Mobiliseren na een SAB

Uitgangsvraag

Vanaf wanneer kan een patiënt met een aneurysmatische subarachnoïdale bloeding (SAB) veilig gemobiliseerd worden?

Aanbeveling

Start met mobilisatie, tenminste 24 uur na bloeding bij adequate behandeling van het aneurysma, bij een klinisch stabiel beeld en op geleide van het klinisch beeld (neurologisch, hemodynamisch). Hanteer hierbij een opbouwschema: van lig-zit in bed met uitbreiding, naar bed-stoel mobilisatie met uitbreiding, na 48 uur.

Overweeg bij ernstiger aangedane patiënten, kortere en frequentere mobilisatie.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Het doel van deze uitgangsvraag was om te achterhalen wat de toegevoegde waarde is van vroege mobilisatie voor patiënten met een aneurysmatische subarachnoïdale bloeding (aSAB). In de literatuur is gezocht naar studies die vroege mobilisatie vergeleken met late mobilisatie in patiënten met een aSAB. Er werden vijf studies, waaronder één RCT en vier observationele (cohort) studies, gevonden die aan de selectiecriteria voldoen. Echter, deze studies hebben verschillende methodologische beperkingen (risico op bias). De RCT geeft geen informatie met betrekking tot het randomisatieproces en de toewijzing van patiënten. Wat betreft de observationele studies, is er ontbrekende informatie over confounding, hoe hiermee is omgegaan, en hoe de uitkomstmaten zijn beoordeeld. Een studie gebruikte onafhankelijke, niet-geblindeerde beoordeling van uitkomstmaten. En twee studies selecteerden hun blootgestelde en niet-blootgestelde deelnemers uit verschillende populaties. Daarnaast overlapten de betrouwbaarheidsintervallen met de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming. De bewijskracht van de literatuur is daardoor laag tot zeer laag voor alle uitkomstmaten. Dit betekent dat nieuwe studies kunnen leiden tot andere conclusies. Derhalve kunnen er op basis van de literatuur geen sterke conclusies worden getrokken over de effectiviteit van vroege mobilisatie in de behandeling van patiënten met een aSAB.

Na de acute behandeling van een aSAB, is het beleid in het algemeen gericht op monitoring, preventie en behandeling van secundaire cerebrale schade als een cruciale risicofactor voor een slechte neurologische uitkomst en een verhoogde sterfte. Een belangrijke barrière voor (vroege) mobilisatie is de angst voor inductie van recidief bloeding en vasospasmen/secundaire ischemie. Daarentegen kan worden aangenomen dat bedrust en fysieke inactiviteit de kans op spierverval, botresorptie, hart- en longproblemen, diepe veneuze trombose (DVT) en longembolie verhogen, en op de langere termijn het functioneel herstel belemmeren. Zeker bij de oudere patiënt worden de negatieve effecten van bedrust al langer onderkend (Brown, 2004; Zisberg, 2015). Bij herseninfarct en hersenbloeding zijn er aanwijzingen dat vroege mobilisatie rondom een periode van verhoogde neuroplasticiteit door taak specifieke training (Biernaskie, 2004) het neurale herstel bevordert. Bij aSAB gaat het dus specifiek om de afweging van de risico’s van acute bijwerkingen van (vroege) mobilisatie versus de risico’s op complicaties van immobilisatie op korte termijn en de voordelen van mobilisatie op de langere termijn.

Uit de literatuur blijkt onvoldoende bewijs voor negatieve (recidief bloeding, vasospasmen/secundaire ischemie en hydrocephalus) dan wel positieve effecten (vaardigheid/activiteiten als ADL zelfstandigheid, loopvaardigheid, length-of-stay) van (vroege) mobilisatie na aSAB. Dit heeft te maken met het lage aantal studies, geïncludeerde patiënten en de kwaliteit (bias, imprecisie). De aanwezige literatuur duidt echter niet op een evident verhoogd risico op complicaties. Daarentegen wordt een beschermend effect gesuggereerd van mobilisatie op vasospasmen en een hogere kans op een betere uitkomst op vaardigheids-/activiteitenniveau op 3 maanden. Bovenstaande ondersteunt een beleid waarin mobilisatie wordt gestart, afhankelijk van de stabiliteit van het aneurysma, de neurologische status en de algehele klinische toestand, dus op geleide van het klinisch beeld (hemodynamisch stabiel en neurologisch stabiel, i.e. geen tekenen van recidief bloeding en vasospasmen/secundaire ischemie en geen verandering van neurologisch beeld).

Een dergelijk beleid vraagt ondersteuning, standaardisering en verdere precisering in de vorm van richtlijnen met betrekking tot tijdstip van mobiliseren, vorm, duur en frequentie van mobiliseren (definitie), inschatting en afstemming op het klinisch beeld en het monitoren daarvan tijdens en na mobilisatie. Dit vereist een expliciete definitie van wat ‘vroeg’ inhoudt, en ook van wat ‘mobilisatie’ inhoudt. De huidige literatuur met betrekking tot aSAB biedt hiervoor onvoldoende aanknopingspunten (tijdstip, definitie van mobilisatie en mogelijke interactie met patiënt karakteristieken).

Tijdstip

Bij de studies tot nu toe verricht, is vroege mobilisatie gestart op dag 4 en eerder na bloeding (studie van Foudhaili (2023), maar niet nader gespecificeerd. In de AVERT-trial bij CVA-patiënten (ischemisch en hemorragisch) werden de effecten van vroege mobilisatie binnen 24 uur onderzocht: patiënten die een intensieve en vroege mobilisatie kregen, hadden over het algemeen een lagere kans op een gunstige functionele uitkomst zoals gemeten met de mRS na drie maanden, vergeleken met patiënten die standaardzorg kregen met een meer geleidelijke benadering van mobilisatie. Langhorne (2018) concludeerde vanuit bewijs van lage kwaliteit uit een verkennende netwerk-meta-analyse dat mobilisatie na ongeveer 24 uur geassocieerd is met het beste resultaat bij CVA-patiënten.

Vorm en interactie met klinisch beeld.

Een juiste definitie van mobilisatie is elke activiteit uit bed (Bernhardt, 2007). Dit ter onderscheid van elke vorm van fysieke training in bed. Karic (2017) suggereert daarnaast op basis van een positieve associatie van mate van mobilisatie met incidentie van vasospasmen een specifiek kinetisch gunstig effect van hoofdbeweging op de liquorcirculatie met als gevolg preventie van vasospasmen.

In een post hoc analyse van de AVERT-trial naar de therapie gerelateerde factoren die geassocieerd waren met een gunstigere uitkomst (mRS 0-2) bleken de frequentie van mobiliseren (OR: 13% toename per sessie) en de duur (6% afname bij elke 5 minuten langere mobilisatie) de belangrijkste factoren te zijn geassocieerd met gunstige uitkomst op 3 maanden (Bernhardt, 2016). De nadelige effecten van vroeg mobiliseren (dus uit bed en binnen 24 uur) op herstel van zelfstandigheid waren meer uitgesproken bij patiënten met een hersenbloeding (n=255) en patiënten met ernstige neurologische uitval (NIHSS>16) bij opname.

