Preventie van PICS

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van op de intensive care geïnitieerde farmacologische en niet-farmacologische interventies gericht op het voorkomen of reduceren van Post Intensive Care Syndroom (PICS)?

Aanbeveling

Zet geen farmacologische behandeling in specifiek ter voorkoming of reductie van Post Intensive Care Syndroom (PICS).

Bied IC-patiënten fysieke training aan, en in het bijzonder het (vroeg) mobiliseren.

Bied IC-patiënten (en de naasten; zie de module Preventie PICS-F) het gebruik van een IC-dagboek aan.

Gebruik geen oordoppen en oogmaskers om PICS-symptomen te voorkomen dan wel te verminderen.

Zet niet standaard psychologische ondersteuning in op de IC ter voorkoming van PICS. Bij preexistente psychologische factoren of (bij PICS passende) symptomen die zich tijdens de IC-opname manifesteren, kan de inzet van psychologische ondersteuning wel overwogen worden.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In deze module zijn twee zoekvragen geformuleerd om te bepalen welke medicamenteuze en of niet-medicamenteuze interventies effectief zijn om PICS-symptomen te voorkomen of te verminderen. Bij deze vragen zijn loopafstand, geheugen en angst op de lange termijn als cruciale uitkomstmaten en depressie, PTSD, terugkeer naar werk en kwaliteit van leven op de lange termijn als belangrijke uitkomstmaten gedefinieerd door de werkgroep. De uitkomstmaten omvatten dus respectievelijk het fysieke, cognitieve en het mentale domein aangevuld met terugkeer naar werk en kwaliteit van leven.

Concluderend na uitvoerige bestudering van de beschikbare internationale wetenschappelijke literatuur is vastgesteld dat bewijs voor concrete evidence based aanbevelingen ten faveure van één of meerdere interventies ontbreekt. Er zijn echter wel overwegingen te formuleren bij de verschillende interventies.

Zoekvraag 1: Medicamenteuze interventies

Slechts één studie voldeed aan de in- en exclusiecriteria van de literatuursearch. Rosuvastatin zou mogelijk geen effect hebben op geheugen (lage bewijskracht). Er zijn geen studies gevonden waarin de overige uitkomstmaten zijn bestudeerd. De overall bewijskracht komt daarmee op zeer laag. Er ligt hier op gebied van medicamenteuze interventies een duidelijke kennislacune. Opgemerkt moet worden dat de search mogelijk onvoldoende sensitief is geweest om alle mogelijke studies te vinden.

Zoekvraag 2: niet medicamenteuze interventies

Voor deze zoekvraag zijn 13 studies geïncludeerd (waarvan negen eveneens werden geïncludeerd in de systematic review van Geense, 2019). Zes studies hebben het effect van fysieke training onderzocht, drie studies het effect van dagboeken, één studie het effect van counseling, twee studies het effect van informatie en scholing en één studie heeft het effect van de optimalisatie van de IC-omgeving (oordopjes en oogmaskers) onderzocht. Hieronder worden de overwegingen gegeven per type interventie.

Fysieke training

Het is (nog) onduidelijk of fysieke training geïnitieerd op de IC ten opzichte van standaard zorg, effect heeft op loopafstand, geheugen, angst en depressie. Studies naar fysieke training laten weinig effect zien op de kwaliteit van leven van patiënten bij follow-up na 3 maanden. Er zijn geen studies gevonden die de uitkomstmaten ‘posttraumatic stress disorder’ (PTSD) en terugkeer naar werk hebben onderzocht. De overall bewijskracht is zeer laag, hier ligt een kennislacune.

Er is op dit moment (nog) onvoldoende bewijs voor preventief effect van fysieke training ten opzichte van standaard zorg tijdens de IC-opname op PICS. Hierbij moet opgemerkt worden dat binnen de standaard zorg ook vaak fysieke training werd gegeven. Dit zal het contrast tussen de studiearmen waarschijnlijk hebben verkleind. De werkgroep is daarom van mening dat de resultaten vooral laten zien dat er niet één specifieke vorm van fysieke training kan worden aangeraden, en niet dat er geen meerwaarde is van fysieke training ten opzichte van helemaal geen training. Het is ook duidelijk dat bij kritiek zieke patiënten die inactief zijn, de inactiviteit leidt tot verminderde spierkracht en conditie (Mendez-Tellez, 2012). Vanuit verschillende patiëntenpopulaties is verder bekend dat fysieke training de spierkracht en het uithoudingsvermogen verbetert. Mobiliseren, en in het bijzonder geldt dit voor vroegmobilisatie (hetgeen als belangrijk onderdeel van fysieke training wordt gezien), vormt heden ten dage een standaard onderdeel van goede kwaliteit van IC-zorg. Ondanks dat er (nog) geen gunstige effecten van fysieke training in vergelijking met standaard zorg (wat ook fysieke training kon inhouden) ter preventie of reductie van PICS zijn gevonden en omdat er (nog) geen nadelige effecten van fysieke training zijn gevonden in studies, is de werkgroep van mening dat dit de huidige werkwijze, is de werkgroep van mening dat dit de huidige werkwijze, waarin fysieke training tijdens IC-opname als standaardzorg wordt beschouwd, niet mag veranderen.

IC-dagboek

Er zijn drie studies gevonden die het effect van het IC-dagboek hebben onderzocht bij IC-patiënten. De studiekwaliteit varieerde sterk. Waarschijnlijk hebben IC-dagboeken geen klinisch relevant effect op angst, depressie en PTSD bij IC-patiënt na ontslag uit het ziekenhuis (GRADE redelijk). Het effect op kwaliteit van leven is onduidelijk (GRADE zeer laag), en het effect op loopafstand, geheugen en terugkeer naar werk is niet onderzocht. Hierbij moet opgemerkt worden dat een effect op loopafstand ook niet direct voor de hand lijkt te liggen. Belangrijk is ook om op te merken dat, al was het niet gekozen als uitkomstmaat, bij geen van de studies is de patiënttevredenheid meegenomen. Het is belangrijk dat toekomstig onderzoek ook deze uitkomstmaat meeneemt.

Ondanks bovenstaande, is de ervaring van de werkgroepleden (voornamelijk gebaseerd op patiëntverhalen bij de IC-nazorgpoli’s en reacties tijdens lotgenoten contactbijeenkomsten van voormalig IC-patiënten en hun naasten) dat de dagboeken in het algemeen positief worden gewaardeerd door zowel de voormalig IC-patiënten als hun naasten. Niet iedere patiënt of nabestaande geeft aan behoefte te hebben aan een dagboek, maar het niet aanbieden van het (bijhouden van een) dagboek kan in de praktijk achteraf als een gemiste kans worden ervaren. Het gebruik van een IC-dagboek lijkt tijdens de IC-opname bij te kunnen dragen aan het verwerken en omgaan met stress bij de naasten, en na de IC-opname ‘aan het vullen van de leegte in het geheugen van de patiënt’ dat is ontstaan tijdens de IC-periode. Daarnaast draagt het mogelijk bij aan het aangaan van het gesprek over de IC-opname met elkaar, tussen naasten onderling, maar ook met zorgverleners.

Begeleiding/ondersteuning

Er is slechts één studie gevonden. Hieruit blijkt dat counseling tijdens de IC-opname waarschijnlijk geen klinisch relevant effect heeft op angst, depressie, PTSD en kwaliteit van leven bij IC-patiënten na ontslag uit het ziekenhuis (GRADE redelijk). Voor de andere uitkomstmaten loopafstand, geheugen en terugkeer naar werk zijn geen data beschikbaar.

Deze resultaten sluiten niet uit dat er individuele casuïstiek (bijvoorbeeld bij preexistente psychologische factoren) is waarbij de inzet van een psycholoog tijdens de IC-opname is geïndiceerd.

Informatie en scholing

Er zijn twee studies gevonden, maar het effect van dit type interventie op de uitkomsten angst, depressie en PTSD blijft grotendeels onduidelijk. Er lijkt geen effect te zijn op kwaliteit van leven na ontslag uit het ziekenhuis (GRADE laag). Deze bevindingen moeten echter slechts gezien worden in het perspectief van preventie en reductie van PICS. Het betekent niet dat het geven van informatie aan patiënten tijdens, reeds voorafgaand aan een IC-opname of vóór een bepaalde (be-)handeling, niet zinvol is. Het goed informeren van de patiënt voorafgaand aan de (be-) handeling en na de behandeling is een standaard onderdeel van goed zorgverlenerschap (zie ook module Organisatie van zorg – submodule ‘Informatievoorziening aan en communicatie met de patiënt en naasten’). Uiteraard maakt een ongeplande, acute opname voorlichting voorafgaand aan de IC-opname in veel gevallen onmogelijk.

