Preconceptionele thyreotoxicose

Uitgangsvraag

Hoe dienen vrouwen met een actieve ziekte van Graves te worden begeleid voorafgaand* aan de zwangerschap?

* Keuzes die preconceptie gemaakt worden hangen deels af van de mogelijke effecten tijdens een (vroege) zwangerschap, derhalve zijn aanbevelingen ook deels gebaseerd op zwangerschap-specifieke overwegingen.

Aanbeveling

Aanbeveling-1

Maak de behandelkeuze voor de actieve ziekte van Graves bij een vrouw met een zwangerschapswens volgens het shared decision making principe na voorlichting over de verschillende behandelopties in multidisciplinair verband inclusief de voor- en nadelen, weergegeven in tabel 1 Zwangerschap-specifieke overwegingen bij de preconceptionele voorlichting en behandeling van de ziekte van Graves.

Aanbeveling-2

Streef bij vrouwen met de ziekte van Graves naar preconceptionele euthyreoïdie en zo laag mogelijke TRAb-concentraties, bij voorkeur <3x ULN (zie module Afkapwaarde TSH-receptor antistof bepaling).

PTU/thiamazol

PTU (titratie therapie) heeft de voorkeur boven thiamazol indien er gekozen wordt om te behandelen met schildklier remmende medicatie rondom of tijdens de zwangerschap.

Controleer de schildklierfunctie tijdens titratie behandeling met schildklier remmende medicatie rondom of tijdens de zwangerschap elke 2-4 weken tijdens het instellen van de therapie en tijdens de eerste 20 weken van de zwangerschap.

Titreer tijdens behandeling met schildklier remmende medicatie rondom of tijdens de zwangerschap de dosering op basis van het vrij T4, met een streefwaarde in de bovenste 30% van het referentie interval ongeacht onderdrukking van de TSH concentratie. De dosering kan vaak worden afgebouwd en bij een lage dosering (PTU ≤50mg per dag of thiamazol ≤2,5mg per dag) kan de therapie vaak gestopt worden vanaf ongeveer 20 weken zwangerschap.

Bij vrouwen die tijdens de eerste 16 weken behandeld zijn met thiamazol of PTU dient echografische follow-up plaats te vinden ter analyse van aangeboren afwijkingen (GUO1) , en bij vrouwen die thiamazol of PTU gebruiken na 16 weken dient echografische controle plaats te vinden ter analyse van foetale hypo- of hyperthyreoïdie (zie module Additionele foetale echografie).

Radioactief jodium

Raadt zwangerschap actief af en bespreek anticonceptie voorafgaand aan de behandeling met radioactief jodium tot minimaal 6 maanden na de behandeling . Een behandeling met radioactief jodium is gecontra-indiceerd tijdens de zwangerschap of borstvoeding.

Behandeling met radioactief jodium is vaak gecontra-indiceerd bij vrouwen met de oogziekte van Graves (zie sectie 4 van de richtlijn Schildklierfunctiestoornissen). Een hoge TRAb-concentratie is een relatieve contra-indicatie voor radioactief jodium vanwege de verwachtte stijging van de concentratie en verhoging van de kans op foetale complicaties tijdens de zwangerschap.

Thyreoïdectomie

Behandeling middels thyreoïdectomie is bij voorkeur gereserveerd voor patiënten met een actieve zwangerschapswens die niet in aanmerking komen voor behandeling met thiamazol/PTU of radioactief jodium, of waar behandeling met schildklier remmende medicatie is gefaald na minimaal 12-18 maanden behandeling (bijvoorbeeld bij persisterend actieve ziekte).

Behandeling middels thyreoïdectomie tijdens de zwangerschap dient overwogen te worden middels een multidisciplinair overleg en is geïndiceerd voor patiënten met een ongecontroleerde hyperthyreoïdie ondanks schildklier remmende medicatie, waar de nadelen van een iatrogene vroeggeboorte niet opwegen tegen de maternale voordelen. Plummeren kan overwogen worden conform het advies bij niet zwangere patiënten.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De werkgroep heeft een literatuurstudie verricht om te achterhalen of de verschillende behandelopties voor de ziekte van Graves preconceptioneel geassocieerd zijn met ongewenste zwangerschapsuitkomsten. Er werden tien retrospectieve cohort studies gevonden: één studie vergeleek thyreoïdectomie met radioactief jodium (Elston, 2014), zeven studies vergeleken propylthiouracil met methimazole (Harn-a-Morn, 2021; Korelitz, 2013; Momotani, 1997; Seo, 2018; Yoshihara, 2012; Yoshihara, 2014; Yoshihara, 2023) en twee studies vergeleken jodium met anti-thyreoïdie medicatie (Yoshihara, 2015; Zhang, 2016). De bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten ‘foetale en neonatale hyper- en hypothyroïdie’ en ‘IUVD’ voor alle drie de interventies was zeer laag of kon niet beoordeeld worden omdat de uitkomstmaat niet werd gerapporteerd in de geïncludeerde studies. Ook voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten ‘small for gestational age/groei restrictie, intra-uteriene groeivertraging’, ‘vroeggeboorte’, ‘NICU opname’, ‘opname op de IC’, ‘risico op pre-eclampsie of HELLP’, ‘recidief ziekte van Graves tijdens zwangerschap en postpartum’, ‘fertiliteit’ en ‘lange termijn uitkomsten voor de moeder’ werd een zeer lage bewijskracht of geen informatie gevonden. De overall bewijskracht is daarom zeer laag. Er kunnen op basis van alleen de literatuur geen sterke aanbevelingen geformuleerd worden over hoe vrouwen met de ziekte van Graves dienen te worden behandeld voorafgaand aan de zwangerschap. Derhalve werden de aanbevelingen gemaakt op basis van de voor- en nadelen van de verschillende behandelopties, welke zijn gebaseerd op de geanalyseerde studies, bekende risico’s en bijwerkingen buiten de zwangerschap en expert opinion. In Tabel 1 worden de voor- en nadelen van verschillende preconceptie behandelopties weergegeven.

Tabel 1 Zwangerschap-specifieke overwegingen bij de preconceptionele voorlichting en behandeling van de ziekte van Graves.

|

Behandelopties |

Voordelen |

Nadelen |

|

PTU titratie (1) Doorgaan tijdens zwangerschap (2) Stoppen bij positieve zwangerschapstestb |

- Snelste optie tot start zwangerschap (1) - Geen permanente hypothyreoïdie (1+2) - Relatief snelle daling TRAb (1+2) |

- ~3% hoger risico aangeboren afwijking (1) - Mogelijke bijwerkingen (1+2) - Tijd tot stabiele dosis langer bij titratie dan bij block and replace (1+2) - Kans op recidief o.a. tijdens zwangerschap (2) - Adequate anticonceptie nodig (2) |

|

Thiamazol/PTU 1-2y Block and replace, dan stop |

- Euthyreoidie na staken bij 50-70%a - Geen permanente hypothyreoïdie - Relatief snelle daling TRAb |

- Mogelijke bijwerkingen - Risico op aangeboren afwijkingen bij ongeplande zwangerschap tijdens gebruik medicatie - Kans op recidief, o.a. tijdens zwangerschap - Adequate anticonceptie nodig |

|

Radioactief jodium Titratie versus ablatie |

- Succesvol (euthyreoïdie met levothyroxine behandeling) in 90-100%c bij ablatieve dosis - Succesvol (euthyreoïdie zonder levothyroxine behandeling) ~30%c bij titratie - Non-invasieve behandeling met permanent effect indien succesvol |

- Tijdelijke toename in TRAbsd - Contraindicatie zwangerschap binnen 6 maanden na behandeling, op basis van radioactiviteit - Relatieve contraindicatie op basis van stijging TRAbse - Risico op permanente hypothyreoidie of noodzaak 2e gift (bij ablatieve dosis) - Adequate anticonceptie nodig |

|

Thyreoïdectomie |

- Euthyreoïdie (met levothyroxine) in ~100% - Relatief snelle afname TRAb - Behandeling met permanent effect |

