Doelgericht vochtbeleid (normovolemie)

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het effect van doelgericht vochtbeleid (normovolemie) bij volwassen patiënten die chirurgische ingrepen ondergaan op de preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties?

Aanbeveling

Pas doelgericht vochtbeleid toe bij patiënten in een perioperatief traject ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties. Doelgericht vochtbeleid is op meerdere gelijkwaardige manieren (invasief en non-invasief) te meten en uit te voeren.

Indien er geen algemene hoog-risico indicatie is voor niet invasieve monitoring of dit niet mogelijk is (vanwege bijvoorbeeld type operatie, anesthesietechniek en/of patiënten karakteristieken) dan is het toepassen van invasieve monitoring voor doelgericht vochtbeleid met als enige doel preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties niet geïndiceerd.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De systematische literatuur analyse en meta-analyse van Jalalzadeh (2024, ongepubliceerd) onderzocht het effect van doelgericht vochtbeleid op het ontstaan van postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI) in patiënten die chirurgie ondergaan. Er werd bewijs met redelijke GRADE gevonden dat het risico op POWI vermindert met het gebruik van doelgericht vochtbeleid protocol, in vergelijking met geen specifiek vochtbeleid (RR 0.68; 95%CI 0.60 - 0.79). Het gunstige effect werd ook gezien voor de uitkomsten pneumonie (RR 0.79; 95% CI 0.68 - 0.93), urineweginfectie (RR 0.72; 95%CI 0.53 - 0.97), en het aantal patiënten met één of meer complicaties (RR 0.81; 95%CI 0.73 - 0.89).

Het gunstige effect wordt gezien bij gastro-intestinale en niet-gastro-intestinale chirurgie. Ook bij schone versus gecontamineerde chirurgie wordt er een gunstig effect gezien van een doelgericht vochtbeleid protocol, hoewel dit effect wel groter lijkt bij schone chirurgie.

Doelgericht vochtbeleid is op meerdere manieren (invasief en non-invasief) te meten en uit te voeren. Er lijkt geen verschil in uitkomsten te zijn tussen invasieve en non-invasieve methoden.

De geïncludeerde studies lieten een hoge heterogeniteit zien van patiëntenpopulatie en behandelingsalgoritmen zoals beschreven in het 5T raamwerk (Saugel), dat de nadruk legt op (T1) adequate doelpopulatie, (T2) timing van de interventie, (T3) type interventie, (T4) doelvariabele, en (T5) doelwaarde. In de meta-regressie analyse, waarin de individuele componenten in de studies zijn onderzocht, werd geen sterk statistisch bewijs gevonden dat elk van de losse componenten significant effectief is. Er is geen bewijs dat doelgericht vochtbeleid niet effectief zou zijn bij populaties met een laag risico volgens ASA-classificatie of CDC-wondclassificatie. Ook ontbreekt het bewijs dat de effecten van doelgericht vochtbeleid beperkt zijn tot gastro-intestinale chirurgie of cardiothoracale chirurgie.

De toename in de grootte van het effect dat werd waargenomen bij elke T die werd aangehouden, suggereert dat dit wel kan helpen bij het sturen van een goed algoritme van het doelgerichte vochtbeleid.

Echter, het hebben van een algoritme voor doelgericht vochtbeleid is niet voldoende om verbetering in klinische uitkomsten te krijgen. Er is ook kennis en training nodig om doelgericht vochtbeleid toe te kunnen passen.

Internationale richtlijnen

De WHO adviseert het gebruik van intra-operatieve doelgerichte normovolemie om het risico op POWI te verminderen. De NICE richtlijn van het Verenigd Koninkrijk adviseert “Overweeg cardiale output monitoring voor grote of complexe operaties of operaties met een hoog risico om complicaties te verminderen”. De Amerikaanse CDC richtlijn heeft geen aanbeveling omtrent het gebruik van doelgerichte normovolemie.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten

Er zijn geen voorkeuren van patiënten met betrekking tot het gebruik van doelgericht vochtbeleid op patiënt gerelateerde uitkomsten. Het inbrengen van een arterielijn kan door de patiënt als hinderlijk worden ervaren.

Kosten

Er zijn geen studies gevonden die de kosteneffectiviteit van doelgerichte chirurgie hebben onderzocht op POWI. POWI is echter een dure complicatie en het voorkomen van POWI draagt bij aan de kostenreductie.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Doelgericht vochtbeleid is een interventie die nog niet breed wordt toegepast, en veel ziekenhuizen hebben niet de juiste apparatuur. De aanschafprijs en onderhoud van de apparaten kunnen en belemmering zijn voor de haalbaarheid implementatie. Voor de toepassing van doelgerichte vochtbeleid is het ook van belang dat de uitvoerder op de hoogte is van het protocol en de besturing/interpretatie van het protocol. Hiervoor zal training en onderwijs verzorgd moeten worden.

Bij niet alle patiënten en ingrepen is een arterielijn geïndiceerd en aangesloten. Dan kan er overwogen worden om een niet-invasieve methode van doelgericht vochtbeleid toe te passen. Indien een patiënt wel een arterielijn heeft of krijgt kan er een invasieve methode van doelgericht vochtbeleid worden gekozen.

De werkgroep doet geen aanbeveling voor een specifiek protocol van doelgericht vochtbeleid. Enkele instellingen hebben lokale protocollen voor doelgericht vochtbeleid.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er is een gunstig effect van de toepassing van een doelgerichte vochtbeleid protocol ten opzichte van geen specifiek vochtbeleid protocol bij de preventie van POWI bij chirurgische patiënten. Er wordt geen verschil in effect gezien in patiënten met hoge of lage ASA-classificaties, typen wondclassificaties, of typen chirurgie.

Voor protocollen omtrent doelgericht vochtbeleid verwijst de werkgroep naar lokale instellingsprotocollen. Voor de effectiviteit en de uitvoering van doelgericht vochtbeleid bij hoog risico patiënten verwijst de werkgroep naar de richtlijn Perioperative Goal Directed Therapy (PGDT).

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI) zijn een van de meest voorkomende zorg-gerelateerde infecties en een zeer relevante oorzaak van postoperatieve morbiditeit en mortaliteit. De groei van het aantal patiënten dat chirurgische ingrepen ondergaat en het toenemende aantal patiënten met comorbiditeit met een hoog risico op POWI onderstreept de noodzaak voor de preventie van POWI.

Adequate oxygenatie van het weefsel is essentieel voor wondgenezing, en omgekeerd is perioperatieve weefselhypoxie gerelateerd aan slechte uitkomsten voor de patiënt. Omdat zowel hypervolemie als hypovolemie leiden tot verminderde weefseloxygenatie, is perioperatief vocht beleid cruciaal om adequate weefseloxygenatie te bereiken. Conventioneel vochtbeleid wordt uitgevoerd door de anesthesist op basis van klinische beoordeling en hemodynamische metingen, die mogelijk niet adequaat de veranderingen in het intravasculaire volume weergeven. Zowel hypovolemie als hypervolemie blijven veelvoorkomend bij chirurgische patiënten. Algoritmen voor doelgerichte vochttherapie (Goal Directed Fluid Therapy; GDFT) zijn ontwikkeld om het vochtbeleid te standaardiseren en optimaliseren, waarbij specifieke hemodynamische streefwaarden sturend zijn voor de intraveneuze vloeistof, vasopressor en inotrope medicatie toediening.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Surgical site infections

|

Hoge GRADE |

Peroperatief doelgericht vochtbeleid vermindert het aantal postoperatieve wondinfecties in vergelijking met geen specifiek vochtbeleid protocol bij patiënten die een operatie ondergaan.

Bron: Jalalzadeh (2024, unpublished) |

Mortaliteit

|

Redelijke GRADE |

Peroperatief doelgericht vochtbeleid resulteert waarschijnlijk niet in een vermindering van mortaliteit in vergelijking met geen specifiek vochtbeleid protocol bij patiënten die een operatie ondergaan.

Bron: Jalalzadeh (2024, unpublished) |

Sepsis

|

Redelijke GRADE |

Peroperatief doelgericht vochtbeleid resulteert waarschijnlijk niet in een vermindering van sepsis in vergelijking met geen specifiek vochtbeleid protocol bij patiënten die een operatie ondergaan.

Bron: Jalalzadeh (2024, unpublished) |

Pneumonie

|

Hoge GRADE |

Peroperatief doelgericht vochtbeleid vermindert het aantal pneumoniën in vergelijking met geen specifiek vochtbeleid protocol bij patiënten die een operatie ondergaan.

Bron: Jalalzadeh (2024, unpublished) |

Urineweginfectie

|

Hoge GRADE |

Peroperatief doelgericht vochtbeleid lijkt het aantal urineweginfecties te verminderen in vergelijking met geen specifiek vochtbeleid protocol bij patiënten die een operatie ondergaan.

Bron: Jalalzadeh (2024, unpublished) |

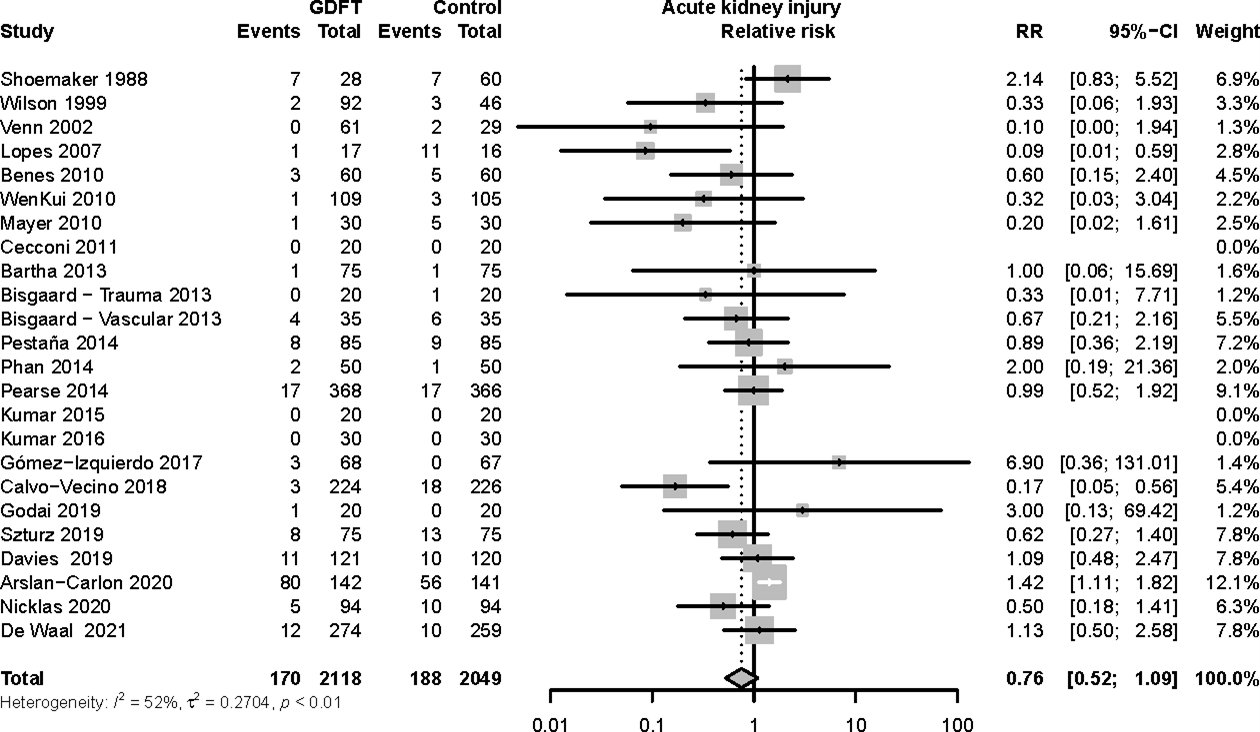

Acute nierinsufficiëntie

|

Lage GRADE |

Peroperatief doelgericht vochtbeleid lijkt het aantal acute nierinsufficiëntie te verminderen in vergelijking met geen specifiek vochtbeleid protocol bij patiënten die een operatie ondergaan.

Bron: Jalalzadeh (2024, unpublished) |

Paralytische ileus

|

Redelijke GRADE |

Peroperatief doelgericht vochtbeleid vermindert waarschijnlijk het aantal paralytische ileus in vergelijking met geen specifiek vochtbeleid protocol bij patiënten die een operatie ondergaan.

Bron: Jalalzadeh (2024, unpublished) |

Reoperatie

|

Redelijke GRADE |

Peroperatief doelgericht vochtbeleid resulteert waarschijnlijk niet of nauwelijks in een vermindering van het aantal reoperaties in vergelijking met geen specifiek vochtbeleid protocol bij patiënten die een operatie ondergaan.

Bron: Jalalzadeh (2024, unpublished) |

Aantal patiënten met één of meer complicaties

|

Redelijke GRADE |

Peroperatief doelgericht vochtbeleid vermindert waarschijnlijk het aantal patiënten met één of meer complicaties in vergelijking met geen specifiek vochtbeleid protocol bij patiënten die een operatie ondergaan.

Bron: Jalalzadeh (2024, unpublished) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Study characteristics of the included studies can be found in the Study characteristics. Multiple haemodynamic monitoring devices were used to perform GDFT, and the haemodynamic management goals and protocols varied greatly between studies. Most studies used one or more of the following variables: stroke volume (SV), stroke volume variation (SVV), pulse pressure variation (PPV), cardiac index (CI) and mean arterial pressure (MAP).

Of the 68 included studies, used a haemodynamic monitoring device connected to an arterial line to monitor the haemodynamic goals. Fourteen studies used an oesophageal Doppler, six studies used a non-invasive haemodynamic monitoring sensor, two studies used a device connected to a central venous line, one used blood sampling, one used the pulse variability index, one used a non-invasive cardiac output monitor, and one study used the cardiopulmonary bypass device.

