Prokinetica

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van prokinetica bij patiënten met maagretentie op de Intensive Care die enteraal gevoed worden?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg de toediening van prokinetica bij patiënten met maagretentie of andere tekenen van voedingsintolerantie. Erythromycine heeft mogelijk de voorkeur ten opzichte van metoclopramide.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een systematische literatuuranalyse uitgevoerd waarbij het gebruik van prokinetica is vergeleken met het niet gebruiken van prokinetica in IC-patiënten die enteraal gevoed worden. Dertien vergelijkende studies zijn hierbij meegenomen, die de prokinetica metoclopramide en/of erythromycine vergeleken met een placebo of geen interventie. Het waren over het algemeen studies met kleine populaties, wat invloed heeft gehad op de sterkte van de bewijskracht.

Voedingsintolerantie was de cruciale uitkomstmaat. Erythromycine liet een klinisch relevant verschil zien in het voordeel van het middel ten opzichte van placebo, hoewel de bewijskracht laag was. Voor metoclopramide konden geen eenduidige conclusies worden getrokken over voedingsintolerantie, vanwege een zeer lage bewijskracht.

De overall bewijskracht is hiermee zeer laag.

Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat ‘percentage van het voedingsdoel behaald’ werd ook een zeer lage bewijskracht gevonden. Voor beide prokinetica is het effect daarom onzeker.

De uitkomstmaat ‘succesvolle plaatsing van de postpylorische voedingssonde’ kwam uit op een lage bewijskracht (GRADE) voor erythromycine, waarbij werd afgewaardeerd voor imprecisie en conflicterende resultaten. Klinisch relevante verschillen werden gevonden voor erythromycine in het voordeel van prokineticagebruik. Voor metoclopramide werd een zeer lage bewijskracht gerapporteerd, waarbij naast imprecisie en conflicterende resultaten ook werd afgewaardeerd voor risico op bias.

Ook het effect van prokinetica op mortaliteit is erg onzeker, vanwege o.a. beperkingen in studiedesigns en conflicterende resultaten. De GRADE-beoordelingen voor erythromycine en metoclopramide komen uit op zeer laag. Hierdoor konden geen eenduidige conclusies getrokken worden.

Voor de uitkomstmaat pneumonie is de GRADE-beoordeling zeer laag vanwege risico op bias en imprecieze resultaten.

Voor opnameduur in het ziekenhuis is de GRADE-beoordeling laag. Dit komt door imprecieze resultaten. Deze beoordeling is gebaseerd op slechts drie RCT’s met kleine studiepopulaties. Er werd een verschil gevonden dat net klinisch relevant is voor metoclopramide, maar niet voor erythromycine.

Gezien de mogelijk positieve effecten van erythromycine op o.a. voedingstolerantie en succesvolle plaatsing van een postpylorische voedingssonde valt het te overwegen om het een plaats te geven bij de kritisch zieke patiënt die sondevoeding toegediend krijgt. Dit is in overeenstemming met de ESPEN- en ASPEN-richtlijnen. Het blijft echter maatwerk hoe omgegaan moet worden bij de IC-patiënt met maagretentie om de voedingsdoelen te halen.

Van erytromycine is bekend dat het in hoge doses bij snelle intraveneuze toediening (<30 minuten) QT-verlenging kan veroorzaken, wat weer kan resulteren in torsades de pointes. Echter in lagere doseringen (1-2mg/kg) bij infusie in meer dan 30 minuten is dit nooit beschreven. Ook metoclopramide kan QT-verlenging veroorzaken. Het is van belang dat men zich ervan bewust is, dat ernstige hartritmestoornissen kunnen optreden bij deze middelen. Monitoring van het QT-interval is aan te raden, hetgeen standaard is voor patiënten op de IC.

Het gebruik van erythromycine in lage doseringen en voor korte tijd zou in theorie kunnen resulteren in bacteriële resistentie. De micro-organismen waarvoor erythromycine in Nederland wordt gebruikt, kunnen niet resistent worden voor erythromycine (e.g. Legionella, Mycoplasma).

Bekende bijwerkingen van erythromycine in antibiotische (hoge) doseringen (Lareb) zijn soms maagdarmklachten. Erythromycine in hoge doses (500-1000 mg iv) kan klachten geven van buikrampen, misselijkheid en braken. In lage doses geeft erythromycine deze bijwerkingen niet. Zelden: ontstoken slijmvliezen en zeer zelden minder goed kunnen horen en minder goed kunnen zien. Verder psychische klachten, duizeligheid, koorts, epilepsie, hartkloppingen en andere hartritmestoornissen waarschijnlijk bij patiënten met een verlengd QT-interval.

De verwachte effecten van een prokineticum zijn mogelijk een verbeterde lediging van de maag wat leidt tot minder maagretentie, voedingstolerantie en een positief effect op de positionering van een postpylorische voedingssonde. Een positief effect op opnameduur en mortaliteit zijn niet te verwachten. Een kortere opnameduur zou een maat kunnen zijn voor een sneller herstel door hogere voedingsinname. De opnameduur wordt echter door vele factoren beïnvloed en de spreiding in opnameduur tussen de verschillende onderzoeksgroepen is groot, waardoor de kans op het vinden van klinisch relevante verschillen klein is. Het vergelijken van de studies wordt verder bemoeilijkt door het gebruik van verschillende doseringen van de geteste prokinetica en verschillende definities die zijn gebruikt.

De verwachting is niet dat een optimale voedingsinname resulteert in een lagere mortaliteit. Voor een positief effect van prokinetica op het behalen van voedingsdoelen is op dit moment te weinig bewijs. De geïncludeerde studies omvatten te weinig patiënten.

Mortaliteit is wel een veiligheidsoverweging en zou hoger kunnen uitvallen omdat erythromycine levensbedreigende hartritmestoornissen, Torsades de pointes, zou kunnen veroorzaken. Dit is niet beschreven voor lage doseringen erythromycine ook niet bij patiënten die al een verlengd QT-interval op het ECG hebben. Naast lage doseringen en het langzaam toedienen zal kunnen worden gepostuleerd dat het continue bewaken van het hartritme bij IC-patiënten de veiligheid van de patiënt verhogen t.o.v. afdelingen waar geen continue bewaking van de patiënt is.

Voorbeeld van veiligheidsoverweging is het tot 2010 veel gebruikte prokineticum cisapride. Cisapride is van de markt gehaald i.v.m. oversterfte veroorzaakt door ernstige ritmestoornissen (Aboumarzouk, 2011).

Er zijn geen duidelijke subgroepen van IC-groepen met voedingsintolerantie. Er zijn publicaties geïncludeerd waarin interne, chirurgische en neurotrauma patiënten zijn opgenomen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor de IC-patiënt met voedingsintolerantie zijn op dit moment weinig medicamenteuze alternatieven anders dan erythromycine en metoclopramide. Erythromycine i.v. is een goede veilige eerste keuze bij IC-patiënten met een maagretentie van boven de 250 mL. Het achterwege laten van erythromycine als behandeling van voedingsintolerantie zal resulteren in misselijkheid, braken en niet snel behalen van de voedingsdoelen. Een alternatieve behandeling van voedingsintolerantie is het plaatsen van een postpylorische sonde; dit is echter voor de patiënt wel meer belastend. Plaatsing van postpylorische voedingssonde kan endoscopisch, radiologisch of door insufflatie van lucht in combinatie met auscultatie of radiografisch veelal na toediening van erythromycine plaatsvinden.

Erythromycine heeft meestal binnen drie dagen een positief effect op de maagretentie. Indien erythromycine i.v. niet resulteert in een positief effect dan moet een acute buik o.b.v. obstructie of paralytische ileus worden uitgesloten. Dit zou ook moeten voordat men overgaat tot het plaatsen van een jejunumsonde bij persisteren maagretentie (ondanks erythromycine). De jejunumsonde is veel invasiever, belastender en risicovoller dan erythromycine i.v. Het lijkt even effectief als het gaat om het halen van voedingsdoelen.Bij persisteren van de maagretentie kan ook erythromycine worden gecombineerd met metoclopramide i.v.