- Permanente hypothyreoidie - Chirurgische complicaties ~10%c |

a Overweeg gebruik van de GREAT score om de kans nauwkeuriger in te schatten

b Kan overwogen worden bij een laag risico op een recidief (>6 maanden behandeld, normaal TSH, <10mg thiamazol of <200mg PTU per dag, TRAb <3x ULN). Gemiddeld genomen duurt het zo’n 3 maanden voordat een recidief optreedt, derhalve kan de teratogene periode zeer waarschijnlijk overbrugd worden in het geval van een recidief.

c Indicatief, getallen kunnen aanzienlijk verschillen tussen ziekenhuizen; voorlichting en risicoinschatting voor een thyreoidectomie kan voor de ziekte van Graves verschillen van standaard thyreoïdectomie voorlichting voor andere indicaties, vaak is het complicatierisico iets hoger.

d Het kan tot wel 1,5 jaar duren totdat waarden normaliseren naar basiswaarden van voor therapie

e Er zijn geen data over de preconceptie TRAb concentratie vanaf wanneer een zwangerschap veilig is. Een TRAb concentratie tot 3x ULN kan als veilig beschouwd worden. Hierboven dient per individu op basis van de waarde, trend en andere omstandigheden een beslissing gemaakt te worden, bij voorkeur in een multidisciplinair overleg. Een functionele antistofmeting kan hierbij ondersteunend zijn.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Omdat elke optie (zie Tabel 1) relevante voor- en nadelen heeft, wordt een shared-decision making proces aangeraden om tot een zo passend mogelijk besluit te komen voor de individuele patiënt. De reden voor een voorkeur van een behandeling kan bij bepaalde subgroepen van patiënten anders zijn. Bijvoorbeeld, vrouwen die aan het einde van hun fertiele levensperiode zijn kunnen hun beslissing meer laten afhangen van de timing tot een zwangerschap, terwijl vrouwen die een kind met een aangeboren afwijking hebben de beslissing meer af kunnen laten hangen van het herhaal risico. Vanwege de complexiteit en het relatief lage volume van patiënten waarbij eerder genoemde afwegingen gemaakt dienen te worden zou de voorlichting multidisciplinair, door endocrinoloog en gynaecoloog, verricht moeten worden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De kosten/baten ratio is niet relevant verschillend voor de verschillende behandelopties.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er is geen kwalitatief of kwantitatief onderzoek verricht naar de aanvaardbaarheid of haalbaarheid van genoemde behandelopties preconceptioneel. Er is een potentieel moreel bezwaar om tijdens de zwangerschap te behandelen met een medicijn zoals PTU of thiamazol waarvan bekend is dat het het risico op een aangeboren afwijking verhoogt, maar de afweging van voor en nadelen zoals gemaakt in deze richtlijn kunnen de counseling ondersteunen. Gynaecologen zien relatief weinig patiënten met de ziekte van Graves. Medisch specialisten, anders dan de gynaecoloog, komen relatief weinig in aanraking met vrouwen met een zwangerschapswens of actieve zwangerschap. Het blijft van belang om bij de eerste diagnose maar ook tijdens de follow-up van de ziekte van Graves na te gaan of er sprake is van een zwangerschapswens in de nabije toekomst. Derhalve is een goede samenwerking tijdens preconceptioneel advies en de vroege zwangerschap belangrijk. Preconceptionele counseling wordt bij voorkeur verricht door een endocrinoloog, in samenwerking met een gynaecoloog. Jaarlijks navraag naar een kinderwens door iedere zorgprofessional die voor mensen in de vruchtbare levensfase zorgt, zou ook bevorderlijk kunnen zijn voor optimale haalbaarheid.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Graves’ disease is a risk factor for adverse pregnancy and/or fetal outcomes. These risks are best ameliorated by ensuring biochemical control of thyroid function and the lowest possible maternal TSH receptor antibody (TRAb) concentrations during preconception and pregnancy. At least 95% of Graves’ disease that complicates pregnancy is pre-existing rather than diagnosed during pregnancy. Therefore, preconception counselling and treatment decision making is the key to lower the risk of adverse outcomes. However, this is a field with sparse (high quality) evidence available to support management decisions. Therefore, the committee decided to fulfill a large general literature search to identify relevant papers on the management of this specific patient group and provide a table on the different pros and cons of management strategies in the preconception phase.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Thyroidectomy versus radioiodine

Fetal outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of thyroidectomy on fetal hyperthyroidism when compared with radioiodine in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Elston, 2014 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of thyroidectomy on fetal hypothyroidism, small for gestational age/growth restriction/intrauterine growth retardation, intrauterine fetal death, and preterm delivery when compared with radioiodine in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive. |

Neonatal outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of thyroidectomy on neonatal hypo- and hyperthyroidism when compared with radioiodine in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Elston, 2014 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of thyroidectomy on congenital anomalies when compared with radioiodine in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Elston, 2014 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of thyroidectomy on NICU admission when compared with radioiodine in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive. |

Maternal outcomes

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of thyroidectomy on admission to ICU, risk of preeclampsia or HELLP, recurrence of Graves’ disease during pregnancy and postpartum, and fertility when compared with radioiodine in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive. |

Propylthiouracil versus methimazole

Fetal outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of propylthiouracil on fetal hypothyroidism when compared with methimazole in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Momotani, 1997 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of propylthiouracil on fetal hyperthyroidism when compared with methimazole in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Momotani, 1997 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of propylthiouracil on small for gestational age/growth restriction/intrauterine growth retardation when compared with methimazole in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Harn-a-morn, 2021 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of propylthiouracil on preterm delivery when compared with methimazole in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Harn-a-morn, 2021 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of propylthiouracil on intrauterine fetal death when compared with methimazole in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive. |

Neonatal outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of propylthiouracil on neonatal hypothyroidism when compared with methimazole in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Yoshihara, 2023 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of propylthiouracil on neonatal hyperthyroidism when compared with methimazole in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Yoshihara, 2023 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of propylthiouracil on congenital anomalies when compared with methimazole in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Korelitz, 2013; Seo, 2018; Yoshihara, 2012; Yoshihara, 2014 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of propylthiouracil on NICU admission when compared with methimazole in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive. |

Maternal outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of propylthiouracil on risk of preeclampsia or HELLP when compared with methimazole in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Harn-a-morn, 2021 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of propylthiouracil on recurrence of Graves' disease during pregnancy and postpartum when compared with methimazole in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Yoshihara, 2012 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of propylthiouracil on admission to ICU and fertility when compared with methimazole in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive. |

Radioiodine versus anti-thyroid drugs

Fetal outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of radioiodine on small for gestational age/growth restriction/intrauterine growth retardation when compared with anti-thyroid drugs in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Zhang, 2016 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of radioiodine on intrauterine fetal death when compared with anti-thyroid drugs in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Yoshihara, 2015 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of radioiodine on preterm delivery when compared with anti-thyroid drugs in women with Graves wishing to conceive.

Source: Zhang, 2016 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of radioiodine on fetal hypo- and hyperthyroidism when compared with anti-thyroid drugs in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive. |

Neonatal outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of radioiodine on congenital anomalies when compared with anti-thyroid drugs in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive.

Source: Zhang, 2016 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of radioiodine on neonatal hypo- and hyperthyroidism and NICU admission when compared with anti-thyroid drugs in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive. |

Maternal outcomes

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of radioiodine on admission to ICU, risk of preeclampsia or HELLP, recurrence of Graves’ disease during pregnancy and postpartum, and fertility when compared with anti-thyroid drugs in women with Graves’ disease wishing to conceive. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Table 1. Description of included studies.

|

Study |

Intervention |

Control |

Outcomes |

|

Elston, 2014 |

Thyroidectomy (n=12) |

Radioiodine (n=17) |

Fetal hyperthyroidism, neonatal hypo- and hyperthyroidism, miscarriage |

|

Harn-a-morn, 2021 |

PTU (n=128) |

MMI (n=67) |

Preeclampsia, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction |

|

Korelitz, 2013 |

PTU (n=1533) |

MMI (n=1201) |

Congenital anomalies |

|

Momotani, 1997 |

PTU (n=34) |

MMI (n=43) |

Fetal hypo- and hyperthyroidism |

|

Seo, 2018 |

PTU (n=9930) |

MMI (n=1120) |

Congenital anomalies |

|

Yoshihara, 2012 |

PTU (n=1578) |

MMI (n=1426) |

Congenital anomalies |

|

Yoshihara, 2014 |

PTU (n=51) |

MMI (n=40) |

Preterm delivery, congenital anomalies |

|

Yoshihara, 2023 |

PTU (n=242) |

MMI (n=63) |

Neonatal hypo- and hyperthyroidism |

|

Yoshihara, 2015 |

KI (n=283) |

MMI (n=1333) |

Congenital anomalies, fetal death |

|

Zhang, 2016 |

131I (n=130) |

ATD (n=127) |

Intrauterine growth restriction, preterm birth |

Abbreviations: 131I=radioactive iodine; ATD=anti-thyroid drugs; KI=potassium iodione; MMI=methimazole; PTU=propylthiouracil

