Enhanced Recovery After Surgery

Uitgangsvraag

Hoe kan een Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) protocol rondom anatomische longresecties, ofwel een ‘Enhanced Recovery After Thoracic Surgery (ERATS)’ programma, optimaal worden ingezet?

De uitgangsvraag omvat de volgende deelvraag:

- Uit welke onderdelen kan dit programma het best bestaan?

Aanbeveling

Pas standaardisatie multidisciplinair toe in perioperatieve zorg rondom longoperaties, bijvoorbeeld middels de Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®)-systematiek.

Licht patiënten, naasten en het zorgteam goed en consistent voor, zodat allen hetzelfde, eenduidige begrip hebben van het perioperatieve proces.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de vergelijking tussen het wel of niet implementeren van een ERAS®-programma bij patiënten die en anatomische longresectie hebben ondergaan. Voor zowel de cruciale als de belangrijke uitkomstmaten was de bewijskracht zeer laag. Dit heeft er met name mee te maken dat deze vergelijkende studies observationeel onderzoek betreffen. Ook is het zo dat de verschillende studies een grote variëteit hebben wat betreft de elementen die zijn opgenomen in het ERAS®-programma.

De ERAS®-benadering, met erkenning voor de meerwaarde van de marginal gains -de elkaar versterkende optelsom van verschillende programma onderdelen- lijkt in deze observationele studies wel consistent te leiden tot reductie in complicaties en kortere postoperatieve opnameduur, zonder dat dit leidt tot een toename in heropnames of mortaliteit (Ljungqvist, 2017; Senturk, 2017). Dit is in lijn met wat er eerder is gezien bij inmiddels wijdverbreide ERAS®-programma’s voor andere ziektebeelden, bijvoorbeeld colorectaal carcinoom.

De in de literatuursamenvatting geanalyseerde programma’s beschrijven allemaal evidence based interventies met betrekking tot preoperatieve optimalisatie van de conditie van de patiënt, consistente voorlichting van patiënt en naaste, reductie van perioperatieve stress door minimaal invasieve chirurgie, multimodale en opioïde-sparende pijnbestrijding, voorkomen van onderkoeling en overvulling; postoperatief reduceren van herstel beperkende factoren als lijnen en drains, pijn, misselijkheid en het stimuleren van zelfstandigheid in mobiliseren, dieet en autonomie richting een tijdig ontslag.

Deze principes zijn van toepassing op alle patiëntencategorieën die een anatomische longresectie ondergaan. Essentieel voor optimaal effect van ERAS® programma’s is dat de programmaonderdelen zo goed en compleet mogelijk gevolgd moeten worden. Het meest uitputtende overzicht van onderdelen voor een Enhanced Recovery After Thoracic Surgery (ERATS) programma is gepubliceerd in de ERAS® Society/ESTS guidelines (Batchelor EJCTS 2019). De richtlijn commissie ondersteunt deze aanbevelingen. Meerdere aanbevelingen zijn systematisch onderbouwd in Nederlandse richtlijn modules.

Hoe heeft de ERAS-society het ERAS programma gedefinieerd?

De Guidelines for enhanced recovery after lung surgery; recommendations of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS) (2019) omvat 45 elementen waarvan van elk wordt gesteld dat deze in meer of mindere mate een positief effect hebben op de uitkomsten na anatomische longresectie.

Samenvattend wordt het volgende geadviseerd:

Preoperatieve Fase

- Preoperatieve informatie, educatie en counseling.

- Preoperatieve screening op voedingstoestand en preoperatieve bijvoeding van risicopatiënten; voeding conform de berekende energie en eiwitbehoefte.

- Screening op anemie.

- Stoppen met roken en vermindering alcohol gebruik.

- Multimodale prehabilitatie bij patiënten met borderline longfunctie en ter vergroting functionele capaciteit.

Opname

- Nuchterbeleid: vast voedsel tot 6 uur voor inductie en heldere vloeistof tot 2 uur voor inductie, bijvoorbeeld met koolhydraat drank (tenzij er sprake is van diabetes mellitus).

- Vermijden routinematige sedatieve premedicatie.

Peroperatieve fase

- Gestandaardiseerd anesthesieprotocol met long-protectieve enkele longbeademing, met een combinatie van regionale en algehele anesthesietechnieken, waarbij intraveneuze en kortwerkende volatiele anesthesie equivalent zijn

- Intraveneuze antibiotica profylaxe, chloorhexidine desinfectie, haar verwijderen middels tondeuse i.p.v. scheren.

- Behoud van normothermie. Continue kerntemperatuur meting voor compliance.

- Multimodale profylaxe misselijkheid en braken.

- Regionale anesthesie met als doel vermijden van opiaten, waarbij paravertebraal blok en epiduraal gelijkwaardige pijnstilling geven.

- Toepassen van multimodale analgesie met paracetamol en NSAID, tenzij contra-indicaties, ketamine, vnl bij patiënten met chronische pijn en dexametason als pijnstillings- en PONV adjunct.

- Streven naar euvolemie met postoperatieve ‘bijna-nul’ vochtbalans nastreven met gebalanceerde crystalloiden en niet met NaCL 0.9% infusie. Zo snel mogelijk staken IV vocht en overstappen op oraal.

- Profylaxe Atriumfibrilleren door continueren eventuele beta blokker, magnesium suppletie bij hypomagnesiemie, overweeg amiodarone postoperatie of diltiazem preoperatie bij hoogrisico patiënten.

- Chirurgische toegang via minimaal invasieve benadering (VATS); in geval van thoracotomie: spiersparend met intercostaal zenuw en spier sparende techniek en sluiten met sparen van onderste intercostaalzenuw.

Postoperatieve fase

- Thoraxdrainage met 1 drain, zonder zuigen. gebruikmakend van digitale drainsystemen, met een acceptabele dagelijkse drainvochtproductie tot 450ml/24u

- Tromboseprofylaxe met laagmoleculair heparine postoperatief in combinatie met steunkousen / intermitterende compressie tot ontslag.

- Routinematige transurethrale catheterisatie alleen voor monitoring urine productie vermijden.

- Vroege mobilisatie binnen 24u.

- Vroege hervatting orale voeding

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Patiënten vinden het fijn om zo snel mogelijk weer naar huis te kunnen om te herstellen in de voor hen vertrouwde omgeving. ERAS richt zich op een goede voorbereiding en goed herstel door zo min mogelijk fysieke impact van de resectie en goede mentale begeleiding. Voorlichting en verwachtingsmanagement zijn uitermate belangrijk. De patiënt moet niet het gevoel hebben dat korte opnameduur een doel op zich is, maar dat de patiënt geholpen wordt om zo snel mogelijk te herstellen.

