Liquoronderzoek bij vermoeden op de ziekte van Alzheimer

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van liquormarkers in de diagnostiek bij de ziekte van Alzheimer en in de differentiële diagnostiek bij andere oorzaken van dementie?

Aanbeveling

Verricht niet standaard liquoronderzoek bij patiënten met dementie om de ziekte van Alzheimer aan te tonen of uit te sluiten.

Overweeg liquoronderzoek als er een sterke wens is om de ziekte van Alzheimer als oorzaak van de dementie uit te sluiten.

Overweeg bij jongere (<65 jaar) patiënten met dementie liquoronderzoek te verrichten, indien er twijfel is over de ziekte van Alzheimer als oorzaak. Liquor zonder een Alzheimer profiel kan leiden tot noodzakelijke diagnostiek naar een andere oorzaak van de dementie. Liquor met een Alzheimer profiel bij jonge patiënten wijst sterk op de ziekte van Alzheimer.

Bij twijfel over de interpretatie van de testresultaten neem contact op met een klinische expert.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Drie systematische reviews en een post-mortem case-control studie zijn gebruikt om te de accuratesse van liquormarkers om de klinische diagnose ziekte van Alzheimer vast te stellen bij patiënten met cognitieve klachten (Ritchie, 2014; Ritchie, 2017) of een vermoeden op Alzheimer dementie (Kokkinou, 2021; Struyfs, 2015) te evalueren. In totaal zijn 18 studies over amyloidβ42 (14 studies in Ritchie, 2014; 13 studies in Kokkinou, 2021; Struyfs 2015), acht studies over t-tau (zeven studies in Ritchie, 2017; Struyfs, 2015), zeven studies over p-tau (zes studies in Ritchie, 2017; Struyfs, 2015) en zes studies over p-tau/ amyloidβ ratio (vijf studies in Ritchie, 2017; Struyfs, 2015). Er zijn geen studies geïncludeerd over de diagnostische accuratesse van neurofilament light. In de geïncludeerde studies is er sprake van een hoog risico op bias, en de sensitiviteit en specificiteit vertonen een grote spreiding tussen studies. De overall bewijskracht voor de verschillende gerapporteerde liquormarkers (amyloidβ42, t-tau, p-tau en p-tau/amyloidβ ratio) komt daarmee op zeer laag. Op basis van de huidige literatuur kan er geen conclusie worden getrokken over de accuratesse van liquormarkers voor het stellen van de klinische diagnose ziekte van Alzheimer.

Een verlaagd amyloidβ 1-42, verhoogd tau en verhoogd p-tau181 in liquor wordt beschouwd als passend bij de ziekte van Alzheimer (Delaby, 2022). Bij ambigue testuitslagen kan de ratio tussen de verschillende markers, met name p-tau181/amyloidβ 1-42, worden meegewogen. De interpretatie hiervan vergt ervaring en de vooraf kans op basis van de klinische bevindingen dient hierbij altijd meegewogen te worden. Overleg bij twijfel met een collega met ervaring op het gebied van interpretatie van liquor uitslagen.

Er is onvoldoende onderbouwing voor een harde leeftijdsgrens. Daarom hanteert het cluster pragmatisch een leeftijdsgrens waarbij gesproken wordt over jonge (<65 jaar) en oude (>75 jaar) patiënten met dementie. Het cluster beschouwt de liquorwaarden boven de 75 jaar als onvoldoende sensitief en specifiek. Tussen de 65 en 75 kan de liquoruitslag in specifieke gevallen mogelijk van diagnostische meerwaarde zijn, maar met name vanwege de lagere specificiteit is voorzichtigheid geboden bij de interpretatie (Bouwman, 2009). Overleg bij twijfel met een collega met ervaring op het gebied van interpretatie van liquor uitslagen.

De huidige module gaat over patiënten bij wie dementie al is vastgesteld. Ook bij deze patiënten is de specificiteit waarschijnlijk laag, aangezien patiënten met Lewy body dementie (LBD) en vasculaire dementie ook afwijkend amyloidβ en (p-)tau in de liquor kunnen hebben. Dit komt bij 25-40% van de patiënten met LBD voor (van Harten, 2011; van Steenoven, 2016). Voor het klinisch onderscheid tussen LBD en AD heeft het geen toegevoegde waarde.

De toegevoegde waarde van liquoronderzoek is hoger bij relatief jonge patiënten (<65 jaar) met dementie (Bouwman, 2009). Liquor met normale waarden voor amyloidβ en (p-)tau maken de ziekte van Alzheimer als oorzaak onwaarschijnlijk (Spies, 2013; Spies, 2024; Vos, 2014). Dit heeft als consequentie dat bij die patiënten met dementie verder gezocht kan worden naar een andere oorzaak. De kans op een behandelbare oorzaak voor dementie, zoals een auto-immuun encefalitis, is echter klein.

Het liquor onderzoek kan helpen bij het onderscheid met fronto-temporale dementie (FTD). Een afwijkend amyloidβ past niet bij FTD, terwijl een verhoogd tau wel bij FTD kan worden gezien (Schoonenboom, 2012). Ook hier moet men rekening houden met afwijkende uitslagen bij toename van de leeftijd. De PICO voor de huidige module is niet specifiek gericht op de diagnostische waarde van liquor bij het onderscheid tussen AD en FTD of DLB. Hierover kan dan ook geen kwantitatieve uitspraak worden gedaan. Bij twijfel is het advies om met een academische geheugenpolikliniek te overleggen. Neurofilament light (NfL), in zowel liquor of bloed, is hier niet verder onderzocht omdat er geen meta-analyses gedaan zijn. Onderzoek laat zien dat NfL diagnostische waarde heeft voor het onderscheid tussen FTD en psychiatrische symptomen (Ducharme, 2020; Willemse, 2021), en de waarden zijn ook hoger in FTD dan in AD (Bridel, 2019). Het overgrote deel van het onderzoek naar liquor is gedaan bij witte mensen. Er is weinig bekend over testkarakteristieken bij patiënten met een andere etniciteit.

De huidige module gaat niet over het voorspellen van dementie bij mensen met lichte cognitieve stoornissen (MCI). Zie hiervoor de richtlijn MCI (NVN, 2018). Bij deze patiënten speelt een prognostische vraag.

Voor deze module wordt gebruikt gemaakt van klinische criteria voor dementie en voor de ziekte van Alzheimer voor toepassing in de klinische praktijk. Op dit moment is er geen aanbeveling om recentere onderzoekscriteria standaard toe te passen in de klinische praktijk waarin de definitie van de ziekte van Alzheimer verschuift van een klinische naar een biologische definitie.

Bij een verdenking van dementie diagnose kan liquordiagnostiek de diagnose van de ziekte van Alzheimer uitsluiten. Echter is het belangrijk om de leeftijd als belangrijke factor voor de interpretatie mee te nemen met name bij een afwijkend Alzheimer liquor profiel in combinatie met het klinisch beeld. Bij twijfel met betrekking tot de interpretatie van de liquoruitslagen wordt geadviseerd contact op te nemen met een collega met expertise op het gebied van dementie op jonge leeftijd (<65 jaar).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Bespreek duidelijk met patiënten de toegevoegde waarde van wat liquoronderzoek wel en niet kan. Bespreek expliciet wat het doel is en of dat doel bereikt kan worden met liquoronderzoek. Met name bij oudere patiënten met dementie (> 75 jaar) zal de toegevoegde waarde overwegend beperkt zijn. Zorg dat de patiënt goed begrijpt dat de uitslag van liquoronderzoek niet helpt om de prognose van de dementie te bepalen en niet nodig is om de indicatie voor eventuele behandeling met cholinesteraseremmers te starten. Dit gebeurt op basis van een klinische diagnose. Leg bij jongere patiënten met dementie (<65 jaar) uit dat een normale liquor kan betekenen dat er verder onderzoek naar een andere oorzaak van de dementie moet plaatsvinden. Liquoronderzoek wordt door patiënten soms als belastend ervaren. Patiënten willen vooral goed begrijpen waarom het onderzoek wel of niet nodig is om een diagnose te kunnen stellen. Het is een invasief onderzoek, maar met een zeer lage kans op complicaties. In de toekomst kan de niet-invasieve afname van bloed wellicht liquorafname deels vervangen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er zijn geen berekeningen naar kosteneffectiviteit van het gebruik van liquor onderzoek bij de diagnostiek bij patiënten met dementie gedaan. Omdat de toegevoegde waarde van liquor onderzoek nooit is onderzocht, kan ook niet worden geschat wat de eventuele kosteneffectiviteit is.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het uitvoeren van liquor onderzoek bij patiënten met dementie in de tweede en derde lijn (het domein van deze module) is in alle ziekenhuizen in Nederland mogelijk. Aangezien het slechts bij een beperkte groep patiënten in Nederland van mogelijke toegevoegde waarde is, is hiervoor geen aparte infrastructuur of extra zorgpersoneel nodig. Deze zorg is al voor iedereen in Nederland toegankelijk. De ingreep heeft een zeer laag risico op ernstige bijwerkingen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er is geen onderzoek van voldoende methodologische kwaliteit waaruit blijkt wat de toegevoegde waarde van liquor onderzoek is bovenop klinische beoordeling met onderzoek van de cognitieve functies bij patiënten met dementie. De gerapporteerde sensitiviteit en specificiteit voor de testen in isolatie (dus los van de vooraf kans op basis van klinisch onderzoek inclusief beoordeling van de cognitieve functies) hebben een grote spreiding en zijn overwegend matig tot slecht. Met name de relatief lage specificiteit maken de test minder geschikt voor grootschalige toepassing. Vanwege het huidige gebrek aan prognostische waarde in ouderen en gebrek aan therapeutische consequenties op dit moment, is het uitvoeren van liquoronderzoek bij oudere patiënten met dementie (>75 jaar) waarschijnlijk van beperkte toegevoegde waarde. Een uitzondering hierop vormen patiënten met dementie op relatief jonge leeftijd (<65 jaar), bij wie bevestiging van de ziekte van Alzheimer belangrijk kan zijn, maar ook uitsluiten van de ziekte van Alzheimer belangrijk is omdat er dan verder onderzoek naar een andere oorzaak van dementie dient plaats te vinden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Dementia is a clinical diagnosis. Several diseases can cause demen’ia. Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia. Distinguishing AD from other forms of dementia can have consequences for the patient. Patients with mild cognitive impairment have a higher risk of developing dementia when they have abnormal AD cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-biomarkers. The most studied CSF-biomarkers are amyloid β (1 to 42, Aβ42), total tau (Ttau), phosphorylated tau (Ptau), and neurofilament light (NfL). These CSF-biomarkers are nowadays used in clinical care in specialised centres. Aβ42 and Ptau proteins are the core proteins in the characteristic AD plaques and tangles, and the concentrations in CSF can be used to detect these AD pathologies. NfL and Ttau reflect an axonal loss and neuronal cell decay, which also occurs in other neurodegenerative diseases, and are thus less specific diagnostic markers.

