Aanvullende diagnostiek: PCT

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de beste teststrategie bij kinderen met koorts verdacht van ernstige dan wel invasieve (bacteriële) infecties als het gaat om betrouwbaarheid van de diagnose, belasting van het kind, kosten en praktische haalbaarheid?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik biomarkers, net als klinische kenmerken, als alarmsignaal om een ernstige (SBI) en invasieve bacteriële infectie (IBI) te onderzoeken. Zonder klinische verdenking is het gebruik van een biomarker alleen onvoldoende om uitsluitsel te geven ten aanzien van de aan- of afwezigheid van SBI of IBI.

Voor het vaststellen van een ernstige infectie wordt aanbevolen om de afkapwaarden >80 mg/L voor CRP en >2,0 ng/mL voor PCT aan te houden (‘rood’ alarmsymptoom). Voor het uitsluiten van ernstige infecties wordt aanbevolen om <20 mg/L voor CRP en <0,5 ng/mL voor PCT aan te houden (’groen’ alarmsymptoom). Zie module Prognostische factoren ernstige bacteriële infectie.

Bepaal CRP of PCT bij alle kinderen met koorts en een duidelijke verdenking op een bacteriële infectie (zie module Prognostische factoren ernstige bacteriële infectie).

Bepaal bij voorkeur PCT:

- Als de koortsklachten minder dan 8-12 uur bestaan.

- Bij discrepantie tussen enerzijds een sterk klinische verdenking en anderzijds een niet of marginaal afwijkende CRP waarde

- Voor het inschatten van het risico op een invasieve bacteriële infectie (IBI) als onderdeel van ernstige bacteriële infectie (SBI)

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Twee systematische reviews en vijf additionele cohortstudies, die de sensitiviteit en specificiteit van PCT en CRP onderzochten, werden geïncludeerd in de literatuuranalyse. Bij een afkapwaarde van 0,5 ng/mL lijkt de specificiteit van PCT voor het opsporen van ernstige bacteriële infectie (SBI) of invasieve bacteriële infecties (IBI) wat hoger te zijn dan de sensitiviteit. De sensitiviteit en specificiteit van CRP lijkt ongeveer even hoog, maar de spreiding in sensitiviteit is wel wat groter. In het algemeen lijkt de sensitiviteit van PCT wat groter te zijn dan de sensitiviteit van CRP. Bij een sterke klinische verdenking en een CRP kleiner dan 80 mg/L is het bepalen van PCT aan te raden. Zowel CRP als PCT hebben grotere diagnostische waarde dan het leukocytengetal.

De bewijskracht van de diagnostische waarde is beoordeeld als redelijk of laag. Dit heeft te maken met het risico op bias, doordat veel studies niet of beperkt rapporteren hoe en op welk moment de referentietest is afgenomen, zodat onduidelijk is of de resultaten onafhankelijk van de indextest zijn beoordeeld. De heterogeniteit in de gemeten sensitiviteit en specificiteit tussen studies kan deels toegeschreven worden aan de verschillen in leeftijden of het tijdstip van afnemen van de test. Dit laatste is echter wel in overeenstemming met de praktijk, waarin een kind op verschillend momenten na aanvang ziekte beoordeeld wordt, en al dan niet een laboratoriumbepaling krijgt.

Bij een kind met koorts zijn zowel de klinische beoordeling als het gebruik van biomarkers (CRP en/of PCT) op zich zelf vaak onvoldoende om een SBI dan wel IBI uit te sluiten of aan te tonen. De combinatie voegt echter wel waarde toe. Door bij een klinische verdenking CRP en/of PCT mee te wegen kan adequater worden beoordeeld of er sprake is van een bacteriële infectie en zo ja of er sprake is van een SBI of IBI.

Recente literatuur laat zien dat PCT beter dan CRP in staat is om onderscheid te maken tussen een SBI vs. IBI. Vergeleken met CRP lijkt PCT een hogere sensitiviteit te hebben en dus een hogere negatief voorspellende waarde op het hebben van een IBI. Dit is mede toe te schrijven aan de kinetiek van PCT en CRP. De piek in PCT-release als reactie op een systemische infectie is na 12 tot 24 uur terwijl CRP en leukocyten na 48 tot 72 uur op de piekwaarde zit, waardoor de sensitiviteit van de markers sterk bepaald wordt door het tijdstip van afname van de test.

Gezien deze verschillen in kinetiek tussen CRP en PCT in reactie op een infectie is PCT ook beter in staat een vroege bacteriële infectie aan te tonen dan wel uit te sluiten. Het valt dien ten gevolge te overwegen om ook bij een verdenking op een SBI waarbij de klachten pas sinds enige uren (8-12 uur) bestaan, te kiezen voor PCT.

De biomarkers besproken in deze richtlijn (CRP en PCT) richten zich met name op een bacteriële focus als oorzaak van de koorts. Onder andere de biomarkers TRAIL en IP10 lijken bruikbaar voor snelle objectivering van een virale focus als oorzaak van de koorts, maar zijn nog niet 24/7 beschikbaarheid binnen een routinematige laboratorium setting (van Houten, 2017). Toekomstige studies moeten duidelijk maken in hoeverre het gebruik van deze nieuwe virale biomarkers een toegevoegde waarde hebben bij de triage van kinderen met koorts.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

In het geval van minder waarschijnlijk maken van een bacteriële infectie of bij de differentiatie tussen SBI vs. IBI is een snelle terugrapportagetijd gewenst.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Sinds de publicatie van de vorige richtlijn is 24/7 beschikbaarheid van PCT in ziekenhuizen sterk toegenomen. Een recente uitvraag bij laboratoria leert dat van de 29 respondenten 23 laboratoria PCT 24/7 aanbieden en dat bij 4 van de 6 laboratoria die geen PCT aanbieden er lokale afspraken zijn met betrekking tot analyse in laboratoria die PCT wel aanbieden.