Er is een aantal subgroepen van IC-patiënten waarvoor een ander beleid geldt, namelijk bij grote (veelal oncologische) abdominale chirurgie. Hierbij wordt preoperatief geregeld een postpylorische voedingssonde geplaatst, gebruikmakend van de dan nog ongestoorde eigen peristaltiek, of er wordt peroperatief een naald-jejunostomie verricht.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De prijs van prokinetica, erythromycine en metoclopramide, is geen belemmering. Het gebruik van erythromycine reduceert de noodzaak tot plaatsing van een postpylorische voedingssonde. Plaatsing van een postpylorische voedingssonde is risicovoller en duurder.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Bij een gebrek aan studies van voldoende grootte zijn er vele belemmeringen om erythromycine of metoclopramide als prokineticum te implementeren. Het bewijs in deze richtlijn is niet overtuigend genoeg om erythromycine te gaan implementeren ondanks een positievere aanbeveling in de ESPEN-richtlijn. In de studies die gebruikt zijn in deze richtlijn, zijn verschillende doseringen en behandelduur gebruikt, waardoor een eenduidig doseringsadvies niet mogelijk is. Wel is duidelijk dat het om lage intraveneuze doseringen erythromycine gaat.

Er zou weerstand tegen het gebruik van erythromycine als prokineticum kunnen bestaan gezien de gevaren van een QTc-verlenging. In combinatie met andere QTc-verlengende medicamenten zou het gebruik van erythromycine in een levensbedreigende hartritmestoornis kunnen resulteren in de vorm van een Torsades des Pointes. Het gevaar van een QTc-verlenging kan worden voorkomen door de lage dosering van 1-2 mg erythromycine i.v. langzaam, in meer dan dertig minuten, in te laten lopen. De risico’s kunnen verder worden verkleind door continue ECG monitoring, wat standaard plaats vindt op IC’s. Alternatief voor de continue monitoring is het regelmatig vervaardigen van een 12-afleidingen ECG met aandacht voor verlenging van QTc-interval.

Het aantal goed opgezette studies met erythromycine versus placebo is te klein om harde uitspraken te doen op afname maagretentie, afname aantal plaatsingen postpylorische voedingssonde, sneller halen voedingsdoel, afname aspiratierisico met minder pneumoniae en sneller herstel van de IC-patiënt. Deze kennislacune zal zich moeilijk goed laten onderzoeken, bijvoorbeeld door de verschillende gebruikte doseringen, de duur van toediening en verschillende toedieningsschema’s. Het zal heden ten dagen ook lastig worden om het benodigde aantal patënten te verkrijgen. Voor de introductie van erythromycine moesten veel patiënten gevoed worden via een postpylorische voedingssonde vanwege persisterende maagretentie. Dit aantal daalde dramatisch na de introductie van lage doseringen erythromycine als prokineticum. Met de introductie van sondevoedingen met wei-koemelkeiwit in plaats van casinaat-koemelkeiwit zien we een verdere significante afname in het aantal IC patiënten die erythromycine nodig hebben vanwege maagretentie.

Bij lage doseringen erythromycine en langzame -in meer dan 30 minuten- intraveneuze toediening ter behandeling van maagretentie worden geen problemen verwacht bij IC-patiënten. De kosten zijn laag en het erythromycine is goed verkrijgbaar.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Voor het gebruik van intraveneus metoclopramide als prokineticum, is beperkt bewijs in de literatuur. Voor het gebruik van intraveneus erythromycine in lage doses als prokineticum bij maagretentie is meer rationale. In de literatuuranalyse voor deze richtlijnmodule zijn echter beide middelen niet direct met elkaar vergeleken. Indien plaatsing van een postpylorische voedingssonde noodzakelijk wordt geacht, kan dit worden gefaciliteerd door kort voor plaatsing van de postpylorische voedingssonde eenmalig erythromycine toe te dienen.

Bij patiënten op de IC met maagretentie of met een indicatie voor plaatsing van een postpylorische voedingssonde zijn lage doseringen (1-2 mg/kg) intraveneus erythromycine te overwegen. Uit de literatuur wordt geconcludeerd dat het gebruik van lage doseringen intraveneus erythromycine mogelijk resulteert in afname van de voedingsintolerantie en frequentere succesvolle plaatsing van een postpylorische voedingssonde indien dit laatste geïndiceerd is.

De afname van voedingsintolerantie door het gebruik erythromycine zou moeten resulteren in sneller behalen van de voedingsdoelen dan placebo. Het sneller halen van het voedingsdoel zou op zijn beurt weer moeten resulteren in een sneller herstel en kortere ziekenhuisopname. De geanalyseerde en geïncludeerde studies zijn echter te klein om deze verwachtingen te onderbouwen. Wat ook niet wordt teruggevonden in de literatuur is dat de afname van de voedingsintolerantie en maagretentie de kans op aspiratie van maaginhoud doet verkleinen met minder pneumonieën tot gevolg. Ook hiervoor zijn de studies te klein om dit te bewijzen.

Argumenten tegen het implementeren van lage intraveneuze doses erythromycine zijn de kans op een QTc-verlenging, wat in combinatie met andere QTc-verlengende medicatie kan resulteren in een levensbedreigende hartritmestoornis. Voor het effect van prokinetica op mortaliteit kunnen we echter geen eenduidige conclusies trekken. Tevens zijn er geen case reports die laten zien dat lage doses erythromycine, toegediend in langer dan dertig minuten, resulteert in een QTc-verlenging of levensbedreigende hartritmestoornis.

Te kleine en te weinig prospectieve dubbelblinde gerandomiseerde studies met verschillende inclusiecriteria zijn ook de redenen dat er geen verschillen worden gevonden op andere eindpunten, anders dan afname van voedingsintoleranite en succesvolle plaatsing postpylorische voedingssonde.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Bij Intensive Care (IC) patiënten die enteraal gevoed worden, wordt routinematig/ protocollair maagretentie gemeten (zie module maagretentie routinematig meten). Verhoogde maagretentie komt vaak voor door vertraagde maaglediging en intolerantie voor de enterale voeding. Door het optreden van maagretentie duurt het langer voordat IC-patiënten hun voedingsdoelen halen. Prokinetica beogen een betere maagontlediging en worden regelmatig gebruikt bij maagretentie en intolerantie voor sondevoeding. Het is van belang om inzicht te krijgen in de effectiviteit en belangrijke bijwerkingen van verschillende prokinetica en de toedieningsweg bij het verbeteren van de tolerantie van enterale voeding en het behalen van de voedingsdoelen.

Er is momenteel veel praktijkvariatie in hoe om te gaan met maagretentie om de gestelde voedingsdoelen te halen bij IC-patiënten. Daarom moet meer duidelijkheid komen over de rol van prokinetica bij enterale voeding op de IC.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Low GRADE

|

Erythromycin may reduce feeding intolerance when compared with no prokinetic use in intensive care patients.

Sources: Berne, 2002; Reignier, 2002. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain whether metoclopramide has an effect on feeding intolerance when compared with no prokinetic use in intensive care patients.

Sources: Nursal, 2007. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain whether prokinetics (metoclopramide and erythromycin) have an effect on the percentage of nutrition goal met when compared with no prokinetic use in intensive care patients.

Source: Berne, 2002; Makkar, 2016. |

|

Low GRADE |

Erythromycin may increase successful postpyloric feeding tube placement when compared with no prokinetic use in intensive care patients.

Sources: Griffith, 2003; Heiselman, 1995; Hu, 2015; Kalliafas, 1996; Paz, 1996; Whatley, 1984. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain whether metoclopramide has an effect on successful postpyloric feeding tube placement when compared with no prokinetic use in intensive care patients.

Sources: Heiselman, 1995; Hu, 2015; Paz, 1996; Whatley, 1984. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain whether prokinetics (metoclopramide and erythromycin) have an effect on mortality compared to no prokinetic use in intensive care patients.

Sources: Berne, 2002; Griffith, 2003; Heiselman, 1995; Hu, 2015; Kalliafas, 1996; Makkar, 2016; Nassaji, 2010; Nursal, 2007; Paz, 1996; Reignier, 2002; Vijayaraghavan, 2021; Whatley, 1984; Yavagal, 2000. |

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain whether prokinetics (metoclopramide and erythromycin) have an effect on pneumonia compared to no prokinetic use in intensive care patients.

