Hoe herken je cognitieve stoornissen/ dementie bij patiënten van ≥70 jaar in de preoperatieve setting?

Uitgangsvraag

Hoe herken je cognitieve stoornissen/ dementie bij patiënten van ≥70 jaar in de preoperatieve setting?

Aanbeveling

Verricht bij voorkeur bij alle patiënten van ≥70 die een operatie zullen ondergaan met verwachte opnameduur ≥2 dagen preoperatief een cognitieve screeningtest. Gebruik bij voorkeur de MiniCOG, de 6-CIT is ook mogelijk.

Verwijs bij een afwijkende screeningstest, bekende cognitieve stoornissen zoals een diagnose mild cognitive impairment of dementie, of een delier in de voorgeschiedenis, naar een geriater of internist-ouderengeneeskunde voor een Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De kwaliteit van het bewijs uit de literatuur ten aanzien van de voorspellende waarde van cognitieve stoornissen voor ongunstige uitkomsten na chirurgie bij kwetsbare ouderen varieert van zeer laag tot laag. Dit geldt voor zowel de veel gebruikte uitkomstmaten mortaliteit en complicaties, maar ook voor andere uitkomstmaten zoals postoperatief delier, ontslag naar een verpleeghuis en duur van ziekenhuisverblijf. De belangrijkste reden voor de zeer lage kwaliteit van bewijs is het ontbreken van RCT’s, aangezien het niet mogelijk is om een chirurgische interventie te doen en te randomiseren op wel of geen cognitieve stoornissen. Daarom is het nu ook niet mogelijk om op basis van een RCT een uitspraak te doen over het causale effect van cognitieve stoornissen voor ongunstige uitkomsten. Dit is de belangrijkste reden waarom voor deze richtlijn geen recentere observationele studies zijn toegevoegd die na de systematic reviews zijn gepubliceerd. De kwaliteit van het bewijs wordt dus bepaald door observationele studies die zijn samengevat in 3 (semi-) recente systematic reviews.

Als tweede hebben de geïncludeerde studies een risico op vertekening, doordat niet altijd duidelijk is waarom bepaalde studies uitgesloten zijn van analyse. Het is echter onwaarschijnlijk dat hier belangenverstrengeling heeft plaatsgevonden bij de auteurs van onderliggende studies. Wat betreft de uitkomst van postoperatief delier is het onduidelijk of de meetmethode van de uitkomstmaat niet beïnvloed kan worden door de aanwezigheid of afwezigheid van de voorspellende factor cognitieve stoornissen.

Toch lijkt een associatie tussen cognitieve beperkingen enerzijds en een verhoogd risico op delier of overlijden anderzijds aannemelijk (Chen et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2014). De overall bewijskracht is laag te noemen. Echter, het is onwaarschijnlijk dat de mogelijk verstorende factoren zoals hierboven beschreven, zo'n grote invloed hebben gehad op de resultaten dat deze qua aan- of afwezigheid van een effect of qua richting van het effect niet representatief zijn voor de werkelijke onderliggende associatie. Voor de overige uitkomstmaten zoals opnameduur en ontslagbestemming werd er geen duidelijk richting van effect gezien, en is de bewijskracht zeer laag.

De werkgroep stelt op basis van praktijkervaring dat er aanwijzingen zijn voor een relatie tussen cognitieve stoornissen en ongunstige postoperatieve uitkomsten. Met name de relatie tussen preoperatief aanwezige cognitieve stoornissen en een postoperatief delier is op basis van klinische ervaring voor de werkgroepleden evident. Een delier is een ernstige postoperatieve complicatie die in een deel van de patiënten te voorkomen is en een verhoogd risico geeft op cognitieve stoornissen daarna. Bij patiënten die een niet-geplande heupoperatie ondergingen en een meervoudig delierpreventie interventieprogramma ontvingen gebaseerd op zeven beïnvloedbare risicodomeinen (oriëntatie, dehydratie, gehoor- en visusstoornissen, immobiliteit, omgevingsfactoren en medicatiemanagement) gevolgd door consultatie geriatrie, vond een vermindering in de incidentie van het delier plaats (RR 0,65; 95% BI 0,42-1,00), (Marcantonio et al., 2001, zie richtlijn Delier). Een systematische review liet in chirurgische patiënten een vermindering in de incidentie van het postoperatief delier zien als gevolg van een meervoudig delierpreventie programma (RR 0,53; 95% BI 0,41-0,69) (Ludloph, JAGS 2020). En de meest recente randomized controlled trial toonde een significante reductie van postoperatief delier bij niet-cardiale chirurgie na een meervoudig delierpreventie programma (RR 0,67; 95% BI 0,48 - 0,93) (Deeken, JAMA Surg 2021).

In Nederland zijn er op basis van bevolkingsonderzoek in 2021 naar schatting 290.000 mensen met dementie. De verwachting is dat door de vergrijzing dit aantal in de toekomst zal stijgen naar meer dan 500.000 in 2040 en ruim 620.000 in 2050 (RIVM, n.d.).

In een rapport van Alzheimer Nederland uit 2019 (van den Buuse, 2019) wordt beschreven dat er in de Nederlandse praktijk onvoldoende aandacht is voor dementie bij de ziekenhuisopname. Daarnaast is de herkenning van cognitieve stoornissen niet altijd voldoende. Een recente systematic review en meta-analyse (Kapoor et al., 2022) berekende een gepoolde prevalentie van 37% van niet herkende cognitieve stoornissen, en een prevalentie van 18% gediagnosticeerde cognitieve stoornissen in electieve niet-cardiale chirurgische patiënten van 60 jaar en ouder. In cardiale chirurgie patiënten was de prevalentie 26% van niet herkende cognitieve stoornissen. Wanneer gekeken werd naar subcategorieën van chirurgie, is de prevalentie van niet herkende cognitieve stoornissen met name hoog in vaatchirurgie patiënten (64%) en acute chirurgie patiënten (50%). De prevalentie van gediagnosticeerde dementie is daarentegen weer laag (ca. 5%) in patiënten die cataract chirurgie ondergaan (Goldacre et al., 2015; Kumar & Seet, 2016).

Behalve dementie komen ook milde cognitieve stoornissen vaak voor. De prevalentie van Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) bij mensen ouder dan 70 jaar geschat tussen de 5 en 18% (richtlijn MCI), waarbij de symptomen en klachten vaak subtiel zijn en alleen opgemerkt worden door naasten van de patiënt. Progressie van MCI naar dementie gebeurt bij ongeveer 50% van de mensen in een periode van 3 jaar (richtlijn MCI), maar kan niet voorspeld worden op dit moment (Evered et al., 2016).

Internationale richtlijnen rondom perioperatieve zorg bij ouderen

De internationale richtlijnen voor perioperatieve zorg bevelen aan om bij (kwetsbare) ouderen in de preoperatieve beoordelingsfase een screeningstool te gebruiken om cognitieve stoornissen te identificeren.

De Amerikaanse ‘Best practice guideline- Optimal Perioperative Mangement of the geriatric patient’ is in 2016 geschreven door de American College of Surgeons en de American Geriatrics Society. Deze richtlijn geeft als aanbeveling dat bij chirurgische patiënten een beoordeling van delierrisico factoren zou moeten plaatsvinden, namelijk van de risicofactoren leeftijd >65 jaar, chronische cognitieve stoornissen of dementie, slechte visus of gehoor, ernstige ziekte (bijvoorbeeld IC opname), en aanwezigheid van een infectie.

De ‘Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Evaluation and Management of Frailty Among Older Adults Undergoing Colorectal Surgery’, 2022, van de American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons beveelt bij kwetsbare ouderen aan dat preoperatief gescreend moet worden op cognitieve stoornissen. Daarbij wordt specifiek de MiniCOG genoemd (Culley et al., Montroni et al., J 2020).

