Follow-up VTE

Uitgangsvraag

Hoe dienen patiënten met een VTE opgevolgd te worden?

Aanbeveling

Standaardiseer de follow-up van veneuze trombo-embolie om een goed en volledig beeld te krijgen van de aanwezigheid van de in deze module beschreven relevante complicaties van veneuze trombo-embolie die de kwaliteit van leven negatief beïnvloeden: Posttrombotisch syndroom (PTS, na DVT), CTEPH/CTEPD zonder PH (na longembolie) en psychosociale complicaties.

- Een goede timing hiervoor is rond het drie maanden follow-up moment.

- Geef ten minimale aandacht aan functionele beperkingen, benauwdheid en psychosociale impact, en - bij patiënten met een diep veneuze trombose – het post trombotisch syndroom.

- Maak hiervoor bij voorkeur gebruik van PROMS en de Villalta score: daarmee worden deze symptomen reproduceerbaar en zo objectief mogelijk vastgelegd, en kan beloop ervan door de tijd en de effecten van behandeling goed worden gemonitord.

Patiënten met PTS

Behandel patiënten met aangetoonde PTS initieel met compressietherapie en bewegingstherapie.

Patiënten die aanhoudend benauwd zijn of inspanningsbeperking hebben

Voer aanvullende diagnostiek uit om chronische trombo-embolische pulmonale hypertensie/ziekte (CTEPH/CTEPD zonder PH) uit te sluiten en volg hierbij de volgende stappen, namelijk:

1. Verricht eerst een ECG en (NT-pro) BNP-bloedtest (en indien afwijkend, een echocardiografie) of primair een echocardiografie;

2. Indien er geen aanwijzingen zijn voor pulmonale hypertensie en er geen evidente andere verklaring is voor de klachten: voer een cardiopulmonale inspanningstest (CPET) uit.

3. Indien er aanwijzingen zijn voor CTEPH/CTEPD zonder PH bij echocardiografie of CPET of anderszins: beeldvorming van de pulmonale vaatboom/perfusie is geïndiceerd:

- Verwijs patiënten met CTEPH/CTEPD zonder PH door naar een expertisecentrum.

- Indien er geen sprake is van CTEPH/CTEPD zonder PH: overweeg om cardiopulmonale revalidatie in te zetten.

Patiënten met een vastgestelde relevante angststoornis of depressie

- Zet een adequate behandeling in, bij voorkeur via de eerste lijn.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Voor deze module is er gekeken naar de impact van verschillende lange termijn complicaties van veneuze trombo-embolie (VTE) op kwaliteit van leven. De gegevens hierover zijn verzameld in observationeel onderzoek, voornamelijk uitgevoerd in Nederland, Canada en Scandinavië. Uit de narratieve review van in totaal tien studies (uit een selectie van de 106 studies uit de ICHOM-analyse (Gwodz, 2022), see Evidence Tables, Table ICHOM-studies that reported on the outcome quality of life) die keken naar chronische aandoeningen die kunnen ontstaan na een VTE, bleek dat het merendeel van deze aandoeningen consistent geassocieerd is met mindere kwaliteit van leven. De studies gaven niet genoeg informatie om te toetsen of dit verschil ook klinisch relevant is (Tabel 5).

In de uiteindelijke aanbeveling worden de gegevens uit de literatuuranalyse in een context geplaatst die aansluit op de dagelijkse praktijk. Het is ondoenlijk om voor alle mogelijke aanhoudende symptomen een aparte PICO te schrijven en tot een evidence based advies te komen over de te volgen strategie. Daarom is gekozen gebruik te maken van (inter)nationale consensus en recente internationale richtlijnen over het te voeren beleid (Delcroix, 2021; Humbert, 2022; Klok, 2022; Konstantinides, 2022).

Algemene opmerking over subgroepen

Deze module is geschreven zonder rekening te houden met specifieke subgroepen, zoals de oudere en/of kwetsbare patiënt of de patiënt met levensbeperkende comorbiditeit. Bewijs voor de beste aanpak in deze en andere subgroepen ontbreekt. Derhalve moeten de omstandigheden van de individuele patiënt en de proportionaliteit van het inzetten van aanvullend onderzoek of behandelingen altijd worden meegewogen.

Post trombotisch syndroom (PTS)

Ongeveer 10 tot 50% van de patiënten die een DVT heeft doorgemaakt zal een PTS ontwikkelen (ten Cate-Hoek, 2018). Hierbij is de incidentie één jaar na DVT ongeveer 10% en dit neemt toe tot 50% in de periode van vijf tot acht jaar na DVT. De incidentie van ernstige PTS (veneus ulcus) is 1-2%. Het klinisch beeld van PTS is variabel. Patiënten kunnen pijn, een zwaar gevoel, zwelling, kramp, paresthesiën en of jeuk ervaren. De symptomen kunnen continu of intermitterend zijn en verbeteren in rust en bij omhoog leggen van het been. Ook kan er sprake zijn van veneuze claudicatio. De patiënt ervaart dit typisch bij sneller lopen, traplopen of bergop lopen. De diagnose PTS wordt gesteld met behulp van de Villalta score, die tenminste zes maanden na de oorspronkelijke diagnose vijf punten of meer moet zijn. Een deel van de score betreft zelf-gerapporteerde symptomen. Het is aan te bevelen in ieder geval na een periode van drie maanden de Villalta-score samen met patiënt te berekenen. De initiële behandeling van PTS bestaat uit compressietherapie en bewegingsadviezen. Zie verder ook de richtlijn van de European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Patiënten met een hoge ziektelast die veel beperkingen ervaren kunnen worden verwezen naar een expertisecentrum.

CTEPD/CTEPH en aanhoudende klachten van benauwdheid

Voor CTEPH/CTEPD zonder pulmonale hypertensie (PH) kon de prevalentie niet uit de besproken studies gehaald worden, maar een recente publicatie heeft aangetoond dat de prevalentie van CTEPH 2-3% is, net als dat van CTEPD zonder PH (Held, 2023; Luijten, 2023). CTEPH en CTEPD zonder PH worden gedefinieerd als de aanwezigheid van reststolsels in de pulmonaal arteriën ondanks ten minste drie maanden antistolling (met morfologie van een chronisch stolsel, zoals een zogenaamd webje) met perfusie defecten en pulmonale hypertensie (CTEPH), ofwel gepaard gaande met symptomen van benauwdheid of inspanningsbeperking én meetbare fysiologische afwijkingen zoals dode-ruimte ventilatie of pulmonale hypertensie bij inspanning (CTEPD zonder PH) (Humbert, 2022). Het is aangetoond dat een vroege diagnose van CTEPH (binnen maanden na de longembolie) resulteert in snellere behandeling en een betere overleving (Klok, 2017). Het blijkt echter dat door gebrek aan gestandaardiseerde follow-up van patiënten met een longembolie en een gebrek aan gedetailleerde kennis van dit ziektebeeld bij behandelaren de diagnostische vertraging in Nederland gemiddeld twee jaar is (Ende-verhaar, 2018). Verschillende studies laten zien dat het implementeren van een algoritme gericht op CTEPH inderdaad resulteert in een duidelijke verkorting van de diagnostische vertraging (Boon, 2021; Valerio, 2022). Zo’n algoritme begint met het op een gestandaardiseerde manier vaststellen van aanhoudende klachten, bijvoorbeeld met een PROM (Konstantinides, 2020, Klok, 2022). Een goed voorbeelden daarvan is de modified Medical Research Council Dyspnoe vragenlijst (mMRC). Patiënten met klachten verdienen aanvullend onderzoek. Het onderzoek van keuze bij verdenking op pulmonale hypertensie is een echocardiografie. Het is gebleken dat een normale ECG en (NT-pro) BNP-bloedtest de aanwezigheid van pulmonale hypertensie zeer onwaarschijnlijk maakt (Boon, 2021; Humbert, 2022). Met deze tussenstap kan het aantal verwijzingen voor een echocardiografie beperkt worden. Bij aanhoudende benauwdheid maar geen pulmonale hypertensie is een CPET de diagnostische test van keus. Hiermee kan onderscheid gemaakt worden tussen verschillende oorzaken van benauwdheid, en tevens aanwijzingen voor CTEPD zonder PH worden gevonden, bijvoorbeeld als er sprake is van dode ruimte ventilatie. Zowel patiënten met echografische verdenking op pulmonale hypertensie als verdenking op CTEPD zonder PH op basis van de CPET hebben een indicatie voor nieuwe beeldvorming van de pulmonaal vaten en perfusie (Humbert, 2022; Konstantinides, 2020). Dat kan met een CT-scan of nucleaire scan. Indien op basis van deze beeldvorming de verdenking op CTEPH of CTEPD zonder PH blijft bestaan, horen patiënten doorverwezen te worden naar een CTEPH-expertisecentrum. Adequate behandeling resulteert gemiddeld in een sterke verbetering van de kwaliteit van leven.

