Preoperatieve immunonutritie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het effect van preoperatieve immunonutritie in goed gevoede volwassen patiënten die chirurgische ingrepen ondergaan ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI)?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg het gebruik van orale immunonutritie voorafgaand aan een operatie bij goed gevoede patiënten die een electieve gastro-intestinale operatie ondergaan ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties.

Uit de literatuur blijkt voortzetten van immunonutritie na operatie geen voordeel te geven en wordt dan ook niet aanbevolen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De systematische literatuur analyse en meta-analyse van Cadili (2023) onderzocht het effect van preoperatieve immunonutritie in goed gevoede patiënten op het ontstaan van postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI). Er werd bewijs met redelijke zekerheid gevonden dat het risico op POWI vermindert met de inname van immunonutritie in vergelijking met geen additionele voeding peroperatief (RR 0.68; 95% CI 0.53 – 0.87).

Voor de secundaire uitkomstmaten (mortaliteit, pneumonie en urineweginfectie) werd er geen significant verschil gevonden tussen het gebruik van immunonutritie en normaal dieet. Bijwerkingen van de behandeling werden zeer slecht gerapporteerd in de individuele studies. Slechts vijf studies rapporteerden dit, waarvan drie studies bij enkele patiënten gastro-intestinale klachten rapporteerden.

(Inter)nationale richtlijnen

In de internationale richtlijnen is er weinig aandacht voor immunonutritie in goed gevoede patiënten.

De WHO-richtlijn uit 2018 adviseert om orale of enterale meervoudig met voedingsstoffen verrijkte nutritionele formules te overwegen om POWI te voorkomen bij patiënten met ondergewicht die grote chirurgische ingrepen ondergaan. De NICE richtlijn adviseert perioperatieve orale immunonutritie voor chirurgische patiënten die in staat zijn om veilig te slikken en ondervoed zijn (CG32).

De richtlijn van de European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) adviseert perioperatieve ‘nutritional support’ in ondervoede patiënten en patiënten met een risico om ondervoeding te ontwikkelen. Ook adviseren zij te starten met ‘nutritional support’ bij patiënten die minimaal vijf dagen niet in staat zullen zijn om te eten, of bij patiënten waarbij zeven dagen de intake minder dan 50% van de aanbevolen hoeveelheid zal zijn.

De richtlijn Perioperatief voedingsbeleid (2018, NVA/NVvH) adviseert bij patiënten met een ernstige ondervoeding* die een majeure ingreep ondergaan om een preoperatieve adequate dieetbehandeling toe te passen en zo nodig een voedingsinterventie gedurende tenminste 7 tot 14 dagen, ook al moet de (oncologische) ingreep worden uitgesteld. Preoperatief gebruik van immunonutritie of antioxidanten wordt voor geen enkele patiënt aanbevolen. Deze richtlijn heeft echter SSI niet als eindpunt meegenomen maar gekeken naar overall (infectieuze) complicaties.

* Voor de definitie van ondervoeding wordt verwezen naar de richtlijn ondervoeding.

Waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt

Bij het voorschrijven van immunonutritie is het belangrijk om de patiënt het belang van het verbeteren van de voedingsstatus uit te leggen, met als doel om postoperatieve wondinfecties te voorkomen. Het is belangrijk om helder uit te leggen aan de patiënt wat immunonutritie inhoudt en welke voedingsbehoeften daarbij relevant zijn. Belangrijk is dat de patiënt zich begrepen voelt en dat de zorgverlener samenwerkt om haalbare voedingskeuzes te vinden die passen bij de waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt.

Over het algemeen wordt immunonutritie goed getolereerd. Sommige immunonutritie wordt geproduceerd op basis van melkproducten, waardoor deze ongeschikt kunnen zijn voor patiënten met een koemelkallergie of lactose-intolerantie. Patiënten kunnen bepaalde individuele waarden en ideeën over voeding hebben, die mee kunnen spelen in de afweging van het nemen van immunonutritie versus het risico op perioperatieve complicaties.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er zijn kosten verbonden aan immunonutritie in goed gevoede patiënten. Er zijn enkele studies naar de kosteneffectiviteit van immunonutritie in goed gevoede patiënten bij gastro-intestinale chirurgie, waarbij initieel een kostenverhoging zal plaatsvinden, maar uiteindelijk resulteert in kostenbesparingen door de afname van POWI (Senkal 1999, Braga 2005, Mauskopf 2012, Chevrou-Severac 2014, Reis 2016,)

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er zijn geen kwantitatieve of kwalitatieve studies bekend naar de aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie van immunonutritie bij goed gevoede patiënten die een chirurgische ingreep ondergaan. Echter, in de praktijk wordt drinkvoeding bij grote abdominale chirurgie reeds toegepast in de perioperatieve periode.

Mogelijke belemmeringen voor implementatie kunnen gelegen zijn in de beschikbaarheid van de immunonutritie.

Rationale van de aanbeveling

Er wordt met redelijke bewijskracht gevonden dat de toediening van orale immunonutritie voorafgaand aan een operatie in goed gevoede patiënten resulteert in een vermindering van het aantal wondinfecties. Uit meerdere studies blijkt dat dit mogelijk ook kosteneffectief is. Uit de literatuur blijken geen nadelige gevolgen voor de patiënt bij het gebruik van immunonutritie. Het onderzoek richt zich vooral op electieve en gastro-intestinale chirurgie. Toekomstig onderzoek moet zich richten op chirurgie anders dan gastro-intestinale chirurgie en de optimale dosering van de immunonutritie.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Preoperatieve immunonutritie, een benadering waarbij specifieke voedingsstoffen worden ingezet om het immuunsysteem te optimaliseren, komt steeds meer naar voren als een belangrijk aandachtspunt in de chirurgische praktijk. Onderzoek suggereert dat de voedingstoestand voorafgaand aan een operatie invloed heeft op het verloop van het herstel en de vatbaarheid voor infecties.

Preoperatieve immunonutritie kan daarmee ingezet worden als een strategie om postoperatieve wondinfecties te verminderen en zo de chirurgische uitkomsten te verbeteren. Het is echter onduidelijk wat het effect is van preoperatieve immunonutritie in goed gevoede volwassen patiënten die chirurgische ingrepen ondergaan ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI).