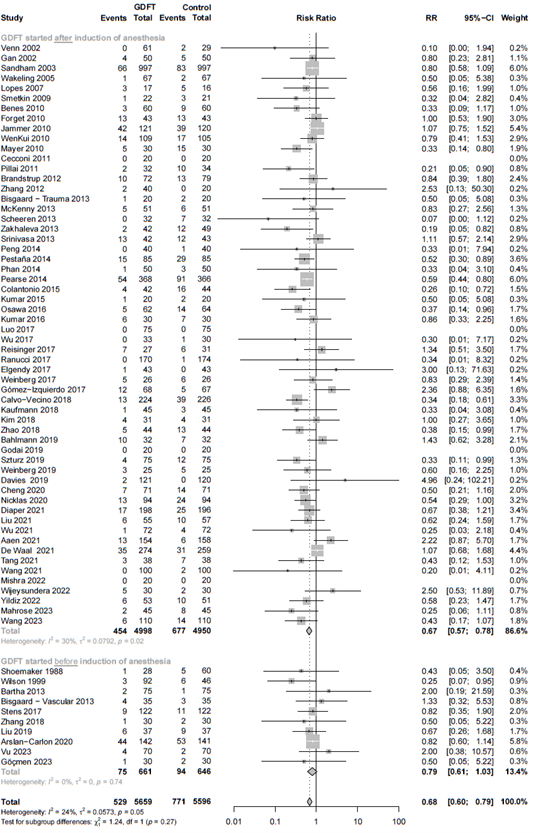

Ten of the studies started with GDFT before the induction of anaesthesia.

In 52 studies, GDFT was ceased at the end of the surgery, and in the remaining 16 studies, GDFT was continued between 1 one and 24 hours postoperatively.

Results

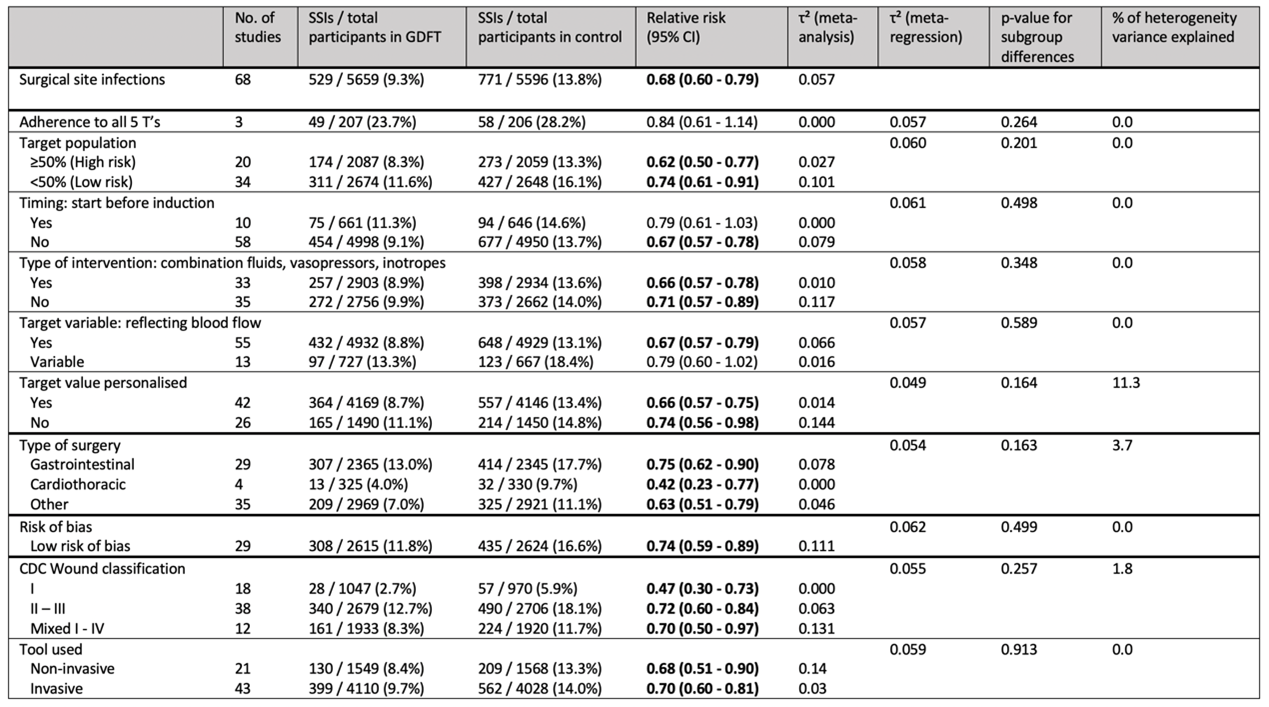

The results of the primary outcome, subgroup and sensitivity analyses are summarized in table 1.

Table 1. Meta-analysis of primary, secondary and subgroup analyses incidence of surgical site infection associated with goal-directed fluid therapy

Surgical site infections (critical)

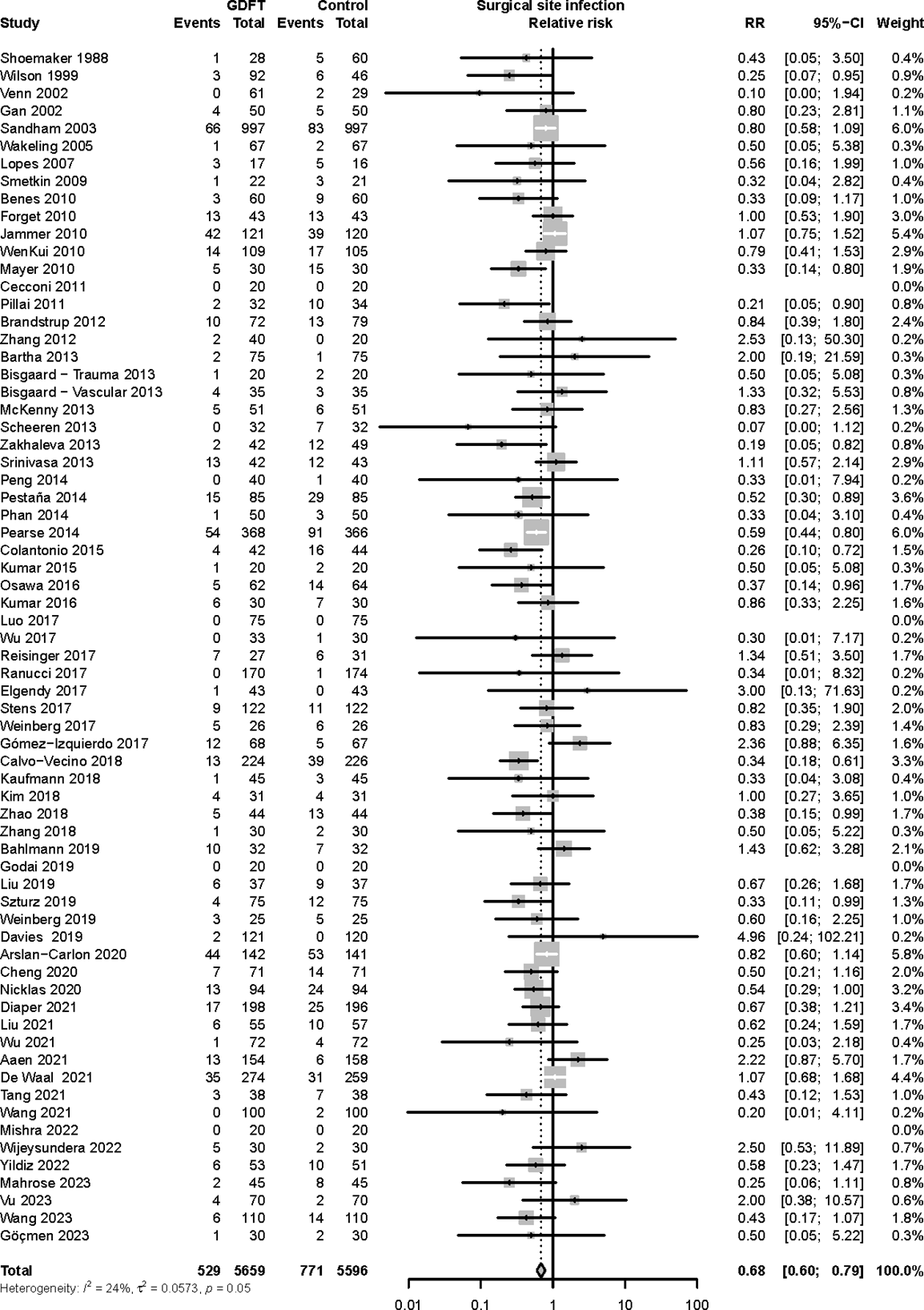

Surgical site infections were reported in 68 trials, retrieved from the systematic review (Jalalzadeh 2023, unpublished).

