Corticosteroïden

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van corticosteroïden in de behandeling van patiënten met ARDS?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg bij een patiënt met ARDS (PaO2/FiO2 <200 mmHg) binnen 24-72 uur te starten met methylprednisolon 1 mg/kg ideaal lichaamsgewicht, danwel 20 mg dexamethason.

Overweeg als reeds gestart is met hydrocortison in het kader van septische shock, de behandeling met hydrocortison minimaal 7 dagen te continueren in het geval van ARDS met een PaO2/FiO2 ratio <200 mmHg en wissel niet van corticosteroïd.

Gebruik vervolgens het volgende (afbouw)schema:

|

|

Methylprednisolon |

Dexamethason |

Hydrocortison |

|

Dosering |

1mg/kg IBW dag1-14 0,5mg/kg D15-21 0,25mg/kg D22-25 0,125mg/kg D26-28 |

20mg D1-5 10mg D6-10 |

7 dagen 200mg |

Overwegingen

Er is een literatuuranalyse verricht naar de effectiviteit van de toediening van corticosteroïden bij patiënten met ARDS die worden beademd. Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat mortaliteit kan worden gezegd dat gebruik van Methylprednisolon de 28-daagse mortaliteit lijkt te verminderen, maar niet de 60-daagse mortaliteit. Bij gebruik van Hydrocortison lijken zowel de 28-daagse als 60-daagse mortaliteit te verminderen. Gebruik van Dexamethason lijkt te resulteren in een lagere 60-daagse en ziekenhuis mortaliteit. Merk op dat de middelen niet ten opzichte van elkaar zijn vergeleken en er daarom geen conclusies getrokken kunnen worden over de prestaties van de middelen ten opzichte van elkaar.

De totale bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat mortaliteit is laag, doordat de studies zijn uitgevoerd in kleine patiëntengroepen. Voor belangrijke, maar niet cruciale uitkomstmaten is de bewijskracht ook laag, of zelfs zeer laag. De duur van beademing lijkt te verkorten bij gebruik van Hydrocortison, maar het effect op de duur van beademing is onzeker bij gebruik van Methylprednisolon en Dexamethason. Het gebruik van Methylprednisolon lijkt de duur van IC en ziekenhuisverblijf te verkorten, tevens lijken er bij gebruik van dit middel minder secundaire infecties voor te komen. Wel lijkt er vaker neuromusculaire zwakte te ontstaan bij het gebruik van Methylprednisolon. De bewijskracht voor deze uitkomstmaten is laag tot zeer laag.

Uit bovenstaande bevindingen met zwakke bewijskracht kunnen geen harde conclusies getrokken worden, onder andere vanwege de heterogeniciteit van de onderzochte steroïden en de verschillen in dosering. Echter, ongeacht welk steroïd of welke dosering wordt gebruikt lijkt er een effect te bestaan. Hierbij kunnen de volgende opmerkingen worden gemaakt:

- Bij niet alle studies is verduidelijkt wat de ernst van de ARDS is, al zijn de meeste inclusies gedaan bij matig-ernstige ARDS (PaO2/FiO2 ratio <200 mmHg).

- Bij de literatuursearch is ervoor gekozen om alleen artikelen gepubliceerd na 2000 te gebruiken (na uitkomen van de ARDS-netwerk studie, oftewel sinds de start van longprotectieve beademing, met lage teugvolumes en plateau drukken< 30cmH₂O). Desondanks is het niet altijd duidelijk of alle patiënten in de beschreven studies longprotectief werden beademd. De werkgroep is van mening dat de manier van ventilatie geen afbreuk doet aan het gevonden effect van de steroïden.

- De meeste studies zijn verricht bij patiënten met een infectieuze oorzaak van ARDS (sepsis en pneumonie). Daardoor kan de werkgroep met name uitspraken doen over ARDS met een infectieuze etiologie, omdat daar het voordeel van corticosteroïden gebruik (lage bewijskracht) is aangetoond. Voor patiënten met een andere etiologie is het starten van corticosteroïden ook te overwegen; uit de beschreven studies komt namelijk niet duidelijk naar voren of de etiologie van invloed is op de werkzaamheid van steroïden bij ARDS.

- In de meeste studies wordt er na 24 uur gestart met corticosteroïden, omdat het stellen van de syndroomdiagnose ARDS, met onderliggende etiologie, enige tijd behoeft en er in studieverband tijd nodig is voor het verkrijgen van informed consent. Over de vlot opknappende patiënt (<24 uur) en de patiënt met milde ARDS (PaO2/FiO2>200 mmHg) kunnen vanuit deze literatuursearch geen duidelijke aanbevelingen gedaan worden met betrekking tot steroïden gebruik, maar de werkgroep is van mening dat steroïden in deze groep geen meerwaarde hebben.

Voorts zijn de gebruikte doseringen ten opzichte van elkaar verschillend in de beschreven studies, evenals de starttijd, duur van behandeling en gebruikte middelen. In de literatuur is het effect van methylprednisolon en dexamethason het grootste vanwege de grootte van de studies en onze aanbeveling is dan ook een van deze middelen te gebruiken. Indien er reeds vanwege een septische shock is gestart met hydrocortison, dan lijkt het niet zinvol nog van corticosteroïd te wisselen. In de meeste studies waarin een voordeel voor het gebruik van steroïden werd gevonden, werd binnen 24-72 uur na verdenking op de diagnose ARDS gestart met de behandeling. In de studie van Steinberg, die geen effect liet zien van Methylprednisolon op de 60 dagen mortaliteit werd pas na 7 dagen gestart met Methylprednisolon. De werkgroep adviseert om te zorgen voor een vroege herkenning van de syndroomdiagnose ARDS en binnen 24-72 uur te starten met steroïden.

De werkgroep kan geen advies geven welk steroid beter is dan de ander, omdat deze niet onderling vergeleken zijn.

Indien gekozen wordt voor toediening van methylprednisolon, adviseert de werkgroep een dosering van 1mg/kg ideaal lichaamsgewicht volgens het Meduri schema.

De literatuur geeft niet goed aan of steroïden gedoseerd moeten worden op actueel of ideaal lichaamsgewicht. Aan de hand van farmacologische overwegingen (Czock 2005) en expert opinion van apothekers en immunologen, lijkt doseren op ideaal lichaamsgewicht bij met name adipeuze patiënten een logische keuze bij methylprednisolon, omdat in deze patiëntencategorie de T1/2 lijkt toegenomen met een afgenomen klaring. Het distributievolume is gerelateerd aan het ideale lichaamsgewicht, hetgeen de suggestie geeft dat methylprednisolon niet opgenomen wordt in het vetweefsel. De werkgroep adviseert om te kiezen voor dosering op basis van het ideaal lichaamsgewicht bij methylprednisolon, zeker bij adipeuze patiënten.

Ideaal lichaamsgewicht is voor mannen 50 + [0,91 x (lengte in cm – 154,4)] en voor vrouwen is het 45,5 + [0,91 x (lengte in cm – 152,4)].