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Oral enhanced nutritional support versus standard care

|

Moderate GRADE |

Oral enhanced nutritional support likely results in little to no difference in surgical site infections when compared with no additional preoperative nutritional support in well-nourished adult patients, undergoing surgical procedures. |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Oral enhanced nutritional support likely results in little to no difference in mortality when compared with no additional preoperative nutritional support in well-nourished adult patients, undergoing surgical procedures. |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Oral enhanced nutritional support likely results in little to no difference in pneumonia when compared with no additional preoperative nutritional support in well-nourished adult patients, undergoing surgical procedures. |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Oral enhanced nutritional support likely results in little to no difference in urinary tract infections when compared with no additional preoperative nutritional support in well-nourished adult patients, undergoing surgical procedures. |

|

Moderate GRADE |

De evidence is zeer onzeker over het effect van Immunonutritie op adverse events in vergelijking met een standaard dieet, in goed gevoede patiënten die een operatie ondergaan. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Thirteen randomized controlled trials were included in the systematic review by Cadili et al. See the detailed PRISMA flow diagram for updating systematic reviews . Cadili et al. also included non-randomized studies, that we did not include for this guideline. Study characteristics of the included RCTs are summarized in Study characteristics. The risk of bias assessment is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Type of surgery and ONS

Seven studies investigated gastrointestinal surgery (n = 1083), three hepatobiliary surgery (n = 162), and two studies evaluated cardiac surgery (n = 103). Seven studies used a type of oral nutritional support including omega-3 fatty acids, arginine, and nucleotides. The lengths of treatment varied from two days to over 30 days, with some continuing nutritional support after surgery.

Study quality

Risk of bias was assessed using the ROB2-tool. In total four studies (n = 256) had low risk of bias, eight studies (n= 1024) had some concerns, and one study (n = 1347) had high risk of bias (risk of bias tables).

Primary outcome

Surgical Site infection

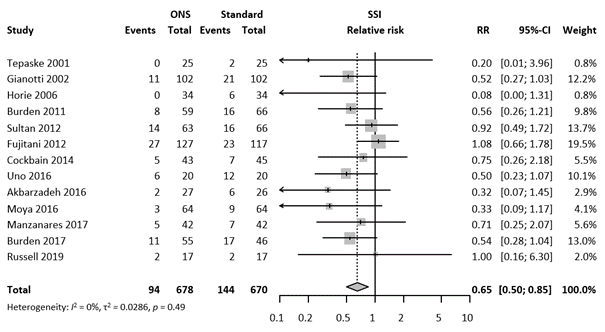

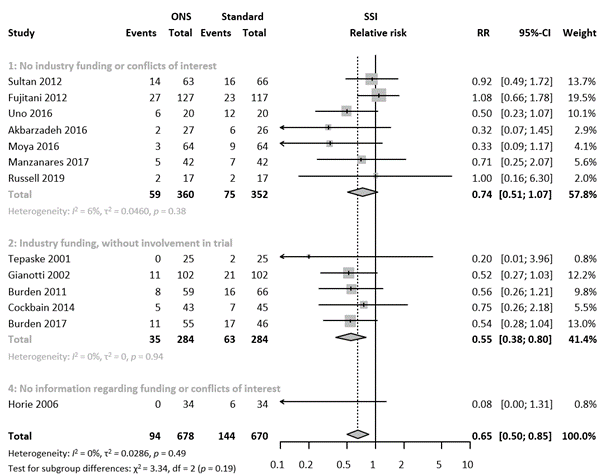

In total 1345 patients were randomly assigned to take preoperative ORAL ENS (n= 678) or no ORAL ENS (n= 670). In total 238 SSI were reported, corresponding with an overall SSI rate of 17.7%. The meta-analysis showed that 94 of 678 patients had SSI in de oral ENS group (13.9%), and 802 of 6,895 patients had SSI in the control group (21.5%), resulting in an overall relative risk (RR) of 0.65 (95%CI 0.50 - 0.85), a statistically significant difference favoring the oral ENS group. Heterogeneity between studies was low (I2= 0%, τ2 = 0.0286, χ2 p = 0.49). The forest plot for SSI is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1. Forest plot of primary outcome SSI. Results are shown in relative risks (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

Subgroup analyses

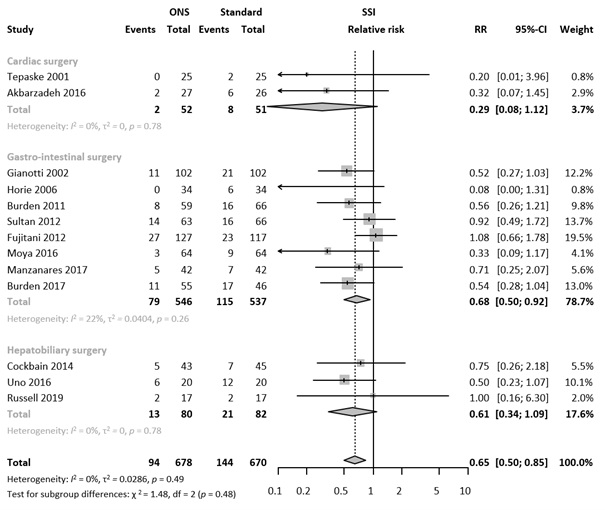

Type of surgery

We performed a subgroup analysis to evaluate the efficacy of preoperative oral ENS on SSI across different types of surgery. The subgroup analysis with forest plot is presented in Figure 2. A statistically significant difference favoring oral ENS on SSI was found in gastrointestinal surgery (RR 0.68; 95% CI 0.50 - 0.92). No statistically significant difference between groups for SSI was found in cardiac surgery (RR 0.82; 95%CI 0.66 - 1.03), and hepatobiliary surgery (RR 0.09; 95%CI 0.01 - 1.60). Meta-regression analysis indicated comparable results in the subgroups (τ2 = 0.0282, p-value for subgroup differences = 0.48, 1.5% of heterogeneity variance explained).