Het is belangrijk om dit ook over de ziekenhuismuren heen te continueren. Het aanwijzen van een casemanager is hierbij heel belangrijk. Maar ook het tijdig inschakelen van thuiszorg.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Li (2021) beschrijft ook de totale kosten van de ziekenhuisopname. Vijf van de zes studies die deze uitkomstmaat beschreven lieten lagere kosten zien voor de groep patiënten die volgens ERAS® principes was behandeld. Dit lijkt te verklaren door minder complicaties en kortere opnameduur; daar waar de investeringen vooral bestaan uit het in betere samenhang anders en effectiever inzetten van al beschikbare mensen, werkwijzen en middelen. Hiertoe is wel scholing van het gehele team nodig, meer aandacht voor patiëntenvoorlichting en beschikbaarheid van goede audit en feedback logistiek.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het onderwerp: “Wat is het optimale perioperatieve beleid bij minimale invasieve thoraxchirurgie?” was in 2018 onderdeel van de Kennisagenda van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde (Longchirurgie). In het licht van de al aangetoonde praktijkvariatie in Nederland, met consequenties voor perioperatieve zorguitkomsten, werd een gestandaardiseerd protocol/richtlijn als zeer wenselijk ervaren. Een ERAS-protocol dat voorziet in uitgebreide voorlichting en begeleiding voor en na ziekenhuisopname, zou aan moeten sluiten bij alle patiëntengroepen. Door aan zorgverlenerszijde protocol onderdelen zo goed mogelijk uit te voeren, wordt een situatie voor zo goed mogelijk herstel gecreëerd. Afhankelijk van de patiënt en zijn/haar achtergrond resulteert dit in de kortst mogelijke opnameduur met een minimum aan complicaties; dit is het gevolg van een goed uitgevoerd ERAS-protocol, niet een doel op zich.

In een recente probleemanalyse zijn potentiële facilitators en barrières voor de invoering van een ERAS-protocol in Nederland onderzocht (von Meyenfeldt, 2022). Hierbij werden de determinanten in 5 thema’s georganiseerd:

- Op niveau van communicatie tussen patiënt en zorgverlener;

- De competenties van de zorgverlener;

- Patiënt factoren;

- Factoren die verandering van werkwijze ondersteunen;

- Bruikbaarheid van het protocol.

De meeste facilitators en barrières bevestigen de bevindingen van eerdere analyses, zoals de noodzaak van een multidisciplinair team met ondersteuning van een senior staflid en een ERAS®- coördinator als facilitators; gebrek aan feedback over geleverde perioperatieve zorg en afwezigheid van managementsupport zijn bekend als barrières (Francis, 2018).

Het werken in teamverband versus werken in verschillende beroepsgroepen (artsen, verpleging, fysiotherapie, diëtetiek etc; zie module organisatie van zorg) vergt vooral een andere wijze van organiseren van zorg en het creëren van andere momenten van afstemming en overleg. De Nederlandse probleemanalyse benadrukt het mogelijk nadelige effect van inconsistente communicatie, het gebrek aan ondersteuning van ziekenhuis naar huis en het gebrek aan toegankelijke feedback data (von Meyenfeldt, 2022; Francis, 2018; Stone, 2018).

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Bij de aangetoonde praktijkvariatie in perioperatieve zorg met consequenties voor klinische uitkomsten voor patiënten die een anatomische longresectie ondergaan in Nederland, lijkt standaardisatie middels een gedetailleerd multifactorieel perioperatief zorgprotocol van toegevoegde waarde. Voor optimaal effect van ERAS®-programma’s is bekend dat de programmaonderdelen zo goed en volledig mogelijk gevolgd moeten worden. Hiervoor is goede en consistente informatievoorziening aan patiënten en naasten van groot belang. Om consistent een eenduidig verhaal te kunnen vertellen, moeten alle betrokken zorgverleners goed op de hoogte zijn van het protocol.

De positieve effecten op complicaties, ligduur en kosten, zonder toename van heropnames of mortaliteit, worden consistent gedemonstreerd in de aangehaalde studies; echter door de observationele aard van deze studies met een hoog risico op bias is de gradering van de conclusies erg laag. Gegevens over effecten op kwaliteit van leven ontbreken. Gezien de klinische impact en de, grotendeels in richtlijnmodules uitgewerkte onderbouwing van de protocol onderdelen, lijkt, naar de mening van de richtlijncommissie, een positieve aanbeveling toch gerechtvaardigd.

Door expliciete keuzes te maken in alle protocolonderdelen die potentieel van invloed kunnen zijn op het herstel na longoperaties, wordt de praktijkvariatie (zowel binnen een ziekenhuis als tussen ziekenhuizen) gereduceerd. Vanuit de basis van deze standaardisatie kan het ERAS-protocol dan weer op onderdelen verbeterd, of beter onderbouwd worden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Momenteel is er, in afwezigheid van een Nederlandse richtlijn, sprake van praktijkvariatie in perioperatieve zorg voor patiënten die een anatomische longresectie ondergaan, met als gevolg variatie in klinische uitkomsten. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) zorgprotocollen, gaan ervan uit dat de optelsom van protocol onderdelen in combinatie met uitgebreide patiëntenvoorlichting leidt tot betere klinische uitkomsten in opnameduur en complicaties, zonder toename van heropnames. Voor ERAS® -protocollen is het van essentieel belang voor optimaal effect op klinische uitkomsten, dat de protocol onderdelen bij zoveel mogelijk patiënten zo volledig mogelijk worden gevolgd. Deze module beschrijft in welke mate het volgen van de ERAS®-aanbevelingen rondom anatomische longresecties bijdraagt aan optimale klinische uitkomsten en welk onderscheid gemaakt kan worden in het belang van de verschillende protocol onderdelen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of an ERAS® program on mortality compared with the period before the implementation of an ERAS® program (pre- ERAS®) in patients who have undergone an anatomical lung resection. Sources: Bellas-Cotan, 2021; Khoury, 2021; Li, 2021; Peng, 2021: Wang, 2021 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of an ERAS® program on overall postoperative complications compared with the period before the implementation of an ERAS® program (pre- ERAS®) in patients who have undergone an anatomical lung resection. Sources: Del Calvo, 2021; Forster, 2021; Khoury 2021; Li, 2021; Ni, 2012 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of an ERAS® program on postoperative length of stay compared with the period before the implementation of an ERAS®program (pre- ERAS®) in patients who have undergone an anatomical lung resection. Sources: Li, 2021; Wang, 2021; Wu, 2021 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of an ERAS® program on the readmission rate compared with the period before the implementation of an ERAS® program (pre- ERAS®) in patients who have undergone an anatomical lung resection. Sources: Bellas-Cotan, 2021; Del Calvo, 2020; Forster, 2021; Khoury 2021; Li, 2021; Ni, 2021; Peng, 2021; Tiberi, 2022 |

|

no GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of an ERAS® program on quality of life and functional recovery compared with the period before the implementation of an ERAS® program (pre- ERAS®) in patients who have undergone an anatomical lung resection. Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Systematic review