Samengevat ontbreekt het dus aan bewijs van de effecten in gunstige dan wel ongunstige zin van zeer vroege (<24 uur) en vroege mobilisatie uit bed (tussen 24-48 uur post-event en 4 dagen). Het lijkt verstandig zeker in de beginfase en zeker bij de ernstiger aangedane aSAB patiënten, de mobilisatieduur te beperken ten opzichte van de frequentie.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

In de acute fase zal angst voor vallen of verdere schade een punt van aandacht zijn, vooral bij intensieve vroege mobilisatie na een ingrijpende gebeurtenis als een aSAB. Patiënten hebben vaak een voorkeur voor revalidatie afgestemd op hun persoonlijke conditie en herstelvermogen, aanpassing van het tempo van mobilisatie aan hun eigen mogelijkheden en beperkingen behoort hiertoe. Een belangrijke overweging voor patiënten is de impact van vroege mobilisatie op hun algehele kwaliteit van leven. De literatuur geeft geen bewijs met betrekking tot kwaliteit van leven, mede ook omdat lange termijn follow-up ontbreekt. Vroegtijdige start van fysieke revalidatie na een herseninfarct of hersenbloeding (binnen 7 dagen) is in verband gebracht met een betere kwaliteit van leven (Musicco, 2003). Echter, de AVERT-trial (mobilisatie < 24 uur) liet geen verschil zien in kwaliteit van leven op 12 maanden zoals gemeten met de Assessment of Quality of Life 4D (Cumming, 2019).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Gunstige effecten van vroege mobilisatie bij aSAB op het middelenbeslag zullen direct gelieerd zijn aan Length-of-Stay (LoS) en ontslag naar de thuissituatie en indirect aan vermindering van complicaties en verbetering van uitkomst op lange termijn. De huidige literatuur is niet conclusief op de uitkomstmaat LoS, hoewel individuele studies een positief effect lieten zien van vroege mobilisatie. Vroege mobilisatie op een stroke-unit bleek onafhankelijk geassocieerd met ontslag naar huis binnen zes weken (Indredavik, 1999).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De aanvaardbaarheid van vroege mobilisatie na een aSAB is afhankelijk van de voordelen die het biedt versus de risico's die het met zich meebrengt. In het algemeen wordt mobilisatie in de acute fase vaak beperkt vanwege de risico's op recidief bloeding, en vasopasmen met risico op secundaire ischemie. Vanuit revalidatieperspectief kan vroege mobilisatie helpen om op korte termijn complicaties zoals longontsteking, diepe veneuze trombose (DVT), spieratrofie en decubitus te voorkomen met kortere ziekenhuisopnamen en op de langere termijn beter uitkomsten op zelfstandigheid, vaardigheid en activiteiten als ADL.

De haalbaarheid van vroege mobilisatie hangt af van de neurologische status van de patiënt, de stabiliteit van het aneurysma en de capaciteiten van het zorgteam. Haalbaarheid kan variëren tussen patiënten afhankelijk van hun medische en neurologische toestand.

- Medische stabiliteit: Een patiënt moet hemodynamisch stabiel zijn en het aneurysma moet adequaat zijn behandeld (bijv. door endovasculaire coiling of chirurgische clipping) voordat mobilisatie veilig overwogen kan worden.

- Neurologische toestand: Patiënten met een goede tot redelijke neurologische status (bijv. lage score op de Hunt en Hess-schaal) kunnen eerder baat hebben bij mobilisatie dan ernstig aangedane patiënten.

- Interdisciplinair team: Een ervaren interdisciplinair team bestaande uit neurochirurgen, intensivisten, fysiotherapeuten, ergotherapeuten en verpleegkundigen is essentieel om veilige mobilisatie te waarborgen.

- Beperkingen van haalbaarheid: ernstig neurologisch beeld of andere medische complicaties zoals hoge intracraniële druk (ICP) kunnen mobilisatie beperken. Ventriculaire drainages of complexe beademingsinstellingen kunnen mobilisatie bemoeilijken.

De implementatie van vroege mobilisatie moet zorgvuldig worden gepland, waarbij rekening wordt gehouden met het tijdstip, de intensiteit en de monitoring van de mobilisatie. Vaak wordt begonnen met passieve mobilisatie (bijv. veranderingen in houding) en wordt dit geleidelijk uitgebreid naar actieve mobilisatie (zoals zitten en opstaan). Dit vereist een gecoördineerde actie door artsen, verpleegkundigen en fysiotherapeuten en ergotherapeuten om ervoor te zorgen dat mobilisatie veilig en effectief is. Mobilisatie moet gepaard gaan met een monitoring van vitale functies en neurologische tekenen om snel in te grijpen bij complicaties.

De volgende implementatie-uitdagingen kunnen worden geïdentificeerd: 1) Variabiliteit in protocollen: er is geen universeel protocol voor (vroege) mobilisatie na aSAB, wat leidt tot variatie in de klinische praktijk; 2) Timing en individualisatie: Het is belangrijk dat het moment van mobilisatie wordt afgestemd op de individuele patiënt, omdat te vroeg beginnen risico’s kan opleveren, terwijl te laat starten de voordelen van vroege mobilisatie vermindert; 3) Personeel en middelen: Effectieve implementatie vereist getraind personeel en mogelijk extra middelen, zoals monitoringapparatuur, om patiënten veilig te mobiliseren.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Hoewel steeds meer bewijs voor de gunstige effecten van fysieke activiteit en uit-bed mobilisatie in de ziekenhuissetting, is de evidentie van (vroege) mobilisatie bij aSAB patiënten zeer beperkt. Over het algemeen blijkt uit de aanwezige literatuur geen bewijs voor negatieve effecten van mobilisatie, mogelijk zelfs een beschermend effect op vasospasmen en een hogere kans op een betere uitkomst op vaardigheids-/activiteitenniveau na 3 maanden. Er zijn echter onduidelijkheden wat betreft de definities van mobilisatie (oefenen in bed versus uit-bed activiteit), het tijdstip van mobilisatie en het begrip “medisch stabiel”. Dit werkt heterogeniteit van behandeling in de klinische praktijk in de hand. Op basis van de aanwezige evidentie van vroege mobilisatie (uit bed binnen 24 uur) bij patiënten na een ischemisch of hemorragisch infarct blijken geen voordelen, zelfs nadelige effecten en wordt een tijdsperiode gehanteerd van 24-48 uur na het event. Binnen deze tijdsperiode, wordt bij ernstiger aangedane patiënten (NIHSS-score >16) een frequenter en korter mobilisatieschema geadviseerd. Het lijkt gerechtvaardigd, in afwachting van nadere evidentie van de effecten van mobilisatie tussen 24-48u, aSAB patiënten op dezelfde manier te benaderen. Gestandaardiseerde protocollen met begripsdefinities en adviezen met betrekking tot monitoring van patiënten op hemodynamische en neurologische stabiliteit zijn nodig om heterogeniteit in de behandelpraktijk te minimaliseren.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

The timing for patient mobilization after an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH) varies between centers. The aim is to collect evidence on optimal timing in terms of risks and benefits of mobilization of patients after aSAH.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Recurrent bleeding

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early mobilization on recurrent bleeding when compared with late mobilization in adult aneurysmal SAH patients.