Figure 2. Forest plot of subgroup analysis based on type of surgery. Results are shown in relative risks (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

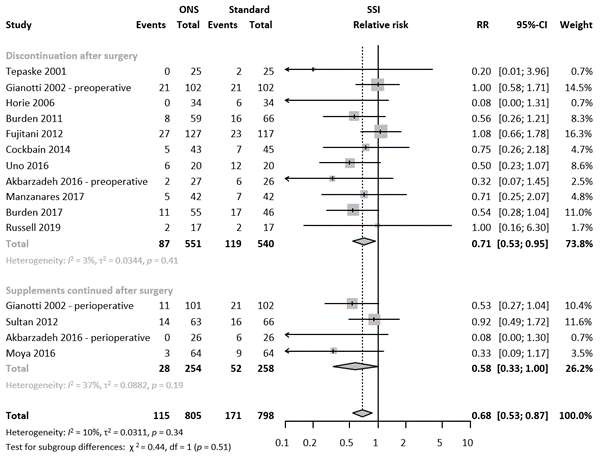

Postoperative continuation

The type of oral ENS and duration of treatment varied greatly between the studies. To evaluate whether continuation of oral ENS influences the efficacy of the oral ENS on SSI we performed a subgroup analysis. The forest plot of the subgroup analysis is presented in figure 3. Only four studies continued the oral ENS after the surgery, with an RR of 0.58 (95% CI 0.33 – 1.00). Meta-regression analysis indicated comparable results in the subgroups (τ2 = 0.0345, p-value for subgroup differences = 0.72, 0% of heterogeneity variance explained).

Figure 3. Forest plot of subgroup analysis based postoperative continuation of oral ENS. Results are shown in relative risks (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

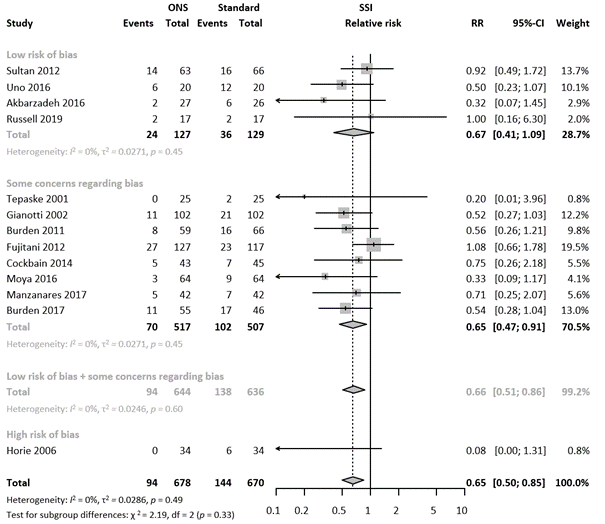

Study quality

We evaluated if the quality of the included studies influences the efficacy of immunonutrition by performing a sensitivity analysis. The results of the sensitivity analysis of 1) only low risk of bias (ROB) studies and 2) excluding studies with high ROB showed comparable results to the overall analysis

The efficacy of immunonutrition on SSI in studies with low ROB was RR 0.67 (95%CI 0.41 – 1.09), and after excluding high ROB RR 0.66 (95% CI 0.51 - 0.86). The sensitivity analysis, separating studies with high risk of bias from those with low or risk of bias is presented in Figure 4.

Meta-regression analysis indicated comparable results in the subgroups (τ2 = 0.0383, p-value for subgroup differences = 0.34, 0% of heterogeneity variance explained).

Figure 4. Forest plot of subgroup analysis based on risk of bias. Results are shown in relative risks (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

Industry involvement

We performed a sensitivity analysis based on conflicts of interest and industry funding of the included studies (Figure 4). Studies were scored into four categories: 1: no industry funding or involvement; 2: industry funding, without involvement in trial design; 3: industry involvement in trial design or no information on the degree of industry involvement; 4: no information (Statements on industry involvement).

Seven studies had no industry funding or conflicts of interest, five studies did receive industry funding without influence of the funder in the trial. One study did not provide information on industry funding.

Meta-regression analysis indicated different results in the subgroups (τ2 = 0, p-value for subgroup differences = 0.06, 100% of heterogeneity variance explained).

Figure 5. Forest plot of subgroup analysis based on degree of influence of industry. Results are shown in relative risks (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

Minimum days of preoperative nutrition

We performed a meta-regression analysis based on the minimum number of days of treatment prior to surgery. The analysis showed that minimum days of treatment prior to surgery is not a significant effect size predictor (p = 0.37). Studies with longer minimum days of treatment prior to surgery were not associated with a larger reduction in SSI, with a regression coefficient of 0.13. This means that for every additional minimum days of treatment prior to surgery, the effect size (relative risk) is expected to rise by 0.13.

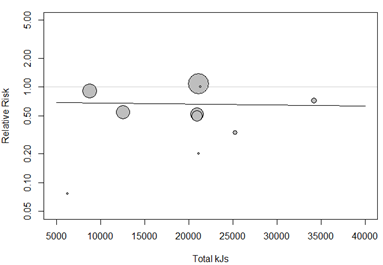

Total kJ given to patients (pre and post-surgery)

We performed a meta-regression analysis based on the total amount of kJ patients received. The analysis showed that total kJ is not a significant effect size predictor (p = 0.70). Studies with larger amounts of kJ were not associated with a larger reduction in SSI, with a regression coefficient of 0.

Secondary outcomes

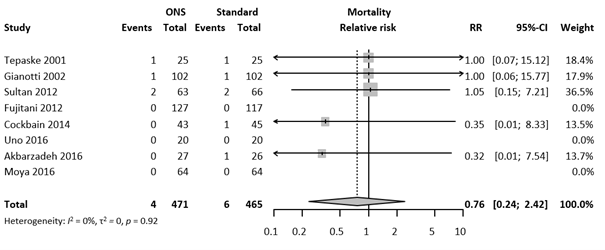

Mortality

The effect of oral ENS on all-cause mortality was evaluated in 936 patients. In total 10 patients died, corresponding with an overall mortality of 1.1%. This resulted in an RR of 0.76 (95% CI 0.24 – 2.42). The forest plot with meta-analysis is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Forest plot of secondary outcome Mortality. Results are shown in relative risks (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

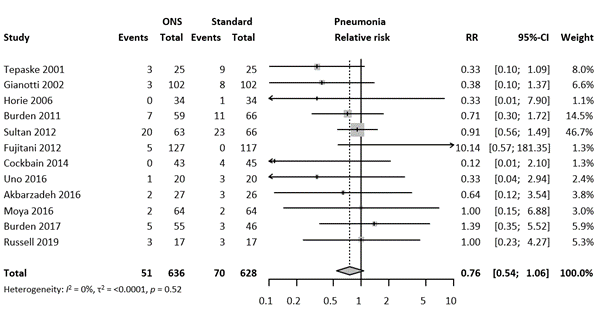

Pneumonia

The outcome pneumonia was investigated in twelve studies, with 121 SSI in 1264 patients (9.7%). We found an RR of 0.76 (95% 0.54 – 1.06). The forest plot is showed in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Forest plot of secondary outcome Pneumonia. Results are shown in relative risks (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