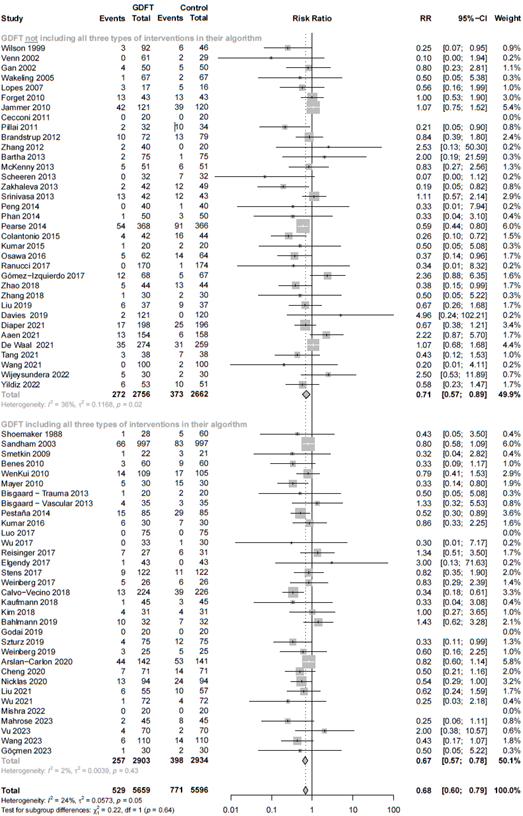

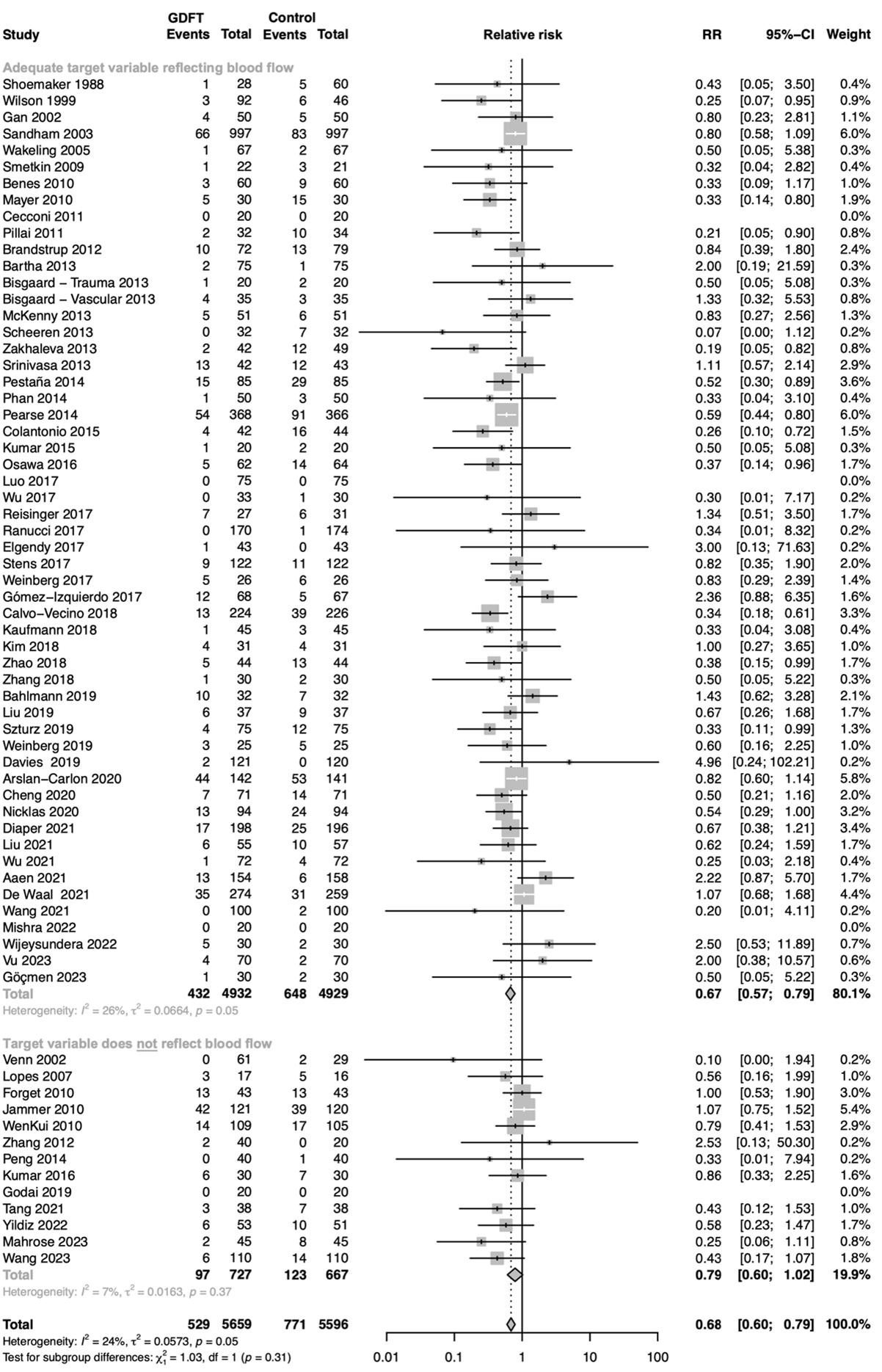

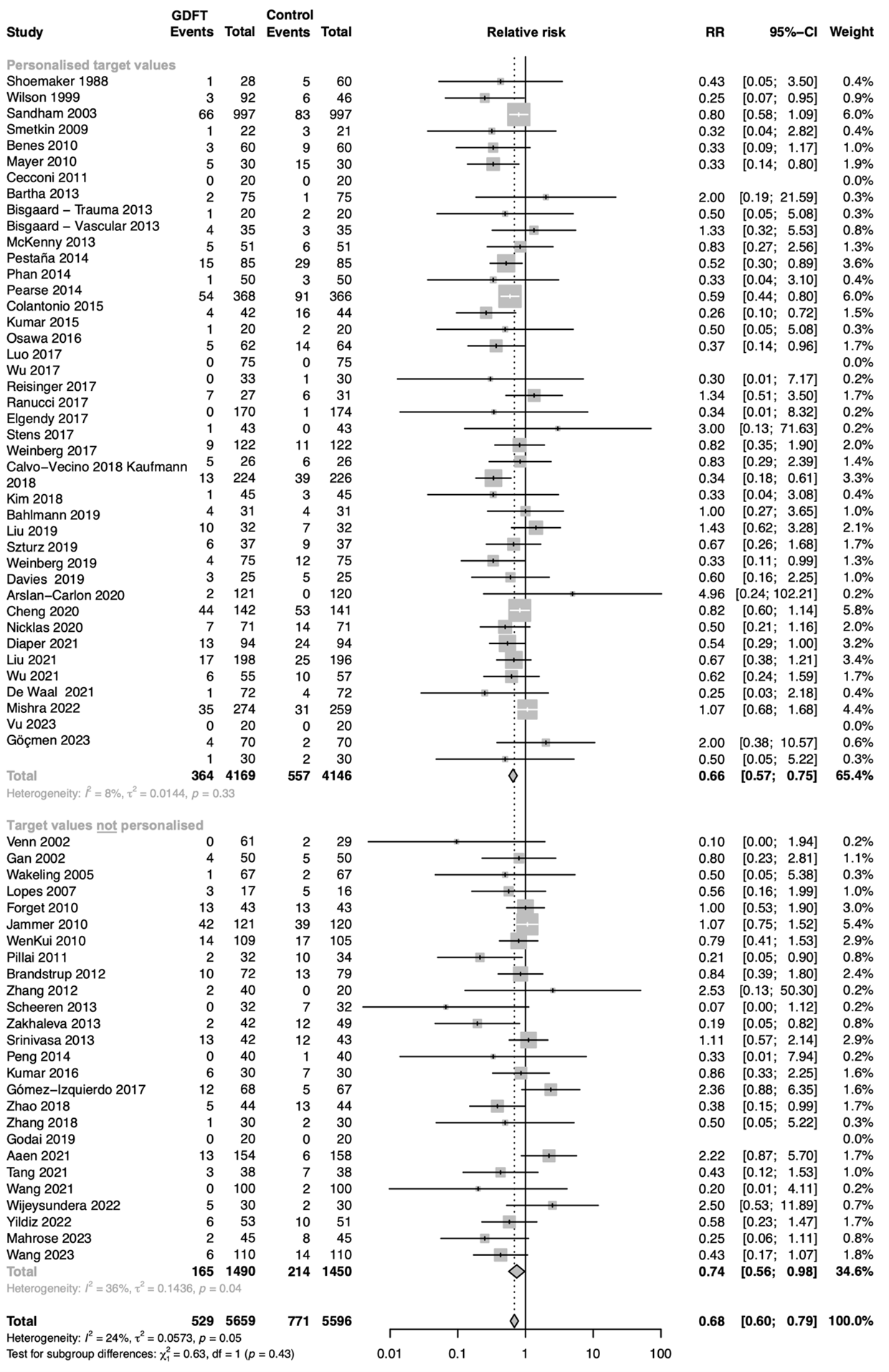

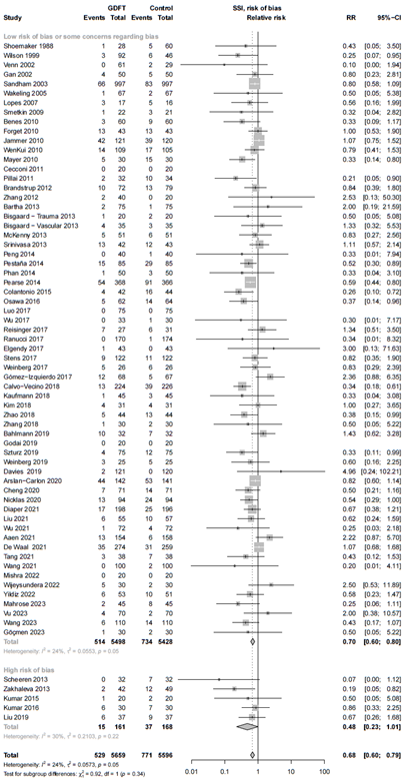

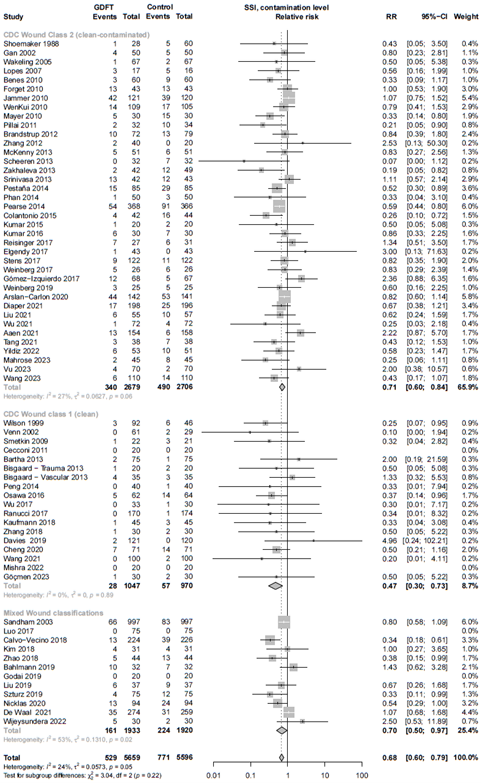

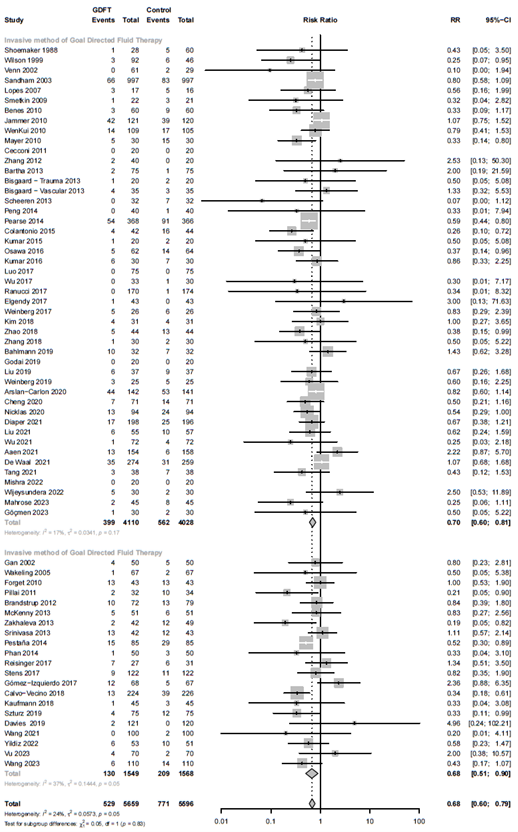

A total of 11.255 patients were included in the systematic review. Meta-analysis indicated that the incidence of SSI was reduced from 13.8% in the control group to 9.3% in the intervention group resulting in a RR of 0.68 (95% CI 0.60 - 0.79). Heterogeneity between studies was moderate (τ2 = 0.0573, p = 0.049, I2 = 23.7%). The result of the primary outcome is shown in Table 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1. Forest plot showing the comparison between goal-directed fluid therapy versus no specific fluid management protocol for surgical site infections. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Secondary outcomes

The results of the secondary outcomes are summarized in table 2. For outcomes pneumonia, urinary tract infection and number of patients with ≥1 complication showed a significant benefit for goal-directed fluid therapy. The forest plots of the secondary outcomes can be found in Forest plots of secondary outcomes.

Table 2. Results of meta-analysis of the secondary outcomes.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

5T’s

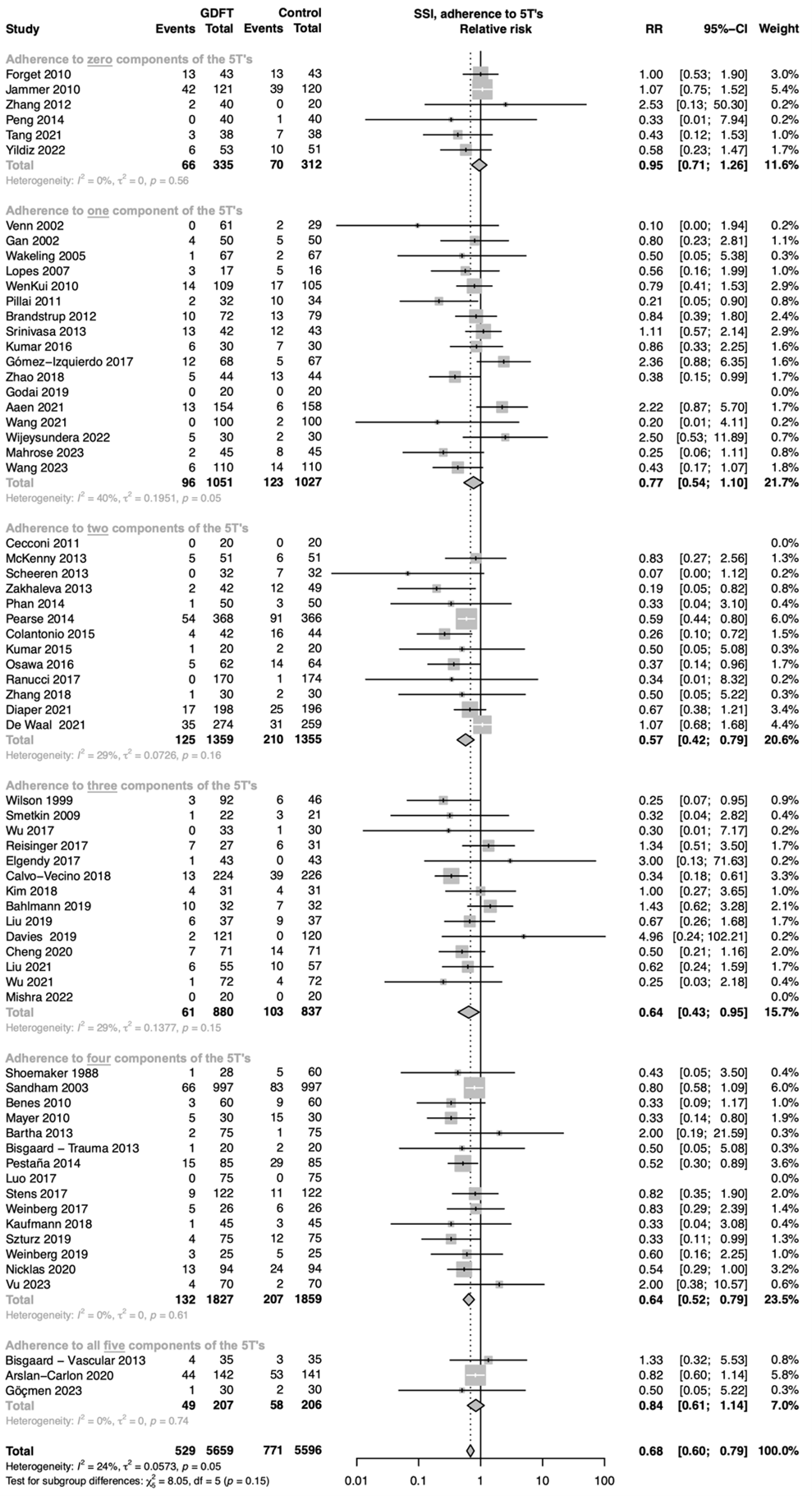

To explore heterogeneity, we performed random effects meta-regression and subgroup analyses according to the “5 T’s of perioperative goal-directed haemodynamic therapy” by Saugel and colleagues. We defined the high risk target population as studies with ≥50% of patients classified as ASA 3 or higher, adequate timing as GDFT algorithms initiated before induction of anaesthesia, adequate type of GDFT algorithm as algorithms incorporating both fluids, vasopressors and inotropes, adequate target variables as variables reflecting blood flow (stroke volume (SV), stroke volume index (SVI), cardiac output (CO), cardiac index (CI), or oxygen delivery (dO2)) and adequate target values as personalised target values. We performed meta-regression and subgroup analyses for each T and the total number of T’s adhered to, and calculated the proportion of heterogeneity variance explained for each subgroup (τ² main analysis - τ² meta regression) / τ² main analysis).