Optimaliseren van de IC-omgeving

In één studie is het gebruik van oordoppen en een oogmasker onderzocht, maar het blijft onduidelijk of het gebruik van deze materialen effect heeft op angst, depressie en PTSD (GRADE zeer laag). Voor de overige uitkomstmaten zijn geen studies gevonden. Er is hierbij sprake van een kennislacune. Het kortetermijneffect van toepassingen van oordoppen op slaap, angst en delier is hier verder niet onderzocht. Er kan aan de individuele patiënt op basis van klinische inschatting altijd oordoppen worden aangeboden. Bij gebruik van oordoppen en oogmaskers bestaat echter ook een risico dat de patiënt teveel gedepriveerd kan raken van prikkels uit de omgeving.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en hun naasten)

Er is op dit moment nog weinig onderzoek gedaan naar de patiënttevredenheid en de patiëntvoorkeuren met betrekking tot de preventieve interventies voor PICS (Geense, 2019). Patiënten hechten eraan om na de IC-opname het ‘normale leven’ weer zo snel mogelijk op te kunnen pakken. Het voorkomen of verminderen van PICS-symptomen draagt hier waarschijnlijk aan bij, en heeft waarschijnlijk een gunstig effect op het herstel na de intensive care opname. De beschreven interventies ([vroeg] mobiliseren, bijhouden van dagboeken, informatievoorziening) zijn onderdeel van het geven van goede IC-zorg, en kennen een lage of beperkte belasting voor de patiënt. Over het algemeen zijn de meeste patiënten positief over fysieke training en is er een substantiële groep die de inzet van dagboeken nuttig vindt. Een goede informatievoorziening is daarnaast essentieel. Patiënten zullen over het algemeen het niet uitvoeren van deze interventies dan ook als nadelig ervaren.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Zoals hierboven beschreven zijn de onderzochte interventies (fysieke training, mobiliseren, dagboeken en informeren) al standaard onderdeel van de goede zorg en behandeling op de IC-afdeling en zullen daardoor als zodanig niet leiden tot extra kosten.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De werkgroep stelt dat fysieke training tijdens de IC en het gebruik van een IC-dagboek zowel aanvaardbaar als haalbaar zijn omdat dit al gangbare interventies zijn en gezien wordt als standaard zorg. Deze interventies dragen bij aan betere kwaliteit van zorg.

De implementatiegraad van beide interventies is hoog in de Nederlandse IC’s, zo wordt het gebruik van IC-dagboeken in bijna 90% van de IC’s toegepast (Hendriks, 2019). Fysieke training en mobiliseren kent mogelijkerwijs een nog hogere toepassingsgraad dan van de IC-dagboeken. Meestal is bij de fysieke training en (vroeg)mobilisatie een fysiotherapeut betrokken.

Ook het geven van informatie aan patiënten en naasten over onderzoeken en behandelingen zijn standaard onderdeel van goede IC-zorg. De werkgroep is van mening dat het onthouden van fysieke training, mobiliseren, het aanbieden (en bijhouden) van een IC-dagboek en het informeren van de patiënt onaanvaardbaar is omdat het leidt tot vermindering van de kwaliteit van zorg.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Medicamenteuze interventies

Er is weinig literatuur gevonden, derhalve raadt de werkgroep een farmacologische behandeling specifiek ter voorkoming of vermindering van de PICS-symptomen niet aan.

Niet-medicamenteuze interventies

Ondanks dat bewijs voor concrete evidence based aanbevelingen ten faveure van één of meerdere interventies ontbreekt, is de werkgroep van mening dat fysieke training (inclusief (vroeg) mobiliseren, zie ook Behandelprotocol Fysiotherapie op de IC (KNGF, 2021)) en het gebruik van een IC-dagboek aangeboden moet worden. Beide worden beschouwd als onderdeel van goede IC-zorg, en is op de meeste IC’s reeds geïmplementeerd.

Er is geen evidentie voor de inzet van oordoppen en oogmaskers en standaard psychologische ondersteuning ter voorkomen van PICS. De werkgroep raadt derhalve deze interventies niet standaard aan. De werkgroep hecht eraan dat de patiënten en de naasten goed geïnformeerd worden, ook als dit niet direct van invloed lijkt te zijn op het voorkomen van PICS. In de module ‘Organisatie van zorg – submodule ‘Informatievoorziening aan en communicatie met de patiënt en naasten’ worden specifieke aanbevelingen gedaan over dit onderwerp.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Ernstig zieke patiënten die op de intensive care (IC) zijn behandeld kunnen het Post Intensive Care Syndroom (PICS) ontwikkelen. PICS is gedefinieerd als nieuwe of verergerende problemen in het lichamelijke, mentale en/of cognitieve domein, ontstaan na het doormaken van een kritieke, ernstige ziekte en die blijven bestaan na verblijf op een IC afdeling (Needham, 2012). PICS komt regelmatig voor bij voormalig IC-patiënten, maar het is onduidelijk welke preventieve interventies effectief zijn. Onder de preventieve interventies[1] voor PICS worden hier alle interventies bedoeld die ingezet worden tijdens de IC-opname, om langetermijn klachten te voorkomen of te verminderen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Search question 1: pharmacological interventions versus no treatment or placebo

1, 3-7. Walking distance (critical), anxiety (critical), depression (important), PTSD (important), return to work (important) and quality of life (important)

|

- GRADE |

The effect of pharmacological interventions in the intensive care unit on walking distance, anxiety, depression, PTSD, return to work and quality of life is unknown. No studies were found examining these outcome measures in adult patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit. |

2. Cognitive functioning (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that treatment with rosuvastatin in the intensive care unit results in little to no difference in cognitive functioning in adult patients at six months after discharge.

Source: Needham, 2016 |

Search question 2: non-pharmacological interventions versus no treatment or usual care

1. Physical training

1. Walking distance (critical)

2-6. Cognitive functioning (critical), PTSD (important), return to work (important)

3-4. Anxiety (critical), depression (important)

7. Quality of life (important)

2. Diaries

1-2, 6. Walking distance (critical), cognitive functioning (critical), return to work (important)

|

- GRADE |

The effect of the use of diaries in the intensive care unit on walking distance, cognitive functioning and return to work is unknown. No studies were found examining these outcome measures in adult patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit. |

3. Anxiety (critical)

4. Depression (important)

5. PTSD

7. Quality of life

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of diaries in the intensive care unit on quality of life in adult patients after hospital discharge.

Source: Nielsen, 2020 |

3. Psychological counseling

1-2, 6. Walking distance (critical), cognitive functioning (critical) and return to work (important)

|

- GRADE |

The effect of psychological counseling in the intensive care unit on walking distance, cognitive functioning and return to work is unknown. No studies were found examining these outcome measures in adult patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit. |

3. Anxiety (critical)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Psychological counseling in the intensive care unit probably results in little to no difference in anxiety in adult patients after hospital discharge.

Source: Wade, 2019 |

4. Depression (important)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Psychological counseling in the intensive care unit probably results in little to no difference in depression in adult patients after hospital discharge.

Source: Wade, 2019 |

5. PTSD (important)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Psychological counseling in the intensive care unit probably results in little to no difference in PTSD in adult patients after hospital discharge.

Source: Wade, 2019 |

7. Quality of life (important)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Psychological counseling in the intensive care unit probably results in little to no difference in quality of life in adult patients after hospital discharge.

Source: Wade, 2019 |

4. Information and education

1-2, 5-6. Walking distance (critical), cognitive functioning (critical), PTSD (important) and return to work (important)

|

- GRADE |

The effect of information and education interventions in the intensive care unit on walking distance, cognitive functioning, PTSD and return to work is unknown. No studies were found examining these outcome measures in adult patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit. |

3. Anxiety (critical)

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effects of information and education interventions in the intensive care unit on anxiety in adult patients after hospital discharge.

Source: Demircelik, 2016 |

4. Depression (important)

7. Quality of life (important)

5. Optimizing the ICU environment

1-2, 6-7. Walking distance (critical), cognitive functioning (critical), return to work (important) and quality of life (important)

|

- GRADE |

The effect of the use of earplugs and eye masks in the intensive care unit on walking distance, cognitive functioning, return to work and quality of life is unknown. No studies were found examining these outcome measures in adult patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit. |

3. Anxiety (critical)

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of earplugs and eye masks in the intensive care unit on anxiety in adult patients after hospital discharge.