1. Thyroidectomy versus radioiodine

Elston (2014) performed a retrospective chart review to review the management of pregnancies following definitive treatment for Graves’ disease (GD) in order to assess the rates of maternal hypothyroidism and TRAb-measurement. Women who had received definitive treatment for GD and subsequently had one or more pregnancies, and who were aged <45 years at the time of treatment were included. In total, 12 women underwent thyroidectomy and 17 women received radioiodine treatment. Groups were not comparable. Women who received radioiodine treatment more often had TSH >4 mU/L at pregnancy diagnosis, while women who underwent thyroidectomy were more often euthyroid around time of conception. Outcomes of interest were fetal hyperthyroidism, neonatal hypo- and hyperthyroidism, and miscarriages.

2. Propylthiouracil (PTU) versus methimazole (MMI)

Harn-a-morn (2021) performed a retrospective cohort study to determine the rate of preterm birth, fetal growth restriction and low birth weight between those treated with

PTU and MMI. Medical records of singleton pregnancies in women with thyrotoxicosis caused by GD were included. Other inclusion criteria were: a diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis (i.e., a decreased TSH level and an increased free T4) either before or during pregnancy and being taken care of by endocrinologists; attending prenatal care and giving birth at Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital; no serious medical diseases (e.g., pre-gestational diabetes, heart diseases); and known final obstetric outcomes. Women with thyrotoxicosis caused by gestational thyrotoxicosis, Hashitoxicosis, toxic goiters, drug-induced and LT4 excess were excluded. Besides, pregnancies complicated with other medical diseases and incomplete medical records were excluded. In total, 128 women were treated with PTU and 67 women were treated with MMI. Groups were probably comparable. Outcomes of interest were preeclampsia, preterm birth (defined as delivery before 37 complete weeks of gestation), and fetal growth restriction (defined as a birth weight of less than 2500 grams).

Korelitz (2013) performed a retrospective claims analysis to determine the prevalence of thyrotoxicosis among pregnant women and to assess the frequency of antithyroid therapies, the risk of adverse events during pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Women between 15 and 44 years who were enrolled for at least 24 months with prescription drug benefits and had at least two pregnancy-related medical service claims between 2005 and 2009 were included. Besides, the linked infant records of women with delivered pregnancies were included. In total, 1533 women were treated with PTU and 1201 women were treated with MMI only. It is unclear if groups were comparable, since patient characteristics were not reported for both groups separately. The outcome of interest was congenital anomalies.

Momotani (1997) performed a prospective cohort study to compare the suppressive effect of PTU with that of MMI on fetal thyroid status. Pregnant women with GD were included if they continued PTU or MMI until delivery, had taken the drugs for at least 4 weeks, had normal free T4 levels (FT4) at delivery and delivered at term. None of them had a history of radioiodine therapy or surgery for GD. In total, 34 women received PTU and 43 women received MMI. It is unclear if groups were comparable, since patient characteristics were not reported for both groups separately. Outcomes of interest were fetal FT4 levels and TSH level.

Seo (2018) performed a cohort study to determine the association between maternal prescriptions for antithyroid drugs and congenital malformations in live births. Pregnant women aged 20 to 39 years who did not have prior childbirth records for at least 1 year before the date of delivery were included. Besides, the linked offspring records of women with delivered pregnancies were included. Cases that could not be linked in the National Health Insurance database were excluded. In total, 9930 women received PTU and 1120 women received MMI. It is unclear if groups were comparable, since patient characteristics were not reported for both groups separately. The outcome of interest was congenital anomalies.

Yoshihara (2012) performed a retrospective study to examine the effects of in utero exposure to MMI or PTU in the first trimester of pregnancy. Pregnant women with GD were included. In total, 1578 women were treated with PTU and 1426 women received MMI during the first trimester of pregnancy (0 to 12 weeks of gestation). It is unclear if groups were comparable, since patient characteristics were not compared between both groups. The outcome of interest was congenital anomalies.

Yoshihara (2014) performed a retrospective study to determine the frequency of adverse events in untreated pregnant GD patients after initial antithyroid drug therapy. Untreated pregnant women who were newly diagnosed with GD were included. Gestational transient thyrotoxicosis was differentiated and excluded by the presence of TRAb. In total, 51 women received PTU and 40 women received MMI. It is unclear if groups were comparable, since patient characteristics were not reported for both groups separately. Outcomes of interest were preterm delivery (not defined) and congenital anomalies.

Yoshihara (2023) performed a retrospective cohort study among mothers with GD and their newborns who were treated with MMI or PTU to control thyrotoxicosis until delivery. In total, 242 women received PTU and 63 women were treated with MMI. It is unclear if groups were comparable, since patient characteristics were only reported at delivery. Outcomes of interest were neonatal hypo- and hyperthyroidism.

3. Iodine versus anti-thyroid drugs

Yoshihara (2015) performed a retrospective study to assess whether switching from MMI to potassium iodine (KI) in the first trimester of pregnancy would decrease the incidence of major congenital anomalies in comparison to treatment with MMI alone. Women with GD who were switched from MMI to inorganic iodide to control hyperthyroidism in the first trimester were included. In total, 283 women switched from MMI to KI, while 1333 women only received MMI. Groups were probably comparable. Outcomes of interest were congenital anomalies and fetal death.

Zhang (2016) performed a retrospective study to assess the outcomes of pregnancy after radioactive iodine (131I) treatment in patients of reproductive age with Graves’ disease and to examine the effect of the 131I treatment on the mothers and newborns. Women with GD who became pregnant at least six months after 131I therapy or antithyroid drug treatment for hyperthyroidism were included. Exclusion criteria were patients for whom GD diagnosis was made during the pregnancy, patients who had other thyroid diseases or other diseases, and GD patients who underwent thyroid surgery before pregnancy. In total, 130 women received 131I treatment and 127 women received anti-thyroid drug therapy. It is unclear if groups were comparable, since patient characteristics were not compared between both groups. Outcome of interests were intrauterine growth restriction (not defined) and preterm birth (defined as ≥28 but <37 weeks).

Results

1. Thyroidectomy versus radioiodine

Fetal outcomes

1. Fetal hypothyroidism

Not reported.

2. Fetal hyperthyroidism

Elston (2014) reported that no fetal thyrotoxicosis was diagnosed in the radioiodine-group, while no information was available for the thyroidectomy-group. It was unclear how fetal thyrotoxicosis was diagnosed.

3. Small for gestational age/growth restriction/intrauterine growth retardation

Not reported.

4. Intrauterine fetal death

Not reported.

5. Preterm delivery

Not reported.

Neonatal outcomes

1. Neonatal hypothyroidism

Elston (2014) reported that no neonatal hypothyroidism was diagnosed in the radioiodine-group, while no information was available for the thyroidectomy-group.

2. Neonatal hyperthyroidism

Elston (2014) reported that no neonatal thyrotoxicosis was diagnosed in the radioiodine-group, while one case of neonatal thyrotoxicosis was diagnosed in the thyroidectomy-group.

3. NICU admission

Not reported.

4. Congenital anomalies

Elston (2014) reported that one pregnancy was terminated because of major congenital anomaly in the radioiodine-group, while no information was available for the thyroidectomy-group.

Maternal outcomes

1. Admission to ICU

Not reported.

2. Risk of preeclampsia or HELLP

Not reported.

3. Recurrence of Graves’ disease during pregnancy and postpartum

Not reported.

4. Fertility

Not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

According to GRADE, observational studies start at a low level of evidence.

Fetal outcomes

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure fetal hyperthyroidism was downgraded by two levels to very low because of no adjustment for confounders (-1, risk of bias) and the optimal information size was not achieved (-1, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures fetal hypothyroidism, small for gestational age/growth restriction/intrauterine growth retardation, intrauterine fetal death and preterm delivery could not be assessed with GRADE since these outcomes were not reported in the included studies.