Een equivalente dosis hydrocortison is ongeveer 300 mg hydrocortison per dag, deze wordt gedoseerd onafhankelijk van het lichaamsgewicht. De beschreven studies zijn echter verricht met doseringen vanaf 200mg gedurende 7 dagen en lieten een positief effect zien op de mortaliteit en beademingsduur bij patiënten met ARDS. De studie van Villar start met 20mg dexamethason. Dat is in vergelijking met methylprednisolon per kg ideaal lichaamsgewicht ongeveer de dubbele dosering.

Als de patiënt na 7 dagen respiratoir niet verbetert aan de beademing, met een aanhoudend klinisch en/of radiologisch beeld van ARDS conform de Berlin criteria, kan men spreken van een “non-resolving” ARDS. Een nieuwe kuur met steroïden valt dan te overwegen, de evidence voor verbetering van de survival is echter marginaal. De literatuur die er is adviseert om dan een hogere dosering methylprednisolon van 2mg/kg ideaal lichaamsgewicht te geven. Let wel dat het belangrijk is om bij een “non-resolving” ARDS, diagnostiek te verrichten naar de onderhoudende factor waardoor de ARDS niet opknapt, voorafgaande aan hervatten/starten van steroïden (zie module ‘Diagnostiek ARDS’).

De werkgroep adviseert om bij het gebruik van methylprednisolon het afbouwschema volgens Meduri (2018) te gebruiken en bij dexamethason de afbouw volgens de studie van Villar (2020), omdat na staken van steroïden de inflammatie kan terugkeren (zie tabel 2). Mocht de patiënt onder corticosteroïden worden ge-extubeerd vanwege snelle respiratoire verbetering dan kan men overwegen de steroïden versneld af te bouwen.

Tabel 2: Steroïd-(afbouw)schema’s

|

Dexamethason (Villar 2020) |

Afbouwschema: |

|

20mg dag 1-5 |

10mg dag 6-10 |

|

Methylprednisolon (Meduri 2018) |

Afbouwschema mg/kg IBW |

|

1mg/kg dag 1-14 |

0,5mg/kg dag 15-21 0,25mg/kg dag 22-25 0,125mg/kg dag 26-28 |

|

Methylprednisolon (Meduri 2018) bij late start en/of “non-resolving” ARDS |

Afbouwschema: |

|

2mg/kg dag 1-14 |

1mg/kg dag 15-21 0,5mg/kg dag 22-25 0,25mg/kg dag 26-28 0,125mg/kg dag 29-31 |

Complicaties:

De angst voor infecties lijkt ongegrond; er lijken zelfs minder nieuwe infecties op te treden bij het gebruik van corticosteroïden. Ten aanzien van de ICU-acquired weakness is de werkgroep van mening dat deze bijwerking niet alleen toe te schrijven is aan het gebruik van corticosteroïden, maar ook aan andere behandelstrategieën en de mogelijk aanwezige infectie.

Op andere bijwerkingen van corticosteroïden is niet ingegaan in de literatuursamenvatting. Het effect van corticosteroïden op het voorkomen van hyperglycemiën zou nog relevant kunnen zijn. Deze bijwerking wordt echter niet gerapporteerd in de besproken studies. De werkgroep is daarbij van mening dat hyperglycemie met behulp van insuline adequaat kan worden bestreden en geen ernstige belemmering is voor het gebruik van steroïden.

De bijwerkingen van corticosteroïden lijken dus beperkt te blijven tot ICU aquired weakness.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor patiënten heeft het gebruik van steroïden voornamelijk voordelen met een mogelijk lagere mortaliteit, kortere beademingsduur en IC-verblijf, met wel als belangrijke bijwerking ICU acquired weakness. Dit kan voor sommigen ernstig invaliderend zijn maar is met behulp van revalidatie wel (ten dele) reversibel. Het is daarom belangrijk dat de revalidatie al op de IC gestart wordt (zie de richtlijn Nazorg en revalidatie voor Intensive Care patiënten). De werkgroep is van mening dat de voordelen van de toediening van corticosteroïden voor de patiënt groter zijn dan de nadelen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De kosten van behandeling met corticosteroïden zijn enkel de kosten voor het geneesmiddel, dit zal variëren van 2,50-35 euro per dag afhankelijk van het voorgeschreven middel met een maximale loopduur van enkele weken. Aangezien het middel mogelijk voor een korter IC- en ziekenhuisverblijf zorgt (en daarmee afname van IC behandeldag kosten) zal dit opwegen tegen de kosten van het medicijn. Wel kan de toename van ICU-acquired weakness zorgen voor kosten ten behoeve van revalidatie na de ziekenhuisopname, de exacte kosten hiervan zijn de werkgroep niet bekend.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Corticosteroïden kunnen zonder aanpassingen aan de dagelijkse zorg worden toegevoegd en hebben dus geen implementatie nodig. Op de meeste afdelingen is het gebruik van corticosteroïden voor de behandeling van sepsis al volledig geïntegreerd

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Vroeg starten met steroïden (binnen 24-72 uur bij ARDS (PaO2/FiO2-ratio < 200 mmHg) kan leiden tot reductie in mortaliteit en beademingsduur/dagen, ook bij een infectieuze etiologie van de ARDS. Het snel identificeren van het onderliggend ziektebeeld van ARDS is derhalve van belang (zie hoofdstuk Diagnostiek van ARDS). De steroïden leiden niet tot toename van infectieuze complicaties. De ICU-acquiered weakness die optreedt is waarschijnlijk eerder multifactorieel bepaald, dan alleen toe te schrijven aan het effect van de steroïden. De werkgroep is derhalve van mening dat de voordelen van de behandeling opwegen tegen de bijwerkingen die de patiënt kan ervaren. Bovendien verwacht de werkgroep dat de behandeling met corticosteroïden zeker niet leidt tot significante stijgende zorgkosten (eerder afname door minder beademingssdagen) of problemen met de implementatie van vroege toediening van corticosteroïden.

De werkgroep kan geen harde aanbeveling doen naar het te gebruiken type corticosteroïd maar adviseert of te starten met methylprednisolon 1 mg/kg ideaal lichaamsgewicht, danwel 20 mg dexamethason, omdat deze middelen in de grotere studies onderzocht zijn.

De werkgroep adviseert om als reeds gestart is met hydrocortison, in het kader van sepsis, dit minimaal 7 dagen te continueren in het geval van ARDS met een PaO2/FiO2 ratio <200 mmHg en niet te veranderen van steroïd.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Bij ARDS speelt inflammatie (biotrauma), naast mechanische schade, een grote rol in het ontstaan van het klinische beeld van ARDS met ernstige oxygenatie/ventilatie stoornissen en een afgenomen compliantie. Voor de mechanische schade zijn er concepten ontwikkeld om longprotectief te beademen. Steroïden kunnen mogelijk een rol spelen in het afremmen van inflammatie met daardoor een snellere resolutie van de longafwijkingen, een kortere beademingsduur, betere overleving, minder ICU-acquired weakness en minder pulmonale schade op de langere termijn (Czock 2005). Echter er is nog geen consensus wanneer steroïden te geven en bij welke patiënt. Voorts zijn middel, dosis en duur tevens nog vraagstukken die beantwoord moeten worden, naast uiteraard de bijwerkingen op de korte en lange termijn. De ESICM ARDS guideline bevat geen hoofdstuk over de toepassing van corticosteroiden bij ARDS; een vergelijk is derhalve niet mogelijk.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Mortality

|

low GRADE |

Treatment with corticosteroids (Methylprednisolone or Hydrocortisone) may result in lower 28-day mortality compared to no treatment with corticosteroids in mechanical ventilated patients with ARDS.

