Deurbewegingen

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het effect van het aantal deurbewegingen in de operatiekamer gedurende de operatie op het risico van postoperatieve wondinfecties bij chirurgische patiënten?

Aanbeveling

Het beperken van het aantal deuropeningen in de operatiekamer is mogelijk geassocieerd met een vermindering van postoperatieve wondinfecties; het relatieve effect van deuropeningen is minimaal.

Vanuit een gedragscode perspectief is het raadzaam om het aantal aanwezigen in de operatiekamer en (deur)bewegingen te beperken om rust te creëren.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Bij de nieuwste inzichten voor de GRADE methodologie wordt rekening gehouden met klinische relevantie van een effect, waarbij voor- en nadelen tegen elkaar af worden gewogen. Toelichting op de gehanteerde methode is te vinden in de GRADE assessment onder het tabblad "Evidence tabellen”. Uit deze door Groenen et al. gehanteerde methode volgt een zeer lage bewijskracht voor een mogelijk effect op POWI bij het beperken van het aantal deuropeningen per uur in de operatiekamer; het relatieve effect van deuropeningen is minimaal, maar bij een langere operatieduur en een basaal hoog risico op POWI lijkt het cumulatieve effect wel van belang.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Niet van toepassing.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er is geen kosteneffectiviteitsanalyse beschikbaar.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er zijn geen zorgen over de aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Deze individuele patiënt data meta-analyse laat een mogelijk effect op het verminderen van postoperatieve wondinfecties zien bij het beperken van het aantal deuropeningen in de operatiekamer. Het relatieve effect van deuropeningen is minimaal en het cumulatieve effect lijkt van minder belang bij een basaal laag risico op postoperatieve wondinfectie, bijvoorbeeld bij schone electieve chirurgie bij een patiënt met ASA-score 1 en een beperkte operatieduur. Echter lijkt het cumulatieve effect wel van belang bij een langere operatieduur en een basaal hoog risico op postoperatieve wondinfectie (zie Two example patients onder het tabblad "Evidence tabellen”).

Daarnaast heeft rust binnen de OK een positieve invloed op de kwaliteit van het operatieproces. Het aantal aanwezigen en het aantal bewegingen kunnen deze rust negatief beïnvloeden. Om deze reden wordt een OK-gedragscode geadviseerd waarin afspraken hierover zijn vastgelegd. Zie hiervoor de richtlijn Luchtbehandeling in operatiekamers en behandelkamers. De werkgroep wil echter benadrukken dat bovenstaande geen indicatie is voor een beleid waarbij de deuren volledig gesloten blijven tijdens de operatie.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De invloed van deuropeningen in de operatiekamer op het optreden van postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI’s) is al enkele jaren een controversieel onderwerp. Veel bundels voor de preventie van POWI’s zijn onderzocht, waarbij een beperkt aantal deuropeningen als een element van de bundel wordt beschouwd.1,2 Echter, het bewijs lijkt beperkt en zeer heterogeen.15 Eerdere studies richtten zich op luchtpartikels als surrogaat voor POWI, terwijl recent bewijs suggereert dat luchtverontreiniging mogelijk niet gerelateerd is aan contaminatie van de wond of POWI.3,4 Aan de andere kant wordt gedacht dat het aantal deuropeningen dient als een surrogaatmarker voor discipline en hygiëne in de operatiekamer. Sommige studies suggereren dat een afname van het aantal deuropeningen de aandacht in de operatiekamer verhoogt.5,6

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Surgical site infections (SSI)

|

Very low GRADE |

Every extra door opening per hour may increase SSI risk in surgical patients, but the evidence is very uncertain. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

We included eight observational studies in our systematic review and IPDMA. The study characteristics of the eight studies are listed in Table 1. The primary outcome of the studies was SSI (n = 4), Colony Forming Unit (CFU) (n = 3) and operative workflow and efficiency (n = 1). Type of surgery and CDC wound classification differed per study. Table 2 shows the baseline and surgical characteristics of the IPD.

Results

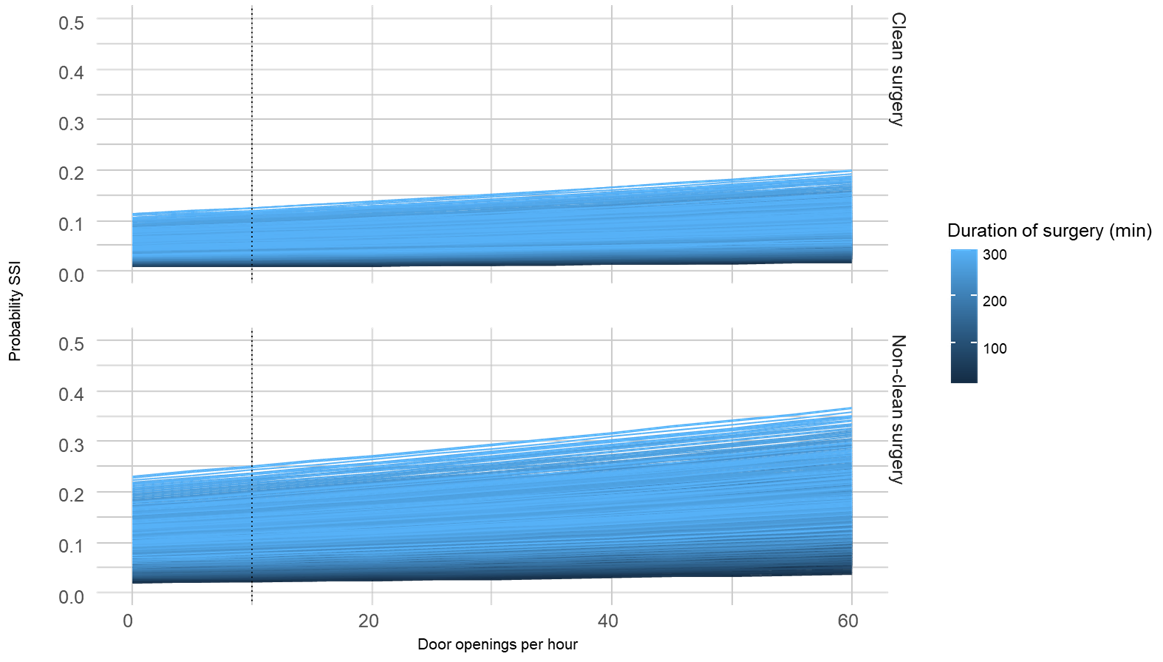

In total, 4412 patients were included in the systematic review, reporting 265 SSI corresponding to an overall incidence of 6.0%. Table 3 shows the effect estimates with corresponding 95% CI of the analysis of the primary outcome. After adjustment for confounding in the logistic regression model with mixed-effects, there was an increase in SSI risk for every additional door opening per hour (OR 1.011 [95% CI 1.004 – 1.018]). The variables included in the final model were CDC wound classification, emergency surgery, implantation of a foreign body, income level of the country where the study was conducted, and procedure duration. To account for clustering of patients within studies, a term was added to the model that varies across studies via a random effect. The probability of SSI in relation to the number of door openings per hour by duration of surgery and CDC wound classification is shown under the the "evidence tabellen" tab. The two example patients under the "evidence tabellen" tab shows the probability of SSI in relation to the number of door openings per hour for two example patients.