Currently, it is unclear what the examination of CSF AD-biomarkers adds to the diagnostic accuracy in clinical practice in addition to non-invasive clinical assessment with cognitive examination for the diagnosis of dementia. The search question and PICO was limited to AD. In the considerations-section the role of CSF-biomarkers in differential diagnosis of different other major forms of dementia (such as lewy body dementia (LBD) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD)) is discussed in more general terms.

The golden standard for neurodegenerative diseases is a pathological anatomic (PA) diagnosis post-mortem. In absence of data on autopsy examinations and the long interval between diagnosis and post-mortem evaluation, the clinical diagnosis of AD in a multidisciplinary setting has been the gold standard. Regarding the usage of clinical guideline, it is important that the index test is not part of the clinical consensus diagnosis, to prevent circularity and an artificial increase in diagnostic accuracy.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Amyloidβ42

1.1 Specificity and sensitivity

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is uncertain about whether CSF amyloidβ42 is accurate in diagnosing ADD in patients suspected of having dementia.

Sources: Ritchie 2014, Kokkinou 2021, Struyfs 2015 |

1.2 Positive predictive value

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the positive predictive value of CSF amyloidβ42 to diagnose Alzheimer disease in patients referred to a secondary care setting.

Sources: - |

1.3 Negative predictive value

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the negative predictive value of CSF amyloidβ42 to diagnose Alzheimer disease in patients referred to a secondary care setting.

Sources: - |

2. Total-tau (CSF t-tau)

2.1 Specificity and sensitivity

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is uncertain about whether CSF t-tau is accurate in diagnosing ADD in patients suspected of having dementia.

Sources: Ritchie 2017, Struyfs 2015 |

2.2 Positive predictive value

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the positive predictive value of CSF t-tau to diagnose Alzheimer disease in patients referred to a secondary care setting.

Sources: - |

2.3 Negative predictive value

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the negative predictive value of CSF t-tau to diagnose Alzheimer disease in patients referred to a secondary care setting.

Sources: - |

3. Phosphorylated tau (CSF p-tau)

3.1 Specificity and sensitivity

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is uncertain about whether CSF p-tau is accurate in diagnosing ADD in patients suspected of having dementia.

Sources: Ritchie 2017, Struyfs 2015 |

3.2 Positive predictive value

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the positive predictive value of CSF p-tau to diagnose Alzheimer disease in patients referred to a secondary care setting.

Sources: - |

3.3 Negative predictive value

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the negative predictive value of CSF p-tau to diagnose Alzheimer disease in patients referred to a secondary care setting.

Sources: - |

4. CSF Amyloidβ /t-tau ratio

4.1 Specificity and sensitivity

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is uncertain about whether CSF Amyloidβ /t-tau ratio is accurate in diagnosing ADD in patients suspected of having dementia.

Sources: Struyfs 2015 |

4.2 Positive predictive value

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the positive predictive value of CSF Amyloidβ/t-tau ratio to diagnose Alzheimer disease in patients referred to a secondary care setting.

Sources: - |

4.3 Negative predictive value

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the negative predictive value of CSF Amyloidβ/t-tau ratio to diagnose Alzheimer disease in patients referred to a secondary care setting.

Sources: - |

5. CSF p-tau/Amyloidβ ratio

5.1 Specificity and sensitivity

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is uncertain about whether CSF p-tau/Amyloidβ ratio is accurate in diagnosing ADD in patients suspected of having dementia.

Sources: Ritchie 2017, Struyfs 2015 |

5.2 Positive predictive value

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the positive predictive value of CSF p-tau/Amyloidβ ratio to diagnose Alzheimer disease in patients referred to a secondary care setting.

Sources: - |

5.3 Negative predictive value

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the negative predictive value of CSF p-tau/Amyloidβ ratio to diagnose Alzheimer disease in patients referred to a secondary care setting.

Sources: - |

6. Neurofilament light

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value or negative predictive value) of neurofilament light to diagnose Alzheimer disease in patients referred to a secondary care setting.

Sources: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Kokkinou (2021) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the diagnostic accuracy of plasma and CSF amyloidß42 levels for distinguishing ADD from other dementia subtypes in people who meet the criteria for a dementia syndrome. A systematic literature search was performed up until 18 February 2020. Cross-sectional studies were included if they 1) differentiated people with ADD from other dementia subtypes, 2) had clinical assessment for dementia subtype, 3) measured CSF or plasma amyloidß42 levels, 4) had a reference standard based on diagnostic criteria for each dementia subtype such as the DSM-IV criteria, 5) sufficient data to construct two by two tables expressing amyloidß42 results by dementia subtype. Thirty-nine studies (5000 participants) were included that used CSF amyloidß42 to differentiate ADD from other dementia subtypes. Thirteen studies with 1704 participants assessed the accuracy of CSF amyloidß42 for distinguishing ADD from non-ADD. The other studies included comparison to specific dementia types. Positive cases were determined based on the amyloidß42 thresholds employed in the respective primary studies. Characteristics of the individual studies are summarized in the evidence tables.

Ritchie (2014) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the diagnostic accuracy of plasma and CSF Aß levels for detecting mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients who would convert to Alzheimer's disease dementia (ADD) or other forms of dementia over time. A systematic literature search was performed up until 3 December 2012. Studies were included if they had 1) prospectively well-defined cohorts, 2) any accepted definition of MCI but no dementia, 3) baseline CSF or plasma Aß levels, or both, documented at or around the time the MCI diagnosis was made, 4) reference standard for Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis based on the National Institute for National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke/ Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS- ADRDA) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria, 5) sufficient data to construct two by two tables expressing biomarker results by disease status. Studies were excluded if they included patients with possible other causes for dementia: psychiatric, neurological, metabolic, immunological, hormonal or cerebrovascular disorders, genetic cause or early onset ADD (if studies included patients below the age of 50 years, they were excluded). Although Ritchie 2014 was not limited to studies reporting amyloidß42, no studies were identified that reported on diagnostic accuracy for ADD for CSF amyloidß40 or CSF amyloidß42/amyloidß40 ratio. Fourteen studies with 1349 participants evaluated the use of CSF amyloidß42 to detect conversion to ADD. Of the 1349 participants, 436 developed Alzheimer’s dementia. Positive cases were determined based on the amyloidß42 thresholds employed in the respective primary studies. Because of variation in assay thresholds, the authors did not estimate summary sensitivity and specificity. Instead, the authors derived estimates of sensitivity at fixed values of specificity from the model fitted to produce a summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The authors used a hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic (HSROC) model that accounted for between study variability through the inclusion of random effects and derived sensitivities with 95% confidence intervals (CI) at median, lower and upper quartile values of the specificities from the included studies. Characteristics of the individual studies are summarized in the evidence tables.

Ritchie (2017) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the diagnostic accuracy of 1) CSF t-tau, 2) CSF p-tau, 3) the CSF t-tau/Aβ ratio and 4) the CSF p-tau/Aβ ratio index tests for detecting MCI patients who would convert to ADD or other forms of dementia over time. A systematic literature search was performed in January 2013. Studies were included if they had 1) prospectively well-defined cohorts, 2) any accepted definition of MCI but no dementia, 3) CSF t-tau or p-tau and CSF tau (t-tau or p-tau)/Aβ ratio documented at or around the time the MCI diagnosis was made, 4) reference standard for Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis based on the NINCDS- ADRDA or DSM-IV criteria, 5) sufficient data to construct two by two tables expressing biomarker results by disease status. Fifteen studies were included with 1282 participants with MCI at baseline. 1172 participants had analysable data, 430 participants developed Alzheimer’s dementia and 130 participants other forms of dementia. Follow-up ranged from less than one year to over four years, but in the majority of studies was in the range of one to three years. Diagnostic accuracy was evaluated for CSF t-tau in seven studies (291 cases and 418 non-cases), CSF p-tau in six studies (164 cases and 328 non-cases), CSF p-tau/Aβ ratio in five studies (140 cases and 293 non-cases) and CSF t-tau/Aβ ratio in only one study. Characteristics of the individual studies are summarized in the evidence tables.

