Prognostische factoren ernstige bacteriële infectie

Uitgangsvraag

1. Welke (combinatie van) anamnestische gegevens en symptomen bij het lichamelijk onderzoek zijn geassocieerd met een verhoogd risico op de aanwezigheid van een ernstige bacteriële infectie bij kinderen met koorts op de SEH?

2. Welk predictiemodel kan het beste gebruikt worden om de kans op ernstige bacteriële infecties (op basis van klinische kenmerken en aanvullende diagnostiek) bij kinderen met koorts op een SEH te voorspellen?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik een vaste structuur om op basis van de klinische symptomen van het kind in te schatten hoe groot de kans is op een ernstige bacteriële infectie. De ‘NICE stoplichttabel’ is hier een bruikbare benadering voor.

Overweeg daarnaast het gebruik van een predictiemodel om aan de hand van symptomen en laboratoriumwaarden van het kind in te schatten hoe groot de kans is op een ernstige bacteriële infectie. Bruikbare modellen zijn o.a.de Step-by-Step Approach to Febrile Infants bij kinderen ≤3 maanden, om laag risico kinderen te identificeren (Mintegi, 2014), De Lab-score bij kinderen < 12 maanden (Galetto-Lacour, 2010) of de Feverkidstool (Nijman, 2013). Besef dat geen enkel model sluitend is en dat daarom bij kinderen die als laag-risico worden geclassificeerd, een plan voor eventuele klinische observatie of herbeoordeling moet worden opgesteld.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Enkele studies onderzochten predictoren voor ernstige bacteriële infecties (SBI’s) in een multivariaat model. Doordat deze studies verschillende uitkomstmaten gebruikten, zijn de resultaten apart gerapporteerd voor urineweginfecties (UWI’s), pneumonie, IBI en totale SBI. Een aantal factoren lijkt in de studies geassocieerd met een verhoogd of juist verlaagd risico op deze uitkomstmaten. In studies die rapporteerden over totale SBI is het goed om te bedenken dat ook in die groep de diagnoses pneumonie en UWI de verre meerderheid van de SBI betroffen. De aard van de predictoren komt daardoor redelijk overeen.

De volgende factoren lijken predictoren te zijn voor UWI’s bij kinderen jonger dan 5 jaar oud die zich met koorts op de afdeling spoedeisende hulp melden: langere ziekteduur, zieke indruk, het hebben van een chronische ziekte, huilen, heet aanvoelen, koude rillingen, verminderde intake, verhoogde hartslag, niet-ingeënt zijn voor meningokokken, zeer hoge lichaamstemperatuur en koorts voor meer dan 2 dagen. De volgende factoren lijken het risico op een UWI juist te verlagen: luchtwegsymptomen, diarree, hoesten, abnormale keel, neus en oorsymptomen, mannelijk geslacht, focale bacteriële infectie, infectiecontact en rash.

De volgende factoren lijken predictoren te zijn voor pneumonie bij kinderen van 1 maand tot 16 jaar oud die zich met koorts op de afdeling spoedeisende hulp melden: langere ziekteduur/duur van koorts, zieke indruk, ademhalingsmoeilijkheden, lage zuurstofverzadiging, het hebben van een chronische ziekte, hoesten, gekraak op de borst, abnormaal borstgeluid, verhoogde hartslag, verhoogde ademhalingsfrequentie, niet-ingeënt zijn voor pneumokokken, zeer hoge lichaamstemperatuur en CRP. De volgende factoren maken pneumonie juist minder waarschijnlijk: abnormale keel, neus en oorsymptomen, huiduitslag en hoorbare piepende ademhaling.

Vrouwelijk geslacht en CRP lijken predictoren te zijn voor totale SBI bij kinderen jonger dan 5 jaar oud die zich met koorts op de afdeling spoedeisende hulp melden.

Een goed uitgevoerde RCT (de Vos-Kerkhof, 2015), zij het met een laag aantal events, laat zien dat het gebruiken van het beschreven klinische predictiemodel, de zgn. Feverkidstool (Nijman, 2013) bij het beslissen wel of niet diagnostisch onderzoek uit te voeren leidt tot een gestandaardiseerde benadering, met vergelijkbare diagnostische accuratesse tov de reguliere zorg van het diagnosticeren van ernstige bacteriële infecties in kinderen onder 16 jaar oud die zich met koorts op de afdeling spoedeisende hulp melden. De bewijskracht hiervoor is redelijk. Met deze studie is de bewijskracht voor de onderzochte beslisregel niveau 4 volgens Reilly (2006), namelijk impact analyse in 1 setting na brede cross validatie.

Enkele studies onderzochten de diagnostische accuratesse van verschillende klinische predictiemodellen voor SBI’s. De Lab-score (Galetto-Lacour, 2010), gebaseerd op de factoren urineanalyse, PCT en CRP, en het predictiemodel van Bachur en Harper (2001), gebaseerd op leeftijd, temperatuur, urineanalyse en WBC resulteerden in de laagste post-test kans op SBI bij een negatieve test en de hoogste post-test kans op SBI bij een positieve test. De lab-score heeft een aangetoond consistente diagnostische waarde in een prospectieve nieuwe populatie (niveau 3 volgens Reilly (2006)). De bewijskracht hiervoor is redelijk.

De NICE-stoplichttabel en NHG-alarmsymptomen zijn gerapporteerd in een low-event validatieonderzoek (Kerkhof, 2014). Geen van de beide kon een statistisch significant verhoogde of verlaagde kans op SBI laten zien.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Wij hebben de waarden voorkeuren van patiënten niet onderzocht. Het is echter aannemelijk dat het voor ouders met name belangrijk is dat goed wordt gekeken naar hun individuele kind, en dat de zorgen van de ouders daarbij serieus worden genomen. Wij hebben geen bewijs gevonden voor het gebruik van het alarmsymptoom “bezorgdheid van ouders” op de SEH; dit kenmerk is daarom niet als zodanig terug te vinden in de aanbevelingen. Wel is de werkgroep van mening dat bezorgdheid van de ouders, in de betekenis dat de ziekte “anders is dan anders”, serieus genomen dient te worden. Ook in het Dutch PEWS systeem wordt dit als factor meegenomen (Fuijkschot, 2015).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De ervaring leert dat artsen bij kinderen met koorts zonder focus relatief vaak geneigd zijn diagnostiek in te zetten en/of te kiezen voor opname, al dan niet met antibiotica. Dit uit angst om ernstige bacteriële infecties te missen. Daar waar het gebruik van data en modellen kan helpen om deze middelen gerichter in te zetten, zal dit dus eerder leiden tot een afname dan een toename van de kosten. Hierbij dient te worden opgemerkt dat kosten van diagnostiek gemiddeld slechts 1-3% van de totale kosten van beoordeling en behandeling van kinderen met koorts betreffen (Kerkhof, 2014; Van de Maat, 2020), dus effecten op kosten door blijven beperkt.

Indien predictiemodellen worden aanbevolen waarin het standaard gebruik van relatief dure biomarkers zoals procalcitonine is opgenomen, zou dit wel de zorgkosten enkele procenten van de totale kosten kunnen doen toenemen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De beschreven modellen zijn nog niet allemaal vrij beschikbaar als app of andere praktische tool. Om een model te kunnen implementeren wat een berekening bevat (versus een checklist), moet het model wel op enige wijze beschikbaar zijn.

In de lab-score is een procalcitonine bepaling opgenomen. Deze bepaling is momenteel in veel ziekenhuizen nog niet beschikbaar.

In enkele modellen is het neutrofielen getal opgenomen. In kleinere ziekenhuizen kan het zijn dat een leucocyten differentiatie alleen onder kantooruren wordt uitgevoerd.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Voor deze module was de werkgroep op zoek naar handvatten om uit de groep met kinderen die zich op de SEH presenteren met koorts zonder focus, die kinderen te identificeren die een verhoogd risico hebben op de aanwezigheid van een ernstige bacteriële infectie. Eerst is gekeken naar de voorspellende waarde van individuele symptomen (anamnestische gegevens en/of bevindingen bij het lichamelijk onderzoek). Helaas blijkt de vraag welke individuele symptomen geassocieerd zijn met een verhoogd risico op een ernstige bacteriële infectie, indien er nog geen verdenking is op een specifieke infectie, erg lastig te beantwoorden. Enerzijds omdat er vele symptomen zijn die potentieel geassocieerd zijn met een verhoogd risico op een ernstige bacteriële infectie. Anderzijds zou ook mee kunnen spelen dat er verschillende soorten ernstige bacteriële infecties bestaan, waarbij de mate van ziek zijn behoorlijk uiteen kan lopen. Hierdoor konden wij enkel symptomen beschrijven die zijn geassocieerd met een verhoogd of juist verlaagd risico op UWI of pneumonie. Ook bij studies die zich hebben gericht op total SBI nemen deze 2 ziektebeelden een grote plaats in. Op de vraag bij welke individuele symptomen je aan een ernstige bacteriële infectie moet denken, op het moment dat je nog niet een specifieke infectie in gedachten hebt, heeft de werkgroep geen duidelijk antwoord gevonden in de literatuur.

In de literatuur analyse is tevens gezocht naar predictiemodellen die de kans op ernstige bacteriële infecties voorspellen. Er zijn veel modellen beschikbaar, elk met eigen karakteristieken: niet alleen de kenmerken die mee worden gewogen, maar ook de leeftijdsgroep waar het voor is ontwikkeld, de wijze waarop de uitkomstmaat is gedefinieerd, en of het een dichotoom of continue model betreft. Zie appendix tabel 1 (Table 1. Included models and predictor variables) voor het overzicht van alle beschreven modellen. De werkgroep beschouwt een hoge sensitiviteit (laag aantal fout-negatieve uitslagen) als een belangrijk kenmerk van een goed predictiemodel voor koorts zonder focus op de SEH. Dit omdat het erg gevaarlijk kan zijn om een kind onterecht als laag-risico patiënt te beschouwen. Uiteraard is het model ook van weinig toegevoegde waarde als er sprake is van een lage specificiteit: indien veel kinderen onterecht als hoog risico worden gezien dan zal dit leiden tot onnodige over-diagnostiek en -behandeling. Een aanvullend criterium voor de bewijslast van de predictiemodellen is het niveau van evaluatie op de trap van 5 (Reilly, 2006): 1) derivatie, 2) validatie in 1 setting, 3) brede validatie in meer settings, 4) impact analyse in 1 setting en 5) brede impact analyse in meer settings.

Geen van de modellen had dusdanig overtuigende resultaten dat een sterke aanbeveling op zijn plek lijkt. Er zijn meerdere modellen beschikbaar die bewezen ondersteunend kunnen zijn in het proces, maar slechts een beperkt aantal daarvan heeft een hoog niveau van evaluatie op basis van brede cross validatie of impact analyse.