Geen van de onderzochte biomarkers kan op zichzelf een bacteriële infectie volledig uitsluiten of aantonen. Tegen deze achtergrond is het af te raden biomarkers aan te vragen wanneer de klinische verdenking op een bacteriële infectie laag is.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De alomtegenwoordige 24/7 beschikbaarheid van CRP in vergelijking met PCT maakt CRP de aangewezen biomarker voor kinderen met een verdenking op een ernstige bacteriële infectie. Houdt bij een niet afwijkende uitslag wel rekening met een fout-negatieve uitslag bij slechts kortdurend bestaande klachten (8-12 uur). Bij slechts een duidelijke verdenking op een IBI of bij een sterke klinische verdenking bij een niet afwijkend CRP kan gebruik worden gemaakt van de toenemende 24/7 beschikbaarheid van PCT in de laboratoria. Indien PCT niet wordt aangeboden binnen uw ziekenhuis is het aan te bevelen om in samenspraak met het laboratorium van uw ziekenhuis een lokaal protocol op te stellen met daarin beschreven de procedure voor het aanvragen van PCT. De klinisch chemicus van uw eigen ziekenhuis kan u in deze adviseren en u informeren over de (regionale) beschikbaarheid van PCT en daarmee een inschatting maken over de eventuele terugrapportagetijd van PCT.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

In combinatie met de klinische beoordeling hebben zowel CRP en PCT als infectiemarkers een toegevoegde diagnostische waarde bij de triage van kinderen met koorts. De diagnostische waarde van het leukocytengetal bij deze kinderen is daarentegen beperkt. Ondanks het gebruik van een lagere afkapwaarden voor CRP (40 mg/L) als ‘rood’ alarmsymptoom in de opgenomen literatuur is er onvoldoende bewijskracht om de huidige CRP afkapwaarde van 80 mg/L te verlagen. Bij CRP concentraties onder de 80 mg/L bij een wel sterke klinische verdenking is het bepalen van PCT aan te raden.

Deze module voorziet in de ondersteuning van de teststrategie om een bacteriële infectie (ernstig dan wel invasief) vast te stellen dan wel uit te sluiten.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In de vorige richtlijn is er een belangrijke rol weggelegd voor c-reactive proteïne (CRP) als infectieparameter bij het kind met koorts. In de vorige richtlijn (2013) wordt slechts in enkele specifieke gevallen (o.m. invasieve infecties, kortdurende koorts) een toegevoegde waarde gegeven voor het gebruik van procalcitonine (PCT).

In de klinische praktijk is het belangrijk om tijdig onderscheid te maken tussen een ernstige bacteriële infectie (SBI; o.m. urineweginfectie, gastro-intestinale infectie) en invasieve bacteriële infectie (IBI; o.m. bacteriemie/sepsis, bacteriële meningitis). Het vroegtijdig onderscheid kunnen maken tussen deze twee entiteiten van bacteriële infectie is belangrijk voor de verdere behandeling van het kind.

Er zijn aanwijzingen in de recente literatuur die aantonen dat PCT een betere diagnostische accuratesse heeft dan CRP voor het vaststellen van een invasieve bacteriële infectie. Daar waar de beschikbaarheid en 24/7 aanvraagbaarheid van PCT de laatste jaren is toegenomen, is de inbedding van PCT in de klinische praktijk (bekendheid) nog steeds beperkt.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

PCT

|

Low GRADE |

The sensitivity for detecting serious bacterial infections (SBI) in children with fever without source using procalcitonin (PCT) with a cut-off of 0.5 ng/mL varies between 38% and 93%, the specificity varies between 50% and 98%.

Sources: Tripella, 2017; Yo, 2012; Hubert-Dibon, 2018; Lee, 2018; Han, 2019 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

The sensitivity for detecting invasive bacterial infections (IBI) in children with fever without source using procalcitonin (PCT) with a cut-off of 0.5 ng/mL varies between 73% and 87%, the specificity varies between 72% and 93%.

Sources: Tripella, 2017; Hubert-Dibon, 2018 |

CRP

|

Low GRADE |

The sensitivity for detecting serious bacterial infections (SBI) in children with fever without source using C-reactive protein (CRP) with a cut-off of 40 mg/L varies between 36% and 89%.

Sources: Yo, 2012; Hubert-Dibon, 2018; Gunduz, 2018 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

The specificity for detecting serious bacterial infections (SBI) in children with fever without source using C-reactive protein (CRP) with a cut-off of 40 mg/L varies between 65% and 94%.

Sources: Yo, 2012; Hubert-Dibon, 2018; Gunduz, 2018 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Tripella (2017) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis concerning the diagnostic accuracy of procalcitonin (PCT) for serious bacterial infections (SBI) and invasive bacterial infections (IBI) in children with fever without source. The authors searched Medline for literature published between 2007 and 2017. They included studies performed in children ≤ 18 presenting with fever without source in hospital or ambulatory settings in Western countries, serum concentrations of PCT were obtained as part of the first patient

evaluation and the results reported quantitatively, and the outcomes SBI and/or IBI were defined a priori. Studies that did not report the sensitivity and specificity of PCT were excluded. SBI was defined as a broad spectrum of conditions (e.g., bacterial meningitis, sepsis, bacteremia, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, bacterial gastroenteritis, bone- or soft tissue infections). IBI was defined as a subgroup of most severe bacterial infections (e.g. bacterial meningitis, sepsis, and bacteremia). The methodological quality of included studies was assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool; one study (Freyne, 2013) was excluded because of a high risk of bias in more than 2 domains. Twelve studies (7260 children) were included in the meta-analysis. All included studies were performed in ED settings. The prevalence of SBI/IBI varied between 1.0% and 45.9% in the included studies. The most reported cut-offs for PCT were 0.5 ng/mL (9 studies) and 2 ng/mL (6 studies). In the meta-analyses the pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity for the cutoffs 0.5 ng/mL and 2 ng/mL were calculated.

Yo (2012) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis concerning the diagnostic accuracy of PCT, C-reactive protein (CRP) and leukocytes for SBI in children presenting to the ED with fever without source. In 2011 the authors searched the Medline, Embase, and Cochrane databases for relevant literature. Studies performed in children aged between 7 days and 36 months, reporting PCT alone or compared to other laboratory markers to detect SBI, and reporting enough data to create 2 by 2 tables were included. The authors did not define SBI a priori, and SBI was defined differently in the included studies, for instance bacteremia, pyelonephritis, lobar pneumonia, and meningitis osteoartritis (Lacour, 2001), or urinary tract infection, bacteremia, cellulitis, sepsis, bacterial gastroenteritis, and pneumonia (Olaciregui, 2009). The methodological quality of included studies was assessed using the QUADAS tool. Eight studies (1883 children) were included in the meta-analysis. All studies reported PCT, six studies reported CRP, and seven studies reported leukocytes. The prevalence of SBI/IBI varied between 3.2% and 29.2% in the included studies. The most reported cut-offs were 0.5 ng/mL for PCT (5 studies), 40 mg/L for CRP (4 studies), and 15000 cells/mm for leukocytes (6 studies). The authors used a bivariate random-effects model to calculate the overall diagnostic accuracy. Subgroup analyses were performed for the most common cut-offs.

