Operatietechniek (open vs. minimaal invasief)

Uitgangsvraag

Welke operatietechniek (open versus minimaal invasief) kan het beste toegepast worden bij een acute abdominale ingreep bij een zwangere patiënt?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg een minimaal invasieve chirurgische benadering bij een acute abdominale ingreep bij een zwangere patiënt. Neem daarbij de grootte van de uterus in een verder gevorderde zwangerschap; de omstandigheden van de ingreep (conditie van de patiënt en van de foetus); en de expertise van de operateur, het team en het ziekenhuis mee in de afweging.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een systematische literatuur analyse uitgevoerd naar de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van laparoscopische ingrepen in vergelijking met conservatieve behandeling (open ingrepen) in zwangere patiënten die een acute abdominale ingreep ondergaan. De bewijskracht voor de gerapporteerde cruciale uitkomstmaten maternale mortaliteit, foetale mortaliteit, vroeggeboorte en miskramen was zeer laag. Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat maternale complicaties werd geen bewijs gevonden. Ook de bewijskracht voor de gerapporteerde belangrijke uitkomstmaten maternale wondcomplicaties, duur van ziekenhuisopname en foetale nood was de bewijskracht zeer laag. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat maternale pijn werd geen bewijs gevonden. De geïncludeerde studies omvatten vaak kleine aantallen events die waren bepaald in een kleine patiëntengroep en alle studies hadden methodologische beperkingen (retrospectieve studie designs en potentiële confounding vaak niet meegenomen), waardoor er mogelijk risico is op vertekening van de studieresultaten (risk of bias) bij de subjectieve uitkomstmaten. Op basis van deze literatuursamenvatting kan geen sterke voorkeur uitgesproken worden over welke type ingreep de voorkeur heeft. Er bestaat hier dan ook een kennislacune.

De richtlijn minimaal invasieve chirurgie (MIC) doet specifieke aanbevelingen ten aanzien van het uitvoeren van laparoscopie in de zwangerschap, mede gebaseerd op de richtlijnen van SAGES (2017) en die van RCOG (2019). De SAGES richtlijn uit 2017 en RCOG consensus uit 2019 gaven aan dat een laparoscopie in elk trimester veilig uitgevoerd kan worden (Ball, 2019; Pearl, 2017). De werkgroep sluit zich aan bij dit advies. Vanuit literatuur in de niet-zwangere patiënt is bekend dat laparoscopie voordelen biedt zoals minder pijn en korter herstel. Alhoewel er geen gerandomiseerd onderzoek is verricht bij zwangeren, valt te verwachten dat deze voordelen ook gelden voor zwangeren. De werkgroep is van mening dat een laparoscopische benadering in ieder trimester deze voordelen heeft ten opzichte van de open benadering.

Zoals in de MIC richtlijn beschreven is het door de groeiende uterus van een zwangere belangrijk om aandacht de besteden aan de introductie van de trocarts en te kijken naar alternatieve locaties voor insufflatie, bijvoorbeeld bij Palmers point. Daarnaast, als de zwangerschap ver gevorderd is, kan overwogen worden om de chirurgische ingreep te combineren met een sectio caesarea of een open procedure te doen. De keuze voor techniek is daarbij afhankelijk van de expertise van de operateur, de rest van het team en het ziekenhuis.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor zwangere vrouwen is de veiligheid van de foetus zeer belangrijk. Er zijn geen aanwijzingen dat de veiligheid van de foetus significant verschilt tussen de minimaal invasieve en open benadering. Het is aannemelijk dat zwangere vrouwen op basis van het kortere postoperatieve herstel en minder pijn de voorkeur geven aan laparoscopie.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Na laparoscopie is er een kortere ziekenhuisopname en een sneller herstel naar dagelijkse activiteiten wat leidt tot lagere kosten.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Minimaal invasieve chirurgie (laparoscopie) is algemeen geaccepteerd en geïntegreerd in de Nederlandse ziekenhuiszorg. De werkgroep verwacht dan ook geen problemen bij implementatie. Bij een gebrek aan expertise kan overplaatsing naar een ander centrum overwogen worden.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Op basis van de literatuur is geen wetenschappelijk bewijs van voldoende kwaliteit gevonden om een voorkeur aan te geven voor een open of een laparoscopische procedure bij een acute abdominale chirurgische ingreep in de zwangerschap. Dit geldt voor zowel de maternale als foetale uitkomstmaten. Wel is het waarschijnlijk dat de voordelen van laparoscopie bij de niet zwangere patiënt (kortere ziekenhuisopname, minder pijn en sneller herstel) ook van toepassing zijn op zwangeren. Bij de afweging voor een laparoscopische procedure moet rekening gehouden worden met de grootte van de uterus van de zwangere vrouw, de omstandigheden van de ingreep (conditie van patiënt en van de foetus) en de expertise van operateur, team en ziekenhuis. Kosten, acceptatie en implementatie van minimale invasieve chirurgie spelen geen rol in de besluitvorming.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Er is een toename in het aantal laparoscopische ingrepen. Dit omdat een laparoscopie minder postoperatieve pijn geeft en een sneller herstel. Ook bij zwangere vrouwen is dit zo. Een Deense studie onderzocht 1.687.176 zwangerschappen die leidden tot een levend geboren kind tussen 1996-2015 (Rasmussen, 2019). Chirurgische ingrepen (exclusief keizersneden) tijdens de zwangerschap werden gecategoriseerd in niet-obstetrische en obstetrische chirurgie, en verder onderverdeeld in laparoscopische of niet-laparoscopische procedures. 108.502 (6.4%) vrouwen ondergingen 117.424 chirurgische procedures. De prevalentie van niet-obstetrische chirurgie in zijn geheel was nagenoeg stabiel (1.5% in 1996–1999 en 1.6% in 2012–2015), maar de prevalentie van niet-obstetrische abdominale of gynaecologische laparoscopische procedures steeg van 0.5% naar 0.8%. Ter illustratie, en buiten de focus van de richtlijn, steeg het aandeel laparoscopische appendectomieën van 4.2% naar 79.2% gedurende de studieperiode. In 1996-1999 werden geen zwangere vrouwen geopereerd voor inwendige herniaties versus 49 patiënten tussen 2012-2015. Chirurgie tijdens de zwangerschap kwam vaker voor bij meerlingzwangerschappen, roken, hogere leeftijd, hogere body mass index en pariteit. Er werd geen literatuur gevonden die de trends in het gebruik van laparoscopische chirurgie bij zwangere vrouwen vergeleek tussen Denemarken en Nederland. De incidentie van laparoscopie versus laparotomie lijkt verschillend per trimester van de zwangerschap en mogelijk ook per indicatie. Ook lijkt dit afhankelijk van ervaring van de operateur. De operatieve behandeling van een appendicitis in de zwangerschap werd geëxcludeerd omdat deze wordt beschreven in de richtlijn acute appendicitis.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Crucial outcome measures maternal or fetal mortality, preterm delivery, serious maternal complications, and miscarriage

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of laparoscopy on maternal mortality when compared to laparotomy in pregnant patients undergoing acute abdominal surgery*. Sources: Barone 1999, Cosenza 1999, Cox 2016, Glasgow 1997 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of laparoscopy on fetal mortality when compared to laparotomy in pregnant patients undergoing acute abdominal surgery*. Sources: Affleck 1999, Barone 1999, Corneille 2010, Cosenza 1999, Curet 1996, Davis 1995, Glasgow 1997 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of laparoscopy on preterm delivery when compared to laparotomy in pregnant patients undergoing acute abdominal surgery*. Sources: Affleck 1999, Barone 1999, Chang 2011, Corneille 2010, Cosenza 1999, Curet 1996, Davis 1995, Glasgow 1997, Visser 2001 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of laparoscopy on miscarriage when compared to laparotomy in pregnant patients undergoing acute abdominal surgery*. Sources: Affleck 1999, Chang 2011, Cosenza 1999, Patel Veverka 2002 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of laparoscopy on serious maternal complications when compared to laparotomy in pregnant patients undergoing acute abdominal surgery*.