De Royal College of Anesthesists (2023), Verenigd Koninkrijk, beschrijft in de richtlijn voor perioperatieve zorg, hoofdstuk 2 “Guidelines for the Provision of Anaesthesia Services for the Perioperative Care of Elective and Urgent Care Patients” dat patiënten preoperatief gescreend moeten worden op cognitieve stoornissen en dementie.

De Britse Association of Anaesthesists heeft een richtlijn geschreven voor de perioperatieve zorg voor mensen met dementie (White et al., 2019). In deze richtlijn wordt de aanbeveling gedaan dat in de preoperatieve setting cognitieve stoornissen geïdentificeerd zouden moeten worden. Een richtlijn van het Britse Center of Perioperative Care genaamd ‘Preoperative Assessment and Optimisation for Adult Surgery (2021) adviseert het gebruik van een screeningstool in combinatie met directe vragen om patiënten met cognitieve stoornissen en daarmee een verhoogd risico op delier te identificeren.

Een Italiaanse richtlijn ‘Perioperative Management of Elderly patients (PriME):

Recommendations from an Italian intersociety consensus’ (Aceto et al., 2020) geeft als aanbeveling dat preoperatief een cognitieve test moet worden uitgevoerd bij alle patiënten ouder dan 65 jaar.

Cognitieve screeningsinstrumenten in preoperatieve setting

Voor het uitvoeren van cognitieve screening in de preoperatieve setting wordt idealiter een instrument gebruikt dat weinig tijd kost, makkelijk in gebruik is, en valide en betrouwbaar is. Op basis van de search voor UV 1.1 werd gezocht naar de 6-CIT (BOMC) en de MiniCOG. Voor de MiniCOG werden drie studies niet in de meta-analyse meegenomen, omdat de inclusie leeftijd niet vanaf 70 jaar en ouder was, maar vanaf 65 jaar en ouder. Omdat de gemiddelde leeftijd wel boven de 70 jaar was, is de werkgroep van mening dat deze drie studies relevant zijn voor de richtlijn. In totaal is de MiniCOG dus onderzocht in 7 studies, in zowel electieve als acute setting, niet-cardiale chirurgie en orthopedische chirurgie, waarvan 6 studies een associatie aantoonden tussen afwijkende MiniCOG screening preoperatief met een postoperatief delier (Culley et al., 2017; Heng et al., 2016; Korc-Grodzicki et al., 2015; Tiwari et al., 2021; Weiss et al., 2022; Yajimi et al., 2022). Het voordeel van de MiniCOG ten opzichte van bijvoorbeeld de MMSE of de MOCA is dat de MiniCOG veel korter is en dus minder tijd kost. Voor de 6-CIT (of onder de eerdere naam BOMC) werden geen studies gevonden in de preoperatieve setting.

De 6-CIT wordt wel genoemd als optie in de CGA richtlijn voor cognitie screening in het algemeen, vanwege de pragmatische reden dat deze al gebruikt wordt in sommige ziekenhuizen. Concluderend beveelt de werkgroep dan ook aan om de MiniCOG te gebruiken voor preoperatieve cognitieve screening, of de 6-CIT als alternatief indien deze lokaal al is geïmplementeerd.

Het is belangrijk om te realiseren dat een afwijkende cognitieve screeningstest niet hetzelfde is als een diagnose ‘cognitieve stoornissen’ of een diagnose ‘dementie’. Daarvoor is een hetero-anamnese en vaak ook aanvullend onderzoek nodig (zie richtlijn Dementie).

Migrantenpopulatie

De subgroep van oudere migranten verdient extra aandacht in de preoperatieve setting. Het gebruik van een cognitief screeningsinstrument wordt namelijk bemoeilijkt als er een taalbarrière is. Vaak zal familie of andere naasten van de patiënt dan optreden als tolk. Ondanks deze beperking is de werkgroep van mening dat screening bij oudere migranten wel moet plaatsvinden. Dementie komt verhoudingsgewijs namelijk vaker voor bij migrantenouderen. Dit komt onder andere door een combinatie van risicofactoren die vaker voorkomen bij migrantenouderen (RIVM, n.d.).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

In de literatuur zijn geen waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten ten aanzien van cognitieve screening preoperatief beschreven.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Aangezien het afnemen van een screeningstest doorgaans 5 minuten duurt, is er een te verwaarlozen middelenbeslag. Een implementatie studie waarbij de Mini-COG in de preoperatieve setting werd ingezet, toonde een percentage afwijkende Mini-COG scores van ca. 10% bij 70 tot 80-jarigen, en een percentage van 20-27% bij 80 tot 90-jarigen. De werkgroep is van mening dat een ‘number needed to screen’ van 1 op de 10 ruim voldoende is om een screening rechtvaardigen. De belangrijkste reden voor het preoperatief identificeren van mogelijke cognitieve stoornissen is om de kans op een delier in te schatten en patiënten en naasten hier educatie over te geven. Daarnaast is het raadzaam om bij patiënten met verdenking op cognitieve stoornissen te verwijzen naar de geriater/internist-ouderengeneeskunde voor een CGA voor nadere diagnostiek en ter preoperatieve optimalisatie en postoperatieve medebehandeling. Ter perioperatieve optimalisatie kan de geriater/internist-ouderengeneeskunde interventies adviseren ter delierrisico reductie (zie richtlijn Delier (NVKG, 2020)).

Een tweede belangrijke reden voor het screenen op cognitieve stoornissen is dat de besluitvormingscapaciteiten en wilsbekwaamheid van een patiënt verminderd kunnen zijn wanneer er cognitieve stoornissen zijn. In dat geval is het belangrijk om de naaste/ familieleden (meer) te betrekken bij de besluitvorming, evenals de huisarts.

Als derde reden, wanneer de cognitieve stoornissen ernstig zijn, kan het soms nodig zijn om eerst diagnostiek naar (de ernst en etiologische oorzaak) van de cognitieve stoornissen te verrichten, aangezien de uitkomsten van dat onderzoek de behandelbeslissing kunnen beïnvloeden.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De cognitieve screening kan door de chirurg (in opleiding), of andere zorgverleners zoals een verpleegkundige, verpleegkundig specialist of physican assistant, worden uitgevoerd. Een andere mogelijkheid is dat de anesthesisten (in opleiding), of dienst collega zoals een verpleegkundig specialist of physician assistant, op het preoperatieve spreekuur (POS) deze screening uitvoert. De precieze invulling is aan het betreffende ziekenhuis. De werkgroep vindt het wel belangrijk dat er afspraken worden gemaakt over het organiseren van de cognitieve screening en dat dit in samenspraak met de geriatrie/interne ouderengeneeskunde wordt vormgegeven.

Wanneer al uit de verwijsinformatie blijkt dat een patiënt cognitieve stoornissen heeft, een diagnose dementie of een delier in de voorgeschiedenis kan de patiënt direct verwezen worden naar de geriater/internist-ouderengeneeskunde voor een CGA.

De tijdsbelasting van een cognitieve screening is beperkt tot 5 minuten. Patiënten zouden het confronterend kunnen vinden dat hun cognitie getest wordt, echter de werkgroep is van mening dat met de juiste uitleg en attitude naar patiënt toe omtrent het doel van een dergelijke test dit goed uitvoerbaar is. Daarnaast is het belangrijk dat de persoon die de cognitieve test gaat afnemen daarin getraind is, en de tijd neemt voor uitleg. Een instructievideo van bijv. 10 minuten met uitleg zou voldoende kunnen zijn ter educatie van de persoon die gaat screenen. Een Amerikaanse implementatiestudie toonde aan dat deze werkwijze voor het trainen van anesthesisten (in opleiding) en verpleegkundig specialisten effectief was (Sherman et al., 2019).