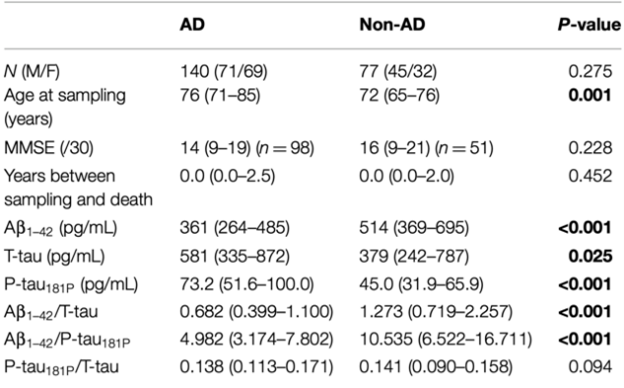

Struyfs 2015 performed a post mortem case-control study to examine the value of CSF p-tau as an ADD biomarker for a differential dementia diagnosis. 140 autopsy confirmed AD dementia and 77 autopsy confirmed non-AD dementia patients with CSF t-tau, p-tau and Aβ levels from lumbar puncture were included. All diagnoses were made according to established neuropathological criteria. For ADD, vascular dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies the Montine criteria were applied, frontotemporal dementia according to Cairns or Mackenzie and Creutzfeldt Jakob disease according to Markesbery. The ADD group also contained mixed dementia diagnoses where patients fulfilled the criteria for ADD in combination with minor pathology for other diseases such as cerebrovascular or Parkinson’s disease. Diagnostic test accuracy was assessed with ROC curve analyses to obtain the optimal cutoff values to discriminate AD. The cutoff values were determined by maximizing the Youden index: calculating the maximal sum of sensitivity and specificity. Characteristics are further summarized in the evidence tables.

Results

1. Amyloidβ42

1.1 Specificity and sensitivity

The systematic review and meta-analysis of Ritchie (2014) included fourteen studies with 1349 participants to assess the accuracy of CSF amyloidß42 to detect conversion from MCI to ADD compared to non-ADD. Of the 1349 participants, 436 were diagnosed with ADD. Individual study estimates of sensitivity were between 36% and 100% while the specificities were between 29% and 91%. Results are shown in Table 1.

The systematic review and meta-analysis of Kokkinou (2021) included thirteen studies with 1704 participants to assess the accuracy of CSF amyloidß42 for distinguishing ADD from non-ADD in people who meet the criteria for a dementia syndrome. Of the 1704 participants, 880 were diagnosed with ADD. Individual study estimates of sensitivity were between 42% and 100% while the specificities were between 25% and 82%. Results are shown in Table 1.

Struyfs 2015 assessed accuracy of CSF amyloidß42 for distinguishing ADD from non-ADD in 140 autopsy confirmed AD dementia and 77 autopsy confirmed non-AD dementia patients. The sensitivity was 79,3% and specificity 53,2% with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0,677 (95%CI 0,597-0,757) and an amyloidß42 cut-off of 500,27. Results are shown in Table 1.

1.2 Positive predictive value

Neither Ritchie (2014) or Kokkinou (2021) reported on the outcome positive predictive value.

1.3 Negative predictive value

Neither Ritchie (2014) or Kokkinou (2021) reported on the outcome negative predictive value.

Table 1. Sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing ADD based on CSF amyloidß42 (Ritchie, 2014 and Kokkinou, 2019).

|

Systematic review |

Study |

N |

TP |

FP |

FN |

TN |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

Amyloidß42 threshold |

|

NA |

Struyfs 2015 |

217 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.793 |

0.532 |

500.27 ng/l |

|

Ritchie (2014) |

Bjerke 2009 |

162 |

18 |

43 |

2 |

99 |

0.90 (0.68 to 0.99) |

0.70 (0.61 to 0.77) |

512.0 ng/l |

|

Blom 2009 |

28 |

9 |

9 |

5 |

5 |

0.64 (0.35 to 0.87) |

0.36 (0.13 to 0.65) |

82.0 pM |

|

|

Chiasserini 2010 |

41 |

17 |

2 |

6 |

16 |

0.74 (0.52 to 0.90) |

0.89 (0.65 to 0.99) |

741.0 ng/l |

|

|

Galluzzi 2010 |

64 |

18 |

17 |

4 |

25 |

0.82 (0.60 to 0.95) |

0.60 (0.43 to 0.74) |

500.0 ng/l |

|

|

Hampel 2004 |

52 |

24 |

10 |

5 |

13 |

0.83 (0.64 to 0.94) |

0.57 (0.34 to 0.77) |

679.0 ng/l |

|

|

Hansson 2007 |

134 |

53 |

36 |

4 |

41 |

0.93 (0.83 to 0.98) |

0.53 (0.42 to 0.65) |

0.64 ng/ml |

|

|

Hertze 2010 |

160 |

47 |

33 |

5 |

75 |

0.90 (0.79 to 0.97) |

0.69 (0.60 to 0.78) |

209.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Kester 2011 |

100 |

32 |

16 |

10 |

42 |

0.76 (0.61 to 0.88) |

0.72 (0.59 to 0.83) |

495.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Monge-Argiles 2011 |

37 |

9 |

10 |

2 |

16 |

0.82 (0.48 to 0.98) |

0.62 (0.41 to 0.80) |

320.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Papaliagkas2009 |

53 |

5 |

11 |

0 |

37 |

1.00 (0.48 to 1.00) |

0.77 (0.63 to 0.88) |

472.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Parnetti 2006 |

55 |

4 |

4 |

7 |

40 |

0.36 (0.11 to 0.69) |

0.91 (0.78 to 0.97) |

500.0 pg/l |

|

|

Shaw 2009 |

196 |

32 |

113 |

5 |

46 |

0.86 (0.71 to 0.95) |

0.29 (0.22 to 0.37) |

192.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Vos 2013 |

214 |

62 |

41 |

29 |

82 |

0.68 (0.58 to 0.78) |

0.67 (0.58 to 0.75) |

500.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Zetterberg 2003 |

53 |

15 |

12 |

7 |

19 |

0.68 (0.45 to 0.86) |

0.61 (0.42 to 0.78) |

532.0 ng/l |

|

|

Kokkinou (2021) |

Brettschneider 2006 |

165 |

89 |

30 |

20 |

26 |

0.82 (0.73 to 0.88) |

0.46 (0.33 to 0.60) |

612.0 pg/ml |

|

Kapaki 2003 |

64 |

35 |

3 |

14 |

12 |

0.71 (0.57 to 0.83) |

0.80 (0.52 to 0.96) |

435.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Knapskog 2018 |

71 |

25 |

8 |

34 |

4 |

0.42 (0.30 to 0.56) |

0.33 (0.10 to 0.65) |

550.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Lewczuk 2004 |

33 |

19 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

0.86 (0.65 to 0.97) |

0.82 (0.48 to 0.98) |

500.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Lombardi 2018 |

35 |

28 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

0.88 (0.71 to 0.96) |

0.67 (0.09 to 0.99) |

650.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Maddalena2003 |

81 |

40 |

9 |

11 |

21 |

0.78 (0.65 to 0.89) |

0.70 (0.51 to 0.85) |

490.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Montine 2001 |

27 |

19 |

6 |

0 |

2 |

1.00 (0.82 to 1.00) |

0.25 (0.03 to 0.65) |

1125.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Perani 2016 |

75 |

40 |

15 |

7 |

13 |

0.85 (0.72 to 0.94) |

0.46 (0.28 to 0.66) |

500.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Rosler 2001 |

51 |

21 |

10 |

6 |

14 |

0.78 (0.58 to 0.91) |

0.58 (0.37 to 0.78) |

375.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Smach 2008 |

108 |

60 |

10 |

13 |

25 |

0.82 (0.71 to 0.90) |

0.71 (0.54 to 0.85) |

505.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Spies 2010 |

138 |

57 |

18 |

12 |

51 |

0.83 (0.72 to 0.91) |

0.74 (0.62 to 0.84) |

NR |

|

|

Tapiola 2000 |

107 |

55 |

11 |

25 |

16 |

0.69 (0.57 to 0.79) |

0.59 (0.39 to 0.78) |

340.0 pg/ml |

|

|

Tariciotti 2018 |

749 |

197 |

233 |

46 |

273 |

0.81 (0.76 to 0.86) |

0.54 (0.49 to 0.58) |

500.0 pg/ml |

Abbreviations: NA = Not applicable, NR = Not specified by authors, N= number of participants in study, TN = true negatives, TP = true positives, FN = false negatives, FP = false positives, CI = confidence interval.

2. Total-tau (CSF t-tau)

2.1 Specificity and sensitivity

The systematic review and meta-analysis of Ritchie (2017) included seven studies with 709 participants to assess the accuracy of CSF t-tau to detect conversion from MCI to ADD compared to non-ADD. Of the 709 participants, 291 were diagnosed with ADD. Individual study estimates of sensitivity were between 51% and 95% while the specificities were between 48% and 88%. Results are shown in Table 2.

Struyfs (2015) assessed accuracy of CSF t-tau for distinguishing ADD from non-ADD in 140 autopsy confirmed AD dementia and 77 autopsy confirmed non-AD dementia patients. The sensitivity was 62,1% and specificity 63,6% with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0,592 (95%CI 0,508-0,675) and a t-tau cut-off of 472,35. Results are shown in Table 2.

2.2 Positive predictive value

Ritchie (2017) did not report on the outcome positive predictive value.

2.3 Negative predictive value

Ritchie (2017) did not report on the outcome negative predictive value.