Source Methylprednisolone: Meduri, 2018 Source Hydrocortisone: Mammen, 2020 (Liu, 2012; Tongyoo, 2018) |

|

low GRADE |

Treatment with corticosteroids (Methylprednisolone) may result in little to no difference in 60-day mortality compared to no treatment with corticosteroids in mechanical ventilated patients with ARDS.

Source: Mammen, 2020 (Steinberg, 2006) |

|

low GRADE |

Treatment with corticosteroids (Hydrocortisone) may result in lower 60-day mortality compared to no treatment with corticosteroids in mechanical ventilated patients with ARDS.

Source: Mammen, 2020 (Tongyoo, 2016) |

|

low GRADE |

Treatment with corticosteroids (Dexamethasone) may result in lower 60-day and hospital-mortality compared to no treatment with corticosteroids in mechanical ventilated patients with ARDS.

Source: Mammen, 2020 (Villar, 2020) |

Quality of life

|

- GRADE |

No conclusion could be drawn regarding the effect of corticosteroids on quality of life in mechanical ventilated patients with ARDS as no studies reporting quality of life and meeting the inclusion criteria were found. |

Duration of mechanical ventilation

|

low GRADE |

Treatment with corticosteroids (Hydrocortisone) may reduce duration of mechanical ventilation compared to no treatment with corticosteroids in mechanical ventilated patients with ARDS.

Source Hydrocortisone: Mammen, 2020 (Tongyoo, 2016) |

|

very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of treatment with corticosteroids (Methylprednisone or Dexamethasone) on the duration of mechanical ventilation in mechanical ventilated patients with ARDS.

Source Methylprednisone: Mammen, 2020 (Meduri, 2007; Rezk, 2013) Source Dexamethasone: Mammen, 2020 (Villar, 2020) |

Length of stay (hospital/ICU)

|

low GRADE |

Treatment with corticosteroids (Methylprednisolone) may reduce length of hospital/ICU-stay compared to no treatment with corticosteroids in mechanical ventilated patients with ARDS.

Source: Mammen, 2020 (Meduri, 2007) |

ICU-acquired neuromuscular weakness

|

low GRADE |

Treatment with corticosteroids (Methylprednisolone) may result in increased neuromuscular weakness compared to no treatment with corticosteroids in mechanical ventilated patients with ARDS.

Source: Mammen, 2020 (Meduri, 2007; Steinberg 2006) |

Secondary infections

|

low GRADE |

Treatment with corticosteroids (Methylprednisolone) may result in lower numbers of infections compared to no treatment with corticosteroids in mechanical ventilated patients with ARDS.

Source: Mammen, 2020 (Meduri, 2007; Steinberg 2006) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Summary of literature

Description of studies

Mammen (2020) performed a meta-analysis regarding the efficacy of treatment with corticosteroids versus placebo or standard treatment (no glucocorticoid use) in patients with ARDS receiving mechanical ventilation. A systematic search was performed in February 2020 using MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and CINHAL. Participants were patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome of any cause. Age of participants was not specified, but most patients were over 50 years old. A total of seven RCTs was included. Some studies were assessed as low risk of bias (Meduri, 2007; Steinberg, 2006; Tongyo, 2016; Villar, 2020 (for mortality)) and some as high risk of bias (Liu, 2012; Rezk, 2013; Villar, 2020; Zhao, 2014). Sensitivity analyses were performed for different corticosteroids and by excluding studies with high risk of bias. Results of sensitivity analysis by excluding studies with high risk of bias were robust and consistent. Six RCTs (Liu, 2012; Meduri, 2007; Rezk, 2013; Steinberg, 2006; Tongyoo, 2016; Villar, 2020) were included in the current review. One RCT (Zhao, 2014) did not fulfill the inclusion criteria of the current review and was excluded (reasons for exclusion are noted in the evidence table).

Meduri (2018) performed additional analysis to 28-day data of Steinberg (2006), being included in the review of Mammen (2020). In this study, 180 patients were randomised in an intervention group receiving methylprednisolone and a control group receiving placebo treatment. The risk of bias was unclear, as not all aspects of the used method were reported. There might be risk of bias due to allocation, lack of blinding and selective outcome reporting. However, Mammen (2020) assessed the study of Steinberg (2006) as low risk of bias.

Table 1 shows brief characteristics of RCTs included in the current summary of literature.

Tabel 1: Characteristics of included RCTs

|

Study |

Start of treatment since diagnosis ARDS |

Type and dose of steroid |

Duration and phase-out schedule |

ARDS etiology |

Remarks |

|

Liu 2006 |

<72 hrs. |

Hydrocortison, 3 times a day 100mg |

Duration: 7 days no phase out schedule |

Unclear |

Unknown whether lung protective ventilation.

|

|

Meduri 2006 |

<72 hrs. |

Methylprednisolon 1mg/kg day 1-14 |

Duration: 28 days Phase out schedule: 0,5mg/kg day 15-21 0,25mg/kg day 22-25 0,125mg/kg day 26-28 |

75% sepsis and pneumonia |

Not all lung protective ventilation, switch in beginning of inclusion to lung protective ventilation |

|

Steinberg 2006 |

>7 days |

Methylprednisolon 0,5mg/kg 4 times a day 1-14 |

Duration: 28 days Phase out schedule: 0,5mg/kg 2times a day 15-21 Tapering day 22-28 |

Differs: Trauma, sepsis, pneumonia |

Lung protective ventilation if inclusion after 2000 |

|

Rezk 2013 |

<48 hrs. |

Methylprednisolon 1mg/kg day 1-14 |

Duration 28 days Phase out schedule 0,5mg/kg day 15-21 0,25mg/kg day 22-25 0,125mg/kg day 26-28 |

Unclear |

Unclear if ventilation was lung protective |

|

Tongyoo 2016 |

Day 1 |

Hydrocortison 4times per day 50mg |

Duration: 7 days in total |

severe sepsis/septic shock |

PaO2/FiO2 <300 mmHg |

|

Meduri 2018 |

<6 days |

Methylprednisolon 1mg/kg day 1-14 |

Duration: 28 days Phase out schedule: 0,5mg/kg day 15-21 0,25mg/kg day 22-25 0,125mg/kg day 26-28 |

Unclear |

Unclear if ventilation was lung protective. Start tapering earlier if extubation <14 day. |

|

|

>7 days |

Methylprednisolon 2mg/kg day 1-14 |

Duration 31 days Phase out schedule: 1mg/kg day 15-21 0,5mg/kg day 22-25 0,25mg/kg day 26-28 0,125mg/kg day 29-31 |

Unclear |

|

|

Villar 2020

|

24-30 hrs. |

Dexamethason 20mg day 1-5 |

Duration 10 days Phase out schedule: 10mg D6-10 |

75% sepsis and pneumonia |

No placebo (comparison with usual care) Stop steroid in case of extubation |

PaO2/FiO2 ratio <200 mmHg unless otherwise stated.