Subgroup- and sensitivity analyses

The effect of the number of door openings per hour on SSI was not different for non-clean versus clean surgery (OR interaction term 0.995 [95% CI 0.981 – 1.009]) and implantation of a foreign body versus no implantation of a foreign body (OR interaction term 0.981 [95% CI 0.952 – 1.011]). For the subgroup analysis based on income level of the country where the study was conducted, the OR within-study interaction term cannot be calculated. The OR across-study interaction for high versus low-income countries was 0.976 [95% CI 0.955 – 0.998]. The sensitivity analysis excluding studies with high risk of bias showed comparable results to the main analysis (OR 1.011 [95% CI 1.004 – 1.019]).

Level of evidence of the literature

Full evaluation of the body of evidence and considerations for grading are detailed in the GRADE assessment under the tab "evidence tabellen". GRADE assessment, incorporating minimally important difference, resulted in a very low certainty of evidence for the primary outcome SSI.

Table 1

Study characteristics

- Bediako-Bowan A, Owusu E, Debrah S, Kjerulf A, Newman MJ, Kurtzhals JAL, Molbak K. Surveillance of surgical site infection in a teaching hospital in Ghana: a prospective cohort study. J Hosp Infect. Mar 2020;104(3):321-327. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.004

|

Study (year) |

Study design |

Type of surgery |

Wound class* |

Type of ventilation |

Country |

Reported outcomes |

SSI definition: |

N (original study)a |

SSI/N (%) (current analysis)a |

Door openings per hour‡ |

Follow-up |

Quality assessment

|

|

Allegranzi 2018

|

Comparative cohort (p)

|

Abdominal, breast, cardiac, general, neuro, thoracic, trauma, urology, vascular surgery, caeserean section

|

1-4 |

NR |

Kenya, Uganda, Zambia

|

Primary: SSI Secondary: mortality |

CDC |

a: 1827 b: 891 c: 1604 |

a: 70/1800 (3.9) |

a: 5.7 (21.1) c: - |

30 days |

Good |

|

Bahethi 2020 |

Cohort (p) |

Free flap reconstruction (otolaryngology)

|

2 |

NR |

USA |

Primary: operative workflow and efficiency Secondary: SSI, reoperation, readmission, length of stay, mortality

|

¶a |

23 |

6/22 (27.3) |

24.5 (6.7) |

30 days |

Poor |

|

Bediako-Bowan 2020

|

Comparative cohort (p) |

Abdominal surgery |

1-4 |

Non-laminar flow

|

Ghana |

Primary: SSI Secondary: radiological/surgical intervention, HAI, mortality |

¶b |

358 |

58/358 (16.2) |

55.9 (23.0) |

30 days |

Good |

|

De Jonge 2021 |

Comparative cohort (p) |

Abdominal, trauma, vascular, gynaecology, hernia surgery

|

1-4 |

Laminar flow |

Netherlands |

Primary: SSI (superficial or deep) |

CDC |

3001 |

61/825 (7.4) |

21.7 (18.9) |

30 days |

Good |

|

Mathijssen 2016

|

Comparatvie cohort (p)

|

Hip revision surgery |

1 |

Turbulent flow |

Netherlands |

Primary: CFU |

¶c |

70 |

2/68 (2.9) |

3 (4.4) |

13 months |

Good |

|

Perez 2018

|

Comparative cohort (p)

|

Orthopedic, general surgery

|

NA |

Laminar flow |

USA |

Primary: CFU |

CDC |

48 |

0/52 (0) |

23.3 (7.7) |

NR |

Good |

|

Prakken 2011 |

Comparative cohort (p)

|

Mastectomy, colon, aorta surgery

|

1-4 |

NR |

Netherlands |

Primary: SSI |

¶d |

284 |

22/283 (7.8) |

5.3 (2.8) |

30 days /1 year† |

Good |

|

Stauning 2018 + 2020 |

Comparative cohort (p)

|

Elective non-implant surgery

|

1-2 |

Turbulent flow |

Ghana |

Primary: CFU |

CDC |

124 |

11/116 (9.5) |

42.8 (26.0)

|

30 days |

Good |

|

a, Allegranzi part a (follow-up phase); b, Allegranzi part b (sustainability phase); c, Allegranzi part c (baseline phase); CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria; CFU, colony forming units; HAI, hospital-acquired infections; NR, not reported; (p), prospective; SSI, surgical site infection; USA, United States of America * according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria; a Discrepancy in the number of patients between the original study and current analysis is possible due to differing reported outcomes, for example CFU compared to SSI; ‡ In current analysis, result presented in median with interquartile range; † For implantation surgery SSI definitions, other than CDC:

|

||||||||||||

Table 2

Baseline and surgical characteristics of participants included in the primary analysis

|

|

Total |

SSI |

No SSI |

|

|

4412 |

265 |

4147 |

|

Age in years (Mean; IQR) Missing (%) |

45.4 (30.0 – 60.0) 76 (1.7) |

50.0 (35.0 – 64.0) 1 (0.4) |

45.1 (30.0 – 60.0) 75 (1.8) |

|

Sex (%) Male Female Missing |

1549 (35.1) 2790 (63.2) 73 (1.7) |

114 (43.0) 150 (56.6) 1 (0.4)

75 (28.3) 125 (47.2) 54 (20.4) 6 (2.3) 1 (0.4) 4 (1.5) 27.0 (22.7 – 29.8) 140 (52.8)

32 (12.1) 98 (37.0) 135 (50.9)

23 (8.7) 113 (42.6) 129 (48.7)

39 (14.7) 203 (76.6) 23 (8.7)

82 (30.9) 183 (69.1) 0 (0.0)