De modellen die de beste resultaten laten zien zijn modellen die ook laboratorium waarden bevatten; er is geen overtuigend model gevonden dat enkel uit symptomen bestaat. Vooral bij kinderen jonger dan 3 maanden lijkt een laboratoriumwaarde de kracht van het model te vergroten (De Vos-Kerkhof 2018). Dit wordt ook bevestigd door een studie van Kuppermann (2019), die een normale urine dipstick en laag procalcitonine en neutrofielen in het bloed als belangrijke voorspellers voor afwezigheid van meningitis, bacteriemie of urineweginfectie identificeert. Deze studie is op basis van design (analysemethoden en het ontbreken van de voorspellende waarde van de onafhankelijke predictoren) geexcludeerd bij de literatuurselectie. Echter qua bewijslast (grote populatie van bijna 200 zuigelingen <60 dagen) is de studie noemenswaardig. De werkgroep is van mening dat het belangrijk is om ook voordat laboratoriumwaarden bekend zijn, een onderbouwde inschatting te kunnen maken van de kans op een ernstige infectie. Enerzijds omdat bij evidente hoog-risico kinderen zo snel mogelijk antibiotica moet worden gestart. Anderzijds omdat bij wat oudere kinderen met enkel laag-risico symptomen, soms juist kan worden afgezien van laboratoriumonderzoek. Daarnaast moet men zich realiseren dat de meeste predictiemodellen vrij beperkt zijn en verre van waterdicht, waardoor het van toegevoegde waarde kan zijn om bij een patiënt op verschillende manieren een inschatting te maken van de kans op een ernstige bacteriële infectie.

In de vorige versie van deze richtlijn, alsmede in de NICE richtlijn, wordt geadviseerd om gebruik te maken van de NICE stoplichttabel. Deze stoplichttabel bevat slechts een overzicht van losse individuele kenmerken en kan daarmee beter als een gestandaardiseerde checklist dan als een predictiemodel worden beschouwd. In de literatuuranalyse kon de waarde van dit model dan ook niet goed worden aangetoond. Desondanks zou de werkgroep het als een gemis zien als deze tabel uit de richtlijn zou verdwijnen. Als gestandaardiseerde checklist is de tabel de afgelopen jaren in de praktijk wel degelijk van toegevoegde waarde gebleken. Vandaar dat de werkgroep dit model toch opnieuw in de aanbevelingen opneemt. Daarbij zijn de beschreven lijsten met symptomen die zijn geassocieerd met een verhoogd risico op UWI of pneumonie, naast de NICE stoplichttabel gelegd. Hetzelfde is gedaan met de symptomen die in de verschillende modellen werden meegenomen. De werkgroep heeft bekeken of in die lijsten belangrijke symptomen genoemd staan, die in de NICE stoplichttabel ontbreken. Op basis hiervan zijn geen nieuwe items toegevoegd. Wel heeft de werkgroep een item opgenomen in de stoplichttabel wat in de vorige versie van deze richtlijn was weggelaten: het oranje “koorts > 39 graden bij leeftijd 3-6 maanden”. Dit item is samengevoegd met het rode NICE item “koorts > 38 graden bij leeftijd <3 maanden" tot een oranje item “koorts > 39 graden bij leeftijd 0-6 maanden”. Hiervoor is gekozen omdat de werkgroep van mening is dat niet alle kinderen < 3 maanden per definitie in de rode (hoog-risico) categorie hoeven te vallen. Met de verhoogde kwetsbaarheid van kinderen <3 maanden is uiteraard wel rekening gehouden bij het opstellen van de adviezen voor kinderen in deze leeftijdsgroep in de oranje en groene risico-categorieën (NICE stoplichtentabel, link toevoegen appendix tabel 2).

Los van de (consensus-based) alarmsymptomen moet bij sommige kinderen rekening worden gehouden op een a priori verhoogde kans op een ernstige bacteriële infectie. Denk hierbij aan kinderen met een onderliggende afweerstoornis, prematuur geboren kinderen of aan kinderen die niet gevaccineerd zijn. Tevens moet men in de benadering van een kind met koorts zonder focus altijd alert blijven op symptomen die wel in de richting van een focus kunnen wijzen. In de appendix tabel 3 ‘Samenvatting van symptomen van specifieke aandoeningen’ staan kenmerken voor specifieke aandoeningen. Indien deze kenmerken aanwezig zijn bij kinderen met koorts dient aanvullende diagnostiek voor specifieke aandoeningen te worden overwogen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Het merendeel van de kinderen die zich met koorts presenteren op de SEH heeft een virale infectie die geen antibiotische behandeling behoeft. De grote uitdaging is om die kinderen die wél een ernstige bacteriële infectie (meningitis, sepsis, urineweginfectie, pneumonie) hebben, vroegtijdig te herkennen. Indien met behulp van anamnese en lichamelijk onderzoek kinderen met een verhoogd risico op een bacteriële infectie kunnen worden geïdentificeerd, kan bij een deel van de kinderen met een self-limiting infectie, onnodige diagnostiek en/of behandeling voorkomen worden. In de vorige versie van de richtlijn werd hiervoor het gebruik van de NICE stoplichttabel geadviseerd. Deze tabel, met een overzicht van verschillende klinische kenmerken, wordt inmiddels al jarenlang intensief gebruikt. De vraag is of er op basis van de literatuur redenen zijn om andere klinische kenmerken te gaan gebruiken.

Vervolgens is de vraag of er een voldoende gevalideerd predictiemodel beschikbaar is, gebaseerd op klinische karakteristieken en aanvullende diagnostiek, die kan ondersteunen om de kans op ernstige bacteriële infecties bij kinderen met koorts op een SEH te voorspellen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that longer duration of illness, general appearance, having a chronic disease, crying, feeling hot, having chills, no fluid intake, elevated heart rate, being unvaccinated for meningococcal, very high recorded temperature and fever for more than 2 days are predictors of urinary tract infection in children <5 year presenting to the emergency department with fever.

The evidence suggests that having respiratory symptoms, having diarrhoea, cough, abnormal ear, nose and throat signs, being male, having focal bacterial infection, infectious contacts and rash makes the diagnosis of urinary tract infection in children <5 year presenting to the emergency department with fever less likely.

Sources: Craig, 2010; Williams-Smith, 2020 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that longer duration of illness/fever, general/ill appearance, breathing difficulty, low oxygen saturation, having a chronic disease, cough, chest crackles, abnormal chest sound, elevated heart rate, elevated respiratory rate, being unvaccinated for pneumococcal, very high recorded temperature and CRP are predictors of pneumonia in children aged 1 month to 16 years old presenting to the emergency department with fever.

The evidence suggests that abnormal ear, nose and throat signs, rash and audible wheeze makes the diagnosis of pneumonia in children aged 1 month to 16 years old presenting to the emergency department with fever less likely.

Sources: Craig, 2010; Nijman, 2013; Nijman, 2018 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the predictors of Invasive bacterial infection in children aged ≤6 months old presenting to the emergency department with fever.

Sources: Aronson, 2019 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the predictors of total serious bacterial infection in children aged 1 month to 16 years old presenting to the emergency department with fever.

Sources: Nomura, 2019; Brent, 2011 |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that being female and CRP are predictors of total serious bacterial infection in children <5 year presenting to the emergency department with fever.

Sources: Nijman, 2013; Nijman, 2018 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Diagnostic testing guided by the clinical prediction model by Nijman et al. (2013; based on age, temperature, sex, duration fever, prolonged capillary refill, chest wall retractions, ill appearance, oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, heart rate, and C-reactive protein) results in standardized evaluation with little to no difference in diagnostic accuracy of SBI in children aged under 16 years of age presenting to the emergency department with fever without a clear source compared to clinical routine evaluation.

Sources: de Vos-Kerkhof, 2015 |

|

Low GRADE |

Children younger than 3 months The evidence suggests that the continuous clinical prediction model by Craig (2010) is not useful in predicting UTI in children aged <3 months old presenting to the emergency department with fever.

Children 3-12 months old In absence of evidence for children with UTI specifically, no conclusions can be drawn about models predicting UTI in children aged 3-12 months old presenting to the emergency department with fever.

Children older than 12 months In absence of evidence for children with UTI specifically, no conclusions can be drawn about models predicting UTI in children older than 12 months presenting to the emergency department with fever.

Sources: de Vos-Kerkhof, 2018 |

|

Low GRADE |

Children younger than 3 months The evidence suggests that higher scores on the continuous clinical prediction rules by Nijman (2013) and Craig (2010) somewhat increase the probability of pneumonia in children under 3 months presenting to the emergency department with fever.

Children 3-12 months old The evidence suggests that a higher score on the continuous clinical prediction rule by Nijman (2013) somewhat increases the probability of pneumonia in children aged 3-12 months presenting to the emergency department with fever. This was consistent in external cohorts. Application impacts management for hospitalization and antibiotic use.

Children older than 12 months The evidence suggests that the dichotomous prediction rules by Mahabee-Gittens (2005), van den Bruel (2007), and Neuman (2011) have little value in predicting pneumonia in children under 3 years presenting to the emergency department with fever. This was consistent in external cohorts. Application impacts management for hospitalization and antibiotic use.

The evidence suggests that a higher score on the continuous clinical prediction rule by Oostenbrink (2013) somewhat increases the probability of pneumonia in children under 3 years presenting to the emergency department with fever.

Sources: de Vos-Kerkhof, 2018; van de Maat, 2019 |

|

Low GRADE |

Children younger than 3 months The evidence suggests that a positive outcome on the dichotomous clinical prediction rule by Galetto-Lacour (2010, Lab-score) somewhat increases the probability of IBI in infants presenting to the emergency department with fever. This was consistent in external cohorts. The step-by-step rule (ref Mintegi) has in particular sensitivity to detect IBI, but with low specificity.

Children 3-12 months old Due to a lack of research data, no conclusions can be drawn about models predicting IBI in children aged 3-12 months old presenting to the emergency department with fever.

Children older than 12 months Due to a lack of research data, no conclusions can be drawn about models predicting IBI in children older than 12 months presenting to the emergency department with fever.

Sources: Gomez, 2016 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Children younger than 3 months A positive outcome on the dichotomous clinical prediction rules by Bachur and Harper (2001) increases the probability of total SBI in children under 3 months presenting to the emergency department with fever. A positive outcome on the clinical prediction rule by Van den Bruel (2007) somewhat increases the probability of total SBI in children under 3 months presenting to the emergency department with fever.

A higher score on the continuous clinical prediction model by Bleeker et al. (2007) increases the probability of total SBI in children under 3 months presenting to the emergency department with fever.

Children 3-12 months old A positive outcome on the dichotomous clinical prediction rules by Galetto-Lacour (2010, Lab-score) or Bachur and Harper (2001) increases the probability of total SBI in children 3-12 months old presenting to the emergency department with fever.

Children older than 12 months A negative score on the pneumonia rule or the 5 stage decision tree somewhat lowers the probability of total SBI children aged 0-3 years

Sources: de Vos-Kerkhof, 2018 |

Samenvatting literatuur

1. Prognostic factors

Description of studies

Williams-Smith (2020) performed a prospective cohort study comparing potential predictors of SBI between children with and without SBI aged 0 to 36 months old visiting the emergency department with fever (≥38.0°C) without a source between October 2015 and October 2017. The main outcome was any SBI, including bacteremia, UTI (pyelonephritis), community-acquired pneumonia, bacterial meningitis, osteomyelitis, or septic arthritis

within a 10-day follow-up period. A total of 173 children were included, with a median age of 4.4 months (IQR 2.1-11 months), from which 54% was male. A total of 47 children (27%) had a final diagnosis of SBI, which were all urinary tract infections (UTI’s).

Hagedoorn (2021) performed a prospective observational study to develop and validate a clinical prediction model to identify invasive bacterial infections (IBI’s) in febrile children presenting to different European emergency departments (EDs). Children aged from 0 to 18 years with temperature ≥38.0°C or fever <72 hours before ED visit were included. Twelve EDs in 8 countries participated: Austria, Germany, Greece, Latvia, the Netherlands (n=3), Spain, Slovenia and the UK (n=3). Data were collected for at least 1 year from January 2017 to April 2018. IBI included bacterial meningitis, bacteraemia and bacterial bone/joint infections, defined as culture or PCR detection of a single pathogenic bacterium in blood, cerebrospinal or synovial fluid. A total of 16268 patient were included, from which 135 (0.8%) were diagnosed with an IBI. The median age was 3.2 (IQR 0.8-6.0) and 44% was male for those with an IBI and 2.8 (IQR 1.4-6.0) and 45% was male for those with no IBI. Hagedoorn did not report the 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio in the multivariate logistic model for IBI, whereby the statistical significance of predictors could not be distracted.

Nomura (2019) investigated the predictive value of vital sign parameters for serious bacterial infection (SBI) in young infants (<90 days) visiting the emergency department with axillary temperature ≥38.0°C at triage between November 2011 and November 2013. The recorded vital signs were axillary temperature, heart rate, oxygen saturation and respiratory rate. Respiratory rate was not analyzed, because >20% of the patients had missing values. An SBI was defined as a clinically diagnosed bacterial infection, such as bacterial meningitis, bacteremia, urinary tract infection (UTI), bacterial pneumonia, bacterial soft-tissue infection, suppurative lymphadenitis, osteomyelitis, and bacterial enteritis. Bacterial meningitis, bacteremia, UTI or bacterial enteritis was diagnosed on detection of pathogens from specimens taken from the focus of the infection. Bacterial pneumonia and osteomyelitis diagnosis was based on the clinical manifestations and imaging. Bacterial soft-tissue infection and suppurative lymphadenitis diagnosis was based on the symptoms and physical examination. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the SBI predictors. Gender (male), heart rate (≥180 beats/min), oxygen saturation (≤96%) and body temperature (≥38.5°C) were selected as potential predictors in a multivariate logistic regression analysis. A total of 269 infants were analyzed, from which 59% was male and the mean age was 55.4 (SD 21.7) days. 43 children (16.0%) had an SBI.

Aronson (2019) performed a case-control study of febrile infants ≤60 days old to develop and internally validate a prediction model for invasive bacterial infection (IBI). Children ≤60 days with IBI were identified through query of each hospital’s microbiology laboratory database or electronic medical record system for blood (bacteremia) and/or CSF (bacterial meningitis) cultures with growth of a pathogen. Children with a rectal temperature ≥38°C, documented not ill appearing and without complex condition were included. Each case patients was matched to 2 control children at the same hospital with the closest date of visit to the case patient. The following data was extracted from the medical record: age, sex, gestational age, household sick contacts, symptoms of upper respiratory infection, duration of fever, measured temperature, triage heart rate, respiratory rate, signs of URI and/or bronchiolitis; WBC count, ANC, CRP, procalcitonin, urinalysis results, urine culture and blood culture. IBI was defined by growth of a pathogen in blood (bacteremia) and/or cerebrospinal fluid (bacterial meningitis). A total of 181 children with IBI were included (median age 28 (IQR 16-43) days; 56% male), from which 155 (85.6%) had bacteremia without meningitis and 26 (14.4%) had bacterial meningitis. The case patients were matched to 362 control patients (median age 35.5 (23-47) days; 55% male).

Nijman (2018) performed a prospective observational study in two Dutch emergency departments to validate the Feverkidstool to identify SBI’s in febrile children aged 1 month to 16 years old, and to determine the incremental diagnostic value of procalcitonin (PCT). Children were recruited at the moment of triage and included between February 2009 and May 2012. Fever was defined as a body temperature ≥ 38.5 °C at triage, fever recorded at home within 24 h before consultation, fever as reason for referral by the general practitioner, or fever as positive discriminator in the Manchester Triage System. CRP was measured either by a bedside test (84%) or by a traditional laboratory test (16%). SBI was categorized into children with pneumonia and children with other SBI (UTI, septicemia, meningitis, orbital cellulitis, erysipelas, bacterial gastroenteritis, bacterial arthritis, bacterial upper airway infection, and bacterial osteomyelitis) vs. children with no SBI. A total of 1085 children were included, from which 56% was male and the median age was 1.59 (25th-75th percentile 0.85 to 3.45) years. 73 children (7%) had pneumonia and 98 children (9%) had other SBI’s.

Nijman (2013) performed a prospective observational study in three paediatric emergency departments to derive, cross validate and externally validate a clinical prediction model to assess the risk of different bacterial infections in children with fever at the emergency department. For the derivation and cross validation, all children aged 1 month to 15 years old were prospectively enrolled presenting with fever at the emergency department of the Erasmus MC-Sophia children’s hospital, Rotterdam (2003-05), and the Haga-Juliana children’s hospital, the Hague (2007), the Netherlands. The investigated predictor variables were: age, sex, duration of fever (days), temperature (°C), tachypnoea, tachycardia, oxygen saturation, capillary refill time, chest wall retractions, ill appearance, lnCRO (ln/mg/L) and C statistic. The outcome categories were pneumonia, other serious bacterial infections (SBIs), and no SBIs. Other SBIs included meningitis, septicaemia, UTI, and other (erysipelas, cellulitis, bacterial gastroenteritis, orbital cellulitis, bacterial upper airway infection, ethmoiditis, arthritis, osteomyelitis). A total of 2717 children were included for the development of the prediction model, from which 57% and 55% was male in Erasmus MC-Sophia and Haga-Juliana. The median age was 1.8 (IQR 0.9 to 3.7) years in Erasmus MC-Sophia and 1.5 (IQR 0.7 to 3.2) years. 171 children (6.3%) had pneumonia, 88 children had an UTI (3.2%), 22 children (0.8%) had speticaemia or meningitis, and 60 children had other SBI (2.2%). The external validation was performed in a UK population. Children aged 1 month to 15 years were recruited prospectively at the paediatric assessment unit at the University Hospital Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust, United Kingdom, in 2005 and 2006, if an acute infection was suspected by the parents, the referring clinician, or the triage nurse. Children were eligible if fever was reported by the parents or was documented by the triaging nurse (≥38.5ºC). Children with an increased risk of recurrent serious infections, including those with iatrogenic immunosuppression and haematological malignancies were excluded. A total of 487 children were included in the validation population, from which 44% was maile. The median age was 2.5 (IQR 1.3 to 6.3). 59 children (12%) had pneumonia, 28 children had an UTI (6%), 3 children (1%) had speticaemia or meningitis, and 34 children had other SBI (7 %).

Brent (2011) investigated univariate associations between clinical variables and risk of serious bacterial infection (SBI) in children presenting to the emergency department between September 2000/2001 and March 2001/2002. The investigated clinical variables were: age, sex, risk factor for infection, developmental delay, consciousness level (AVPU score), state variation, temperature, tachycardia, capillary refill time, hydration status, hypotension, tachypnoea, hypoxia, purpuric rash, petechial rash and macular rash. SBI was defined as a positive bacterial culture from blood or another normally sterile site in the appropriate clinical context, radiological signs of pneumonia, clinical meningitis plus a cerebrospinal fluid polymorphonuclear leukocytosis, acute febrile purpura, deep collection(s) requiring intravenous antibiotics±surgical drainage, a white blood cell count ≥20×10 9 /l, a C reactive protein ≥120 mg/l, or a final diagnosis of septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, empyema or mastoiditis. Multivariate logistic regression models

were then derived including variables with at least a weak association with SBI in the univariate analysis, to develop a clinical prediction score for SBI.

A total of 1951 children were included in the final analysis, from which 55% was male and the mean age was 19 months (range 1 month to 15 years). 72 of the children (3.7%) had SBI.

Craig (2010) performed a prospective cohort study to develop and test a multivariable model to distinguish serious bacterial infections from self-limiting non-bacterial illnesses in children <5 years old presenting with a febrile illness to an Australian ED between July 2004 and June 2006. More than 40 clinical signs and symptoms that were routinely elicited in children with fever suspected of having a serious bacterial infection were considered for the diagnostic model. A total of 26 items were included in the final multinomial logistic regression model. The OR’s were calculated from data in the appendix, as only coefficients and SE’s were reported by Craig et al. The primary outcome was serious bacterial infection, defined as UTI, pneumonia or bacteraemia. A total of 14876 febrile illnesses involved one presentation to the ED, 44% was male. The prevalence of children with SBI was 7.2%, from which 3.4% with UTI, 3.4% with pneumonia, 0.4% with bacteraemia.

Results

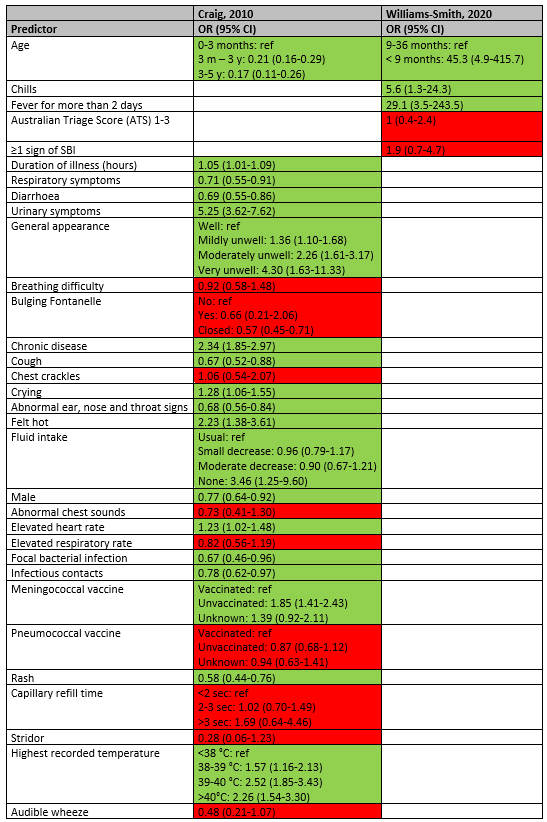

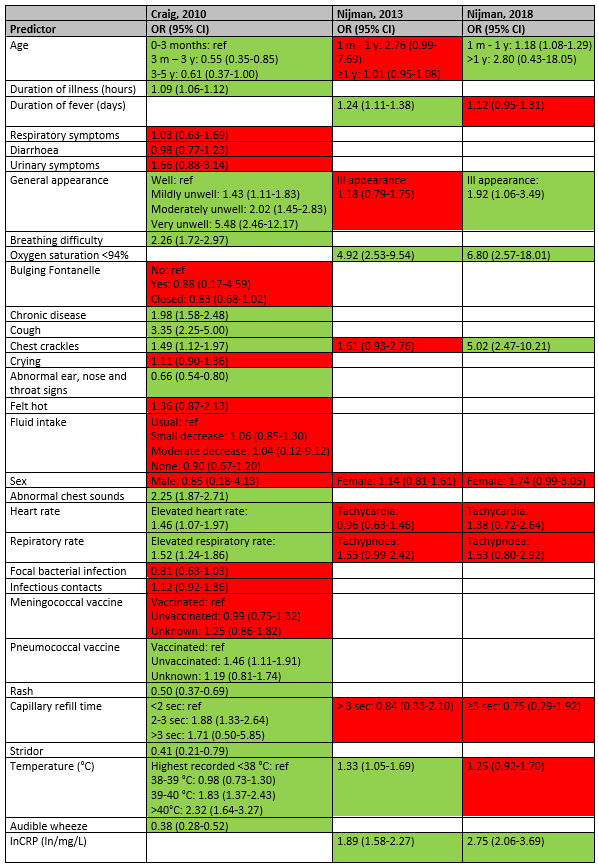

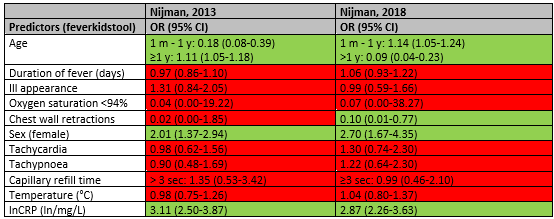

The outcome presence of serious bacterial infection was defined differently in the included studies. Two studies (Craig, 2010; Williams-Smith, 2020) reported prognostic factors for urinary tract infection (UTI), three studies (Craig, 2010; Nijman, 2013; Nijman, 2018) reported prognostic factors for pneumonia and two studies (Nomura, 2019; Brent, 2011) reported prognostic factors for serious bacterial infection (SBI). Two studies (Nijman, 2013; Nijman, 2018) reported prognostic factors for other SBI, which was defined as UTI, septicemia, meningitis, orbital cellulitis, erysipelas, bacterial gastroenteritis, bacterial arthritis, bacterial upper airway infection, and bacterial osteomyelitis. In fact, the Nijman 2018 study can be considered as a prospective validation of the results of the Nijman 2013 study for the clinical factors. The multivariable odds ratios of the prognostic factors are shown in the tables below for the different outcome measures. The predictors with a statistically significant OR are colored green and the predictors being not statistically significant are colored red. The results could not be pooled due to the prognostic design, the use of different multivariate models and differences in populations studied.

1. Urinary Tract Infection (UTI)

The overview of predictors for UTI is listed in table 1.

In the study of Craig (2010), the following statistically significant predictors were identified for the diagnosis of UTI (OR>1): longer duration of illness (OR 1.05; 95% CI 1.01-1.09), urinary symptoms (OR 5.25; 95% CI 3.62-7.62), general appearance (mildly unwell OR 1.36; 95% CI 1.10-1.68; moderately unwell OR 2.26; 95% CI 1.61-3.17; very unwell OR 4.30; 95% CI 1.63-11.33), having a chronic disease (OR 2.34; 95% CI 1.85-2.97), crying (OR 1.28; 95% CI 1.06-1.55), feeling hot (2.23; 95% CI 1.38-3.61), no fluid intake (OR 3.46; 95% CI 1.25-9.60), elevated heart rate (OR 1.23; 95% CI 1.02-1.48), unvaccinated for meningococcal (OR 1.85; 95% CI 1.41-2.43), and high recorded temperature (38-39 °C OR 1.57; 95% CI 1.16-2.13; 39-40 °C OR 2.52; 95% CI 1.85-3.43; >40°C OR 2.26; 95% CI 1.54-3.30).

In the study of Williams-Smith (2020), age < 9 months (OR 45.3; 95% CI 4.9-415.7), having chills (OR 5.6; 95% CI 1.3-24.3) and fever for more than 2 days (OR 29.1; 95% CI 3.5-243.5) were statistically significant predictors of UTI.

In the study of Craig (2010), the following predictors makes the diagnosis of UTI less likely (OR<1): higher age (3 months – 3 year OR 0.21; 95% CI 0.16-0.29; 3 – 5 year OR 0.17; 95% CI 0.11-0.26), having respiratory symptoms (OR 0.71; 95% CI 0.55-0.91), having diarrhoea (OR 0.69; 95% CI 0.55-0.86), cough (OR 0.67; 95% CI 0.52-0.88), abnormal ear, nose and throat signs (OR 0.68; 95% CI 0.56-0.84), being male (OR 0.77; 95% CI 0.64-0.92), focal bacterial infection (OR 0.67; 95% CI 0.46-0.96), infectious contacts (OR 0.78; 95% CI 0.62-0.97), and rash (OR 0.58; 95% CI 0.44-0.76).

Table 1. Overview of prognostic factors for UTI

2. Pneumonia

The overview of predictors for pneumonia is listed in table 2.

Duration of illness and fever were statistically significant predictors of pneumonia in the studies of Craig (OR 1.09; 95% CI 1.06-1.12) and Nijman 2013 (OR 1.24; 95% CI 1.11-1.38), but not in the study of Nijman 2018 (OR 1.12; 95% CI 0.95-1.31). General appearance was a statistically significant predictor for pneumonia in the study of Craig (mildly unwell OR 1.43; 95% CI 1.11-1.83; moderately unwell OR 2.02; 95% CI 1.45-2.83; very unwell OR 5.48; 95% CI 2.46-12.17) and the study of Nijman 2018 (ill appearance OR 1.92; 95% CI 1.06-3.49), but not in the study of Nijman 2013 (ill appearance OR 1.18; 95% CI 0.79-1.75). Breathing difficulty was a predictor in the study of Craig (OR 2.26; 95% CI 1.72-2.97) and oxygen saturation <94% was a statistically significant predictor in Nijman 2013 (OR 4.92; 95% CI 2.53-9.54) and Nijman 2018 (OR 6.80; 95% CI 2.57-18.01). Chest crackles was a statistically significant predictor in the study of Craig (OR 1.49; 95% CI 1.12-1.97) and Nijman 2018 (OR 5.02; 95% CI 2.47-10.21), but not in the study of Nijman 2013 (OR 1.61; 95% CI 0.93-2.76).

In the study of Craig (2010), chronic disease (OR 1.98; 95% CI 1.58-2.48), cough (OR 3.35; 95% CI 2.25-5.00), abnormal chest sounds (OR 2.25; 95% CI 1.87-2.71), being unvaccinated for pneumococcal (OR 1.46; 95% CI 1.33-2.64), 2-3 sec capillary refill time (Or 1.88; 95% CI 1.33-2.64) were statistically significant predictors of pneumonia. The factors abnormal ear, nose and throat signs (OR 0.66; 95% CI 0.54-0.80), rash (OR 0.50; 95% CI 0.37-0.69), stridor (OR 0.41; 95% CI 0.21-0.79) and audible wheeze (OR 0.38; 95% CI 0.28-0.52) makes the diagnosis of pneumonia less likely.

An elevated heart rate (OR 1.46; 95% CI 1.07-1.97) and elevated respiratory rate (OR 1.52; 95% CI 1.24-1.86) were statistically significant predictors of pneumonia in the study of Craig, but not in the studies of Nijman 2013 and Nijman 2018.

Higher body temperature was a statistically significant predictor in the studies of Craig (39-40°C OR 1.83; 95% CI 1.37-2.43; >40°C OR 2.32; 95% CI 1.64-3.27) and Nijman 2013 (OR 1.33; 95% CI 1.05-1.69), but not statistically significant in the study of Nijman 2018.

C-reactive protein was a statistically significant predictor of pneumonia in the studies of Nijman 2013 (OR 1.89;95% CI 1.58-2.27) and Nijman 2018 (OR 2.75; 95% CI 2.06-3.69).

Table 2. Overview of prognostic factors for pneumonia

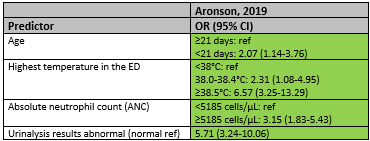

3. Invasive bacterial infections (IBI)

The overview of predictors for IBI is listed in table 3.

Only the results of Aronson (2019) are shown in table 3, because Hagedoorn (2021) did not report the 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio in the multivariate logistic model.

Aronson (2019) reported the statistically significant predictors for IBI only (table 4). These factors were: age < 21 days (OR .07; 95% CI 1.14-3.76), higher temperature in the emergency department (38.0-38.4°C OR 2.31; 95% CI 1.08-4.95; ≥38.5°C OR 6.57; 95% CI 3.25-13.29), higher absolute neutrophil count ≥5185 cells/µL (OR 3.15; 95% CI 1.83-5.43) and abnormal urinalysis results (OR 5.71; 95% CI 3.24-10.06).

Table 3. Overview of prognostic factors for IBI

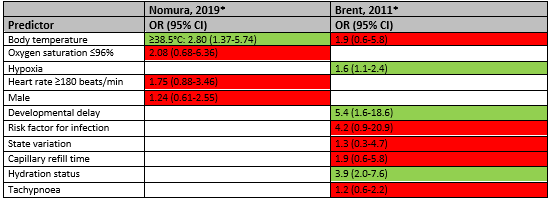

4. Total serious bacterial infections (SBI)

The overview of predictors for total SBI is listed in table 4.

Higher body temperature was a statistically significant predictor of total SBI in the study of Nomura 2019 (≥38.5°C OR 2.80; 95% CI 1.37-5.74) but was not statistically significant in the study of Brent (OR 1.9; 95% CI 0.6-5.8). Hypoxia (OR 1.6; 95% CI 1.1-2.4), developmental delay (OR 5.4; 95% CI 1.6-18.6) and hydration status (OR 3.9; 95% CI 2.0-7.6) were statistically significant predictors of total SBI in the study of Brent (2011). However, the studies of Nomura (2019) and Brent (2011) did not account for the potential confounder age in their multivariate analyses, whereby these results should be interpreted with caution.

Table 4. Overview of prognostic factors for total SBI

*Multivariate analysis not corrected for age

Nijman (2013, 2018) reported total SBI except pneumonia. The overview of predictors for SBI is listed in table 5.

Higher age (≥1 year) was a statistically significant predictor of SBI in the study of Nijman 2013 (OR 1.11; 95% CI 1.05-1.18) but makes the diagnosis less likely in the study of Nijman 2018 (OR 0.04; 95% CI 0.04-0.23). Female sex was a statistically significant predictor of SBI in both studies (Nijman 2013 OR 2.01; 95% CI 1.37-2.94; Nijman 2018 Or 2.70; 95% CI 1.67-4.35). C-reactive protein was also statistically significant predictor of SBI in the studies of Nijman 2013 (OR 3.11;95% CI 2.50-3.87) and Nijman 2018 (OR 2.87; 95% CI 2.26-3.63).

Having chest wall contractions makes the diagnosis of SBI less likely in the study of Nijman 2018 (OR 0.10; 95% CI 0.01-0.77).

Table 5. Overview of prognostic factors for SBI (except pneumonia)

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure UTI was downgraded by two levels because of imprecision (-2, large number of prognostic factors included in the model and limited number of patients) to Low GRADE.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pneumonia was downgraded by two levels because of imprecision (-2, large number of prognostic factors included in the model and limited number of patients) to Low GRADE.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure IBI was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (-2, risk of bias: case-control design whereby case cohort differed from control cohort, prognostic factors were not independent from outcome) and imprecision (limited number of patients) to Very low GRADE.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure total SBI in children aged 1 month to 16 years old was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (-1, risk of bias: no correction for possible confounder age) and imprecision (-2, large number of prognostic factors included in the model and limited number of patients) to Very low GRADE.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure total SBI in children <5 year was downgraded by two levels because of imprecision (-2, large number of prognostic factors included in the model and limited number of patients) to Low GRADE.

Summary of literature

2. Clinical prediction models

Description of studies

De Vos-Kerkhof (2015) performed a randomized controlled trial aiming to assess the clinical impact of the implementation of a clinical decision model (Nijman, 2013, model based on age, temperature, sex, duration fever, prolonged capillary refill, chest wall retractions, ill appearance, oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, heart rate, and C-reactive protein) for febrile children at risk for serious bacterial infections (SBI) attending the emergency department (ED). They included 439 consecutive pediatric patients (≥1 month to <16 years) presenting with fever at the ED, from the first of September 2010 until June 30, 2012. Fever was defined as fever noted at home in the 24 hours prior to presentation, body temperature ≥38.5°C measured at the ED, or use of fever as a positive discriminator of the Manchester Triage System. Well-appearing febrile children with a clear focus of uncomplicated rhinitis or otitis, severely ill children, children with chronic co-morbidities, and children who reattended the ED within one week of their first presentation were excluded. The primary outcome measure was correctly diagnosed SBI.

Results

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Serious bacterial infections (SBI)

In the RCT by de Vos-Kerkhof (2015), the accuracy of the clinical prediction model was similar to the accuracy of clinical judgement. In the intervention group, 42 children underwent chest-radiography, 25 (60%) of which were diagnosed with pneumonia. Similarly, in the control group, 28 children underwent chest radiography, 16 (57%) of which were diagnosed with pneumonia. Thus, for pneumonia, chest radiography based on the clinical prediction model had a sensitivity of 0.89 (95% CI 0.69–0.97) and a specificity of 0.88 (95% CI 0.82–0.91). Chest radiography based on clinicians’ judgement had a sensitivity of 0.86 (95% CI 0.60–0.96) and a specificity of 0.92 (95% CI 0.88–0.95). For SBI other than pneumonia, the clinical prediction model had a sensitivity of 1.0 (95% CI 0.61–1.0) and a specificity of 0.94 (95% CI 0.90–0.97). Clinicians’ judgement had a sensitivity of 0.89 (95% CI 0.57–0.98) and a specificity of 0.96 (95% CI 0.92–0.98). There were no significant differences in rate of hospitalization, length of stay, or revisits, however the study was underpowered to detect such differences. The authors concluded that although the clinical prediction model performed well, its implementation had no substantial impact on patient outcomes.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure SBI was downgraded by one level because of imprecision (low number of events); Moderate GRADE.

Observational studies

The included prediction models and information about the development and validation cohorts of the models are shown in table 1 in the appendix (Table 1. Included models and predictor variables). The validation studies are summarized here. A total of 11 decision models (Mahabee, 2005; van de Bruel, 2007; Neuman, 2011; Lynch, 2004; Oostenbrink, 2013; Craig, 2010; Irwin, 2017; Bachur and Harper, 2001; Thompson, 2009; Bleeker, 2007; Brent, 2011) were cross validated at external datasets, but not at the level of broad prospective validation (Reilly, 2006), and two decision models (Mintegi, 2014 and Galetto-Lacour, 2010) were prospectively broad validated. The decision model of Nijman has been prospectively cross validated, evaluated at the level of narrow impact analysis for ‘other- SBI’ (De Vos-Kerkhof, 2015), and at the level of broad impact analysis for ‘pneumonia’ (Van de Maat, 2020). Most models predicted the diagnosis SBI vs absence of SBI, with SBI incorporating pneumonia, UTI as mainly prevalent diagnosis in the derivation sets, and other SBI as sepsis, meningitis in lower frequency. Craig (2010) developed specific models for UTI, pneumonia, other SBI vs absence of SBI. Nijman predicted pneumonia, other SBI (with 50% being UTI cases in the derivation set).

Van de Maat (2019) aimed to evaluate the performance of eight clinical prediction models for childhood pneumonia (Mahabee, 2005; van de Bruel, 2007; Neuman, 2011; Lynch, 2004; Oostenbrink, 2013; Craig, 2010; Nijman, 2013; and Irwin, 2017). They used two prospectively collected cohorts to evaluate the performance of the prediction models; cohort 1 included children aged between 1 month and 5 years who presented with fever and cough or dyspnea at the emergency department at the Erasmus MC—Sophia, Rotterdam, the Netherlands 2012-2013 (n=248); cohort 2 included children aged between 3 months and 5 years who presented with fever and respiratory symptoms at a pediatric assessment unit at the University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust, United Kingdom 2005-2006 (n=301). The reference standard for definite or probable pneumonia was defined as a bacterial syndrome with matching pathogenic bacteria detected (definite bacterial infection), or bacterial syndrome and CRP>60 mg/l (probable bacterial infection). The prevalence of definite or probable pneumonia was 7% in cohort 1 and 12% in cohort 2.

De Vos-Kerkhof (2018) aimed to evaluate the performance of eight clinical prediction models for serious bacterial infections (dichotomous models: Bachur and Harper, 2001; Van den Bruel, 2007; Galetto-Lacour, 2010; Thompson, 2009. Continuous models: Bleeker, 2007; Brent, 2011; Craig, 2010; Nijman, 2013). They used four prospectively collected cohorts to evaluate the performance of the prediction models. Cohort 1 included all children under 3 months of age who presented with fever at the emergency departments of the Erasmus MC-Sophia Children’s Hospital or the Maasstad Hospital Rotterdam, the Netherlands, 2009-2012 (n=159, prevalence of SBI 15%, with 4/24 pneumonia, 17/24 UTI and 3/24 other SBI), excluding children with chronic comorbidities. Cohort 2 came from the same study, but included included all children >3–12 months of age (n=766, prevalence of SBI 10%, with 16/75 pnemonia, 40/75 UTI and 19/75 other SBI). Cohort 3 included children younger than 3 months presenting with fever without source at the Paediatric Emergency Department of Cruces University Hospital in Bilbao, Spain, between 2003 and 2012 (n=2148, prevalence of SBI 16%, with 4/353 pneumonia, 303/353 UTI and 46/353 other SBI). Cohort 4 included children between 7 and 91 days without major comorbidities who presented with fever at one of 15 pediatric emergency departments in France from October 2008 through March 2011 (n=2204, prevalence of SBI 17%, with 45/381 pneumonia, 319/381 UTI and 17/381 other SBI). The outcome serious bacterial infection included pneumonia, meningitis, septicaemia, urinary tract infections, erysipelas, cellulitis, bacterial gastroenteritis, orbital cellulitis, bacterial upper respiratory infection, ethmoiditis, septic arthritis or osteomyelitis. All diagnoses were confirmed with bacteriological cultures, or nodular infiltrates or consolidations in the lung on chest radiographs.

Aronson (2018) aimed to evaluate the performance of the Rochester criteria and the modified Philadelphia criteria for the risk of invasive bacterial infections (IBI) using data from a case-control study. Data was collected in the emergency departments of nine children’s hospitals between July 2011 and June 2016. Cases (n=135; 118 bacteremia and 17 meningitis cases) were children ≤60 days with IBI who were identified through query of each hospital’s microbiology laboratory database or electronic medical record system for blood (bacteremia) and/or CSF (bacterial meningitis) cultures with growth of a pathogen. Children with a rectal temperature ≥38°C, documented not ill appearing and without complex condition were included. Each case patient was matched to 2 control children (n=249) at the same hospital with the closest date of visit to the case patient. Ten cases and 41 controls were excluded because of missing data. IBI was defined by growth of a pathogen in blood (bacteremia) and/or cerebrospinal fluid (bacterial meningitis). Because of the study design the prevalence of IBI could not be estimated.

Gomez (2016) aimed to evaluate and compare the Step-by-step approach (developed by the authors. Mintegi, 2014), the Rochester criteria (ref), and the Lab-score (Lacour, 2008), three clinical prediction models for the risk of invasive bacterial infections (IBI). They used a prospectively collected multicenter cohort, including infants ≤90 days old who presented with fever without source to one of eight Spanish, two Italian or one Swiss pediatric emergency department between September 2012 and august 2014 (n=2185, prevalence of IBI 3.9% with 36/87 sepsis/meningitis, 25/87 bacteremic UTI, 24/87 occult bacteremia). IBI was defined as isolation of bacterial pathogen (staphylococcus epidermidis, propionibacterium acnes, streptococcus viridans, or diphtheroides) in blood or cerebrospinal fluid culture. In addition, they distinghuished non-invasive bacterial infections (19.1%, of whom 409/417 UTI).

Verbakel (2013) aimed to evaluate four clinical prediction rules (5-stage Decision Tree, Pneumonia Rule, Meningitis Rule, and Yale Observation Scale cutoff >8 and cutoff >10) and two national guidelines (NICE guideline, and NHG alarm symptoms) for SBI. SBI was defined as sepsis (including bacteremia), meningitis, pneumonia, osteomyelitis, cellulitis, or complicated urinary tract infection. They used seven patient cohorts for as validation cohorts. Three of the cohorts (Roukema, 2008; Bleeker, 2007; Monteny, 2008) were relevant for this guideline since they included children with fever without a source. The Roukema (2008) cohort included all children presenting to a Dutch emergency department with fever (>38°), without meningeal irritation, chronic comorbidities, or immunodeficiency (n=1750, mean age 2.9 years, age range 0.1 to 15.7 years). The Bleeker (2007) cohort included children presenting to a Dutch emergency department with fever (>38°) without focus, without chronic comorbidities or immunodeficiency (n=595, mean age 0.9 years, age range 0.0 to 3.0 years). The Monteny (2008) cohort included children presenting to a Dutch general practitioner with fever, if there was no language barrier (n=506, mean age 2.2 years, age range 0.3 to 5.9 years).

Results

De Vos-Kerkhof (2018) reported the outcome UTI, van de Maat (2019) and de Vos-Kerkhof reported the outcome pneumonia, Gomez (2016) and Aronson (2016) reported the outcome IBI, de Vos-Kerkhof (2018) and Verbakel (2013) reported the outcome SBI. De Vos-Kerkhof (2013) also reported the outcomes SBI other than pneumonia and bacteremia separately. It should be noted, however, that for most cohorts, the majority of SBI other than pneumonia include UTI.

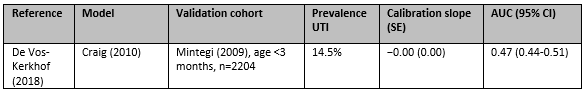

1. Urinary Tract Infection (UTI)

In the study by de Vos-Kerkhof (2018), the clinical prediction model by Craig (2010) had an AUC of 0.47 (95% CI 0.44-0.51) for predicting UTI in a cohort of children under 3 months, meaning that it made a correct prediction in 47% of the children.

Table 7. Continuous models, outcome UTI

UTI, urinary tract infection; SE, standard error; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval

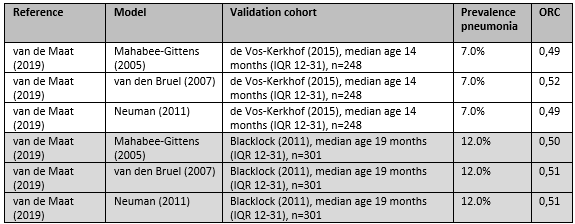

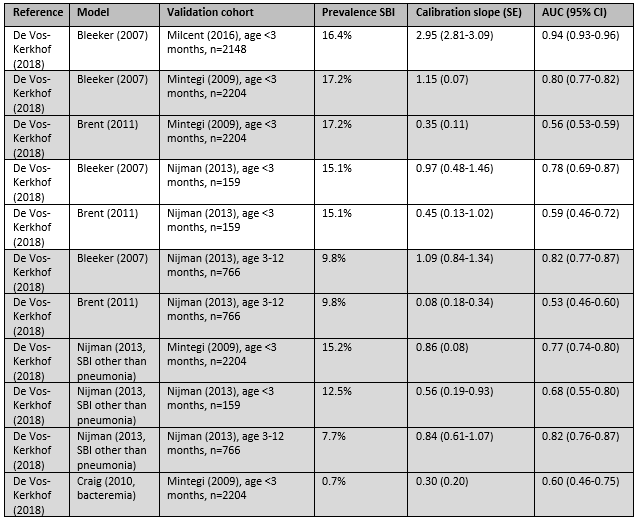

2. Pneumonia

In the study by de Vos-Kerkhof (2018), the clinical prediction model by Craig (2010) was validated in a French cohort of children under 3 months and had an AUC of 0.74 (95% CI 0.67-0.82) for predicting pneumonia, meaning that it made a correct prediction in 74% of the children. The clinical prediction model by Nijman (2012) was validated in three different cohorts of children with AUCs ranging from 0.72 to 0.89.

In the study by van de Maat (2019), the performance of the clinical prediction models was reported graphically, but not in confusion matrices. The performance of the clinical prediction models evaluated by van de Maat (2019) could therefore not be compared with the performance of clinical prediction models evaluated by de Vos-Kerkhof (2018).

Table 8. Dichotomous models, outcome pneumonia (per cohort)

IQR, interquartile range; ORC, ordinal c-statistic or concordance statistic

Table 9. Continuous models, outcome pneumonia (per cohort)

IQR, interquartile range; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval

3. Invasive bacterial infections (IBI)

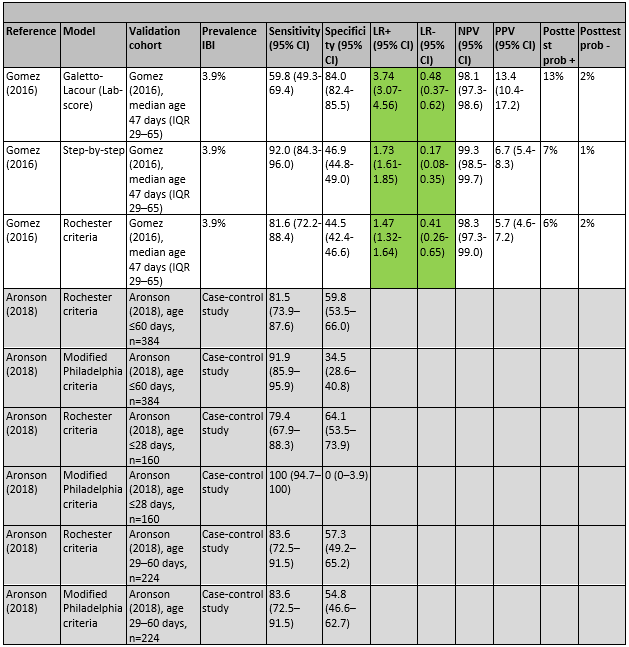

In the study by Gomez (2016), the clinical prediction models the Lab-score, Step-by-step, and the Rochester criteria were evaluated. All three models had significant positive and negative likelihood ratios. The Lab-score had the highest positive likelihood ratio (3.74), and the highest post-test probability following a positive test (13%), meaning that children with a positive Lab-score had probability of 13% for having IBI, as compared with a probability of 4% in the whole population. Step-by-step had the lowest negative likelihood ratio (0.17) and the lowest post-test probability following a negative test (1%), meaning that children with a negative Step-by-step-score had probability of 1% for having IBI, as compared with a probability of 4% in the whole population. Gomez (2016) concluded that their own Step-by-Step was the most sensitive of the three evaluated models (Step-by-step, Lab-score, Rochester criteria). However, the specificity and overall performance of the Lab-score was better.

In the case-control study by Aronson (2016), the sensitivity and specificity of the Rochester criteria and the modified Philadelphia criteria were evaluated. In children younger than 60 days, the Rochester criteria had a sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 45%, the modified Philadelphia criteria had a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 35%. Aronson (2016) concludes that their findings support the use of the modified Philadelphia criteria in febrile children between 29 and 60 days who do not receive routine CSF testing.

Table 10. Dichotomous models, outcome IBI (per cohort)

IBI, invasive bacterial infection; CI, confidence interval; LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR-, negative likelihood ratio; Posttest prob +, post-test probability of IBI with a positive test result; Posttest prob -, post-test probability of IBI with a negative test result

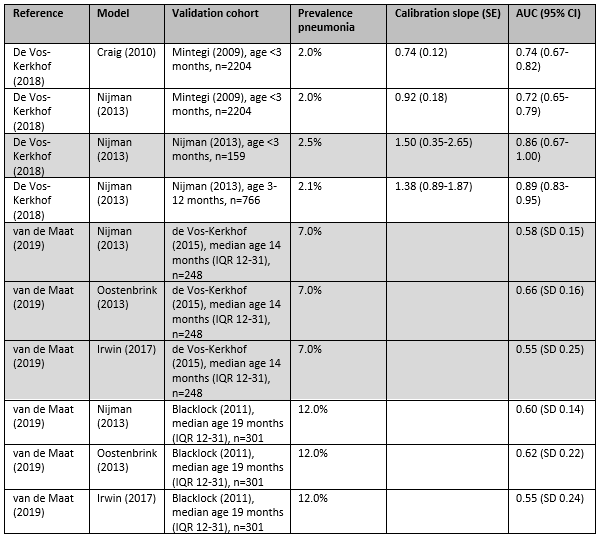

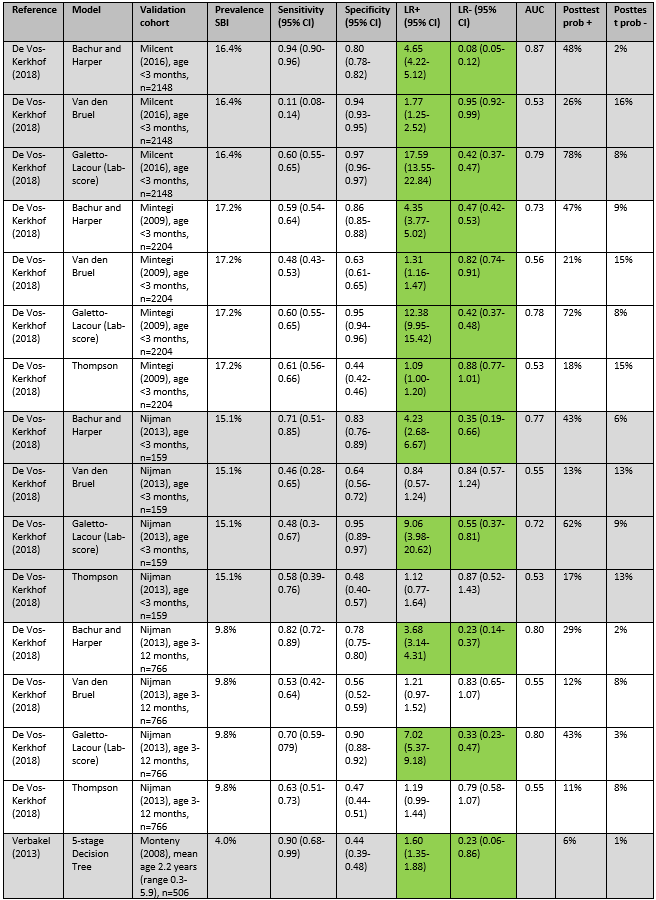

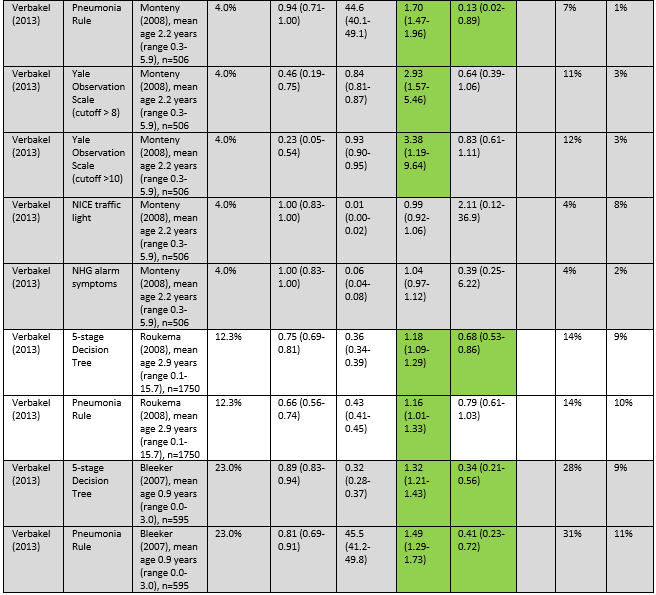

4. Total serious bacterial infections (SBI)

De Vos-Kerkhof (2018) and Verbakel (2013) evaluated the performance of six clinical prediction rules for SBI and two national guidelines. The prediction rules of Bachur and Harper and the Lab-score had significant positive and negative likelihood ratios in all four validation cohorts. Positive likelihood ratios for Bachur and Harper ranged from 3.68 to 4.65, negative likelihood ratios ranged from 0.08 to 0.47. Positive likelihood ratios for Galetto-Lacour ranged from 7.02 to 17.59, and negative likelihood ratios ranged from 0.33 to 0.55.

In the Milcent (2009) cohort, a positive Lab score had the highest post-test probability (78%), and a negative Bachur and Harper score had the lowest post-test probability (2%). In the Mintegi (2009) cohort, a positive Lab score had the highest post-test probability (72%), and a negative Lab-score the lowest post-test probability (8%). In the Nijman (2013) cohort of children under 3 months, a positive Lab score had the highest post-test probability (62%), and a negative Bachur and Harper score had the lowest post-test probability (6%). In the Nijman (2013) cohort of children between 3 and 12 months, a positive Lab score had the highest post-test probability (43%), and a negative Bachur and Harper score had the lowest post-test probability (2%). In the Monteny (2008) cohort, a Yale Observation Scale score >10 had the highest post-test probability (12%), and a negative score on the 5-stage Decision Tree or the Pneumonia rule had the lowest post-test probability (both 1%).

De Vos-Kerkhof (2018) concludes that the best overall performance was achieved with the Bachur and Harper, Galetto-Lacour, Bleeker, and Nijman models, all including different combinations of clinical signs and symptoms, urine dipstick analysis and laboratory markers. Verbakel (2013) concludes that none of the evaluated prediction rules were valuable for high prevalence settings.

Table 11. Dichotomous models, outcome SBI (per cohort)

IBI, invasive bacterial infection; CI, confidence interval; LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR-, negative likelihood ratio; AUC, area under the curve; Posttest prob +, post-test probability of IBI with a positive test result; Posttest prob -, post-test probability of IBI with a negative test result

Of the continuous models evaluated by de Vos-Kerkhof (2018), Bleeker (2007) had the highest AUC, ranging from 0.80 to 0.94.

Table 12. Continuous models, outcome SBI (per cohort)

SBI, serious bacterial infection; SE, standard error; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure UTI was downgraded by two levels because of indirectness (no comparison with other models) to Low GRADE.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pneumonia was downgraded by two levels because of high risk of bias (low number of events) to Low GRADE.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure IBI was downgraded by two levels because of high risk of bias (low number of events) to Low GRADE.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure total SBI was downgraded by one level because of indirectness (no comparison with other models) to Moderate GRADE.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

1. Which prognostic/diagnostic factors are associated with a higher risk on the presence of a serious bacterial infection (meningitis, sepsis, urinary tract infection, pneumonia) in children (0-16 years old) with fever?

P: Children (0-16 years) with fever in secondary care

I: Prognostic/diagnostic factors: anamnesis and symptoms during physical examination

C: Absence of prognostic/diagnostic factors

O: Presence of serious bacterial infection (meningitis, sepsis, urinary tract infection, pneumonia)

2. What is the best prediction model to predict the risk of serious bacterial infections in children (0-16 years old) with a fever in the emergency department?

P: Children (0-16 years) with fever in secondary care

I: Prediction model A

C: Prediction model B

O: Presence of serious bacterial infection (meningitis, sepsis, urinary tract infection, pneumonia)

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered presence of serious bacterial infection as a critical outcome measure for decision making, defined as meningitis, sepsis, urinary tract infection or pneumonia.

The working group defined age as a possible confounder, for which must be corrected in the included studies.

A priori, no minimal clinically (patient) important difference was defined.

For this prognostic clinical question, the aim is to investigate multiple factors that may predict presence of serious bacterial infection in children with fever. To investigate whether factors are predictive, a longitudinal relation between candidate prognostic factors (measured at T0) and outcome (measured at T1) has to be investigated. Often, prognostic factors are correlated with other factors, and as a result, their individual associations with

outcomes may be potentially misleading (Foroutan, 2020). To describe the effect of single prognostic factors, these should be measured in relation to its confounders. Mostly, important confounders can be predefined. Only multivariable analyses, including all predefined confounders and independent prognostic factors, can be taken into account.

Search and select (Methods)

A combined search was performed for the present module and the module about prediction models. The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 1 December 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 923 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, and observational studies after 2010 about how children (0-16 year) with a serious bacterial infection (defined as meningitis, sepsis, urinary tract infection or pneumonia), presenting with fever on the SEH, could be recognised, using a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. For this module, 51 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 43 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 8 studies were included.

Results

1. Prognostic factors

Eight studies were included in the analysis of the literature for the first clinical question. Two studies (Nomura, 2019; Brent, 2011) reported multivariate analyses of factors predicting serious bacterial infection (SBI). These studies did not adjust for the possible confounder age in the multivariate analysis. The outcome SBI was reported differently in the included studies, six studies reported for example pneumonia, UTI, IBI or ‘other SBI’. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

2. Clinical prediction models

Six studies were included in the analysis of the literature for the second clinical question. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables. Five further studies, comparing the accuracy of several clinical prediction models, are also described but not graded.

Referenties

- Aronson, P. L., Wang, M. E., Shapiro, E. D., Shah, S. S., DePorre, A. G., McCulloh, R. J., ... & Neuman, M. I. (2018). Risk stratification of febrile infants≤ 60 days old without routine lumbar puncture. Pediatrics, 142(6).

- Brent, A. J., Lakhanpaul, M., Thompson, M., Collier, J., Ray, S., Ninis, N., ... & MacFaul, R. (2011). Risk score to stratify children with suspected serious bacterial infection: observational cohort study. Archives of disease in childhood, 96(4), 361-367.

- Craig, J. C., Williams, G. J., Jones, M., Codarini, M., Macaskill, P., Hayen, A., Irwig, L., Fitzgerald, D. A., Isaacs, D., & McCaskill, M. (2010). The accuracy of clinical symptoms and signs for the diagnosis of serious bacterial infection in young febrile children: prospective cohort study of 15 781 febrile illnesses. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 340, c1594.

- Davis, J., & Lehman, E. (2019). Fever characteristics and risk of serious bacterial infection in febrile infants. The Journal of emergency medicine, 57(3), 306-313.

- de Vos-Kerkhof, E., Nijman, R. G., Vergouwe, Y., Polinder, S., Steyerberg, E. W., van der Lei, J., Moll, H., & Oostenbrink, R. (2015). Ernstige infecties bij kinderen met koorts op de SEH: bruikbaarheid en implementatie van een klinisch beslismodel [Impact of a clinical decision model for febrile children at risk for serious bacterial infections at the emergency department: a randomized controlled trial]. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde, 159, A9552.

- de Vos-Kerkhof, E., Gomez, B., Milcent, K., Steyerberg, E. W., Nijman, R. G., Smit, F. J., ... & Oostenbrink, R. (2018). Clinical prediction models for young febrile infants at the emergency department: an international validation study. Archives of disease in childhood, 103(11), 1033-1041.

- Foroutan, F., Guyatt, G., Zuk, V., Vandvik, P.O., Alba, A.C., e.a. (2020). GRADE Guidelines 28: Use of GRADE for the assessment of evidence about prognostic factors: rating certainty in identification of groups of patients with different absolute risks. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 121, 62-70.

- Fuijkschot, J., Vernhout, B., Lemson, J., Draaisma, J. M., & Loeffen, J. L. (2015). Validation of a Paediatric Early Warning Score: first results and implications of usage. European journal of pediatrics, 174(1), 15-21.

- Galetto-Lacour, A., Zamora, S. A., Andreola, B., Bressan, S., Lacroix, L., Da Dalt, L., & Gervaix, A. (2010). Validation of a laboratory risk index score for the identification of severe bacterial infection in children with fever without source. Archives of disease in childhood, 95(12), 968-973.

- Gomez, B., Mintegi, S., Bressan, S., Da Dalt, L., Gervaix, A., & Lacroix, L. (2016). Validation of the "step-by-step" approach in the management of young febrile infants. Pediatrics, 138(2).

- Hagedoorn, N. N., Borensztajn, D., Nijman, R. G., Nieboer, D., Herberg, J. A., Balode, A., von Both, U., Carrol, E., Eleftheriou, I., Emonts, M., van der Flier, M., de Groot, R., Kohlmaier, B., Lim, E., Maconochie, I., Martinón-Torres, F., Pokorn, M., Strle, F., Tsolia, M., Zavadska, D., Moll, H. A. (2021). Development and validation of a prediction model for invasive bacterial infections in febrile children at European Emergency Departments: MOFICHE, a prospective observational study. Archives of disease in childhood, 106(7), 641-647.

- Kerkhof, E., Lakhanpaul, M., Ray, S., Verbakel, J. Y., Van den Bruel, A., Thompson, M., ... & European Research Network on recognising serious InfEctions (ERNIE) members. (2014). The predictive value of the NICE red traffic lights in acutely ill children. PLoS One, 9(3), e90847.

- Kuppermann, N., Dayan, P. S., Levine, D. A., Vitale, M., Tzimenatos, L., Tunik, M. G., Saunders, M., Ruddy, R. M., Roosevelt, G., Rogers, A. J., Powell, E. C., Nigrovic, L. E., Muenzer, J., Linakis, J. G., Grisanti, K., Jaffe, D. M., Hoyle, J. D., Jr, Greenberg, R., Gattu, R., Cruz, A. T., Febrile Infant Working Group of the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) (2019). A Clinical Prediction Rule to Identify Febrile Infants 60 Days and Younger at Low Risk for Serious Bacterial Infections. JAMA pediatrics, 173(4), 342-351.

- Mintegi, S., Bressan, S., Gomez, B., Da Dalt, L., Blázquez, D., Olaciregui, I., de la Torre, M., Palacios, M., Berlese, P., & Benito, J. (2014). Accuracy of a sequential approach to identify young febrile infants at low risk for invasive bacterial infection. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ, 31(e1), e19-e24.

- Nomura, O., Ihara, T., Sakakibara, H., Hirokoshi, Y., & Inoue, N. (2019). Predicting serious bacterial infection in febrile young infants utilizing body temperature. Pediatrics International, 61(5), 449-452.

- Nijman, R. G., Vergouwe, Y., Thompson, M., van Veen, M., van Meurs, A. H., van der Lei, J., Steyerberg, E. W., Moll, H. A., & Oostenbrink, R. (2013). Clinical prediction model to aid emergency doctors managing febrile children at risk of serious bacterial infections: diagnostic study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 346, f1706.

- Nijman, R. G., Vergouwe, Y., Moll, H. A., Smit, F. J., Weerkamp, F., Steyerberg, E. W., van der Lei, J., de Rijke, Y. B., & Oostenbrink, R. (2018). Validation of the Feverkidstool and procalcitonin for detecting serious bacterial infections in febrile children. Pediatric research, 83(2), 466-476.

- Reilly, B. M., & Evans, A. T. (2006). Translating clinical research into clinical practice: impact of using prediction rules to make decisions. Annals of internal medicine, 144(3), 201-209.

- Van De Maat, J., Nieboer, D., Thompson, M., Lakhanpaul, M., Moll, H., & Oostenbrink, R. (2019). Can clinical prediction models assess antibiotic need in childhood pneumonia? A validation study in paediatric emergency care. PloS one, 14(6), e0217570.

- Van de Maat, J. S., Peeters, D., Nieboer, D., van Wermeskerken, A. M., Smit, F. J., Noordzij, J. G., ... & Oostenbrink, R. (2020). Evaluation of a clinical decision rule to guide antibiotic prescription in children with suspected lower respiratory tract infection in the Netherlands: a stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial. PLoS medicine, 17(1), e1003034.

- Verbakel, J. Y., Van den Bruel, A., Thompson, M., Stevens, R., Aertgeerts, B., Oostenbrink, R., ... & Buntinx, F. (2013). How well do clinical prediction rules perform in identifying serious infections in acutely ill children across an international network of ambulatory care datasets?. BMC medicine, 11(1), 1-11.

- Williams-Smith, J. A., Fougère, Y., Pauchard, J. Y., Asner, S., Gehri, M., & Crisinel, P. A. (2020). Risk factors for urinary tract infections in children aged 0-36months presenting with fever without source and evaluated for risk of serious bacterial infections. Archives e pediatrie : organe officiel de la Societe francaise de pediatrie, 27(7), 372-379.

Evidence tabellen

Pre-defined core set of confounders:

1. Age

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Prognostic factor(s) |

Follow-up

|

Estimates of prognostic effect |

Comments |

|

Williams-Smith, 2020 |

Type of study: prospective cohort study

Setting and country: ED of tertiary care hospital in Switzerland

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial, no conflicts of interest |

Inclusion criteria: 0–36 months old with fever without source (≥38°C), who were evaluated in emergency department between October 2015 and October 2017; fever duration less than 10 days.

Exclusion criteria: diagnosis of SBI had already been made, ongoing antibiotic treatment, difficulties communicating due to language problems

N=173

Median age (IQR): 4.4 (2.1-11) months

Sex: 54% M / 46% F

Potential confounders or effect modifiers:

|

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: 10 days after being enrolled in the study

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? 0

|

Predictors of UTI (multivariate analysis)

OR 45.3; 95% CI 4.9-415.7); P 0.001

OR 5.6; 95% CI 1.3-24.3); P 0.02

OR 29.1; 95% CI 3.5-243.5); P 0.002

OR 1; 95% CI 0.4-2.4); P 0.9

OR 1.9; 95% CI 0.7-4.7); P 0.2 |

|

|

Hagedoorn, 2020 |

Type of study: prospective observational study

Setting and country: 12 ED’s in 8 European countries (Austria, Germany, Greece, Latvia, the Netherlands, Spain, Slovenia, UK)

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial, no conflicts of interest |

Inclusion criteria: Children aged from 0 to 18 years with temperature ≥38.0°C or fever <72 hours before ED visit; patients with CRP measurement

Exclusion criteria: patients with working diagnosis of urinary tract infections after first assessment at the ED

N=16133

Median age (IQR) IBI: 3.2 (0.8-6.0) Non-IBI: 2.8 (1.4-6.0)

Sex: IBI: 44% M / 56% F Non-IBI: 45% M / 55% F

Potential confounders or effect modifiers:

|

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? 0

|

Predictors of IBI*

|

*95% CI of multivariate model not reported |

|

Nomura, 2019 |

Type of study: retrospective observational study

Setting and country: ED of 1 tertiary care hospital in Japan

Funding and conflicts of interest: no conflict of interest, funding not reported |

Inclusion criteria: age <90 days, visiting the ED with axillary temperature ≥38.0°C at triage

Exclusion criteria: none

N=269

Mean age ± SD: 55.4 ± 21.7 days

Sex: 59% M / 41% F

Potential confounders or effect modifiers:

|

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): 6 (2.2%)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Yes, insufficient data. |

OR 2.80; 95% CI 1.37-5.74; P 0.005

OR 2.08; 95% CI 0.68-6.36; P 0.199

OR 1.75; 95% CI 0.88-3.46; P 0.110

OR 1.24; 95% CI 0.61-2.55; P 0.554

|

No adjustments for potential confounder age. No statistically significant difference in age and sex between groups with and without SBI. |

|

Aronson, 2019 |

Type of study: case-control study

Setting and country: ED’s of 11 children’s hospitals in USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial, no conflict of interest |

Inclusion criteria: age≤60 days, presenting to a participating hospital’s ED either from home or from an outpatient clinic; febrile (rectal temperature ≥38.0°C at home, in an outpatient clinic, or in the ED; (2) not ill appearing, as documented on the ED physical examination; without a complex chronic condition.

Exclusion criteria: Ill-appearing infants and those with complex chronic conditions

N=181 with IBI, N=362 control

Median age (IQR): IBI patients: 28 (16-43) days Non-IBI: 35.5 (23-47) days

Sex: IBI patients: 56% M/ 44% F Non-IBI: 55% M / 45% F

Potential confounders or effect modifiers:

|

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): not reported

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

OR 2.07; 95% CI 1.14-3.76

38.0-38.4°C: OR 2.31; 95% CI 1.08-4.95 ≥38.5°C: 6.57; 95% CI 3.25-13.29

OR 5.71; 95% CI 3.24-10.06

OR 3.15; 95% CI 1.83-5.43 |

|

|

Nijman, 2018 |

Type of study: prospective observational study

Setting and country: 2 emergency departments, the Netherlands

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial, no conflicts of interest |

Inclusion criteria: children aged 1 month to 16 years old with fever (body temperature ≥38.5 °C at triage, fever recorded at home within 24 h before consultation, fever as reason for referral by the general practitioner, or fever as positive discriminator in the Manchester Triage System).

Exclusion criteria: Children with an underlying chronic condition requiring specialist pediatric follow-up that is expected to last for at least 1 year; Well-appearing febrile children with a clear focus of an upper airway infection not undergoing additional investigations

N=1085

Median age (IQR): 1.6 (0.8-3.4) years

Sex: Pneumonia: 47% M / 53% F Other SBI: 48% M / 62% F

Potential confounders or effect modifiers: Pneumonie: 73 (7%) Other SBI: 98 (9%)

|

|

Duration or endpoint of follow-up: 72h

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%): 0

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

Predictors of pneumonia

OR 1.18; 95% CI 1.08-1.29

OR 2.80; 95% CI 0.43-18.05

OR 1.74; 95% CI 0.99-3.05

OR 1.12; 95% CI 0.95-1.31

OR 1.25; 95% CI 0.92-1.70

OR 1.53; 95% CI 0.80-2.92

OR 1.38; 95% CI 0.72-2.64

OR 6.80; 95% CI 2.57-18.01

OR 0.75; 95% CI 0.29-1.92

OR 5.02; 95% CI 2.47-10.21

OR 1.92; 95% CI 1.06-3.49

OR 2.75; 95% CI 2.06-3.69

Predictors of other SBI

OR 1.14; 95% CI 1.05-1.24

OR 0.09; 95% CI 0.04-0.23

OR 2.70; 95% CI 1.67-4.35

OR 1.06; 95% CI 0.93-1.22

OR 1.04; 95% CI 0.80-1.37

OR 1.22; 95% CI 0.64-2.30

OR 1.30; 95% CI 0.74-2.30

OR 0.07; 95% CI 0.00-38.27

OR 0.99; 95% CI 0.46-2.10

OR 0.10; 95% CI 0.01-0.77

OR 0.99; 95% CI 0.59-1.66

OR 2.87; 95% CI 2.26-3.63

|

|

|

Nijman, 2013 |

Type of study: Prospective observational diagnostic study

Setting and country: Three paediatric emergency care units, The Netherlands (N=2), UK (N=1)

Funding and conflicts of interest: no funding, no conflicts of interest |

Inclusion criteria: children aged 1 month to 15 years old, presenting with fever at the emergency department of the Erasmus MC-Sophia children’s hospital, Rotterdam (2003-05; if fever had been noted at home in the 24 hours before presentation or body temperature measured in the ED was ≥38.0°C), and the Haga-Juliana children’s hospital, the Hague (2007; if their temperature when measured rectally in the ED was ≥38.0°C.),