Neonatal outcomes

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures neonatal hypothyroidism was downgraded by two levels to very low because of no adjustment for confounders (-1, risk of bias) and the optimal information size was not achieved (-1, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures neonatal hyperthyroidism was downgraded by two levels to very low because of no adjustment for confounders (-1, risk of bias) and the optimal information size was not achieved (-1, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures NICU admission could not be assessed with GRADE since these outcomes were not reported in the included studies.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures congenital anomalies was downgraded by two levels to very low because of no adjustment for confounders (-1, risk of bias) and the optimal information size was not achieved (-1, imprecision).

Maternal outcomes

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures admission to ICU, risk of preeclampsia or HELLP, recurrence of Graves’ disease during pregnancy and postpartum, and fertility could not be assessed with GRADE since these outcomes were not reported in the included studies.

- Propylthiouracil versus methimazole

Fetal outcomes

1. Fetal hypothyroidism

Momotani (1997) assessed fetal hypothyroidism by blood samples from the umbilical cords of infants at time of delivery. Seven of the 34 women (20.6%) who received PTU had a fetus with TSH levels above the normal range (hypothyroidism) as compared to 6 of the 43 women (14.0%) who received MMI (RR=1.48, 95%CI 0.55 to 3.98). This difference is clinically relevant favoring MMI.

2. Fetal hyperthyroidism

Momotani (1997) assessed fetal hyperthyroidism by blood samples from the umbilical cords of infants at time of delivery. Two of the 43 women (4.7%) who received MMI had a fetus with TSH levels below the normal range (hyperthyroidism), while this did not occur in fetuses of women who received PTU.

3. Small for gestational age/growth restriction/intrauterine growth retardation

Harn-a-morn (2021) reported that 16 of the 126 women (12.7%) who received PTU had a child with fetal growth restriction (birth weight of less than 2500 grams) as compared to 6 of the 66 women (9.1%) who received MMI (RR=1.40, 95%CI 0.57 to 3.40).

4. Intrauterine fetal death

Not reported.

5. Preterm delivery

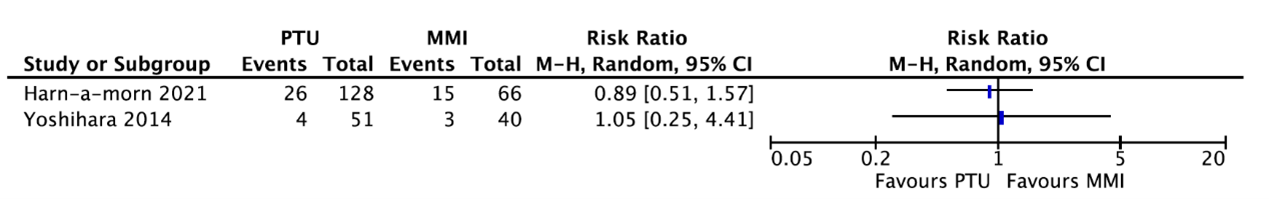

Two studies reported preterm delivery (figure 1). Due to poor reporting of patient characteristics, pooling of data was not possible.

Harn-a-morn (2021) reported that 26 of the 128 women (20.3%) who received PTU had a preterm birth (delivery before 37 complete weeks of gestation) as compared to 15 of the 66 women (22.7%) who received MMI (RR=0.89, 95%CI 0.51 to 1.57). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Yoshihara (2014) reported that 4 of the 51 women (7.8%) who received PTU had a preterm delivery (not defined) as compared to 3 of the 40 women (7.5%) who received MMI (RR=1.05, 95%CI 0.25 to 4.41). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Preterm delivery for women receiving PTU or MMI.

Neonatal outcomes

1. Neonatal hypothyroidism

Yoshihara (2023) reported that 31 of the 242 women (12.8%) who received PTU had a neonate with hypothyroidism as compared to 12 of the 63 women (19%) who received MMI (RR=0.67, 95%CI 0.37 to 1.23). This difference is clinically relevant favoring PTU.

2. Neonatal hyperthyroidism

Yoshihara (2023) reported that 3 of the 242 women (1.2%) who received PTU had a neonate with hyperthyroidism, while this was not reported in neonates whose mother received MMI.

3. NICU admission

Not reported.

4. Congenital anomalies

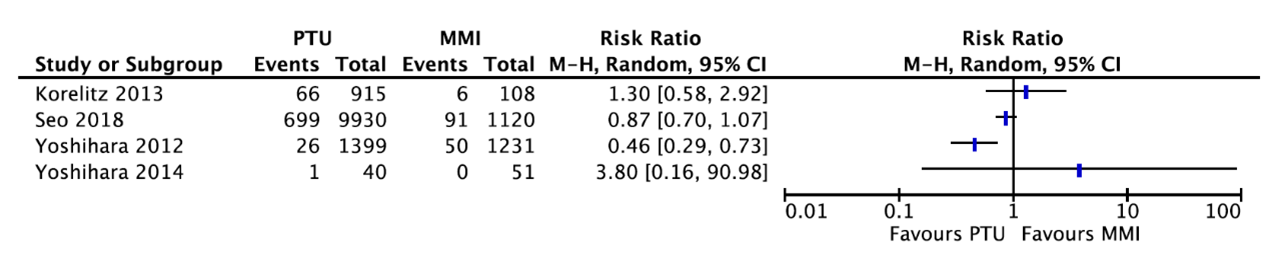

Four studies reported about congenital anomalies (figure 2). Due to the poor reporting of patient characteristics, pooling of data was not possible.

Korelitz (2013) reported that 66 of the 915 women (7.2%) who received PTU had a child with any congenital defect as compared to 6 of the 108 women (5.6%) who received MMI (RR=1.30, 95%CI 0.58 to 2.92). This difference is clinically relevant favoring MMI.

Seo (2018) reported that 699 of the 9930 women (7.04%) who received PTU had a child with a congenital malformation as compared to 91 of the 1120 women (8.13%) who received MMI (RR=0.87, 95%CI 0.70 to 1.07). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Yoshihara (2012) reported that 26 of the 1399 children (1.9%) whose mother received PTU had a congenital malformation as compared to 50 of the 1231 children (4.1%) whose mother received MMI (RR=0.46, 95%CI 0.29 to 0.73). This difference is clinically relevant favoring PTU.

Yoshihara (2014) reported that 1 of the 40 women (2.5%) who received MMI had a child with a congenital abnormality (omphalocele), while no congenital abnormalities were reported in children whose mother received PTU.

Figure 2. Congenital anomalies for women receiving PTU or MMI.

Maternal outcomes

1. Admission to ICU

Not reported.

2. Risk of preeclampsia or HELLP

Harn-a-morn (2021) reported that 11 of the 128 women (8.6%) who received PTU had preeclampsia as compared to 4 of the 66 women (6.1%) who received MMI (RR=1.42, 95%CI 0.47 to 4.28). This difference is clinically relevant favoring MMI.

3. Recurrence of Graves’ disease during pregnancy and postpartum

Yoshihara (2012) reported maternal hyperthyroidism during first trimester. In total, 277 of the 1236 women (21.9%) who received PTU had hyperthyroidism during the first trimester as compared to 202 of the 1091 women (18.5%) who received MMI (RR=1.21, 95%CI 1.03 to 1.42). This difference is not clinically relevant.

4. Fertility

Not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

According to GRADE, observational studies start at a low level of evidence.

Fetal outcomes

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure fetal hypothyroidism was downgraded by three levels to very low because of unclear patient characteristics and no adjustment for confounders (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed both lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure fetal hyperthyroidism was downgraded by two levels to very low because of unclear patient characteristics and no adjustment for confounders (-1, risk of bias) and the optimal information size was not achieved (-1, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure small for gestational age/growth restriction/intrauterine growth retardation was downgraded by three levels to very low because of no adjustment for confounders (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed both lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm delivery was downgraded by two levels to very low because of no adjustment for confounders and groups were most likely not comparable (-2, risk of bias).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure intrauterine fetal death could not be assessed with GRADE since this outcome was not reported in the included studies.

