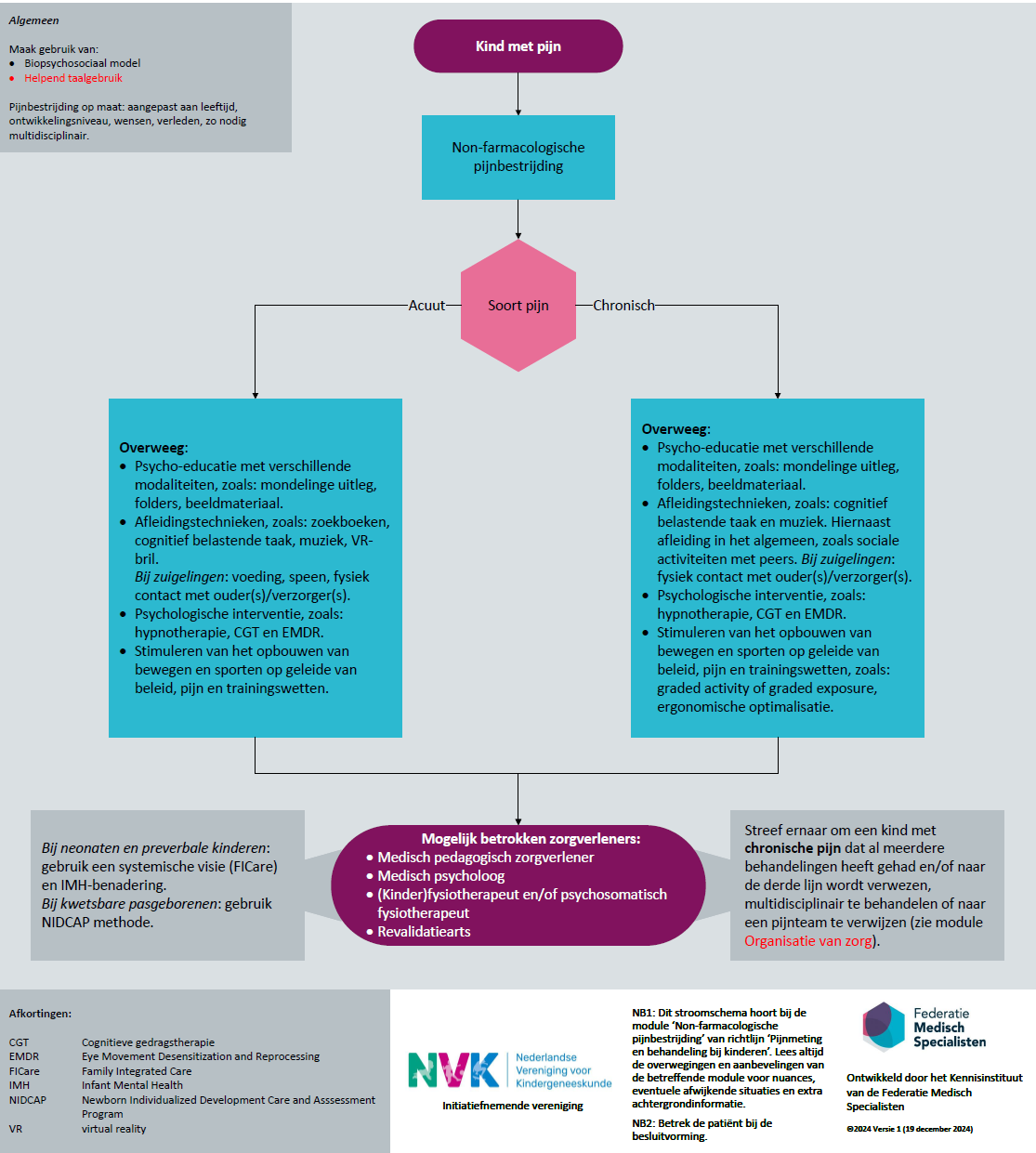

Non-farmacologische pijnbestrijding

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de meerwaarde van non-farmacologische pijnbestrijding bij de behandeling van kinderen met pijn?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik bij alle vormen van pijn altijd non-farmacologische pijnbestrijding. Baseer de pijnbestrijding primair op het biopsychosociaal model, waarbij de situatie op alle domeinen (biologische, psychologische en sociale factoren) zoveel mogelijk genormaliseerd wordt.

Gebruik standaard helpend taalgebruik om verwachtingen en pijn cognities van ouders en kind op een positieve manier te beinvloeden.

Geef non-farmacologische pijnbestrijding aangepast op maat, afhankelijk van de leeftijd en ontwikkelingsniveau van het kind, de wensen van ouder en kind, en wat in het verleden al is toegepast en zo nodig multidisciplinair (zie figuur 2 Stroomschema).

Overweeg in het geval van acute pijn en chronische pijn de volgende mogelijkheden (zie ook figuur 2 Stroomschema):

- Psychoeducatie;

- Afleidingstechnieken;

- Psychologische interventie;

- Stimuleren van het opbouwen van het activiteiten- en participatieniveau.

Hierbij kunnen de volgende zorgverleners betrokken worden: medisch pedagogisch zorgverlener, medisch psycholoog, (kinder)fysiotherapeut en/of psychosomatisch fysiotherapeut, revalidatiearts.

Streef ernaar om een kind met chronische pijn dat al meerdere behandelingen heeft gehad en/of naar de derde lijn wordt verwezen, multidisciplinair te behandelen of naar een pijnteam te verwijzen (zie module Organisatie van zorg).

Gebruik voor postoperatieve pijn en Sedatie, Analgesie en niet-farmacologische interventies voor begeleiding van kinderen bij medische procedures desbetreffende richtlijnen.

Gebruik voor aandoeningsspecifieke behandeling van pijn desbetreffende richtlijnen, zoals functionele buikpijn bij kinderen, somatisch onvoldoende verklaarde klachten (SOLK) bij kinderen

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In deze literatuursamenvatting is naar verschillende vormen non-farmacologische pijnbestrijding gekeken voor kinderen met acute en chronische pijn. Er is onderscheid gemaakt tussen psycho-educatie, afleidingstechnieken, ,helpend taalgebruik, fysieke interventies, psychologische en andere non-farmacologische interventies.

Voor de non-farmacologische techniek psycho-educatie werden vooral studies geïncludeerd die gebruik maakten van cognitieve gedragstherapie, psychologische behandelingen en biofeedback. Er was wel overlap in de geïncludeerde studies tussen de reviews, want Abbott (2017), Abbott (2018) en Gordon (2022) includeerden veel dezelfde studies. Hierbij werd gevonden dat psycho-educatie mogelijk effectief is en pijn kan verminderen, maar geen effect heeft op functioneren en kwaliteit van leven. Echter is de bewijskracht hiervan laag, wat voornamelijk wordt veroorzaakt doordat studiedeelnemers niet geblindeerd waren (risico op vertekening).

De studies die onderzoek deden naar afleidingstechnieken maakten gebruik van luisteren naar muziek. De review van See (2023) includeerde dezelfde artikelen als de review van Ting (2022). Voor de uitkomstmaten pijn en angst lijkt de kwaliteit van het bewijs onvoldoende om conclusies te kunnen trekken over de effecten van afleidingstechnieken. De kwaliteit van bewijs is voor deze uitkomsten zeer laag, wat met name het gevolg is van het niet blinderen van studiedeelnemers (risico op vertekening) en kleine en weinig studies. Er werden geen studies gevonden die de andere uitkomstmaten hebben gemeten. Daarom kan er geen conclusie worden getrokken over de effectiviteit van afleidingstechnieken bij kinderen.

De studies die psychologische interventies onderzochten, gingen over psychologische therapie of hypnotherapie. Er was wel overlap in de geïncludeerde studies tussen de reviews, want Abbott (2017), Abbott (2018) en Gordon (2022) includeerden veel dezelfde studies. Voor psychologische behandelingen werd geen effect gevonden op angst (gemiddelde bewijskracht) en kwaliteit van leven (lage bewijskracht) bij kinderen. Psychologische interventies zouden mogelijk pijn kunnen verminderen, maar de bewijskracht hiervan is laag. Er werd onvoldoende kwaliteit van bewijs gevonden om een conclusie te kunnen trekken over het effect op functioneren. De lagere kwaliteit van bewijs werd met name veroorzaakt door risico op vertekening en tegenstrijdige resultaten. Het bewijs over de effecten van hypnotherapie op pijn en kwaliteit van leven is van zeer lage kwaliteit, waardoor hier geen conclusies over kunnen worden getrokken.

In de literatuuranalyse werden studies geïncludeerd die gebruik maakten van relaxatie en gevoelsdagboek. Hierbij werd gevonden dat relaxatie mogelijk effectief is, maar de bewijskracht hiervan is laag. Het bewijs over de effecten van gevoelsdagboek op pijn en kwaliteit van leven is van zeer lage kwaliteit, waardoor hier geen conclusies over kunnen worden getrokken. De lage tot zeer lage bewijskracht wordt voornamelijk veroorzaakt door risico op vertekening door het niet blinderen van studiedeelnemers, kleine en weinig studies en heterogeniteit in de resultaten.

In de geïncludeerde reviews werd geen onderscheid gemaakt tussen de vier vooraf gedefinieerde subgroepen. De reviews van Abbott et al. (2017), Gordon et al. (2022) en Abbott et al. (2018) includeerden allen studies in kinderen tussen de 5 en 18 jaar. De overige studies includeerden kinderen onder de 18 of 21 jaar. Er is met behulp van ASReview nog gekeken naar eventuele observationele studies en RCTs voor de subgroep neonaten en pre-verbale kinderen, maar er zijn helaas geen studies gevonden in deze subgroep die voldoen aan de PICO. Daarnaast werden er geen studies gevonden die de belangrijke uitkomstmaten (opnameduur en kosten) meenamen als uitkomstmaat.