Patiënten met aanhoudende benauwdheid en/of inspanningsbeperking waarbij CTEPH/CTEPD zonder PH is uitgesloten, hebben baat bij hart/long revalidatie (Boon/Janssen, 2021; Klok, 2022 and Jervan, 2023): de ervaringen beperkingen in het dagelijks leven nemen gemiddeld af en de kwaliteit van leven neemt toe.

Psychosociale complicaties

Erickson (2019) en Keller (2019) definieerden psychosociale complicaties als angst en depressie, en concluderen dat deze toestand kan leiden tot een relevante daling van de kwaliteit van leven. Ook voor angst en depressie bestaan bruikbare en gevalideerde PROMs. Een voorbeeld hiervan is de Vierdimensionale Klachtenlijst (4DKL). De 4DKL is een vragenlijst bestaande uit 50 items, gericht op psychosociale klachten. De lijst is ontwikkeld in de huisartsenpraktijk en maakt onderscheid tussen aspecifieke 'distress'-klachten, depressie, angst, en somatisatie. Deze vier symptoomdimensies vormen tevens de vier verschillende categorieën. De antwoordmogelijkheden van de lijst zijn ordinaal opgebouwd en hoe hoger een patiënt scoort op de vragenlijst, des te meer psychosociale klachten ondervindt hij in zijn dagelijkse handelingen. Met de 4DKL kunnen problemen in de genoemde dimensies worden opgespoord en het geeft handvatten voor de noodzaak tot nadere diagnostiek. Een alternatieve PROM is de “Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale” HADS. De HADS meet kernklachten van angst en depressie zonder daarbij lichamelijke klachten te betrekken. Het is een korte vragenlijst, die gemakkelijk te gebruiken is. De schaal gaat in op gevoelens in de afgelopen vier weken en bestaat uit een angstschaal en een depressieschaal met beide zeven items. Hoe hoger een patiënt scoort op deze vragenlijst des te meer klachten hij/zij ervaart.

Internationale consensus

De 2019 ESC/ERS longembolie richtlijn suggereert gebruik te maken van PROMS om te bepalen bij welke patiënten aanvullend onderzoek naar CTEPH geïndiceerd is (Konstantinides, 2020). Het in 2022 gepubliceerde ESC/ERS consensus document over follow-up na acute longembolie is wat specifieker op dit onderwerp en adviseert naast een PROM voor dyspnoe ook een PROM voor het vaststellen van functionele beperkingen voor. Dit helpt bij het inschatten van de ernst van aanhoudende symptomen maar ook om de potentiële impact van een behandeling in te schatten. De Post-VTE Functionele Status (PVFS) schaal richt zich op relevante aspecten van het dagelijks leven in de eerste periode na een VTE-diagnose (Boon, 2020). Het is bedoeld om de zorgmedewerker en patiënt bewust te maken van goed of minder goed herstel van VTE en de gevolgen daarvan op het functioneren van de patiënt. Minder goed herstel kan wijzen op lange termijn complicaties die behandeling behoeven. De PVFS-schaal is ordinaal en heeft zes klassen die variëren van nul (geen symptomen) tot vijf (dood, D). De schaal bestrijkt het gehele spectrum aan functionele uitkomsten door zich te richten op zowel beperkingen in gebruikelijke taken/activiteiten in de thuissituatie, op het werk of de studie, als op veranderingen in levensstijl. De klassen van de PVFS-schaal zijn intuïtief en kunnen gemakkelijk worden beoordeeld en vervolgens worden geïnterpreteerd door artsen en patiënten.

Een internationale werkgroep van zorgmedewerkers en patiënten heeft zich gericht op het vaststellen van de kernuitkomsten van veneuze trombo-embolie die voor alle patiënten relevant zijn: ICHOM-VTE (Gwodz, 2022). Nadat de kernuitkomsten waren vastgesteld, werd er voor elke uitkomst een instrument bepaald, met als belangrijkste kenmerk dat deze zo mogelijk patiënt-gerapporteerd, gevalideerd, makkelijk (en gratis) in veel talen beschikbaar en toegankelijk is. In deze uitkomst set zitten PROMS voor kwaliteit van leven, pijn, benauwdheid, angst, depressie, functionele beperkingen, patiënttevredenheid en verandering van levensvisie. Om het aantal in te vullen vragen te beperken heeft de set enkele cascade opties ingebouwd.

De internationale vereniging voor trombose en hemostase (ISTH) heeft in recente publicaties de relevantie van het gebruik van PROMS bevestigd, en onderschrijft de relevantie van de ICHOM set (de Jong, 2023).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

In deze module staat de kwaliteit van leven van de patiënt centraal. De ICHOM-set die wordt besproken, is ontwikkeld met en voor patiënten. Hierbij was ook een Nederlandse patiëntpartner betrokken. In de follow-up is het voor patiënten belangrijk dat er goede informatie gegeven wordt over de aandoening en ook (de inhoud van) het nazorgtraject. Ook dient duidelijk te zijn wie het aanspreekpunt is bij eventuele vragen vanuit de patiënt.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er is nauwelijks tot geen onderzoek voor handen naar de kosteneffectiviteit van (PROMS gestuurde) symptoomgerichte follow-up na VTE. Wel is er een Nederlandse analyse die aantoont dat eerdere diagnose van CTEPH na longembolie kosteneffectief is (Boon/ Van den Hout, 2021). Het is mogelijk dat gestandaardiseerde nazorg van veneuze trombo-embolie overdiagnostiek voorkomt, en leidt tot gerichte verwijzingen. Het gebruik van PROMS is kosteloos, al moet er wel worden geïnvesteerd in patiënten motivatie/instructie en een (liefst digitale) manier om de PROMS-uitkomsten te verwerken en op te slaan. Een gestandaardiseerde en gestructureerde nazorg van VTE-patiënten is mogelijk doelmatig en voorkomt onnodige zorg (Ende-Verhaar, 2018).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het implementeren van PROMS kan lastig zijn. Niet alleen moeten de juiste PROMS worden gekozen, ook moeten er juiste instructie aan patiënten én zorgmedewerkers komen, en is een infrastructuur voor de invullen, opslaan en verwerken van de PROM-resultaten noodzakelijk. Het bespreken van PROM-uitslagen kost tijd, al kan het ook versnellend werken omdat een deel van de anamnese reeds ondervangen is. Er is een PROM-toolbox samengesteld door het Zorginstituut die houvast kan geven. De PROM-toolbox bestaat uit de PROM-wijzer en de PROM-cyclus. De PROM-wijzer gaat over de oriëntatie en voorbereiding op het gebruik van PROMs. De PROM-cyclus gaat over de selectie en toepassing van PROMs.

Rationale van de aanbeveling

Om richting te geven aan de optimale nazorg van patiënten met een VTE heeft de werkgroep vastgesteld welke complicaties de kwaliteit van leven na een VTE negatief beïnvloeden, namelijk PTS, CTEPH/CTEPD zonder PH en psychosociale complicaties. De werkgroep acht het van belang dat er in de nazorg voor de patiënten met een VTE aandacht wordt gegeven aan tenminste deze complicaties, bijvoorbeeld tijdens het drie maanden follow-up moment. Op basis van beschikbare literatuur en bestaande (recente) internationale richtlijnen zijn er aanbevelingen opgesteld hoe deze complicaties opgespoord kunnen worden en wat mogelijke vervolgstappen zijn.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In the follow-up of patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE), most attention is paid to prevent recurrent disease and bleeding, and there is an important focus on the decision to stop or continue anticoagulation after 3 months. Recurrent disease and bleeding are indeed associated with mortality and morbidity, and lead to a decrease in quality of life. However, other disease-related complications also have an impact on the patient's recovery and the possibility of resuming life after diagnosis. Up to half of patients with VTE appear to have residual symptoms that hinder functional recovery months after diagnosis and adequate anticoagulation treatment, having post-thrombotic syndrome or post-pulmonary embolism syndrome. Since from the patient's perspective, functional recovery is an important if not the most important outcome of treatment of VTE, the follow-up pathway should be designed to detect and treat all relevant complications. However, studies on optimal follow-up of VTE are limited, and randomized studies are completely lacking. For this reason, there is great variation in the design of follow-up pathways for VTE, both within and between primary and secondary care. Diagnostic pathways to detect complications are limited in their focus and insufficient. In order to provide direction for optimal follow-up of VTE, this module focus on which complications have been proven to have a negative impact on quality of life. For all these complications, a proposal is then made for the best way to detect them, based on available literature and existing international recommendations.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Post thrombotic syndrome (PTS)

|

No GRADE |

PTS may result in a relevant decrease in quality of life as compared to VTE patients without PTS.