Sources: Karic, 2017; Yokobatake, 2022 |

2. Mortality

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early mobilization on mortality when compared with late mobilization in adult aneurysmal SAH patients.

Source: Karic, 2017 |

3. Vasospasms/secondary ischemia

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early mobilization on vasospasms/secondary ischemia when compared with late mobilization in adult aneurysmal SAH patients.

Sources: Foudhaili, 2023; Karic, 2017; Milovanovic, 2017; Yokobatake, 2022 |

4. Functional outcome

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early mobilization on functional outcome when compared with late mobilization in adult aneurysmal SAH patients.

Sources: Foudhaili, 2023; Yokobatake, 2022 |

5. Hydrocephalus

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early mobilization on hydrocephalus when compared with late mobilization in adult aneurysmal SAH patients.

Sources: Karic, 2017; Yokobatake, 2022 |

6. Length of stay

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early mobilization on length of stay when compared with late mobilization in adult aneurysmal SAH patients.

Sources: Foudhaili, 2023; Karic, 2017; Olkowski, 2015; Yokobatake, 2022 |

7. Complications, 8. Rehabilitation start

|

no GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of early mobilization on the outcomes complications and rehabilitation start compared with late mobilization in adults with an aneurysmal SAH.

Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Foudhaili (2023) performed a retrospective cohort study to determine the impact of early out-of-bed mobilization on functional outcome and cerebral vasospasms occurrence in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Aneurysmal SAH patients aged >18 years admitted to the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) of a hospital in Paris, France between 1 May 2018 and 30 November 2020 were included in the study. Exclusion criteria consisted of 1) admission for a recurrent aneurysmal SAH, 2) admission later than 48 hours after SAH onset, and 3) ICU length of stay shorter than 7 days. All patients admitted to the SICU for aneurysmal SAH were treated according to international guidelines (Connolly, 2012) and local protocols. In total, 179 patients were included that were either mobilized out of bed early (≤ day 4 after bleeding) or late (> day 4 after bleeding). If out-of-bed activities were not allowed, patients performed a 30-minute in-bed leg cycling session every weekday. The outcome measures functional independence at three months, cerebral vasospasm occurrence, and length of stay were reported. Additional study characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Karic (2017) conducted a prospective observational study to examine the effect of early mobilization on complications during the acute phase and within 90 days after aneurysmal SAH. All patients who were admitted to the neuro-intermediate ward of a hospital in Oslo, Norway following repair of a ruptured intracranial aneurysm between 2011 and 2012 were included. Exclusion criteria were 1) age < 18 years and 2) history of SAH, neurodegenerative disorder or traumatic brain injury. Patients admitted during 2011 received standard treatment in accordance with institutional standardized guidelines (Sorteberg, 2008). Patients admitted during 2012 underwent early mobilization and rehabilitation in addition to standard treatment. Early mobilization was conducted according to algorithm consisting of 7 steps. Step 0 included bed rest, with head elevation of 30°, and step 6 consisted of walking to the rest room and in the hallway. The outcome measures complications, cerebral vasospasms, recurrent bleeding, hydrocephalus, and mortality were assessed. Additional study characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Milovanovic (2017) conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to determine the time at which verticalization should be initiated after aneurysmal SAH, and subsequently develop a specific rehabilitation protocol for aneurysmal SAH patients. All subjects were patients in a Neurosurgery Clinic in Serbia between June 2013 and June 2015 that underwent surgery in the acute term of aneurysmal SAH. Exclusion criteria are not specified. Following surgery, participants were randomly assigned to either the early verticalization group or the late verticalization group. Participants in the early group started verticalization on days 2-5 post-bleeding, whereas participants in the late group started verticalization on day 12 post-bleeding. Additionally, both groups underwent the same early rehabilitation. The outcome measures complications and vasospasms/secondary ischemia were assessed at 1 and 3 months post-surgery. Additional study characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Olkowski (2015) performed a retrospective observational study to determine the effect of early mobilization on functional outcome and hospital length of stay in patients with aneurysmal SAH. SAH patients aged 18 years or older admitted to the neurosurgical ICU were included. Patients were excluded if they were admitted >14 days after SAH onset, care was withdrawn, or if SAH was determined to be caused by arteriovenous malformation or trauma. Patients admitted to the ICU between 1 January 2012 and 31 September 2012 with a diagnosis of aneurysmal SAH participated in the early mobilization program. A session of the program focused on positioning, education, functional training, and therapeutic exercise in the supine, sitting, standing, and walking positions. If possible, patients were transferred out of bed once daily and spent time sitting. Patients admitted to the ICU between 1 June 2009 and 31 December 2009 with a diagnosis of aneurysmal SAH did not participate in the early mobility program and composed the comparison group. The outcome measure hospital length of stay was reported. Additional study characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Yokobatake (2022) performed a retrospective cohort study to investigate the safety and efficacy of early mobilization in aneurysmal SAH patients. Patients with aneurysmal SAH admitted to a tertiary hospital in Japan between April 2015 and March 2019 were included in the study. Exclusion criteria consisted of 1) history of aneurysmal SAH, 2) severe diseases that were difficult to treat with surgery, 3) modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of ≥2 before the aneurysmal SAH onset, and 4) unexplained or venous SAH. A total of 111 aneurysmal SAH patients were included, of which 55 in the conventional group and 56 in the early rehabilitation group. Patients in the early rehabilitation group were mobilized early and started walking training as soon as possible. The outcome measures recurrent bleeding, functional independence, cerebral vasospasms, hydrocephalus, and length of stay were reported. Additional study characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies

Results

1. Recurrent bleeding

Two studies reported on recurrent bleeding.

Karic (2017) defined the outcome measure as rebleeding after aneurysm repair. None of the participants in neither the early rehabilitation group (n=94) nor the standard treatment group (n=77) experienced recurrent bleeding.

Yokobatake (2022) reported on rebleeding. 1.8% (1/56) of participants in the early rehabilitation group experienced recurrent bleeding, whereas none of the participants in the conventional treatment group (n=55) experienced rebleeding. Risk ratio was 2.95 (95%CI 0.12 to 70.82) in favor of conventional treatment.

2. Mortality

One study reported on the outcome measure mortality.

Karic (2017) reported on mortality within 90 days. 5.3% (5/94) of participants in the early rehabilitation group died within 90 days, compared to 5.2% (4/77) of participants in the standard treatment group. Risk ratio was 1.02 (95%CI 0.28 to 3.68) in favor of standard treatment. This difference was considered not clinically relevant.

3. Vasospasms/secondary ischemia

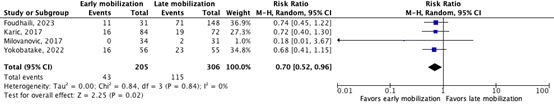

Four studies reported on the outcome measure vasospasms/secondary ischemia. Foudhaili (2023) reported on the outcome measure, defined as cerebral vasospasm occurrence meaning vessel narrowing for more than 50% associated with delayed cerebral ischemia and/or requiring angioplasty. Karic (2017) defined the outcome measure as radiological severe vasospasm meaning at least one vessel narrowing for 50% or more. Milovanovic (2017) reported on the incidence of vasospasms, based on clinical signs, at 12 days post-bleeding. Yokobatake (2022) reported on the incidence of cerebral vasospasms according to MRI or digital subtraction angiography (DSA).