Samenvattend kan er op basis van de resultaten met lage bewijskracht richting gegeven worden aan de besluitvorming. Psycho-educatie, relaxatie en psychologische interventies kunnen een positief effect hebben op het verminderen van acute en chronische pijn bij kinderen. Er werd onvoldoende kwaliteit van bewijs gevonden om iets te kunnen concluderen over de effectiviteit van afleidingstechnieken, hypnotherapie, gevoelsdagboek en fysieke interventies.

De werking van non-farmacologische pijnbestrijding op pijnreductie is niet altijd duidelijk. Non-farmacologische interventies kunnen relatief eenvoudig toegevoegd worden aan bestaande medicamenteuze interventies. Indien interventies een positief effect hebben op bijvoorbeeld angst en spanning, zal dit ook de ervaren pijn positief kunnen beïnvloeden. Non-farmacologische pijnbestrijding dienen te worden aangepast aan leeftijd en ontwikkelingsniveau van het kind.

In de huidige praktijk worden reeds veel verschillende non-farmacologische pijnbehandelingen toegepast. Keuzes en een plan op maat voor een kind kunnen ook effect op zelfredzaamheid en autonomie heben. Dit in het kader van gezamenlijke besluitvoering.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het is van belang dat het gehele multidisciplinaire team dezelfde taal spreekt en hetzelfde verklaringsmodel/psychoeducatie uitdraagt naar het kind en zijn of haar gezin. Hierbij wordt het gebruik van helpend taalgebruik geadviseerd. Non-farmacologische technieken kunnen bijdragen aan de ontspanning en afleiding van de patiënt waardoor angst kan verminderen en comfort en patiënttevredenheid kan toenemen. Hieronder worden voor verschillende patiëntengroepen uit de PICO specifieke aandachtspunten benoemd.

Verbale kinderen en adolescenten

Goede psycho/pijneducatie voor het kind en zijn of haar gezin is van belang. Aangeraden wordt hierbij van verschillende modaliteiten gebruik te maken, denk hierbij aan mondelinge uitleg met gebruik van bijvoorbeeld metaforen, folders en beeldmateriaal.

Juist de behandeling afgestemd op de individuele patiënt, rekening houdend met kindfactoren, gezinsfactoren en omgevingsfactoren (biopsychosociaal model), gericht op het optimaliseren van de omstandigheden zodat de pijnklachten kunnen reduceren (gevolgenmodel) en het functioneringsniveau van het kind wordt vergroot, passend bij het ontwikkelingsniveau van het kind, is belangrijk.

Denk hierbij aan het doel weer volledig onderdeel zijn van de maatschappij, waar het kind net als zijn leeftijdsgenoten naar school gaat, kan spelen met vrienden en andere activiteiten kan ondernemen.

Herstel belemmerende factoren dienen hierbij in kaart te worden gebracht, zoals faseproblematiek, ontwikkelingsproblematiek (bijvoorbeeld ASS en ADHD) en problemen op het gebied van voeding, slapen, school, cognitie en stemming (bijvoorbeeld catastroferende gedachten, angst en somberheid).

Zo kan bijvoorbeeld bij het ene kind EMDR (psychologische traumabehandeling) op basis van wat hij heeft meegemaakt een onderdeel van het behandelplan zijn, terwijl voor het andere kind medicatie en activering middels kinderfysiotherapeutische begeleiding meer op de voorgrond staat.

De systemische visie (Family Integrated Care (FICare)/Samenzorg) is in het geval van kinderen van groot belang. Het kind kan niet los van zijn ouders/gezin/systeem worden gezien. Ouders spelen een zeer belangrijke rol in het ondersteunen van hun kind. Het kan echter ook voorkomen dat ouders onvoldoende ondersteuning kunnen bieden of belemmerde factoren in stand houden en dan dient naar alternatieven te worden gekeken.

Overweeg bij onvoldoende vooruitgang een revalidatietraject.

Preverbale kinderen/neonaten

Voor de allerjongste groep, preverbale kinderen, is het belangrijk om vanuit de Infant Mental Health (IMH) gedachte het kind en zijn of haar ouders te benaderen. Hierbij staat het oog hebben voor het samenspel tussen omgeving, biologische factoren en de ouder-kindrelatie centraal. Aanwezigheid van ouders is bijvoorbeeld van groot belang indien mogelijk en daarnaast is toepassen van de NIDCAP methode (Newborn Individualized Development Care and Asssessment Program)/ontwikkelingsgerichte zorg essentieel in de zorg van een kwetsbare pasgeborene.

Vanuit onderzoek naar non-farmacologische interventies bij procedurele pijn bij neonaten weten we dat onder andere huid-op-huid contact (kangaroo care of skin to skin care), begrenzing bieden, borstvoeding en het zuigen op een speen (met sucrose) pijn verlagend werken. We adviseren deze interventies tevens te overwegen in het geval van pijn niet gerelateerd aan procedures ondanks het ontbreken van overtuigend bewijs hiervoor.

Kinderen met neurobiologische ontwikkelingsstoornissen

Naast veel van bovenstaande overwegingen is het specifiek voor kinderen met neurobiologische ontwikkelingsstoornissen van belang om comfort te bieden, bijvoorbeeld door het bieden van ergonomische optimalisatie, detonisatie en/of afleiding. Ouders/verzorgers dienen expliciet betrokken te worden bij kinderen met neurobiologische ontwikkelingsstoornissen gezien hun ervaringsperspectief in hoe comfort het beste aan het individuele kind geboden kan worden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Non-farmacologische pijnbestrijdingstechnieken en materialen worden al veel ingezet in ziekenhuizen, maar dienen verder geoptimaliseerd te worden. Dit kan gepaard gaan met extra kosten, zoals kosten voor scholing en materiaalkosten. Tevens kan gedacht worden aan personeelskosten wanneer bv uren medisch pedagogisch zorgverlener wordt uitgebreid. Er is weinig bekend over de kosteneffectiviteit van deze interventies. De interventies lijken over het algemeen eenvoudig uitvoerbaar en de kosten lijken beperkt. Daardoor zou het een relatief goedkope manier zijn om de patiëntbeleving positief te beïnvloeden. Er zou meer kwalitatief goed onderzoek gedaan kunnen worden, bijvoorbeeld door het vergelijken van twee non-farmacologische technieken of bij verschillende doelgroepen. Tevens zou een passende DBC structuur met verzwaring bij extra kosten hierin kunnen bijdragen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Naast het ruime aanbod van non-farmacologische technieken is de keuze ook afhankelijk van de voorkeur van het kind en zijn/haar ouders. Door hen te betrekken bij de keuze voor en bepaalde techniek kan een passende keus worden gemaakt waardoor de kans op een positief effect en toename van de patiënttevredenheid wordt vergroot

Belangrijk is dat de zorgverleners op de hoogte zijn van de mogelijkheden en getraind zijn in de non-farmacologische technieken die lokaal worden toegepast.

Voor het toepassen van non-farmacologische technieken en materialen is vaak scholing nodig, bijvoorbeeld bij het gebruik van helpend taalgebruik. Als een VR bril wordt gebruikt moet rekening gehouden worden met benodigde software, abonnementen, trainingen, beschikbaarheid van brillen. Dit kan mogelijk een barrière zijn voor implementatie.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies.

In de literatuursearch van deze module is gebruik gemaakt van de vergelijking van non-farmacologische met farmacologische pijnbestrijding. Hierbij is voorbijgegaan aan het additieve effect van non-farmacologische pijnbestrijding.

Voor postoperatieve pijn en procedurele sedatie en analgesie (PSA) wordt verwezen naar desbetreffende richtlijnen. Voor aandoeningsspecifieke behandeling van pijn wordt verwezen naar desbetreffende richtlijnen, zoals functionele buikpijn bij kinderen en hoofdpijn (bij volwassenen).

Overweeg bij alle vormen van pijn bij kinderen altijd non-farmacologische en farmacologische pijnbestrijding. Hierbij is het biopsychosociaal model belangrijk. Zowel biologische, psychologische als sociale factoren spelen een rol bij pijn, pijnbeleving en pijnbestrijding. Leg aan ouder(s)/verzorger(s) en kinderen uit wat maakt dat dit werkt (naast farmacologische interventie) om te voorkomen dat zij zich niet serieus genomen voelen en weten waarom en wanneer zij dit in kunnen zetten.

Door aandacht te besteden aan alle relevante factoren ontstaat een deecsalerend effect op de pijnbeleving. Het is dan ook van belang dat de twee vormen van behandeling, zowel non-farmacologisch als farmacologisch, samen gaan voor het behandelen van pijn bij kinderen. Non-farmacologische pijnbestrijding is relatief makkelijk in te zetten en geeft weinig tot geen bijwerkingen. Een goed voorbeeld hiervan zijn afleidende technieken die naar mening van de werkgroep ondanks gebrek aan bewijs wel aanbevolen worden. Te denken valt aan zoekboeken, cognitief belastende taak, muziek, VRbril. Bij zuigelingen voeding, speen en fysiek contact met ouders.