Results

28-day mortality

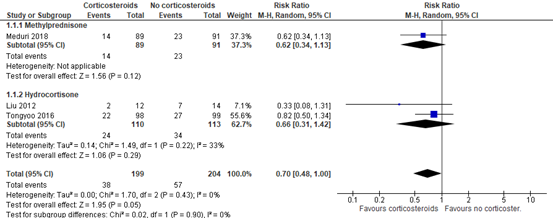

Meduri (2018) and two RCTs (Liu, 2020; Tongyoo, 2016) included in Mammen (2020) reported 28-day mortality in mechanical ventilated patients. A total of 38 out of 199 (19%) patients treated with corticosteroids died compared to 57 out of 204 (27.9%) patients in the control group (RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.48 to 1.00, see figure 1). This is a clinically relevant difference in favour of treatment with corticosteroids. Note that differences were also considered as clinically relevant for each individual agent (Methylprednisolone RR 0.62, 95%CI 0.34 to 1.13; Hydrocortisone RR 0.66, 95%CI 0.31 to 1.42).

Figure 1: meta-analysis of 28-day mortality

60-day Mortality

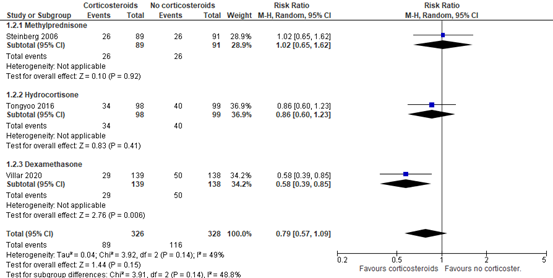

Three RCTs (Steinberg, 2006; Tongyoo, 2016; Villar, 2020) included in Mammen (2020) reported 60-day mortality in mechanical ventilated patients. A total of 89 out of 326 patients (27.3%) treated with corticosteroids died compared to 116 out of 328 (35.4%) patients in the control group (RR 0.79; 95%CI 0.57 to 1.09, see figure 2). This is a clinically relevant difference in favour of treatment with corticosteroids.

Note that effects differed per agent. Hydrocortisone (RR 0.86; 95%CI 0.60 to 1.23) and Dexamethasone (RR 0.58; 95%CI 0.39 to 0.85) did show clinically relevant effects, but Methylprednisolone (RR 1.02; 95%CI 0.65 to 1.62) did not.

Figure 2: meta-analysis of 60-day mortality

Hospital mortality

One RCT (Villar, 2020) included in Mammen (2020) reported ICU- mortality in mechanical ventilated patients. A total of 33 out of 139 (23.7%) patients died in the hospital compared to 50 out of 138 patients (36.2%) in the control group (RR 0.66; 95% CI 0.45 to 0.95). This is a clinically relevant difference in favour of treatment with corticosteroids (Dexamethasone).

Quality of life

No studies reporting quality of life and meeting the inclusion criteria were found.

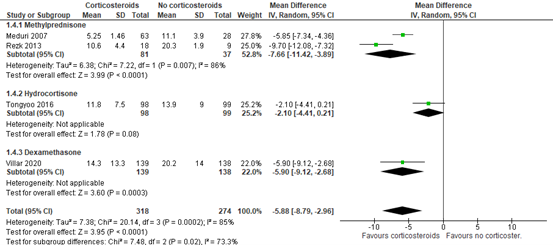

Duration of ventilation

Four RCTs (Meduri, 2007; Rezk, 2013; Tongyoo, 2016; Villar, 2020) included in Mammen (2020) reported duration of mechanical ventilation. The duration of mechanical ventilation was shorter in patients treated with corticosteroids compared to the control group (MD -5.88; 95% CI-8.79 to -2.96 days, figure 3). This is a clinically relevant difference in favour of treatment with corticosteroids. Note that differences were also considered as clinically relevant for each individual agent (Methylprednisolone MD -7.66, 95%CI -11.42 to -3.89; Hydrocortisone MD -2.10, 95%CI -4.41 to 0.21; Dexamethasone MD -5.90, 95%CI -9.12 to -2.68).

Figure 3: meta-analysis of duration of ventilation (data from Mammen, 2020)

Length of stay

Although not reported in the systematic review of Mammen (2020), Meduri (2007) reported length of ICU-stay and length of hospital-stay. The median ICU stay in patients treated with corticosteroids was 7 days (IQR 6 to 12) versus 14.5 days (IQR 9 to 20.5) in the control group. The median length of hospital stay was 13 days (IQR 8 to 21) versus 14.5 days (IQR 9 to 20.5) in the control group. These are clinically relevant differences in favour of treatment with corticosteroids (Methylprednisolone).

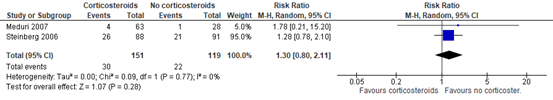

ICU-acquired weakness

Two RCTs (Meduri, 2007; Steinberg, 2006) included in Mammen (2020) reported neuromuscular weakness. A total of 30 out of 151 (19.9%) patients treated with corticosteroids (Methylprednisolone) developed neuromuscular weakness compared to 22 out of 119 (18.5%) patients in the control group (RR 1.30; 95% CI 0.80 to 2.11). This is a clinically relevant difference in favour of the control group.

Figure 4: meta-analysis of muscular weakness (Mammen, 2020)

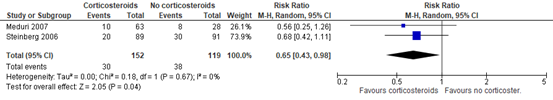

Secondary infections

Although not reported in Mammen (2020), Steinberg (2006) and Meduri (2007) reported the number of patients with infections. A total of 30 out of 152 (19.7%) treated with corticosteroids had secondary infections compared to 38 out of 119 (31.9%) patients in the control group (RR 0.65; 95%CI 0.43 to 0.98). This difference is clinically relevant in favour of treatment with corticosteroids (Methylprednisone).

Figure 5: meta-analysis of number of patients with infections

Level of evidence of the literature

28- day mortality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 28-day mortality started at high and was downgraded to low level, because of small number of events and confidence intervals crossing the threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, two levels).

60-day mortality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 60-day mortality started at high and was downgraded to low level, because of small number of events and confidence intervals crossing the threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, two levels).

In-hospital mortality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hospital- mortality started at high and was downgraded to low level, because of small number of events and confidence intervals crossing the threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, two levels).

Quality of life

Level of evidence could not be graded as no studies reporting quality of life and meeting the inclusion criteria were found.

Duration of mechanical ventilation

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure, duration of mechanical ventilation started at high and was downgraded to low level for Hydrocortisone because of small number of patients and confidence intervals crossing the threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, two levels) and downgraded to very low level for Methylprednisone and Dexamethasone because of lack of blinding (risk of bias, one level) and small number of patients (imprecision, two levels).

Length of stay

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure length of stay started at high and was downgraded to low level, because only one study with small number of participants was included and confidence interval of difference was not reported (imprecision, two levels).