Bij patiënten die opgenomen worden voor een acute operatie wordt (indien mogelijk) geïnformeerd bij de naasten of er sprake is van cognitieve stoornissen, dementie of een eerder delier. In dat geval verdient het aanbeveling om direct overleg te hebben met een geriater/internist-ouderengeneeskunde. Vaak is er nog wel enige tijd voor een ad-hoc MDO met bijvoorbeeld geriater/internist-ouderengeneeskunde en anesthesist.

Rationale van de aanbeveling

Hoewel de bewijskracht laag is, lijken cognitieve stoornissen geassocieerd te zijn met een hoger risico op overlijden binnen een jaar na een operatie en met een hoog risico op een postoperatief delirium bij kwetsbare ouderen die een operatie ondergaan. Cognitieve stoornissen in de oudere chirurgische populatie worden vaak niet herkend, terwijl de prevalentie van cognitieve stoornissen aanzienlijk is. Daarnaast worden met name subtiele cognitieve stoornissen vaak niet herkend. Een delier is een ernstige complicatie die in een deel van de patiënten te voorkomen is met preventieve maatregelen. Screening kost enkele minuten en is doorgaans weinig belastend voor de patiënt. De aanbeveling sluit aan bij internationale richtlijnen voor de perioperatieve zorg bij (kwetsbare) ouderen.

Een andere groep die extra aandacht verdient, is die van oudere migranten. In deze groep is de prevalentie van dementie verhoudingsgewijs groter en cognitieve screening lastiger door de taalbarrière. Laagdrempelig inschakelen van een tolk wordt dan ook aangeraden.

Onderbouwing

Conclusies

30-day mortality

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence on the association between pre-operative cognitive impairment and mortality in the first 30 days after surgery in elderly patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery is very uncertain.

Chen, 2022 |

One-year mortality

|

Low GRADE |

Pre-operative cognitive impairment may be associated with a higher risk of mortality in the first year after surgery in elderly patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery.

Chen, 2022; Smith, 2014 |

Complications: delirium

|

Low GRADE |

Pre-operative cognitive impairment may be associated with a higher risk of delirium after surgery in elderly patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery.

Chen, 2022; Sanyaolu, 2020 |

Discharge destination

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence on the association between pre-operative cognitive impairment and the probability of discharge towards a nursing home after surgery in elderly patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery is very uncertain.

Chen, 2022 |

Duration of hospital stay

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence on the association between pre-operative cognitive impairment and the duration of hospital stay after surgery in elderly patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery is very uncertain.

Chen, 2022 |

Physical functioning: functioning at discharge, functional decline, mobility, falls, walking independently/with walking aid

|

No GRADE |

The evidence for physical functioning could not be graded due to a lack of data. |

Cognitive functioning

|

No GRADE |

The evidence for cognitive functioning could not be graded due to a lack of data. |

Quality of life

|

No GRADE |

The evidence for quality of life could not be graded due to a lack of data. |

Social participation

|

No GRADE |

The evidence for social participation could not be graded due to a lack of data. |

Pain

|

No GRADE |

The evidence for pain could not be graded due to a lack of data. |

Patient’s goal (attained?)

|

No GRADE |

The evidence for attainment of the patient’s foal could not be graded due to a lack of data. |

Samenvatting literatuur

MiniCOG

For the summary of literature regarding the MiniCOG: see module Hoe herken je kwetsbaarheid bij patiënten van ≥70 jaar in de preoperatieve setting?.

Description of studies

Chen (2022) performed a systematic review of observational studies. They performed a systematic search, of which the search terms were published in the supplemental data. The search was performed until 8 March 2021. Studies were selected that included patients with an age of 60 years or older undergoing elective or emergency non-cardiac surgeries, who were screened for cognitive impairment preoperatively using a validated screening tool or who had a previous diagnosis of dementia, In which patients with cognitive impairment were compared with patients without cognitive impairment; studies needed to have reported on at least one post operative outcome, should have included 100 patients or more, and should be either randomised controlled trials or observational studies. the study of Chen reported on the following outcomes: post operative delirium, 30 day and one-year mortality, discharge to assisted care, 30-day hospital re-admissions, post-operative complications (not further defined) and hospital length of stay. The included studies used multivariable regression models adjusted for patient characteristics including age and sex, and comorbidities to estimate the effect of cognitive impairment on post-operative outcomes. In total 40 studies that were relevant to this guideline were included in this systematic review.

Sanyaolu (2020) performed a systematic review of observational studies. They performed a systematic search, of which the search terms were published in the supplementary information. The search was performed until June 2019. Studies were selected that included patients undergoing urological surgery, in whom at least one risk factor for post operative delirium was measured; studies needed to have reported on at least one postoperative outcome, and should be observational studies. the study of Sanyaolu reported on the outcome post-operative delirium. The included studies used multivariable regression models adjusted for patient characteristics including age and sex, and comorbidities to estimate the effect of cognitive impairment on post-operative outcomes. Studies that exclusively reported on delirium tremens and studies that were based exclusively in intensive care settings were excluded. In total five studies that were relevant to this guideline were included in this systematic review.

Smith (2014) performed a systematic review of observational studies. The search strategy was published in the appendix. The search was performed until October 2013. Studies of adult cohorts including patients with the proximal femur fracture requiring a surgical intervention were included. Studies should be randomised controlled trials cohort studies or case series. studies should have reported on preoperative variables or characteristics and should have included at least three months of follow up. Studies were excluded when they included patients without a proximal femur fracture or included non-surgical interventions with no possibilities to stratify the results. In total eight studies that were relevant to this guideline were included.

Results

30-day mortality

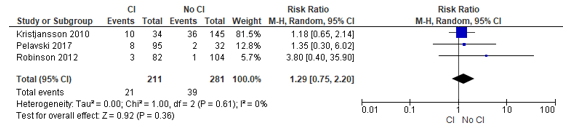

In total, three studies in Chen (2022) reported on 30-day mortality. The results were pooled, and an odds ratio of 1.43 (95% CI: 0.71 to 2.88) was reported, indicating a higher risk of mortality within one year after surgery associated with the presence of cognitive impairment. See Figure 1. Note: we calculated a risk ratio, because the outcome was not rare.

Figure 1 – Pooled risk ratio of patients with or without cognitive impairment and the risk of mortality within 30 days after surgery.

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95 percent confidence interval; CI, cognitive impairment; I2, statistical heterogeneity; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

1-year mortality

In total, four studies in Chen (2022) reported on 1-year mortality. The results were pooled, and an odds ratio of 2.28 (95% CI: 1.39 to 3.74) was reported, indicating a higher risk of mortality within one year after surgery associated with the presence of cognitive impairment.

Smith (2014) reported a pooled risk ratio on 1-year mortality: 1.91 (95% CI: 1.35 to 2.71), indicating a higher risk of mortality within one year after surgery associated with the presence of cognitive impairment.

The results of the underlying studies in Smith (2014) could not be retrieved. Therefore, no pooled effect measure could be calculated.

Complications

Postoperative delirium

Chen (2022) included twelve studies that reported on discharge destination, and presented a pooled odds ratio of 3.84 (95% CI: 2.35 to 6.26), indicating a higher risk of delirium associated with the presence of cognitive impairment.

Sanyaolu (2020) reported a pooled mean difference of -0.476 (95% CI: -1.570 to 0.618).

The results of the underlying studies in Sanyaolu (2020) could not be retrieved, and the two systematic reviews used different forms of effect measures. Therefore, no pooled effect measure could be calculated.

Length of hospital stay

Chen (2022) reported on length of hospital stay; five studies with results on hospital stay were presented. A pooled mean difference was reported of 0.77 (95% CI: -1.23 to 2.78), indicating a longer hospital stay associated with the presence of cognitive impairment.