Neonatal outcomes

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neonatal hypothyroidism was downgraded by one level to very low because the 95% confidence interval crossed the line of no (clinically relevant) effect (-1, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neonatal hyperthyroidism was downgraded by one level to very low because the optimal information size was not achieved (-1, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure NICU admission could not be assessed with GRADE since these outcomes were not reported in the included studies.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure congenital anomalies was downgraded by three levels to very low because groups most likely not comparable (-1, risk of bias) and differences in the direction of the effect (-1, inconsistency).

Maternal outcomes

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure risk of preeclampsia or HELLP was downgraded by three levels to very low because of no adjustment for confounders (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed both lines of no (clinically relevant) effect

(-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure recurrence of Graves’ disease during pregnancy and postpartum was downgraded by one level to very low because the 95% confidence interval crossed the line of no (clinically relevant) effect (-1, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures admission to ICU and fertility could not be assessed with GRADE since these outcomes were not reported in the included studies.

3. Radioiodine versus anti-thyroid drugs

Fetal outcomes

1. Fetal hypothyroidism

Not reported.

2. Fetal hyperthyroidism

Not reported.

3. Small for gestational age/growth restriction/intrauterine growth retardation

Zhang (2016) reported intrauterine growth restriction (not defined). Six of the 130 women (4.6%) who received radioactive iodine had a baby with intrauterine growth restriction as compared to 2 of the 127 women (1.6%) who received anti-thyroid drug therapy (RR=2.93, 95% CI 0.60 to 14.25). This difference is clinically relevant favoring anti-thyroid drug therapy.

4. Intrauterine fetal death

Yoshihara (2015) reported that 4 of the 283 women (1.4%) who received iodine had a perinatal loss as compared to 5 of the 1333 women (0.4%) who received methimazole (RR=3.77, 95%CI 1.02 to 13.94). This difference is clinically relevant favoring methimazole.

5. Preterm delivery

Zhang (2016) reported preterm birth (defined as ≥28 but <37 weeks). Twelve of the 130 women (9.8%) who received radioactive iodine had a preterm birth as compared to 11 of the 127 women (9.9%) who received anti-thyroid drug therapy (RR=1.07, 95% CI 0.49 to 2.33). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Neonatal outcomes

1. Neonatal hypothyroidism

Not reported.

2. Neonatal hyperthyroidism

Not reported.

3. NICU admission

Not reported.

4. Congenital anomalies

Zhang (2016) reported that one abortion was caused by cleft lip plus heart dysplasia in women who received radioactive iodine (0.8%) and one abortion occurred in women who received anti-thyroid drug therapy because of fetal congenital heart disease (0.8%) (RR=0.91, 95%CI 0.06 to 14.35). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Maternal outcomes

1. Admission to ICU

Not reported.

2. Risk of preeclampsia or HELLP

Not reported.

3. Recurrence of Graves’ disease during pregnancy and postpartum

Not reported.

4. Fertility

Not reported.

5. Long-term outcome of mother

Not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

According to GRADE, observational studies start at a low level of evidence.

Fetal outcomes

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure small for gestational age/growth restriction/intrauterine growth retardation was downgraded by three levels to very low because of no adjustment for confounders (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed both lines of no (clinically relevant) effect (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding intrauterine fetal death was downgraded by three levels to very low because of no adjustment for confounders (-1, risk of bias) and the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval was >3 times higher than the point estimate (-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm delivery was downgraded by three levels to very low because of no adjustment for confounders (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed both lines of no (clinically relevant) effect

(-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures fetal hypo- and hyperthyroidism could not be assessed with GRADE since these outcomes were not reported in the included studies.

Neonatal outcomes

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure congenital anomalies was downgraded by three levels to very low because of no adjustment for confounders (-1, risk of bias) and the 95% confidence interval crossed both lines of no (clinically relevant) effect

(-2, imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures neonatal hypo- and hyperthyroidism and NICU admission could not be assessed with GRADE since these outcomes were not reported in the included studies.

Maternal outcomes

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures admission to ICU, risk of preeclampsia or HELLP, recurrence of Graves’ disease during pregnancy and postpartum, and fertility could not be assessed with GRADE since these outcomes were not reported in the included studies.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes with different preconception treatment options for Graves' disease?

| P: | Women with Graves’ Disease wishing to conceive |

| I: |

Treatment (thyroid inhibitory medication [titration or block and replace], radioactive iodine [titration or ablation], thyroidectomy) |

| C: | Treatment with another intervention as listed under I |

| O: |

= Fetal outcomes (fetal hyperthyroidism, fetal hypothyroidism, small for gestational age/growth restriction/intrauterine growth retardation, intrauterine fetal death, preterm delivery) = Neonatal outcomes (neonatal hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, NICU admission, congenital anomalies) = Maternal outcomes (admission to ICU, risk of preeclampsia or HELLP, recurrence of Graves’ disease during pregnancy and postpartum, fertility) |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered the following fetal and neonatal outcomes as critical outcome measures for decision making: fetal/neonatal hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism, intrauterine fetal death and congenital anomalies. The following fetal, neonatal and maternal outcomes were considered important outcomes measures for decision making: small for gestational age/growth restriction/intrauterine growth retardation, preterm delivery, NICU admission, admission to ICU, risk of preeclampsia or HELLP, recurrence of Graves’ disease, and fertility.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies. Intrauterine fetal death and miscarriage were not clearly defined in the included studies. Therefore, also for this outcome measure, we used the definitions from the included studies.

The working group defined a 10% relative difference for intrauterine fetal death (RR < 0.9 or > 1.1) as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference. For the other outcomes, a 25% difference for dichotomous outcomes (RR < 0.8 or > 1.25) and 0.5 SD for continuous outcomes was taken as minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 7-7-2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 344 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review (that searched in at least two databases, included a detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies), randomized controlled trial, or observational studies;

- Studies according to PICO; and

- Full-text English language publication.

Eighty-six studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, seventy-six studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and ten observational studies were included.

Results

Ten observational studies were included in the analysis of the literature. One study compared thyroidectomy with radioiodine (Elston, 2014). Besides, seven studies compared propylthiouracil with methimazole (Harn-a-Morn, 2021; Korelitz, 2013; Momotani, 1997; Seo, 2018; Yoshihara, 2012; Yoshihara, 2014; Yoshihara, 2023), and two studies compared iodine with anti-thyroid drugs (Yoshihara, 2015; Zhang, 2016). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in table 1 and the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- 1 - Elston MS, Tu'akoi K, Meyer-Rochow GY, Tamatea JA, Conaglen JV. Pregnancy after definitive treatment for Graves' disease--does treatment choice influence outcome? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014 Aug;54(4):317-21.

- 2 - Harn-A-Morn P, Dejkhamron P, Tongsong T, Luewan S. Pregnancy Outcomes among Women with Graves' Hyperthyroidism: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2021 Sep 29;10(19):4495.

- 3 - Korelitz JJ, McNally DL, Masters MN, Li SX, Xu Y, Rivkees SA. Prevalence of thyrotoxicosis, antithyroid medication use, and complications among pregnant women in the United States. Thyroid. 2013 Jun;23(6):758-65.

- 4 - Momotani N, Noh JY, Ishikawa N, Ito K. Effects of propylthiouracil and methimazole on fetal thyroid status in mothers with Graves' hyperthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997 Nov;82(11):3633-6.

- 5 - Seo GH, Kim TH, Chung JH. Antithyroid Drugs and Congenital Malformations: A Nationwide Korean Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Mar 20;168(6):405-413.

- 6 - Yoshihara A, Noh J, Yamaguchi T, Ohye H, Sato S, Sekiya K, Kosuga Y, Suzuki M, Matsumoto M, Kunii Y, Watanabe N, Mukasa K, Ito K, Ito K. Treatment of graves' disease with antithyroid drugs in the first trimester of pregnancy and the prevalence of congenital malformation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Jul;97(7):2396-403.

- 7 - Yoshihara A, Noh JY, Watanabe N, Iwaku K, Kobayashi S, Suzuki M, Ohye H, Matsumoto M, Kunii Y, Mukasa K, Sugino K, Ito K. Frequency of Adverse Events of Antithyroid Drugs Administered during Pregnancy. J Thyroid Res. 2014;2014:952352.