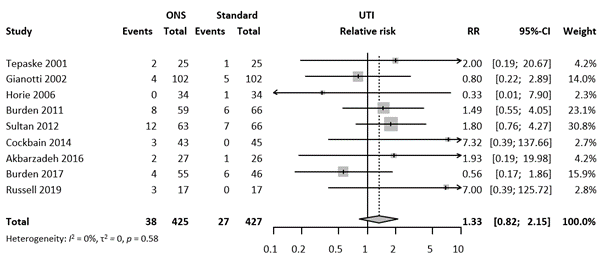

Urinary tract infection

Nine studies investigated the effect of oral ENS on urinary tract infections. The incidence was 7.6% (65 SSI in 857 patients), with an RR of 1.33 (95% CI 0.82 – 2.15). The forest plot can be found in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Forest plot of secondary outcome Urinary tract infection. Results are shown in relative risks (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

Adverse events

The potential adverse events were also investigated. Only five studies mentioned adverse events. In none of the studies the adverse events were suspected to be related to the use of TCS. Three studies reported some patients experiencing gastrointestinal events, and two studies reported no adverse events related to the oral ENS. In total 27 adverse events were reported in 279 patients (9.7%).

|

Study |

Adverse events |

|

|

Akbarzadeh 2016 |

“There were no supplement-related complications.” |

|

|

Burden 2011 |

“Nausea and vomiting were reported by four patients and exacerbation of diarrhoea was reported in two cases.”

|

Nausea, vomiting I: 4 / 54 (7.4%) C: no information |

|

Burden 2017 |

“Intolerance of ONS was reported by seven (out of 55) participants who did not manage to follow the ONS regimen; these included nausea reported by four participants, abdominal discomfort reported by three participants, and diarrhoea reported by two (two participants reported more than one intolerance symptoms). Thus, seven participants reported that they did not tolerate the supplements due to unpalatability.” |

Abdominal discomfort, diarrhea I: 7 / 55 (12.7%) C: no information |

|

Cockbain 2014 |

“EPA-FFA was well tolerated in patients with colorectal cancer liver metastases with adverse events limited to mild or moderate upper gastrointestinal symptoms, and diarrhea in 12% and 19% of patients taking EPA-FFA, respectively (table 2).” |

Diarrhea, upper GI upset (mild) I: 13 / 43 (30%) C: 3 / 44 (6.8%) |

|

Fujitani 2012 |

No information |

|

|

Gianotti 2002 |

“There were 7 patients with diarrhea in the perioperative group, 3 in the preoperative group, and 3 in the conventional group (P = NS).”

|

Diarrhea I: 3 / 102 (2.9%) C: 3 / 102 (2.9% |

|

Horie 2006 |

No information |

|

|

Manzanares 2017 |

No information |

|

|

Moya 2016 |

No information |

|

|

Russell 2019 |

No information |

|

|

Sultan 2012 |

No information |

|

|

Tepaske 2001 |

“Preoperative supplemental nutrition was well tolerated and no signs of volume overload or other adverse effects were seen.” |

Adverse effects I: 0 / 25 (0%) C: no information |

|

Uno 2016 |

No information |

|

Table 1. Adverse events as reported by the individual studies

Level of evidence of the literature

The GRADE approach for rating the certainty of estimates of treatment effects was used. Since all included studies are randomized controlled trials, the rating for the GRADE starts high for all outcomes. Each outcome can be downgraded due to one of five following reasons.

The quality assessment of the individual studies is presented in the risk of bias (ROB) tables in Risk of bias assessment. Only one study showed high ROB. Since the sensitivity analyses excluding high ROB studies showed comparable results we decided not to downgrade for ROB. Inconsistency was deemed not serious because we found no statistical (: I2 = 0%, τ2 = 0.0286, p = 0.49) or clinical heterogeneity. Regarding imprecision, it was assessed as not serious as the overall 95% CI of the treatment effect did not cross the thresholds of minimally clinically important benefit or harm. All included studies reported in the same population (surgical patients), intervention (oral ENS), control (no nutritional support) and outcome (SSI), indicating no indirectness. The comparison-adjusted funnel plot showed signs of small-study effects. Despite the comparable results with the trim and fill analysis we decided to downgrade for the domain publication bias. This concludes to a moderate certainty of evidence for SSI.

The certainty of the evidence, and absolute effects per outcome are presented in the GRADE-table. A visual presentation of the absolute differences between oral ENS and regular diet with GRADE certainty levels is presented in a visual presentation.

|

Study |

N = |

Procedure |

Type of nutrition |

Nutrition per day |

Total kJ |

Regimen |

Control |

SAP |

|

Akhbarzadeh 2016 |

53 |

Coronary artery bypass grafting

|

Self-made, total: 15g glutamine 3 g L-carnitine 750 mg vit. C 250 mg vit E 150 μg |

Self-made 2.1 g glutamine 0.4 g L-carnitine 107.1 mg vit. C 35.7 g vit. E 21.4 μg selenium |

Not estimable |

The 7 days prior to surgery Twice daily |

Placebo |

NI |

|

Burden 2011 |

125 |

Laparoscopic colorectal surgery

|

Fortisip, per 100 ml 630 kJ 6 g protein Fortijuce, per 100 ml 630 kJ 4 g protein |

Fortisip 2520 kJ 24 g protein Fortijuce 2520 kJ 16g protein |

37 days 93.240 kJ |

From randomization to surgery (mean 37 days) 400 ml/day |

Dietary advice |

NI |

|

Burden 2017 |

101 |

Open and laparoscopic colorectal surgery |

Fortisip Compact, per 1 ml 10.1 kJ 0.096 g protein |

Fortisip Compact 2525 kJ 24 g protein |

5-7 days 12625 – 17675 kJ |

The 5-7 days prior to surgery 250 ml/day |

Dietary advice |

NI |

|

Cockbain 2014 |

88 |

Liver resection |

ALFA, per 500g 495 g EPA-FFA |

ALFA 990 g EPA-FFA |

Not estimable |

From randomization to surgery (median 30 days) 1000 mg/day |

Placebo |

NI |

|

Fujitani 2012 |

244 |

Elective total gastrectomy |

Impact, per 100ml 101 kcal (= 423 kJ) 5.6 g protein 0.8 g fat 0.20 g EPA 0.14 g DHA n-6 : n-3 ratio 4 : 5 13.4 g carbohydrate 1.28 g arginine 0.13 mg RNA |