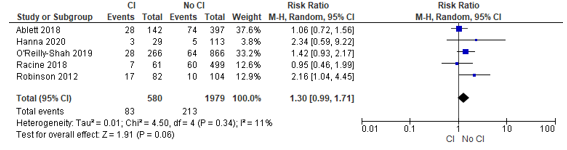

Discharge to nursing home

Chen (2022) included five studies that reported on discharge destination, and presented a pooled odds ratio of 1.74 (95% CI: 1.05 to 2.89), indicating a higher risk of discharge to a nursing home associated with the presence of cognitive impairment. See Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Pooled risk ratio of patients with or without cognitive impairment and the risk of discharge to a nursing home after surgery.

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95 percent confidence interval; CI, cognitive impairment; I2, statistical heterogeneity; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Level of evidence of the literature

30-day mortality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 30-day mortality started at Low (observational studies), and was downgraded to Very low because of imprecision (two levels, confidence interval included the null effect).

One-year mortality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure one-year mortality started at Low (observational studies). There were no limitations that required downgrading of the evidence. There were also no special strengths that allowed for upgrading.

Complications: delirium

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure delirium started at Low (observational studies). There were no limitations that required downgrading of the evidence. There were also no special strengths that allowed for upgrading.

Discharge destination

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure discharge destination started at Low (observational studies), and was downgraded to Very low because of high risk of bias (one level), and imprecision (two levels, confidence interval included the null effect).

Duration of hospital stay

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure duration of hospital stay started at Low (observational studies), and was downgraded to Very low due to high risk of bias (one level), and imprecision (two levels, confidence interval included the null effect).

Physical functioning: functioning at discharge, functional decline, mobility, falls, walking independently/with walking aid

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure physical functioning could not be graded, because no studies that reported this outcome were found.

Cognitive functioning

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cognitive functioning could not be graded, because no studies that reported this outcome were found.

Quality of life

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life could not be graded, because no studies that reported this outcome were found.

Social participation

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure social participation could not be graded, because no studies that reported this outcome were found.

Pain

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain could not be graded, because no studies that reported this outcome were found.

Patient’s goal attainment

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure patient’s goal attainment could not be graded, because no studies that reported this outcome were found.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

Question 2: What is the predictive value of cognitive impairment for postoperative adverse outcomes?

P: Patients aged 70 years or older with an indication for surgery

E: Cognitive impairment

C: No cognitive impairment

O: Test properties (positive/negative predictive value, sensitivity, specificity) for:

- Mortality: postoperative mortality, mortality at discharge, mortality at follow-up

- Complications: length of stay, readmission, pulmonary-cardiac, delirium, pressure ulcers, urinary tract infection, wound infection, falling

- Discharge destination: instituationalization after discharge, geriatric rehabiliation at discharge, independently living at home

- Physical functioning: functioning at discharge, functional decline, mobility, falls, walking independently/with walking aid

- Cognitive functioning

- Quality of life

- Social participation

- Pain

- Patient’s goal (attained?)

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered all outcome measures relevant in the patient-centred decision-making process. Whether an outcome measure is critical or important depends on the individual patient, so the working group did not distinguish critical or important outcome measures.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until July 4th, 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 98 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: relevance to PICO, cohort or case-control study. Sixteen (16) studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 13 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 3 studies were included.

Results

Three (3) studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Aceto P, Antonelli Incalzi R, Bettelli G, Carron M, Chiumiento F, Corcione A, Crucitti A, Maggi S, Montorsi M, Pace MC, Petrini F, Tommasino C, Trabucchi M, Volpato S; Società Italiana di Anestesia Analgesia Rianimazione e Terapia Intensiva (SIAARTI), Società Italiana di Gerontologia e Geriatria (SIGG), Società Italiana di Chirurgia (SIC), Società Italiana di Chirurgia Geriatrica (SICG) and Associazione Italiana di Psicogeriatria (AIP). Perioperative Management of Elderly patients (PriME): recommendations from an Italian intersociety consensus. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020 Sep;32(9):1647-1673. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01624-x. Epub 2020 Jul 10. Erratum in: Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020 Sep 10;: PMID: 32651902; PMCID: PMC7508736.

- Araiza-Nava B, Méndez-Sánchez L, Clark P, Peralta-Pedrero ML, Javaid MK, Calo M, Martínez-Hernández BM, Guzmán-Jiménez F. Short- and long-term prognostic factors associated with functional recovery in elderly patients with hip fracture: A systematic review. Osteoporos Int. 2022 Jul;33(7):1429-1444. doi: 10.1007/s00198-022-06346-6. Epub 2022 Mar 5. PMID: 35247062.

- Centre for Perioperative Care. Preoperative Assessment and Optimisation for Adult Surgery; 2021. https://www.cpoc.org.uk/preoperative-assessment-and-optimisation-adult-surgery

- Chen L, Au E, Saripella A, Kapoor P, Yan E, Wong J, Tang-Wai DF, Gold D, Riazi S, Suen C, He D, Englesakis M, Nagappa M, Chung F. Postoperative outcomes in older surgical patients with preoperative cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2022 Sep;80:110883. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2022.110883. Epub 2022 May 24. PMID: 35623265.

- Culley DJ, Flaherty D, Fahey MC, Rudolph JL, Javedan H, Huang CC, Wright J, Bader AM, Hyman BT, Blacker D, Crosby G. Poor Performance on a Preoperative Cognitive Screening Test Predicts Postoperative Complications in Older Orthopedic Surgical Patients. Anesthesiology. 2017 Nov;127(5):765-774. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001859. PMID: 28891828; PMCID: PMC5657553.

- Evered L, Silbert B, Scott DA. Pre-existing cognitive impairment and post-operative cognitive dysfunction: should we be talking the same language? Int Psychogeriatr. 2016 Jul;28(7):1053-5. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216000661. Epub 2016 May 5. PMID: 27145889.

- Feng MA, McMillan DT, Crowell K, Muss H, Nielsen ME, Smith AB. Geriatric assessment in surgical oncology: a systematic review. J Surg Res. 2015 Jan;193(1):265-72. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.07.004. Epub 2014 Jul 5. PMID: 25091339; PMCID: PMC4267910.

- Goldacre R, Yeates D, Goldacre MJ, Keenan TD. Cataract Surgery in People with Dementia: An English National Record Linkage Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015 Sep;63(9):1953-5. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13641. PMID: 26389991.

- Heng M, Eagen CE, Javedan H, Kodela J, Weaver MJ, Harris MB. Abnormal Mini-Cog Is Associated with Higher Risk of Complications and Delirium in Geriatric Patients with Fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016 May 4;98(9):742-50. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.00859. PMID: 27147687.

- Kapoor P, Chen L, Saripella A, Waseem R, Nagappa M, Wong J, Riazi S, Gold D, Tang-Wai DF, Suen C, Englesakis M, Norman R, Sinha SK, Chung F. Prevalence of preoperative cognitive impairment in older surgical patients.: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2022 Feb;76:110574. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2021.110574. Epub 2021 Nov 5. PMID: 34749047.

- Korc-Grodzicki B, Sun SW, Zhou Q, Iasonos A, Lu B, Root JC, Downey RJ, Tew WP. Geriatric Assessment as a Predictor of Delirium and Other Outcomes in Elderly Patients With Cancer. Ann Surg. 2015 Jun;261(6):1085-90. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000742. PMID: 24887981; PMCID: PMC4837653.

- Kumar CM, Seet E. Cataract surgery in dementia patients-time to reconsider anaesthetic options. Br J Anaesth. 2016 Oct;117(4):421-425. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew301. PMID: 28077527.

- Montroni I, Rostoft S, Spinelli A, Van Leeuwen BL, Ercolani G, Saur NM, Jaklitsch MT, Somasundar PS, de Liguori Carino N, Ghignone F, Foca F, Zingaretti C, Audisio RA, Ugolini G; SIOG surgical task force/ESSO GOSAFE study group. GOSAFE - Geriatric Oncology Surgical Assessment and Functional rEcovery after Surgery: early analysis on 977 patients. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020 Mar;11(2):244-255. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2019.06.017. Epub 2019 Sep 3. PMID: 31492572.

