intervention (Risk Ratio (RR) 1.52; 1.24-1.84).

In the cohort study of Pernik (2021) no difference was found in the mean number of days until walking in patients who underwent spine surgery (p=0.77; Mean Difference (MD)=0.0; 95% Confidence Interval (CI) not provided) between an interdisciplinary perioperative intervention compared with a historical usual care group.

Transfers (mobility)

In the study of Yee (2022) no statistically significant effect was found in transfer scores in patients with a fragility hip fracture between the orthogeriatric co-management model group and the historical cohort before implementation of the model (p=0.07; median (Interquartile range (IQR)) Intervention Group (IG) 12 (8) vs Control Group (CG) 9 (8); 95%CI not provided). The ability of patients to make a transfer was measured using the elderly mobility scale (EMS), which is a 20-point validated scale. A score >14 indicating an ability to perform a transfer alone and safely, a score between 10 and 14 indicating borderline in terms of safe mobility and independence in activities of daily living (ADL), and a score <10 indicating a high level of help with mobility and ADL.

Activities of Daily Living

The study of Yee (2022) demonstrated that use of an orthogeriatric co-management model increases the independence in ADL in patients with a fragility hip fracture, compared to a historical cohort before implementation of the model (p<0.001; median (IQR) IC 81 (27) vs CG 63.5 (28); 95%CI not provided). This study used the Modified Bartel ADL index (MBI), which is a 100-point validated scale. A lower score indicates more dependence and a higher score indicated more independence.

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (i-ADL)

No study reported the outcome instrumental activities of daily living.

Cognitive disorders

No study reported the outcome cognitive disorders (except for delirium, see: complications)

Quality of life

The cohort study of Kalmet (2019) assessed quality of life (QoL) using the Short Form 12 (SF-12), two years after surgery. No difference was found in overall QoL between patients with fragility fractures receiving a multidisciplinary clinical pathway and patients receiving usual care before implementation of the pathway (p=0.65; IG 47.9 ± 24.4 vs CG 45.4 ± 27.6, MD 2.5). They found no difference in physical QoL between patients with fragility fractures receiving a multidisciplinary clinical pathway and patients receiving usual care before implementation of the pathway (p=0.93; IG 36.3 ± 28.6 vs CG 35.8 ± 28.9, MD 0.5). They found no difference in mental QoL between patients with fragility fractures receiving a multidisciplinary clinical pathway and patients receiving usual care before implementation of the pathway (p=0.45; IG 59.5 ± 25.0 vs CG 54.9 ± 31.0, MD 4.6).

Complications

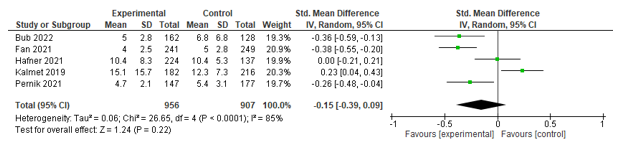

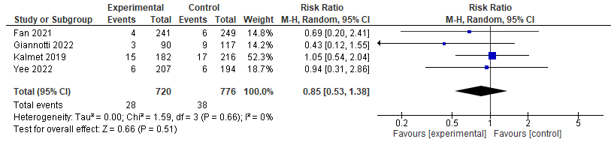

Six studies assessed the incidence of post-operative complications (<30 days). These studies were pooled, whereby a statistically significant effect between co-management and control in favour of co-management was found (RR 0.74 [0.56; 0.99]) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Forest plot depicting risk ratio for complications.

Delirium

Eight studies assessed post-operative delirium incidence, of which seven could be pooled. These studies could be pooled, but found no significant effect between co-management and control (RR 0.96; 0.53-1.75) (see Figure 2).

The pre-post study of Giannotti (2022) reported mean 4AT scores, of which a score of 5 or higher suggests delirium but is not diagnostic, and showed that 4AT scores were lower in the geriatric co-management group compared to control (p=0.03; 1.44 ± 2.62 vs. 2.19 ± 3.27).

Figure 2. Forest plot depicting risk ratio for delirium incidence.

Infections

Six studies reported on the incidence of infections. Five studies assessed urinary tract infection rates and could be pooled, and a significant effect was found between co-management and control in favour of co-management (RR 0.55; 0.31-0.99) (see Figure 3). Four of these studies also assessed the incidence of pneumonia, and could be pooled, and a significant effect was found between co-management and control in favour of co-management (RR 0.60; 0.42-0.85) (see Figure 4).

