Treatment of acute hypersensitivity reaction

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de optimale behandeling voor acute overgevoeligheidsreacties op contrastmiddelen?

Aanbeveling

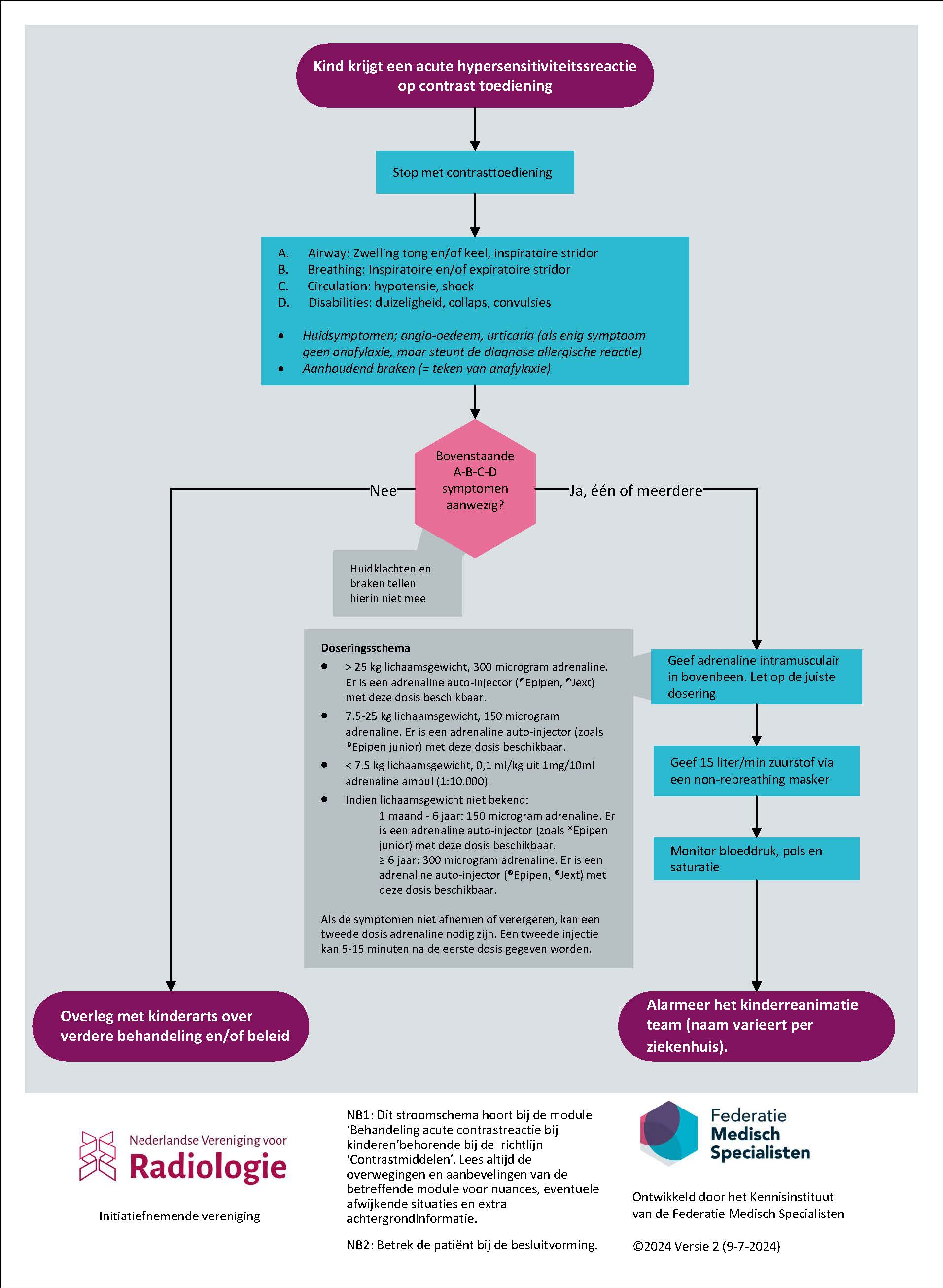

Acute allergische reacties verschillen in ernst; de aanbevelingen zijn per ernst van de situatie geformuleerd.

Bij anafylactische reactie:

- Geef adrenaline intramusculair. Let op de juiste dosering:

- >25 kg lichaamsgewicht 300 microgram adrenaline (adrenaline auto-injectors beschikbaar, zoals de Epipen® or Jext®),

- 7.5-25 kg lichaamsgewicht 150 microgram adrenaline (adrenaline auto-injectors beschikbaar, zoals de Epipen Junior® or Jext®),

- < 7.5 kg lichaamsgewicht , 10 mcg/kg, overeenkomend met 0.1 ml/kg uit 1mg/10ml adrenaline ampul (1:10.000).

- Indien het gewicht niet bekend is: ≥ 6 jaar 300 microgram (Epipen® or Jext®), < 6 jaar 150 microgram (Epipen Junior® or Jext®).

- Geef 15 liter/minuut zuurstof via een non-rebreathing masker.

- Alarmeer het (kinder)reanimatie team (naam varieert per ziekenhuis).

- Als de symptomen niet afnemen of verergeren, kan een tweede dosis adrenaline nodig zijn. Een tweede injectie kan 5-15 minuten na de eerste dosis gegeven worden.

Bij niet-anafylactische acute overgevoeligheidsreacties:

- Overleg met een kinderarts over verdere behandeling en/of beleid.