In the subgroup analysis of adherence to the 5 T’s of Saugel et al., only three studies complied with all five components of the proposed framework. Meta-regressions indicated that every additional component complied to led to a 5-point increase in relative risk reduction, but the confidence interval was wide and included no effect (ß -0.05; 95% CI -0.14 – +0.04). Meta regression of each of the separate components indicated no strong evidence for an association with the effect size for any of individual component. (Sub-analysis: 5T’s)

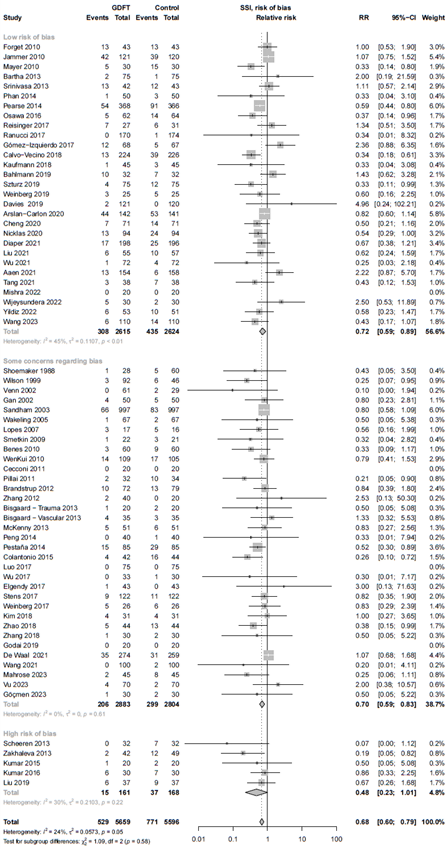

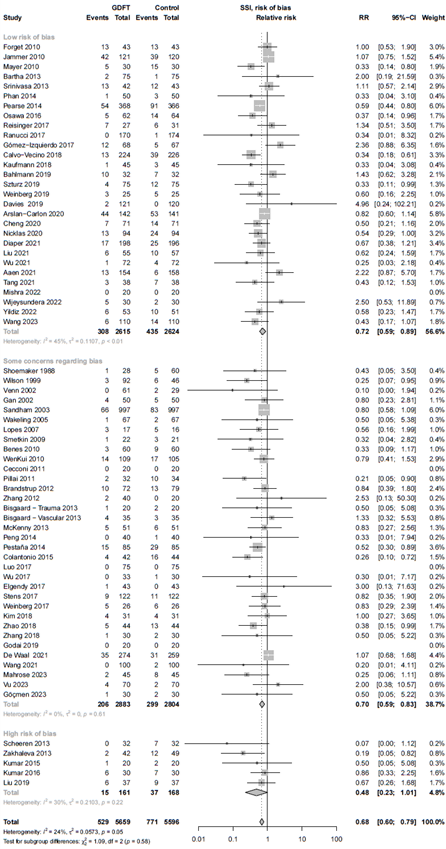

Risk of bias

The sensitivity analysis of the 29 studies with low risk of bias showed an RR of 0.74 (95% CI 0.59 - 0.89; Sub-analysis: risk of bias).

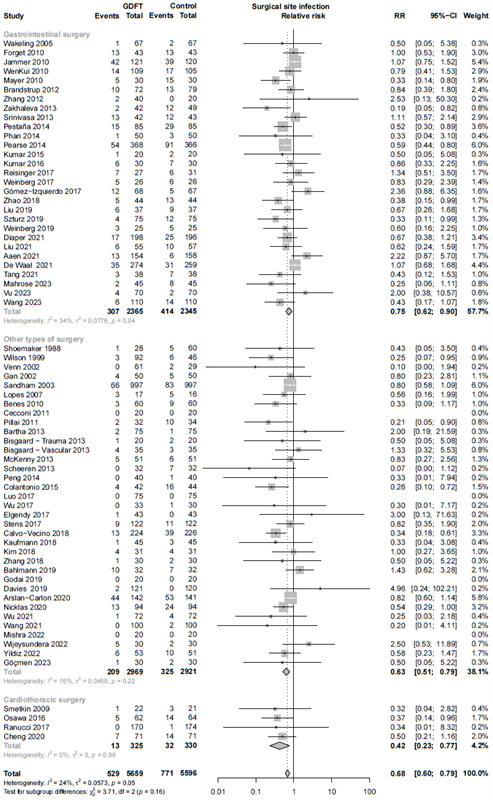

Type of surgery

We explored three types of surgery; gastrointestinal, cardiothoracic, and other types of surgery. We found an RR of 0.75 (95% CI 0.62 – 0.90) for gastrointestinal surgery, an RR of 0.42 (0.23 - 0.77) for cardiothoracic surgery, and an RR of 0.63 (0.51 - 0.79) for other types of surgery. ( Sub-analysis: Type of surgery)

Wound contamination level (CDC classification)

We also performed subgroup analysis based on wound contamination according to the CDC classification (clean, clean-contaminated, contaminated, and dirty) because of their differences in baseline event rate, and type of surgery (gastrointestinal, cardiothoracic and other) because of the differences in haemodynamic consequences.

In 18 studies only clean surgeries (CDC class 1) were included, with an RR of 0.47 (0.30 - 0.73). Thirty-eight studies investigated clean-contaminated (CDC class 2) or contaminated surgeries (CDC class 3), totaling to an RR of 0.72 (0.60 - 0.84). (Sub-analysis: Level of wound contamination)

Invasive vs non-invasive tools

We found no difference in results when using invasive (RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.60 - 0.81) or non-invasive (RR 0.68; 95% CI 0.51 - 0.90) tools of measuring (τ2 = 0.059, p-value for subgroup differences = 0.913, 0% of heterogeneity variance explained). (Sub-analysis: invasive vs. non-invasive)

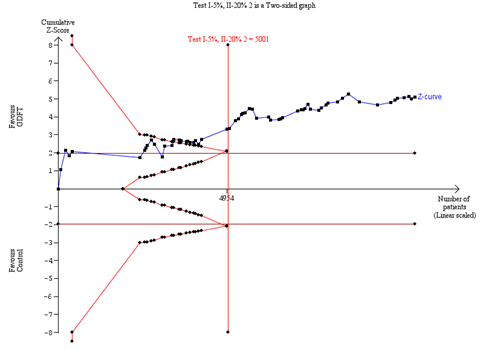

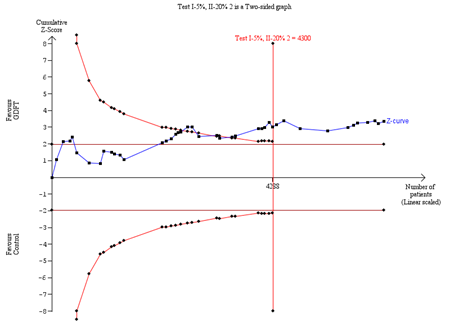

Trial Sequential Analysis

We conducted a trial sequential analysis (TSA) to assess the reliability and robustness of the primary outcome. Diversity-adjusted information size and estimated trial sequential monitoring boundaries were based on a type I error of 5%, a power of 80%, a relative risk reduction of 25% and an SSI risk in the control group of 13.9% as found in the meta-analysis. We carried out a TSA sensitivity analysis limited to low risk of bias studies, with an SSI risk of 16.7% in the control group. When the cumulative Z-curve crosses into the trial sequential monitoring boundary, further data collection is unlikely to change the effect estimate.

TSA showed that the cumulative Z-curve crossed the trial sequential monitoring boundary for benefit (Fig. 3A), indicating that sufficient evidence exists for a 25% relative risk reduction in SSI. This was substantiated in a sensitivity analysis for low risk of bias studies. (Trial sequential analysis)

Level of evidence of the literature

Surgical site infections (critical)

The result of the GRADE assessment is shown in Table 3. The starting certainty of evidence was high as all included studies were RCT’s, however, the certainty of evidence was downgraded to moderate. Although there was some risk of bias (Elaborate risk of bias assessment), the sensitivity analysis results were comparable with the main analysis (Sub-analysis: risk of bias), and we decided not to downgrade for risk of bias.

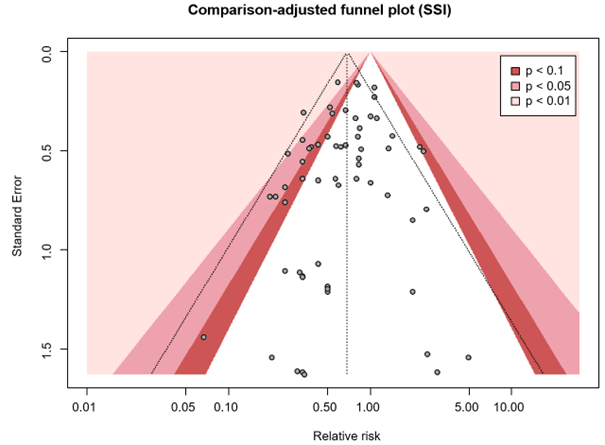

We did not downgrade for inconsistency as despite clinical heterogeneity between protocols of GDFT used in the different trials there was no unexplained heterogeneity. There was no indirectness as all included studies investigated the same patients (patients undergoing surgery), intervention (GDFT), comparison (no specific fluid management protocol) and outcome (SSI). There was no imprecision as appreciable harm was excluded from the 95% confidence interval, and the optimal information size was met (1388 patients per arm). The contour-enhanced comparison-adjusted funnel plot showed no asymmetry, indicating no publication bias (Comparison-adjusted funnel plot).

Table 3. GRADE assessment for all outcomes

Forest plots of secondary outcomes

4A. Mortality

Relative risk of mortality in studies with goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) versus no specific fluid management. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

4B. Sepsis

Relative risk of the incidence of sepsis in studies with goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) versus no specific fluid management. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

4C. Pneumonia

Relative risk of the incidence of pneumonia in studies with goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) versus no specific fluid management. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

4D. Urinary tract infection

Relative risk of the incidence of urinary tract infection in studies with goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) versus no specific fluid management. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

4E. Acute kidney injury

Relative risk of the incidence of acute kidney injury in studies with goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) versus no specific fluid management. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

4F. Paralytic ileus

Relative risk of the incidence of paralytic ileus in studies with goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) versus no specific fluid management. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

4G. Reoperation

Relative risk of the incidence of reoperation in studies with goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) versus no specific fluid management. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

4H. Number of patients with ≥1 complication

Relative risk of the incidence of patients with 1 or more complications in studies with goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) versus no specific fluid management. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

Sub-analysis: 5T’s

5A. Target population

Relative risk of studies grouped for a high-risk patient population (at least 50% of the study population has an American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) score higher than 2) or a low risk patient population, and comparing studies with goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) versus no specific fluid management. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

5B. Timing of intervention

Relative risk of studies grouped for those starting with goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) before induction of anaesthesia versus studies starting with GDFT during or after induction of anaesthesia. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

5C. Type of intervention

Relative risk of studies grouped for those including fluids, inotropes, and vasopressors in their goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) algorithm versus studies not including all three types of interventions in their GDFT algorithm. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

5D. Target variable

Relative risk of studies grouped for those including a target variable, reflecting blood flow (stroke volume, stroke volume index, cardiac output, cardiac index) in their the goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) algorithm versus studies not including a target variable in their GDFT algorithm. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

5E. Target value

Relative risk of studies grouped for those including a personalised target value in their goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) algorithm versus studies not including a personalised target value in their GDFT algorithm. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

5F. Sum of 5Ts

The 5T’s of Saugel represent target population, timing of intervention, type of intervention, target variable, and personalised target variables

Relative risk of five distinct groups associated with a different sum of the adherence to the 5Ts. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

5G. Meta-regression bubble plot of the sum of all components of the 5Ts

The 5T’s of Saugel represent target population, timing of intervention, type of intervention, target variable, and personalised target variables.

Meta-regressions showed that adherence to the 5 T’s was not a significant effect size predictor with a regression coefficient of -0.05 (95% CI -0.14 - 0.04). This means that for every ‘additional T’, the effect size (relative risk) is expected to decline by 0.05.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effect of goal-directed fluid therapy (c) versus no specific fluid management protocol (i) in adult patients undergoing surgical procedures (p) in the prevention of SSI?

P: Patients undergoing any surgical procedure

I: Goal-directed fluid therapy

C: No specific fluid management protocol

O: Surgical site infections, mortality, other postoperative complications

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered surgical site infections (SSI) a critical outcome measure for decision making. Mortality, sepsis, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, acute kidney injury, paralytic ileus, reoperation, and number of patients with at least one complication were important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined a threshold of 10% for continuous outcomes and a relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes of <0.80 and >1.25 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

We performed systematic review and searched in Embase and Ovid/Medline for publications up to August 3rd 2023, for RCTs comparing goal-directed fluid therapy to no specific fluid management protocol. Search terms included: surgical site infection, postoperative wound infection, haemodynamic monitoring, fluid therapy, normovolaemia, goal-directed fluid therapy and other related terms. The detailed search strategy is available on request via https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/. Additional studies were identified by backward and forward citation tracing of previously published meta-analyses and included studies.

The database search resulted in 1451 potential studies, and 35 additional studies were identified by backward and forward citation tracking. We assessed 141 full-text publications, of which 68 studies were included in the systematic review and meta-analyses. The selection process is shown in Flowchart of selected studies. The reason for exclusion after full-text review can be found in the table of excluded studies under the 'evidence tabellen' tab.

Results

Sixty-eight studies were included in the analysis of the literature under the tab 'Samenvatting literatuur'. Important study characteristics and results and quality assessments are summarized in the evidence tables and risk of bias tables under the 'evidence tabellen' tab.

Referenties

- Aaen AA, Voldby AW, Storm N, et al. Goal-directed fluid therapy in emergency abdominal surgery: a randomised multicentre trial. Br J Anaesth 2021; 127(4): 521-31.

- Arslan-Carlon VT, Kay See: Dalbagni, Guido: Pedoto, Alessia C.: Herr, Harry W.: Bochner, Bernard H.: Cha, Eugene K.: Donahue, Timothy F.: Fischer, Mary: Donat, S. Machele. Goal-directed versus Standard Fluid Therapy to Decrease Ileus after Open Radical Cystectomy: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology 2020; 133(2): 293-303.