Table 2. Sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing ADD based on CSF t-tau (Ritchie, 2017).

|

Systematic review |

Study |

N |

TP |

FP |

FN |

TN |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

|

NA |

Struyfs 2015 |

217 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.621 |

0.636 |

|

Ritchie (2017) |

Amlien 2013 |

39 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

26 |

0.56 (0.21 to 0.86) |

0.87 (0.69 to 0.96) |

|

Hampel 2004 |

52 |

26 |

12 |

3 |

11 |

0.90 (0.73 to 0.98) |

0.48 (0.27 to 0.69) |

|

|

Hansson 2006 |

134 |

29 |

9 |

28 |

68 |

0.51 (0.37 to 0.64) |

0.88 (0.79 to 0.95) |

|

|

Kester 2011 |

100 |

35 |

29 |

7 |

29 |

0.83 (0.69 to 0.93) |

0.50 (0.37 to 0.63) |

|

|

Monge-Argiles 2011 |

37 |

8 |

8 |

3 |

18 |

0.73 (0.39 to 0.94) |

0.69 (0.48 to 0.86) |

|

|

Palmqvist 2012 |

133 |

42 |

23 |

10 |

58 |

0.81 (0.67 to 0.90) |

0.72 (0.60 to 0.81) |

|

|

Vos 2013 |

214 |

65 |

28 |

26 |

95 |

0.71 (0.61 to 0.80) |

0.77 (0.69 to 0.84) |

Abbreviations: NA = Not applicable, N= number of participants in study, TN = true negatives, TP = true positives, FN = false negatives, FP = false positives, CI = confidence interval.

3. Phosphorylated tau (CSF p-tau)

3.1 Specificity and sensitivity

The systematic review and meta-analysis of Ritchie (2017) included six studies with 492 participants to assess the accuracy of CSF p-tau to detect conversion from MCI to ADD compared to non-ADD. Of the 492 participants, 164 were diagnosed with ADD. Individual study estimates of sensitivity were between 40% and 100% while the specificities were between 22% and 86%. Results are shown in Table 3.

Struyfs (2015) assessed accuracy of CSF p-tau for distinguishing ADD from non-ADD in 140 autopsy confirmed AD dementia and 77 autopsy confirmed non-AD dementia patients. The sensitivity was 77,9% and specificity 61,0% with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0,720 (95%CI 0,648-0,792) and a p-tau cut-off of 50,35. Results are shown in Table 3.

3.2 Positive predictive value

Ritchie (2017) did not report on the outcome positive predictive value.

3.3 Negative predictive value

Ritchie (2017) did not report on the outcome negative predictive value.

Table 3. Sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing ADD based on CSF p-tau (Ritchie, 2017).

|

Systematic review |

Study |

N |

TP |

FP |

FN |

TN |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

|

NA |

Struyfs 2015 |

217 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.779 |

0.610 |

|

Ritchie (2017) |

Fellgiebel 2007 |

16 |

4 |

8 |

0 |

4 |

1.00 (0.40 to 1.00) |

0.33 (0.10 to 0.65) |

|

Hansson 2006 |

134 |

39 |

11 |

18 |

66 |

0.68 (0.55 to 0.80) |

0.86 (0.76 to 0.93) |

|

|

Koivunen 2008 |

14 |

2 |

7 |

3 |

2 |

0.40 (0.05 to 0.85) |

0.22 (0.03 to 0.60) |

|

|

Monge-Argiles 2011 |

37 |

9 |

11 |

2 |

15 |

0.82 (0.48 to 0.98) |

0.58 (0.37 to 0.77) |

|

|

Palmqvist 2012 |

133 |

35 |

11 |

17 |

70 |

0.67 (0.53 to 0.80) |

0.86 (0.77 to 0.93) |

|

|

Visser 2009 |

158 |

31 |

77 |

4 |

46 |

0.89 (0.73 to 0.97) |

0.37 (0.29 to 0.47) |

Abbreviations: NA = Not applicable, N= number of participants in study, TN = true negatives, TP = true positives, FN = false negatives, FP = false positives, CI = confidence interval.

4. CSF amyloidß/ t-tau ratio

4.1 Specificity and sensitivity

Struyfs (2015) assessed accuracy of CSF amyloidß42/ t-tau ratio for distinguishing ADD from non-ADD in 140 autopsy confirmed AD dementia and 77 autopsy confirmed non-AD dementia patients. The sensitivity was 75,0% and specificity 57,1% with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0,678 (95%CI 0,601-0,755) and an amyloidß42/ t-tau ratio cut-off of 1,08.

4.2 Positive predictive value

Struyfs (2015) did not report on the outcome positive predictive value.

4.3 Negative predictive value

Struyfs (2015) did not report on the outcome negative predictive value.

5. CSF p-tau/Aß ratio

5.1 Specificity and sensitivity

The systematic review and meta-analysis of Ritchie (2017) included five studies with 433 participants to assess the accuracy of CSF p-tau/Aß to detect conversion from MCI to ADD compared to non-ADD. Of the 433 participants, 140 were diagnosed with ADD. Individual study estimates of sensitivity were between 80% and 96% while the specificities were between 33% and 95%. Results are shown in Table 4.

Struyfs (2015) assessed accuracy of CSF amyloidß42/ p-tau ratio for distinguishing ADD from non-ADD in 140 autopsy confirmed AD dementia and 77 autopsy confirmed non-AD dementia patients. The sensitivity was 82,9% and specificity 59,7% with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0,770 (95%CI 0,703-0,837) and an amyloidß42/ p-tau ratio cut-off of 9,11.

5.2 Positive predictive value

Ritchie (2017) did not report on the outcome positive predictive value.

5.3 Negative predictive value

Ritchie (2017) did not report on the outcome negative predictive value.

Table 4. Sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing ADD based on CSF p-tau/Aß (Ritchie, 2017).

|

Systematic review |

Study |

N |

TP |

FP |

FN |

TN |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

|

NA |

Struyfs 2015 |

217 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.829 |

0.597 |

|

Ritchie (2017) |

Hansson 2006 |

134 |

55 |

19 |

2 |

58 |

0.96 (0.88 to 1.00) |

0.75 (0.64 to 0.84) |

|

Koivunen 2008 |

14 |

4 |

6 |

1 |

3 |

0.80 (0.28 to 0.99) |

0.33 (0.07 to 0.70) |

|

|

Monge-Argiles 2011 |

37 |

9 |

9 |

2 |

17 |

0.82 (0.48 to 0.98) |

0.65 (0.44 to 0.83) |

|

|

Parnetti 2012 |

90 |

26 |

3 |

6 |

55 |

0.81 (0.64 to 0.93) |

0.95 (0.86 to 0.99) |

|

|

Visser 2009 |

158 |

28 |

49 |

7 |

74 |

0.80 (0.63 to 0.92) |

0.60 (0.51 to 0.69) |

Abbreviations: NA = Not applicable, NR = Not specified by authors, N= number of participants in study, TN = true negatives, TP = true positives, FN = false negatives, FP = false positives, CI = confidence interval.

6. Neurofilament light

None of the included studies (Ritchie 2014, Ritchie 2017, Kokkinou 2019) reported on the diagnostic accuracy (specificity, sensitivity, positive predictive value or negative predictive value) of neurofilament light.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. Amyloidβ42

The evidence was derived from two systematic reviews (Ritchie 2014, Kokkinou 2019) and one case-control study (Struyfs 2015). The level of evidence for all reported outcome measures started at ‘high quality’.

1.1 Specificity and sensitivity

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure specificity was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations including issues with patient selection, index test and flow/timing (-2 risk of bias) and conflicting results (-1 inconsistency).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure sensitivity was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations including issues with patient selection, index test and flow/timing (-2 risk of bias) and conflicting results (-1 inconsistency).

1.2 Positive predictive value

The level of evidence was not assessed since none of the included studies reported on positive predictive value.

1.3 Negative predictive value

The level of evidence was not assessed since none of the included studies reported on negative predictive value.

2. Total-tau (CSF t-tau)

The evidence was derived from one systematic review (Ritchie 2017) and one case-control study (Struyfs 2015). The level of evidence for all reported outcome measures started at ‘high quality’.

2.1 Specificity and sensitivity

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure specificity was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations including issues with patient selection, index test and flow/timing (-2 risk of bias) and conflicting results (-1 inconsistency).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure sensitivity was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations including issues with patient selection, index test and flow/timing (-2 risk of bias) and conflicting results (-1 inconsistency).

2.2 Positive predictive value

The level of evidence was not assessed since none of the included studies reported on positive predictive value.

2.3 Negative predictive value

The level of evidence was not assessed since none of the included studies reported on negative predictive value.

3. Phosphorylated tau (CSF p-tau)

The evidence was derived from one systematic review (Ritchie 2017) and one case-control study (Struyfs 2015). The level of evidence for all reported outcome measures started at ‘high quality’.

3.1 Specificity and sensitivity

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure specificity was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations including issues with patient selection, index test and flow/timing (-2 risk of bias) and conflicting results (-1 inconsistency).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure sensitivity was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations including issues with patient selection, index test and flow/timing (-2 risk of bias) and conflicting results (-1 inconsistency).

3.2 Positive predictive value

The level of evidence was not assessed since none of the included studies reported on positive predictive value.

3.3 Negative predictive value

The level of evidence was not assessed since none of the included studies reported on negative predictive value.

4. CSF Amyloidβ /t-tau ratio

The level of evidence regarding the diagnostic accuracy of CSF t-tau/Amyloidβ ratio was not assessed since none of the included studies reported on CSF t-tau/Amyloidβ ratio.

The evidence was derived from one case-control study (Struyfs 2015). The level of evidence for all reported outcome measures started at ‘high quality’.

4.1 Specificity and sensitivity

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure specificity was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations including issues or unclear reporting about patient selection, index test and flow/timing (-1 risk of bias) and only one study reporting a point estimate without a confidence interval (-2 imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure sensitivity was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations including issues or unclear reporting about patient selection, index test and flow/timing (-1 risk of bias) and only one study reporting a point estimate without a confidence interval (-2 imprecision).

4.2 Positive predictive value

The level of evidence was not assessed since none of the included studies reported on positive predictive value.