Sources: Berne, 2002; Nassaji, 2010; Nursal, 2007; Reignier, 2002; Yavagal, 2000. |

|

Low GRADE

|

Erythromycin may result in little to no difference in length of hospital stay when compared with no prokinetic use in intensive care patients.

Sources: Berne, 2002. |

|

Metoclopramide may slightly reduce length of hospital stay when compared with no prokinetic use in intensive care patients.

Sources: Nassaji, 2010; Nursal, 2007. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Thirteen RCTs were included comparing one or more prokinetic with placebo or no intervention. Where possible, results were described or analyses separately for erythromycin and metoclopramide. Table 1 provides an overview of the characteristics of the included studies.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies.

|

Author (year) |

Country |

Details of participants |

Goal of intervention |

Intervention |

Control |

N |

|

Berne (2002) |

USA |

Critical patients who received gastric feedings within 72 hours of admission and failed to tolerate feedings at 48 hours (gastric residual > 150 mL) |

Improving gastric motility |

Erythromycin 250 mg iv q6h |

Placebo |

I: 32 C: 36 |

|

Griffith (2003) |

USA |

Critically ill patients requiring enteral nutrition and exhibiting one or more of: evidence of delayed gastric emptying with repeatedly high gastric aspirates, history of pulmonary aspiration of tube feeds, clinical high risk of aspiration, head-of-the-bed elevation not possible, or severe acute pulmonary disease |

Facilitating active bedside placement of feeding tubes into the small bowel |

Erythromycin 500 mg IV single dose |

Placebo |

I: 14 C: 22 |

|

Heiselman (1995) |

USA |

Critically ill patients who required enteral nutrition |

Facilitating immediate transpyloric passage of a small-bore feeding tube |

Metoclopramide 10 mg IV single dose |

No medication |

I: 59 C: 46 |

|

Hu (2015) |

China |

Critically ill patients who required enteral nutrition for more than 3 days with |

Facilitating post-pyloric placement of spiral nasojejunal tubes |

1) Metoclopramide 20 mg IV single dose 2) Domperidone 20 mg QID1 |

No intervention |

I: 1002 I: 991,3 C: 99 |

|

Kalliafas (1996) |

USA |

Surgical ICU patients who required enteral nutrition |

Facilitating passage of a nasoenteric feeding tube into the duodenum for postpyloric feedings |

Erythromycin 200 mg iv single dose |

Placebo |

I: 31 C: 26 |

|

Makkar (2016) |

India |

Traumatic brain injury patients with Glasgow coma score of more than 5 admitted to trauma ICU within 72 h |

Improving gastric aspirate volume |

1) Metoclopramide 10 mg q8h 2) Erythromycin 250 mg q8h |

Placebo |

I: 392 I: 384 C: 38 |

|

Nassaji (2010) |

Islamic Republic of Iran |

Surgical ICU patients requiring placement of a nasogastric tube for more than 24 hours |

Preventing nosocomial pneumonia |

Metoclopramide 10 mg PO q8h × 5 days |

No intervention |

I: 68 C: 152 |

|

Nursal (2007) |

Turkey |

Traumatic brain injury patients admitted to the hospital within 48 hours with an initial Glasgow Coma Scale score of 3–11 |

Efficacy on gastric emptying |

Metoclopramide 10 mg iv TID × 5 days |

Placebo |

I: 10 C: 9 |

|

Paz (1996) |

USA |

Critically ill patients who required enteral nutrition in medical and surgical ICU |

Increasing successful feeding tube placement into the small bowel |

1) Metoclopramide 10 mg iv single dose 2) Erythromycin 200 mg iv single dose |

Placebo |

I: 202 I: 214 C: 16 |

|

Reignier (2002) |

France |

Critical patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation and early nutritional support for > 5 days |

Facilitating early EN |

Erythromycin 250 mg iv q6h × 5 days |

Placebo |

I: 20 C: 20 |

|

Vijayaraghavan (2021) |

India |

Critically ill cirrhotic patients in a liver ICU who developed feed intolerance |

Reversal of feeding intolerance |

1) Metoclopramide 10 mg iv single dose 2) Erythromycin 70 mg iv single dose |

Placebo |

I: 282 I: 274 C: 28 |

|

Whatley (1984) |

USA |

Critically ill patients who failed post-pyloric tube insertion |

Facilitating the passage of nasally inserted weighed feeding tubes |

Metoclopramide 20 mg iv single dose |

No intervention |

I: 5 C: 5 |

|

Yavagal (2000) |

India |

Critical patients requiring placement of a nasogastric tube for >24 hrs |

Preventing nosocomial pneumonia |

Metoclopramide 10 mg q8h |

Placebo |

I: 131 C: 174 |

1 Intervention not included in this analysis, 2 number of patients in the metoclopramide group, 3 number of patients in the domperidone group, 4 number of patients in the erythromycin group

EN, enteral nutrition; ICU, intensive care unit; IV, intravenous; PO, per os (oral); QID, quater in die (four times a day); TID, ter in die (three times a day); USA, United States of America.

Results

- Feeding intolerance

The incidence of feeding intolerance was reported by three studies. The definition of feeding intolerance varied significantly between studies. Therefore, the data could not be pooled. Table 2 gives an overview of the incidence of feeding intolerance. For erythromycin, using the prokinetic agent was superior to the control. For metoclopramide, using the prokinetic agent is not superior to the control.

Table 2. Effect of prokinetics on feeding intolerance.

|

Author, year |

Definition feeding intolerance |

Incidence of feeding intolerance |

|

||

|

Intervention, n (%) |

Control, |

RR (95% CI) |

|

||

|

Erythromycin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Berne, 2002 |

GRV exceeded 150 mL |

13/32 (40.6%) |

20/36 (55.6%) |

0.73 (0.44, 1.22) |

|

|

Reignier, 2002 |

6-hr GRV exceeded 250 mL or the patient vomited |

7/20 (35%) |

14/20 (70%) |

0.50 (0.26, 0.97) |

|

|

Metoclopramide |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nursal, 2007 |

Abdominal distension, vomiting, or diarrhea resulting in a decreased feeding infusion rate or cessation of infusion |

4/10 (40%) |

2/9 (22.2%) |

1.80 (0.43, 7.59) |

|

CI, confidence interval; GRV, gastric residual volume; RR, relative risk

- Percentage nutrition goal met

Two studies reported the percentage of total nutrition goal met. Data obtained was too limited to pool the results.

Berne (2002) found a mean of 65% in the erythromycin group and 59% in the placebo group (P=0.061).

Makkar (2016) reported that in the metoclopramide group 83.16% (SD 16.25%) of target calories were met, 90.13% (SD 15.88%) in the erythromycin group and 80.42% (SD 19.78%) in the placebo group.

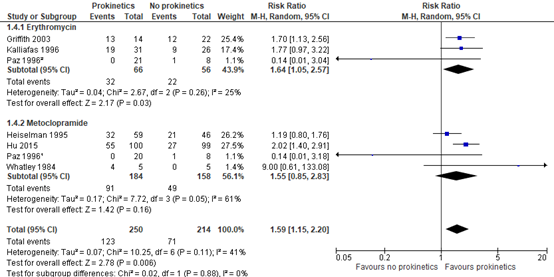

- Successful post-pyloric feeding tube placement

Six studies reported successful post-pyloric feeding tube placement. As shown in figure 1, the pooled risk ratio (RR) of 1.59 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.15 to 2.20). This difference was considered clinically relevant in favor of prokinetic use. In the erythromycin subgroup, a RR of 1.64 (95% CI 1.05 to 2.57) was found and in the metoclopramide subgroup, a RR of 1.55 (0.85 to 2.83) was found. Both were in favor of prokinetic use and clinically relevant differences.