- NVKG. Delier bij volwassenen en ouderen; 2020. Richtlijnendatabase. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/delier_bij_volwassenen_en_ouderen_2023/startpagina_-_delier_bij_volwassenen_en_ouderen_.html

- RIVM. Cijfers en feiten dementie. Loketgezondleven.nl; n.d. https://www.loketgezondleven.nl/gezondheidsthema/gezond-en-vitaal-ouder-worden/wat-werkt-dossier-dementie/cijfers-en-feiten-dementie#:~:text=Op%20basis%20van%20bevolkingsonderzoek%20zijn,en%20ruim%20620.000%20in%202050.

- Royal College of Anesthesists. Chapter 2: Guidelines for the Provision of Anaesthesia Services for the Perioperative Care of Elective and Urgent Care Patients; 2023. RCOA; https://rcoa.ac.uk/gpas/chapter-2

- Oresanya LB, Lyons WL, Finlayson E. Preoperative assessment of the older patient: a narrative review. JAMA. 2014 May;311(20):2110-20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4573. PMID: 24867014.

- Raats JW, Steunenberg SL, de Lange DC, van der Laan L. Risk factors of post-operative delirium after elective vascular surgery in the elderly: A systematic review. Int J Surg. 2016 Nov;35:1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.09.001. Epub 2016 Sep 6. PMID: 27613124.

- Sanyaolu L, Scholz AFM, Mayo I, Coode-Bate J, Oldroyd C, Carter B, Quinn T, Hewitt J. Risk factors for incident delirium among urological patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis with GRADE summary of findings. BMC Urol. 2020 Oct 27;20(1):169. doi: 10.1186/s12894-020-00743-x. PMID: 33109133; PMCID: PMC7590461.

- Smith T, Pelpola K, Ball M, Ong A, Myint PK. Pre-operative indicators for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2014 Jul;43(4):464-71. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu065. Epub 2014 Jun 3. PMID: 24895018.

- Sherman JB, Chatterjee A, Urman RD, Culley DJ, Crosby GJ, Cooper Z, Javedan H, Hepner DL, Bader AM. Implementation of Routine Cognitive Screening in the Preoperative Assessment Clinic. A A Pract. 2019 Feb 15;12(4):125-127. doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000000891. PMID: 30234511.

- Tiwary N, Treggiari MM, Yanez ND, Kirsch JR, Tekkali P, Taylor CC, Schenning KJ. Agreement Between the Mini-Cog in the Preoperative Clinic and on the Day of Surgery and Association With Postanesthesia Care Unit Delirium: A Cohort Study of Cognitive Screening in Older Adults. Anesth Analg. 2021 Apr 1;132(4):1112-1119. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005197. PMID: 33002933.

- Weiss Y, Zac L, Refaeli E, Ben-Yishai S, Zegerman A, Cohen B, Matot I. Preoperative Cognitive Impairment and Postoperative Delirium in Elderly Surgical Patients: A Retrospective Large Cohort Study (The CIPOD Study). Ann Surg. 2023 Jul 1;278(1):59-64. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005657. Epub 2022 Aug 1. PMID: 35913053.

- White S, Griffiths R, Baxter M, Beanland T, Cross J, Dhesi J, Docherty AB, Foo I, Jolly G, Jones J, Moppett IK, Plunkett E, Sachdev K. Guidelines for the peri-operative care of people with dementia: Guidelines from the Association of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2019 Mar;74(3):357-372. doi: 10.1111/anae.14530. Epub 2019 Jan 11. PMID: 30633822.

- Yajima S, Nakanishi Y, Matsumoto S, Ookubo N, Tanabe K, Kataoka M, Masuda H. The Mini-Cog: A simple screening tool for cognitive impairment useful in predicting the risk of delirium after major urological cancer surgery. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2022 Apr;22(4):319-324. doi: 10.1111/ggi.14367. Epub 2022 Mar 6. PMID: 35253337.

Evidence tabellen

Er wordt een preoperatieve screening naar cognitieve stoornissen verricht bij patiënten van ≥70 jaar die indicatie hebben voor operatie met verwachte opnameduur ≥2 dagen. Indien afwijkend, wordt de patiënt verwezen voor een CGA.

Evidencetabellen

Research question: Hoe herken je kwetsbaarheid bij ouderen preoperatief?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Chen, 2022

individual study characteristics deduced from Chen, 2022 |

SR and meta-analysis of cohort studies

Literature search up to March 31, 2021

A: Amado, 2020 B: Pipanmekaporn, 2020 C: Tang, 2020 D: Janssen, 2019 E: O'Reilly-Shah, 2019 F: Racine, 2018 G: Pelavski, 2017 H: Kim, 2013 I: Robinson, 2012 J: Tong, 2020 K: Matsuki, 2020 L: Lee, 2020 M: Ristescu, 2021 N: Mokutani, 2016 O: Korc-Grodzicki, 2015 P: Badgwell, 2013 Q: Kristjansson, 2010 R: Couderc, 2020 S: Susano, 2020 T: Culley, 2017 U: Wu, 2015 V: Styra, 2018 W: Partridge, 2017 X: Partridge, 2014 Y: Sasajima, 2012 Z: Sprung, 2017 AA: Silbert, 2015 AB: Larsson, 2019 AC: Menédez-Colino, 2018 AD: Beishuizen, 2017 AE: Bliemel, 2015 AF: Hotchen, 2016 AG: Mukka, 2016 AH: Soderqvist, 2009 AI: Kagansky, 2004 AJ: Hanna, 2020 AK: Ablett, 2018 AL: Ansaloni, 2010 AM: Partridge, 2015 AN: Levinoff, 2018

Study design: A: prospective observational cohort study B: prospective observational cohort study C: secondary analysis of prospective observational cohort study D: prospective observational cohort study E: retrospective observational cohort study F: prospective observational cohort study G: prospective observational cohort study H: retrospective observational cohort study I: prospective observational cohort study J: prospective observational cohort study K: prospective observational cohort study L: retrospective observational cohort study M: prospective observational cohort study N: prospective observational cohort study O: retrospective observational cohort study P: prospective observational cohort study Q: prospective observational cohort study R: prospective observational cohort study S: prospective observational cohort study T: prospective observational cohort study U: prospective observational cohort study V: prospective and retrospective observational cohort study W: nested prospective observational cohort study within a randomised controlled trial X: prospective observational cohort study Y: prospective observational cohort study Z: prospective observational cohort study AA: prospective observational cohort study AB: secondary analysis of prospective observational cohort study AC: prospective observational cohort study AD: nested prospective observational cohort study within a randomised controlled trial AE: prospective observational cohort study AF: prospective observational cohort study AG: prospective observational cohort study AH: prospective observational cohort study AI: prospective observational cohort study AJ: prospective observational cohort study AK: prospective observational cohort study AL: case control study AM: prospective observational cohort study AN: retrospective observational cohort study

Setting and Country: A: mixed surgery, South Africa B: mixed surgery, Thailand C: mixed surgery, USA D: mixed surgery, Netherlands E: mixed surgery, USA F: mixed surgery, USA G: mixed surgery, Spain H: mixed surgery, South Korea I: mixed surgery, USA J: thoracic surgery, China K: urological surgery, Japan L: neurosurgery, South Korea M: cancer surgery, Romania N: abdominal cancer surgery, Japan O: major cancer surgery, USA P: abdominal cancer surgery, USA Q: abdominal cancer surgery, Norway R: total hip/knee arthroplasty, France S: spinal surgery, USA T: total hip/knee arthroplasty, USA U: total hip arthroplasty, China V: vascular surgery, Canada W: vascular surgery, UK X: vascular surgery, UK Y: vascular surgery, Japan Z: mixed surgery, UK AA: total hip/knee arthroplasty, Australia AB: hip fracture, Sweden AC: hip fracture, Spain AD: hip fracture, The Netherlands AE: hip fracture, Germany AF: hip fracture, UK AG: hip fracture, Sweden AH: hip fracture, Sweden AI: hip fracture, Israel AJ: general surgery, USA AK: general surgery, UK AL: mixed surgery, Italy AM: vascular surgery, UK AN: hip fracture, Canada

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: All: not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR: (1) patients with age ≥ 60 years undergoing elective or emergency non-cardiac surgeries; we chose age ≥ 60 years because multiple studies used this threshold; (2) presence of preoperative positive screening for CI (using validated screening tools), or previous diagnosis of dementia; (3) a comparator group in which no CI was present; (4) data on at least one postoperative outcome (postoperative delirium [POD], mortality, readmission, discharge to assisted care, postoperative complication, length of hospital stay [LOS] or other) is reported; (5) sample size includes ≥100 subjects; and (6) randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies (prospective/retrospective cohorts, cross-sectional, and case-control studies)

Exclusion criteria SR: Inverse of the above

53 studies included, 40 of relevance to this guideline

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question and/or for statistical adjustment (confounding in cohort studies); for example, age, sex, bmi, ...