Vanuit expert opinion wordt sterk aanbevolen multidisciplinair te werk te gaan, waarbij men vanuit de gezamenlijkheid van verschillende disciplines, zoals artsen, verpleegkundigen, medisch pedagogisch zorgverleners, fysiotherapeuten en psychologen, een behandelplan opstelt, evalueert en zo nodig bijstelt. Bepaal met elkaar welke non-farmacologische pijnbestrijdingstechieken kunnen worden toegepast, zodat keuzeopties bekend zijn, dezelfde taal gesproken wordt en voorzien kan worden in de bijbehorende materialen en scholing.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Non-pharmacological pain management involves methods of pain management in children that do not involve the use of pharmacological agents, such as analgesics. Non-pharmacological pain management includes a wide range of techniques and interventions that aim to reduce or control pain without the use of medication. This can range from psychological interventions, physiotherapy, and alternative therapies to simple comfort measures such as distraction, communication and reassurance.

Communication is the exchange of thoughts, messages, or information, as by speech, signals, writing, and/or behavior.

For the non-pharmacological treatment of pain in children undergoing a procedure, we refer to the modules on non-pharmacological (psychological and physical) techniques for procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) in children.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Psychoeducation

|

Low GRADE |

Psychoeducation ((self-administered) psychological treatment/ biofeedback) might be more effective on migraine related outcomes (headache days per month, number of migraine days per month, frequency of headache attacks, frequency of migraine attacks, and headache index and activity) than waitlist control in children aged <18 years.

Source: Koechlin, 2021 |

|

Low GRADE |

Psychoeducation (cognitive behaviour therapy) might reduce pain compared with control in children aged 5 to 18 years.

Source: Abbott, 2017; Abbott, 2018; Gordon, 2022 |

|

Low GRADE |

Psychoeducation (cognitive behaviour therapy) might have no effect on functioning compared with control in children with recurrent abdominal pain aged 5 to 18 years.

Source: Abbott, 2017 |

|

Low GRADE |

Psychoeducation (cognitive behaviour therapy) might have no effect on quality of life compared with control in children with recurrent abdominal pain aged 5 to 18 years.

Source: Abbott, 2017 |

Distraction techniques

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of distraction techniques (music listening) on pain compared with control in children aged ≤21 years.

Source: e, 2023; Ting, 2022 |

Physical interventions

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of physical interventions (physical therapy/ yoga) on pain compared with control in children aged ≤19 years.

Source: Abbott, 2017; Fisher, 2022; Gordon, 2022 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of physical interventions (physical therapy) on anxiety compared with control in children aged ≤19 years.

Source: Fisher, 2022 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of physical interventions (physical therapy/ yoga) on functioning compared with control in children aged ≤19 years.

Source: Abbott, 2017; Fisher, 2022 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of physical interventions (physical therapy) on quality of life compared with control in children aged ≤19 years.

Source: Fisher, 2022 |

Psychological interventions

|

Low GRADE |

Psychological interventions (psychological therapy) might reduce pain compared with control in children aged ≤19 years.

Source: Fisher, 2022 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Psychological interventions (psychological therapy) probably have no effect on anxiety compared with control in children aged ≤19 years.

Source: Fisher, 2022 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of psychological interventions (psychological therapy) on functioning compared with control in children aged ≤19 years.

Source: Fisher, 2022 |

|

Low GRADE |

Psychological interventions (psychological therapy) might have no effect on quality of life compared with control in children aged ≤19 years.

Source: Fisher, 2022 |

Other non-pharmacological interventions

|

Low GRADE |

Relaxation might be more effective on migraine related outcomes (headache days per month, number of migraine days per month, frequency of headache attacks, frequency of migraine attacks, and headache index and activity) than waitlist control in children aged <18 years.

Source: Koechlin, 2021 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of written self-disclosure on pain compared with control in children aged 5 to 18 years.

Source: Abbott, 2017 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of hypnotherapy on pain compared with control in children aged 5 to 18 years.

Source: Abbott, 2017; Abbott, 2018; Gordon, 2022 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Distraction techniques

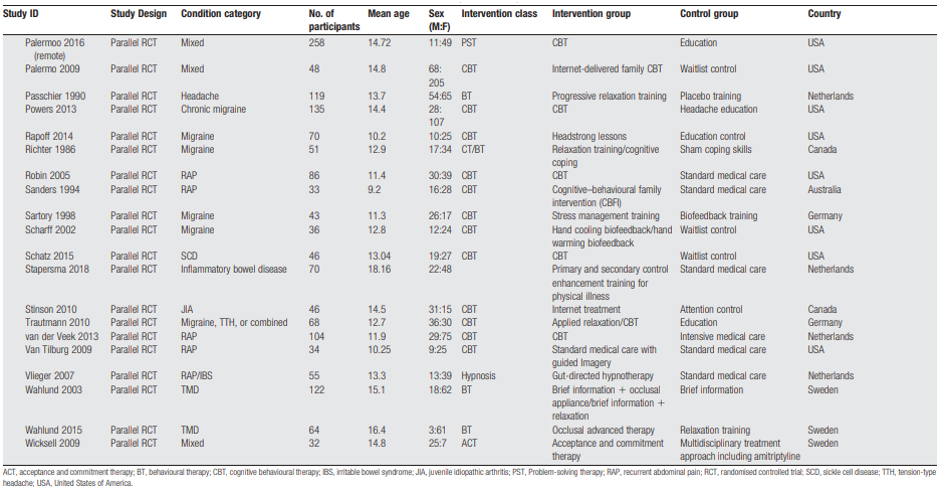

See (2023) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs, quasi-experimental studies, cohort studies, case-control studies, and pilot studies, to estimate the effect of music interventions on pain, compared with standard care in paediatric, adult, and elderly patients visiting the emergency department (ED) for any condition. We only reported the results on paediatric patients. This review reported pain and included 11 studies, of which three studies focused on the paediatric population (≤21 years). Two of the three included studies (Hartling et al., 2013 and van der Heijden et al., 2019) were also included in the review of Ting (2022). Two studies were included in the meta-analysis. The review found no significant effect on pain. The evidence was of very low quality, due to lack of blinding, inconsistency, indirectness, and imprecision. The results from this review are summarized in Table 2.

Ting (2022) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs, quasi-experimental studies, cohort studies, case-control studies, and pilot studies to estimate the effect of listening to music, compared with music control in patients <18 years in various clinical settings. Although the comparison was described as music control, the authors described that the control group may not receive any components of music (i.e., rhythm, melody, and harmony). This review reported pain release and included 38 studies, of which 8 articles were in children with postoperative pain. We only reported these results, because chronic/procedural and prick pain does not comply with the PICO. In general, a moderately beneficial effect of music listening on pain release was reported. The quality of the included studies was low, mostly due to performance bias and detection bias. The results from this review are summarized in Table 2.

Psychoeducation and therapeutic communication

Koechlin (2021) performed a systematic review and network meta-analysis of RCTs to estimate the efficacy of nonpharmacological interventions, compared with waitlist control in patients <18 years with episodic migraine. The review reported short-term and long-term efficacy, based on a lumping and splitting approach. Outcomes were number of headache days per month, number of migraine days per month, frequency of headache attacks, frequency of migraine attacks, and headache index and activity. In general, beneficial effects were reported of self-administered treatments, biofeedback, relaxation, and psychological treatments on short-term and long-term using the lumping approach. No effects were found using the splitting approach. The evidence was of low quality, mostly due to within-study bias, imprecision, and incoherence. The results from this review are summarized in Tables 1 and 3.

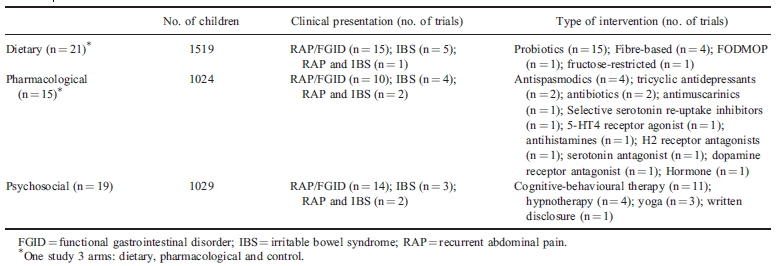

Abbott (2017) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs to estimate the effect of psychosocial interventions, compared with usual care or waitlist control in children aged 5 to 18 years with recurrent abdominal pain. The review included 18 studies of which 14 were included in the meta-analysis. Interventions consisted of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), hypnotherapy (including guided imagery), yoga, and written self-disclosure. Reported outcomes were pain intensity, pain duration, social or psychological functioning, quality of life, and functional impairment of daily activities. In general, beneficial effects in the short term on reducing pain with CBT and hypnotherapy were found. No effects were found on the other outcomes and on the use of yoga and written self-disclosure. The evidence was of very low to low quality due to the high risk of bias across the studies, such as unblinded participants and unblinded outcome assessment, along with some outcomes having a high level of unexplained heterogeneity (greater than 70%), wide confidence intervals, and a low number of participants included in the analyses. The results from this review are summarized in Tables 1, 3, and 4.

Gordon (2022) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs to estimate the effect of psychosocial interventions, compared with no intervention or other interventions in children aged 4 to 18 years with functional abdominal pain disorders. We only reported the results of the intervention compared to no intervention. The review included 33 studies, of which 26 were included in the meta-analysis and 17 studies used standard care, placebo, or waitlist control as comparison. Of these 33 studies, 18 were also included in Abbott (2017) and Abbott (2018). Interventions consisted of CBT, yoga, and hypnotherapy. Reported outcomes were pain frequency and pain intensity. In general, no effects were found for CBT, with moderate quality of evidence, and the evidence for yoga and hypnotherapy was of very low quality so no conclusions could be drawn. This was mostly caused by imprecision and high risk of bias. The results from this review are summarized in Tables 1, 3, and 4.

