Psychologische interventies – CGT gericht op tinnitusklachten

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van cognitieve gedragstherapie (CGT) bij patiënten met chronische subjectieve tinnitusklachten?

Aanbeveling

Verricht cognitieve gedragstherapie bij patienten met tinitusklachten en lijdensdruk wanneer:

- Uit anamnese en klachtenpresentatie naar voren komt dat de patiënt met chronische subjectieve tinnitusklachten behoefte heeft aan behandeling; en

- Matige tot ernstige lijdensdruk en negatieve impact van tinnitus op het functioneren is geobjectiveerd; en

- De lijdensdruk aanhoudt, ondanks uitgebreide psychoeducatie.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar het effect van CGT ten opzichte van een afwachtend beleid, placebo of standaard zorg bij volwassen patiënten met chronische subjectieve tinnitusklachten (minimaal drie maanden). Hierin is gezocht naar CGT behandeling bij patienten met tinnitusklachten zonder nadere specificering van de inhoud van de protocollen. Uit de search kwam één systematische review en twee RCTs die CGT vergeleken met een wachtlijst controle en één systematische review en twee RCTs die CGT vergeleken met standaard zorg. De definitie van standaard zorg wordt niet verder beschreven in de literatuur.

CGT versus wachtlijst controle

Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat tinnituslast werd een klinisch relevant verschil gevonden in het voordeel van patiënten die CGT ontvingen. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat kwaliteit van leven werd geen klinisch relevant verschil gevonden. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat ernstige bijwerkingen werd geen verschil tussen de groepen gevonden. Zowel CGT als afwachtend beleid geven dus geen ernstige bijwerkingen bij volwassen patiënten met chronische subjectieve tinnitusklachten.

CGT versus standaard zorg

Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat tinnituslast en voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat kwaliteit van leven werden geen klinisch relevante verschillen gevonden. De belangrijke uitkomstmaat ernstige bijwerkingen werd niet gerapporteerd in de geïncludeerde studies voor de vergelijking CGT versus standaard zorg.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Omdat voor tinnitus op dit moment geen medische oplossing bestaat, is gangbare behandeling gericht op vermindering van de hinder door tinnitus. De invasiviteit van een behandeling moet worden afgewogen tegen de ernst van de last die een patiënt met tinnitus ondervindt.

De totale tinnitus populatie is sterk heterogeen waarbij een grote groep weinig tot geen lijdensdruk ervaart, een middengroep hinder ervaart maar zich kan handhaven en een kleine groep zoveel lijdensdruk ervaart dat sprake is van een tinnitusstoornis. De behoefte van de individuele patiënt in combinatie met diens psychische lijdensdruk moet de therapeutische aanpak bepalen. Het is dan ook van belang om eerst de mate van psychisch lijden klinimetrisch in kaart te brengen om te beoordelen of een psychologische behandeling geïndiceerd is. Vervolgens zal de keuze voor een CGT gericht op tinnitusklachten of een ander behandeltraject vooral afhangen van de mate van psychische klachten met gedragsmatig in standhoudende factoren. Matige of afwezige lijdensdruk heeft immers een zeer negatieve impact op de therapietrouw, terwijl CGT gericht op tinnitusklachten veel inzet en motivatie van de patiënt eist, ook in diens thuissituatie (Lebeau, 2013).

Het wordt dus nadrukkelijk niét aanbevolen om iedere patiënt standaard CGT gericht op tinnitusklachten aan te bieden, maar slechts op voorwaarde van indicatie die in het psychologische domein ligt.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

CGT gericht op tinnitusklachten is een kostbare therapie die veel middelen vergt en waarvan de uitvoer ligt in de handen van gekwalificeerde therapeut. Bovendien zijn gekwalificeerde zorgverleners schaars en kan de huidige wachttijd in gespecialiseerde behandelcentra vele maanden bedragen waarbij de lijdensdruk gedurende de wachttijd tot psychiatrische ernst kan ontwikkelen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

CGT is een reguliere therapie, opgenomen in het zorgverzekeringspakket (NB: mogelijk wel aanvullend pakket noodzakelijk gezien het gemiddeld aantal sessies). Desalniettemin verlangt CGT gericht op tinnitusklachten wel aanvullende expertise van de therapeut. Hierin schuilt een dilemma: bij verwijzing naar de GGZ waar CGT ruim beschikbaar is, ontbreekt veelal de kennis van tinnitus en ervaring met tinnitus patiënten. De CGT voor tinnitus patiënten zal dan ook idealiter in tinnitus specialistische centra plaatsvinden, die echter schaars zijn en waar psychotherapeutische en psychiatrische deskundigheid niet altijd voorhanden is terwijl het juist de mate van psychische lijdensdruk is die de indicatie vormt voor de behandeling. Het is van belang dat bij de bepaling van lijdensdruk en de indicatiestelling voor CGT gericht op tinnitusklachten gebruik wordt gemaakt van gestandaardiseerde vragenlijsten, zoals bijvoorbeeld HADS, BSI, TFI, THI of, TQ (zie module vragenlijsten bij diagnose tinnitus).

Problemen die hieruit voortvloeien zijn enerzijds dat de wachttijden voor behandeling in expertisecentra lang kunnen zijn of dat de behandeling niet in de nabijheid van de patiënt gelegen is (met socio-economische implicaties voor de patiënt) en anderzijds dat patiënten met tinnitusklachten vanwege de ernst van hun psychische problemen vaak voldoen aan exclusiecriteria voor behandeling in een niet-GGZ instelling. De haalbaarheid van CGT gericht op tinnitusklachten op de juiste plek is dus het minst geborgd voor de groep die het meest urgent psychologische behandeling nodig heeft. Daarnaast vereist CGT gericht op tinnitusklachten bepaalde vaardigheden van de patiënt die beperkt kunnen zijn. Dit suggereert dat er een subgroep patiënten bestaat die niet in aanmerking kan komen voor CGT gericht op tinnitusklachten en dat er een gezondheidsongelijkheid bestaat. Een GGZ-instelling met bewezen kennis van en ervaring met tinnitus(patiënten) is wellicht de meest geschikte zorgverlenende partner voor de toepassing van psychologische therapieën. Niet-GGZ instellingen (zoals audiologische centra) zouden in ieder geval specialistische psychologische en psychiatrische consultatiemogelijkheden moeten borgen om een vorm van psychotherapeutisch aanbod te kunnen aanbieden voor tinnitus patiënten.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

CGT is een effectieve interventie, ook tegen tinnitus gerelateerde hinder, maar verlangt een specifieke indicatiestelling op basis van de ernst van psychische lijdensdruk en intrapersoonlijke kenmerken en vaardigheden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Currently, multiple treatments or combinations of treatments are available for the treatment of tinnitus. This submodule focuses on the effectiveness of the psychological intervention CBT in patients with chronic subjective tinnitus complaints.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

CBT vs. watchful waiting

Tinnitus burden

|

Moderate GRADE |

CBT likely reduces tinnitus burden when compared with watchful waiting in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. Source: Beukes, 2022, Fuller, 2020; Walter, 2023 |

Quality of life

|

Low GRADE |

CBT may result in little to no difference in quality of life when compared with watchful waiting in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. Source: Beukes, 2022; Fuller, 2020 |

Serious adverse events

|

Moderate GRADE |

CBT likely results in little to no difference in serious adverse events when compared with watchful waiting in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. Source: Beukes, 2022; Fuller, 2020; Walter, 2023 |

CBT vs. usual care

Tinnitus burden

|

Low GRADE |

CBT may result in little to no difference in tinnitus burden when compared with usual care in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. Source: Cima, 2018; Fuller, 2020; Kröner-Hedwig, 2003 |

Quality of life

|

Moderate GRADE |

CBT likely results in little to no difference in quality of life when compared with usual care in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. Source: Cima, 2018 |

Serious adverse events

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of CBT on serious adverse events when compared with usual care in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

CBT vs. watchful waiting

Fuller (2020) performed a systematic review to assess the effects and safety of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for tinnitus in adults. On 25 November 2019, the ENT Trials Register, CENTRAL, Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, ClinicalTrials.gov, ICTRP and additional sources for published and unpublished trials were searched to retrieve relevant publications. Randomized controlled trials (RCT’s) comparing CBT versus no intervention, audiological care, tinnitus retraining therapy, or any other active treatment in adult patients with tinnitus were included. In this analysis, we included nine RCT’s that compared CBT with waiting list control, or care as usual. A meta-analysis was performed for the outcome measure tinnitus severity at the end of treatment. The following relevant outcome measures were reported: tinnitus burden, quality of life, and adverse effects.