Sources: Kahn, 2008; Haig, 2016 and Ljungqvist, 2018 |

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease (CTEPD) without PH/chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH)

|

No GRADE |

CTEPD without PH or CTEPH may result in a relevant decrease in quality of life as compared to VTE patients without CTEPD without PH or CTEPH.

Sources: Roman, 2013 and Taboada, 2014 |

Residual complaints

|

No GRADE |

Residual complaints may result in a relevant decrease in quality of life as compared to VTE patients without residual complaints.

Sources: Kahn, 2017; Keller, 2019; Tavoli, 2018 and Valerio, 2022 |

Psychosocial unwellness

|

No GRADE |

Psychosocial unwellness may result in a relevant decrease in quality of life as compared to VTE patients without psychosocial unwellness, but the evidence is uncertain.

Sources: Erickson, 2019 and Keller, 2019 |

Samenvatting literatuur

The ICHOM-search query with accompanying PICO was drawn up more broadly than the PICO as defined by the working group. The ‘ICHOM-PICO’ included other outcomes in addition to the outcome quality of life. In total, 106 studies reported on the outcome quality of life (see Evidence Tables, Table ICHOM-studies that reported on the outcome quality of life). Since all those studies were considered to fit (at least part of) the PICO, and while there were no resources to systematically review all these studies in this guideline module, it was decided by the working group to select the studies that were deemed most relevant for this module.

In addition one study (i.e., the first study, published in 2008) that reported on quality of life in patients with PTS was not captured by the ICHOM search strategy (search date 2011-2021). Another large study published in 2022 that included a large number of patients with residual complaints after pulmonary embolism (also not captured by ICHOM as the search date of ICHOM was between 2011-2021) were included.

Please note that the methodology that is followed here is a narrative review which cannot be used in the systematic process of rating the quality of the best available evidence as proposed by the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group.

Results

A total of 185 studies were initially selected based on the ICHOM search query. Of these 185 studies, n=106 studies were included as they reported on the outcome quality of life. Of these, the working group selected eight studies that were deemed most relevant for this module (Erickson, 2019; Haig, 2016; Kahn, 2017; Keller, 2019; Ljungqvist, 2018; Roman, 2013; Tabaoda, 2014; Tavoly, 2018). In addition one study (i.e., the first study, published in 2008, (Kahn, 2008) that reported on quality of life in patients with PTS which was not captured by the ICHOM search strategy (search date 2011-2021) and another large study published in 2022 that included a large amount of patients with residual complaints after pulmonary embolism (also not captured by ICHOM as the search date of ICHOM was between 2011-2021, (Valerio, 2022) were included.

The study characteristics are summarized in Table 1 below. Main results are fully shown in the forest plots. Risk of bias assessments are fully shown in the risk of bias table.

Tabel 1: Studies included in narrative review

|

|

Exposure category, VTE with or without: |

||||||

|

Study |

Included in ICHOM |

Study size, n |

Condition |

Psychosocial unwellness |

Residual complaints |

PTS |

CTEPD without PH |

|

Kahn, 2008 |

No |

387 |

DVT |

|

|

X |

|

|

Haig, 2016 |

Yes |

209 |

DVT |

|

|

X |

|

|

Ljungqvist, 2018 |

Yes |

1040 |

VTE |

|

|

x |

|

|

Kahn, 2017 |

Yes |

100 |

PE |

|

X |

|

|

|

Keller, 2019 |

Yes |

101 |

PE |

|

X |

|

|

|

Tavoly, 2018 |

Yes |

203 |

PE |

|

X |

|

|

|

Valerio, 2022 |

Yes |

1017 |

PE |

|

x |

|

|

|

Roman, 2013 |

Yes |

156 |

VTE |

|

|

|

X |

|

Taboada, 2014 |

Yes |

42 |

VTE |

|

|

|

X |

|

Erickson, 2019 |

Yes |

907 |

VTE |

X |

|

|

|

|

Keller, 2019 |

Yes |

101 |

PE |

X |

|

|

|

CTEPD: chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; PE: pulmonary embolism; PH: pulmonary hypertension; PTS: postthrombotic syndrome; VTE: venous thromboembolism

Exposure category PTS

Definitions exposure category

Kahn (2008) and Haig (2016) defined PTS by using the Villalta scale (higher scores indicate more severe PTS). A Villalta score of <5 was considered to represent no PTS.

Ljungqvist (2018) defined PTS by modified Villalta score with a kappa of 0.88 with the original Villalta score. A modified Villalta score of <5 was considered to represent no PTS.

Definitions outcome

Kahn (2008) defined quality of life (QOL) by using the Short-Form Health Survey-36 (SF-36PCS/MCS) and the VEINESQOL/Sym. Clinical relevance was non-defined.

Haig (2016) defined QOL by using the EQ-5D and the VEINES-QOL/Sym questionnaire. A mean difference in EQ-5D of 0·08 or more was defined as a clinically relevant difference. A mean difference in VEINES-QOL/Sym of four points or more was defined as a clinically relevant difference.

Ljungqvist (2018) defined QOL by SF-36PCS/MCS and the VEINESQOL/Sym. Clinical relevance was non-defined.

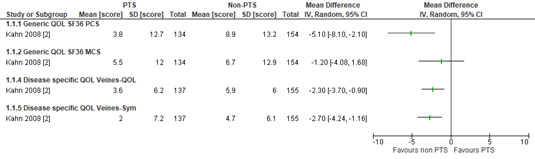

Kahn (2008) prospectively measured change in QOL during the two years after a diagnosis of acute DVT at eight hospitals in Canada. Among the 387 patients recruited, the average age was 56 years. The cumulative incidence of PTS was 47% at two years of follow-up. Patients who developed PTS had lower QOL scores for all questionnaires that were used (Figure 1). Since authors did not define a clinical relevant difference, we used the default threshold (> 0.5 SD). By using this threshold, none of the differences reached clinical relevance. The risk of bias was considered as ‘some concerns’ as it was unclear if excluded participants biased the results and if there was loss to follow-up.

Figure 1. Scores for Quality of life in patients with and without post thrombotic syndrome (PTS, Kahn (2008)

‘Mean’ depicted in the forest plot=’mean change’. PTS: post thrombotic syndrome

Haig (2016) included patients who participated in an open-label clinical trial that was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of catheter-directed thrombolysis. Patients were aged 18–75 years with acute DVT located higher than the proximal half of the femoral vein. QOL results of intervention and comparator group were pooled after which prognosis of QOL was compared in patients with PTS vs non-PTS at 5 years of follow-up. Of 209 enrolled patients, 176 patients were available for analysis (missing data 16%). The average age was 56 years. For analysis on PTS, data was available for 163 patients (missing data 8%). The cumulative incidence of PTS was 63% at 5 years of follow-up. Patients who developed PTS had lower QOL scores for all questionnaires that were used. Outcomes on EQ-5D were 0.71 in PTS vs 0.88 in non-PTS, for VEINES-QOL 47.3 in PTS vs 53.6 in no PTS, for VEINES-Sym 46.6 in PTS vs 54.4 in no PTS. All differences were clinically relevant according to definitions of the study. The risk of bias was considered as ‘some concerns’ as it was unclear if excluded participants and missing data could have biased the results.

Ljungqvist (2018) conducted a cohort study, including 1040 females with a first episode of VTE. Patients were recruited from the "Thrombo Embolism Hormonal Study" (TEHS), a Swedish nation-wide case-control study on risk factors for venous thromboembolism in females 18-64 years of age. Among the 1040 patients recruited for follow-up, the average age was 49 years. The cumulative incidence of PTS was 20% after a median of six years of follow-up. Patients who developed PTS had lower QOL scores for all questionnaires that were used, i.e.:

- -8.6 for SF-36 pcs, P<0.001

- -4.9 for SF-36 mcs, P<0.001

- -8.4 for VEINES/QoL, P<0.001

- -10.6 for VEINES/Sym, P<0.001

Authors did not define a clinical relevant difference. The default threshold (> 0.5 SD) could not be used since SDs were not reported. The risk of bias was considered as ‘some concerns’ as it was unclear if non-participating patients for follow-up biased the results.

