Aanwezigheid van naasten

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van aanwezigheid van naasten voor het comfort van IC-patiënten?

Aanbeveling

Faciliteer aanwezigheid van naasten bij alle patiënten op de Intensive Care.

Overweeg ten aanzien van naasten:

- Ruime bezoektijden

- Aanwezigheid bij de visite

- Aanwezigheid en/of participatie bij zorg- en mobilisatiemomenten

- Mogelijkheid tot rooming-in

- Mogelijkheid tot aanwezigheid bij procedures en ingrepen (inclusief reanimaties)

- Mogelijkheid van bezoek van (jonge) kinderen op de IC

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Gekeken naar de conclusies op basis van de literatuur, waren er alleen data beschikbaar voor het effect van familie-aanwezigheid op ligduur op de IC, delier, mortaliteit en angst/stress. Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat ligduur op de IC was het gevonden effect niet klinisch relevant in het voor- of nadeel van flexibele bezoekuren ten opzichte van beperkte bezoekuren. De bewijskracht van de literatuurconclusie is echter laag, dit vanwege de beperkingen van de studie die hebben geleid tot hoog risico op bias. Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten slaap en sedatie/agitatie score en pijn was geen bewijs beschikbaar. Dit maakt de overall bewijskracht zeer laag. Hiermee kunnen de cruciale uitkomstmaten geen richting geven aan de besluitvorming over het effect van familie-aanwezigheid op de IC.

Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten delier, mortaliteit en angst/stress waren wel data beschikbaar. Voor alleen delier werd een klinisch relevant effect gevonden in het voordeel van de interventie met flexibele bezoekuren voor familie ten opzichte van beperkte bezoekuren voor familie op de IC. Voor mortaliteit en angst/stress waren de effecten uit de gevonden studies tegenstrijdig, waardoor het overall effect onduidelijk is. Mede hierdoor was de bewijskracht van de gevonden effecten laag. Daarnaast speelden de beperkingen van de studies (risico op bias) en lage patiënt aantallen een rol hierin. Hiermee geven de belangrijke uitkomstmaten ook geen richting aan de besluitvorming over het effect van familie-aanwezigheid op de IC.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

(Inter)nationale intensive care richtlijnen (o.a. Davidson, 2017 en Vanhoy, 2017) en Stichting FCIC en patiëntenorganisatie IC Connect benadrukken het belang van “familie en patiëntgerichte zorg (Family-Patient-Centered-Care: FPCC).” Centraal hierin staan zowel het betrekken van de patiënt en zijn familie bij de behandeling als het bieden van emotionele ondersteuning aan patiënt en familie. Het is de uitdrukkelijke wens van families om hun geliefde vaak te kunnen zien. Onderzoek laat zien dat familie meer tevreden zijn met de behandeling van hun geliefde als zij meer betrokken worden bij de behandeling en de patiënt vaker mogen zien (Nasar, 2018; Rosa, 2019; Davidson, 2017). Daarnaast hebben familieleden significant minder last van angst en depressie wanneer zij hun geliefde vaker mogen zien (Nasar, 2018; Rosa, 2019; Davidson, 2017). Voor de patiënt zijn er geen negatieve effecten aangetoond van deze interventie. Zo lieten verschillende studies geen toename zien van infecties bij de patiënt (Rosa, 2019; Fumagalli, 2006; Rosa, 2017; Malacarne, 2011). Er is geen achterbanraadpleging gehouden m.b.t. voorkeuren van patiënten. Echter bij lotgenotencontact is het belang van aanwezigheid van naasten én kinderen tijdens de IC-opname een steeds terugkomend item.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Het ruimer toelaten van familie bij patiënten op de Intensive Care zal naar verwachting weinig extra kosten met zich meebrengen. Hoewel vaak wordt gedacht dat het ruimer toelaten van familie meer tijd kost voor behandelend artsen en verpleegkundigen, laten vele studies zien dat dit niet het geval is. Rosa en collega’s toonden aan dat ruimere bezoekuren geen toename gaven van burn-out klachten bij verpleegkundigen (Rosa, 2019). Studies geven tegenstrijdige resultaten ten aanzien van een toename van visiteduur bij aanwezigheid van familie (Au 2018, Gupta 2017, Ladak 2013). Voor patiënten waarbij het nodig is dat ook bezoek beschermende kleding (isolatie) dient te dragen zou een toename kunnen gelden van kosten door toename van gebruik van beschermende kleding.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Ruime bezoekuren, aanwezigheid van naasten bij de visite, mogelijkheid tot aanwezigheid bij procedurele ingrepen, rooming-in, het helpen bij zorg- en mobilisatie