N, mean age A: 194; 66.3 (7.5) B: 429; 69.9 (7) C: 1189; not reported (not reported) D: 627; 76.6 (5.5) E: 1132; 65.6 (9.8) F: 560; 76.7 (5.2) G: 127; 89.4 (8.2) H: 141; 78 (6.5) I: 185; 73 (6) J: 154; 69.2 (4.1) K: 946; 74.6 (6.5) L: 133; 77.8 (2.8) M: 131; 72.1 (5.9) N: 156; 80.2 (4.1) O: 416; 80 (17) P: 111; 75.3 (18) Q: 182; 81.3 (17.9) R: 101; 74.7 (5.9) S: 219; 75.7 (4.5) T: 211; 72 (6) U: 130; 80.1 (6.1) V: 173; 49.9 (11) W: 209; 75.5 (6.4) X: 114; 76.3 (7.6) Y: 299; 72 (14.8) Z: 2014; 80 (6) AA: 351; 70.4 (6.7) AB: 318; 84.6 (37.2) AC: 509; 85.6 (6.9) AD: 385; 86.9 (7.4) AE: 39; 81 (8) AF: 207; not reported (not reported) AG: 188; 84.4 (5.9) AH: 1944; 84 (6.9) AI: 102; 82.5 (5.3) AJ: 142; 74 (8) AK: 539; 76 (8.9) AL: 351; 76.4 (24.4) AM: 125; 76.3 (7.3) AN: 114; 83.8 (8.1)

Sex: A: I: 29.4%; C: not reported% B: I: 41%; C: not reported% C: I: not reported%; C: not reported% D: I: 63.5%; C: not reported% E: I: 41.7%; C: not reported% F: I: 42%; C: not reported% G: I: 44.9%; C: not reported% H: I: 41.1%; C: not reported% I: I: 96%; C: not reported% J: I: 47.7%; C: not reported% K: I: 78%; C: not reported% L: I: 39.1%; C: not reported% M: I: 50.4%; C: not reported% N: I: 57%; C: not reported% O: I: 45.9%; C: not reported% P: I: 55%; C: not reported% Q: I: 43%; C: not reported% R: I: 38.5%; C: not reported% S: I: 57%; C: not reported% T: I: 39.8%; C: not reported% U: I: 23.8%; C: not reported% V: I: 75.1%; C: not reported% W: I: 76.1%; C: not reported% X: I: 66.7%; C: not reported% Y: I: 87.3%; C: not reported% Z: I: 52.7%; C: not reported% AA: I: 30%; C: not reported% AB: I: not reported%; C: not reported% AC: I: 20.8%; C: not reported% AD: I: 28.8%; C: not reported% AE: I: 27%; C: not reported% AF: I: 33.8%; C: not reported% AG: I: 30.3%; C: not reported% AH: I: 25.3%; C: not reported% AI: I: 25.5%; C: not reported% AJ: I: not reported%; C: not reported% AK: I: 47.5%; C: not reported% AL: I: 40.9%; C: not reported% AM: I: 68.8%; C: not reported% AN: I: 26.3%; C: not reported%

Groups comparable at baseline? All: not applicable |

Prevalence of cognitive impairment and definition A: 57.2%: Mini-Cog <=3 B: 18.4% MSET10 <22/29 elementary; 17/29 dementia; 14/23 illiterate C: 22.8% by Langa-Weir cognitive algorithm D: 7.0% MMSE <= 24 E: 15.5% Mini-Cog test <=2 F: 11.0% neuropsych testing >=1 SD below mean G: 74.8% MMSE <= 26 H: 36.9% MMSE-KC <24 I: 44.1% Mini-Cog <=3 J: 49.4% MoCA <26 K: 6.3% HDS-R<20 L: 21.1% MMSE-K<24 M: 51.9% Mini-Cog <=3 N: 26.9% MMSE<@4 O: 30.8% Mini-Cog <=3 P: 21.0% Mini-Cog<=3 Q: 19.0% MMSE<24 R: 80.0% CODEX>=1 S: 23.0% Mini-Cog<=2 T: 23.7% Mini-Cog<=2 U: 60% MMSE<25 V: 68.8% MoCA<24 W: 23% MoCA<24 X: 67.5% MoCA <24 Y: 18.7% HDS-R <=20 Z: 17.2% STMS, MHIS, MDS-UPDRS AA: 32.0% Neuropsychological testing >=2SD below mean AB: 21.4% SPMSQ<8 correct AC: 47.9% SPMSQ <8 correct AD: 60.3% IQCODE-sf ≥ 3.4 AE: 33.3% MMSE ≤26 AF: 55.6% AMTS <9 AG: 30.9% SPSMSQ <8 correct AH: 55.5% SPMSQ <8 correct AI: 23.5% MMSE <25 AJ: 20.0% English MoCA <26, Spanish MoCA <21 AK: 26.3% MoCA <18 AL: 12.6% SPMSQ ≤7 AM: 41.6% MoCA <24 AN: 32.5%, definition not reported |

Not applicable

|

"Duration of follow-up: A: none

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control A: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: B: 2 years

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control B: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: C: in hospital

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control C: I: not applicable; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: D: 3 years

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control D: I: not applicable; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: E: 1 month

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control E: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: F: 3 years

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control F: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: G: 6 months

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control G: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: H: 1 year

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control H: I: not applicable; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: I: in hospital

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control I: I: not applicable; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: J: none

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control J: I: no follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: K: none

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control K: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: L: none

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control L: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: M: 6 months

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control M: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: N: 3 months

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control N: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: O: 3 years

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control O: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: P: 3 months

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control P: I: no follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: Q: 3 years

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control Q: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: R: none

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control R: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: S: none

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control S: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: T: in hospital

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control T: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: U: none

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control U: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: V: none

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control V: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: W: in hospital

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control W: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: X: in hospital

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control X: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: Y: 3 years

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control Y: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: Z: none

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control Z: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: AA: none

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control AA: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: AB: 1 year

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control AB: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: AC: 1 year

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control AC: I: not applicable; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: AD: 1 year

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control AD: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: AE: in hospital

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control AE: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: AF: in hospital

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control AF: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: AG: 1 year

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control AG: I: not applicable; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: AH: 2 years

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control AH: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: AI: 6 months

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control AI: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: AJ: 1 month

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control AJ: I: not applicable; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: AK: 3 months

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control AK: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: AL: in hospital

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control AL: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: AM: 3 years

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control AM: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: AN: none

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control AN: I: no selective loss to follow-up; C: not applicable"

|

Outcome measure-1 30-day mortality OR G: 1.38 (95% CI: 0.28 to 6.86) I: OR 3.91 (95% CI: 0.40 to 38.32) Q: OR 1.26 (95% CI: 0.55 to 2.89)

Pooled OR: 1.43 (95% CI: 0.71 to 2.88)