Abbott (2018) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs and randomized cross-over trials to estimate the effect of psychosocial intervention, compared with placebo, waiting list, no treatment, active control, or standard care in children aged 5 to 18 years with abdominal pain-related function gastrointestinal disorder. This review is a summary of three reviews, including the review of Abbott et al. (2017). Therefore, the same studies are included in this review as in the review of Abbott et al. (2017). This review updated the search and found two additional studies (Bonnert et al., 2017 and Korterink et al., 2016). Additionally, 16 studies included in Gordon et al., 2022 are also included in this review. Only the results not described in Abbott et al. (2017) are reported here. The review included 3 additional studies, next to the three reviews. Interventions consisted of CBT and hypnotherapy and reported outcomes were pain intensity postintervention, pain intensity after 3 to 6 months follow-up and pain intensity after 12 months or more follow-up. In general, beneficial effects of CBT and hypnotherapy were found on pain-intensity, with low quality of evidence due to lack of blinding. The results from this review are summarised in Tables 1 and 3.

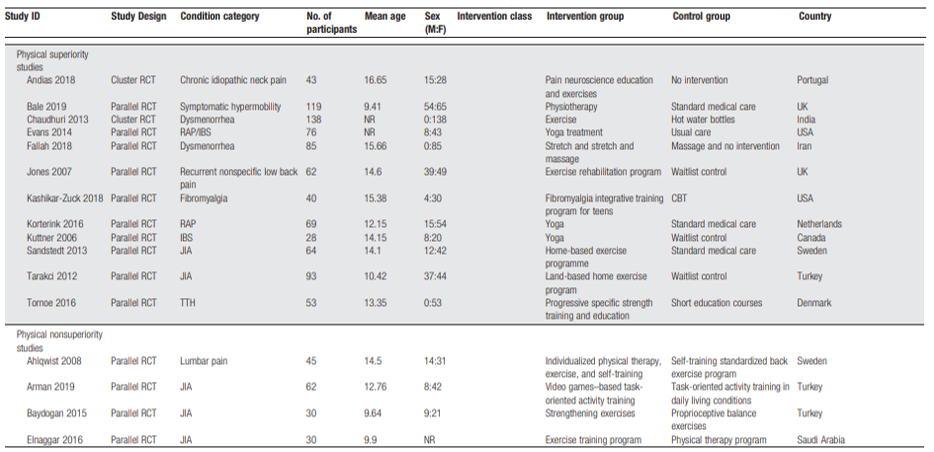

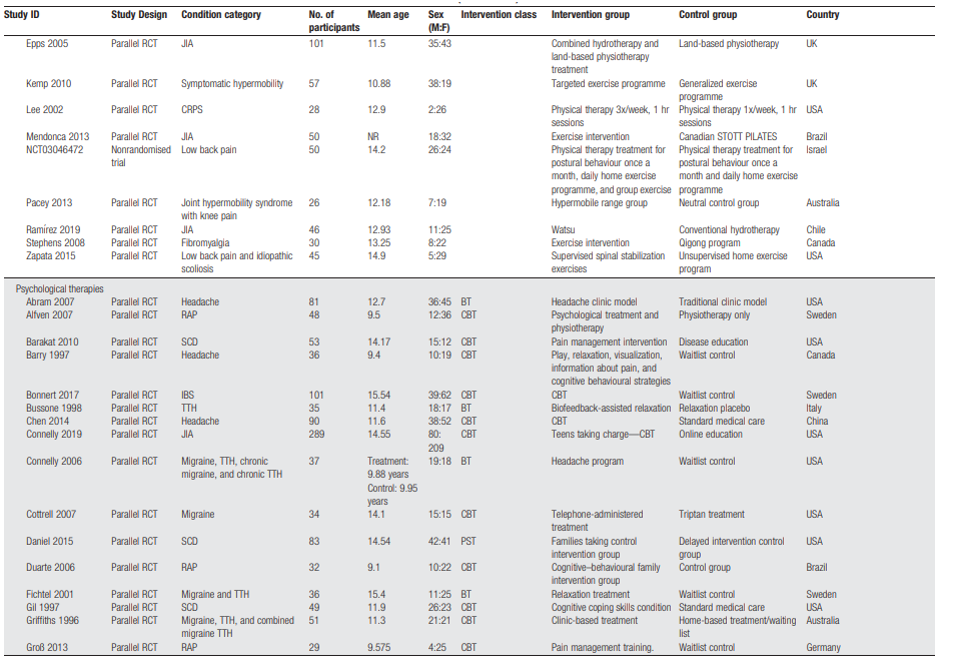

Physical and psychological interventions

The systematic review and meta-analysis (Fisher, 2022) for the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on the management of chronic pain in children from 2020, was included for the psychological therapy and physical therapy interventions.

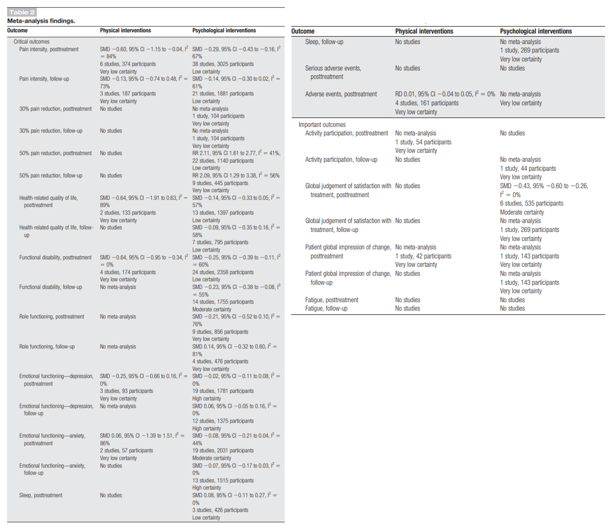

Fisher (2022) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on efficacy and safety of pharmacological, physical, and psychological intervention for the management of chronic pain in children. In our literature analysis, only the studies researching physical therapy and psychological therapy were included. They searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE and MEDLINE in Process, and EMBASE from inception to April 2020, for pharmacological and physical therapy trials. For psychological therapy trials, they updated searches using the same three databases, and PsycINFO from previous Cochrane reviews and they searched for trials in children with cancer from inception of each database to March 2020. For pharmacological and physical therapies, RCTs and nonrandomized comparative observational trials were included. For psychological trials, only RCTs were included. Inclusion criteria were studies of children (ages 0-19 years) with chronic pain, researching any analgesic drug, bodily movement therapies, and therapies delivering recognizable psychological content. The comparison could be active or placebo comparison, treatment as usual, waitlist control, or other pharmacological or physical therapy interventions. Interventions directed at parents of children with pain were also included. Exclusion criteria were passive physical interventions such as massage or manipulation and passive delivered psychological interventions (such as reading about CBT).

Critical outcomes were (reduction in) pain intensity, health-related quality of life (HRQOL), functional disability, role functioning, emotion functioning, sleep, and adverse events. Important outcomes were activity participation, global judgement of satisfaction with treatment, patient global impression of change, and fatigue. The authors used to Cochrane Risk of Bias tool to assess risk of bias in RCTs and the ROBINS-I tool for non-randomized studies and the level of evidence was assessed using GRADE. Overall, the authors included 34 pharmacological therapy trials (29 RCTs, 5 nonrandomised studies, and 37 reports) and 5 ongoing RCTs (no results), 24 physical therapy RCTs (33 reports) and 12 further ongoing trials (11 RCTs and 1 nonrandomised trial [which reported results]), and 63 psychological therapy RCTs and 16 ongoing RCT studies. No studies with data of children with cancer diagnosis, needing palliative care, or an intellectual disability were identified. The results from this review are summarised in Tables 4 and 5.

Results

The results of the reviews are summarized in Tables 1-5.

Authors’ conclusions

The review of See (2023) concluded that music interventions can improve pain and anxiety levels in children in the emergency department, but this evidence is of low quality. The high heterogeneity observed indicates insufficient evidence.

The review of Ting (2022) concluded that listening to music reliefs pain in both psychological and physiological domains. However, most included articles had high risk of performance bias and detection bias.

The review of Koechlin (2021) concluded that the network meta-analysis revealed different findings depending on the structure of the nodes in the network. Significant short- and long-term effects were found for most nonpharmacological interventions (ie, relaxation, biofeedback, psychological treatments, and self-administered psychological treatments) as well as for 1 control group (ie, psychological placebo) when compared with the waiting list. In terms of the second aim (ie, to systematically compare the different nonpharmacological treatment options relative to each other), the included interventions did not significantly differ from one another. In a second step, they split the various published interventions into individual nodes. Here, in the short- and long-term analyses, none of the included interventions were significantly more effective than the waiting list, which was the control group that most interventions were compared with and that connected 2 otherwise unconnected networks. Also, none of the interventions differed significantly from each other in the head-to-head comparisons. However, the quality of the evidence was low.

The review of Abbott (2017) concluded that they provided low‐quality evidence that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and hypnotherapy may be effective in reducing pain in the short term for children and adolescents presenting with recurrent abdominal pain (RAP). Sustained effects of both CBT and hypnotherapy on pain have also been reported, but the evidence to date is limited. There was little evidence that CBT or hypnotherapy affected school functioning, psychological well‐being, or quality of life. The review found no evidence to support the use of yoga or written self‐disclosure for the treatment of recurrent abdominal pain in children and adolescents.