Figure 1. Effect of prokinetic agents on successful post-pyloric feeding tube placement.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

1 Metoclopramide vs. placebo

2 Erythromycin vs. placebo

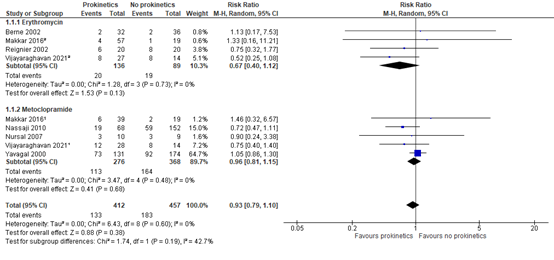

- Mortality

Seven studies reported mortality rates. As shown in figure 2, the pooled RR was 0.93 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.10). In the subgroup analysis, we found a RR of 0.67 (95% CI 0.40 to 1.12) in favor of erythromycin and a RR of 0.96 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.15) in favor of metoclopramide.

Figure 2. Effect of prokinetic agents on mortality.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

1 Metoclopramide vs. placebo

2 Erythromycin vs. placebo

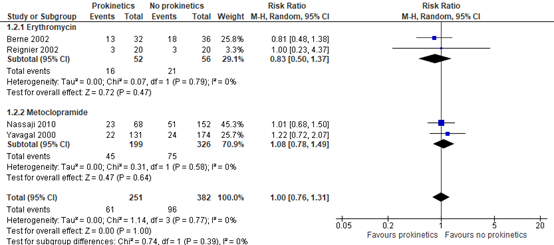

- Pneumonia

The incidence rate of pneumonia was obtained from four studies. All pneumonia was ICU acquired. As shown in figure 3, the pooled RR was 1.00 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.31).

Figure 3. Effect of prokinetic agents on the incidence of pneumonia.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

- Length of hospital stay

The effect of prokinetics on length of hospital stay was reported in three studies. Due to limited data, no pooled result was obtained.

Berne (2002) reported mean hospital days, as well. The group receiving erythromycin had a stay of 25.5 days and the placebo group 22.2 days.

Nassaji (2010) reported mean hospitalization for both groups. The group receiving metoclopramide had a length of hospital stay of 9.0 days, while the no metoclopramide group had a mean stay of 10.5 days.

Nursal (2007) reported mean and standard deviations of hospital days. In the metoclopramide group, the mean was 15.6 (SD 11.1) days and in the control group 16.8 (SD 8.5) days.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for all outcome measures started as high, as the included studies were RCTs.

For erythromycin, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure feeding intolerance was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1), and imprecision (-1). The level of evidence for feeding intolerance is low.

For metoclopramide, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure feeding intolerance was downgraded by 3 levels because of imprecision (-3), since only one study was included. The level of evidence for feeding intolerance is very low.

For erythromycin and metoclopramide, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure percentage nutrition goal met was downgraded by 3 levels because of imprecision (-3), since only one study was included. The level of evidence is very low.

For erythromycin, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure successful post-pyloric feeding tube placement was downgraded by 2 levels because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1) and imprecision due to wide confidence intervals (-1). The level of evidence is low.

For metoclopramide, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure successful post-pyloric feeding tube placement was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding and industry sponsoring, -1), conflicting results (inconsistency, -1) and imprecision due to wide confidence intervals (-2). The level of evidence for successful post-pyloric feeding tube placement is very low.

For erythromycin and metoclopramide, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1), conflicting results (inconsistency, -1), and imprecision due to wide confidence intervals (-2). The level of evidence for mortality is very low.

For erythromycin and metoclopramide, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pneumonia was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to lack of blinding, -1) and imprecision due to wide confidence intervals (-2). The level of evidence for pneumonia is very low.

For erythromycin and metoclopramide, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure length of hospital stay was downgraded by 2 levels because of imprecision (-2), because a limited number of studies with few patients were included. The level of evidence for length of hospital stay is low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness of prokinetics in intensive care unit (ICU) patients on feeding intolerance (and other outcomes as defined in the PICO)?

| P: (patients) | ICU patients receiving enteral nutrition |

| I: (intervention) | Erythromycin, Metoclopramide |

| C: (control) | No prokinetics (placebo, no intervention) |

| O: (outcome measure) | Feeding intolerance, percentage nutrition goal met, successful post-pyloric feeding tube placement, mortality, pneumonia, length of hospital stay |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered feeding intolerance as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and percentage nutrition goal met, successful post-pyloric feeding tube placement, mortality, pneumonia and length of hospital stay, as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

Feeding intolerance, successful post-pyloric feeding tube placement: as defined in the RCTs

The working group defined the following values as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference. For feeding intolerance, percentage nutrition goal met, successful post-pyloric feeding tube placement and pneumonia, a difference of 10% was considered clinically relevant (RR ≤ 0.91 or ≥ 1.10). For mortality a difference of 5% was considered clinically relevant (RR ≤ 0.95 or ≥ 1.05). For length of hospital stay, a difference of 1 day was considered clinically relevant.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 15-11-2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 270 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria RCTs or systematic reviews of RCTs investigating the efficacy and effectiveness of erythromycin or metoclopramide for patients admitted to the ICU. Fifty-two studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 24 were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and three studies were included.

Results

Three systematic reviews were included in the analysis of the literature (Peng, 2021; Lewis, 2016; Silva, 2015). Since we reported additional outcome measures beyond Peng (2021), Lewis (2016) and Silva (2015), the individual RCTs were included that fit the inclusion criteria. This resulted in thirteen RCTs. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Aboumarzouk OM, Agarwal T, Antakia R, Shariff U, Nelson RL. Cisapride for intestinal constipation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jan 19;(1):CD007780. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007780.pub2. PMID: 21249695.

- Berne JD, Norwood SH, McAuley CE, Vallina VL, Villareal D, Weston J, McClarty J. Erythromycin reduces delayed gastric emptying in critically ill trauma patients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Trauma. 2002 Sep;53(3):422-5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200209000-00004. PMID: 12352474.

- Griffith DP, McNally AT, Battey CH, Forte SS, Cacciatore AM, Szeszycki EE, Bergman GF, Furr CE, Murphy FB, Galloway JR, Ziegler TR. Intravenous erythromycin facilitates bedside placement of postpyloric feeding tubes in critically ill adults: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Crit Care Med. 2003 Jan;31(1):39-44. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301000-00006. PMID: 12544991.

- Heiselman DE, Hofer T, Vidovich RR. Enteral feeding tube placement success with intravenous metoclopramide administration in ICU patients. Chest. 1995 Jun;107(6):1686-8. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.6.1686. PMID: 7781368.

- Hu B, Ye H, Sun C, Zhang Y, Lao Z, Wu F, Liu Z, Huang L, Qu C, Xian L, Wu H, Jiao Y, Liu J, Cai J, Chen W, Nie Z, Liu Z, Chen C. Metoclopramide or domperidone improves post-pyloric placement of spiral nasojejunal tubes in critically ill patients: a prospective, multicenter, open-label, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Crit Care. 2015 Feb 13;19(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0784-1. PMID: 25880172; PMCID: PMC4367875.

- Kalliafas S, Choban PS, Ziegler D, Drago S, Flancbaum L. Erythromycin facilitates postpyloric placement of nasoduodenal feeding tubes in intensive care unit patients: randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1996 Nov-Dec;20(6):385-8. doi: 10.1177/0148607196020006385. PMID: 8950737.

- Lewis K, Alqahtani Z, Mcintyre L, Almenawer S, Alshamsi F, Rhodes A, Evans L, Angus DC, Alhazzani W. The efficacy and safety of prokinetic agents in critically ill patients receiving enteral nutrition: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care. 2016 Aug 15;20(1):259. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1441-z. PMID: 27527069; PMCID: PMC4986344.

- Makkar JK, Gauli B, Jain K, Jain D, Batra YK. Comparison of erythromycin versus metoclopramide for gastric feeding intolerance in patients with traumatic brain injury: A randomized double-blind study. Saudi J Anaesth. 2016 Jul-Sep;10(3):308-13. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.174902. PMID: 27375386; PMCID: PMC4916815.

- Nassaji M, Ghorbani R, Frozeshfard M, Mesbahian F. Effect of metoclopramide on nosocomial pneumonia in patients with nasogastric feeding in the intensive care unit. East Mediterr Health J. 2010 Apr;16(4):371-4. PMID: 20795418.