Hubert-Dibon (2018) performed a prospective cohort study concerning the diagnostic accuracy of PCT and CRP for SBI in children aged between 6 days and 5 years who presented to a French pediatric ED with fever without source in 2016. The authors defined SBI as invasive bacterial infections, urinary tract infections, bone and joint infections, bacterial gastroenteritis, omphalitis, and cellulitis. They included 1060 children, of whom 127 (11.2%) were diagnosed with an SBI and 11 (1.0%) were diagnosed with an IBI. The median age of the included children was 17 months (IQR 6,6 to 24,3 months), and 52% of the children were boys. The authors reported the cut-offs 0.3, 0.5, 1.0 ng/mL for PCT, and the cut-offs 20 and 40 mg/L for CRP.

Gunduz (2018) performed a prospective cohort study investigating the diagnostic accuracy of PCT (cut-offs 0.58 and 2.0 ng/mL) and CRP (cut-offs 5.7, 20, and 40 mg/L) for SBI in children with fever without source. SBI was defined as sepsis, occult bacteremia, bacterial meningitis, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, or bacterial gastroenteritis. The authors included children aged 3 moths to 17 years who presented to pediatric outpatient clinics in Turkey. In total, 118 children were included, of whom 14 (12%) had an SBI. The mean age of the included children was 40.3 months (SD 40.4 months), and 56% were boys.

Han (2019) performed a retrospective cohort study investigating the diagnostic accuracy of PCT (cut-off 0.5 ng/mL) and CRP (cut-offs 16.74 and 20 mg/L) for SBI in with fever without source. SBI was defined as bacterial meningitis, bacteremia, or urinary tract infection (UTI) in which known pathogens were cultured. Children presenting to a pediatric ED in Korea between July 2016 and June 2018, aged between 29 and 90 days were included. In total, 199 children were included, of whom 68 (34%) were diagnosed with an SBI.

Lee (2018) performed a retrospective cohort study investigating the diagnostic accuracy of PCT (cut-off 0.5ng/mL) and CRP (cut-off 0.5 mg/dL) for SBI in with fever without source. SBI was defined as bacteremia with pathogenic causative organism grown in blood culture; bacterial meningitis with pathological causative organism grown in CSF culture; or UTI with pyuria (WBC>5/high power field) and a single pathologic agent grown to more than 100,000 colony-forming units/mL in urine collected in a urine bag. Children presenting to a pediatric ED or outpatient department in Korea between May 2015 and February 2017, aged between 1 and 3 months were included. The authors included 336 children of whom 38 (11%) had an SBI. The mean age of the included children was 59.5 days (SD 24.5), and 63% were boys.

Park (2021) performed a retrospective cohort study concerning the diagnostic value of PCT in predicting SBI compared to CRP in children aged less than 90 days old with a fever at a single institution pediatric emergency center. Children younger than 3 months of age who presented with fever at the Asan Medical Center pediatric emergency room between January 2017 to June 2018 were included. Cases being transferred to another hospital without examination, when full diagnostic testing was not performed or temporary hyperthermia patients who had exceeded 28 days of age, were in a good general condition, their fever did not exceed 38 °C, and it did not recur after spontaneous resolution without

antipyretics, were excluded. SBI was defined as the isolation of bacterial pathogens from the blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or fecal samples, or urine cultures at 100,000 CFUs/mL. Non-bacterial infection was defined as a case in which a bacterial culture test was negative but another infection such as a viral origin was suspected based on the medical history, and

the viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results obtained from each sample were considered. A total of 317 children were included in the analysis, from which 61 (19%) were diagnosed with an SBI. UTI was the most common diagnosis of SBI (55/61; 90%). Median age was 32.0 days (IQR 20.0-67.0) in the SBI group and 30.0 days (IQR 20.0-63.8) in the non-SBI group. In the SBI group, more children were male (75%), compared to the non-SBI group (58%; P=0.013).

Results

1. Procalcitonine

1.1 Serious bacterial infections (SBI)

1.1.1 Diagnostic accuracy: sensitivity and specificity

For PCT cut-off 0.5 ng/mL, Tripella (2017) reported a pooled sensitivity of 55% (95% CI 52 to 58) and a pooled specificity of 85% (95% CI 84 to 86) in detecting SBI from seven studies (Milcent, 2016; Markic, 2015; Nijman, 2014; Mahajan, 2014; Gomez, 2012; Olaciregui, 2009; Andreola, 2007) including 5357 children. For PCT cut-off 2.0 ng/mL, Tripella (2017) reported a pooled sensitivity of 30% (95% CI 27 to 34) and a pooled specificity of 95% (95% CI 94 to 95) for PCT (cut-off 2 ng/mL) in detecting SBI from four studies (Milcent, 2016; Nijman, 2014; Gomez, 2012; Olaciregui, 2009) including 4651 children.

Yo (2012) performed a subgroup analysis including studies with a PCT cut-off of 0.5ng/mL. They reported a pooled sensitivity of 78% (95% CI 68 to 85) and a pooled specificity of 72% (95% CI 59 to 82) for PCT (cut-off 0.5 ng/mL) in detecting SBI from five studies (Galetto-Lacour, 2003; Thayyil, 2005; Andreola, 2007; Olaciregui, 2009; Manzano, 2010) including 1310 children.

Hubert-Dibon (2018) reported a sensitivity 46% (95% CI 37 to 56) and a specificity of 75% (95% CI 71 to 78) for PCT (cut-off 0.5 ng/mL) in detecting SBI.

Lee (2018) reported a sensitivity of 44% (95% CI 28 to 60) and a specificity of 93% (95% CI 89-95) for PCT (cut-off 0.5ng/mL) in detecting SBI.

Han (2019) reported a sensitivity of 40% (95% CI 28 to 52) and a specificity of 98% (95% CI 94 to 100) for PCT (cut-off 0.5ng/mL) in detecting SBI.

In Park (2021), the sensitivity of PCT (cut-off value ≥0.3 ng/mL) in detecting SBI was 54.1 (95% CI not reported). The specificity was 87.5 (95% CI not reported).

1.2 Invasive bacterial infections (IBI)

1.2.1 Diagnostic accuracy: sensitivity and specificity

Tripella (2017) performed separate meta-analysis regarding the diagnostic accuracy of PCT in detecting IBI. They reported a pooled sensitivity of 82% (95% CI 73 to 90) and a pooled specificity of 86% (95% CI 85 to 87) in detecting IBI using PCT (cut-off 0.5 ng/mL) in five studies (Diaz, 2016; Milcent, 2016; Gomez, 2012; Luaces-Dubells, 2012; Olaciregui, 2009) including 4692 children. They reported a pooled sensitivity of 61% (95% CI 49 to 73) and a pooled specificity of 94% (95% CI 93 to 95) in detecting IBI using (cut-off 2 ng/mL) in four studies (Diaz, 2016; Milcent, 2016; Gomez, 2012; Luaces-Dubells, 2012) including 4345 children.