4.3 Negative predictive value

The level of evidence was not assessed since none of the included studies reported on negative predictive value.

5. CSF p-tau/Amyloidβ ratio

The evidence was derived from one systematic review (Ritchie 2017) and one case-control study (Struyfs 2015). The level of evidence for all reported outcome measures started at ‘high quality’.

5.1 Specificity and sensitivity

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure specificity was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations including issues with patient selection, index test and flow/timing (-2 risk of bias) and number of included patients (-1 imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure sensitivity was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations including issues with patient selection, index test and flow/timing (-2 risk of bias) and conflicting results (-1 inconsistency).

5.2 Positive predictive value

The level of evidence was not assessed since none of the included studies reported on positive predictive value.

5.3 Negative predictive value

The level of evidence was not assessed since none of the included studies reported on negative predictive value.

6. Neurofilament light

The level of evidence regarding the diagnostic accuracy of neurofilament light was not assessed since none of the included studies reported on neurofilament light.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the diagnostic value of CSF markers (amyloidβ (1 to 42), ratio of amyloidβ (1 to 42)/ amyloidβ (1 to 40), total-tau, phosphorylated tau181, ratio ptau181/ amyloidβ(1-42), neurofilament light) in patients with cognitive impairment and suspected Alzheimer dementia?

P (Patients) = patients with cognitive impairment and suspected Alzheimer dementia

I (Intervention) = biomarkers in CSF (p-tau181/amyloidβ1-42, totaal-tau, gefosforyleerd tau, ratio ptau/aβ, neurofilament light)

C (Comparison) = no CSF markers (diagnosis based on clinical judgement)

R (Reference) = pathological anatomical (PA) diagnosis or the clinical consensus diagnosis.

O (Outcome measures) = diagnostic value (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value)

T/S (Timing/setting) = Additional investigations to diagnose Alzheimer's disease after completing non-invasive clinical judgment with a suspicion of Alzheimer dementia.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered specificity, sensitivity and positive and negative predictive value as crucial outcome measures for decision making. From a clinical perspective high specificity is more important than high sensitivity. In other words, avoiding false positive diagnoses is more important than avoiding false negative diagnoses, due to the absence of available disease-modifying treatments.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies. The working group deliberately did not define minimal clinically important differences.

Search and select (Methods)

On 19 June 2023, a systematic search was performed in the databases Embase.com and Ovid/Medline for systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the diagnostic value of cerebrospinal fluid markers for Alzheimer's disease. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 574 unique hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic reviews (searched in at least two databases, detailed search strategy with search date, in- and exclusion criteria, exclusion table, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available) or RCTs;

- Full-text English language publication; and

- Studies according to the PICROTS.

Initially, 16 studies were selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 12 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and four studies were included.

Results

Three systematic reviews and one observational study were included in the analysis of the literature. The three systematic reviews included 14 studies (Ritchie, 2014), 15 studies (Ritchie, 2017) and 39 studies (Kokkinou 2021). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Bouwman FH, Schoonenboom NS, Verwey NA, van Elk EJ, Kok A, Blankenstein MA, Scheltens P, van der Flier WM. CSF biomarker levels in early and late onset Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2009 Dec;30(12):1895-901. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.02.007. Epub 2008 Apr 9. PMID: 18403055.

- Bridel C, van Wieringen WN, Zetterberg H, Tijms BM, Teunissen CE; and the NFL Group; Alvarez-Cermeño JC, Andreasson U, Axelsson M, Bäckström DC, Bartos A, Bjerke M, Blennow K, Boxer A, Brundin L, Burman J, Christensen T, Fialová L, Forsgren L, Frederiksen JL, Gisslén M, Gray E, Gunnarsson M, Hall S, Hansson O, Herbert MK, Jakobsson J, Jessen-Krut J, Janelidze S, Johannsson G, Jonsson M, Kappos L, Khademi M, Khalil M, Kuhle J, Landén M, Leinonen V, Logroscino G, Lu CH, Lycke J, Magdalinou NK, Malaspina A, Mattsson N, Meeter LH, Mehta SR, Modvig S, Olsson T, Paterson RW, Pérez-Santiago J, Piehl F, Pijnenburg YAL, Pyykkö OT, Ragnarsson O, Rojas JC, Romme Christensen J, Sandberg L, Scherling CS, Schott JM, Sellebjerg FT, Simone IL, Skillbäck T, Stilund M, Sundström P, Svenningsson A, Tortelli R, Tortorella C, Trentini A, Troiano M, Turner MR, van Swieten JC, Vågberg M, Verbeek MM, Villar LM, Visser PJ, Wallin A, Weiss A, Wikkelsø C, Wild EJ. Diagnostic Value of Cerebrospinal Fluid Neurofilament Light Protein in Neurology: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Sep 1;76(9):1035-1048. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1534. PMID: 31206160; PMCID: PMC6580449.

- Delaby C, Teunissen CE, Blennow K, Alcolea D, Arisi I, Amar EB, Beaume A, Bedel A, Bellomo G, Bigot-Corbel E, Bjerke M, Blanc-Quintin MC, Boada M, Bousiges O, Chapman MD, DeMarco ML, D'Onofrio M, Dumurgier J, Dufour-Rainfray D, Engelborghs S, Esselmann H, Fogli A, Gabelle A, Galloni E, Gondolf C, Grandhomme F, Grau-Rivera O, Hart M, Ikeuchi T, Jeromin A, Kasuga K, Keshavan A, Khalil M, Körtvelyessy P, Kulczynska-Przybik A, Laplanche JL, Lewczuk P, Li QX, Lleó A, Malaplate C, Marquié M, Masters CL, Mroczko B, Nogueira L, Orellana A, Otto M, Oudart JB, Paquet C, Paoletti FP, Parnetti L, Perret-Liaudet A, Peoc'h K, Poesen K, Puig-Pijoan A, Quadrio I, Quillard-Muraine M, Rucheton B, Schraen S, Schott JM, Shaw LM, Suárez-Calvet M, Tsolaki M, Tumani H, Udeh-Momoh CT, Vaudran L, Verbeek MM, Verde F, Vermunt L, Vogelgsang J, Wiltfang J, Zetterberg H, Lehmann S. Clinical reporting following the quantification of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease: An international overview. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 Oct;18(10):1868-1879. doi: 10.1002/alz.12545. Epub 2021 Dec 22. PMID: 34936194; PMCID: PMC9787404.

- Ducharme S, Dols A, Laforce R, Devenney E, Kumfor F, van den Stock J, Dallaire-Théroux C, Seelaar H, Gossink F, Vijverberg E, Huey E, Vandenbulcke M, Masellis M, Trieu C, Onyike C, Caramelli P, de Souza LC, Santillo A, Waldö ML, Landin-Romero R, Piguet O, Kelso W, Eratne D, Velakoulis D, Ikeda M, Perry D, Pressman P, Boeve B, Vandenberghe R, Mendez M, Azuar C, Levy R, Le Ber I, Baez S, Lerner A, Ellajosyula R, Pasquier F, Galimberti D, Scarpini E, van Swieten J, Hornberger M, Rosen H, Hodges J, Diehl-Schmid J, Pijnenburg Y. Recommendations to distinguish behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia from psychiatric disorders. Brain. 2020 Jun 1;143(6):1632-1650. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa018. Erratum in: Brain. 2020 Jul 1;143(7):e62. PMID: 32129844; PMCID: PMC7849953.

- Kokkinou M, Beishon LC, Smailagic N, Noel-Storr AH, Hyde C, Ukoumunne O, Worrall RE, Hayen A, Desai M, Ashok AH, Paul EJ, Georgopoulou A, Casoli T, Quinn TJ, Ritchie CW. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid ABeta42 for the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia in participants diagnosed with any dementia subtype in a specialist care setting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Feb 10;2(2):CD010945. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010945.pub2. PMID: 33566374; PMCID: PMC8078224.

- van Harten AC, Kester MI, Visser PJ, Blankenstein MA, Pijnenburg YA, van der Flier WM, Scheltens P. Tau and p-tau as CSF biomarkers in dementia: a meta-analysis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011 Mar;49(3):353-66. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2011.086. Epub 2011 Feb 23. PMID: 21342021.

- Nichols E, Merrick R, Hay SI, Himali D, Himali JJ, Hunter S, Keage HAD, Latimer CS, Scott MR, Steinmetz JD, Walker JM, Wharton SB, Wiedner CD, Crane PK, Keene CD, Launer LJ, Matthews FE, Schneider J, Seshadri S, White L, Brayne C, Vos T. The prevalence, correlation, and co-occurrence of neuropathology in old age: harmonisation of 12 measures across six community-based autopsy studies of dementia. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023 Mar;4(3):e115-e125. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(23)00019-3. PMID: 36870337; PMCID: PMC9977689.

- NVN, 2018. Richtlijn Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). Beoordeeld: 04-09-2018. Link: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/mild_cognitive_impairment_mci/startpagina_-_mild_cognitive_impairment_mci.html

- Ritchie C, Smailagic N, Noel-Storr AH, Takwoingi Y, Flicker L, Mason SE, McShane R. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Jun 10;2014(6):CD008782. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008782.pub4. PMID: 24913723; PMCID: PMC6465069.

- Ritchie C, Smailagic N, Noel-Storr AH, Ukoumunne O, Ladds EC, Martin S. CSF tau and the CSF tau/ABeta ratio for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Mar 22;3(3):CD010803. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010803.pub2. PMID: 28328043; PMCID: PMC6464349.