Figure 1. shows cerebral vasospasm/secondary ischemia occurrence in 21.0% (43/205) of participants that were mobilized early compared to 37.6% (115/306) of participants that were mobilized late. The pooled risk ratio is 0.70 (95%CI 0.52 to 0.96) in favor of early mobilization, which was considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. The effect of early mobilization compared to late mobilization on vasospasms/secondary ischemia occurrence

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

4. Functional outcome

Two studies reported on the outcome measure functional outcome.

Foudhaili (2023) reported on functional independence at three months, defined as a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of < 3. The authors reported functional independence in 84% (26/31) of participants in the early out-of-bed mobilization group, and in 56% (83/148) of participants in the delayed out-of-bed mobilization group. Risk ratio was 1.50 (95%CI 1.21 to 1.85) in favor of early mobilization. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

Yokobatake (2022) reported on independence at three months, using mRS. The authors reported median (IQR) mRS scores at three months for both groups. The early rehabilitation group (n=56) had a median mRS score of 2 (0 to 4) compared to 3 (1 to 5) in the conventional treatment group (n=55).

5. Hydrocephalus

Two studies reported on the outcome measure hydrocephalus.

Karic (2017) reported the number of participants that required ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement. The authors reported that shunt placement was required in 22.3% (21/94) of participants in the early rehabilitation group and in 35.1% (27/77) of participants in the standard treatment group. Risk ratio was 0.64 (95%CI 0.39 to 1.03) in favor of early mobilization. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

Yokobatake (2022) also reported on the proportion of participants that required shunt surgery. 23.2% (13/56) of participants in the early rehabilitation group required shunt surgery compared to 38.2% (21/55) of participants in the conventional treatment group. Risk ratio was 0.61 (95%CI 0.34 to 1.09) in favor of early mobilization. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

6. Length of stay

Four studies reported on length of stay. Data could not be pooled due to the variety in reporting of the outcome measure.

Foudhaili (2023) reported on median (range) ICU length of stay. Participants in the early out-of-bed mobilization group had a median ICU length of stay of 13 (12 to 17) days compared to a median ICU length of stay of 15 (13 to 22) days in the delayed out-of-bed mobilization group.

Karic (2017) also reported on median (range) length of stay. Median length of stay was 13.9 (3 to 37) days in the early rehabilitation group and 14.5 (2 to 61) days in the standard treatment group.

Olkowski (2015) reported on mean (SD) hospital length of stay. Mean hospital length of stay was 12.8 (5.7) days in the early mobilization group and 15.7 (5.6) days in the control group. The mean difference was -2.90 (95%CI -5.23 to -0.57) in favor of early mobilization. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

Yokobatake (2022) reported on median (IQR) acute hospital length of stay. Participants in the early rehabilitation group had a median acute hospital length of stay of 26 (19 to 33) days compared to a median acute hospital length of stay of 39 (24 to 48) days in the conventional treatment group.

7. Complications, 8. Rehabilitation start

None of the studies reported on the outcome measures complications and rehabilitation start.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence of the literature was assessed per outcome measure, using the GRADE-methodology. The level of evidence started at low certainty because, besides one RCT, evidence was retrieved from observational studies.

1. Recurrent bleeding

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure recurrent bleeding was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations including selection of exposed and non-exposed patients from different populations, missing information about confounding assessment and analysis and outcome assessment (risk of bias: -1), and the low number of events and broad confidence interval of the individual study (imprecision: -2).

2. Mortality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations including selection of exposed and non-exposed patients from different populations, and missing information about confounding assessment and analysis (risk of bias: -1), and confidence interval overlap with both thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision: -2).

3. Vasospasms/secondary ischemia

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure vasospasms/secondary ischemia was downgraded by two levels to very low because of study limitations including missing information about allocation and no blinding, selection of exposed and non-exposed patients from different populations, missing information about confounding assessment and analysis and outcome assessment, and independent, unblinded outcome assessment (risk of bias: -1), and confidence interval overlap with threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision: -1).

4. Functional outcome

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure functional outcome was downgraded by two levels to very low because of study limitations including no confidence in the assessment of confounding factors, missing information about confounding assessment and problems with confounding analysis and independent, unblinded outcome assessment (risk of bias: -1), the inability to calculate effect measure and low number of included patients (imprecision: -1).

5. Hydrocephalus

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hydrocephalus was downgraded by two levels to very low because of study limitations including selection of exposed and non-exposed patients from different populations, missing information about confounding assessment and analysis and outcome assessment (risk of bias: -1), and confidence interval overlap with threshold for clinical relevance (imprecision: -1).

6. Length of stay

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure length of stay was downgraded by two levels to very low because of study limitations including selection of exposed and non-exposed patients from different populations, missing information about confounding assessment and analysis and outcome assessment, and independent, unblinded outcome assessment (risk of bias: -1), variety in reporting of the outcome measure and inability to calculate effect measure (imprecision: -1).

7. Complications, 8. Rehabilitation start

None of the studies reported on the outcome measures complications and rehabilitation start, and could therefore not be graded.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the benefits and risks of early mobilization compared to late mobilization for patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)?

| P: |

Patients (aged ≥18 years) with an aneurysmal SAH |

| I: |

Early mobilization |

| C: |

Late mobilization |

| O: | Functional outcome, mortality, recurrent bleeding, complications, vasospasms/secondary ischemia, hydrocephalus, length of stay, rehabilitation start |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered recurrent bleeding, mortality, and vasospasms/secondary ischemia as critical outcome measures for decision making, and functional outcome, hydrocephalus, length of stay and rehabilitation start as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined 25% (0.8 ≥ RR ≥ 1.25) for dichotomous outcomes and 0.5 SD for continuous outcomes as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2015 up to 17 October 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 26 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic reviews or meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials or other comparative studies (case-control or cohort studies);

- English full-text available;

- Studies according to PICO.

Eight studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, three studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five studies were included.

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- 1 - Bernhardt J, Churilov L, Ellery F, Collier J, Chamberlain J, Langhorne P, Lindley RI, Moodie M, Dewey H, Thrift AG, Donnan G; AVERT Collaboration Group. Prespecified dose-response analysis for A Very Early Rehabilitation Trial (AVERT). Neurology. 2016 Jun 7;86(23):2138-45. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002459. Epub 2016 Feb 17. Erratum in: Neurology. 2017 Jul 4;89(1):107. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004107. PMID: 26888985; PMCID: PMC4898313.

- 2 - Bernhardt J, Indredavik B, Dewey H, Langhorne P, Lindley R, Donnan G, Thrift A, Collier J. Mobilisation 'in bed' is not mobilisation. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;24(1):157-8; author reply 159. doi: 10.1159/000103626. Epub 2007 Jun 11. PMID: 17565211.

- 3 - Biernaskie J, Chernenko G, Corbett D. Efficacy of rehabilitative experience declines with time after focal ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2004 Feb 4;24(5):1245-54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3834-03.2004. PMID: 14762143; PMCID: PMC6793570.

