Indicatiestelling en timing voor tracheotomie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat zijn indicaties en juiste timing voor het plaatsen van een tracheacanule bij een volwassen patiënt die op de Intensive Care afdeling is opgenomen?

Aanbeveling

Verricht niet standaard direct een tracheotomie.

Neem een beslissing over het verrichten van een tracheotomie vanaf 10 dagen na intubatie bij patiënten waar nog geen zicht is op spoedige extubatie om:

- comfort te verhogen;

- ontwennen van de beademing te bespoedigen; en/of

- mobilisatie te faciliteren.

Overwegingen

Balans tussen gewenste en ongewenste effecten

Er is literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd naar de indicaties voor verrichten van een tracheotomie bij een volwassen patiënt die op de Intensive Care afdeling is opgenomen. Er werd één systematische review (SR) geïncludeerd in de analyse van de literatuur (Andriolo, 2015), bestaande uit acht gerandomiseerde studies. Daarnaast werden er vier losse gerandomiseerde studies (RCTs) geïncludeerd (Blot, 2008; Bouderka, 2004; Saffle; 2002; Mohamed; 2004). Deze studies richten zich allen op de timing van de plaatsing van een tracheacanule (relatieve indicatie). Studies over harde indicaties voor het plaatsen van een tracheacanule werden niet gevonden. Bovendien is de gevonden literatuur relatief oud en met betrekking tot een aantal eindpunten (met name rondom mobilisatie) niet meer representatief voor de moderne praktijk. Exacte definities per studie over vroege of late tracheotomie zijn te vinden in tabel 2 van de literatuursamenvatting.

De uitkomstmaten duur van mechanische ventilatie, gebruik van sedativa, en mobilisatie werden als cruciale uitkomstmaten gedefinieerd. Complicaties, ziekenhuis mortaliteit, comfort, patiënttevredenheid, familietevredenheid, dysfagie, re-intubatie en de duur van weaning werden als belangrijke uitkomstmaten gedefinieerd.

De cruciale uitkomstmaten duur van mechanische ventilatie, gebruik van sedativa, en mobilisatie werden vergeleken tussen patiënten die een vroege tracheotomie ondergingen versus patiënten die een late tracheotomie ondergingen. De bewijskracht voor alle drie de uitkomsten wordt gegradeerd op ‘zeer laag’, wat inhoudt dat de evidentie zeer onzeker is over het feit of het gevonden effect het daadwerkelijke effect juist weerspiegelt.

Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten complicaties, patiënttevredenheid, familietevredenheid, re-intubatie en de duur van weaning werd geen literatuur gevonden. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten ziekenhuis mortaliteit, dysfagie en comfort werd wel literatuur gevonden. Echter was ook voor deze uitkomsten de bewijskracht gegradeerd op ‘zeer laag’. De overall bewijskracht van de belangrijke uitkomstmaten komt daarmee uit op zeer laag.

Kwaliteit van bewijs

De overall kwaliteit van bewijs voor de cruciale en belangrijke uitkomstmaten is zeer laag. Dit betekent dat we zeer onzeker zijn over het gevonden geschatte effect van de uitkomstmaten. Er is afgewaardeerd vanwege risico op bias (gebrek aan blindering van patiënten en beoordelaars), inconsistentie van de resultaten en imprecisie (onnauwkeurigheid, omdat de betrouwbaarheidsintervallen één of meerdere grenzen overschrijdt).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun naasten/verzorgers)

Bij de afwezigheid van sterk bewijs blijft het plaatsen van een tracheacanule een individuele afweging. De beoogde doelen van de procedure moeten worden besproken met de patiënt en/of de naasten. Hierbij is het belangrijk om de verwachtingen goed te managen. Doelen als het bestrijden van onrust, bijvoorbeeld ten gevolge van zogenoemde “tube-irritatie” of het doorbreken van een stagnerend weaningsproces, zullen niet altijd gehaald worden. Het plaatsen van een tracheacanule is vrijwel altijd een electieve procedure en er is dus ruimte voor bedenktijd bij de familie. Bij de voorlichting moet ook aandacht zijn voor een verhoogd risico op (late) bloedingscomplicaties bij patiënten met therapeutische antistolling of (dubbele) plaatjesremmers.

Het voor de patiënt gewenste effect van het plaatsen van een tracheacanule is het verhogen van het comfort, een snellere weaning, eenvoudigere mobilisatie, verbetering dysfagie en eventueel de mogelijkheid om te kunnen spreken. Ongewenste effecten kunnen zijn dat er complicaties optreden tijdens of na de plaatsing, waarbij een nabloeding de belangrijkste complicatie is. Een nabloeding is vaak met lokale maatregelen te verhelpen maar deze kunnen onprettig zijn voor een wakkere patiënt. In een zeer klein deel van de gevallen kunnen ernstige complicaties zoals het verlies van de luchtweg optreden.

Houd bij alle afwegingen rekening met de aanbevelingen uit de richtlijn Nazorg en Revalidatie van intensive care patiënten (2022).

Kostenaspecten

Er is op dit moment nog onvoldoende data beschikbaar om de kosteneffectiviteit van de interventie formeel te beoordelen. De beoogde voordelen (snellere weaning, betere mobilisatie en herstel) lijken de beperkte extra kosten te rechtvaardigen.

Gelijkheid ((health) equity/equitable)

De indicatie voor het verrichten van een tracheotomie bij IC patiënten is voor iedereen gelijk en leidt daarom naar verwachting niet tot een verschil in gezondheidsgelijkheid.

Aanvaardbaarheid

Ethische aanvaardbaarheid

Er zijn in het algemeen geen issues of bezwaren met betrekking tot ethiek in het plaatsen van een tracheacanule. In uitzonderlijke gevallen kan een comateuze patiënt die niet in staat is de eigen luchtweg vrij te houden dankzij een tracheostoma een langdurige overleving krijgen. Dit kan leiden tot ethische dilemma’s, waarbij voormalig IC patiënten met lage levenskwaliteit langdurig kunnen overleven in een verpleeghuis of vergelijkbare omgeving. Echter kan bij nader inzien ook een eerder geplaatste tracheacanule door verwijderen van de canule met adequate (palliatieve) zorg weer “ongedaan” gemaakt worden om overwegende negatieve effecten te mitigeren.