Overwegingen

Advantages and disadvantages of the intervention and quality of evidence

The work group conducted a systematic review of the optimal treatment for acute hypersensitivity reactions to contrast agents. No articles were found that met the inclusion criteria. Therefore, no conclusions could be drawn about the effects of treatment for acute hypersensitivity reactions on the outcome measures duration of acute allergic reaction, severity of symptoms, morbidity, mortality, costs, ICU admission, length of stay. Therefore, a knowledge gap exists on this topic.

As there are no comparative studies investigating the optimal treatment for acute hypersensitivity reactions to contrast agents in children, the recommendations in this national guideline are based mainly on expert opinion in combination with two other sources of relevant literature. The first is the Dutch National Advanced Paediatric Life Support book (Turner, 2022). This is considered the standard with regard to dealing with life threatening pediatric conditions, including anaphylaxis.

We also used the adult guideline for the treatment of acute hypersensitivity reactions to contrast media (NVvR, 2020). We adhere to the adult guidelines as much as possible, taking into account differences between adults and children in physiology and treatment options. First, we describe key differences to consider, followed by the treatment options.

Differences between adults and children

- The airways in children differ from those in adults in diameter and shape, making children especially vulnerable to airway narrowing due to anaphylaxis.

- Unlike adults, children in general have better developed mechanisms of compensation. Unfortunately, the degree of sickness can easily be underestimated.

- In children medication is based on body weight in kilograms. If this is unknown, age is used as a surrogate to estimate body weight.

- Like in adults, APLS guidelines with an ABC-type approach is used (NVvR, 2020).

Acute hypersensitivity reactions

Patients who develop an acute hypersensitivity reaction to contrast agents may have a variety of symptoms. Varying from mild symptoms, for example a rash, to severe potentially life-threatening reactions with symptoms like (airway) edema, inspiratory and expiratory stridor, hypotension, collapse and persistent vomiting. These severe reactions are also called anaphylaxis. Since the frequency of severe hypersensitivity reactions to contrast agents is quite rare, the guideline development group focuses on three simple but effective ways to stabilize the patient while waiting for a pediatric resuscitation team. Further treatment is best done by a pediatrician or pediatric anesthesiologist. The three measures to treat anaphylaxis are described in more detail below. For non-anaphylactic acute hypersensitivity reactions to contrast agents, the guideline development group recommends consulting a pediatrician.

Three measures to treat anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis or severe hypersensitivity reactions are potentially life-threatening and it is important to start treatment as soon as possible. Quick administration of intramuscular adrenaline will swiftly alleviate symptoms. The second most important treatment will be administration of 15 liter per minute of oxygen, via a non-rebreathing mask. It is important to have smaller masks suitable for children on hand in the CT room. However, since the effect of the adrenaline may be temporary, specialized pediatric care is required. So third, a (pediatric) resuscitation team needs to be called to assist immediately (the exact name and composition of this team differs between hospitals). The goal of treatment for anaphylaxis is to stabilize the patient, while waiting for a pediatric resuscitation team. Further recommendations regarding the treatment of children with hypersensitivity reactions are beyond the scope of this guideline. Pediatricians will follow APLS guidelines for further treatment of hypersensitivity reactions.

Unlike the treatment of anaphylaxis in adults, clemastine is no longer recommended for treatment of anaphylaxis in children. It’s known to cause hypotension and drowsiness; this last side effect can further compromise airway patency.

Adrenaline administration

In the setting of anaphylaxis, adrenaline should be administered into the muscle (intramuscular injection). The recommended dose is:

- >25 kg body weight: 300 microgram adrenaline (adrenalin auto-injectors available, such as Epipen® or Jext®),

- 7.5-25 kg body weight: 150 microgram adrenaline (adrenalin auto-injectors available, such as Epipen Junior® or Jext®),

- < 7.5 kg body weight: 10 mcg/kg, (equals 0.1 ml/kg from 1mg/10ml adrenaline vial ( 1:10,000).

- When weight is unknown: ≥ 6 years 300 microgram (adrenalin auto-injectors available, such as Epipen® or Jext®), < 6 years 150 microgram (adrenalin auto-injectors available, such as Epipen Junior® or Jext®).

- When symptoms do not decrease or progress a second dose of adrenalin can be necessary. A second injection can be given 5-15 minutes after the first dose.

Adrenaline is available in vials, from which the solution must be aspirated into a syringe before it can be administered to the child. Another option is to use an adrenalin auto-injector, in which an adrenaline solution is already in a syringe. These devices can be spring loaded, such as the Epipen®. An adrenaline auto-injector is used to administer adrenaline intramuscularly in an acute setting. Since most healthcare providers in radiology do not use needles and syringes to administer medication on a daily basis, and since time is of the utmost essence, the guideline development group strongly advises use of an adrenalin auto-injector despite a higher cost (see cost paragraph below for more details).

Patient (and their caretakers) values and preferences

Acute hypersensitivity reactions to contrast media are a cause of concern for patients and their caregivers, especially if they have experienced acute hypersensitivity reactions in the past. It is important to distinguish severe reactions such as anaphylaxis from mild reactions such as rash, since treatment and response should be in proportion. In case of severe reactions, namely anaphylaxis, the focus is on swift intervention to reduce the immediate concern (airway restriction), meanwhile ensuring the correct expertise is sent by contacting a pediatric resuscitation team for any further decisions on treatment. In case of mild acute hypersensitivity reactions, there is more time to formulate a treatment strategy and, if necessary, consult the appropriate experts.