- 4 - Brown CJ, Friedkin RJ, Inouye SK. Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 Aug;52(8):1263-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52354.x. PMID: 15271112.

- 5 - Connolly ES Jr, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, Derdeyn CP, Dion J, Higashida RT, Hoh BL, Kirkness CJ, Naidech AM, Ogilvy CS, Patel AB, Thompson BG, Vespa P; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Clinical Cardiology. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/american Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012 Jun;43(6):1711-37. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182587839. Epub 2012 May 3. PMID: 22556195.

- 6 - Cumming TB, Churilov L, Collier J, Donnan G, Ellery F, Dewey H, Langhorne P, Lindley RI, Moodie M, Thrift AG, Bernhardt J; AVERT Trial Collaboration group. Early mobilization and quality of life after stroke: Findings from AVERT. Neurology. 2019 Aug 13;93(7):e717-e728. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007937. Epub 2019 Jul 26. PMID: 31350296; PMCID: PMC6715509.

- 7 - Foudhaili A, Barthélémy R, Collet M, de Roquetaillade C, Kerever S, Vitiello D, Mebazaa A, Chousterman BG. Impact of Early Out-of-Bed Mobilization on Functional Outcome in Patients with Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Retrospective Cohort Study. World Neurosurg. 2023 Jul;175:e278-e287. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.03.073. Epub 2023 Mar 24. PMID: 36966907.

- 8 - Indredavik B, Bakke F, Slordahl SA, Rokseth R, Hâheim LL. Treatment in a combined acute and rehabilitation stroke unit: which aspects are most important? Stroke. 1999 May;30(5):917-23. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.5.917. PMID: 10229720.

- 9 - Karic T, Røe C, Nordenmark TH, Becker F, Sorteberg W, Sorteberg A. Effect of early mobilization and rehabilitation on complications in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2017 Feb;126(2):518-526. doi: 10.3171/2015.12.JNS151744. Epub 2016 Apr 8. PMID: 27058204.

- 10 - Langhorne P, Collier JM, Bate PJ, Thuy MN, Bernhardt J. Very early versus delayed mobilisation after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Oct 16;10(10):CD006187. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006187.pub3. PMID: 30321906; PMCID: PMC6517132.

- 11 - Milovanovic A, Grujicic D, Bogosavljevic V, Jokovic M, Mujovic N, Markovic IP. Efficacy of Early Rehabilitation After Surgical Repair of Acute Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Outcomes After Verticalization on Days 2-5 Versus Day 12 Post-Bleeding. Turk Neurosurg. 2017;27(6):867-873. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.17711-16.1. PMID: 27593842.

- 12 - Musicco M, Emberti L, Nappi G, Caltagirone C; Italian Multicenter Study on Outcomes of Rehabilitation of Neurological Patients. Early and long-term outcome of rehabilitation in stroke patients: the role of patient characteristics, time of initiation, and duration of interventions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003 Apr;84(4):551-8. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50084. PMID: 12690594.

- 13 - Olkowski, Brian F.; Binning, Mandy J.; Sanfillippo, Geri; Arcaro, Melissa L.; Slotnick, Laurie E.; Veznedaroglu, Erol; Liebman, Kenneth M.; Warren, Amy E.. Early Mobilization in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Accelerates Recovery and Reduces Length of Stay. Journal of Acute Care Physical Therapy 6(2):p 47-55, August 2015. | DOI: 10.1097/JAT.0000000000000008.

- 14 - Sorteberg W, Slettebø H, Eide PK, Stubhaug A, Sorteberg A. Surgical treatment of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage in the presence of 24-h endovascular availability: management and results. Br J Neurosurg. 2008 Feb;22(1):53-62. doi: 10.1080/02688690701593553. PMID: 17852110.

- 15 - Yokobatake K, Ohta T, Kitaoka H, Nishimura S, Kashima K, Yasuoka M, Nishi K, Shigeshima K. Safety of early rehabilitation in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A retrospective cohort study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2022 Nov;31(11):106751. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2022.106751. Epub 2022 Sep 23. PMID: 36162375.

- 16 - Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Gur-Yaish N, Tonkikh O, Sinoff G. Hospital-associated functional decline: the role of hospitalization processes beyond individual risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015 Jan;63(1):55-62. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13193. PMID: 25597557.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for RCTs and observational studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Foudhaili, 2023 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: Surgical intensive care unit (SICU) of a hospital in Paris, France

Funding and conflicts of interest: Potential conflicts of interest are declared. No funding source has been reported. |

Inclusion criteria: Aneurysmal SAH patients aged >18 years admitted to the French hospital between 1 May 2018 and 30 November 2020.

Exclusion criteria: - Admission for a recurrent aneurysmal SAH - Admission later than 48 hours after SAH onset - ICU length of stay shorter than 7 days

N total at baseline: Intervention: 31 Control: 148

Important prognostic factors2: Median age (IQR): I: 56 (47-61) years C: 52 (43-61) years

Sex (% male): I: 35.5% C: 30.4%

Groups comparable at baseline? More people with WFNS grade 3-5 in the delayed mobilization group. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Early out-of-bed mobilization: mobilization out of bed ≤ day 4 after bleeding. If mobilization is allowed but not out-of-bed, patients have a 30-minute in-bed leg cycling session every weekday.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Delayed out-of-bed mobilization: no mobilization ≤ day 4 after bleeding. If mobilization is allowed but not out-of-bed, patients have a 30-minute in-bed leg cycling session every weekday.

|

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Functional outcome mRS score < 3 I: 26/31 (84%) C: 83/148 (56%) RR = 1.50 (95%CI 1.21 to 1.85)

Vasospasms Vessel narrowing ≥50% I: 11/31(35.5%) C: 71/148 (48.0%) RR = 0.74 (95%CI 0.45 to 1.22)

Length of stay (LOS) Median (range) ICU LOS I: 13 (12 to 17) days C: 15 (13 to 22) days |

None |

|

Karic, 2017 |

Type of study: Prospective observational study

Setting and country: Neuro-intermediate ward of a hospital in Oslo, Norway

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No funding source has been reported. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients who were admitted to the Norwegian hospital following repair of a ruptured intracranial aneurysm between 2011 and 2012.

Exclusion criteria: - Age < 18 years - History of SAH, neurodegenerative disorder or traumatic brain injury

N total at baseline: Intervention: 94 Control: 77

Important prognostic factors2: Median age (range): I: 57 (25-81) years C: 54 (25-79) years

Sex (% male): I: 30% C: 36%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Early rehabilitation according to a stepwise mobilization algorithm (step 0-6) plus standard treatment. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Historical cohort receiving standard treatment in accordance with institutional guidelines. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 10 participants Control: 5 participants Reasons: because of bleeding prior to hospitalization and development of cerebral vasospasm upon arrival to the hospital.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported, except loss to follow-up as described above. |

Mortality Mortality within 90 days I: 5/94 (5.3%) C: 4/77 (5.2%) RR = 1.02 (95%CI 0.28 to 3.68)

Recurrent bleeding Rebleeding after aneurysm repair I: 0/94 C: 0/77

Vasospasms ≥1 vessel narrowing ≥50% I: 16/84 (19.0%) C: 19/72 (26.4%) RR = 0.72 (95%CI 0.40 to 1.30)

Hydrocephalus Number of participants that required shunt placement I: 21/94 (22.3%) C: 27/77 (35.1%) RR = 0.64 (95%CI 0.39 to 1.03)

Length of stay (LOS) Median (range) LOS I: 13.9 (3 to 37) days C: 14.5 (2 to 61) days |

None |

|

Milovanovic, 2017 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Neurosurgery clinic in Serbia

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not specified. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients admitted to the neurosurgery clinic between June 2013 and June 2015 that underwent surgery in the acute term of aneurysmal SAH.