Walter (2023) performed a randomized interventional clinical study trial to investigate the clinical efficacy of the smartphone-based cognitive behavioral therapy in patients with chronic tinnitus that either received the app or waited for this period before receiving the app. Patients who were eighteen years of age and older, with chronic subjective tinnitus of more than three months duration were eligible for trial inclusion. Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of acute or chronic mental illness. In total, 187 patients were randomized to the intervention or control group. The intervention group (n=94) received cognitive behavioral therapy through the Kalmeda Tinnitus app. The app consisted of five levels with nine steps each. Level one and two, focusing on behavioral therapy (redirecting attention and relaxation) are typically completed in three months. The control group (n=93) waited for three months, while the patients in the intervention group used the CBT app. The follow-up duration was three months. The study reported the following relevant outcome measures: tinnitus burden and adverse events.

Beukes (2022) performed a prospective two-arm delayed intervention efficacy trial to explore the effects of internet-based CBT in the United States by evaluating the efficacy of audiologist-delivered internet-based CBT in reducing tinnitus distress compared with that in weekly monitoring of tinnitus. Patients aged eighteen years or older, living in Texas, United States, with the ability to read and type in English or Spanish, who have access to a computer and the internet and were able to email, who experienced tinnitus for a minimum period of three months, with a tinnitus severity score of at least 25 on the Tinnitus Functional Index (indicating the need for an intervention). Exclusion criteria were indications of significant depression on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, indications of self-harm thoughts or intent (affirmative answer to question ten of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9), reporting any medical or psychiatric conditions that could interfere with the treatment, reporting pulsatile, objective, or unilateral tinnitus, which has not been investigated medically or tinnitus is still under medical investigation, and undergoing any tinnitus therapy concurrent with participation in the study. In total, 158 patients were randomly assigned to the intervention and control group. The intervention group (n=79) received an internet-based CBT intervention based on a self-help program, transformed into an eight-week interactive e-learning. The control group (n=79) received no intervention during the first eight weeks but were weekly monitored. After eight weeks, the patients in the control group received the same intervention as the intervention group. The follow-up duration was eight weeks. The study reported the following relevant outcome measures: tinnitus burden , and adverse effects.

CBT vs. usual care

Cima (2018) performed a single-centre RCT to compare a specialized cognitive behavioral stepped care with usual care in adult tinnitus patients. Patients who reported tinnitus complaints, aged 18 years and older were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were being unable to read and write in Dutch, medical conditions preventing patients to participate and patients visiting the center within five years prior to trial enrolment. In total, 492 patients were included, of whom 245 were allocated to the intervention and 247 were allocated to the control (usual care). The intervention consisted of comprehensive multidisciplinary audiological and psychological diagnostics and ‘specialized CBT for Tinnitus’, consisting of stepped care starting with counselling elements with the use of a neuro-physiological model, within a CBT framework. Step two (for patients with more severe tinnitus) treatment consisted of three different 12-week group-treatment options. The control group received usual care, consisting of a standardized protocol usually provided by secondary care audiological centers with step one being a standard audiological intervention. Treatment ended after step one for patients with mild complaints. Step two (for patients with more severe tinnitus) consisted of counselling sessions with a social worker focused on coping strategies, work-related problems and daily structuring for twelve weeks maximally. There were three follow-up assessments up to twelve months after randomization. The study reported the following relevant outcome measures: tinnitus severity, tinnitus related impairments and quality of life.

Kröner-Hedwig (2003) performed a randomized control group study to compare the efficacy of Tinnitus Coping Training (TCT) with two minimal contact (MC) interventions and a waiting-list control group. Patients who were between eighteen and 65 years old, with a duration of tinnitus that exceeded six months and with a medical diagnosis of idiopathic tinnitus as their main health problem, whose subjective annoyance by tinnitus reached an average rating of at least 40 on nine scales assessing disruptive effects of tinnitus were eligible for trial participation. Exclusion criteria were hearing loss preventing patients from participating in communication within groups and currently being in psychotherapeutic treatment. In total, 106 patients were randomized to the intervention and control groups. For this analysis, the TCT and waitlist group will be taken into account. The intervention group (n=56) received Tinnitus Coping Training which consisted of 11 sessions with a 90–120-minute duration focusing, amongst others, on education, relaxation, attention and distraction, dysfunctional and functional thoughts, and problem solving. The patients in the control group (n=20) received no intervention but were placed on a waiting list. The follow-up duration was 12 months for the TCT group. The study reported the following relevant outcome measure: tinnitus burden.

Results

CBT vs. watchful waiting

Tinnitus burden (TFI, TQ, THI, TRQ, TEQ)

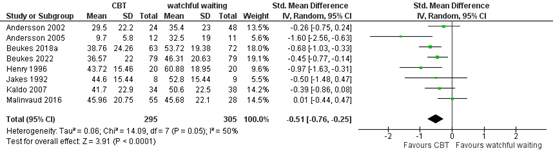

One systematic review (Fuller, 2020) and one study (Beukes, 2022) reported the outcome measure tinnitus burden, measured by TFI, TQ, THI, TRQ or TEQ. In total, 295 patients received CBT and 305 patients received watchful waiting. The standardized mean difference was -0.51 (95% CI -0.76 to -0.25), in favour of the patients who received CBT. This difference is considered to be a moderate effect. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Meta-analysis of tinnitus burden at the end of treatment for CBT vs. watchful waiting

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Subgroup analysis

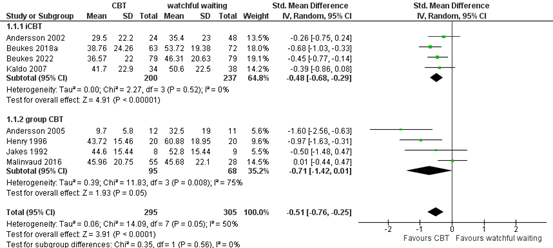

iCBT or group CBT vs. watchful waiting

A subgroup analysis was performed comparing CBT with watchful waiting, for internet CBT and group CBT. The standardized mean difference for iCBT vs. watchful waiting was -0.48 (95% CI -0.68 to -0.29), in favour of the patients who received iCBT. This difference is a moderate effect and considered to be clinically relevant in the context of psychological burden. The standardized mean difference for group CBT vs. watchful waiting was -0.71 (95% CI -1.42 to 0.01), in favour of the patients who received group CBT. This difference is considered to be a moderate-to-large and clinically relevant effect.

Figure 2. Subgroup analysis for iCBT and group CBT (CBT vs. watchful waiting)

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Walter (2023) reported change in tinnitus burden, measured by TQ. The patients who received CBT (n=94) had a mean change in TQ score of -13.36 (SE ± 1.00), compared with a mean change in TQ score of -0.63 (SE ± 0.98) for the patients who received watchful waiting (n=93). The difference between the groups was -12.74 (SE ± 1.38), in favour of the patients who received CBT. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Quality of life

One systematic review (Fuller, 2020) and one study (Beukes, 2022) reported the outcome measure quality of life. Both studies compared iCBT with watchful waiting. Since only two studies reported the outcome measure, the results were not pooled.

One study in the review by Fuller (2020) reported difference in health-related quality of life at the end of treatment, measured by the Satisfaction with Life Scales (Beukes, 2018a). The patients who received CBT (n=63) had a mean score of -18.3 (SD ± 6.7), compared with a mean score of -16.2 (SD ± 6.3) for the patients who received watchful waiting (n=72). The standardized mean difference was -0.33 (95% CI -0.67 to 0.01), in favour of the patients who received CBT. This difference is considered to be a small-to-moderate effect. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Beukes (2022) reported health-related quality of life, measured by EQ-5D-5L. The patients who received CBT (n=79) had a mean score of 7.38 (SD ± 2.24), compared with a mean score of 7.55 (SD ± 2.34) for the patients who received watchful waiting (n=79). The mean difference between CBT and watchful waiting was -0.17 (95% CI -0.88 to 0.54), in favour of the patients who received watchful waiting. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Serious adverse events

One systematic review and two studies reported the outcome measure serious adverse events (Beukes, 2022; Fuller, 2020; Walter, 2023). Both in the groups of patients who received CBT and the groups of patients who received watchful waiting no serious adverse events occurred.