Figure 3. Forest plot depicting risk ratio for urinary tract infection.

Figure 4. Forest plot depicting risk ratio for pneumonia.

The pre-post study of Giannotti (2022) reported on the incidence of bacteriemia/sepsis and reported lower rates of bacteriemia/sepsis in the geriatric co-management group (p <0.005; RR 0.33; 0.14-0.76).

Falls

One study reported on in-hospital falls, but no effect was found.

The cohort study of Hafner (2021) found no difference in the incidence of in-hospital falls between the ortho-geriatric model and usual care before implementation of the intervention in patients with fragility fractures (p=0.292; IG 1.3% vs CG 0%; 95%CI not estimable).

Cardiopulmonary complications

Four studies reported on cardiopulmonary complications, including pulmonary complications, cardiac complications and myocardial infarction. No effect was found.

Pulmonary complications

The cohort study of Hafner (2021) found no difference in the incidence pulmonary complications between the ortho-geriatric model and usual care before implementation of the intervention in patients with fragility fractures (p=0.072; IG 17.9% vs CG 12.4%; RR1.44; 0.85-2.4).

Cardiac complications

The cohort study of Hafner (2021) found no difference in the incidence of cardiac complications between the ortho-geriatric model and usual care before implementation of the intervention in patients with fragility fractures (p=0.405; IG 8.0% vs CG 8.8%; RR0.91; 0.46-1.8).

The pre-post study of Giannotti (2022) found no difference in the incidence of cardiovascular complications between groups (p=0.434; IG 17.8% CG 21.4%)

Myocardial infarction

The cohort study of Bub (2022) found no difference in the incidence of myocardial infarction between a geriatrics-focused co-management program compared with a historical care model in patients with fragility hip fractures (p=1.000; IG 0.6% vs CG 0.0%; 95%CI not estimable).

The cohort study of Natesan (2022) found no difference in the incidence of myocardial infarction between a co-management model and a retrospective cohort in patients scheduled for vascular surgery or endovascular interventions (p=n/s; IG 6% vs CG 6%; RR 0.94 [0.39;2.27]).

The cohort study of Fan (2021) found no difference in the incidence of acute coronary syndrome between a multidisciplinary team co-management program and a historical traditional care model in patients with fragility fractures (p=0.299; IG 3.3% vs CG 5.2%; RR0.64 [0.27;1.50]).

Thromboembolic complications

Three studies reported on thromboembolic complications. No effect was found.

The cohort study of Bub (2022) found no difference in deep vein thrombosis incidence between a geriatrics-focused co-management program compared with a historical care model in patients with fragility hip fractures (p=1.000; IG 0.6% vs CG 0.8%; 95%CI not provided).

The cohort study of Fan (2021) found that a multidisciplinary team co-management program in patients with fragility fractures decreases deep venous thrombosis incidence compared with a historical traditional care model (p=0.049; IG 7.9% vs CG 12.9%; RR0.56; 0.32-0.97).

The cohort study of Bub (2022) found no difference in the incidence of pulmonary embolism between a geriatrics-focused co-management program compared with a historical care model in patients with fragility hip fractures (p=1.000; IG 0.6% vs CG 0.0%; 95%CI not estimable).

Neurological complications

Two studies reported on the effects of co-management programs on the incidence of Cerebral Vascular Incidents. No effect was found. One study reported on overall neurological complications and also found no effect.

The cohort study of Bub (2022) found no difference in the incidence of cerebral vascular accident between a geriatrics-focused co-management program compared with a historical care model in patients with fragility hip fractures (p=0.194; IG 0.0% vs CG 1.6%; 95%CI not provided).

The cohort study of Fan (2021) found no difference in the incidence of cerebral vascular accident between a multidisciplinary team co-management program and a historical traditional care model in patients with fragility fractures (p=0.802; IG 2.1% vs CG 2.4%; RR0.86; 0.26-2.78).

The pre-post study of Giannotti (2022) found no difference on overall neurological complications between groups (p=0.202; IG 16.7% vs. CG 24.8%).

Haemotological complications

The pre-post study of Giannotti (2022) found fewer haematological complications in the geriatric co-management group (p=0.31; IG 7.8% vs. CG 19.7%; RR0.40; 0.18-0.88)

Length of stay

Ten studies assessed length of stay (LOS). Five of these could be pooled, but no significant effect between co-management and control was found (SMD -0.15; -0.39-0.09) (see Figure 5). McDonald (2018), Yee (2022), and Shahrokni (2022) could not be included in the meta-analysis because only medians and interquartile ranges were provided, and Natesan (2022) could not be included because only means were provided.

