Zorg op afstand

Uitgangsvraag

In hoeverre kan zorg op afstand bij diabetes (type 1 en 2) worden ingezet in de tweede lijn?

Aanbeveling

- Overweeg zorg op afstand middels telemonitoring, e-consult, telefonisch consult en videobellen in te zetten als aanvulling op de reguliere, niet-digitale diabeteszorg. Houd de diabeteszorg altijd toegankelijk via niet-digitale toegang.

- Bied mogelijkheden voor telemonitoring gericht op glykemische controle breed aan.

- Lever diabeteszorg op afstand op maat en passend bij de patiënt. Maak gezamenlijk met de patiënt een individuele afweging, waarbijzowel patiëntfactoren en -wensen als specifieke medische factoren (bijv. diabetische voet) een rol spelen

Situaties en onderdelen uit de follow-up van mensen met diabetes (type 1 en 2) die wel of niet op afstand kunnen:

|

Kan digitaal of op afstand |

Fysiek consult |

|

|

Zie in de tweedelijnszorg elke patiënt met diabetes minstens eenmaal per jaar fysiek.

Houd voor de frequentie van controles de aanbevelingen volgens het programma uitkomstgerichte zorg aan (Programma Uitkomstgerichte Zorg, 2023).

Voor kinderen en adolescenten met diabetes type 1 gelden dezelfde bovenstaande aanbevelingen (Zie bijlage ‘De inzet van zorg op afstand bij kinderen en adolescenten met diabetes type 1’)

In het bijgevoegde samenvattingsschema kunt u het overzicht van het zorgproces vinden.

Overwegingen

In dit evidence-to-decision framework worden alle aspecten van kwaliteit (effectiviteit, veiligheid, efficiëntie, kosten, toegankelijkheid, en patiënt- en zorgverlenertevredenheid) toegelicht. Op basis hiervan heeft de werkgroep beoogd aanbevelingen op te stellen over zorg op afstand: of, en zo ja in welke situaties, deze in de keten van diabeteszorg kan worden toegepast. Dit is weergegeven in het bijgevoegde samenvattingsschema van diabeteszorg.

De onderzochte interventie betroffen vooral (combinaties van) de volgende vier vormen van digitale diabeteszorg:

- Telemonitoring (bijv. monitoring van glucose, bloeddruk en of gewicht, beweging op afstand)

- Specifieke interventies of counseling via een digitaal medium/platform al dan niet met specifieke apps en al dan niet met real-time contact mogelijkheden

- Contact op afstand in de vorm van een e-consult

- Contact op afstand in de vorm van een telefonisch consult

- Contact op afstand in de vorm van een videoconsult

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie

Effectiviteit en veiligheid

Definitief stellen dat fysieke zorg vervangen kan worden door zorg op afstand kunnen we niet, omdat er in de literatuur geen onderzoek is gedaan naar de lange termijnseffectiviteit van zorg op afstand. Het vervangen en langetermijnsaspect zijn hierin essentieel: tijdelijk op afstand werken, onderwijs krijgen/geven of zorg ontvangen vormden geen problemen, maar de lange termijnseffecten waren niet altijd positief.

Effectiviteit en veiligheid zijn wel in de literatuuranalyse onderzocht in studies die de reguliere zorg probeerden te verbeteren met (intensievere of meer gestructureerde) behandeling met behulp van zorg op afstand. Er lijkt uit deze studies geen klinisch relevant beter, noch slechter effect van zorg op afstand te zijn ten opzichte van fysieke reguliere zorg. De bewijskracht hiervoor is laag voor patiënten met diabetes type 1, omdat de beoordeelde studies voornamelijk gebaseerd zijn op patiënten met diabetes type 2 (voor hen is de bewijskracht moderate).

Hoewel sommige studies een sterk positief effect op de HbA1c waarden suggereren van zorg op afstand ten opzichte van fysieke zorg bij diabetespatiënten, is dit lastig toe te schrijven aan specifieke factoren of componenten. Men kan de hypothese stellen dat het positieve effect zou kunnen samenhangen met het intensiever bezig te zijn met de eigen zorg en de frequentere en laagdrempelige contactmomenten met de zorgverlener.

- De systematische review van Michaud (2021) beschrijft dat het zelfmanagement bij patiënten met diabetes type 2 verbeterd kan worden omdat ook leefstijl- en gedragsverandering efficiënter kan worden aangepakt met zorg op afstand, in aanvulling op reguliere interactie met zorgprofessionals en het aanpassen van de diabetesmedicatie; real-time feedback (via synchroon contact: telefonisch of videobellen) bleek een sterker positief effect op HbA1c waarden dan feedback die op een later willekeurig moment werd gegeven (asynchroon via e-mail, SMS, webportaal, automatisch gegenereerd bericht).

- Kebede’s (2018) systematische review doet subanalyses voor verschillende typen zorg op afstand voor patiënten met diabetes type 2: voor het gebruik van SMS, communicatie met de zorgverlener via telefoon of video, en internet-gebaseerde interventies (via persoonlijke digitale assistent, computer, tablet of smartphone). Alleen de internet-gebaseerde interventies effectueerden een significante HbA1c daling. Studies met een langere interventieperiode toonden een groter effect op HbA1c; dit kan te maken hebben met gedragsveranderingscomponenten waarop de interventie zich richt, waarbij gedragsverandering tijd nodig heeft. Ook lieten patiënten met een HbA1c waarde >7.5% een grotere daling zien ten opzichte van patiënten met waarde >7.0%. Daarnaast waren er ook psychologische technieken ter ondersteuning van gedragsverandering (promoten van zelfmonitoring en oplossen van problemen), welke gepaard gingen met een sterkere verlaging van het HbA1c.

- Twee RCT’s met een laag risico op bias identificeerden aanvullende factoren voor het succes van zorg op afstand. Molavynejad (2020) hypothetiseert dat patiënten met diabetes type 2 die video tele-educatie ontvingen meer kennis van de therapiedoelen hebben, en een hogere motivatie hebben om te leren over diabetes zelfmanagement en om deel te nemen in shared decision making en andere educatieprogramma’s. Hu (2021) beschrijft ook het beter begrijpen van (de oorzaak van) hypoglykemieën (kennis van therapiedoelen) en het zelfstandig kunnen handelen (zelfmanagement) als positieve componenten van zorg op afstand. Daarnaast worden het frequenter controleren van de bloedglucosewaarden en tijdig advies geven ter voorkoming van hypoglykemie bij telemonitoring aangewezen als componenten die het verschil kunnen maken met de controlegroep.

Vanwege de zeer lage bewijskracht van de literatuur voor Diabetische voetzorg, kan niet met zekerheid iets worden gezegd over hetamputatiepercentage, genezingspercentage en mortaliteit wanneer deze op afstand geleverd wordt, in vergelijking met fysieke zorg. De zeer lage bewijskracht betekent dat de conclusie gemakkelijk kan veranderen bij de publicatie van nieuwe literatuur. De mortaliteit ligt mogelijk hoger, en dit is relevant voor de praktijk en ook zeer plausibel: vaak is dit gerelateerd aan infectie en/of sepsis, waarbij de patiënten gezien moeten worden om de wonden te verzorgen en de mate van infectie en genezingstendens te beoordelen. Deze beoordeling gaat veel lastiger via zorg op afstand.

Met betrekking tot de veiligheid lijkt zorg op afstand te leiden tot minder hypoglykemische events, waarbij de incidence rate ratio tussen de 0.39 en 0.72 gemiddeld ligt (zeer lage bewijskracht). De verklaring die in de RCT voor dit verschil wordt gegeven, is dat frequente monitoring met vroege aanpassingen van de insuline dosering en patiënteducatie ter voorkoming van hypoglykemieën kon plaatsvinden. Het frequentere en laagdrempeligere contact op de cruciale momenten (waarbij proactief kan worden gehandeld) kan dus een succesfactor zijn ten opzichte van een vaste afspraak elke 3 maanden (waarbij achteraf informatie beschikbaar komt).

Efficiëntie

Over efficiëntie is in de literatuur weinig tot geen informatie naar voren gekomen. Efficiëntie hangt echter samen met de invulling van “remote health care delivery”/ zorg op afstand: is dit een app met bijvoorbeeld real time informatie, waardoor er frequenter en tijdiger zorg wordt geleverd? De factoren die maken dat (het proces van) zorg op afstand een succes is moeten worden geïdentificeerd. Pas dan kan er worden beoordeeld welke tijdsinvestering voor deze factoren nodig zijn, en in hoeverre de bestaande zorg hierop kan inspelen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Uit de literatuuranalyse voor de beoordeling van de effectiviteit en veiligheid van zorg op afstand kwamen ook twee RCT’s naar voren die kosten rapporteerden.

Li (2021) gebruikte een diabetes datamanagement systeem en een app om een HbA1c waarde van <7.0% te bereiken. Hierbij werden de totale kosten, incrementele kosten, en incrementele kosten-effectiviteitsratio (ICER) berekend. Registratie, materialen, behandeling, laboratoriumkosten, en kosten voor ziekenhuisopname werden meegenomen. Yang (2022) analyseerde de totale kosten van zorg op afstand-interventies voor één maand, inclusief geneesmiddel- en teststripgebruik, en advieskosten voor diëtisten en fysiotherapeuten. De monetaire eenheid in beide studies was Chinese Yen (¥). De resultaten staan weergegeven in tabel 5. Zorg op afstand lijkt tot een kleine afname van kosten te leiden, maar hoe deze kosten zich verhouden tot effectiviteit (bijvoorbeeld kwaliteit van leven) is niet onderzocht. Daarbij is het niet zeker of deze kostenalyse ook geldt voor Westerse landen, gezien de verschillen in inrichting in het zorgsysteem ten opziche van China.

