Minimaal invasieve chirurgie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de rol van minimaal invasieve chirurgie bij patiënten met een oesofaguscarcinoom?

De uitgangsvraag omvat de volgende deelvragen:

- Wat is de rol van minimaal invasieve chirurgie (Robot, video-geassisteerde, conventionele minimaal invasieve chirurgie) versus open chirurgie bij patiënten met een oesofaguscarcinoom?

- Wat is de rol van hybride chirurgie (minimaal invasief gecombineerd met open) versus open chirurgie bij patiënten met een oesofaguscarcinoom?

Aanbeveling

Verricht een minimaal invasieve oesofagus resectie indien expertise hiervoor aanwezig is.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek gedaan naar de rol van minimaal invasieve chirurgie (MIC) als behandeling van patiënten met slokdarmkanker, waarbij nog specifiek onderscheid werd gemaakt voor volledig MIC en hybride MIC.

Er lijkt een effect te zijn in het voordeel van MIC op overall survival. Dit effect was waarneembaar één, drie en vijf jaar na de operatie, maar vanwege de imprecisie rond deze data, tezamen met een risico op bias, is de bewijskracht voor deze bevinding laag. Bij het beschouwen van de onderverdeling tussen volledig minimaal invasief en hybride benaderingen lijkt het verschil vooral te wijten aan het lagere aantal gebeurtenissen in de hybride benadering, maar er is onvoldoende data om hieruit een definitieve conclusie te trekken.

De complicaties zijn onderverdeeld in een drietal groepen: lekkage anastomose, cardiale complicaties en pulmonale complicaties. Er werd geen duidelijk klinisch relevant voordeel gevonden voor lekkage van de anastomose, behalve voor hybride versus open benadering. Bij de open benadering was er minder sprake van lekkage dan bij de hybride benadering.

Met betrekking tot de cardiale en pulmonale complicaties is er een klinisch relevant voordeel voor minimaal invasieve chirurgie, met uitzondering van de vergelijking tussen de hybride versus open benadering. Over de hele breedte genomen kan dus niet worden bepaald welke van de twee operatieve benaderingen tot minder complicaties leidt, omdat de bewijskracht voor deze bevindingen laag zijn.

Kwaliteit van leven werd in minder artikelen gerapporteerd en ook alleen maar in studies die volledig MIC hebben toegepast. In beide global health scores van de C30 vragenlijst, het fysiek functioneren van de C30 vragenlijst en de praten en pijn subdomeinen van de OES18 vragenlijst werd een klinisch relevant verschil in het voordeel van MIC gezien; de fysiek en mentale domeinen van de SF-36 vragenlijst lieten geen klinisch relevant verschil zien. Er lijkt een voordeel voor een (volledig) MIC te zijn op de kwaliteit van leven, maar de bewijskracht hiervan is laag. Er is niets bekend over hybride MIC en kwaliteit van leven.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor patiënten zou een minimaal invasieve benadering voordeel kunnen hebben, mits deze wordt uitgevoerd in een centrum met deze expertise. Patiënten hebben dan minder grote littekens, wat ook op de lange termijn voordelen kan hebben, aangezien er minder littekenbreuken voorkomen na minimaal invasieve chirurgie. Ook is het cosmetisch resultaat fraaier. Het chirurgisch trauma is kleiner, wat zou kunnen resulteren in een minder diepe dip in de immuunrespons na chirurgie.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Ondanks dat de primaire kosten voor minimaal invasieve chirurgie hoger zijn dan die voor open chirurgie, blijkt uit enkele studies dat de IC-opnameduur en ook de opnameduur korter zijn na minimaal invasieve chirurgie. Ook zijn pulmonale en cardiale complicaties minder, wat ook tot lagere kosten leidt. Dit kan de hogere procedure kosten weer opheffen (Lee, 2013).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De meeste Nederlandse centra voeren reeds minimaal invasieve oesophagusresecties uit, waarbij momenteel > 80% minimaal invasief wordt geopereerd (DUCA registratie). Er worden dan ook geen belemmerende factoren gevonden voor aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

- De belangrijkste voordelen die worden gevonden voor minimaal invasieve vergeleken met open oesophagusresectie zijn het minder voorkomen van postoperatieve pulmonale en cardiale complicaties met een moderate grade of evidence. Het voorkomen van naadlekkages, de lymfeklieropbrengst en het R0 resectie percentage lijken vergelijkbaar, ook al is de level of evidence laag. Er wordt ook mogelijk een overlevingsvoordeel gezien en een betere kwaliteit van leven, echter met een low grade of evidence.

- Minimaal invasieve oesophaguschirurgie wordt reeds in de meeste Nederlandse centra toegepast. Er is echter, gezien de moderate tot very low grades of evidence, geen reden om geen open chirurgie aan te bevelen. Het gaat hierbij vooral om de lokale expertise. Het belangrijkste doel van de operatie is een radicale resectie met adequate lymphadenectomie. Indien echter de expertise voor minimaal invasieve chirurgie aanwezig is, kan dit voordelen hebben voor de patient, met minder complicaties en mogelijk een overlevingsvoordeel en betere kwaliteit van leven.

Een minimaal invasieve oesophagusresectie wordt geadviseerd wanneer de expertise daarvoor aanwezig is, omdat dit kan leiden tot minder pulmonale en cardiale complicaties en mogelijk een betere kwaliteit van leven en overleving.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Minimally invasive surgery for esophageal cancer was first introduced in 1992 and has since then gradually gained more widespread use, especially in the Netherlands, following the publication of the Dutch TIME trial in 2012 (Straatman, 2017; Cuschieri, 1994). Currently, more than 80% of esophagectomies in the Netherlands is performed minimally invasively (DUCA registration). This chapter investigates the available evidence comparing minimally invasive with open esophagectomy.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Critical

|

Low GRADE |

Minimally invasive esophagectomy may increase overall survival when compared with open esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer.

Source: Guo, 2013; Maas, 2015; Mariette, 2019; Nuytens, 2021; Paireder, 2018; Straatman, 2017 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Minimally invasive esophagectomy probably results in little to no difference in anastomotic leakage when compared with open esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer.

Source: Biere, 2012; Guo, 2013; Ma, 2018; Mariette, 2019; Paireder, 2018; Van der Sluis, 2019 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Minimally invasive esophagectomy probably reduces cardiac complications when compared with open esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer.

Source: Biere, 2012; Guo, 2013; Ma, 2018; Mariette, 2019; Paireder, 2018; Van der Sluis, 2019 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Minimally invasive esophagectomy probably reduces pulmonary complications when compared with open esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer.

Source: Biere, 2012; Guo, 2013; Ma, 2018; Mariette, 2019; Paireder, 2018; Van der Sluis, 2019 |

|

Low GRADE |

Minimally invasive esophagectomy may increase quality of life when compared with open esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer.

Source: Biere, 2012; Van der Sluis, 2019; Song, 2021; Wan, 2020 |

Important

|

Low GRADE |

Minimally invasive esophagectomy may result in little to no difference regarding pain when compared with open esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer.

Source: Biere, 2012; Ma, 2018; Van der Sluis, 2019 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of minimally invasive esophagectomy on time to recovery when compared with open esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer.

Source: Van der Sluis, 2019 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of minimally invasive esophagectomy on the length of hospital stay when compared with open esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer.

Source: Biere, 2012; Guo, 2013; Song, 2021 |

|

Low GRADE |

Minimally invasive esophagectomy may result in little to no difference in R0 resection margin when compared with open esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer.

Source: Biere, 2012; Mariette, 2019; Van der Sluis, 2019 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of minimally invasive esophagectomy on lymph node yield when compared with open esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer.

Source: Biere, 2012; Guo, 2013; Mariette, 2019; Van der Sluis, 2019 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The systematic review by Muller-Stich (2021) was included as the basis for the literature analysis. In this review, six RCTs with eight publications in total (Biere, 2012; Maas, 2015; Straatman, 2017; Guo, 2013; Ma, 2018; Mariette, 2019; Paireder, 2018; van der Sluis, 2019) were included. Additionally, three RCT (Nuytens, 2021; Song, 2022; Wan, 2020) were included that were published after the systematic review by Muller-Stich (2021). Table 1 lists the types of intervention and total sample size of each study. All studies used open esophagectomy as the control treatment.