Costs

It is important to act quickly and effectively to prevent serious complications from acute hypersensitivity reactions, and reduce associated additional healthcare costs both in the short and long term. Most of the recommendations in this guideline lead no or little additional costs. Oxygen is usually already available in CT suites and non-rebreathing masks cost around 5 euros each. Only for adrenaline administration in children weighing >10 kg does the guideline development group strongly advice a higher priced alternative, based on the ease of use and thus more time efficient administration. For example, the use of adrenalin auto-injectors such as the Epipen® (cost 38-42 euros) instead of adrenaline injection using vials (3 euros for 1mg/1ml solution) (Zorginstituut Nederland, n.d.). For children weighing less than 10 kilograms, the only option is to administer the (=weight adjusted) amount of adrenaline with a syringe.

Acceptability, feasibility and implementation

The guideline development group does not anticipate any acceptance or feasibility issues. The triad adrenaline / high flow oxygen / calling for help is a simple but effective strategy in cases of anaphylactic acute hypersensitivity reactions. High oxygen flow is already standard in the treatment of anaphylactic acute hypersensitivity reactions in adults. Ensuring smaller non-rebreathing masks suitable for children are present should not provide problems as these are already used and readily available in hospital. Similarly, the guideline development group anticipates it will be feasible to ensure the way to contact the paediatric resuscitation team is clearly signposted near the CT scanner and contact details for a paediatrician are available. Regarding adrenaline, many radiology departments are already familiar with the use of an adrenalin auto-injectors. Therefore, the introduction of an Adrenaline auto-injector (for children who weigh more than 7.5 kilograms) is expected to be acceptable and feasible. If contrast media is also given to children who weigh less than 7.5 kilograms, a 0,1mg/10 ml vial of adrenaline (with needles and syringes) also needs to be present.

In terms of implementation, given the rarity of these types of reactions it is important to provide adequate training of personnel on how to handle acute contrast reactions in children. Thus, ensuring the correct level of expertise is maintained to act when necessary.

Rationale of the recommendation: weighing arguments for and against the interventions

Unfortunately, there were no comparative studies investigating the optimal treatment for acute hypersensitivity reactions to contrast agents in children. Therefore, the recommendations in this national guideline are based mainly on expert opinion in combination with a current standard book on Advanced Paediatric Life Support (Turner, 2022) and the existing adult guideline for the treatment of acute hypersensitivity reactions to contrast media (NVvR, 2020).

Since the airways in children differ from those in adults in diameter and shape, this makes children especially vulnerable to airway narrowing due to anaphylaxis. To treat airway narrowing due to an anaphylactic acute hypersensitivity reaction to contrast media, adrenaline should be administered intramuscularly. In addition to this, high flow oxygen should be given by means of a non-rebreathing mask. Since anaphylaxis is a paediatric emergency, advanced paediatric life support expertise is required immediately, to further treat the child and prevent rapid deterioration of the condition of the child.

Overall, there is consensus in our guideline development group that these three basic measures (adrenaline, oxygen, call for help) are critical in the primary treatment of life-threatening anaphylaxis. In case of mild acute hypersensitivity reactions, there is more time to formulate a treatment strategy and, if necessary, consult the appropriate experts.

The guideline development group does not anticipate any acceptance, feasibility or implementation issues.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Anaphylaxis due to intravenous contrast media is rare in children. Currently, radiologists use a combination of adult guidelines and experience to treat acute hypersensitivity reactions to contrast media in children. However, children are a heterogeneous population in terms of age and background. Children have a different anatomy of the upper airways, making them especially vulnerable to airway constriction due to anaphylaxis. Also, since children come in different shapes and sizes, tailormade approach based on body weight and anatomical differences in comparison to adults, is required. Therefore, the current guideline describes the optimal treatment for acute hypersensitivity reactions to contrast media in children.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of different kinds of treatment to reduce duration of acute allergic reaction in children (<18 years of age) undergoing radiological examinations with contrast agents. |

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of different kinds of treatment to reduce severity of complaints of acute allergic reaction in children (<18 years of age) undergoing radiological examinations with contrast agents. |

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of different kinds of treatment to reduce morbidity due to acute allergic reaction in children (<18 years of age) undergoing radiological examinations with contrast agents. |

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of different kinds of treatment to reduce mortality due to acute allergic reaction in children (<18 years of age) undergoing radiological examinations with contrast agents. |

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of different kinds of treatment to reduce costs due to acute allergic reaction in children (<18 years of age) undergoing radiological examinations with contrast agents. |

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of different kinds of treatment to reduce hospitalization in an IC-unit due to acute allergic reaction in children (<18 years of age) undergoing radiological examinations with contrast agents. |

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of different kinds of treatment to reduce length of stay in hospital due to acute allergic reaction, in children (<18 years of age) undergoing radiological examinations with contrast agents. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

No studies were included in the analysis of the literature.