- Nursal TZ, Erdogan B, Noyan T, Cekinmez M, Atalay B, Bilgin N. The effect of metoclopramide on gastric emptying in traumatic brain injury. J Clin Neurosci. 2007 Apr;14(4):344-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.11.011. PMID: 17336229.

- Paz HL, Weinar M, Sherman MS. Motility agents for the placement of weighted and unweighted feeding tubes in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 1996 Apr;22(4):301-4. doi: 10.1007/BF01700450. PMID: 8708166.

- Peng R, Li H, Yang L, Zeng L, Yi Q, Xu P, Pan X, Zhang L. The efficacy and safety of prokinetics in critically ill adults receiving gastric feeding tubes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021 Jan 11;16(1):e0245317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245317. PMID: 33428672; PMCID: PMC7799841.

- Reignier J, Bensaid S, Perrin-Gachadoat D, Burdin M, Boiteau R, Tenaillon A. Erythromycin and early enteral nutrition in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2002 Jun;30(6):1237-41. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200206000-00012. PMID: 12072674.

- Silva CC, Bennett C, Saconato H, Atallah ÁN. Metoclopramide for post-pyloric placement of naso-enteral feeding tubes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 7;1(1):CD003353. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003353.pub2. PMID: 25564770; PMCID: PMC7170214.

- Vijayaraghavan R, Maiwall R, Arora V, Choudhary A, Benjamin J, Aggarwal P, Jamwal KD, Kumar G, Joshi YK, Sarin SK. Reversal of Feed Intolerance by Prokinetics Improves Survival in Critically Ill Cirrhosis Patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Aug 14:1-11. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-07185-x. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34392492; PMCID: PMC8364303.

- Whatley K, Turner WW Jr, Dey M, Leonard J, Guthrie M. When does metoclopramide facilitate transpyloric intubation? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1984 Nov-Dec;8(6):679-81. doi: 10.1177/0148607184008006679. PMID: 6441010.

- Yavagal DR, Karnad DR, Oak JL. Metoclopramide for preventing pneumonia in critically ill patients receiving enteral tube feeding: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2000 May;28(5):1408-11. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200005000-00025. PMID: 10834687.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Yavagal, 2000 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: ICU of a university hospital in India

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: nasogastric tube for >24 hrs

Exclusion criteria: pneumonia or who had a nasogastric tube placed before ICU admission

N total at baseline: Intervention: 131 Control: 174

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 38.1 (17.4) C: 34.8 (15.2)

Sex: I: 79/131 M C: 110/174 M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Metoclopramide 10 mg NG q8h; |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Placebo |

Length of follow-up: Until death, ICU discharge or ng tube removal or development of nosocomial pneumonia

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Nosocomial pneumonia I: 22/131 C: 24/174

Mortality I: 56% C: 53% |

Author’s conclusion Metoclopramide in the dose of 10 mg every 8 hrs did not reduce the risk of nosocomial pneumonia in ICU patients receiving nasogastric tube feeds. Although it delayed the onset of pneumonia by 1.5 days, this is of little clinical significance because it did not have any effect on the mortality rate or the length of ICU stay. |

|

Makkar, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: India

Funding and conflicts of interest: None |

Inclusion criteria: TBI patients with Glasgow coma score (GCS) of more than 5 admitted to trauma intensive care within 72 h of injury

Exclusion criteria: blunt trauma abdomen, severe thoracic injury with associated hemothorax, allergy to macrolide or metoclopramide, abnormal liver function, and renal dysfunction

N total at baseline: Intervention 1: 39 I2: 38 Control: 38

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I1: 37.26±16.2 I2: 34.92±13.6 C: 39.03±14.5

Sex: I1: 34/39 M I2: 33/38 M C: 32/38 M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

1) Metoclopramide 10 mg 2) Erythromycin 250 mg

Every 8 hours for 5 days through NG tube |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Placebo

Every 8 hours for 5 days through NG tube |

Length of follow-up: 5 days

Loss-to-follow-up: I1: N=2 (5%) Reasons: protocol deviation

I2: N= 3 (7.3%) Reasons: protocol deviation

Control: N=2 (4.9%) Reasons: protocol deviation

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality I1: 6/39 I2: 4/38 C: 3/38

Target calories met mean%, SD I2: 90.13 ± 15.88 C: 80.42 ± 19.78

|

Author’s conclusion The incidence of high GAV in TBI patients was 60.5%, and there was a significant decrease in the incidence of high GRV with the use of erythromycin when compared to metoclopramide and placebo. The combination of erythromycin and metoclopramide was associated with acceptance of greater percentage of target calories in the control group

|

|

Reignier, 2002 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: France

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: require mechanical ventilation and early nutritional support for >5 days

Exclusion criteria: treatment with erythromycin within 48 hrs before ICU admission; pregnancy; diabetes mellitus; current acute pancreatitis, bleeding from the stomach or esophageal varices; facial trauma; a history of esophageal or gastric surgery; intolerance or sensitivity to erythromycin; or a need for droperidol, a tricyclic antidepressant, cisapride, atropine, or metoclopramide

N total at baseline: Intervention: 25 Control:23

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 70 ± 2 C: 66 ± 3

Sex: I: 9/20 M C: 11/20 M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Erythromycin 250 mg in 50 mL of 5% dextrose (i.v.) given at 6-hr intervals for 5 days

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Placebo |

Length of follow-up: 5 days

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=5 (20%) Reasons: no MV for >5 days

Control: N=3 (13%) Reasons: no MV for >5 days

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality I: 30% C: 40%

Vomiting I: 0/20 C: 3/20

Pneumonia I: 3/20 C: 3/20

Feeding intolerance (defined as: 6-hr GRV > 250 mL or if the patient vomited) I: 7/20 C: 14/20 |

Author’s conclusion In critically ill patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation, erythromycin promotes gastric emptying and improves the chances of successful early enteral nutrition. |

|

Nursal 2007 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: sustained TBI and had been admitted to the hospital within 48 hours with an initial Glasgow Coma Scale score of 3–11

Exclusion criteria: additional abdominal and pelvic injuries, severe thoracic injuries with hemo/pneumothorax who required chest-tube drainage or surgery

N total at baseline: Intervention: 10 Control:10

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 43.8 (24.5) C: 43.0 (18.5)

Sex: I: 8/10 M C: 8/9 M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Metoclopramide 10 mg iv, 3x daily for 5 days

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Saline |

Length of follow-up: 5 days

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=0

Control: N=1 (10%) Reasons: protocol violation

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality I: 3/10 C:3/9

Vomiting I: 1/10 C:2/9

Diarrhea I: 1/10 C: 1/9

Feeding intolerance (defined as abdominal distension, vomiting, or diarrhea resulting in a decreased feeding infusion rate or cessation of infusion) I: 4/10 C: 2/9

Length of hospital stay (days) mean (SD) I: 15.6 (11.1) C: 16.8 (8.5)

|

Author’s conclusion We do not suggest use of metoclopramide as an aid to enteral nutrition in TBI patients. Simple intragastric enteral feeding, with close monitoring for possible complications, seems to be sufficient, with acceptable morbidity rates |

|

Berne 2002 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: critically injured patients who received intragastric tube feedings within 72 hours of admission and failure to tolerate feedings at any time during the first 48 hours, as determined by a GRV > 150 mL

Exclusion criteria: age < 17 years; pregnancy; contraindication to use of erythromycin, specifically, concomitant use of drugs known to interact with erythromycin (warfarin, cyclosporine, theophylline, carbamazepine, or digoxin); known allergic reaction to erythromycin or macrolide antibiotics; use of a prokinetic agent within the prior 2 weeks; or evidence of severe liver dysfunction

N total at baseline: Intervention: 32 Control:36

Important prognostic factors2: age: I: 40.0 C: 34.1

Sex: I: 21/32 M C: 23/36 M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

250 mg erythromycin iv every 6 hours

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Placebo |

Length of follow-up: 48 hours (% total nutrition goal, feeding intolerance) Until discharge/death (VAP, mortality, hospital days)