Tabel 5. Kosten uitkomsten voor zorg op afstand vergeleken met fysieke zorg.

|

|

Yang (2022) (kosten per maand per patiënt) |

Li (2021) (kosten per jaar per patiënt) |

||

|

Telemedicine (n = 50) |

Control (n = 50) |

mHealth (n = 130) |

Usual care (n = 85) |

|

|

Totale kosten (gem., SD) |

193.48 (21.71) |

331.67 (56.37) |

1169.76 (NR) |

1775.44 (NR) |

|

Incrementele kosten (95% CI) |

-138.19 (-154.93 tot -121.45) |

-605.86 (NR) |

||

|

ICER |

|

-22.02 |

||

Gem.: gemiddelde, NR: niet gerapporteerd.

Ook andere niet-Europese auteurs rapporteren (voorzichtig) positief over de kosten verbonden aan zorg op afstand. Eberle (2021) rapporteert een reductie in directe kosten van 24% en in indirecte kosten van 22% voor de groep die maandelijks feedback ontving op data gedownload uit insulinepompen en glucosemeters, in vergelijking met de controlegroep. Per fysiek consult dat kan worden overgeslagen, kan US$142 worden bespaard (Eberle, 2021). Daarnaast rapporteert Hall (2020) een afname van US$60-70 in reiskosten voor patiënten, en minder tijd die patiënten vrij moesten nemen van werk. Hierbij zijn echter ook niet direct de bevindingen te extrapoleren naar de Nederlandse situatie, gezien het verschil in gezondheidszorgsysteem.

Uiteraard zijn er wel kosten verbonden aan het opzetten en inrichten van zorg op afstand. Hoe deze inrichting er precies uit moet zien – zoals ook genoemd onder het kopje Efficiëntie – hangt samen met welke factoren van zorg op afstand effectief zijn. Patiënten moeten beschikken over een mobiele telefoon, computer of tablet (die compatibel is met de geboden software), en een stabiele internetverbinding. Ook in het ziekenhuis moeten de juiste middelen voor communicatie en monitoring aanwezig zijn. Momenteel bestaat er nog onduidelijkheid wie verantwoordelijk is voor deze investering: is dit de afdeling zelf, het ziekenhuis, of is dit een landelijke aangelegenheid? Recent is de handreiking telemonitoring gepubliceerd (FMS, 2022), waarin staat op welke manier en onder welke voorwaarden medisch specialisten zorg op afstand mogen registreren en declareren. Ook moeten de langetermijnscomplicaties die kunnen optreden bij zorg op afstand en de kosten van (het oplossen van) die complicaties in kaart worden gebracht om een betere kosten-batenanalyse van zorg op afstand te kunnen maken.

Verder geeft zorg op afstand milieubelasting. De batterijen en datacentra die hiervoor nodig zijn kosten veel energie en (uitputbare) grondstoffen. Echter, zorg op afstand kan ook zorgen voor een reductie van reisbewegingen (en daarmee CO2-uitstoot).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten en zorgverleners

Uit de literatuur

In de artikelen gebruikt voor de literatuuranalyse voor de effectiviteit en veiligheid van zorg op afstand werden ook zorgverlener- en patiënttevredenheid en verschillende onderdelen van motivatie en gedragsverandering onderzocht.

Drie studies onderzochten tevredenheid op verschillende manieren.

- Maria Gomez (2022) rapporteerde patiënttevredenheid via de insulin treatment satisfaction questionnaire (ITSQ), met een score van 0 (laagste tevredenheid) tot 100 (hoogste tevredenheid). Tevredenheid na 3 maanden behandeling was hoger in de mHealth groep (gemiddeld 73.8, SD 11.1) dan in de standaard zorg groep (gemiddeld 42.8, SD 16.7).

- Turnin (2022) gebruikte een ad-hoc vragenlijst, voor de tevredenheid met het onderzochte telemonitoring apparaat dat sensoren voor biomedische data (glucosemeter, impedantiemeter en actometer) en onderwijssoftware voor voeding en beweging bevatte, en telemonitoring data rapporten genereerde. Vanuit de patiëntenpopulatie antwoordde 97.4% van de respondenten geheel of behoorlijk tevreden te zijn met het gebruik van het telemonitoring apparaat. Slechts de helft van de deelnemende zorgverleners (55%) vulde de tevredenheidsvragenlijst in; van wie 80% aangaf het gebruik van het telemonitoring apparaat gemakkelijk te vinden met betrekking tot het verkrijgen van de telemonitoringsuitslagen. Ook gaf 82.3% aan het gebruik van het apparaat graag te willen continueren.

- Molavynejad (2020) inventariseerde tevredenheid met het gegeven educatieprogramma (via DVD’s of fysiek) middels een score van 0 tot 10. De gemiddelde score voor het video tele-educatieprogramma was 7.13 (SD 1.80) en voor het fysiek gegeven educatieprogramma 5.91 (SD 1.70).

Factoren rondom zelfredzaamheid werden gerapporteerd door Leong (2022) en Timurtas (2022). In de eerste studie werd gevonden dat kennis, attitude en zelfzorgactiviteiten toenamen in beide groepen (standaard zorg of met een communicatieplatform). Zelfredzaamheid nam (uit de resultaten van de tweede studie) in beide groepen evenveel toe (mobile app of smartwatch en controlegroep, 36%).

Focusgroepen

Uit een achterbanraadpleging onder DVN panelleden (n = 46) en een gehouden focusgroep onder mensen met diabetes (n = 9) die zorg ontvangen in de tweede lijn kwam naar voren dat patiënten over het algemeen positief zijn over zorg op afstand en het als tijdbesparend ervaren. Vormen van zorg op afstand die zij (DM1 bij n = 7) onder andere ontvingen waren e-consults (n = 9), videoconsults (n = 2), en telemonitoring (n = 9). Digitale zorgvormen (dus zonder contactmoment tussen patiënt en zorgverlener) waren het ontvangen van informatie (n = 3), digitaal afspraken maken (n = 7), (herhaal)medicatie opvragen (n = 4) en gegevens of (lab)uitslagen bekijken (n = 8). Zeven deelnemers gaven aan in de toekomst vaker digitale zorg te willen gebruiken, twee stonden daar neutraal over. Wel werd aangegeven dat niet alles digitaal kan, maar ook dat fysiek niet per se beter is: om een consult fysiek in plaats van digitaal te houden, moet dat wel wat toevoegen aan de zorg. Voor persoonlijke aandacht en psychologische problematiek is het bijvoorbeeld wenselijker om een fysiek consult te hebben; een digitaal consult is afstandelijker. Digitaal kunnen follow-up waarden worden besproken; echter een voorwaarde voor een effectief digitaal consult is eenheid van taal en duidelijke verwachtingen en taken. Patiënten zien daarom graag een individuele afstemming wat voor hem/haar passende zorg is en waar hij/zij de balans tussen fysiek en digitaal ziet. Daarbij is de wens van de patiënt leidend, maar moeten duidelijke afspraken worden gemaakt en verwachtingen tussen zorgverlener en patiënt worden afgestemd: wanneer kan welke vorm van zorg kan worden ingezet (in welke situaties is videobellen/data-uitwisseling/e-consult geschikt?).

Binnen het SKMS-kwaliteitsproject Uniformiteit van dataplatforms voor geïntegreerde diabeteszorg zijn middels interviews met zorgverleners en mensen met diabetes mellitus de behoefte en voorwaarden geïnventariseerd van een platform dat zorg op afstand mogelijk maakt. De belangrijkste conclusie is dat zowel zorgprofessionals als mensen met diabetes een diabetesdataplatform belangrijk vinden waarop data betreffende de glykemische regulatie gedeeld kunnen worden. Zowel glucosedata als insulinedata dienen in één platform weergegeven te kunnen worden. Verschillende soorten en typen devices moeten met één platform kunnen werken. De behoefte voor communicatie en telemonitoring via het platform wordt minder groot en minder belangrijk gevonden. Het huidige beschikbare aanbod van diabetesdataplatforms voldoet niet of slechts ten dele aan de wensen van zowel de zorgprofessional als de patiënt (Programma uitkomstgerichte zorg, 2023).

Uit een focusgroep onder zorgverleners in de diabeteszorg in de tweede lijn (n = 5; internisten, diëtisten en diabetesverpleegkundigen/verpleegkundig specialisten) kwam naar voren dat zorgverleners digitaal contact als effectief contact ervaren en met telemonitoring een vollediger beeld krijgen (geen momentopname van labuitslagen). Zij zien ook het voordeel in voor de patiënt wat betreft het niet hebben van reistijd en reis- of parkeerkosten. Echter, zij gaven wel aan dat het minder ruimte biedt voor contactgroei en dat het informatieverlies kan geven omdat er geen fysiek onderzoek uitgevoerd kan worden. Zorgverleners geven aan (net als patiënten) dat duidelijke afspraken over wanneer welke vorm van zorg op afstand kan worden ingezet van cruciaal belang is voor het behouden van goede kwaliteit van zorg. Zij achtten het niet geschikt voor alle patiënten en geven aan dat bij onderstaande situaties een fysiek consult moet plaatsvinden:

- Diabetische voetzorg: zoals hierboven al eerder genoemd kan er een hogere mortaliteit bij voetzorg op afstand zijn. Zowel jaarlijks voetonderzoek als beoordeling van een ulcus kan onvoldoende met behulp van zorg op afstand, en dient fysiek plaats te vinden (zie Richtlijn Diabetische voet en Richtlijn Pijnlijke diabetische neuropathie). In acute situaties kan de eerste lijn hierin ook een belangrijke rol vervullen.