Table 1. Study characteristics

|

Study |

Intervention |

Sample size (n) |

|

Biere, Maas, Straatman* |

Totally minimally invasive |

115 |

|

Guo |

Totally minimally invasive |

221 |

|

Ma |

Totally minimally invasive |

144 |

|

Van der Sluis |

Totally minimally invasive (robot-assisted) |

109 |

|

Paireder |

Hybrid (abdominal part laporoscopic) |

26 |

|

Mariette, Nuytens* |

Hybrid (abdominal part laporoscopic) |

205 |

|

Song |

Totally minimally invasive |

122 |

|

Wan |

Totally minimally invasive |

120 |

* studies are describing the same trial population

Results

The systematic review by Muller-Stich (2021) was used as the basis for this literature analysis, but due to incomplete reporting, most data was extracted from the individual studies. Survival data had to be extracted for a few studies because no event data was given.

Overall survival

One-year survival

Four studies reported the overall survival after one year (Guo, 2013; Maas, 2015; Paireder, 2018; Mariette, 2019). Guo (2013) and Maas (2015) both used a totally minimally invasive approach, whereas Paireder (2018) and Mariette (2019) both used a hybrid invasive approach. For Guo (2013) and Paireder (2018), the data was extracted using WebPlotDigitizer.

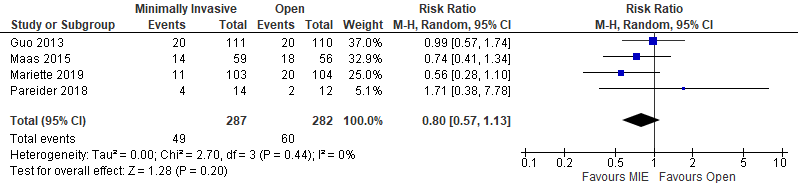

In total, there were 49 events (17%) in the intervention group and 60 events (21%) in the control group. This resulted in a relative risk of 0.80 (95% CI; 0.57 to 1.13) (figure 1). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 1. One-year survival

Minimally invasive versus open

Two studies used a minimally invasive approach (Guo, 2013; Maas, 2015). In total, there were 34 events in 170 patients in the intervention group and 38 events in the 166 patients in the control group (.

Hybrid versus open

Two studies used a minimally invasive approach (Paireder, 2018; Mariette, 2019). In total, there were 15 events in 117 patients in the intervention group and 22 events in the 116 patients in the control group.

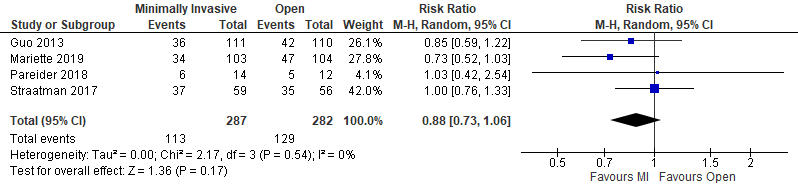

Three-year survival

Four studies reported the overall survival after three years (Guo, 2013; Straatman, 2017; Paireder, 2018; Mariette, 2019). Guo (2013) and Straatman (2017) both used a totally minimally invasive approach, whereas Paireder (2018) and Mariette (2019) both used a hybrid invasive approach. For Guo (2013), Straatman (2017), and Paireder (2018), the data was extracted using WebPlotDigitizer. Straatman (2017) reported two different populations and, in concurrence with the data from Maas (2015), the full responder data was used for this analysis. In total, there were 113 events (39%) in the intervention group and 129 events (45%) in the control group. This resulted in a relative risk of 0.88 (95% CI; 0.63 to 1.02), which is a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 2. Three-year survival

Minimally invasive versus open

Two studies used a minimally invasive approach (Guo, 2013; Straatman, 2017). In total, there were 73 events in 170 patients in the intervention group and 77 events in the 166 patients in the control group.

Hybrid versus open

Two studies used a minimally invasive approach (Paireder, 2018; Mariette, 2019). In total, there were 40 events in 117 patients in the intervention group and 52 events in the 116 patients in the control group.

Five-year survival

Two studies reported the overall survival after five years (Paireder, 2018; Nuytens, 2021). Both studies used a hybrid invasive approach. In the study of Paireder (2018), there were 7 events (50%) in the intervention group, compared to 5 events (42%) in the control group. In the study of Nuytens (2021), there were 42 events (41%) in the intervention group compared to 55 events (53%) in the control group. This results in a total number of 49 events (42%) in 117 patients in the intervention group compared to 60 events in the control group (52%). This difference is clinically relevant.

Complications

Complications were split up in three categories: anastomotic leakage, cardiac complications, and pulmonary complications. All individual cardiac and pulmonary complications reported in the studies were added to these two main groups.

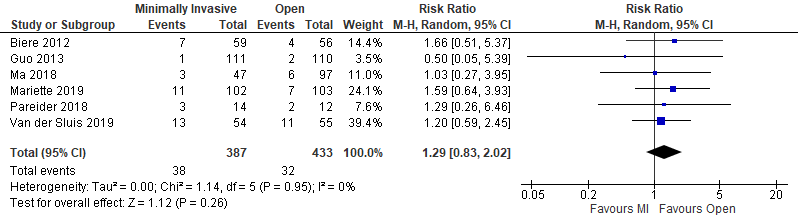

Anastomotic leakage

Six studies reported on anastomotic leakage (Biere, 2012; Guo, 2013; Ma, 2018; Paireder, 2018; Mariette, 2019; Van der Sluis, 2019). In total, there were 38 events (10%) in the intervention group, compared to 32 events (7%) in the control group. This resulted in a relative risk ratio of 1.29 (95% CI; 0.83 to 2.02). This is not clinically relevant.

Figure 3. Anastomotic leakage – minimally invasive and hybrid versus open

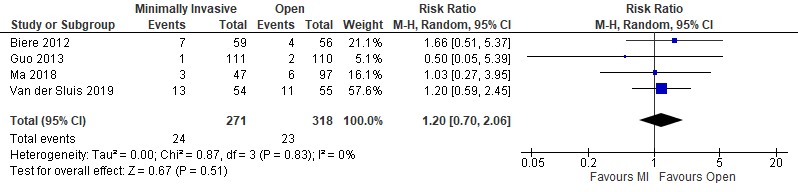

Minimally invasive versus open

Four studies used a minimally invasive approach (Biere, 2012; Guo, 2013; Ma, 2018; Van der Sluis, 2019). In total, there were 24 events (9%) in the intervention group and 23 events (7%) in the control group. This resulted in a relative risk ratio of 1.20 (95%CI; 0.70 to 2.06) which is not clinically relevant.

Figure 4. Anastomotic leakage - totally minimally invasive only versus open

Hybrid versus open

Two studies used a minimally invasive approach (Paireder, 2018; Mariette, 2019). In total, there were 14 events (12%) in the intervention group and 9 events (7%) in the control group. This is clinically relevant.

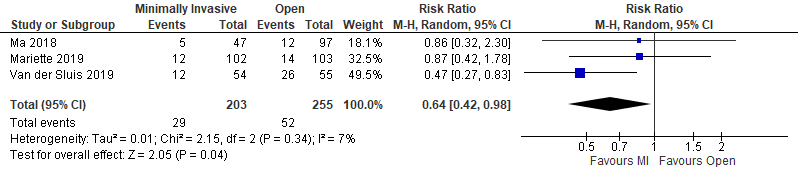

Cardiac complications

Three studies reported on cardiac complications (Ma, 2018; Mariette, 2019; Van der Sluis, 2019). In total, there were 29 events (14%) in the intervention group, compared to 52 events (20%) in the control group. This resulted in a relative risk ratio of 0.64 (95% CI; 0.42 to 0.98), which is a clinically relevant difference in favor of minimally invasive surgery.

Figure 5. Cardiac complications – minimally invasive and hybrid versus open

Minimally invasive versus open

Ma (2018) and Van der Sluis (2019) used a totally minimally invasive approach, where Van der Sluis’ was a robot-assisted trial. In total, there were 17 events (17%) in the intervention group and 38 events (25%) in the control group. This is clinically relevant.