Li (2021) investigated the short-term impact of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) on lung resection surgery in relation to postoperative complications. The PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library databases were searched until October 2020 to identify the studies that implemented an ERAS program in lung cancer surgery. The inclusion criteria were as follows: adult patients undergoing elective pulmonary resection (wedge resection, lobectomy, pneumonectomy), patients who received an ERAS program with at least 4 elements that covered at least two phases of perioperative care, and a traditional care control group that had adopted at least 3 elements fewer than the ERAS group. Case reports, reviews and conference abstracts were excluded. A total of 21 studies with 6,480 patients were included and a meta-analysis was performed. There were 19 cohort studies and 2 RCT’s included in this review. A total of 2,617 patients were included in the ERAS group (40%), while 3,863 patients were enrolled in the control group (60%). The number of ERAS elements utilized in the ERAS group and control group ranged from 5 to 22 and 0 to 10, respectively. The reported outcome measures were: mortality, postoperative complications, readmission rate and postoperative length of stay.

Observational studies

Tiberi (2022) assessed the impact of an Enhanced Pathway of Care (EPC, similar to ERAS) program in patients undergoing VATS lungresection on efficiency and safety. This retrospective cohort study included patients undergoing VATS resections including lobectomy, segmentectomy and wedge resection for both benign and malignant lung neoplasm. Patients were excluded if: patients undergoing pneumonectomy, conversion to open surgery, planned postoperative intensive-care monitoring, lack of caregiver, or inability to collaborate (language barriers, psychiatric pathology). Two groups were created: pre-EPC (n=182) and EPC (n=182). The elements of the EPC protocol are described in the Evidence Table. The length of follow-up was 30 days. The reported outcome measure was readmission rate.

Bellas-Cotán (2021) analyzed the effects of an ERAS program on complication rates, readmission, and length of stay in patients undergoing pulmonary resection. The ambispective cohort study with a prospective arm of 50 patients undergoing thoracic surgery within an ERAS program and a retrospective arm of 50 patients undergoing surgery before the protocol was implemented (control group). Patients who refused to take part or were under 18 years of age were excluded. The elements of the ERAS protocol are described in the Evidence Table. The length of follow-up was 30 days. The reported outcome measures were mortality and readmission rate.

Forster (2021) evaluated the effect of ERAS pathways on postoperative outcomes of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients undergoing video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) lobectomy. The retrospective cohort study reviewed all patients undergoing VATS lobectomy. Patients with intra-operative conversion to thoracotomy, patients presenting metastatic lesions, and patients with emergency procedures were excluded. Patients were divided in two groups, according to their clinical management (pre- ERAS n=167 or ERAS n=140), mainly defined by the timing of their operation before or after systematic introduction of the ERAS pathway. The elements of the ERAS protocol are described in the Evidence Table. The length of follow-up was 30 days. The reported outcome measures were postoperative complications and readmission rate.

Khoury (2021) investigated the effects of preliminary implementation of an ERAS® protocol, in comparison with conventional care, on lung resection outcomes. This retrospective observational study included adult patients undergoing pulmonary resections (wedge resection, segmentectomy, lobectomy and bilobectomy). Only a patient’s first thoracic operation was eligible, redo surgeries and unexpected returns to the operation room were excluded, as well as trauma patients. Patients were also excluded when they simultaneously underwent esophagectomy, pneumonectomy, or coronary artery bypass grafting. Patients were divided into two time periods (pre- ERAS (n=133) and post- ERAS (n=131). The elements of the ERAS protocol are described in the Evidence Table. The length of follow-up was 30 days. The reported outcome measures were mortality, postoperative complications, and readmission rate.

Ni (2021) evaluated the feasibility and necessity for ERAS in the perioperative management of minimally invasive lobectomy. All patients that underwent thoracoscopic lobectomy were eligible for inclusion. Patients were excluded if they received secondary surgery due to complications, lack of perioperative related clinical data, formulated perioperative rehabilitation management regulations were not strictly followed during the perioperative period, patients who had refused early discharge. In total, 121 patients received routine management (controls), and 508 patients received care according to an ERAS protocol. The elements of the ERAS protocol are described in the Evidence Table. The length of follow-up was not reported. The reported outcome measures were postoperative complications and readmission rate.

Peng (2021) evaluated outcomes of patients undergoing pulmonary resection before and after the implementation of an ERAS protocol. The retrospective cohort study included 131 patients undergoing anatomic lung resections. Exclusion criteria included: incomplete dataset, extended resections (pneumonectomy), or non-resectional operations. Patients were grouped into pre- (n=64) and post- ERAS (n=67) cohorts. The ERAS protocol prioritized early mobility, limited invasive monitoring, euvolemia, and non-narcotic analgesia, including intraoperative regional blocks instead of thoracic epidurals. The length of follow-up was 30 days. The reported outcome measures were mortality and readmission rate.

Wang (2021) evaluated the outcomes following the implementation of ERAS for patients undergoing lung cancer surgery. The retrospective cohort study included 1,749 patients with lung cancer who underwent pulmonary resections. The inclusion criteria were as follows: adult patients (≥ 18 years old) with a diagnosis of primary non-small-cell lung cancer, anatomical lung resection including lobectomy and segmentectomy. Patients were divided into two time periods for analysis (routine pathway (n=1058) and ERAS pathway (n=691)). The whole ERAS program implemented in this study included ERAS education and

consultation, venous thromboembolisms (VTEs) prophylaxis, chest tubes, urinary catheters, postoperative pain and nutrition management, anesthesia, perioperative respiratory training, and mobilization. The length of follow-up was not reported. The reported outcome measures were mortality.

Del Cavo (2020) compared patients who were managed with pre-emptive pain management with ERAS, ERAS only, and standard care. The retrospective case-control study included 443 patients who underwent elective minimally invasive pulmonary resection. They excluded patients with diagnostic wedge procedures, emergent or urgent pulmonary resections, and pulmonary resections as part of the two-step procedure for cardiac sarcoma with pulmonary resection. There were 132 patients that received the pre-emptive pain management with ERAS, 90 patients that received ERAS only, and 221 patients who received standard of care. For this module, the patients that received pre-emptive pain management with ERAS were not included. The elements of the fast-track surgery are described in the Evidence Table. The length of follow-up was 30 days. The reported outcome measures were postoperative complications, and readmission rate.