Results

No studies were included in the analysis of the literature.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence could not be determined as no studies were included in the analysis of the literature.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the effects of different measures to reduce symptoms of hypersensitivity reactions in children (<18 years of age) undergoing radiological examinations with contrast media?

| P(atients): | Children (<18 years) with acute hypersensitivity reaction after administration of contrast media; |

| I(ntervention): | Treatment, antihistamines, corticosteroids, epinephrine, adrenalin, dopamine, norepinephrine, noradrenalin, histamine H1 antagonists, histamine H2 antagonists, H1 antihistamines, H2 antihistamines, adrenergic beta-2 receptor agonists, glucocorticoids, management/treatment of hypersensitivity reactions/allergic reactions after contrast media, antihistamines, volume resuscitation, bronchodilators; |

| C(ontrol): | Conservative treatment or comparison of interventions mentioned above; |

| O(utcome): |

Curation of acute allergic reactions, severity of complaints, morbidity, mortality, costs, hospitalization in an IC-unit, length of stay. |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered morbidity, mortality, and hospitalization in an IC-unit as critical outcome measures for decision making; and duration of acute reaction, length of stay and costs, as outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the guideline development group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The guideline development group defined the following as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference:

- Duration of acute allergic reaction: 0.5 SD (continuous);

- Severity of complaints: 0.5 SD (continuous);

- Morbidity: relative risk <0.91 or >1.10;

- Mortality: relative risk <0.95 or >1.05;

- Hospitalization in an IC-unit: relative risk <0.80 or >1.25;

- Length of stay in hospital: 0.5 SD (continuous);

- Costs: 0.5 SD (continuous);

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 1990 until 14-03-2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 147 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review, randomized controlled trial or observational research comparing treatment for acute hypersensitivity reactions to conservative treatment or another kind of treatment.

- Including children (<18 years) with an acute hypersensitivity reaction after administration of contrast media.

- Reporting at least one of the following outcome measures: duration of acute allergic reaction, severity of complaints, morbidity, mortality, costs, hospitalization in an IC-unit, length of stay.

26 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, all studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and no studies were included.

Results

No studies were included in the analysis of the literature.

Referenties

- NVvR, 2020. Richtlijn Veilig gebruik van contrastmiddelen - Module Behandeling van acute hypersensitiviteitsreacties na CM. Beoordeeld: 24-06-2020.

- Turner, N. M., Kieboom J., and van Vught A. J. "Advanced Paediatric Life Support, de Nederlandse editie (6e dr.)." (2022).

- Zorginstituut Nederland. (n.d.). Farmacotherapeutisch kompas: Adrenaline. Geraadpleegd op 19 september 2023.

Evidence tabellen

Not applicable for this module.

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Ahn, Y. H. and Kang, D. Y. and Park, S. B. and Kim, H. H. and Kim, H. J. and Park, G. Y. and Yoon, S. H. and Choi, Y. H. and Lee, S. Y. and Kang, H. R. Allergic-like Hypersensitivity Reactions to Gadolinium-based Contrast Agents: An 8-year Cohort Study of 154539 Patients. Radiology. 2022; 303 (2) :329-336 |

Wrong population, Wrong intervention |

|

Anibarro Bausela, B. and Berto Salort, J. M. and Garcia Ara, M. C. and Diaz Pena, J. M. and Ojeda Casas, J. A. Allergic drug reactions during childhood. Anales Espanoles de Pediatria. 1992; 36 (6) :447-450 |

Wrong language, Wrong design |

|

Callahan, M. J. and Poznauskis, L. and Zurakowski, D. and Taylor, G. A. Nonionic Lodinated intravenous contrast material-related reactions: Incidence in large Urban children's hospital-retrospective analysis of data in 12 494 patients. Radiology. 2009; 250 (3) :674-681 |

Wrong design |

|

Connor, S. E. J. and Banerjee, A. K. and Dawkins, D. M. Intravenous contrast media: Are they being administered safely in radiology departments?. British Journal of Radiology. 1997; 70 :1104-1108 |

Wrong design |

|

Davenport, M. S. and Cohan, R. H. and Caoili, E. M. and Ellis, J. H. Repeat contrast medium reactions in premedicated patients: Frequency and severity. Radiology. 2009; 253 (2) :372-379 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Dillman, J. R. and Ellis, J. H. and Cohan, R. H. and Strouse, P. J. and Jan, S. C. Frequency and severity of acute allergic-like reactions to gadolinium-containing i.v. contrast media in children and adults. AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2007; 189 (6) :1533-8 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Dormans, J. P. and Templeton, J. and Schreiner, M. S. and Delfico, A. J. Intraoperative latex anaphylaxis in children: Classification and prophylaxis of patients at risk. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 1997; 17 (5) :622-625 |

Wrong design |

|

Farmakis, S. G. and Hardy, A. K. and Mahmoud, S. Y. and Wilson-Flewelling, S. A. and Tao, T. Y. Safety of gadoterate meglumine in children younger than 2 years of age. Pediatric Radiology. 2020; 50 (6) :855-862 |

Wrong design |

|

Forbes-Amrhein, M. M. and Dillman, J. R. and Trout, A. T. and Koch, B. L. and Dickerson, J. M. and Giordano, R. M. and Towbin, A. J. Frequency and Severity of Acute Allergic-Like Reactions to Intravenously Administered Gadolinium-Based Contrast Media in Children. Investigative Radiology. 2018; 53 (5) :313-318 |

Wrong design |

|

Gaca, A. M. and Frush, D. P. and Hohenhaus, S. M. and Luo, X. and Ancarana, A. and Pickles, A. and Frush, K. S. Enhancing pediatric safety: Using simulation to assess radiology resident preparedness for anaphylaxis from intravenous contrast media. Radiology. 2007; 245 (1) :236-244 |

Wrong design |

|

Gottumukkala, R. V. and Glover, M. and Yun, B. J. and Sonis, J. D. and Kalra, M. K. and Otrakji, A. and Raja, A. S. and Prabhakar, A. M. Allergic-like contrast reactions in the ED: Incidence, management, and impact on patient disposition. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2018; 36 (5) :825-828 |