64 (24.2) 201 (75.8) 0 (0.0) 22.4 (6.1 – 46.7) 0 (0.0) 107 (65 – 164) 0 (0.0) |

1435 (34.6) 2640 (63.7) 72 (1.7) |

|

ASA physical status score (%) I II III IV V Missing |

1830 (41.5) 1815 (41.1) 557 (12.6) 56 (1.3) 14 (0.3) 140 (3.2) |

1755 (42.3) 1690 (40.8) 503 (12.1) 50 (1.2) 13 (0.3) 136 (3.3) |

|

|

BMI (Mean; IQR) Missing (%) |

25.9 (22.5 – 28.3) 3197 (72.5) |

25.8 (22.5 – 28.1) 3057 (73.7) |

|

|

Smoking (%) Active smoking Not smoking Missing |

363 (8.2) 852 (19.3) 3197 (72.5) |

331 (8.0) 754 (18.2) 3062 (73.8) |

|

|

Diabetes mellitus (%) Yes No Missing |

117 (2.7) 1201 (27.2) 3094 (70.1) |

94 (2.3) 1088 (26.2) 2965 (71.5) |

|

|

Implantation of a foreign body (%) Yes No Missing |

693 (15.7) 3373 (76.5) 346 (7.8) |

654 (15.8) 3170 (76.4) 323 (77.9) |

|

|

Emergency surgery (%) Yes No Missing |

1222 (27.7) 3133 (71.0) 57 (1.3) |

1140 (27.5) 2950 (71.1) 57 (1.4) |

|

|

Contamination level (%)* Clean Non-clean Missing |

1828 (41.4) 2525 (57.2) 59 (1.3) |

1764 (42.5) 2324 (56.0) 59 (1.4) |

|

|

Number of door openings per hour (Median; IQR) Missing (%) |

13.9 (3.4 – 31.7) 0 (0.0) |

13.1 (3.3 – 31.0) 0 (0.0) |

|

|

Duration of surgery – min (Median; IQR) Missing (%) |

75 (49 – 120) 0 (0.0) |

73 (48 – 119) 0 (0.0) |

|

|

*According to the Center for Disease Control wound classification. ASA, American Society of Anaesthesiologists; BMI, Body mass index; IQR, inter quartile range; SSI, surgical site infection |

|||

Table 3

Logistic regression model with mixed-effects

A one-step meta-analysis of individual participant data using a random-effects framework to test the effect of the number of door openings per hour on SSI.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

How does the number of door openings in the operating room affect the risk of surgical site infections?

P: Patients undergoing any surgical procedure in the operating room

I: Maximum of X door openings per hour

C: More than X door openings per hour

O: SSI

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered SSI as a critical outcome measure for decision making. The working group defined thresholds for clinically relevant outcomes in accordance with current GRADE guidance and methodology.

Search and select (Methods)

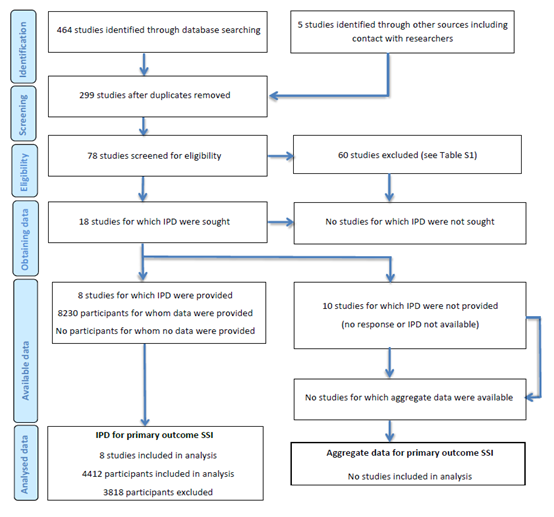

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until January 26, 2023. The detailed search strategy is available on request via https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/. The systematic literature search resulted in 438 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: prospective, retrospective, or randomized trials investigating the effect of door openings in the operating room on the incidence of SSI. Seventy-seven studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 18 studies remained for which data on SSI and door openings during operation were sought. Finally, eight studies were included7-13, 16. Under the "Evidence tabellen” tab, the reasons for excluding the 70 studies during the full-text review are detailed in the table "Reasons for exclusion after full-text review." Additionally, the systematic review flowchart illustrating the study selection process is provided in the same section.

Results

Eight observational studies were included in the systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis (IPDMA). Important study characteristics of the eight studies are shown in Table 1 under the "Samenvatting literatuur" tab. The assessment of the body of evidence is summarized in Quality assessment, following the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale under the "Evidence tabellen” tab.

Referenties

- 1. Crolla RM, van der Laan L, Veen EJ, Hendriks Y, van Schendel C, Kluytmans J. Reduction of surgical site infections after implementation of a bundle of care. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44599. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044599

- 2. van der Slegt J, van der Laan L, Veen EJ, Hendriks Y, Romme J, Kluytmans J. Implementation of a bundle of care to reduce surgical site infections in patients undergoing vascular surgery. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71566. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071566

- 3. Salassa TE, Swiontkowski MF. Surgical attire and the operating room: role in infection prevention. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Sep 3 2014;96(17):1485-92. doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.01133

- 4. Birgand G, Saliou P, Lucet JC. Influence of staff behavior on infectious risk in operating rooms: what is the evidence? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. Jan 2015;36(1):93-106. doi:10.1017/ice.2014.9

- 5. Wheelock A, Suliman A, Wharton R, et al. The Impact of Operating Room Distractions on Stress, Workload, and Teamwork. Ann Surg. Jun 2015;261(6):1079-84. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001051

- 6. Roberts ER, Hider PN, Wells JM, Beasley SW. The frequency and effects of distractions in operating theatres. Anz J Surg. May 2021;91(5):841-846. doi:10.1111/ans.16799

- 7. Bediako-Bowan AAA, Molbak K, Kurtzhals JAL, Owusu E, Debrah S, Newman MJ. Risk factors for surgical site infections in abdominal surgeries in Ghana: emphasis on the impact of operating rooms door openings. Epidemiol Infect. Jul 1 2020;148:e147. doi:10.1017/S0950268820001454

- 8. Bahethi RR, Gold BS, Seckler SG, et al. Efficiency of microvascular free flap reconstructive surgery: An observational study. Am J Otolaryngol. Nov-Dec 2020;41(6):102692. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102692

- 9. Mathijssen NM, Hannink G, Sturm PD, et al. The Effect of Door Openings on Numbers of Colony Forming Units in the Operating Room during Hip Revision Surgery. Surg Infect (Larchmt). Oct 2016;17(5):535-40. doi:10.1089/sur.2015.174

- 10. Perez P, Holloway J, Ehrenfeld L, Cohen S, Cunningham L, Miley GB, Hollenbeck BL. Door openings in the operating room are associated with increased environmental contamination. Am J Infect Control. Aug 2018;46(8):954-956. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2018.03.005