- Bahlmann HH, I.: Nilsson, L. Goal-directed therapy during transthoracic oesophageal resection does not improve outcome: Randomised controlled trial. European Journal of Anaesthesiology 2019; 36(2): 153-61.

- Bartha EA, C.: Imnell, A.: Fernlund, M. E.: Andersson, L. E.: Kalman, S. Randomized controlled trial of goal-directed haemodynamic treatment in patients with proximal femoral fracture. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2013; 110(4): 545-53., C.: Imnell, A.: Fernlund, M. E.: Andersson, L. E.: Kalman, S. Randomized controlled trial of goal-directed haemodynamic treatment in patients with proximal femoral fracture. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2013; 110(4): 545-53.

- Benes JC, I.: Altmann, P.: Hluchy, M.: Kasal, E.: Svitak, R.: Pradl, R.: Stepan, M. Intraoperative fluid optimization using stroke volume variation in high risk surgical patients: Results of prospective randomized study. Critical Care 2010; 14(3): R118.

- Bisgaard JG, T.: RØnholm, E.: Toft, P. Optimising stroke volume and oxygen delivery in abdominal aortic surgery: A randomised controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 2013; 57(2): 178-88.

- Bisgaard JG, T.: RØnholm, E.: Toft, P. Haemodynamic optimisation in lower limb arterial surgery: Room for improvement? Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 2013; 57(2): 189-98.

- Brandstrup BS, P. E.: Rasmussen, M.: Belhage, B.: Rodt, S. Å: Hansen, B.: Moller, D. R.: Lundbech, L. B.: Andersen, N.: Berg, V.: Thomassen, N.: Andersen, S. T.: Simonsen, L. Which goal for fluid therapy during colorectal surgery is followed by the best outcome: Near-maximal stroke volume or zero fluid balance? British Journal of Anaesthesia 2012; 109(2): 191-9.

- Calvo-Vecino JMR-M, J.: Mythen, M. G.: Casans-Francés, R.: Balik, A.: Artacho, J. P.: Martínez-Hurtado, E.: Serrano Romero, A.: Fernández Pérez, C.: Asuero de Lis, S.: Errazquin, A. T.: Gil Lapetra, C.: Motos, A. A.: Reche, E. G.: Medraño Viñas, C.: Villaba, R.: Cobeta, P.: Ureta, E.: Montiel, M.: Mané, N.: Martínez Castro, N.: Horno, G. A.: Salas, R. A.: Bona García, C.: Ferrer Ferrer, M. L.: Franco Abad, M.: García Lecina, A. C.: Antón, J. G.: Gascón, G. H.: Peligro Deza, J.: Pascual, L. P.: Ruiz Garcés, T.: Roberto Alcácer, A. T.: Badura, M.: Terrer Galera, E.: Fernández Casares, A.: Martínez Fernández, M. C.: Espinosa, Á: Abad-Gurumeta, A.: Feldheiser, A.: López Timoneda, F.: Zuleta-Alarcón, A.: Bergese, S. Effect of goal-directed haemodynamic therapy on postoperative complications in low–moderate risk surgical patients: a multicentre randomised controlled trial (FEDORA trial). British Journal of Anaesthesia 2018; 120(4): 734-44.

- Cecconi MF, N.: Langiano, N.: Divella, M.: Costa, M. G.: Rhodes, A.: Rocca, G. D. Goal-directed haemodynamic therapy during elective total hip arthroplasty under regional anaesthesia. Critical Care 2011; 15(3): R132.

- Cheng XQZ, J. Y.: Wu, H.: Zuo, Y. M.: Tang, L. L.: Zhao, Q.: Gu, E. W. Outcomes of individualized goal-directed therapy based on cerebral oxygen balance in high-risk patients undergoing cardiac surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia 2020; 67: 110032.

- Colantonio LC, C.: Fabrizi, L.: Marcelli, M. E.: Sofra, M.: Giannarelli, D.: Garofalo, A.: Forastiere, E. A randomized trial of goal directed vs. standard fluid therapy in cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract 2015; 19(4): 722-9.

- Davies SJ, Yates DR, Wilson RJT, Murphy Z, Gibson A, Allgar V, Collyer T. A randomised trial of non-invasive cardiac output monitoring to guide haemodynamic optimisation in high risk patients undergoing urgent surgical repair of proximal femoral fractures (ClearNOF trial NCT02382185). Perioper Med (Lond) 2019; 8: 8.

- Diaper JS, E.: Barcelos, G. K.: Luise, S.: Schorer, R.: Ellenberger, C.: Licker, M. Goal-directed hemodynamic therapy versus restrictive normovolemic therapy in major open abdominal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Surgery (United States) 2021; 169(5): 1164-74.

- Elgendy MA, Esmat IM, Kassim DY. Outcome of intraoperative goal-directed therapy using Vigileo/FloTrac in high-risk patients scheduled for major abdominal surgeries: a prospective randomized trial. Egyptian Journal of Anaesthesia 2017; 33(3): 263-9.

- Forget PL, F.: De Kock, M. Goal-directed fluid management based on the pulse oximeter-derived pleth variability index reduces lactate levels and improves fluid management. Anesthesia and Analgesia 2010; 111(4): 910-4.

- Gan TJ, Soppitt A, Maroof M, et al. Goal-directed intraoperative fluid administration reduces length of hospital stay after major surgery. Anesthesiology 2002; 97(4): 820-6.

- Godai KM, A.: Kanmura, Y. The effects of hemodynamic management using the trend of the perfusion index and pulse pressure variation on tissue perfusion: a randomized pilot study. Ja Clin Rep 2019; 5(1): 72.

- Gomez-Izquierdo JC, Trainito A, Mirzakandov D, et al. Goal-directed Fluid Therapy Does Not Reduce Primary Postoperative Ileus after Elective Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology 2017; 127(1): 36-49.

- Jammer IU, A.: Erichsen, C.: Lødemel, O.: Østgaard, G. Does central venous oxygen saturation-directed fluid therapy affect postoperative morbidity after colorectal surgery?: A randomized assessor-blinded controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2010; 113(5): 1072-80.

- Kaufmann KBB, W.: Rexer, J.: Loeffler, T.: Heinrich, S.: Konstantinidis, L.: Buerkle, H.: Goebel, U. Evaluation of hemodynamic goal-directed therapy to reduce the incidence of bone cement implantation syndrome in patients undergoing cemented hip arthroplasty - a randomized parallel-arm trial. BMC Anesthesiology 2018; 18(1): 63.

- Kim HJK, E. J.: Lee, H. J.: Min, J. Y.: Kim, T. W.: Choi, E. C.: Kim, W. S.: Koo, B. N. Effect of goal-directed haemodynamic therapy in free flap reconstruction for head and neck cancer. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 2018; 62(7): 903-14.

- Kumar L, Kanneganti YS, Rajan S. Outcomes of implementation of enhanced goal directed therapy in high-risk patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Indian J Anaesth 2015; 59(4): 228-33.

- Kumar L, Rajan S, Baalachandran R. Outcomes associated with stroke volume variation versus central venous pressure guided fluid replacements during major abdominal surgery. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2016; 32(2): 182-6.

- Liu FL, Jing: Zhang, Weixia: Liu, Zhongkai: Dong, Ling: Wang, Yuelan. Randomized controlled trial of regional tissue oxygenation following goal-directed fluid therapy during laparoscopic colorectal surgery. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology 2019; 12(12): 4390-9.

- Liu XZ, P.: Liu, M. X.: Ma, J. L.: Wei, X. C.: Fan, D. Preoperative carbohydrate loading and intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy for elderly patients undergoing open gastrointestinal surgery: a prospective randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiology 2021; 21(1): 157.

- Lopes MRO, M. A.: Pereira, V. O. S.: Lemos, I. P. B.: Auler Jr, J. O. C.: Michard, F. Goal-directed fluid management based on pulse pressure variation monitoring during high-risk surgery: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Critical Care 2007; 11(5): R100.

- Luo JX, J.: Liu, J.: Liu, B.: Liu, L.: Chen, G. Goal-directed fluid restriction during brain surgery: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Annals of Intensive Care 2017; 7(1): 16.

- Mahrose, R. A., & Kasem, A. A. (2023). Pulse Pressure Variation-Based Intraoperative Fluid Management Versus Traditional Fluid Management for Colon Cancer Patients Undergoing Open Mass Resection and Anastomosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, 13(4).

- Mayer J, Boldt J, Mengistu AM, Rohm KD, Suttner S. Goal-directed intraoperative therapy based on autocalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis reduces hospital stay in high-risk surgical patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care 2010; 14(1): R18.

- McKenny MC, P.: Wong, A.: Farren, M.: Gleeson, N.: Walsh, C.: O'Malley, C.: Dowd, N. A randomised prospective trial of intra-operative oesophageal Doppler-guided fluid administration in major gynaecological surgery. Anaesthesia 2013; 68(12): 1224-31.

- Mishra N, Rath GP, Bithal PK, Chaturvedi A, Chandra PS, Borkar SA. Effect of Goal-Directed Intraoperative Fluid Therapy on Duration of Hospital Stay and Postoperative Complications in Patients Undergoing Excision of Large Supratentorial Tumors. Neurol India 2022; 70(1): 108-14.

- Nicklas JYD, O.: Leistenschneider, M.: Sellhorn, C.: Schön, G.: Winkler, M.: Daum, G.: Schwedhelm, E.: Schröder, J.: Fisch, M.: Schmalfeldt, B.: Izbicki, J. R.: Bauer, M.: Coldewey, S. M.: Reuter, D. A.: Saugel, B. Personalised haemodynamic management targeting baseline cardiac index in high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery: a randomised single-centre clinical trial. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2020; 125(2): 122-32.

- Osawa EA, Rhodes A, Landoni G, et al. Effect of Perioperative Goal-Directed Hemodynamic Resuscitation Therapy on Outcomes Following Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial and Systematic Review. Crit Care Med 2016; 44(4): 724-33.

- Pearse RM, Harrison DA, MacDonald N, et al. Effect of a perioperative, cardiac output-guided hemodynamic therapy algorithm on outcomes following major gastrointestinal surgery: a randomized clinical trial and systematic review. JAMA 2014; 311(21): 2181-90.

- Peng KL, J.: Cheng, H.: Ji, F. H. Goal-directed fluid therapy based on stroke volume variations improves fluid management and gastrointestinal perfusion in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery. Medical Principles and Practice 2014; 23(5): 413-20.

- Pestaña DE, E.: Eden, A.: Nájera, D.: Collar, L.: Aldecoa, C.: Higuera, E.: Escribano, S.: Bystritski, D.: Pascual, J.: Fernández-Garijo, P.: De Prada, B.: Muriel, A.: Pizov, R. Perioperative goal-directed hemodynamic optimization using noninvasive cardiac output monitoring in major abdominal surgery: A prospective, randomized, multicenter, pragmatic trial: POEMAS study (PeriOperative goal-directed thErapy in Major Abdominal Surgery). Anesthesia and Analgesia 2014; 119(3): 579-87.

- Phan TDDS, B.: Rattray, M. J.: Johnston, M. J.: Cowie, B. S. A randomised controlled trial of fluid restriction compared to oesophageal Doppler-guided goal-directed fluid therapy in elective major colorectal surgery within an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery program. Anaesth Intens Care 2014; 42(6): 752-60.

- Pillai PM, I.: Gaughan, M.: Snowden, C.: Nesbitt, I.: Durkan, G.: Johnson, M.: Cosgrove, J.: Thorpe, A. A double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial to assess the effect of doppler optimized intraoperative fluid management on outcome following radical cystectomy. Journal of Urology 2011; 186(6): 2201-6.

- Ranucci M, Johnson I, Willcox T, et al. Goal-directed perfusion to reduce acute kidney injury: A randomized trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018; 156(5): 1918-27 e2.

- Reisinger KW, Willigers HM, Jansen J, Buurman WA, Von Meyenfeldt MF, Beets GL, Poeze M. Doppler-guided goal-directed fluid therapy does not affect intestinal cell damage but increases global gastrointestinal perfusion in colorectal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Colorectal Dis 2017; 19(12): 1081-91.

- Sandham JD, Hull RD, Brant RF, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of the use of pulmonary-artery catheters in high-risk surgical patients. N Engl J Med 2003; 348(1): 5-14.

- Scheeren TWLW, C.: Gerlach, H.: Marx, G. Goal-directed intraoperative fluid therapy guided by stroke volume and its variation in high-risk surgical patients: A prospective randomized multicentre study. Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing 2013; 27(3): 225-33.

- Shoemaker WC, Appel PL, Kram HB, Waxman K, Lee TS. Prospective trial of supranormal values of survivors as therapeutic goals in high-risk surgical patients. Chest 1988; 94(6): 1176-86.

- Smetkin AA, Kirov MY, Kuzkov VV, et al. Single transpulmonary thermodilution and continuous monitoring of central venous oxygen saturation during off-pump coronary surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009; 53(4): 505-14.

- Srinivasa S, Taylor MH, Singh PP, Yu TC, Soop M, Hill AG. Randomized clinical trial of goal-directed fluid therapy within an enhanced recovery protocol for elective colectomy. Br J Surg 2013; 100(1): 66-74.

- Stens J, Hering JP, van der Hoeven CWP, et al. The added value of cardiac index and pulse pressure variation monitoring to mean arterial pressure-guided volume therapy in moderate-risk abdominal surgery (COGUIDE): a pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia 2017; 72(9): 1078-87.

- Szturz PF, P.: Kula, R.: Neiser, J.: Ševčík, P.: Benes, J. Multi-parametric functional hemodynamic optimization improves postsurgical outcome after intermediate risk open gastrointestinal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Minerva Anestesiologica 2019; 85(3): 244-54.