The review of Gordon (2022) concluded that CBT and hypnotherapy should be considered as a treatment for functional abdominal pain disorders in childhood, with moderate quality. No conclusions could be drawn about the effect of yoga due to very low quality evidence.

The review of Abbott (2018) concluded that low-quality evidence was found to suggest that CBT and hypnotherapy may be effective in treating recurrent abdominal pain, with both reported to be effective in reducing pain in the short term. Sustained effects of CBT and hypnotherapy were also reported but the evidence is limited. We found insufficient evidence to support the use of yoga therapy or written self-disclosure.

The review of Fisher (2022) concluded that each modality of intervention separately showed some benefits of reducing pain intensity posttreatment, but these effects were not maintained at follow-up. Some physical and psychological interventions also reduced functional disability posttreatment, and effects were maintained for psychological interventions at follow-up. Physical therapies presented very little data that could be analysed for other outcomes, meaning any absence of effects and beneficial effects should be interpreted with caution. Most data were available for psychological therapies; however, we found no beneficial effects for improving HRQOL, emotional functioning, role functioning, or sleep in the meta-analyses. A beneficial effect of psychological interventions was found for global satisfaction with treatment. Adverse events were poorly reported, particularly in physical and psychological trials.

Table 1. Summary of findings table for the intervention ‘psychoeducation’

|

Outcome |

Time |

Type of intervention |

Author (year) |

N studies in meta-analysis |

Effect measure (95%CI) |

Figure for meta-analysis (see appendix) |

Certainty |

|

Efficacy |

|||||||

|

Efficacy* |

Short-term |

Self-administered psychological treatments |

Koechlin (2021) |

12 |

SMD 1.44 (95%CI -0.26 to 2.26) |

Figure 1A |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

Biofeedback |

Koechlin (2021) |

12 |

SMD 1.41 (95%CI -0.64 to 2.17) |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|||

|

Psychological treatments |

Koechlin (2021) |

12 |

SMD 1.36 (95%CI -0.15 to 2.57) |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|||

|

Efficacy* |

Long term |

Self-administered psychological treatments |

Koechlin (2021) |

12 |

SMD 1.40 (95%CI -0.28 to 2.52) |

Figure 1B |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

Biofeedback |

Koechlin (2021) |

12 |

SMD 1.21 (95%CI -0.47 to 1.94) |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|||

|

Psychological treatments |

Koechlin (2021) |

12 |

SMD 1.33 (95%CI -0.18 to 2.47) |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|||

|

Pain |

|||||||

|

Pain intensity |

Post intervention |

Cognitive behaviour therapy |

Abbott (2017) |

7 |

SMD -0.33 (95%CI -0.74 to 0.08) |

Figure 2 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

Cognitive behaviour therapy |

Abbott (2018) |

4 |

OR 5.67 (95%CI 1.18 to 27.32), NNTB=4 |

Figure 3 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

||

|

After 3-6 months follow-up |

Cognitive behaviour therapy |

Abbott (2018) |

3 |

OR 3.08 (95%CI 0.93 to 10.16), NNTB=5 |

Not provided |

|

|

|

After 3-12 months follow-up |

Cognitive behaviour therapy |

Abbott (2017) |

4 |

SMD -0.32 (95%CI -0.85 to 0.20) |

Figure 4 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

|

After ≥12 months follow-up |

Cognitive behaviour therapy |

Abbott (2017) |

3 |

SMD -0.04 (95%CI -0.39 to 0.31) |

Figure 5 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

|

Cognitive behaviour therapy |

Abbott (2018) |

2 |

OR 1.29 (95%CI 0.50 to 3.33) |

Not provided |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

||

|

|

Cognitive behaviour therapy |

Gordon (2022) |

6 |

SMD -0.58 (95%CI -0.83 to -0.32) |

Figure 6 |

ꚛꚛꚛ○ moderate |

|

|

Pain duration |

|

Cognitive behaviour therapy |

Abbott (2017) |

1 |

No difference |

NA |

|

|

Pain frequency |

|

Cognitive behaviour therapy |

Gordon (2022) |

7 |

SMD -0.36 (95%CI -0.63 to -0.09) |

Figure 7 |

ꚛꚛꚛ○ moderate |

|

Functioning |

|||||||

|

Social or psychological functioning |

|

Cognitive behaviour therapy |

Abbott (2017) |

3 |

No difference |

Not performed |

|

|

Functional impairment of daily activities |

|

Cognitive behaviour therapy |

Abbott (2017) |

4 |

SMD -0.57 (95%CI ‐1.34 to 0.19) |

Figure 8 |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

Quality of life |

|||||||

|

Physical quality of life |

|

Cognitive behaviour therapy |

Abbott (2017) |

3 |

SMD 0.71 (95%CI ‐0.25 to 1.66) |

Figure 9 |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

Psychosocial quality of life |

|

Cognitive behaviour therapy |

Abbott (2017) |

3 |

SMD 0.43 (95%CI ‐0.21 to 1.06) |

Figure 10 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

* Lumping approach

Green represents in favour of the intervention. Red represents in favour of the control. Yellow represents no significant difference between intervention and control. Grey represents no conclusions could be drawn.

SMD: standardized mean difference, 95%CI: 95% confidence interval, RR: risk ratio, OR: odds ratio, HRQoL: health-related quality of life, IG: intervention group, CG: control group, NNTB: number needed to benefit

Table 2. Summary of findings table for the intervention ‘distraction techniques’

|

Outcome |

Time |

Type of intervention |

Author (year) |

N studies in meta-analysis |

Effect measure (95%CI) |

Figure for meta-analysis (see appendix) |

Certainty |

|

Pain |

|||||||

|

Pain |

|

Music listening |

See (2023) |

2 |

SMD -0.40 (95%CI -0.78 to -0.03) |

Figure 11 |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

Pain release |

Post-operative |

Listening to music |

Ting (2022) |

8 |

SMD -0.49 (95%CI -0.90 to -0.08) |

Not provided |

|

|

Anxiety |

|||||||

Green represents in favour of the intervention. Red represents in favour of the control. Yellow represents no significant difference between intervention and control. Grey represents no conclusions could be drawn.

SMD: standardized mean difference, 95%CI: 95% confidence interval, RR: risk ratio, OR: odds ratio, HRQoL: health-related quality of life, IG: intervention group, CG: control group

Table 3. Summary of findings table for the intervention ‘physical interventions’

|

Outcome |

Time |

Type of intervention |

Author (year) |

N studies in meta-analysis |

Effect measure (95%CI) |

Figure for meta-analysis (see appendix) |

Certainty |

|

Pain |

|||||||

|

Pain intensity |

Post treatment |

Physical therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

6 |

SMD -0.60 (95%CI -1.15 to -0.04) |

Figure 17 |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

Yoga |

Abbott (2017) |

3 |

SMD -0.31 (95%CI -0.67 to 0.05 |

Figure 18 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

||

|

At follow-up |

Physical therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

3 |

SMD -0.13 (95%CI -0.74 to 0.48) |

Figure 19 |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

|

Yoga |

Abbott (2017) |

1 |

No difference |

NA |

|

||

|

|

Yoga |

Gordon (2022) |

1 |

No conclusions could be drawn |

NA |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

|

Pain frequency |

|

Yoga |

Abbott (2017) |

1 |

No difference postintervention, at 6, and at 12 months follow-up |

NA |

|

|

|

Yoga |

Gordon (2022) |

1 |

No conclusions could be drawn |

NA |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

|

Anxiety |

|||||||

|

Anxiety post-treatment |

|

Physical therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

2 |

SMD 0.06 (95%CI -1.39 to 1.51) |

Figure 20 |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

Functioning |

|||||||

|

Social or psychological function |

|

Yoga |

Abbott (2017) |

3 |

No difference |

Not performed |

|

|

Functional disability |

Post intervention |

Yoga |

Abbott (2017) |

2 |

SMD -0.32 (95%CI -1.07 to 0.43) |

Figure 21 |

|

|

Physical therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

4 |

SMD -0.64 (95%CI -0.95 to -0.34) |

Figure 22 |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

||

|

At follow-up |

Physical therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

1 |

SMD -0.36 (95%CI -1.04 to 0.28) |

Figure 23 |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

|

Quality of life |

|||||||

|

HRQoL post-treatment |

|

Physical therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

2 |

SMD -0.64 (95%CI -1.91 to 0.63) |

|

ꚛ○○○ very low |

Green represents in favour of the intervention. Red represents in favour of the control. Yellow represents no significant difference between intervention and control. Grey represents no conclusions could be drawn.