Impact 1010 kcal (= 4226 kJ) 56 g protein 8 g fat 2 g EPA 1.4 g DHA n-6 : n-3 ratio 4 : 5 134 g Carbohydrate 12.8 g Arginine 1.3 mg RNA |

5 days 21129 kJ |

The 5 days prior to surgery 1000 ml/day |

Regular diet |

Yes |

|

Gianotti 2002 |

204 |

Major elective surgery gastrointestinal tract |

Impact, per 1000 ml 1000 kcal (= 4184 kJ) 12.5 g arginine 3.3 g ω-3 fatty acid 1.2 g RNA |

Impact 1000 kcal (= 4184 kJ) 12.5 g arginine 3.3 g ω-3 fatty acid 1.2 g RNA |

5 days 20920 kJ |

The 5 days prior to surgery 1000 ml/day

|

Regular diet |

Yes |

|

Horie 2006 |

78 |

Elective colorectal surgery |

Impact (Japanese version), per 750 ml 750 kcal (= 3138 kJ) 9.6g arginine 2.49 g ω -3 fatty acids 0.96 g RNA

|

Impact (Japanese version) 750 kcal (= 3138 kJ) 9.6g arginine 2.49 g ω -3 fatty acids 0.96 g RNA |

2-6 days 6276 – 18828 kJ |

From 6 to 2 days prior to surgery 750 ml/day |

NI |

Yes |

|

Manzanares 2017 |

84 |

Elective colorectal surgery |

Impact, per 237 ml 341 kcal (= 1427 kJ) 18.1 g proteins 4.2 gl-arginine 44.7 g carbohydrates 9.2 g fats (1.4 g ω -3 fatty acids) 3.3 g fibre, 0.43 g nucleotides Vitamins Trace elements |

Impact 1023 kcal (4280 (kJ) 54.3 g proteins 12.6 gl-arginine 134.1 g carbohydrates 27.6 g fats (4.2 g ω -3 fatty acids) 9.9 g fibre 1.29 g nucleotides Vitamins Trace elements |

8 days 34242 kJ |

The 8 days prior to surgery 711 ml/day

|

Regular diet |

NI |

|

Moya 2016 |

|

Laparoscopic colorectal surgery |

(IEF)-ATEMPERO, per 100ml 151 kcal (= 632 kJ) 8.3 g protein - 1 g arginine - 0.2 g RNA 13.3 g carbohydrate 1 g sugars 5 g fat - 0.77 g ω-3 fatty acids 1.7 g fiber Na, Cl, K, Chl, Mg, P, Zn, Cu, Mn, I, F, Cr, Mo, Se Vitamin A, C, D, E K B1, B2, B6, B12 Other (panthothenic acid, biotin, folic acid, choline) |

(IEF)-ATEMPERO 604 kcal (= 2527 kJ) 33.2 g protein - 4 g arginine - 0.8 g RNA 53.2 carbohydrate 4 g sugars 20 g fat - 3.08 g ω-3 fatty acids 6.8 g giber

|

10 days 25271 kJ |

The 5 days prior to surgery to 5 days postoperatively 400 ml/day |

Dietary advice |

Yes |

|

Russell 2019 |

34 |

Open hepatic resection |

Impact advanced recovery, per 711 ml 1020 kcal energy (=4268 kJ) 54 g protein 12.6 g arginine 1.3 g nucleotides 3.3 g EPA + DHA |

Impact advanced recovery 1020 kcal (= 4268 kJ) 54 g protein 12.6 g arginine 1.3 g nucleotides 3.3 g eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) + docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) |

5 days 21338 kJ |

The 5 days prior to surgery 711 ml/day |

Regular diet |

Yes |

|

Sultan 2012 |

221 |

Subtotal oesophagectomy, total gastrectomy |

Oxepa, per 100 ml 150 kcal (628 kJ) 6.25 g protein 0.51 g EPA 0.22 g DHA no free arginine or glutamine

|

Oxepa 150 kcal (628 kJ) 6.25 g protein 0.51 g EPA 0.22 g DHA no free arginine or glutamine

|

14 days 8786 kJ |

The 7 days prior to 7 days after surgery 625 ml/day |

Ensure plus |

Yes |

|

Tepaske 2001 |

50 |

Cardiac surgery |

Impact, per 100 ml 101 kcal (= 423 kJ) 5.6 g total proteins 4.35 g whey protein 1.25 g free L-arginine 0.13 g RNA 2.80 total lipids 0.31 g LA+LNA 0.33 g ω-3 fatty acids 0.29 ω-6 fatty acids (LA) 13.30 g carbohydrates 1.10 nitrogen content 1.00 g fibre |

Impact 1010 kcal (= 4230 kJ) 5.6 g total proteins 4.35 g whey protein 1.25 g free L-arginine 0.13 g RNA 2.80 total lipids 0.31 g LA+LNA 0.33 g ω-3 fatty acids 0.29 ω-6 fatty acids 13.30 g carbohydrates 1.10 nitrogen content 1.00 g fibre |

5-10 days 21150 – 42300 kJ |

5-10 L/day during 5-10 days prior to surgery +/- 1 l/day |

Placebo |

Yes |

|

Uno 2016 |

40 |

Major hepatobiliary resection |

Impact, per day 1000 kcal (= 4184 kJ) EPA Arginine Nucleotides |

Impact 1000 kcal (= 4184 kJ) EPA Arginine Nucleotides |

5 days 20920 kJ |

The 5 days prior to surgery

|

Dietary advice |

Yes |

|

DHA: docosahexaenoic acid (an ω-3 fatty acid); EPA: eicosapentaenoic acid (an ω-3 fatty acid); FFA: free fatty acid; LA: linoleic acid; LNA: linolenic acid; RNA: Ribonucleic acid |

||||||||

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effect of preoperative oral enhanced nutritional support (ENS) patients with normonutrition undergoing surgical procedures on the risk of surgical site infections (SSI)?

P: Well-nourished adult patients, undergoing surgical procedures

I: Preoperative oral enhanced nutritional support (immunonutrition; ORAL ENS)

C: No additional preoperative nutritional support (no ORAL ENS)

O: Surgical site infections, mortality, other infectious complications, and adverse

events

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered SSI as a critical outcome measure for decision making and mortality and other infectious complications as important outcomes for clinical decision making.