Source: - |

Important outcome measures maternal surgical wound complications, maternal pain, length of hospital stay, and fetal distress

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of laparoscopy on wound complications when compared to laparotomy in pregnant patients undergoing acute abdominal surgery*. Sources: Cox 2016, Kuy 2009 |

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of laparoscopy on hospital stay when compared with laparotomy in pregnant patient undergoing acute abdominal surgery*. Sources: Chang 2011, Cox 2016, Kuy 2009, Visser 2001 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of laparoscopy on fetal distress when compared with laparotomy in pregnant patient undergoing acute abdominal surgery*.

Sources: Cosenza 1999, Curet 1996, Kuy 2009 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of laparoscopy on pain when compared to laparotomy in pregnant patients undergoing acute abdominal surgery*.

Source: - |

* acute abdominal surgery based on imaging (suspected) for any of the following diagnoses: cholecystitis, torsion/bleeding of the ovary/parametrium, or internal herniation, or other causes of intestinal obstruction with or without strangulation or ischemia.

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Sedaghat (2017) is a systematic review and meta-analysis of retrospective patient record studies investigating the maternal and fetal complications of laparoscopic compared to open cholecystectomy during pregnancy. The review was based on a literature search from 1985 to 2015 and included 11 studies comprising a total of 9413 patients in the laparoscopic group and 1219 patients in the open group (Affleck, 1999; Barone, 1999; Corneille, 2010; Cosenza, 1999; Cox, 2016; Curet, 1996; Davis, 1995; Glasgow, 1997; Kuy, 2009; Patel Veverka, 2002; Visser, 2001). All studies had methodological limitations with regard to confounding assessment (see RoB table). Characteristics of the included studies are listed in table 1.

Chang (2011) is a retrospective observational study comparing the outcome between laparoscopy and laparotomy in women undergoing surgery for ovarian torsion (OT) during pregnancy. Clinical records of patients with OT during pregnancy between 1997 and 2008 at a university hospital in Taiwan. Data of women identified with surgically proven OT (n=20) were reported. Twelve patients (60%) underwent laparoscopy and eight patients (40%) laparotomy. In the first trimester 9/12 of the women (75%) received laparoscopy, in the second and third trimesters 3/8 women (37.5%) received laparoscopy. The study had methodological limitations with regard to confounding assessment (see RoB table). More specific characteristics of this study are listed in table 1.

Table 1: Study characteristics

|

Study reference |

Population (N; maternal age) |

Trimester/ gestational age |

Intervention |

Control |

|

Affleck 1999 (Sedaghat 2017)

retrospective patient record study (1990-1998)

Country: USA |

I: 45 C: 13

Maternal age |

First trimester (n) I: 3 C: not reported

Second trimester (n) I: 28 C: not reported

Third trimester (n) I: 11 C: not reported

|

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy symptomatic cholelithiasis

|

Laparotomic cholecystectomy symptomatic cholelithiasis |

|

Barone 1999 (Sedaghat 2017)

retrospective patient record study (1992-1996)

Country: USA |

I: 20 C: 26

Maternal age (mean±SD) I: 25.4 ± 9.9 C: 24.8 ± 4.7

|

Gestational age (mean±SD) C: 23.7 ± 6.5

|

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy biliary tract disease

|

Laparotomic cholecystectomy biliary tract disease |

|

Chang 2011

Retrospective cohort study (1997-2008)

Country: Taiwan |

I: 12 C: 8

Maternal age (mean±SD) I: 29.1 ± 4.8 C: 29.8 ± 5.8

|

Not reported |

Laparoscopic ovarian torsion

|

Laparotomic ovarian torsion |

|

Corneille 2010 (Sedaghat 2017)

Retrospective patient record study (January 1 1993- June 30 2007)

Country: USA |

I: 39

Maternal age (mean±SD) I: 26 ± 6

|

First trimester (n) LC: 9

Second trimester (n) LC: 25

Third trimester (n)

|

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in pregnant patients nonobstetric abdominal operation |

Laparotomic cholecystectomy in pregnant patients nonobstetric abdominal operation |

|

Cosenza 1999 (Sedaghat 2017)

Retrospective patient record study (January 1993- December 1997)

Country: USA |

I: 12 C: 20

Maternal age |

Not reported |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in pregnant patients with biliopancreatic gallstone disorders |

Laparotomic cholecystectomy in pregnant patients with biliopancreatic gallstone disorders |

|

Cox 2016 (Sedaghat 2017)

Retrospective patient record study (2005-2012)

Country: USA |

I: 606 C: 58

Maternal age (mean±SD)

C: 28.7 ± 9.8

|

Not reported |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for common general surgical problems in pregnancy (cholecystitis) |

Laparotomic cholecystectomy for common general surgical problems in pregnancy (cholecystitis) |

|

Curet 1996 (Sedaghat 2017)

Case control study (1990-1995)

Country: Mexico |

I: 16 (4 appendectomies and 12 cholecystectomies) C: 18 (7 appendectomies, 10 chole cystectomies, and 1 exploratory laparotomy)

Maternal age (mean) I: 23.8 C: 22.4

|

First trimester (n) I: 7

Second trimester (n) I: 9

|

Laparoscopic non gynecologic abdominal surgery |

Laparotomic non gynecologic abdominal surgery |

|

Davis 1995 (Sedaghat 2017)

retrospective patient record study (1986-1993)

Country: USA |

I: 3 C: 16

Maternal age |

Not reported |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in pregnant patients with symptomatic gallbladder disease (after conservative management) |

Laparotomic cholecystectomy in pregnant patients with symptomatic gallbladder disease (after conservative management) |

|

Glasgow 1997 (Sedaghat 2017)

retrospective patient record study (1980-1996)

Country: USA |

I: 14 C: 3

Maternal age

|

First trimester (n) I: 3 C: 0

Second trimester (n) I: 11 C: 2

Third trimester (n) I: 0 C: 1

|

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in pregnant patients with symptomatic gallstone disease |

Laparotomic cholecystectomy in pregnant patients with symptomatic gallstone disease |

|

Kuy 2009 (Sedaghat 2017)

retrospective patient record study (1999-2006) |

I: 8645 C: 1069

Maternal age (mean±SD) Total: 26.2 ± 5.6

|

Not reported |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in women with biliary disease and biliary pancreatitis

|

Laparotomic cholecystectomy in women with biliary disease and biliary pancreatitis

|

|

Patel Veverka 2002 (Sedaghat 2017)

retrospective patient record study (1995-april 1998)

Country: USA |

I: 8

Maternal age (n) I: 18 years: 1 20 years: 1 22 years: 2 30 years: 2 32 years: 1

C: 18 years: 1 28 years: 1

|

Gestational age I: 15.5 [9-19] C: 19.5 [6-27]

|

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy biliary tract disease |

Laparotomic cholecystectomy biliary tract disease |

|

Visser 2001 (Sedaghat 2017)

retrospective patient record study (2005-2012)

Country: USA |

I: 11 C: 2

Maternal age C: 19.5±0.5

|

Gestational age (mean ± SEM [range]) I: 17.0± 1.5 [6–31] C: 19.5±0.5 [19–20] |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for abdominal diseases during pregnancy (gallstone disease) |

Laparotomic cholecystectomy abdominal diseases during pregnancy (gallstone disease) |

Results

1. Maternal mortality

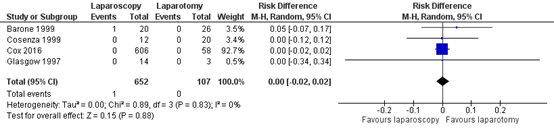

Four studies reported on the outcome maternal mortality in a total population of 759 patients on which a meta-analysis was performed (see figure 1; Barone 1999, Cosenza 1999, Cox 2016, Glasgow 1997). One of the 652 patients who underwent laparoscopy (0.15%) and zero of the 107 patients that underwent laparotomy (0.00%) were deceased (RD 0.00, 95%CI -0.02 to 0.02).