- Tang W, Qiu Y, Lu H, Xu M, Wu J. Stroke Volume Variation-Guided Goal-Directed Fluid Therapy Did Not Significantly Reduce the Incidence of Early Postoperative Complications in Elderly Patients Undergoing Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Surg 2021; 8: 794272.

- Venn RS, A.: Richardson, P.: Poloniecki, J.: Grounds, M.: Newman, P. Randomized controlled trial to investigate influence of the fluid challenge on duration of hospital stay and perioperative morbidity in patients with hip fractures. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2002; 88(1): 65-71.

- Vu, P. H., Duong, N. D. A., Tran, V. D., Tran, T. H., Luu, X. V., Truong, Q. T., ... & Ochiai, R. (2023). Effectiveness of goal-directed fluid therapy guided by estimated continuous cardiac output (esCCO) in major gastrointestinal surgeries: a randomized controlled trial. Anaesthesia, Pain & Intensive Care, 27(3), 371-378.

- de Waal EEC, Frank M, Scheeren TWL, et al. Perioperative goal-directed therapy in high-risk abdominal surgery. A multicenter randomized controlled superiority trial. J Clin Anesth 2021; 75: 110506.

- Wakeling HGM, M. R.: Jenkins, C. S.: Woods, W. G. A.: Miles, W. F. A.: Barclay, G. R.: Fleming, S. C. Intraoperative oesophageal Doppler guided fluid management shortens postoperative hospital stay after major bowel surgery. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2005; 95(5): 634-42.

- Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., Zheng, J., Dong, X., Wu, C., Guo, Z., & Wu, X. (2023). Intraoperative pleth variability index-based fluid management therapy and gastrointestinal surgical outcomes in elderly patients: a randomised controlled trial. Perioperative Medicine, 12(1), 1-10.

- Wang DD, Li Y, Hu XW, Zhang MC, Xu XM, Tang J. Comparison of restrictive fluid therapy with goal-directed fluid therapy for postoperative delirium in patients undergoing spine surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Perioper Med (Lond) 2021; 10(1): 48.

- Weinberg L, Ianno D, Churilov L, et al. Restrictive intraoperative fluid optimisation algorithm improves outcomes in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: A prospective multicentre randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2017; 12(9): e0183313.

- Weinberg L, Ianno D, Churilov L, et al. Goal directed fluid therapy for major liver resection: A multicentre randomized controlled trial. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2019; 45: 45-53.

- WenKui YN, L.: JianFeng, G.: WeiQin, L.: ShaoQiu, T.: Zhihui, T.: Tao, G.: JuanJuan, Z.: FengChan, X.: Hui, S.: WeiMing, Z.: Jie-Shou, L. Restricted peri-operative fluid administration adjusted by serum lactate level improved outcome after major elective surgery for gastrointestinal malignancy. Surgery 2010; 147(4): 542-52.

- Wijeysundera D, Duncan D, Moreno Garijo J, et al. A randomised controlled feasibility trial of a clinical protocol to manage hypotension during major non‐cardiac surgery. Anaesthesia 2022.

- Wilson JW, I.: Fawcett, J.: Whall, R.: Dibb, W.: Morris, C.: McManus, E. Reducing the risk of major elective surgery: Randomised controlled trial of preoperative optimisation of oxygen delivery. British Medical Journal 1999; 318(7191): 1099-103.

- Wu JM, Y.: Wang, T.: Xu, G.: Fan, L.: Zhang, Y. Goal-directed fluid management based on the auto-calibrated arterial pressure-derived stroke volume variation in patients undergoing supratentorial neoplasms surgery. Int J Clin Exp Med 2017; 10(2): 3106-14.

- Wu QFK, H.: Xu, Z. Z.: Li, H. J.: Mu, D. L.: Wang, D. X. Impact of goal-directed hemodynamic management on the incidence of acute kidney injury in patients undergoing partial nephrectomy: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiology 2021; 21(1): 67.

- Yildiz GO, Hergunsel GO, Sertcakacilar G, Akyol D, Karakas S, Cukurova Z. Perioperative goal-directed fluid management using noninvasive hemodynamic monitoring in gynecologic oncology. Braz J Anesthesiol 2022; 72(3): 322-30.

- Zakhaleva J, Tam J, Denoya PI, Bishawi M, Bergamaschi R. The impact of intravenous fluid administration on complication rates in bowel surgery within an enhanced recovery protocol: a randomized controlled trial. Colorectal Dis 2013; 15(7): 892-9.

- Zhang JQ, H.: He, Z.: Wang, Y.: Che, X.: Liang, W. Intraoperative fluid management in open gastrointestinal surgery: Goal-directed versus restrictive. Clinics 2012; 67(10): 1149-55.

- Zhang N, Liang M, Zhang DD, et al. Effect of goal-directed fluid therapy on early cognitive function in elderly patients with spinal stenosis: A Case-Control Study. Int J Surg 2018; 54(Pt A): 201-5.

- Zhao GP, P.: Zhou, Y.: Li, J.: Jiang, H.: Shao, J. The accuracy and effectiveness of goal directed fluid therapy in plateau-elderly gastrointestinal cancer patients: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Int J Clin Exp Med 2018; 11(8): 8516-22.

Evidence tabellen

Sub-analysis: risk of bias

Risk of bias; low and some concerns vs high risk of bias

Relative risk of studies grouped for those with low and some concerns risk of bias versus studies with a high risk of bias. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines. represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

Risk of bias; low vs some concerns vs high risk of bias

Relative risk of studies grouped for low, some concerns, or high risk of bias. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

Sub-analysis: Type of surgery

Relative risk of studies including cardiothoracic, gastrointestinal, or other surgeries. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

Sub-analysis: Level of wound contamination

Relative risk of studies grouped for those including clean surgery, clean-contaminated and contaminated surgery, or mixed contaminated surgery. The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

Sub-analysis: invasive vs. non-invasive

Relative risk of studies using invasive or non-invasive methods of goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT). The figure shows the pooled relative risk (RR). The squares and horizontal lines represent point estimates and corresponding 95% CIs of the individual studies.

A Trial sequential analysis

A. TSA of all randomised controlled trials

Trial sequential analysis (TSA) was based on a relative risk reduction (RRR) of 25%, surgical site infection risk in the control group of 13.9%, a type I error of 5% and a type II error of 20%.

B. TSA of only studies with low risk of bias

Trial sequential analysis (TSA) was based on a relative risk reduction (RRR) of 25%, surgical site infection risk in the control group of 16.7%, a type I error of 5% and a type II error of 20%.

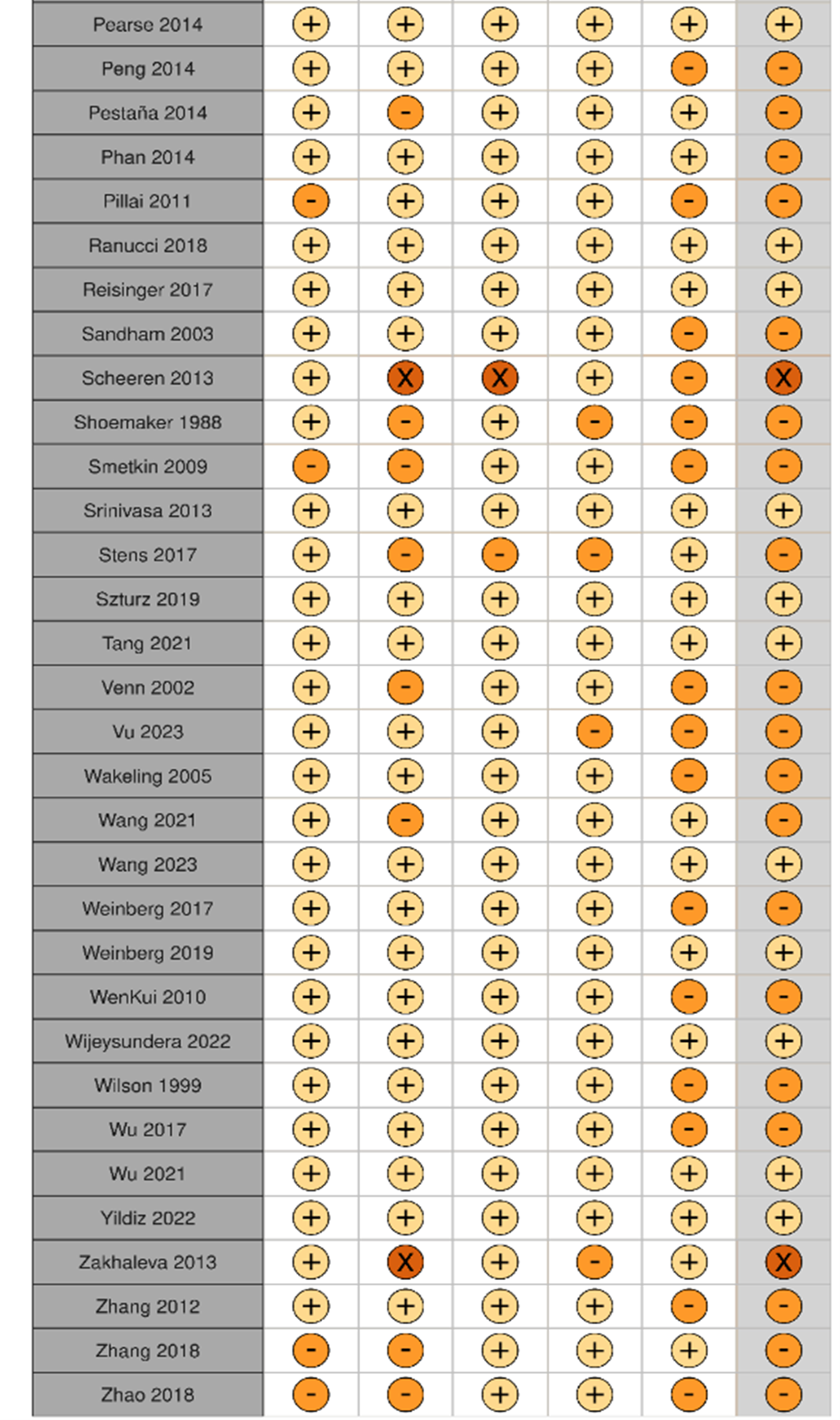

Elaborate risk of bias assessment

Domains:

D1 Bias arising from the randomisation process

D2 Bias due to deviations from the intended intervention

D3 Bias due to missing outcome data

D4 Bias in the measurement of the outcome

D5 Bias in the selection of the reported result

High risk of bias

Some concerns

Low risk of bias

Comparison-adjusted funnel plot

The comparison-adjusted funnel plot shows the effect estimate of a study (relative risks) versus its precision (standard error) for surgical site infection (SSI). The funnel plot shows symmetry indicating no differences between small and large studies regarding the effect of the treatment (small-study effect). Comparison-adjusted funnel plot asymmetry can be caused by publication bias. Since we find no asymmetry (no small-study effect), publication bias is less likely.