The working group defined a threshold of 10% for continuous outcomes and a relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes of <0.80 and >1.25 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

Three electronic databases were searched including PubMED, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials by Cadili et al. The detailed search strategy is available on request via https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/. The systematic literature search resulted in 324 hits.

RCTs published in English, Dutch or German from inception to July 2022 were eligible for inclusion if they (a) involved adult (≥18 years of age) patients undergoing any type of elective surgery, (b) compared preoperative oral ENS containing macronutrients (defined as proteins, fats, and/or carbohydrates) to either no intervention (standard diet), placebo, or dietary advice only, and (c) collected data on the development of postoperative SSI.

Sixty-five studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 46 studies were excluded, and 13 RCTs were included. Furthermore, six additional non-randomized cohort studies were included.

Results

Thirteen RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature under the tab 'Samenvatting literatuur'. Important study characteristics and results and quality assessments are summarized in the evidence tables and risk of bias tables under the 'evidence tabellen' tab.

Referenties

- Akbarzadeh, M., Eftekhari, M. H., Shafa, M., Alipour, S., & Hassanzadeh, J. (2016). Effects of a New Metabolic Conditioning Supplement on Perioperative Metabolic Stress and Clinical Outcomes: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Iranian Red Crescent medical journal, 18(1), e26207. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.26207

- Braga, M., & Gianotti, L. (2005). Preoperative immunonutrition: cost-benefit analysis. JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition, 29(1 Suppl), S57–S61. https://doi.org/10.1177/01486071050290S1S57

- Burden, S. T., Hill, J., Shaffer, J. L., Campbell, M., & Todd, C. (2011). An unblinded randomised controlled trial of preoperative oral supplements in colorectal cancer patients. Journal of human nutrition and dietetics : the official journal of the British Dietetic Association, 24(5), 441–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01188.x

- Burden, S. T., Gibson, D. J., Lal, S., Hill, J., Pilling, M., Soop, M., Ramesh, A., & Todd, C. (2017). Pre-operative oral nutritional supplementation with dietary advice versus dietary advice alone in weight-losing patients with colorectal cancer: single-blind randomized controlled trial. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle, 8(3), 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12170

- Cadili, L., van Dijk, P. A. D., Grudzinski, A. L., Cape, J., & Kuhnen, A. H. (2023). The effect of preoperative oral nutritional supplementation on surgical site infections among adult patients undergoing elective surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of surgery, 226(3), 330–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2023.06.011

- Chevrou-Séverac, H., Pinget, C., Cerantola, Y., Demartines, N., Wasserfallen, J. B., & Schäfer, M. (2014). Cost-effectiveness analysis of immune-modulating nutritional support for gastrointestinal cancer patients. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland), 33(4), 649–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2013.09.001

- Cockbain, A. J., Volpato, M., Race, A. D., Munarini, A., Fazio, C., Belluzzi, A., Loadman, P. M., Toogood, G. J., & Hull, M. A. (2014). Anticolorectal cancer activity of the omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid. Gut, 63(11), 1760–1768. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306445

- Fujitani, K., Tsujinaka, T., Fujita, J., Miyashiro, I., Imamura, H., Kimura, Y., Kobayashi, K., Kurokawa, Y., Shimokawa, T., Furukawa, H., & Osaka Gastrointestinal Cancer Chemotherapy Study Group (2012). Prospective randomized trial of preoperative enteral immunonutrition followed by elective total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. The British journal of surgery, 99(5), 621–629. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.8706

- Gianotti, L., Braga, M., Nespoli, L., Radaelli, G., Beneduce, A., & Di Carlo, V. (2002). A randomized controlled trial of preoperative oral supplementation with a specialized diet in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroenterology, 122(7), 1763–1770. https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.2002.33587

- Horie, H., Okada, M., Kojima, M. et al. Favorable Effects of Preoperative Enteral Immunonutrition on a Surgical Site Infection in Patients with Colorectal Cancer Without Malnutrition. Surg Today 36, 1063–1068 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-006-3320-8

- Manzanares Campillo, M. D. C., Martín Fernández, J., Amo Salas, M., & Casanova Rituerto, D. (2017). Estudio prospectivo y randomizado sobre inmunonutrición oral preoperatoria en pacientes intervenidos por cáncer colorrectal: estancia hospitalaria y costos sanitarios [A randomized controlled trial of preoperative oral immunonutrition in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer: hospital stay and health care costs]. Cirugia y cirujanos, 85(5), 393–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.circir.2016.10.029

- Mauskopf, J. A., Candrilli, S. D., Chevrou-Séverac, H., & Ochoa, J. B. (2012). Immunonutrition for patients undergoing elective surgery for gastrointestinal cancer: impact on hospital costs. World journal of surgical oncology, 10, 136. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-10-136

- Moya, P., Miranda, E., Soriano-Irigaray, L., Arroyo, A., Aguilar, M. D., Bellón, M., Muñoz, J. L., Candela, F., & Calpena, R. (2016). Perioperative immunonutrition in normo-nourished patients undergoing laparoscopic colorectal resection. Surgical endoscopy, 30(11), 4946–4953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-4836-7

- NICE guideline - https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg32

- Reis, A. M., Kabke, G. B., Fruchtenicht, A. V., Barreiro, T. D., & Moreira, L. F. (2016). Cost effectivenes of perioperative immunonutrition in gastrointestinal oncologic surgery: a systematic review. Arquivos brasileiros de cirurgia digestiva : ABCD = Brazilian archives of digestive surgery, 29(2), 121–125. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-6720201600020014

- Russell, K., Zhang, H. G., Gillanders, L. K., Bartlett, A. S., Fisk, H. L., Calder, P. C., Swan, P. J., & Plank, L. D. (2019). Preoperative immunonutrition in patients undergoing liver resection: A prospective randomized trial. World journal of hepatology, 11(3), 305–317. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i3.305

- Sultan, S M Griffin, F Di Franco, J A Kirby, B K Shenton, C J Seal, P Davis, Y K S Viswanath, S R Preston, N Hayes, Randomized clinical trial of omega-3 fatty acid-supplemented enteral nutrition versus standard enteral nutrition in patients undergoing oesophagogastric cancer surgery, British Journal of Surgery, Volume 99, Issue 3, March 2012, Pages 346–355, https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.7799