Source: Demoule, 2017 |

4. Depression (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of earplugs and eye masks in the intensive care unit on depression in adult patients after hospital discharge.

Source: Demoule, 2017 |

5. PTSD (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of earplugs and eye masks in the intensive care unit on PTSD in adult patients after hospital discharge.

Source: Demoule, 2017 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Search question 1: pharmacological interventions versus no treatment or placebo

One study was found that matched the search question. This study compared treatment with rosuvastatin versus placebo in patients with sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in intensive care (Needham, 2016).

Description of studies

Needham (2016) performed an ancillary study within a larger trial in which 37 hospitals in the United States participated. Administration of rosuvastatin was compared with a placebo in patients with sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. The intervention group received a 40 mg loading dose and then 20 mg daily until the earliest of death, three days after discharge from the ICU, or 28 days of study participation. At first delirium and cognition were only assessed at 12 hospitals, but as new data indicated that use of statins was associated with reduced odds of delirium, the study protocol was amended and delirium and cognition subsequently assessed in 35 hospitals. The first 75 patients were also included in another RCT comparing initial trophic with full enteral feeding. Because of ineffectiveness, the trial was stopped early. The intervention group consisted of 164 patients and the control group of 165 patients. Attention and working memory were assessed with the Digit Span age-adjusted scaled score from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (third edition). Immediate and delayed memory were assessed with the Logical Memory I and II age adjusted scaled scores. At six months follow-up, these outcomes were available for 53 patients in the rosuvastatin group and 77 patients in the placebo group. Outcomes were also assessed at 12 months, but the results were not reported in detail.

Results

1. Walking distance (critical), 3. Anxiety (critical), 4. Depression (important), 5. PTSD (important), 6. Return to work (important) and 7. Quality of life (important)

Needham (2016) did not report these outcome measures.

2. Cognitive functioning (critical)

Needham (2016) found no statistically significant differences on attention and working memory (intervention group, mean (SD): 9.2 (2.5); control group, mean (SD): 9.5 (2.6) ; β (95% CI): -0.3 (-1.2 to 0.6), p = 0.49) and immediate memory (intervention group, mean (SD): 8.6 (3.4); control group, mean (SD): 8.9 (3.3); β (95% CI): -0.4 (-1.5 to 0.7), p = 0.49). The difference in delayed memory was statistically significant (intervention group, mean (SD): 7.9 (3.3); control group, mean (SD): 8.8 (2.7); β (95% CI): -1.2 (-2.2 to -0.2), p = 0.02), with worse scores for the patients who received rosuvastatin. This difference was likely not clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures walking distance, anxiety, depression, PTSD, return to work and quality of life could not be assessed; no studies were found investigating these outcome measures.

RCTs start at high GRADE. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cognitive functioning was downgraded by 2 levels because of the substantial attrition (risk of bias; -1); and the inclusion of only one study with a limited sample size (imprecision; -1). The level of evidence is low.

The review of Geense (2019) was used as starting point for the second search question. This systematic review described non-pharmacological interventions aimed at the prevention of PICS. The databases PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Embase and Cochrane Library were searched until 19th July 2018. The risk of bias (ROB) of the individual studies was assessed with the Cochrane Collaboration’s ROB tool.

Nine of 36 studies from this review matched the PICO and our inclusion and exclusion criteria. We excluded two non-RCTs, three RCTs with an intervention which was started before ICU admission, 13 RCTs with interventions that started after ICU discharge, one RCT with an intervention that didn’t match our PICO, one RCT in which the control group received another intervention instead of no treatment or usual care, one RCT with outcome measures that didn’t match our PICO and six studies with less than twenty patients per study arm.

Our literature search resulted in four additional studies that answer the second PICO. Thus, 13 studies were included in total. Of these studies, six RCTs investigated the effect of physical training (Denehy, 2013; Eggmann, 2018; Hodgson, 2016; Morris, 2016; Schaller, 2016 and Wright, 2018). Three studies investigated the effect of diaries (Jones, 2010; Garrouste-Orgeas, 2019 and Nielsen, 2020). One study focused on psychological counseling (Wade, 2019), two studies on information and education (Demircelik, 2016 and Fleischer, 2014) and one study on optimizing the ICU environment by using earplugs and eye masks (Demoule, 2017).

No studies were found that investigated cognitive training, communication tools or behaviour of health care providers.

1. Physical training

Description of studies

The review of Geense (2019) included five studies that examined the effect of physical training and met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Denehy, 2013; Hodgson, 2016; Morris, 2016; Schaller, 2016 and Wright, 2018). The literature search revealed one additional study (Eggmann, 2018).

Studies included in Geense (2019)

Denehy (2013) investigated a rehabilitation program which was commenced at day five after ICU admission (<15 min/day), progressing daily on the acute hospital ward (2x 30 min) and being administered twice weekly for eight weeks in the outpatient setting (60 min). The intervention was performed by physiotherapists and consisted of marching in place, moving from sitting to standing, cardiovascular progressive resistance strength training and functional exercise. The control group received usual care, which may have included active bed exercises, sitting out of bed and marching/walking. The intervention group consisted of 74 patients and the control group of 76 patients. Walking distance was measured with the 6-minute walk test and quality of life was determined with the SF-36.

Hodgson (2016) evaluated the effects of exercise active functional activities, (e.g. walking, standing, sitting) during ICU admission. Intervention duration was 30 to 60 min per day, depending on patient level. The goal of the intervention was to maximize safe physical activity. The intervention group consisted of 29 patients and the control group of 21 patients. Quality of life was determined with the EQ-5D VAS and EQ-5D Utility, anxiety and depression with the HADS.

Morris (2016) investigated the effect of standardized rehabilitation therapy. This program consisted of three separate sessions per day. The team comprised a physical therapist, an ICU nurse, and a nursing assistant. Components of the intervention were passive range of motion (which included five repetitions for each upper and lower extremity joint), physical therapy (which included bed mobility, transfer training, and balance training), and progressive resistance exercises (which included dorsiflexion, knee flexion and extension, hip flexion, elbow flexion and extension, and shoulder flexion). The control group received usual care. Physical therapy could be ordered as part of usual care, but only Monday through Friday. Both the intervention group and the control group consisted of 150 patients. Quality of life was determined with the SF-36.

Schaller (2016) examined daily early, goal-directed mobilization in the ICU. The intervention consisted of two parts. First, a mobilization goal was defined during daily morning ward rounds and second, goal implementation across shifts was facilitated by inter-professional closed-loop communication. The control group received usual care. There were 104 patients in the intervention group and 96 in the control group. Quality of life was determined with SF-36.

Wright (2018) investigated intensive physical rehabilitation therapy which was provided by a physical therapist for 90 minutes per day on weekdays (Monday - Friday), split between at least two sessions. The physical rehabilitation therapy included functional training and individually tailored exercise programs. The control group received physical rehabilitation for 30 minutes per day. The physical rehabilitation therapy received by the standard care group was the same as that provided normally in participating ICUs. There were 150 patients in the intervention group and 158 patients in the control group. Walking distance was measured with the 6-minute walk test and quality of life was determined with the SF-36 and EQ-5D.

Studies published after Geense (2019)

Eggmann (2018) published a RCT in which early, progressive endurance and resistance training combined with mobilization was compared to standard physiotherapy with early mobilization. All patients received mechanical ventilation and both groups also received standard ICU care with protocol-guided sedation, weaning and nutrition. The intervention group consisted of 58 ICU patients, the control group consisted of 57 patients. Quality of life was determined with the SF-36.

Results for interventions with physical training

1. Walking distance (critical)

Hodgson (2016), Morris (2016), Schaller (2016) and Eggmann (2018) did not report this outcome measure.

Denehy (2013) and Wright (2018) administered the 6-minute walk test at three and six months after discharge. Data could not be pooled, since Denehy (2013) reported means with standard deviations, while Wright (2018) reported medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Results are provided separately for short term and long term effects.