Exposure category Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease (CTEPD) without pulmonary hypertension (PH)/ Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension (CTEPH)

Definitions exposure category

Roman (2012) defined PH and CTEPH as outpatients aged ≥18 years old who had a clinical diagnosis of PH or CTEPH, without further clarification.

Tabaoda (2012) defined CTEPD as patients with CTEPD and a mean pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) <25 mmHg at baseline that underwent pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA). Date of last venous thromboembolism (VTE) was collected from patient’s notes. Time from last VTE to diagnosis was defined as time from last pulmonary embolism to diagnosis of CTED.

Definitions outcome

Roman (2012) defined health related quality of life (QOL) by using the Short-Form Health Survey-36 (SF-36PCS/MCS) and EQ-5D-5L questionnaire. Clinical relevance was non-defined.

Tabaoda (2012) defined health related QOL with the CAMPHOR-questionnaire (a measure of health-related QoL for patients with CTEPD without PH). Clinical relevance was non-defined.

Roman (2014) recruited consecutive patients diagnosed with PAH or CTEPH in a multi-center study. Recruitment and data collection for analysis were carried out by a pharmaceutical company (Pfizer). One hundred fifty-six patients completed the evaluation at the baseline visit and 135 (86.5%) completed the end of study visit after six months. Overall, 71% were females, with a mean age of 52 years. N=139 (89%) had PAH and n=17 (11%) had CTEPH. Seventy-six patients (49%) had idiopathic PAH (IPAH) and 23 (17%) had connective tissue disease-associated PAH (CTD-PAH). Twenty percent of patients were diagnosed in the 12 months prior to the start of the study and 80% were diagnosed earlier. Mean scores (+/- SD) for the QoL outcomes are reported in Table 2.

Table 2. Mean scores (SD) for Quality of life in patients with IPAH, CTD-PAH and CTEPH (Roman, 2014)

|

|

IPAH |

CTD-PAH |

CTEPH |

|

SF-36 PCS |

39 (9) |

31 (8) |

39 (9) |

|

SF-36 MCS |

47 (8) |

48 (10) |

47 (9) |

|

EQ visual analogue scale |

59 (21) |

53 (17) |

65 (17) |

IPAH: idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH); CTD-PAH: connective tissue disease-associated PAH; CTEPD: chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease; PCS: physical component summary; PH: pulmonary hypertension; MCS: mental component summary

The health related QoL score were considered ‘worse than those published for the normal population’ but references or direct comparisons with the normal population were not provided. Since results were non-compared to a population without PH or CTEPH, we could not determine if findings were clinically relevant. The risk of bias was considered as ‘concerns’ as there were unclear definitions of the patient population, unclear definitions of exposure, and because recruitment and data collection for analysis were not carried out by the authors.

Tabaoda (2014) screened 1019 patients who underwent PEA at Papworth Hospital. Of those, 42 patients fulfilled the criteria of having CTED. In a before-after study patients were compared with themselves for the outcome health related QoL. Mean age of the patients was 49 years and 60% of the patients were females. 90% of the patients had a documented history of VTE, with a third of patients having more than one episode. All patients were symptomatic, the most frequent symptom was exertional breathlessness, and all presented with NYHA functional class II or III limitation.

An improvement in the total score (median [IQR]) and all three domains of the CAMPHOR- questionnaire was observed at 6 months and sustained at 1 year; the total score went from 40 (33) at baseline to 11 (30) at six months post-PEA (P<0.001) and 11 (37) at one year post PEA (P<0.001); symptoms went from 15 (13) to 4 (12) (P<0.001) and 5 (12) (P<0.001), respectively; activity went from 10 (9) to 5 (6) (P=0.002) and 4 (11) (P<0.001), respectively; and QoL went from 14 (14) to 2 (11) (P=0.003) and 1 (12) (P=0.001), respectively. Since results were shown without SDs, we could not use the default threshold (> 0.5 SD) to determine if findings were clinically relevant. The risk of bias was considered as ‘no concerns’.

Exposure category Residual complaints

Definitions exposure category

Kahn (2017) defined residual complaints by maximal aerobic capacity defined by peak oxygen uptake (Vo2) as a percentage of predicted maximal Vo2 (Vo2 peak) on cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) at one year, with < 80% predicted Vo2 peak considered abnormal. CPET was interpreted in real time by a respirologist at each center who was blinded to patient information.

Keller (2018) defined residual complaints by New York Heart Association (NYHA) classes I-IV at six months of follow-up.

Tavoly (2018) defined residual complaints by NYHA class >1 (=persistent dyspnea) after a median follow of 3.6 years.

Valerio (2022) defined residual complaints by post-PE impairment (PPEI). The diagnosis of PPEI required deterioration in severity, or persistence of the highest severity, of at ≥ 1 ‘a’ (echocardiographic) and ≥ 1 ‘b’ (clinical, functional, or laboratory) parameter/abnormality. Deterioration or persistence was determined by comparison with the previous visit. For trichotomized (three-level) ‘a’ or ‘b’ parameters, the highest severity category was the one defined as ‘severe/high’; for dichotomized (two-level) parameters, it was the ‘moderate or severe/high’ category. Patients were considered to have reached the outcome ‘PPEI’ if they fulfilled the above criteria at the latest available follow-up visit (3, 12, or 24 months).

Definitions outcome

Kahn (2017) defined health related quality of life (QOL) by using the Short-Form Health Survey-36 (SF-36PCS/MCS). A difference of three points or more was defined as a clinically relevant difference.

Valerio (2022) defined health-related QoL using the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire and its corresponding visual analogue scale. Clinical relevance was non-defined.

Kahn (2017), Keller (2018), Tavoly (2017) and Valerio (2022) defined disease specific QOL by using the PEmb-QOL questionnaire. Clinical relevance was non-defined.

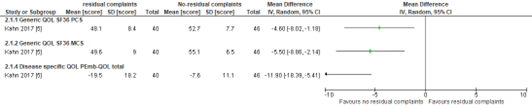

Kahn (2017) recruited out of n=984 patients with acute pulmonary embolism (PE), 100 patients at five hospitals. The average age was 50 years. At 1 year of follow-up, 40 of 86 patients (46%) had a percentage predicted Vo2 peak < 80% on CPET (i.e., residual complaints). Patients who had residual complaints had lower QOL for all questionnaires that were used. Differences for health related QOL were clinically relevant according to definitions of the study. Since authors could not define a clinical relevant difference for disease specific QOL, we used the default threshold (> 0.5 SD). By using this threshold, the difference for disease specific QOL was also clinically relevant, with some imprecision as confidence intervals were large. The risk of bias was considered as ‘some concerns’ as it was unclear if excluded participants biased the results.

Figure 2. Scores for Quality of life in patients with and without residual complaints (Kahn, 2017)

Keller (2018) recruited out of n=192 patients with acute PE, 101 patients at one outpatient clinic. The median age was 69 years. At six months of follow-up, (47%) had reported persisting dyspnea (NYHA class ≥II; of those, 19 patients (40.4%) were in NYHA class III/IV. Increasing NYHA classes were related to all PEmb‐QoL dimensions (see Table 3). authors did not define a clinical relevant difference for disease specific QOL. Since results were shown by regression techniques only (no SDs available) we could not use the default threshold (> 0.5 SD) to determine if findings were clinically relevant. The risk of bias was considered as ‘some concerns’ as it was unclear if excluded participants biased the results.

Table 3. Linear regression models for associations between PEmb-QoL dimensions and residual complaints categorized by NYHA classes at 6-months follow-up (Keller, 2018)

|

|

Dyspnea categorized by NYHA-classes |

|

|

β (95% CI) |

P-value |

|

|

Frequency of complaints (FO) |

0.5 (0.4-1.1) |

<0.001 |

|

Activities of daily living limitations (AD) |

0.8 (0.6-1.1) |

<0.001 |

|

Work related problems (WR) |

1.2 (0.8-1.5) |

<0.001 |

|

Social limitations (SL) |

0.4 (0.3-0.6) |

<0.001 |

|

Intensity of complaints (IO) |

0.4 (0.3-0.5) |

<0.001 |

|

Emotional complaints (EC) |

0.2 (0.0-0.4) |

0.037 |

CI: confidence interval; NYHA: New York Heart Association

Tavoly (2018) recruited consecutive patients diagnosed with PE in a single center study. After excluding 430 (51%) according to predefined exclusion criteria, 406 patients were found eligible and invited.