momenten en de mogelijkheid om (jonge) kinderen op bezoek te laten komen, zijn manieren waarop familie-aanwezigheid kan worden bevorderd. Er zijn verschillende barrières tegen FPCC, zo kan er gebrek aan begrip zijn wat gedaan moet worden om FPCC te bewerkstelligen en kunnen er organisatorische, individuele en interprofessionele barrières zijn. (Kiwanuka 2019). Individuele organisaties zullen deze barrières moeten onderzoeken en aanpakken om familie aanwezigheid te bevorderen. Het opstellen van protocollen en scholen van personeel zijn hierbij van belang. Dit vraagt tijdsinvestering. Voor familieleden die ver van het ziekenhuis wonen of niet de financiële middelen hebben om de patiënt regelmatig te bezoeken kan het niet mogelijk zijn vaker aanwezig te zijn bij hun familielid op de IC, voor deze families zou de mogelijkheid tot rooming-in, overnachten in of nabij het ziekenhuis (Ronald Mcdonald huis) mogelijk moeten zijn.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Hoewel de bewijskracht voor het voordeel van meer familie aanwezigheid bij patiënten op de IC op het verminderen van pijn, delier, angst en depressieklachten laag is, zijn er wel voordelen voor de familie zonder nadelen voor de patiënt of het Intensive Care team.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Angst en discomfort zijn vaak aanwezig bij patiënten op de Intensive Care en worden frequent bestreden met additionele sedatie of pijnstilling. Echter, deze medicamenten hebben negatieve bijwerkingen, zoals ademdepressie, inactiviteit, verlies van spierkracht en van oriëntatie. Non-farmacologische adjuvantia hebben deze nadelige bijwerkingen niet en zouden comfort kunnen bieden met een sneller herstel. Eén van de drie meest voorkomende en praktisch toepasbare interventies is de aanwezigheid van naasten op de Intensive Care. De steun van familie of een geliefde op momenten van stress of pijn biedt comfort zou zo de benodigde hoeveelheid sedatie of pijnstilling kunnen verminderen. Daarnaast zou de vertrouwde aanwezigheid van naasten tot minder desoriëntatie van een patiënt kunnen leiden. Mogelijk dat familie-aanwezigheid hierdoor leidt tot een kortere IC-opnameduur, betere slaap, minder angst en stress, minder delirium en indirect een lagere mortaliteit

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

2.1 Length of ICU stay (crucial)

|

Low GRADE |

Flexible family visitation may result in little to no difference in length of ICU stay when compared with restricted family visitation for ICU patients.

Sources: Rosa, 2019 |

2.2 Sleep and sedation/agitation score (crucial); 2.3 Pain (crucial)

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of family presence sleep and sedation/agitation score and pain when compared with usual care in ICU patients.

Sources: - |

2.4 Anxiety/stress (important)

|

Low GRADE |

Family presence may result in little to no difference in anxiety/stress when compared with usual care in ICU patients.

Sources: Nassar, 2018 (Fumagalli, 2006; Fumagalli, 2013); Jaberi, 2020 |

2.5 Delirium (important)

|

Low GRADE |

Family presence visitation may result in a reduction of delirium incidence when compared with restricted family visitation for ICU patients.

Sources: Nassar, 2018 (Ehbali-Babadi, 2017); Rosa, 2019 |

2.6 Mortality (important)

|

Low GRADE |

Family presence may result in little to no difference in mortality when compared with usual care for ICU patients.

Sources: Nasser, 2018 (Malacarne, 2011; Fumagalli, 2006) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Nassar (2018) described a systematic review and meta-analysis about the effect of flexible versus restrictive visiting policies in ICUs. A systematic literatures search was performed in three databasese (Medline (via PubMed), Scopus and Web of Science) for observational studies and RCTs published until August 3, 2017. Studies were included if 1) flexible and restrictive visiting policies were compared; 2) at least one of the following outcome measures were evaluated: patient-related outcomes, family member-related outcomes and/or ICU professional-related outcomes. A total of 16 studies were included in the systematic review, from which seven were included in the meta-analyses. In order to answer the clinical question for this module, only the RCTs were extracted from the review (Eghbali-Babadi, 2017; Fumagalli, 2013; Fumagalli, 2006; Malacarne, 2011). The effects were evaluated on anxiety/stress, delirium incidence and ICU mortality

Jaberi (2020) described a double-blind randomized controlled trial about the effect of family presence during teaching rounds in the cardiac ICU. During these rounds, patients were visited by professors, trainee students, medical interns, assistants and nursing staff/head nurses for 3-45 minutes per patient. In total, 60 patients (mean age 62.1y; 48.3% female) were randomly allocated to two groups. In the intervention group (n=30) family members were present and participated during teaching rounds. In the control group (n=30) teaching rounds were performed without presence and participation of family members. The effects were evaluated on anxiety/stress (assessed with the STAI) score) after the intervention.

Rosa (2019) described a randomized controlled trial about the effect of flexible family visitation on delirium in the ICU. In total, 1685 patients (mean age 58.5y; 47.2% female) were randomly allocated to two groups. The intervention group (n=837) received flexible visitation (up to 12 hours per day) supported by family education. The control group (n=848) received usual restricted visitation (median, 1.5 hours per day). The effects were evaluated on ICU length of stay and delirium incidence.

Results

2.1 ICU length of stay (crucial)

Rosa (2019) assessed ICU length of stay as an outcome. Data resulted in an equal median duration of five days (range 3.0 – 8.0 days) both groups (the flexible and the restricted visitation group).

The level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome ICU length of stay started at high because it was based on an RCT, but was downgraded by two levels due to the susceptibility to to recruitment bias and undeclared losses to follow-up (risk of bis, -2). The final level is low.

2.2 Sleep (crucial); 2.3 Pain (crucial)

None of the studies assessed sleep or pain as an outcome

2.4 Anxiety/stress (important)

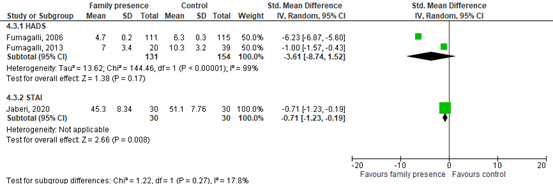

Fumagalli (2006), Fumagalli (2013) and Jaberi (2020) assessed anxiety stress as an outcome by the results on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (range 0-10, lower score means better outcome) and the STAI (range 20-80, lower score means better outcome). Data of Fumagalli (2006) and Fumagalli (2013) resulted in a MD of -2.20 (95% CI -3.80 to -0.61). This difference was clinically relevant in favour of family presence. Results are shown in figure 6.1.