6-minute walk test short term (three months)

At three months after discharge no clinically relevant and statistically significant differences were reported by either Denehy (2013) or Wright (2018). In Denehy (2013) the intervention group had a mean (SD) walking distance of 244.2 (124.0) meters at hospital discharge and 384.5 (147.9) meters at three months after discharge. The control group had a mean (SD) walking distance of 266.7 (136.8) meters at hospital discharge and 382.1 (139.4) meters at three months after discharge. The mean difference (95% CI) was 2.40 (-60.57 to 65.37) meters (calculated using RevMan version 5.3).

In Wright (2018) the intervention group had a median (IQR) walking distance of 195 (120-260) meters at hospital discharge and 293 (124-444) meters at three months follow-up. The control group had median (IQR) walking distance of 173 (123-274) meters at hospital discharge and 255 (120-337) meters at three months follow-up. In a multiple linear regression model with stratification variables and baseline variables the adjusted difference in means (95% CI) was −6.3 (−125.8 to 107.3) meters.

6-minute walk test long term (six months)

At six months after discharge no clinically relevant and statistically significant differences were found on this outcome measure by Denehy (2013). The intervention group had a mean (SD) walking distance of 394.2 (156.2) meters and the control group 402.4 (166.6) meters. The mean difference (95% CI) was -8.20 (-79.17 to 62.77) meters (calculated using RevMan version 5.3).

Wright (2018) did not find a statistically significant difference in walking distance at six months after discharge. The intervention group had a median (IQR) walking distance of 374 (203-435) meters and the control group of 321 (197-400) meters. The adjusted difference in means (95% CI) was 61.7 (−47.2 to 157.0). The difference seems clinically relevant, but given the broad interval this should be interpreted with caution.

2. Cognitive functioning (critical), 5. PTSD (important), 6. return to work (important)

These outcome measures were not reported in the included studies about physical training.

3. Anxiety (critical)

Hodgson (2016) reported the total scores of the HADS, the summed anxiety and depression score, at six months follow-up. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups (mean (SD) intervention group 11.6 (9.1); control group: 11.3 (7.1), p=0.91). The difference is likely also not clinically relevant.

This outcome measure was not reported in the other included studies.

4. Depression (important)

See Anxiety.

7. Quality of life (important) – short-term

Various outcome measures were used to assess quality of life. The results are presented separately for the overall quality of life scales (EQ-5D and SF-36 total score), the SF-36 PCS and the SF-36 MCS.

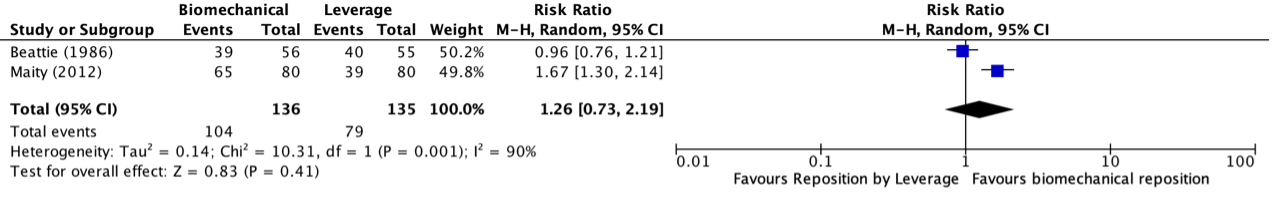

Morris (2016) and Wright (2018) reported the SF-36 PCS at two months and Denehy (2013) at three months follow-up. The results are pooled. Physical training did not result in clinically relevant and not statistically significant between-group differences (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Short term effects of physical training on SF-36 PCS scores

Morris (2016) and Wright (2018) reported the SF-36 MCS at two months and Denehy (2013) at three months follow-up. The results are pooled. Physical training did not result in clinically relevant and not statistically significant between-group differences (Figure 3).

Figure 2 Short term effects of physical training on SF-36 MCS scores

Schaller (2016) found no statistical significant difference on quality of life measured with SF-36 total scores at three months follow-up (intervention group, mean (SD): 61.3 (18.4); control group, mean (SD) 63.0 (19.9); group difference mean (95% CI): -1.7 (-10.1 to 6.7), p = 0.69).

Wright (2018) reported no statistically significant difference on quality of life assessed with the EQ-5D at three months (mean difference (95% CI): 0.07 (-0.06 to 0.19)).

7. Quality of life (important) – long-term

Various outcome measures were used to assess quality of life. The results are presented separately for the overall quality of life scales (EQ-5D and SF-36 total score), the SF-36 PCS and de SF-36 MCS.

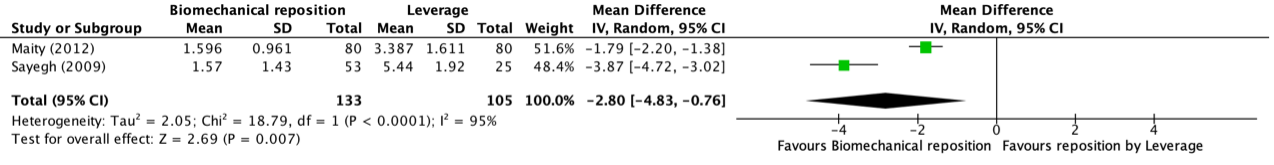

Denehy (2013), Eggmann (2018), Morris (2016) and Wright (2018) reported the SF-36 PCS at six months follow-up. The results are pooled. Physical training did not result in clinically relevant and not statistically significant between-group differences (Figure 2).

Figure 3. Long term effects of physical training on SF-36 PCS scores

Denehy (2013), Eggmann (2018), Morris (2016) and Wright (2018) reported the SF-36 MCS at six months follow-up. The results are pooled. Physical training did not result in clinically relevant and not statistically significant between-group differences (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Long term effects of physical training on SF-36 MCS scores

Hodgson (2016) found no statistically significant differences on quality of life assessed with the EQ-5D VAS (intervention group, mean (SD): 61 (19); control group, mean (SD): 68 (19), p = 0.25) and the EQ-5D Utility (intervention group, mean (SD): 0.63 (0.27); control group, mean (SD): 0.63 (0.33), p = 0.98) at six months follow-up.

Wright (2018) report no statistical significant difference on quality of life assessed with the EQ-5D at six months follow-up (mean difference (95% CI): 0.06 (-0.08 to 0.20)).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures cognitive functioning, PTSD and return to work could not be graded; no studies were found investigating these outcome measures.

RCTs start at high GRADE. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure walking distance in the short-term was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, bias due to incomplete outcome data and lack of blinding and selective outcome reporting in Wright (2018) ; -1); and the confidence intervals exceeding the minimal clinically (patient) important difference at both sides (imprecision; -2). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure walking distance in the long-term was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, bias due to incomplete outcome data and lack of blinding and selective outcome reporting in Wright (2018); -1); and the confidence intervals exceeding the minimal clinically (patient) important difference at both sides (imprecision; -2. The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures anxiety and depression in the long-term was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, unclear ROB for blinding and incomplete outcome data, and high risk of bias for other bias, limited reporting of the findings; -2) and the inclusion of a single study with a very limited sample size (imprecision; -2). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life in the short term was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias; -1, see ROB table); and because the confidence interval crosses the clinical decision threshold (imprecision; -). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life in the long-term was downgraded by 2 levels because of bias due to study limitations (risk of bias; -1); and because the confidence interval crosses the clinical decision threshold (imprecision; -1). The level of evidence is low.

2. Diaries

Description of studies

Three studies investigating the effect of diaries were included (Garrouste-Orgeas, 2019; Jones, 2010 and Nielsen, 2020). One of these studies were included in Geense (2019). All studies evaluated the effects on short-term.

Studies included in Geense (2019)

Jones (2010) examined the effect of diaries in the ICU written by healthcare staff and family members. Photos and a daily record of the ICU stay were also added. The intervention was performed by a research nurse or a doctor and took a few minutes per day. The intervention group consisted of 177 patients and the control group of 175 patients. The control group received the diary after 3 months. PTSD was measured with the Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome (PTSS)-14 score, the PTSD Diagnostic Scale (PDS) and the number of patients with new onset PTSD. PTSD was assessed at one and three months post ICU, the other outcomes only at three months post ICU.

Studies published after Geense (2019)

Garrouste-Orgeas (2019) performed a large multicenter RCT evaluating the effects of an ICU diary filled out by clinicians and family members during ICU stay when compared to usual care (no ICU diary). Thirty-five ICUs participated and 332 patients and family members were allocated to the intervention group and 325 patients to the control group. In this summary we only focus on the data of the patients. Assessments were performed at three months follow-up. Anxiety and depression were determined with HADS. PTSD symptoms were measured by the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) questionnaire. A large proportion of the included patients (n=255) had died before the follow-up. Furthermore, 63 patients were excluded from analyses (declined, had cognitive dysfunction, missing data, or no contact). Analyses were, therefore, performed for 164 patients in the intervention group and 175 patients in the control group.