Wu (2020) explored the efficacy and safety of fast-track surgery in the perioperative period of single hole thoracoscopic radical resection of lung cancer. The retrospective cohort study included 152 lung cancer patients undergoing single-hole thoracoscopic radical resection of lung cancer. Patients were excluded if: tumors were too large or involved in the vessels and trachea, cancer cells found in the pleural effusion, conversion to thoracotomy since extensive pleural adhesions were found intraoperatively, single-hole thoracoscopy was converted to thoracotomy due to uncontrolled intraoperative bleeding, distant metastases or severe anemia, complicated with severe heart, lung, liver or kidney disfunction or other malignancies and with poor compliance. Patients were divided into two groups according to the healthcare that they received: 76 patients received fast track surgery and 76 patients received conventional care. The elements of the fast-track surgery are described in the Evidence Table. The length of follow-up was not reported. The reported outcome measures were postoperative length of stay.

Results

Mortality (critical)

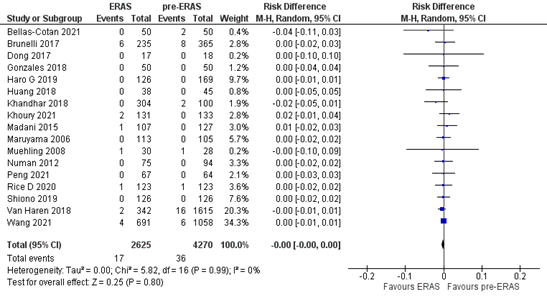

The outcome measure mortality was reported in 5 studies (Bellas-Cotan, 2021; Khoury, 2021; Li, 2021; Peng, 2021: Wang, 2021). In total, 17 out of the 2625 (0.6%) patients who received ERAS® died, versus 36 out of the 4270 patients (0.8%) who were treated before ERAS® was implemented. The pooled risk difference (RD is 0.00, 95%CI 0.00 to 0.00) (Figure 1). This means that there is no difference in mortality between patients who were treated with ERAS® versus patients who were treated before ERAS® was implemented.

Figure 1. Meta-analysis of mortality in the ERAS® versus pre- ERAS® group.ERAS®: enhanced recovery after surgery. Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Complications (critical)

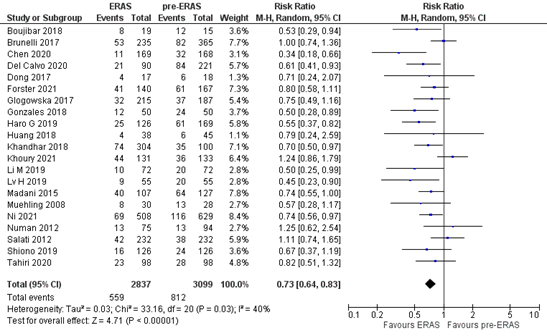

The outcome measure complications was reported in 5 studies (Del Calvo, 2020; Forster, 2021; Khoury 2021; Li, 2021; Ni, 2021). In total, 559 out of the 2837 patients (19.7%) who were treated with ERAS® had a postoperative complication, versus 812 out of the 3099 (26.2%) patients who were treated before ERAS® was implemented. The pooled RR was 0.73 (95%CI 0.64 to 0.83) (Figure 2). This means that patients who were treated with ERAS® have a lower risk on developing postoperative complications. This difference is clinically relevant.

Figure 2. Meta-analysis of overall postoperative complications in the ERAS® versus pre- ERAS® group. ERAS®: enhanced recovery after surgery. Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Postoperative length of stay (important)

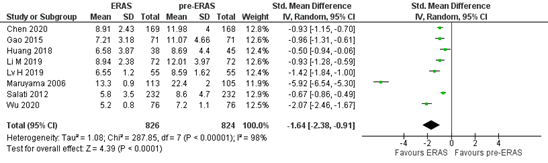

The outcome measure postoperative length of stay was reported in three studies (Li, 2021; Wang, 2021; Wu, 2021). Due to differences in reporting the outcome measure, the study of Wang (2021) was not included in the meta-analysis.

In total, 826 patients were treated with ERAS®, while 824 patients were treated before ERAS® was implemented (Figure 3). The mean postoperative stay is 1.64 days shorter in patients who were treated with ERAS® (95%CI 0.91 to 2.38). This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 3. Meta-analysis of postoperative length of stay in the ERAS® versus pre- ERAS® group. ERAS®: enhanced recovery after surgery. Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Wang (2021) reported the median postoperative length of stay. Patients in the ERAS® group had a median postoperative length of stay of 4.0 days (IQR 2.0 to 6.0), patients in the routine group had a median postoperative length of stay of 6.0 days (IQR 4.0 to 9.0). This means that patients in the ERAS® group had a 2 days shorter postoperative length of stay. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Readmission rate (important)

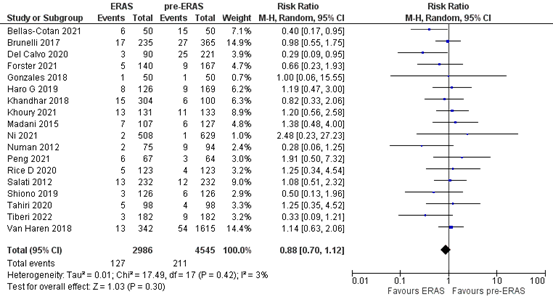

The outcome measure readmission rate was reported in 8 studies (Bellas-Cotan, 2021; Del Calvo, 2020; Forster, 2021; Khoury 2021; Li, 2021; Ni, 2021; Peng, 2021; Tiberi, 2022). In total, 127 out of the 2986 (4.3%) patients who were treated with ERAS® were readmitted, versus 211 out of the 4545 (4.6%) patients who were treated pre- ERAS®. The pooled RR is 0.88 (95%CI 0.70 to 1.12), in favor of ERAS®. This difference is clinically relevant.

Figure 4. Meta-analysis of readmission rate in the ERAS®versus pre- ERAS®group. ERAS®: enhanced recovery after surgery. Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Quality of life (important)

This outcome measure was not reported in the included studies.

Functional recovery (important)

This outcome measure was not reported in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

Mortality and postoperative length of stay

The level of evidence regarding these outcome measures comes from observational studies and therefore starts at low. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1). The level of evidence is therefore very low.

Complications and readmission rate

The level of evidence regarding these outcome measures comes from observational studies and therefore starts at low. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1). The level of evidence is therefore very low.

Quality of life and functional recovery

The level of evidence could not be graded for these outcome measures as they were not reported in the included studies.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the value of an ERAS® program in adult patients who have undergone an anatomical lung resection?