- Het niet halen van de glykemische streefdoelen ondanks telemonitoring: bij mensen met diabetes met slechte glucoseregulatie en/of grote schommelingen, ondanks het gebruik van een glucosemeter/sensor met telemonitoring, moet met lichamelijk onderzoek naar de aanwezigheid van spuitinfiltraten en andere oorzakelijke factoren worden gekeken. Ook moet overwogen worden of mentale of omgevingsfactoren bijdragen aan het onvermogen om tot een goede regulatie te komen.

- Fysieke parameters: elk jaar moet het gewicht en de bloeddruk van elke patiënt worden gemeten. Gezien er nog geen goede standaard eisen zijn (en de kosteneffectiviteit laag lijkt) wordt het noodzakelijk geacht om dit jaarlijks tijdens een fysiek consult met een geijkte machine te meten.

- Zorgmijders: aan hen kan in eerste instantie zorg op afstand worden aangeboden. Indien dit geen oplossing blijkt voor hen, dienen zij actief te worden opgevolgd en benaderd voor fysieke consulten.

- Uit het zicht verloren patiënten: voor de zorgverlener is het soms lastig om een inschatting te maken hoe het met de patiënt gaat (na een langere periode) op afstand.

- Mensen met diabetes met onvoldoende (cognitieve, linguïstische of digitale) vaardigheden. Een valkuil kan echter zijn dat zorgverleners onvoldoende in staat zijn om te beoordelen of een patiënt digitaal vaardig is. Naast scholing van de patiënt in digitale vaardigheden, kan ook scholing van de zorgverlener voor de herkenning hiervan wenselijk zijn.

Uiteraard geldt voor elke patiënt het zorgaanbod passend moet zijn bij zijn/haar wensen en zorgvraag; telemonitoring is geen “one size fits all”.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Toegankelijkheid

In theorie verhoogt zorg op afstand de toegankelijkheid van de zorg: patiënten hebben minder reistijd en maken minder kosten. Ook de timing van een consult kan beter worden gepland: patiënten kunnen makkelijker zelf een moment bepalen en hoeven er geen halve of hele dag voor vrij te nemen van werk (Hall, 2020). Daarbij moet wel aan een aantal randvoorwaarden worden voldaan.

Basis randvoorwaarden om zorg op afstand te kunnen ontvangen zijn voor patiënten het hebben van een goede internetverbinding, een mobiele telefoon of computer/tablet, en een rustige ruimte. Om zorg op afstand te kunnen leveren hebben zorgverleners hetzelfde nodig, plus een eenvoudig systeem om data in te zien en een goede communicatie tussen de verschillende gebruikte systemen, wat soms wordt gehinderd door de privacywetgeving en tot veel registratielast leidt. Een verdere uitdaging is de communicatie tussen de verschillende ziekenhuis- en (industriële) monitoringssystemen.

Randvoorwaarden voor vervolgens het effectief gebruik van zorg op afstand volgens patiënten (volgend uit de focusgroep) zijn de aanwezigheid van voldoende technische kennis van/digitale affiniteit met de gebruikte apparatuur en software voor telemonitoring en teleconsulten bij de zorgverleners, en adequate gegevensuitwisseling tussen verschillende zorgverleners. Hiervoor moet iemand in het ziekenhuis zich verantwoordelijk voelen, wat vaak niet zo wordt ervaren door patiënten. In het zorgsysteem moeten ook organisatorische aanpassingen plaatsvinden, omdat dit niet is ingesteld op real-time contact, maar op periodieke controles. Zorgverleners geven ongeveer hetzelfde aan: er moet bekendheid zijn met de mogelijkheden van zorg op afstand, en de benodigde ICT-ondersteuning om deze mogelijkheden te bieden. Aanvullend wordt ook als eis gesteld dat – indien een device voor glucosemonitoring wordt gebruikt – dit device data automatisch uitleest en zorgt voor een continue verstrekking van data. Als dit niet het geval is, blijft het risico van niet-representatieve meetmomenten bestaan.

Om tot betere implementatie van zorg op afstand te komen is volgens zowel patiënten als zorgverleners educatie over het gebruik van digitale zorg bij beide partijen nodig. Patiënten zien hierbij een rol voor Diabetesvereniging Nederland. Zorgverleners geven aan dat voor implementatie dataverzameling gestandaardiseerd moet worden en indicaties moeten worden gesteld wanneer een patiënt meer dan 1x per jaar fysiek moet worden teruggezien.

Rationale van de aanbevelingen

De literatuur geeft geen definitief antwoord op de vraag of fysieke zorg kan worden vervangen door zorg op afstand met betrekking tot de langetermijnseffecten. IUit studies die zorg probeerden te verbeteren door intensievere en meer gestructureerde behandeling met behulp van zorg op afstand bleek wel dat zorg op afstand, in vergelijking met fysieke controle, minstens zo effectief kan zijn in het verbeteren van de glykemische regulatie uitgedrukt als HbA1c en het reduceren van het aantal hypoglykemieën. De vraag welke vormen van zorg op afstand werkzaam zijn en op welk moment is hierbij lastiger te beantwoorden omdat de diverse studies verschillende interventies gebruikten. Niettemin lijken de geïdentificeerde factoren van succes:

- nadruk op telemonitoring (delen van glucosewaarden via apps, flash glucose monitoring (FGM), continue glucose monitoring (CGM)),

- zelfmanagement en feedback op data betreffende de glykemische regulatie, waarbij vooral real-time feedback effectief lijkt

Voor diabetische voetzorg bij volwassenen met diabetes mellitus kan schadelijkheid niet worden uitgesloten (hogere diabetische voetgerelateerde mortaliteit). De zorg beschreven in de richlijn diabetische voet geeft feitelijk ook aan dat fysiek contact een wezenlijk onderdeel is van diabetische voetzorg.

Vormen van zorg op afstand

De telemonitoring data kunnen worden besproken via een e-consult, een telefonisch consult, een videoconsult, of een communicatieplatform (bijv. persoonlijke gezondheidsomgevingen (PGO’s)), echter hierin is geen duidelijk keuze te maken op basis van de literatuur.

Op basis van focusgroepen kan worden geconcludeerd dat zowel patiënten als zorgverleners over het algemeen positief zijn over zorg op afstand.

- Telemonitoring wordt door beide groepen vooral gezien als als een effectieve manier van opvolging van de glucosewaarden en het insuline-gebruik, maar minder voor uitwisseling van andere biomedische data (bloeddruk, gewicht) of communicatiedoeleinden. Ook pleiten de zorgverleners voor het verbeteren van de integratie van FGM/CGM data met elektronisch patiëntenossier (EPD).

- T.a.v. de feedback en communicatie met de patiënt is het telefonisch consult nog het meest gebruikt voor zorg op afstand.

- Het e-consult is inzetbaar bij eenvoudige, niet-urgente vragen die geen lichamelijk onderzoek vereisen, maar er dienen goede afspraken te worden gemaakt over omgangsregels tussen arts en patiënt (o.a. responstijd en type vragen). Het e-consult lijkt, in tegenstelling tot de andere toepassingen, ook inzetbaar om taalbarrières te overbruggen.

- Het videoconsult kan nuttig zijn voor consulten waarbij een visuele beoordeling wel van belang kan zijn.

Zorgverleners (net als patiënten) achtten zorg op afstand niet geschikt voor alle patiënten en geven aan dat bij medische noodzaak, zorgmijders, patiënten met een taalbarrière of met beperkte digitale vaardigheden een fysiek consult moet plaatsvinden. Zorgverleners en patiënten geven aan dat duidelijke afspraken over wanneer welke vorm van zorg op afstand kan worden ingezet van cruciaal belang is voor het behouden van goede kwaliteit van zorg.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Het gebruik van digitale zorg en digitale communicatiemiddelen tussen zorgverlener en zorgvrager wordt steeds belangrijker en maakt zorg op afstand mogelijk. Tijdens de coronapandemie heeft zorg op afstand een snelle ontwikkeling doorgemaakt, door het (gedwongen) gebruik van (digitale) hulpmiddelen op afstand om zorg te kunnen leveren, specifiek ook voor mensen met diabetes. Dit is ook terug te zien in de declaratiegegevens voor diabeteszorg in de periode 2020 (NZA, 2022). Hierdoor is veel geleerd en zijn verschillende verbeterpunten aan het licht gekomen, wat heeft geleid tot het initiatief voor het uniformeren van dataplatforms voor geïntegreerde diabeteszorg. Echter, er bleven ook veel onduidelijkheden bestaan rondom (het verlenen van) zorg op afstand. Tot op heden is er beperkt onderzoek gedaan naar de kwaliteit (veiligheid, bruikbaarheid, effectiviteit en doelmatigheid) van verschillende zorg op afstandtoepassingen. Om zorg op afstand toekomstbestendig te kunnen benutten en de continuïteit en efficiëntie van de diabeteszorg te waarborgen, is beter zicht op de bruikbaarheid, effectiviteit en succesvolle implementatie nodig.

Deze module beoogt een overzicht te geven van over de bruikbaarheid en effectiviteit van zorgtoepassingen op afstand in de tweedelijns diabeteszorg (zowel type 1 als 2). Dit kan praktische handvatten bieden voor zorgverleners die in hun praktijk zorg op afstand leveren. Voor succesvolle en duurzame implementatie van diabeteszorg op afstand moet tenminste worden voldaan aan de volgende randvoorwaarden:

- Diabeteszorg op afstand moet kwalitatief vergelijkbaar zijn met reguliere face-to-facezorg in de spreekkamer (effectiviteit);

- Diabeteszorg op afstand moet voor patiënten en zorgverleners van toegevoegde waarde zijn (ervaringen).