- Schoonenboom NS, Reesink FE, Verwey NA, Kester MI, Teunissen CE, van de Ven PM, Pijnenburg YA, Blankenstein MA, Rozemuller AJ, Scheltens P, van der Flier WM. Cerebrospinal fluid markers for differential dementia diagnosis in a large memory clinic cohort. Neurology. 2012 Jan 3;78(1):47-54. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823ed0f0. Epub 2011 Dec 14. PMID: 22170879.

- van Steenoven I, Aarsland D, Weintraub D, Londos E, Blanc F, van der Flier WM, Teunissen CE, Mollenhauer B, Fladby T, Kramberger MG, Bonanni L, Lemstra AW; European DLB consortium. Cerebrospinal Fluid Alzheimer's Disease Biomarkers Across the Spectrum of Lewy Body Diseases: Results from a Large Multicenter Cohort. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016 Aug 18;54(1):287-95. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160322. PMID: 27567832; PMCID: PMC5535729.

- Struyfs H, Niemantsverdriet E, Goossens J, Fransen E, Martin JJ, De Deyn PP, Engelborghs S. Cerebrospinal Fluid P-Tau181P: Biomarker for Improved Differential Dementia Diagnosis. Front Neurol. 2015 Jun 17;6:138. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00138. PMID: 26136723; PMCID: PMC4470274.

- Spies PE, Claassen JA, Peer PG, Blankenstein MA, Teunissen CE, Scheltens P, van der Flier WM, Olde Rikkert MG, Verbeek MM. A prediction model to calculate probability of Alzheimer's disease using cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. Alzheimers Dement. 2013 May;9(3):262-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.010. Epub 2012 Nov 2. PMID: 23123231.

- Spies PE, Verbeek MM, Sjogren MJ, de Leeuw FE, Claassen JA. Alzheimer biomarkers and clinical Alzheimer disease were not associated with increased cerebrovascular disease in a memory clinic population. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2014 Jan;11(1):40-6. doi: 10.2174/1567205010666131120101352. PMID: 24251395.

- Vos SJ, Visser PJ, Verhey F, Aalten P, Knol D, Ramakers I, Scheltens P, Rikkert MG, Verbeek MM, Teunissen CE. Variability of CSF Alzheimer's disease biomarkers: implications for clinical practice. PLoS One. 2014 Jun 24;9(6):e100784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100784. PMID: 24959687; PMCID: PMC4069102.

- Vos SJ, Xiong C, Visser PJ, Jasielec MS, Hassenstab J, Grant EA, Cairns NJ, Morris JC, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM. Preclinical Alzheimer's disease and its outcome: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013 Oct;12(10):957-65. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70194-7. Epub 2013 Sep 4. PMID: 24012374; PMCID: PMC3904678.

- Willemse EAJ, Scheltens P, Teunissen CE, Vijverberg EGB. A neurologist's perspective on serum neurofilament light in the memory clinic: a prospective implementation study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021 May 18;13(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s13195-021-00841-4. PMID: 34006321; PMCID: PMC8132439.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Ritchie, 2014

Study characteristics and results for individual studies are extracted from the SR Ritchie, 2014 (unless stated otherwise) |

SR

Literature search up to December 2012

A: Bjerke 2009 B: Blom 2009 C: Chiasserini 2010 D: Galluzzi 2010 E: Hampel 2004 F: Hansson 2007 G: Hertze 2010 H: Kester 2011 I: Papaliagkas 2009 J: Monge-Argiles 2011 K: Parnetti 2006 L: Shaw 2009 M: Vos 2013 N: Zetterberg 2003

Study design: prospective cohort

Setting and Country: Participants were recruited from i) secondary care – outpatient clinic (n = 12); ii) secondary care – inpatients (n = 2); iii) community care (n = 2) and mixed setting (n = 1).

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR: 1) prospectively well-defined cohorts 2) any accepted definition of MCI but no dementia 3) baseline CSF or plasma Aß levels, or both, documented at or around the time the MCI diagnosis was made 4) reference standard for Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis based on the National Institute for National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke/ Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS- ADRDA) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria 5) sufficient data to construct two by two tables expressing biomarker results by disease status.

Exclusion criteria SR: Studies were excluded if they included patients with possible other causes for dementia: psychiatric, neurological, metabolic, immunological, hormonal or cerebrovascular disorders, genetic cause or early onset ADD (if studies included patients below the age of 50 years, they were excluded).

14 studies included

Important patient characteristics: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question; for example, age, sex, bmi, ...

N, mean age A: 162 patients, 63.8 yrs B: 28 patients, 63.7 yrs C: 41 patients, 66.0 yrs D: 64 patients, 71.6 yrs E: 52 patients, 72.5 yrs F: 134 patients, 70.8 G: 159 patients, 72 years H: 100 patients, 67.8 yrs I: 53 patients, 68.7 yrs J: 37 patients, 73.4 yrs K: 55 patients, age NR L: 196 patients, 75.2 yrs M: 214 patients, 70.7 years N: 53 patients; mean age NR

Sex: A: 68/162 (42.0% male) B: 28/58 (46.4% male) C: 20/41 (48.9% male) D: 37/90 (41.0% male) E: 24/52 (46.2% male) F: 58/131 (32.8% male) G: 65/159 (40.8% male) H: 59/100 (59.0% male) I: 22/53 (41.5% male) J: 13/37 (35.1% male) K: gender NR L: 131/196 (66.8% male) M: 270/625 (43.2% male) N: gender NR |

Describe index and comparator tests* and cut-off point(s):

A: CSF Abeta42; 512 ng/l B: CSF Abeta42; 82 pM C: CSF Abeta42; 741 pg/ml D: CSF Abeta42; 500 pg/ml E: CSF Abeta 1-42; 679 ng/l F-1: CSF Abeta42; 0.64 ng/ml F-2: Abeta42/Abeta40 ratio; 0.95 ng/l G: CSF Abeta42; 209 pg/ml H: CSF Abeta42; 495 pg/ml I: CSF Abeta42; 472 pg/ml J: CSF Abeta42; 320 pg/ml K: CSF Abeta42; 500 pg/l L: CSF Abeta42; 192 pg/ml M: CSF Abeta1-42; 500 pg/ml N: CSF Abeta42; 532 ng/l ..... [use the format ‘character+number’ if 2 or more index tests are being compared, e.g. A-1, A-2, etc] |

Describe reference test and cut-off point(s):

NB: Cut-off NA for all reference tests

A: NINDS-ADRDA and ICD-10 criteria B: NINCDS-ADRDA C: NINCDS-ADRDA D: NINCDS-ADRDA E: NINCDS-ADRDA, DSM-IV criteria F: NINCDS-ADRDA, DSM-III-R G: NINCDS-ADRDA, DSM-II-R criteria H: NINCDS-ADRDA I: the criteria used to define progression to ADD were not clearly defined J: NINCDS-ADRDA K: NINCDS-ADRDA L: NINCDS-ADRDA M: NINCDS-ADRDA, DSM-IV criteria N: DSM-IV

Prevalence (%) [based on reference test at specified cut-off point] A: 20/174 (11.5%) B: 14/28 (50%) C: 23/41 (56.1%) D: 39/90 (43.3%) E: 29/52 (55.8%) F: 57/134 (42.5%) G: 55/166 (33.1%) H: 42/107 (39.3%) I: 5/53 (9.43%) J: 11/37 (29.7%) K: 11/55 (20%) L: 37/196 (18.9%) M: 91/214 (42.5%) N: 22/53 (41.5%)

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%) A: 12/162 (7.41%) B: 30/58 (51.7%) C: 0 (0%) D: 44/64 (68.8%) E: 0 (0%) F: 3/134 (2.24%) G: 7/160 (4.38%) H: 53/100 (53.0%) I: 0 (0%) J: 0 (0%) K: 0 (0%) L: 4/196 (2.04%) M: 17/214 (7.94%) N: 0 (0%)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? A: 8 patients had improved their condition at follow-up, 3 patients converted to a dementia disorder where no etiology could be clinically established, 1 patient converted to primary progressive aphasia B: reasons NR C: NA, because everyone had outcome data D: 16 refused follow-up assessment, 2 did not follow-up due to logistic problems, 24 refused LP, 2 failure to reach the arachnoid space due to osteoarthrosis E: NA, because everyone had outcome data F: 3 participants died before completion of 4 years follow-up and were excluded from the analyses because their cognitive ability was uncertain G: xMAP analysis resulted in technical errors H: 7 MCI participants who converted to other dementias were excluded from the analysis; 46 participants did not have follow-up data; no further information I: NA, because everyone had outcome data J: NA, because everyone had outcome data K: NA, because everyone had outcome data L: reasons NR M: some participants refused to participate or were untraceable or died before follow-up N: NA, because everyone had outcome data

|

Endpoint of follow-up: Outcomes were assessed

A: max 4 years B: mean 3.4 years; max 8.0 years C: max 4 years D: mean 2 years E: mean 0.7 years F: mean 5.2 years; max 6.8 years G: mean 4.7 years; max 7.2 years) H: mean 1.5 years; max 2.0 years I: mean 0.9 years; max 1.8 years J: 0.5 years K: max 1.0 years L: max 1.0 years M: mean 2.5 years (max 5 years) N: mean 1.67 years |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Outcome measure-1/2 for Abeta42 e.g. sensitivity / specificity (%)], mean (95% CI) A: 90 [68, 99]% / 70 [61, 77]% B: 64 [35, 87]% / 36 [13, 65]% C: 74 [52, 90]% / 89 [65, 99]% D: 82 [60, 95]% / 60 [43, 74]% E: 83 [64, 94]% / 57 [34, 77]% F: 93 [83, 98]% / 53 [42, 65]% G: 90 [79, 97]% / 69 [60, 78]% H: 76 [61, 88]% / 72 [59, 83]% I: 100 [48, 100]% / 77 [63, 88%] J: 82[48, 98]% / 62 [41, 80]% K: 36 [11, 69]% / 91 [78, 97]% L: 86 [71, 95]% / 29 [22, 37]% M: 68 [58, 78]% / 67 [58, 75]% N: 68 [45, 86]% / 61 [42, 78]%

Pooled characteristics: Because of the variation in assay thresholds, the authors did not estimate summary sensitivity and specificity. Instead they derived estimates of sensitivity at fixed values of specificity from the hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic (HSROC) model used to produce the ROC curve. At the median specificity of 64%, the sensitivity was 81% (95% CI 72 to 87). This equated to a positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 2.22 (95% CI 2.00 to 2.47) and a negative likelihood ratio (LR–) of 0.31 (95% CI 0.21 to 0.48).

|

Study quality (ROB): method used and results per individual study

Methods used: QUADAS-2 tool Patient selection domain Studies C, F, G, I, and M scored unclear risk of bias, mainly because of poor reporting.