Hubert-Dibon (2018) reported a sensitivity of mL 82% (95% CI 48 to 97) and a specificity of 72% (95% CI 68 to 75) in detecting IBI using PCT (cut-off 0.5 ng/mL).

2. C-reactive protein (CRP)

2.1 Serious bacterial infections (SBI)

2.1.1 Diagnostic accuracy: sensitivity and specificity

Yo (2012) performed a subgroup analysis including studies with a cut-off for CPR of 40 ng/mL. The pooled sensitivity in four studies with a total of 846 children included (Lacour, 2001; Galetto-Lacour, 2003; Andreola, 2007; Guen, 2007) in detecting SBI with a CRP cut-off of 40 ng/mL was 74% (95% CI 58 to 85). The sensitivities reported in the individual studies were, respectively; 89%, 79%, 71%, and 43%. The pooled specificity was 76% (95% CI 68 to 82). The specificities reported in the individual studies were, respectively; 75%, 79%, 81%, and 65%.

Hubert-Dibon (2018) reported a sensitivity of 47% (95% CI 37 to 57) in detecting SBI in 1060 children using a CRP cut-off of 40 mg/L. The specificity was 82% (95% CI 77 to 85).

Gunduz (2018) reported a sensitivity of 36% (95% CI 13 to 65) and a specificity of 94% (95% CI 88 to 98) for CRP (cut-off 40 mg/L) in detecting SBI.

Han (2019) reported a sensitivity of 62% (95% CI 49 to 73) and a specificity of 88% (95% CI 81 to 93) for CRP (cut-off 20 mg/L) in detecting SBI.

In Park (2021), the sensitivity of CRP (cut-off value ≥20 mg/L) in detecting SBI was 49.2 (95% CI not reported). The specificity was 89.5 (95% CI not reported).

2.2 Invasive bacterial infections (IBI)

2.2.1 Diagnostic accuracy: sensitivity and specificity

Hubert-Dibon (2018) reported a sensitivity of 64% (95% CI 32 to 88) in detecting IBI in 1060 children using a CRP cut-off of 20 mg/L. The specificity was 62% (95% CI 58 to 65).

Hubert-Dibon (2018) reported a sensitivity of 64% (95% CI 32 to 88) in detecting IBI in 1060 children using a CRP cut-off of 40 mg/L. The specificity was 78% (95% CI 75 to 81).

3. Leukocytes (WBC)

3.1 Serious bacterial infections (SBI)

3.1.1 Diagnostic accuracy: sensitivity and specificity

Yo (2012) performed a subgroup analysis including studies with a cut-off for WBC of 15000/mm3. The pooled sensitivity in six studies with a total of 1241 children included (Lacour, 2001; Galetto-Lacour, 2003; Thayyil, 2005; Guen, 2007; Olaciregui, 2009; Manzano, 2010) for detecting SBI with a WBC cut-off of 15000/mm was 61% (95% CI 52 to 70). The sensitivities reported in the individual studies were, respectively; 68%, 52%, 50%, 63%, 59% and 71%. The pooled specificity was 72% (95% CI 65 to 77). The specificities reported in the individual studies were, respectively; 77%, 74%, 53%, 66%, 79% and 75% (figure 1).

In Park (2021), the sensitivity of WBC (cut-off value ≤5000 or ≥15,000/µL) in detecting SBI was 45.9 (95% CI not reported). The specificity was 69.1 (95% CI not reported).

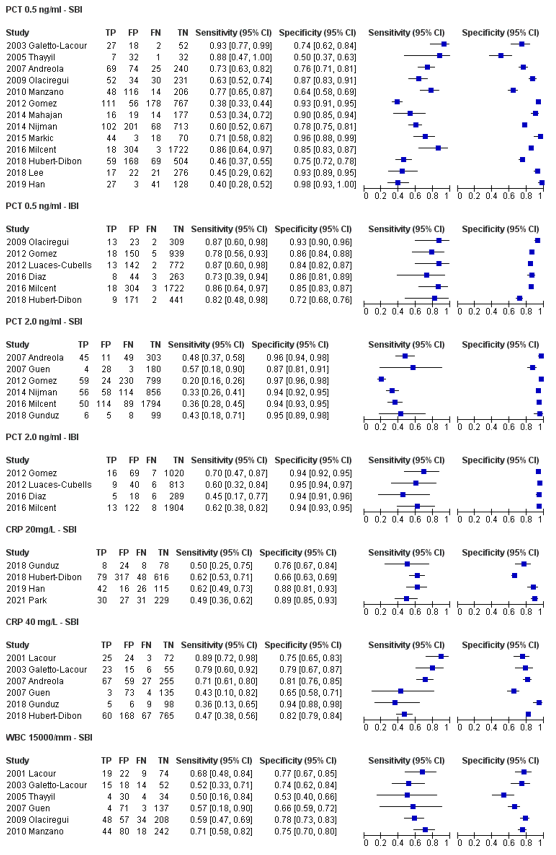

Figure 1. Sensitivity and specificity of PCT 0.5 ng/ml, PCT 2.0 ng/ml, CRP 20 mg/L, CRP 40 mg/L and WBC 15000/mm in detecting SBI and IBI

Figure 1. Sensitivity and specificity of PCT 0.5 ng/ml, PCT 2.0 ng/ml, CRP 20 mg/L, CRP 40 mg/L and WBC 15000/mm in detecting SBI and IBI

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding diagnostic accuracy of diagnosis serious or invasive bacterial infection started as high (diagnostic studies).

Sensitivity

The level of evidence regarding the outcome sensitivity of SBI for PCT and WBC was downgraded by two levels to GRADE low because of study limitations (risk of bias due to reference standard; unclear if results of reference test were independently assessed from results of index test) and inconsistent results (inconsistency).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome sensitivity of IBI for PCT was downgraded by one level to GRADE Moderate because of study limitations (risk of bias due to reference standard; unclear if results of reference test were independently assessed from results of index test).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome sensitivity of IBI for CRP was downgraded by two level to GRADE low because of study limitations (risk of bias due to reference standard; unclear if results of reference test were independently assessed from results of index test) and imprecision (low number of patients and broad confidence interval).