P: patients patients who have undergone an anatomical lung

resection

I: intervention ERAS® program

C: control no ERAS® program (pre-ERAS®)

O: outcome measure mortality, complications, postoperative length of stay,

readmission rate, quality of life, functional recovery

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered mortality and complications as critical outcome measure for decision-making, and postoperative complications, quality of life, length of stay, readmission rate, quality of life, and functional recovery as an important outcome measure for decision-making.

Quality of life and functional outcomes are considered highly relevant, but only sparsely reported. Traditionally, clinical outcome measures mortality and complications are used to assess complex, multimodal preoperative care pathways and used as critical outcome measures for decision making; postoperative hospital length of stay and readmission rates are consequences of the quality of preoperative care, rather than direct effects. These outcome measures, as a proxy for quality of perioperative care, are considered important outcome measures for decision-making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following differences as a minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

- Mortality: 10% (RR < 0.9 or RR > 1.1)

- Complications: 10% (RR < 0.9 or RR > 1.1)

- Postoperative length of stay: 1 day

- Readmission rate: 10% (RR < 0.9 or RR > 1.1)

- For quality of life and functional recovery: based on previously described minimal clinically important differences per assessment tool.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 16-03-2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 402 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and comparative studies that compared an ERAS®program versus no ERAS® program in adult patients who have undergone an anatomical lung resection. In total 43 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 33 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 10 studies were included.

Results

Ten studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Batchelor TJP, Rasburn NJ, Abdelnour-Berchtold E, Brunelli A, Cerfolio RJ, Gonzalez M, Ljungqvist O, Petersen RH, Popescu WM, Slinger PD, Naidu B. Guidelines for enhanced recovery after lung surgery: recommendations of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019 Jan 1;55(1):91-115. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezy301. PMID: 30304509.

- Bellas-Cotán S, Casans-Francés R, Ibáñez C, Muguruza I, Muñoz-Alameda LE. Implementation of an ERAS program in patients undergoing thoracic surgery at a third-level university hospital: an ambispective cohort study. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2021 Apr 27:S0104-0014(21)00174-3. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2021.04.014. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33930342.

- Del Calvo H, Nguyen DT, Meisenbach LM, Chihara R, Chan EY, Graviss EA, Kim MP. Pre-emptive pain management program is associated with reduction of opioid prescription after minimally invasive pulmonary resection. J Thorac Dis. 2020 May;12(5):1982-1990. doi: 10.21037/jtd-20-431. PMID: 32642101; PMCID: PMC7330317.

- Forster C, Doucet V, Perentes JY, Abdelnour-Berchtold E, Zellweger M, Faouzi M, Bouchaab H, Peters S, Marcucci C, Krueger T, Rosner L, Gonzalez M. Impact of an enhanced recovery after surgery pathway on thoracoscopic lobectomy outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer patients: a propensity score-matched study. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021 Jan;10(1):93-103. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-20-891. PMID: 33569296; PMCID: PMC7867780.

- Francis NK, Walker T, Carter F, Hübner M, Balfour A, Jakobsen DH, Burch J, Wasylak T, Demartines N, Lobo DN, Addor V, Ljungqvist O. Consensus on Training and Implementation of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: A Delphi Study. World J Surg. 2018 Jul;42(7):1919-1928. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-4436-2. PMID: 29302724.

- Khoury AL, Kolarczyk LM, Strassle PD, Feltner C, Hance LM, Teeter EG, Haithcock BE, Long JM. Thoracic Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: Single Academic Center Observations After Implementation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021 Mar;111(3):1036-1043. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.06.021. Epub 2020 Aug 14. PMID: 32805268.

- Li R, Wang K, Qu C, Qi W, Fang T, Yue W, Tian H. The effect of the enhanced recovery after surgery program on lung cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2021 Jun;13(6):3566-3586. doi: 10.21037/jtd-21-433. PMID: 34277051; PMCID: PMC8264698.

- Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2017 Mar 1;152(3):292-298. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4952. PMID: 28097305.

- Meyenfeldt EMV, van Nassau F, de Betue CTI, Barberio L, Schreurs WH, Marres GMH, Bonjer HJ, Anema J. Implementing an enhanced recovery after thoracic surgery programme in the Netherlands: a qualitative study investigating facilitators and barriers for implementation. BMJ Open. 2022 Jan 5;12(1):e051513. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051513. PMID: 34987041; PMCID: PMC8734011.

- Ni H, Li P, Meng Z, Huang T, Shi L, Ni B. Discussion of the experience and improvement of an enhanced recovery after surgery procedure for minimally invasive lobectomy: a cohort study. Ann Transl Med. 2021 Dec;9(24):1792. doi: 10.21037/atm-21-6493. PMID: 35071486; PMCID: PMC8756218.

- Peng T, Shemanski KA, Ding L, David EA, Kim AW, Kim M, Lieu DK, Wightman SC, Zhao J, Atay SM. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol Minimizes Intensive Care Unit Utilization and Improves Outcomes Following Pulmonary Resection. World J Surg. 2021 Oct;45(10):2955-2963. doi: 10.1007/s00268-021-06259-1. Epub 2021 Aug 4. PMID: 34350489; PMCID: PMC8336670.

- Senturk JC, Kristo G, Gold J, Bleday R, Whang E. The Development of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Across Surgical Specialties. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2017 Sep;27(9):863-870. doi: 10.1089/lap.2017.0317. Epub 2017 Aug 10. PMID: 28795911.

- Stone AB, Yuan CT, Rosen MA, Grant MC, Benishek LE, Hanahan E, Lubomski LH, Ko C, Wick EC. Barriers to and Facilitators of Implementing Enhanced Recovery Pathways Using an Implementation Framework: A Systematic Review. JAMA Surg. 2018 Mar 1;153(3):270-279. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5565. PMID: 29344622.

- Tiberi M, Andolfi M, Salati M, Roncon A, Guiducci GM, Falcetta S, Ambrosi L, Refai M. Impact of enhanced pathway of care in uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Updates Surg. 2022 Jun;74(3):1097-1103. doi: 10.1007/s13304-021-01217-x. Epub 2022 Jan 11. PMID: 35013903.

- Wang C, Lai Y, Li P, Su J, Che G. Influence of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) on patients receiving lung resection: a retrospective study of 1749 cases. BMC Surg. 2021 Mar 6;21(1):115. doi: 10.1186/s12893-020-00960-z. PMID: 33676488; PMCID: PMC7936477.

- Wu Y, Xu M, Ma Y. Fast-track surgery in single-hole thoracoscopic radical resection of lung cancer. J BUON. 2020 Jul-Aug;25(4):1745-1752. PMID: 33099909.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables

Research question: What is the value of an ERAS program in adult patients who have undergone an anatomical lung resection?

Systematic review

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Li, 2021

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs / cohort / case-control studies.

Literature search up to October 2020

A: Dong, 2017 B: Muehling, 2008 C: Boujibar, 2018 D: Brunelli, 2017 E: Chen, 2020 F: Gao, 2015 G: Glogowaska, 2017 H: Gonzales, 2018 I: Haro, G 2019 J: Huang, 2018 K: Khandhar, 2018 L: Li, M, 2019 M: Lv, H 2019 N: Madani, 2015 O: Murayama, 2006 P: Numan, 2012 Q: Rice D, 2020 R: Salati, 2020 S:Shiono, 2019 T: Tahiri, 2020 U: van Haren, 2018

Study design: A: RCT B: RCT C: cohort (retrosp.) D: cohort (retrosp.) E: cohort (retrosp.) F: cohort (prosp.) G: cohort (prosp.) H: cohort (ambisp.) I: cohort (prosp.) J: cohort (retrosp.) K: cohort (retrosp.) L: cohort (retrosp.) M: cohort (prosp.) N: cohort (retrosp.) O: cohort (retrosp.) P: cohort (prosp.) Q: cohort (retrosp.) R: cohort (retrosp.) S: cohort (retrosp.) T: cohort (retrosp.) U: cohort (retrosp.)

Setting and Country: A: China B: Germany C: France D: UK E: China F: China G: Poland H: Switzerland I: USA J: China K: USA L: China M: China N: Canada O: Japan P: Netherlands Q: USA R: Italy S: Japan T: Canada U: USA

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 8162292, 81802397), the Jinan Science and Technology Bureau (no. 2019GXRC051), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (no. ZR2017BH035), and the Taishan Scholar Program of Shandong Province (no. ts201712087).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. |

Inclusion criteria SR: (I) involved adult patients undergoing elective pulmonary resection (wedge resection, lobectomy, pneumonectomy, etc.), (II) involved patients who received an ERAS program (we recognized a total of 25 elements in studies encompassing all phases of perioperative care [pre-, intra-, and postoperative] (III) involved an ERAS program with at least 4 elements that covered at least 2 phases of perioperative care, (IV) involved a traditional care control group that had adopted at least 3 elements fewer than the ERAS group, (V) reported at least 1 of the outcome measures of interests (see below), and (VI) written in English.

Exclusion criteria SR: (I) ineligible article types, such as case report, reviews, and conference abstracts; (II) no outcomes of interest present; (III) inclusion of nonhuman participants or written in languages other than English.

21 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N (ERAS versus control) A: 17, 18 B: 30, 28 C: 19, 15 D: 235, 365 E: 169, 168 F: 71, 71 G: 215, 187 H: 50, 50 I: 126, 169 J: 38, 45 K: 304, 100 L: 72, 72 M: 55, 55 N: 107, 127 O: 113, 105 P: 75, 94 Q: 123, 123 R: 232, 232 S:126, 126 T: 98, 98 U: 342, 1615

Mean age (ERAS versus control) A: 55.1, 56.5 B: 67, 64 C: 65, 69 D: 69.7, 68.8 E: 57.6, 57.2 F: 66.3, 59.7 G: 59, 55 H: 64, 68 I: 67, 67 J: 60.7, 59.6 K: 66.2, 66.2 L: 63.1, 63.5 M: 57.1, 56.8 N: 67, 64 O: 63, 64 P: 60, 58 Q: 62, 61 R: 68.2, 67.7 S: 70, 70 T: 65.2, 66.2 U: 66, 65

Sex (% male ERAS versus control) A: 76, 78 B: 66.7, 82.1 C: 78.9, 66.6 D: 42, 40 E: 65.1, 64.9 F: 56.3, 62.0 G: 52.6, 54.5 H: 48, 36 I: 31.0, 43.8 J: 42.1, 55.6 K: 58.6, 53.0 L: 58.3, 55.6 M: 56.4, 63.6 N: 61, 45 O: 58.4, 50.5 P: 57.3, 58.5 Q: 53, 54 R: NR, NR S: 66.7, 68.3 T: 36.7, 29.6 U: 47.4, 50

ERAS elements (ERAS versus control) A: 14, 8 B: 7, 4 C: 5, 2 D: 15, 8 E: 7, 4 F: 6, 3 G: 5, 1 H: 16, 10 I: 17, 5 J: 22, 5 K: 11, 2 L: 6, 3 M: 10, 2 N: 10, 3 O: 9, 3 P: 8, 0 Q: 11, 5 R: 5, 0 S: 11, 5 T: 6, 1 U: 10, 5 |

Describe intervention:

ERAS protocol (at least 4 elements that covered at least 2 phases of perioperative care.

|

Describe control:

Pre-ERAS (at least 3 elements fewer than the ERAS group).

|

End-point of follow-up: Not reported.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported.

|

Outcome measure-1 In-hospital mortality Pooled effect (random effects model): The pooled RD of all 13 studies was -0.00 (95% CI: -0.01 to 0.00). I² 0%.

Outcome measure-2 Postoperative complications Pooled effect (random effects model): The pooled RR of all 18 studies was 0.64 (95% CI: 0.52 to 0.78). I² 63%.

Outcome measure-3 Postoperative length of stay Pooled effect (random effects model): The pooled SMD of all 7 studies was -1.58 (95% CI: -2.38 to -0.79;. I² 98%.

Outcome measure-4 Readmission rate Pooled effect (random effects model): The pooled RR of all 11 studies was 1.00 (95% CI: 0.76 to 1.32). I² 0%.

Outcome measure-5 Quality of life Not reported.

Outcome measure-6 Functional recovery Not reported.

|

Facultative: Through this meta-analysis, we found that patients treated with the ERAS program had a lower risk of developing postoperative complications and a decreased postoperative LOS.

No publication bias was found using both Begg’s test and Egger’s test.

To explore the source of high heterogeneity (postoperative complications), we omitted the individual studies sequentially (27). Fortunately, we found a significantly reduced heterogeneity after excluding the studies performed by Gao et al. in 2015 I2= 35%; P=0.08), as shown in Figure 4.

This review had some limitations. First, the majority of the included studies were cohort studies, and only 2 RCTs were included. Moreover, the majority of eligible cohort studies were separate-sample pre-post-test designs. These types of studies have some limitations, such as nonparallel controls and cohort selection, which might have introduced biases and reduced the reliability of the results. Second, the ERAS protocols of the included studies were significantly different, and the implementation standards of the ERAS program varied between each country and region, possibly producing bias and reducing the credibility of the results. In addition, there were differences in patient compliance with the ERAS program (64,65), which might have led to obvious heterogeneity in the results. Third, we did not analyze patient-reported outcomes such as pain score and QoL because published research did not provide these types of data. |

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Li, 2021 |

Yes |

Yes |

No

The studies that are excluded after reading the full tekst are not referenced with reasons. |

Yes |

Unclear

Not reported. |

Yes

|

No

The amount of ERAS items differ substantially between the studies and the implementation standards of the ERAS program varied between each country and region. |

Yes

No publication bias. |

Yes

No conflicts of interest reported. |

Observational studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Wang, 2021 |

Type of study: cohort

Setting and country: retrospective, China

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Funding was not applicable. |

Inclusion criteria: (1) diagnosis with primary non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC); (2) anatomical lung resection, including lobectomy and segmentectomy; and (3) ≥18 years old.

Exclusion criteria: (1) benign lesions or other pathological types except NSCLC; (2) other surgical approaches except anatomical lung resection;

N total at baseline: Intervention: 691 Control: 1058

Important prognostic factors2: For example age (IQR) I: 61.0 (56.0, 67.0) C: 61.0 (53.0, 68.0)

Sex (M/F): I: 351 / 340 C: 527 / 531

Groups comparable at baseline?

Compared with the routine pathway group, the ERAS group was found to have a higher proportion of VATS. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

ERAS protocol: - General patient admission education, instruction about ERAS principles and ERAS member responses to the patients. The specialized nurse was mainly responsible for the session. Smoking and alcohol cessation for 2 weeks and 4 weeks respectively. - Perioperative respiratory training and mobilization. - VTE prophylaxis education preopeartive VTE risk rating, early mobilization after surgery. - small-bore chest tubes, drain removed < 400 ml and no air flow. - no urinary catheter - standardized postoperative pain management - early oral intake, median chain triglyceride diet suppoted by the nutriology department.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Pre-ERAS protocol (routine pathway): - General patient admission education introduced by video - No perioperative respiratory training and mobilization - No standardized VTE management - chest tube management: 2 28-F chest tube; removal after drainage volume < 200 - routine urinary catheter was used - non-standardized postoperative pain management. - non-standardized postoperative nutrition management. |

Length of follow-up: Not reported

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality I: 4/691 (0.6%) C: 6/1058 (0.6%)

Overall postoperative complications Not reported.

length of stay (postoperative) I: 4.0 (IQR 2, 6) C: 6.0 (IQR 4, 9)

readmissions not reported

quality of life not reported

functional recovery not reported |

Conclusion: Implementation of an ERAS pathway shows improved postoperative outcomes, including shortened LOS, lower in-hospital costs, and reduced occurrence of PPCs, providing benefits to the postoperative recovery of patients with lung cancer undergoing surgical treatment. |

|

Peng, 2021 |

Type of study: cohort

Setting and country: retrospective, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding Was provided By grants UL1TR001855 and UL1TR000130 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) of the US National Institutes of Health for Dr. Ding.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. |

Inclusion criteria: All patients undergoing anatomic lung resection between April 2017 and April 2019.

Exclusion criteria: Incomplete datasets, extended resections (pneumonectomy), or non-resectional operations.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 67 Control: 64

Important prognostic factors2: For example age (range): I: 64.0 (21-86) C: 64.5 (26-89)

Sex: I: 61.2% M C: 50 % M

Open Surgery: I: 40.3 % C: 28.1%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

ERAS protocol: - early mobilization - limited invasive monitoring - euvolemia - non-narcotic analgesia - intraoperative regional blocks instead of thoracic epidurals.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Pre-ERAS Not described. |

Length of follow-up: 30 days

Loss-to-follow-up: NA – incomplete datasets were excluded on beforehand.

Incomplete outcome data: NA – incomplete datasets were excluded on beforehand.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality None of the patients died within 30 days after surgery in both the intervention and control group.

Overall complications Not reported.

length of stay (hospital) not reported, only hospital length of stay.

Readmissions (within 30 days) I: 6 (9%) C: 3 (4.7%)

quality of life Not reported.

functional recovery Not reported. |

Conclusion: Implementation of an ERAS protocol for pulmonary resection, which dictated reduced ICU admissions, did not increase major postoperative morbidity. Additionally, ERAS-enrolled patients reported improved postoperative pain control despite decreased opioid utilization.

There was no transitional period after introduction of the institutional ERAS protocol, and all surgeons immediately and unanimously participated in its use.

Supplemental material laat zien dat het voldoet aan de criteria van het SR van Li 2021 wat betreft de ERAS elementen. |

|

Forster, 2021 |

Type of study: cohort

Setting and country: retrospective,

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

|

Inclusion criteria: adult patients (age ≥18 years) with NSCLC of any stage who underwent a VATS lobectomy between January 2014 and October 2019 in our institution.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with intra-operative conversion to thoracotomy, patients presenting metastatic lesions, and patients with emergency procedures were excluded.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 140 Control: 167

Important prognostic factors2: For example age median (IQR): I: 67 (59 – 72) C:67 (60 – 74)

Sex: I: 47.1% M C: 58.7% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

ERAS protocol - information by clinical nurse, information booklet. - two packs of carbohydrate drink the day before the operation, one pack 2 hours before surgery and 3 pack per day during post-operatieve hospitalization. - no preoperative sedation. - LMWH VTE prophylaxis - induction of antbiotic prophylaxis - intercostal nerve block with bupivacaine and IV perfusion of NSAID and paracetamol; propofol or halogenated anaesthetics gases - intraoperative warming - avoidance of fluid overload - no urinary catheter - single chest tube, electronic drainage system, suction -20 H2) - early removal of the chest tube if no air leak over 6 hours and < 400 ml/24h. - paracetamol, NSAIDs, morphine, tramadol (after chest tube removal) - prophylaxis with ondansetron, decamethasone 21-phosphate disodium - early feeding - mobilization within 24 hours - postoperatieve transfer to continous care reserved for cardio-pulmonary comorbidities, or difficulty to mobilize.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Pre-ERAS - no education - no carbohydrate drink - preoperative sedation - LMWH VTE prophylaxis - induction of antbiotic prophylaxis - epidural catheter or intercostal nerve block with bupivacaine, opioids, paracetamol; halogenated anaesthethics gases or propofol - intraoperative warming - no standardized avoidance of fluid overload - urinary catheter only if epidural catheter - one or two chest tubes, digital chest drainage or water seal, suction -20 cmH2), drain removed if no air leak over 6 hours and < 250 ml/24h - post-operative analgesia: paracetamol, fixed doses morphine s.c. tramadol (after chest tube removal). - PONV not standardized - early feeding - no standardized mobilization within 24 hours. - routinely post-operative transfer to the continuous care.

|

Length of follow-up: 30 days after surgery.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality Not reported.