SMD: standardized mean difference, 95%CI: 95% confidence interval, RR: risk ratio, OR: odds ratio, HRQoL: health-related quality of life, IG: intervention group, CG: control group

Table 4. Summary of findings table for the intervention ‘psychological interventions’

|

Outcome |

Time |

Type of intervention |

Author (year) |

N studies in meta-analysis |

Effect measure (95%CI) |

Figure for meta-analysis (see appendix) |

Certainty |

|

Pain |

|||||||

|

Pain intensity |

Post-treatment |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

38 |

SMD -0.29 (95%CI -0.43 to -0.16) |

Figure 24 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

At follow-up |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

21 |

SMD of -0.14 (95%CI -0.30 to 0.02) |

Figure 25 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

|

Pain intensity

|

Post intervention |

Hypnotherapy |

Abbott (2017) |

4 |

SMD -1.01 (95%CI -1.41 to -0.61) |

Figure 14 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

|

Hypnotherapy |

Abbott (2018) |

4 |

OR 6.78 (95%CI 2.41 to 19.07), NNTB = 3 |

Figure 15 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

|

|

After 5 years follow-up |

Hypnotherapy |

Abbott (2017) |

1 |

IG mean 2.9 ± SD 4.4 vs CG mean 7.7 ± SD 5.3 |

NA |

|

|

|

Hypnotherapy |

Gordon (2022) |

1 |

No conclusions could be drawn |

NA |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

|

30% pain reduction |

Post-treatment |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

1 |

RR 1.13 (95%CI 0.64 to 2.02) |

NA |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

At follow-up |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

1 |

RR 1.07 (95%CI 0.77 to 1.49) |

NA |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

|

50% pain reduction

|

Post-treatment |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

22 |

RR 2.11 (95%CI 1.61 to 2.77) |

Figure 26 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

At follow-up |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

9 |

RR 2.09 (95%CI 1.29 to 3.38) |

Figure 27 |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

|

Pain frequency |

Post-intervention |

Hypnotherapy |

Abbott (2017) |

1 |

SMD -1.28 (95%CI -1.84 to -0.72) |

Figure 16 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

|

After 5 years follow-up |

Hypnotherapy |

Gordon (2022) |

1 |

No conclusions could be drawn |

NA |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

|

|

Hypnotherapy |

Abbott (2017) |

1 |

IG mean 2.3 ± SD 4.0 vs CG mean 7.1 ± SD 6.0 |

NA |

|

|

Pain duration |

|

Hypnotherapy |

Abbott (2017) |

1 |

IG mean 1.20 ± SD 1.47 vs CG mean 3.50 ± SD 2.53 |

NA |

|

|

Anxiety |

|||||||

|

Anxiety

|

Post-treatment |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

19 |

SMD -0.08 (95%CI -0.21 to 0.04) |

Figure 28 |

ꚛꚛꚛ○ moderate |

|

At follow-up |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

13 |

SMD -0.07 (95%CI -0.17 to 0.03) |

Figure 29 |

ꚛꚛꚛꚛ high |

|

|

Functioning |

|||||||

|

School absence

|

Post-treatment |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

9 |

SMD -0.21 (95%CI -0.52 to 0.10) |

Figure 30 |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

At follow-up |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

4 |

SMD 0.14 (95%CI -0.32 to 0.60) |

Figure 31 |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

|

Activity participation |

At follow-up |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

1 |

SMD -0.99 (95%CI -1.62 to -0.36) |

NA |

ꚛ○○○ very low |

|

Functional disability |

Post-treatment |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

24 |

SMD -0.25 (95%CI -0.39 to -0.11) |

Figure 32 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

At follow-up |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

14 |

SMD -0.23 (95%CI -0.38 to -0.08) |

Figure 33 |

ꚛꚛꚛ○ moderate |

|

|

Quality of life |

|||||||

|

HRQoL |

Post-treatment |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

13 |

SMD -0.14 (95%CI -0.33 to 0.05) |

Figure 34 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

At follow-up |

Psychological therapy |

Fisher (2022) |

7 |

SMD -0.09 (95%CI -0.35 to 0.16) |

Figure 35 |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

|

|

Hypnotherapy |

Abbott (2017) |

3 |

Inconclusive results, one study found a beneficial effect and two studies found no effect |

Not performed |

|

|

Green represents in favour of the intervention. Red represents in favour of the control. Yellow represents no significant difference between intervention and control. Grey represents no conclusions could be drawn.

SMD: standardized mean difference, 95%CI: 95% confidence interval, RR: risk ratio, OR: odds ratio, HRQoL: health-related quality of life, IG: intervention group, CG: control group

Table 5. Summary of findings table for ‘other non-farmacological interventions’

|

Outcome |

Time |

Type of intervention |

Author (year) |

N studies in meta-analysis |

Effect measure (95%CI) |

Figure for meta-analysis (see appendix) |

Certainty |

|

Efficacy |

|||||||

|

Efficacy |

Short-term |

Relaxation* |

Koechlin (2021) |

12 |

SMD 1.38 (95%CI 0.61 to 2.14) |

Figure 1A |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

Relaxation stress management, relaxation education, biofeedback stress management, biofeedback relaxation education, transcendental meditation, autogenic feedback, autogenic training, progressive muscle relaxation, education, and hypnotherapy** |

Koechlin (2021) |

12 |

No differences with waiting list control |

Figure 13C |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

||

|

Efficacy |

Long-term |

Relaxation* |

Koechlin (2021) |

12 |

SMD 1.35 (95%CI 0.60 to 2.09) |

Figure 2A |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

|

Relaxation stress management, relaxation education, biofeedback stress management, biofeedback relaxation education, transcendental meditation, autogenic feedback, autogenic training, progressive muscle relaxation, education, and hypnotherapy** |

Koechlin (2021) |

12 |

No differences with waiting list control |

Figure 13D |

ꚛꚛ○○ low |

||

|

Pain |

|||||||

|

Pain frequency |

Post-intervention |

Written self-disclosure |

Abbott (2017) |

1 |

No difference |

NA |

|

|

After 3 months follow-up |

Written self-disclosure |

Abbott (2017) |

1 |

No difference |

NA |

|

|

|

After 6 months follow-up |

Written self-disclosure |

Abbott (2017) |

1 |

IG mean 1.35 ± SD 1.39 vs CG mean 2.32 ± SD 1.72 |

NA |

|

|

*Lumping approach

**Splitting approach

Green represents in favour of the intervention. Red represents in favour of the control. Yellow represents no significant difference between intervention and control. Grey represents no conclusions could be drawn.

SMD: standardized mean difference, 95%CI: 95% confidence interval, RR: risk ratio, OR: odds ratio, HRQoL: health-related quality of life, IG: intervention group, CG: control group

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence of the literature is determined per intervention, per outcome.

Psychoeducation

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure efficacy was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and applicability (bias due to indirectness) to LOW.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and conflicting results (inconsistency) to LOW.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure functioning was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and number of included patients (imprecision) to LOW.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and number of included patients (imprecision) to LOW.

Distraction techniques

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias), conflicting results (inconsistency), and number of included patients (imprecision) to VERY LOW.

Physical interventions

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias), conflicting results (inconsistency), and number of included patients (imprecision) to VERY LOW.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anxiety was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias), conflicting results (inconsistency), and number of included patients (imprecision) to VERY LOW.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure functioning was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias), conflicting results (inconsistency), and number of included patients (imprecision) to VERY LOW.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias), conflicting results (inconsistency), applicability (bias due to indirectness), and number of included patients (imprecision) to VERY LOW.

Psychological interventions

The level of evidencefor psychological therapy regarding the outcome measure pain was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and number of included patients (imprecision) to LOW.

The level of evidence for written self-disclosure regarding the outcome measure pain was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias), conflicting results (inconsistency), and number of included patients (imprecision) to VERY LOW.

The level of evidence for hypnotherapy regarding the outcome measure pain was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias), conflicting results (inconsistency), and number of included patients (imprecision) to VERY LOW.

The level of evidence for psychological therapy regarding the outcome measure anxiety was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias) to MODERATE.

The level of evidence for psychological therapy regarding the outcome measure functioning was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and conflicting results (inconsistency) to VERY LOW.

The level of evidence for psychological therapy regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and conflicting results (inconsistency) to LOW.

The level of evidence for hypnotherapy regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias), conflicting results (inconsistency), and number of included patients (imprecision) to VERY LOW.

Other non-farmacological interventions

The level of evidence for relaxation therapy regarding the outcome measure efficacy was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and applicability (bias due to indirectness) to LOW.

The level of evidence for written self-disclosure regarding the outcome measure pain was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias), conflicting results (inconsistency), and number of included patients (imprecision) to VERY LOW.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What are the (un)favourable effects of non-pharmacological pain management compared to treatment without non-pharmacological pain management in the treatment of children with acute and chronic pain?

| P: |

1: preverbal children/neonates (<1 month) 2: verbal children 3: adolescents (<18 years) 4: children with neurobiological development disorders |

| I: |

1: psycho-education 2: distraction techniques (child care worker/pedagogical employee, clown, virtual reality, massage, sway, music therapy, physiological comfort techniques) 3: physiotherapeutic/physical interventions 4: psychological(behavioral therapy, hypnotherapy) 5: other non-farmacological interventions |

| C: | Pharmacological pain management or no pain management |

| O: | Crucial: prevention of pain, reduction of pain, anxiety, stress/distress, psychosocial functioning, (health-related) quality of life; Important: length of (hospital) stay, costs |

Relevant outcome measures

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined one point difference on the VAS scale (Voepel-Lewis et al., 2011), or 10% difference on a pain scale as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for pain prevention and reduction.

For dichotomic outcome measures, the working group used the GRADE default limits as limits for clinical decision making, which are defined as a risk ratio (RR) of >1.25 and <0.8 as clinically relevant.

For the meta-analysis, the working group defined a difference of 0.5 standard deviation (SD) as clinically relevant. When standardized mean difference (SMD) was used, 0.2 represented a small effect size, 0.5 a medium effect size and 0.8 a large effect size, based on Cohen, 1988.

Search and select (Methods)

We performed a systematic search for the PICO. The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until September 29, 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: non-pharmacological treatment, pain, and children. The systematic literature search resulted in 3137 hits. Due to the high amount of hits, we decided to only screen the 697 systematic reviews.