Specificity

The level of evidence regarding the outcome specificity of SBI for PCT was downgraded by two levels to GRADE Low because of study limitations (risk of bias due to reference standard; unclear if results of reference test were independently assessed from results of index test) and inconsistent results (inconsistency).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome specificity of IBI for WBC was downgraded by one level to GRADE Moderate because of study limitations (risk of bias due to reference standard; unclear if results of reference test were independently assessed from results of index test).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome specificity of IBI for CRP was downgraded by two level to GRADE low because of study limitations (risk of bias due to reference standard; unclear if results of reference test were independently assessed from results of index test) and imprecision (low number of patients and broad confidence interval).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the diagnostic accuracy of biomarkers (PCT, CRP, leukocytes) in diagnosing serious or invasive bacterial infection compared to anamnesis and physical examination in children (2 months to 16 years old) with fever visiting the emergency department?

P: Children (0-16 years) with fever visiting the emergency department, suspected of a serious or invasive bacterial infection

I: Procalcitonin (PCT)

C: Leucocytes, c-reactive protein (CRP)

R: Anamnesis and physical examination, blood culture

O: Diagnostic accuracy of diagnosis serious or invasive bacterial infection

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered sensitivity as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and specificity as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

A priori, the working group did not define a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for diagnostic accuracy outcomes.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until june 22, 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 654 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews or observational studies reporting the diagnostic accuracy of PCT in detecting SBI or IBI. Forty-nine studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 42 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 7 studies were included.

Results

Seven studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables. Tripella (2017), Yo (2012), and Hubert-Dibon (2018) were included in the guideline Sepsis bij kinderen (Biomarkers). For the current guideline the summary of literature, results, level of evidence of the literature, and conclusions regarding Tripella (2017), Yo (2012), and Hubert-Dibon (2018) were translated into English. The conclusions and level of evidence of the literature sections were updated after inclusion of more recent literature.

Referenties

- Gunduz, A., Tekin, M., Konca, C., & Turgut, M. (2018). Effectiveness of laboratory markers in determining serious bacterial infection in children with fever without source. Journal of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 13(04), 287-292.

- Han, S., Choi, S., & Cho, Y. S. (2019). Diagnostic markers of serious bacterial infections in infants aged 29 to 90 days. Signa vitae: journal for intesive ca

- Hubert?Dibon, G., Danjou, L., Feildel?Fournial, C., Vrignaud, B., Masson, D., Launay, E., & Gras?Le Guen, C. (2018). Procalcitonin and C?reactive protein may help to detect invasive bacterial infections in children who have fever without source. Acta Paediatrica, 107(7), 1262-1269.

- Lee, I. S., Park, Y. J., Jin, M. H., Park, J. Y., Lee, H. J., Kim, S. H., ... & Lee, J. H. (2018). Usefulness of the procalcitonin test in young febrile infants between 1 and 3 months of age. Korean journal of pediatrics, 61(9), 285.

- Park, J. S., Byun, Y. H., Lee, J. Y., Lee, J. S., Ryu, J. M., & Choi, S. J. (2021). Clinical utility of procalcitonin in febrile infants younger than 3 months of age visiting a pediatric emergency room: a retrospective single-center study. BMC pediatrics, 21(1), 1-9.

- Trippella, G., Galli, L., De Martino, M., Lisi, C., & Chiappini, E. (2017). Procalcitonin performance in detecting serious and invasive bacterial infections in children with fever without apparent source: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert review of anti-infective therapy, 15(11), 1041-1057.

- van Houten, C. B., de Groot, J. A. H., Klein, A., Srugo, I., Chistyakov, I., de Waal, W., Meijssen, C. B., Avis, W., Wolfs, T. F. W., Shachor-Meyouhas, Y., Stein, M., Sanders, E. A. M., & Bont, L. J. (2017). A host-protein based assay to differentiate between bacterial and viral infections in preschool children (OPPORTUNITY): a double-blind, multicentre, validation study. The Lancet. Infectious diseases, 17(4), 431-440. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30519-9

- Yo, C. H., Hsieh, P. S., Lee, S. H., Wu, J. Y., Chang, S. S., Tasi, K. C., & Lee, C. C. (2012). Comparison of the test characteristics of procalcitonin to C-reactive protein and leukocytosis for the detection of serious bacterial infections in children presenting with fever without source: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of emergency medicine, 60(5), 591-600.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics

|

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Gunduz, 2018 |

Type of study[1]: prospective cohort

Setting and country: pediatric outpatient clinics, Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: authors report no funding and no conflict of interest |

Inclusion criteria: - age 3 months to 17 years - presenting with fever - good appearance - no focus of fever determined through history or physical examination

Exclusion criteria: - focus of infection identified through history and physical examination - toxic appearance - fever persisting for longer than 7 days - antibiotic therapy for longer than 48 hours - vaccinated within the previous 5 days - history of congenital or acquired immune deficiency - chronic disease - history of recurring urinary tract infection or urinary system anomaly - steroid or immunosuppressive therapy

N= 118

Prevalence of IBI: not reported Prevalence of SBI: 14 of 118 (12%)

Mean age ± SD: 40.3 ± 40.4 months

Sex: 56% M / 44% F

Other important characteristics: Mean temperature SBI: 39.3 ± 0.4°C non-SBI: 39.1 ± 0.5°C

|

Describe index test: PCT

Cut-off point(s): ≥ 0.58 ng/mL ≥ 2 ng/mL

Comparator test[2]: CRP

Cut-off point(s): > 0.57 mg/dL > 2 mg/dL > 4 mg/dL

|

Describe reference test[3]:

SBI was defined as a diagnosis of sepsis, occult bacteremia, bacterial meningitis, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, or bacterial gastroenteritis

Cut-off point(s):

|

Time between the index test and reference test: not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N 17 (13%)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Laboratory results unavailable: 8 Blood culture not performed or results unavailable: 5 Contaminated blood cultures: 4 |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available)4:

IBI Not reported

SBI PCT cut-off 0.58 ng/mL sensitivity / specificity (%) 93 / 90

PCT cut-off 2.0 ng/mL sensitivity / specificity (%) 43 / 95

CRP cut-off >0.57 mg/dL sensitivity / specificity (%) 93 / 51

CRP cut-off >2 mg/dL sensitivity / specificity (%) 50 / 77

CRP cut-off >4 mg/dL sensitivity / specificity (%) 36 / 94 |

IBI = invasive bacterial infection SBI = serious bacterial infection |

|

Han, 2019 |

Type of study: retrospective cohort

Setting and country: pediatric emergency department, Korea

Funding and conflicts of interest: supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund. Conflicts of interest not mentioned. |