Exclusion criteria: Not specified.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 34 Control: 31

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age ± SD: I: 51.8 ± 10.1 years C: 51.9 ± 8.2 years

Sex (% male): I: 32.4% C: 32.3%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Early rehabilitation with initiation of verticalization on days 2-5 post-bleeding. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Early rehabilitation with initiation of verticalization on day 12 post-bleeding |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Vasospasms Based on clinical signs, 12 days post-bleeding I: 0/34 C: 2/31 (6.5%) RR = 0.18 (95%CI 0.01 to 3.67) |

None |

|

Olkowski, 2015 |

Type of study: Retrospective observational study

Setting and country: Neurosurgical ICU in the USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not specified. |

Inclusion criteria: SAH patients aged 18 years or older admitted to the neurosurgical ICU.

Exclusion criteria: - Admission >14 days after SAH onset - Care withdrawal - SAH caused by arteriovenous malformation or trauma.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 55 Control: 38

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age ± SD: I: 55.6 ± 15.5 years C: 51.6 ± 11.2 years

Sex (% male): I: 36.4% C: 26.3%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Early mobilization program sessions (30-60 minutes). |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Historical control group including patients who did not participate in a formal early mobility program. |

Length of follow-up: Unknown

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Length of stay (LOS) Mean (SD) hospital LOS I: 12.8 (5.7) days C: 15.7 (5.6) days MD = -2.90 (95%CI -5.23 to -0.57) |

None |

|

Yokobatake, 2022 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: Tertiary hospital in Japan

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No funding source. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with aneurysmal SAH admitted to the tertiary hospital between April 2015 and March 2019. Exclusion criteria: - History of aneurysmal SAH - Severe diseases that were difficult to treat with surgery - mRS score of ≥2 before the aneurysmal SAH onset - Unexplained or venous SAH

N total at baseline: Intervention: 56 Control: 55

Important prognostic factors2: Median age (IQR): I: 70 (59-80) years C: 66 (56-80) years

Sex (% male): I: 29% C: 31%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Early rehabilitation group according to a program. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Conventional treatment group. |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: None

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Functional outcome Median (IQR) mRS score I: 2 (0 to 4) C: 3 (1 to 5)

Recurrent bleeding I: 1/56 (1.8%) C: 0/55 RR = 2.95 (95%CI 0.12 to 70.82)

Vasospasms According to MRI or DSA I: 16/56 (28.6%) C: 23/55 (41.8%) RR = 0.68 (95%CI 0.41 to 1.15)

Hydrocephalus Patients that required shunt surgery I: 13/56 (23.2%) C: 21/55 (38.2%) RR = 0.61 (95%CI 0.34 to 1.09)

Length of stay (LOS) Median (IQR) acute hospital LOS I: 26 (19 to 33) days C: 39 (24 to 48) days |

None |

Risk of bias tabellen

RCTs

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Milovanovic, 2017 |

No information |

No information |

Definitely no

Reason: No blinding was performed. |

Definitely yes

Reason: None of the participants were lost to follow-up. |

Probably yes

Reason: No registration or protocol available, but no reason to doubt about selective outcome reporting. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Not reported. |

HIGH |

Cohort studies

|

Author, year |

Selection of participants

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population?

|

Exposure

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure? |

Outcome of interest

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study? |

Confounding-assessment

Can we be confident in the assessment of confounding factors? |

Confounding-analysis

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these confounding variables? |

Assessment of outcome

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome? |

Follow up

Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? In particular, was outcome data complete or imputed? |

Co-interventions

Were co-interventions similar between groups? |

Overall Risk of bias |

|

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Low, Some concerns, High |

|

|

Foudhaili, 2023 |

Definitely yes

Reason: All consecutive aSAH patients admitted to the hospital between 1 May 2018 and 30 November 2020 were included. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Exposure information is obtained from medical records. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Outcome of interest was not present at start of the study. |

Probably no

Reason: Chart review. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Matching was performed. |

Probably yes

Reason: All data was retrieved from medical records, or consultations performed during the 3-month follow-up visit. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent. |

Definitely yes

Reason: If out-of-bed activities were not possible, patients had a 30-minute in-bed leg cycling session every weekday. |

Some concerns |

|

Karic, 2017 |

Probably no

Reason: Exposed and unexposed patients were selected over a different time frame. |

Probably yes

Reason: Patients admitted during 2011 received standard treatment according to guidelines. Patients admitted during 2012 underwent early mobilization. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Fifteen patients were excluded from the analysis because they had one of the outcomes of interest upon arrival to the hospital/at the start. |

No information |

No information |

No information |

Definitely yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent. |

Probably yes

Reason: Nothing is reported about co-interventions. |

HIGH |

|

Olkowski, 2015 |

Probably no

Reason: Exposed and unexposed patients were selected over a different time frame. |

Probably yes

Reason: Patients admitted during 2009 did not participate in an early mobility program, whereas patients admitted during 2012 did. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Not applicable to the outcome measure length of stay. |

Probably no

Reason: Chart review. |

No information |

No information |

No information |

Probably yes

Reason: Nothing is reported about co-interventions. |

HIGH |

|

Yokobatake, 2022 |

Definitely yes

Reason: A consecutive series of patients admitted to the hospital with aSAH between April 2015 and March 2019 were included. |

Probably yes

Reason: The early rehabilitation program was introduced from April 2017. Patients admitted to the hospital before April 2017 were not exposed, whereas patients admitted after April 2017 were exposed. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Outcome of interest was not present at start of the study. |

No information |

Definitely no

Reason: Adjustment for a minority of plausible exploratory variables based on clinical relevance from baseline characteristics. |

Probably no

Reason: Independent assessment unblinded. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent. |

Probably yes

Reason: Nothing is reported about co-interventions. |

HIGH |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Karic T, Røe C, Nordenmark TH, Becker F, Sorteberg A. Impact of early mobilization and rehabilitation on global functional outcome one year after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Rehabil Med. 2016 Oct 5;48(8):676-682. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2121. PMID: 27494170. |

Same study population as Karic (2017), but this study does not present raw data |

|

Yang X, Cao L, Zhang T, Qu X, Chen W, Cheng W, Qi M, Wang N, Song W, Wang N. More is less: Effect of ICF-based early progressive mobilization on severe aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in the NICU. Front Neurol. 2022 Dec 14;13:951071. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.951071. PMID: 36588882; PMCID: PMC9794623. |

Wrong population (includes non-aneurysmatic SAH patients) |

|

Young B, Moyer M, Pino W, Kung D, Zager E, Kumar MA. Safety and Feasibility of Early Mobilization in Patients with Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and External Ventricular Drain. Neurocrit Care. 2019 Aug;31(1):88-96. doi: 10.1007/s12028-019-00670-2. PMID: 30659467. |

Wrong intervention and comparison (unclear what was exactly done) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 27-08-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 19-08-2025

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire cluster ingesteld. Dit cluster bestaat uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante organisaties die betrekking hebben op de zorg voor patiënten met cerebrovasculaire ziekten.