CBT vs. usual care

Tinnitus burden (TQ, TRQ, THI)

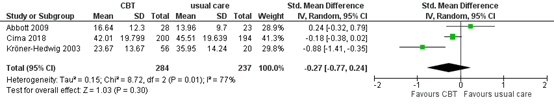

One systematic review (Fuller, 2020) and two studies (Cima, 2018; Kröner-Hedwig, 2003) reported the outcome measure tinnitus burden, measured by TQ and TRQ. In total, 284 patients received CBT and 237 patients received usual care. The standardized mean difference was -0.27 (95% CI -0.77 to 0.24), in favour of the patients who received CBT. This difference is considered to be a small effect. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 3. Meta-analysis of tinnitus burden at the end of treatment for CBT vs. usual care

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Cima (2018) also reported the outcome measure tinnitus burden, measured by THI three months post-treatment. The patients who received CBT (n=200) had a mean THI score of 34.25 (SE 1.66), and the patients who received usual care (n=194) had a mean THI score of 37.38 (SE 1.71). The mean difference between CBT and usual care was -3.13 (95% CI -7.80 to 1.54), in favour of cognitive behavioral therapy. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Subgroup analysis

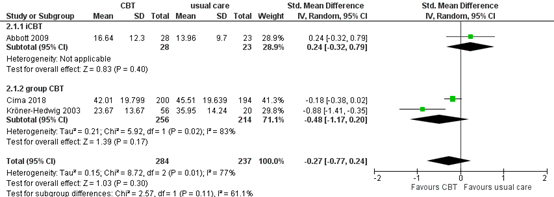

iCBT or group CBT vs. usual care

A subgroup analysis was performed comparing CBT with usual care, for internet CBT and group CBT. The standardized mean difference for iCBT vs. usual care was 0.24 (95% CI -0.32 to 0.79), in favour of the patients who received usual care. This difference is considered to be a small effect. The standardized mean difference for group CBT vs. usual care was -0.48 (95% CI -1.17 to 0.20), in favour of the patients who received group CBT. This difference is considered to be a moderate effect.

Figure 4. Subgroup analysis for iCBT and group CBT (CBT vs. usual care)

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Quality of life

One study reported the outcome measure quality of life. Cima (2018) reported health related quality of life. Health related quality of life was assessed with the HUI mark III, three months after baseline. The patients who received CBT (n=200) had a mean HUI score of 0.620 (SE 0.019), and the patients who received usual care (n=194) had a mean HUI score of 0.640 (SE 0.021). The mean difference between CBT and usual care was -0.020 (95% CI -0.08 to 0.04), in favour of usual care. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Serious adverse events

None of the included studies reported the outcome measure serious adverse events.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence was based on evidence from RCTs and therefore starts high for all outcome measures.

CBT vs. watchful waiting

Tinnitus burden

The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1). The level of evidence is therefore graded as moderate.

Quality of life

The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1), and because confidence interval exceeds the lower limit of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is therefore graded as low.

Serious adverse events

The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1). The level of evidence is therefore graded as moderate.

CBT vs. usual care

Tinnitus burden

The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1), and because confidence interval exceeds the lower limit of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is therefore graded as low.

Quality of life

The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1). The level of evidence is therefore graded as moderate.

Serious adverse events

The level of evidence was not graded since the outcome measure was not reported.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (un)favorable effects of CBT compared with watchful waiting/sham control/placebo/care as usual in adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus (≥3 months)?

P: patients: adult patients with chronic subjective tinnitus (≥3 months)

I: intervention: cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

C: control: watchful waiting/sham control/placebo/care as usual

O: outcome measure: tinnitus burden, quality of life, serious adverse events

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered tinnitus burden as a critical outcome measure for decision making; quality of life and serious adverse events as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Care as usual as defined by the authors (see description of studies);

- Tinnitus burden is defined by the impact of tinnitus on a person's daily life, including distress, and disability , such as depressed mood, anxiety, and functional handicaps, as measured with single- (NRS) or multi-item questionnaires (e.g. THI (tinnitus Handicap Inventory), TQ (Tinnitus Questionary), TFI (Tinnitus Functional Index), STSS (Subjective Tinnitus Severity Scale); HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale); VASi= Visual Analogue Scale intensity or impact; VASd (Visual Analogue Scale discomfort or intrusiveness); PSQI (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index); WHO-QoL (World Health Organization Quality of Life questionnaire); POMS (Profile Of Mood States).

- THI: The THI is a questionnaire that measures the subjective burden caused by tinnitus across three main domains: 1) Functional effects: Impact on daily activities like concentration and sleep; 2) Emotional effects: Feelings of frustration, irritation, depression, or anger caused by tinnitus, and 3) Catastrophic effects: A sense of helplessness, despair, or feeling that tinnitus is uncontrollable. The total score can range from 0 to 100, where a higher score indicates a greater level of tinnitus-related distress.

- The TFI measures various aspects of tinnitus burden. It is designed to track changes in tinnitus-related difficulties over time, especially in response to treatments. The TFI assesses eight domains: 1)Intrusiveness: How intrusive the tinnitus is; 2) Sensory qualities: How the tinnitus sound is perceived; 3) Cognition: The impact on concentration and memory; 4) Sleep: How tinnitus affects sleep; 5) Auditory: How tinnitus impacts hearing abilities; 6) Relaxation: Effects on the ability to relax; 7) Quality of life: General sense of well-being and satisfaction, and 8) Emotional distress: The emotional burden caused by tinnitus. The TFI provides a score ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating a greater impact of tinnitus.

- The (mini) TQ is designed to measure the distress caused by tinnitus, particularly the psychological and emotional burden. It focuses on the emotional response to tinnitus, such as feelings of anxiety, irritation, and helplessness, rather than on the physical aspects. Higher scores indicate a greater degree of tinnitus-related distress. The full TQ consists of 52 questions and each question can score up to 2 points. The scores can go up to a maximum of 84 points. The short version (mini TQ) consists of 12 questions, of which the maximum total score is 24 points.

- Quality of life in general;

- Serious adverse events.

The working group defined the following differences in outcomes as minimal clinically (patient) important:

- THI: 7 points (Fuller, 2020).

- TFI: 13 (Meikle, 2012)

- TQ: 8 (Zeman, 2012)

- Mini-TQ: 6 (Vanneste, 2011)

- HADS-A: 3.8 and HADS-D: 3.3 (De Filippis, 2024)

- VAS score: 15 points on a 100 scale, 1.5 on a 10 scale (Adamchic, 2021)

- Quality of life: 10%

- Serious adverse events: 25% (RR < 0.8 or RR > 1.25).

If different measurement instruments were pooled, then differences were defined as: a trivial effect (standardized mean difference (SMD) = 0 to 0.2), a small effect (SMD = 0.2 to 0.5), a moderate effect (SMD = 0.5 to 0.8), and a large effect (SMD >0.8).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID), Embase (via Embase.com) and PsychInfo were searched with relevant search terms until 4 July 2024. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 826 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials comparing psychological interventions with watchful waiting/sham control/placebo/care as usual in patients with chronic subjective tinnitus. In total, 49 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 36 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and thirteen studies were included. For this submodule CBT, 36 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 31 studies were excluded, and five studies were included.

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Adamchic I, Langguth B, Hauptmann C, Tass PA. Psychometric evaluation of visual analog scale for the assessment of chronic tinnitus. Am J Audiol. 2012 Dec;21(2):215-25. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2012/12-0010). Epub 2012 Jul 30. PMID: 22846637.

- Cima RFF, van Breukelen G, Vlaeyen JWS. Tinnitus-related fear: Mediating the effects of a cognitive behavioural specialised tinnitus treatment. Hear Res. 2018 Feb;358:86-97. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2017.10.003. Epub 2017 Oct 12. PMID: 29133012.