The cohort study of McDonald (2018) found that a collaborative intervention decreases median length of stay in patients with abdominal surgery compared with care before implementation of the intervention (p<0.001; median difference -2.0 days; 95%CI 1.1 to 4.2).

The cohort study of Natesan (2022) found that a co-management model decreases mean length of stay compared with a retrospective cohort in patients scheduled for vascular surgery or endovascular interventions (p=0.01; MD -9.2; 95%CI not provided).

The cohort study of Yee (2022) found that an orthogeriatric co-management model group decreases length of stay in patients with fragility hip fractures compared with the historical cohort before implementation of the intervention (p<0.001; median difference -2.0; 95%CI not provided).

The cohort study of Shahrokni (2020) found that the geriatric co-management group had a longer length of stay than the surgeon-led model (p<0.001); median difference -1.0 day; 95%CI not provided).

The pre-post study of Giannotti (2022) found no difference between groups (p=0.506; median difference 0.0 day; 95% CI not provided).

Figure 5. Forest plot depicting standardized mean difference for length of stay.

Discharge destination

Discharge to a facility

Two studies assessed the amount of patients that were discharged to a facility, but both found no effect.

The cohort study of Bub (2022) found no difference in the amount of patients with fragility hip fractures who were discharged to a skilled nursing facility between a geriatrics-focused co-management program compared with a historical care model (p=0.197; IG 39.5% vs CG 28.1%; 95%CI not provided).

The cohort study of McDonald (2018) found no difference in the amount of patients with abdominal surgery who were discharged to a facility between patients that received a collaborative intervention and patients that received care before implementation of the intervention (p=0.26; IG 14.2% vs CG 18.9%; 95%CI 0.39-1.28).

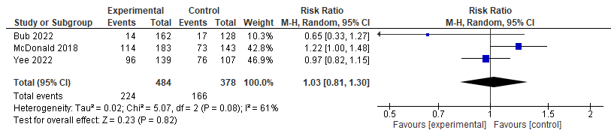

Living at home independently

Three studies assessed the amount of patients who returned home without assistance. After pooling of the results, no significant effect between co-management and control was found (RR 1.03; 0.81- 1.30) (see Figure 6). Of these, one study also assessed the amount of patients who used health services when returning home, no effect was found.

Figure 6. Forest plot depicting risk ratio for returning home (with self-care).

Readmission

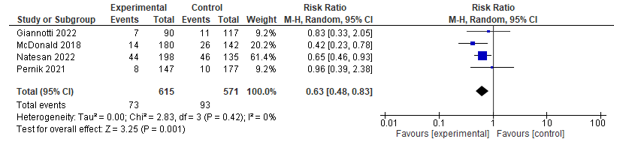

Four studies reported on readmission within different time frames. Two studies assessed 7-days readmission, of which one found no effect and the other found a positive effect in favour of co-management. One study assessed 28-days readmission, but found no difference between both groups. Three studies reported on 30-days readmission and could be pooled. A significant effect was found between co-management and control in favour of co-management (RR 0.61; 0.43-0.87) (see Figure 7). Lastly, one study assessed 90-days readmission, but found no effect.

7-days readmission

The cohort study of McDonald (2018) found that a collaborative intervention decreases 7-days readmission rates in patients with abdominal surgery compared with care before implementation of the intervention (p<0.001; IG 2.8% vs CG 9.9%; 95%CI 0.09-0.74).

The cohort study of Pernik (2021) found no difference in 7-days readmission rates in patients who underwent spine surgery between an interdisciplinary perioperative intervention compared with a historical usual care group (p>0.99; IG 2.1% vs CG 2.3%; RR0.9; 0.21-3.97).

28-days readmission

The cohort study of Yee (2022) found no difference in 28-days unplanned readmission rates in patients with fragility hip fractures between the orthogeriatric co-management model group and the historical cohort before implementation of the intervention (p=0.55; IG 12.6% vs CG 14.9%; 95%CI not provided).

30-days readmission

Four studies assessed the difference in 30-day readmission rates between groups, and a pooled effect in favour of geriatric co-management was found (RR0.63; 0.48-0.83) (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Forest plot depicting risk ratio for 30-days readmission.