Hybrid versus open

Mariette (2019) used a hybrid minimally invasive approach. There were 12 events (12%) in the intervention group and 14 events (14%) in the control group. This difference is not clinically relevant.

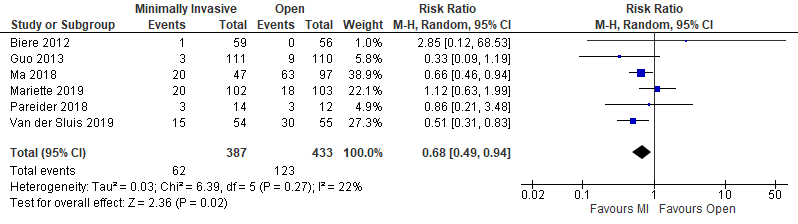

Pulmonary complications

Six studies reported on anastomotic leakage (Biere, 2012; Guo, 2013; Ma, 2018; Paireder, 2018; Mariette, 2019; Van der Sluis, 2019). In total, there were 62 events in 387 patients (16%) in the intervention group, compared to 123 events in the 433 patients (28%) in the control group. This resulted in a relative risk ratio of 0.68 (95% CI; 0.49 to 0.94), which is a clinically relevant difference in favor of minimally invasive surgery.

Figure 6. Pulmonary complications - minimally invasive and hybrid versus open

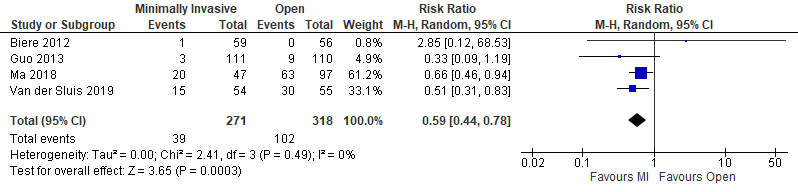

Minimally invasive versus open

Four studies used a minimally invasive approach (Biere, 2012; Guo, 2013; Ma, 2018; Van der Sluis, 2019). In total, there were 39 events in 271 patients (14%) in the intervention group and 102 events in the 318 patients (32%) in the control group. This difference is clinically relevant.

Figure 7. Pulmonary complications - totally minimally invasive only versus open

Hybrid versus open

Two studies used a minimally invasive approach (Paireder, 2018; Mariette, 2019). In total, there were 23 events in 116 patients (20%) in the intervention group and 21 events in the 115 patients (18%) in the control group. This difference is not clinically relevant.

The study of Wan (2020) reported overall complications. Nine complications (15%) were reported in the intervention group and 28 (46.7%) in the control group. This difference is clinically relevant.

Quality of life

Four studies reported quality of life (Biere, 2012; Van der Sluis, 2019; Song, 2021; Wan, 2020). All studies used a minimally invasive approach, where Van der Sluis’ (2019) was robot-assisted.

Biere (2012) reported the physical and mental component summary score of the SF-36, the EORTC C30 Global health score, and the OES 18 Talking and Pain scores six weeks post-surgery. Van der Sluis reported the health-related quality of life and the physical functioning six weeks post-surgery. Song (2021) reported quality of life using the Quality of Life Questionnaire-Lung which includes five domains. A higher score represents a better quality of life. Wan (2020) reported quality of live using the EORTC C30 Global health score.

For the SF-36 and the C30 questionnaires, a higher value means a better quality of life; for the OES18, a lower value means a better quality of life. In Biere (2012), the intervention group consisted of 59 patients and the control group of 56 patients. In Van der Sluis (2019), the intervention group consisted of 31 patients and the control group of 33 patients.

The average physical component summary score of the SF-36 as used in Biere (2012) for the intervention group was 42 (95% CI; 39 to 46) compared to the control group which scored 36 (95% CI; 34 to 39). The average mental component of the SF-36 for the intervention group was 46 (95% CI; 41 to 50) compared to the control group which scored 45 (95% CI; 40 to 50). These differences are not clinically relevant.

For the talking section of the OES 18 in Biere (2012), the intervention group scores on average 18 (95% CI; 10 to 26) compared to the control group which scores 37 (95% CI; 25 to 49). For the pain section of the OES 18, the intervention group scores on average 8 (95% CI; 5 to 11) compared to the control group which scores 19 (95% CI; 13 to 26). These differences are clinically relevant.

For the C30 Global health score in Biere (2012), the intervention group scores on average 61 (95% CI; 56 to 67) compared to the control group which scores on average 51 (95% CI; 45 to 58). This difference is clinically relevant.

For the C30 Global health score in Van der Sluis (2019), the intervention group scores on average 68.7 (95% CI; 51.5 to 75.9) compared to the control group which scores on average 57.6 (95% CI; 50.6 to 64.6). This difference is not clinically relevant.

The physical functioning score in the intervention group was on average 69.3 (95% CI; 61.6 to 76.9) and in the control group 58.6 (95% CI; 51.1 to 66.0). This difference is clinically relevant.

Song (2021) reported QOL score on the domain ‘role function’ of 61.56 (2.01 SD) in the intervention group and 50.34 (2.12 SD) in the control group. Regarding the domain ‘emotional functioning’ mean score in the intervention group was 61.71 (2.12 SD) and in the control group 49.80 (2.03). Mean score on the domain ‘physical function’ was 60.88 (2.07 SD) in the intervention group and 51.36 (2.12 SD) in the control group. Mean score on the domain ‘cognitive function’ in the intervention group was 63.57 (2.91 SD) and 50.22 (2.76) in the control group. Regarding the final domain ‘social function’ mean score in the intervention group was 60.16 (2.05 SD) and 51.41 (2.35 SD) in the control group. These differences are clinically relevant.

Wan (2020) reported mean C30 Gobal health score of 88.04 (18.64 SD) in the intervention group and 80.78 (15.76 SD) in the control group. This difference is not clinically relevant.

Pain

Three studies reported pain (Biere, 2012; Ma, 2018; Van der Sluis, 2019). Biere (2012) and Van der Sluis (2019) both uses the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), whereas Ma (2018) used the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS). All three studies used a totally minimally invasive approach, where Van der Sluis’ was robot-assisted.

Biere (2012) reported the mean VAS ten days post-operation. The intervention group of 56 patients had a mean VAS score of 2 (SD 2) compared to the 59 patients in the control group who had a mean VAS score of 3 (SD 2). This difference is clinically relevant.

Van der Sluis (2019) also used the VAS, but they reported the mean average scores of the first fourteen days post-surgery. The intervention group of 54 patients had a mean VAS score of 1.86 compared to the 55 patients in the control group who had a mean VAS score of 2.62. Ma (2018) reported the average NRS score of the first seven days post-surgery. The intervention group of 72 patients reported an NRS score of 1.88 (SD 0.54), compared to the control group of 72 patients who reported an NRS score of 2.16 (SD 0.58). These differences are not clinically relevant.

Time to recovery

Van der Sluis (2019) was the only study that reported on the time to recovery, which was the median day that patients were functionally recovered. This study investigated a robot-assisted minimally invasive approach. In the 54 patients of the intervention group consisted of 54 patients and the control group of patients. The median number of days that patients were functionally recovered was 10 (IQR; 9 to 13) compared to the control group where the median number of days was 13 (IQR; 9 to 34). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Length of hospital stay

Three studies reported length of hospital stay (Biere, 2012; Guo, 2013; Song, 2021).

Biere (2012) reported median intensive care unit stay. Median stay in the intervention group was 1 day (range 0-50) and 1 day (range 0-106) in the control group. This difference is not clinically relevant.

Guo (2013) used a minimally invasive approach and consisted of 110 patients in the intervention group and 111 patients in the control group. The mean length of hospital stay in the intervention group was 9.6 days (SD 1.7) compared to the control group who were in the hospital for an average of 11.4 days (SD 2.3). We then calculated a mean difference which resulted in -1.80 (95% CI; -2.33 to -1.27), which is a clinically relevant difference in favor of minimally invasive surgery.

Song (2021) reported mean length of hospital stay. Mean length of stay in the intervention group was 14.82 days (2.33 SD) and in the control group 20.03 days (2.21 SD). The calculated mean difference is -5.21 (95%CI -6.01 to -4.40), which is clinically relevant in favor of minimally invasive surgery.

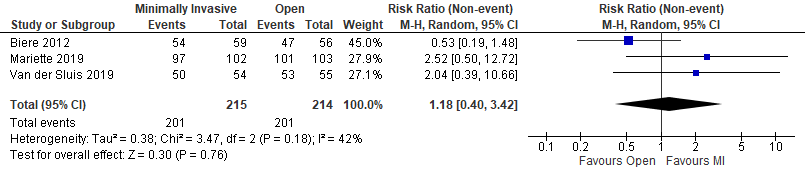

R0 resection margin

Three studies reported on R0 resection margins (Biere, 2012; Mariette, 2019; Van der Sluis, 2019). Biere (2012) and Van der Sluis (2019) used a totally minimally invasive approach, where Van der Sluis’ investigated a robot-assisted esophagectomy; Mariette (2019) investigated a hybrid minimally invasive approach. In total, an R0 resection was performed in 201 out of 215 patients (93%) in the intervention group, compared to 201 cases in the 214 patients (94%) in the control group. We then calculated a relative risk ratio which resulted in 1.18 (95% CI; 0.40 to 3.42) (figure 8). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 8+. R0 resection margin

Lymph node yield

Five studies reported lymph node yield (Biere, 2012; Guo, 2013; Mariette, 2019; Van der Sluis, 2019; Song, 2021). Biere (2012), Guo (2013), and Van der Sluis (2019) investigated a totally minimally invasive approach, where Van der Sluis’ was robot-assisted. Mariette (2019) investigated a hybrid minimally invasive approach. Guo (2013) reported the mean number of resected lymph nodes, where Biere (2012), Mariette (2019), and Van der Sluis (2019) reported the median number of resected lymph nodes.

Guo (2013) reported a mean of 24.3 (SD 21.0) in the intervention group of 111 patients, compared to a mean of 19.2 (SD 12.5) in the control group of 110 patients, which is clinically relevant.

Biere (2012) reported a median of 20 (IQR; 3 to 44) in the intervention group of 59 patients, compared to 21 (IQR; 7 to 47) in the control group of 56 patients. Mariette (2019) reported a median of 21 (IQR; 7 to 76) in the intervention group of 102 patients, compared to 22 (IQR; 9 to 64) in the control group of 103 patients. These differences are not clinically relevant.

Van der Sluis reported a median of 27 (IQR; 17 to 33) in the intervention group of 54 patients, compared to 25 (IQR; 17 to 31) in the control group of 55 patients, which is clinically relevant.

Song (2021) reported mean lymph node dissections of 15.36 (2.21 SD) in the intervention group of 61 patients and 11.86 (3.01 SD) in the control group of 61 patients.

Level of evidence of the literature

Critical outcomes

Overall survival

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure overall survival was downgraded by two levels to Low GRADE because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Anastomotic leakage

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anastomotic leakage was downgraded by one level to Moderate GRADE because of number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Cardiac complications

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cardiac complications was downgraded by one level to Moderate GRADE because of number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Pulmonary complications

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pulmonary complications was downgraded by one level to Moderate GRADE because of number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Quality of life

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by two levels to Low GRADE because of study limitations (risk of bias, -2).

Important outcomes

Pain

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain was downgraded by two levels to Low GRADE because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Time to recovery

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure time to recovery was downgraded by three levels to Very Low GRADE because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and number of included patients (imprecision, -2).

Length of hospital stay

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure length of hospital stay was downgraded by three levels to Very Low GRADE because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1), applicability (bias due to indirectness, -1) and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

R0 resection margin

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure R0 resection margin was downgraded by two levels to Low GRADE because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1) and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Lymph node yield

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure lymph node yield was downgraded by three levels to Very Low GRADE because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1), conflicting results (inconsistency, -1) and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effect of minimally invasive surgery compared with open surgery on complications, pain, time to recovery, length of hospital stay, R0 resection, lymph node yield, quality of life, and overall survival in patients undergoing esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma?

PICO 1

P: Patients with an esophageal carcinoma

I: Minimally invasive surgery (MIE, RAMIE, conventional minimally invasive surgery)

C: Open surgery

O: Complications, pain, time to recovery, length of hospital stay, R0 resection, lymph node yield, quality of life and overall survival

PICO 2

P: Patients with an esophageal carcinoma

I: Hybrid surgery (Minimally invasive surgery combined with open surgery)

C: Open surgery

O: Complications, pain, time to recovery, length of hospital stay, R0 resection, lymph node yield, quality of life and overall survival

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered complications, quality of life and overall survival as a critical outcome measure for decision making and pain, time to recovery, length of hospital stay, R0 resection and lymph node yield as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following differences as a minimal clinically (patient) important:

- Complications: Absolute difference ≥1% for lethal complications, or ≥5% for severe complications

- Pain: Change of 10 on 100mm (1 on 10) Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (Myles, 2017)

- Time to recovery: > 1 week

- Length of hospital stay: > 1 day

- R0 resection: Absolute difference >5% or absolute difference >3% and Hazard Ratio (HR) <0.7

- Lymph node yield: Number of resected lymph nodes >10% difference

- Quality of life: A difference of 10 points on the quality of life instrument EORTC QLQ-C30 or a difference of a similar magnitude on other quality of life instruments.

- Overall survival: >5% or >3% and HR<0.70

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until June 22nd 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 499 hits. The systematic review was selected based on the following criteria:

- Minimum of two databases searched;

- Detailed search strategy with search date;

- In- and exclusion criteria;

- Evidence table for included studies;

- Risk of bias assessment per study.

Additional studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- The study population had to meet the criteria as defined in the PICO;

- The intervention and comparison had to be as defined in the PICO;

- Outcomes had to be as defined in the PICO;

- Research type: Randomized-controlled trial (RCT);

- Articles written in English or Dutch.

30 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 19 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and one systematic review (together with the included RCTs) and three additional RCTs were included.

Results

One systematic review and three additional studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- 1 - Biere SS, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Maas KW, Bonavina L, Rosman C, Garcia JR, Gisbertz SS, Klinkenbijl JH, Hollmann MW, de Lange ES, Bonjer HJ, van der Peet DL, Cuesta MA. Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012 May 19;379(9829):1887-92. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60516-9. Epub 2012 May 1. PMID: 22552194.

- 2 - Cuschieri A. Thoracoscopic subtotal oesophagectomy. Endosc Surg Allied Technol. 1994 Feb;2(1):21-5. PMID: 8081911.

- 3 - Dutch Upper GI Cancer Audit, DUCA. https://dica.nl/duca

- 4 - Guo, M., Xie, B., Sun, X. et al. A comparative study of the therapeutic effect in two protocols: video-assisted thoracic surgery combined with laparoscopy versus right open transthoracic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer management. Chin. -Ger. J. Clin. Oncol.12, 68-71 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10330-012-0966-0

- 5 - Lee L, Sudarshan M, Li C, Latimer E, Fried GM, Mulder DS, Feldman LS, Ferri LE. Cost-effectiveness of minimally invasive versus open esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013 Nov;20(12):3732-9. Doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3103-6. Epub 2013 Jul 10. PMID: 23838923.

- 6 - Ma G, Cao H, Wei R, Qu X, Wang L, Zhu L, Du J, Wang Y. Comparison of the short-term clinical outcome between open and minimally invasive esophagectomy by comprehensive complication index. J Cancer Res Ther. 2018;14(4):789-794. Doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_48_18. PMID: 29970654.

- 7 - Maas KW, Cuesta MA, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Roig J, Bonavina L, Rosman C, Gisbertz SS, Biere SS, van der Peet DL, Klinkenbijl JH, Hollmann MW, de Lange ES, Bonjer HJ. Quality of Life and Late Complications After Minimally Invasive Compared to Open Esophagectomy: Results of a Randomized Trial. World J Surg. 2015 Aug;39(8):1986-93. Doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3100-y. PMID: 26037024; PMCID: PMC4496501.

- 8 - Müller-Stich BP, Probst P, Nienhüser H, Fazeli S, Senft J, Kalkum E, Heger P, Warschkow R, Nickel F, Billeter AT, Grimminger PP, Gutschow C, Dabakuyo-Yonli TS, Piessen G, Paireder M, Schoppmann SF, van der Peet DL, Cuesta MA, van der Sluis P, van Hillegersberg R, Hölscher AH, Diener MK, Schmidt T. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and individual patient data comparing minimally invasive with open oesophagectomy for cancer. Br J Surg. 2021 Sep 27;108(9):1026-1033. Doi: 10.1093/bjs/znab278. PMID: 34491293.

- 9 - Nuytens F, Dabakuyo-Yonli TS, Meunier B, Gagnière J, Collet D, DJourno XB, Brigand C, Perniceni T, Carrère N, Mabrut JY, Msika S, Peschaud F, Prudhomme M, Markar SR, Piessen G; Fédération de Recherche en Chirurgie (FRENCH) and French Eso-Gastric Tumors (FREGAT) Working Groups. Five-Year Survival Outcomes of Hybrid Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy in Esophageal Cancer: Results of the MIRO Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2021 Apr 1;156(4):323-332. Doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.7081. PMID: 33595631; PMCID: PMC7890455.

- 10 - Paireder M, Asari R, Kristo I, Rieder E, Zacherl J, Kabon B, Fleischmann E, Schoppmann SF. Morbidity in open versus minimally invasive hybrid esophagectomy (MIOMIE): Long-term results of a randomized controlled clinical study. Eur Surg. 2018;50(6):249-255. Doi: 10.1007/s10353-018-0552-y. Epub 2018 Aug 7. PMID: 30546384; PMCID: PMC6267426.

- 11 - Song J, Chu F, Zhou W, Huang Y. Efficacy of thoracoscopy combined with laparoscopy and esophagectomy and analysis of the risk factors for postoperative infection. Am J Transl Res. 2022 Jan 15;14(1):355-363. PMID: 35173853; PMCID: PMC8829591.

- 12 - Straatman J, van der Wielen N, Cuesta MA, Daams F, Roig Garcia J, Bonavina L, Rosman C, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Gisbertz SS, van der Peet DL. Minimally Invasive Versus Open Esophageal Resection: Three-year Follow-up of the Previously Reported Randomized Controlled Trial: the TIME Trial. Ann Surg. 2017 Aug;266(2):232-236. Doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002171. PMID: 28187044.

- 13 - Wan Y, Fang L, Yin L, Zheng S, Zhao J, Peng B, Jiang D. Curative effects and influence on patient's immune function of thoracoscopic esophagectomy. Int J Clin Ex Med. 2020 Nov;13(11): 9033-9093

Evidence tabellen

Research question: What is the effect of minimally invasive surgery compared with open surgery on complications, pain, time to recovery, length of hospital stay, R0 resection, lymph node yield, quality of life, and overall survival in patients undergoing esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Nuytens, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Thirteen hospitals in France

Funding: The Multicentre Randomized Controlled Phase III Trial was funded by the PHRC. This follow-up study received no additional funding.

Conflict of interest: Dr Mabrut reported receiving grants from the National Cancer Research Project during the conduct of the study. Dr Piessen reported receiving grants from Institut National du Cancer during the conduct of the study; nonfinancial support in the past from Medtronic; and personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Stryker, and Nestle as well as personal fees in the past from Amgen, Hoffmann-La Roche, and MSD outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. |

Inclusion criteria: ‐ Clinical stage I-III (cT1-T3, N1-2, M0) tumors ‐ Receipt or nonreceipt of neoadjuvant radiotherapy, chemotherapy or a combination of both ‐ World Health Organization performance- status score of 0, 1 or 2 and the ability to undergo the proposed surgical procedure. ‐ Ability to provide a written informed consent ‐ Ability to attend to the scheduled follow-up consultations

Exclusion criteria: ‐ Partial pressure of arterial oxygen of ≤60 mm Hg in ambient air ‐ Partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide of ≥ 45 mmHg ‐ Forced expiratory volume in 1 second ≤1000 ml ‐ Liver cirrhosis ‐ Myocardial infarction or progressive coronary artery disease ‐ Peripheral arterial occlusive diseases (Leriche-Fontaine stage ≥ II) ‐ Weight loss of > 15 % in the 6 months prior to cancer diagnosis ‐ Presence of another synchronous malignancy ‐ Simultaneous inclusion in any other experimental treatment protocol. ‐ Histological subtype of esophageal cancer other than squamous-cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma ‐ Tumor located at the level of the pharyngoesophageal junction, the cervical oesophagus, the upper third of the oesophagus or the gastroesophageal junction (Siewert type II and III) ‐ Distant metastases including peritoneal carcinomatosis, metastasis to supraclavicular and coeliac lymph nodes ‐ Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy or tumor involvement into adjacent mediastinal structures ‐ Patients not eligible for laparoscopy ‐ Previous history of a supra-umbilical laparotomy

N total at baseline: Intervention: 103 Control: 104

Important prognostic factors2: Median age (range): I: 59 (23-75) C: 62 (41-78)

Sex: I: 85% M / 15% F C: 84% M / 16% F

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Hybrid minimally invasive esophagectomy

|

Open esophagectomy |

Length of follow-up: Median 58.2 months (95% CI; 56.5 to 63.8)

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=1 (1%) Reasons: Excluded from analysis of intraoperative and postoperative morbidity because of no resection

Control: N=1 (1%) Reasons: Excluded from analysis of intraoperative and postoperative morbidity because of no resection

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 0 Control: 0

|

Overall survival after 5 years (hazard ratio with CI) 0.71 (95% CI; 0.48 to 1.06)

|

|

|

Song, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Hospital, China

Funding: Not reported

Conflicts of interest: None |

Inclusion criteria1) Patients diagnosed with EC by pathological diagnosis and met the surgical criteria; (2) Patients with pathological stages i-IIb; and (3) Patients aged 45-75 years.

Exclusion criteria: 1) Patients with malignant tumors other than EC; (2) Patients with severe hepatorenal dysfunction or surgical contraindications; (3) Patients who underwent chemoradiotherapy before surgery; (4) Patients with lymph node metastasis, communication impairment or cognitive dysfunction; and (5) Patients who could not cooperate with the study.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 61 Control: 61

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: 62.4 ± 7.4

Sex: I: 57% M/ 43% F C: 54% M/ 46% F

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Minimally invasive esophagectomy

|

Open esophagectomy

|

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 0 Control: 0

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 0 Control: 0

|

Length of hospital stay Mean (SD) I: 14.82 (2.33) C: 20.03 (2.21)

Quality of life (Mean (SD) Intervention Role function: 61.56 (2.01) Emotional function: 61.71 (2.12) Physical function: 60.88 (2.07) Cognitive function: 63.57 (2.91) Social function: 60.16 (2.05) Control Role function: 50.34 (2.12) Emotional function: 49.80 (2.03) Physical function: 51.36 (2.11) Cognitive function: 50.22 (2.76) Social function: 51.41 (2.35)

Lymph node dissections Mean (SD) I: 15.36 (2.21) C: 11.86 (3.01)

|

|

|

Wan, 2020 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Hospital, China

Funding: Not reported

Conflicts of interest: None |

Inclusion criteria: 1) Confirmed by pathological biopsy. (2) No contraindication to the methods used in this study. (3) All patients underwent thoracoscopic esophagectomy alone. (4) With complete clinical data. (5) No cognitive impairment. (6) TNM clinical stage I-III. (7) No abnormal coagulation.

Exclusion criteria: 1) Withdrawal from the study halfway. (2) Those who cannot follow the doctor’s instructions and do not cooperate with the treatment. (3) Heart and lung function intolerant. (4) Those with other malignant tumors. (5) Immune system disorders. (6) Patients who have been treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy before operation.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 60 Control: 60

Important prognostic factors: Age ± SD: I: 50.2 ± 3.7 C: 50.3 ± 3.6

Sex: I: 57% % M/ 43% F C: 58% M / 42% F

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Minimally invasive esophagectomy

|

Open esophagectomy

|

Length of follow-up: 7 days

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 0 Control: 0

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 0 Control: 0

|

Quality of life (EORTC QLQ-C30) Mean (SD) I: 88.04 (18.64) C: 80.78 (15.76)

Complications (N) I: 9 (15%) C: 28 (46.7%)

|

|

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

Research question: Research question: What is the effect of minimally invasive surgery compared with open surgery in patients undergoing esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Nuytens, 2021 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Randomization was performed centrally by means of a stratified-field block randomization (blocks of 4) for each participating center. |

Probably yes

Reason: Prepared numbers envelopes were used |

Definitely no

Reason: Surgeons and patients could not be blinded due to the nature of the intervention; other personnel not reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: No loss to follow-up |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns

|

|

Song, 2022 |

Probably no

Reason: Study only mentions ‘randomly divided’ |

Definitely no

Reason: not reported |

Definitely no

Reason: Surgeons and patients could not be blinded due to the nature of the intervention; other personnel not reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: No loss to follow-up |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

HIGH |

|

Wan, 2020 |

Probably no

Reason: Study only mentions ‘digital random table’ |

Definitely no

Reason: not reported |

Definitely no

Reason: Surgeons and patients could not be blinded due to the nature of the intervention; other personnel not reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: No loss to follow-up |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

HIGH |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Booka E, Tsubosa Y, Haneda R, Ishii K. Ability of Laparoscopic Gastric Mobilization to Prevent Pulmonary Complications After Open Thoracotomy or Thoracoscopic Esophagectomy for Esophageal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2020 Mar;44(3):980-989. doi: 10.1007/s00268-019-05272-9. PMID: 31722075. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Dantoc M, Cox MR, Eslick GD. Evidence to support the use of minimally invasive esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2012 Aug;147(8):768-76. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2012.1326. PMID: 22911078. |

Systematic review only includes retrospective case-control studies |

|

Huang L, Onaitis M. Minimally invasive and robotic Ivor Lewis esophagectomy. J Thorac Dis. 2014 May;6 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S314-21. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.04.32. PMID: 24876936; PMCID: PMC4037415. |

Narrative review |

|

Khan O, Nizar S, Vasilikostas G, Wan A. Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. J Thorac Dis. 2012 Oct;4(5):465-6. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.08.16. PMID: 23050109; PMCID: PMC3461074. |

Wrong design |

|

Manigrasso M, Vertaldi S, Marello A, Antoniou SA, Francis NK, De Palma GD, Milone M. Robotic Esophagectomy. A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Clinical Outcomes. J Pers Med. 2021 Jul 6;11(7):640. doi: 10.3390/jpm11070640. PMID: 34357107; PMCID: PMC8306060. |

Wrong comparison: RAMIE versus OE or RAMIE versus Laparoscopic |

|

Patel K, Askari A, Moorthy K. Long-term oncological outcomes following completely minimally invasive esophagectomy versus open esophagectomy. Dis Esophagus. 2020 Jun 15;33(6):doz113. doi: 10.1093/dote/doz113. PMID: 31950180. |

No RCT's in SR

|

|

Ramjit SE, Ashley E, Donlon NE, Weiss A, Doyle F, Heskin L. Safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of minimally invasive esophagectomies versus open esophagectomies: an umbrella review. Dis Esophagus. 2022 Dec 14;35(12):doac025. doi: 10.1093/dote/doac025. PMID: 35596955. |

No data extraction from only RCT's possible

|

|

Siaw-Acheampong K, Kamarajah SK, Gujjuri R, Bundred JR, Singh P, Griffiths EA. Minimally invasive techniques for transthoracic oesophagectomy for oesophageal cancer: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BJS Open. 2020 Oct;4(5):787-803. doi: 10.1002/bjs5.50330. Epub 2020 Sep 7. PMID: 32894001; PMCID: PMC7528517. |

Wrong comparisons: Open versus laparoscopic, open versus MIE, MIE versus laparoscopic

|

|

Sugimura K, Miyata H, Kanemura T, Takeoka T, Sugase T, Masuzawa T, Katsuyama S, Motoori M, Takeda Y, Murata K, Yano M. Patterns of Recurrence and Long-Term Survival of Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy Versus Open Esophagectomy for Locally Advanced Esophageal Cancer Treated with Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: a Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2023 Jun;27(6):1055-1065. doi: 10.1007/s11605-023-05615-x. Epub 2023 Feb 7. PMID: 36749557. |

Wrong study design |

|

Szakó L, Németh D, Farkas N, Kiss S, Dömötör RZ, Engh MA, Hegyi P, Eross B, Papp A. Network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on esophagectomies in esophageal cancer: The superiority of minimally invasive surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2022 Aug 14;28(30):4201-4210. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i30.4201. PMID: 36157121; PMCID: PMC9403425. |

Includes comparisons that are not relevant to our PICO |

|

Taioli E, Schwartz RM, Lieberman-Cribbin W, Moskowitz G, van Gerwen M, Flores R. Quality of Life after Open or Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy in Patients With Esophageal Cancer-A Systematic Review. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017 Autumn;29(3):377-390. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2017.08.013. Epub 2017 Aug 24. PMID: 28939239. |

No direct comparison between MIE and OE

|

|

Wang B, Zuo Z, Chen H, Qiu B, Du M, Gao Y. The comparison of thoracoscopic-laparoscopic esophagectomy and open esophagectomy: A meta-analysis. Indian J Cancer. 2017 Jan-Mar;54(1):115-119. doi: 10.4103/ijc.IJC_192_17. PMID: 29199673. |

Does not meet quality SR criteria

|

|

Yibulayin W, Abulizi S, Lv H, Sun W. Minimally invasive oesophagectomy versus open esophagectomy for resectable esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2016 Dec 8;14(1):304. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-1062-7. PMID: 27927246; PMCID: PMC5143462. |

No clear distinction between RCTs and observations studies in SR |

|

Biere SS, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Bonavina L, Rosman C, Roig Garcia J, Gisbertz SS, van der Peet DL, Cuesta MA. Predictive factors for post-operative respiratory infections after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: outcome of randomized trial. J Thorac Dis. 2017 Jul;9(Suppl 8):S861-S867. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.06.61. PMID: 28815084; PMCID: PMC5538980. |

Wrong comparison; factors influencing risk of pneumonia or other complications

|

|

Cuesta MA, Biere SS, van Berge Henegouwen MI, van der Peet DL. Randomised trial, Minimally Invasive Oesophagectomy versus open oesophagectomy for patients with resectable oesophageal cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2012 Oct;4(5):462-4. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.08.12. PMID: 23050108; PMCID: PMC3461077. |

Narrative review |

|

Wan J, Che Y, Kang N, Zhang R. Surgical Method, Postoperative Complications, and Gastrointestinal Motility of Thoraco-Laparoscopy 3-Field Esophagectomy in Treatment of Esophageal Cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2016 Jun 16;22:2056-65. doi: 10.12659/msm.895882. PMID: 27310399; PMCID: PMC4913812. |

Wrong design: Retrospective study

|

|

Yang ZQ, Lu HX, Zhang JH, Wang J. Comparative study on long-term survival results between minimally invasive surgery and traditional resection for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016 Aug;20(16):3368-72. PMID: 27608894. |

Probably no RCT (randomization unclear)

|

|

Yang J, Chen L, Ge K, Yang JL. Efficacy of hybrid minimally invasive esophagectomy vs open esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: A meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019 Nov 15;11(11):1081-1091. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i11.1081. PMID: 31798787; PMCID: PMC6883181. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Yu Y, Han Y. Clinical Effect and Postoperative Pain of Laparo-Thoracoscopic Esophagectomy in Patients with Esophageal Cancer. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022 Jun 26;2022:4507696. doi: 10.1155/2022/4507696. Retraction in: Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2023 Dec 6;2023:9790841. PMID: 35795286; PMCID: PMC9251098. |

No/unclear randomization |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 18-12-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-09-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2021 een multidisciplinair cluster ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van het cluster) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met oesofagus- en maagcarcinoom.

Het cluster oesofagus- en maagcarcinoom bestaat uit meerdere richtlijnen, zie hier voor de actuele clusterindeling. De stuurgroep bewaakt het proces van modulair onderhoud binnen het cluster. De expertisegroepsleden worden indien nodig gevraagd om hun expertise in te zetten voor een specifieke richtlijnmodule. Het cluster oesofagus- en maagcarcinoom bestaat uit de volgende personen:

Clusterstuurgroep

- Dhr. Prof. Dr. P.D. (Peter) Siersema (voorzitter), maag-darm-leverarts, ErasmusMC, Rotterdam; NVMDL

- Mevr. Dr. R.E. (Roos) Pouw, maag-darm-leverarts, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam; NVMDL

- Mevr. Dr. A. (Annemarieke) Bartels – Rutten, radioloog, NKI-AVL, Amsterdam; NVvR

- Dhr. Prof. Dr. M.I. (Mark) van Berge Henegouwen, chirurg, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam; NVvH

- Dhr. Prof. Dr. R. (Richard) van Hillegersberg, chirurg, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht; NVvH

- Dhr. M.C.C.M. (Maarten) Hulshof MD PhD, Radiotherapeut, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam; NVRO (neemt geen deel meer)

- Mevr. Dr. H.W.M. (Hanneke) van Laarhoven, internist, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam; NIV

- Mevr. Dr. E.M. (Liesbeth) Timmermans, bestuurslid Stichting voor Patiënten met Kanker aan het Spijsverteringskanaal; SPKS (tot 1 december 2023)

- Dhr. Dr. E. (Erik) Vegt, nucleair geneeskundige, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam; NVNG

Clusterexpertisegroep

- Dhr. Drs. W.W. (Weibel) Braunius, keel-neus-oorarts, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht; NVKNO

- Mevr. Dr. M.J. (Marc) van Det, chirurg, Ziekenhuisgroep Twente; NVvH

- Mevr. Dr. S.S. (Suzanne) Gisbertz, chirurg, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam; NVvH

- Mevr. Dr. N.C.T. (Nicole) van Grieken, patholoog, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam; NVVP

- Dhr. R. (Ronald) Hoekstra, internist, Ziekenhuisgroep Twente; NIV

- Dhr. R. (Remco) Huiszoon MBA, ervaringsdeskundige en bestuurslid Stichting voor Patiënten met kanker aan het Spijsverteringskanaal excl. darmkanker; SPKS

- Dhr. P.M. (Paul) Jeene MD, radiotherapeut, Radiotherapiegroep; NVRO

- Dhr. Dr. S.M. (Sjoerd) Lagarde, chirurg, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam; NVvH

- Dhr. Dr. R.W.F. (Roelof) van Leeuwen, ziekenhuisapotheker, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam; NVZA

- Dhr. Dr. S.L. (Sybren) Meijer, patholoog, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam; NVVP

- Mevr. B. (Bianca) Mostert, internist, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam; NIV

- Mevr. C.T. (Kristel) Muijs MD PhD, radiotherapeut, UMCG, Groningen; NVRO

- Mevr. L. (Luidmila) Peppelenbosch – Kodach, patholoog, NKI-AVL, Amsterdam; NVVP

- Mevr. Drs. H. (Heidi) Rütten, radiotherapeut, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen; NVRO

- Mevr. M. (Marije) Slingerland, internist, LUMC, Leiden; NIV

- Mevr. Prof. Dr. V.M.C.W. (Manon) Spaander, maag-darm-leverarts, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam; NVMDL

- Mevr. M.E. (Manon) Dik, verpleegkundig specialist, Ziekenhuisgroep Twente; V&VN

- Dhr. C.C.G. (Carlo) Schippers, verpleegkundig specialist, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht; V&VN

Met ondersteuning van:

- Mevr. S.N. (Sarah) van Duijn MSc, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mevr. M. (Miriam) te Lintel Hekkert MSc, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mevr. Dr. C.M.W. (Charlotte) Gaasterland, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle clusterleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van de clusterleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Clusterstuurgroep

|

Clusterlid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Siersema (Voorzitter) |

MDL-arts en Hoofd Endoscopisch Centrum, Radboud University Medical Center

|

Editor in Chief, Endoscopy |

Research funding/advisory board zonder invloed op deze richtlijn |

Geen restrictie |

|

Pouw (tijdelijke voorzitter) |

MDL-arts Amsterdam UMC |

Bestuurslid DUCG - onbetaald. Bestuurslid young ISDE - onbetaald. Bestuurslid Barrett Expertise Centra - onbetaald. Lid beoordelingscommissie ontwikkeling en implementatie KWF - onbetaald. Nationaal afgevaardigde NVMDL voor UEG - onbetaald. Projectleider KWF (PREFER studie). Studie protocol (inclusief inclusie criteria) PREFER studie staat vast. Publicatie resultaten worden pas over vijf jaar verwacht, ruim na datum publicatie richtlijnmodule endoscopische behandeling vroegcarcinoom maag. |

Betaalde deelname aan onderwijscursus georganiseerd door Medtronic Betaald adviseurschap voor Medtronic BV. (scholing en webminar endoscopische behandeling vroege afwijking in slokdarm, geen belang bij gebruik producten) Betaald adviseurschap voor MicroTech Europe (webminar, symposium, m.n. behandeling van lekkages na slokdarmoperaties) |

a) Werkgroeplid werkt niet als enige inhoudsdeskundige aan de module;

|

|

Timmermans |

- Bestuurslid SPKS (Stichting voor Patiënten met kanker aan het Spijsverteringskanaal) 5 uur per week - Gedragswetenschappelijk docent huisartsenopleiding Eerstelijnsgeneeskunde Radboudumc |

Onbetaald vrijwilligerswerk Bestuurslid SPKS (15 uur per week) |

Geen |

Neemt geen deel meer aan cluster - Geen restrictie

|

|

Van Laarhoven |

Hoofd afdeling medische oncologie, Amsterdam UMC |

- Wetenschappelijke raad KWF (onbetaald) - Voorzitter ESMO upper GI faculty (onbetaald) - Lid ESMO Leadership Generation programme (onbetaald) - Lid EORTC upper GI strategy commiittee (onbetaald) |

- Consultant or advisory role: Amphera, AstraZeneca, Beigene, BMS, Daiichy-Sankyo, Dragonfly, Eli Lilly, MSD, Nordic Pharma, Servier - Research funding and/or medication supply: Bayer, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Incyte, Eli Lilly, MSD, Nordic Pharma, Philips, Roche, Servier - Speaker role: Astellas, Benecke, Daiichy-Sankyo, JAAP, Medtalks, Novartis, Travel Congress Management B.V Employment and leadership: Amsterdam UMC, the Netherlands (head of the department of medical oncology) Honorary: ESMO (chair upper GI faculty) |

Geen restrictie |

|

Bartels |

Radioloog, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Van Berge Henegouwen |

Chirurg slokdarm en maagchirurgie Amsterdam UMC Hoogleraar slokdarm en maagchirurgie Universiteit van Amsterdam |

- bestuur DUCA, DICA en voorzitter werkgroep Upper GI (allen onbetaald). |

- Olympus financiering studie (researcher initiated grant) Stryker financiering studie (researcher initiated grant) uitkomsten richtlijn geen invloed op deze bedrijven of studies - Consultancy voor meerdere bedrijven (B. Braun en Viatris) (uitbetaling aan Amsterdam UMC), niet gerelateerd aan richtlijn. |

Geen restrictie |

|

Hulshof |

Radiotherapeut oncoloog Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Neemt geen deel meer aan cluster - Geen restrictie |

|

Van Hillegersberg |

Chirurg, UMC Utrecht |

Proctor Intuitive Surgical Consultant Medtronic |

- Bestuur DUCA, DICA |

Geen restrictie |

|

Vegt |

Nucleair geneeskundige, Afdeling Radiologie en Nucleaire Geneeskunde, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Geen |

- ZonMW-subsidie voor de PLASTIC-studie, programma doelmatigheid van zorg, naar de kosten-effectiviteit van FDG-PET/CT en laparoscopie bij maagcarcinoom. |