- Senkal, M., Zumtobel, V., Bauer, K. H., Marpe, B., Wolfram, G., Frei, A., Eickhoff, U., & Kemen, M. (1999). Outcome and cost-effectiveness of perioperative enteral immunonutrition in patients undergoing elective upper gastrointestinal tract surgery: a prospective randomized study. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill.: 1960), 134(12), 1309–1316. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.134.12.1309

- Tepaske, R., Velthuis, H., Oudemans-van Straaten, H. M., Heisterkamp, S. H., van Deventer, S. J., Ince, C., Eÿsman, L., & Kesecioglu, J. (2001). Effect of preoperative oral immune-enhancing nutritional supplement on patients at high risk of infection after cardiac surgery: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England), 358(9283), 696–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05836-6

- Uno, H., Furukawa, K., Suzuki, D., Shimizu, H., Ohtsuka, M., Kato, A., Yoshitomi, H., & Miyazaki, M. (2016). Immunonutrition suppresses acute inflammatory responses through modulation of resolvin E1 in patients undergoing major hepatobiliary resection. Surgery, 160(1), 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2016.01.019

- Weimann, A., Braga, M., Carli, F., Higashiguchi, T., Hübner, M., Klek, S., Laviano, A., Ljungqvist, O., Lobo, D. N., Martindale, R. G., Waitzberg, D., Bischoff, S. C., & Singer, P. (2021). ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland), 40(7), 4745–4761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2021.03.031

Evidence tabellen

|

|

Certainty assessment |

№ of patients |

Effect |

Certainty |

||||||||

|

Outcome |

№ of studies |

Study design |

Risk of bias |

Inconsistency |

Indirectness |

Imprecision |

Other considerations |

Oral ENS |

No nutritional support |

Relative |

Absolute |

|

|

Primary outcome |

||||||||||||

|

SSI |

13 |

RCTs |

Not serious |

Not serious (I2 = 0%) |

Not serious |

Not serious |

Publication bias |

94 / 678 (13.9%) |

144 / 670 (21.5%) |

RR 0·65 (0.50 – 0.85) |

75 fewer per 1.000 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

|

Mortality |

8 |

RCTs |

Not serious |

Not serious (I2 = 0%) |

Not serious |

Not serious

|

None |

4 / 471 (0.8%) |

6 / 465 (1.3%) |

RR 0.76 (0.24 – 2.42) |

|

|

|

Pneumonia |

12 |

RCTs |

Not serious |

Not serious (I2 = 0%) |

Not serious |

Not serious

|

None |

51 / 636 (8.0%) |

70 / 628 (11.1%) |

RR 0.76 (0.54 – 1.06) |

|

|

|

UTI |

9 |

RCTs |

Not serious |

Not serious (I2 = 0%) |

Not serious |

Not serious

|

None |

38 / 425 (8.9%) |

27 / 427 (6.3%) |

RR 1.33 (0.82 – 2.15) |

|

|

Statements on industry involvement

|

Study |

Statement on COI and funding |

|

|

Akbarzadeh 2016 |

“This article was extracted from Marzieh Akbarzadeh’s PhD dissertation and funded by Grant Number 91-6447 from Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.” |

1 |

|

Burden 2011 |

“The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest. Funding for this trial was from a NHS Fellowship Award, Central Manchester Foundation Trust and C.” “The authors would like to thank … Nutricia Ltd for providing the oral supplements.” |

2 |

|

Burden 2017 |

“Dr Sorrel Burden received a travel grant received to attend a scientific meeting from Nutricia UK in 2013.” “The authors would like to thank Nutricia UK for the provision of supplements for the trial.” “This study was funded by Macmillan Cancer Support and British Dietetics Association.” |

2 |

|

Cockbain 2014 |

“The Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Awards and Advisory Committee approved the Trial. PML and ADR were supported by Department of Health/Cancer Research UK Yorkshire Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre funding. The Trial was adopted by the UKCRN Clinical Trials Portfolio (UKCRN ID 8946) allowing West Yorkshire Comprehensive Local Research Network funding of Pharmacy costs. SLA Pharma AG funded some of the experimental work and provided EPA-FFA and placebo. SLA Pharma AG played no role in the design or execution of the Trial. Laboratory costs were also supported by the Leeds Teaching Hospitals Charitable Foundation (Rays of Hope).” “MAH and AB have received unrestricted scientific grant funding and meeting expenses from SLA Pharma AG. MAH is listed as an inventor on a composition and use patent, which includes EPA-FFA (US Provisional Patent Application No. 60/411,067). He receives no royalties from this Patent.” |

2 |

|

Fujitani 2012 |

“The immunonutrition (Impact®) was purchased by Osaka Gastrointestinal Cancer Chemotherapy Study Group and distributed to each participating institution. Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.” |

1 |

|

Gianotti 2002 |

“The authors thank Novartis Consumer Health (Bern, Switzerland) for generously providing the diets used in this study.” |

2 |

|

Horie 2006 |

No information |

4 |

|

Manzanares 2017 |

“The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.” |

1 |

|

Moya 2016 |

“This study was supported by a scholarship from La Fundacio´n de la Mutua Madrileña.” “Pedro Moya, Elena Miranda, Leticia Soriano-Irigaray, Antonio Arroyo, Maria-del-Mar Aguilar, Marta Bello’n, Jose-Luis Muñoz, Fernando Candela, and Rafael Calpena have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose. |

1 |

|

Russell 2019 |

“Supported by: Australasian Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Research Grant and A+ Trust Small Project Grant, No. 5576.” “None of the authors has any conflicts of interest related to this study.” |

1 |

|

Sultan 2012 |

“Funding was received from the Northern Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Fund and from a consumables grant from the Newcastle Healthcare Charity (the Trustees). Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.” |

1 |

|

Tepaske 2001 |

“The study was supported, in part, by Novartis Nutrition®, Bern, Switzerland. We thank Heinz Schneider and Adrian Heini, Novartis Nutrition, Bern, Switzerland ….’ |