- De Ridder D, Schlee W, Vanneste S, Londero A, Weisz N, Kleinjung T, Shekhawat GS, Elgoyhen AB, Song JJ, Andersson G, Adhia D, de Azevedo AA, Baguley DM, Biesinger E, Binetti AC, Del Bo L, Cederroth CR, Cima R, Eggermont JJ, Figueiredo R, Fuller TE, Gallus S, Gilles A, Hall DA, Van de Heyning P, Hoare DJ, Khedr EM, Kikidis D, Kleinstaeuber M, Kreuzer PM, Lai JT, Lainez JM, Landgrebe M, Li LP, Lim HH, Liu TC, Lopez-Escamez JA, Mazurek B, Moller AR, Neff P, Pantev C, Park SN, Piccirillo JF, Poeppl TB, Rauschecker JP, Salvi R, Sanchez TG, Schecklmann M, Schiller A, Searchfield GD, Tyler R, Vielsmeier V, Vlaeyen JWS, Zhang J, Zheng Y, de Nora M, Langguth B. Tinnitus and tinnitus disorder: Theoretical and operational definitions (an international multidisciplinary proposal). Prog Brain Res. 2021;260:1-25. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2020.12.002. Epub 2021 Feb 1. PMID: 33637213.

- de Filippis R, Mercurio M, Segura-Garcia C, De Fazio P, Gasparini G, Galasso O. Defining the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) in the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in patients undergoing total hip and knee arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2024 Apr;110(2):103689. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2023.103689. Epub 2023 Sep 21. PMID: 37741440.

- Fuller T, Cima R, Langguth B, Mazurek B, Vlaeyen JW, Hoare DJ. Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Jan 8;1(1):CD012614. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012614.pub2. PMID: 31912887; PMCID: PMC6956618.

- Gilles A, Jacquemin L, Cardon E, Vanderveken OM, Joossen I, Vermeersch H, Vanhecke S, Van den Brande K, Michiels S, Van de Heyning P, Van Rompaey V. Long-term effects of a single psycho-educational session in chronic tinnitus patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022 Jul;279(7):3301-3307. doi: 10.1007/s00405-021-07026-7. Epub 2021 Oct 1. PMID: 34596715.

- Kröner-Herwig B, Frenzel A, Fritsche G, Schilkowsky G, Esser G. The management of chronic tinnitus: comparison of an outpatient cognitive-behavioral group training to minimal-contact interventions. J Psychosom Res. 2003 Apr;54(4):381-9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00400-2. PMID: 12670617.

- Lebeau RT, Davies CD, Culver NC, Craske MG. Homework compliance counts in cognitive- behavioral therapy. Cogn Behav Ther. 2013;42(3):171-9. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2013.763286. Epub 2013 Feb 18. PMID: 23419077.

- Meikle MB, Henry JA, Griest SE, Stewart BJ, Abrams HB, McArdle R, Myers PJ, Newman CW, Sandridge S, Turk DC, Folmer RL, Frederick EJ, House JW, Jacobson GP, Kinney SE, Martin WH, Nagler SM, Reich GE, Searchfield G, Sweetow R, Vernon JA. The tinnitus functional index: development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear Hear. 2012 Mar-Apr;33(2):153-76. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31822f67c0. Erratum in: Ear Hear. 2012 May;33(3):443. PMID: 22156949.

- Vanneste S, Plazier M, van der Loo E, Ost J, Meeus O, Van de Heyning P, De Ridder D. Validation of the Mini-TQ in a Dutch-speaking population: a rapid assessment for tinnitus-related distress. B-ENT. 2011;7(1):31-6. PMID: 21563554.

- Wagenaar O, Gilles A, Van Rompaey V, Blom H. Goal Attainment Scale in tinnitus (GAS-T): treatment goal priorities by chronic tinnitus patients in a real-world setting. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2024 Feb;281(2):693-700. doi: 10.1007/s00405-023-08134-2. Epub 2023 Jul 25. PMID: 37488402.

- Wagenaar OV, Wieringa M, Mantingh L, Kramer SE, Kok R. Preliminary longitudinal results of neuropsychological education as first and sole intervention for new tinnitus patients. Int Tinnitus J. 2016 Jul 22;20(1):11-7. doi: 10.5935/0946-5448.20160003. PMID: 27488988.

- Walter U, Pennig S, Kottmann T, Bleckmann L, Röschmann-Doose K, Schlee W. Randomized controlled trial of a smartphone-based cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic tinnitus. PLOS Digit Health. 2023 Sep 7;2(9):e0000337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pdig.0000337. PMID: 37676883; PMCID: PMC10484427.

- W Beukes E, Andersson G, Fagelson M, Manchaiah V. Internet-Based Audiologist-Guided Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Tinnitus: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2022 Feb 14;24(2):e27584. doi: 10.2196/27584. PMID: 35156936; PMCID: PMC8887633.

- Xiang T, Zhong J, Lu T, Pu JM, Liu L, Xiao Y, Lai D. Effect of educational counseling alone on people with tinnitus: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2020 Jan;103(1):44-54. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.07.031. Epub 2019 Jul 27. PMID: 31378310.

- Zeman F, Koller M, Schecklmann M, Langguth B, Landgrebe M; TRI database study group. Tinnitus assessment by means of standardized self-report questionnaires: psychometric properties of the Tinnitus Questionnaire (TQ), the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), and their short versions in an international and multi-lingual sample. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012 Oct 18;10:128. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-128. PMID: 23078754; PMCID: PMC354112

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Fuller, 2020

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to November 2019.

Wait list control A: Andersson, 2002 B: Andersson, 2005 C: Beukes, 2018a D: Henry, 1996 E: Henry, 1998 F: Jakes, 1992 G: Kaldo, 2007 H: Kreuzer, 2012 I: Malinvaud, 2016 (unpublished) J: Robinson, 2008

Other active control K: Abbott, 2009 L: Henry, 1996

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: A: Sweden B: Sweden C: England D: Australia E: Australia F: England G: Sweden H: Germany I: France J: USA K: Australia L: Australia

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: [commercial / non-commercial / industrial co-authorship] A: Swedish Council for Research and the Swedish Hard of Hearing Association, no conflicts of interest stated B: Grant from Swedish Hard of Hearing Association, no conflicts of interest reported C: No grant, no conflicts of interest declared D: not reported, not reported E: Not reported, not reported F: Locally Organised Research Scheme, not reported G: Grant from Swedish Hard of Hearing Association, no conflicts of interest declared H: MH supported by grant from Bundesverband der Innunkgskrankenkassen, authors grant from Tinnitus Research Initiative, MH wrote manual, other authors no conflict of interest I: Tinnitus Research Initiative Grant, no conflicts of interest declared J: The American Tinnitus Association, no conflicts of interest

K: Australian Research Council Linkage Project Grant, not reported L: not reported, not reported |

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs, participants were at least 18 years of age with tinnitus, CBT, ACT or mindfulness.

Exclusion criteria SR: not reported.