Guideline working group members proposed an extensive World Health Organization (WHO) review and guideline about physiotherapeutic/physical (I4) and psychological (I5) interventions. We decided to use this systematic review (Fisher et al., 2022) for the literature summary of these two interventions. Therefore, we did not perform Title/Abstract selection in physiotherapeutic/physical and psychological interventions.

697 systematic reviews were screened on title and abstract for the interventions psycho-education (I1), distraction techniques (I2), and therapeutic communication (I3) by one working group member for the first selection, of which the 148 included articles were screened on title and abstract by an advisor and 48 were selected for full text reading. Parallel, another advisor screened the 697 systematic reviews using the artificial intelligence tool ASReview and included 122 articles based on title and abstract. Of these, 48 articles were not included by the manual title and abstract screening of the working group members. 15 additional articles were included based on title and abstract screening using ASReview. After reading the full text, 525 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and in total 7 studies, based on both the manual and ASReview screening, were included.

The working group decided to screen on title and abstract of the observational studies and RCTs on nonpharmacological treatments for preverbal children and neonates, because no systematic reviews were found for this subgroup. Screening was performed by an advisor using ASReview. One possibly suitable article provided by a working group member was used as prior knowledge. However, after screening, this article was researching pain in procedures and therefore excluded. Screening was stopped after 50 consecutive irrelevant records. No additional articles were included using ASReview screening.

Articles about procedures were excluded because these are part of the PSA guideline. A procedure was defined as: ‘an activity directed at or performed on an individual with the object of improving health, treating disease or injury, or making a diagnosis’. It is a course of action intended to achieve a result in the delivery of healthcare, which can be to diagnose, measure, monitor, or treat problems such as diseases or injuries. These are carried out by a healthcare professional. Procedures can be surgical, anaesthesia, propaedeutic, diagnostic, therapeutic, rehabilitative, screening, and cosmetic (Landau, 1986).

Results

For the interventions psychoeducation, distraction techniques, and therapeutic communication, 6 studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

For the physical and psychological interventions, we did not include any studies in addition to the WHO review of Fisher et al., 2022. We adapted the evidence tables and risk of bias tables of the WHO review.

Referenties

- 1 - Abbott RA, Martin AE, Newlove-Delgado TV, Bethel A, Thompson-Coon J, Whear R, Logan S. Psychosocial interventions for recurrent abdominal pain in childhood. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 10;1(1):CD010971. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010971.pub2. PMID: 28072460; PMCID: PMC6464036.

- 2 - Abbott RA, Martin AE, Newlove-Delgado TV, Bethel A, Whear RS, Thompson Coon J, Logan S. Recurrent Abdominal Pain in Children: Summary Evidence From 3 Systematic Reviews of Treatment Effectiveness. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018 Jul;67(1):23-33. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001922. PMID: 29470291.

- 3 - Fisher E, Villanueva G, Henschke N, Nevitt SJ, Zempsky W, Probyn K, Buckley B, Cooper TE, Sethna N, Eccleston C. Efficacy and safety of pharmacological, physical, and psychological interventions for the management of chronic pain in children: a WHO systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2022 Jan 1;163(1):e1-e19. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002297. Erratum in: Pain. 2023 Feb 1;164(2):e121. PMID: 33883536.

- 4 - Gordon M, Sinopoulou V, Tabbers M, Rexwinkel R, de Bruijn C, Dovey T, Gasparetto M, Vanker H, Benninga M. Psychosocial Interventions for the Treatment of Functional Abdominal Pain Disorders in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2022 Jun 1;176(6):560-568. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0313. PMID: 35404394; PMCID: PMC9002716.

- 5 - Koechlin H, Kossowsky J, Lam TL, Barthel J, Gaab J, Berde CB, Schwarzer G, Linde K, Meissner K, Locher C. Nonpharmacological Interventions for Pediatric Migraine: A Network Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2021 Apr;147(4):e20194107. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-4107. Epub 2021 Mar 9. PMID: 33688031.

- 6 - Landau S. International Dictionary of Medicine and Biology. Page 2297. ISBN 0-471-01849-X.

- 7 - See C, Ng M, Ignacio J. Effectiveness of music interventions in reducing pain and anxiety of patients in pediatric and adult emergency departments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Emerg Nurs. 2023 Jan;66:101231. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2022.101231. Epub 2022 Dec 16. PMID: 36528945.

- 8 - Ting B, Tsai CL, Hsu WT, Shen ML, Tseng PT, Chen DT, Su KP, Jingling L. Music Intervention for Pain Control in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2022 Feb 14;11(4):991. doi: 10.3390/jcm11040991. PMID: 35207263; PMCID: PMC8877634.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

|

|||

|

See, 2023

Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs, quasi-experimental studies, cohort studies, case-control studies, and pilot studies.

Literature search between 2011 and 2021.

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interest. Funding not reported.

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

11 studies included, of which 9 studies and 2 reported of included studies. Three studies focused on the paediatric population (aged ≤21 years) (Hartling ea 2013; Park ea 2016; van der Heijden ea 2019)

Country and setting: 5 studies were conducted in the United States, 2 in Turkey, and one each from Australia, Canada, France, and South Africa |

Of the studies in paediatric patients, music interventions consisted of:

|

Standard care, or cartoon and standard care. |

Follow-up not reported.

|

Pain* Pooled effect (random effect model): SMD -0.40 (95%CI -0.78 to -0.03) favouring the intervention. Heterogeneity (I2): 81%. n=2

The quality of evidence was GRADE Very low, due to the lack of blinding for RCTs (risk of bias), inconsistency (high heterogeneity), indirectness (variations in population age and music interventions), and imprecision (small sample sized with wide CIs).

|

Intervention subgroup Distraction techniques

Risk of Bias Risk of Bias assessment not provided. Authors state that due to the nature of music interventions, the quality criteria of RCTs for blinding participants, providers and outcome assessors were poorly scored.

Authors conclusion This systematic review and meta-analysis present findings that contribute to the evidence supporting the effectiveness of music interventions in improving pain and anxiety levels in paediatrics and adults in the EDs.

See fiure 2 for evidence table of the included studies in the review.

*Only the results in paediatric patients are reported. |

|

|

|||

|

Fisher, 2022*

Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs and nonrandomised comparative observational trials (latter only for physical therapies)

Literature search between inception and March 2020.

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: E. Fisher, G. Villanueva, N. Henschke, K Probyn, B. Buckley, and C. Eccleston report funding from the World Health Organisation during the conduct of the study. W. Zempsky is a consultant for GSK, GlycoMimetics, and the Institute for Advanced Clinical Trials for Children. He receives funding form the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Defence. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare |

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

24 studies in physical therapy were included, of which 33 reported of RCTs and 12 further ongoing trials (11 RCTs and 1 nonrandomised trial (of which 1 reported results)). 18 studies were included in the quantitative synthesis. 63 studies in psychological therapy were included, of which 81 reports of RCTs and 16 ongoing RCT studies.56 studies were included in the quantitative synthesis.

Country and setting: Of the 25 trials that had results, 4 studies each were conducted in the United Kingdom and the United States, 3 in Turkey, 2 each in Canada and Sweden, and one each in Australia, Brazil, Chile, Denmark, India, Iran, Israel, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Saudi Arabia. We found 34 studies conducted in North America, 11 in Sweden, 6 in the Netherlands, 6 in Germany, 2 in Australia, and one inBrazil, Spain, Italy, and China each. |

Physical trials Physical intervention

Psychological trials We found 43 arms of CBT, 15 arms of relaxation, 7 arms of behavioural therapy, 3 arms of hypnosis, 2 arms of problem-solving therapy, and one arm of acceptance commitment therapy. |

Physical trials Nonphysical intervention control, standard care, or waitlist control.

Psychological trials We found 36 active control arms, 16 standard or usual care arms, and 17 waitlist control arms (note, because some studies included multiple arms, these numbers will not add up to 63). |

Follow-up not reported.

|

Random effect models were used for all meta-analysis.

For the outcomes, see figure 4.

|

Intervention subgroup Physical and psychological interventions

Risk of Bias Risk of Bias assessment of physical intervention provided by Fisher 2022:

Risk of Bias assessment of psychological intervention provided by Fisher 2022:

Authors conclusion We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the efficacy and safety of pharmacological, physical, and psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain in youth, used to support the World Health Organisation guidelines on the management of chronic pain in children.40 We found each modality of intervention separately showed some benefits of reducing pain intensity posttreatment, but these effects were not maintained at follow-up. Some physical and psychological interventions also reduced functional disability posttreatment, and effects were maintained for psychological interventions at follow-up. Pharmacological and physical therapies presented very little data that could be analysed for other outcomes, meaning any absence of effects and beneficial effects should be interpreted with caution. Most data were available for psychological therapies; however, we found no beneficial effects for improving HRQOL, emotional functioning, role functioning, or sleep in the meta-analyses. A beneficial effect of psychological interventions was found for global satisfaction with treatment. Adverse events were poorly reported, particularly in physical and psychological trials. See figure 3 for evidence table of the included studies in the review.

*Data on pharmacological interventions not reported. |

|

|

|||

|

Ting, 2022

Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs, quasi-experimental studies, cohort studies, case-control studies, and pilot studies.