Nielsen (2020) performed a multicenter RCT evaluating the effects of a diary authored by a close relative of a critically ill patient when compared to no dairy on psychological difficulties in patients and their relatives. In this summery we only focus on the data of the patients. The study was underpowered: it was estimated that 71 patients and relatives were required in each group, but due to slow inclusion only 36 patients were allocated to the intervention group (dairy) and 39 to the control group (no dairy). Attrition was also substantial (intervention n=10, control n=17, mainly “non-responders”). There were some differences in demographics between the groups analyzed, the percentage of female patients was higher in the control group (55 vs 42%), and the median age was lower (60 vs 68). Outcome measures were assessed three months after ICU discharge. Anxiety and depression were determined with HADS. PTSD was measured with PTSS-14 scores. Quality of life was determined with the SF-36.

Results for interventions with diaries

1. Walking distance (critical), 2. Cognitive functioning (critical), 6. Return to work (important)

These outcome measures were not reported in the included studies.

3. Anxiety (critical)

Garrouste-Orgeas (2019) found no statistically significant difference on anxiety (HADS-A, continuous scale) at three months follow-up (intervention group, median (IQR): 5 (2-8); control group, median (IQR): 6 (2-8); difference (95% CI): -0.36 (-1.22 to 0.50), p = 0.72). This difference is also considered as not clinically relevant. The number of patients with symptoms of anxiety (HADS>8) was not statistically or clinically relevant different between the groups (intervention group n=51, 31.3%; control group n=53, 30.6%, risk difference: 0.7%, 95%CI -9 to 11%, p=0.91).

Nielsen (2020) reported the number of patients scoring ≥ 11 on the HADS-A. No statistically significant difference was observed between the intervention group and control group three months after discharge from the ICU (intervention group, number: 5/25; control group, number: 3/22; relative risk (95% CI): 1.47 (0.40 to 5.44), p = 0.71).

Jones (2010) did not report this outcome measure.

4. Depression (important)

Garrouste-Orgeas (2019) found no statistically significant difference on depression at three months follow-up (intervention group, median (IQR): 4 (1-7); control group, median (IQR): 3 (2-7); difference (95% CI): -0.39 (-1.29 to 0.52), p = 0.66). This difference is also considered as not clinically relevant. The number of patients with symptoms of depression (HADS>8) was not statistically or clinically relevant different between the groups (intervention group n=31, 19%; control group n=41, 23.7%, risk difference: 5%, 95%CI -5 to 13%, p=0.35).

Nielsen (2020) reported the number of people who score ≥ 11 on the HADS-D (continuous scale). They found no statistically significant difference between the groups three months after discharge from the ICU (intervention group, number: 2/25; control group, number: 2/22; relative risk (95% CI): 0.88 (0.14 to 5.73), p = 1.0).

Jones (2010) did not report this outcome measure.

5. PTSD (important)

Garrouste-Orgeas (2019) found no statistically significant difference on IES-R scores at three months follow-up (intervention group, median (IQR): 12 (5-25); control group, median (IQR): 13 (6-27); difference (95% CI): -1.47 (-1.93 to 4.87), p = 0.38). The number of patients with an IES-R score >22 was not statistically or clinically relevant different between the groups (intervention group n=49, 29.9%; control group n=60, 34.3%, risk difference: -4%, 95%CI -15 to 6%, p=0.39).

Jones (2010) reported no statistically significant differences on PTSD determined with total PTSS-14 scores at one month (intervention group: 22.5 (14-84); control group: 25 (13-65)) and three months post ICU (intervention group, 24 (12.2); control group, 24 (11.6); unclear which measures of central tendency and statistical dispersion were reported). The number of patients that experienced the ICU as traumatically (PDS) was also not statistically significant at three months post ICU (intervention group, n (%): 70 (43.2); control group, n (%): 76 (47.5), p = 0.36). The number of patients with new onset PTSD was statistically significant different at three months post ICU: (intervention group, n (%): 8 (5); control group, n (%): 21 (13.1), p = 0.02).

Nielsen (2020) found no statistically significant differences three months after ICU discharge on total PTSS-14 scores (intervention group, median (range): 21 (14-75); control group, median (range): 28 (14-75); difference (95% CI): 11.2% (-15.7 to 46.8%), p = 0.44) or actual cases, defined as PTSS-14 scores > 31 (intervention group, number: 8/26; control group, number: 9/22; relative risk (95% CI): 0.75 (0.35 to 1.62), p = 0.55).

7. Quality of life (important)

Nielsen (2020) found no statistically significant differences on the eight subscales of the SF-36, three months after discharge from the ICU. 1. Physical function, intervention group mean: 45.8, control group mean: 38.6, p = 0.46. 2. Role physical, intervention group mean: 18.0, control group mean: 31.3, p = 0.25. 3. Bodily pain, intervention group mean: 62.6, control group mean: 52.7, p = 0.26. 4. global health, intervention group mean: 53.2, control group mean: 47.0, p = 0.36. 5. Vitality, intervention group mean: 48.5, control group mean: 55.2, p = 0.47. 6. Social function, intervention group mean: 68.8, control group mean: 64.2, p = 0.46. 7. Role emotional, intervention group mean: 49.3, control group mean: 50.8, p = 0.94. 8. Mental health, intervention group mean: 74.5, control group mean: 74.0, p = 0.76.

Garrouste-Orgeas (2019) and Jones (2010) did not report this outcome measure.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures walking distance, cognitive functioning and return to work could not be graded; no studies were found investigating these outcome measures.

RCTs start at high GRADE. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anxiety was mainly based on the results of Garrouste-Orgeas (2019); continuous data) and was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations (risk of bias; lack of blinding and loss-to follow-up -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure depression was mainly based on the results of Garrouste-Orgeas (2019; continuous data) and was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations (lack of blinding and loss-to follow-up; -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure PTSD was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, lack of blinding and loss-to follow-up; -1) and the limited number of included patients/events and the broader confidence intervals (imprecision; -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias; underpowered study, substantial attrition, differences in demographics between the groups, lack of blinding, limited reporting of the results; -2); and the inclusion of a single study with a limited number of patients (imprecision; -2). The level of evidence is very low.

3. Psychological counseling

Description of studies

One study was included that focused on psychological counseling. Wade (2019) was a cluster RCT with randomization occurring at ICU level. ICUs in the intervention group provided usual care during the baseline period (months 1-5). During the intervention period (months 7-onwards), these ICUs delivered a preventive, complex psychological intervention. This comprised 1) promotion of a therapeutic ICU environment; and for patients scoring ≥7 on the Intensive care Psychological Assessment Tool (IPAT) 1) three stress support sessions; and 2) a relaxation and recovery program. The intervention was delivered by trained ICU nurses. The ICUs in the control group provided usual care during both the baseline period and the intervention period. The intervention group consisted of 12 ICUs with 669 patients (285 patients recruited during the baseline period, 43 during the transition period and 341 during the intervention period) and the control group of 12 ICUs with 789 patients (285 patients recruited during the baseline period, 58 during the transition period and 446 during the intervention period). Anxiety and depression symptoms were determined with the HADS. PTSD symptoms were measured with the PTSD Symptom Scale - Self-Report (PSS-SR) questionnaire and quality of life with the EQ-5D-5L. Generalized linear mixed models were used and analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, deprivation, preexisting anxiety/depression, planned admission following elective surgery, and ICNARC Physiology Score. A total of 63.6% of the patients in the intervention group that were assessed with the IPAT, scored ≥7. More than one-third of these patients received less than 3 stress support sessions.

Results for interventions with psychological counseling

1. Walking distance (critical), 2. Cognitive functioning (critical), Return to work (important)

Wade (2019) did not report these outcome measures.

3. Anxiety (critical)

Wade (2019) reported that there was no statistically significant difference on anxiety (HADS-A) at six months (mean (95%CI) intervention ICUs baseline period: 6.9 (6.2 to 7.6), intervention period: 6.3 (5.7 to 7.0); control ICUs baseline period: 5.9 (5.3 to 6.7), intervention period: 5.7 (5.2 to 6.2), adjusted difference in difference (95% CI): −0.24 (−1.50 to 1.01), p = 0.70. This difference is considered not clinically relevant.