Inclusion criteria: - Presentation between July 2016 and June 2018 - age 29 to 90 days - fever > 38°C at home or on admission

Exclusion criteria: - antibiotics 48 hours before visiting the hospital - major underlying disease such as immune deficiency, congenital abnormality, or chronic disease - preterm Infants

N=234 (199 with full dataset)

Prevalence: 68 of 199 (34%)

Age in days (unclear if mean or median, range): 62.0 (44.0-79.0)

Sex: % M / % F Not reported

Other important characteristics: Body temperature SBI: 38.25 (37.82-38.80) Non-SBI: 38.20 (37.80-38.70) unclear if mean or median, range

|

Describe index test: PCT

Cut-off point(s): > 0.5 ng/mL > 1 ng/mL

Comparator test: CRP

Cut-off point(s): > 16.74 mg/L > 20 mg/L |

Describe reference test: SBI, defined as bacterial meningitis, bacteremia, or urinary tract infection (UTI) in which known pathogens were cultured.

Cut-off point(s):

|

Time between the index test and reference test: not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N 35 (15%)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Contaminated culture: 35 |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

IBI Not reported

SBI PCT cut-off 0.5 ng/mL sensitivity / specificity (%) 40 / 98

PCT cut-off 1.0 ng/mL sensitivity / specificity (%) 35 / 99

CRP cut-off >16.74 mg/L sensitivity / specificity (%) 66 / 85

CRP cut-off >20 mg/L sensitivity / specificity (%) 62 / 88 |

|

|

Hubert-Dibon, 2018 |

Type of study: prospective cohort

Setting and country: pediatric emergency department, France

Funding and conflicts of interest: authors report no funding and no conflict of interest |

Inclusion criteria: - age >6 days, <5 years - presenting with a FWS ≥38°C at home and/or at the PED, measured in a suitable way with axillary or rectal temperature.

Exclusion criteria: - Fever not measured or below 38°C - origin of fever identified - parents refuse to participate

N= 1060

Prevalence: SBI: 127 of 1060 (12%) IBI: 11 of 1060 (1%)

Mean age ± SD: Not reported

Sex: 52% M / 48% F

Other important characteristics:

|

Describe index test: PCT

Cut-off point(s): ≥ 0.3 ng/mL ≥ 0.5 ng/mL ≥ 1 ng/mL

Comparator test: CRP

Cut-off point(s): ≥ 20 mg/L ≥ 40 mg/L |

Describe reference test:

IBI, defined as the isolation of a pathogenic bacterium from the blood or cerebrospinal fluid.

SBI included invasive bacterial infections, urinary tract infection, bone and joint infections, bacterial gastroenteritis, omphalitis and cellulitis with negative cultures.

Cut-off point(s):

|

Time between the index test and reference test: not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N 0 (%)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

IBI PCT cut-off ≥ 0.3 ng/mL sensitivity / specificity (%) 82 / 62

PCT cut-off ≥ 0.5 ng/mL sensitivity / specificity (%) 82 / 72

PCT cut-off ≥ 1.0 ng/mL sensitivity / specificity (%) 82 / 82

CRP cut-off ≥ 20 mg/L sensitivity / specificity (%) 64 / 62

CRP cut-off ≥ 40 mg/L sensitivity / specificity (%) 64 / 78

SBI PCT cut-off ≥ 0.3 ng/mL sensitivity / specificity (%) 60 / 66

PCT cut-off ≥ 0.5 ng/mL sensitivity / specificity (%) 46 / 75

PCT cut-off 1.0 ng/mL sensitivity / specificity (%) 32 / 83

CRP cut-off ≥ 20 mg/L sensitivity / specificity (%) 62 / 66

CRP cut-off ≥ 40 mg/L sensitivity / specificity (%) 47 / 82 |

|

|

Lee, 2018 |

Type of study: retrospective cohort

Setting and country: pediatric emergency department, Korea

Funding and conflicts of interest: funding not reported. Authors report no conflicts of interest |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N= 336

Prevalence of SBI: 38 of 336 (11%)

Mean age ± SD: Total: 59.5 ± 24.5 days SBI: 68.1 ± 22.5 days Non-SBI: 58.4 ± 24.6 days P=0.015

Sex: 63% M / 37% F

Other important characteristics:

|

Describe index test: PCT

Cut-off point(s): 0.5 ng/mL

Comparator test: CRP

Cut-off point(s): 0.5 mg/dL |

Describe reference test: SBI group was defined as (1) bacteremia with pathogenic causative organism grown in blood culture; (2) bacterial meningitis with pathological causative organism grown in CSF culture; or (3) UTI with pyuria (WBC>5/high power field) and a single pathologic agent grown to more than 100,000 colony-forming units/mL in urine collected in a urine bag. Meningitis was defined as the meningism without altered consciousness, with CSF WBC ≥5/μL)

Cut-off point(s):

|

Time between the index test and reference test:

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

IBI Not reported

SBI PCT cut-off 0.5 ng/mL sensitivity / specificity (%) 44 / 93

CRP cut-off 0.5 mg/dL sensitivity / specificity (%) 92 / 25

|

|

|

Park, 2021 |

Type of study: retrospective study

Setting and country: Pediatric Emergency Room, Korea

Funding and conflicts of interest: no funding, no conflicts of interest reported |

Inclusion criteria: medical records of patients <3 months of age, who presented with fever at the Asan Medical Center pediatric emergency room between January 2017 to June 2018.

Exclusion criteria: cases transferred to another hospital without examination, when full diagnostic testing was not performed, or temporary hyperthermia patients who had exceeded 28 days of age, were in a good general condition, their fever did not exceed 38 °C, and it did not recur after spontaneous resolution without antipyretics.

N=317

Prevalence of SBI: 61 (55 UTI) of 317 (19%)

Mean age (range): SBI-group: 32.0 (20.0-67.0) days Non-SBI-group: 30.0 (20.0-63.8) days

Sex: % M / % F SBI-group: 75% Non-SBI-group: 58% P=0.013

|

Describe index test: PCT (Enzyme-Linked Fluorescent Assay using an ADVIA Centaur® BRAHMS PCT assay (ADVIA Centaur XPT, Siemens)

Cut-off point(s): ≥0.3 ng/mL (derived from the maximum value of Youden’s index using the ROC curve analysis, where it had the most similar sensitivity/ specificity to the existing classification criteria)

Comparator test 1: CRP (latex agglutination assay using CRPL3, Roche (Cobas 8000, Roche))

Cut-off point: 2.0 mg/dL

Comparator test 2: WBC

Cut-off point: ≥ 15,000/μL |

Describe reference test: Blood culture: isolation of bacterial pathogens from the blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or fecal samples, or urine cultures at 100,000 CFUs/mL.

Cut-off point(s):

|

Time between the index test and reference test: Not reported (collected from medical records and laboratory tests)

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? 0 (0%): only those with full diagnostic testing were included

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

IBI Not reported

SBI PCT cut-off ≥0.3 ng/mL Sensitivity / specificity (%) 54.1 / 87.5

PPV / NPV (%) 50.8 / 88.9

CRP cut-off ≥2.0 mg/dL Sensitivity / specificity (%) 49.2 / 89.5

PPV / NPV (%) 52.6 / 88.1

WBC cut-off ≤5000 and ≥15000/µL Sensitivity / specificity (%) 45.9 / 69.1

PPV / NPV (%) 26.2 / 84.3

Combination PCT, CRP and WBC Sensitivity / specificity (%) 80.3 / 55.5

PPV / NPV (%) 30.1 / 92.2

|

|

[1] In geval van een case-control design moeten de patiëntkarakteristieken per groep (cases en controls) worden uitgewerkt. NB; case control studies zullen de accuratesse overschatten (Lijmer et al., 1999)

[2] Comparator test is vergelijkbaar met de C uit de PICO van een interventievraag. Er kunnen ook meerdere tests worden vergeleken. Voeg die toe als comparator test 2 etc. Let op: de comparator test kan nooit de referentiestandaard zijn.

[3] De referentiestandaard is de test waarmee definitief wordt aangetoond of iemand al dan niet ziek is. Idealiter is de referentiestandaard de Gouden standaard (100% sensitief en 100% specifiek). Let op! dit is niet de “comparison test/index 2”.

4 Beschrijf de statistische parameters voor de vergelijking van de indextest(en) met de referentietest, en voor de vergelijking tussen de indextesten onderling (als er twee of meer indextesten worden vergeleken).

|

Study reference |

Patient selection

|

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Gunduz, 2018 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Unclear

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? No

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Unclear

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Unclear

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Unclear

Were all patients included in the analysis? No

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

||

|

Han, 2019 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Unclear

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Unclear

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Unclear

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Unclear

Were all patients included in the analysis? No |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

Hubert-Dibon, 2018 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? No

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Unclear

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Unclear

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Unclear

Were all patients included in the analysis? No

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

Lee, 2018 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Unclear

Was a case-control design avoided? Unclear

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Unclear

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Unclear

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Unclear

Were all patients included in the analysis? Unclear

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

||

|

Park, 2021 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Unclear

Was a case-control design avoided? Unclear

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Unclear

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Unclear

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Unclear

Were all patients included in the analysis? No |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Thompson, 2012 |

All included studies also included in more recent SRs |

|

Kupperman, 2019 |

2 by 2, sensitivity and specificity not reported per variable |

|

Ramgopal, 2020 |

Wrong study design: developing and validation of prediction model using machine learning approaches, whereby PCT was part of the model |

|

Hu, 2017 |

2 by 2, sensitivity and specificity not reported per variable |

|

Markic, 2015 |

In Tripella |

|

Lucaces-Cubells, 2012 |

In Tripella |

|

Kim, 2021 |

Wrong P: not fever without source (suspected meningitis) |

|

England, 2014 |

All included studies also included in more recent SRs |

|

Yoon, 2019 |

Wrong P: not fever without source (sepsis, healthy controls or sepsis and "non-sepsis patients"). Wrong I/C combination |

|

Rangelov, 2021 |

Wrong P: children with suspected sepsis |

|

Gomez, 2012 |

In Tripella |

|

Diaz, 2016 |

In Tripella |

|

Velasco, 2017 |

Wrong P: Febrile infants ≤90 days old with altered urinalysis |

|

Gomez, 2016 |

2 by 2, sensitivity and specificity not reported per variable |

|

Irwin, 2017 |

2 by 2, sensitivity and specificity not reported per variable |

|

Nijman, 2014 |

In Tripella |

|

Waterfield, 2020 |

Wrong P: children with features of possible meningitis and/or sepsis |

|

Waterfield, 2018 |

Wrong P: Any child under 90 days of age presenting with signs or symptoms suggestive of possible bacterial infection |

|

Mahajan, 2014 |

In Tripella |

|

Leroy, 2018 |

2 by 2, sensitivity and specificity not reported per variable |

|

Milcent, 2016 |

In Tripella |

|

Nijman, 2018 |

2 by 2, sensitivity and specificity not reported per variable |

|

Demir, 2020 |

2 by 2, sensitivity and specificity not reported per variable |

|

Topuz, 2012 |

Wrong P: suspicion of neonatal septicemia |

|

Alaaraji, 2020 |

DOI not found |

|

Hui, 2012 |

Included studies also included in Tripella |

|

Velasco, 2020 |

Wrong P: abnormal urine dipstick |

|

Velasco, 2015 |

Wrong P: abnormal urine dipstick |

|

Pourakbari, 2010 |

2 by 2, sensitivity and specificity not reported per variable |

|

Tripella, 2018 |

All included studies also included in Tripella 2017 |

|

Pontrelli, 2017 |

Wrong P: suspicion of sepsis |

|

Mintegi, 2014 |

2 by 2, sensitivity and specificity not reported per variable |

|

Bressan, 2012 |

2 by 2, sensitivity and specificity not reported per variable |

|

Kelly, 2021 |

Wrong P: possible MIS-C |

|

Villalobos, 2017 |

In spanish |

|

Woelker, 2012 |

In Tripella |

|

Gomez, 2019 |

2 by 2, sensitivity and specificity not reported per variable |

|

Nesa, 2020 |

Wrong P: suspected neonatal sepsis |

|

Bozlu, 2018 |

Wrong setting: intensive care unit |

|

Freund, 2012 |

Wrong P: 15 years or older |

|

Eckerle, 2016 |

Wrong P: patients for whom cultures of blood, urine and/or cerebrospinal fluid were ordered |

|

Vachani, 2017 |

Narrative review |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 13-03-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kinderen met koorts op de Spoedeisende Hulp.

Werkgroep

- Dr. R. (Rianne) Oostenbrink, kinderarts, werkzaam in het ErasmusMC te Rotterdam, NVK (voorzitter)

- Dr. E.P. (Emmeline) Buddingh, kinderarts- infectioloog/immunoloog, werkzaam in het LUMC te Leiden, NVK

- Drs. J. (Joël) Israëls, kinderarts/pulmonoloog, werkzaam in het LUMC te Leiden, NVK

- Dr. A.E. (Anna) Westra, algemeen kinderarts, werkzaam in het Flevoziekenhuis te Almere, NVK

- Drs. E.P.M. (Erika) van Elzakker, arts-microbioloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVMM

- Dr. M.R.A. (Matthijs) Welkers, arts-microbioloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVMM, vanaf 25-04-2022

- Dr. C.R.B. (Christian) Ramakers, laboratoriumspecialist Klinische Chemie, werkzaam in het ErasmusMC te Rotterdam, NVKC

- Dr. G. (Jorgos) Alexandridis, spoedeisende hulp-arts, werkzaam in het Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland te Rotterdam, NVSHA

- Drs. K.M.A. (Karlijn) Meys, kinderradioloog, werkzaam in het UMC Utrecht te Utrecht, NVvR

- Dr. E (Eefje) de Bont, Huisarts, NHG

- I.J.M. (Ingrid) Vonk, verpleegkundig specialist, werkzaam in het Maasstad ziekenhuis te Rotterdam, V&VN

Klankbordgroep

- R. (Rowy) Uitzinger, junior projectmanager en beleidsmedewerker, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis, tot 01-06-2022

- E. (Esen) Doganer, junior projectmanager en beleidsmedewerker, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis, vanaf 01-06-2022

- Dr. A. (Annelies) Riezebos-Brilman, arts-microbioloog, werkzaam in het UMC Utrecht te Utrecht, NVMM, tot 25-04-2022

Met ondersteuning van:

- Dr. J. (Janneke) Hoogervorst – Schilp, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. M. (Mattias) Göthlin, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. T. (Tim) Christen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- M. (Miriam) van der Maten, MSc, junior medisch informatiespecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Tabel 1: Samenstelling van de werkgroep

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Werkgroep |

||||

|

* Voorzitter werkgroep Oostenbrink |

Kinderarts afd. algemene kindergeneeskunde Erasmusmc Rotterdam |

onbetaald: Member PEM-NL network |

Als wetenschapper betrokken bij de ontwikkeling en toepassing van de feverkidstool, predictie model voor kinderen met koorts, zonder financiele belangen.

|

Geen actie |

|

Buddingh |

Kinderarts infectioloog/ |

SWABID kinderen kerngroeplid (onbetaald) |

Principle investigator landelijke studie naar COVID-19 en MIS-C bij kinderen (COPP-studie, www.covidkids.nl)

|

Geen actie |

|

Israëls |

Kinderarts/pulmonoloog LUMC, Leiden |

APLS instructeur bij Stichting Spoedeisende hulp bij kinderen (onkostenvergoeding) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Vonk |

Maasstad Ziekenhuis |

Columnist Magazine Kinderverpleegkunde (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Alexandridis |

AIOS SEH te Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland |

APLS instructeur bij Stichting SHK (onkostenvergoeding) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Westra |

Algemeen Kinderarts Flevoziekenhuis / De Kinderkliniek Almere |

Lid NVK expertisegroep acute kindergeneeskunde, onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Ramakers |

Laboratoriumspecialist klinische chemie |

ISO 15189 vakdeskundige klinische chemie, Raad van Accreditatie, betaald. |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

van Elzakker |

Tot mei 2021: Arts-microbioloog HagaZiekenhuis en Juliana Kinderziekenhuis Den Haag, aandachtsgebied infecties bij kinderen Mei 2021-heden: arts-microbioloog AUMC, aandachtsgebied bacteriologie, infecties bij kinderen. |

Tot mei 2021 Auditor Raad voor Accreditatie (vakdeskundige) (betaald). Docent cursus antibiotica bij kinderen (betaald).

|

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

de Bont |

Zelfstandig Huisarts 0.6 FTE |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Welkers |

Arts-microbioloog, AmsterdamUMC 0,5 FTE) en GGD streeklaboratorium Amsterdam (0,5 FTE). 100% in dienst bij AmsterdamUMC en 0,5FTE gedetacheerd naar GGD streeklaboratorium. |

|

|

|

|

Klankbordgroep |

||||

|

Riezebos-Brilman |

Arts-microbioloog met aandachtsgebied virologie UMCU |

Voorzitter Richtlijn behandeling influenza (NVMM) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Uitzinger |

Junior projectmanager en beleidsmedewerker |

geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Doganer |

Junior projectmanager en beleidsmedewerker |

geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis uit te nodigen voor de klankbordgroep en voor de knelpunteninventarisatie. Het verslag van de knelpunteninventarisatie is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Aanvullende diagnostiek: PCT |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor kinderen met koorts op de Spoedeisende Hulp. Tevens was er mogelijkheid om knelpunten aan te dragen via een schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie. Een overzicht van de binnengekomen reacties is opgenomen in de bijlagen.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Prognostisch onderzoek: studiedesign en hiërarchie

Bij het beoordelen van literatuur is er een hiërarchie in de kwaliteit van individuele studies. Bij voorkeur wordt de effectiviteit van een klinisch beslismodel geëvalueerd in een klinische trial. Helaas zijn deze studies zeer zeldzaam. Indien niet beschikbaar, hebben studies waarin voorspellingsmodellen worden ontwikkeld en gevalideerd in andere samples van de doelpopulatie (externe validatie) de voorkeur aangezien er meer vertrouwen is in de resultaten van deze studies in vergelijking met studies die niet extern gevalideerd zijn. De meeste samples geven de karakteristieken van de totale populatie niet volledig weer, wat resulteert in afwijkende associaties, die mogelijk gevolgen hebben voor conclusies die getrokken worden. Studies die voorspellingsmodellen intern valideren (bijvoorbeeld door middel van bootstrapping of kruisvalidatie) kunnen ook worden gebruikt om de onderzoeksvraag te beantwoorden, maar het verlagen van het bewijsniveau ligt voor de hand vanwege het risico op bias en/of indirectheid, aangezien het niet duidelijk is of modellen voldoende presteren bij doelpopulaties. Het vertrouwen in de resultaten van niet-gevalideerde voorspellingsmodellen is erg laag. Over het algemeen leidt dit tot geen GRADE of Zeer lage GRADE. Dit geldt ook voor associatiemodellen. De risicofactoren die uit dergelijke modellen worden geïdentificeerd, kunnen worden gebruikt om patiënten of ouders te informeren over de inschatting van het risico op ernstige bacteriëmie, bacteriële meningitis of urineweginfectie, maar ze zijn minder geschikt om te gebruiken bij klinische besluitvorming.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.