Figure 1. Maternal mortality, comparison laparoscopy versus laparotomy

2. Fetal mortality

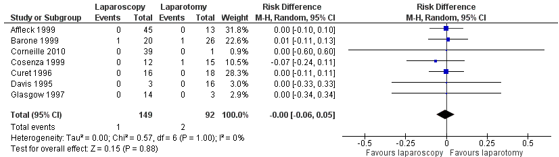

Seven studies reported on the outcome fetal mortality in a total population of 241 patients on which a meta-analysis was performed (see figure 2; Affleck 1999, Barone 1999, Corneille 2010, Cosenza 1999, Curet 1996, Davis 1995, Glasgow 1997). Of one of the 149 patients who underwent laparoscopy (0.67%) and of two of the 92 patients that underwent laparotomy (2.17%) fetal loss occurred (RD 0.00, 95%CI -0.06 to 0.05).

Figure 2. Fetal mortality, comparison laparoscopy versus laparotomy

3. Preterm delivery

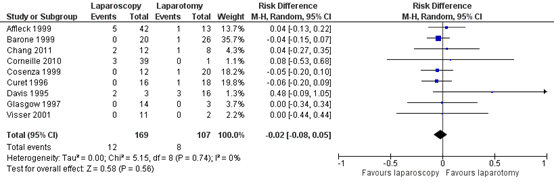

Nine studies reported on the outcome preterm birth (< 37 weeks gestation) in a total population of 276 patients on which a meta-analysis was performed (see figure 3; Affleck 1999, Barone 1999, Chang 2011, Corneille 2010, Cosenza 1999, Curet 1996, Davis 1995, Glasgow 1997, Visser 2001). Twelve of the 169 patients who underwent laparoscopy (7.10%) and eight of the 107 patients that underwent laparotomy (7.48%) delivered preterm (RD -0.02, 95%CI -0.08 to 0.05).

Figure 3. Preterm birth, comparison laparoscopy versus laparotomy

4. Serious maternal complications

Not reported.

5. Miscarriage

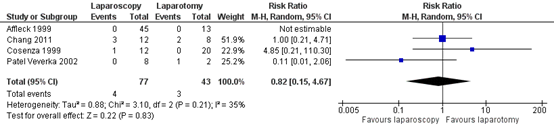

Four studies reported on the outcome miscarriage in a total population of 120 patients on which a meta-analysis was performed (see figure 4; Affleck 1999, Chang 2011, Cosenza 1999, Patel Veverka 2002). Four of the 77 patients who underwent laparoscopy (5.19%) and of three of the 43 patients that underwent laparotomy (6.98%) had a miscarriage (RR 0.82, 95%CI 0.15 to 4.67).

Figure 4. Miscarriage, comparison laparoscopy versus laparotomy

6. Surgical wound complications

Two studies reported on the outcome surgical wound complications. In Cox (2016) four of the 606 patients who underwent laparoscopy (0.07%) and two of the 58 patients that underwent laparotomy (3.45%) suffered from surgical wound complications (RR 0.19, 95% CI 0.04 to -1.02).

Kuy (2009) reported on the outcome surgical complication, as a collective outcome for several surgical-related complications including infections/wound complications. They reported that 873 of the 8645 patients who underwent laparoscopy (10.1%) and 202 of the 1069 patients that underwent laparotomy (18.9%) had such surgical complications (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.61).

7. Maternal pain

Not reported.

8. Length of hospital stay

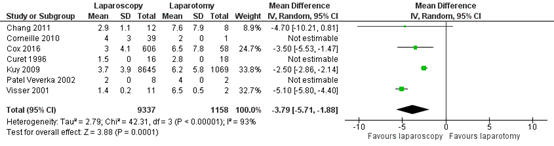

Seven studies reported on the outcome length of hospital stay in days. On four studies a meta-analysis could be performed (see figure 5; Chang 2011; Cox 2016; Kuy 2009; Visser 2001). The mean difference was -3.79 and 95%CI ranged -5.71 to -1.88. For three studies (Corneille 2010; Curet 1996; Patel Veverka 2002) the mean difference could not be calculated (standard deviation were not reported and for one study only one patient was included the control group), but they show a similar direction of effect as the studies in the meta-analysis (see Table 2).

Figure 5. Hospital stay, comparison laparoscopy versus laparotomy

Table 2. Length of hospital stay, comparison laparoscopy versus laparotomy

|

Study |

Laparoscopy |

Laparotomy |

Mean difference |

||||

|

Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

||

|

Corneille 2010 |

4 |

3 |

39 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

Curet 1996 |

1.5 |

0 |

16 |

2.8 |

0 |

18 |

-1.3 |

|

Patel Veverka 2002 |

2 |

0 |

8 |

4 |

0 |

2 |

-2 |

SD = standard deviation; N = number of patients

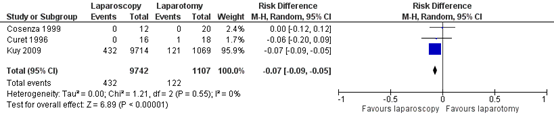

9. Fetal distress

Three studies reported on the outcome fetal distress in a total population of 10849 patients on which a meta-analysis was performed (see figure 6; Cosenza 1999; Curet 1996; Kuy 2009). The fetus of 432 of the 9742 patients who underwent laparoscopy (4.43%) and the fetus of 122 of the 1107 patients that underwent laparotomy (11.02%) showed signs of distress (RR -0.07, 95%CI -0.09 to -0.05).

Figure 6. Fetal distress, comparison laparoscopy versus laparotomy

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures started at low as the included studies were observational studies (retrospective study designs).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure maternal mortality was downgraded by two additional levels to very low because of study limitations (potential confounding not addressed, -1); and a very low number of events with a small sample size (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure fetal mortality was downgraded by two additional levels to very low because of study limitations (potential confounding not addressed, -1); and wide confidence intervals crossing the border of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure preterm delivery was downgraded by three additional levels to very low because of study limitations (potential confounding not addressed, -1); inconsistency of results (inconsistency, -1); and low number of events with a small sample size (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure maternal serious complications could not be assessed with GRADE as these outcome measures were not studied in the included studies.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure miscarriage was downgraded by three additional levels to very low because of study limitations (potential confounding not addressed, -1); inconsistency of results (inconsistency, -1); and low number of events with a small sample size (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure maternal surgical wound complications was downgraded by three additional levels to very low because of study limitations (potential confounding not addressed, -1); indirectness of results as the outcomes were combined measures for complications (indirectness, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure maternal pain could not be assessed with GRADE as these outcome measures were not studied in the included studies.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure length of hospital stay was downgraded by one additional level to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure fetal distress was downgraded by one additional level to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effect of laparoscopic surgery compared with open surgery for acute abdominal surgical indications in pregnant patients?

| P: | Pregnant patients undergoing acute abdominal surgery based on imaging (suspection) for any of the following diagnoses: cholecystitis, ovarian/parametrial torsion/hemorrhage, or internal herniation, or other causes of intestinal obstruction with or without strangulation or ischemia. |

| I: | laparoscopy |

| C: | laparotomy/open surgery |

| O: |

maternal mortality serious maternal complications (need for blood transfusion) miscarriage |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered maternal or fetal mortality, preterm delivery, miscarriage, and serious complications as critical outcome measures for decision making; and maternal surgical wound complications, maternal pain, length of hospital stay/ intensive care stay, and fetal distress as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measure serious complications as follows: need for blood transfusion. A priori, the working group did not define the other outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The guideline development group defined the following as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference:

| Fetal mortality: | a 5% difference relative risk was considered clinically relevant (0.95≥RR≥1.05) |

| Preterm delivery: | a 5% difference relative risk was considered clinically relevant (0.95≥RR≥1.05) |

| Miscarriage: | a 5% difference relative risk was considered clinically relevant (0.95≥RR≥1.05) |

| Serious complications (e.g., need for blood transfusion): | a 5% difference relative risk was considered clinically relevant (0.95≥RR≥1.05) |

| Maternal mortality: | a 5% difference relative risk was considered clinically relevant (0.95≥RR≥1.05) |

| Maternal surgical wound complications: | a 10% difference relative risk was considered clinically relevant (0.91≥RR≥1.10) |

| Maternal pain: | a difference of 10% of the maximum score was considered clinically relevant |

| Length of hospital stay/ intensive care stay: | a mean difference of≥1 day was considered clinically relevant |

| Fetal distress: | a 5% difference relative risk was considered clinically relevant (0.95≥RR≥1.05). |

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until December 03-12-2021 and an additional search was performed until 01-03-2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted 381 hits in the initial search plus 178 additional hits in the additional search (559 in total). Studies were selected based on the following criteria: Systematic review, randomized controlled trial or observational research comparing laparoscopy to laparotomy in pregnant women undergoing non obstetric surgery as defined above.