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality I: 2/32 C: 2/36

% total nutrition goal met I: 65 C: 59

Hospital days I: 25.5 C: 22.2

VAP I: 13/32 C: 18/36

Feeding intolerance (defined as GRV > 150 mL) I: 13/32 C: 20/36 |

Author’s conclusion Intravenous erythromycin reduces delayed gastric emptying in critically ill trauma patients during the first 48 hours. The use of eythromycin in trauma patients does not affect the rate of nosocomial infection. |

|

Nassaji 2010 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Surgical ICU in Islamic Republic of Iran

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: Admitted to the ICU and required nasogastric tube feeding for more than 24 hours

Exclusion criteria: Those s who already had pneumonia, had received a nasogastric tube before ICU admission or who were discharged or died within 48 hours after admission

N total at baseline: Intervention: 68 Control: 152

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: s 41.5 (23.9) C: 46.4 (24.8)

Sex: I: 49/68 M C: 95/152 M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

metoclopramide 10 mg every 8 hours through NG tube (max. 5 days)

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

No metoclopramide |

Length of follow-up: Until ICU discharge or death

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pneumonia I: 23/68 C: 51/152

Mortality I: 23/68 C: 51/152

Hospitalization, mean I: 9.0 C: 10.5 |

Author’s conclusion oral metoclopramide in the dose used in this study (10 mg every 8 hours) did not reduce the risk of developing NP in ICU patients with nasogastric feeding. |

|

Vijayaraghavan 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Critically ill cirrhotic patients in a liver ICU in India

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria Patients of chronic liver disease and of age ≥ 18 and ≤ 70 years who were admitted in ICU, patients with cirrhosis, with decompensation, and with acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF), as defined by Asia Pacific association for the study of the liver (APASL) definition were enrolled

Exclusion criteria Patients who were requiring dual vasopressor, on high vasopressors (> 0.64 mcg/kg/min), uncontrolled sepsis, DIC, and patients with GI bleed at the time of development of feed intolerance, have current or past history of surgical abdomen, including mechanical obstruction, mesenteric ischemia, perforation or requiring abdominal surgery, patients receiving nutrition through gastrostomy or feeding jejunostomy, prior comorbid illnesses like advanced cardiopulmonary disease, prior episodes of arrhythmia, structural heart diseases, traumatic brain injury, cerebrovascular accidents, raised intracranial pressures, history of myasthenia gravis, endocrinological illnesses like uncontrolled hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism, previously diagnosed diabetic gastroparesis, connective tissue disorders including systemic sclerosis, dermatomyositis or polymyositis, systemic lupus erythematosus, amyloidosis were excluded. Patients were excluded if they had received prokinetic medication during ICU stay or were allergic to metoclopramide or erythromycin, pregnant and refusal to give consent.

N total at baseline: I1: 28 I2: 27 C: 28

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I1: 46.4 ± 11.01 I2: 46.3 ± 14.04 C: 45.7 ± 12.3

Sex: I1: 82% M I2: 85% M C: 64% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

1. metoclopromide 10 mg iv every 8 hours 2. erythromycin 70 mg iv every 12 hours |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Placebo |

Length of follow-up: Until death or ICU discharge (max. 7 days)

Loss-to-follow-up: I1: 0 I2: 0 C: 0

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality I1: 12/28 I2: 8/27 C: 16/28 |

Author’s conclusion Early detection and the addition of prokinetics facilitate the resolution of feeding intolerance in critically ill cirrhotic patients. Erythromycin is safe and superior to metoclopramide for early resolution of gut paralysis in critically ill cirrhotic patients.

Critical note: Only patients with high (>500 mL) GRV were randomized, which may have been reflected in high mortality rates |

|

Griffith 2003 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Adult patients requiring enteral tube feeding admitted to the medical or surgical ICUs of Emory University Hospital, USA.

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported

|

Inclusion criteria Patients who exhibited one or more of the following indications for postpyloric feeding: evidence of delayed gastric emptying with repeatedly high gastric aspirates; history of pulmonary aspiration of tube feeds or clinical high risk for aspiration; severe acute pulmonary disease; or head elevation not possible (e.g., orthopedic patients)

Exclusion criteria history of allergy to erythromycin; current administration of prokinetic drugs; current hemodynamic instability, with or without pressor agents; active gastrointestinal bleeding or recently active gastric or esophageal varices; severe thrombocytopenia; gastric outlet or intestinal obstruction; history of gastric surgery; agitation; or requirement for face mask oxygen delivery.

N total at baseline: I: 14 C: 22

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 54.6 ± 3.4 C: 59.7 ± 3.8

Sex: I: 79% M C: 64% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

100-mL intravenous infusion of erythromycin mixed in normal saline |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Placebo (100-mL intravenous infusion of normal saline) |

Length of follow-up: Not reported Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Successful postpyloric feeding tube placement: I: 13/14 C: 12/22 |

Author’s conclusion A single bolus dose of intravenous erythromycin facilitates active bedside placement of postpyloric feeding tubes in critically ill adult patients.

|

|

Heiselman 1995 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: medical and surgical ICU patients at a community teaching hospital, USA.

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported

|

Inclusion criteria 1) admission to the critical care unit, (2) the need for enteral nutrition, and (3) an age of at least 18 years

Exclusion criteria 1) upper GI hemorrhage, gastric malignancy, pheochromocytoma, gastroparesis, gastric outlet obstruction, or active GI disease affecting normal upper tract anatomy or motility; 2) surgery for peptic ulcer disease, vagotomy, or surgery affecting normal upper tract anatomy or motility; 3) prescriptions for metoclopramide, MAO inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, sympathomimetic amines, terbutaline sulfate, norepinephrine bitartrate, isoproterenol hydrochloride, albuterol, or medications which interact with metoclopramide; and 4) known adverse reactions to metoclopramide

N total at baseline: I: 59 C: 46

Important prognostic factors2: No baseline characteristics of included patients described

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

10 mg of metoclopramide IV |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

no medication |

Length of follow-up: Not reported

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Successful postpyloric feeding tube placement: I: 32/59 C: 21/46 |

Author’s conclusion Intravenous metoclopramide, 10 mg, administered 10 min prior to intubation with a small-bore feeding tube (10F), was ineffective in facilitating transpyloric intubation.

Critical note: Baseline characteristics of included patients were not described. |

|

Hu 2015 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: ICUs of seven university hospitals, China

Funding and conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interest reported, Nutricia provided spiral nasojejunal tubes and supporting this study partly. |

Inclusion criteria patients admitted to the ICU; age ≥18 years; and requiring enteral nutrition for more than 3 days.

Exclusion criteria history of percutaneous gastrostomy or gastrojejunostomy; intubation intolerance; esophageal varices or strictures; previous major gastroesophageal surgery (for example, esophagectomy or gastrectomy); pregnant; or history of allergy to metoclopramide, domperidone, or meglumine diatrizoate

N total at baseline: I1: 103 I2: 100 C: 104

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I1: 62.1 ± 18.6 I2: 65.2 ± 15.1 C: 61.3 ± 17.4 Sex: I1: 67.0% M I2: 58.6% M C: 72.7% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

1) 20 mg (or 10 mg in cases of renal insufficiency) metoclopramide intravenously 2) 20 mg domperidone ( × 4/day) was administered by the tube |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

No intervention

|

Length of follow-up: 24h

Loss-to-follow-up: I1: 0 I2: 0 C: 0

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Successful postpyloric feeding tube placement: I1: 55/100 I2: 51/99 C: 27/99 |

Author’s conclusion Prokinetic agents, such as metoclopramide or domperidone, are effective at improving the success rate of post-pyloric placement of spiral nasojejunal tubes in critically ill patients.