2 |

|

Uno 2016 |

“Supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 23591892” |

1 |

|

Score 1: no industry funding or involvement 2: industry funding, without involvement in trial design 3: industry involvement in trial design or no information on the degree of industry involvement 4: no information |

||

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 17-12-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-12-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules 2 tot 16 is in 2020 op initiatief van de NVvH een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties. Daarnaast is in 2022 op initiatief van het Samenwerkingsverband Richtlijnen Infectiepreventie (SRI) een separate multidisciplinaire werkgroep samengesteld voor de herziening van de WIP-richtlijn over postoperatieve wondinfecties: module 17-22. De ontwikkelde modules van beide werkgroepen zijn in deze richtlijn samengevoegd.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoek financiering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Mevr. prof. dr. M.A. Boermeester |

Chirurg |

* Medisch Ethische Commissie, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC * Antibiotica Commissie, Amsterdam UMC |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Hieronder staan de beroepsmatige relaties met bedrijfsleven vermeld waarbij eventuele financiële belangen via de AMC Research B.V. lopen, dus institutionele en geen persoonlijke gelden zijn: Skillslab instructeur en/of spreker (consultant) voor KCI/3M, Smith&Nephew, Johnson&Johnson, Gore, BD/Bard, TELABio, GDM, Medtronic, Molnlycke.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Institutionele grants van KCI/3M, Johnson&Johnson en New Compliance.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Ik maak me sterk voor een 100% evidence-based benadering van maken van aanbevelingen, volledig transparant en reproduceerbaar. Dat is mijn enige belang in deze, geen persoonlijk gewin.

Overige belangen Geen.

|

Extra kritische commentaarronde. |

|

Dhr. dr. M.J. van der Laan |

Vaatchirurg |

Vice voorzitter Consortium Kwaliteit van Zorg NFU, onbetaald

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen.

|

Geen.

|

|

Dhr. dr. W.C. van der Zwet |

Arts-microbioloog |

Lid Regionaal Coördinatie Team, Limburgs infectiepreventie & ABR Zorgnetwerk (onbetaald) |

||

|

Dhr. dr. D.R. Buis |

Neurochirurg |

Lid Hoofdredactieraad Tijdschrift voor Neurologie & Neurochirurgie - onbetaald |

||

|

Dhr. dr. J.H.M. Goosen |

Orthopaedisch Chirurg |

Inhoudelijke presentaties voor Smith&Nephew en Zimmer Biomet. Deze worden vergoed per uur. |

||

|

Mw. drs. H. Jalalzadeh |

Arts-onderzoeker |

Geen. |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen. |

Geen.

|

|

Dhr. dr. N. Wolfhagen |

AIOS chirurgie |

|||

|

Mw. drs. H. Groenen |

Arts-onderzoeker |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. F.F.A. Ijpma |

Traumachirurg |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. P. Segers |

Cardiothoracaal chirurg |

|||

|

Mw. Y.E.M. Dreissen |

AIOS neurochirurgie |

|||

|

Dhr. R.R. Schaad |

Anesthesioloog |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voor de invitational conference. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptmodules zijn tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt. Voor de modules 17-22 was de patiëntfederatie vertegenwoordigd in de werkgroep.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn.

Voor module 8 (Negatieve druktherapie) geldt dat uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000 - 40.000 patiënten). Tevens volgt uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht.

Voor de overige modules en aanbevelingen geldt dat uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten). Tevens volgt uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Ook wordt geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners verwacht of een wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

Zie voor de implementatie het implementatieplan in het tabblad 'Bijlagen'.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroepen de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die chirurgie ondergaan. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door middel van een invitational conference. De verslagen hiervan zijn opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Adaptatie

Een aantal modules van deze richtlijn betreft een adaptatie van modules van de World Health Organization (WHO)-richtlijn ‘Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection’ (WHO, 2018), te weten:

- Module Normothermie

- Module Immunosuppressive middelen

- Module Glykemische controle

- Module Antimicrobiële afdichtingsmiddelen

- Module Wondbeschermers bij laparotomie

- Module Preoperatief douchen

- Module Preoperatief verwijderen van haar

- Module Chirurgische handschoenen: Vervangen en type handschoenen

- Module Afdekmaterialen en operatiejassen

Methode

- Uitgangsvragen zijn opgesteld in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

- De inleiding van iedere module betreft een korte uiteenzetting van het knelpunt, waarbij eventuele onduidelijkheid en praktijkvariatie voor de Nederlandse setting wordt beschreven.

- Het literatuuronderzoek is overgenomen uit de WHO-richtlijn. Afhankelijk van de beoordeling van de actualiteit van de richtlijn is een update van het literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd.

- De samenvatting van de literatuur is overgenomen van de WHO-richtlijn, waarbij door de werkgroep onderscheid is gemaakt tussen ‘cruciale’ en ‘belangrijke’ uitkomsten. Daarnaast zijn door de werkgroep grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming gedefinieerd in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten, en is de interpretatie van de bevindingen primair gebaseerd op klinische relevantie van het gevonden effect, niet op statistische significantie. In de meta-analyses zijn naast odds-ratio’s ook relatief risico’s en risicoverschillen gerapporteerd.

- De beoordeling van de mate van bewijskracht is overgnomen van de WHO-richtlijn, waarbij de beoordeling is gecontroleerd op consistentie met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (GRADE-methode; http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). Eventueel door de WHO gerapporteerde bewijskracht voor observationele studies is niet overgenomen indien ook gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde studies beschikbaar waren.

- De conclusies van de literatuuranalyse zijn geformuleerd in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

- In de overwegingen heeft de werkgroep voor iedere aanbeveling het bewijs waarop de aanbeveling is gebaseerd en de aanvaardbaarheid en toepasbaarheid van de aanbeveling voor de Nederlandse klinische praktijk beoordeeld. Op basis van deze beoordeling is door de werkgroep besloten welke aanbevelingen ongewijzigd zijn overgenomen, welke aanbevelingen niet zijn overgenomen, en welke aanbevelingen (mits in overeenstemming met het bewijs) zijn aangepast naar de Nederlandse context. ‘De novo’ aanbevelingen zijn gedaan in situaties waarin de werkgroep van mening was dat een aanbeveling nodig was, maar deze niet als zodanig in de WHO-richtlijn was opgenomen. Voor elke aanbeveling is vermeld hoe deze tot stand is gekomen, te weten: ‘WHO’, ‘aangepast van WHO’ of ‘de novo’.

Voor een verdere toelichting op de procedure van adapteren wordt verwezen naar de Bijlage Adapteren.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

World Health Organization. Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection,

second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475, accessed 12 June 2023).

Zoekverantwoording

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H,

Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

World Health Organization. Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection,

second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475, accessed 12 June 2023).