- 11. Prakken FJL-V, G.M.M.; Milinovic, G.; Jacobi, C.E.; Visser, M.J.T.; Steenvoorde, P. Meetbaar verband tussen preventieve interventies en de incidentie van postoperatieve wondinfecties. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde. 2011;155(A3269)

- 12. Stauning MT, Bediako-Bowan A, Andersen LP, Opintan JA, Labi AK, Kurtzhals JAL, Bjerrum S. Traffic flow and microbial air contamination in operating rooms at a major teaching hospital in Ghana. J Hosp Infect. Jul 2018;99(3):263-270. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2017.12.010

- 13. de Jonge SW, Boldingh QJJ, Koch AH, et al. Timing of Preoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis and Surgical Site Infection: TAPAS, An Observational Cohort Study. Ann Surg. Oct 1 2021;274(4):e308-e314. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003634

- 14. Koek MBG, Hopmans TEM, Soetens LC, et al. Adhering to a national surgical care bundle reduces the risk of surgical site infections. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184200. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0184200

- 15. Humphreys, H., Bak, A., Ridgway, E., Wilson, A. P. R., Vos, M. C., Woodhead, K., Haill, C., Xuereb, D., Walker, J. M., Bostock, J., Marsden, G. L., Pinkney, T., Kumar, R., & Hoffman, P. N. (2023). Rituals and behaviours in the operating theatre - joint guidelines of the Healthcare Infection Society and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. The Journal of hospital infection, 140, 165.e1–165.e28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2023.06.009

- 16. Allegranzi, B., Aiken, A. M., Zeynep Kubilay, N., Nthumba, P., Barasa, J., Okumu, G., Mugarura, R., Elobu, A., Jombwe, J., Maimbo, M., Musowoya, J., Gayet-Ageron, A., & Berenholtz, S. M. (2018). A multimodal infection control and patient safety intervention to reduce surgical site infections in Africa: a multicentre, before-after, cohort study. The Lancet. Infectious diseases, 18(5), 507–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30107-5