Het cluster Cerebrovasculaire ziekten bestaat uit meerdere richtlijnen, zie hier voor de actuele clusterindeling. De stuurgroep bewaakt het proces van modulair onderhoud binnen het cluster. De expertisegroepsleden worden indien nodig gevraagd om hun expertise in te zetten voor een specifieke richtlijnmodule. Het cluster Cerebrovasculaire ziekten bestaat uit de volgende personen:

Clusterstuurgroep

- Dhr. dr. M.D.I. (Mervyn) Vergouwen (voorzitter), neuroloog, UMC Utrecht, namens de NVN

- Dhr. dr. I.R. (Ido) van den Wijngaard, neuroloog, Leiden UMC, namens de NVN

- Dhr. prof. dr. B. (Bob) Roozenbeek, neuroloog, Erasmus MC, namens de NVN

- Dhr. dr. R. (René) van den Berg, (interventie neuro-) radioloog, Amsterdam UMC, namens de NVvR

- Dhr. M.A.C. (Michiel) Lindhout, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, namens Harteraad

- Mevr. dr. M. (Margriet) van der Werf, revalidatiearts, Rijndam, namens de VRA

- Dhr. prof. dr. H.D. (Jeroen) Boogaarts, neurochirurg, Radboud UMC, namens de NVvN

Clusterexpertisegroep

- Dhr. prof. dr. W.H. (Werner) Mess, neuroloog, Maastricht UMC, namens de NVN

- Dhr. prof. dr. B. (Bart) van der Zwan, neurochirurg, UMC Utrecht, namens de NVvN

- Dhr. prof. dr. G.J. (Gert-Jan) de Borst, vaatchirurg, UMC Utrecht, namens de NVvH

- Dhr. dr. J.A.H.R. (Jurgen) Claassen, klinisch geriater, Radboud UMC, namens de NVKG

- Mevr. prof. dr. ir. Y.M.C. (Yvonne) Henskens, klinisch chemicus, namens de NVKC

- Mevr. dr. M.J.J. (Marleen) Gerritsen, klinisch neuropsycholoog, namens het NIP

- Dhr. I. (Ivar) Spin, fysiotherapeut, namens de KNGF

- Dhr. dr. R.H. (Raymond) Wimmers, namens de Hartstichting

- Dhr. prof. dr. W. (Wim) van Zwam, radioloog, Maastricht UMC, namens de NVvR

- Dhr. dr. T.H. (Rob) Lo, radioloog, UMC Utrecht, namens de NVvR

- Dhr. dr. B.J. (Berto) Bouma, cardioloog, Amsterdam UMC, namens de NVVC

- Mevr. dr. F.H.M. (Fianne) Spaander, neuroloog, namens de NVN

- Mevr. M. (Mathilde) Nijkeuter, internist, UMC Utrecht, namens de NIV

- Dhr. T.T. (Thomas) van Sloten, internist, Maastricht MC, namens de NIV

- Mevr. dr. C.W.E. (Astrid) Hoedemaekers, intensivist, Radboud UMC, namens de NVIC

- Dhr. prof. dr. G.J.E. (Gabriel) Rinkel, neuroloog, UMC Utrecht, namens de NVN

- Mevr. prof. dr. Y.M. (Ynte) Ruigrok, neuroloog, UMC Utrecht, namens de NVN

- Mevr. J. (Jamie) Manuputty, neuroloog, Elisabeth-TweeSteden Ziekenhuis, namens de NVN

- Mevr. dr. F. (Femke) Nouwens, logopediste, namens de NVLF

- Mevr. C.C. (Carola) Deurwaarder, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, namens Hersenaneurysma Patiëntenplatform

- Mevr. dr. M.J.E. (Marlies) Kempers, klinisch geneticus, Radboud UMC, namens de VKGN

- Mevr. S. (Sabine) van Erp, ergotherapeut, namens EN

- Dhr. prof. dr. C.G.M. (Carel) Meskers, revalidatiearts, Amsterdam UMC, namens de VRA

Met ondersteuning van

- Mevr. M.M. (Marja) Molag, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mevr. L.C. (Laura) van Wijngaarden, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle clusterstuurgroepleden en actief betrokken expertisegroepsleden (fungerend als schrijver en/of meelezer bij tenminste één van de geprioriteerde richtlijnmodules) hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een richtlijnmodule worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de projectleider doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase. Een overzicht van de belangen van de clusterleden en betrokken expertisegroepsleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Clusterstuurgroep

|

Clusterlid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Bob Roozenbeek |

Neuroloog, Erasmus MC |

Voorzitter richtlijnwerkgroep ‘Herseninfarct en hersenbloeding’ namens de NVN |

Coördinator van klinische onderzoeksprojecten op gebied van acute beroertezorg gesubsidieerd door Stichting BeterKeten, Sitchting Theia (Zilveren Kruis), ZonMw en Hartstichting. Deze subsidies werden betaald aan werkgever Erasmus MC. |

Geen restricties |

|

Ido van den Wijngaard |

Neuroloog, Haaglanden MC |

Commissielid NVN richtlijn |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Jeroen Boogaarts |

Neurochirurg, Radboud UMC |

Voorzitter Stichting Kwaliteitsbevordering Neurochirurgie. |

Subsidie van hartstichting en ZonMw binnen CONTRAST 2. Hartstichting; registratie SAB patienten (CONTRAST 2, WP6). ZonMw; intracerebrale bloedingen trial (DIST). Consultant voor stryker neurovascular, inkomsten worden aan de afdeling Neurochirurgie van het Radboudumc betaald. |

Geen restricties |

|

Margriet van der Werf |

Revalidatiearts, Rijndam Revalidatie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Mervyn Vergouwen |

Neuroloog, UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

CSL Behring: deelname aan advisory board meeting, betaling aan UMC Utrecht Bayer: onderzoeksgeld voor Investigator Initiated Research, betaling aan UMC Utrecht |

Geen restricties |

|

Michiel Lindhout |

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Hersenletsel.nl |

Bestuurder patiëntenperspectief Kennisnetwerk CVA Nederland (onbezoldigd) |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

René van den Berg |

(Interventie-) Neuroradioloog, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

Clusterexpertisegroep

Richtlijn Subarachnoïdale bloeding: Module 1 ‘Mobiliseren na een SAB’

|

Clusterlid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Carel Meskers |

Revalidatiearts en hoogleraar, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Health Holland; Care4Muscle, projectleider DCVA; Contrast 2.0, projectleider |

Geen restricties |

|

Margriet van der Werf |

Revalidatiearts, Rijndam Revalidatie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

Richtlijn Subarachnoïdale bloeding: Module 2 ‘Cognitieve screening na een SAB’

|

Clusterlid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Margriet van der Werf |

Revalidatiearts, Rijndam Revalidatie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Marleen Gerritsen |

Klinisch neuropsycholoog, Deventer Ziekenhuis |

Gastvrijheidsovereenkomst UMCG |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