Wrong population, Wrong design |

|

Hojreh, A. and Peyrl, A. and Bundalo, A. and Szepfalusi, Z. Subsequent MRI of pediatric patients after an adverse reaction to Gadolinium-based contrast agents. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2020; 15 (4) :e0230781 |

Wrong design |

|

Hsieh C, Wu SC, Kosik RO, Huang YC, Chan WP. Pharmacological Prevention of Hypersensitivity Reactions Caused by Iodinated Contrast Media: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022 Jul 9;12(7):1673. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12071673. PMID: 35885578; PMCID: PMC9320945. |

Wrong population, Wrong intervention |

|

Hunt, C. H. and Hartman, R. P. and Hesley, G. K. Frequency and severity of adverse effects of iodinated and gadolinium contrast materials: Retrospective review of 456,930 doses. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2009; 193 (4) :1124-1127 |

Wrong population |

|

Katsogiannou, M. and Carsin, A. and Mazenq, J. and Dubus, J. C. and Gervoise-Boyer, M. J. Drug hypersensitivity in children: a retrospective analysis of 101 pharmacovigilance reports. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2021; 180 (2) :495-503 |

Wrong design |

|

Kim, S. H. and Jo, E. J. and Kim, M. Y. and Lee, S. E. and Kim, M. H. and Yang, M. S. and Song, W. J. and Choi, S. I. and Kim, J. H. and Chang, Y. S. Clinical value of radiocontrast media skin tests as a prescreening and diagnostic tool in hypersensitivity reactions. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. 2013; 110 (4) :258-262 |

Wrong design |

|

Laroche, D. and Aimone-Gastin, I. and Dubois, F. and Huet, H. and Gérard, P. and Vergnaud, M. C. and Mouton-Faivre, C. and Guéant, J. L. and Laxenaire, M. C. and Bricard, H. Mechanisms of severe, immediate reactions to iodinated contrast material. Radiology. 1998; 209 (1) :183-190 |

Wrong design |

|

Li, A. and Wong, C. S. and Wong, M. K. and Lee, C. M. and Au Yeung, M. C. Acute adverse reactions to magnetic resonance contrast media - Gadolinium chelates. British Journal of Radiology. 2006; 79 (941) :368-371 |

Wrong population, Wrong design |

|

Lindsay, R. and Paterson, A. and Edgar, D. Preparing for severe contrast media reactions in children - Results of a national survey, a literature review and a suggested protocol. Clinical Radiology. 2011; 66 (4) :340-348 |

Wrong design |

|

McDonald, J. S. and Larson, N. B. and Kolbe, A. B. and Hunt, C. H. and Schmitz, J. J. and Kallmes, D. F. and McDonald, R. J. Acute reactions to gadolinium-based contrast agents in a pediatric cohort: A retrospective study of 16,237 injections. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2021; 216 (5) :1363-1369 |

Wrong design |

|

McDonald, J. S. and Larson, N. B. and Kolbe, A. B. and Hunt, C. H. and Schmitz, J. J. and Maddox, D. E. and Hartman, R. P. and Kallmes, D. F. and McDonald, R. J. Prevention of allergic-like reactions at repeat CT: Steroid pretreatment versus contrast material substitution. Radiology. 2021; 301 (1) :133-140 |

Wrong population, Wrong intervention |

|

Mervak, B. M. and Davenport, M. S. and Ellis, J. H. and Cohan, R. H. Rates of breakthrough reactions in inpatients at high risk receiving premedication before contrast-enhanced CT. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2015; 205 (1) :77-84 |

Wrong design |

|

Power, S. and Talbot, N. and Kucharczyk, W. and Mandell, D. M. Allergic-like reactions to the MR imaging contrast agent gadobutrol: A prospective study of 32 991 consecutive injections. Radiology. 2016; 281 (1) :72-77 |

Wrong design |

|

Pumphrey, R. S. H. Lessons for management of anaphylaxis from a study of fatal reactions. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 2000; 30 (8) :1144-1150 |

Wrong population, Wrong design |

|

Renaudin, J. M. and Beaudouin, E. and Ponvert, C. and Demoly, P. and Moneret-Vautrin, D. A. Severe drug-induced anaphylaxis: Analysis of 333 cases recorded by the Allergy Vigilance Network from 2002 to 2010. Allergy: European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2013; 68 (7) :929-937 |

Wrong population, Wrong design |

|

Zhang B, Dong Y, Liang L, Lian Z, Liu J, Luo X, Chen W, Li X, Liang C, Zhang S. The Incidence, Classification, and Management of Acute Adverse Reactions to the Low-Osmolar Iodinated Contrast Media Isovue and Ultravist in Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography Scanning. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Mar;95(12):e3170. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003170. PMID: 27015204; PMCID: PMC4998399. |

Wrong population, Wrong design |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 04-09-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-12-2024

Validity

The Radiological Society of the Netherlands (NVvR) will determine if this guideline (per module) is still valid and applicable around 2029. If necessary, the scientific societies will form a new guideline group to revise the guideline. The validity of a guideline can be shorter than 5 years, if new scientific or healthcare structure developments arise, asking for a revision of the guideline. The Radiological Society of the Netherlands is the owner of this guideline and therefore primarily responsible for the actuality of the guideline. Other scientific societies that have participated in the guideline development share the responsibility to inform the primarily responsible scientific society about relevant developments in their field.