4. Depression (important)

Wade (2019) reported that there was no statistically significant difference on depression (HADS-D) at six months (mean (95% CI) intervention ICUs baseline period: 6.0 (5.3 to 6.7), intervention period: 5.8 (5.1 to 6.4); control ICUs baseline period: 5.3 (4.7 to 6.0), intervention period: 5.3 (4.8 to 5.8), adjusted difference in difference (95% CI): −0.22 (−1.40 to 0.95), p = 0.71. This difference is considered not clinically relevant.

5. PTSD (important)

Wade (2019) reported that there was no statistically significant difference in PTSD symptom severity (PSS-SR score) at six months (mean (95% CI) intervention ICUs baseline period: 11.8 (10.3 to 13.3), intervention period: 11.5 (10.0 to 12.9); control ICUs baseline period 10.1 (8.7 to 11.6), intervention period 10.2 (9.1 to 11.3), treatment effect (interaction between treatment group and time period) estimate: −0.03 (95%CI: −2.58 to 2.52), p = 0.98. This difference is considered not clinically relevant.

7. Quality of life (important)

Wade (2019) reported that there were no statistically significant difference in quality of life (mean (95%CI) EQ-5D-5L; intervention ICUs baseline period: 0.66 (0.62 to 0.70), intervention period: 0.67 (0.63 to 0.71); control ICUs baseline period: 0.70 (0.66 to 0.74), intervention period: 0.69 (0.66 to 0.72), adjusted difference in difference (95% CI) of 0.01 (−0.06 to 0.08), p = 0.85).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures walking distance, cognitive functioning and return to work could not be graded; no studies were found investigating these outcome measures.

RCTs start at high GRADE. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anxiety was downgraded by one levels because of the lack of blinding (risk of bias), the unclear risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data and the inclusion of only one study (imprecision; -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure depression was downgraded by one level because of inclusion of the lack of blinding (risk of bias), the unclear risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data only one study (imprecision; -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure PTSD was downgraded by one level because of the lack of blinding (risk of bias), the unclear risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data and the inclusion of only one study (imprecision; -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by one level because of the lack of blinding (risk of bias), the unclear risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data and the inclusion of only one study (imprecision; -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

4. Information and education

Description of studies

The review of Geense (2019) included two studies that examined information and education interventions and met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. The literature search did not reveal any additional studies.

Demircelik (2016) investigated a multimedia informational education program for patients admitted to a coronary ICU. The intervention group received multimedia education which was carried out by ICU nurses while the control group did not receive multimedia nursing education. Technical materials were prepared for multimedia nursing education. Materials were the same for each patient. No further information was provided regarding the content of the intervention. Both the intervention group and the control group consisted of 50 patients. The control group received usual care. Anxiety and depression were assessed with the HADS.

Fleischer (2014) studied the effect of a structured information program during ICU-stay. The intervention was designed as a guided conversation with both a standardized and an individualized part. The standardized part of the intervention covered general information on nine topics: 1) people in the ICU, 2) devices and monitoring, 3) room furnishing, 4) individual safety, 5) schedule, 6) communication, 7) staff duties, 8) conveniences, and 9) helpful thoughts. In the individual part the patients were allowed to choose any number of cards from seven that depicted common fears: 1) fear of complications, 2) fear of suffocating, 3) fear of pain, 4) fear of being helpless, 5) fear of death, 6) fear of being lonely, and 7) fear of being confined. The intervention group consisted of 104 patients and the control group of 107 patients. The control group received a non-specific episodic conversation of similar length additional to standard care. Quality of life was determined three months after discharge with the SF-12 PCS, SF-12 MCS and Schedule for evaluation of Individual quality of life (SEIQoL).

Results for information and education interventions

1. Walking distance (critical), 2. Cognitive functioning (critical), 5. PTSD (important), 6. Return to work (important)

Demircelik (2016) and Fleischer (2014) did not report these outcome measures.

3. Anxiety (critical)

Demircelik (2016) found a likely statistically significant and clinically relevant difference between the groups in HADS-A change scores between ICU stay and one week after discharge from the hospital, p<0.01. The intervention group had a mean (SD) score of 6.1 (0.7) during the ICU stay and 1.9 (0.2) at one week after discharge. The control group had a mean (SD) score of 5.7 (0.6) during ICU stay and 5.1 (0.6) at one week after discharge.

Fleischer (2014) did not report this outcome measure.

4. Depression (important)

Demircelik (2016) found a statistically significant and clinically relevant difference between groups in HADS-D change scores between ICU stay and 1 week after discharge from the hospital, p<0.01. The intervention group had a mean (SD) score of 5.4 (0.6) during the ICU stay and 1.9 (0.25) at one week after discharge. The control group had a mean (SD) of 5.1 (0.5) during ICU stay and 4.8 (0.5) at one week after discharge.

Fleischer (2014) did not report this outcome measure.

7. Quality of life (important)

Demircelik (2016) did not report this outcome measure.

Fleischer (2014) found no statistically significant differences in quality of life between the intervention group (mean (SD): 40.6 (9.4)) and control group (mean (SD): 40.4 (10.0)) on the SF-12 PCS (adjusted mean difference (95% CI): 0.3 (-3.4 to 3.6), p = 0.87), SF-12 MCS (intervention group, mean (SD): 46.9 (11.3); control group, mean (SD): 48.2 (11.2); adjusted mean difference (95% CI): -1.3 (-5.3 to 2.6), p = 0.50) and SEIQoL (intervention group, mean (SD): 74.9 (18.2); control group, mean (SD): 73.6 (20.1); adjusted mean difference (95% CI): 2.0 (-5.1 to 9.2), p = 0.58). These differences are considered not clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures walking distance, cognitive functioning, PTSD and return to work could not be graded; no studies were found investigating these outcome measures.

RCTs start at high GRADE. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anxiety was downgraded by three levels because of the limited description of the methods used (risk of bias; -2) and the inclusion of only one study with a limited sample size (imprecision; -1). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure depression was downgraded by three levels because of the limited description of the methods used (risk of bias; -2) and the inclusion of only one study with a limited sample size (imprecision; -1). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by two level because of lack of blinding of the outcome assessment (risk of bias; -1) and the inclusion of only one study with a limited sample size (imprecision; -1). The level of evidence is low.

5. Optimizing the ICU environment

Description of studies

One study was included investigating optimizing the ICU environment. This study by Demoule (2017) was included in the review of Geense (2019). The effect of earplugs and eye masks during ICU-stay was investigated. The intervention was performed by trained nurses between 10:00 PM and 8:00 AM until discharge from the ICU. The control group received routine care during the night. Both the intervention group and control group consisted of 32 patients. Anxiety and depression were determined with the HADS and PTSD symptoms with the IES-R.

Results for interventions on optimizing the ICU environment

1. Walking distance (critical), 2. Cognitive functioning (critical), 6. Return to work (important), 7. Quality of life (important)

Demoule (2017) did not report these outcome measures.

3. Anxiety (critical)

Demoule (2017) found no statistically significant difference on HADS-A at day 90 following randomization (intervention group, median (IQR): 8 (4-11); control group, median (IQR): 6 (4-12), p = 0.69). The clinical relevance could not be determined because the data is non-parametric.

4. Depression (important)

Demoule (2017) found no statistically significant difference on HADS-D at day 90 following randomization (intervention group, median (IQR): 6 (3-12); control group, median (IQR): 6 (2-9), p = 0.63). The clinical relevance could not be determined because the data is non-parametric. However, this difference is likely not clinically relevant.

5. PTSD (important)

Demoule (2017) found no statistically significant difference in PTSD symptoms at day 90 following randomization (intervention group, median (IQR): 11 (5-18); control group, median (IQR): 16 (9-27), p = 0.15).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures walking distance, cognitive functioning, return to work and quality of life could not be graded; no studies were found investigating these outcome measures.

RCTs start at high GRADE. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anxiety was downgraded by 3 levels because of the risk of bias (for instance risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data and due to selective outcome reporting ; -2), and the inclusion of only one study with a limited sample size (imprecision; -1). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure depression was downgraded by 3 levels because of risk of bias (for example risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data and due to selective outcome reporting; -2), and the inclusion of only one study with a limited sample size (imprecision; -1). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure PTSD was downgraded by 3 levels because of risk of bias (for example risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data and due to selective outcome reporting; -2), and the inclusion of only one study with a limited sample size (imprecision; -1). The level of evidence is very low.