Werkwijze

De bevindingen in deze module zijn gebaseerd op:

- Studie van de internationale wetenschappelijke literatuur

- Inventarisatie lopende projecten in Nederland (Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten-kwaliteitsproject Uniformiteit van dataplatforms voor geïntegreerde diabeteszorg (Nederlande Internisten Vereniging))

- Focusgroepen met zorgverleners en patiënten

De resultaten zijn gebundeld in consensusbijeenkomsten waarin ook aanbevelingen voor praktijk en toekomstig onderzoek werden geformuleerd over zorg op afstand.

Definities en begrippen

Onder zorg op afstand vallen alle zorgactiviteiten tussen patiënt en zorgverlener die op afstand worden gegeven, dit gaat zowel om digitale zorg als digitale of telefonische contacten. Deze ‘afstand’ duidt dus op het ontvangen van de zorgactiviteit terwijl zorgverlener en patiënt zich niet in eenzelfde fysieke ruimte bevinden. Deze zorgactiviteiten kunnen synchroon zijn (patiënt en zorgverlener hebben gelijktijdig contact, bijv. in een videoconsult), ofwel asynchroon (zorgvraag en respons zijn niet gelijktijdig, bijv. online een vraag indienen die later door de zorgverlener wordt behandeld).

De verdere gebruikte definities (van der Burg, 2023):

|

Digitale zorg Digitale zorg is de toepassing van zowel digitale informatie als communicatie om de gezondheid en gezondheidszorg te ondersteunen en/of te verbeteren in de context van zorg. Hierop is wet- en regelgeving van zorg van toepassing zoals de Wet inzake de geneeskundige behandelingsovereenkomst (WGBO) en de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz).

Telemonitoring Telemonitoring is het gedurende langere periode volgen van de gezondheidssituatie van de patiënt door het delen van zelfmetingen ter interpretatie door een zorgverlener voor een vooraf samen afgestemd doel en beleid.

E-consult Het e-consult is een digitaal schriftelijk contact met de zorgverleners op initiatief van de patiënt over een zorginhoudelijke vraag, via een beveiligde verbinding. Het e-consult vervangt een regulier face-to-face consult, telefonisch consult of videoconsult met de zorgverlener.

Videoconsult Het videoconsult is een consult waarbij de zorgverlener op afstand zorgt verleent aan de patiënt via een directe (‘live’) videoverbinding. |

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Literature offers no definite conclusions on the basic question whether remote healthcare delivery results in the same long-term quality of care outcomes as face-to-face care delivery (and therefore no evidence exists whether it would be a viable option to replace face-to-face care). Studies that ameliorate care through remotely delivered (intensified) guidance show circumstantial evidence that remote delivery might be as effective as physical care delivery; the level of evidence is slightly higher for patients with type 2 diabetes compared with type 1.

- Effectiveness (critical)

1a. HbA1c

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that remote healthcare delivery is non-inferior concerning effectiveness (HbA1c control) in adults with diabetes mellitus, compared to physical healthcare delivery.

Source: Michaud (2021), Kebede (2018), Verma (2021), Leong (2022), Di Molfetta (2022), Yang (2022), Maria Gómez (2022), Timurtas (2022), Li (2021), Turnin (2021), Hu (2021), Molavynejad (2020) |

1b. Foot care

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effectiveness of telemedicine compared to physical care delivery for diabetic foot care in adults with diabetes mellitus

Source: Yammine (2022) |

1c. Time in range

|

- GRADE |

Time in range was not reported and could not be graded. |

- Safety (important)

|

Very Low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about a reduction of hypoglycemic events when using remote healthcare delivery in adults with diabetes mellitus, compared to physical care delivery.

Source: Hu (2022), Maria Gomez (2022) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Four systematic reviews were included; their study characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Three focused on glycemic control (Michaud, 2021; Verma, 2021; Kebede, 2018), one on diabetic foot care (Yammine, 2022).

The included forms of remote healthcare or telehealth were broad; Yammine (2022) included all types of remote consultations and Kebede (2018) included all technology based interventions: interventions delivered through the use of a Personal Digital Assistant (PDA), tablet, computer, internet, telemedicine, videoconferencing, or telehealth. In contrast, Verma (2021) focused more specifically on mobile health through mobile applications, text messaging (SMS) or phone calls, and Michaud (2021) specifically on telemonitoring through the transmission of self-monitored data.

Comparators were conventional, standard or usual care (with or without additional disease self-management education) (Michaud, 2021; Verma, 2021; Kebede, 2018) or any type of face-to-face consultation (Yammine, 2022).

Table 1. Study characteristics of the included systematic reviews.

|

Author, year |

Included articles and patients |

Population |

Intervention |

Control |

Outcomes |

Follow-up |

Health care phase |

Health care provider |

|

Michaud, 2021 |

17 RCTs (2453 patients) |

Patients ≥ 18 years with DM2

Sex: 57.7% male Age: mean 46.7 to 66.2 |

Telemonitoring: transmission of self-monitored data |

Usual care |

HbA1c reduction (%) |

3 to 12 months |

Treatment and follow-up |

Not specified |

|

Kebede, 2018 |

21 RCTs (3785 patients) |

Patients with DM2 with HbA1c level of >7.0%

Sex|Age: NR |

Several technology-based interventions |

Usual care |

HbA1c reduction (%) |

3 to 12 months Mean 7.29 ± 3.05 months |

Treatment and follow-up |

Not specified |

|

Verma, 2021 |

18 RCTs (2931 patients) |

Patients with DM2 without severe diabetic complications

Sex|Age: NR |

mHealth interventions through Mobile health applications, text messages or phone calls |

Usual care |

HbA1c difference (%) |

3 to 24 months |

Treatment and follow-up |

Not specified |

|

Yammine, 2022 |

3 RCTs, 1 non-randomized study (816 patients) |

Patients with diabetic foot ulcer

Sex: 63.7% male Age: I 62.2 ± 4.4 C: 61.8 ± 6.3 |

Any type of remote consultation |

Any type of face-to-face consultation (such as home care or in hospital) |

Healing rate (%) Time to heal (days) Amputation rate (%) Mortality rate (%)

|

3 to 12 months Mean: I 5.9 months C: 6.1 months |

Treatment |

Multidisciplinary foot care team (incl. physicians) |

Abbreviations: DM2: diabetes mellitus type 2, mHealth: mobile health, NR: not reported, RCT: randomized controlled trial

Nine RCTs were included, of which the baseline characteristics are presented in table 2.

Table 2. Study characteristics of included RCTs.

|

Author, year |

Patients included |

Population |

Intervention |

Control |

Outcomes |

FU (mo) |

Healthcare phase |

Health care provider |

|

Leong, 2022 |

Intervention: 91 Control: 90

Age ± SD: I: 59.0 ± 11.4 C: 58.1 ± 11.9

Sex (%M): I: 73.6% |C: 63.3% |

Patients with DM2 ≥ 20 years with ≥ 1 HbA1c measurement ≥6.0% in past 6 months, using antidiabetic drugs. |

Communication platform with educational videos and a messaging feature in addition to usual care |

Usual care including several types of consultations |

HbA1c (%) |

3 |

Treatment and follow-up |

Physicians, nurses, pharmacists and diabetes educators |

|

Di Molfetta, 2022 |

Intervention: 62 Control: 61

Age ± SD: I: 47.15 ± 14.54 C: 45.21 ± 14.76

Sex (% M) I: 53.2% | C: 55.7% |

Patients aged 18-70 with insulin-treated diabetes (type 1 or 2) for at least 1 year and inadequate glycaemic control |

Telemedicine assisted self-monitoring of BG, with feedback about their blood glucose levels and therapy suggestions from the study staff via phone/SMS. |

Standard self-monitoring blood glucose, reported on paper daily, without remote assistance. |

HbA1c reduction (%) Hypoglycemia (episodes) |

6 |

Treatment and follow-up |

“Study staff” |

|

Yang, 2022 |

Intervention: 50 Control: 50

Age ± SD: I: 65.09 ± 6.06 C: 67.34 ± 5.33

Sex (% M) I: 38.3% | C: 42.0% |

Normotensive patients with newly diagnosed DM2 within the past 3 months with a HbA1c of 6.5-7.5% and aged 40-60 years |

Telemonitoring with reminders for recording data, and automatic warning feedback messages, plus a monthly 40-minute consultation by phone for lifestyle education |

Standard outpatient consultations including dietary advise or exercise recommendation each visit. |

HbA1c (%) Quality of life (SF-36) Costs (¥) |

12 |

Monitoring |

Nutrition platform and outpatient doctor |

|

Maria Gomez, 2022 |

Intervention: 42 Control: 45

Age ± SD: I: 58.6 ± 10.6 C: 60.5 ± 12.8

Sex (% M): I: 55.0% | C: 54.2% |

Adults with DM2 using insulin and having a HbA1c ≥ 6.5% |

Telemedicine platform (on web, mobile or desktop app) for weekly recording (by the patient) and adjusting insulin doses (by the research group). Patients received pop-up notifications about changes. |

Standard care of the institution plus education for the management of diabetes medications and diet. |

HbA1c (%) Episodes of hypoglycemia Patient satisfaction (ITSQ) |

3 |

Treatment and monitoring |

Endocrin-ologists |

|

Timurtas, 2022 |

Intervention: 60 Control: 30

Age ± SD: MA: 51.6 ± 7.8 SW: 51.4 ± 8.1 Control: 51.8 ± 8.0

Sex: Not reported

|

Patients between 30 and 65 years old with DM2 diagnosed by an endocrinologist. |

Exercise training for 3 times/week, supported by a digital platform (app) in which patients had a personal account.