- 8 - Yoshihara A, Noh JY, Watanabe N, Mukasa K, Ohye H, Suzuki M, Matsumoto M, Kunii Y, Suzuki N, Kameda T, Iwaku K, Kobayashi S, Sugino K, Ito K. Substituting Potassium Iodide for Methimazole as the Treatment for Graves' Disease During the First Trimester May Reduce the Incidence of Congenital Anomalies: A Retrospective Study at a Single Medical Institution in Japan. Thyroid. 2015 Oct;25(10):1155-61.

- 9 - Yoshihara A, Noh JY, Inoue K, Watanabe N, Fukushita M, Matsumoto M, Suzuki N, Suzuki A, Kinoshita A, Yoshimura R, Aida A, Imai H, Hiruma S, Sugino K, Ito K. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Neonatal Hypothyroidism Among Women with Graves' Disease Treated with Antithyroid Drugs Until Delivery. Thyroid. 2023 Mar;33(3):373-379.

- 10 - Zhang LH, Li JY, Tian Q, Liu S, Zhang H, Liu S, Liang JG, Lu XP, Jiang NY. Follow-up and evaluation of the pregnancy outcome in women of reproductive age with Graves' disease after 131Iodine treatment. J Radiat Res. 2016 Nov;57(6):702-708.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies

Research question: What is the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes with different preconception treatment options for Graves' disease?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Elston, 2014 |

Type of study: Retrospective chart review

Setting and country: Waikato Hospital, New Zealand

Funding and conflicts of interest: Supported by a Waikato Clinical School Summer Studentship awarded to Kelson Tu’akoi (funded by the Waikato District Health Board). No conflicts of interest reported.

|

Inclusion criteria: Women who had received definitive treatment for Graves’ disease and who were aged <45 years at the time of treatment.

Exclusion criteria: Not reported.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 12 Control: 17

Important prognostic factors2: Age (range): I: 28 years (21–38) C: 31 years (21–40)

TSH >4 mU/L at pregnancy diagnosis I: 3/19 (16%) C: 12/23 (52%)

Euthyroid around time conception I: 13/19 (68%) C: 5/23 (52%)

Groups not comparable.

|

Thyroidectomy

|

Radioiodine

|

Length of follow-up: Until delivery

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Intrauterine fetal death (miscarriages) I: 2/22 (9%) C: 6/27 (22%)

Fetal hyperthyroidism I: not reported C: 0

Neonatal hypothyroidism I: not reported C: 0

Neonatal hyperthyroidism I: 1/14 (7%) C: 0

Congenital anomaly I: not reported C: 1 |

Author’s conclusion: Adherence to the current American Thyroid Association guidelines is poor. Further education of both patients and clinicians is important to ensure that treatment of women during pregnancy after definitive treatment follows the currently available guidelines.

Remarks: - Small numbers - Additional pregnancies after definitive treatments not captured - Limited data on pregnancy outcomes |

|

Harn-a-morn, 2021

|

Type of study: Retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital, Thailand

Funding and conflicts of interest: The study was funded by The Thailand Research Fund (DPG6280003) and Chiang Mai University Research Fund (CMU-2564). The authors declare no conflict of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria: - Singleton pregnancy - Diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis, either before or during pregnancy, and being taken care of by endocrinologists which was defined as a decreased TSH level and an increased free T4 - Attending prenatal care and giving birth at Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital - No serious medical diseases such as pre-gestational diabetes, heart diseases, etc. - Known final obstetric outcomes - Thyrotoxicosis caused by Graves’ disease

Exclusion criteria: - Women with thyrotoxicosis caused by gestational thyrotoxicosis, Hashitoxicosis, toxic goiters, drug-induced and LT4 excess - Pregnancies complicated with other medical diseases - Incomplete medical records

N total at baseline: Intervention: 128 Control: 67

Important prognostic factors2: Gestational age I: 37.0 ± 4.2 C: 37.2 ± 2.5

Groups were probably comparable

|

Propylthiouracil |

Methimazole |

Length of follow-up: Until delivery (within 12 months of birth)

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Women with incomplete medical records were excluded.

|

Preeclampsia I: 11/128 (8.6%) C: 4/66 (6.1%)

Preterm birth I: 26/128 (20.3%) C: 15/66(22.7%)

Fetal growth restriction I: 16/126 (12.7%) C: 6/66 (9.1%) |

Author’s conclusion Thyrotoxicosis, whether treated or not needing ATDs, was significantly associated with an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Also, active disease, indicated by the need for ATD significantly increased the risk of such adverse outcomes; whereas the patients treated with MMI or PTU had comparable adverse outcomes.

Remarks - Small sample size - Women classified to ATD they took the most of the time during pregnancy

|

|

Korelitz, 2013

|

Type of study: Retrospective claims analysis

Setting and country: MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Support for this work was provided by NIH Grant R01HD65200. No competing financial interests exist.

|

Inclusion criteria: - Women between 15 and 44 years who were enrolled for at least 24 months with prescription drug benefits and had at least two pregnancy-related medical service claims between 2005 and 2009 - Linked infant records of women with delivered pregnancies

Exclusion criteria: Not reported.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 1533 Control: 1201

Important prognostic factors2: Not reported.

|

Propylthiouracil |

Methimazole |

Length of follow-up: Until delivery (within 12 months of birth)

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Congenital anomalies I: 66/915 (7.2%) C: 6/108 (5.6%)

|

Author’s conclusion: There was some indication of an elevated risk of liver disease and congenital anomalies in women with TTX, but the risk did not appear to be related to the ATD use. There seems to be a higher pregnancy termination rate for women with TTX on MMI, which likely reflects elective pregnancy terminations.

Remarks: Analyses are based exclusively on submitted health insurance claims without supplemental information or confirmation from medical charts. |

|

Momotani, 1997 |

Type of study: Prospective cohort study

Setting and country: Ito Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported

|

Inclusion criteria: - Pregnant women with Graves’ disease who continued PTU or MMI until delivery - Had taken the drugs for at least 4 weeks - Had normal free T4 levels at delivery - Delivered at term

Exclusion criteria: History of radioiodine therapy or surgery for Graves’ disease

N total at baseline: Intervention: 34 Control: 43

Important prognostic factors2: Not reported

Unclear if groups were comparable

|

Propylthiouracil (25–200 mg daily) |

Methimazole (2.5–20 mg daily) |

Length of follow-up: Until delivery

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Above normal fetal TSH (hypothyroidism) I: 7/34 (20.6%) C: 6/43 (14.0%)

Below normal fetal TSH (hyperthyroidism) I: 0 C: 2/43 (4.7%) |

Author’s conclusion When maternal FT4 levels are used as an index of fetal thyroid function, PTU and MMI are comparable in the treatment of hyperthyroidism due to Graves’ disease, at least in terms of the fetal thyroid.

Remarks: - No patient characteristics presented - Low number of participants |

|

Seo, 2018

|

Type of study: Nationwide cohort study

Setting and country: Korean National Health Insurance database

Funding and conflicts of interest: This study received no external funding. Authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest

|

Inclusion criteria: - Pregnant women aged 20 to 39 years who did not have prior childbirth records for at least 1 year before the date of delivery - Linked offspring records of women with delivered pregnancies

Exclusion criteria: Cases that could not be linked in the National Health Insurance database.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 9930 Control: 1120

Important prognostic factors2: Not reported for subgroup of PTU and MMI

Unknown if groups were comparable.

|

Propylthiouracil |

Methimazole |

Length of follow-up: Until delivery

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported |

Overall congenital malformations I: 699/9930 (7.04%) C: 91/1120 (8.13%) |

Author’s conclusion Exposure to ATDs during the first trimester was associated with increased risk for congenital malformations, particularly for pregnancies in which women received prescriptions for MMI or both ATDs.

Remarks The study used a prescription claims database to assess ATD exposure. |

|

Yoshihara, 2012 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: Ito Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

Funding and conflicts of interest: Source of funding not reported. The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

|

Inclusion criteria: Women with Graves’ disease who became pregnant.