33 studies included for these comparisons

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N A: 117 B: 23 C: 146 D: 65 E: 50 F: 84 G: 72 H: 36 I: 148 J: 65 K: 56 L: 65

Mean age (I/C) A: 48.5, 47.2 B: 70.1 (overall) C: 56.8, 54.3 D: 64.6 E: 56.3 F: 59.2, 54.2 G: 45.9, 48.5 H: 49.6, 51.7 I: 49.1, 54.2 J: 55.0 K: 50.5, 48.7 L: 64.6

Sex %M (I/C): A: 54%, 52% B: 52% C: 57% D: 80% E: 62% F: 47.6% G: 51% H: 53% I: 68% J: 52% K: 82% L: 80%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention:

A: iCBT B: CBT C: iCBT D: cognitive coping skills training plus education E: cognitive restructuring F: group cognitive therapy G: guided bibliotherapy CBT H: mindfulness-based psychotherapy I: CBT J: CBT K: iCBT L: Cognitive Coping Skills Training plus education

|

Describe control:

A: wait list control B: wait list control C: wait list control D: wait list control E: wait list control F: wait list control G: wait list control H: wait list control I: wait list control J: wait list control K: information only L: education only, wait list control

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: 6 weeks of treatment, 12 months of follow-up. B: 6 weeks of treatment, 3 months of follow-up C: 8 weeks of treatment, 2 months of follow-up D: 6 weeks of treatment, 12 months of follow-up. E: 8 weeks of treatment, 6 months of follow-up. F: 5 weeks of treatment, 3 months of follow-up. G: 6 weeks of treatment, 12 months of follow-up. H: 22 weeks of treatment, no follow-up. I: 16 weeks of treatment, 3 months of follow-up J: 8 weeks of treatment, and 8, 16 and 52 weeks of follow-up. K: 6 weeks of treatment, follow-up: post intervention L: 6 weeks of treatment, 12 months of follow-up

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: 11 (7 from CBT, 4 from wait list) B: 0 C: 32 (19 iCBT, 13 waitlist) D: 14 (6 intervention, 8 waitlist) E: 11 F: 19 G: 12 (4 in CBT, 8 in waitlist) H: 3 (2 mind, 1 control) I: 14 (11 CBT, 3 waitlist) J: 24 (12 intervention, 12 comparison) K: 28 (23 CBT, 5 other control) L: 17 (6 intervention, 3 education, 8 wait list control)

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as tinnitus severity

Effect measure: SMD [95% CI]: Comparison 1 A: -0.26 (-0.75 to 0.24) B: -1.60 (-2.56 to -0.63) C: -0.69 (-1.03 to -0.34) D: -0.97 (-1.63 to -0.31) E: - F: -0.50 (-1.48 to 0.47) G: -0.39 (-0.86 to 0.08) H: -0.67 (-1.37 to 0.04) I: 0.01 (-0.44 to 0.47) J: -

Comparison 3 K: 0.24 (-0.32 to 0.79) L: -0.87 (-1.52 to -0.22)

Outcome measure-2 Defined as quality of life

Effect measure: RR, RD, mean difference [95% CI]: Comparison 1 A: - B: - C: -0.33 (-0.67 to 0.01) D: - E: - F: - G: - H: - I: - J: -

Comparison 3 K: - L: -

Outcome measure-3 Defined as adverse effects

A: none (personal communication) B: none (personal communication) C: no adverse effects were reported during the course of the intervention. However, at 12 months follow-up, 11 out 104 participants indicated that they had experienced: worsening of symptoms, emergence of new symptoms, negative well being and prolongation of treatment. D: - E: - F: - G: none (personal communication) H: - I: There were no adverse effects in the CBT group. J: none (personal communication)

K: - L: -

|

Risk of bias (high, some concerns or low): A: high (performance) B: unclear C: high (selection, performance, detection) D: unclear E: unclear F: high (reporting) G: high (performance) H: high (performance, detection) I: high (performance, detection, attrition reporting) J: high (performance, reporting)

K: high (performance, attrition, reporting) L: unclear

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion CBT may be effective in reducing the negative impact that tinnitus can have on quality of life. There is, however, an absence of evidence at 6 or 12 months follow-up. There is also some evidence that adverse effects may be rare in adults with tinnitus receiving CBT, but this could be further investigated. CBT for tinnitus may have small additional benefit in reducing symptoms of depression although uncertainty remains due to concerns about the quality of the evidence. Overall, there is limited evidence for CBT for tinnitus improving anxiety, health related quality of life or negatively biased interpretations of tinnitus

|

Evidence table for RCTs

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Cima, 2018 |

Single-centre randomized controlled trial

Setting and country: Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Funding: Trial funding by Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw). Johan WS Vlaeyen is supported by the Asthenes long-term structural funding Methusalem grant by the Flemish Government, Belgium.

Conflicts of interest: Authors declare no conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients who reported tinnitus complaints, aged 18 years and older.

Exclusion criteria: Being unable to read and write in Dutch, when medical conditions prevented patients to participate and when patients visited the centre within five years prior to trial enrolment.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 245 Control: 247

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: Intervention: 53.74 ± 11.05 Control: 54.63 ± 12.02

Gender %male: Intervention: 64.6 Control: 60.7

Duration (<1y, 1-5y, >5y) Intervention: 27.2, 39.9, 32.9 Control: 32.7, 37.9, 29.4

Health-related QoL, baseline (mean, SE): Intervention: 0.628, 0.018 Control: 0.641, 0.019

Tinnitus Severity (TQ), baseline (mean, SE): Intervention: 49.39, 1.18 Control: 48.87, 1.22

Tinnitus impairment (THI), baseline (mean, SE): Intervention: 39.25, 1.45

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Intervention: Specialised care (cognitive behavioural specialised tinnitus treatment) Specialized care consisted of comprehensive multidisciplinary diagnostics and treatment, offering tinnitus counselling elements with the use of a neuro-psychological model, within a CBT framework. Step one treatment consisted of an audiological and psychological assessment and primary counselling, step two (for patients with more severe tinnitus) treatment consisted of three different 12-week group-treatment options.

|

Control: Usual care A standardized protocol as is usually provided by secondary care audiological centres. Step one of UC treatment consisted of a standard audiological intervention and step two (for patients with more severe tinnitus) consisted of treatment twelve weeks maximally.

|

Length of follow-up: Three follow-up assessments up to 12 months after randomization.

Loss-to-follow-up: Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (30.2%) Reasons: N=45 missing measurements at T1: -n=1 part of a couple randomised into different treatments -n=1 not able, other activities -n=2 not able to proceed, other medical condition -n=2 no longer interested to fill in questionnaires -n=3 filling in questionnaires too stressful -n=18 reason unknown -n=18 missed measurement T1

N=25 missing measurements at T2: -n=2 not able to proceed, other medical condition -n=2 no longer interested to fill in questionnaires -n=1 not able, other priorities -n=4 reason unknown -n=16 missed measurement T2

N=4 missing measurements at T3

Control: N=86 (34.8%) Reasons: N=53 missing measurements at T1: -n=1 part of a couple randomised into different treatments -n=5 not satisfied -n=5 no longer interested to fill in questionnaire -n=1 not bothered by the tinnitus -n=2 chose other healthcare provider -n=30 reason unknown -n=9 missed measurement T1

N=33 missing measurements at T2 -n=4 not able to proceed, other medical condition -n=1 deceased -n=10 reason unknown -n=18 missed measurement T2 |

Health related QoL, 3 months: Intervention (n=200): 0.620, 0.019 Control (n=194): 0.640, 0.021

Health related QoL, 8 months: Intervention (n=175): 0.656, 0.019 Control (n=161): 0.634, 0.023

Health related QoL, 12 months: Intervention (n=171): 0.681, 0.019 Control (n=161): 0.631, 0.022

Tinnitus Severity TQ, 3 months: Intervention (n=200): 42.01, 1.40 Control (n=194): 45.51, 1.41

Tinnitus Severity TQ, 8 months: Intervention (n=175): 36.47, 1.32 Control (n=161): 42.36, 1.55

Tinnitus Severity TQ, 12 months: Intervention (n=171): 33.43, 1.29 Control (n=161): 42.12, 1.56

Tinnitus impairment THI, 3 months: Intervention (n=200): 34.25, 1.66 Control (n=194): 37.38, 1.71

Tinnitus impairment THI, 8 months: Intervention (n=175): 28.85, 1.55 Control (n=161): 34.14, 1.95

Tinnitus impairment THI, 12 months: Intervention (n=171): 26.45, 1.45 Control (n=161): 33.51, 1.84 |

|

|

Walter, 2023 |

Randomized interventional clinical trial

Setting and country: Germany

Funding and conflicts of interest: The study was funded by mynoise GmbH, the funders had no role in data collection and analysis. WS is stakeholder of the Lenox UG, a company which aims to translate research findings into digital health applications; SP, Leadership Consultant, member of context; UW, resident otorhinolaryngologist, developer of the Kalmeda Tinnitus app and managing director of mynoise GmbH; K R-D is employed by G. Pohl-Boskamp GmbH & Co. KG (distribution partner for Kalmeda), and WS, UW, LB receive personal fees from G. Pohl-Boskamp GmbH & Co. KG. TK, CEO of CRO Dr Kottmann received a contractual fee from mynoise for the conduct of the study. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients who were eighteen years of age and older, with chronic subjective tinnitus of more than three months duration were eligible for trial inclusion

Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of acute or chronic mental illness

N total at baseline: Intervention: 94 Control: 93

Important prognostic factors: Age ± SD: Total: 48.2 ± 12.5 years

Sex (male): Total: 97 (51.9%)

Tinnitus duration: Total: 6.57 ± 6.93 years

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Intervention: The intervention group received cognitive behavioral therapy through the Kalmeda Tinnitus app. The app consisted of five levels with nine steps each. Level one and two, focusing on behavioral therapy (redirecting attention and relaxation) are typically completed in three months. |

Control: The control group waited during three months, while the patients in the intervention group used the CBT app.

|

Length of follow-up: Three months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=16 (17.0%) Reasons (describe) -Lost- to follow-up (n=1) -Reason unknown (n=15)

Control: N=8 (8.6%) Reasons (describe) -Lost- to follow-up (n=1) -Reason unknown (n=7)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N=2 (2.1%) Reasons (describe) -Missing values for TF score (n=2)

Control: N=3 (3.2%) Reasons (describe) -Missing values for TF score (n=3)

|

Tinnitus burden TQ (LS mean ± SE) Difference: -12.74 ± 1.38, in favor of the intervention group I: -13.36 (SE ± 1.00) C: -0.63 (SE ± 0.98)

Adverse events No adverse events reported in both groups |

|

|

Beukes, 2022 |

Prospective intervention trial

Setting and country: Texas, US

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funded by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders of the National Institute of Health. No conflicts of interest declared. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients aged eighteen years or older, living in Texas, United States, with the ability to read and type in English or Spanish, who have access to a computer and the internet and were able to email, who experienced tinnitus for a minimum period of three months, with a tinnitus severity score of at least 25 on the Tinnitus Functional Index (indicating the need for an intervention).

Exclusion criteria: Exclusion criteria were indications of significant depression on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, indications of self-harm thoughts or intent, answer affirming question ten of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, reporting any medical or psychiatric conditions that could interfere with the treatment, reporting pulsatile, objective, or unilateral tinnitus, which has not been investigated medically or tinnitus still under medical investigation, and undergoing any tinnitus therapy concurrent with participation in the study.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 79 Control: 79

Important prognostic factors: Age ± SD: I: 56 ± 13 C: 58 ± 11

Sex (male): I: 40 (50.6%) C: 38 (48.1%)

Tinnitus duration: I: 15 ± 16 years C: 12 ± 12 years

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Intervention: The intervention group received an internet-based CBT intervention based on a self-help program, transformed into an eight-week interactive e-learning |

Control: The control group received no intervention during the first eight weeks but were weekly monitored. After eight weeks, the patients in the control group received the same intervention as the intervention group. |

Length of follow-up: Eight weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=35 (48.6%) Reasons (describe) -Not completed

Control: N=29 (38.2%) Reasons (describe) -Not completed

|

Tinnitus burden TFI Post-intervention (T1) Imputation I: 36.57 ± 22.00 C: 46.31 ± 20.63

Adverse events No serious adverse events

Health-related quality of life (EQ-5D-5L) Imputation I: 7.38 ± 2.24 C: 7.55 ± 2.34 |

|

|

Kröner-Hedwig, 2003 |

Randomized control group study

Setting and country: Germany

Funding and conflicts of interest: The study was supported by a grant from the German Ministry of Research and Technology. No conflicts of interest reported. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients who were between eighteen and 65 years old, with a duration of tinnitus that exceeded six months and with a medical diagnosis of idiopathic tinnitus as their main health problem, whose subjective annoyance by tinnitus reached an average rating of at least 40 on nine scales assessing disruptive effects of tinnitus were eligible for trial participation.

Exclusion criteria: Exclusion criteria were hearing loss preventing patients from participating in communication with groups and currently being in psychotherapeutic treatment.

N total at baseline: I: 56 C: 20

Important prognostic factors: Age ± SD: I: 44.7 ± 12.7 C: 47.3 ± 7.9

Gender (female): I: 55.8% C: 50%

Tinnitus duration (months): I: 55.4 ± 51.5 C: 57.4 ± 44.9

Hearing loss: I: 55.8% C: 20%

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Intervention: The intervention group received Tinnitus Coping Training which consisted of 11 sessions with a 90-120 minute duration focusing, amongst others, on education, relaxation, attention and distraction, dysfunctional and functional thoughts, coping, and problem solving. |

Control: The patients in the control group received no intervention, but were placed on a waiting list. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=13 (23.2%) Reasons (describe) -Not reported

Control: N=0 (0%) Reasons (describe)

|

Tinnitus burden TQ I: 23.67 ± 13.67 C: 35.95 ± 14.24

TDI I: 1.81 ± 1.32 C: 3.07 ± 1.98

|

|

Risk of bias tabel

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Cima, 2018 |

Probably yes

Reason: Random allocation to intervention and control. |

No information

|

Probably yes

Reason: Both patients and assessors were blinded for treatment allocation. |

Definitely no

Reason: Loss-to-follow-up was frequent, both in intervention (30.2%) and control group (34.8%). |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted. |

Some concerns (all outcomes)

|

|

Walter, 2023 |

Definitely yes

Reason: A non-stratified block randomization strategy was followed to randomly assign blocks of six patients in consecutive order to the two study arms. |

No information

Reason: Not reported. |

Definitely no

Reason: Due to the nature of treatment no blinding was possible. |

Definitely no

Reason: Loss-to-follow-up was more than 10%. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcome measures mentioned in the methods section were reported. |

Probably no

Reason: the use of the app was not completely guided, concomitant therapy was not documented throughout the study. |

Some concerns

|

|

Beukes, 2022 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Participants were randomly assigned using a computer-generated randomization schedule by an independent research assistant. |

No information

Reason: Not reported. |

Definitely no

Reason: Participants and investigators could not be blinded to the group allocation owing to the nature of the intervention. |

Definitely no

Reason: Loss-to-follow-up was more than 10%. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcome measures mentioned in the methods section were reported. |

Definitely no

Reason: The study population may not present the typical tinnitus population, the study was conducted during COVID-19, when day-to-day living was disrupted for many people. |

HIGH |

|

Kröner-Hedwig, 2003 |

Probably yes

Reason: Patients were assigned code numbers by drawing from the total sample and then sequentially assigning patients to the four treatment conditions. |

No information

Reason: Not reported. |

No information

Reason: Not reported. |

Definitely no

Reason: Loss-to-follow-up was more than 10%. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcome measures mentioned in the methods section were reported. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other problems noted. |

Some concerns |

Exclusie tabel

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Aazh H, Landgrebe M, Danesh AA, Moore BC. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Alleviating The Distress Caused By Tinnitus, Hyperacusis And Misophonia: Current Perspectives. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019 Oct 23;12:991-1002. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S179138. PMID: 31749641; PMCID: PMC6817772. |

Literature review, not systematic |

|

Andersson G. Clinician-Supported Internet-Delivered Psychological Treatment of Tinnitus. Am J Audiol. 2015 Sep;24(3):299-301. doi: 10.1044/2015_AJA-14-0080. PMID: 26649534. |

Studies included in Fuller |

|

Beukes EW, Allen PM, Baguley DM, Manchaiah V, Andersson G. Long-Term Efficacy of Audiologist-Guided Internet-Based Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Tinnitus. Am J Audiol. 2018 Nov 19;27(3S):431-447. doi: 10.1044/2018_AJA-IMIA3-18-0004. PMID: 30452747; PMCID: PMC7018448. |

Wrong study design: Pre-post intervention data |

|

Beukes EW, Andersson G, Manchaiah V. Long-term efficacy of audiologist-guided Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for tinnitus in the United States: A repeated-measures design. Internet Interv. 2022 Oct 30;30:100583. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2022.100583. PMID: 36353148; PMCID: PMC9637888. |

No control |

|

Beukes EW, Andersson G, Manchaiah V. Patient Uptake, Experiences, and Process Evaluation of a Randomized Controlled Trial of Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Tinnitus in the United States. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021 Nov 17;8:771646. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.771646. PMID: 34869490; PMCID: PMC8635963. |