Of these, 203 patients completed the PEmb-QoL. After a median follow up of 3.6 (IQR 1.9–6.5) years, 96 (47%) patients reported dyspnea. The PEmb-QoL was higher (i.e., worse) in dyspneic patients (median score 12.5; IQR 9.9-15.0) compared to non-dyspneic patients (median score 8.0; IQR, 7.0-9.5), P<0.005. Since results were shown without SDs, we could not use the default threshold (> 0.5 SD) to determine if findings were clinically relevant. The risk of bias was considered as ‘some concerns’ as it was unclear if excluded participants biased the results.

Valerio (2022) included 1098 patients with PE at 17 study sites. For 81 patients, no follow-up data could be obtained after discharge. In total 880 patients could be assessed for PPEI. The median age was 64 years. At two years of follow-up, 16% had reported PPEI.

Patients who developed PPEI had worse QOL scores for all questionnaires that were used at 2 years of follow-up (Table 4).

Table 4. Scores for Quality of life in patients reporting post pulmonary embolism impairment (PPEI) and patients not reporting PPEI (Tavoly, 2018)

|

|

No PPEI |

PPEI |

P-value |

|

EQ-5D-L |

0.94 |

0.92 |

0.3 |

|

EQ visual analogue scale |

80 |

70 |

0.02 |

|

PEmb-QoL |

9.8% |

23.3% |

0.003 |

PPEI: post pulmonary embolism impairment; Pemb-QoL: Pulmonary Embolism Quality of Life Questionnaire

Since results were shown without SDs, we could not use the default threshold (> 0.5 SD) to determine if findings were clinically relevant. The risk of bias was considered as ‘some concerns’ as it was unclear if excluded participants biased the results.

Exposure category Psychosocial unwellness

Definitions exposure category

Erickson (2019) defined psychosocial unwellness as self-reported history of anxiety, or depression at time of enrollment.

Keller (2018) defined psychosocial unwellness as depression as confirmed diagnosis by a physician or administration of antidepressive drugs at 6 months of follow-up.

Definitions outcome

Erickson (2019) defined health related QoL by using the Short-Form Health Survey-12 PCS/MCS. In large national surveys of the entire U.S. population MCS scores have a mean of 50; thus, scores below 50 indicate worse health-related QoL than the typical U.S. person. Clinical relevance was non-defined.

Keller (2018) defined disease specific QOL by using the PEmb-QOL questionnaire. Clinical relevance was non-defined.

Erickson (2019) performed a cross-sectional survey in patients who self-reported VTE within the past two years before study enrollment. Patients diagnosed with cancer within the past two years were excluded. The study sample was recruited by a contract research agency (Hall & Partners, New York, New York, United States). Participants received an industry standard honorarium for their participation. A total of 971 patients accessed and completed the online survey. Data cleaning resulted in 64 patients being removed from the final data. The mean age of survey patients was 52 years, and most were female (57%). Self-reported VTE types were DVT (64%), PE alone (18%), or PE in combination with DVT (18%). The prevalence of anxiety was 27% and for depression 28%. The mean PCS and MCS scores were 41.7 and 46.7. Patients with a prior history of anxiety or depression were more likely to have below average QoL (anxiety 30% vs 16% and depression 33% vs 13% for PCS; anxiety 37% vs 13% and depression 41% vs 13% for MCS, all p-values <0.05). Since results on QoL were compared on an aggregate level (VTE vs the population), we could not determine if findings on anxiety/depression were clinically relevant. Risk of bias was considered as ‘concerns’ because of unclear definitions of patient population, self-reported definitions of exposure and because recruitment and data collection for analysis were not carried out by the authors.

Keller (2018) recruited out of n=192 patients with acute PE, 101 patients at one outpatient clinic. The median age was 69 years. At six months of follow-up, n=14 (16%) had reported depression. Depression was not consistently associated with QoL assessed by the PEmb‐QoL dimensions (point estimate from odds ratios between 1.0 to 2.6), but confidence intervals were wide for which reason it could not be determined if the effects were or were not clinically relevant. The risk of bias was considered as ‘some concerns’ as it was unclear if excluded participants biased the results.

Level of evidence of the literature

Summary

From the narrative review of a total of ten studies (from a selection of 106 unselected studies from the ICHOM analysis; Gwodz, 2022) that looked at chronic conditions that can arise after a VTE, the majority of these conditions were associated with a negative quality of life. As shown in Table 5, the prevalence of the chronic conditions was high.

Table 5. Results of the ten studies included in the narrative review, selection of studies from the ICHOM-analysis (Gwodz, 2022)

|

Study |

Prevalence exposure |

Difference |

Statistical significant |

Clinically relevant |

|

Kahn, 2008 |

47% |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Haig, 2016 |

63% |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Ljungqvist, 2018 |

20% |

Yes |

Yes |

CND |

|

Kahn, 2017 |

46% |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Keller, 2019 |

47% |

Yes |

Yes |

CND |

|

Tavoly, 2018 |

47% |

Yes |

Yes |

CND |

|

Valerio, 2022 |

16% |

Yes |

Yes |

CND |

|

Roman, 2013 |

CND |

Yes |

CND |

CND |

|

Taboada, 2014 |

CND |

Yes |

Yes |

CND |

|

Erickson, 2019 |

27% |

CND |

CND |

CND |

|

Keller, 2019 |

16% |

Imprecise |

No |

CND |

CND: could not be determined

For CTEPD without PH/CTEPH, the prevalence could not be extracted from the studies discussed, but a recent publication has shown that the prevalence of CTEPH is 2-3% (Luijten, 2023). The results from the narrative review could not be assessed using the GRADE methodology, but were consistent and precise within the domains of GRADE (with the exception of the variable psychological unwell-being (Erickson, 2019; Keller, 2019), where numbers were small leading to imprecision), fit within the patient population as defined in the PICO and had the main methodological limitation that due to selection criteria it was not always clear how generalizable the study results are to the total population.

Zoeken en selecteren

A review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: Do long term complications of venous thromboembolism have an impact on quality of life?

| P (Patients): | Patients aged > 18 years with venous thrombo-embolism (DVT and/or PE) |

| I (Intervention): | Residual complaints (pain, dyspnea), psychosocial unwellness, post thrombotic syndrome (PTS), chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease (CTEPD) without pulmonary hypertension (PH), chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) |

| C (Comparison): | The absence of residual complaints (pain, dyspnea), no psychosocial unwellness, PTS, CTEPD without PH, CTEPH |

| O (Outcome): | Quality of life (QOL) |

Definitions of exposure

The working group defined the presence (or absence) of exposure by using the definitions that were used in the study.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered general quality of life and/or disease specific quality of life as crucial outcomes for decision making.

For general quality of life: Measured by SF-12 MCS/PCS, SF-36 MCS/PCS, EQ-5D (lower scores indicate poorer QOL for both questionnaires).

For disease specific quality of life: Measured by PEmb-QoL (higher scores indicate poorer QOL) and/or VEINES-QOL/Sym questionnaires (lower scores indicate poorer QOL) and/or CAMPHOR questionnaire (higher scores indicate poorer QOL).

The working group did not define a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for the outcomes. Therefore, definitions of studies were used. If studies did not define a clinically relevant finding default thresholds were used: 0.5SD for continuous outcomes and a 25% difference in relative risk (RR< 0.8 or RR>1.25) for dichotomous outcomes.

ICHOM-VTE

The systematic search of ICHOM VTE has been adopted for this search query (search date 8 March 2011- 8 March 2021; see attachments). All MEDLINE articles have been fully screened by 2 independent members of the ICHOM-VTE taskforce (Gwodz, 2022). The first 20 of the 110 unique non-MEDLINE hits were also viewed. When no new results were found, according to ICHOM-methodology, the point of saturation was reached and no further searches were made. The ICHOM-VTE-project was supported from unrestricted grants from Bayer, Boston Scientific, The Dutch Thrombosis Association, Leiden University Medical Center, Leo Pharma, and King’s College London. It was not reported whether and if so, how the sponsoring parties contributed – besides the financial support - to this project.

Referenties

- Boon GJAM, Barco S, Bertoletti L, et al. Measuring functional limitations after venous thromboembolism: Optimization of the Post-VTE Functional Status (PVFS) Scale. Thromb Res. 2020;190:45-51. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.03.020.

- Boon GJAM, Ende-Verhaar YM, Bavalia R, et al. Non-invasive early exclusion of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism: the InShape II study. Thorax. 2021;76(10):1002-1009. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216324.

- Boon GJAM, Janssen SMJ, Barco S, et al. Efficacy and safety of a 12-week outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation program in Post-PE Syndrome. Thromb Res. 2021;206:66-75. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2021.08.012.

- Boon GJAM, van den Hout WB, Barco S, et al. A model for estimating the health economic impact of earlier diagnosis of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7(3):00719-2020. Published 2021 Sep 6. doi:10.1183/23120541.00719-2020.