ICU-acquired weakness (neuromuscular weakness)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neuromuscular weakness started at high and was downgraded to low level, because of small numbers of events and confidence intervals crossing the threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, two levels).

Secondary infections

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure secondary infections started at high and was downgraded to low level, because of small number of events and confidence interval crossing the threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision, two levels).

Zoeken en selecteren

Search and select

The working group performed a systematic review of the literature regarding the following question: What is the (in)effectivity of treatment with corticosteroids compared to no or other corticosteroids in mechanical ventilated patients with ARDS.

P: mechanical ventilated (invasive, without ECLS) patients with ARDS (according to Berlin or AECC criteria)

I: treatment with corticosteroids (methylprednisolone, prednisolone, dexamethasone, hydrocortisone, prednisone)

C: placebo, no or other corticosteroids (methylprednisolone, prednisolone, dexamethasone, hydrocortisone, prednisone), other dose or other timing of the intervention in relation the start of mechanical ventilation

O: mortality, quality of life, duration of mechanical ventilation, length of stay, ICU-acquired weakness, secondary infections (aspergillus, re-activation of CMV or HSV)

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered mortality as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and Quality of life, duration of ventilation, length of stay, ICU-acquired weakness and secondary infections as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

Mortality: 28-day mortality, 60-day mortality, in-hospital mortality

Quality of life: measured with validated questionnaires

Duration of ventilation: according to definitions in studies

Length of stay: according to definitions in studies

ICU-acquired weakness: according to definitions in studies

Secondary infections; aspergillus, re-activation of CMV or HSV

The working group defined the following values as a minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

Mortality:0.95≥RR≥1.05

Quality of life: MD>10% (maximum score validated questionnaire)

Duration of mechanical ventilation: MD ≥ 1 day

Length of stay: MD ≥ 1 day

ICU-acquired weakness: 0.91≥RR≥1.10

Secondary infections: 0.91≥RR≥1.10

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until December 7, 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 1245 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review published in or after 2016 and including RCTs published after the year 2000;

- mechanical ventilated patients with ARDS were included;

- studies focusing on ARDS patients with COVID-19 were excluded;

- treatment with corticosteroids was compared with placebo, no or other use of corticosteroids (corticosteroids were defined as methylprednisolone, prednisolone, dexamethasone, hydrocortisone, prednisone);

- effects on mortality, quality of life, duration of mechanical ventilation, length of stay, ICU-acquired weakness or secondary infections were considered as an outcome measure.

26 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 25 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and one study (Mammen, 2020) was included. Note that Sun (2019) was excluded because the review did not report additional RCTs to Mammen (2020) meeting the inclusion criteria of the current review. However, because Mammen (2020) used more strict inclusion criteria for study selection, RCTs published after the search date of Sun (2019) that do meet the inclusion criteria of the current review might be excluded in Mammen (2020).

To find relevant RCTs that were published after the search date of Sun (2019), an additional selection was performed. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Randomized controlled trial;

- Published after May 2017;

- mechanical ventilated patients with ARDS were included;

- studies focusing on ARDS patients with COVID-19 were excluded;

- treatment with corticosteroids was compared with placebo, no or other use of corticosteroids (corticosteroids were defined as methylprednisolone, prednisolone, dexamethasone, hydrocortisone, prednisone);

- effects on mortality, quality of life, duration of mechanical ventilation, length of stay, ICU-acquired weakness or secondary infections were considered as an outcome measure.

Eleven studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, ten studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and one additional study was included.

Results

In total, one systematic review and one additional RCT were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Czock, D., Keller, F., Rasche, F.M., Haussler, U. (2005). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of systemically administered glucocorticoids. Clinical Pharmacokinet., 44(1): 61-98.

- Liu, L., Li, J., Huang, Y. Z., Liu, S. Q., Yang, C. S., Guo, F. M., ... & Yang, Y. (2012). The effect of stress dose glucocorticoid on patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome combined with critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency. Zhonghua nei ke za zhi, 51(8), 599-603.

- Mammen, M. J., Aryal, K., Alhazzani, W., & Alexander, P. E. (2020). Corticosteroids for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Polish archives of internal medicine.

- Meduri, G. U., Bridges, L., Siemieniuk, R. A., & Kocak, M. (2018). An exploratory reanalysis of the randomized trial on efficacy of corticosteroids as rescue therapy for the late phase of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Critical care medicine, 46(6), 884-891.

- Meduri, G. U., Golden, E., Freire, A. X., Taylor, E., Zaman, M., Carson, S. J., ... & Umberger, R. (2007). Methylprednisolone infusion in early severe ARDS: results of a randomized controlled trial. Chest, 131(4), 954-963.

- Rezk, N. A., & Ibrahim, A. M. (2013). Effects of methyl prednisolone in early ARDS. Egyptian Journal of Chest Diseases and Tuberculosis, 62(1), 167-172.

- Steinberg e.a.; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network. (2006). Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids for persistent acute respiratory distress syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 354(16), 1671-1684.

- Sun, S., Liu, D., Zhang, H., Zhang, X., & Wan, B. (2019). Effect of different doses and time?courses of corticosteroid treatment in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: A meta?analysis. Experimental and therapeutic medicine, 18(6), 4637-4644.

- Tongyoo, S., Permpikul, C., Mongkolpun, W., Vattanavanit, V., Udompanturak, S., Kocak, M., & Meduri, G. U. (2016). Hydrocortisone treatment in early sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: results of a randomized controlled trial. Critical Care, 20(1), 1-11.

- Villar, J., Ferrando, C., Martínez, D., Ambrós, A., Muñoz, T., Soler, J. A., ... & Soro, M. (2020). Dexamethasone treatment for the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8(3), 267-276.

- Zhao, W. B., Sheng-xia, W. A. N., De-fang, G. U., & Bin, S. H. I. (2014). Therapeutic effect of glucocorticoid inhalation for pulmonary fibrosis in ARDS patients. Jie Fang Jun Yi Xue Za Zhi, 39(9), 741.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Mammen, 2020

[individual study characteristics deduced from [1st author, year of publication ]]

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to February 2020

A: Steinberg, 2006 B: Meduri, 2007 C: Liu, 2013 D: Rezk, 2013 E: Zhao, 2014 F: Tongyoo, 2016 G: Villar, 2020

Study design: All: Parrelel group RCTs

Setting and Country: A: multicenter, united states B: multicenter, united states C: single-center, China D: single-center, Kuweit E: single-center, China F: single-center, Thailand G: multicenter, Spain

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: A: Funding: non-profit, CoI: not reported in review B: Funding: non-profit, CoI: not reported in review C: Funding: non-profit, CoI: not reported in review D: Funding: non-profit, CoI: not reported in review E: Funding: uncertain, CoI: not reported in review/ F: Funding: non-profit, CoI: not reported in review G: Funding: non-profit, CoI: not reported in review

|

Inclusion criteria SR: - parallel-group RCTs - ARDS of any course - compared corticosteroid therapy versus - reporting at least one of the following outcomes: all-cause mortality, duration of mechanical ventilation, length of hospital stay, ventilator-free days, adverse effects and complications of corticosteroid use