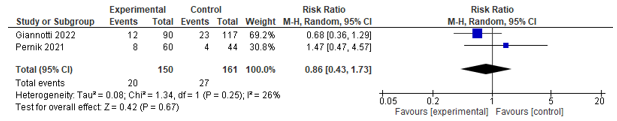

90-days readmission

Two studies assessed the difference in 90-day readmission rates, no difference was found between groups (See Figure 8).

Figure 8. Forest plot depicting risk ratio for 90-day readmission.

1-year readmission

The pre-post study of Giannotti (2022) found fewer rehospitalizations in the geriatric co-management group compared to the surgery-led group (p=0.058; IG 23.5% vs CG 35.9%; RR0.65; 0.42-1.02).

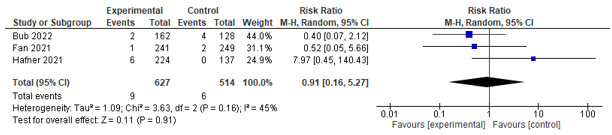

Mortality

Three studies assessed mortality on different time frames; four studies assessed 30-day mortality and could be pooled. However, no significant effect was found between co-management and control (RR 0.85; 0.53-1.38) (see Figure 9). Three studies assessed in-hospital mortality, and could be pooled. However, no significant effect between co-management and control was found (RR 0.91; 0.16-5.27) (see Figure 10). Aadditionally, two studies reported on 1-year mortality, and both found no difference.

Figure 9. Forest plot depicting risk ratio for 30-day mortality.

Figure 10. Forest plot depicting risk ratio for in-hospital mortality.

90-day mortality

The cohort study of Shahrokni (2020) found that patients in the geriatric co-management group were less likely to die within 90 days after surgical treatment (p<0.001; OR 0.43 96%CI 0.28-0.67).

The pre-post study of Giannotti (2022) found no difference between groups (p=0.89; RR1.06; 0.46-2.41)

1-year mortality

The cohort study of Yee (2022) found no difference in 1-year mortality rates in patients with fragility hip fractures between the orthogeriatric co-management model group and the historical cohort before implementation of the intervention (p=0.24; difference 3.3%; 95%CI -3.1% to 9.7%).

The cohort study of Kalmet (2019) found no difference in 1-year mortality rates between a multidisciplinary clinical pathway compared with usual care before implementation of the pathway in patients with fragility fractures (p=0.50; IG 33.5% vs CG 37.0%; RR0.90 [0.69;1.18]).

The pre-post study of Giannotti (2022) found no difference in 1-year mortality rates between groups (p= 0.15 IG18.9% vs. CG12.8%; RR1.60 [0.84;3.03])

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcomes started at Low because all included studies are observational (cohort) studies. The reasons for downgrading the evidence from ‘Low’ (cohort study) to ‘Very low’ are given below. When assessment for reasons to downgrade the evidence level led to the conclusion that no reason for downgrading was present, an assessment was made for any special strengths that would allow for an increase in the level of evidence.

Postoperative mobilization

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative mobilization was downgraded by 1 level because of conflicting results (inconsistency) and small study population (imprecision) to Very low.

Transfers

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure transfers was downgraded by 1 level because only one study was included in the analysis, and no effect was shown (imprecision), to Very low.

Activities of daily living

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure activities of daily living was downgraded by 1 level because only one small study was included in the analysis (imprecision) to Very low.

Instrumental activities of daily living

No evidence was found for this outcome.

Cognitive disorders

No evidence was found for this outcome.

Quality of life

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by 1 level because only one small study was included in the analysis and no effect was shown (imprecision) to Very low.

Complications

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure complications was not downgraded and remained at Low. There were no reasons to increase the level of evidence.

Delirium

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure delirium was downgraded by 1 level because of conflicting results (inconsistency), and no effect shown (imprecision).

Urinary tract infections

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure urinary tract infections was not downgraded and remained at Low. There were no reasons to increase the level of evidence.

Pneumonia

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pneumonia was not downgraded and remained at Low. There were no reasons to increase the level of evidence.

Sepsis

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure bacteraemia/sepsis was downgraded by 1 level because the sample size was too small (inconsistency).

In-hospital falls

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure in-hospital falls was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because only one small study was available for the analysis and no effect was shown (imprecision).

Pulmonary complications

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pulmonary complications was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because only one small study was available for analysis and no effect was shown (imprecision).

Cardiac complication

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cardiac complications was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because only one small study was available for analysis and no effect was shown (imprecision).