- Delcroix M, Torbicki A, Gopalan D, et al. ERS statement on chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2021;57(6):2002828. Published 2021 Jun 17. doi:10.1183/13993003.02828-2020.

- Ende-Verhaar YM, van den Hout WB, Bogaard HJ, et al. Healthcare utilization in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16(11):2168-2174. doi:10.1111/jth.14266.

- Erickson RM, Feehan M, Munger MA, Tak C, Witt DM. Understanding Factors Associated with Quality of Life in Patients with Venous Thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 2019;119(11):1869-1876. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1696717.

- Gwozdz AM, de Jong CMM, Fialho LS, et al. Development of an international standard set of outcome measures for patients with venous thromboembolism: an International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement consensus recommendation. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(9):e698-e706. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00215-0.

- Haig Y, Enden T, Grøtta O, et al. Post-thrombotic syndrome after catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep vein thrombosis (CaVenT): 5-year follow-up results of an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3(2):e64-e71. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00248-3.

- Held M, Pfeuffer-Jovic E, Wilkens H, et al. Frequency and characterization of CTEPH and CTEPD according to the mPAP threshold > 20 mm Hg: Retrospective analysis from data of a prospective PE aftercare program. Respir Med. 2023;210:107177. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2023.107177.

- Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension [published correction appears in Eur Heart J. 2023 Apr 17;44(15):1312]. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(38):3618-3731. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac237

- Jervan Ø, Haukeland-Parker S, Gleditsch J, et al. The Effects of Exercise Training in Patients With Persistent Dyspnea Following Pulmonary Embolism: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Chest. 2023;164(4):981-991. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.04.042.

- de Jong CMM, de Wit K, Black SA, et al. Use of patient-reported outcome measures in patients with venous thromboembolism: communication from the ISTH SSC Subcommittee on Predictive and Diagnostic Variables in Thrombotic Disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2023;21(10):2953-2962. doi:10.1016/j.jtha.2023.06.023.

- Kahn SR, Shbaklo H, Lamping DL, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life during the 2 years following deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(7):1105-1112. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03002.x.

- Kahn SR, Hirsch AM, Akaberi A, et al. Functional and Exercise Limitations After a First Episode of Pulmonary Embolism: Results of the ELOPE Prospective Cohort Study. Chest. 2017;151(5):1058-1068. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.11.030.

- Keller K, Tesche C, Gerhold-Ay A, et al. Quality of life and functional limitations after pulmonary embolism and its prognostic relevance. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17(11):1923-1934. doi:10.1111/jth.14589.

- Klok FA, Huisman MV. Management of incidental pulmonary embolism. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(6):1700275. Published 2017 Jun 29. doi:10.1183/13993003.00275-2017.

- Klok FA, Ageno W, Ay C, et al. Optimal follow-up after acute pulmonary embolism: a position paper of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation and Right Ventricular Function, in collaboration with the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Atherosclerosis and Vascular Biology, endorsed by the European Respiratory Society. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(3):183-189. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab816.

- Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J. 2020;41(4):543-603. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405.

- Ljungqvist M, Holmström M, Kieler H, Lärfars G. Long-term quality of life and postthrombotic syndrome in women after an episode of venous thromboembolism. Phlebology. 2018;33(4):234-241. doi:10.1177/0268355517698620.

- Luijten D, Talerico R, Barco S, et al. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2023;62(1):2300449. Published 2023 Jul 7. doi:10.1183/13993003.00449-2023.

- Roman A, Barbera JA, Castillo MJ, Muñoz R, Escribano P. Health-related quality of life in a national cohort of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Arch Bronconeumol. 2013;49(5):181-188. doi:10.1016/j.arbres.2012.12.007.

- Taboada D, Pepke-Zaba J, Jenkins DP, et al. Outcome of pulmonary endarterectomy in symptomatic chronic thromboembolic disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1635-1645. doi:10.1183/09031936.00050114.

- Tavoly M, Wik HS, Sirnes PA, et al. The impact of post-pulmonary embolism syndrome and its possible determinants. Thromb Res. 2018;171:84-91. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2018.09.048.

- Ten Cate-Hoek AJ. Diagnosis and prevention of the post-thrombotic syndrome. Ned Tijdschr Hematol. 2018;15:319-25.

- Valerio L, Mavromanoli AC, Barco S, et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension and impairment after pulmonary embolism: the FOCUS study. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(36):3387-3398. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac206.

Evidence tabellen

Risk of bias table for cohort studies based on risk of bias tool by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University

|

Author, year |

Selection of participants

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population?

|

Exposure

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?

|

Outcome of interest

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study?

|

Confounding-assessment

Can we be confident in the assessment of confounding factors? |

Confounding-analysis

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these confounding variables? |

Assessment of outcome

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome?

|

Follow up

Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? In particular, was outcome data complete or imputed? |

Co-interventions

Were co-interventions similar between groups?

|

Overall Risk of bias

|

|

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Low, Some concerns, High |

|

|

Kahn, 2008 |

Probably yes

Reason: Participants were selected consecutively from outpatienst clinics, but there were exclusion criteria. |

Probably yes

Reason: questionnaire data with ascertainment rules were used.

|

Not applicable

Reason: Outcome concerned quality of life |

Not applicable

Reason: The stdy design was prognostic |

Not applicable

Reason: The stdy design was prognostic |

Definitely yes

Reason: validated questionnaire data with ascertainment rules were used. |

Probably yes

Reason: Follow up was up to 2 years after acute DVT. Of 387 enrolled participants, 260 attended the final visit. Cumulative incidences were obtained through Kaplan Meier, suggesting that censoring at a calendar end date. took place No loss to follow-up was described |

Not applicable

Reason: The stdy design was prognostic |

Some concerns

Unclear if excluded participants biased the results. Unclear if there was loss to follow-up |

|

Haig, 2016 |

Probably yes

Reason: participants from an open label clinical trial were included. There were some dropouts over 5 year follow-up |

Probably yes

Reason: questionnaire data with ascertainment rules were used.

|

Not applicable

Reason: Outcome concerned quality of life |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Definitely yes

Reason: validated questionnaire data with ascertainment rules were used. |

Probably yes

Reason: follow up was up to 5 years after acute DVT. Of 209 enrolled patients, 176 patients were available for analysis (missing data 16%). For analysis on PTS, data was available for 163 patients (missing data 8%). |

Not applicable

Reason: The stdy design was prognostic |

Some concerns

Unclear if excluded participants biased the results. Missing data nearing 20% of total |

|

Ljunqvist, 2018 |

Probably yes

Reason: Participants were selected from outpatienst clinics, through consent. For follow-up approximately 25% did not consent or provided information needed for follow-up |

Probably yes

Reason: questionnaire data with ascertainment rules were used.

|

Not applicable

Reason: Outcome concerned quality of life |

Not applicable

Reason: Outcome concerned quality of life |

Not applicable

Reason: The stdy design was prognostic |

Definitely yes

Reason: validated questionnaire data with ascertainment rules were used. |

Probably yes

Reason: Median follow was 6 years after VTE. Of 1050 enrolled patients, 1040 patients were available for analysis (missing data n=10) patients (missing data 8%). |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Some concerns

Unclear if excluded participants (nearing 25% of total) biased the results. |

|

Kahn, 2017 |

Probably yes

Reason: Participants were selected consecutively from outpatient clinics, but there were exclusion |

Definitely yes

Reason: Objective measures were used ( maximal Vo2) on cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET)and interpreted in real time by a respirologist at who was blinded to patient information.

|

Not applicable

Reason: Outcome concerned quality of life |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Definitely yes

Reason: validated questionnaire data with ascertainment rules were used. |

Probably yes

Reason: Follow up was up to 1 year after acute PE. |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Some concerns

Unclear if excluded participants biased the results. |

|

Keller, 2018 |

Probably yes

Reason: Participants were selected consecutively from one outpatient clinic (n=192), but there were exclusion criteria |

Definitely yes

Reason: Objective measures were used.

|

Not applicable

Reason: Outcome concerned quality of life |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Definitely yes

Reason: validated questionnaire data with ascertainment rules was used. |

Probably yes

Reason: Follow up was up to 0.5 years after acute PE. |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Some concerns

Unclear if excluded participants biased the results. |

|

Tavoly, 2018 |

Probably yes

Reason: Participants were selected consecutively from one outpatient clinic, but there were exclusion criteria (and not all participated. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Objective measures were used.

|

Not applicable

Reason: Outcome concerned quality of life |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Definitely yes

Reason: validated questionnaire data with ascertainment rules was used. |

Probably yes

Reason: Median Follow up was 3.6 years after acute PE. |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Some concerns

Unclear if excluded participants biased the results. |

|

Valerio, 2022 |

Probably yes

Reason: The FOCUS prospectively enrolled consecutive unselected patients with confirmed diagnosis of acute symptomatic PE. The study was performed at 17 hospitals in Germany. Patients were excluded if the diagnosis of PE was an incidental finding during diagnostic work up for another disease; if they had A documented history of confirmed CTEPH; or if they had already been enrolled in this study in the past |

Definitely yes

Reason: Objective measures were used.

|

Not applicable

Reason: Outcome concerned quality of life |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Definitely yes

Reason: validated questionnaire data with ascertainment rules was used. |

Probably yes

Reason: Maximum Follow up was 2 years after acute PE. Of 1098 patienmts included 81 patienst did not provide follow-up data (7%). PPEI could be evaluated in 880 patients |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Some concerns

Unclear if missing data biased the results. |

|

Roman, 2012 |

Unclear

Reason: consecutive patients diagnosed with PAH or CTEPH in a multi-center study, further undefined. |

Definitely no

Reason: the exposure was not defined |

Not applicable

Reason: Outcome concerned quality of life |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Definitely yes

Reason: validated questionnaire data with ascertainment rules was used. |

Probably yes

Reason: Follow up was 6 months. Of 156 patients included 21 patienst did not provide follow-up data (13%). |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Concerns. Unclear definitions of patient population, unclear definitions of exposure. Recruitment and data collection for analysis were not carried out by the authors |

|

Tabaoda, 2014 |

Probably yes

Authors screened 1019 patients who underwent PEA at Papworth Hospital. Of those, 42 patients fulfilled the criteria of having CTED

|

Definitely yes

Reason: Objective measures were used.

|

Not applicable

Reason: Outcome concerned quality of life |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Definitely yes

Reason: validated questionnaire data with ascertainment rules was used. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Follow up was up to 1 year after PEA. There was no loss to follow-up |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

No concerns

|

|

Erickson, 2019 |

Probably no

Reason: This was a survey with an unknown response rate (but determined bu authors as ‘less than ideal’) that relied on patient self-report for index VTE identification and could only compare outcomes with aggregate findings drom a normal population. Recruitment went through a contract research agency |

Probably yes

Reason: the exposure was identified through self-report (potential information bias) |

Not applicable

Reason: Outcome concerned quality of life |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Not applicable

Reason: The study design was prognostic |

Definitely yes

Reason: validated questionnaire data with ascertainment rules was used. |

Probably yes

Reason: This was a a cross-sectional survey in patients who self-reported VTE within the past 2 years before study enrollment. A total of 971 patients accessed and completed the online survey. Data cleaning resulted in 64 patients (6.5%) being removed from the final data. |

|

Concerns. Unclear definitions of patient population, self-reported definitions of exposure. Recruitment and data collection for analysis were not carried out by the authors. |

Table ICHOM-studies that reported on the outcome quality of life

|

ICHOM ID |

First author |

Year |

Title |

|

5 |

Chen |

2019 |

Long-Term Clinical Outcomes of Complicated Retrievable Inferior Vena Cava Filter for Deep Venous Thrombosis Patients: Safety and Effectiveness |

|

7 |

Clay |

2018 |

Cost-effectiveness of edoxaban compared to warfarin for the treatment and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism in the UK |

|

9 |

Guercini |

2016 |

The management of patients with venous thromboembolism in Italy: insights from the PREFER in VTE registry |

|

16 |

Kumar |

2014 |

Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Young Adults With Post-Thrombotic Syndrome: Results From a Cross-Sectional Study |

|

25 |

Staniszewska |

2020 |

The good, bad and the ugly of the Acute Venous Thrombosis: Thrombus Removal with Adjunctive Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis trial from the viewpoint of clinicians |

|

27 |

Svedman |

2019 |

Deep venous thrombosis after Achilles tendon rupture is associated with poor patient‐reported outcome |

|

28 |

Wagenhäuser |

2019 |

Clinical outcomes after direct and indirect surgical venous thrombectomy for inferior vena cava thrombosis |

|

31 |

Vedantham |

2017 |

Pharmacomechanical Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis for Deep- Vein Thrombosis |

|

32 |

Schmitz |

2019 |

Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction INCIDENCE, OUTCOME, AND RISK FACTORS |

|

34 |

Kahn |

2020 |

Quality of life after pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis for proximal deep vein thrombosis |

|

35 |

Wu |

2018 |

The association between major complications of immobility during hospitalization and quality of life among bedridden patients: A 3 month prospective multi-center study |

|

36 |

Haig |

2016 |

Post-thrombotic syndrome after catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep vein thrombosis (CaVenT): 5-year follow-up results of an open-label, randomised controlled trial |

|

40 |

Monreal |

2019 |

Deep Vein Thrombosis in Europe—Health- Related Quality of Life and Mortality |

|

42 |

Weinberg |

2019 |

Relationships Between the Use of Pharmacomechanical Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis, Sonographic Findings, and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Acute Proximal DVT: Results from the ATTRACT Multicenter Randomized Trial |

|

47 |

Eirckson |

2019 |

Understanding Factors Associated with Quality of Life in Patients with Venous Thromboembolism |

|

56 |

Garcia |

2020 |

Ultrasound-accelerated thrombolysis and venoplasty for the treatment of the postthrombotic syndrome: Results of the ACCESS PTS Study |

|

59 |

Dumantepe |

2019 |

Endophlebectomy of the common femoral vein and endovascular iliac vein recanalization for chronic iliofemoral venous occlusion |

|

62 |

Bradbury |

2019 |

A randomised controlled trial of extended anticoagulation treatment versus standard treatment for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) and post-thrombotic syndrome in patients being treated for a first episode of unprovoked VTE (the ExACT study) |

|

64 |

Chuang |

2019 |

Comparison of quality of life measurements: EQ-5D-5L versus disease/treatment-specific measures in pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis |

|

66 |

Sebastian |

2020 |

Early clinical outcomes for treatment of post-thrombotic syndrome and common iliac vein compression with a hybrid oblique self-expanding nitinol stent – the TOPOS study |

|

67 |

Razavi |

2020 |

Correlation between Post-Procedure Residual Thrombus and Clinical Outcome in Deep Vein Thrombosis Patients Receiving Pharmacomechanical Thrombolysis in a Multicenter Randomized Trial |

|

69 |

Engeseth |

2019 |

Does the Villalta scale capture the essence of postthrombotic syndrome? A qualitative study of patient experience and expert opinion |

|

70 |

Gombert |

2018 |

Patency rate and quality of life after ultrasound-accelerated catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep vein thrombosis |

|

71 |

Chuang |

2018 |

Deep-vein thrombosis in Europe — Burden of illness in relationship to healthcare resource utilization and return to work |

|

73 |

Strijkers |

2015 |

Validation of the LET classification |

|

74 |

Lutsey |

2020 |

Long-Term Association of Venous Thromboembolism With Frailty, Physical Functioning, and Quality of Life: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study |

|

76 |

Siddiqui |

2020 |

Predictors of Poor Quality of Life after Primary Lower Limb Deep Venous Thrombosis: A Perspective from a Developing Nation |

|

80 |

Utne |

2018 |

Rivaroxaban versus warfarin for the prevention of post-thrombotic syndrome |

|

82 |

Alibaz-Oner |

2016 |

Post-thrombotic syndrome and venous disease-specific quality of life in patients with vascular Behçet’s disease |

|

90 |

Qian |

2020 |

The perplexity of catheter‑directed thrombolysis for deep venous thrombosis: the approaches play an important role |

|

91 |

Ruihua |

2017 |

Technique and Clinical Outcomes of Combined Stent Placement for Postthrombotic Chronic Total Occlusions of the Iliofemoral Veins |

|

92 |

Ljungqvist |

2018 |

Long-term quality of life and postthrombotic syndrome in women after an episode of venous thromboembolism |

|

96 |

Jiang |

2017 |

Mid-term outcome of endovascular treatment for acute lower extremity deep venous thrombosis |

|

97 |

Wagenhäuser |

2018 |

Open surgery for iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis with temporary arteriovenous fistula remains valuable |

|

99 |

Hogg |

2014 |

Validity of standard gamble estimated quality of life in acute venous thrombosis |

|

104 |

Catarinella |

2015 |

Quality-of-life in interventionally treated patients with post-thrombotic syndrome |

|

107 |

Marvig |

2015 |

Quality of life in patients with venous thromboembolism and atrial fibrillation treated with coumarin anticoagulants |