Evidence tabellen

Flowchart of selected studies

Reasons for exclusion after full text review

|

|

Study |

Reason for exclusion |

|

1 |

Agodi 20151 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

2 |

Anderson 20212 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

3 |

Andersson 20123 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

4 |

Andrews 20144 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

5 |

Arifi 20165 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

6 |

Arnold 20196 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

7 |

Babkin 20077 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

8 |

Birgand 20198 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

9 |

Bohl 20159 |

Duplicate (Bohl 20169) |

|

10 |

Bohl 20169 |

Withdrawn from collaboration |

|

11 |

Borst 198610 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

12 |

Castella 200611 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

13 |

Chakravarthy 201112 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

14 |

Curtis 201813 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

15 |

Cutler 201314 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

16 |

Dalstrom 200815 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

17 |

Downing 202316 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

18 |

Drake 197717 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

19 |

Elgafy 201818 |

Other study design |

|

20 |

Elnour 201819 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

21 |

Feng 201720 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

22 |

Frost 198921 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

23 |

Gomez Palomo 201922 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

24 |

Guajardo 201523 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

25 |

Illingworth 201324 |

Other study design |

|

26 |

Knudsen 202125 |

No response |

|

27 |

Koek 201726 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

28 |

Lansing 202027 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

29 |

Lustenberger 202028 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

30 |

Lynch 200929 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

31 |

Mahakit 2013 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

32 |

Mandal 198030 |

Not retrievable from library |

|

33 |

McConkey 199931 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

34 |

McLees 196732 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

35 |

Montagna 201933 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

36 |

Napoli 201234 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

37 |

Ntumba 201535 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

38 |

Ott 201436 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

39 |

Panahi 201237 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

40 |

Parikh 201038 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

41 |

Patterson 201239 |

Not retrievable from library |

|

42 |

Pedati 201840 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

43 |

Peters 201241 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

44 |

Prakken 201142 |

Abstract of included study (Prakken 201143) |

|

45 |

Pryor 199844 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

46 |

Pyrovolou 201245 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

47 |

Ratkowski 199446 |

Not retrievable from library |

|

48 |

Rezapoor 201847 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

49 |

Ritter 197548 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

50 |

Roberts 202149 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

51 |

Roth 201950 |

Withdrawn from collaboration |

|

52 |

Sadrizadeh 201851 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

53 |

Scaltriti 200752 |

No response |

|

54 |

Schultz 198053 |

Other study design |

|

55 |

Squeri 201954 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

56 |

Szychowski 201155 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

57 |

Taaffe 201856 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

58 |

Taaffe 202057 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

59 |

Tartari 201158 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

60 |

Teter 201759 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

61 |

Tjade 198060 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

62 |

Trouten 197761 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

63 |

Vaishnavi 201962 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

64 |

Vilà Barriuso 201663 |

Not retrievable from library |

|

65 |

Von Dolinger 201064 |

No response |

|

66 |

De Vries 201065 |

Abstract of included study (de Jonge 201966) |

|

67 |

Wang 201967 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

68 |

Wilson 200968 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

69 |

Wolf 196169 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

70 |

Woods 201570 |

Outcome, comparison or setting not of interest |

|

2. Anderson RL, Lipps JA, Pritchard CL, Venkatachalam AM, Olson DM. An operating room audit to examine for patterns of staff entry/exit: pattern sequencing as a method of traffic reduction. J Infect Prevent. Mar 2021;22(2):69-74. doi:10.1177/1757177420967079 3. Andersson AE, Bergh I, Karlsson J, Eriksson BI, Nilsson K. Traffic flow in the operating room: an explorative and descriptive study on air quality during orthopedic trauma implant surgery. Am J Infect Control. Oct 2012;40(8):750-5. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2011.09.015 4. Andrews N, Sutton A, Grayson C. Our 'Bundle' of Joy: Reducing Post Caesarean Infections Using Published Guidelines to Develop and Deploy a Comprehensive Prevention Strategy. American Journal of Infection Control. 2014;42(6):S116-S117. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2014.03.255 5. Arifi AA, H.; Najm, H. Surgical site infection after CABG: Root cause analysis and quality measures recommendation SSI quality improvement project. presented at: Journal Saudi Heart Association; 2016; 6. Arnold FW, Bishop S, Johnson D, et al. Root cause analysis of epidural spinal cord stimulator implant infections with resolution after implementation of an improved protocol for surgical placement. J Infect Prev. Jul 2019;20(4):185-190. doi:10.1177/1757177419844323 7. Babkin Y, Raveh D, Lifschitz M, et al. Incidence and risk factors for surgical infection after total knee replacement. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39(10):890-5. doi:10.1080/00365540701387056 8. Birgand G, Azevedo C, Rukly S, et al. Motion-capture system to assess intraoperative staff movements and door openings: Impact on surrogates of the infectious risk in surgery. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. May 2019;40(5):566-573. doi:10.1017/ice.2019.35 9. Bohl MA, Clark JC, Oppenlander ME, et al. The Barrow Randomized Operating Room Traffic (BRITE) Trial: An Observational Study on the Effect of Operating Room Traffic on Infection Rates. Neurosurgery. Aug 2016;63 Suppl 1:91-95. doi:10.1227/NEU.0000000000001295 10. Borst M, Collier C, Miller D. Operating room surveillance: a new approach in reducing hip and knee prosthetic wound infections. Am J Infect Control. Aug 1986;14(4):161-6. doi:10.1016/0196-6553(86)90095-7 11. Castella A, Charrier L, Di Legami V, et al. Surgical site infection surveillance: analysis of adherence to recommendations for routine infection control practices. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. Aug 2006;27(8):835-40. doi:10.1086/506396 12. Chakravarthy HP, S.; Balamurugan, M. Techniques in prevention of shunt infection. presented at: Childs Nerv Syst; 2011; 13. Curtis GL, Faour M, Jawad M, Klika AK, Barsoum WK, Higuera CA. Reduction of Particles in the Operating Room Using Ultraviolet Air Disinfection and Recirculation Units. J Arthroplasty. Jul 2018;33(7S):S196-S200. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.11.052 14. Cutler CJ, Hughes A, Lucente K, McBride P, Salamon M. Preventing Total Hip and Total Knee Surgical Site Infections in a Multi-hospital System through Numerous Interventions Including Standardized Infection Ratios. American Journal of Infection Control. 2013;41(6):S111-S112. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2013.03.226 15. Dalstrom DJ, Venkatarayappa I, Manternach AL, Palcic MS, Heyse BA, Prayson MJ. Time-dependent contamination of opened sterile operating-room trays. J Bone Joint Surg Am. May 2008;90(5):1022-5. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00689 16. Downing M, Modrow M, Thompson-Brazill KA, Ledford JE, Harr CD, Williams JB. Eliminating sternal wound infections: Why every cardiac surgery program needs an I hate infections team. JTCVS techniques. 2023;19:93-103. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.xjtc.2023.03.019 17. Drake CT, Goldman E, Nichols RL, Piatriszka K, Nyhus LM. Environmental air and airborne infections. Ann Surg. Feb 1977;185(2):219-23. doi:10.1097/00000658-197702000-00015 18. Elgafy H, Raberding CJ, Mooney ML, Andrews KA, Duggan JM. Analysis of a ten step protocol to decrease postoperative spinal wound infections. World J Orthop. Nov 18 2018;9(11):271-284. doi:10.5312/wjo.v9.i11.271 19. Elnour AAA, M. M.; Negm, S.; Kassim, T.;. Microbiological surveillance of air quality: A comparative study using active and passive methods in operative theater. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Phytopharmacological Research. 2018;8(1):33-38. 20. Feng YG, X.; Zhou, F.; Fu, Y. Clinical evaluation of nursing management of laminar flow operating room in controlling hospital infection. Biomedical Research. 2017;28(17) 21. Frost L, Pedersen M, Seiersen E. Changes in hygienic procedures reduce infection following caesarean section. J Hosp Infect. Feb 1989;13(2):143-8. doi:10.1016/0195-6701(89)90020-0 22. Gomez Palomo F, Luján Marco S, Romeu Magraner G, et al. PO-01-090 May a Perioperative Checklist Reduce Infection Rate after Penile Prosthesis Surgery? The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2019;16(Supplement_2):S70-S71. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.03.227 23. Guajardo IT, J.; Al-Rammah, T.; Rosson, G.; Manahan, M. OR Issues & Environmental Contamination. American Journal of Infection Control. 2015;43(S3-S17) 24. Illingworth KD, Mihalko WM, Parvizi J, Sculco T, McArthur B, el Bitar Y, Saleh KJ. How to minimize infection and thereby maximize patient outcomes in total joint arthroplasty: a multicenter approach: AAOS exhibit selection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Apr 17 2013;95(8):e50. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.00596 25. Knudsen RJ, Knudsen SMN, Nymark T, Anstensrud T, Jensen ET, Malekzadeh MJL, Overgaard S. Laminar airflow decreases microbial air contamination compared with turbulent ventilated operating theatres during live total joint arthroplasty: a nationwide survey. Journal of Hospital Infection. Jul 2021;113:65-70. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2021.04.019 26. Koek MBG, Hopmans TEM, Soetens LC, et al. Adhering to a national surgical care bundle reduces the risk of surgical site infections. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184200. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0184200 27. Lansing SS, Moley JP, McGrath MS, Stoodley P, Chaudhari AMW, Quatman CE. High Number of Door Openings Increases the Bacterial Load of the Operating Room. Surg Infect (Larchmt). Sep 2021;22(7):684-689. doi:10.1089/sur.2020.361 28. Lustenberger T, Meier SL, Verboket RD, Stormann P, Janko M, Frank J, Marzi I. The Implementation of a Complication Avoidance Care Bundle Significantly Reduces Adverse Surgical Outcomes in Orthopedic Trauma Patients. J Clin Med. Dec 11 2020;9(12)doi:10.3390/jcm9124006 29. Lynch RJ, Englesbe MJ, Sturm L, et al. Measurement of foot traffic in the operating room: implications for infection control. Am J Med Qual. Jan-Feb 2009;24(1):45-52. doi:10.1177/1062860608326419 30. Mahakit P. The pilot study of bio-aerosol level and effectiveness of air filters in Phramongkutklao Hospital. Airborne allergens II. 2013;68(97):264. 31. McConkey SJ, L'Ecuyer PB, Murphy DM, Leet TL, Sundt TM, Fraser VJ. Results of a comprehensive infection control program for reducing surgical-site infections in coronary artery bypass surgery. Infect Cont Hosp Ep. Aug 1999;20(8):533-538. doi:Doi 10.1086/501665 32. McLees WAD, B. D.; Merritt, D. H.;. Surgical suite has built-in traffic control. Modern hospital. 1967;109(5):124. 33. Montagna MT, Rutigliano S, Trerotoli P, et al. Evaluation of Air Contamination in Orthopaedic Operating Theatres in Hospitals in Southern Italy: The IMPACT Project. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Sep 25 2019;16(19)doi:10.3390/ijerph16193581 34. Napoli C, Marcotrigiano V, Montagna MT. Air sampling procedures to evaluate microbial contamination: a comparison between active and passive methods in operating theatres. BMC Public Health. Aug 2 2012;12:594. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-594 35. Ntumba P, Mwangi C, Barasa J, Aiken A, Kubilay Z, Allegranzi B. Multimodal approach for surgical site infection prevention – results from a pilot site in Kenya. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. 2015;4(S1)doi:10.1186/2047-2994-4-s1-p87 36. Ott MJP, J.; Gawlick, U.; Bulloch, B.A.; Peters, M.; Olsen, G.H.; Bulloch, G.; Mensah, M. How the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program annual conferences helped Intermountain Healthcare to develop its targeting zero initiative to reduced surgical site infections. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2014;219(4S) 37. Panahi P, Stroh M, Casper DS, Parvizi J, Austin MS. Operating room traffic is a major concern during total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. Oct 2012;470(10):2690-4. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2252-4 38. Parikh SN, Grice SS, Schnell BM, Salisbury SR. Operating room traffic: is there any role of monitoring it? J Pediatr Orthop. Sep 2010;30(6):617-23. doi:10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181e4f3be 39. Patterson P. Curbing OR traffic: finding ways to minimize the flow of personnel. OR manager. 2012;28(6):9-11. 40. Pedati CS, M.; Drake, M.; Leisy, M.; Safranek, T.; Tierney, M.;. Healthcare-associated infection outbreak investigation of an elevation of surgical site infections at a critical access hospital. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2018;5(0):630. 41. Peters PG, Laughlin RT, Markert RJ, Nelles DB, Randall KL, Prayson MJ. Timing of C-arm drape contamination. Surg Infect (Larchmt). Apr 2012;13(2):110-3. doi:10.1089/sur.2011.054 42. Prakken FJ. How to Minimize Surgical Site Infections in The Netherlands. American Journal of Infection Control. 2011;39(5)doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2011.04.297 43. Prakken FJL-V, G.M.M.; Milinovic, G.; Jacobi, C.E.; Visser, M.J.T.; Steenvoorde, P. Meetbaar verband tussen preventieve interventies en de incidentie van postoperatieve wondinfecties. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde. 2011;155(A3269) 44. Pryor F, Messmer PR. The effect of traffic patterns in the OR on surgical site infections. AORN J. Oct 1998;68(4):649-60. doi:10.1016/s0001-2092(06)62570-2 45. Pyrovolou NM, S. F.;. A comparative analysis of infection rates in scoliosis surgery following a change in surgical practice. European Spine Journal. 2012;21(0):S258. 46. Ratkowski PL. Traffic control. A study of traffic control in total joint replacement procedures. AORN J. Feb 1994;59(2):439-48. doi:10.1016/s0001-2092(07)70408-8 47. Rezapoor M, Alvand A, Jacek E, Paziuk T, Maltenfort MG, Parvizi J. Operating Room Traffic Increases Aerosolized Particles and Compromises the Air Quality: A Simulated Study. J Arthroplasty. Mar 2018;33(3):851-855. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.10.012 48. Ritter MAE, H.; French, M. L. V.; Hart, J. B.;. The operating room environment as affected by people and the surgical face mask. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1975;0(0):147-150. 49. Roberts ER, Hider PN, Wells JM, Beasley SW. The frequency and effects of distractions in operating theatres. Anz J Surg. May 2021;91(5):841-846. doi:10.1111/ans.16799 50. Roth JA, Juchler F, Dangel M, Eckstein FS, Battegay M, Widmer AF. Frequent Door Openings During Cardiac Surgery Are Associated With Increased Risk for Surgical Site Infection: A Prospective Observational Study. Clin Infect Dis. Jul 2 2019;69(2):290-294. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy879 51. Sadrizadeh S, Pantelic J, Sherman M, Clark J, Abouali O. Airborne particle dispersion to an operating room environment during sliding and hinged door opening. J Infect Public Health. Sep-Oct 2018;11(5):631-635. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2018.02.007 52. Scaltriti S, Cencetti S, Rovesti S, Marchesi I, Bargellini A, Borella P. Risk factors for particulate and microbial contamination of air in operating theatres. J Hosp Infect. Aug 2007;66(4):320-6. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2007.05.019 53. Schultz JK. Open-door policy no benefit in OR suite. AORN J. Jan 1980;31(1):29, 32-3. doi:10.1016/s0001-2092(07)69950-5 54. Squeri R, Genovese C, Trimarchi G, Antonuccio GM, Alessi V, Squeri A, La Fauci V. Nine years of microbiological air monitoring in the operating theatres of a university hospital in Southern Italy. Ann Ig. Mar-Apr 2019;31(2 Supple 1):1-12. doi:10.7416/ai.2019.2272 55. Szychowski JM, Talbot TR, Daniels T, McGee T. A Multidisciplinary Intervention to Reduce Post-Craniotomy Surgical Site Infection Rates. American Journal of Infection Control. 2011;39(5):E35-E36. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2011.04.084 56. Taaffe K, Lee B, Ferrand Y, et al. The Influence of Traffic, Area Location, and Other Factors on Operating Room Microbial Load. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. Apr 2018;39(4):391-397. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.323 57. Taaffe KM, Allen RW, Fredendall LD, et al. Simulating the effects of operating room staff movement and door opening policies on microbial load. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. Sep 2021;42(9):1071-1075. doi:10.1017/ice.2020.1359 58. Tartari E, Mamo J. Pre-educational intervention survey of healthcare practitioners' compliance with infection prevention measures in cardiothoracic surgery: low compliance but internationally comparable surgical site infection rate. J Hosp Infect. Apr 2011;77(4):348-51. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2010.12.005 59. Teter J, Guajardo I, Al-Rammah T, Rosson G, Perl TM, Manahan M. Assessment of operating room airflow using air particle counts and direct observation of door openings. Am J Infect Control. May 1 2017;45(5):477-482. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2016.12.018 60. Tjade OH, Gabor I. Evaluation of airborne operating room bacteria with a Biap slit sampler. J Hyg (Lond). Feb 1980;84(1):37-40. doi:10.1017/s0022172400026498 61. Trouten AF. The operating room door is open. Hospital administration in Canada. 1977;19(3):S9, 11. 62. Vaishnavi G.; Reddy AVGM, D.; Oruganti, G.; Allam, R.R. Targeted infection control practices lower the incidence of surgical siteinfections following total hip and knee arthroplasty in an Indian tertiary hospital. Journal of Patient Safety & Infection Control. 2019;7(1):20-24. 63. Vila Barriuso EFC, J.L.; Molto Garcia, L.; Rodriguez Cosmen, C.; Sadurni Sarda, M.; Pacreu Terradas, S.; Garcia Bernedo, C. Incidence of surgical wound infections in patients undergoing craniotomy during the period 2007 to 2014. Journal of Neurosurgical Anesthesiology. 2016 2016;28(2):S39. doi:10.1097/ANA.0000000000000287 64. Von Dolinger EJOVDdB, D.; De Souza, G.M.; De Melo, G.B.; Gontijo Filho, P.P. . Air contamination levels in operating rooms during surgery of total hip and total knee arthroplasty, hemiarthroplasty and osteosynthesis in the surgical center of a Brazilian hospital. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2010;43(5) 65. De Vries EDA, W.M.; Van Dijk, C.N.; Hollmann, M.W.; Boermeester, M.A. Tapas study: Timing of antibiotic prophylaxis and surgical site infection. Inflammation Research. 2010;59(1) 66. de Jonge SW, Boldingh QJJ, Koch AH, et al. Timing of Preoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis and Surgical Site Infection: TAPAS, An Observational Cohort Study. Ann Surg. Oct 1 2021;274(4):e308-e314. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003634 67. Wang C, Holmberg S, Sadrizadeh S. Impact of door opening on the risk of surgical site infections in an operating room with mixing ventilation. Indoor and Built Environment. 2019;30(2):166-179. doi:10.1177/1420326x19888276 68. Wilson MCD, D. A Multidisciplinary Method to Decrease Surgical Site Infection Rates Utilizing a Back to Basics Approach. American Journal of Infection Control. 2009;37(5):E150-E151. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2009.04.206 69. Wolf HWH, M.M.; Hall, L.B. Open operating room doors and Staphyococcus aureus. Hospitals. 1961;35 70. Woods DP, E.; Simpson, M.A.; Guarrera, J.; Fischer, R.; Khorzad, R.; Daud, A.; Reyes, E.; Wymore, E.; Skaro, A.; Ladner, D. Assessing Risk of Infections Due To Foot Traffic in the OR. 2015;(Abstract P-500)