Table of excluded studies

|

|

Author, Year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

1 |

Feng, 20231 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

2 |

Hrdy, 20233 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

3 |

Ji, 20234 |

Postoperative GDFT |

|

4 |

Ma, 20235 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

5 |

Schaller, 20236 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

6 |

Chui, 20227 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

7 |

Froghi, 20228 |

Postoperative GDFT |

|

8 |

Hokenek, 20229 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

9 |

Hokenek, 20229 |

Duplicate |

|

10 |

Mishra, 202210 |

Duplicate |

|

11 |

Turkut, 202211 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

12 |

Wongtangman, 202212 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

13 |

Wongtangman, 202112 |

Duplicate |

|

14 |

Bloria, 202113 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

15 |

Cho, 202114 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

16 |

Li, 202115 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

17 |

Liu, 202116 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

18 |

Omar, 202117 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

19 |

Taylor, 202118 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

20 |

Tribuddharat, 202119 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

21 |

Wang, 202120 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

22 |

Chui, 202021 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

23 |

Fischer, 202022 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

24 |

Martin, 202023 |

Postoperative GDFT |

|

25 |

Cesur, 201924 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

26 |

Coeckelenbergh, 201925 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

27 |

Bahlmann, 201826 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

28 |

Calvo-Vecino, 201827 |

Duplicate |

|

29 |

Gerent, 201828 |

Postoperative GDFT |

|

30 |

Liu, 201829 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

31 |

Myles, 201830 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

32 |

Yin, 201831 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

33 |

Kaufmann, 201732 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

34 |

Liang, 201733 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

35 |

Xu, 201734 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

36 |

Broch, 201635 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

37 |

Deschamps, 201636 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

38 |

Kassim, 201637 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

39 |

Li, 201638 |

Not available through library |

|

40 |

Schmid, 201639 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

41 |

Ackland, 201540 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

42 |

Benes, 201541 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

43 |

Correa-Gallego, 201542 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

44 |

Funk, 201543 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

45 |

Jammer, 201544 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

46 |

Lai, 201545 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

47 |

Mikor, 201546 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

48 |

Cowie, 201447 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

49 |

Zeng, 201448 |

Retracted |

|

50 |

Chattopadhyay, 201349 |

No randomisation |

|

51 |

Goepfert, 201350 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

52 |

Jones, 201351 |

Postoperative GDFT |

|

53 |

Salzwedel, 201352 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

54 |

Challand, 201253 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

55 |

Cohn, 201054 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

56 |

Rhodes, 201055 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

57 |

Van Der Linden, 201056 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

58 |

Senagore, 200957 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

59 |

Harten, 200858 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

60 |

Chytra, 200759 |

Postoperative GDFT |

|

61 |

Donati, 200760 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

62 |

Murkin, 200761 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

63 |

Lobo, 200662 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

64 |

Noblett, 200663 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

65 |

Pearse, 200564 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

66 |

Pearse, 200564 |

Duplicate |

|

67 |

McKendry, 200465 |

Postoperative GDFT |

|

68 |

Conway, 200266 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

69 |

Ueno, 199867 |

Postoperative GDFT |

|

70 |

Bender, 199768 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

71 |

Sincleair, 199769 |

Postoperative GDFT |

|

72 |

Boyd, 199370 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

73 |

Joyce, 199071 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

1. Feng A, Lu P, Yang Y, Liu Y, Ma L, Lv J. Effect of goal-directed fluid therapy based on plasma colloid osmotic pressure on the postoperative pulmonary complications of older patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21(1):67. Published 2023 Feb 28. doi:10.1186/s12957-023-02955-5. 2. Hrdy O, Duba M, Dolezelova A, et al. Effects of goal-directed fluid management guided by a non-invasive device on the incidence of postoperative complications in neurosurgery: a pilot and feasibility randomized controlled trial. Perioper Med (Lond). 2023;12(1):32. Published 2023 Jul 5. doi:10.1186/s13741-023-00321-3. 3. Ji J, Ma Q, Tian Y, et al. Effect of inferior vena cava respiratory variability-guided fluid therapy after laparoscopic hepatectomy: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Chin Med J (Engl). 2023;136(13):1566-1572. Published 2023 Jul 5. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000002484. 4. Ma H, Li X, Wang Z, et al. The effect of intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy combined with enhanced recovery after surgery program on postoperative complications in elderly patients undergoing thoracoscopic pulmonary resection: a prospective randomized controlled study. Perioper Med (Lond). 2023;12(1):33. Published 2023 Jul 10. doi:10.1186/s13741-023-00327-x. 5. Schaller SJ, Fuest K, Ulm B, et al. Goal-directed Perioperative Albumin Substitution Versus Standard of Care to Reduce Postoperative Complications - A Randomized Clinical Trial (SuperAdd Trial) [published online ahead of print, 2023 Jul 21]. Ann Surg. 2023;10.1097/SLA.0000000000006030. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000006030. 6. Chui J, Craen R, Dy-Valdez C, et al. Early Goal-directed Therapy During Endovascular Coiling Procedures Following Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Pilot Prospective Randomized Controlled Study. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2022;34(1):35-43. doi:10.1097/ANA.0000000000000700. 7. Froghi F, Gopalan V, Anastasiou Z, Koti R, Gurusamy K, Eastgate C, et al. Effect of postoperative goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) on organ function after orthotopic liver transplantation: Secondary outcome analysis of the COLT randomised control trial. Int J Surg. 2022;99:106265. 8. Hokenek UD, Gurler HK, Saracoglu A, Kale A, Saracoglu KT. Pleth Variability Index Guided Volume Optimisation in Major Gynaecologic Surgery. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2022;32(8):980-6. 9. Mishra N, Rath GP, Bithal PK, Chaturvedi A, Chandra PS, Borkar SA. Effect of Goal-Directed Intraoperative Fluid Therapy on Duration of Hospital Stay and Postoperative Complications in Patients Undergoing Excision of Large Supratentorial Tumors. Neurol India. 2022;70(1):108-114. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.336329. 10. Turkut N, Altun D, Canbolat N, Uzuntürk C, Şen C, Çamcı AE. Comparison of Stroke Volume Variation-based goal-directed Therapy Versus Standard Fluid Therapy in Patients Undergoing Head and Neck Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Study. Balkan Med J. 2022;39(5):351-357. doi:10.4274/balkanmedj.galenos.2022.2022-1-88. 11. Wongtangman K, Wilartratsami S, Hemtanon N, Tiviraj S, Raksakietisak M. Goal-Directed Fluid Therapy Based on Pulse-Pressure Variation Compared with Standard Fluid Therapy in Patients Undergoing Complex Spine Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Asian Spine J. 2022;16(3):352-60. 12. Bloria SD, Panda NB, Jangra K, Bhagat H, Mandal B, Kataria K, et al. Goal-directed Fluid Therapy Versus Conventional Fluid Therapy During Craniotomy and Clipping of Cerebral Aneurysm: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2022;34(4):407-14. 13. Cho HJ, Huang YH, Poon KS, Chen KB, Liao KH. Perioperative hemodynamic optimisation in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy using stroke volume variation to reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17(9):1549-57. 14. Li M, Peng M. Prospective comparison of the effects of intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy and restrictive fluid therapy on complications in thoracoscopic lobectomy. J Int Med Res. 2021;49(12):3000605211062787. 15. Liu Y, Chen G, Gao J, Chi M, Mao M, Shi Y, et al. Effect of different levels of stroke volume variation on the endothelial glycocalyx of patients undergoing colorectal surgery: A randomised clinical trial. Exp Physiol. 2021;106(10):2124-32. 16. Omar IH, Okasha AS, Ahmed AM, Saleh RS. Goal Directed Fluid Therapy based on Stroke Volume Variation and Oxygen Delivery Index using Electrical Cardiometry in patients undergoing Scoliosis Surgery. Egyptian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2021;37(1):241-7. 17. Taylor RJ, Patel R, Wolf BJ, Stoll WD, Hornig JD, Skoner JM, et al. Intraoperative vasopressors in head and neck free flap reconstruction. Microsurgery. 2021;41(1):5-13. 18. Tribuddharat S, Sathitkarnmanee T, Ngamsangsirisup K, Nongnuang K. Efficacy of Intraoperative Hemodynamic Optimization Using FloTrac/EV1000 Platform for Early Goal-Directed Therapy to Improve Postoperative Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Graft with Cardiopulmonary Bypass: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Med Devices (Auckl). 2021;14:201-9. 19. Wang X, Duan Y, Gao Z, Gu J. Effect of Goal-directed Fluid Therapy on the Shedding of the Glycocalyx Layer in Retroperitoneal Tumour Resection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2021;31(10):1179-85. 20. Chui J, Craen R, Dy-Valdez C, Alamri R, Boulton M, Pandey S, et al. Early Goal-directed Therapy During Endovascular Coiling Procedures Following Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Pilot Prospective Randomized Controlled Study. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2022;34(1):35-43. 21. Fischer MO, Lemoine S, Tavernier B, Bouchakour CE, Colas V, Houard M, et al. Individualised Fluid Management Using the Pleth Variability Index: A Randomised Clinical Trial. Anesthesiology. 2020;133(1):31-40. 22. Martin D, Koti R, Gurusamy K, Longworth L, Singh J, Froghi F, et al. The cardiac output optimisation following liver transplant (COLT) trial: a feasibility randomised controlled trial. HPB (Oxford). 2020;22(8):1112-20. 23. Cesur S, Cardakozu T, Kus A, Turkyilmaz N, Yavuz O. Comparison of conventional fluid management with PVI-based goal-directed fluid management in elective colorectal surgery. J Clin Monit Comput. 2019;33(2):249-57. 24. Coeckelenbergh S, Delaporte A, Ghoundiwal D, Bidgoli J, Fils JF, Schmartz D, et al. Pleth variability index versus pulse pressure variation for intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy in patients undergoing low-to-moderate risk abdominal surgery: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019;19(1):34. 25. Bahlmann H, Hahn RG, Nilsson L. Pleth variability index or stroke volume optimisation during open abdominal surgery: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18(1):115. 26. Calvo-Vecino JM, Ripolles-Melchor J, Mythen MG, Casans-Frances R, Balik A, Artacho JP, et al. Effect of goal-directed haemodynamic therapy on postoperative complications in low-moderate risk surgical patients: a multicentre randomised controlled trial (FEDORA trial). Br J Anaesth. 2018;120(4):734-44. 27. Gerent ARM, Almeida JP, Fominskiy E, Landoni G, de Oliveira GQ, Rizk SI, et al. Effect of postoperative goal-directed therapy in cancer patients undergoing high-risk surgery: a randomised clinical trial and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):133. 28. Liu TJ, Zhang JC, Gao XZ, Tan ZB, Wang JJ, Zhang PP, et al. Clinical research of goal-directed fluid therapy in elderly patients with radical resection of bladder cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 2018;14(Supplement):S173-S9. 29. Myles PS, Bellomo R, Corcoran T, Forbes A, Peyton P, Story D, et al. Restrictive versus Liberal Fluid Therapy for Major Abdominal Surgery. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(24):2263-74. 30. Yin K, Ding J, Wu Y, Peng M. Goal-directed fluid therapy based on non-invasive cardiac output monitor reduces postoperative complications in elderly patients after gastrointestinal surgery: A randomised controlled trial. Pak J Med Sci. 2018;34(6):1320-5. 31. Kaufmann KB, Stein L, Bogatyreva L, Ulbrich F, Kaifi JT, Hauschke D, et al. Oesophageal Doppler guided goal-directed haemodynamic therapy in thoracic surgery - a single centre randomised parallel-arm trial. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118(6):852-61. 32. Liang M, Li Y, Lin L, Lin X, Wu X, Gao Y, et al. Effect of goal-directed fluid therapy on the prognosis of elderly patients with hypertension receiving plasmakinetic energy transurethral resection of prostate. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2017;10(1):1290-6. 33. Xu H, Shu SH, Wang D, Chai XQ, Xie YH, Zhou WD. Goal-directed fluid restriction using stroke volume variation and cardiac index during one-lung ventilation: a randomised controlled trial. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(9):2992-3004. 34. Broch O, Carstens A, Gruenewald M, Nischelsky E, Vellmer L, Bein B, et al. Non-invasive hemodynamic optimisation in major abdominal surgery: a feasibility study. Minerva Anestesiol. 2016;82(11):1158-69. 35. Deschamps A, Hall R, Grocott H, Mazer CD, Choi PT, Turgeon AF, et al. Cerebral Oximetry Monitoring to Maintain Normal Cerebral Oxygen Saturation during High-risk Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Feasibility Trial. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(4):826-36. 36. Kassim DY, Esmat IM. Goal directed fluid therapy reduces major complications in elective surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm: Liberal versus restrictive strategies. Egyptian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2016;32(2):167-73. 37. Li S, Ma Q, Yang Y, Lu J, Zhang Z, Jin M, et al. Novel Goal-Directed Hemodynamic Optimization Therapy Based on Major Vasopressor during Corrective Cardiac Surgery in Patients with Severe Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: A Pilot Study. Heart Surg Forum. 2016;19(6):E297-E302. 38. Schmid S, Kapfer B, Heim M, Bogdanski R, Anetsberger A, Blobner M, et al. Algorithm-guided goal-directed haemodynamic therapy does not improve renal function after major abdominal surgery compared to good standard clinical care: a prospective randomised trial. Crit Care. 2016;20:50. 39. Ackland GL, Iqbal S, Paredes LG, Toner A, Lyness C, Jenkins N, et al. Individualised oxygen delivery targeted haemodynamic therapy in high-risk surgical patients: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled, mechanistic trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(1):33-41. 40. Benes J, Haidingerova L, Pouska J, Stepanik J, Stenglova A, Zatloukal J, et al. Fluid management guided by a continuous non-invasive arterial pressure device is associated with decreased postoperative morbidity after total knee and hip replacement. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;15:148. 41. Correa-Gallego C, Tan KS, Arslan-Carlon V, Gonen M, Denis SC, Langdon-Embry L, et al. Goal-Directed Fluid Therapy Using Stroke Volume Variation for Resuscitation after Low Central Venous Pressure-Assisted Liver Resection: A Randomised Clinical Trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(2):591-601. 42. Funk DJ, HayGlass KT, Koulack J, Harding G, Boyd A, Brinkman R. A randomised controlled trial on the effects of goal-directed therapy on the inflammatory response open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):247. 43. Jammer I, Tuovila M, Ulvik A. Stroke volume variation to guide fluid therapy: is it suitable for high-risk surgical patients? A terminated randomised controlled trial. Perioper Med (Lond). 2015;4:6. 44. Lai CW, Starkie T, Creanor S, Struthers RA, Portch D, Erasmus PD, et al. Randomised controlled trial of stroke volume optimisation during elective major abdominal surgery in patients stratified by aerobic fitness. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115(4):578-89. 45. Mikor A, Trasy D, Nemeth MF, Osztroluczki A, Kocsi S, Kovacs I, et al. Continuous central venous oxygen saturation assisted intraoperative hemodynamic management during major abdominal surgery: a randomised, controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;15:82. 46. Cowie DA, Nazareth J, Story DA. Cerebral oximetry to reduce perioperative morbidity. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2014;42(3):310-4. 47. Zeng K, Li Y, Liang M, Gao Y, Cai H, Lin C. The influence of goal-directed fluid therapy on the prognosis of elderly patients with hypertension and gastric cancer surgery. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:2113-9. 48. Chattopadhyay S, Mittal S, Christian S, Terblanche AL, Patel A, Biliatis I, et al. The role of intraoperative fluid optimisation using the esophageal Doppler in advanced gynecological cancer: early postoperative recovery and fitness for discharge. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23(1):199-207. 49. Goepfert MS, Richter HP, Zu Eulenburg C, Gruetzmacher J, Rafflenbeul E, Roeher K, et al. Individually optimised hemodynamic therapy reduces complications and length of stay in the intensive care unit: a prospective, randomised controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2013;119(4):824-36. 50. Jones C, Kelliher L, Dickinson M, Riga A, Worthington T, Scott MJ, et al. Randomised clinical trial on enhanced recovery versus standard care following open liver resection. Br J Surg. 2013;100(8):1015-24. 51. Salzwedel C, Puig J, Carstens A, Bein B, Molnar Z, Kiss K, et al. Perioperative goal-directed hemodynamic therapy based on radial arterial pulse pressure variation and continuous cardiac index trending reduces postoperative complications after major abdominal surgery: a multi-center, prospective, randomised study. Crit Care. 2013;17(5):R191. 52. Challand C, Struthers R, Sneyd JR, Erasmus PD, Mellor N, Hosie KB, et al. Randomised controlled trial of intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy in aerobically fit and unfit patients having major colorectal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108(1):53-62. 53. Cohn SM, Pearl RG, Acosta SM, Nowlin MU, Hernandez A, Guta C, et al. A prospective randomised pilot study of near-infrared spectroscopy-directed restricted fluid therapy versus standard fluid therapy in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. Am Surg. 2010;76(12):1384-92. 54. Rhodes A, Cecconi M, Hamilton M, Poloniecki J, Woods J, Boyd O, et al. Goal-directed therapy in high-risk surgical patients: a 15-year follow-up study. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(8):1327-32. 55. Van der Linden PJ, Dierick A, Wilmin S, Bellens B, De Hert SG. A randomised controlled trial comparing an intraoperative goal-directed strategy with routine clinical practice in patients undergoing peripheral arterial surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27(9):788-93. 56. Senagore AJ, Emery T, Luchtefeld M, Kim D, Dujovny N, Hoedema R. Fluid management for laparoscopic colectomy: a prospective, randomised assessment of goal-directed administration of balanced salt solution or hetastarch coupled with an enhanced recovery program. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(12):1935-40. 57. Harten J, Crozier JE, McCreath B, Hay A, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, et al. Effect of intraoperative fluid optimisation on renal function in patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery: a randomised controlled pilot study (ISRCTN 11799696). Int J Surg. 2008;6(3):197-204. 58. Chytra I, Pradl R, Bosman R, Pelnar P, Kasal E, Zidkova A. Esophageal Doppler-guided fluid management decreases blood lactate levels in multiple-trauma patients: a randomised controlled trial. Crit Care. 2007;11(1):R24. 59. Donati A, Loggi S, Preiser JC, Orsetti G, Munch C, Gabbanelli V, et al. Goal-directed intraoperative therapy reduces morbidity and length of hospital stay in high-risk surgical patients. Chest. 2007;132(6):1817-24. 60. Murkin J, Adams S. novick RJ, Quantz M, Bainbridge D, iglesias i, Cleland A, Schaefer B, irwin B, Fox S: Monitoring brain oxygen saturation during coronary bypass surgery: A randomised, prospective study. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:51-8. 61. Lobo SM, Lobo FR, Polachini CA, Patini DS, Yamamoto AE, de Oliveira NE, et al. Prospective, randomised trial comparing fluids and dobutamine optimisation of oxygen delivery in high-risk surgical patients [ISRCTN42445141]. Crit Care. 2006;10(3):R72. 62. Noblett SE, Snowden CP, Shenton BK, Horgan AF. Randomised clinical trial assessing the effect of Doppler-optimised fluid management on outcome after elective colorectal resection. Br J Surg. 2006;93(9):1069-76. 63. Pearse R, Dawson D, Fawcett J, Rhodes A, Grounds RM, Bennett ED. Early goal-directed therapy after major surgery reduces complications and duration of hospital stay. A randomised, controlled trial [ISRCTN38797445]. Crit Care. 2005;9(6):R687-93. 64. McKendry M, McGloin H, Saberi D, Caudwell L, Brady AR, Singer M. Randomised controlled trial assessing the impact of a nurse delivered, flow monitored protocol for optimisation of circulatory status after cardiac surgery. BMJ. 2004;329(7460):258. 65. Conway DH, Mayall R, Abdul-Latif MS, Gilligan S, Tackaberry C. Randomised controlled trial investigating the influence of intravenous fluid titration using oesophageal Doppler monitoring during bowel surgery. Anaesthesia. 2002;57(9):845-9. 66. Ueno S, Tanabe G, Yamada H, Kusano C, Yoshidome S, Nuruki K, et al. Response of patients with cirrhosis who have undergone partial hepatectomy to treatment aimed at achieving supranormal oxygen delivery and consumption. Surgery. 1998;123(3):278-86. 67. Bender JS, Smith-Meek MA, Jones CE. Routine pulmonary artery catheterisation does not reduce morbidity and mortality of elective vascular surgery: results of a prospective, randomised trial. Ann Surg. 1997;226(3):229-36; discussion 36-7. 68. Sinclair S, James S, Singer M. Intraoperative intravascular volume optimisation and length of hospital stay after repair of proximal femoral fracture: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1997;315(7113):909-12. 69. Boyd O, Grounds RM, Bennett ED. A randomised clinical trial of the effect of deliberate perioperative increase of oxygen delivery on mortality in high-risk surgical patients. JAMA. 1993;270(22):2699-707. 70. Joyce WP, Provan JL, Ameli FM, McEwan MM, Jelenich S, Jones DP. The role of central haemodynamic monitoring in abdominal aortic surgery. A prospective randomised study. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1990;4(6):633-6. |