|

108 |

Pesser |

2020 |

Same Admission Hybrid Treatment of Primary Upper Extremity Deep Venous Thrombosis with Thrombolysis, Transaxillary Thoracic Outlet Decompression, and Immediate Endovascular Evaluation |

|

110 |

Bi |

2019 |

Long-term outcome and quality of life in patients with iliac vein compression syndrome after endovascular treatment |

|

113 |

Engelberger |

2017 |

Ultrasound-assisted versus conventional catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis: 1-year follow-up data of a randomized-controlled trial |

|

114 |

Dumantepe |

2018 |

The effect of Angiojet rheolytic thrombectomy in the endovascular treatment of lower extremity deep venous thrombosis |

|

115 |

Tichelaar |

2016 |

A Retrospective Comparison of Ultrasound-Assisted Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis and Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis Alone for Treatment of Proximal Deep Vein Thrombosis |

|

116 |

Nawasrah |

2021 |

Incidence and severity of postthrombotic syndrome after iliofemoral thrombosis – results of the Iliaca-PTS – Registry |

|

121 |

Lozano Sanchez |

2013 |

Negative impact of deep venous thrombosis on chronic venous disease |

|

123 |

Holmes |

2014 |

Efficacy of a short course of complex lymphedema therapy or graduated compression stocking therapy in the treatment of post-thrombotic syndrome |

|

124 |

Mol |

2016 |

One versus two years of elastic compression stockings for prevention of post-thrombotic syndrome (OCTAVIA study): randomised controlled trial |

|

128 |

Mean |

2014 |

The VEINES-QOL/Sym questionnaire is a reliable and valid disease-specific quality of life measure for deep vein thrombosis in elderly patients |

|

129 |

Broholm |

2011 |

Postthrombotic syndrome and quality of life in patients with iliofemoral venous thrombosis treated with catheter-directed thrombolysis |

|

135 |

Persson |

2011 |

Deep venous thrombosis after surgery for achilles tendon rupture: a provoked transient event with minor long-term sequelae |

|

136 |

Keita |

2017 |

Assessment of quality of life, satisfaction with anticoagulation therapy, and adherence to treatment in patients receiving long-course vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants for venous thromboembolism |

|

141 |

Vogel |

2012 |

Common femoral endovenectomy with iliocaval endoluminal recanalization improves symptoms and quality of life in patients with postthrombotic iliofemoral obstruction |

|

142 |

Lee |

2015 |

Role of coexisting contralateral primary venous disease in development of post-thrombotic syndrome following catheter-based treatment of iliofemoral deep venous thrombosis |

|

145 |

Zhang |

2013 |

A prospective randomized trial of catheter-directed thrombolysis with additional balloon dilatation for iliofemoral deep venous thrombosis: a single-center experience |

|

150 |

Meng |

2013 |

Stenting of iliac vein obstruction following catheter-directed thrombolysis in lower extremity deep vein thrombosis |

|

152 |

Ast |

2014 |

Clinical outcomes of patients with non-fatal VTE after toral knee arthroplasty |

|

155 |

Lee |

2021 |

Performance of two clinical scales to assess quality of life in patients with post-thrombotic syndrome |

|

159 |

Ye |

2016 |

Outcomes of stent placement for chronic occlusion of a filter-bearing inferior vena cava in patients with severe post-thrombotic syndrome |

|

160 |

Enden |

2013 |

Symptom burden and job absenteeism after treatment with additional catheter-direced thrombolysis for deep vein thrombosis |

|

161 |

Roberts |

2014 |

Post-thrombotic syndrome is an independent determinant of health-related quality of life following both first proximal and sital deep vein thrombosis |

|

162 |

Kearon |

2019 |

Pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis in acute femoral-popliteal deep vein thrombosis: analysis from a stratified randomized trial |

|

163 |

Yuan |

2019 |

Diagnosis and treatment of acquired ateriovenous fistula after lower extremity deep vein thrombosis |

|

166 |

Warner |

2013 |

Functional outcomes following catheter-based iliac vein stent placement |

|

170 |

Yu |

2018 |

The midterm effect of iliac vein stenting following catheter-directed thrombolysis for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis |

|

171 |

Sarici |

2013 |

Our early experience with iliofemoral vein stenting in patients with post-thrombotic syndrome |

|

172 |

Ye |

2014 |

Technical details and clinical outcomes of transpopliteal venoous stent placement for postthrombotic chronic total occlusion of the iliofemoral vein |

|

173 |

Comerota |

2019 |

Endovascular thrombus reomval for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis: analysis from a stratified multicenter randomized trial |

|

8 |

Filipppo Corsi |

2017 |

Life-threatening massive pulmonary embolism rescued by venoarterial- extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

|

33 |

Kline |

2013 |

Treatment of submassive pulmonary embolism with tenecteplase or placebo: cardiopulmonary outcomes at 3 months: multicenter double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial |

|

37 |

Rolving |

2020 |

Effect of a Physiotherapist-Guided Home-Based Exercise Intervention on Physical Capacity and Patient-Reported Outcomes Among Patients With Acute Pulmonary Embolism A Randomized Clinical Trial |

|

41 |

Kahn, S. |

2017 |

Functional and Exercise Limitations After a First Episode of Pulmonary Embolism Results of the ELOPE Prospective Cohort Study |

|

44 |

Keller, K. |

2018 |

Quality of life and functional limitations after pulmonary embolism and its prognostic relevance |

|

48 |

Tavoly, M. |

2018 |

The impact of post-pulmonary embolism syndrome and its possible determinants |

|

49 |

Stoller |

2019 |

Clinical presentation and outcomes in elderly patients with symptomatic isolated subsegmental pulmonary embolism |

|

50 |

Hoole |

2020 |

Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: the UK experience |

|

51 |

Kamenskaya |

2020 |

Long‑term health‑related quality of life after surgery in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension |

|

52 |

Notten |

2020 |

Prevalence of venous obstructions in (recurrent) venous thromboembolism: a case-control study |

|

54 |

Taboada |

2014 |

Outcome of pulmonary endarterectomy in symptomatic chronic thromboembolic disease |

|

55 |

Cires-Drouet |

2020 |

Safety of exercise therapy after acute pulmonary embolism |

|

60 |

Chuang |

2019 |

Health‐related quality of life and mortality in patients with pulmonary embolism: a prospective cohort study in seven European countries |

|

65 |

Jeong |

2019 |

Relationship of Lower-extremity Deep Venous Thrombosis Density at CT Venography to Acute Pulmonary Embolism and the Risk of Postthrombotic Syndrome |

|

68 |

Kamenskaya |

2017 |

Factors affecting the quality of life before and after surgery in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension |

|

72 |

Darocha |

2017 |

Improvement in Quality of Life and Hemodynamics in Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension Treated With Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty |

|

75 |

Tavoly |

2016 |

Health-related quality of life after pulmonary embolism: a cross-sectional study |

|

77 |

Walen |

2017 |

Safety, feasibility and patient reported outcome measures of outpatient treatment of pulmonary embolism |

|

78 |

Knox |

2019 |

Preservation of Cardiopulmonary Function in Patients Treated with Ultrasound-Accelerated Thrombolysis in the Setting of Submassive Pulmonary Embolism |

|

79 |

Rao |

2019 |

Ultrasound-assisted versus conventional catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute pulmonary embolism: A multicenter comparison of patient-centered outcomes |

|

81 |

Ivarsson |

2018 |

Health-related quality of life, treatment adherence and psychosocial support in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension |

|

93 |

van Es |

2013 |

Quality of life after pulmonary embolism as assessed with SF-36 and PEmb-QoL |

|

98 |

Fukui |

2016 |

Efficacy of cardiac rehabilitation after balloon pulmonary angioplasty for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension |

|

102 |

Urushibara |

2015 |

Effects of Surgical and Medical Treatment on Quality of Life for Patients With Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension |

|

103 |

Piazza |

2020 |

One-Year Echocardiographic, Functional, and Quality of Life Outcomes After Ultrasound-Facilitated Catheter-Based Fibrinolysis for Pulmonary Embolism |

|

105 |

Akaberi |

2018 |

Determining the minimal clinically important difference for the PEmbQoL questionnaire, a measure of pulmonary embolism-specific quality of life |

|

117 |

Harzheim |

2013 |

Anxiety and depression disorders in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboemoblic pulmonary hypertension |

|

118 |

Sertic |

2020 |

Mid-term outcomes with the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiopulmonary failure secondary to massive pulmonary emoblism |

|

122 |

Inagaki |

2014 |