Algemene gegevens

General Information

The Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten assisted the guideline development group. The guideline was financed by Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS) which is a quality fund for medical specialists in The Netherlands.

Samenstelling werkgroep

A multidisciplinary guideline development group (GDG) was formed for the development of the guideline in 2022. The GDG consisted of representatives from all relevant medical specialization fields which were using intravascular contrast administration in their field.

All GDG members have been officially delegated for participation in the GDG by their scientific societies. The GDG has developed a guideline in the period from June 2022 until July 2024. The GDG is responsible for the complete text of this guideline.

Guideline development group

- de Graaf N. (Nanko), chair guideline development group, radiologist, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam

- Den Dekker M.A.M. (Martijn), radiologist, Ziekenhuis ZorgSaam

- Emons J.A.M. (Joyce), paediatric allergist, Sophia Children’s Hospital, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam

- Geenen R.W.F. (Remy), radiologist, Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep, Alkmaar

- Jöbsis, J.J. (Jasper), paediatrician and nephrologist, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam

- Liebrand C.A. (Chantal), anaesthesiologist, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam

- Sloots C.E.J. (Pim), surgeon, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam

- Zwaveling-Soonawala N. (Nitash), paediatrician -endocrinologist, Amsterdam University Medical Center, Amsterdam.

Advisory group

- Doganer E.C. (Esen), Kind & Ziekenhuis, Patient representative

- Riedijk M.A. (Maaike), paediatrician and intensive care physician, Emma Hospital, Amsterdam University Medical Centre

- Van der Molen A.J. (Aart), radiologist, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden

Methodological support

• Houtepen L.C. (Lotte), advisor, Knowledge Institute of the Federation Medical Specialists

• Mostovaya I.M. (Irina), senior advisor, Knowledge Institute of the Federation Medical Specialists

Belangenverklaringen

Conflicts of interest

The GDG members have provided written statements about (financially supported) relations with commercial companies, organisations or institutions that were related to the subject matter of the guideline. Furthermore, inquiries have been made regarding personal financial interests, interests due to personal relationships, interests related to reputation management, interest is related to externally financed research and interests related to knowledge valorisation. The statements on conflict of interest can be requested from the administrative office of Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (secretariaat@kennisinstituut.nl) and were summarised below.

|

Last name |

Function |

Other positions |

Personal financial interests |

Personal relations |

Reputation management |

Externally financed research |

Knowledge valorisation |

Other interests |

Signed |

Actions |

|

De Graaf |

Radiologist, Erasmus Medical Centre Rotterdam, |

Board member of the Technology section, Netherlands. Far. for Radiology (unpaid) Board member Ned. Comm. Radiation dosimetry (NCS) (unpaid) |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

July 14th, 2022

|

No restrictions. |

|

Geenen RWF |

Radiologist, Noordwest ziekenhuisgroep/medisch specialisten Noordwest |

Member of contrast media safety committee, European Society of Urogenital Radiology (no payment) |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

September 2nd, 2022 |

No restrictions |

|

Emons |

Pediatrician-allergologist, Erasmus MC-Sophia, paid |

Editorial board NTvAAKI, unpaid NVvAKI communications committee, unpaid |

None |

None |

None |

Epitope study, cutaneous immunotherapy for peanut, DBV BAT cow's milk study, NWO Itulizax study, tree pollen immunotherapy, ALK |

None |

None |

July 7th, 2022

|

No restrictions, research has no link with hypersensitivity reactions after administration of contrast agents in children. |

|

Jöbsis |

Pediatrician, pediatric nephrologist |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

July 2nd, 2022 |

No restrictions |

|

Sloots |

Pediatric surgeon Erasmus MC Sophia Children's Hospital |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

August, 15th, 2022

|

No restrictions |

|

Liebrand |

Anaesthesiologist Sophia Children's Hospital/Erasmus MC Pediatrician St. Antonius Hospital, Kleve |

Notarzt Kreis Kleve |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

December, 20th, 2022

|

No restrictions |

|

Zwaveling-Soonawala |

Pediatrician-endocrinologist, Emma Children's Hospital, Amsterdam UMC |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

June, 13th, 2023

|

No restrictions |

|

Advisory group |

||||||||||

|

Molen AJ, van der |

Radiologist LUMC |

Member of contrast media safety committee, European Society of Urogenital Radiology (no payment). |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Received speaker fees from Guerbet, 2019-2022 |

June, 5th, 2023

|

No restrictions (given the role as a sounding board group member, no active contribution to texts and the mandate for decisions rests with the guideline development group, no further restrictions have been formulated for the ancillary activities at the gadopiclenol expert group) |

|

Riedijk |

Pediatrician Amsterdam UMC - Emma Children's Hospital |

Board member SICK: unpaid. PICE board member: unpaid. |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

December, 6th, 2022

|

No restrictions |

|

Doganer |

Junior project manager/policy officer at the Child and Hospital Foundation |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

July, 25th, 2023

|

No restrictions |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Input of patient’s perspective

The guideline does not address a specific child patient group, but a diverse set of diagnoses. Therefore, it was decided to invite a broad spectrum of patient organisations for the stakeholder consultation, and invite the patient organisation Kind & Ziekenhuis (translated as Child and Hospital Foundation) in the Advisory group. The stakeholder consultation was performed at the beginning of the process for feedbacking on the framework of subjects and clinical questions addressed in the guideline, and during the commentary phase to provide feedback on the concept guideline. The list of organisations which were invited for the stakeholder consultation can be requested from the Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (secretariaat@kennisinstituut.nl). In addition, patient information on safe use of contrast media in children was developed for Thuisarts.nl, a platform to inform patients about health and disease.