Literature search from inception to January 2022

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors of this work were supported by the following grants: MOST108-2410-H-039-003, 109-2320-B-038-057-MY3, 109-2320-B-039-066, 110-2321-B-006-004, 110-2811-B-039-507, 110-2320-B-039-048-MY2, and 110-2320-B-039-047-MY3 from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan; ANHRF109-31, 110-13, and 110-26 from An Nan Hospital, China Medical University, Tainan, Taiwan; CMRC-CMA-2 from Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE), Taiwan; CMU108-SR-106 from the China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan; and CMU104-S-16-01, CMU103-BC-4-1, CRS-108-048, DMR-102-076, DMR-103-084, DMR-106-225, DMR-107-204, DMR-108-216, DMR-109-102, DMR-109-244, DMR-HHC-109-11, DMR-HHC-109-12, DMR-HHC-110-10, DMR-110-124, and CMU110-AWARD-02 from the China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan |

Inclusion criteria SR: (1) randomized controlled trials; (2) intervention group receiving music intervention that included all three factors of music (i.e., rhythm, melody, and harmony); (3) outcome assessments included pain measures; (4) age of all participants was less than 18 years.

Exclusion criteria SR: (1) reviews, protocols, conference papers, case reports, letters, or editorials; (2) MI was administered with other types of therapy or was a part of complementary and alternative therapy; (3) the control group received any components of music, i.e., rhythm, melody, and harmony; (4) studies that did not provide information for meta-analysis.

38 studies included, which were all included in the meat-analysis.

Country and setting: Eight rticles were conducted in America, 14 in Europe, 13 in Asia, and three in Africa. 29 studies were conducted in the hospital setting and 9 in the clinic setting.

Two articles included adolescents, 12 newborns, and 24 infants and children.

8 articles included patients with postoperative pain. |

Listening to music. Among all 38 studies, the participants listened to classical music in 11 articles, to kids’ music in 8 articles, to world music in 3 articles, to pop music in 3 articles, to special composition in 5 articles, and to multiple combinations of music in 4 articles. Additionally, in one article, two groups of participants listened to either kids’ music or world music, and thus this article was separated into two datasets. As for the listening instruments, 9 articles used headphones, 4 used earphones, 19 used speakers, and 4 used live performance. In one article, participants listened to music using either headphones or speakers, and thus this study was separated into two datasets. |

Music control (not further described, but the control group does not receive any components of music) |

Follow-up not reported.

|

Pain release* Pooled effect (random effect model): SMD -0.49 (95%CI -0.90 to -0.08, p=0.018) favouring the intervention. Heterogeneity (I2): 81%. n=8

|

Intervention subgroup Distraction techniques

Risk of Bias Risk of Bias assessment provided by Ting et al., 2022:

Authors conclusion Our meta-analysis of 38 RCT articles with a total of 5601 participants provides evidence supporting the thesis that MI releases pain in both psychological and physiological domains. A consistent music style and a pure auditory experience might be important in MI for pain. MI is an appropriate, low-stress, and safe non-pharmacological treatment for clinical pain relief in the paediatric population.

No evidence table provided.

*Only the results of patients with postoperative pain are reported. |

|

|

|||

|

Koechlin, 2021 |

SR and network meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search from inception to August 5, 2019

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Dr Koechlin is sponsored by the Swiss National Science Foundation fellowship P400PS_186658. Dr Locher received funding for this project from the Swiss National Science Foundation: P400PS_180730. Dr Meissner received support from the Schweizer-Arau-Foundation and the Theophrastus Foundation, Germany. This work was supported in part by the Sara Page Mayo Endowment for Pediatric Pain Research, Education, and Treatment. |

Inclusion criteria SR: Nonpharmacological interventions for children and adolescents <18 years were included in this study. Participants had to have a diagnosis of episodic migraine (with or without aura) according to the International Headache Society (IHS) criteria, or criteria for migraine diagnosis had to be in close agreement with the IHS classification. Trials had to specifically state that they were focusing on paediatric migraine but were not required to specify the exact diagnosis of migraine to be included. Eligible trial designs included RCTs that make head-to-head comparisons of at least 2 nonpharmacological interventions as well as RCTs that compare at least 1 nonpharmacological intervention with a control group. To be included, trials had to report at least 1 migraine-related outcome. Crossover studies were only included if we were able to extract the results of the first period separately.

Exclusion criteria SR: Studies in which migraine was associated with other neurologic disorders as well as studies on menstrual migraine were excluded.

12 studies were included. 2 other studies were excluded because they did not connect with the other studies in the network.

Country and setting: Six (5%) of the included trials recruited children and adolescents from the United States, 3 (25%) from Europe, and 3 (25%) from Canada. |

Relaxation stress management, relaxation education, relaxation, biofeedback, biofeedback stress management, biofeedback relaxation education, transcendental meditation, autogenic feedback, autogenic training, psychological treatments, progressive muscle relaxation, self-administered psychological treatments, education, and hypnotherapy |

Psychological placebo, sham biofeedback, and waiting list |

Follow-up not reported.

|

Lumping approach* (interventions combined into one group) Short term efficacy Self-administered treatments (SMD: 1.44; 95% CI, 0.26 to 2.62), biofeedback (SMD: 1.41; 95% CI, 0.64 to 2.17), relaxation (SMD: 1.38; 95% CI, 0.61 to 2.14), psychological treatments (SMD: 1.36; 95% CI, 0.15 to 2.57), and psychological placebos (SMD: 1.17; 95% CI, 0.06 to 2.27) were significantly more effective than the waiting list.

Long-term efficacy Self-administered treatments (SMD: 1.40; 95% CI, 0.28 to 2.52), relaxation (SMD: 1.35; 95% CI, 0.60 to 2.09), psychological treatments (SMD: 1.33; 95% CI, 0.18 to 2.47), biofeedback (SMD: 1.21; 95% CI, 0.47 to 1.94), and psychological placebos (SMD: 1.14; 95% CI, 0.09 to 2.19) revealed significantly higher effects than the waiting list.

Splitting approach* (less heterogeneity because interventions are split into groups)

Short-term efficacy No nonpharmacological intervention was significantly more effective than the waiting list. There were no significant differences between the included nonpharmacological interventions.

Long-term efficacy No nonpharmacological intervention was significantly more effective than the waiting list. None of the included nonpharmacological interventions did differ significantly from one another.

*Outcomes were (1) number of headache days per month, (2) the number of migraine days per month, (3) frequency of headache attacks (means and SDs), (4) frequency of migraine attacks (means and SDs), or (5) headache index and activity. |

Intervention subgroup Psychoeducation, distraction techniques, therapeutic communication Quality assessment See https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Faap2.silverchair-cdn.com%2Faap2%2Fcontent_public%2Fjournal%2Fpediatrics%2F147%2F4%2F10.1542_peds.2019-4107%2F1%2Fpeds_20194107supplementarydata.doc%3FExpires%3D1705498669%26Signature%3DDntYW92gQkpbZfMHFqAbrI3Tbb7J~ozzJ3zZzG7y-WaxLcmNBZ4nRbDqkHuGDPhb~2GpB8zKUpGDavelrYWm59RAQxmq~djBTXQxBQUy2YsddVvvQ4Orfts1rNzexXYJ~ukZeRWs2LM9NpOFWJgTpLYpLssIfR2rIPspdnmXRGZSQY1M7DUQcog4acEk~F5aAXHAh0q8~3vc8oOR-UtsmVcSzeSOryjuNSw1A-uu3ve6UNrE2JTjPQ4xiorl6R5jFmDzhUA1~0HxaGWxqzfCDZRqq5JHWNYQ7Cqo95Ryw07MahN8FVDqoyIBJX7jWXR~HMuXlc7NY3ddyMhk7f8gqw__%26Key-Pair-Id%3DAPKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA&wdOrigin=BROWSELINKhttp GRADE assessments.

Authors conclusion Interestingly, our NMA revealed different findings depending on the structure of the nodes in the network. In a first step, we lumped the interventions into broader classes. Significant short- and long-term effects were found for most nonpharmacological interventions (ie, relaxation, biofeedback, psychological treatments, and self-administered psychological treatments) as well as for 1 control group (ie, psychological placebo) when compared with the waiting list. In terms of our second aim (ie, to systematically compare the different nonpharmacological treatment options relative to each other), the included interventions did not significantly differ from one another. In a second step, we split the various published interventions into individual nodes. Here, in the short- and long-term analyses, none of the included interventions were significantly more effective than the waiting list, which was the control group that most interventions were compared with and that connected 2 otherwise unconnected networks. Also, none of the interventions differed significantly from each other in the head-to-head comparisons.

See https://publications.aap.org/view-large/8236846https://punce table of the included studies in the review.

|

|

|

|||

|

Abbott, 2017 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to June 2016

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The work of the evidence synthesis team is funded by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South West Peninsula (PenCLAHRC). However, the funder had no role in the review itself. |

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR: Not reported

18 studies were included (from 26 reports). 2 studies (from 2 reports) awaiting classification and 14 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Country and setting: The majoity of studies recruited children through paediatric gastroenterology or paediatric pain clinics. Eight studies were conducted in the USA, three in the Netherlands, two in Germany, two in Australia, one in Canada, one in Brazil, and one recruiting from both the USA and Canada. |

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), hypnotherapy (including guided imagery), yoga, written self-disclosure. |

The comparator was usual medical care in six studies, a wait‐list control in eight studies, and an education or breathing control, or both, in four studies. However, meta-analysis are compared with usual care or wait-list control. |

Follow-up not reported.

|

CBT Pain intensity: postintervention Pooled effect (random effect model): SMD -0.33 (95%CI -0.74 to 0.08, p=0.12) favouring the intervention. Heterogeneity (I2): 70%. n=7. GRADE low.