Outcome measure-2 C: 1-year mortality OR 1.39 (95% CI: 0.94 to 2.04) AB: OR 2.29 (95% CI: 1.20 to 4.38) AC: OR 3.76 (95% CI: 2.40 to 5.89) AG: OR 2.35 (95% CI: 1.21 to 4.55)

Pooled OR: 2.28 (95% CI: 1.39 to 3.74)

Outcome measure-3 Postoperative delirium:

B: OR 4.56 (95% CI: 1.93 to 10.75) D: OR 6.37 (95% CI: 3.22 to 12.59) F: OR 2.91 (95% CI: 1.68 to 5.04) J: OR 2.64 (95% CI: 1.18 to 5.90) N: OR 7.77 (95% CI: 3.37 to 17.93) O: OR 1.68 (95% CI: 1.01 to 2.83) V: OR 0.51 (95% CI: 0.20 to 1.31) X: OR 2.16 (95% CI: 0.67 to 7.00) AI: OR 9.25 (95% CI: 2.48 to 34.50) AK: OR 84.62 (95% CI: 11.34 to 631.13) AL: OR 4.89 (95% CI: 2.40 to 10.00) AN: OR 5.42 (95% CI: 1.94 to 15.16)

Pooled OR: 3.84 (95% CI: 2.35 to 6.26)

Outcome measure 4 Instutionalization after discharge

E: OR 1.12 (95% CI: 0.80 to 1.56) F: OR 1.95 (95% CI: 1.09 to 3.47) I: OR 3.01 (95% CI: 1.55 to 5.86) AE: OR 0.88 (95% CI: 0.52 to 1.50) AJ: OR 4.02 (95% CI: 1.66 to 9.71)

Pooled OR: 1.74 (95% CI: 1.05 to 2.89)

Outcome measure 5 Postoperative complications

F: OR 0.74 (95% CI: 0.26 to 2.15) G: OR 1.29 (95% CI: 0.57 to 2.95) I: OR 2.36 (95% CI: 1.25 to 4.45) J: OR 1.43 (95% CI: 0.71 to 2.91) N: OR 2.75 (95% CI: 1.31 to 5.77) R: OR 1.25 (95% CI: 0.45 to 3.50) X: OR 2.59 (95% CI: 1.08 to 6.22) AJ: OR 2.68 (95% CI: 1.10 to 6.50)

Pooled OR: 1.85 (95% CI:1.37 to 2.49)

Outcome measure 6 Length of hospital stay MD I: 6 (95% CI: 2.51 to 9.49) J: 0.7 (95% CI: 0.09 to 1.31) AE: -2.30 (95% CI: -3.50 to -1.10) AG: -1.10 (95% CI: -4.35 to 2.15) AJ: 2 (95% CI: 0.42 to 3.58)

Pooled MD: 0.77 (95% CI: -1.23 to 2.78) |

Facultative:

The authors conclude that impairment leads to an increased risk of one year mortality discharged to assisted care or delirium. A leave-one-out analysis thowed that Tang (2020) contributed disproportionally to the statistical heterogeneity.

Personal remarks Tim Christen (Kennisinstituut) This study included many different patients with many different operations and several ways of determining the Degree of cognitive impairment. However, the results were relatively consistent across these groups which increases the robustness of the results.

Subgroup analyses were performed for different types of operations. |

|

Sanyaolu, 2020

individual study characteristics deduced from Sanyaolu, 2020

|

SR and meta-analysis of cohort studies

Literature search up to June 2019

A: Hamann, 2005 B: Large, 2012 C: Tai, 2015 D: Tognoni, 2010 E: Xue, 2016

Study design: A: prospective observational cohort study B: prospective observational cohort study C: prospective observational cohort study D: prospective observational cohort study E: prospective observational cohort study

Setting and Country: A: urological surgery, "Europe" B: urological surgery, USA C: urological surgery, China D: urological surgery, "Europe" E: urological surgery, China

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: All: not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR: studies of humans published in English, using a validated delirium diagnostic/assessment tool and evaluating risk factors for incident POD. Only full papers published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal were considered

Exclusion criteria SR: not reported

7 studies included, of which 5 relevant to this PICO

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question and/or for statistical adjustment (confounding in cohort studies); for example, age, sex, bmi, ...

N, mean age A: 100; 71.9 (not reported) B: 49; median 77.8 (outcome pos) 73.1 (outcome neg) () C: 485; 71.3 (2.35) D: 90; 74.3 (0.4) E: 358; 78.1 (outcome pos) 73.1 (neg) (5.33 (pos) 6.39 (neg))

Sex: A: I: 77%; C: not reported% B: I: 82%; C: not reported% C: I: 100%; C: not reported% D: I: 90%; C: not reported% E: I: 100%; C: not reported%

Groups comparable at baseline? All: not applicable |

No definition of cognitive impairment was reported

|

Not applicable

|

"Duration of follow-up: A: 7 days or until discharge

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control A: I: not reported; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: B: 7 days

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control B: I: not reported; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: C: 7 days

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control C: I: not reported; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: D: 7 days

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control D: I: not reported; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: E: 7 days

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control E: I: not reported; C: not applicable"

|

Postoperative delirium Diagnosed by Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), DSM-V or DSM-IV

B: MD: -2.1 (95% CI: -3.8 to -0.4) C: MD: 0.9 (95% CI: 0.6 to 1.2) D: MD: -0.8 (95% CI: -1.1 to -0.5) E: MD: -0.5 (95% CI: -1.1 to -0.0)

Pooled effect (random effects model): -0.476 (95% CI: -1.570 to 0.618), direction: higher MMSE score with a lower risk of postoperative delirium. Heterogeneity (I2): 96%

|

Facultative:

The authors conclude that there is a significant increase in the risk of delirium in patients with higher cognitive impairments preoperatively.

Personal remarks; this was a reasonably well beforem systematic review with enough information about the underlying trials to decide whether or not to include this study and to evaluate the quality of the underlying studies.

No sensitivity analysis were performed.

The authors did not report statistical heterogeneity. |

|

Smith, 2014

individual study characteristics deduced from Smith, 2014

|

SR and meta-analysis of cohort studies

Literature search up to October 2013

A: Givens, 2008 D: Holmes, 2000 C: Ishida, 2005 F: Petersen, 2006 G: Pitto, 1994 B: Williams, 2005 E: Withey, 1995 H: Wood, 1992

Study design: A: cohort study D: cohort study C: cohort study F: cohort study G: cohort study B: cohort study E: cohort study H: cohort study

Setting and Country: A: hip fracture, USA D: hip fracture, UK C: hip fracture, Japan F: hip fracture, Denmark G: hip fracture, Italy B: hip fracture, UK E: hip fracture, UK H: hip fracture, UK

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: All: not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR: Studies of adult cohorts including patients with a proximal femur fracture, requiring a surgical intervention. RCT, cohort studies and case series. Reporting pre-operative variables/characteristics and at least 3-month follow-up.

Exclusion criteria SR: Not proximal femur fracture, inclusion of non-surgical intervention results with no possibilities to stratify results.