Implementatie

Implementation

During different phases of the guideline development, implementation and practical enforceability of the guideline were considered. The factors that could facilitate or hinder the introduction of the guideline in clinical practice have been explicitly considered. The implementation plan can be found in the ‘Appendices to modules’. Furthermore, quality indicators were developed to enhance the implementation of the guideline. The indicators can also be found in the ‘Appendices to modules’.

Werkwijze

Methodology

AGREE

This guideline has been developed conforming to the requirements of the report of Guidelines for Medical Specialists 2.0 by the advisory committee of the Quality Counsel (www.kwaliteitskoepel.nl). This report is based on the AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II) (www.agreetrust.org), a broadly accepted instrument in the international community and based on the national quality standards for guidelines: “Guidelines for guidelines” (www.zorginstituutnederland.nl).

Identification of subject matter

During the initial phase of the guideline development, the GDG identified the relevant subject matter for the guideline. The framework is consisted of both new matters, which were not yet addressed in Part 1, 2 and 3 of the guideline, and an update of matters that were subject to modification (for example in case of new published literature). Furthermore, a stakeholder consultation was performed, whre input on the framework was requested.

Clinical questions and outcomes

The outcome of the stakeholder consultation was discussed with the GDG, after which definitive clinical questions were formulated. Subsequently, the GDG formulated relevant outcome measures (both beneficial and harmful effects). The GDG rated the outcome measures as critical, important and of limited importance (GRADE method). Furthermore, where applicable, the GDG defined relevant clinical differences.

Search and select

For clinical questions, specific search strategies were formulated, and scientific articles published in several electronic databases were searched. First, the studies that potentially had the highest quality of research were reviewed. The GDG selected literature in pairs (independently of each other) based on the title and abstract. A second selection was performed by the methodological advisor based on full text. The databases used, selection criteria and number of included articles can be found in the modules, the search strategy can be found in the appendix.

Quality assessment of individual studies

Individual studies were systematically assessed, based on methodological quality criteria that were determined prior to the search. For systematic reviews, a combination of the AMSTAR checklist and PRISMA checklist was used. For RCTs the Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University were used, and for cohort studies/observational studies the risk of bias tool by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University was used. The risk of bias tables can be found in the separate document “Appendices to modules”.

Summary of literature

The relevant research findings of all selected articles were shown in evidence tables. The evidence tables can be found in the separate document “Appendices to modules”. The most important findings in literature were described in literature summaries. When there were enough similarities between studies, the study data were pooled.

Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations

The strength of the conclusions of the included studies was determined using the GRADE-method. GRADE stands for Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (see http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org) (Atkins, 2004). GRADE defines four levels for the quality of scientific evidence: high, moderate, low, or very low. These levels provide information about the certainty level of the literature conclusions (http://www.guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook).

The evidence was summarized in the literature analysis, followed by one or more conclusions, drawn from the body of evidence. The level of evidence for the conclusions can be found above the conclusions. Aspects such as expertise of GDG members, local expertise, patient preferences, costs, availability of facilities and organisation of healthcare are important to consider when formulating a recommendation. These aspects are discussed in the paragraph “Justifications”. The recommendations provide an answer to the clinical question or help to increase awareness and were based on the available scientific evidence and the most relevant “Justifications”.

Appendices

Internal (meant for use by scientific society or its members) quality indicators were developed during the conception of the guideline and can be found in the separate document “Appendices to modules”. In most cases, indicators were not applicable. For most questions, additional scientific research on the subject is warranted. Therefore, the GDG formulated knowledge gaps to aid in future research, which can be found in the separate document “Appendices to modules”.

Commentary and authorisation phase

The concept guideline was subjected to commentaries by the involved scientific societies. The list of parties that participated in the commentary phase can be requested from the Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (secretariaat@kennisinstituut.nl).

The commentaries were collected and discussed with the GDG. The feedback was used to improve the guideline; afterwards the guideline was made definitive by the GDG. The final version of the guideline was offered to the involved scientific societies for authorization and was authorized.

Literature

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010; 182(18): E839-E842.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0. Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit, 2012. Available at: [URL].

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available at: [URL].

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008;336(7653):1106-1110. Erratum published in: BMJ 2008;336(7654).

Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen: stappenplan. Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten, 2020.

Zoekverantwoording

|

Richtlijn: NVvR Veilig gebruik van Contrastmiddelen deel 4 – kinderen |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag: Wat is de optimale behandeling voor acute overgevoeligheidsreacties op contrastmiddelen? |

|

|

Database(s): Medline (OVID), Embase |

Datum: 14-03-2023 |

|

Periode: >1990 |

Talen: Geen beperking |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Linda Niesink |

|

|

BMI zoekblokken: voor verschillende opdrachten wordt (deels) gebruik gemaakt van de zoekblokken van BMI-Online https://blocks.bmi-online.nl/ Bij gebruikmaking van een volledig zoekblok zal naar de betreffende link op de website worden verwezen. |

|

|

Te gebruiken voor richtlijnen tekst: In de databases Embase (via embase.com) en Medline (via OVID) is op 14-03-2023 met relevante zoektermen gezocht vanaf 1990 naar systematische reviews, RCT’s en observationele studiedesigns over behandelingen van overgevoeligheidsreacties bij kinderen die een contrastmiddel hebben toegediend gekregen. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 147 unieke treffers op. |