Exclusion criteria SR:

7 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N (I, C) A: 108 (89,91) B: C: 26 (12,14) D: 27 (18,9) E: 53 (24,19) F: 197 (98,99) G: 277 (139,138)

Age

Sex: A: 54.4% Male B: 51.6% Male C: 73% Male D: 85.2% Male E: Unclear F: 51.5% Male G: 68.9% Male

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention:

A: After at least 7 days after the diagnosis of ARDS Intravenous methylprednisolone sodium succinate (methylprednisolone) diluted in 50 ml of 5% dextrose in water. A single dose of 2 mg of methylprednisolone per 1 kg of predicted body weight was followed by a dose of 0.5 mg per 1 kg of predicted body weight every 6 hrs for 14 days, a dose of 0.5 mg per 1 kg of predicted body weight every 12 hrs for 7 days, and then the dose was tapered. The study drug was tapered over 4 days if 21 days of treatment had been completed and the patient was unable to breathe without assistance for 48 hrs. Tapering occurred over a 2‑day period if disseminated fungal infection or septic shock developed or the patient could breathe without assistance for 48 hrs. B: Within 72 hrs after the diagnosis of ARDS Corticosteroid methylprednisolone; a loading dose of 1 mg/kg, then infusion of 1 mg/kg/d from day 1 to day 14; 0.5 mg/kg/d on days 15 to 21; 0.25 mg/kg/d on days 22 to 25; then 0.125 mg/kg/d from days 26 to 28 (all administered in 240 ml of normal saline infused daily at a rate of 10 ml/h) C: Within 72 hrs after the diagnosis of ARDS: “hydrocortisone 100 mg IV 3 times a day for 7 days” D: Within 48 hrs after the diagnosis of ARDS Corticosteroid: methylprednisolone; a loading dose of 1 mg/kg, then infusion of 1 mg/kg/d from day 1 to day 14; 0.5 mg/kg/d on days 15 to 21; 0.25 mg/kg/d on days 22 to 25; then 0.125 mg/kg/d from day 26 to day 28 E: Within uncertain time after the diagnosis of ARDS “inhaled budesonide 2 mg twice a day for 12 days alongside ARDS management algorithm according to the 2006 Chinese Society for Critical Care Medicine Guidelines” F: Within 12 hrs after the diagnosis of ARDS Hydrocortisone given daily as an intravenous bolus (50 mg in 10 ml of normal saline) every 6 hrs for 7 days G: Within 7 days after the onset of ARDS: Dexamethasone at a dose of 20 mg administered intravenously once daily from day 1 to day 5, reduced to a dose of 10 mg once daily from day 6 to day 10

|

Describe control:

A: placebo (50 ml of 5% dextrose in water), 50 ml of 5% dextrose in water at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg B: 240 ml of normal saline administered daily as infusion at a rate of 10 ml/h C: “normal saline; 0.9% IV 100 mg 3 times a day for 7 days” D: normal saline administered in the same manner as methylprednisolone E: “ARDS management algorithm according to the 2006 Chinese Society for Critical Care Medicine Guidelines” F: a comparable volume of normal saline on the same time schedule G: continued routine Intensive Care; Patients in both groups were ventilated with lung‑protective mechanical ventilation.

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: Patients followed until they died; discharged home when started to breathe without assistance or on day 180, whichever came first. B: Up to 28 days C: Unclear D: Up to 28 days E: Unclear F: 60 days G: 60 days

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available?

The loss to follow‑up was rare: 6 trials (85.7%) had a near‑ complete follow‑up with loss that was deemed not biasing, and only 1 study had the attrition rate greater than 5%. Worst‑case and best‑case plausible modeling assumptions about the outcomes of patients lost to follow‑up were not needed.

|

All cause mortality A: 60-day mortality B: ICU-mortality C: 28-day mortality D: 14-day mortality E: Unclear F: 60-day mortality (28- day mortality also available in individual article) G: hospital mortality (ICU mortality and 60-day mortality also available in individual article)

Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: A: 1.02 (0.65 to 1.62) B: 0,56 (0.30 to 1.03) C: 0.33 (0.08 to 1.31) D: 0.08 (0.00 to 1.32) E: 0.84 (0.43 to 1.61) F: 0.86 (0.60 to 1.23) G: 0.66 (0.45 to 0.95)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.75 [95% CI 0.59 to0.95] favoring corticosteroid treatment Heterogeneity (I2): 22%x ` Sub-analyasis: Methylprednisolone (A,B,D) Hydrocortisone (C,F) RR (95%CI): 0.68 (0.30 to 1.52) Dexamethason (G) Inhaled budenoside (E) RR(95%CI): Individuele studie (A): RR(95%CI) 0.84 (0.43 to 1.61)

Duration of mechanical ventilation Mean difference (95%CI) B: -5.85 ( -7.34 to -4.36) D: -9.70 ( -12.08 to 7.32) E: -1.10 (-3.59 to 1.39) F: -2.10 (-4.45 to 0.25) G: -5.90 (-9.12 to -2.68)

Pooled effect (random effects model): MD: -4.93 [95% CI -7.81 to -2.06] favoring corticosteroid treatment Heterogeneity (I2): 87%

Length of stay: not reported

Ventilator-free days up to day 28 Mean difference (95%CI) A: 4.40 (1.78 to 7.02) B: 7.80 (3.27 to 12.33) C:1.10 (-7.61 to 9.81) F: 2.30 (-0.45 to 5.05) G: 4.80 (2.57 to 7.03)

Pooled effect (random effects model): MD:4.28 [95% CI 2.67 to 5.88] favoring control group Heterogeneity (I2): 21%

Infections The data on infections, where reported, were unclear and could not be pooled for meaningful interpretation.

Adverse events: hyperglecemia RR (95%CI) B: 1.11 (0.81 to 1.53) F: 1.19 ( 1.01 to 1.41) G: 1.07 (0.93 to 1.24)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR:1.12 [95% CI 1.01 to 1.24] favoring control group Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Adverse events: Neuromuscular weakness RR (95%CI) A:1.28 (0.78 to 2.10) B 1.78 ( 0.21 to 15.20)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR:1.30 [95% CI 0.80 to 2.11] favoring control group Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

|

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion: the early use of systemic corticosteroids in patients with ARDS may improve mortality, shorten the duration of mechanical ventilation

Level of evidence: GRADE (per comparison and outcome measure) including reasons for down/upgrading:

All-cause mortality: Moderatie (Optimal information size (n=300 events for a dichotomous outcome) was not reached (n=270). Therefore, we downgraded one level; studies, therefore, we did not rate down)

mechanical ventilation duration: low Sensitivity analysis reveals results were robust and consistent with the removal of high-risk studies, therefore, we did not rate down; High I2 and significant Cochran Q chi-square test warranted a double downgrade (point estimates varied widely. Sensitivity analysis with removal of high risk of bias studies showed reductions of heterogeneity to a moderate-high level but did not explain the heterogeneity; The Optimal information size is reached and the both boundaries of the 95% CI are on the side of benefit. Optimal information size is met. However, the number of studies was low (driven largely by Villar (2020) and we judged that the 95% CI is wide enough to warrant a downgrade for imprecision.

ventilator free-days: moderate studies, therefore, we did not rate down; . High I2 and significant Cochran Q chi-square test warranted a double downgrade (point estimates varied widely. Sensitivity analysis with removal of high risk of bias studies showed reductions of heterogeneity to a moderate-high level but did not explain the heterogeneity.