Duurzaamheid

De beperkte belasting van disposables bij de plaatsing van een tracheacanule lijkt te rechtvaardigen in het licht van het beoogde klinische doel.

Haalbaarheid

De interventie is haalbaar, want deze is over het algemeen al standaardzorg in de praktijk.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Gezien de beperkte bewijslast zijn er geen indicaties om tracheotomie standaard te verrichten bij IC patiënten. Het plaatsen van een tracheacanule kan vanaf 10 dagen overwogen worden om comfort te verhogen, weaning te bespoedigen en/of om mobiliseren te faciliteren bij patiënten waar nog geen zicht is op spoedige detubatie. Op individuele afwegingen, bijvoorbeeld bij langdurige verwachte beademingsbehoefte (>14 dagen), zoals bij patiënten met Guillain Barré of neurotrauma, kan hier bij uitzondering op afgeweken worden en kan de tracheotomie vóór de eerste 10 dagen verricht worden. In de literatuur werden geen argumenten gevonden om obesitas, status na sternotomie of het gebruik van anticoagulantia of thrombocytenaggregatieremmers als (absolute) contra-indicatie voor het plaatsen van een tracheacanule te beschouwen. De aanbeveling is conditioneel geformuleerd gezien de beperkte literatuur, welke houvast biedt over exacte indicaties en om de uitgangsvraag te ondersteunen. De aanbeveling is derhalve voornamelijk gebaseerd op klinische ervaringen.

Eindoordeel:

Richtinggevend tegen; conditioneel voor.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In general, critically ill patients in need of invasive ventilation receive mechanical ventilation via an endotracheal tube. It is a common practice to replace the initial translaryngeal tube with a tracheostomy to facilitate oral care and weaning from the ventilator. However, currently, there are no clear guidelines describing indications and contraindications to convert an endotracheal tube to a tracheostomy in critically ill patients. Such a guideline could reduce the current practice variation and inform decisions that currently may be somewhat arbitrary.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Summary of Findings

Click here to see this table in a document

|

Outcome Timeframe |

Study results and measurements |

Absolute effect estimates |

Certainty of the evidence (Quality of evidence) |

Summary |

|

|

Late tracheostomy / prolonged intubation |

Early tracheostomy |

||||

|

Complication – Pneumonia (important)

|

Relative risk: 0.84 (CI 95% 0.73 - 0.97) Based on data from 1217 participants in 9 study

|

384 per 1000 |

323 per 1000 |

Very low Due to risk of bias, imprecision, and inconsistency1 |

We are uncertain whether early tracheostomy improves or worsens complication - pneumonia |

|

Difference: 61 fewer per 1000 (CI 95% 104 fewer - 12 fewer) |

|||||

|

Dysphagia (important)

|

Relative risk: 0.51 (CI 95% 0.16 - 1.6) Based on data from 123 participants in 1 study

|

129 per 1000 |

66 per 1000 |

Very low Due to serious risk of bias, low event rate, and serious imprecision2 |

We are uncertain whether early tracheostomy increases or decreases the incidence of dysphagia |

|

Difference: 63 fewer per 1000 (CI 95% 108 fewer - 77 more) |

|||||

|

Hospital mortality (important)

|

Relative risk: 0.88 (CI 95% 0.71 - 1.1) Based on data from 1013 participants in 7 studies Follow up 28 days |

260 per 1000 |

229 per 1000 |

Very low Due to risk of bias, imprecision, and inconsistency3 |

We are uncertain whether early tracheostomy improves or worsens hospital mortality |

|

Difference: 31 fewer per 1000 (CI 95% 75 fewer - 26 more) |

|||||

|

Duration of mechanical ventilation (critical)

|

Measured by: Scale: - Lower better Based on data from 482 participants in 5 studies

|

days |

days |

Very low Due to serious risk of bias, inconsistency, and imprecision4 |

We are uncertain whether early tracheostomy increases or decreases duration of mechanical ventilation |

|

Difference: MD -4.14 lower (CI 95% -10.79 lower - 2.51 lower) |

|||||

|

Comfort (multiple outcomes) (important)

|

Measured by: A questionnaire with scale 0-10 And Days

|

|

|

Very low Due to risk of bias, and serious imprecision5 |

We are uncertain whether early tracheostomy improves or worsens comfort |

|

Criteria evaluated in the self-evaluation questionnaire were in favour of tracheostomy.

No differences regarding recovery time of oral feeding and speech |

|||||

|

Mobilization (chair positioning) (critical)

|

Measured by: Day of first transfer from bed to chair Scale: - Lower better

|

20 Median |

22 Median |

Very low Due to serious risk of bias, and imprecision6 |

We are uncertain whether early tracheostomy improves or worsens mobilization (chair positioning) |

|

|

|||||

|

Use of sedatives (critical)

|

Measured by: Sedation-free days Scale: 0 - 27 Lower better

|

15 Median |

18 Median |

Very low Due to very serious risk of bias, Due to serious imprecision7 |

Early tracheostomy may have little or no difference on sedation use |

|

|

|||||

|

Complications – peri-procedural mortality (important) Complications – bleeding (important) Complications - Accidental extubation/loss of airway (important) Patient satisfaction (important) Family satisfaction (important) Dysphagie (important) Reintubation (important) Weaning duration (important) |

- |

- |

No GRADE (no evidence was found) |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of tracheostomy on Complications – peri-procedural mortality, Complications – bleeding, Complications - Accidental extubation/loss of airway, Patient satisfaction, Family satisfaction, Dysphagia, Reintubation, Weaning duration |

|

1. Risk of Bias: serious. Inadequate/lack of blinding of participants and personnel, resulting in potential for performance bias; Inconsistency: serious. The direction of the effect is not consistent between the included studies; Imprecision: serious. Wide confidence intervals.

2. Risk of Bias: serious. Inadequate/lack of blinding of participants and personnel, resulting in potential for performance bias, due to recruitment bias; Imprecision: very serious. Wide confidence intervals.