Geen restrictie |

|

Van Rossum |

[volgt] |

[volgt] |

[volgt] |

[volgt] |

Clusterexpertisegroep

|

Clusterlid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Huiszoon |

ING Bank N.V. Agile coach expert, full-time |

Buddy voor slokdarmkanker patiënten bij het SPKS, onbetaald. Vanuit persoonlijke ervaring 'klankbord' zijn voor patiënten die nu dezelfde ziekte hebben als ik in 2017 heb gehad |

Neemt deel namens SPKS en hoopt vanuit dat perspectief als ervaringsdeskundige bij te kunnen dragen. Geen boegbeeldfunctie of ander belang |

Geen restrictie |

|

Braunius |

Oncologisch Hoofd-Halschirurg UMC Utrecht Cancer Center |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Van Leeuwen |

Ziekenhuisapotheker - Erasmus MC Afdelingen Apotheek (80%) en Interne Oncologie (20%) |

SIG Oncologie NVZA - onbetaald Werkgroep Geneesmiddel Interacties NVZA/KNMP (betaald "onkosten") Onderwijs PAO Farmacie (betaald "onkosten") |

Industrie: Geneesmiddelen onderzoek i.s.m. Roche, Astellas, BMS, Servier, Boehringer (unrestricted research grants) Fondsen: Stichting Coolsingel, Stichting de Merel, Stichting Mitialto Geen conflict of interest |

a) Werkgroeplid werkt niet als enige inhoudsdeskundige aan de module; b) Werkgroeplid werkt tenminste samen met een ander werkgroeplid met vergelijkbare expertise in alle fasen (studieselectie, data-extractie, evidence synthese, evidence-to-decision, aanbevelingen formuleren) van het ontwikkelproces; c) In alle fasen van het ontwikkelproces is een onafhankelijk methodoloog betrokken; d) Overwegingen en aanbevelingen worden besproken en vastgesteld tijdens een werkgroepvergadering onder leiding van een onafhankelijk voorzitter (zonder gemelde belangen) |

|

Jeene |

Radiotherapeut - Oncoloog bij Radiotherapiegroep PhD candidate - AmsterdamUMC ( 0 uren aanstelling) |

Bestuurslid DUCG - onbetaald |

Studie coördinator en eerste auteur POLDER trail (effectiviteit kortdurende uitwendige radiotherapie, geen externe financiering). PICO is anders dan studie |

Geen restrictie |

|

Gisbertz |

Slokdarmkanker en maagkanker chirurg - Amsterdam UMC |

Bestuur ESDE, NVGIC, ISDE, research commitee EAES, de Groene OK: allen onbetaald |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: KWF: SQA n observational studies (projectleider) CCA: USPIO enhanced MRI in esophageal cancer (projectleider) |

Geen restrictie |

|

Lagarde |

Chirug, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

- lid wetenschappelijke commissie DKCA - bestuurslid werkgroep Upper Gi beiden onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Hoekstra |

Internist-oncoloog, Ziekenhuisgroep Twente (ZGT) |

Lid Concillium Medicinae Internae (onbetaald) |

- Als internist-oncoloog betrokken bij inclusie van patiënten in klinische studies bij oesofagus- en maagcarcinoom. Op dit moment Critics-2 studie en Lyrics studie |

Geen restrictie |

|

Van Det |

Gastro-intestinaal chirurg Ziekenhuis groep Twente (ZGT) |

- Proctor/Instructor voor Intuitive Surgical betreffende Robot-Assisted operaties in de upper-GI zoals: - Slokdarm resecties - Maagresecties - Hernia diafragmatica. |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Rütten |

Radiotherapeut, Radboud UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Van Grieken |

Patholoog, Amsterdam UMC (locatie Vumc), Amsterdam |

Detachering Expertisepanel poliepen BVO-DK, Screeningsorganisatie BVO darmkanker (3 uur/week) |

- KWF - Identificatie van markers voor response op immunotherapie - projectleider - KWF - CRITICS-II klinische trial voor resectabel maagcarcinoom - ZonMW - Effect van chemotherapie bij patienten met microsatelliet instabiel resectabel maagcarcinoom. – projectleider - advisory boards van BMS, MSD |

a) Werkgroeplid werkt niet als enige inhoudsdeskundige aan de module; |

|

Mostert |

Internist-oncoloog, Erasmus MC |

Consultancy voor: BMS, Lilly, Servier |

- BMS: fase 2 studie: nivolumab tijdens actieve surveillance slokdarmcarcinoom Sanofi: cabazitaxel bij AR-v7 positieve prostaatcarcinoom patiënten Pfizer: DLA bij mammacarcinoompatiënten behandeld met CDK4/6 De f1/2 studie betreft research support`; investigator initiated studie waarvoor BMS de medicatie “schenkt” Astra zeneca betreft advisory board. |

a) Werkgroeplid werkt niet als enige inhoudsdeskundige aan de module; |

|

Slingerland |

Internist-oncoloog LUMC |

Geen |

- Advisory board Lilly, Astra Zeneca en BMS |

a) Werkgroeplid werkt niet als enige inhoudsdeskundige aan de module; |

|

Spaander |

MDL-arts 1.0 Fte in Erasmus Universiteit MC (betaald) Voor 6 uur per week gedetacheerd aan de screeningorganisatie voor het BVO darmkanker (betaald) |

Voorzitter NVMDL en NVGE oncologie commissie (onbetaald) |

ZonMW: Gender differencees in Barrett Surveillance, projectleidersrol. Capsulomics: Biomarkers in Barrett slokdarm, projectleidersrol. Lucid: Non-ionvasive tool for Barrett surveillance. Microtech: New Esophageal stent. CELTIC: Blood test bij FIT +patiënten

|

Geen restrictie |

|

Meijer |

Patholoog, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Peppelenbosch - Kodach |

Patholoog, NKI/AVL |

Geen |

Deelname studie inter-observer variabiliteit voor PD-L1 CPS in maagcarcinomen, gefinancierd door BMS, fee naar de werkgever AVL/NKI |

Geen restrictie |

|

Muijs |

Radiotherapeut-Oncoloog Universitaire Medisch Centrum Groningen |

Lid wetenschapscommissie DUCA (Gemandateerde NVRO) Lid werkgroep indicatie protocol protonen radiotherapie (NVRO) |

Project Leider Models Project (KWf funded): ontwikkelen en valideren predictiemodellen voor complicaties na CRT en resectie Principle investigator CLARIFY studie (KWF funded): Observationeel onderzoek naar pulmonale hupertensie als complicatie na thoracale RT Participatie in PROTECT studie (EU funded): RCT fase 3: fotonen vs protonen bij nCRT voor oesofaguscarcinoom Voortrekker protonen RT bij het oesofaguscarcinoom |

Geen restrictie |

|

Dik |

[volgt] |

[volgt] |

[volgt] |

[volgt] |

|

Schippers |

[volgt] |

[volgt] |

[volgt] |

[volgt] |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door de afvaardiging van de Stichting voor Patiënten met kanker aan het Spijsverteringskanaal (SPKS). De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptmodule is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan SPKS en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

‘Minimaal invasieve chirurgie’ (oesofaguscarcinoom) |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat [het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet OF het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft]. Er worden daarom geen financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Need-for-update, prioritering en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de need-for-update fase inventariseerde het cluster de geldigheid van de modules binnen het cluster. Naast de betrokken wetenschappelijke verenigingen en patiëntenorganisaties zijn hier ook andere stakeholders voor benaderd in juni 2021.

Per module is aangegeven of deze geldig is, kan worden samengevoegd met een andere module, obsoleet is en kan vervallen of niet meer geldig is en moet worden herzien. Ook was er de mogelijkheid om nieuwe onderwerpen voor modules aan te dragen die aansluiten bij één (of meerdere) richtlijn(en) behorend tot het cluster. De modules die door één of meerdere partijen werden aangekaart als ‘niet geldig’ zijn meegegaan in de prioriteringsfase. Deze module is geprioriteerd door het cluster.

Voor de geprioriteerde modules zijn door het cluster concept-uitgangsvragen herzien of opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde het cluster welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. Het cluster waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Het cluster definieerde klinisch (patiënt) relevante verschillen, tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

Definitie |

|

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen.

De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID).

Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en deze worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door het cluster wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. Het cluster heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

Bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met het cluster. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door het cluster. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt)organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.