||

Study characteristics

|

Study |

Type of surgery |

Goal directed fluid therapy |

Conventional fluid therapy |

Riskof Bias |

Definition SSI |

||

|

Tools and goals |

Intervention |

Tools and goals |

Intervention |

||||

|

Aaen 2021 |

Emergency surgery for obstructive bowel disease or GI perforation |

Arterial line (FloTrac/EV1000)

|

Colloids |

- |

Crystalloids, colloids, vasopressors |

Low |

Superficial wound infection: Wound rupture, surgical revision or medical treatment |

|

SV increase <10%, MAP >65 mmHg |

Vasopressors |

MAP >65 mmHg, UO >0.5 ml/kg/h |

Vasopressors |

||||

|

Arslan-Carlon 2020 |

Open radical cystectomy |

Arterial line (FloTrac/Vigileo)

|

Crystalloids, colloids |

- |

Colloids, RBC |

Low |

NI |

|

SV increase ≤10%, SVV <8% MAP ≥60 mmHg, CI 2.5 |

Inotropes, vasoconstrictors |

Hb >7 mg/dl

|

Ephedrine, phenylephrine |

||||

|

Bahlmann 2019 |

Open thoracotomy |

Arterial line (FloTrac/Vigileo) |

Crystalloids, colloids, fresh frozen plasma, RBC |

- |

Colloids |

SC |

Superficial SSI: Local inflammatory signs and specific antibiotic treatment |

|

SV <10%, CI ≥2.5 l/min/m2, MAP >65 mmHg |

Dobutamine, phenylephrine, norepinephrine |

Discretion anaesthetist (Hb >90/100 g/l) |

Dobutamine, phenylephrine, norepinephrine |

||||

|

Bartha 2014 |

Proximal femoral fracture surgery |

Arterial line (LiDCO) |

Colloids

|

- |

Crystalloids |

Low |

Deep and/or superficial with purulent exudate and treated by antibiotic |

|

SV <10% increase, DO2I ≥600 ml/min, SBP decrease <30% |

Dobutamine |

SBP decrease <30% |

Vasoactive substances |

||||

|

Benes 2010 |

Major abdominal surgery >120 min (colorectal or pancreatic resections, intra-abdominal vascular surgery) |

Arterial line (FloTrac/Vigileo)

|

Colloid |

- |

Crystalloids, colloids |

SC |

CDC |

|

SVV <10% , CVP >15 mmHg, CI 2.5-4.0 l/min/m2, SAP >90 mmHg, MAP >65 mmHg |

Dobutamine, ephedrine, norepinephrine |

MAP >65 mmHg, HR<100 bpm, CVP 8-15 mmHg, UO>0.5 ml/kg/h |

Vasoactive substances |

||||

|

Bisgaard 2013 – Trauma |

Open elective lower limb arterial surgery |

Arterial line (LiDCO)

|

Colloids |

Arterial line |

Fluid therapy |

SC |

NI |

|

SVI increase >10%, DO2I <600 ml/min/m2, HR <100 or <20% above baseline, acute hypotension |

Phenylephrine, ephedrine, |

MAP 60–100 mmHg, SaO2 > 94%, Hb ≥ 9.3 g/l, Temp > 36.5°C, HR <100 or <20% above baseline |

Phenylephrine, ephedrine |

||||

|

Bisgaard 2013 – Vascular

|

Open elective abdominal aortic surgery |

Arterial line (LiDCOplus)

|

Colloids |

Arterial line |

Colloids, RBCs |

SC |

NI |

|

SVI increase >10%, DO2I <600 ml/min/m2, MAP >65 mmHg or >70% of baseline |

Phenylephrine, ephedrine |

MAP >65 mmHg or >70% of baseline |

Phenylephrine, ephedrine, dobutamine |

||||

|

Brandstrup 2012 |

Colorectal resection, open and laparoscopic |

Oesophageal Doppler (CardioQ) |

Colloids |

- |

Colloids

|

SC |

NI |

|

SV increase <10% |

Phenylephrine, ephedrine

|

MAP >60 mmHg |

Phenylephrine, ephedrine |

||||

|

Calvo-Vecino 2018 |

Abdominal, urological, gynaecological, orthopaedic surgery (estimated duration ≥2h, blood loss >15%, or ≥2 packs RBC) |

Oesophageal Doppler (CardioQ)

|

Crystalloids, colloids |

- |

Discretion anaesthetist: crystalloids, colloids |

Low |

Presumably CDC |

|

SV <10% increase, MAP >65 mmHg, CI >2.5 l/min/m2 |

Vasopressors, inotropes |

Avoid extremes of clinical practice misalignment |

Discretion anaesthetist: dobutamine, norepinephrine |

||||

|

Cecconi 2011 |

Total hip arthroplasty |

Arterial line (FloTrac/Vigileo)

|

Crystalloids, colloids |

- |

Colloids |

SC |

¶ |

|

SV increase <10%, DO2I ≥600ml/min/m2 |

Dobutamine |

Discretion anaesthetist MAP >65 mmHg |

Ephedrine |

||||

|

Cheng 2020 |

Cardiac surgery (valvular surgery and/or coronary artery bypass grafting with CPB) |

Arterial line (LiDCOrapid), INVOS, BIS |

Crystalloids, RBCs

|

INVOS, BIS |

Crystalloids, RBCs

|

Low |

NI |

|

rScO2 decline <20%, MAP <20% decline, CI ≥2 l/min/m2, BIS 40-45/45-60 |

Norepinephrine, dobutamine, propofol |

HR 60-100 bpm, ScVO2 >70%, lactate <3 mmol/L, Ht >28%, UO >0.5 mL/kg/h, MAP = 65mmHg |

Norepinephrine, dobutamine |

||||

|

Colantonio 2015 |

Open peritonectomy and HIPEC |

Arterial line (FloTrac/Vigileo)

|

Colloids |

CVC, arterial line |

Colloids |

SC |

NI |

|

CI ≥2.5 l/min/m2, SVI ≥35ml/m2, SVV <15% |

Dobutamine |

MAP 65-90 mmHg or >70% pre-induction, CVP >15 mmHg, diuresis >1 ml/kg/h |

Dopamine |

||||

|

Davies 2019 |

Emergency proximal femoral fracture surgery |

Finger cuff (Clearsight system)

|

Colloids |

- |

Crystalloids |

Low |

Wound infection: Deep and/or superficial with purulent exudate and treated by antibiotics |

|

SVV <10%, MAP within 30% of baseline |

Phenylephrine, metaraminol |

Discretion anaesthetist |

Inotropes, vasopressors |

||||

|

De Waal 2021 |

High risk abdominal surgery (esophagectomy, pancreaticoduode- nectomy, open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, major abdominal resections for soft tissue malignancy) |

Arterial line (FloTrac/Vigileo)

|

Crystalloids, colloids |

Arterial and central venous line |

Crystalloids, colloids |

SC |

NI |

|

CI ≥ 2.8/2.6/2.4 or <10% increase l min/m2, SVV <12%

|

Inotropes |

HR <100 min or ≤25% above individual baseline MAP ≥ 60 mmHg or ≤25% below individual baseline, saturation ≥ 95% |

Vasopressors |

||||

|

Diaper 2021 |

Major abdominal, urological, or vascular surgery via open laparotomy (≥2h)

|

Arterial line (LiDCO)

|

Crystalloids, colloids |

Arterial line (LiDCO)

|

Crystalloids, colloids |

Low |

CD ³2 |

|

SVI <10%, MAP decrease <20% or >65-70 mmHg, PPV <10% |

Ephedrine, phenylephrine, norepinephrine |

MAP >65-70 mmHg, fluid losses, hypovolemia, metabolic acidosis |

Ephedrine, phenylephrine, noradrenaline |

||||

|

Elgendy 2017 |

Major abdominal surgery (duration >120 min or blood loss >20%) |

Arterial line (FloTrac/Vigileo)

|

Colloids |

- |

Colloids |

SC |

NI |

|

SVV <12%, CI >2.5, MAP >65mmHg |

Dobutamine, norepinephrine |

60 and 90 mmHg with CVP in range of 8–12 mmHg and UO of >0.5 ml/kg/h |

Dobutamine, norepinephrine |

||||

|

Forget 2010 |

Gastrointestinal of hepato-biliary surgery |

Pulse oximeter (Masimo)

|

Colloids |

- |

Colloids |

Low |

NI |

|

PVI <13%, MAP >65 mmHg |

Norepinephrine |

Blood loss <50 ml, MAP >65 mmHg, CVP >6 mmHg |

Norepinephrine |

||||

|

Gan 2002 |

Major elective general, urologic, and gynaecologic surgery (blood loss >500 ml) |

Oesophageal Doppler |

Colloids

|

- |

Fluids |

SC |

NI |

|

FTc >350 ms, SV increase <10%

|

- |

UO >0.5 ml/kg/h, HR <120% baseline or <110 bpm, SBP decrease <20% baseline or >90 mmHg, CVP decrease <20% of baseline |

- |

||||

|

Göçmen 2023 |

Proximal femoral nail surgery |

Arterial line, MostcarTM monitor

SVV<13%, PPV<10%, CI>2.5L/min/m2, MAP>65 mmHg

|