|

||

Quality assessment, following the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale contains 8 items within 3 domain with a maximum score of nine stars. A study can be awarded a maximum of one star for each numbered item within the selection and outcome domains. A maximum of two stars can be given for comparability.

Good quality: study with 3 or 4 stars in selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in outcome domain.

|

Study (year) |

Selection

|

Comparability |

Outcome |

|||||||

|

|

Representativeness of the exposed cohort |

Selection of the non-exposed cohort |

Ascertainment of exposure |

Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study |

Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis controlled for confounders |

Assessment of outcome |

Follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur |

Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts |

Stars |

Quality assess-ment |

|

Allegranzi 2018

|

* |

* |

*

|

* |

** |

* |

* |

* |

9 |

Good |

|

Bahethi 2020

|

* |

* |

* |

* |

- |

* |

* |

* |

7 |

Poor |

|

Bediako-Bowan 2020

|

* |

* |

* |

* |

** |

* |

* |

* |

9 |

Good |

|

De Jonge 2021

|

* |

* |

* |

* |

** |

* |

* |

* |

9 |

Good |

|

Mathijssen 2016

|

* |

* |

* |

* |

** |

* |

* |

- |

8 |

Good |

|

Perez 2018

|

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

8 |

Good |

|

Prakken 2011

|

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

8 |

Good |

|

Stauning 2018 |

* |

* |

* |

* |

** |

* |

* |

* |

9 |

Good |

|

1. Wells GAS, B.; O'Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Accessed October 12, 2023, https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp |

||||||||||

Fair quality: 2 stars in selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in outcome domain.

Poor quality: 0 or 1 star in selection domain OR 0 stars in comparability domain OR 0 or 1 stars in outcome domain.

Probability of SSI in relation to the number of door openings per hour

A one-step meta-analysis of individual participant data using a random-effects framework to test the effect on the number of door openings per hour on SSI by duration of surgery and CDC wound classification.

Variables included in the model: ASA score, CDC wound classification, emergency surgery, procedure duration, implantation of a foreign body, income level of the country where the study was conducted, and study as a random effect. Vertical line at x = 10 represents the commonly recommended threshold of 10 door openings per hour, as often suggested in guidelines.

ASA, American Society of Anaesthesiologists; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria; min, minutes; SSI, surgical site infection.

Two example patients

A one-step meta-analysis of individual participant data using a random-effects framework to test the effect of the number of door openings per hour on SSI for two example patients at different door opening rates.

|

|

Probability of SSI |

|

|

|

Door openings per hour |

Patient 1* |

Patient 2** |

|

|

0 |

1.35% |

10.28% |

|

|

10 |

1.50% |

11.34% |

|

|

20 |

1.68% |

12.51% |

|

|

30 |

1.87% |

13.77% |

|

|

40 |

2.09% |

15.14% |

|

|

50 |

2.32% |

16.62% |

|

|

60 |

2.59% |

18.21% |

|

|

*Patient 1: Clean surgery, ASA-score 1, duration of surgery 120 minutes, elective surgery, implantation of a foreign body, high income country. **Patient 2: Non-clean surgery, ASA-score 2, duration of surgery 120 minutes, emergency surgery, no implantation of a foreign body, high income country ASA, American Society of Anaesthesiologists; SSI, surgical site infection

|

|||

GRADE assessment

We used the Grading of Recommendation Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology to evaluate the certainty of evidence using a minimally contextualized approach on the following domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. The minimally important difference was defined as 1.5% based on the default for appreciable benefit and harm of 25% and the SSI incidence of 6% in presented data for procedures with ten or less door openings per hour. Imprecision was evaluated taking the minimally important difference into account and, when the relative effect was large, we used the optimal information size approach by calculating the ratio of the upper to the lower boundary of the confidence interval with a threshold for downgrading of 2.5.

Since all included studies are observational studies, the rating for the GRADE starts low. Downgrading can be necessary due to the following reasons:

- Risk of bias

Of the 8 studies included in the IPDMA, there was one poor quality study. We performed a sensitivity analysis excluding the poor quality study. The results were comparable with the overall analysis, and downgrading for risk of bias was not needed. - Inconsistency

For inconsistency no downgrade was necessary (τ2 = 0.205). - Indirectness

All studies provided IPD on the primary outcome SSI, indirectness was therefore assessed as not serious. - Imprecision

There was no imprecision because the confidence interval did not overlap thresholds of interest and the ratio of the upper to the lower boundary of the confidence interval was below 2.5. - Publication bias

The risk of publication bias was considered as substantial because of the observational design of the included studies and the fact that data was often collected for previous study.