Twenty three studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full tekst nine studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included. Additional to the search strategy, two relevant guidelines were found (Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons [SAGES 2017]: Pearl, 2017; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [RCOG 2019]: Ball, 2019). The studies discussed in the RCOG guideline were included in the summary of literature as they met selection criteria.

Results

Two studies (one systematic review and one additional observational study) were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias (RoB) is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Ball E, Waters N, Cooper N, Talati C, Mallick R, Rabas S, Mukherjee A, Sri Ranjan Y, Thaha M, Doodia R, Keedwell R, Madhra M, Kuruba N, Malhas R, Gaughan E, Tompsett K, Gibson H, Wright H, Gnanachandran C, Hookaway T, Baker C, Murali K, Jurkovic D, Amso N, Clark J, Thangaratinam S, Chalhoub T, Kaloo P, Saridogan E. Evidence-Based Guideline on Laparoscopy in Pregnancy: Commissioned by the British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (BSGE) Endorsed by the Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists (RCOG). Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2019 Mar;11(1):5-25. Erratum in: Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2020 Jan 24;11(3):261. PMID: 31695854; PMCID: PMC6822954.

- Chang SD, Yen CF, Lo LM, Lee CL, Liang CC. Surgical intervention for maternal ovarian torsion in pregnancy. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec;50(4):458-62. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2011.10.010. PMID: 22212317.

- Pearl JP, Price RR, Tonkin AE, Richardson WS, Stefanidis D. SAGES guidelines for the use of laparoscopy during pregnancy. Surg Endosc. 2017 Oct;31(10):3767-3782. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5637-3. Epub 2017 Jun 22. PMID: 28643072.

- Rasmussen AS, Christiansen CF, Uldbjerg N, Nørgaard M. Obstetric and non-obstetric surgery during pregnancy: A 20-year Danish population-based prevalence study. BMJ Open. 2019 May 19;9(5):e028136. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028136. PMID: 31110105; PMCID: PMC6530408.

- Sedaghat N, Cao AM, Eslick GD, Cox MR. Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2017 Feb;31(2):673-679. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5019-2. Epub 2016 Jun 20. PMID: 27324332.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Affleck 1999 (Sedaghat 2017) |

Type of study: retrospective patient record study (1990-1998)

Setting and country: single centre (LDS hospital), USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: (1) all deliveries treated at LDS Hospital between 1990 and 1998; (2) patients who underwent open or laparoscopic appendectomy or cholecystectomy during pregnancy

Exclusion criteria: Not defined

N total at baseline: LC: 45 OC: 13

First trimester (n) LC: 3

Second trimester (n) LC: 28

Third trimester (n) LC: 11

Important prognostic factors2: n.a.

Groups comparable at baseline? Analyzed on an “intent to treat” basis, there were no statistical differences across the open and laparoscopic groups with respect to PTD, birth weights, or Apgar scores.

|

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC)

|

Open* cholecystectomy (OC) |

Length of follow-up: Not reported

Loss-to-follow-up: n.a.

Incomplete outcome data: LC: 2, record unavailable for analyses (and one twin pregnancy that was excluded for part of the analyses)

|

Fetal loss LA/LC: 0

Complications Uterine injuries (n) LA/LC: 0

Spontaneous abortion (n) LA/LC: 0

Preterm delivery (< 37 weeks gestation) in % (n) LC (N=42): 11.9% (5) OC: 10.0%

Early preterm delivery (< 35 weeks gestation) in % LA/LC: 4.9% OA/OC: 0%

Conversion to open (n) LC: 2

None of the laparoscopic to open conversions resulted in preterm delivery

|

Study objective: We reviewed our experience over 8 years with open and laparoscopic surgery during pregnancy to identify factors that might be associated with fetal loss, complications, and preterm delivery.

Both appendectomy and cholecystectomy. For some of the outcome measures, only combined data was available.

*Most of the open surgeries occurred during the first few years of the study

Intention to treat analyses

|

|

Barone 1999 (Sedaghat 2017) |

Type of study: retrospective patient record study (1992-1996)

Setting and country: multicentre (the Connecticut Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Registry and data from the Connecticut Hospital Association (CH), USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

N total at baseline (n) I: 20 C: 26

Important prognostic factors2:

Maternal age (mean±SD) I: 25.4 ± 9.9 C: 24.8 ± 4.7

Gestational age during procedure (mean±SD) C: 23.7 ± 6.5

Groups comparable at baseline? yes >patients underwent laparoscopic surgery at a mean of 5 weeks of gestation earlier than those who had open procedures (significant difference) >the serum alkaline phosphatase was significantly higher in the open group

|

laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

open cholecystectomy |

Length of follow-up: Not reported

Loss-to-follow-up: n.a.

Incomplete outcome data: Charts were not found on 13 occasions, and no response from the hospital was noted in 25 cases. |

Maternal mortality (n) Serious complications Macrosomia (n) Preeclampsia (n) Bradycardia (newborn) (n) Maternal dehydration (n) Fetal mortality (n) Preterm birth (n) Gestational age at birth (weeks) (mean±SD) Conversion to open (n) No laparoscopic procedure required conversion to open cholecystectomy. |

Study objective: to compare laparoscopic cholecystectomy with open cholecystectomy in pregnant patients over the same time period.

|

|

Chang 2011 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort study 1997 to 2008

Setting and country: Single center, Taiwan

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: Pregnant women with surgically proven ovarian torsion

Exclusion criteria: - N total at baseline: Intervention: 12 Control: 8

Important prognostic factors2: Age (mean, sd) I: 29.1 (4.8) C: 29.8 (5.8)

Groups comparable at baseline? patients who underwent laparoscopy had a significantly smaller ovarian mass and a shorter hospital stay than those undergoing laparotomy.

|

Laparoscopy

|

Laparotomy |

Length of follow-up: Not reported

Loss-to-follow-up: - Incomplete outcome data: -

|

Hospital stay (days) I: 2.9 (1.1) C: 7.6 (7.9)

Abortion à miscarriage I: 3/12 (1 missed abortion) C: 2/12

Preterm birth I:2/12 C:1/12

Significant complications I: 0 C: 0

|

Study objective: to review the clinical manifestations, and to compare the outcome between laparoscopy and laparotomy in women undergoing surgery for ovarian torsion (OT) during pregnancy

|

|

Corneille 2010 (Sedaghat 2017) |

Type of study: retrospective patient record study (January 1 1993- June 30 2007)

Setting and country: single centre (University Hospital Texas), USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

N total at baseline (n) Total: 94 LA: 9 OA: 40 OC: 1

First trimester (n) LA: 6 OA:19 OC: 0

Second trimester (n) LA: 3 OA: 12 OC: 0

Third trimester (n) OA: 9 OC: 1

Important prognostic factors2:

Maternal age (mean±SD) LA: 24 ± 8 OA: 26 ± 6 OC: 22

Gestational age during procedure (mean±SD) OA: 17 ± 9 OC: 36

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes >open procedures in the third trimester

|

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC), salpingectomy/cystectomy (LS/C)

|

Open cholecystectomy (OC) |

Length of follow-up: Not reported

Loss-to-follow-up: n.a.