Myocardial infarction

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure myocardial infarction was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because the confidence interval includes the null effect (imprecision).

Thromboembolic complications

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure deep venous thrombosis was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because of conflicting results (inconsistency) and small study population without effect shown (imprecision).

Cerebral vascular accident

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cerebral vascular accident was downgraded because of study limitations (risk of bias), conflicting results (inconsistency) and because the confidence interval includes the null effect (imprecision).

Haematological complications

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure haematological complications was downgraded by 1 level because the sample size was too small (inconsistency).

Length of stay

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure length of stay was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because of conflicting results (inconsistency), and because the confidence interval includes the null effect (imprecision).

Discharge destination: facility

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure discharge destination was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because the analysis only includes one study and no effect is shown (imprecision).

Discharge destination: living at home independently

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure living at home independently was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because of conflicting results (inconsistency), and wide 95%CI including the null effect (imprecision).

7-days readmission

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 7-days readmission was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because of a small population size and no effect was shown (imprecision).

28-days readmission

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 28-days readmission was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because only one study was available for analysis (imprecision).

30-days readmission

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 30-days readmission was not downgraded and remained at Low. There were no reasons to increase the level of evidence.

90-days readmission

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 90-days readmission was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because of conflicting results (inconsistency) and no effect was found (imprecision).

1-year readmission

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 1-year readmission was downgraded by 1 level because the sample size was too small (inconsistency).

In-hospital mortality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure in-hospital mortality was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because of conflicting results (inconsistency), and wide 95%CI including the null effect (imprecision).

30-day mortality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 30-day mortality was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because of conflicting results (inconsistency), and wide 95%CI including the null effect (imprecision).

90-day mortality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 30-day mortality was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because of conflicting results (inconsistency), and wide 95%CI (imprecision).

1-year mortality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 1-year mortality was downgraded by 1 level to Very low because the study population was small, and no effect was found (imprecision).

Overgenomen zoekvraag

De zoekvraag en samenvatting van de literatuur uit de module ‘Herstelmaatregelen na proximale femurfractuur’ uit 2016 is toegevoegd, omdat voor de literatuursearch bij de nieuwe richtlijn studies geïncludeerd zijn vanaf 2016. De bewijskracht van alle eerdere studies is echter van blijvende relevantie voor met name de oudere patiënten met een proximale femurfractuur.

Uitgangsvraag

Welke maatregelen kunnen functioneel herstel bevorderen en mortaliteit voorkomen bij een kwetsbare oudere patiënt na een operatie voor een proximale femurfractuur?

Literatuurconclusies

Overgenomen van de module structurele medebehandeling van de richtlijn CGA bij consult en medebehandeling (NVKG, 2013).

|

Niveau 2 |

Het is aangetoond dat structurele medebehandeling dan wel structurele ortho-geriatrische medebehandeling door een geriatrisch expertise team bij patiënten ouder dan 70 jaar met proximale femurfractuur, leidt tot minder postoperatieve complicaties tijdens de ziekenhuisopname.

Bronnen (B: Fisher, 2006; Friedman, 2009; Lundstrum, 1998; Stenvall, 2007a; Stenvall, 2007b; Vidan, 2005) |

|

Niveau 3 |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat structurele ortho-geriatrische medebehandeling voor patiënten ouder dan 70 jaar met proximale femurfractuur de kans op herstel tot oorspronkelijk functieniveau en de kans op behoud van de mobiliteit vergroot.

Bronnen (B: Leung, 2011; Lundstrum, 1998; Shyu, 2008; Stenvall, 2007a; Swanson, 1998; Vidan, 2005) |

|

Niveau 3 |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat structurele ortho-geriatrische medebehandeling de kans op vallen en het valrisico verlaagt.

Bronnen (B: Stenvall, 2007b) |

|

Niveau 3 |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat structurele ortho-geriatrische medebehandeling voor patiënten ouder dan 70 jaar met proximale femurfractuur de kans op ontslag naar oorspronkelijke woonsituatie verhoogt.

Bronnen (B: Lundstrum, 1998; Stenvall, 2007b) |

|

Niveau 3 |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat structurele ortho-geriatrische medebehandeling voor patiënten ouder dan 70 jaar met proximale femurfractuur de kans op mortaliteit na 30 dagen en na één jaar vermindert.