Zoeken en selecteren

In order to answer the clinical question, a systematic literature analysis was carried out for the following search questions:

Search question 1. What are the effects of pharmacological interventions initiated in the ICU aiming at prevention of PICS in adult patients who are admitted to the intensive care unit?

P: adult patients (18 years or older) who are admitted to the intensive care unit

I: pharmacological interventions (medication) aiming at prevention of new or worsening of physical, cognitive and/or psychological complaints (symptoms of PICS) and initiated in the ICU

C: no treatment or placebo

O: walking distance, cognitive functioning, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), return to work and quality of life

Search question 2.What are the effects of non-pharmacological interventions aimed at prevention of PICS in adult patients who are admitted to the intensive care unit when the intervention is initiated?

P: adult patients (18 years or older) who are admitted to the intensive care unit

I: non-pharmacological interventions (physical training, diaries, cognitive training, psychological counseling, optimizing the ICU environment, information and education, communication tools, behavior of health care providers) aiming at prevention of new or worsening of physical, cognitive and/or psychological complaints (symptoms of PICS) and initiated in the ICU

C: no treatment or usual care

O: walking distance, cognitive functioning, anxiety, depression, PTSD, return to work and quality of life

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered walking distance, cognitive functioning and anxiety as critical outcome measures for decision making and depression, PTSD, return to work and quality of life as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Cognitive functioning: as determined with a validated questionnaire or neuropsychological test to determine cognitive functioning.

- Anxiety, depression and PTSD: as determined with a validated questionnaire to identify anxiety, depression or PTSD, respectively.

- Quality of life: as determined with a validated quality of life questionnaire.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures ‘walking distance’ and ‘return to work’ but applied the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined 30 meters on the 6-minute walk test (Dajczman, 2015), 1.5 points on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) anxiety scale, 1.5 points on the HADS depression scale (Puhan, 2008), 3 points on the SF-36 PCS and 3 points on the SF-36 MCS (Frendl, 2014) as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Outcome measures are included if measured after discharge from the hospital. If possible, they are subdivided into short term (after discharge from the hospital until 6 months after discharge) and long term (6 months or more after discharge from the hospital) effects.

Search and select (Methods)

For search question 1, the databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 15th of January 2020 for systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The detailed search strategies are depicted under the tab Methods. This search yielded in 210 hits.

For search question 2, a recent systematic review was available (Geense, 2019). In addition, the databases Medline (via OVID) and Cinahl (via Ebsco) were searched with relevant search terms until 15th of January 2020 for systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in 2018 or later. The detailed search strategies are depicted under the tab Methods. This search yielded in 144 hits.

Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews (searched in at least two databases, and detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available) and RCTs answering one of the PICO’s above. In addition, at least twenty patients per study arm have had to be included.

For search question 1, 13 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 12 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and one study was included.

For search question 2, 22 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 18 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods). Four studies answered the second search question, in addition to the review of Geense (2019).

Results

One study (Needham, 2016) was included in the analysis of the literature for search question 1.

For search question 2, four studies (Eggmann, 2018; Garrouste-Orgeas, 2019; Nielsen, 2020 and Wade, 2019) were included besides the review from Geense, 2019. Given the large variation in studied interventions, we decided to classify the analysis of the literature for the second search question by intervention type: 1) physical training, 2) diaries, 3) psychological counseling, 4) information and education, and 5) optimizing the ICU environment. No literature has been found on interventions consisting of cognitive training, communication tools and behavior of health care providers. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Dajczman, E., Wardini, R., Kasymjanova, G., Préfontaine, D., Baltzan, M. A., & Wolkove, N.

(2015). Six minute walk distance is a predictor of survival in patients with chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation. Canadian respiratory journal, 22(4), 225-229. - Demircelik, M. B., Cakmak, M., Nazli, Y., Şentepe, E., Yigit, D., Keklik, M., ... & Eryonucu, B.

(2016). Effects of multimedia nursing education on disease-related depression and anxiety in patients staying in a coronary intensive care unit. Applied Nursing Research, 29, 5-8. - Demoule, A., Carreira, S., Lavault, S., Pallanca, O., Morawiec, E., Mayaux, J., ... & Similowski,

T. (2017). Impact of earplugs and eye mask on sleep in critically ill patients: a prospective randomized study. Critical Care, 21(1), 284. - Denehy, L., Skinner, E. H., Edbrooke, L., Haines, K., Warrillow, S., Hawthorne, G., ... &

Berney, S. (2013). Exercise rehabilitation for patients with critical illness: a randomized controlled trial with 12 months of follow-up. Critical Care, 17(4), R156. - Eggmann, S., Verra, M. L., Luder, G., Takala, J., & Jakob, S. M. (2018). Effects of early,

combined endurance and resistance training in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: A randomised controlled trial. PloS one, 13(11), e0207428. - Fleischer, S., Berg, A., Behrens, J., Kuss, O., Becker, R., Horbach, A., & Neubert, T. R. (2014).

Does an additional structured information program during the intensive care unit stay reduce anxiety in ICU patients?: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC anesthesiology, 14(1), 48. - Frendl, D. M., & Ware Jr, J. E. (2014). Patient-reported functional health and well-being

outcomes with drug therapy: a systematic review of randomized trials using the SF-36 health survey. Medical care, 439-445. - Garrouste-Orgeas, M., Flahault, C., Vinatier, I., Rigaud, J. P., Thieulot-Rolin, N., Mercier, E.,

... & Hamidfar, R. (2019). Effect of an ICU diary on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a randomized clinical trial. Jama, 322(3), 229-239. - Geense, W. W., van den Boogaard, M., van der Hoeven, J. G., Vermeulen, H., Hannink, G., &

Zegers, M. (2019). Nonpharmacologic interventions to prevent or mitigate adverse

long-term outcomes among ICU survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical care medicine, 47(11), 1607-1618. - Hendriks, M. M. C., Janssen, F.A.M., Te Pas, M.E., Kox, J. H. J. M., van de Berg, P.J.E.J.,

Bruise, M. P., de Bie, A. J. R. (2019). Post-icu care after a long intensive care

admission: A Dutch inventory study. Translated Name Netherlands Journal of Critical Care, 27(5):190-5. - Hodgson, C. L., Bailey, M., Bellomo, R., Berney, S., Buhr, H., Denehy, L., ... & Papworth, R.

(2016). A binational multicenter pilot feasibility randomized controlled trial of early goal-directed mobilization in the ICU. Critical care medicine, 44(6), 1145-1152. - Jones, C., Bäckman, C., Capuzzo, M., Egerod, I., Flaatten, H., Granja, C., ... & Griffiths, R. D.

(2010). Intensive care diaries reduce new onset post traumatic stress disorder following critical illness: a randomised, controlled trial. Critical care, 14(5), R168. - KNMG (2021) Behandelprotocol Fysiotherapie op de intensive care. Beschikbaar via kngf.nl/kennisplatform

- Mendez-Tellez, P. A., & Needham, D. M. (2012). Early physical rehabilitation in the ICU and

ventilator liberation. Respiratory care, 57(10), 1663–1669. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.01931 - Morris, P. E., Berry, M. J., Files, D. C., Thompson, J. C., Hauser, J., Flores, L., ... & Bakhru, R.

N. (2016). Standardized rehabilitation and hospital length of stay among patients with acute respiratory failure: a randomized clinical trial. Jama, 315(24), 2694-2702. - Needham, D. M., Davidson, J., Cohen, H., Hopkins, R. O., Weinert, C., Wunsch, H., ... &

Brady, S. L. (2012). Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive

care unit: report from a stakeholders' conference. Critical care medicine, 40(2), 502-509. - Needham, D. M., Colantuoni, E., Dinglas, V. D., Hough, C. L., Wozniak, A. W., Jackson, J. C.,

... & Hopkins, R. O. (2016). Rosuvastatin versus placebo for delirium in intensive care and subsequent cognitive impairment in patients with sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: an ancillary study to a randomised controlled trial. The lancet Respiratory medicine, 4(3), 203-212. - Nielsen, A. H., Angel, S., Egerod, I., Lund, T. H., Renberg, M., & Hansen, T. B. (2020). The

effect of family-authored diaries on posttraumatic stress disorder in intensive care unit patients and their relatives: a randomised controlled trial (DRIP-study). Australian Critical Care, 33(2), 123-129. - Puhan, M. A., Frey, M., Büchi, S., & Schünemann, H. J. (2008). The minimal important

difference of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease. Health and quality of life outcomes, 6(1), 46. - Schaller, S. J., Anstey, M., Blobner, M., Edrich, T., Grabitz, S. D., Gradwohl-Matis, I., ... & Lee,

J. (2016). International Early SOMS-guided Mobilization Research Initiative: Early,

goal-directed mobilisation in the surgical intensive care unit: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 388(10052), 1377-1388. - Wade, D. M., Mouncey, P. R., Richards-Belle, A., Wulff, J., Harrison, D. A., Sadique, M. Z., ...