3. Risk of Bias: serious. Inadequate/lack of blinding of participants and personnel, resulting in potential for performance bias; Inconsistency: serious. The direction of the effect is not consistent between the included studies; Indirectness: no serious. Differences between the outcomes of interest and those reported (e.g short-term/surrogate, not patient-important); Imprecision: serious. Wide confidence intervals.

4. Risk of Bias: serious. Inadequate/lack of blinding of participants and personnel, resulting in potential for performance bias; Inconsistency: serious. The direction of the effect is not consistent between the included studies; Imprecision: very serious. Wide confidence intervals.

5. Risk of Bias: very serious. Inadequate/lack of blinding of participants and personnel, resulting in potential for performance bias, due to recruitment bias; Imprecision: serious. Wide confidence intervals.

6. Risk of Bias: very serious. Inadequate/lack of blinding of participants and personnel, resulting in potential for performance bias, due to recruitment bias; Imprecision: serious. Wide confidence intervals.

7. Risk of Bias: very serious. Inadequate/lack of blinding of participants and personnel, resulting in potential for performance bias, due to recruitment bias; Imprecision: serious. Wide confidence intervals.

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

A total of five studies (one systematic review describing eight different studies, and four randomized controlled trials) were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in table 2. In the analysis of the literature we included multiple definitions for the control group, e.g., either prolonged intubation or late tracheostomy. The exact intervention and control, and the definition of the comparison, can also be found in table 2.

Andriolo (2015) performed a systematic review to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of early (≤ 10 days after tracheal intubation) versus late tracheostomy (> 10 days after tracheal intubation) in critically ill adults predicted to be on prolonged mechanical ventilation with different clinical conditions. The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2013, Issue 8); MEDLINE (via PubMed) (1966 to August 2013); EMBASE (via Ovid) (1974 to August 2013); LILACS (1986 to August 2013); PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database) at www.pedro.fhs.usyd.edu.au (1999 to August 2013) and CINAHL (1982 to August 2013) were searched. The review included all (quasi-) RCTs that met the following inclusion criteria. For types of patients, the inclusion criteria were 1) Critically ill patients (for whom death is possible or imminent); 2) Patients expected to be on prolonged mechanical ventilation; and 3) Adults (≥ 18 years). Inclusion criteria for the type of intervention was 1. Early tracheostomy, if no serious attempt was made to wean the patient from the ventilator (tracheostomy based only on clinical or laboratory results and performed from two days to 10 days after intubation); and 2) late tracheostomy, if weaning had not been successful; performed later than 10 days after intubation. Eight studies were included.

Mohamed (2014) performed a single center prospective randomized study on 40 patients who underwent bedside percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy (PDT). Patients included were older than 18 years, were mechanically ventilated for respiratory failure>24 h and have had no previous pulmonary infection by chest X-ray.

Blot (2008) performed a multicenter prospective randomized trial in twenty-five medical and surgical ICUs in France. Patients with ‘‘main underlying pathology’’ coded ‘‘neurological’’ were included; the study database did not record if this underlying neurological pathology was acute or not (personal communication with study authors). Patients were excluded if they had an irreversible neurological disease or post-trauma intracranial hypertension (intracranial pressure >20 cmH2O and/or cerebral edema on head CT scan).

Bouderka (2004) performed a single-center prospective randomized trial in one ICU in Morrocco. Patients were included in the study if they met the following criteria: isolated severe head injury (admission Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score ≤8); cerebral contusion on CT scan; GCS score <8 on the fifth day without any sedation.

Saffle (2002) performed a single-center prospective randomized trial in the Intermountain Burn Center in the United States. Patients were eligible if they were older than 18 years of age, hospitalized within 24 hours of acute burn injury, and if they required ongoing mechanical ventilatory support on postburn day (PBD)2 (ie, 48–72 hours postinjury). All intubated patients were evaluated for the presence of inhalation injury using fiberoptic bronchoscopy. The following patients were excluded from participation in the study: 1) pregnant women; 2) patients with preexisting significant renal or hepatic disease; 3) patients taking corticosteroids prior to admission; and 4) patients who did not have cutaneous burn injuries.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies

|

Study |

Participants |

Comparison |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures |

Comments |

Risk of bias (per outcome measure)* |

|

Included in systematic review Andriolo, 2015 (n=8) |

||||||

|

Barquist, 2006 |

N at baseline Intervention: 29 Control: 31

Mean age: 51.8 (whole sample), range: 18 to 87

Gender: 46 male/ 14 female (whole sample) |

Intervention: Early tracheostomy: before day 8

Control: Late tracheostomy: after day 28 †

Comparison: early tracheostomy vs late tracheostomy |

30 days |

Duration of mechanical ventilation (measured as mean ventilation-free days at day 30), complications (measured as ventilator-associated pneumonia; and major complications related to the tracheostomy) |

Although times of follow-up were explicitly announced for some outcomes (mean ventilation-free days at day 30), study authors did not explicitly report follow-up times for the other outcome data |

Moderate risk |

|

Bösel, 2013 |

N at baseline Intervention: 30 Control: 30

Mean age: 61 (whole sample)

|

Intervention: Early tracheostomy: percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy (PDT) within 3 days from intubation

Control: Late tracheostomy: PDT between days 7 and 14 from intubation if extubation, although aimed for, was not possible until then.

Comparison: early tracheostomy vs late tracheostomy |

6 months |

Duration of mechanical ventilation (measured as sum of half-days on the ventilator until the participant was ventilator-independent for 24 hour); Weaning duration (measured as sum of half-days spent under the possible application of a weaning protocol, and spent within specific stepwise phases of such a protocol); and complications (frequency of pneumonia, sepsis, and types of complications associated with the procedure (bleeding, malfunction, etc) |

|

Moderate risk |

|

Dunham, 1984 |

N at baseline Intervention: 34 Control: 40

Age (range): 17 – 75 (whole sample)

|

Intervention: early group (transtracheal intubation at 3 to 4 days after initiation of translaryngeal Intubation)

Control: late group (transtracheal intubation performed 14 days after initiation of translaryngeal intubation, if continued intubation was required)

Comparison: early tracheostomy vs late tracheostomy |

|

Complications (pneumonia and other complications) |

No information provided on gender. There was high risk of bias due to insufficient randomization and allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. |

High risk |

|

Rumbak, 2004 |

N at baseline Intervention: 60 Control: 60

Mean age: 63 (whole sample)

Gender: 65 male/ 55 female (whole sample) |

Intervention: Tracheostomy within 48 hours after intubation Control: Late tracheostomy at days 14 to16

Comparison: early tracheostomy vs late tracheostomy |

|

Duration of mechanical ventilation (measured as days mechanically ventilated); sedative use (measures as days sedated), complications (measured as pneumonia, gastrointestinal bleed, and acute myocardial infarction) |

Random sequence generation not explicitly mentioned. Although the airways were assessed for oral, laryngeal and tracheal damage at 10 weeks post intubation, no explicit information was provided about time of follow-up for the other outcomes |

Moderate risk |

|

Terragni, 2010 |

N at baseline Intervention: 209 Control: 210

Mean age: 61.5 (whole sample)

Gender: 138 male/142 female (whole sample)

|

Intervention: Early tracheostomy: after 6 to 8 days of laryngeal intubation

Control: Late tracheostomy: after 13 to 15 days of laryngeal intubation

Participants from both groups were subjected to percutaneous tracheostomy

Comparison: early tracheostomy vs late tracheostomy |

|

Duration of mechanical ventilation (measured as ventilator-free days (at day 28)), complications (measured as ventilator associated pneumonia), adverse events |

This study was supported by the Regione Piemonte Ricerca Sanitaria Finalizzata grant 03-08/ACR ASx44, which had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript |

Moderate risk |

|

Trouillet, 2011 |

N at baseline Intervention: 109 Control: 107

Mean age: 65 (whole sample)

Gender: male, 66% (n=143) |

Intervention: Early tracheostomy (before the end of calendar day 5 after surgery)

control Prolonged intubation with tracheostomy only when mechanical ventilation exceeded day 15 after randomization

Comparison: early tracheostomy vs late tracheostomy |

90 days |

Duration of mechanical ventilation (measured as ventilator-free days), and days of MV during 1 to 60 days), use of sedatives |

Funding: French Ministry of Health. The study sponsor did not participate in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing or the decision to submit this manuscript for publication |

Moderate risk |

|

Young, 2013 |

N at baseline Intervention: 455 Control: 454

Mean age: 63.9 (whole sample)

Gender: male, 58.6% (n=527) |

Intervention: Early tracheostomy: within 4 days of mechanical ventilation

Control: Late tracheostomy: after 10 days of mechanical ventilation

Comparison: early tracheostomy vs late tracheostomy |

|

- |

This study was supported by the University of Oxford, the UK Intensive Care Society and the Medical Research Council, which had no influence on the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript. The randomization service was provided by the Health Services Research Unit at the University of Aberdeen |

Moderate risk |

|

Zheng, 2012 |

N at baseline Intervention: 58 Control: 61

Age (mean, SD) Intervention: 67.5±14.7 Control: 67.9±17.6

Sex (Male (n (%)) Intervention: 39 (67.2%) Control: 35 (57.4%)

|

Intervention: early PDT group (patients tracheostomized with PDT on day 3 of MV)

Comparison: Late PDT group (patients tracheostomized with PDT on day 15 of MV if they still needed MV)

Comparison: early tracheostomy vs late tracheostomy

|

60 days |

Duration of mechanical ventilation (measured as ventilator-free days at day 28 after randomization), use of sedatives (measured as sedation-free days at day 28 after randomization), weaning duration (measured as successful weaning rate at day 28 after randomization), and complications (measured as: the incidence of ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP); intraoperative complications; and postoperative complications) |

RoB due to inadequate blinding and loss to follow up in the control group and not in the intervention group.

Comment by authors: the bed to nurse ratio in our ICU was 1:2.5 during the period of this study. Insufficient nurses might have increased incidence of VAP,28 and might in turn have increased duration of MV, length of ICU stay, and mortality in the studied cohort |

Moderate risk |

|

Separate RCTs (n=4) |

||||||

|

Mohamed (2014) |

N at baseline Intervention: 20 Control: 20

Age (mean, SD) Intervention: 55.30±20.13 Control: 59.95±18.47

Sex (Male (n (%)) Intervention: 19 (95%) Control: 14 (70%) |

Intervention: Early PDT (tracheostomy within the first 10 days of MV)

Comparison/control: late PDT (tracheostomy after 10 days of MV)

Comparison: early tracheostomy vs late tracheostomy |

Not mentioned |

number of days from the initiation of ventilation to tracheostomy, from tracheostomy to weaning (the duration of mechanical ventilation), from tracheostomy to discharge from ICU (length of stay) and hospital length of stay. |

No conflict of interest declared.

Small study sample. |

Moderate risk |

|

Blot, 2008 |

N at baseline Intervention: 61 Control: 62

Age (median, range) Intervention: 55 (19 – 88) Control: 58 (20-88)

Sex Intervention male: 45 (74%) Control male: 43 (69%) |

Intervention: early tracheostomy (≤4 days) Control: prolonged intubation*

Definition comparison: early tracheostomy vs prolonged intubation |

60 days |

Mobilization, complications, duration of mechanical ventilation, use of sedation, comfort, and dysphagia |

The treatment could not be blinded, there is a high chance of recruitment bias, and the study is underpowered. |

High risk

|

|

Bouderka, 2004 |

N at baseline Intervention: 31 Control: 31

Age (mean, SD) Intervention: 41.1, 17.5 Control: 40, 19

Sex Intervention (male): 58% Control (male): 65% |

Intervention: early tracheostomy (5-6 days) Control: prolonged intubation

Definition comparison: early tracheostomy vs prolonged intubation |

Presumed short-term |

Complications and duration of mechanical ventilation |

The treatment could not be blinded. |

Moderate risk |

|

Saffle, 2002 |

N at baseline Intervention: 21 Control: 23

Age (mean, SD) Intervention: 44.5, 4.3 Control: 51.3, 4.0

Sex Intervention: NR Control: NR |

Intervention: early tracheostomy Control: conventional therapy***

Definition comparison: early tracheostomy vs prolonged intubation |

Not mentioned, But longest length of stay 153 days. |

Duration of mechanical ventilation. |

The treatment could not be blinded. |

Moderate risk |

PDT: percutaneous dilutional tracheostomy; VAP: ventilator associated pneumonia

*Patients in control group could not receive tracheostomy until at least 14 days after translaryngeal intubation, 16 ultimately received a tracheostomy

**For further details, see risk of bias table in the appendix

***Continued endotracheal intubation as needed, with tracheostomy performed on postburn day 14 if necessary

† 4 participants in the 'late’ group had a surgical tracheostomy placed on days 17, 18, 19 and 21 to facilitate transfer to long-term care

Results

Duration of mechanical ventilation (critical)

Two of the eight studies in the review of Andriolo (2015) reported the outcome mean days of mechanical ventilation during 1 to 60 days (Rumbak, 2004; Trouillet, 2011). The other four studies also reported the outcome mechanical ventilation duration (Blot, 2008; Bouderka, 2004; Saffle; 2002; Mohamed; 2004).

Since Blot (2008) reported the median (range) duration of mechanical ventilation during the first 28 days, these results could not be used in the pooled analysis. Blot (2008) reported a median (range) duration in severely ill ICU patients of 14 (2 – 18) days for the early tracheostomy group (n=61) and 16 (3-28) days for the prolonged intubation group (n=62).

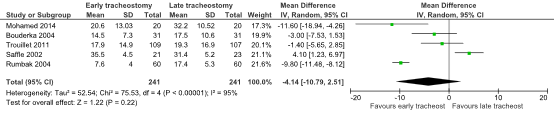

The combined mean difference in the duration of mechanical ventilation in days was 4.14 (95% CI: -10.79 to 2.51) in favour of the early tracheostomy group. This difference was considered to be clinically relevant.

Figure 1. The Mean Difference (MD) in the duration of mechanical ventilation (in days) between ICU-patients receiving early of late tracheostomy

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Use of sedatives (critical)

The outcome use of sedatives was reported in one study (Blot, 2008).

Blot (2008) reported on the outcome sedation and measured the number of sedation-free days within the first 28 days. The median (range) of sedation-free days were 18 days (0 to 27) in de early tracheostomy group (n=61) and 15 days (0 to 27) in the prolonged intubation group (n=62). This difference was considered to be clinically relevant.

Mobilization (critical)

The outcome mobilization was reported in one study (Blot, 2008).

Blot (2008) reported the outcome chair positioning on day 28 and day 60, which was measured as the time of the first transfer from bed to chair. In the early tracheostomy group (n=61) the chair positioning rate on day 28/day 60 was 80%/100% with a median time (95% CI) of 20 days (15-23), compared to 65%/88%, and a median time of 22 days (16-28), in the prolonged intubation group (n=61). Since the mean was not reported, the mean difference could not be calculated. Therefore, it could not be determined whether this difference is clinically relevant.

Complications (important)

Pneumonia

Five of the eight studies in the review of Andriolo (2015) reported the incidence rate of pneumonia, defined as the incidence of ICU-acquired pneumonia within 28 days. (Dunham 1984; Rumbak 2004; Terragni 2010; Trouillet 2011; Zheng 2012). In addition, the four separate studies also reported on the incidence rate of pneumonia (Blot, 2008; Bouderka, 2004; Saffle; 2002; Mohamed; 2004).

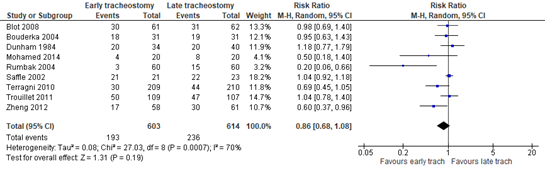

The combined percentage of pneumonia events in the early tracheostomy group is 32.0% (193 out of 603 patients), versus 38.4% (236 out of 614 patients) in the late tracheostomy group, with a risk ratio (RR) of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.68 to 1.08). The risk difference (RD) was calculated using the baseline risk (BR) from the PRECISe Trial (Bels et al., 2024), which included Dutch and Belgium patients. Based on the incidence of ventilator-acquired pneumonia in this population, which was 115 of the 465 (25%), the RD is -0.035 (95%CI: -0.08 to 0.02), in favour of the early tracheostomy group. The RD of -0.035 represents a difference of 3.5%, which was not considered to be clinically relevant.

Figure 2. The Risk Ratio (RR) for the number of pneumonia events in ICU-patients receiving either early of late tracheostomy

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Peri-procedural mortality

The outcome ‘peri-procedural mortality’ was not reported in the included randomized controlled trial of Andriolo (2014) or the four separate randomized controlled trials (Blot, 2008; Bouderka, 2004; Saffle; 2002; Mohamed; 2004).

Bleeding

The outcome ‘bleeding’ was not reported in the included randomized controlled trial of Andriolo (2014) or the four separate randomized controlled trials (Blot, 2008; Bouderka, 2004; Saffle; 2002; Mohamed; 2004).

Accidental extubation/loss of airway

The outcome ‘accidental extubation/loss of airway’ was not reported in the included randomized controlled trial of Andriolo (2014) or the four separate randomized controlled trials (Blot, 2008; Bouderka, 2004; Saffle; 2002; Mohamed; 2004).

Hospital mortality (important)

Three of the eight studies in the review of Andriolo (2015) reported mortality on day 28 (Terragni 2010; Trouillet 2011; Zheng 2012), in addition to one of the separate studies (Blot, 2008). The other three separate studies also reported hospital mortality, although not explicitly mentioned on which day the outcome was measured (Bouderka, 2004; Saffle; 2002; Mohamed; 2004).