Critical note: Healthcare providers could not be blinded due to the absence of a placebo with an identical appearance to domperidone suspension, and because of the different dosing regimen of the two drugs |

|

Kalliafas 1996 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: surgical intensive care units of The Ohio State University Hospitals, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria All patients admitted to the surgical ICU who required enteral nutrition

Exclusion criteria Pregnant women, minors (less than 18 years old), prisoners, and patients with known allergic reactions to erythromycin

N total at baseline: I: 31 C: 26

Important prognostic factors2: Age (range): I: 54.7 (19-84) C: 57.3 (19-84)

Sex: I: 58.1% M C: 46.2% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

200 mg erythromycin intravenously |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Placebo |

Length of follow-up: Not reported

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Successful postpyloric feeding tube placement: I: 19/31 C: 9/26 |

Author’s conclusion

Overall, erythromycin is effective in facilitating placement of a nasoenteric feeding tube into the duodenum in ICU patients. It is clearly beneficial in those patients with normal mental status and may be useful in patients with diabetes mellitus. |

|

Paz 1996 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: medical and surgical acute and intermediate critical care services at Hahnemann University Hospital, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Supported in part by a gift from Ross laboratories

|

Inclusion criteria requiring enteral nutritional support

Exclusion criteria unconscious or too ill to provide informed consent

N total at baseline: I1: 21 I2: 20 C1: 26 C2: 16

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I1: 58.9 ± 18.6 I2: 58.8 ± 21.0 C1: 57.0 ± 17.6 C2: 68.4 ± 15.9

Sex: I1: 61.9% M I2: 40% M C1: 46.2% M C2: 68.8% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

15 min prior to passage of a weighted 10-french "Flexiflo" feeding tube

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

|

Length of follow-up: 24 h

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Successful postpyloric feeding tube placement: I1: 0/21 I2: 0/20 C1: 3/26 C2: 2/16 |

Author’s conclusion

Weighted enteral feeding tubes are preferred because they can be intubated into the stomach with less difficulty. Neither metoclopramide nor erythromycin was effective in improving transpyloric placement of the feeding tubes, and indeed may hinder duodenal intubation. |

|

Whatley 1984 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: ICU (including e Surgical Intensive Care or Neurosurgical Units), USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria patients had failed to achieve spontaneous duodenal intubation within 24 hrs

Exclusion criteria -

N total at baseline: I: 5 C:5

Important prognostic factors2: Not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? Unknown

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

20 mg of metoclopramide intravenously |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

No premedication |

Length of follow-up: 24 hrs

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Successful postpyloric feeding tube placement: I: 4/5 C: 0/5

|

Author’s conclusion Metoclopramide, administered after nasogastric intubation, is ineffective in promoting transpyloric advancement of weighted feeding tubes. There is a significant increase in transpyloric intubation when metoclopramide is administered prior to weighed feeding tube insertion.

|

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Yavagal, 2000 |

Probably no;

Reason: randomization method is not discussed |

Probably no;

Reason: not specified |

Probably yes;

Reason: double-blinded study, with blinding of patients and one other group. Unsure whether that is healthcare providers or outcome assessors |

Probably yes

Reason: no loss to follow-up reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality) Unknown randomization method |

|

Nursal, 2007 |

Probably yes;

Reason: separated by blocked rank randomization into two groups. Details are lacking. |

Probably yes; Reason: not specified but no indications of the problems with concealment. |

Probably yes

Reason: Patients, health care providers, outcome assessors are blinded (data collectors and analysts were not discussed) |

Probably yes

Reason: loss to follow-up was only present in the control group and was infrequent |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

Makkar, 2016 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization with computer generated random numbers |

Probably yes;

Reason: not specified but no indications of the problems with concealment. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Patients, health care providers, outcome assessors and data collectors are blinded |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. Authors anticipated to possible dropouts beforehand. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

Reignier, 2002 |

Probably yes;

Reason: sealed envelope randomization procedure |

Probably yes;

Reason: not specified but no indications of the problems with concealment |

Probably no;

Reason: Patients were blinded, health care providers and data collectors were not |

Probably yes

Reason: loss to follow-up was infrequent in both groups. Unknown whether power is sufficient. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality)

Lack of blinding |

|

Berne 2002 |

Probably no;

Reason: randomization method is not discussed |

Probably no;

Reason: allocation concealment is not discussed |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Patients, health care providers, outcome assessors and data collectors are blinded |

Probably yes

Reason: no loss to follow-up reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality)

Unknown randomization method |

|

Nassaji 2010 |

Probably no;

Reason: generation of allocation sequences by alternation |

Probably no;

Reason: not discussed and inadequate randomization method |

Probably yes;

Reason: double-blinded study, with blinding of patients and data collectors. Unsure whether that is healthcare providers or outcome assessors |

Probably yes

Reason: no loss to follow-up reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality)

Inadequate randomization |

|

Acosta-Escribano 2014 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization with computer generated random numbers |

Probably yes;

Reason: not specified but no indications of the problems with concealment. |

Probably yes;

Reason: blinding of patients and one other group. Unsure whether that is healthcare providers or outcome assessors |

Probably no;

Reason: equal loss to follow-up in both groups, but power of the control group is insufficient |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted

|

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality)

Loss to follow-up |

|

Vijayaraghavan 2021 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: randomization using computer generated block randomization with a block size of 15 |

Definitely yes:

Reason: Allocation concealment using sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelope (SNOSE) technique |

Definitely no

Reason: this is an open-label study |

Definitely yes

Reason: No loss to follow-up occurred |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted

|

HIGH (all outcomes except mortality)

Lack of blinding |

|

Griffith 2003 |

Probably no;

Reason: study is randomized, but randomization method is not discussed |

Probably no;

Reason: allocation concealment is not discussed |

Probably yes;

Reason: study was double-blinded (patients and healthcare providers). |

Probably yes

Reason: no loss to follow-up reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted

|

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality)

Unknown randomization method |

|

Heiselman 1995 |

Probably no;

Reason: study is randomized, but randomization method is not discussed |

Probably no;

Reason: allocation concealment is not discussed |

Probably no;

Reason: blinding was not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: no loss to follow-up reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted

|

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality)

Unknown randomization method and blinding |

|

Hu 2015 |

Probably no;

Reason: study is randomized by fixed block randomization, no additional details described |

Probably no;

Reason: allocation concealment is not discussed |

Definitely no

Reason: only the patients and the data analyst were blinded |

Definitely yes

Reason: No loss to follow-up occurred |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably no;

Reason: Sponsoring by industry (Nutricia)

|

HIGH (all outcomes except mortality)

Lack of blinding, industry sponsoring |

|

Kalliafas 1996 |

Probably yes;

Reason: stratified randomization, details are lacking |

Probably yes;

Reason: allocation concealment is not discussed |

Probably yes

Reason: study was double-blinded but no details were provided |

Probably yes

Reason: no loss to follow-up reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted

|

LOW

|

|

Paz 1996 |

Probably yes;

Reason: randomization by a random number table |

Probably yes;

Reason: allocation concealment is not discussed |

Probably yes;

Reason: patients and healthcare providers were blinded to the investigational drug. |

Probably yes

Reason: no loss to follow-up reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted

|

LOW |

|

Whatley 1984 |

Probably yes;

Reason: randomization by a random number table |

Probably yes;

Reason: allocation concealment is not discussed |

Probably no;

Reason: blinding was not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: no loss to follow-up reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted

|

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality)

Lack of blinding |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Traverso LW, Hashimoto Y. Delayed gastric emptying: the state of the highest level of evidence. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15(3):262-9. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1304-8. Epub 2008 Jun 6. PMID: 18535763. |

Wrong intervention |

|

Hiyama T, Yoshihara M, Tanaka S, Haruma K, Chayama K. Effectiveness of prokinetic agents against diseases external to the gastrointestinal tract. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Apr;24(4):537-46. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05780.x. Epub 2009 Feb 12. PMID: 19220673. |

Wrong publication (narrative review) |

|

Koekkoek KW, van Zanten AR. Nutrition in the critically ill patient. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017 Apr;30(2):178-185. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000441. PMID: 28151828. |

Wrong publication (narrative review) |

|

Silva CC, Saconato H, Atallah AN. Metoclopramide for migration of naso-enteral tube. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(4):CD003353. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003353. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD003353. PMID: 12519594. |

Outdated (update in 2015) |

|

Deane AM, Chapman MJ, Abdelhamid YA. Any news from the prokinetic front? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2019 Aug;25(4):349-355. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000634. PMID: 31247631. |