Bronnen (B: Leung, 2011; Shyu, 2008) |

|

Niveau 3 |

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat structurele geriatrische medebehandeling bij patiënten ouder dan 70 jaar met proximale femurfractuur het aantal opnamedagen in het ziekenhuis verkort.

Bronnen (B: Friedman, 2009; Naglie, 2003; Stenvall, 2007a; Stenvall, 2007b; Swanson, 1998;) |

|

Niveau 2 |

Het is aannemelijk/waarschijnlijk dat standaard geïntegreerde orthopedische en geriatrische zorg voor patiënten ouder dan 70 jaar met proximale femurfractuur de kans op overlijden in het ziekenhuis vermindert.

Bronnen (A2: Fisher, 2006; Vidan, 2005) |

NOTE: Voor bovenstaande conclusies is de bewijskracht beoordeeld met behulp van de EBRO-methodiek. Dit is in tegenstelling met wat in de methodiek voor de ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn beschreven staat. Dit komt doordat bovenstaande conclusies letterlijk zijn overgenomen van de richtlijn CGA bij consult en medebehandeling (NVKG, 2013).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following primary question: What is the effect on post-operative outcomes of co-management during post-operative care by a health care professional (HCP) with geriatric expertise and the surgical team compared to treatment during post-operative care by the surgical team alone in frail elderly patients?

P: Frail older people (≥65 years) who have undergone surgery

I: Post-operative co-management with an HCP with geriatric expertise

C: No post-operative co-management with an HCP with geriatric expertise

O: Functional status, quality of life, complications, readmissions, mortality, length of stay, costs

Functional status includes mobility, transfers, Activities of Daily Living (ADL), Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (iADL), living independently at home and cognitive impairment.

Complications include delirium, infection, falls, cardiopulmonary complications, neurological complications and thromboembolic complications.

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered all outcome measures relevant in the patient-centred decision-making process. Whether an outcome measure is critical or important depends on the individual patient, so the working group did not distinguish critical or important outcome measures.

Search and select (methods)

A search from 2018 until September 6th, 2022 was conducted in the following databases: Embase and Ovid/Medline. The detailed search strategy is depicted in Appendix 1. The systematic search resulted in 518 records after removing duplicates. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

Systematic review, randomized controlled trial (RCT), or cohort study;

Written in English or Dutch language;

Describing the effects of co-treatment with a geriatrician/geriatric team in frail older people.

One hundred and twenty-two articles were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 112 articles were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion in Appendix 2), and ten studies were included.

Results

Ten studies were included in the analysis of literature. Important study characteristics are summarized in Appendix 3 and results from the pooled outcomes are summarized in the evidence table in Appendix 4. The assessment of risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias table (see Appendix 5) and the GRADE assessment in Appendix 6.

Overgenomen zoekvraag

De zoekvraag en samenvatting van de literatuur uit de module ‘Herstelmaatregelen na proximale femurfractuur’ uit 2016 is toegevoegd, omdat voor de literatuursearch bij de nieuwe richtlijn studies geïncludeerd zijn vanaf 2016. De bewijskracht van alle eerdere studies is echter van blijvende relevantie voor met name de oudere patiënten met een proximale femurfractuur.

Uitgangsvraag

Welke maatregelen kunnen functioneel herstel bevorderen en mortaliteit voorkomen bij een kwetsbare oudere patiënt na een operatie voor een proximale femurfractuur?

Zoeken en selecteren

Voor deze vraag is gekeken naar de systematische literatuuranalyse die werd uitgevoerd voor de module structurele medebehandeling van de richtlijn CGA bij consult en medebehandeling (NVKG, 2013). De vraagstelling voor deze literatuuranalyse is: Heeft structurele geriatrische medebehandeling een meerwaarde ten opzichte van de gebruikelijke zorg op een niet geriatrische afdeling?

Er is alleen gekeken naar de studies in deze literatuuranalyse die betrekking hebben op patiënten met een proximale femurfractuur. Deze studies kijken naar de effectiviteit van geriatrische medebehandeling, waar de meervoudige geriatrische interventie deel van uitmaakt. De meervoudige geriatrische interventie in deze studies bestaat uit een aantal enkelvoudige interventies die in aard en aantal per studie verschillen. Om deze reden is besloten om geen aanvullende systematische literatuuranalyse te verrichten naar de effectiviteit van de enkelvoudige geriatrische interventies afzonderlijk.

Referenties

- American College of Surgeons. Optimal resources for geriatric surgery; 2019 standards. 2019. https://www.facs.org/media/yldfbgwz/19_re_manual_gsv-standards_digital-linked-pdf-1.pdf

- Baji P, Patel R, Judge A, Johansen A, Griffin J, Chesser T, Griffin XL, Javaid MK, Barbosa EC, Ben-Shlomo Y, Marques EMR, Gregson CL; REDUCE Study Group. Organisational factors associated with hospital costs and patient mortality in the 365 days following hip fracture in England and Wales (REDUCE): a record-linkage cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023 Aug;4(8):e386-e398. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(23)00086-7. Epub 2023 Jul 10. PMID: 37442154.

- Breda K, Keller MS, Gotanda H, Beland A, McKelvey K, Lin C, Rosen S. Geriatric fracture program centering age-friendly care associated with lower length of stay and lower direct costs. Health Serv Res. 2023 Feb;58 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):100-110. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.14052. Epub 2022 Sep 2. PMID: 36054014; PMCID: PMC9843078.

- Bub C, Stapleton E, Iturriaga C, Garbarino L, Aziz H, Wei N, Mota F, Goldin ME, Sinvani LD, Carney MT, Goldman A. Implementation of a Geriatrics-Focused Orthopaedic and Hospitalist Fracture Program Decreases Perioperative Complications and Improves Resource Utilization. J Orthop Trauma. 2022 Apr 1;36(4):213-217. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000002258. PMID: 34483320.Centre for Perioperative Care. Guideline for Perioperative Care for People Living with Frailty Undergoing Elective and Emergency Surgery. 2021. https://cpoc.org.uk/sites/cpoc/files/documents/2021-09/CPOC-BGS-Frailty-Guideline-2021.pdf

- Cizginer S, Prohl EG, Monteiro JFG, Yildiz F, Jones RN, Schechter S, Patterson R, Klipfel A, Katlic MR, Daiello LA, Mujahid N, Neupane I, Cioffi WG, Ducharme M, Vrees MD, McNicoll L. Integrated postoperative care model for older colorectal surgery patients improves outcomes and reduces healthcare costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023 May;71(5):1452-1461. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18216. Epub 2023 Jan 31. PMID: 36721263.

- Fan J, Lv Y, Xu X, Zhou F, Zhang Z, Tian Y, Ji H, Guo Y, Yang Z, Hou G. The Efficacy of Multidisciplinary Team Co-Management Program for Elderly Patients With Intertrochanteric Fractures: A Retrospective Study. Front Surg. 2022 Feb 24;8:816763. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2021.816763. PMID: 35284470; PMCID: PMC8907576.

- Giannotti C, Massobrio A, Carmisciano L, Signori A, Napolitano A, Pertile D, Soriero D, Muzyka M, Tagliafico L, Casabella A, Cea M, Caffa I, Ballestrero A, Murialdo R, Laudisio A, Incalzi RA, Scabini S, Monacelli F, Nencioni A. Effect of Geriatric Comanagement in Older Patients Undergoing Surgery for Gastrointestinal Cancer: A Retrospective, Before-and-After Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022 Nov;23(11):1868.e9-1868.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.03.020. Epub 2022 May 13. PMID: 35569527.

- Hafner T, Kollmeier A, Laubach M, Knobe M, Hildebrand F, Pishnamaz M. Care of Geriatric Patients with Lumbar Spine, Pelvic, and Acetabular Fractures before and after Certification as a Geriatric Trauma Center DGU®: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021 Jul 31;57(8):794. doi: 10.3390/medicina57080794. PMID: 34441000; PMCID: PMC8398181.

- Kalmet PHS, de Joode SGCJ, Fiddelers AAA, Ten Broeke RHM, Poeze M, Blokhuis T. Long-term Patient-reported Quality of Life and Pain After a Multidisciplinary Clinical Pathway for Elderly Patients With Hip Fracture: A Retrospective Comparative Cohort Study. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2019 Jun 6;10:2151459319841743. doi: 10.1177/2151459319841743. PMID: 31218092; PMCID: PMC6557012.

- McDonald SR, Heflin MT, Whitson HE, Dalton TO, Lidsky ME, Liu P, Poer CM, Sloane R, Thacker JK, White HK, Yanamadala M, Lagoo-Deenadayalan SA. Association of Integrated Care Coordination With Postsurgical Outcomes in High-Risk Older Adults: The Perioperative Optimization of Senior Health (POSH) Initiative. JAMA Surg. 2018 May 1;153(5):454-462. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513. PMID: 29299599; PMCID: PMC5875304.

- Miura LN, DiPiero AR, Homer LD. Effects of a geriatrician-led hip fracture program: improvements in clinical and economic outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009 Jan;57(1):159-67. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02069.x. Epub 2008 Nov 18. PMID: 19054192.

- Natesan S, Li JY, Kyaw KK, Soh Z, Yong E, Hong Q, Zhang L, Chong LRC, Tan GWL, Chandrasekar S, Lo ZJ. Effectiveness of Comanagement Model: Geriatric Medicine and Vascular Surgery. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022 Apr;23(4):666-670. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.10.022. Epub 2021 Nov 30. PMID: 34861223.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Hip fracture: management. Clinical guideline [CG124]. 06 January 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg124/chapter/Recommendations

- Pernik MN, Deme PR, Nguyen ML, Aoun SG, Adogwa O, Hall K, Stewart NA, Dosselman LJ, El Tecle NE, McDonald SR, Bagley CA, Wingfield SA. Perioperative Optimization of Senior Health in Spine Surgery: Impact on Postoperative Delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021 May;69(5):1240-1248. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17006. Epub 2020 Dec 31. PMID: 33382460.

- Saur NM, Davis BR, Montroni I, Shahrokni A, Rostoft S, Russell MM, Mohile SG, Suwanabol PA, Lightner AL, Poylin V, Paquette IM, Feingold DL; Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Evaluation and Management of Frailty Among Older Adults Undergoing Colorectal Surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022 Apr 1;65(4):473-488. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000002410. PMID: 35001046.

- Shahrokni, A., Tin, A., Sarraf, S., Alexander, K., Sun, S., Jung Kim, S., McMillan, S., Yulico, H., Amirnia, F., Downey, R., Vickers, A.J. & Korc-Grodzicki, B. (2020). Association of Geriatric Comanagement and 90-Day Postoperative Mortality Among Patients Aged 75 Years and Older with Cancer. JAMA network open. 8 doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9265

- Tarazona-Santabalbina FJ, Llabata-Broseta J, Belenguer-Varea Á, Álvarez-Martínez D, Cuesta-Peredo D, Avellana-Zaragoza JA. A daily multidisciplinary assessment of older adults undergoing elective colorectal cancer surgery is associated with reduced delirium and geriatric syndromes. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019 Mar;10(2):298-303. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2018.08.013. Epub 2018 Sep 11. PMID: 30217699.

- Van Heghe A, Mordant G, Dupont J, Dejaeger M, Laurent MR, Gielen E. Effects of Orthogeriatric Care Models on Outcomes of Hip Fracture Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2022 Feb;110(2):162-184. doi: 10.1007/s00223-021-00913-5. Epub 2021 Sep 30. PMID: 34591127; PMCID: PMC8784368.

- Vilans. Stappenplan - Samen beslissen met kwetsbare ouderen. 2018. https://www.vilans.nl/kennis/stappenplan-samen-beslissen-met-ouderen

- Ware, J., Kosinski, M., Turner-Bowker, D., & Gandek, B. SF-12: How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. 1995. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/John-Ware-6/publication/291994160_How_to_score_SF-12_items/links/58dfc42f92851c369548e04e/How-to-score-SF-12-items.pdf

- Yee DKH, Lau TW, Fang C, Ching K, Cheung J, Leung F. Orthogeriatric Multidisciplinary Co-Management Across Acute and Rehabilitation Care Improves Length of Stay, Functional Outcomes and Complications in Geriatric Hip Fracture Patients. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2022 Apr 11;13:21514593221085813. doi: 10.1177/21514593221085813. PMID: 35433103; PMCID: PMC9006372.

- <strong>Referenties Overgenomen zoekvraag

- Aloia JF. Clinical Review: The 2011 report on dietary reference intake for vitamin D: where do we go from here? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Oct;96(10):2987-96. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0090. Epub 2011 Jul 27.

- Aspray TJ, Bowring C, Fraser W, et al. National osteoporosis society vitamin D guideline summary. Age Ageing. 2014;43(5):592-5.

- Avenell A, Mak JC, O'Connell D. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post-menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD000227.

- Bacon CJ, Gamble GD, Horne AM, et al. High-dose oral vitamin D3 supplementation in the elderly. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20(8):1407-15.

- Beaudart C, Buckinx F, Rabenda V, et al. The effects of vitamin D on skeletal muscle strength, muscle mass, and muscle power: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(11):4336-45.