Wrong study design: process evaluation |

|

Beukes EW, Baguley DM, Allen PM, Manchaiah V, Andersson G. Audiologist-Guided Internet-Based Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Adults With Tinnitus in the United Kingdom: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ear Hear. 2018 May/Jun;39(3):423-433. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000505. PMID: 29095725. |

Included in SR Fuller |

|

Beukes EW, Manchaiah V, Allen PM, Baguley DM, Andersson G. Internet-Based Interventions for Adults With Hearing Loss, Tinnitus, and Vestibular Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trends Hear. 2019 Jan-Dec;23:2331216519851749. doi: 10.1177/2331216519851749. PMID: 31328660; PMCID: PMC6647231. |

SR Fuller more recent |

|

Beukes EW, Manchaiah V, Baguley DM, Allen PM, Andersson G. Process evaluation of Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for adults with tinnitus in the context of a randomised control trial. Int J Audiol. 2018 Feb;57(2):98-109. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2017.1384858. Epub 2017 Oct 9. PMID: 28990807. |

Wrong study design: process evaluation |

|

Cima RF, Andersson G, Schmidt CJ, Henry JA. Cognitive-behavioral treatments for tinnitus: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Audiol. 2014 Jan;25(1):29-61. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.25.1.4. PMID: 24622860. |

Descriptive results, no absolute values. |

|

Conrad I, Kleinstäuber M, Jasper K, Hiller W, Andersson G, Weise C. The changeability and predictive value of dysfunctional cognitions in cognitive behavior therapy for chronic tinnitus. Int J Behav Med. 2015 Apr;22(2):239-50. doi: 10.1007/s12529-014-9425-3. PMID: 25031187. |

Wrong control: web-based discussion forum |

|

Curtis F, Laparidou D, Bridle C, Law GR, Durrant S, Rodriguez A, Pierzycki RH, Siriwardena AN. Effects of cognitive behavioural therapy on insomnia in adults with tinnitus: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2021 Apr;56:101405. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101405. Epub 2020 Dec 1. PMID: 33360841. |

SR Fuller more recent |

|

Ducasse D, Fond G. La thérapie d'acceptation et d'engagement [Acceptance and commitment therapy]. Encephale. 2015 Feb;41(1):1-9. French. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2013.04.017. Epub 2013 Nov 18. PMID: 24262333. |

Article in French |

|

Grewal R, Spielmann PM, Jones SE, Hussain SS. Clinical efficacy of tinnitus retraining therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy in the treatment of subjective tinnitus: a systematic review. J Laryngol Otol. 2014 Dec;128(12):1028-33. doi: 10.1017/S0022215114002849. Epub 2014 Nov 24. PMID: 25417546. |

Included studies also in Fuller, other studies before 2014 |

|

Herbert MS, Dochat C, Wooldridge JS, Materna K, Blanco BH, Tynan M, Lee MW, Gasperi M, Camodeca A, Harris D, Afari N. Technology-supported Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for chronic health conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2022 Jan;148:103995. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2021.103995. Epub 2021 Nov 12. PMID: 34800873; PMCID: PMC8712459. |

Wrong control group: Online discussion forum |

|

Jasper K, Weise C, Conrad I, Andersson G, Hiller W, Kleinstäuber M. Internet-based guided self-help versus group cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic tinnitus: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(4):234-46. doi: 10.1159/000360705. Epub 2014 Jun 19. PMID: 24970708. |

Wrong comparison: iCBT vs group CBT |

|

Jasper, K., Weise, C., Conrad, I., Andersson, G., Hiller, W., & Kleinstäuber, M. (2014). The working alliance in a randomized controlled trial comparing Internet-based self-help and face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for chronic tinnitus. Internet interventions, 1(2), 49-57. |

Wrong comparison: iCBT vs gCBT |

|

Lan T, Cao Z, Zhao F, Perham N. The Association Between Effectiveness of Tinnitus Intervention and Cognitive Function-A Systematic Review. Front Psychol. 2021 Jan 6;11:553449. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.553449. PMID: 33488438; PMCID: PMC7815700. |

No conform PICO |

|

Landry EC, Sandoval XCR, Simeone CN, Tidball G, Lea J, Westerberg BD. Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Cognitive and/or Behavioral Therapies (CBT) for Tinnitus. Otol Neurotol. 2020 Feb;41(2):153-166. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002472. PMID: 31743297. |

SR Fuller more complete |

|

Li J, Jin J, Xi S, Zhu Q, Chen Y, Huang M, He C. Clinical efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic subjective tinnitus. Am J Otolaryngol. 2019 Mar-Apr;40(2):253-256. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2018.10.017. Epub 2018 Oct 29. PMID: 30477911. |

Wrong comparison: masking therapy + sound treatment vs. sound treatment + CBT |

|

Lu T, Wang Q, Gu Z, Li Z, Yan Z. Non-invasive treatments improve patient outcomes in chronic tinnitus: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2024 Jul-Aug;90(4):101438. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2024.101438. Epub 2024 May 2. PMID: 38788246; PMCID: PMC11143903. |

SR Fuller more recent |

|

Maes IH, Cima RF, Anteunis LJ, Scheijen DJ, Baguley DM, El Refaie A, Vlaeyen JW, Joore MA. Cost-effectiveness of specialized treatment based on cognitive behavioral therapy versus usual care for tinnitus. Otol Neurotol. 2014 Jun;35(5):787-95. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000331. PMID: 24829038. |

Wrong outcome measure |

|

McKenna L, Vogt F, Marks E. Current Validated Medical Treatments for Tinnitus: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2020 Aug;53(4):605-615. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2020.03.007. Epub 2020 Apr 23. PMID: 32334871. |

Narrative review |

|

Nolan DR, Gupta R, Huber CG, Schneeberger AR. An Effective Treatment for Tinnitus and Hyperacusis Based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in an Inpatient Setting: A 10-Year Retrospective Outcome Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020 Feb 7;11:25. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00025. PMID: 32116842; PMCID: PMC7020229. |

Wrong study design: no RCT |

|

Nyenhuis, N. (2015). Kognitiv-verhaltenstherapeutische Selbsthilfeinterventionen bei akutem und chronischem idiopathischem Tinnitus [Cognitive behavior therapeutic (CBT) self-help interventions in acute and chronic idiopathic tinnitus]. Verhaltenstherapie & Psychosoziale Praxis, 47(2), 343–357. |

Article in German |

|

Ost LG. The efficacy of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2014 Oct;61:105-21. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.07.018. Epub 2014 Aug 19. PMID: 25193001. |

Studies included in Fuller |

|

Patel N, Malicka AN, McGinnity S, Anderson RB, Paolini AG, Crosland P. Cost Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for the Treatment of Subjective Tinnitus in Australia. Ear Hear. 2022 Mar/Apr;43(2):507-518. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000001112. PMID: 34456302. |

Full text not available, wrong outcome measure |

|

Ungar OJ, Handzel O, Abu Eta R, Martz E, Oron Y. Meta-Analysis of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Tinnitus. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023 Dec;75(4):2921-2926. doi: 10.1007/s12070-023-03878-z. Epub 2023 May 26. PMID: 37974721; PMCID: PMC10645678. |

Included in submodule ACT |

|

Weise C, Kleinstäuber M, Andersson G. Internet-Delivered Cognitive-Behavior Therapy for Tinnitus: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychosom Med. 2016 May;78(4):501-10. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000310. PMID: 26867083. |

Wrong control: moderated online discussion forum |

|

Zenner HP, Delb W, Kröner-Herwig B, Jäger B, Peroz I, Hesse G, Mazurek B, Goebel G, Gerloff C, Trollmann R, Biesinger E, Seidler H, Langguth B. A multidisciplinary systematic review of the treatment for chronic idiopathic tinnitus. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 May;274(5):2079-2091. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4401-y. Epub 2016 Dec 19. PMID: 27995315. |

SR Fuller is more recent |

|

Zhong C, Zhong Z, Luo Q, Qiu Y, Yang Q, Liu Y. [The curative effect of cognitive behavior therapy for the treatment of chronic subjective tinnitus]. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2014 Apr;29(8):709-11. Chinese. PMID: 26248442. |

Article in Chinese |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 21-07-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 11-07-2025

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules is in 2020 een multidisciplinair cluster ingesteld. Dit cluster bestaat uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante organisaties die betrekking hebben op de zorg voor patiënten met gehoorproblemen.