Exclusion criteria: Not reported.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 1578 Control: 1426

Important prognostic factors2: Age± SD: I: 31.8 ± 4.3 years C: 32.9 ± 4.0 years

Unknown if groups were comparable

|

Propylthiouracil |

Methimazole |

Length of follow-up: Until delivery

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported |

Congenital malformations I: 26/1399 (1.9%) C: 50/1231 (4.1%)

Maternal hyperthyroidism during first trimester I: 277/1236 (21.9%) C: 202/1091 (18.5%) |

Author’s conclusion Exposure to MMI during the first trimester of pregnancy increased the risk of congenital anomalies, including the risk of the rare anomalies aplasia cutis congenita, omphalocele, and a symptomatic omphalomesenteric duct anomaly. It seems preferable to treat Graves’ disease with PTU because it appears to be safer to use in the fertile period; however, the reported risk of hepatotoxicity in both the mother and the child is a concern.

Remarks - Minor dysmorphic features may have been underreported - Questionnaire may have missed some abnormalities - Low number of participants

|

|

Yoshihara, 2014 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: Ito Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

Funding and conflicts of interest: Source of funding not reported. The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

|

Inclusion criteria Untreated pregnant women who came to the hospital for the first time and were newly diagnosed with Graves’ disease

Exclusion criteria Gestational transient thyrotoxicosis

N total at baseline: Intervention: 51 Control: 40

Important prognostic factors2: Not reported

Unknown if groups were comparable

|

Propylthiouracil |

Methimazole |

Length of follow-up: Until delivery

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported |

Preterm delivery I: 4/51 (7.8%) C: 3/40 (7.5%)

Congenital abnormality I: 0/51 C: 1/40 (2.5%) had omphalocele

|

Author’s conclusion Comparison with the expected rate of adverse events in nonpregnant individuals showed that the frequency of adverse events in pregnant individuals was low.

Remarks - Small number of subjects - Retrospective design |

|

Yoshihara, 2015 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: Ito Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

Funding and conflicts of interest: Source of funding not reported. The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

|

Inclusion criteria Women with Graves’ disease who were switched from MMI to inorganic iodide to control hyperthyroidism in the first trimester

Exclusion criteria Not reported

N total at baseline: Intervention: 283 Control: 1333

Important prognostic factors2: Maternal age (mean ± SD) I: 32.8 ± 4.6 C: 31.9 ± 4.3

Groups probably comparable

|

Iodine

KI was prescribed as an inorganic iodine dose of 10–30 mg/day in the form of a solution (10 mg of KI per drop of the infusion) or KI tablets (38 mg of KI per tablet). |

Methimazole |

Length of follow-up: Until delivery

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported. |

Congenital abnormality I: 4/260 (1.53%) C: 47/1134 (4.14%)

Perinatal loss I: 4/283 (1.4%) C: 5/1333 (0.4%)

Miscarriage I: 15/283 (5.3%) C: 164/1333 (12.3%) |

Author’s conclusion Substituting KI for MMI as a means of controlling hyperthyroidism in GD patients during the first trimester may reduce the incidence of congenital anomalies, at least in iodine-sufficient regions.

Remarks - Retrospective, nonrandomized study - Dose of KI at the time of substitution differed from patient to patient, and that the treatment protocol with KI varied in terms of continuation throughout pregnancy, the addition of ATD to KI, or the switch to an ATD after the second trimester of pregnancy. - Subjects were Japanese women, whose dietary iodine intake is higher than in most other countries

|

|

Yoshihara, 2023 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: Ito Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding was received for this article. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report in regard to this study.

|

Inclusion criteria: Women with Graves’ Disease treated with methimazole (MMI) or propylthiouracil (PTU) who required ATD therapy to control thyrotoxicosis until delivery and gave birth

Exclusion criteria: Not reported.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 242 Control: 63

Important prognostic factors2: Unclear if groups were comparable at baseline (only presented at delivery)

|

Propylthiouracil (cut-off dose 150 mg/day) |

Methimazole (cut-off dose 10 mg/day)

|

Length of follow-up: Until delivery

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported. |

Neonatal hypothyroidism I: 31/242 (12.8%) C: 12/63 (19%)

Neonatal hyperthyroidism I: 3/242 (1.2%) C: 0

|

Author’s conclusion: Maternal fT4 and TRAb levels were higher in the neonatal hypothyroid group, which suggested prolonged GD activity. Careful follow-up is necessary when maternal GD remains active and the ATD dose to control maternal thyrotoxicosis cannot be reduced.

Remarks: - Retrospective nature - Selection bias for more severe cases as hospital specializes in thyroid disease - Small number of patients

|

|

Zhang, 2016 |

Type of study: Retrospective study

Setting and country: Nuclear Medicine Department, Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, Japan.

Funding and conflicts of interest: Source of funding not reported. The authors report that there are no conflicts of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria: Women with Graves’ disease who became pregnant at least six months after 131I therapy or antithyroid drug (ATD) treatment for hyperthyroidism.

Exclusion criteria: Not reported.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 130 Control: 127

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD I: 28.90 ± 3.69 C: 29.21 ± 3.90

Unclear if groups were comparable at baseline.

|

131I therapy |

Anti-thyroid drug therapy |

Length of follow-up: Until delivery

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Intrauterine growth restriction I: 6/130 (4.6%) C: 2/127 (1.6%)

Preterm birth I: 12/130 (9.8%) C: 11/127 (9.9%)

Congenital malformations I: 1/130 (0.8%) à harelip plus heart dysplasia C: 1/118 (0.8%) à fetal congenital heart disease |

Author’s conclusion: Women with hyperthyroidism who were treated with 131I therapy could have normal delivery if they ceased 131I treatment for at least six months prior to conception and if their thyroid function was reasonably controlled and maintained using the medication: anti-thyroid drug and levothyroxine before and during pregnancy.

Remarks: - Details on delivery outcomes were narrow and no specific information about newborns - Lack of follow-up data |

Risk of bias table for interventions studies

|

Author, year |

Selection of participants

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population?

|

Exposure

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?

|

Outcome of interest

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study?

|

Confounding-assessment

Can we be confident in the assessment of confounding factors?

|

Confounding-analysis

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these confounding variables?

|

Assessment of outcome

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome?

|

Follow up

Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? In particular, was outcome data complete or imputed?

|

Co-interventions

Were co-interventions similar between groups?

|

Overall Risk of bias

|

|

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Low, Some concerns, High |

|

|

Elston, 2014 |

Probably yes

Reason: Participants were selected from same hospital. |

Probably yes

Reason: Derived from database. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcome of interest could not be present before the study starts because it is related to the pregnancy.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Characteristics were probably derived from databases. |

Probably no

Reason: No adjustment for confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes probably derived from databases. |

Probably yes

Reason: No missing data. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other interventions. |

Some concerns |

|

Harn-a-morn, 2021

|

Probably yes

Reason: Participants were selected from same hospital.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Derived from medical records. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcome of interest related to pregnancy. |

Probably no

Reason: Only limited information about patient characteristics was provided for both groups separately.

|

Probably no

Reason: Cases with confounding factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes existing before pregnancy were excluded, but no multivariate analysis was performed.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Derived from medical records. |

Probably yes

Reason: Incomplete medical records were excluded. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other interventions |

Some concerns |

|

Korelitz, 2013 |

Probably yes

Reason: Participants selected from same database. |

Probably yes

Reason: Medication use was based on the prescription fill date on a submitted claim.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Outcome of interest related to pregnancy and exposure to drug during pregnancy.

|

Definitely no

Reason: No patient characteristics were provided.

|

Definitely no

Reason: No adjustment for confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: Adverse events were identified using the diagnosis (ICD-9-CM) codes from outpatient and inpatient claims.

|

Probably yes

Reason: No missing data. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other interventions.

|

High |

|

Momotani, 1997 |

Probably yes

Reason: Total population divided into exposed and non-exposed.

|

Probably yes

Reason: It was stated how many women were exposed. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcome of interest related to pregnancy. |

Definitely no

Reason: No patient characteristics were provided. |

Definitely no

Reason: No adjustment for confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: Described how hormone levels were determined. |

Probably yes

Reason: No missing data. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other interventions. |

High |

|

Seo, 2018 |

Probably yes

Reason: Participants selected from same database.

|

Probably yes

Reason: A prescription claims database was used to assess ATD exposure.

|

Definitely yes

Reason: Outcome of interest related to pregnancy. |

Definitely no

Reason: No patient charcteristics were provided for both interventions separately. |

Probably yes

Reason: Adjusted for potential confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: Derived from database. |

Probably yes

Reason: No missing data. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other interventions. |