Richtlijn Subarachnoïdale bloeding: Module 3 ‘Behandeling gebarsten aneurysma – geavanceerde technieken’

|

Clusterlid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Mervyn Vergouwen |

Neuroloog, UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

CSL Behring: deelname aan advisory board meeting, betaling aan UMC Utrecht Bayer: onderzoeksgeld voor Investigator Initiated Research, betaling aan UMC Utrecht |

Geen restricties |

|

René van den Berg |

(Interventie-) Neuroradioloog, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door deelname van relevante patiëntenorganisaties aan de need-for-update en/of prioritering. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijnmodule is tevens ter commentaar voorgelegd aan alle relevante patiëntenorganisaties in de stuur- en expertisegroep (zie ‘Samenstelling cluster’ onder ‘Verantwoording’) en aan alle patiëntenorganisaties die niet deelnemen aan de stuur- en expertisegroep, maar wel hebben deelgenomen aan de need-for-update (zie ‘Need-for-update’ onder ‘Verantwoording’). De eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijnmodule is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd om te beoordelen of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

De kwalitatieve raming volgt na de commentaarfase.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 3.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Need-for-update, prioritering en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de need-for-update fase (februari 2023) inventariseerde het cluster de geldigheid van de richtlijnmodules binnen het cluster. Naast de partijen die deelnemen aan de stuur- en expertisegroep zijn hier ook andere stakeholders voor benaderd. Per richtlijnmodule is aangegeven of deze geldig is, herzien moet worden, kan vervallen of moet worden samengevoegd. Ook was er de mogelijkheid om nieuwe onderwerpen aan te dragen die aansluiten bij één (of meerdere) richtlijn(en) behorend tot het cluster. De richtlijnmodules waarbij door één of meerdere partijen werd aangegeven herzien te worden, werden doorgezet naar de prioriteringsronde. Ook suggesties voor nieuwe richtlijnmodules werden doorgezet naar de prioriteringsronde. Afgevaardigden vanuit de partijen in de stuur- en expertisegroep werden gevraagd om te prioriteren (zie ‘Samenstelling cluster’ onder ‘Verantwoording’). Hiervoor werd de RE-weighted Priority-Setting (REPS) – tool gebruikt. De uitkomsten (ranklijst) werd gebruikt als uitgangspunt voor de discussie. Voor de geprioriteerde richtlijnmodules zijn door de het cluster concept-uitgangsvragen herzien of opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde het cluster welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. Het cluster waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde het cluster tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd indien mogelijk gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding). GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

Gradaties voor de kwaliteit van wetenschappelijk bewijs

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in een richtlijnmodule volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door het cluster wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. Het cluster heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

Sterkte van de aanbevelingen

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

Bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de richtlijnmodule Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd voorgelegd aan alle partijen die benaderd zijn voor de need-for-update fase. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met het cluster. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door het cluster. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd ter autorisatie of goedkeuring voorgelegd aan de partijen die beschreven staan bij ‘Initiatief en autorisatie’ onder ‘Verantwoording’.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Algemene informatie

|

Cluster/richtlijn: Cluster cerebrovasculaire ziekten Module 1 |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag/modules: Vanaf wanneer kan een patiënt met een aneurysmatische SAB veilig gemobiliseerd worden? |

|

|

Database(s): Embase.com, Ovid/Medline |

Datum: 17 oktober 2023 |

|

Periode: vanaf 2015 |

Talen: geen restrictie |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Alies van der Wal en Esther van der Bijl |

Rayyan review: https://rayyan.ai/reviews/811621 |

|

BMI-zoekblokken: voor verschillende opdrachten wordt (deels) gebruik gemaakt van de zoekblokken van BMI-Online https://blocks.bmi-online.nl/ Bij gebruikmaking van een volledig zoekblok zal naar de betreffende link op de website worden verwezen. |

|

|

Toelichting: Voor deze vraag is gezocht op de elementen:

→ De sleutelartikelen PMID7058204, PMID27494170 en PMID36162375 worden gevonden met deze search. |

|

|

Te gebruiken voor richtlijntekst: In de databases Embase.com en Ovid/Medline is op 17 oktober 2023 systematisch gezocht naar systematische reviews, RCTs en observationele studies over veilig (vroegtijdig) mobiliseren van patiënten met een aneurysmatische SAB. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 26 unieke treffers op. |

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

EMBASE |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SR |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

RCT |

11 |

6 |

13 |

|

Observationeel |

11 |

10 |

11 |

|

Totaal |

24 |

16 |

26* |

*in Rayyan

Zoekstrategie

Embase.com

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#1 |

('subarachnoid hemorrhage'/exp OR ((subarachnoid* NEAR/4 (hemorrhag* OR haemorrhag* OR bleed* OR blood OR hematoma* OR haematoma*)):ti,ab,kw)) AND ('aneurysm'/exp OR aneurysm*:ti,ab,kw OR aneurism*:ti,ab,kw) OR (((subarachnoid* OR sah OR sab) NEAR/4 (aneurysm* OR aneurism*)):ti,ab,kw) OR asah:ti,ab,kw |

28577 |

|

#2 |

('mobilization'/exp OR 'rehabilitation'/exp/mj OR 'walking'/exp) AND early:ti,ab,kw OR (((mobilizat* OR mobilisat* OR ambulat* OR gait OR walk* OR rehabilitat* OR neurorehabilitat* OR revalidat* OR 'out of bed') NEAR/4 early):ti,ab,kw) |

44286 |

|

#3 |

#1 AND #2 |

70 |

|

#4 |

#3 NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal'/exp OR 'animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

50 |

|

#5 |

#4 AND [2015-2023]/py |

34 |

|

#6 |

'meta analysis'/exp OR 'meta analysis (topic)'/exp OR metaanaly*:ti,ab OR 'meta analy*':ti,ab OR metanaly*:ti,ab OR 'systematic review'/de OR 'cochrane database of systematic reviews'/jt OR prisma:ti,ab OR prospero:ti,ab OR (((systemati* OR scoping OR umbrella OR 'structured literature') NEAR/3 (review* OR overview*)):ti,ab) OR ((systemic* NEAR/1 review*):ti,ab) OR (((systemati* OR literature OR database* OR 'data base*') NEAR/10 search*):ti,ab) OR (((structured OR comprehensive* OR systemic*) NEAR/3 search*):ti,ab) OR (((literature NEAR/3 review*):ti,ab) AND (search*:ti,ab OR database*:ti,ab OR 'data base*':ti,ab)) OR (('data extraction':ti,ab OR 'data source*':ti,ab) AND 'study selection':ti,ab) OR ('search strategy':ti,ab AND 'selection criteria':ti,ab) OR ('data source*':ti,ab AND 'data synthesis':ti,ab) OR medline:ab OR pubmed:ab OR embase:ab OR cochrane:ab OR (((critical OR rapid) NEAR/2 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ti) OR ((((critical* OR rapid*) NEAR/3 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ab) AND (search*:ab OR database*:ab OR 'data base*':ab)) OR metasynthes*:ti,ab OR 'meta synthes*':ti,ab |

969432 |

|

#7 |

'clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR 'prospective study'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti |

3892638 |

|

#8 |