Het cluster Otologie bestaat uit meerdere richtlijnen, zie hier voor de actuele clusterindeling. De stuurgroep bewaakt het proces van modulair onderhoud binnen het cluster. De expertisegroepsleden worden indien nodig gevraagd om hun expertise in te zetten voor een specifieke richtlijnmodule. Het cluster Otologie bestaat uit de volgende personen:

Clusterstuurgroep

- Dr. A.L. (Diane) Smit, voorzitter cluster otologie, KNO-arts, UMC Utrecht (vanaf juni 2024 tot heden)

- Drs. M. (Monique) Campman-Verhoeff, voorzitter cluster otologie, KNO-arts, Treant Zorggroep, Emmen (van november 2023 tot juni 2024)

- Dr. E. (Erik) van Spronsen, KNO-arts, Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, Amsterdam

- Drs. R.M. (Robert) van Haastert, KNO-arts, Dijklander Ziekenhuis, Purmerend

- Drs. M.J. (Thijs) Vaessen, Oogarts, Deventer Ziekenhuis, Deventer

- Dr. Y.J.W. (Yvonne) Simis, Klinisch fysicus, audioloog, Amsterdam UMC locatie VUmc, Amsterdam (tot augustus 2023)

- Dr. ir. F.L. (Femke) Theelen, Audioloog, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam (vanaf augustus 2023)

- Drs. S.A.H. (Sjoert) Pegge, Radioloog, Radboudumc, Nijmegen

Betrokken clusterexpertisegroep

- Dr. A.L. (Diane) Smit, KNO-arts, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht

- Dr. C.A. (Katja) Hellingman, KNO-arts, Maastricht UMC, Maastricht

- Dr. E.L.J. (Erwin) George, Klinisch fysicus, Maastricht UMC, Maastricht

- Ir. C.W.M. (Chris) van den Dries, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Stichting Hoormij.NVVS

- Drs. O.V.G. (Olav) Wagenaar, klinisch neuropsycholoog, Rijndam Revalidatiecentrum, Rotterdam

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. R. (Romy) Zwarts-van de Putte, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. E.R.L. (Evie) Verweg, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle clusterstuurgroepleden en actief betrokken expertisegroepleden (fungerend als schrijver en/of meelezer bij tenminste één van de geprioriteerde richtlijnmodules) hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een richtlijnmodule worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de projectleider doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase. Een overzicht van de belangen van de clusterleden en betrokken expertisegroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Clusterstuurgroep

Tabel 1. Gemelde (neven)functies en belangen stuurgroep

|

Clusterlid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Spronsen |

KNO-arts, Amsterdam UMC |

Raad van Advies START |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Vaessen |

Oogarts Deventer Ziekenhuis, Oogarts Streekziekenhuis Koningin Beatrix te Winterswijk |

Geen |

Samen met Sallandse Specialisten Coorporatie aandeelhouder in een drietal |

Geen restrictie, de financiële belangen die worden gemeld hebben geen betrekking op de herziene modules |

|

Simis (tot augustus 2023) |

Klinisch Fysicus – Audioloog |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Van Haastert |

KNO-arts Dijklanderziekenhuis Hoorn/Purmerend |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Smit |

KNO arts UMC Utrecht, afdeling KNO |

Medisch adviseur Stichting Hoormij, onbetaald |

-Medeaanvrager en onderzoeker van MinT-studie over toepassing van mindfulness bij tinnitus, gefinancierd door HandicapNL |

Geen restrictie, de studie die betrekking heeft op tinnitus is niet gefinancierd door een commerciële partij |

|

Campman-Verhoeff |

KNO-arts Treant Zorggroep |

Bestuurslid stichting nascholing KNO – onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Pegge |

Radioloog Radboud UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Theelen (vanaf augustus 2023) |

Klinisch Fysicus – Audioloog, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

Clusterexpertisegroep

Tabel 2. Gemelde (neven)functies en belangen expertisegroep

|

Clusterlid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Hofman |

KNO-arts UMCG, Groningen |

Geen |

Copromotor van een promovendus die onderzoek doet naar beengeleidingsimplantaten (BCD), onderzoek is gesponsord door Oticon medical. Een BCD helpt niet tegen tinnitus. |

Geen restrictie, geen connectie tussen extern gefinancierd onderzoek en herziene modules |

|

Hellingman |

KNO-arts/otoloog MUMC+, Maastricht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

George |

Klinisch fysicus-audioloog, Maastricht UMC+ |

- bestuurslid Stichting Opleiding Klinische Fysica (onbetaald) |

ELEPHANT-studie (2018-2022) en RHINO-studie (vanaf 2022), wetenschappelijke research; promovendus grotendeels gefinancieerd door Advanced Bionics, op gebied van optimalisatie van outcomes van cochleaire implantatie. Geen vergoeding voor mijzelf. -Reguliere samenwerking met patientenorganisatie Stichting Hoormij, geen boegbeeldfunctie. |

Geen restrictie, deze studies hebben geen betrekking op de modules die in deze cyclus zijn herzien |

|

Wagenaar |

Klinisch neuropsycholoog/opleider bij Revalidatiecentrum Rijndam |

Tinnituszorg (onbetaald) Columnist Earline (betaald)

|

Financiële belangen: Royalty’s boek EHBOorsuizen Royalty’s online zelf-CGT eHBOorsuizen Academischbelang in VR gamificatie TinniVRee Intellectuele belangen : Neuropsychologisch verklaringsmodel tinnitus & hyperacusis. EHBOorsuizen FB peersupportgroup |

Geen restrictie, de boeken zijn niet van toepassing om naar te refereren in de richtlijn. TinniVRee is ook niet een van de onderwerpen die worden besproken in deze richtlijn. |

|

Van den Dries |

Vrijwilliger bij Stichting Hoormij NVVS Lid van Commissie Tinnitus en Hyperacusis als belangenbehartiger en voorlichter |

Moderator van de Facebookgroep Eerste Hulp bij Oorsuizen/Tinnitus |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door deelname van relevante patiëntenorganisaties aan de need-for-update en/of prioritering. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijnmodule is tevens ter commentaar voorgelegd aan alle relevante patiëntenorganisaties in de stuur- en expertisegroep (zie ‘Samenstelling cluster’ onder ‘Verantwoording’) en aan alle patiëntenorganisaties die niet deelnemen aan de stuur- en expertisegroep, maar wel hebben deelgenomen aan de need-for-update (zie ‘Need-for-update’ onder ‘Verantwoording’). De eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Bij de richtlijnmodule is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd om te beoordelen of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module [Behandeling van patiënten met tinnitus – Psychologische interventies – CGT] |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 3.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Need-for-update, prioritering en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de need-for-update fase (voorjaar, 2021) inventariseerde het cluster de geldigheid van de richtlijnmodules binnen het cluster. Naast de partijen die deelnemen aan de stuur- en expertisegroep zijn hier ook andere stakeholders voor benaderd. Per richtlijnmodule is aangegeven of deze geldig is, herzien moet worden, kan vervallen of moet worden samengevoegd. Ook was er de mogelijkheid om nieuwe onderwerpen aan te dragen die aansluiten bij één (of meerdere) richtlijn(en) behorend tot het cluster. De richtlijnmodules waarbij door één of meerdere partijen werd aangegeven herzien te worden, werden doorgezet naar de prioriteringsronde. Ook suggesties voor nieuwe richtlijnmodules werden doorgezet naar de prioriteringsronde. Afgevaardigden vanuit de partijen in de stuur- en expertisegroep werden gevraagd om te prioriteren (zie ‘Samenstelling cluster’ onder ‘Verantwoording’). Hiervoor werd de RE-weighted Priority-Setting (REPS) – tool gebruikt. De uitkomsten (ranglijst) werd gebruikt als uitgangspunt voor de discussie. Voor de geprioriteerde richtlijnmodules zijn door de het cluster concept-uitgangsvragen herzien of opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde het cluster welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. Het cluster waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde het cluster tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd indien mogelijk gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding). GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

Tabel 3. Gradaties voor de kwaliteit van wetenschappelijk bewijs

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in een richtlijnmodule volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)