Some concerns |

|

Yoshihara, 2012 |

Probably yes

Reason: Participants were selected from same hospital.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Cases were reviewed and women were divided in groups according to exposure.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Outcome of interest related to pregnancy. |

Probably yes

Reason: Some patient characteristics were provided. |

Probably yes

Reason: Multivariate analysis was performed. |

Probably yes

Reason: Diagnosed by the obstetricians, using a structured questionnaire.

|

Probably yes

Reason: No missing data. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other interventions. |

Low |

|

Yoshihara, 2014

|

Probably yes

Reason: Participants were selected from same hospital.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Charts were reviewed. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcome of interest related to pregnancy. |

Probably no

Reason: Only characteristics were provided for the groups ‘without adverse events’ and ‘with adverse events’; not for the comparison between treatments.

|

Probably no

Reason: No adjustment for confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: Derived from charts. |

Probably yes

Reason: No missing data. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other interventions. |

High |

|

Yoshihara, 2015 |

Probably yes

Reason: Participants were selected from same hospital.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Cases were reviewed. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcome of interest related to pregnancy. |

Probably yes

Reason: Some characteristics were provided. |

Probably no

Reason: No adjustment for confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: Cases were reviewed. |

Probably yes

Reason: No missing data. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other interventions. |

Some concerns |

|

Yoshihara, 2023 |

Probably yes

Reason: Participants were selected from same hospital.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Derived from medical records. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcome of interest releated to pregnancy. |

Probably yes

Reason: Characteristics were probably extracted from medical records.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Multivariate analyses were performed. |

Probably yes

Reason: Described how hormone levels were determined and how outcome was diagnosed.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Missing data did not affect the results of multivariate analysis. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other interventions. |

Low |

|

Zhang, 2016 |

Probably yes

Reason: Participants were selected from same hospital. |

Probably yes

Reason: Derived from medical records. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcome of interest could not be present before the study starts because it is related to the pregnancy.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Characteristics were probably derived from medical records.

|

Probably no

Reason: No adjustment for confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes probably derived from medical records. |

Probably yes

Reason: No missing data.

|

Probably yes

Reason: No other interventions. |

Some concerns |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Abdi H, Amouzegar A, Azizi F. Antithyroid Drugs. Iran J Pharm Res. 2019 Fall;18(Suppl1):1-12. doi: 10.22037/ijpr.2020.112892.14005. PMID: 32802086; PMCID: PMC7393052. |

Narrative review |

|

Ahmad S, Geraci SA, Koch CA. Thyroid disease in pregnancy: (Women's Health Series). South Med J. 2013 Sep;106(9):532-8. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3182a66610. PMID: 24002560. |

Narrative review |

|

Alamdari S, Azizi F, Delshad H, Sarvghadi F, Amouzegar A, Mehran L. Management of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy: comparison of recommendations of american thyroid association and endocrine society. J Thyroid Res. 2013;2013:878467. doi: 10.1155/2013/878467. Epub 2013 May 22. PMID: 23762777; PMCID: PMC3674680. |

Narrative review |

|

Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, Brown RS, Chen H, Dosiou C, Grobman WA, Laurberg P, Lazarus JH, Mandel SJ, Peeters RP, Sullivan S. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Disease During Pregnancy and the Postpartum. Thyroid. 2017 Mar;27(3):315-389. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0457. Erratum in: Thyroid. 2017 Sep;27(9):1212. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0457.correx. PMID: 28056690. |

Guidelines |

|

Ashkar C, Sztal-Mazer S, Topliss DJ. How to manage Graves' disease in women of childbearing potential. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2023 May;98(5):643-648. doi: 10.1111/cen.14705. Epub 2022 Mar 8. PMID: 35192205. |

Narrative review |

|

Azizi F, Khamseh ME, Bahreynian M, Hedayati M. Thyroid function and intellectual development of children of mothers taking methimazole during pregnancy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2002 Jul-Aug;25(7):586-9. doi: 10.1007/BF03345080. PMID: 12150331. |

No comparison |

|

Banigé M, Estellat C, Biran V, Desfrere L, Champion V, Benachi A, Ville Y, Dommergues M, Jarreau PH, Mokhtari M, Boithias C, Brioude F, Mandelbrot L, Ceccaldi PF, Mitanchez D, Polak M, Luton D. Study of the Factors Leading to Fetal and Neonatal Dysthyroidism in Children of Patients With Graves Disease. J Endocr Soc. 2017 Jun;1(6):751-761. doi: 10.1210/js.2017-00189. Epub 2017 Apr 25. PMID: 29130077; PMCID: PMC5677510. |

No treatment |

|

Bartalena L, Burch HB, Burman KD, Kahaly GJ. A 2013 European survey of clinical practice patterns in the management of Graves' disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016 Jan;84(1):115-20. doi: 10.1111/cen.12688. Epub 2015 Jan 9. PMID: 25581877. |

Wrong study design: survey (no comparison of treatments) |

|

Bartalwar A, Dakode S. Thyrotoxicosis In Pregnant Females, Use Of ATD’S And Fetal Outcomes. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results. 2022 Dec 31:8296-300. |

No comparison between treatments |

|

Becks GP, Burrow GN. Thyroid disease and pregnancy. Med Clin North Am. 1991 Jan;75(1):121-50. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30475-8. PMID: 1987439. |

Narrative review |

|

Besançon A, Beltrand J, Le Gac I, Luton D, Polak M. Management of neonates born to women with Graves' disease: a cohort study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014 Jun;170(6):855-62. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0994. Epub 2014 Mar 26. PMID: 24670885. |

No treatment |

|

Boger MS, Perrier ND. Advantages and disadvantages of surgical therapy and optimal extent of thyroidectomy for the treatment of hyperthyroidism. Surg Clin North Am. 2004 Jun;84(3):849-74. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2004.01.006. PMID: 15145239. |

Narrative review |

|

Borrás-Pérez MV, Moreno-Pérez D, Zuasnabar-Cotro A, López-Siguero JP. Neonatal hyperthyroidism in infants of mothers previously thyroidectomized due to Graves' disease. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2001 Sep-Oct;14(8):1169-72. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2001-0817. PMID: 11592578. |

No comparison |

|

Caron P. Prévention des désordres thyroïdiens au cours de la grossesse [Prevention of thyroid disorders in pregnant women]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2009 Nov;38(7):574-9. French. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2008.12.006. Epub 2009 Oct 8. PMID: 19818566. |

Article in French |

|

Chattaway JM, Klepser TB. Propylthiouracil versus methimazole in treatment of Graves' disease during pregnancy. Ann Pharmacother. 2007 Jun;41(6):1018-22. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H535. Epub 2007 May 15. PMID: 17504839. |

Narrative review |

|

Corssmit EP, Wiersinga WM, Boer K, Prummel MF. Pregnancy (conception) in hyper-or hypothyroidism. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde. 2001 Apr 1;145(15):727-31. |

Narrative review |

|

Corssmit EP, Wiersinga WM, Boer K, Prummel MF. Pregnancy or a desire to become pregnant in patients with hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde. 2001; 145(15):727-731 |

Narrative review |

|

Davies TF, Andersen S, Latif R, Nagayama Y, Barbesino G, Brito M, Eckstein AK, Stagnaro-Green A, Kahaly GJ. Graves’ disease. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2020; 6(1). |

Narrative review |

|

Dhillon-Smith RK, Boelaert K. Preconception Counseling and Care for Pregnant Women with Thyroid Disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2022 Jun;51(2):417-436. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2021.12.005. Epub 2022 May 4. PMID: 35662450. |

Narrative review |

|

Del Campo Cano I, Alarza Cano R, Encinas Padilla B, Lacámara Ornaechea N, Royuela Vicente A, Marín Gabriel MÁ. A prospective study among neonates born to mothers with active or past Graves disease. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2022 Jun;38(6):495-498. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2022.2073347. Epub 2022 May 12. PMID: 35548945. |

No comparison between treatments |

|

Dumitrascu MC, Nenciu AE, Florica S, Nenciu CG, Petca A, Petca RC, Comănici AV. Hyperthyroidism management during pregnancy and lactation (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2021 Sep;22(3):960. doi: 10.3892/etm.2021.10392. Epub 2021 Jul 7. PMID: 34335902; PMCID: PMC8290437. |

Narrative review |

|