Hyperglecemia: moderate level.

Neuromuscular weakness: very low Due to the low number of studies and sub-optimal reporting, we decided to downgrade one level. ; The confidence interval crossed harms and benefits; Optimal information size not reached and based on a small number of studies and small number of events

Sensitivity analyses: All cause mortality: We conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding studies at high risk of bias.16,17,20 The mortality benefit associated with the use of corticosteroids was robust and consistent (RR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.61–0.98; P = 0.03).

Duration of mechanical ventilation: We performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding studies at high risk of bias,4,16,20 and the results were robust and consistent (MD, –4.09 days; 95% CI, –7.76 to –0.42; P = 0.03; I2 = 86%).

Ventilator-free days: We conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding a study at high risk of bias,4,17 and found the pooled estimate to be robust and consistent with an MD increase of 4.37 (95% CI, 1.69–7.04; P = 0.001).

Remarks: Zhao 2014 and Liu 2013: it is unclear wheather all patients received mechanical ventilation as not stated in abstracts. Note that outcome related to mechanical ventilation was included. Articles are written in Chinese.

Zhao 2014 will be excluded from the literature analyses as the intervention did not meet the inclusion criteria (budesonide)

Additional individual study data: Meduri 2007: Median (IQR), days Length of ICU stay: I: 7 (6-12), n=63 C: 14.5 (7-20.5), n=28 Length of hospital stay: I: 13.0 (8-21), n=63 C: 20.5 (10.5-40.5), n=28 P=0.09 Number of new infections (7 days): I: 10 of 63 (15.9%) C: 8 of 28 (28.6%)

Tongyoo 2015: 28-day mortality: C: 27 of 99

Steinberg 2006: Number of patients with serious infections: I: 20 of 89 C: 30 of 91

Villar 2020: 60-day mortality: I: 29 of 139 C: 50 of 138 ICU-mortality: I: 26 of 139 C: 43 of 138

|

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy – otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Meduri, 2018 |

Type of study: RCT (additional analyses on data of Steinberg 2006)

Setting and country: Multicenter. Country not reported (see Steinberg 2006 in Mammen 2020)

Funding and conflicts of interest: the resources and use of facilities at the Memphis Veterans Administration Medical Center. He disclosed off-label product use of prolonged methylprednisolone treatment in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Dr. Siemieniuk disclosed off-label product use of corticosteroids for ARDS. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Not reported, see Steinberg 2006 in Mammen 2020)

Exclusion criteria: Not reported, see Steinberg 2006 in Mammen 2020)

N total at baseline: Intervention: 89 Control: 91

Important prognostic factors2: Not reported, see Steinberg 2006 in Mammen 2020)

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported, see Steinberg 2006 in Mammen 2020)

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

methylprednisolone (2 mg/Kg/day)

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Placebo |

Length of follow-up: 28-days

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

28-day mortality: I: 14 (15.7%) C: 23 (25.3%) |

Re-analysis from Steinberg 2006, reported in SR of Mammen, 2020. 28-day mortality was not reported in Steinberg 2006 |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors [(potential) confounders]

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Meduri, 2018 |

From Steinberg 2006: Patients were randomly assigned with the use of permuted blocks to receive either intravenous methylprednisolone sodium succinate (methylprednisolone) diluted in 50 ml of 5 percent dextrose in water or placebo (50 ml of 5 percent dextrose in water), stratified according to hospital |

Unclear (not reported in Steinberg 2006) |

Unclear (not reported in Steinberg 2006) |

Unclear (not reported in Steinberg 2006) |

Unclear (not reported in Steinberg 2006) |

Likely (explorative analysis, additional to original study) |

unlikely |

unlikely |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules..

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Mamman, 2020 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Adhikari, 2004 |

Updated by Lewis 2019 |

|

Annane, 2017 |

More recent review available, does not add studies meeting inclusion criteria |

|

Annane, 2016 |

Narrative review |

|

Bourenne, 2018 |

Narrative review |

|

Briegel, 2017 |

Narrative review |

|

Claesson, 2016 |

Did not report search and study characteristics |

|

Duan, 2017 |

Wrong design (no RCT) |

|

Edel, 2020 |

Broad review, including only one ARDS-study |

|

Feldman, 2016 |

Appreciation of review |

|

Festic, 2017 |

P: patients at risk for ARDS |

|

Fujishima, 2020 |

Wrong design (no RCT) |

|

Hasan, 2020 |

Covid-19 study |

|

Hashimoto, 2017 |

More recent review available, does not add studies meeting inclusion criteria |

|

Hussain, 2018 |

Narrative review |

|

Kido, 2018 |

Wrong design (no RCT) |

|

Lewis, 2019 |

Update by Mamman 2020 |

|

Matthay, 2017 |

Narrative review |

|

Meduri, 2020 |

Did not report systematic search |

|

Meduri, 2018 |

Did not report search, quality and study characteritics |

|

Meduri, 2016 |

Did not report systematic search |

|

Meduri, 2016 |

Narrative review |

|

Silva, 2020 |

Narrative review |

|

Singh, 2020 |

Covid-19 study |

|

Sobhy, 2020 |

I: saline |

|

Sun, 2019 |

No additional studies included compared with Mamman (2020), that met inclusion criteria |

|

Tomazini, 2020 |

Covid-19 study |

|

Tsai, 2020 |

Wrong design (no RCT) |

|

Veronese, 2020 |

Covid-19 study |

|

Villar, 2020 |

Already included in Mammen, 2020 |

|

Yang, 2017 |

More recent review available, does not add studies meeting inclusion criteria |

|

Yang, 2020 |

Covid-19 study |

|

Ye, 2020 |

Covid-19 study |

|

Zayed, 2020 |

P: respiratory failure secondary to ARDS |

|

Zhao, 2019 |

More recent review available, does not add studies meeting inclusion criteria |

|

Zhou, 2020 |

P: influenza-related pneumonia |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 05-03-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financierder heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met ARDS.

Werkgroep

- Dr. H. Endeman, internist-intensivist, NVIC

- Dr. R.M. Determann, internist-intensivist, NIV

- Drs. R. Pauw, longarts-intensivist, NVALT

- Drs. M. Samuels, anesthesioloog-intensivist, NVA

- Dr. A.H. Jonkman, klinisch technoloog, NVvTG

- J.W.M. Snoep, ventilation practitioner/IC-verpleegkundige, V&VN

- Drs. M.A.E.A. Brackel, patiëntvertegenwoordiger (tot 1-1-2022 bestuurslid FCIC/Voorzitter IC Connect), FCIC/IC Connect

Meelezers:

- Drs. F.Z. Ramjankhan, Cardio-thoracaal chirurg, NVT

- Dr. R.R.M. Vogels, Radioloog, NVvR

- Drs. R. ter Wee, Klinisch fysicus, NVKF

Met ondersteuning van:

- Drs. I. van Dusseldorp, literatuurspecialist, Kennisinsitituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. S.N. Hofstede, senior-adviseur, Kennisinsitituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. J.C. Maas, adviseur, Kennisinsitituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Endeman |

Internist-intensivist, opleider Intensive Care, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Secretaris GIC, lid sectie IC NIV aanpassing juli 2022:

|

Travelgrant/speakers fee voor IC-symposium Kenya augustus 2018 door GETINGE

Advanced mechanical ventilation is een speerpunt van wetenschappelijk onderzoek van de Intensive Care van het Erasmus MC aanpassing juli 2022: gesponsord door Ventinova. Dat is een beademingsmachine. Open Lung Concept 2.0: Flow Controlled Ventilation |

Bij modules die specifiek gaan over apparatuur ontwikkeld door GETINGE: Wanneer dit onderwerp geprioriteerd wordt zal een vice-voorzitter worden aangewezen en werkgroeplid niet meebeslissen over dit onderwerp |

|

Pauw |

Intensivist longarts Martini Ziekenhuis Groningen |

Secretaris sectie IC NVALT (onbetaald), instructeur FCCS-cursus NVIC (vergoeding per gegeven cursus, gemiddeld 1-2x/jaar) |

Maart 2023: Spreker congres pulmonologie vogelvlucht: pulmonary year in review m.b.t. IC-onderwerpen |

Geen |

|

Jonkman |

* Technisch geneeskundige (klinisch technoloog), PhD kandidaat en research manager, afdeling Intensive Care Volwassenen, Amsterdam UMC, locatie Vumc (t/m 2021) * Research fellow dept. Critical Care Medicine, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Canada (gedetacheerd vanuit VUmc voor periode jan-dec 2020)

aanpassing juli 2022: |

Bestuurslid Nederlandse Vereniging voor Technische Geneeskunde (NVvTG), vice-voorzitter t/m mei 2021 |

Adviesfunctie (consultancy) bij Liberate Medical LLC (Kentucky, USA), een medical device company dat een niet-invasieve elektrische spierstimulator ontwikkelt voor het trainen van de expiratiespieren (buikspieren) tijdens kunstmatige beademing. Betaald consultancy werk, ongeveer 1-2 dagdelen per jaar (2018 -2020)

Deelname aan diverse nationale en internationale investigator-initiated wetenschappelijke onderzoeken naar gepersonaliseerde kunstmatige beademing middels advanced respiratory monitoring (o.a. ademspierfunctie en electrische impedantie tomografie) bij de IC-patiënt. Deels in het kader van voormalig promotieonderzoek Waaronder: * lid stuurgroep CAVIARDS-trial (Careful Ventilation in (COVID-19-induced) Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, NCT03963622), internationale investigator-initiated studie naar gepersonaliseerde beademingsstrategie bij ARDS, geen persoonlijke financiële vergoeding |

Onderwerpen niet-invasieve elektrische spierstimulatie en gepersonaliseerde kunstmatige beademing middels advanced respiratory monitoring worden niet behandeld in de richtijn. Mochten deze toch worden toegevoegd, dan zal werkgroep lid niet als auteur van deze specifieke modules worden aangesteld. |

|

Samuels |

Anesthesioloog – Intensivist, te Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland

aanpassing Juli 2022: Anesthesioloog-lntensivist, te HMC |

* MICU intensivist – betaald * FCCS teacher – betaald * bestuurslid sectie IC NVA

aanpassing Juli 2022: Waarnemer als lntensivist op de IC (betaald) Voorzitter sectie IC, NVA (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

De Graaff |

Intensivist – Internist, St Antonius ziekenhuis Nieuwegein, fulltime |

Bestuurslid Stichting NICE, vrijwilligerswerk |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Determann |

Intensivist OLVG |

Gastdocent Amstelacademie (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Brackel-Welten |

* Voorzitter patiëntenorganisatie IC Connect, onbetaald, tot 1-1-2022 * Bestuurslid Stichting Family en patient centered Intensive Care (Stichting FCIC), onbetaald, tot 1-1-2022 * Jeugdarts KNMG, niet praktiserend * voormalig IC-patiënte |

Geen |

Voorzitterschap IC Connect, bestuurslid Stichting FCIC, tot 1-1-2022 |

Geen |

|

Snoep |

* Ventilation Practitioner 25% * IC-verpleegkundige 75%

aanpassing juli 2022: Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum

|

Hamilton Medicai expert panel Netherlands, sinds 2022. Onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Ramjankhan |

Cardio-thoracaal chirurg UMCU |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Ter Wee |

Klinisch Fysicus in opleiding - Medisch Spectrum Twente |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Vogels |

*Radioloog met aandachtsgebied thoracale en abdominale radiologie * Fellow Thoraxradiologie

Maatschap Radiologie Oost Nederland (MRON) locatie MST Enschede

Toevoeging juli 2022: Radioloog met als aandachtsgebied thoracale en abdominale readiologie als maatschapslid bij MRON licatie ZGT Almelo/Hengelo |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Stichting FCIC, IC Connect en het Longfonds voor deelname aan de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie en deelname van een afgevaardigde van Stichting FCIC en IC Connect in de werkgroep. De resultaten van de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarsiatie zijn besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Stichting FCIC, IC Connect en het Longfonds. De eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Corticosteroïden |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en zal daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven.

|

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met ARDS. Tevens zijn IGJ, NFU, NHG, NVZ, Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, STZ, V&VN, NVIC, NVA, NIV, NVALT, NVvTG, NVVC, NVN, NVKF, Longfonds, FCIC/IC Connect en ventilation practitioners uitgenodigd om knelpunten aan te dragen via een enquête. Een overzicht hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties uit de werkgroep voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Grasselli G, Calfee CS, Camporota L, Poole D, Amato MBP, Antonelli M, Arabi YM, Baroncelli F, Beitler JR, Bellani G, Bellingan G, Blackwood B, Bos LDJ, Brochard L, Brodie D, Burns KEA, Combes A, D'Arrigo S, De Backer D, Demoule A, Einav S, Fan E, Ferguson ND, Frat JP, Gattinoni L, Guérin C, Herridge MS, Hodgson C, Hough CL, Jaber S, Juffermans NP, Karagiannidis C, Kesecioglu J, Kwizera A, Laffey JG, Mancebo J, Matthay MA, McAuley DF, Mercat A, Meyer NJ, Moss M, Munshi L, Myatra SN, Ng Gong M, Papazian L, Patel BK, Pellegrini M, Perner A, Pesenti A, Piquilloud L, Qiu H, Ranieri MV, Riviello E, Slutsky AS, Stapleton RD, Summers C, Thompson TB, Valente Barbas CS, Villar J, Ware LB, Weiss B, Zampieri FG, Azoulay E, Cecconi M; European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Taskforce on ARDS. ESICM guidelines on acute respiratory distress syndrome: definition, phenotyping and respiratory support strategies. Intensive Care Med. 2023 Jul;49(7):727-759. doi: 10.1007/s00134-023-07050-7. Epub 2023 Jun 16. PMID: 37326646; PMCID: PMC10354163.