|

Physically supervised exercise training for 3 times/week prescribed by physiotherapist |

HbA1c (%) Self-efficacy |

12 weeks |

Treatment |

Physio-therapists |

|

Li, 2021 |

Intervention: 130 Control: 85

Age ± SD: I: 47.5 ± 9.88 Cl: 46.7 ± 10.11

Sex (% M): I: 67.7%| C: 63.5% |

Patients ≥18 years with DM2, registered in the clinical database of patients with DM living in territories served by Community Health Care |

App for medical services from the hospital: appointment registration, EMR access, medication reminders, BG monitoring and threshold alarms, diet and exercise monitoring and suggestions, health education, telephone follow-up, real-time communication with care team, and peer support. |

Standard medical care every three months. |

HbA1c <7.0% (rate) Costs (¥) Incremental costs (¥) ICER (¥) |

12 |

Treatment, control and monitoring |

Doctors, nurses, health educators and dietitians |

|

Turnin, 2021 |

Intervention: 141 Control: 141

Age ± SD: I: 59.8 ± 9.2 C: 59.3 ± 10.0

Sex (% M): I: 64.1% | C: 62.2%1 |

Patients ≥18 years with a documented medical history of DM2 (with or without insulin treatment) with a recent HbA1c value of >6.5% and ≤10% |

Home telemonitoring device, that combined biomedical data sensors with educational software (on nutrition and exercise). Data was sent weekly to the platform; patients had access to platform. Physicians had insight in data, received alerts for events and could communicate with the patient. |

Face-to-face consultations in accordance with standard practices. |

HbA1c (%) Patient satisfaction(ad hoc questionnaire) Health professional satisfaction (ad hoc questionnaire) |

12 |

Monitoring |

Physicians |

|

Hu, 2021 |

Intervention: 74 Control: 74

Age ± SD: I: 50.04 ± 5.76 C: 52.21 ± 8.38

Sex (% M): I: 71% | C: 61% |

Patients aged 18-70 with diagnosis of DM2 > 3 months |

Telemedicine platform in which BG values from wireless meter and information (diet, exercise, oral medication) was uploaded and transmitted. If necessary, hospital contacted patient through chat, phone or online connections. Plus monthly diabetes education. |

Once per month: Conventional outpatient treatment; data upload from wireless BG meter by endocrinologist and nurses. Plus monthly diabetes education |

HbA1c (%) Hypoglycemia (episodes ≤3.9 mmol/L) |

6 |

Control |

Endocri-nologists and (diabetes) nurses |

|

Molavynejad, 2020 |

VTE: 126 P: 126 IPE: 125

Age ± SD: VTE: 45.88 ± 9.09 P: 48.31 ± 7.61 IPE: 47.37 ± 7.07

Sex (%M): VTE: 54.2% P: 40.7% IPE: 50.4% |

Patient ≥ 18 years with DM2 for ≥ 1 year, having no other chronic conditions and receiving no official education on self-care |

Video tele-education (VTE): Educational movie (divided into several episodes) in the form of DVDs or cell phone formats for home use. Text messages with reminders to watch the video education and contact if patients had questions.

|

In-person education (IPE): Oral face-to-face education via 4 group sessions of 45 minutes over the course of 2 week), with the opportunity to ask questions, and monthly in-person education at the clinic. |

HbA1c (%) Patient satisfaction (score 0-10) |

3 |

Treatment and follow-up |

Diabetes nurses |

Abbreviations: DM2: diabetes mellitus type 2, EMR: Electronic Medical Record, FU: follow-up, ICER: incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, IPE: in-person education, , M: male, mo: months, SD: standard deviation, P: pamphlets, SMS: short message service, VTE: video tele-education

Results

Below, the results from the 13 included studies are analyzed per outcome measure as specified in the PICO.

- Effectiveness (critical)

1a. HbA1c

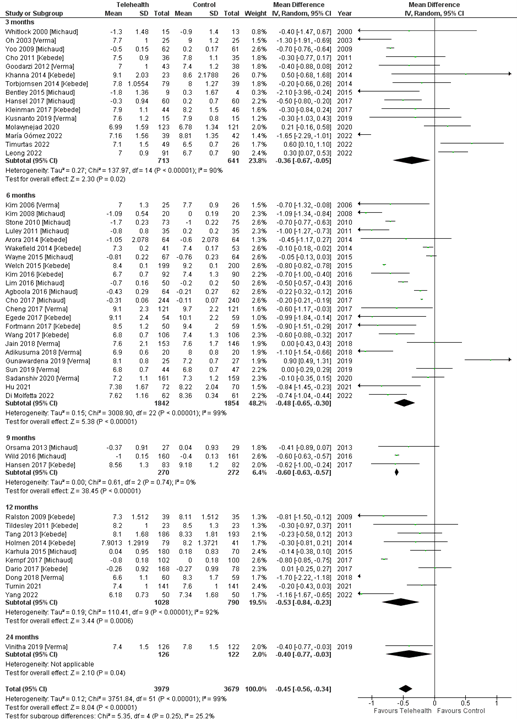

All authors, with the exception of Yammine (2022), reported on the difference in HbA1c (expressed in %) after the telehealth intervention. The results from all studies from the systematic reviews and included RCTS are presented in figure 2.

Figure 2. Forest plot of HbA1c outcomes after telehealth compared to usual care, with results from all separate included studies in the systematic reviews by Michaud (2021), Kebede (2018), and Verma (2021), together with the included RCTs.

A pooled mean difference of -0.45% (95% CI -0.56 to -0.34) in HbA1c value favouring telehealth is found. Despite this finding being statistically significant, it does not reach our threshold for clinical relevance (0.5%).

Only Li (2021) reported the outcome as the proportion of patients having HbA1c <7.0% after 12 months, who found a Relative Risk (RR) of 1.67 (95% CI 1.29 to 2.16) favouring telehealth.

1b. Foot care

One systematic review (Yammine, 2022) researched the effect of remote consultations compared to face-to-face consultations in diabetic foot care. Different outcomes were assessed, depicted in table 3. Time to heal for diabetic foot ulcers was also researched, with a mean number of days of 73 (SD 24.1) for telemedicine, and 83.5 days (SD 28.4) for face-to-face consultations.

Table 3. Relative risks of outcomes for telemedicine compared to face-to-face consultations in diabetic foot care.

|

Outcome |

Relative Risk (RR) |

95% confidence interval |

Favours |

|

Mortality rate |

2.25 |

0.28 to 18.13 |

Face-to-face |

|

Healing rate |

0.99 |

0.91 to 1.09 |

Face-to-face |

|

Amputation rate |

0.59 |

0.29 to 1.18 |

Telemedicine |

Differences in outcomes for diabetic foot healing and amputation rate were not statistically significant. Mortality rate showed a clinically relevant difference (RR > 1.25). However, the confidence intervals are broad, comprising different inferences.

1c. Time in Range

The outcome time in range was not reported in the included studies.

- Safety (important)

Three authors reported in their methods that they recorded frequency of hypoglycemic episodes (Di Molfetta, 2022; Maria Gomez, 2022; Hu, 2022). However, one did not define hypoglycemia and did not present these results (Di Molfetta, 2022). Hypoglycemia in the other two studies was defined as blood glucose level <3.8 mmol/L (Maria Gomez, 2022) or ≤3.9 mmol/L (Hu, 2022).

Hu (2022) reported the incidence of hypoglycemic events based on blood-glucose data: in the telemedicine group automatic uploads from the wireless intelligent blood-glucose meter were used, and the control group had their blood-sugar data exported to a physician who counted the hypoglycemic events. After 6 months, 18 patients (25.0%) in the telemedicine group had had a hypoglycemic event in the past month, compared to 29 patients (41.4%) in the control group (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.98).

Maria Gomez (2022) reported hypoglycemic events as the percentage of patients experiencing one or more of those over the follow-up period of 3 months, and calculated the incidence rate as events per person month. A subdivision in hypoglycemic events of level 1 (3.0 to 3.8 mmol/L), 2 (<3.0 mmol/L), and 3 (severe, requiring assistance) was made, of which the numbers are presented in table 4. In the Mobile health group, 2.5% of patients required hospitalization for diabetes decompensation, compared to 15.2% in the standard care group (RR 0.16, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.28).

Table 4. Risk Ratio (RR) and Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR, events per person-month) of patients experiencing different levels of hypoglycemia over a period of 3 months.

|

Patients experiencing hypoglycemic event |

Mobile Health (%) |

Standard Care (%) |

RR (95% CI) |

Mobile Health (IR) |

Standard Care (IR) |

IRR (95% CI) |

|

Level 1 (3.0 to 3.8 mmol/L) |

75.0 |

72.3 |

1.03 (0.80 to 1.33) |

1.74 |

2.40 |

0.72 (0.66 to 0.87) |

|

Level 2 (<3.0 mmol/L) |

52.2 |

52.3 |

1.01 (0.67 to 1.51) |

0.45 |

0.84 |

0.53 (0.37 to 0.74) |

|

Level 3 (severe) |

15.0 |

25.6 |

0.59 (0.24 to 1.44) |

0.06 |

0.18 |

0.39 (0.15 to 0.91) |

Level of evidence of the literature

- Effectiveness (critical)

1a. HbA1c

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure effectiveness for HbA1c started at high as it was based on systematic reviews and RCTs. It was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (-1, risk of bias; see risk of bias tables under the heading “Evidence tables”), and because of indirectness (-1, studies mostly conducted in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2).

No downgrading took place for conflicting results (inconsistency), as difference in results can be explained by either the type of care assessed (physiotherapy intervention and physiotherapy control in Timurtas, 2022), or the study design (open-label in Leong, 2022 and Gunawardena, 2019). No downgrading took place for imprecision or publication bias. For this last factor, the slight disbalance in the funnel plot can be explained by the studies with shorter follow-up.