8 relevant studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, mean age A: 126; 79 (not reported) D: 731; 80 (not reported) C: 74; 93 (not reported) F: 1183; 84 (not reported) G: 143; 81 (not reported) B: 381; 81 (not reported) E: 492; 82 (not reported) H: 531; 78 (not reported)

Sex: A: I: 21.4%; C: not reported% D: I: 17.6%; C: not reported% C: I: 12.2%; C: not reported% F: I: 22.2%; C: not reported% G: I: 12.6%; C: not reported% B: I: not reported%; C: not reported% E: I: 21.3%; C: not reported% H: I: 19.2%; C: not reported%

Groups comparable at baseline? A: not applicable D: not applicable C: not applicable F: not applicable G: not applicable B: not applicable E: not applicable H: not applicable |

Describe intervention:

A: Not reported D: Not reported C: Not reported F: Not reported G: Not reported B: Not reported E: Not reported H: Not reported |

Describe control:

A: na D: na C: na F: na G: na B: na E: na H: na |

"Duration of follow-up: A: 6 months

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control A: I: more than 85% finished follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: D: 6 months

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control D: I: more than 85% finished follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: C: 5.5 years

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control C: I: more than 85% finished follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: F: 12 months

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control F: I: more than 85% finished follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: G: 60 months

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control G: I: more than 85% finished follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: B: 12 months

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control B: I: less than 85% finished follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: E: 12 months

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control E: I: more than 85% finished follow-up; C: not applicable" "Duration of follow-up: H: 6 months

Loss to follow-up: N (%) Intervention; N (%) Control H: I: less than 85% finished follow-up; C: not applicable"

|

Outcome measure-1 1-year mortality Pooled estimate RR: 1.91 (95% CI: 1.35 to 2.70)

|

Facultative:

The authors conclude that a lower pre-operative cognitive function significantly predicts 12-month postoperative mortality, but there is a large variety between the underlying studies.

No sensitivity analyses. Statistical heterogeneity was mentioned, unexplained.

Remarks TC, Kennisinstituut: quite limited information about the underlying studies, also no unpooled results, which makes it more difficult to assess whether pooling was justified etc.

|

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Chen, 2022 |

Yes

Reason: Question very well formulated |

Yes

Reason: well described literature search |

No

Reason: Excluded studies not cited and reason for exclusion not specified per study |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes

Reason: studies were assessed using GRADE |

Yes |

Yes

Reason: Inlcuded in GRADE assessment |

No

Reason: only CoI of authors of systematic review were reported |

|

Smith, 2014 |

Yes |

Yes |

No

Reason: excluded studies referenced but not described in supplementary data |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes

Reason: CASP Cohort Study assessment of study quality used for quality assessment |

Yes |

Yes |

No

Reason: only CoI of authors of systematic review were reported |

|

Sanyaolu, 2020 |

Yes |

Yes |

No

Reason: excluded studies not referenced and not described |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes

Reason: studies were assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale |

Yes |

Yes

However, funnel plot with five studies was presented, which was informative nor relevant |

No |

Exclusietabel

|

Auteur en jaartal |

Redenen van exclusie |

|

Selvakumar, 2022 |

no information on precision of results |

|

Feng, 2015 |

wrong exposure |

|

Araiza-Nava, 2022 |

no quantitative results |

|

Oresanya, 2014 |

narrative review |

|

Raats, 2016 |

missing results data |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 09-04-2024

Laatst geautoriseerd : 09-04-2024

Geplande herbeoordeling : 09-04-2028

Algemene gegevens

In samenwerking met : bovenstaande partijen, Verenso, Verpleegkundigen en Verzorgenden Nederland – Verpleegkundig Specialisten en Genero

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijn.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij chirurgie bij kwetsbare ouderen.

Werkgroep

Dr. D.E. (Didy) Jacobsen (voorzitter), Nederlandse Vereniging voor Klinische Geriatrie

Dr. H.A. (Harmke) Polinder-Bos, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Klinische Geriatrie

Dr. S. (Suzanne) Festen, Nederlandse Internisten Vereniging

N.S. (Niamh) Landa-Hoogerbrugge, MSc Verpleegkundigen en Verzorgenden Nederland en Verpleegkundigen en Verzorgenden Nederland – Verpleegkundig Specialisten

Dr. H.P.A. (Eric) van Dongen, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Anesthesiologie

Dr. J. (Juul) Tegels, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde

Drs. P.E. (Petra) Flikweert, Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging

Drs. H.P.P.R. (Heike) de Wever, Verenso

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger

M.R. (Marike) Abel- van Nieuwamerongen, Genero

Met ondersteuning van

Drs. E.A. (Emma) Gans, adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Drs. L.A.M. (Liza) van Mun, junior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Dr. T. (Tim) Christen, adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Dr. J.F. (Janke) de Groot, senior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Y. (Yvonne) van Kempen, projectsecretaresse, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Naam |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Persoonlijke Financiële Belangen |

Persoonlijke Relaties |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek |

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie |

Overige belangen |

Datum |

Actie |

|

Didy Jacobsen (voorzitter) |

Internist-ouderengeneeskunde, academisch medisch specialist, Radboudumc afdeling geriatrie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

- |

Niet aanwezig. |

Nieuwe onderzoeksvoorstel op het gebied van zorgpadoptimalisatie/zorgpadontwikkeling voor ouderen met hoogrisico plaveiselcelcarcinoom. Vanuit dermatologie (Radboudumc) wordt dit opgezet. Ik denk mee voor geriatrisch perspectief. |

30-09-2021 |

Geen restricties |

|

Heike de Wever |

Specialist ouderengeneeskunde, kaderarts geriatrische revalidatie bij de stichting TanteLouise |

Lid van kerngroep kaderartsen geriatrische revalidatie van Verenso (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Neen |

Neen |

Neen |

Neen |

1-12-2021 |

Geen restricties |

|

Suzanne Festen |

Internist ouderengeneeskunde |

Nvt |

Geen belangenverstrengeling |

Geen belangenverstrengeling |

Betrokken bij ZIN subsidie en KWF subsidie |

Behoudens dat de inhoud raakt aan mijn expertise in klinisch werk en onderzoek geen belangen. |

Nvt |

11-11-2021 |

Geen restricties |

|

Eric van Dongen |

Anesthesioloog maatschap anesthesiologie, ic en pijnbestrijding |

Bestuur E infuse, vacatiegelden |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Co-founder AGE MDO, ketenzorg perioperatief proces kwetsbare oudere |

Geen |

11-10-2021 |

Geen restricties |

|

Harmke Polinder- Bos |

Klinisch Geriater, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

2021: COOP-studie |

Behoudens dat de inhoud raakt aan mijn expertise in klinisch werk en onderzoek geen belangen. |

Geen |

4-10-2021 |

Geen restricties |

|

Niamh Landa - Hoogerbruggen |

Verpleegkundig specialist GE-chirurgie/klinische geriatrie Maasstad ziekenhuis |

Bestuurslid V&VN geriatrie en gerontologie |

Nee |

Nee |

Nee |

Neveneffect kan zijn meer expertise ontwikkelen op dit gebied en zodoende integreren in huidig zorgpad dieontwikkeld is |

Nee |

29-09-2021 |

Geen restricties |

|

Juul Tegels |

Lid richtlijnwerkgroep |

Traumachirurg, fellow |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Geen |

18-3-2022 |

Geen restricties |

|

Petra Flikweert |

Orthopedisch chirurg, Reinier haga orthopedisch centrum, zoetermeer. Vanuit de NOV gemandateerde voor de werkgroep. |

Commissie kwaliteit - Haga ziekenhuis - onbetaald Commissie kwaliteit - NOV - onbetaald Onderwijscommissie NOV - onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

3-9-2023 |

Geen restricties |

|

Marike Abel- van Nieuwamerongen |

Lid ouderen- en mantelzorgforum; Genero (onbezoldigd> onkostenvergoeding) |

Lid RvT landelijke medezeggenschapsorganisatie cliënten Lid Cliëntenraad ziekenhuis in Tilburg Lid Cliëntenraad 1e lijnsorganisatie in Etten-Leur (onbetaalde functies, wel onkostenvergoeding) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

6-9-2023 |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en KBO-PCOB voor de schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Genero, KBO-PCOB en Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er [waarschijnlijk geen/ mogelijk] substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst kwalitatieve raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Preoperatieve herkenning van kwetsbaarheid |

geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de werkgroep de knelpunten in de chirurgische zorg voor kwetsbare ouderen. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbevelingen uit de eerdere richtlijnmodule (NVKG, 2016) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door betrokken partijen via een schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||