& Als, N. (2019). Effect of a nurse-led preventive psychological intervention on symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder among critically ill patients: a randomized clinical trial. Jama, 321(7), 665-675. - Wright, S. E., Thomas, K., Watson, G., Baker, C., Bryant, A., Chadwick, T. J., ... & Stafford, V.

(2018). Intensive versus standard physical rehabilitation therapy in the critically ill (EPICC): a multicentre, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Thorax, 73(3), 213-221.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies – pharmacological interventions

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Needham, 2016 |

Type of study:

Setting and country: 35 hospitals in the USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

For the assessment of cognitive function, we also excluded patients

interview with the patient or their proxy) N total at baseline: Intervention: 164 Control: 165

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 52 (18) C: 53 (15)

Sex: I: 50% women C: 52% women APACHE II ± SD: I: 90 (27) C: 89 (28)

Groups comparable at baseline? Baseline patient and intensive care unit characteristics were similar in each group |

Rosuvastatin (40 mg loading dose and then 20 mg daily until the earliest of 3 days after discharge from intensive care, study day 28, or death) |

Matched placebo |

Length of follow-up

Intervention: N (%): 111 (67.7%) Reasons (describe) 12 died between discharge and initial follow-up 3 enrolled before addition of cognitive substudy 44 exclusion criteria for follow-up 7 missed follow-up at 6 months 23 ineligible for follow-up

Control: N (%): 88 (53.3%) Reasons (describe) 12 died between discharge and initial follow-up 2 enrolled before addition of cognitive substudy 31 exclusion criteria for follow-up 7 missed follow-up at 6 months 22 ineligible for follow-up

|

Cognitive functioning

Working memory and attention (mean Digit Span score, SD) I: 9.2 (2.5) p = 0.49

Immediate memory (mean Logical Memory I score, SD) I: 8.6 (3.4) C: 8.9 (3.3) p = 0.49

Delayed memory (mean Logical Memory II score, SD) I: 7.9 (3.3) C: 8.8 (2.7) Effect (95% CI): –1.2 (–2.2 to –0.2) p = 0.017

|

There were significant associations between assignment to rosuvastatin and worse delayed memory, with a worse mean continuous score and a greater percentage of patients with impaired delayed memory |

Evidencetable for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies) – non-pharmacological interventions

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Geense, 2019

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up until July 19, 2018.

A: Denehy, 2013 B: Demircelik, 2016 C: Demoule, 2017 D: Fleischer, 2014 E: Hodgson, 2016 F: Jones, 2010 G: Morris, 2016 H: Schaller, 2016 I: Wright, 2018

Setting and country: F: UK, Denmark, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Sweden I: UK

Source of funding: Not reported for the individual studies

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

● Adult patients admitted to the ICU for at least 12 hours. ● Interventions performed before, during, or after ICU admission and aimed to prevent or mitigate long-term adverse outcomes. ● Outcomes measured after hospital discharge. Physical (e.g., pain, fatigue), mental (e.g., anxiety, depression), or cognitive (e.g., memory, attention) outcomes were included, as well as quality of life and outcomes such as social functioning and daily activities. ● The study design was a randomized controlled trial (RCT), non-RCT (NRCT), controlled before-after, or interrupted time series.

Exclusion criteria SR:

● Studies that included patients in the PICU, postanesthesia care unit, or coronary care unit ● Pharmacologic and nutritional interventions ● Outcomes related to healthcare utilization, costs, length of stay, ICU and hospital mortality, and readmissions

36 studies included, of which 9 could be included in this part of the literature summary.

We excluded two non-RCTs, three RCTs with an intervention which was started before ICU admission, 13 RCTs with interventions that started after ICU discharge, one RCT with an intervention that didn’t match our PICO, one RCT in which the control group received another intervention instead of no treatment or usual care, one RCT with outcome measures that didn’t match our PICO and six studies with less than twenty patients per study arm. |

A: Exercise rehabilitation program B: Multimedia informational education program F: Diary Duration and frequency of treatment A: Start day 5 > ICU admission (<15 min/ day). 7 d/w on ward(2x 30 min), 2x p/w for 8 weeks in outpatient setting (60 min) ICU discharge level: 30 to 60 min p/d F: Few min p/d (except for starting diary)

|

A: Usual care, may included active bed exercises, sitting out of bed/ marching/walking F: Diary (received diary after 3 mo)

|

A: Baseline; ICU discharge (ICU-D); hospital discharge (HD) to home; 3 mo; 6 mo; 12 mo F: 1 mo; 3 mo post ICU

|

Walking distance A: mean difference from usual care (95% CI) ICU discharge: −44.7 (−82.3 to −7.1) 3 mo: 15.4 (−40.1 to 71) 6 mo: −4.9 (−68.0 to 58.3) 12 mo: 4.7 (−59.7 to 69.2) B: not reported F: not reported I: adj. difference in means (95%CI) hospital discharge: −27.9 (−86.1 to 31.8) 6 mo: 61.7 (−47.2 to 157.0)

Anxiety D: not reported F: not reported

HADS-D A: not reported F: not reported G: not reported A: not reported I: 11 (5-18) E: not reported Intervention: 22.5 (14-84) Control: 25 (13-65) NS PTSS 14 at 3 months, median (range) Intervention: 24 (±12.2) Control: 24 (±11.6) Intervention: 70 (43.2) Intervention: 8 (5) Control: 21 (13.1) G: not reported 3 mo: mean (sd) 6 mo: mean (sd) 12 mo: mean (sd) B: not reported C: not reported D: not reported E: not reported F: not reported G: difference least square mean (95%CI) 6 mo: 3.4 (−0.02 to 7.0) H: not reported

3 mo: 6 mo: 12 mo: F: not reported HD: 0.3 (−2.7 to 3.3) p = 0.86 2 mo: 0.1 (−3.5 to 3.7) p = 0.96 p = 0.91 p = 0.19 3 mo: 4.2 (−1.2 to 9.5)

SF-36 A: not reported B: not reported C: not reported D: not reported E: not reported F: not reported H: 3 mo: group difference mean (95%CI) I: not reported

SF-12 B: not reported C: not reported D: SF-12 PCS, 3 mo after discharge: mean (SD) E: not reported F: not reported A: not reported B: not reported C: not reported D: 3 mo after discharge: mean (SD) E: not reported F: not reported

EQ-5D B: not reported C: not reported D: not reported E: EQ-5D VAS 6 months, mean (SD) p = 0.98 F: not reported G: not reported H: not reported 6 months, mean (SD) |

Risk of bias (ROB): Random sequence generation Low ROB: A, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, Unclear: B

Allocation concealment Low ROB: A, D, E, F, G, H Unclear: B, C, I High ROB: -

Blinding of patients and personnel High ROB: -

Blinding of outcome assessment Low ROB: A, G, I Unclear: B, C, E, F, H

Incomplete outcome data Low ROB: F High ROB: C, I

Selective reporting Unclear: B, G

Other bias Low ROB: B, D, G |

Evidence table for intervention studies – non-pharmacological interventions

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Eggmann, 2018 |

Type of study: RCT

mixed ICU of an academic centre in Switzerland

|

Inclusion criteria: Adults (≥18 years) expected to stay on MV for at least 72 hours and who had been independent before the onset of critical illness. Independence was defined as living without assistance and qualitatively determined by the patient’s family or medical-health records.

previous muscle weakness, contraindications to cycling, enrolment in another intervention study, palliative care, admission diagnosis that excluded the possibility of walking at hospital discharge, and patients who did not understand German or French N total at baseline: Intervention: 58 Control: 57

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 65±15 Sex: I: 38% female C: 28% female

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Early, progressive endurance and resistance training programme combined with early mobilisation. Sedation was reduced if medically permitted prior to physiotherapy |