1b. Foot care

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure effectiveness for diabetic foot care started at high as it was based on a systematic review. However, it was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (-1, risk of bias); and the confidence intervals from the estimates crossing the border of clinical relevance, therefore leading to different inferences (-2, imprecision). No downgrading took place for inconsistency, indirectness, or publication bias.

1c. Time in range

The outcome Time in range was not reported and could not be graded.

- Safety (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure safety (hypoglycemic events) started at high as it was based on systematic reviews and RCTs. It was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations in the form of possible risk of bias in randomization, no blinding and limited generalizability (-1, risk of bias); indirectness (-1, studies mostly conducted in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2); and the inclusion of two studies with a low number of included patients and the confidence intervals crossing the border of clinical relevance (-1, imprecision). No downgrading took place for inconsistency or publication bias.

Zoeken en selecteren

A prerequisite for remote healthcare delivery is that its quality is equal to that of physical care delivery. Therefore, a systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the quality of remote healthcare delivery/telehealth compared to physical care delivery for patients with diabetes?

P: Adult patients (≥18 years) with diabetes (type 1 and/or 2), living at home

I: Remote healthcare delivery (either digital or by telephone), as a replacement for face-to-face care delivery

C: Face-to-face care delivery

O: Quality of care, comprising: effectivity and safety

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered effectiveness as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and safety as an important outcome measure for decision making.

However, other aspects of quality (efficiency, costs, accessibility, and patient and provider satisfaction) also influence decision making significantly, and will be thoroughly addressed in the considerations of the evidence-to-decision framework.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Effectivity through HbA1c values, Time in Range measurements, or mortality (as outcome in diabetic foot care).

- HbA1c as a reduction, difference or change in HbA1c values, or as the proportion of patients having HbA1c value after intervention of <7.0% or <53 mmol/mol; and

- Safety through the frequency of hypoglycemic episodes

The working group defined a difference of 0.5% or 5 mmol/mol as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for HbA1c values.

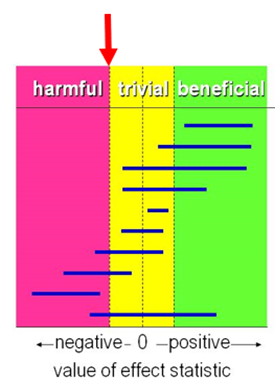

For time in range, hypoglycemic episodes, and mortality (in case of diabetic foot care) the working group used the GRADE default limits as limits for clinical decision making (RR <0.80; RR>1.25). Since the objective was to determine whether remote care delivery was at least as effective as face-to-face care delivery (i.e. similar or better), the results were compared only against the threshold of harmful effect (figure 1).

Figure 1. Visual representation of the values of clinical decision making for any harmful effect.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched for systematic reviews (from 2012 and later) and randomized controlled trials (from 2017 and later) with a broader search strategy for all somatic disorders (instead of only diabetes patients) until June 20th, 2022. This timeframe was chosen as telehealth has been upcoming (mostly) since the last 10 years. The detailed search strategy is available upon request. The systematic literature search resulted in 20.429 hits.

Title and abstract screening took place with the tool ASReview. First, two advisors independently screened a set of articles for inclusion until 10 articles were included, to create a calibration set. After the screening of 181 articles, 11 abstracts were included. The digital tool ASReviewer was used for further selection, resulting in 689 relevant abstracts. The studies concerning diabetic populations were filtered from these abstracts, resulting in 89 systematic reviews and 53 randomized clinical trials (RCTs).

These studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Study type: excluded were observational studies, guidelines, pilot studies, or pre-post design studies

- Population: adult patients living at home with diabetes

- Intervention: remote healthcare delivery as a replacement for face-to-face care delivery, excluding psychologic interventions, public health interventions or preventive care interventions (primary prevention)

- Control: face-to-face care delivery, excluding waiting list control groups or other forms of remote or digital health care as control

- Outcome: conform PICO

- Setting: in the hospital or specialist care setting

- English language

After reading the full text, 85 systematic reviews were excluded and four included. The RCTs published after the last search date from the included systematic reviews were judged based on full text (to prevent inclusion of duplicates); 44 were excluded and nine RCTs were included. See the table with reasons for exclusion under the heading Evidence tables.

Results

Thirteen studies were included in the analysis of the literature: four systematic reviews and nine RCTs. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Di Molfetta S, Patruno P, Cormio S, Cignarelli A, Paleari R, Mosca A, Lamacchia O, De Cosmo S, Massa M, Natalicchio A, Perrini S, Laviola L, Giorgino F. A telemedicine-based approach with real-time transmission of blood glucose data improves metabolic control in insulin-treated diabetes: the DIAMONDS randomized clinical trial. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022 Sep;45(9):1663-1671. doi: 10.1007/s40618-022-01802-w. Epub 2022 Apr 27. PMID: 35476320; PMCID: PMC9044385.

- Eberle C, Stichling S. Telemetric Interventions Offer New Opportunities for Managing Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: Systematic Meta-review. JMIR Diabetes. 2021 Mar 16;6(1):e20270. doi: 10.2196/20270. PMID: 33724201; PMCID: PMC8080418.

- Federatie Medisch Specialisten, NVZ, NFU, en ZN. Handreiking Telemonitoring. Dec 2022. Beschikbaar via: https://demedischspecialist.nl/sites/default/files/2022-12/handreiking_telemonitoring.pdf

- Hall R, Harvey MR, Patel V. Diabetes care in the time of COVID-19: video consultation as a means of diabetes management. Pract Diabetes. 2022 Apr;39(2):33-37c. doi: 10.1002/pdi.2387.

- Hu, Y., Wen, X., Ni, L. et al. Effects of telemedicine intervention on the management of diabetic complications in type 2 diabetes. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries 41, 322328 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13410-020-00893-6

- Joo JY. Effectiveness of Web-Based Interventions for Managing Diabetes in Korea. Comput Inform Nurs. 2016 Dec;34(12):587-600. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000274. PMID: 27392258.

- Kebede MM, Zeeb H, Peters M, Heise TL, Pischke CR. Effectiveness of Digital Interventions for Improving Glycemic Control in Persons with Poorly Controlled Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Meta-regression Analysis. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2018 Nov;20(11):767-782. doi: 10.1089/dia.2018.0216. Epub 2018 Sep 26. PMID: 30257102.

- Leong CM, Lee TI, Chien YM, Kuo LN, Kuo YF, Chen HY. Social Media-Delivered Patient Education to Enhance Self-management and Attitudes of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2022 Mar 23;24(3):e31449. doi: 10.2196/31449. PMID: 35319478; PMCID: PMC8987969.

- Li J, Sun L, Hou Y, Chen L. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of a Mobile-Based Intervention for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Endocrinol. 2021 Jul 1;2021:8827629. doi: 10.1155/2021/8827629. PMID: 34306072; PMCID: PMC8266460.

- María Gómez A, Cristina Henao D, León Vargas F, Mauricio Muñoz O, David Lucero O, García Jaramillo M, Aldea A, Martin C, Miguel Rodríguez Hortúa L, Patricia Rubio Reyes C, Alejandra Páez Hortúa M, Rondón M. Efficacy of the mHealth application in patients with type 2 diabetes transitioning from inpatient to outpatient care: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022 Jul;189:109948. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109948. Epub 2022 Jun 11. PMID: 35700926.

- Michaud TL, Ern J, Scoggins D, Su D. Assessing the Impact of Telemonitoring-Facilitated Lifestyle Modifications on Diabetes Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Telemed J E Health. 2021 Feb;27(2):124-136. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0319. Epub 2020 May 11. PMID: 32397845.

- Molavynejad S, Miladinia M, Jahangiri M. A randomized trial of comparing video telecare education vs. in-person education on dietary regimen compliance in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a support for clinical telehealth Providers. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022 May 2;22(1):116. doi: 10.1186/s12902-022-01032-4. PMID: 35501846; PMCID: PMC9063130.

- Nederlandse Zorgautoriteit (NZA). Open data dbc-informatiesysteem (DIS) [website]. 2022 Nov. Beschikbaar via: https://www.opendisdata.nl/

- Programma Uitkomstgerichte Zorg. Eindrapport aandoeningswerkgroep diabetes mellitus. 2023. Beschikbaar via: https://platformuitkomstgerichtezorg.nl/aan+de+slag/documenten/handlerdownloadfiles.ashx?idnv=2461914

- Timurtas E, Inceer M, Mayo N, Karabacak N, Sertbas Y, Polat MG. Technology-based and supervised exercise interventions for individuals with type 2 diabetes: Randomized controlled trial. Prim Care Diabetes. 2022 Feb;16(1):49-56. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2021.12.005. Epub 2021 Dec 17. PMID: 34924318.

- Turnin, MC., Gourdy, P., Martini, J. et al. Impact of a Remote Monitoring Programme Including Lifestyle Education Software in Type 2 Diabetes: Results of the Educ@dom Randomised Multicentre Study. Diabetes Ther 12, 20592075 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-021-01095-x

- van der Burg L, Bruinsma J, Crutzen R, Cals J. Onderzoek naar de effectiviteit van digitale zorgtoepassingen in de huisartsenzorg: e-consult, videoconsult, telemonitoring en digitale zelftriage. Maastricht: Universiteit Maastricht, 2023. Beschikbaar via: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2023/03/15/onderzoek-naar-de-effectiviteit-van-digitale-zorgtoepassingen-in-de-huisartsenzorg

- Verma D, Bahurupi Y, Kant R, Singh M, Aggarwal P, Saxena V. Effect of mHealth Interventions on Glycemic Control and HbA1c Improvement among Type II Diabetes Patients in Asian Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Nov-Dec;25(6):484-492. doi: 10.4103/ijem.ijem_387_21. Epub 2022 Feb 17. PMID: 35355920; PMCID: PMC8959192.

- Yammine K, Estephan M. Telemedicine and diabetic foot ulcer outcomes. A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Foot (Edinb). 2022 Mar;50:101872. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2021.101872. Epub 2021 Oct 25. PMID: 35219129.

- Yang L, Xu J, Kang C, Bai Q, Wang X, Du S, Zhu W, Wang J. Effects of Mobile Phone-Based Telemedicine Management in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Med Sci. 2022 Mar;363(3):224-231. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2021.09.001. Epub 2021 Sep 14. PMID: 34534510.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies

NB: study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Kebede, 2018

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs Literature search up to June 2017

A: Agboola, 2016 B: Arora, 2014 C: Capozza, 2015 D: Fortmann, 2017 E: Cho, 2011 F: Cho, 2017 G: Egede, 2017 H: Holmen, 2014 I: Kim, 2016 J: Kleinmann, 2017 K: Ralston, 2009 L: Tang, 2013 M: Tildesley, 2011 N: Trobjohnsen, 2014 O: Wang, 2017 P: Welch, 2015 Q: Wild, 2016 R: Dario, 2017 S: Hansen, 2017 T: Khanna, 2014 U: Liou, 2014 V: Wakefield, 2014

Study design: RCT parallel or cross-over

Setting and Country: Academic hospital, Germany

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: No competing interests; information on funding not disclosed |

Inclusion criteria SR: (1) study design (cluster) RCT; (2) patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes (HbA1c >7.0%); (3) interventions were technology-based; (4) HbA1c was reported as outcome; (5) control group received usual care; (6) English ublication

Exclusion criteria SR: (1) Studies targeting either persons with type 1 or both type 1 and 2 diabetes; (2) studies including control groups receiving interventions

22 studies included, 21 studies included in meta-analysis (not C)

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Not reported per study. 3787 subjects; with 52.6% randomized to intervention groups and 47.4% to control groups.

Groups comparable at baseline? Cannot be judged. |

A: text message to move B: text message (twice daily) for education, medication reminders and healthier living C: Text message for education, medication adherence, glucose control, weight and exercise D: text messages E: Internet diabetes management F: health-care provider mediated remote coaching via glucometer and internet G: telehealth and clinical decision support system H: diabetes diary app with or without health counselling I: Internet based glucose monitoring system J: smartphone app for patients and app + web-based portal for providers K: web-based care management L: Online disease management system M: Internet-based glucose monitoring system N: diabetes diary app with or without health counselling O: monitoring via computer/web/mobile phone connected to glucometer via cable P: internet-based integrated diabetes management system Q: monitoring through computer/ web-based/mobile phone connected to glucometer via modem R: videoconferencing S: Videoconferencing T: automated telephone support with dialogic telephone card U: web-based and videoconferencing V: tele-monitoring |

Usual care, standard care, or existing care

|

End-point of follow-up: A: 6 months B: 6 months C: 6 months D: 6 months E: 3 months F: 6 months G: 6 months H: 12 months I: 6 months J: 3 months K: 12 months L: 12 months M: 12 months N: 4 months O: 6 months P: 6 months Q: 9 months R: 12 months S: 8 months T: 3 months U: 6 months V: 6 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported

|

Outcome measure Defined as glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c, %). mean difference [95% CI]:

A: -0.07 (-2.04 to 1.90) B: -0.25 (-0.56 to 0.06) C: not included in meta-analysis D: -0.84 (-1.13 to -0.55) E: -0.30 (-0.50 to -0.10) F: -0.17 (-0.25 to -0.10) G: -0.90 (-1.54 to -0.26) H: -0.30 (-0.81 to 0.21) I: -0.71 (-0.92 to -0.50) J: -0.41 (-0.78 to -0.07) K: -0.81 (-1.50 to -0.12) L: -0.24 (-0.41 to -0.07) M: -0.42 (-1.24 to 0.39) N: -0.20 (-0.66 to 0.26) O: -0.63 (-0.82 to -0.44) P: -0.79 (-1.00 to -0.58) Q: -0.51 (-1.12 to 0.09) R: 0.0 (-0.18 to 0.19) S: -0.65 (-0.90 to -0.39) T: 0.45 (0.02 to 0.88) U: -0.61 (-0.92 to -0.29) V: -0.16 (-2.70 to 2.38)

Pooled effect (random effects model): -0.39 [95% CI -0.51 to -0.26] favoring digital interventions Heterogeneity (I2): 80.8%

|

Author’s conclusion: Participation in digital interventions, particularly web-based interventions, favourably influences HbA1c levels among patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes.

|

|

Michaud, 2021 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs Literature search up to October 2018

A: Whitlock, 2000 B: Kim, 2008 C: Yoo, 2009 D: Stone, 2010 E: Castelnuovo, 2011 F: Luley, 2011 G: Orsama, 2013 H: Karhula, 2015 I: Wayne, 2015 J: Agboola, 2016 K: Bentley, 2016 L: Lim, 2016 M: Wild, 2016 N: Cho, 2017 O: Kempf, 2017 P: Hansen, 2017 Q: Hansel, 2017

Study design: RCT [parallel / cross-over]

Setting and Country: Academic hospital, United States of America

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Non-commercial grant, authors report no competing financial interest (information about other conflicts of interest not disclosed)

|

Inclusion criteria SR: (1) patients ≥18 years with type 2 diabetes, (2) transmission of physiological or physical data to a health care professional as intervention, (3) usual care with or without additional conventional disease self-management education as comparator, (4) diabetes-related outcomes (weight, HbA1c, lipids, complications)

Exclusion criteria SR: Not reported

17 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N – mean age – %male A: 28 – 63 y – 83% B: 40 – 46.7 ±8.4 y – 48% C: 123 – 58.0 ±8.7 y – 59% D: 148 – NR – 99% E: 34 – 53.3 ±8.4 y – 69% F: 70 – 57.5 ±8.0 y – 50% G: 56 – 61.8 ±8.2 y – 54% H: 287 – 66.2 ±8.6 y – 56% I: 131 – 53.2 ±11.3 y – 28% J: 126 – 51.4 ±11.6 y – 49% K: 18 – 52.9 ±8.6 y – 44% L: 100 – 65.1 ±4.9 y – 75% M: 321 – 60.9 ±9.8 y – 67% N: 484 – 53.3 ±8.9 y – 53% O: 202 – 59.0 ±8.7 y – 37% P: 165 – 58.1 ±9.3 y – 53% Q: 120 – 56.5 ±9.4 y – 33%

Groups comparable at baseline? Large differences in % males, but ages are similar |

A: Telemonitoring device, voice and videoconsults B: Monitoring + feedback through website and cell phone C: Text messaging, physiological and physical activity monitoring D: Physiological telemonitoring, telephone calls E: Weight-loss website on phone, teleconference F: remote monitoring, weekly reports mailed G: diabetes self-management promotion program with remote reporting and automated feedback H: mobile phone health coaching and remote health monitoring I: health coaching and smartphone interaction J: text messages in addition to usual care K: diet and exercise advice and smart wearable with or without email motivational support L: electronic reporting and monitoring of health values and text message response M: remote monitoring + feedback N: internet-based monitoring device (automatic recording and relayed information from care providers) O: automatic reporting sale, step counter and glucometer + personalized online portal P: videoconferencing, remote monitoring of physiological data Q: web-based nutritional support tool; feedback provided based on the input step count

|

Usual care with or without additional conventional disease self-management education. |

End-point of follow-up: A: 3 months B: 6 months C: 3 months D: 6 months E: 12 months F: 6 months G: 10 months H: 12 months I:6 months J: 6 months K: 4 months L: 6 months M: 9 monhts N: 6 months O: 12 months P: 8 months Q: 4 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? A: 0% B: 15% C: 10% D: 9% E: 62% F: 3% G: 18% H: 10% I: 26% J: 0% K: 26% L: 15% M: 11% N: 8% O: 17% P: 16% Q: 11%

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c, %). mean difference [95% CI]:

A: -0.40 (-1.47 to 0.67) B: -1.09 (-1.34 to -0.84) C: -0.70 (-0.76 to -0.64) D: -0.70 (-0.77 to -0.63) E: not included in meta-analysis F: -1.0 (-1.27 to -0.73) G: -0.41 (-0.89 to 0.07) H: -0.14 (-0.38 to 0.10) I: -0.05 (-0.13 to 0.03) J: -0.22 (-0.32 to -0.12) K: -2.10 (-3.96 to -0.24) L: -0.50 (-0.57 to -0.43) M: -0.60 (-0.63 to -0.57) N: -0.20 (-0.21 to -0.19) O: -0.80 (-0.85 to -0.75) P: not included in meta-analysis Q: -0.50 (-0.80 to -0.20)

Pooled effect (fixed/random effects not reported): -0.30 [95% CI -0.31 to -0.29] favoring telemonitoring Heterogeneity (I2): 99.1%

|

Authors’ conclusion: inform telemonitoring design for future diabetes management to enhance access to care, ease of use, and to improve patient engagement

|

|

Verma, 2021 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs and clinical trials Literature search up to August 2020

A: Cheng, 2017 B: Vinitha, 2019 C: Kusnanto, 2019 D: Adikusuma, 2018 E: Dong, 2018 F: Goodarzi, 2012 G: Gunawardena, 2019 H: Kumar, 2018 I: Kim, 2006 J: Jarab, 2012 K: Jain, 2018 L: Kleinman, 2017 M: Lee, 2018 N: Sun, 2019 O: Oh, 2003 P: Patnaik, 2014 Q: Sadanshiv, 2020 R: Islam, 2015

Study design: RCT [parallel / cross-over]

Setting and Country: Public Health department, India

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: None.

|

Inclusion criteria SR: RCT or clinical trial; (2) reporting on outcomes after mHealth interventions (mHealth app, text message or phone calls); (3) targeting patients with diabetes type 2; (4) study conducted in Asian population and published in English language

Exclusion criteria SR: (1) diabetes patients wit severe complications (e.g. diabetic foot, heart disease); (2) mixed population of type 1 and 2 diabetes; (3) pregnant patients with type 2 diabetes

18 studies included (13 for quantitative analysis of main outcome; not H, J, M, P, R)

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Not reported per study.

Groups comparable at baseline? Cannot be judged. |

A: Phone calls B: text message C: mobile application D: text message E: mobile application F: text message G: mobile application H: text message I: text message J: phone calls K: phone calls L: mobile application M: mobile application N: mobile application O: phone calls P: text message +phone calls Q: text message R: text message

|

Usual or conventional care

|

End-point of follow-up: A: 5 months B: 24 months C: 3 months D: 6 months E: 12 months F: 3 months G: 6 months H: 12 months I: 6 months J: 6 months K: 6 months L: 6 months M: 12 months N: 6 months O: 3 months P: 3 months Q: 6 months R: 6 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? A: 41 (16.9%) B: 30 (12.1%) C: - D: - E: 1 (0.8%) F: 18 (18%) G: 15 (22.4%) H: 103 (10.8%) I: 9 (15%) J: 15 (8.8%) K: 9 (3%) L: 11 (12.1%) M: 43 (29.1%) N: - O: 12 24%) P: 45 (45%) Q: 18 (5.6%) R: 6 (2.5%)

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c, %). mean difference [95% CI]:

A: -0.60 (-1.17 to -0.03) B: -0.40 (-0.77 to -0.03) C: -0.30 (-1.03 to 0.43) D: -1.10 (-1.54 to -0.66) E: -1.70 (-2.22 to -1.18) F: -0.40 (-0.88 to 0.08) G: 0.90 (0.49 to 1.31) H: not included in meta-analysis I:-0.70 (-1.32 to -0.08) J: not included in meta-analysis K: 0.0 (-0.43 to 0.43) L: -0.30 (-0.84 to 0.24) M: not included in meta-analysis N: 0.0 (-0.29 to 0.29) O: -1.30 (-1.91 to -0.69) P: not included in meta-analysis Q: -0.10 (-0.35 to 0.15) R: not included in meta-analysis

Pooled effect (random effects model): -0.44 [95% CI -0.79 to-0.10] favoring mHealth. Heterogeneity (I2): 87%

|

Authors’ conclusion: mHealth interventions can be seen as a suitable medium to improve the glycemic index among diabetic patients. The available literature about assessing the use of mHealth is limited and inconsistent to draw any robust conclusions. |

|

Yaminne, 2022 |

SR and meta-analysis of studies with comparative design Literature search up to March 2020

A: Wilbright, 2004 (n = 140) B: Rasmussen, 2015 (n = 374) C: Smith-Strøm, 2018 (n = 182)

Study design: RCTs (parallel design) and clinical trials

Setting and Country: Academic hospital, Lebanon

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: None.

NB: study D will not be analyzed as it does not compare remote healthcare delivery with regular healthcare activities; rather it compares home-based care to hospital-based care. |

Inclusion criteria SR: (1) intervention including any type of remote consultation, (2) comparison including any type of face-to-face consultation (e.g. home care or hospital/medical center care)

Exclusion criteria SR: (1) wounds not being diabetic foot ulcers

4 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: 816 patients total I: 387 (47.4%) C: 429 (52.6%)

Mean age A: I: 55.1 | C: 56.5 B: I: 66.8 | C: 66.7 C:I: 67.2 | C: 65.5

Sex (% male): A: I: 45% | C: 55% B: I: 78.2% | C: 71.3% C: I: 74.5% | C: 73.9%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, though participants from study A are younger and have less males |

A: Telemedicine consultation B: Telemedical monitoring (2 consultations at patient’s home) and 1 at outpatient clinic C: telemedicine follow-up care

|

A: face-to-face care at diabetes foot program B: 3 outpatient clinic visits C: standard outpatient care

|

End-point of follow-up: A: 3 months B: 3 months C: 12 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported |

Healing rate Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: A: 0.93 [0.71 to 1.21] B: 0.97 [0.86 to 1.10] C: 1.05 [0.90 to 1.22]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.99 [95% CI 0.91 to 1.09] Favoring telemedicine. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Time to heal A: I: 34 ±29.3 | C: 45.5 ± 43.4 B: I: 74 | C: 91 C: I: 102 | C: 114

Overall mean: I: 73 ± 24.1 days C: 83.5 ± 28.4 days

Amputation rate Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: B: 0.76 [0.44 to 1.30] C: 0.36 [0.13 to 0.97]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.59 [95% CI 0.29 to 1.18] Favoring telemedicine. Heterogeneity (I2): 41%

Mortality rate Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: B: 7.50 [0.95 to 59.39] C: 0.94 [0.28 to 3.12]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 2.25 [95% CI 0.28 to 18.13] Favoring face-to-face care delivery. Heterogeneity (I2): 68%

|

Authors’ conclusion: treating DFU via TM could be at least as effective as to face-to-face attendance.

Not researched (selective reporting?): ulcer recurrence rate, ulcer transfer rate, infection rate

|

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/n.a. |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Kebede, 2018 |

Yes, objective stated with selection criteria for the parts of the PICO |

No, search strategy not presented, search date to June 2017 |

No, only PRISMA flowchart presented |

Partly, table 1 provides study characteristics, but not of the population in the studies |

Not applicable |

Yes, figure 2 risk of bias table (Cochrane tool) |

Unclear, as population characteristics are poorly presented |

Yes, supplementary figure 1 and tests. |

No, declaration of no competing interests for review, but not reported for individual RCTs |

|

Michaud, 2021 |

Yes, clear objectives stated with clear PICO |

Yes, search period (to October 2018) and strategy reported |

Partly, only PRISMA flowchart and overview of included studies |

Yes, Table 1 characteristics of included studies |

Not applicable |

Yes, using the Jadad scale (presented in table 1) |

Unclear, I2 results in 99.1%, possible clinical heterogeneity |

Yes, funnel plot and Egger’s model |

No, declaration of no competing financial interests for review, but not reported for individual RCTs |

|

Verma, 2021 |

Yes, objective stated with selection criteria for the parts of the PICO |

Yes, search period (to August 2020) and strategy reported |

Yes, in annexure 1. |

Partly, table 2 provides study characteristics, but not of the population in the studies |

Not applicable |

Yes, figure 1 risk of bias table (Cochrane tool) |

Unclear, I2 results in 87%, possible clinical heterogeneity |

Partly, visual inspection of funnel plot only |

No, declaration of no conflicts of interests for review, but not reported for individual RCTs |

|

Yammine, 2022 |

Partly, research question clear but broad subparts of PICO. |

No, search strategy insufficient, search date to March 2020 |

No, only PRISMA flowchart presented |

Yes, Table 1 characteristics of included studies |

Not applicable |

Yes, Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tool |

No, last study different intervention group; and I2 72.2% for first outcome. |

No, no funnel plots and no tests. |

No, declaration of no conflicts of interests for review, but not reported for individual RCTs |

Evidence tabel for Randomized Controlled Trials

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Direction of effect |

Comments |

|

Leong, 2022 |

Type of study: Open-label RCT

Setting and country: Taiwan

Funding: Reported

Conflicts of interest: Reported |

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients ≥20 years, (2) at least one HbA1c measurement ≥6% in the past 6 months, (3) possessed smartphone with LINE app

Exclusion criteria: (1) Gestational diabetes, (2) cognitive impairment, (3) controlled diabetes through dietary control without medication

N total at baseline: Intervention (I): 91 Control (C): 90

Important prognostic factors: Age ± SD: I: 59.0 ± 11.4 C: 58.1 ± 11.9

Sex (% male): I: 73.6% | C: 63.3%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

TMU-LOVE program in addition to usual care. The program consisted of educational videos, frequently asked questions, one-on-one chat room, graphic messages, and the ability to direct patients to certain websites. Physicians could send educational videos and communicate with patients by text message, voice, or video call. The program was designed to last for a study duration of 3 months (i.e., 12 weeks), with two or three videos sent every week and a care message sent every 2 weeks to the patients in the intervention group. |

Usual care, including patient consultations with physicians, access to nurses in the outpatient services, as well as medication consultations with pharmacists upon receiving prescriptions. Physicians also referred patients for consultations with certified diabetes educators (CDEs) when necessary. |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: I: 9 | C: 8 Did not return to clinics (n=3 for I, n = 4 for C); Unwilling to complete post-test (n=6 for I, n = 4 for C)

Incomplete outcome data: No incomplete outcome data, 91 patients in the IG and 90 patients in the CG were analysed.

|

Effectiveness HbA1c (mean % ± SD) Intervention: 7.0 ± 0.9 Control: 6.7 ± 0.7

Knowledge (measured using the Simplified Diabetes Knowledge Scale (SDKS)) (mean % correctness ± SD) Intervention: 76.7 ± 11.7 Control: 73.2 ± 12.6

Patient focus Patient attitude towards diabetes (mean score ± SD) (measured using the Chinese version of the Diabetes Care Profile-Attitudes Toward Diabetes Scales (DCP-ATDS)) Intervention: 3.8 ± 0.5 Control: 3.7 ± 0.5