Wrong publication (narrative review) |

|

Tiancha H, Jiyong J, Min Y. How to Promote Bedside Placement of the Postpyloric Feeding Tube: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2015 Jul;39(5):521-30. doi: 10.1177/0148607114546166. Epub 2014 Aug 21. PMID: 25146431. |

Wrong population (not exclusively ICU) |

|

Kattelmann KK, Hise M, Russell M, Charney P, Stokes M, Compher C. Preliminary evidence for a medical nutrition therapy protocol: enteral feedings for critically ill patients. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006 Aug;106(8):1226-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.05.320. PMID: 16863719. |

Wrong publication (narrative review) |

|

Chapman M, Fraser R, de Beaux I, Creed S, Finnis M, Butler R, Cmielewski P, Zacharkis B, Davidson G. Cefazolin does not accelerate gastric emptying in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 2003 Jul;29(7):1169-72. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1803-2. Epub 2003 Jun 12. PMID: 12802484. |

Wrong intervention |

|

Rahat-Dahmardeh A, Saneie-Moghadam S, Khosh-Fetrat M. Comparing the Effect of Neostigmine and Metoclopramide on Gastric Residual Volume of Mechanically Ventilated Patients in Intensive Care Unit: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Biomed Res Int. 2021 Aug 16;2021:5550653. doi: 10.1155/2021/5550653. PMID: 34447851; PMCID: PMC8384548. |

Wrong comparator |

|

Davies AR, Morrison SS, Bailey MJ, Bellomo R, Cooper DJ, Doig GS, Finfer SR, Heyland DK; ENTERIC Study Investigators; ANZICS Clinical Trials Group. A multicenter, randomized controlled trial comparing early nasojejunal with nasogastric nutrition in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2012 Aug;40(8):2342-8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318255d87e. PMID: 22809907. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Charoensareerat T, Bhurayanontachai R, Sitaruno S, Navasakulpong A, Boonpeng A, Lerkiatbundit S, Pattharachayakul S. Efficacy and Safety of Enteral Erythromycin Estolate in Combination With Intravenous Metoclopramide vs Intravenous Metoclopramide Monotherapy in Mechanically Ventilated Patients With Enteral Feeding Intolerance: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Pilot Study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2021 Aug;45(6):1309-1318. doi: 10.1002/jpen.2013. Epub 2020 Oct 2. PMID: 32895971. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Malekolkottab M, Khalili H, Mohammadi M, Ramezani M, Nourian A. Metoclopramide as intermittent and continuous infusions in critically ill patients: a pilot randomized clinical trial. J Comp Eff Res. 2017 Mar;6(2):127-136. doi: 10.2217/cer-2016-0067. Epub 2017 Jan 24. PMID: 28114798. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Nguyen NQ, Chapman M, Fraser RJ, Bryant LK, Burgstad C, Holloway RH. Prokinetic therapy for feed intolerance in critical illness: one drug or two? Crit Care Med. 2007 Nov;35(11):2561-7. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000286397.04815.B1. PMID: 17828038. |

Wrong intervention |

|

Taylor SJ, Allan K, McWilliam H, Manara A, Brown J, Greenwood R, Toher D. A randomised controlled feasibility and proof-of-concept trial in delayed gastric emptying when metoclopramide fails: We should revisit nasointestinal feeding versus dual prokinetic treatment: Achieving goal nutrition in critical illness and delayed gastric emptying: Trial of nasointestinal feeding versus nasogastric feeding plus prokinetics. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2016 Aug;14:1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2016.04.020. Epub 2016 May 31. PMID: 28531392. |

Wrong intervention |

|

Sustić A, Zelić M, Protić A, Zupan Z, Simić O, Desa K. Metoclopramide improves gastric but not gallbladder emptying in cardiac surgery patients with early intragastric enteral feeding: randomized controlled trial. Croat Med J. 2005 Apr;46(2):239-44. PMID: 15849845. |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Deane AM, Wong GL, Horowitz M, Zaknic AV, Summers MJ, Di Bartolomeo AE, Sim JA, Maddox AF, Bellon MS, Rayner CK, Chapman MJ, Fraser RJ. Randomized double-blind crossover study to determine the effects of erythromycin on small intestinal nutrient absorption and transit in the critically ill. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012 Jun;95(6):1396-402. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.035691. Epub 2012 May 9. PMID: 22572649. |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Booth CM, Heyland DK, Paterson WG. Gastrointestinal promotility drugs in the critical care setting: a systematic review of the evidence. Crit Care Med. 2002 Jul;30(7):1429-35. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200207000-00005. PMID: 12130957. |

Outdated systematic review |

|

Liu Y, Dong X, Yang S, Wang A, Wang M. Metoclopramide for preventing nosocomial pneumonia in patients fed via nasogastric tubes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2017;26(5):820-828. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.102016.01. PMID: 28802291. |

Wrong population (not exclusively ICU) |

|

Marino LV, Kiratu EM, French S, Nathoo N. To determine the effect of metoclopramide on gastric emptying in severe head injuries: a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Br J Neurosurg. 2003 Feb;17(1):24-8. PMID: 12779198. |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Pinilla JC, Samphire J, Arnold C, Liu L, Thiessen B. Comparison of gastrointestinal tolerance to two enteral feeding protocols in critically ill patients: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2001 Mar-Apr;25(2):81-6. doi: 10.1177/014860710102500281. PMID: 11284474. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Hu B, Ouyang X, Lei L, Sun C, Chi R, Guo J, Guo W, Zhang Y, Li Y, Huang D, Sun H, Nie Z, Yu J, Zhou Y, Wang H, Zhang J, Chen C. Erythromycin versus metoclopramide for post-pyloric spiral nasoenteric tube placement: a randomized non-inferiority trial. Intensive Care Med. 2018 Dec;44(12):2174-2182. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5466-4. Epub 2018 Nov 21. PMID: 30465070; PMCID: PMC6280835. |

Wrong comparison (Erythromycin versus metoclopramide) |

|

Nguyen NQ, Chapman MJ, Fraser RJ, Bryant LK, Holloway RH. Erythromycin is more effective than metoclopramide in the treatment of feed intolerance in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2007 Feb;35(2):483-9. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000253410.36492.E9. PMID: 17205032. |

Wrong comparison (Erythromycin versus metoclopramide) |

|

Hersch M, Krasilnikov V, Helviz Y, Zevin S, Reissman P, Einav S. Prokinetic drugs for gastric emptying in critically ill ventilated patients: Analysis through breath testing. J Crit Care. 2015 Jun;30(3):655.e7-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.12.019. Epub 2015 Jan 7. PMID: 25746849. |

Wrong comparison (different prokinetic regimens) |

|

MacLaren R, Kiser TH, Fish DN, Wischmeyer PE. Erythromycin vs metoclopramide for facilitating gastric emptying and tolerance to intragastric nutrition in critically ill patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2008 Jul-Aug;32(4):412-9. doi: 10.1177/0148607108319803. PMID: 18596312. |

Wrong comparison (Erythromycin versus metoclopramide) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 07-03-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 05-03-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de

samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten die gevoed worden op de intensive care.

Werkgroep

dr. R. (Robert) Tepaske, intensivist, (voorzitter) NVIC

Prof. dr. A.R.H. (Arthur) van Zanten, intensivist, NVIC

dr. M.C.G. (Marcel) van de Poll, intensivist, NVIC

drs. B. (Ben) van der Hoven, internist, NIV

drs. E.J. (Lisa) Mijzen, anesthesioloog-intensivist, NVA

dr. F.J. (Jeannette) Schoonderbeek, chirurg-intensivist, NVvH

L. (Lea) van Duijvenbode - den Dekker, MSc, intensive care verpleegkundige, V&VN Intensive Care

M. (Manon) Mensink, diëtist, NVD

Ir. S. (Suzanne) ten Dam, diëtist, NVD

I. (Idske) Dotinga, ervaringsdeskundige, FCIC/IC Connect

Klankbordgroep

Mevr. E.R. (Elske) van Liere, logopedist, NVLF

Met ondersteuning van

Dr. F. Willeboordse, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

I. van Dijk, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen