Geluidsverrijkende therapie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat zijn de (on)gunstige effecten van geluidsverrijkende therapie (zoals muziektherapie en maskeerders) bij patiënten met chronische subjectieve tinnitusklachten?

Aanbeveling

Verricht bij patiënten met chronische tinnitusklachten geen geluidsverrijkende therapie (tinnitusmaskeerder) als onderdeel van klinische behandeling.

Overweeg bij patiënten met gehoorverlies en tinnitus een proef met hoortoestellen als gehoorherstellende therapie.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de effectiviteit van geluidsverrijkende therapie ten opzichte van afwachten, placebo of sham controle en gebruikelijke zorg bij patiënten met chronische subjectieve tinnitus. Er zijn twee systematische reviews en twee RCTs gevonden over geluidsverrijkende therapie die zijn uitgewerkt. Deze studies onderzochten de cruciale uitkomstmaat tinnitus-last voor verschillende vergelijkingen. Voor de vergelijking tinnitusmaskeerders versus wachtlijst control werd gevonden dat tinnitus masking de tinnitus-last (gemeten door middel van THI) mogelijk vermindert. Voor de vergelijking combinatie hoortoestel versus hoortoestel werd geen klinisch relevant verschil in tinnitus last gevonden. Voor de overige vergelijkingen werd een lage tot zeer lage bewijskracht gevonden. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten kwaliteit van leven en ernstige bijwerkingen ontbrak het aan bewijs. Hier ligt dus een kennislacune.

De gevonden winst van verschillende geluidsverrijkende therapieén op tinnitusklachten berust enkel op (zeer) lage bewijskracht en er is op basis daarvan geen zekerheid over de uitkomst. Uit de literatuur blijkt bijvoorbeeld ook dat met enkel counseling vergelijkbare effecten bereikt kunnen worden (Scherer, 2019; Xiang, 2020).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Tinnitus is een veelvoorkomend, complex symptoom, waarvoor op dit moment wereldwijd geen medische oplossing bestaat. Huidige behandelingen richten zich vaak op vermindering van de tinnitushinder. Ook komt tinnitus vaak voor met andere aandoeningen waar gerichte behandelingen voor zijn. Denk aan gehoorverlies (te behandelen met hoortoestellen en/of implantaten) en stemmingsklachten (depressie/angst, te behandelen in overleg met psychiater/psycholoog). De invasiviteit van een behandeling moet worden afgewogen tegen de ernst van de last die een patiënt met tinnitus ondervindt. Tinnitus patiënten die meer tinnitushinder ervaren zullen vaker open staan voor invasievere behandelingen dan patiënten die minder hinder ervaren.

De Goal Attainment Scale (Wagenaar, 2024) laat zien dat patiënten, los van individuele doelen, vijf gemeenschappelijke behandeldoelen hebben:

- Het verkrijgen van controle waardoor er beter met tinnitus kan worden omgegaan

- Het verbeteren van het welzijn en zich minder depressief of angstig voelen

- Het verbeteren van slaap

- Het verminderen van de negatieve effecten van tinnitus op het gehoor

- Het verbeteren van het begrip van tinnitus

Het is voor patiënten van belang dat een behandeling voor tinnitus invloed heeft op een of meerdere van bovenstaande behandeldoelen.

Uitgebreid onderzoek door patiëntenvereniging Tinnitus Hub onder meer dan 5000 patiënten heeft uitgewezen dat patiënten met zogenaamde ‘self administered sound therapy’ (maskering, natuurlijke (achtergrond)geluiden) een aanzienlijke zelf gerapporteerde vermindering van hun tinnituslast hebben ervaren. De kosten van deze afleidingstechnieken zijn laag en de maatregelen zijn eenvoudig toe te passen, ook in aanvulling op andere therapieën. Het is wel van belang dat men zich ervan bewust is dat het gebruik van een maskeerder voor afhankelijkheid van deze maskeerders kan zorgen bij patiënten en daarmee een ongewenst en mogelijk averechts effect op de hinder zou kunnen hebben. Zoals ook benoemd in de module gehoorherstellende therapie kan In geval van mildere vormen van gehoorverlies een hoortoestel een waardevolle behandeling zijn om gehoorverbetering te bewerkstelligen. Ondanks dat de effecitiveit op het verminderen van de tinnitus hinder onbekend is kan door het niet-invasieve karakter van een hoortoestel en de mogelijkheid van een proefperiode deze optie voor de patient van belang zijn om te overwegen en bijdragen aan zelf-regie.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De kosten van tinnitus voor de maatschappij is door Maes (2013) onderzocht. Zij berekenden de medische kosten op € 1544,-- per patiënt per jaar (95%CI € 679-2649,--), en de maatschappelijke kosten op € 5315,-- per patiënt per jaar (95%CI € 1319-9001,--). Mede door het chronische karakter van tinnitusklachten, en door de hoge prevalentie zijn deze kosten substantieel te noemen. De kans is dan ook groot dat interventies die ernstige tinnitusklachten verminderen uiteindelijk ook kosteneffectief zullen zijn. Dat geldt in het bijzonder bij non-invasieve interventies die geen beroep hoeven te doen op de relatief hoge kosten van operatieve medisch-specialistische zorg. Wetenschappelijke studies naar de kosteneffectiviteit zullen echter moeten uitwijzen of de bereikte effecten niet alleen klinisch relevant maar ook de investering waard zijn.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Gezien de ernst van de klachten en de forse impact die tinnitus op het dagelijks leven kan hebben, staan een relatief groot deel van de patiënten open voor diverse typen interventies om hun klachten te verminderen (Tyler, 2012). Tinnitus wordt vaak ervaren als een relatief complex probleem en het gebrek aan eenvoudige behandelingen leidt bij patiënten tot frustratie en soms zelfs tot machteloosheid. Ongeveer 30-40% van de patiënten staat zelfs open voor operatieve, invasieve interventies (Smit, 2018); ook indien ze daarvoor zelf zouden moeten betalen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de geluidsverrijkende therapie

De prevalentie van tinnitusklachten is hoog, met daarbij een forse impact op kwaliteit van leven voor een deel van de patiënten. Op basis van het verrichte literatuuronderzoek blijkt dat voor de onderzochte geluidsverrijkende therapie een grote mate aan onzekerheid bestaat of de tinnitus last verlaagd kan worden in patiënten met chronische subjectieve tinnitus. De werkgroep beveelt aan om meer hoogkwalitatief onderzoek af te wachten naar verschillende (combinaties) van geluidsverrijkende therapieen alvorens deze klinisch toe te passen als standaardbehandeling voor tinnitus.

Let wel; in patiënten met gehoorverlies en bijkomende tinnitus lijkt het wel voor de hand te liggen om een proef met hoortoestellen aan te gaan als gehoorherstellende therapie en mogelijk bijkomend positief effect op de tinnitus.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Momenteel zijn er meerdere behandelingen of combinaties hiervan beschikbaar voor de behandeling van tinnitus. Deze module richt zich op de effectiviteit van geluidsverrijkende therapie bij patiënten met chronische subjectieve tinnitusklachten.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Tinnitus burden (critical)

Tinnitus masking vs. wait list control

|

Low GRADE |

Tinnitus masking may reduce tinnitus burden (measured by THI) when compared with wait list control in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. Source: Henry, 2016 |

Noise generator vs. wait list control

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of noise generator on tinnitus burden (measured by TQ) when compared with wait list control in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. Source: Hobson, 2012 |

Tailor-made notched music training vs. placebo

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of tailor-made notched music training on tinnitus burden (measured by TQ/THQ/VAS) when compared with placebo in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. Source: Stein, 2016 |

Low-level white noise vs. information/relaxation

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of long-term, low-level white noise on tinnitus burden (measured by VAS loudness/VAS annoyance/TRQ) when compared with information/relaxation in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. Source: Hobson, 2012 |

Combination hearing aid vs. hearing aid

|

Low GRADE |

Combination hearing aid may result in little to no difference in tinnitus burden (measured by THI/TFI) when compared with hearing aid in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. Source: Sereda, 2018 |

Sound generator device vs. Hearing aid only

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of sound generator device on tinnitus burden (measured by THI) when compared with hearing aid only in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. Source: Sereda, 2018 |

Quality of life (important)

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of sound enrichment therapy on quality of life when compared with watchful waiting, placebo/sham control, or care as usual in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. Source: - |

Serious adverse events (important)

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of sound enrichment therapy on serious adverse events when compared with watchful waiting, placebo/sham control, or care as usual in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Henry (2016) performed a randomized controlled study to evaluate whether tinnitus masking (TM) (use of ear-level sound generators) or tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) decreased tinnitus severity more than a control group which was either an attention-control group that received tinnitus educational counseling (and hearing aids if needed) (TED) or the 6-month-wait-list control (WLC) group. In total, 148 veterans who experienced sufficiently bothersome tinnitus were randomized into one of the four groups. For this literature analysis, we included the TM group and the WLC group. The TM group consists of 42 patients, the TRT group consists of 34 patients, and the WLC group consists of 33 patients. Of the 34 patients in the TM group, 17 patients reported they always experience difficulty hearing, 9 patients reported they usually experience difficulty hearing, 10 patients reported they sometimes experience difficulty hearing, and 5 patients reported they rarely experience difficulty hearing. Of the 33 patients in the WLC group, 8 patients reported they always experience difficulty hearing, 10 patients reported they usually experience difficulty hearing, 13 patients reported they sometimes experience difficulty hearing, and 1 patient reported rarely experiencing difficulty hearing. The patients were followed-up for 6 months. The study reported the following relevant outcome measure: tinnitus burden.

Hobson (2012) performed a systematic review to assess the effectiveness of sound-creating devices, including hearing aids, in the management of tinnitus in adults. The databases Cochrane ENT Group Trials Register, CENTRAL, PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Web of Science, BIOSIS Previews, Cambridge Scientific Abstracts, ICTRP, and additional sources for published and unpublished trials were searched until 8 February 2012. Prospective randomized controlled trials recruiting adults with persistent, distressing, subjective tinnitus of any aetiology in which the management strategy included maskers, noise-generating device and/or hearing aids, used either as the sole management tool or in combination with other strategies, including counseling were included in the review. In the review, no exclusion criteria were reported. In total, six studies were included in the review, of which two studies were taken into account for this analysis. One study compared outcomes of patients treated by either information plus long-term, low-level white noise or information plus relaxation plus long-term, low-level white noise to controls that received either information only or information plus relaxation (Dineen, 1999). Sound therapy was provided with a device providing stable wide-band noise with as wide a frequency range as possible. The other study compared an intervention group that received noise generators (Viennatone Silent Star) with a control group that received no treatment (Goebel, 1999). The follow-up period was 4 months for one study (Goebel, 1999), and not reported for the other study (Dineen, 1999). Hearing difficulty was not reported by the studies. The following relevant outcome measure was reported: tinnitus burden (measured by VAS loudness and TQ).

Sereda (2018) performed a review to assess the effects of sound therapy, using amplification devices and/or sound generators, for tinnitus in adults. The databases Cochrane ENT Register, Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, ClinicalTrials.gov, ICTRP and additional sources were searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) until 23 July 2018. RCTs recruiting adults with acute or chronic subjective idiopathic tinnitus, where the intervention involved hearing aids, sound generators or combination hearing aids and compared them to waiting list control, placebo or education/information only with no device were included, and studies comparing hearing aids to sound generators, combination hearing aids to hearing aids, and combination hearing aids to sound generators were included too. Studies with a quasi-randomized controlled design were excluded. In total, eight studies were included in the review. Three studies compared a combination device with amplification only (Dos Santos, 2014; Henry, 2015; Henry, 2017), one study compared TRT with sound generator with TRT with amplification only (Parazzini, 2011), two studies compared a sound generator with a placebo device or counselling only (Erlandson, 1987; Stephens, 1985), and two studies compared amplification only with waiting list or relaxation only (Melin, 1987; Zhang, 2013). The follow-up period of the studies varied from 12 weeks to 12 months. All studies recruited patients with hearing loss and/or perceived hearing difficulties. The following relevant outcome measures were reported: tinnitus burden (measured by THI or TFI), and significant adverse events.

Stein (2016) performed a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group randomized controlled trial to assess the effects of tailor-made notched music training (TMNMT) on tinnitus distress. To be eligible for participation, the participants had to meet the following criteria: (i) Chronic, tonal tinnitus with dominant tinnitus frequencies between 1 and 12 kHz, and without hearing loss above 70 dB HL in the frequency ranges of one half octave above and below the tinnitus frequency. In case of bilateral tinnitus, the dominant tinnitus frequency should not differ between ears according to participants’ reports, (ii) aged between 18 and 70 years, (iii) no report of severe chronic or acute mental or neurological disorders which could result in major difficulties maintaining motivational compliance, the ability to follow instructions, or to participate in the training, (iv) no acute ontological diseases, (v) no current consumption of illegal drugs or current consumption of alcohol above the limit recommended by the WHO, (vi) no other current tinnitus therapies or other therapies that might interfere with this trial, and no participation in another clinical trial, (vii) written informed consent to participate in the trial. In total, 100 patients were randomized, but seventeen patients discontinued the intervention, and five patients were lost-to-follow-up. The final sample was composed of 78 patients, of whom 37 patients received TMNMT, and 41 patients received placebo. The treatment lasted for three months, and the follow-up period was one month. The patients in the treatment group suffered from a mean hearing loss of 41.10 dB, and the patients in the placebo group suffered from a mean hearing loss of 44.60 dB. The following relevant outcome measure was reported: tinnitus burden (measured by THQ and VAS).

Results

Tinnitus burden (critical)

Tinnitus masking vs. wait list control

One study reported the outcome measure tinnitus burden measured by THI for tinnitus masking therapy versus wait list control at three and at six months after baseline (Henry, 2016). Patients who received tinnitus masking therapy (n=42) had a mean THI change after three months of treatment of -6.34 (95% CI -10.72 to -1.97), compared to 4.65 (95% CI -0.31 to 9.60) in wait-list control patients (n=33). The mean difference was -10.99 (95% CI -17.60 to -4.38), in favour of tinnitus masking therapy. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Patients who received tinnitus masking therapy (n=42) had a mean THI change after six months of treatment of -9.93 (95% CI -15.23 to -4.62), compared to 3.09 (95% CI -2.91 to 9.10) in wait-list control patients (n=33). The mean difference was -13.02 (95% CI -21.03 to -5.01), in favor of tinnitus masking therapy. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Noise generator vs. wait list control

One study reported the outcome measure tinnitus burden measured by TQ change (Goebel, 1999 from Hobson, 2012). The patients who received noise generation dropped from 56 (SD ± 9) to 55 (SD ± 13), compared with an unchanged score of 54 (SD ± 8) in patients who received no treatment. The difference in TQ change was 1, in favour of the patients who received noise generation. This difference in TQ change is not considered clinically relevant.

Tailor-made notched music training vs. placebo

One study reported the outcome measure tinnitus burden measured by THQ total score and VAS total score with intention-to-treat analysis after three months of tailor-made notched music treatment (Stein, 2016). There were no significant effects for both THQ and VAS.

One study reported the outcome measure tinnitus burden measured by TQ with per protocol analysis after three months of treatment (Stein, 2016). Patients who received TMNMT (n=37) had a mean TQ score after three months of treatment of 22.33 (SD ± 13.96), compared with 22.61 (SD ± 13.02) in patients who received placebo (n=41). The mean difference between the two groups was -0.28 (95% CI -6.29 to 5.73), in favour of patients who received TMNMT. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

One study reported the outcome measure tinnitus burden measured by THQ, VAS and VAS loudness with per protocol analysis after one month of follow-up (one month after cessation of treatment) (Stein, 2016). There were no significant changes for both THQ and VAS between baseline and one month follow-up. Patients who received TMNMT (n=37) had a mean VAS loudness score after one month of follow-up of 45.15 (SD ± 24.45), compared with 48.49 (SD ± 23.86) in patients who received placebo (n=41). The mean difference between the two groups was -3.34 (95% CI -14.08 to 7.40), in favour of patients who received TMNMT. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Low-level white noise vs. information/relaxation

One study reported the outcome measure tinnitus burden measured by the VAS score and the TRQ (Dineen, 1999 from Hobson, 2012). Both the long-term low-level white noise therapy and control groups reported significant decline in tinnitus annoyance and reduction in the reaction to tinnitus at twelve months. There was no significant difference between the TRQ scores at initial assessment and twelve months follow-up for the intervention and the control groups. Relative decreases of 41.5% for VAS loudness, 64.6% for VAS annoyance, and 73.9% for TRQ were reported (Hobson, 2012).

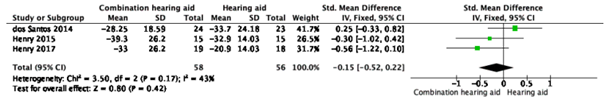

Combination hearing aid vs. hearing aid

One study reported the outcome measure tinnitus burden measured by THI/TFI for combination hearing aid vs. hearing aid only at three to five months (Sereda, 2018). In total, 58 patients who received combination hearing aid and 56 patients who received hearing aid were taken into account. The pooled standardized mean difference between the group of patients who received combination hearing aid and the group of patients who received hearing aid was -0.15 (95% CI -0.52 to 0.22), in favour of the patients who received combination hearing aid. This difference (trivial effect) is not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Tinnitus severity for the comparison combination hearing aid vs. hearing aid (from Sereda, 2018)

Hearing aid only vs. sound generator device

One study reported the outcome measure tinnitus burden measured by change in THI for hearing aid only vs. sound generator device at three, six, and twelve months follow-up (Parazzini, 2011 from Sereda, 2018).

Patients who received hearing aid only (n=49) had a mean THI change at three months of

-18.9 (SD ± 18.4), compared to -20.2 (SD ± 15.8) in sound generator device patients (n=42). The mean difference was 1.30 (95% CI -5.72 to 8.32), in favour of the patients who received sound generator device. This difference is considered not clinically relevant.

Patients who received hearing aid only (n=49) had a mean THI change at six months of -25.6 (SD ± 18.4), compared to -23.8 (SD ± 15.8) in sound generator device patients (n=42). The mean difference was -1.80 (95% CI -8.82 to 5.22), in favour of the patients who received hearing aid only. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Patients who received hearing aid only (n=49) had a mean THI change at twelve months of

-30.1 (SD ± 18.4), compared to -29.2 (SD ± 15.8) in sound generator device patients (n=42). The mean difference was -0.9 (95% CI -7.92 to 6.12), in favour of the patients who received hearing aid only. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Quality of life (important)

None of the included studies reported the outcome measure quality of life.

Serious adverse events (important)

None of the included studies reported the outcome measure serious adverse events.

Level of evidence of the literature

Tinnitus burden (critical)

Tinnitus masking vs. wait list control

The level of evidence for tinnitus burden measured by THI was based on RCTs and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and because the confidence interval exceeds the lower limits of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is therefore graded as low.

Noise generator vs. wait list control

The level of evidence for tinnitus burden measured by TQ was based on RCTs and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1), and because of the very small sample size (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is therefore graded as very low.

Tailor-made notched music training vs. placebo

The level of evidence for tinnitus burden measured by THQ total score, VAS total score and VAS loudness was based on RCTs and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of the very small sample size (imprecision, -2), and because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1). The level of evidence is therefore graded as very low.

Low-level white noise vs. information/relaxation

The level of evidence for tinnitus burden measured by VAS loudness, VAS annoyance, and TRQ was based on RCTs and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1), and because of the very small sample size (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is therefore graded as very low.

Combination hearing aid vs. hearing aid

The level of evidence for tinnitus burden measured by THI and TFI was based on RCTs and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1), and because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1). The level of evidence is therefore graded as low.

Hearing aid only vs. sound generator device

The level of evidence for tinnitus burden measured by THI was based on RCTs and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1), because the confidence interval exceeds the limits of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1), and because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1). The level of evidence is therefore graded as very low.

Quality of life (important)

The level of evidence for quality of life could not be established as no studies reported this outcome measure.

Serious adverse events (important)

The level of evidence for adverse events could not be established as no studies reported this outcome measure.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (un)favorable effects of sound enrichment therapy compared to watchful waiting, placebo/sham control, or care as usual in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus on tinnitus severity, quality of life and serious adverse events?

| P: patients | adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus (≥3 months) |

| I: intervention | sound enrichment therapy |

| C: control | watchful waiting, placebo/sham control, or care as usual |

| O: outcome measure | tinnitus burden, quality of life, serious adverse events. |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered tinnitus burden as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and quality of life and serious adverse events as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Care as usual as defined by the authors (see description of studies);

- Tinnitus burden measured with single- (NRS; numeric rating scale) or multi-item questionnaires (e.g. THI (tinnitus Handicap Inventory), TQ (Tinnitus Questionary), TFI (Tinnitus Functional Index), VAS-(visual analogue score)impact, intrusiveness); Tinnitus burden includes aspects such as impact on daily life, distress and disability (de Ridder, 2021).

- Quality of life in general;

- Serious adverse events.

The working group defined the following differences in outcomes as minimal clinically (patient) important:

- THI: 7 points (Fuller, 2020).

- TFI: 13 (Meikle, 2012)

- TQ: 8 (Zeman, 2012)

- VAS score: 15 points on a 100 scale, 1.5 on a 10 scale (Adamchic, 2021)

- Quality of life: 10%

- NCIQ: 6.36 (Klop, 2008)

- Serious adverse events: 25% (RR < 0.8 or RR > 1.25).

If different measurement instruments were pooled, then differences were defined as: a trivial effect (standardized mean difference (SMD) = 0 to 0.2), a small effect (SMD = 0.2 to 0.5), a moderate effect (SMD = 0.5 to 0.8), and a large effect (SMD >0.8).

Search and select (Methods)

In the original search for the guideline Tinnitus – Behandeling van patiënten met tinnitus (2016), Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 1979 until January 2014. This resulted in 471 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and RCT’s that compared tinnitus treatments with watchful waiting (placebo) in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. In total, 26 studies were included based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, one study was included regarding sound enrichment therapy (Hobson, 2012).

For this update for the guideline Tinnitus – behandeling van patiënten met tinnitus – geluidsverrijkende therapie (2024), the databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 01-01-2014 until 02-05-2022 (SR’s) and 07-07-2022 (RCT’s). The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 363 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and RCT’s that compared sound enrichment therapy with watchful waiting, placebo, or sham control in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. In total, thirteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, ten studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and three studies were included. The study from the original search (Hobson, 2012) was also included for the update. Therefore, two systematic reviews and two randomized controlled trials were taken into account for this update (Henry, 2016; Hobson, 2012; Sereda, 2018; Stein, 2016).

Results

Four studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Adamchic I, Langguth B, Hauptmann C, Tass PA. Psychometric evaluation of visual analog scale for the assessment of chronic tinnitus. Am J Audiol. 2012 Dec;21(2):215-25. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2012/12-0010). Epub 2012 Jul 30. PMID: 22846637.

- Fuller T, Cima R, Langguth B, Mazurek B, Vlaeyen JW, Hoare DJ. Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Jan 8;1(1):CD012614. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012614.pub2. PMID: 31912887; PMCID: PMC6956618.

- Henry JA, Stewart BJ, Griest S, Kaelin C, Zaugg TL, Carlson K. Multisite Randomized Controlled Trial to Compare Two Methods of Tinnitus Intervention to Two Control Conditions. Ear Hear. 2016 Nov/Dec;37(6):e346-e359. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000330. PMID: 27438870.

- Hobson J, Chisholm E, El Refaie A. Sound therapy (masking) in the management of tinnitus in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Nov 14;11(11):CD006371. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006371.pub3. PMID: 23152235; PMCID: PMC7390392.

- Klop WM, Boermans PP, Ferrier MB, van den Hout WB, Stiggelbout AM, Frijns JH. Clinical relevance of quality of life outcome in cochlear implantation in postlingually deafened adults. Otol Neurotol. 2008 Aug;29(5):615-21. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318172cfac. PMID: 18451751.

- Meikle MB, Henry JA, Griest SE, Stewart BJ, Abrams HB, McArdle R, Myers PJ, Newman CW, Sandridge S, Turk DC, Folmer RL, Frederick EJ, House JW, Jacobson GP, Kinney SE, Martin WH, Nagler SM, Reich GE, Searchfield G, Sweetow R, Vernon JA. The tinnitus functional index: development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear Hear. 2012 Mar-Apr;33(2):153-76. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31822f67c0. Erratum in: Ear Hear. 2012 May;33(3):443. PMID: 22156949.

- Sereda M, Xia J, El Refaie A, Hall DA, Hoare DJ. Sound therapy (using amplification devices and/or sound generators) for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Dec 27;12(12):CD013094. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013094.pub2. PMID: 30589445; PMCID: PMC6517157.

- Stein A, Wunderlich R, Lau P, Engell A, Wollbrink A, Shaykevich A, Kuhn JT, Holling H, Rudack C, Pantev C. Clinical trial on tonal tinnitus with tailor-made notched music training. BMC Neurol. 2016 Mar 17;16:38. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0558-7. PMID: 26987755; PMCID: PMC4797223.

- Tinnitus Retraining Therapy Trial Research Group; Scherer RW, Formby C. Effect of Tinnitus Retraining Therapy vs Standard of Care on Tinnitus-Related Quality of Life: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Jul 1;145(7):597-608. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0821. PMID: 31120533; PMCID: PMC6547112.

- Wagenaar O, Gilles A, Van Rompaey V, Blom H. Goal Attainment Scale in tinnitus (GAS-T): treatment goal priorities by chronic tinnitus patients in a real-world setting. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2024 Feb;281(2):693-700. doi: 10.1007/s00405-023-08134-2. Epub 2023 Jul 25. PMID: 37488402.

- Xiang T, Zhong J, Lu T, Pu JM, Liu L, Xiao Y, Lai D. Effect of educational counseling alone on people with tinnitus: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2020 Jan;103(1):44-54. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.07.031. Epub 2019 Jul 27. PMID: 31378310.

- Zeman F, Koller M, Schecklmann M, Langguth B, Landgrebe M; TRI database study group. Tinnitus assessment by means of standardized self-report questionnaires: psychometric properties of the Tinnitus Questionnaire (TQ), the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), and their short versions in an international and multi-lingual sample. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012 Oct 18;10:128. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-128. PMID: 23078754; PMCID: PMC3541124.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Hobson, 2012

Individual study characteristics deduced from Hobson, 2012 |

Systematic review of Randomised Controlled Trials

Literature search up to February 2012

A: Dineen, 1999 B: Goebel, 1999

Study design: A: RCT B: RCT

Source of funding: Not reported.

Conflicts of interest: Not reported. |

Inclusion criteria SR: -Randomised controlled trials, adults in whom there is a complaint of persistent, distressing, subjective tinnitus of any aetiology -Any masking or noise-generating device compared to any other form of tinnitus management -Hearing aids, bone-anchored hearing aids and cochlear implants are ‘noise-generating’ and as such we included them in this study -Patients subjective assessment of tinnitus before, during and after treatment: change in loudness of tinnitus, change in overall severity of tinnitus and/or impact on quality of life

Exclusion criteria SR: A: Not reported. B: Patients with Meniere’s disease, acoustic neuroma, otosclerosis, severe general health problems or psychoses.

2 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N, mean age: A: 96 patients, 54.37 years B: 52 patients, 44 years

Sex: A: 62.5% male B: Not reported.

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Sound therapy

A: Two groups: 1. information plus long-term, low-level white noise 2. information plus relaxation plus long-term, low-level white noise

Sound therapy was provided with custom-made Starkey devices providing stable wide-band noise with as wide a frequency range as possible.

B: Noise generators (Viennatone Silent Star) |

Placebo, sham, or usual care

A: Two groups: 1. information only 2. information plus relaxation

Information consisted of general pathophysiological information on tinnitus as well as information on coping strategies and stress reduction techniques. Relaxation involved a relaxed breathing technique and the use of positive mental imagery.

B: No treatment. |

End-point of follow-up: A: Not reported B: 4 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? A: 13 B: Not reported

|

Tinnitus severity: A: There were relative decreases of 41.5% for VAS loudness, 64.6% for VAS annoyance, 24.6% for VAS coping, 73.9% for TRQ, and 30.8% for change awareness.

B: No significant difference in VAS-score of tinnitus annoyance. I: TQ dropped from 56 ± 9 to 55 ± 13. Not significant. C: TQ remained unchanged (54 ± 8). |

Risk of bias (high, some concerns or low): Tool used by authors: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions A: Some concerns (grade B=medium risk of bias in one parameter) B: HIGH (grade C=medium risk of bias in more than one parameter, or high risk of bias in one parameter)

A: No comparison made between intervention and control group.

|

|

Sereda, 2018

Individual study characteristics deduced from Sereda, 2018

|

SR of RCTs

Literature search up to 23 July 2018

A: Dos Santos, 2014 B: Erlandson, 1987 C: Henry, 2015 D: Henry, 2017 E: Melin, 1987 F: Parazzini, 2011 G: Stephens, 1985 H: Zhang, 2013

Study design: A: RCT (parallel) B: RCT (cross-over) C: RCT (parallel) D: RCT (parallel) E: RCT (parallel) F: RCT (parallel) G: RCT (parallel) H: RCT (parallel)

Setting and Country: A: Department of Otorhinolaryngology, University of Sao Paulo, Brazil B: Department of Audiology, Sahlgrenska Hospital, Göteborg, Sweden C: National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research, Portland (Oregon) Veterans Affairs Medical Center, USA D: National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research at the VA Portland Health Care System, USA E: Swedish University hospital F: Tinnitus clinics (Italy or USA) G: The Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear Hospital, UK H: Tianjin Medical University General Hospital Outpatient Clinic, China

Source of funding: A: Financially supported in the form of Research Grants by the Foundation for Research Support of Sao Paulo State B: Supported by the Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, Delegation for Social Research, the Swedish Council for Planning and Coordination of Research, the National Swedish Board for Technical Development and the Swedish Medical Research Council C: Funded by Starkey Hearing Technologies and by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service D: Not reported E: Supported financially by the Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Foundation and grants from Stiftelsen Tysta Skolan, Stockholm and the Oticon Foundation Copenhagen F: Partially supported by grants from the Tinnitus Research Initiative, by Fondazione Ascolta e Vivi and GN ReSound A/S G: The maskers and combination instruments used, together with some of the test equipment, were provided by a grant from the UK Department for Health and Social Security H: Hearing aids were provided by Disabled Persons’ Federation

Conflicts of interest: A: None reported B: None reported C: Dr. Abrams is employed by Starkey Hearing Technologies, which funded the study, however, the study procedures and data analyses were conducted independent of any company influence D: Not reported E: Not reported F: No conflicts of interest reported G: Not reported H: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria SR: Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) recruiting adults with acute or chronic subjective idiopathic tinnitus. Studies where the intervention involved hearing aids, sound generators or combination hearing aids and compared them to waiting list control, placebo or education/information only with no device were included. Studies comparing hearing aids to sound generators, combination hearing aids to hearing aids, and combination hearing aids to sound generators were included.

Exclusion criteria SR: Quasi-randomized controlled studies were excluded.

8 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, total randomized, completed A: 49, 47 B: 21, 21 C: 30, 30 D: 55, 54 E: 39, 39 F: 101, 91 G: 147, 147 H: 154, 154

Age: A: Between 26 and 91 years old B: 51 years (21-66 years) C: I: 67.9 ± 11 years C: 66.5 ± 7.4 years D: I: 64 years (54-75) C: 61.1 years (48-75) E: I: 73.1 ± 12 years C: 72.2 ± 9.5 years F: 38.8 ± 18.1 years G: <20 n=2, 20-29 n=5, 30-39 n=18, 40-49 n=25, 50-59 n=54, 60-69 n=39, 70-79 n=10 H: 65.5 years (50-79 years)

Sex: A: 25 women and 22 men B: 4 women and 17 men C: I: 5 women and 10 men C: 3 women and 12 men D: I: 4 women and 15 men C: 4 women and 14 men E: I: 13 women and 7 men C: 13 women and 6 men F: I: 19 women and 23 men C: 21 women and 28 men G: 76 women and 77 men H: 71 women and 83 men

Tinnitus duration: A: I: 12.7 years C: 7.6 years B: at least 1 year C: under 1 year to over 20 years D: not reported E: under 1 year to over 5 years F: 69.5 ± 89.7 months G: 3 months to >5 years H: 8.8 years (1 to 28 years)

Tinnitus location (both ears / head / one ear): A: 18 / 15 / 14 B: 4 / 3 / 14 C: not reported D: not reported E: 24 / 5 / 9 F: not reported G: 47% / 8.1% / 45% H: not reported

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Describe intervention:

A: combination device (hearing aids with sound generator) B: sound generator C: combination device (hearing aids with noise generators) + counselling D: combination device (hearing aids with sound generator) + information counselling E: amplification only (hearing aids) F: TRT with amplification only (hearing aids) G: Patients with no hearing disability: intervention group I: A&M sound generator Intervention group II: Viennatone sound generator Patients with hearing disability: Intervention group I: amplification only (hearing aid) Intervention group II: combination device Intervention group III: A&M sound generator H: amplification only (hearing aid) and relaxation

|

Describe control:

A: amplification only (hearing aids) B: placebo device C: amplification only (hearing aids) + counselling D: control group I: amplification only (conventional hearing aids) + information counselling Control group II: amplification only (extended wear hearing aids) + information counselling E: waiting list F: TRT with sound generators G: limited counselling H: relaxation only

|

End-point of follow-up: A: treatment for 3 months, outcomes measured at 3 months B: treatment for 6 weeks, outcomes measured at 6 and 12 weeks C: treatment for 3-4 months, outcomes measured at 3-4 months D: treatment for 4-5 months, outcomes measured at 1 to 3 weeks, 2 months and 4 to 5 months E: not reported F: treatment for 12 months, outcomes measured at 3, 6 and 12 months G: treatment for 6 months, outcomes measured at 6 months H: treatment for 12 months, outcomes measured at 3, 6 and 12 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? A: 2 B: 0 C: 0 D: 1 E: 0 F: 10 G: 0 H: 0

|

Hearing aid only vs. sound generator device Tinnitus burden Defined as tinnitus symptom severity measured by THI

Effect measure: RR, RD, mean difference [95% CI]: F: THI at 3 months I: -18.9 ± 18.4 (n=49) C: -20.2 ± 15.8 (n=42) MD 1.30 (95% CI -5.72 to 8.32), favouring sound generator device

THI at 6 months I: -25.6 ± 18.4 (n=49) C: -23.8 ± 15.8 (n=42) MD -1.80 (95% CI -8.82 to 5.22), favouring hearing aid

THI at 12 months I: -30.1 ± 18.4 (n=49) C: -29.2 ± 15.8 (n=42) MD -0.90 (95% CI -7.92 to 6.12), favouring hearing aid

Significant adverse effect: Increase in self-reported tinnitus loudness

Combination hearing aid vs. hearing aid Tinnitus burden Defined as tinnitus symptom severity measured by THI/TFI

THI/TFI at 3-5 months A: I: -28.2 ± 18.6 (n=24) C: -33.7 ± 24.2 (n=23) SMD 0.25 (95% CI -0.33 to 0.82), favouring hearing aid C: I: -39.3 ± 26.2 (n=15) C: -32.9 ± 14 (n=15) SMD -0.3 (95% CI -1.02 to 0.42), favouring combination hearing aid D: I: -33 ± 26.2 (n=19) C: -20.9 ± 14 (n=18) SMD -0.56 (95% CI -1.22 to 0.1), favouring combination hearing aid

Total SMD -0.15 (95% CI -0.52 to 0.22), favouring combination hearing aid I2= 42.78%

|

Risk of bias (high, some concerns or low): Tool used by authors: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions

A: Unclear (selection, performance) B: High (performance, attrition), Unclear (selection, detection, reporting) C: High (performance, detection), Unclear (selection) D: High (performance), Unclear (detection, other) E: High (performance), Unclear (selection, detection, reporting) F: High (performance), Unclear (selection, detection, attrition) G: High (performance, detection, other), Unclear (selection, attrition) H: High (performance), Unclear (selection, detection)

There is no evidence to support the superiority of sound therapy for tinnitus over waiting list control, placebo or education/information with no device. There is insufficient evidence to support the superiority or inferiority of any of the sound therapy options over each other. The quality of the evidence was low.

Level of evidence: GRADE Hearing aid only vs. sound generator device Tinnitus burden -3 months: Low -6 months: Low -12 months: Low

Combination hearing aid vs. hearing aid Tinnitus burden: Low

Sensitivity analysis (by excluding those studies with high risk of bias) could not be performed because only three studies were included in the meta-analysis.

|

Evidence table for RCTs

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Henry, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: four-site clinical trial, USA.

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding was provided by grants from Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development (RR&D) Service (C2887R and C3214R), with general support from the Veterans Health Administration.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. |

Inclusion criteria: Veterans who experienced sufficiently bothersome tinnitus. Patients were screened with the tinnitus-impact screening interview which includes 8 questions.

Exclusion criteria: Not described.

N total at baseline: Intervention TM: 42 Intervention Control: 33

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I TM: 62.4 (9.8) C: 61.2 (8.8)

Sex: I TM: 95.2% M C: 97.0% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Subjects in the four groups did not differ significantly on the baseline demographic or clinical characteristics listed in Table 2 |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Tinnitus masking (TM)

Subjects receiving TM were fitted with ear-level sound generators (aka “maskers”), hearing aids, or combination instruments. The fitting protocol for these subjects was mostly the same as in the preceding study.

TM subjects in the present study were fitted with ear-level “maskers” if they had normal hearing or if their hearing loss was mild enough that they would not be considered hearing aid candidates under normal circumstances. If amplification was appropriate based on level of hearing loss, then TM subjects could choose either hearing aids or combination instruments, whichever they preferred to receive sound-based relief.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

6-month-wait-list control (WLC) group.

For the WLC group, we considered extending the duration of no treatment beyond 6 months. This was decided against, however, because it would force Veterans to wait at least 1 year for treatment. In our previous study (Henry et al. 2006b), significant benefit was observed within 3 months for both treatment groups, with even greater improvement at 6 months. Six months of no treatment would therefore be sufficient to control for the treatment variable. WLC subjects completed outcome assessments at 0, 3, and 6 months, ensuring three equally spaced data collection points during the no-treatment period. At 6 months, these subjects were informed of their treatment-group assignment—as determined at baseline—and started treatment. |

Length of follow-up: The total follow-up of the study was 18 months. However as the wait-list-control was only 6 months, we used only 6 months of follow-up in this literature review.

Loss-to-follow-up at 6 months Intervention TM: 9 Control: 1 Reasons (describe): not described.

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention TM: 1 Control: 0 Reason: skipped visit, missing 6 months outcomes.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

THI at 3 months TM: -6.34 (-10.72 to -1.97) WLC: 4.65 (-0.31 to 9.60)

THI at 6 months: TM: -9.93 (-15.23 to -4.62) WLC: 3.09 (-2.91 to 9.10).

THI at 3 months (mean difference, 95%CI) TM versus WLC: -10. 99 (-17.60 to -4.38)

THI at 6 months TM versus WLC: -13.02 (-21.03 to -5.01)

Quality of life Not reported.

Adverse events Not reported.

|

Authors’ conclusion: Audiologists who provided interventions to Veterans with bothersome tinnitus in the regular clinic setting were able to significantly reduce tinnitus severity over 18 months using TM, TRT, and TED approaches. These results suggest that TM, TRT, and TED, when implemented as in this trial, will provide effectiveness that is relatively similar by 6 months and beyond. |

|

Stein, 2016 |

Type of study: randomized controlled trial (double-blinded parallel group design)

Setting and country: Institute for Biomagnetism and BioSignal analysis of the University of Muenster, Germany

Source of funding: The clinical trial was funded by the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research of the Medical Faculty of the University of Münster, Germany.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. |

Inclusion criteria: -Chronic, tonal tinnitus with dominant tinnitus frequencies between 1 and 12 kHz, and without hearing loss above 70 dB HL in the frequency ranges of one half octave above and below the tinnitus frequency. In case of bilateral tinnitus, the dominant tinnitus frequency should not differ between ears according to participants’ reports. -Aged between 18 and 70 years. -No report of severe chronic or acute mental or neurological disorders which could result in major difficulties maintaining motivational compliance, the ability to follow instructions, or to participate in the training. -No acute ontological diseases. -No current consumption of illegal drugs or current consumption of alcohol above the limit recommended by the WHO. -No other current tinnitus therapies or other therapies that might interfere with this trial, and no participation in another clinical trial. -Written informed consent to participate in the trial.

Exclusion criteria: See inclusion criteria.

N total at baseline: I: 50 C: 50 Analyzed: I: n=37 C: n=41

Important prognostic factors at baseline: Age ± SD: I: 47.68 ± 9.94 C: 47.13 ± 11.70

Sex (male/female): I: 33/17 C: 34/16

Time since tinnitus onset (years): I: 7.03 ± 7.25 C: 8.95 ± 6.80

THI baseline I: 24.10 ± 14.96 C: 26.96 ± 16.92

TQ baseline I: 19.12 ± 10.62 C: 25.28 ± 13.82

VAS annoyance baseline: I: 39.70 ± 26.18 C: 40.32 ± 22.27

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Tailor-made notched music training (TMNMT). Participants received a mobile device with their favourite music. The music was modified identically for both ears. The frequency band centered at the individual tinnitus frequency of each participant was removed from the music energy spectrum, aiming to increase the lateral inhibition effect within the notch area corresponding to the tinnitus frequency.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Placebo. A moving notch filter with the same bandwidth as in the target condition was applied. The moving filter selected a frequency band. After 5s of filtering, the center frequency of the filter randomly jumped either 1/18 octave up or down and continued jumping in the same direction every 5s until its lower or higher edge reached a predefined border at which point it changed direction. |

Length of follow-up: 3 months treatment and 1 month follow-up.

Loss-to-follow-up: I: n=13 Reasons: -Discontinued intervention (n=10) -Lost to follow-up (n=3)

C: n=9 Reasons: -Discontinued intervention (n=7) -Lost to follow-up (n=2)

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Intention-to-treat No significant effects THQ total score baseline: I: 24.95 ± 16.91 C: 28.51 ± 16.41

Pre vs post (treatment vs placebo): Df 90.77 t-statistic: -1.127

VAS total score baseline: I: 42.83 ± 21.71 C: 44.71 ± 19.28

Pre vs post (treatment vs placebo): Df 88.85 t-statistic: 0.280

Per protocol - post Significant effect for TQ Placebo Pre: M TQ score = 23.56 ± 13.56 Post: M TQ score = 22.61 ± 13.02

Treatment Pre: M TQ score = 19.85 ± 10.75 Post: M TQ score = 22.33 ± 13.96

Per protocol – follow-up No significant effect for THQ and VAS total score

Significant effect for VAS loudness Treatment Pre: M VAS loudness = 53.46 ± 21.74 Post: M VAS loudness = 47.24 ± 23.80 Follow-up: M VAS loudness = 45.14 ± 24.45

Placebo Pre: M VAS loudness = 46.15 ± 21.89 Post: M VAS loudness = 47.00 ± 24.16 Follow-up: M VAS loudness = 48.49 ± 23.86

|

Effects differed between the placebo and the target group for the TQ only. The placebo group showed even lower scores in the TQ after the training when compared to the treatment group. |

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Henry, 2016 |

No information;

Reason: Qualifying subjects received an envelope containing their assignment (TRT, TM, TED, and WLC). |

No information;

Reason: Qualifying subjects received an envelope containing their assignment (TRT, TM, TED, and WLC). |

Definitely no;

Reason: study participants and personnel was not blinded. |

Definitely no;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was more than 10% in the intervention groups. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely no;

Reason: the study size was too small. |

HIGH (THI)

Reason: The primary outcome measure (THI) is subjective, as the study is not blinded this could result in bias. |

|

Stein, 2016 |

Probably yes

Reason: Stratified randomization. Within each stratum, a blocked randomization (block size = 4) was performed using a computer generated randomization list. |

Definitely yes

Reason: The allocation of a participant to the target or the placebo group was realized within an App through the application of appropriate settings. Afterwards, the App was password-locked to disable further changes and reading of the settings. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Double-blind. Participants and investigators remained blind to the allocation. |

Definitely no

Reason: Loss to follow-up was more than 10% in both the intervention and the control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcome measures were reported. |

Probably no

Reason: Tinnitus related distress was generally low, possibly because of the exclusion of participants with mental disorders such as depression. The psychometric quality of the outcome measures. |

Some concerns

Reason: High loss to follow-up, generally low tinnitus related distress and questionable psychometric quality of the outcome measures. |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Chen J, Zhong P, Meng Z, Pan F, Qi L, He T, Lu J, He P, Zheng Y. Investigation on chronic tinnitus efficacy of combination of non-repetitive preferred music and educational counseling: a preliminary study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021 Aug;278(8):2745-2752. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06340-w. Epub 2020 Sep 5. PMID: 32892305. |

No randomized controlled trial. |

|

Deshpande AK, Bhatt I, Rojanaworarit C. Virtual reality for tinnitus management: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Audiol. 2022 Oct;61(10):868-875. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2021.1978568. Epub 2021 Sep 22. PMID: 34550862. |

Different comparison: sound therapy versus sound therapy with virtual reality. |

|

Li F, Zhang Y, Jiang X, Chen T. Effects of different personalised sound therapies in tinnitus patients with hearing loss of various extents. Int J Clin Pract. 2021 Dec;75(12):e14893. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14893. Epub 2021 Sep 27. PMID: 34541744. |

No randomized controlled trial. |

|

Li SA, Bao L, Chrostowski M. Investigating the Effects of a Personalized, Spectrally Altered Music-Based Sound Therapy on Treating Tinnitus: A Blinded, Randomized Controlled Trial. Audiol Neurootol. 2016;21(5):296-304. doi: 10.1159/000450745. Epub 2016 Nov 12. PMID: 27838685. |

Different comparison: altered versus unaltered music. |

|

Li Y, Feng G, Wu H, Gao Z. Clinical trial on tinnitus patients with normal to mild hearing loss: broad band noise and mixed pure tones sound therapy. Acta Otolaryngol. 2019 Mar;139(3):284-293. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2019.1575522. Epub 2019 Feb 26. PMID: 30806130. |

Different comparison: sound therapy effects of the broad band noise versus mixed pure tones. |

|

Mahboubi H, Haidar YM, Kiumehr S, Ziai K, Djalilian HR. Customized Versus Noncustomized Sound Therapy for Treatment of Tinnitus: A Randomized Crossover Clinical Trial. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2017 Oct;126(10):681-687. doi: 10.1177/0003489417725093. Epub 2017 Aug 23. PMID: 28831839. |

Different comparison: customized sound therapy versus masking with broadband noise. |

|

Theodoroff SM, McMillan GP, Zaugg TL, Cheslock M, Roberts C, Henry JA. Randomized Controlled Trial of a Novel Device for Tinnitus Sound Therapy During Sleep. Am J Audiol. 2017 Dec 12;26(4):543-554. doi: 10.1044/2017_AJA-17-0022. PMID: 29090311. |

Different comparison: three sound enrichment therapies are compared to one another. |

|

Therdphaothai J, Atipas S, Suvansit K, Prakairungthong S, Thongyai K, Limviriyakul S. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Notched Music Therapy for Tinnitus Patients. J Int Adv Otol. 2021 May;17(3):221-227. doi: 10.5152/iao.2021.9385. PMID: 34100746; PMCID: PMC9450089. |

Different comparison: tailor-made notched music versus ordinary music. |

|

Tyler RS, Stocking C, Ji H, Witt S, Mancini PC. Tinnitus Activities Treatment with Total and Partial Masking. J Am Acad Audiol. 2021 Sep;32(8):501-509. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1731698. Epub 2021 Dec 29. PMID: 34965596. |

Different comparison: treatment in patients with and without hearing aids. |

|

Wei, Wong & Wan Mohamad, Wan Najibah & wan husain, wan suhailah & Zakaria, Mohd. (2020). The tinnitus suppressive effect: Comparisons between three types of maskers. International Journal on Disability and Human Development. 19. 21-26. |

No randomized controlled trial. |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 19-11-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire cluster ingesteld. Dit cluster bestaat uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante organisaties die betrekking hebben op de zorg voor patiënten met gehoorproblemen.

Het cluster Otologie bestaat uit meerdere richtlijnen, zie hier voor de actuele clusterindeling. De stuurgroep bewaakt het proces van modulair onderhoud binnen het cluster. De expertisegroepsleden worden indien nodig gevraagd om hun expertise in te zetten voor een specifieke richtlijnmodule. Het cluster Otologie bestaat uit de volgende personen:

Clusterstuurgroep

- Dr. H. (Hilke) van Det-Bartels, voorzitter cluster otologie, KNO-arts, Isala, Zwolle, NVKNO (tot en met oktober 2023)

- Drs. M. (Monique) Campman-Verhoeff, voorzitter cluster otologie, KNO-arts, Treant Zorggroep, Emmen (vanaf november 2023)

- Dr. E. (Erik) van Spronsen, voorzitter cluster otologie, KNO-arts, Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, Amsterdam

- Drs. R.M. (Robert) van Haastert, KNO-arts, Dijklander Ziekenhuis, Purmerend

- Dr. A.L. (Diane) Smit, KNO-arts, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht

- Drs. M.J. (Thijs) Vaessen, Oogarts, Deventer Ziekenhuis, Deventer

- Dr. Y.J.W. (Yvonne) Simis, Klinisch fysicus, audioloog, Amsterdam UMC locatie VUmc, Amsterdam (tot augustus 2023)

- Dr. ir. F.L. (Femke) Theelen, Audioloog, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam (vanaf augustus 2023)

- Drs. S.A.H. (Sjoert) Pegge, Radioloog, Radboudumc, Nijmegen

Betrokken clusterexpertisegroep

- Dr. A.L. (Diane) Smit, KNO-arts, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht

- Dr. R. (Rutger) Hofman, KNO-arts, UMCG, Groningen

- Dr. C.A. (Katja) Hellingman, KNO-arts, Maastricht UMC, Maastricht

- Dr. E.L.J. (Erwin) George, Klinisch fysicus-audioloog, Maastricht UMC, Maastricht

- M. (Michael) Huinink, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Stichting Hoormij·NVVS (tot en met mei 2023)

- Drs. O.V.G. (Olav) Wagenaar, klinisch neuropsycholoog, Rijndam revalidatie (vanaf januari 2024)

- Ir. C.W.M. (Chris) van den Dries, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Stichting Hoormij·NVVS (vanaf februari 2024)

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. R. (Romy) Zwarts-van de Putte, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. E.R.L. (Evie) Verweg, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle clusterstuurgroepleden en actief betrokken expertisegroepleden (fungerend als schrijver en/of meelezer bij tenminste één van de geprioriteerde richtlijnmodules) hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een richtlijnmodule worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de projectleider doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase. Een overzicht van de belangen van de clusterleden en betrokken expertisegroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Clusterstuurgroep

Tabel 1. Gemelde (neven)functies en belangen stuurgroep

|

Clusterlid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Van Det |

KNO arts Isala Zwolle |

Voorzitter koploperproject, lid kerngroep otologie KNO vereniging, lid klankbordgroep vestibulologie, lid KNO vereniging |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Spronsen |

KNO-arts, Amsterdam UMC |

Raad van Advies START |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Vaessen |

Oogarts Deventer Ziekenhuis, Oogarts Streekziekenhuis Koningin Beatrix te Winterswijk |

Geen |

Samen met Sallandse Specialisten Coorporatie aandeelhouder in een drietal |

Geen restrictie |

|

Simis (tot augustus 2023) |

Klinisch Fysicus – Audioloog |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Van Haastert |

KNO-arts Dijklanderziekenhuis Hoorn/Purmerend |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Smit |

KNO arts UMC Utrecht, afdeling KNO |

Medisch adviseur Stichting Hoormij·NVVS, onbetaald |

-Medeaanvrager en onderzoeker van MinT-studie over toepassing van mindfulness bij tinnitus, gefinancierd door HandicapNL |

Geen restrictie, de studie die betrekking heeft op tinnitus is niet gefinancierd door een commerciële partij. |

|

Campman-Verhoeff |

KNO-arts Treant Zorggroep |

Bestuurslid stichting nascholing KNO – onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Pegge |

Radioloog Radboud UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Theelen (vanaf augustus 2023) |

Klinisch Fysicus – Audioloog |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

Clusterexpertisegroep

Tabel 2. Gemelde (neven)functies en belangen expertisegroep

|

Clusterlid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Hofman |

KNO-arts UMCG, Groningen |

Geen |

Copromotor van een promovendus die onderzoek doet naar beengeleidingsimplantaten (BCD), onderzoek is gesponsord door Oticon medical. Een BCD helpt niet tegen tinnitus. |

Geen restrictie, geen connectie tussen extern gefinancierd onderzoek en herziene modules. |

|

Hellingman |

KNO-arts/otoloog MUMC+, Maastricht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

George |

Klinisch fysicus-audioloog, Maastricht UMC+ |

- bestuurslid Stichting Opleiding Klinische Fysica (onbetaald) |

ELEPHANT-studie (2018-2022) en RHINO-studie (vanaf 2022), wetenschappelijke research; promovendus grotendeels gefinancieerd door Advanced Bionics, op gebied van optimalisatie van outcomes van cochleaire implantatie. Geen vergoeding voor mijzelf. -Reguliere samenwerking met patientenorganisatie Stichting Hoormij·NVVS, geen boegbeeldfunctie. |

Geen restrictie. Deze studies hebben geen betrekking op de modules die in deze cyclus zijn herzien. |

|

Huinink (tot mei 2023) |

Directeur Grootzakelijk Rabobank Vrijwilliger Stichting Hoormij·NVVS |

Bestuurslid (toezichthouder) Stichting NMCX |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Wagenaar (vanaf januari 2024) |

Klinisch neuropsycholoog/opleider bij Revalidatiecentrum Rijndam |

'Tinnitus (onbetaald) Columnist Earline (betaald) |

Royalty’s boek EHBOorsuizen Royalty’s online zelf-CGT eHBOorsuizen Financieel belang in TinniVRee Neuropsychologisch verklaringsmodel tinnitus & hyperacusis. EHBOorsuizen FB peersupportgroup |

Geen restrictie, de mogelijke belangen hebben geen betrekking op de modules die in deze cyclus zijn herzien. |

|

Van den Dries (vanaf februari 2024) |

Vrijwilliger bij Stichting Hoormij·NVVS Lid van Commissie Tinnitus en Hyperacusis als belangenbehartiger en voorlichter |

Moderator van de Facebookgroep Eerste Hulp bij Oorsuizen/Tinnitus |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door deelname van relevante patiëntenorganisaties aan de need-for-update en/of prioritering. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijnmodule is tevens ter commentaar voorgelegd aan alle relevante patiëntenorganisaties in de stuur- en expertisegroep (zie ‘Samenstelling cluster’ onder ‘Verantwoording’) en aan alle patiëntenorganisaties die niet deelnemen aan de stuur- en expertisegroep, maar wel hebben deelgenomen aan de need-for-update (zie ‘Need-for-update’ onder ‘Verantwoording’). De eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Bij de richtlijnmodule is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd om te beoordelen of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module [Behandeling van patiënten met tinnitus – geluidsverrijkende therapie] |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 3.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Need-for-update, prioritering en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de need-for-update fase (voorjaar, 2021) inventariseerde het cluster de geldigheid van de richtlijnmodules binnen het cluster. Naast de partijen die deelnemen aan de stuur- en expertisegroep zijn hier ook andere stakeholders voor benaderd. Per richtlijnmodule is aangegeven of deze geldig is, herzien moet worden, kan vervallen of moet worden samengevoegd. Ook was er de mogelijkheid om nieuwe onderwerpen aan te dragen die aansluiten bij één (of meerdere) richtlijn(en) behorend tot het cluster. De richtlijnmodules waarbij door één of meerdere partijen werd aangegeven herzien te worden, werden doorgezet naar de prioriteringsronde. Ook suggesties voor nieuwe richtlijnmodules werden doorgezet naar de prioriteringsronde. Afgevaardigden vanuit de partijen in de stuur- en expertisegroep werden gevraagd om te prioriteren (zie ‘Samenstelling cluster’ onder ‘Verantwoording’). Hiervoor werd de RE-weighted Priority-Setting (REPS) – tool gebruikt. De uitkomsten (ranglijst) werd gebruikt als uitgangspunt voor de discussie. Voor de geprioriteerde richtlijnmodules zijn door de het cluster concept-uitgangsvragen herzien of opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde het cluster welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. Het cluster waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde het cluster tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd indien mogelijk gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding). GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

Tabel 3. Gradaties voor de kwaliteit van wetenschappelijk bewijs

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in een richtlijnmodule volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door het cluster wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. Het cluster heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

Tabel 4. Sterkte van de aanbevelingen

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

Bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de richtlijnmodule Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd voorgelegd aan alle partijen die benaderd zijn voor de need-for-update fase. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met het cluster. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door het cluster. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd ter autorisatie of goedkeuring voorgelegd aan de partijen die beschreven staan bij ‘Initiatief en autorisatie’ onder ‘Verantwoording’.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.