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

EMBASE |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SRs |

13 |

1 |

13 |

|

RCTs |

47 |

5 |

49 |

|

Observationele studies |

80 |

18 |

85 |

|

Totaal |

140 |

24 |

147 |

Zoekstrategie

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Embase

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medline (OVID)

|

1 exp *Contrast Media/ or Barium/ or exp Microbubbles/ or exp Gadolinium/ or (((contrast or radiocontrast) adj2 (medi* or agent* or material* or dose or doses or dosage or induced or enhanced or exposure or administration or iodinated or iodine*)) or 'radiopaque medi*' or barium or gadolinium or microbubble* or 'gadolinium-based' or gbca* or primovist or eovist or omniscan or magnevist or optimark or prohance or multihance or dotarem or gadovist or gadavist or gadodiamide or gadopentetate or gadoversetamide or gadoteridol or gadobenate or gadoterate or gadobutrol or 'gadoxetic acid' or 'gadoxetate disodium' or 'gd dtpa' or 'gd hp do3a' or 'gd dtpa bma' or 'gd dota' or 'gd dtpa bmea' or 'gd bopta' or 'gd bt do3a' or 'gd eob dtpa' or meglumine or dimeglumine or sonovue or optison or lumason or definity or perflutren or hexafluoride or micropaque or 'e-z cat' or polibar or barite or baritop or visipaque or hexabrix or iomeron or iopamiro or omnipaque or optiray or ultravist or xenetix or iodixanol or ioxaglate or iomeprol or iopamidol or iosimenol or iohexol or ioversol or iopromide or iobitridol).ti,ab,kf. (212107) 2 (child* or schoolchild* or infan* or adolescen* or pediatri* or paediatr* or neonat* or boy or boys or boyhood or girl or girls or girlhood or youth or youths or baby or babies or toddler* or childhood or teen or teens or teenager* or newborn* or postneonat* or postnat* or puberty or preschool* or suckling* or picu or nicu or juvenile?).tw. (2866736) 3 exp Hypersensitivity/ or (hypersensitiv* or anaphyla* or allerg* or rash or 'adverse reaction*' or 'drug reaction*' urticaria* or erythem* or exanthem* or edema or angioedema or bronchospasm* or hypotension or hypertension or 'cardiac arrest' or 'respiratory arrest' or 'stevens johnson syndrome' or sjs or 'toxic epidermal necrolys*' or 'dress syndrome' or 'iodide mump*').ti,ab,kf. or ((late or delayed or nonimmediate or immediate or acute or severe) adj2 reaction*).ti,ab,kf. (1346826) 4 exp Drug Hypersensitivity/ or exp Histamine H1 Antagonists/ or exp Receptors, Adrenergic, beta-2/ or exp Adrenal Cortex Hormones/ or exp Epinephrine/ or exp Dopamine/ or exp Norepinephrine/ or exp Glucocorticoids/ or exp Bronchodilator Agents/ or 'breakthrough reaction*'.ti,ab,kf. or antihistamin*.ti,ab,kf. or corticosteriod*.ti,ab,kf. or epinephrin*.ti,ab,kf. or adrenalin*.ti,ab,kf. or dopamin*.ti,ab,kf. or norepinephrin*.ti,ab,kf. or noradrenalin*.ti,ab,kf. or (histamin* adj3 antagonist*).ti,ab,kf. or (adrenergic adj3 agonist*).ti,ab,kf. or glucocorticoid*.ti,ab,kf. or ((volume or fluid) adj3 resuscitat*).ti,ab,kf. or bronchodilat*.ti,ab,kf. (1076030) 5 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 (86) 6 limit 5 to yr="1990 -Current" (80) 7 6 not (comment/ or editorial/ or letter/ or ((exp animals/ or exp models, animal/) not humans/)) (68) 8 meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (metaanaly* or meta-analy* or metanaly*).ti,ab,kf. or systematic review/ or cochrane.jw. or (prisma or prospero).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or scoping or umbrella or "structured literature") adj3 (review* or overview*)).ti,ab,kf. or (systemic* adj1 review*).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or literature or database* or data-base*) adj10 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((structured or comprehensive* or systemic*) adj3 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((literature adj3 review*) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ti,ab,kf. or (("data extraction" or "data source*") and "study selection").ti,ab,kf. or ("search strategy" and "selection criteria").ti,ab,kf. or ("data source*" and "data synthesis").ti,ab,kf. or (medline or pubmed or embase or cochrane).ab. or ((critical or rapid) adj2 (review* or overview* or synthes*)).ti. or (((critical* or rapid*) adj3 (review* or overview* or synthes*)) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ab. or (metasynthes* or meta-synthes*).ti,ab,kf. (655318) 9 exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw. (2565224) 10 Epidemiologic studies/ or case control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or Case control.tw. or (cohort adj (study or studies)).tw. or Cohort analy$.tw. or (Follow up adj (study or studies)).tw. or (observational adj (study or studies)).tw. or Longitudinal.tw. or Retrospective*.tw. or prospective*.tw. or consecutive*.tw. or Cross sectional.tw. or Cross-sectional studies/ or historically controlled study/ or interrupted time series analysis/ [Onder exp cohort studies vallen ook longitudinale, prospectieve en retrospectieve studies] (4243432) 11 7 and 8 (1) – SRs 12 (7 and 9) not 11 (5) - RCTs 13 (7 and 10) not (11 or 12) (18) – observationele studies 14 11 or 12 or 13 (24) 15 7 not 14 (44)

|