Incomplete outcome data: |

Serious complications (n=54, 30 laproscopic and 24 open procedures)

pre-eclampsia/eclampsia (n) OC: 0

placental abruption (n) OC: 0

placenta previa (n) OC: 0

intrauterine growth delay (n) OC: 0

Oligohydramnios OC: 0

The overall perinatal complication rate, including the 4 instances of fetal loss, was 38.8% (21/54); 36.7% (11/30) for laparoscopic procedures and 41.7% (10/24) for open procedures

Fetal mortality (n) LC: 0 OC: 0

Preterm birth (n) (n=54, 30 laproscopic and 24 open procedures) LC: 3 OC: 0

Postoperative hospital stay (total population) LC: 4±3 OC: 2

Conversion to open procedure LC: 1

|

|

|

Cosenza 1999 (Sedaghat 2017) |

Type of study: retrospective patient record study (January 1993- December 1997)

Setting and country: single centre (University Hospital Texas), USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

N total at baseline (n) Total: 32

I: 12 C: 20 (including 7 patients who additionally had common bile duct exploration)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

open cholecystectomy |

Length of follow-up: Not reported

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: |

Maternal mortality: I: 0 C: 0

Fetal loss C: 1 of 15 (excluding patients who had common bile duct exploration)

Complications

Fetal decelerations à fetal distress C: 0

Vaginal bleeding/uterine contractions I: 1 C: 0

Spontaneous abortionà miscarriage C: 0

Preterm delivery I: 0 C: 1 (21 weeks)

Conversion: I: 2

No significant difference was established in term of pregnancy outcome related to gestational age at surgery. |

Study objective: to review our clinical experience with BPD during pregnancy to analyze the outcomes of that subgroup of patients requiring operation during pregnancy in an attempt to establish a safe management approach |

|

Cox 2016 (Sedaghat 2017) |

Type of study: retrospective patient record study (2005-2012)

Setting and country: multicentre (National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database), USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline (n)

LC: 606 OC: 58

Important prognostic factors2:

Age: LC: 28.3 ± 6.5 OC: 28.7 ± 9.8

BMI: LC: 31.4 ± 7.4 OC: 33.2 ± 9

Groups comparable at baseline? LC versus OC: patient characteristics were not different: age (28.3 vs. 28.7 years; p = 0.33), BMI (31.4 vs. 33.2 kg/m2 , p = 0.25), diabetes (2.8 vs. 3.5 %, p = 0.68), and smoking (21.1 vs. 25.9 %, p = 0.4). |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) |

Open cholecystectomy (OC) |

Follow-up 30 days post-surgery

Incomplete outcome data* No incomplete outcome data for reported outcome measures.

* No results could be identified for preterm labor or any fetal outcomes for either appendectomy or cholecystectomy from the database and therefore could not be analyzed.

|

30-day outcome measures:

Maternal mortality: LC: 0.0 % OC: 0.0 %

Serious complications (overall major complications) LC: 0.66 % OC: 1.7 %

Threatened preterm labor LC: not reported OC: not reported

Surgical wound complications LC: 0.66 % OC: 3.5 %

Hospital stay LC: 3 ± 4.1 OC: 6.5 ± 7.8

|

Study objective: to evaluate the impact of laparoscopy for common general surgical problems in pregnancy to determine safety and trends in operative approach over time

|

|

Curet 1996 (Sedaghat 2017) |

Type of study: case control

Setting and country: single centre, Mexico

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported

|

Inclusion criteria: non gynecologic abdominal surgery; first or second trimester (up to 28 weeks' gestation)

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: I: 16 (4 appendectomies and 12 cholecystectomies) C: 18 (7 appendectomies, 10 chole cystectomies, and 1 exploratory laparotomy)

Important prognostic factors2:

Age, y I: 23.8 C: 22.4

First trimester (n) I: 7

Second trimester (n) I: 9

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, The study and control groups were comparable for age, trimester, intraoperative oxygenation and end-tidal C02, gestational age at delivery, birth weight, and Apgar scores.

|

Laparoscopic non gynecologic abdominal surgery |

Open non gynecologic abdominal surgery |

Length of follow-up: 6 years (1990-1995)

Loss-to-follow-up:

Incomplete outcome data: 29 pregnant women underwent open surgery, but only 18 were in the first two trimesters of pregnancy à excluded for analyses

|

Serious complications Immediate complications There were no immediate perioperative complications in either group

Long term surgery-related complications (12 months) I: 1 (Trocar fascial hernia) C: 0

Delivery-related complications I: 5 (oligohydramnios (2 patients), tight nuchal cord, failure to progress, and macrosomia (meconium). C*: 4 (preterm labor, macrosomia, fetal distress (meconium), and pregnancy-induced hypertension.)

Fetal mortality All neonates were healthy at birth.

Preterm birth* C: 1

Fetal distress* C: 1

Pain Patients in the laparoscopic surgery group required less intramuscular narcotics to control pain (P<.001)

Hospital stay Patients in the laparoscopic surgery group were discharged from the hospital earlier (P<.001) than patients who underwent open surgery.

I: 1.5 days

Conversion to open: Three patients underwent operations that were begun laparoscopically but were con¬ verted to open laparotomy; these 3 patients were excluded from the analyses |

Study objective: To compare the safety and efficacy of laparoscopic surgery with that of open laparotomy in pregnant patients

|

|

Davis 1995 (Sedaghat 2017) |

Type of study: retrospective patient record study (1986-1993)

Setting and country: multicentre, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported

|

Inclusion criteria: Pregnant women who were hospitalize with gallbladder disease

Exclusion criteria: not reported

N total at baseline: N = 19 I: 3 C: 16

Trimesters of surgery (n 1/2/3) 4/10/5

Diagnosis (n): Acute cholecystis: 14 Gallstone pancreatitis : 2

Important prognostic factors2: n.a.

Groups comparable at baseline? n.a.

|

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (after conservative management) |

Open cholecystectomy (after conservative management) |

Length of follow-up: Not reported

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported |

Fetal mortality (n) I: 0 C: 0

Preterm birth (< 37 weeks) (n) I: 2 C: 3

|

|

|

Glasgow 1997 (Sedaghat 2017)

|

Type of study: retrospective patient record study (1980-1996)

Setting and country: single centre, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported

|

Inclusion criteria: all pregnant patients identified to have symptomatic gallstone disease during pregnancy at the University of California, San Francisco, from 1980 to 1996.

Exclusion criteria: not reported

Diagnoses: biliary colic with documented cholelithiasis, acute or chronic cholecystitis, and gallstone pancreatitis.