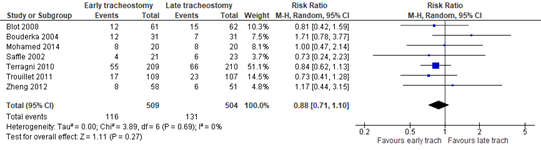

In total, 116 of the 509 patients died in the early tracheostomy group, compared to 131 of the 504 patients in the late tracheostomy/prolonged intubation group. The incidence in the late tracheostomy group does not represent the Dutch population. Unfortunately, due to the absence of a Dutch baseline risk we could not adapt the RD to the Dutch population. Therefore, the RD might not represent the Dutch situation. The outcome mortality had a RR of 0.88 (95%CI: 0.71 to 1.10) and a RD of -0.03 (95%CI: -0.08 to 0.02), in favour of the early tracheostomy group. The RD of 3% was not considered to be clinically relevant.

Figure 3. The Risk Ratio (RR) for mortality in ICU-patients receiving either early of late tracheostomy

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Comfort (important)

One study reported on the outcome comfort (Blot, 2008).

Blot (2008) reported on self-evaluated comfort using a questionnaire and on objective comfort criteria evaluated on day 28 and day 60, including the time of recovery time of oral feeding and speech. Results are expressed according to a numerical scale from 1 (acceptable) to 10 (unbearable). Most of the criteria evaluated in the self-evaluation questionnaire were in favour of tracheostomy. The differences in the following criteria, all in favour of early tracheostomy, were considered clinically relevant: difficulty to move (early tracheostomy: 2 (1-7); prolonged intubation: 5 (1-10)), mouth discomfort (early tracheostomy: 2 (1-10); prolonged intubation: 5 (1-10)), feeling of mouth cleanliness (early tracheostomy: 3 (1-8); prolonged intubation: 5 (2-10)), feeling of overall safety (early tracheostomy: 1 (1-10); prolonged intubation: 4 (1-9)), perception of change in body image (early tracheostomy: 3 (1-7); prolonged intubation: 5 (1-9)), and overall feeling of comfort (early tracheostomy: 3 (1-9); prolonged intubation: 5 (1-8)). In addition, all patients who had completed the self-evaluation questionnaire and had undergone both trans-laryngeal intubation and early or late tracheostomy (n=13) considered that the tracheostomy, and not prolonged intubation, was the most comfortable technique.

There were no differences regarding the recovery time of oral feeding (early tracheostomy group (n=61): recovery on d28/d60: 64%/91%; median time (95%) 18 days (13-28); prolonged intubation group (n=62); recovery on d28/d60: 64%/86%; median time (95%): 23 days (20-27)), and speech recovery (early tracheostomy group (n=61): recovery on d28/d60: 57%/83%; median time (95%) 26 days (18-32); prolonged intubation group (n=62); recovery on d28/d60: 63%/85%; median time (95%): 22 days (16-30)). Since the median, and not the mean, was reported, the mean difference could not be calculated. Therefore, it could not be determined whether this difference is clinically relevant.

Patient satisfaction (important)

The outcome ‘patient satisfaction’ was not reported in the included randomized controlled trial of Andriolo (2014) or the four separate randomized controlled trials (Blot, 2008; Bouderka, 2004; Saffle; 2002; Mohamed; 2004).

Family satisfaction (important)

The outcome ‘Family satisfaction’ was not reported in the included randomized controlled trial of Andriolo (2014) or the four separate randomized controlled trials (Blot, 2008; Bouderka, 2004; Saffle; 2002; Mohamed; 2004).

Dysphagia (important)

One study reported on the outcome dysphagia (Blot, 2008).

Blot (2008) reported on the outcome swallowing disorders, which belonged to the laryngeal symptoms. In the early tracheostomy group, 4 of the 61 (6.6%) patients experienced a swallowing disorder compared to 8 of the 62 (12.9%) patients in the prolonged intubation group. The incidence in the late tracheostomy group does not represent the Dutch population. Unfortunately, due to the absence of a Dutch baseline risk we could not adapt the RD to the Dutch population. Therefore, the RD might not represent the Dutch situation. The outcome dysphagia had a RR of 0.51 (95% CI: 0.16 to 1.60) and a RD of 0.06 (95% CI: -0.17 to 0.04), in favour of the early tracheostomy group. The RD of 6% in the incidence of swallowing disorders was not considered to be clinically relevant.

Reintubation (important)

The outcome ‘reintubation’ was not reported in the included randomized controlled trial of Andriolo (2014) or the four separate randomized controlled trials (Blot, 2008; Bouderka, 2004; Saffle; 2002; Mohamed; 2004).

Weaning duration (important)

The outcome ‘weaning duration’ was not reported in the included randomized controlled trial of Andriolo (2014) or the four separate randomized controlled trials (Blot, 2008; Bouderka, 2004; Saffle; 2002; Mohamed; 2004).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question(s):

What is the effectiveness of tracheostomy versus no tracheostomy and early tracheostomy versus prolonged intubation or late tracheostomy in critically ill adult patients who are intubated?

Table 1. PICO

| Patients | Critically ill adult patients in the ICU who are intubated |

| Intervention | 1. Tracheostomy 2. Early tracheostomy |

| Control |

1. No tracheostomy 2. Prolonged intubation or late tracheostomy |

| Outcomes | Duration of mechanical ventilation, mobilization, use of sedatives, complications, hospital mortality, comfort, patient satisfaction, family satisfaction, dysphagia, reintubation, weaning duration |

| Other selection criteria |

Study design: systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials >10 patients per group |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline panel considered duration of mechanical ventilation, mobilization, and use of sedatives as critical outcome measures for decision making; and complications, comfort, patient satisfaction, family satisfaction, dysphagia, reintubation, weaning duration, and hospital mortality as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the guideline panel did not define the outcome measures duration of mechanical ventilation, patient satisfaction, family satisfaction, dysphagia, reintubation, and weaning duration, but used the definitions used in the studies. The guideline panel defined the other outcomes outcome measures as follows:

- Mobilization: active motion, in or out of bed.

- Use of sedatives: midazolam, propofol, dexmedetomidine or other benzodiazepines.

- Complications: Peri-procedural mortality, bleeding, accidental extubation/loss of airway, pneumonia.

- Comfort: either self-reported or as an objective measure such as resumption of oral feeding or speech recovery.