Data of Jaberi (2020) resulted in a MD of -5.80 (95% CI -9.88 to -1.72). This difference was not clinically relevant. Results are shown in figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1. Forest plot comparing the effect of a family presence intervention compared to usual care on anxiety stress (assessed with the HADS or the STAI).

The level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome anxiety stress started at “high” because it was based on an RCT, but was downgraded by two levels due to methodological heterogeneity (inconsistency, -1) and limited number of included patients (imprecision, -1). The final level is low.

2.5 Delirium

Eghbali-Babadi (2017) Rosa (2019) assessed delirium incidence as an outcome (n=349). Data of Eghbali-Babadi (2017) resulted in a delirium incidence of 7/34 (20.6%) in the family-patient communication group, compared to 15/34 (44.1%) in the routine care group (RR of 0.73 (95% CI 0.38 to 1.14). Data of Rosa (2019) resulted in a delirium incidence of 157/831 (18.9%) in the flexible visiting policy group, compared to 170/845 (20.1) in the restricted vising policy group (RR of 0.94 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.14). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of the flexible vising policy group.

The level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome delirium started at high because it was based on RCTs, but was downgraded by two levels due to the susceptibility to recruitment bias and undeclared losses to follow-up (risk of bis, -2). The final level is low.

2.6 Mortality (important)

Fumagalli (2006) and Malacarne (2011) assessed mortality as an outcome. Data of Malacarne (2011) resulted in an ICU mortality rate of 75/261 (28.7%) in the family presence group compared to 66/269 (24.5%) in the control group (RR of 1.17 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.56). This difference was clinically relevant in favour of the control group, however, could be delclared by high incidence of cardiovascular complications in the intervention group. Data of Fumagalli (2006) resulted in a hospital mortality rate of 2/111 (1.8%) in the unrestricted visiting policy group compared to 6/115 (5.2%) in the restricting visiting policy group (RR of 0.35 (95% CI 0.07 to 1.67). This difference was clinically relevant in favour of the unrestricted visiting policy group.

The level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome mortality started at high because it was based on RCTs, but was downgraded by two levels due to statistical heterogeneity (inconsistency, -1) and crossing the border of clinical relevance (-1, imprecision). The final level is low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effect of family presence in comparison with no intervention or care as usual on length of ICU stay, sleep and sedation scores, pain, anxiety/stress, delirium, and mortality in adult ICU patients?

P: Adult ICU patients (awake and sedated).

I: Family presence: Any type of attention by family members, spouse or partner.

C: No intervention or care as usual.

O: Length of ICU stay, sleep and sedation/agitation score, pain, anxiety/stress, delirium, and mortality.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered length of ICU stay, sleep and sedation/agitation score and pain as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and anxiety/stress, delirium, and mortality as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- ICU length of stay: The number of days spent on the ICU.

- Sleep and sedation/agitation score: Measured with the Richards-Campbell Sleep Questionnaire (RCSQ), NRS sleep scale or the Richmond agitation and sedation scale (RASS).

- Pain: measured with the numeric rating scale (NRS), visual analogue scale (VAS) or behavioral pain scale (BPS).

- Anxiety/stress: Measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Faces Anxiety Scale, Environmental Stressor Questionnaire (ESQ), State Trait Anxiety Inventory score (STAI).

- Delirium: The number of participants who were diagnosed with delirium during IC/hospital stay.

- Mortality: The number of patients who died during IC/hospital stay.

The working group defined the following differences as minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

- ICU length of stay: A difference of two days between groups.

- Sleep and sedation/agitation score: A difference of 10mm points on the RCSQ; a difference of 1 point on the NRS; a difference of 2 points on the RASS.

- Pain: A difference of 1 point on the NRS (range 0-10), provided that the score is >4 ; a difference of 10 points on the VAS (range 0-100), provided that the score is >40 or a score of ≥ 60 for dichotomous outcomes; a difference of 2 points on the BPS (range 0-12), provided that the score >5.

- Anxiety/stress: A difference of 2 points on the HADS (range 0-10) or a difference of 25% in relative risk of a score >8; a difference of 2 points on the Faces Anxiety Scale (range 0-10); a difference of 40 points on the ESQ (range 0-200) or a difference of 14 points on the STAI (range 20-80).

- Delirium: A difference of 5% in delirium incidence (RR ≤ 0.95 RR ≥ 1.05).

- Mortality: A difference of 3% based on the SDD-trial (Smet, 2009) (RR ≤ 0.97, RR ≥ 1.03).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from the beginning of the databases until April, 1st 2021. One search has been executed for nonpharmacological interventions in general. The detailed search strategy can be found under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 2842 hits. For this subquestion, studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Describing adult patients at the ICU;

- Describing any type of attention by family members as an intervention;

- Study design: randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or systematic reviews (SRs) of RCTs with a detailed description of included studies, a risk-of-bias judgement; a detailed description of the literature search strategy and included a meta-analysis;

- Articles published in English or Dutch;

- Describing at least one of the following outcome measures: length of ICU stay, sleep and sedation/agitation score, pain, anxiety/stress, delirium, or mortality.

- At least 20 patients included in the study.

A total of 18 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening, including 17 SRs and one RCT. After reading the full texts, 17 SRs were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and one RCT was included (Jaberi, 2020). In addition, one systematic review (Nassar, 2018) and two RCTs (Rosa, 2019; Fumagalli, 2006) were added to the summary of the literature by hand searching.