N total at baseline: N= 17 I: 14 C: 3

First trimester I: 3 C: 0

Second trimester I: 11 C: 2

Third trimester I: 0 C: 1

Important prognostic factors2: Not reported per comparison

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported per comparison

|

Cholecystectomy laparoscopic |

Cholecystectomy open |

Length of follow-up: Na.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported |

Maternal mortality I: not reported C: 0

Fetal mortality I: 0 C: 0

Preterm birth I: 1 C: 0

Hospital stay (days) mean I: 1.2 C: 6

Conversion to open I: 0 |

Study objective: to define the natural history of gallstone disease during pregnancy and evaluate the safety of LC during pregnancy

Patients were divided into two groups. The first group consisted of patients who were treated by conservative, nonoperative therapy. The second group consisted of patients who were treated by either open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy. à the latter group data for laparoscopic and open are given but not compared. |

|

Kuy 2009 (Sedaghat 2017)

|

Type of study: retrospective patient record study (1999-2006)

Setting and country: multicentre (Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project-Nationwide Inpatient Sample (HCUP-NIS) database, which is a stratified 20% sample of all inpatient admissions to nonfederal, acute care hospitals and maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality), USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported |

Inclusion criteria: women with biliary disease and biliary pancreatitis

Exclusion criteria: Not reported

N total at baseline:

Total n cholecystectomy (0,26*36929): 9714

I (89%): 8645 C: 1069

Important prognostic factors2:

Age mean (SD) Total: 26.2 (SD, 5.6)

Groups comparable at baseline? n.a. |

Cholecystectomy laparoscopic |

Cholecystectomy open |

Length of follow-up: Not reported.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported. |

Surgical complications (%) (general surgical complications including cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, hematologic/vascular, urologic, pulmonary, infections/wound, and other complications of surgery, combined with cholecystectomy-specific complications including bile duct injury, repair of bile ducts, repair of liver laceration, hemoperitoneum, ileus, and injury to abdominal organs or uterus) I: 10.1% (n=873)

Maternal complications (%) (hysterectomy, cesarean section, and dilation and curettage) I: 3.8% (n=329)

Fetal complications (%) Fetal complications included fetal loss (induced, spontaneous, or missed abortion; intrauterine death; and still birth), early or threatened labor, and fetal distress. I: 5.0% (n=432)

Mean length of stay (days) I: 6.2 days [SD, 5.8 days]

|

Study objective: population-based measurement of outcomes after cholecystectomy during pregnancy à part of the analyses focusses on comparison between laparoscopy versus open surgery

|

|

Patel Veverka 2002 (Sedaghat 2017) |

Type of study: retrospective patient record study (1995-april 1998)

Setting and country: single centre (Covenant —Harrison and Covenant—Cooper campuses, Saginaw, Michig), USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported

|

Inclusion criteria: Pregnant women who specifically underwent surgical treatment of their biliary disease (i.e., cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, gallstone pancreatitis, and biliary coli)

Exclusion criteria: Not reported.

N total at baseline: N=10 I: 8

Important prognostic factors2:

Age (n) I: 18 years: 1 20 years: 1 22 years: 2 30 years: 2 32 years: 1

C: 18 years: 1 28 years: 1

Gestation (n) I: 9 weeks: 1 10.5 weeks: 1 14 weeks: 1 16 weeks: 1 18 weeks: 2 19 weeks: 2

C: 6 weeks: 1 27 weeks: 1

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

Open cholecystectomy |

Length of follow-up: Not reported (until delivery?)

Loss-to-follow-up: C: 1

Incomplete outcome data: C: 1

|

Hospital stay (days) I: 2, 2, 4, 0, 1, 1, 2, 4 C: 5, 3

Spontaneous abortion à miscarriage C: 1 (14 weeks)

|

Study objective: to further evaluate the safety of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the pregnant patient.

|

|

Visser 2001 (Sedaghat 2017) |

Type of study: retrospective patient record study (2005-2012)

Setting and country: multicentre (urban academic medical center and a large affiliated community teaching hospital), USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported

|

Inclusion criteria: Pregnant patients requiring abdominal surgery

Exclusion criteria: Not reported

N total at baseline: I: 11 C: 2

Important prognostic factors2:

Gestational age (mean ± SEM [range]) I: 17.0± 1.5 [6–31] C: 19.5±0.5 [19–20]

Groups comparable at baseline? n.a. (not primary objective of this study)

|

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

Open cholecystectomy |

Length of follow-up: n.a.

Loss-to-follow-up: n.a.

Incomplete outcome data: n.a |

Preterm birth (n) I: 0 C: 0

Hospital stay (mean ± SEM) I: 1.4±0.2 C: 6.5±0.5

|

Study objective: to evaluate the safety and timing of abdominal surgery during pregnancy |

Risk of bias table for interventions studies

|

Author, year |

Selection of participants

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population?

|

Exposure

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?

|

Outcome of interest

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study?

|

Confounding-assessment

Can we be confident in the assessment of confounding factors?

|

Confounding-analysis

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these confounding variables?

|

Assessment of outcome

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome?

|

Follow up

Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? In particular, was outcome data complete or imputed?

|

Co-interventions

Were co-interventions similar between groups?

|

Overall Risk of bias

|

|

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Low, Some concerns, High |

|

|

Affleck, 1999 |

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patients who underwent open or laparoscopic appendectomy or cholecystectomy during pregnancy were selected and reviewed

|

Probably no

Reason: patient record study, authors analyzed data available in the records only and it is not clear whether all potential confounding factors were included.

|

Definitely no

Reason: patient record study in which all patients undergoing surgery were included

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study, however method of measurement of the outcomes is not stated

|

Probably yes

Reason: incomplete outcome data n = 5 |

Not reported |

Some concerns |

|

Barone, 1999 |

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study/ Connecticut Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Registry

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study/ Connecticut Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Registry

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study, in which authors selected patients from Connecticut Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Registry and CHIME database for cholecystectomuy patients who was also admitted for any pregnancy-related diagnosis during the interval of 18 months surrounding the gallbladder surgery.

|

Probably no

Reason: patient record study, authors analyzed data available in the records only and it is not clear whether all potential confounding factors were included

|

Definitely no

Reason: patient record study

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study, however method of measurement of the outcomes is not stated

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study. Loss to follow-up/incomplete outcome in 25 cases.

|

Not reported |

Some concerns |

|

Chang, 2011 |

Probably no

Reason: retrospective cohort study

|

Probably no

Reason: retrospective cohort study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study, in which authors selected records from patients with a surgical indication for ovarian torsion in pregnancy were selected |

Probably no

Reason: patient record study, authors analyzed data available in the records only regarding data regarding demographic information, symptoms and signs, surgical outcome and pathological findings were collected and it is not clear whether all potential confounding factors were included

|

Definitely no

Reason: retrospective cohort study

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study, however method of measurement of the outcomes is not stated

|

Probably yes

Reason: no missing data or incomplete outcome data was recorded

|

|

Some concerns |

|

Corneille, 2010 |

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study, in which authors selected records from patients requiring surgical treatment

|

Probably no

Reason: patient record study, authors analyzed data available in the records only and it is not clear whether all potential confounding factors were included

|

Definitely no

Reason: patient record study in which all patients undergoing surgery were included

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study, however method of measurement of the outcomes is not stated

|

Probably yes

Reason: no missing data or incomplete outcome data was recorded

|

|

Some concerns |

|

Cosenza, 1999 |

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study, in which authors selected records from patients requiring surgical treatment

|

Probably no

Reason: patient record study, authors analyzed data available in the records only and it is not clear whether all potential confounding factors were included

|

Definitely no

Reason: patient record study in which all patients undergoing surgery were included

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study, however method of measurement of the outcomes is not stated

|

Probably yes

Reason: no missing data or incomplete outcome data was recorded, but length of follow-up was not reported

|

Definitely no

Reason: C included patients who additionally had common bile duct exploration

|

Some concerns |

|

Cox, 2016 |

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study according to selection criteria

|

Definately no

Reason: patient record study, authors analyzed data available in the records only. Gestational age and trimester of pregnancy were missing in the registry. Moreover, it is not clear whether all other potential confounding factors were included The authors did perform multivariate regression analysis of surgical outcomes adjusting for age, body mass index, and comorbidities were perforemd |

Definitely no

Reason: patient record study in which all patients undergoing surgery were included

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study, however method of measurement of the outcomes is not stated

|

Definately yes

Reason: follow-up was 30 days

|

Not reported |

High |

|

Curet, 1996 |

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: I and C patients were matched on gestatational age (first and second trimester)

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study, however method of measurement of the outcomes is not stated

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Not reported |

Some concerns |

|

Davis, 1995

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Probably no

Reason: not reported |

Probably no

Reason: no description

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study, however method of measurement of the outcomes is not stated

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study

|

|

Some concerns |

|

Glasgow, 1997 |

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study |

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely no

Reason: comparison between laparoscopic vs open was not the primairy objective of this study

|

Definitely no

Reason: comparison between laparoscopic vs open was not the primairy objective of this study

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study, however method of measurement of the outcomes is not stated

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Not reported |

High |

|

Kuy, 2009 |

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study; the HCUPNIS database is the largest all-payer inpatient database in the United States, with records from approximately 8 million hospital stays each year.

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely no

Reason: comparison between laparoscopic vs open was not the primairy objective of this study

|

Definitely no

Reason: comparison between laparoscopic vs open was not the primairy objective of this study

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study, however method of measurement of the outcomes is not stated

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Not reported |

High |

|

Patel Veverka, 2002 |

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study; |

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely no

Reason: comparison between laparoscopic vs open was not the primairy objective of this study

|

Definitely no

Reason: patient record study in which all patients undergoing surgery were included

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study, however method of measurement of the outcomes is not stated

|

Probably yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Not reported |

High |

|

Visser, 2001 |

Probably yes

Reason: Intervention group and control drawn from same patient record system |

Probably yes

Reason: secure records

|

Definitely yes

Reason: patient record study

|

Definitely no

Reason: retrospective review of charts

|

Probably no

Reason: no description

|

Probably yes

Reason: retrospective review of charts

|

n.a.

Reason: retrospective review of charts

|

Probably no

Reason: |

High |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Al Samaraee A, Bhattacharya V. Challenges encountered in the management of gall stones induced pancreatitis in pregnancy. Int J Surg. 2019 Nov;71:72-78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.09.016. Epub 2019 Sep 20. PMID: 31546031. |

wrong design; wrong P |

|

Balinskaite V, Bottle A, Sodhi V, Rivers A, Bennett PR, Brett SJ, Aylin P. The Risk of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Following Nonobstetric Surgery During Pregnancy: Estimates From a Retrospective Cohort Study of 6.5 Million Pregnancies. Ann Surg. 2017 Aug;266(2):260-266. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001976. PMID: 27617856. |

wrong outcomes (did not report data on any of the outcomes of interest) |

|

Chen YH, Li PC, Yang YC, Wang JH, Lin SZ, Ding DC. Association of laparoscopy and laparotomy with adverse fetal outcomes: a retrospective population-based case-control study. Surg Endosc. 2021 Nov;35(11):6048-6054. Doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-08094-2. Epub 2020 Oct 13. PMID: 33048230. |

wrong outcomes |

|

Daykan Y, Bogin R, Sharvit M, Klein Z, Josephy D, Pomeranz M, Arbib N, Biron-Shental T, Schonman R. Adnexal Torsion during Pregnancy: Outcomes after Surgical Intervention-A Retrospective Case-Control Study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019 Jan;26(1):117-121. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.04.015. Epub 2018 Apr 24. PMID: 29702270. |

Does not meet the PICO criteria, wrong comparison. |

|

Didar H, Najafiarab H, Keyvanfar A, Hajikhani B, Ghotbi E, Kazemi SN. Adnexal torsion in pregnancy: A systematic review of case reports and case series. Am J Emerg Med. 2023 Mar;65:43-52. Doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2022.12.026. Epub 2022 Dec 22. PMID: 36584539. |

No comparison laparoscopic and open; they do report frequency of surgical procedures but no outcomes are compared between the procedures |

|

Erekson EA, Brousseau EC, Dick-Biascoechea MA, Ciarleglio MM, Lockwood CJ, Pettker CM. Maternal postoperative complications after nonobstetric antenatal surgery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012 Dec;25(12):2639-44. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.704445. Epub 2012 Jul 11. PMID: 22735069; PMCID: PMC3687346. |

wrong P (44% appendectomy) |

|

Fatum M, Rojansky N. Laparoscopic surgery during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2001 Jan;56(1):50-9. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200101000-00025. PMID: 11140864. |

Review case series |

|

Graham G, Baxi L, Tharakan T. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy during pregnancy: a case series and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1998 Sep;53(9):566-74. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199809000-00024. PMID: 9751939. |

wrong study design; no comparison |

|

Jackson H, Granger S, Price R, Rollins M, Earle D, Richardson W, Fanelli R. Diagnosis and laparoscopic treatment of surgical diseases during pregnancy: an evidence-based review. Surg Endosc. 2008 Sep;22(9):1917-27. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9989-6. Epub 2008 Jun 14. PMID: 18553201. |

wrong study design; no comparison |

|

Juhasz-Böss I, Solomayer E, Strik M, Raspé C. Abdominal surgery in pregnancy--an interdisciplinary challenge. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014 Jul 7;111(27-28):465-72. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0465. PMID: 25138726; PMCID: PMC4187409. |

wrong design (selective search) and comparison mainly focussed on appendicectomy |

|

Kocael, 2015Kocael PC, Simsek O, Saribeyoglu K, Pekmezci S, Goksoy E. Laparoscopic surgery in pregnant patients with acute abdomen. Ann Ital Chir. 2015 Mar-Apr;86(2):137-42. PMID: 25952362. |

Feasibility study laparoscopic surgery, not comparative research |

|

Lanzafame RJ. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy during pregnancy. Surgery. 1995 Oct;118(4):627-31; discussion 631-3. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80028-5. PMID: 7570315. |

wrong study design; no comparison |

|

Mazze RI, Källén B. Reproductive outcome after anesthesia and operation during pregnancy: a registry study of 5405 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989 Nov;161(5):1178-85. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90659-5. PMID: 2589435. |

wrong outcomes |

|

Nasioudis D, Tsilimigras D, Economopoulos KP. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy during pregnancy: A systematic review of 590 patients. Int J Surg. 2016 Mar;27:165-175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.01.070. Epub 2016 Jan 28. PMID: 26826612. |

no comparison |

|

Nezhat FR, Tazuke S, Nezhat CH, Seidman DS, Phillips DR, Nezhat CR. Laparoscopy during pregnancy: a literature review. JSLS. 1997 Jan-Mar;1(1):17-27. PMID: 9876642; PMCID: PMC3015223. |

Case sersies laparoscopy. Does not meet PICO criteria, wrong comparison. |

|

Paramanathan A, Walsh SZ, Zhou J, Chan S. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in pregnancy: An Australian retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2015 Jun;18:220-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.05.005. Epub 2015 May 9. PMID: 25968488. |

Non comparative research |

|

Reedy MB, Källén B, Kuehl TJ. Laparoscopy during pregnancy: a study of five fetal outcome parameters with use of the Swedish Health Registry. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Sep;177(3):673-9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70163-7. PMID: 9322641. |

wrong outcomes |

|

Reyes-Tineo R. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in pregnancy. Bol Asoc Med P R. 1997 Jan-Mar;89(1-3):9-11. PMID: 9168629. |

Wrong outcomes (age, pre and post operative course and outcome) |

|

Rizzo AG. Laparoscopic surgery in pregnancy: long-term follow-up. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2003 Feb;13(1):11-5. doi: 10.1089/109264203321235403. PMID: 12676015. |

Non comparative research |

|

Takeda A, Hayashi S, Imoto S, Sugiyama C, Nakamura H. Pregnancy outcomes after emergent laparoscopic surgery for acute adnexal disorders at less than 10 weeks of gestation. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014 May;40(5):1281-7. doi: 10.1111/jog.12332. Epub 2014 Apr 2. PMID: 24689554. |

Non comparative research |

|

Zou G, Xu P, Zhu L, Ding S, Zhang X. Comparison of subsequent pregnancy outcomes after surgery for adnexal masses performed in the first and second trimester of pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020 Mar;148(3):305-309. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13065. Epub 2019 Dec 11. PMID: 31758814. |

Does not meet the PICO criteria, wrong comparison (surgery for adnexal mass first versus second trimester). |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 09-09-2024

In onderstaande tabellen is de geldigheid te zien per richtlijnmodule. Tevens zijn de aandachtspunten vermeld die van belang zijn voor een herziening.

|

Module (richtlijn 2024) |

Geautoriseerd in |

Laatst beoordeeld in |

Geplande herbeoordeling |

Wijzigingen meest recente versie |

|

1, Operatietechniek (open vs. invasief) |

Datum volgt |

Datum volgt |

2029 |

Nieuwe module |

|

2, Foetale bewaking |

Datum volgt |

Datum volgt |

2029 |

Nieuwe module |

|

3, Aspiratieprofylaxe |

Datum volgt |

Datum volgt |

2029 |

Nieuwe module |

|

4, Anesthesietechniek (algehele anesthesie vs. locoregionale of neuraxiale anesthesie) |

Datum volgt |

Datum volgt |

2029 |

Nieuwe module |

|

5, Anesthesietechniek (sedatie vs. algeheel) |

Datum volgt |

Datum volgt |

2029 |

Nieuwe module |

|

6, Timing van de operatie |

Datum volgt |

Datum volgt |

2029 |

Nieuwe module |

|

7, Tocolytica |

Datum volgt |

Datum volgt |

2029 |

Nieuwe module |

|

8, Dexamethason |

Datum volgt |

Datum volgt |

2029 |

Nieuwe module |

|

9, Esketamine |

Datum volgt |

Datum volgt |

2029 |

Nieuwe module |

|

10 Vasopressoren |

Datum volgt |

Datum volgt |

2029 |

Nieuwe module |

|

11, Postoperatieve pijn |

Datum volgt |

Datum volgt |

2029 |

Nieuwe module |

|

12 Uteruscontracties |

Datum volgt |

Datum volgt |

2029 |

Nieuwe module |

|

13 Organisatie van zorg: Wie heeft de regie? Wie zit er in het MDO? |

Datum volgt |

Datum volgt |

2029 |

Nieuwe module |

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met postoperatieve pijn.

Werkgroep

dr. F.A. (Floris) Klerk, anesthesioloog (voorzitter), NVA

drs. R.P.M. (Renske) Aarts, anesthesioloog, NVA

dr. M. (Martine) Depmann, gynaecoloog, NVOG

drs. M. (Martijn) Groenendijk, intensivist, NVALT

drs. A.L.M.J. (Anouk) van der Knijff-van Dortmont, anesthesioloog, NVA

dr. R. (Robin) van der Lee, kinderarts-neonatoloog, NVK

drs. A.J. (Annefleur) Petri, anesthesioloog, NVA

drs. E.M.C. (Elizabeth) van der Stroom, anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist, NVA

Prof. dr. G.H. (Gabrielle) van Ramshorst, gastrointestinaal en oncologisch chirurg, NVvH

dr. K.C. (Karlijn) Vollebregt, gynaecoloog, NVOG

Klankbordgroep

I. (Ilse) van Ee, PFNL

P.S. (Pleun) van Egmond, ziekenhuisapotheker, NVZA

drs. I. (Ilse) van Stijn, NVIC

Met ondersteuning van

Dr. J.C. (José) Maas, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

Dr. L.M. (Lisette) van Leeuwen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten (vanaf oktober 2022)

Dr. L. (Laura) Viester, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten (t/m juli 2022)

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Klerk (voorzitter) |

* Anesthesioloog Diakonessenhuis Utrecht * Voorzitter Sectie Bestuur Obstetrische Anesthesiologie (NVA)" |

Werkgroeplid SKMS Fluxus

|

Geen

|

Geen actie

|

|

Aarts

|

Anesthesioloog te Bernhoven ziekenhuis Uden tot 01-03-2022.

Anesthesioloog te Maasstadzieken-huis Rotterdam van 01-04-2022 tot 01-01-2023.

Per 01-01-2023 Anesthesioloog te Rivas Beatrixziekenhuis Gorinchem. |

Aanpassing per 24-10-2023: Algemeen Bestuurslid Sectie Obstetrische Anesthesiologie van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Anesthesiologie (NVA) (onbetaald). |

Geen

|

Geen actie |

|

van der Knijff-van Dortmont |

Anesthesioloog, ErasmusMC, locatie Sophia, te Rotterdam |

* Bestuurslid en instructeur MOET, ALSG (onbetaald) Aanpassing per 19-10-2023: vervallen functies: * Vrijwilliger St. Elisabeth parochie, grafadministratie kern Dussen (onbetaald) * Lid oudercommissie kinderdagverblijf de Boei, Kober, Breda (onbetaald)

|

Aanpassing per 19-10-2023: vervallen belang: Lid NVA - organisator AIOS dag obstetrische anesthesie via NVA.

|

Geen actie

|

|

van der Stroom |

Anesthesioloog pijnspecialist, Alrijne Ziekenhuis |

Lid Benoemings Advies Commissie BAC Alrijne Ziekenhuis Per 1 oktober 2022: Medisch Manager afdeling Pijngeneeskunde Alrijne ziekenhuis

|

Geen

|

Geen actie |

|

Petri |

AIOS Anesthesiologie - Amsterdam UMC locatie VUmc tot 24-06-2022. Per 01-07-2022 Anesthesioloog in het Erasmus MC – Sophia Kinderziekenhuis. |

APLS instructeur Stichting SHK - vrijwilligersvergoeding. |

Geen

|

Geen actie |

|

van Ramshorst |

* UZ Gent - Kliniekhoofd 0,5 fte * Ugent - professor 0,5 fte" |

* Associate editor Colorectal Disease - onbetaald * Presentatie webinar Covid Surg, (maart 2021), betaald door Medtronic. Aanpassing per 15-11-2023: vervallen functie: * GGD Haaglanden medisch supervisor – betaald.

|

Geen

|

Geen actie |

|

Vollebregt |

Gynaecoloog in het Spaarne Gasthuis, lid van de Medische Specialisten Cooperatie Kennemerland |

Docent Amstelacademie bij de opleiding tot obstetrieverpleegkundige 8-12 uur per jaar, dit is betaald |

Geen

|

Geen actie |

|

Depmann |

Gynaecoloog Wilhelmina Kinderziekenhuis Utrecht. |

Lid werkgroep zwangerschapscholestase

Aanpassing per 23-10-2023: Schrijver richtlijn zwangerschapscholestase + richtlijn ursochol bij zwangerschapscholestase

|

Aanpassing per 23-10-2023: Extern gefinancieerd onderzoek: Fonds SGS, Achmea: Veiligheid en effectiviteit van orale antihypertensiva in de zwangerschap. Geen rol als projectleider. |

Geen actie |

|

van der Lee |

Kinderarts-neonatoloog, Amalia kinderziekenhuis Radboudumc, Nijmegen |

Aanpassing per 07-11-2023: Instructeur POCUS bij kinderen. Organisatie: DEUS. Betaald.

|

Geen

|

Geen actie |

|

Groenendijk |

Longarts-Intensivist Leiderdorp Alrijne ziekenhuis. |

Waarnemend Intensivist diverse ziekenhuizen in Nederland |

Geen

|

Geen actie |

|

Van Stijn |

Intensivist OLVG |

Lid raad van toezicht Qualicor, bezoldigd Lid raad van commissarissen ADRZ, bezoldigd |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Egmond |

Ziekenhuisapotheker, lsala |

Lid Commissie Onderwijs NVZA, onbetaald Lid SIG IC en Anesthesiologie NVZA, onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Ee |

Adviseur Patientenbelang, Patientenfederatie |

Vrijwilliger Psoriasispatienten Nederland - coordinator patientenparticipatie en onderzoek en redactie lid centrale redactie - onbetaalde werkzaamheden |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Maas |

Adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Leeuwen |

Adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Viester |

Adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door zitting van een afgevaardigde van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland in de klankbordgroep. De Patiëntenfederatie Nederland werd uitgenodigd voor de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie. Het overzicht van de reacties [zie bijlagen: ‘Knelpunteninventarisatie’] is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Operatietechniek (open vs. minimaal invasief) |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en zal daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor vrouwen die een niet-obstetrische operatieve ingreep moeten ondergaan. Er zijn knelpunten aangedragen door relevante partijen middels een invitational conference. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4.1 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).