The guideline panel defined the following thresholds as minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

- Duration of mechanical ventilation: ≥1 day

- Mobilization: 0.5 SD

- Use of sedatives (sedation-free days): ≥1 day

- Complications: Risk difference of ≥5%, except for peri-procedural mortality, then risk difference of ≥1%

- Hospital mortality: Risk difference of ≥3.5%

- Comfort: 0.5 SD, and on the 1-10 scale ≥ 2 points

- Patient satisfaction: 0.5 SD

- Family satisfaction: 0.5 SD

- Dysphagia: Risk difference of ≥10%

- Reintubation: Risk difference of ≥10%

- Weaning duration: ≥1 day

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 27-06-2024. The detailed search strategy is listed under the tab ‘Literature search strategy’. The systematic literature search resulted in 698 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria ‘intubated ICU patients’ AND ‘tracheostomy’ AND adults. Initially, 48 studies were selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 43 studies were excluded (see the exclusion table under the tab ‘Evidence tabellen’), and five studies were included.

Referenties

- Andriolo, B. N., Andriolo, R. B., Saconato, H., Atallah, Á. N., & Valente, O. (2015). Early versus late tracheostomy for critically ill patients. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (1).

- Barquist, E. S., Amortegui, J., Hallal, A., Giannotti, G., Whinney, R., Alzamel, H., & MacLeod, J. (2006). Tracheostomy in ventilator dependent trauma patients: a prospective, randomized intention-to-treat study. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 60(1), 91-97.

- Bels, J. L., Thiessen, S., van Gassel, R. J., Beishuizen, A., Dekker, A. D. B., Fraipont, V., ... & Deane, A. (2024). Effect of high versus standard protein provision on functional recovery in people with critical illness (PRECISe): an investigator-initiated, double-blinded, multicentre, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial in Belgium and the Netherlands. The Lancet, 404(10453), 659-669.

- Blot, F. and Similowski, T. and Trouillet, J. L. and Chardon, P. and Korach, J. M. and Costa, M. A. and Journois, D. and Thiéry, G. and Fartoukh, M. and Pipien, I. and Bruder, N. and Orlikowski, D. and Tankere, F. and Durand-Zaleski, I. and Auboyer, C. and Nitenberg, G. and Holzapfel, L. and Tenaillon, A. and Chastre, J. and Laplanche, A. Early tracheostomy versus prolonged endotracheal intubation in unselected severely ill ICU patients. Intensive Care Medicine. 2008; 34 (10) :1779-1787

- Bouderka, M. A. and Fakhir, B. and Bouaggad, A. and Hmamouchi, B. and Hamoudi, D. and Harti, A. Early tracheostomy versus, prolonged endotracheal intubation in severe head injury. Journal of Trauma - Injury, Infection and Critical Care. 2004; 57 (2) :251-254

- Bösel, J., Schiller, P., Hook, Y., Andes, M., Neumann, J. O., Poli, S., ... & Steiner, T. (2013). Stroke-related early tracheostomy versus prolonged orotracheal intubation in neurocritical care trial (SETPOINT) a randomized pilot trial. Stroke, 44(1), 21-28.

- DUNHAM, C. M., & LaMONICA, C. O. N. N. I. E. (1984). Prolonged tracheal intubation in the trauma patient. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 24(2), 120-124.

- Mohamed, K. A. E., Mousa, A. Y., ElSawy, A. S., & Saleem, A. M. (2014). Early versus late percutaneous tracheostomy in critically ill adult mechanically ventilated patients. Egyptian Journal of Chest Diseases and Tuberculosis, 63(2), 443-448.

- Rumbak, M. J., Newton, M., Truncale, T., Schwartz, S. W., Adams, J. W., & Hazard, P. B. (2004). A prospective, randomized, study comparing early percutaneous dilational tracheostomy to prolonged translaryngeal intubation (delayed tracheostomy) in critically ill medical patients. Critical care medicine, 32(8), 1689-1694.

- Saffle, J. R. and Morris, S. E. and Edelman, L. Early tracheostomy does not improve outcome in Burn patients. Journal of Burn Care and Rehabilitation. 2002; 23 (6) :431-438

- Terragni, P. P., Antonelli, M., Fumagalli, R., Faggiano, C., Berardino, M., Pallavicini, F. B., ... & Ranieri, V. M. (2010). Early vs late tracheostomy for prevention of pneumonia in mechanically ventilated adult ICU patients: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 303(15), 1483-1489.

- Trouillet, J. L., Luyt, C. E., Guiguet, M., Ouattara, A., Vaissier, E., Makri, R., ... & Combes, A. (2011). Early percutaneous tracheostomy versus prolonged intubation of mechanically ventilated patients after cardiac surgery: a randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine, 154(6), 373-383.

- Young, D., Harrison, D. A., Cuthbertson, B. H., Rowan, K., & TracMan Collaborators. (2013). Effect of early vs late tracheostomy placement on survival in patients receiving mechanical ventilation: the TracMan randomized trial. Jama, 309(20), 2121-2129.

- Zheng, Y., Feng, S. U. I., Chen, X. K., Zhang, G. C., Wang, X. W., Song, Z. H. A. O., ... & Li, W. X. (2012). Early versus late percutaneous dilational tracheostomy in critically ill patients anticipated requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation. Chinese medical journal, 125(11), 1925-1930.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 26-01-2026

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 26-01-2026

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire cluster ingesteld. Het cluster Intensive Care bestaat uit meerdere richtlijnen, zie hier voor de actuele clusterindeling. De stuurgroep bewaakt het proces van modulair onderhoud binnen het cluster. De expertisegroepsleden geven hun expertise in, indien nodig. De volgende personen uit het cluster zijn betrokken geweest bij de herziening van deze module:

Clusterstuurgroep

- Dr. E.J. Wils, voorzitter, internist-intensivist, Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland, Rotterdam

- Dhr. K.H. de Groot, internist-intensivist, Máxima MC, Eindhoven

- Dhr. E.J. van Lieshout, internist-intensivist, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam

- Dr. J. van Paassen, internist-intensivist, LUMC, Leiden

- Prof. dr. K. Kaasjager, internist, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht

- Dhr. R.M. Wilting, chirurg-intensivist, Elisabeth-TweeSteden Ziekenhuis, Tilburg

- Mevr. S.J. Bakker, longarts-intensivist, Elkerliek Ziekenhuis, Helmond

- Dhr. R. van Vugt, anesthesioloog-intensivist, Sint Maartenskliniek, Nijmegen

- Dr. S.W.M. de Jong, longarts-intensivist, Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland, Rotterdam

Clusterexpertisegroep

- Dr. M.C.G. van de Poll, chirurg-intensivist, MUMC+, Maastricht

- Dr. T. Frenzel, anesthesioloog-intensivist, Radboudumc, Nijmegen

Met ondersteuning van

- Drs. F.M. Janssen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. L. Wesselman, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

Een overzicht van de belangen van de clusterleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten via secretariaat@kennisinstituut.nl.

Gemelde (neven)functies en belangen stuurgroep

|

Naam |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Restrictie |

|

Wils |

Intensivist, Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland, Rotterdam (betaald) |

MICU-arts Zuidwest Nederland (betaald) Intensivist/arts-onderzoeker, ErasmusMC, Rotterdam (GVO; onbetaald) Lid Richtlijnencommissie NVIC (onbetaald) Taskforce 'Acute Infectiologische Bedreigingen' (onbetaald) Lid commissie kwaliteit NVIC (onbetaald) Lid commissie Wetenschap & Innovatie (onbetaald) Bestuurslid stichting Heilige Geest Huis (onbetaald) |

NORMO2 project (ZonMW projectnummer 10430102110007) Normo2: Niet-invasieve respiratoire ondersteuning bij COVID-19 longfalen: uitkomsten en risicofactoren (geen projectleider)

Beterketen: Harmoniseren, optimaliseren en verbeteren van nazorg na intensive Care behandeling (geen projectleider) |

Geen restricties |

|

Van Paassen |

Instituut: LUMC |

Lid Richtlijnencommissie NVIC (onbetaald) Lid Task force Acute infectiologische bedreigingen (onbetaald) Plaatsvervangend opleider IC (onbetaald) |

ZonMw Sparcs@ICU Antimicrobial steardship programs in the Dutch ICUs: a theory-to-practice Gap analysis, rol als projectleider |

Geen restricties |

|

De Groot |

Instituut: Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland Functie: Internist - intensivist Werkzaamheden: Klinisch |

Richtlijn commissie NVIC (onbetaald) Klankbordgroep Richtlijn bloeding tractus digestivus (onbetaald) |

REMAP-CAP, lokale hoofdonderzoeker |

Geen restricties |

|

Van Lieshout |

internist-intensivist, Amsterdam UMC, Intensive Care, locatie AMC |

onbetaald: |

nvt |

Geen restricties |

|

Kaasjager |

internist acute geneeskunde UMCU UU/Gelre 0.8 FTE |

bestuur NVIAG, onbetaald, |

nvt |

Geen restricties |

|

Wilting |

Chirurg-intensivist, Elisabeth-TweeSteden ziekenhuis Tilburg |

Landelijk/extern: Instructeur diverse cursussen (ATLS, HMIMS, basiscursus echografie NVIC) (onkostenvergoeding) Visiteur kwaliteitsvisitatie NVIC (onkostenvergoeding) Regio intensivist IC regio ZWN (geen vergoeding)

Ziekenhuis/intern (allen zonder vergoeding): Medisch Manager IC Tactisch planningsoverleg Kernteam kwaliteit en veiligheid Commissie nieuwbouw acute as Trauma commissie |

Nvt |

Geen restricties |

|

Bakker |

Longarts-intensivist Elkerliek Ziekenhuis Helmond |

Stuurgroeplid & instructeur Bronchoscopie echo thorax en tracheostomie cursus MUMC

Partner is orthopedisch chirurg in JBZ (geen belangenverstrengeling) |

|

Geen restricties |

|

Van Vugt |

Anestesioloog, Sint Maartenskliniek (loondienst) |

Stuurgroep Epilepsie (vacatiegelden) |

|

Geen restricties |

|

De Jong |

Longarts Intensivist ZGT Almelo |

FMS - Netwerk Startend Medisch Specialist - Onebtaald NVIC - Werkgroep arbeidsmarktproblematiek - Onbetaald NVALT - Sectie IC - Onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

Gemelde (neven)functies en belangen expertisegroep

|

Naam |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Restrictie |

|

Van de Poll |

Chirurg-Intensivist Maastricht UMC+ |

Geen |

PRECISe trial, sponsor Maastricht UMC+, financier ZonMW, KCE, Nutricia, onderwerp eiwitrijke voeding bij IC patienten INCEPTION trial sponsor MUMC+, financier ZonMW, Getinge, onderwerp hartlongmachine bij reanimatie MAAS studie sponsor MUMC+, financier Fresenius kabi, onderwerp eiwitmetabolisme in sepsis

Principal Investigator PRECISe trial Principal Investigator INCEPTION trial Principal Investigator MAAS studie

Travel fee, speaker fee Nutricia Consultancy fee Nestlé, Nutricia |

Restricties in besluitvorming m.b.t. voedingsgerelateerde onderwerpen. |

|

Frenzel |

Intensivist Radboudumc Nijmegen |

Geen |

Lokale PI PREVENT study (Liberate medical) |

Geen restricties |

Gemelde (neven)functies en belangen ondersteuning Kennisinstituut

|

Naam |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Restrictie |

|

Janssen |

Adviseur Kennisinstituut |

PhD-kandidaat UMCU |

Vader werkzaam als directeur bij EMCM |

Geen restricties |

|

Wesselman |

Senior adviseur Kennisinstituut |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijnmodule voerden de clusterleden conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uit om te beoordelen of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema bij Werkwijze).

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Indicatiestelling en timing voor tracheotomie |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en zal daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

Werkwijze

Voor meer details over de gebruikte richtlijnmethodologie verwijzen wij u naar de Werkwijze. Relevante informatie voor de ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule is hieronder weergegeven.