Studies E, H, L scored high risk of bias, mainly because the participants were not consecutively or randomly enrolled.

Index test domain Studies A, B, C, E, F, I, J, and N scored high risk of bias, mainly because the threshold used was not pre-specified and the optimal cut-off level was determined from ROC analyses; therefore, the accuracy of the plasma and CSF Aß biomarkers reported in these studies appeared to be overestimated.

Reference standard domain Studies A, B, C, D, E, F, H, J, I, K, and L scored unclear risk of bias, mainly because of poor reporting

Flow and timing domain Studies B, D, E, H, J, I, K, L, and N scored high risk of bias, because not all patients were accounted for in the analysis or the time interval between the index test and reference standard was not appropriate (duration of follow-up was shorter than one year).

Place of the index test in the clinical pathway: add-on

Choice of cut-off point: The studies defined their own cut-off points. Thus no overall choice was made and this could be a source for heterogeneity.

Author’s conclusion. We conclude that when applied to a population of patients with MCI, CSF Aß levels cannot be recommended as an accurate test for Alzheimer's disease.

Sensitivity analyses: ×Exclusion of one study (Kester 2011) – main results were robust ×Exclusion of 8 studies at high or unclear risk of bias for patient selection domain – main results were robust ×Exclusion of 8 studies at high risk of bias for Index test domain – main results were robust

|

|

Ritchie, 2017

Study characteristics and results for individual studies are extracted from the SR Ritchie, 2017 (unless stated otherwise) |

SR

Literature search up to January 2013

A: Amlien 2013 B: Hampel 2004 C: Hansson 2006 D: Kester 2011 E: Monge-Argiles 2011 F: Palmqvist 2012 G: Vos 2013 H: Fellgiebel 2007 I: Koivunen 2008 J: Visser 2009 K: Parnetti 2012

Study design: prospective cohort

Setting and Country: Participants were recruited from i) secondary care – outpatient clinic (n = 12); ii) secondary care – inpatients (n = 2); iii) community care (n = 2) and mixed setting (n = 1).

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR: 1) prospectively well-defined cohorts, 2) any accepted definition of MCI but no dementia, 3) CSF t-tau or p-tau and CSF tau (t-tau or p-tau)/Aβ ratio documented at or around the time the MCI diagnosis was made, 4) reference standard for Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis based on the NINCDS- ADRDA or DSM-IV criteria, 5) sufficient data to construct two by two tables expressing biomarker results by disease status.

Exclusion criteria SR: We excluded those studies that included people with MCI possibly caused by: i) a current or history of alcohol/drug abuse; ii) central nervous system (CNS) trauma (e.g. subdural haematoma), tumour, or infection; iii) other neurological conditions, e.g. Parkinson’s or Huntington’s diseases.

11 studies included

Important patient characteristics: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question; for example, age, sex, bmi, ...

N, mean age A: 49 patients, MCI with abnormal CSF t-tau level: 64 (range 45 to 76); MC with normal CSF t-tau level: 58.5 (45 to 77) yrs B: 52 patients, mean 72.6 years C: 137 patients MCI-MCI (stable): 67 (50 to 86) yrs; MCI-AD 75 (59 to 85) yrs; MCI-other dementia 76 (54 to 82) yrs D: 153 patients, mean 67 ± 9 yrs 9 ± 7 yrs MCI-AD E: 37 patients, mean 73.43 ± 6.63 years F: 133 patients, MCI-MCI: mean 69.8 (range 55 to 85) yrs; MCI-AD: 75.3 (range 55 to 87) yrs; MCI-other dementias: 71.2 (59 to 83) yrs G: 231 patients, 70.7 ± 7.6 yrs naMCI; 70.7 yrs ± 7.8 aMC H: 16 patients, total sample: mean age 68.6 ± 7.9 yrs; MCI-MCI: 68.8 ± 10.0 yrs; MCI-progressive: 68.5 ± 5.9 yrs (4/8 MCI-AD: 69.5 ± 7.9 yrs) I: 15 patients, mean age 71.1 ± 7.2 yrs J: 168 patients, 70.0 ± 7.7 yrs naMCI; 70.0 ± 7.7 yrs aMCI; 66.0 ± 7.9 yrs SCI K: 90 patients, MCI-MCI: mean 66.35 ± 8.22 yrs; MCI-AD: mean 67.23 ± 9.04 yrs

Sex: A: 20/39 (51.3% male) B: 24/52 (46.2% male) C: 60/133 (45.1% male) D: 59/100 (59% male) E: 13/37 (35.1% male) F: MCI-AD: 16/52 (30.8% male) G: 270/605 (44.6% male) H: 9/16 (56.3% male) I: 9/15 (60% male) J: 88/168 (52.4% male) K: 66/100 (66% male) |

Describe index and comparator tests* and cut-off point(s):

A: CSF t-tau; ≥ 300 ng/L for age younger than 50 years; ≥ 450 ng/L for age 50 to 69 years; ≥ 500 ng/ L for age older than 70 years (Sjogren 2001) B: CSF t-tau; ≥ 479 ng/L C-1: CSF t-tau; > 350 ng/L C-2: CSF p-tau; ≥ 60 ng/L C-3: CSF p-tau/ABeta ratio; ˂ 6.5 ng/L D: CSF t-tau; > 356 pg/mL abnormal level; E-1: CSF t-tau; ≥77.5 pg/mL E-2: CSF p-tau; ≥ 54.5 pg/mL E-3: CSF t-tau/ABeta ratio; 0.18 E-4: CSF p-tau/ABeta ratio; 0.18 F-1: CSF t-tau; > 87 pg/mL F-2: CSF p-tau; >39 pg/mL F-3: CSF t-tau/ABeta ratio; cut-off NR G-1: CSF t-tau; > 450 pg/mL for age less than 70 years; > 500 pg/mL for age older than 70 years G-2: CSF t-tau/ABeta ratio; ABeta1–42/(240 1 [1.183 t-tau]) ˂ 1.0 H: CSF p-tau; ≥ 50 pg/mL I-1: CSF p-tau; ≥ 70 pg/mL I-2: CSF p-tau / ABeta ratio; <6.5 pg/mL J-1: CSF p-tau, used in clinical practice; ≥51 pg/mL J-2: CSF p-tau >90 percentile of controls after correction of age; ≥85pg/mL J-3: CSF p-tau/ABeta ratio; <9.92 (<10th percentile of reference group after correction for age) K: CSF p-tau / ABeta ratio; 1074.0 |

Describe reference test and cut-off point(s):

NB: cut-off points NR

A: The Global Deterioration Scale (Reisberg 1982) in combination with the research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease, International Working group (Dubois 2007) B: NINCDS-ADRDA criteria; DSM-IV criteria C: NINCDS-ADRDA and DSM-III-R for Alzheimer's disease dementia D: NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for Alzheimer's disease dementia E: NINCDS-ADRDA criteria F: NINCDS-ADRDA for AD; G: NINCDS-ADRDA criteria; DSM-IV criteria H: progression to Alzheimer's disease dementia was assumed if CDR reached 1 I: NINCS-ADRDA criteria; DSM-IV criteria J: NINCS-ADRDA criteria; DSM-IV criteria K: not specified. MCI participants were clinically evaluated at least once a year during 4-year follow-up period. However, it was reported that the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria were used at baseline to identify AD diagnostic group.

Prevalence (%) [based on reference test at specified cut-off point] A: 9/39 (23%) B: 29/52 (56%) C: 57/134 (42%) D: 42/100 (42%) E: 11/37 (28%) F: 52/133 (39%) G: 91/214 (42%) H: 4/16 (25%) I: 5/14 (36%) J: 35/158 (22%) K: 32/90 (35%)

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%) A: 17/39 (43.6)% B: 0 (0%) C: 43/180 (23.9%) D: 7/107 (6.54%) E: 0 (0%) F: 0 (0%) G: 17/231 (7.36%) H: 1/16 (..) I:1/15 (6.67%) J: 10/168 (5.95%) K: 0 (0%)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? A: 4 participants with MCI objected to re-examination, 1 died of unrelated causes, and 5 were excluded because of definite other diagnoses. 7 control subjects objected to re-examination. B: NA, because everyone had outcome data C: initially identified 180 consecutive participants with MCI; 43/180 not included in the study: 32 refused lumbar puncture and 11 non-usable CSF samples; 3 participants died before 4 years of follow-up (not included in the analysis) D: 7 MCI participants who converted to other forms of dementia were excluded from the analysis. E: NA, because everyone had outcome data F: NA, because everyone had outcome data G: some refused to participate or were untraceable or died before follow-up H: that participant was replaced by an additional, consecutively recruited patient from the memory clinic I:reasons for loss-to-follow-up NR J: CSF follow-up data were not available; the reason not given K: NA, because everyone had outcome data

|

Endpoint of follow-up: A: mean 2.6 ± 0.5 years (range 1.6 to 4 years) B: mean 0.7 ± 0.43 years (range 0.17 to 2 years) C: median 5.2 years (range 4.0 to 6.8 years) D: median 1.5 years (IQR 1.08 – 2 years) E: 0.5 years F: mean 5.9 years (range 3.2 to 8.8 years) G: mean 2.5 ± 1.0 years H: mean 1.63 ± 0.75 years I: 2 years J: range 1 to 3 years for MCI K: maximum: 4 years mean 3.40 ± 1.01 years |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Outcome measure-1/2 [e.g. sensitivity / specificity (%)] A: CSF t-tau: 56 [21, 86]% / 87 [69, 96]% B: CSF t-tau: 90 [73, 98]% / 48 [27, 69]% C-1: CSF t-tau: 51 [37, 64]% / 88 [79, 95]% C-2: CSF p-tau: 68 [55, 80]% / 86 [76, 93]% C-3: CSF p-tau/ABeta ratio: 96 [88, 100]% / 75 [64, 84]% D: CSF t-tau: 83 [69, 93]% / 50 [37, 63]% E-1: CSF t-tau: 73 [39, 94]% / 69 [48, 86]% E-2: CSF p-tau: 82 [48, 98]% / 58 [37, 77]% E-3: CSF p-tau/ABeta ratio: 82 [48, 98]% / 65 [44, 83]% F-1: CSF t-tau: 81 [67, 90]% / 72 [60, 81]% F-2: CSF p-tau: 67 [53, 80]% / 86 [77, 93]% G: CSF t-tau: 71 [61, 80]% / 77 [69, 84]% H: CSF p-tau: 100 [40, 100]% / 33 [10, 65]% I-1: CSF p-tau: 40 [5, 85]% / 22 [3, 60]% I-2: CSF p-tau/ABeta ratio: 80 [28, 99]% / 33 [7, 70]% J-1: CSF p-tau: 89 [73, 97]% / 37 [29, 47]% J-2: CSF p-tau/ABeta ratio: 80 [63, 92]% / 60 [51, 69]% K: CSF p-tau/ABeta ratio: 81 [64, 93]% / 95 [86, 99]%

Pooled characteristics: The authors did not meta-analyse pairs of sensitivity and specificity using the bivariate model, because the results were not clinically interpretable due to the mixed thresholds used by studies. Instead, the authors fitted an HSROC meta-analysis models to estimate summary ROC curves and derived estimates of sensitivity and likelihood ratios at a fixed value of specificity (chosen a priori as the median specificity for the studies that were analysed when fitting the model).

Index test-1 CSF t-tau for diagnosing ADD 77 [95% CI 67 to 85] (sens, with fixed value of spec of 72)

Index test-2 CSF p-tau for diagnosing ADD 81 [64 to 91.5] (sens, with fixed value of spec of 47.5)

Index test-3 CSF p-tau/Abeta ratio for diagnosing ADD no meta-analysis because the studies were few and small.

|

Study quality (ROB): method used and results per individual study

Methods used: QUADAS-2 tool

Patient selection domain Studies B, D, and I scored high risk of bias because the participants were not consecutively or randomly enrolled or both the sampling procedure and exclusion criteria were not described. We stated that all included studies avoided a case-control design because we only considered data on performance of the index test to discriminate between people with MCI who converted to dementia and those who remained stable.

Studies H, E, F, K, J, and G scored unclear risk of bias, due to poor reporting on sampling procedure or exclusion criteria.

Index test domain Studies H, C, E, F, and K scored high risk of bias, due to poor reporting because the threshold used was not prespecified and the optimal cutoff level was determined from ROC analyses; therefore, the accuracy of the CSF biomarkers reported in these studies appeared to be overestimated.

Study A scored unclear risk of bias, due to poor reporting.

Reference standard domain Studies A, H, B, D, I, E, and K scored unclear risk of bias, mainly because it was not reported whether clinicians conducting follow-up were aware of initial CSF biomarker analysis results. Some studies did not clearly report the reference standards used for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease dementia. We were not able to obtain the information about how the reference standard was obtained and by whom, due to poor reporting.

Flow and timing domain Studies A, H, I, E, K, J, and G scored unclear risk of bias, because not all participants were included in the analysis and/or the follow-up period was shorter than one year and/or reporting was poor.

Studies C and D scored high risk of bias because a large number of participants with non-Alzheimer's disease dementia were excluded from the analysis.

Place of the index test in the clinical pathway: add-on

Choice of cut-off point: The studies defined their own cut-off points. Thus no overall choice was made and this could be a source for heterogeneity.

Author’s conclusion. Given the insufficient evidence to evaluate the diagnostic value in MCI of CSF t-tau, CSF p-tau, CSF t-tau/ABeta ratio and CSF p-tau/ABeta ratio for Alzheimer's disease dementia and other forms of dementias examined in this review, particular attention should be paid to the risk of misdiagnosis and overdiagnosis of dementia (and therefore overtreatment) in clinical practice.

Sensitivity analyses: not performed, due to the limited number of studies.

Heterogeneity: Due to insufficient studies, meta-regression was not performed. So, sources of heterogeneity could not be examined.

|

|

Kokkinou, 2021

Study characteristics and results for individual studies are extracted from the SR Kokkinou, 2021 (unless stated otherwise) |

SR

Literature search up to February 2020

A: Brettschneider 2006 B: Kapaki 2003 C: Knapskog 2018 D: Lewczuk 2004 E: Lombardi 2018 F: Maddalena 2003 G: Montine 2001 H: Perani 2016 I: Smach 2008 J: Rosler 2001 K: Spies 2010 L: Tapiola 2000 M: Tariciotti 2018

Study design: cross-sectional case-control (ADD vs non-ADD dementia)

Setting and Country: Participants were recruited from i) secondary care – outpatient clinic (n = 12); ii) secondary care – inpatients (n = 2); iii) community care (n = 2) and mixed setting (n = 1).

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: No known conflicts of interest. The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, National Health Service or the Department of Health

|

Inclusion criteria SR: Cross-sectional studies that differentiated people with ADD from other dementia subtypes. Eligible studies required measurement of participant plasma or CSF ABeta42 levels and clinical assessment for dementia subtype. Delayed verification studies

Exclusion criteria SR: NR

13 studies included

Important patient characteristics: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question; for example, age, sex, bmi, ...

N, mean age A: 109 AD patients, 71 (43-88) years for AD B: 49 AD patients, 67.6 ± 9.3 years for AD C: 205 patients, 84.8 ± 8.8 years for the total sample D: 22 AD patients, 68 (62–77) years for AD E: 32 AD patients, 66.5 ± 9.9 years for ADD; F: 81 patients (n=51 AD), 70.1±8.7 years for AD G: 19 AD patients, 65.3±8.7 years for AD H: 47 AD patients, 66±6.8 years for AD I: 73 AD patients, 73 (48–85) years for AD J: 27 probable AD patients, mean age NR K: 69 AD patients, 69±8 years for AD L: 80 probable AD, 71±8 years for probable AD M: 264 AD patients, 67.7 ± 10.4 years for ADD ….

Sex: A: 39/109 AD (35.8% male) B: 31/49 AD (63.3% male) C: 53.7% male (total sample) D: 6/22 AD (27.3% male) E: 19/32 AD (59.4% male) F: 54/100 (54% male) G: NR H: 26/47 AD (55.3% male) I: 49/73 (67.1% male) J: 9/27 probable AD (33.3% male) K: 34/69 AD (49.3% male) L: 34/80 probable AD (42.5% male) M: 106/264 AD (40.2% male) |

Describe index and comparator tests* and cut-off point(s):

A: ABeta42; 612 pg/ml B: ABeta42; 435 pg/ml C: ABeta42; 550 pg/ml D: ABeta42; 500 pg/ml E: ABeta42; 650 pg/ml F: ABeta42; 490 pg/ml G: ABeta42; 1125 pg/ml H: ABeta42; 500 pg/ml I: ABeta42; 505 pg/ml J: ABeta42; 375 pg/ml K: NR L: ABeta42; 340 pg/ml M: ABeta42; 500 pg/ml

[use the format ‘character+number’ if 2 or more index tests are being compared, e.g. A-1, A-2, etc] |

Describe reference test and cut-off point(s):

A: NINCDS-ADRDA criteria B: NINCDS-ADRDA criteria C: no diagnostic criteria specified; by consensus between two experienced physicians. D: NINCDS-ADRDA criteria E: NIA-AA criteria F: NINCDS-ADRDA G: NINCDS-ADRDA H: NINCDS-ADRDA I: NINCDS-ADRDA J: NINCDS-ADRDA K: NINCDS-ADRDA L: NINCDS-ADRDA M: NINCDS-ADRDA

Prevalence (%) [based on reference test at specified cut-off point] A: 109/165 (66.1%) B: 49/70 (70%) C: 138/205 (67.3%) D: 22/33 (66.7%) E: 32/45 (71.1%) F: 51/81 (63%) G: 19/27 (70.3%) H: 47/75 (62.7%) I: 73/108 (67.6%) J: 27/51 (52.9%) K: 69/138 (50%) L: 80/107 (74.8%) M: 264/1137 (23.2%)

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%) A: NR B: NR C: there is missing data, but for how many patients is NR D: NR E: 0 (0%) F: NR G: NR H: NR I: 20/73 (27.4%) J: NR K: NR L: NR M: 121 (10.7%).

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? A: NR B: NR C: reasons of missing data NR D: NR E: NA, because everyone had outcome data F: NR G: NR H: NR I: no adequate CSF samples obtained J: NR K: NR L: NR

|

Endpoint of follow-up:

This is NA for all individual studies, because only cross-sectional studies were included in this SR.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):