Results

One systematic review (Nassar, 2018) and 2 RCs (Jaberi, 2020; Rosa, 2019) were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Au SS, Roze des Ordons AL, Parsons Leigh J, Soo A, Guienguere S, Bagshaw SM, Stelfox HT. A Multicenter Observational Study of Family Participation in ICU Rounds. Crit Care Med. 2018 Aug;46(8):1255-1262. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003193. PMID: 29742590.

- Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, Cox CE, Wunsch H, Wickline MA, Nunnally ME, Netzer G, Kentish-Barnes N, Sprung CL, Hartog CS, Coombs M, Gerritsen RT, Hopkins RO, Franck LS, Skrobik Y, Kon AA, Scruth EA, Harvey MA, Lewis-Newby M, White DB, Swoboda SM, Cooke CR, Levy MM, Azoulay E, Curtis JR. Guidelines for Family-Centered Care in the Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017 Jan;45(1):103-128. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169. PMID: 27984278.

- Fumagalli S, Boncinelli L, Lo Nostro A, Valoti P, Baldereschi G, Di Bari M, Ungar A, Baldasseroni S, Geppetti P, Masotti G, Pini R, Marchionni N. Reduced cardiocirculatory complications with unrestrictive visiting policy in an intensive care unit: results from a pilot, randomized trial. Circulation. 2006 Feb 21;113(7):946-52.

- Gupta PR, Perkins RS, Hascall RL, Shelak CF, Demirel S, Buchholz MT. The Effect of Family Presence on Rounding Duration in the PICU. Hosp Pediatr. 2017 Feb;7(2):103-107. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0091. PMID: 28104730.

- Jaberi AA, Zamani F, Nadimi AE, Bonabi TN. Effect of family presence during teaching rounds on patient's anxiety and satisfaction in cardiac intensive care unit: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Educ Health Promot. 2020 Jan 30;9:22. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_417_19. PMID: 32154317; PMCID: PMC7034170.

- Kiwanuka F, Shayan SJ, Tolulope AA. Barriers to patient and family-centred care in adult intensive care units: A systematic review. Nurs Open. 2019 Mar 28;6(3):676-684. doi: 10.1002/nop2.253. PMID: 31367389; PMCID: PMC6650666.

- Ladak LA, Premji SS, Amanullah MM, Haque A, Ajani K, Siddiqui FJ. Family-centered rounds in Pakistani pediatric intensive care settings: non-randomized pre- and post-study design. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013 Jun;50(6):717-26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.05.009. Epub 2012 Jun 15. PMID: 22704527.

- Malacarne P, Corini M, Petri D. Health care-associated infections and visiting policy in an intensive care unit. Am J Infect Control. 2011 Dec;39(10):898-900. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.02.018. Epub 2011 Jul 23. PMID: 21783279.

- Nassar Junior APJ, Besen BAMP, Robinson CC, Falavigna M, Teixeira C, Rosa RG. Flexible Versus Restrictive Visiting Policies in ICUs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 2018 Jul;46(7):1175-1180. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003155. PMID: 29642108.

- Rosa RG, Falavigna M, da Silva DB, Sganzerla D, Santos MMS, Kochhann R, de Moura RM, et al; ICU Visits Study Group Investigators and the Brazilian Research in Intensive Care Network (BRICNet). Effect of Flexible Family Visitation on Delirium Among Patients in the Intensive Care Unit: The ICU Visits Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019 Jul 16;322(3):216-228. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.8766.

- Rosa RG, Tonietto TF, da Silva DB, Gutierres FA, Ascoli AM, Madeira LC, Rutzen W, Falavigna M, Robinson CC, Salluh JI, Cavalcanti AB, Azevedo LC, Cremonese RV, Haack TR, Eugênio CS, Dornelles A, Bessel M, Teles JMM, Skrobik Y, Teixeira C; ICU Visits Study Group Investigators. Effectiveness and Safety of an Extended ICU Visitation Model for Delirium Prevention: A Before and After Study. Crit Care Med. 2017 Oct;45(10):1660-1667. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002588. PMID: 28671901.

- 2017 ENA Clinical Practice Guideline Committee, Vanhoy MA, Horigan A, Stapleton SJ, Valdez AM, Bradford JY, Killian M, Reeve NE, Slivinski A, Zaleski ME; ENA 2017 Board of Directors Liaison:, Proehl J; 2017 Staff Liaisons:, Wolf L, Delao A, Gates L Sr. Clinical Practice Guideline: Family Presence. J Emerg Nurs. 2019 Jan;45(1):76.e1-76.e29. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2018.11.012. PMID: 30616766.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Nassar, 2018 |

SR and meta-analysis of observational and randomized studies.

Literature search up to August 3rd, 2017.

A: Eghbali-Babadi, 2017 B: Fumagalli, 2013 C: Fumagalli, 2006 D: Malacarne, 2011

Study design: A: Randomized trial

Setting and Country: A: Iran, cardiac surgery ICU B: Italy. 2ICUs

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Supported, in part, by the Brazilian Ministry of Health through the Program of Institutional Development of the Brazilian Unified Health System (PROADI-SUS). Drs. Robinson’s and Falavigna’s institutions received funding from the Brazilian Ministry of Health. Dr. Falavigna disclosed that he is an associate of a consulting and training company in Health Economics field called “HTAnalyze (www.htanalyze.com),” which provides services for both the public and private sectors. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria SR: 1) Studies comparing flexible versus restrictive visiting policies in the ICU; 2) Studies evaluating at least one of the following outcomes: 2.1) Patient-related outcomes: ICU mortality, ICU-acquired infections, delirium, ICU length of stay, length of mechanical ventilation, need for sedatives, anxiety, depression, and satisfaction; 2.2) Family member–related outcomes: anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and satisfaction; 2.3) ICU professional–related outcomes: burnout, workload, and satisfaction.

Exclusion criteria SR: n.r.

4/7 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, mean age A: XX patients, XX yrs B: C: ….

Sex: A: % Male B: C: ….

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention:

A: Flexible visitation: 30-40 min in the morning, beyond the usual time period. B: Flexible visitation: 24h/day C: Flexible visitation: 6h/day D: Flexible visitation: 3h/day

|

Describe control:

A: Restricted visitation: Usual (not described in the article). B: Restrictive visitation: 1h/day, divided into 2 periods of 30 min each. C: Restrictive visitation: 2h/day D: Restrictive vistation: 1h/day

|

End-point of follow-up: n.r.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) n.r.

|

ICU length of stay n.r.

Sleep n.r.

Pain n.r.

Anxiety/stress Defined as the results on he HADS.

Effect measure: SMD [IQR] A: n.r.

Delirium Defined as delirium incidence intervention/control (%):

A: 20.6% / 44.1% B: n.r.

Mortality Defined as mortality rate intervention/control (%)

A: n.r.

|

Author’s conclusion Although flexible family visitation models appear to be beneficial for patients’ and family members’ outcomes, its possible impact on ICU professionals burnout demand attention and adoption of prevention strategies. Randomized trials aiming to evaluate outcomes involving the three components of the patient-family-staff triad are still needed. Nonetheless, educating health professionals and family members and improving the structure of the work environment are actions required to achieve the potential benefits of flexible family visitation policies. |

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Jaberi, 2020 |

Type of study: double‑blind randomized controlled trial

Setting and country: Hospital in Iran.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The research and Technology of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences supported financially the research project. |

Inclusion criteria: The inclusion criteria for patients were age higher than 18 years, having informed consent to participate in the study, candidates for teaching round, having cognitive ability to answer questions, being alert, and no history of hospitalization in CICU. The inclusion criteria for family members include being over 18 years of age, being a prime family member (mother, father, sister or brother child, and spouse and grandparents), having a wish and request to attend beside the patients, no history of known mental illness, and no history of presence during the teaching round.

Exclusion criteria: Exclusion criteria include cancelling of continued being in research by the patients or families and the occurrence of any acute situation for the patient and family.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 30 Control: 30

Important prognostic factors2: age I: 60.63 ± 15.27 C: 63.47 ± 12.89

Sex: I: 46.7% M C: 56.7% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

In the intervention group, the selected family member presented and participated in the round. After completion of the rounds, the STAI and patient’s satisfaction about quality of round questionnaire were completed for patients in both groups by a researcher fellow, via face‑to‑face interview. |

In the control group the teaching round performed without family member’s presence. After completion of the rounds, the STAI and patient’s satisfaction about quality of round questionnaire were completed for patients in both groups by a researcher fellow, via face‑to‑face interview. |

Length of follow-up: Post-intervention

Loss-to-follow-up: n.r.

Incomplete outcome data: n.r.

|

Length of ICU stay

n.r.

Pain n.r.

Anxiety/stress Measured with STAI (range 20-80, lower score means better outcome.

I: 45.30 (SD 8.34) C: 51.10 (SD 7.76)

Delirium n.r.

Mortality n.r. |

Author’s conclusion The results of the present study revealed that FCR was able to correct patients’ STAI score and their satisfaction about various clinical aspects of round. Therefore, by implementing this program while taking advantage of other benefits, it is possible to improve patient’s outcomes. Due to the differing conditions and characteristics of adult patients for the presence of family members during medical rounds and the limited number of studies available for comparison other aspects of patient outcomes, further clinical trials are recommended.

Limitations |

|

Rosa, 2019 |

Type of study: cluster-crossover randomized clinical trial

Setting and country: 36 adult ICUs with restricted visiting hours (<4.5 hours per day) in Brazil

Funding and conflicts of interest: n.r.. |

Inclusion criteria: atients 18 years or older admitted to participating ICUs were consecutively included

Exclusion criteria: he exclusion criteria were coma (Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale19 score ≤−4) lasting longer than 96 hours from initial screening assessment or presence of any of the following characteristics at screening assessment: delirium (positive Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU [CAM-ICU] screening),20 brain death, exclusive palliative care, inability to communicate, predicted ICU length of stay less than 48 hours, unlikely to survive longer than 24 hours, prisoner status, unavailability of a family member to participate in ICU visits, and previous enrollment in the study.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 20 Control: 20

Important prognostic factors2: age I: 58.4 ± 18.3 C: 58.6 ± 18.2

Sex: I: 53.5% M C: 52.1% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

The flexible visitation model included both flexibility of ICU visiting hours and family education. One or 2 close family members were allowed to visit the patient for up to 12 hours per day; however, only 1 relative was enrolled in the study. These family members had to attend at least 1 structured meeting in which they received education about the ICU environment, common procedures, multidisciplinary work, infection control, palliative care, and delirium. These structured meetings were conducted by trained clinicians using a face-to-face format at least 3 times per week. Additionally, family members had access to an information brochure and website (http://www.utivisitas.com.br) designed to help them understand the various processes and emotions associated with an ICU stay and improve cooperation without increasing ICU staff workload. Patients were also allowed to receive social visits at specific time intervals according to local rules. Social visits were offered to friends or family members who did not qualify for flexible visitation. Implementation of the flexible visitation model is shown in eFigure 1 in Supplement 2. |

In the restricted visitation model, visitors were allowed as before randomization, according to local hours (median, 1.5 hours/d [interquartile range {IQR}, 1.0 to 2.0]; up to 4.5 hours/d). Visitors were not required to attend educational meetings. |

Length of follow-up: Hospital discharge or death.

Loss-to-follow-up: I: 0 C: 0

Incomplete outcome data: I: 6 (30%) C: 3 (15%)

|

Length of ICU stay Effect measure: median number of days (range) I: 5 (3-8)

n.r.

Pain n.r.

Anxiety/stress n.r.

Delirium n.r.

Mortality n.r. |

Author’s conclusion Among patients in the ICU, a flexible family visitation policy, vs standard restricted visiting hours, did not significantly reduce the incidence of delirium.

Limitations |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors [(potential) confounders]

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders

Risk-of-bias tables

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Nassar, 2018 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Unclear |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Unclear |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Table of quality assessment for RCTs

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? a

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?b

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?c

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?d

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?e

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?f

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measureg

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Jaberi, 2020 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: In this trial, 60 patients were assigned into two groups: “family presence during rounds” and “family absence during rounds” equally based on categories STAI levels in three categories of 20–40, 41–60, and 61–80, using the random minimization method. |

No information;

Reason: No information was provided about the allocation concealment. |

Probably yes;

Reason: To blinding, the members of round team, patients, and family members did not know exactly that the impact of the family members presence on the level of anxiety, and their satisfaction was considered by the researchers. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Predescribed outcome measures were reported. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems reported. |

LOW |

|

Rosa, 2019 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: The ICUs were consecutively randomized in a 1:1 ratio using computer-generated randomization with random block sizes of 2, 4, and 6 and stratified by number of ICU beds (≤10 or >10). |

Definiely yes;

Reason: ). A statistician blinded to cluster identity performed randomization |

Definitely no;

Reason: Outcome assessors were not blinded to study interventions, except for infectious diseases specialists adjudicating infectious outcomes. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Predescribed outcome measures were reported. |

Definitely no;

Reason: cluster randomization was susceptible to recruitment bias, since participants were aware of the interventions. |

Some concerns |

- Randomization: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomization process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomization (performed at a site remote from trial location). Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomization procedures or open allocation schedules..

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments, but this should not affect the risk of bias judgement. Blinding of those assessing and collecting outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignment influences the process of outcome assessment or data collection (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is usually not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary. Finally, data analysts should be blinded to patient assignment to prevents that knowledge of patient assignment influences data analysis.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up or the percentage of missing outcome data is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up or missing outcome data differ between treatment groups, bias is likely unless the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk is not enough to have an important impact on the intervention effect estimate or appropriate imputation methods have been used.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available (in publication or trial registry), then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- Problems may include: a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used (e.g. lead-time bias or survivor bias); trial stopped early due to some data-dependent process (including formal stopping rules); relevant baseline imbalance between intervention groups; claims of fraudulent behavior; deviations from intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; (the role of the) funding body. Note: The principles of an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

- Overall judgement of risk of bias per study and per outcome measure, including predicted direction of bias (e.g. favors experimental, or favors comparator). Note: the decision to downgrade the certainty of the evidence for a particular outcome measure is taken based on the body of evidence, i.e. considering potential bias and its impact on the certainty of the evidence in all included studies reporting on the outcome.

Table of excluded reviews

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Aparício, 2020 |

Included studies did not describe the prescribed interventions. |

|

Black, 2011 |

Review did not report single outcomes. |

|

Bradt, 2014 |

Review did not include family participation as a non-pharmacological intervention) |

|

Brito, 2020 |

Did not provide a risk-of-bias judgement and information about the search date. |

|

Deng, 2020 |

Included studies were not RCTs or did not describe the intervention family presence. |

|

Hu, 2015 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Liang, 2021 |

Review did not present individual results per included RCT. |

|

Litton, 2016 |

Did not include additional studies when compared to the reviews included in the literature summary. |

|

Luther, 2018 |

Did not include a risk-of-bias judgement nor a meta-analysis. |

|

Oldham, 2016 |

Did not include a risk-of-bias judgement nor a meta-analysis. |

|

Poongkunran, 2015 |

Included studies did not describe the prescribed interventions. |

|

Richard-Lalonde, 2020 |

Review did not include family participation as a non-pharmacological intervention) |

|

Thrane, 2019 |

Included studies did not describe the prescribed interventions. |

|

Umbrello, 2019 |

Did not include additional studies when compared to the reviews included in the literature summary. |

|

Wade, 2016 |

Included studies did not describe the prescribed interventions. |

|

Weiss, 2016 |

Included studies were not RCTs. |

|

Younis, 2019 |

Did not describe the included studies in detail. |

Table of excluded studies from Deng (2020)

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Simons, 2016 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Ono, 2011 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Taguchi, 2007 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Potjaharoen, 2018 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Van Rompaey, 2012 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Munro, 2017 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Karadas, 2016 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Alvarez, 2017 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Morris, 2016 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Girard, 2008 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Mehta, 2012 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Moon, 2015 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Giraud, 2016 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Schweickert, 2009 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Bryckowski, 2014 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Colombo, 2012 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Dale, 2014 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Estrup, 2018 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Fraser, 2015 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Kram, 2015 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Martinez, 2014 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Palmbergen, 2012 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Patel, 2014 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

|

Rivosecchi, 2016 |

Wrong intervention (music therapy, sensory deprivation or multicomponent) |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 16-12-2022

Laatst geautoriseerd : 16-12-2022

Geplande herbeoordeling :

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Doel en doelgroep

Het doel is herziening van bestaande trias van Sedatie en Analgesie richtlijnen, waar sedatie en analgesie op de IC een onderdeel van is. De Sedatie en Analgesie richtlijnen hebben betrekking op alle patiënten die sedatie krijgen buiten de OK. De richtlijn zal blijven bestaan uit drie delen – volwassenen; kinderen; en IC. Deze patiëntencategorieën kennen specifieke risico’s waardoor specifieke aanbevelingen nodig zijn.

Sedatie en analgesie van de patiënten die een IC-behandeling krijgen verschilt steeds meer van procedurele sedatie en analgesie. Daarom staat deze IC-richtlijn in de nieuwe sedatie en alagesie-richtlijn meer los van de twee sedatie en analgesie richtlijnen (volwassenen en kinderen). Voorliggende richtlijn beschrijft het comfortabel krijgen en houden van patiënten die een IC-behandeling ondergaan, het tegengaan van pijn, agitatie en stress. Het beschrijft de medicamenteuze en niet medicamenteuze opties om de patiënt met zo min mogelijk complicaties in zo kort mogelijke tijd naar zo hoog mogelijk functioneel herstelniveau te krijgen, zowel fysiek als mentaal.

De richtlijn heeft betrekking op intensivisten en IC-verpleegkundigen. Daarnaast kan de richtlijn gebruikt worden door zorgverleners die betrokken zijn bij de behandeling op of na de Intensive Care zoals de mee behandelende medisch specialisten, paramedici, verpleegkundig specialisten en apothekers.

Er is afstemming met de twee andere onderdelen van de richtlijn Sedatie en Analgesie, namelijk die voor volwassenen en voor kinderen en mag samen met deze onderdelen als geheel worden gezien.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij sedatie en analgesie van patiënten op de IC. Inbreng patiënten- en naastenperspectief via Stichting FCIC en patiëntenorganisatie IC Connect.

Werkgroep

Drs. N.C. (Niels) Gritters van de Oever, anesthesioloog-intensivist, Treant zorggroep, NVIC

Dr. K.S. (Koen) Simons, internist-intensivist, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, NVIC

Dr. M. (Marissa) Vrolijk, anesthesioloog-intensivist-, LangeLand Ziekenhuis Zoetermeer, NVIC

Dr. L. (Lena) Koers, anesthesioloog-kinderintensivist, Leiden UMC, NVA

Dr. H. (Rik) Endeman, internist-intensivist, Erasmus MC, NIV

Dr. M. (Mark) van den Boogaard, IC verpleegkundige, senior onderzoeker, Radboud UMC, V&VN

Drs. R. (Roel) van Oorsouw, fysiotherapeut, Radboud UMC, KNGF

Dr. N.G.M. (Nicole) Hunfeld, ziekenhuisapotheker, Erasmus MC, NVZA

Drs. W.P. (Wai-Ping) Manubulu-Choo, ziekenhuisapotheker, Martini Ziekenhuis, NVZA

Drs. M. (Marianne) Brackel, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Stichting FCIC en patiëntenorganisatie IC Connect, Jeugdarts knmg niet praktiserend

Met methodologische ondersteuning van

• Drs. Florien Ham, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

• Drs. Toon Lamberts, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

• Dr. Mirre den Ouden - Vierwind, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

• Drs. Ingeborg van Dusseldorp, senior informatiespecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Drs. N.C. (Niels) Gritters van de Oever |

Anesthesioloog-intensivist Treant zorggroep. |

Onbezoldigd en t/m juni 2021: NVIC bestuur ( NVIC accreditatie commissie NVIC luchtwegcommissie, congrescommissie) Chief Medical Officer van de LCPS (dagvergoeding) t/m maart 2022 voorzitter farmacotherapiecommissie NVIC per juli 2022 lid stafbestuur Treant ziekenhuisgroep per aug 2022 (vacatievergoeding) lid scientific board covidpredict per 2020 (onbezoldigd), commissie Acute Tekorten Geneesmiddelen per 2020 (vergadervergoeding) |

Geen. |

Geen actie. |

|

Dr. K.S. (Koen) Simons |

Internist-intensivist Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis. |

FCCS-instructeur bij NVIC (ca. 2 dagen/jaar, betaald). |

Geen. |

Geen actie. |

|

Dr. M. (Marissa) Vrolijk |

Anesthesioloog- intensivist LangeLand Ziekenhuis. |

Medisch beoordelaar adoptie bij Adoptie Stichting Meiling. |

Geen. |

Geen actie. |

|

Dr. L. (Lena) Koers |

Anesthesioloog-kinderintensivist LUMC |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen actie. |

|

Dr. H. (Rik) Endeman |

Internist-intensivist, Erasmus MC. |

Voorzitter van de gemeenschappelijke intensivisten commissie (GIC) (onbetaald). |

TravelGrant van Getinge om te spreken op een lunchsymposium in Kenya voor het jaarcongres (2018) van de Kenyan Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine. Dit congres wordt ook veelbezocht door anaesthesisten en intensivisten uit omliggende landen. Het onderwerp was 'Hemodynamic monitoring in low resource and high resource environments', duurde een uur, en ging over wat voor meetinstrumenten je kan gebruiken om de hemodynamiek te bewaken indien je geen middelen hebt (low resource) en wel (high resource); duurde uiteindelijk 90 minuten. GETINGE verkoopt high-end HD-monitoring, deze kwamen in de presentatie voor, maar ook die van concurrenten. GETINGE had mij niets opgelegd m.b.t. de inhoud van de presentatie. PI van: Open Lung Concept 2.0 studie: Flow controlled ventilation (gesponsord door Ventinova). |

Geen actie. Het gesponsorde onderzoek is niet gerelateerd aan het onderwerp van de richtlijn. |

|

Dr. M. (Mark) van den Boogaard |

Senior onderzoeker, afdeling lntensive Care, Radboudumcc. |

Onbezoldigde functies: - Bestuurslid European Delirium Association. - Adviseur Network for lnvestigation of Delirium: Unifying Scientists (NIDUS). - Organisator IC-café regio Nijmegen & Omstreken. - Lid werkgroep Longterm Outcome and ICU Delirium van de European Society of lntensive Care Medicine. - Lid richtlijn Nazorg en revalidatie IC-patiënten. |

PI van onderstaande gesubsidieerde projecten: ZonMw subsidies: - programma GGG [2013]: Prevention of ICU delirium and delirium-related outcome with haloperidol; a multicentre randomized controlled trial. - programma DO [2015]: The impact of nUrsing DEliRium Preventive lnterventions in the lntensive Care Unit (UNDERPIN-ICU). Delirium komt terug in beide projecten en in de richtlijn, maar er zullen geen aanbevelingen naar vormen komen die belangenverstrengeling veroorzaken. Geen problemen worden voorzien, vanwege het niet betrokken zijn bij aanbevelingen over medicatie/verpleegkundige interventie obv door ZonMw gesubsidieerde projecten. ZIN subsidie: - programma Gebruiken van uitkomsteninformatie bij Samen beslissen [2018]: Samen beslissen op de IC: het gebruik van (patiëntgerapporteerde) uitkomst informatie bij gezamenIijke besluitvorming over IC-opname en behandelkeuzes op de IC. |

Geen actie. |

|

Drs. R. (Roel) van Oorsouw |

Fysiotherapeut/ PhD-kandidaat Radboudumc. |

Visiterend docent op de Hogeschool. Arnhem Nijmegen (10 uur per jaar) Congrescommissie NVZF (tot oktober 2021) Lid ethiekcommissie KNGF (sinds oktober 2021). |

Geen. |

Geen actie. |

|

Dr. N.G.M. (Nicole) Hunfeld |

Ziekenhuisapotheker ErasmusMC. |

Bestuurslid KNMP (functie: penningmeester, betaald). |

Boegbeeldfunctie, maar sedatie heeft geen relatie met openbare farmacie. |

Geen actie. |

|

Drs. W.P. (Wai-Ping) Manubulu-Choo |

Ziekenhuisapotheker, Martini Ziekenhuis. |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen actie. |

|

Drs. M. (Marianne) Brackel |

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Stichting FCIC en patiëntenorganisatie IC Connect, Jeugdarts knmg niet praktiserend. |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen actie. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van Stichting Family and patient Centered Intensive Care (FCIC) en de patiëntenorganisatie IC Connect voor deelname aan de werkgroep. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de FCIC en IC Connect en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst kwalitatieve raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module 1 Pijnprotocol op de IC |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module 2 Lichte sedatie op de IC |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module 3a Analgetica versus hypnotica |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat [het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module 3b Analgeticum bij analgosedatie |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module 4 Intraveneuze medicatie op de IC |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen. |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module 5 Inhalatieanesthetica op de IC |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen. |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module 6 Nonfarmacologische interventies |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module 7 Organisatie van zorg |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen. |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met sedatie en analgesie op de IC. Er is een knelpuntenanalyse gehouden samen met de andere Sedatie en analgesie richtlijnen. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld. Ook beoordeelde de werkgroep de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijn Procedurele Sedatie en analgesie bij volwassenen op de Intensive Care (NVK/NVA, 2012) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens is er gekeken naar samenhang met andere bestaande en te ontwikkelen richtlijnen, o.a. de richtlijn Delirium op de Intensive Care (NVIC, 2010) en de richtlijn Nazorg en revalidatie van intensive care patiënten (VRA/NVIC) en aansluiting op de Europese richtlijn PADIS, 2018, die over hetzelfde onderwerp gaat. Ten tijde van de autorisatiefase van deze richtlijn verscheen de richtlijn sepsis (NIV), waarin onderdelen van de sedatie van de septische IC-patiënt worden besproken. Beide richtlijnen vullen elkaar aan.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

er is hoge zekerheid dat het ware effect van behandeling dichtbij het geschatte effect van behandeling ligt; het is zeer onwaarschijnlijk dat de literatuurconclusie klinisch relevant verandert wanneer er resultaten van nieuw grootschalig onderzoek aan de literatuuranalyse worden toegevoegd. |

|

Redelijk |

er is redelijke zekerheid dat het ware effect van behandeling dichtbij het geschatte effect van behandeling ligt; het is mogelijk dat de conclusie klinisch relevant verandert wanneer er resultaten van nieuw grootschalig onderzoek aan de literatuuranalyse worden toegevoegd. |

|

Laag |

er is lage zekerheid dat het ware effect van behandeling dichtbij het geschatte effect van behandeling ligt; er is een reële kans dat de conclusie klinisch relevant verandert wanneer er resultaten van nieuw grootschalig onderzoek aan de literatuuranalyse worden toegevoegd. |

|

Zeer laag |

er is zeer lage zekerheid dat het ware effect van behandeling dichtbij het geschatte effect van behandeling ligt; de literatuurconclusie is zeer onzeker. |

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.