|

Certainty assessment |

Certainty |

||||||

|

№ of studies |

Study design |

Risk of bias |

Inconsistency |

Indirectness |

Imprecision |

Other considerations |

|

|

Surgical site infection |

|||||||

|

7 |

observational studies |

not serious |

none |

none |

none |

publication bias suspected* |

⨁◯◯◯ |

|

*data often collected for previous study 1. Schünemann HB, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A. GRADE Handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html |

|||||||

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 17-12-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-12-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules 2 tot 16 is in 2020 op initiatief van de NVvH een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties. Daarnaast is in 2022 op initiatief van het Samenwerkingsverband Richtlijnen Infectiepreventie (SRI) een separate multidisciplinaire werkgroep samengesteld voor de herziening van de WIP-richtlijn over postoperatieve wondinfecties: module 17-22. De ontwikkelde modules van beide werkgroepen zijn in deze richtlijn samengevoegd.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoek financiering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Mevr. prof. dr. M.A. Boermeester |

Chirurg |

* Medisch Ethische Commissie, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC * Antibiotica Commissie, Amsterdam UMC |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Hieronder staan de beroepsmatige relaties met bedrijfsleven vermeld waarbij eventuele financiële belangen via de AMC Research B.V. lopen, dus institutionele en geen persoonlijke gelden zijn: Skillslab instructeur en/of spreker (consultant) voor KCI/3M, Smith&Nephew, Johnson&Johnson, Gore, BD/Bard, TELABio, GDM, Medtronic, Molnlycke.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Institutionele grants van KCI/3M, Johnson&Johnson en New Compliance.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Ik maak me sterk voor een 100% evidence-based benadering van maken van aanbevelingen, volledig transparant en reproduceerbaar. Dat is mijn enige belang in deze, geen persoonlijk gewin.

Overige belangen Geen.

|

Extra kritische commentaarronde. |

|

Dhr. dr. M.J. van der Laan |

Vaatchirurg |

Vice voorzitter Consortium Kwaliteit van Zorg NFU, onbetaald

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen.

|

Geen.

|

|

Dhr. dr. W.C. van der Zwet |

Arts-microbioloog |

Lid Regionaal Coördinatie Team, Limburgs infectiepreventie & ABR Zorgnetwerk (onbetaald) |

||

|

Dhr. dr. D.R. Buis |

Neurochirurg |

Lid Hoofdredactieraad Tijdschrift voor Neurologie & Neurochirurgie - onbetaald |

||

|

Dhr. dr. J.H.M. Goosen |

Orthopaedisch Chirurg |

Inhoudelijke presentaties voor Smith&Nephew en Zimmer Biomet. Deze worden vergoed per uur. |

||

|

Dhr. drs. N. Bontekoning |

Arts-onderzoeker |

Geen. |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen. |

Geen.

|

|

Mw. drs. H. Jalalzadeh |

Arts-onderzoeker |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. N. Wolfhagen |

AIOS chirurgie |

|||

|

Mw. drs. H. Groenen |

Arts-onderzoeker |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. F.F.A. Ijpma |

Traumachirurg |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. P. Segers |

Cardiothoracaal chirurg |

|||

|

Mw. Y.E.M. Dreissen |

AIOS neurochirurgie |

|||

|

Dhr. R.R. Schaad |

Anesthesioloog |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voor de invitational conference. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptmodules zijn tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt. Voor de modules 17-22 was de patiëntfederatie vertegenwoordigd in de werkgroep.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn.

Voor module 8 (Negatieve druktherapie) geldt dat uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000 - 40.000 patiënten). Tevens volgt uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht.

Voor de overige modules en aanbevelingen geldt dat uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten). Tevens volgt uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Ook wordt geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners verwacht of een wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

Zie voor de implementatie het implementatieplan in het tabblad 'Bijlagen'.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroepen de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die chirurgie ondergaan. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door middel van een invitational conference. De verslagen hiervan zijn opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Adaptatie

Een aantal modules van deze richtlijn betreft een adaptatie van modules van de World Health Organization (WHO)-richtlijn ‘Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection’ (WHO, 2018), te weten:

- Module Normothermie

- Module Immunosuppressive middelen

- Module Glykemische controle

- Module Antimicrobiële afdichtingsmiddelen

- Module Wondbeschermers bij laparotomie

- Module Preoperatief douchen

- Module Preoperatief verwijderen van haar

- Module Chirurgische handschoenen: Vervangen en type handschoenen

- Module Afdekmaterialen en operatiejassen

Methode

- Uitgangsvragen zijn opgesteld in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

- De inleiding van iedere module betreft een korte uiteenzetting van het knelpunt, waarbij eventuele onduidelijkheid en praktijkvariatie voor de Nederlandse setting wordt beschreven.

- Het literatuuronderzoek is overgenomen uit de WHO-richtlijn. Afhankelijk van de beoordeling van de actualiteit van de richtlijn is een update van het literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd.

- De samenvatting van de literatuur is overgenomen van de WHO-richtlijn, waarbij door de werkgroep onderscheid is gemaakt tussen ‘cruciale’ en ‘belangrijke’ uitkomsten. Daarnaast zijn door de werkgroep grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming gedefinieerd in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten, en is de interpretatie van de bevindingen primair gebaseerd op klinische relevantie van het gevonden effect, niet op statistische significantie. In de meta-analyses zijn naast odds-ratio’s ook relatief risico’s en risicoverschillen gerapporteerd.

- De beoordeling van de mate van bewijskracht is overgnomen van de WHO-richtlijn, waarbij de beoordeling is gecontroleerd op consistentie met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (GRADE-methode; http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). Eventueel door de WHO gerapporteerde bewijskracht voor observationele studies is niet overgenomen indien ook gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde studies beschikbaar waren.

- De conclusies van de literatuuranalyse zijn geformuleerd in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

- In de overwegingen heeft de werkgroep voor iedere aanbeveling het bewijs waarop de aanbeveling is gebaseerd en de aanvaardbaarheid en toepasbaarheid van de aanbeveling voor de Nederlandse klinische praktijk beoordeeld. Op basis van deze beoordeling is door de werkgroep besloten welke aanbevelingen ongewijzigd zijn overgenomen, welke aanbevelingen niet zijn overgenomen, en welke aanbevelingen (mits in overeenstemming met het bewijs) zijn aangepast naar de Nederlandse context. ‘De novo’ aanbevelingen zijn gedaan in situaties waarin de werkgroep van mening was dat een aanbeveling nodig was, maar deze niet als zodanig in de WHO-richtlijn was opgenomen. Voor elke aanbeveling is vermeld hoe deze tot stand is gekomen, te weten: ‘WHO’, ‘aangepast van WHO’ of ‘de novo’.

Voor een verdere toelichting op de procedure van adapteren wordt verwezen naar de Bijlage Adapteren.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

World Health Organization. Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection,

second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475, accessed 12 June 2023).

Zoekverantwoording

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H,

Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

World Health Organization. Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection,

second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475, accessed 12 June 2023).