Overall complications I: 41/140 C: 61/167 Propensity score-matched average treatment effect: -0.13 (-0.25, -000.3).

Postoperative length of stay Not reported.

Readmissions (30-day) I: 5 (3.6%) C: 9 (5.4%)

quality of life not reported.

Functional recovery Not reported. |

All patients received VATS |

|

Ni, 2021 |

Type of study: cohort

Setting and country: retrospective, China

Funding and conflicts of interest: no funding. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. |

Inclusion criteria: All patients that underwent thoracoscopic lobectomy were eligible for inclusion

Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded if they received secondary surgery due to complications, lack of perioperative related clinical data, formulated perioperative rehabilitation management regulations were not strictly followed during the perioperative period, patients who had refused early discharge.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 508 Control: 629

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 60.5 (18.8) C: 62.9 (16.3)

Sex: I: 57.1% M C: 59.5% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

ERAS protocol: Pre-operative: (I) Detailed preoperative education to make patients aware of the rapid recovery process and cooperation matters; (II) NSAIDs COX-2 inhibitor was taken orally 2 days before surgery; (III) correct anemia, lung function training, nutrition support; (IV) 400 mL of carbohydrate was added to clear fluid 2 h before surgery; (V) avoid sedative-hypnotic drugs before surgery; (VI) adjust the preoperative anticoagulation program; (VII) risk assessment of venous thromboembolism; (VIII) nutritional status assessment

Intraoperative: I) Preoperative prophylactic use of antibiotics; (II) protective lung ventilation strategy and body temperature protection measures; (III) the catheter was removed without indwelling or after surgery; (IV) endoscopic vision of the lower intercostal nerve block; (V) carefully expand the lung to suture air 28# leakage and hemostasis before closing the chest cavity; (VI) all chest tubes were placed at the top of the chest for drainage; (VII) intraoperative intravenous fluid supply was limited to about 500 mL, and postoperative daily fluid supply was less than 1,000 mL

Postoperative: (I) Intravenous NSAIDs COX-2 inhibitors were used every 12 h for the first 3 days after surgery, and oral administration continued for 4 days on the fourth day; (II) start to get out of bed 6 h after the operation, and set the postoperative walking amount; (III) control intravenous fluids; (IV) prevent nausea and vomiting; (V) early removal of chest tube (<500 mL/d); (VI) prevention of deep vein thrombosis; (VII) get out of bed on the day after the operation. On the first day after the operation, get out of bed with chest tube twice a day, 6 min/200 m or more each time; (VIII) use a breathing trainer.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

No ERAS protocol: Pre-operative: I) Preoperative fasting and drinking were forbidden for more than 6 h; (II) anxious patients could be administered preoperative sedative sleep and other drugs.

Intraoperative: (I) Preoperative prophylactic administration of antibiotics; (II) preoperative indwelling catheter and return to ward; (III) minimally invasive surgery; (IV) superior lobectomy was performed with two roots, and middle and lower lobectomy was performed 28# with a single thoracic duct drainage; (V) intraoperative fluid supply was 1,000 mL, and postoperative fluid supply was 1,500 mL/d

Postoperative: (I) On demand opioid intramuscular analgesia; (II) prevention of excessive vomiting; (III) the chest tube was removed after <200 mL/d; (IV) do not restrict intravenous fluid, according to the patient’s will to get out of bed, strengthen cough to promote cough; (V) prevention of deep vein thrombosis; (VI) stepped-up routine back patting for expectoration. |

Length of follow-up: Not reported.

Loss-to-follow-up: NA – only complete datasets were included.

Incomplete outcome data: NA – only complete datasets were included.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

mortality not reported.

complications I: 69/508 C: 116/629

Length of stay (d) I: 2.74 (0.80) C: 5.70 (1.10)

Readmissions I: 2 (group A+B+C) C:1 (group B+C)

quality of life not reported.

functional recovery not reported. |

|

|

Khoury, 2021 |

Type of study: cohort

Setting and country: retrospective, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: adult patients undergoing pulmonary resections (wedge resection, segmentectomy, lobectomy and bilobectomy).

Exclusion criteria: Only a patient’s first thoracic operation was eligible, redo surgeries and unexpected returns to the operation room were excluded, as well as trauma patients. Patients were also excluded when they simultaneously underwent esophagectomy, pneumonectomy, or coronary artery bypass grafting.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 131 Control: 133

Important prognostic factors2: For example age (IQR): I: 61 (54-68) C: 64 (55-70)

Sex: I: 38 % M C: 50% % M

Groups comparable at baseline? Post-ERAS patients were less likely to be male and more likely to have preoperative or longstanding steroid use.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

ERAS protocol: Preoperative - Tobacco cessation Incentive spirometry education - Preoperative nutritional screening and oral carbohydrate loading

Day of surgery: - Preoperative medications: Tylenol 1000 mg PO, Celebrex 200 mg PO, Pregabalin 100 mg PO - Consumption of clear fluids up until 2 h before surgery.

Intraoperative Analgesia (VATS/RATS): 1. Intercostal blocks (T2-T10 levels) with 1:1 mix of 0.25% plain bupivacaine liposomal bupivacaine. 2. Ketamine infusion: 0.25 mg kg h

Analgesia (thoracotomy): Thoracic epidural: 0.25% plain bupivacaine infusion, 3-6 mL/h Fluids: Establish and maintain euvolemia; frequent arterial blood gas interpretation. Blood pressure: Maintain systolic blood pressure >20% baseline. Vasopressin 0.02-0.04 units kg h first line;

norepinepherine 0.02-0.04 mg kg min second line.

Mechanical ventilation: Pressure control ventilation Recruitment breaths q30min 2 lung: tidal volume 5-8 mL/kg (3-5 for ESLD) IBW, FiO2 <0.5 if possible, PEEP 5 1 lung: tidal volume 4-7 mL/kg IBW, FiO2 1.0 and wean by 0.1 q5min, PEEP 5-8 (3-5 for ESLD) Respiratory rate: Keep PaCO2 within 10 mm Hg of baseline Antibiotic prophylaxis Prevention of Postoperative Nausea with Dexamethasone Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis Prevention of intraoperative hypothermia Minimally invasive surgical technique (VATS, RATS) or muscle-sparing and nerve-sparing techniques for thoracotomy

postoperative Analgesia (VATS/RATS): - NSAIDs-scheduled - Ketorolac 15 mg IV q8h or ibuprofen 800 mg PO q8h 24 h on POD 0. - Transition to Ibuprofen 600 mg PO q6hr PRN on POD 1 and until discharge. - Gabapentin 300 mg PO TID until discharge. - Tylenol 650 mg PO QID Until discharge. Early mobilization Early chest tube removal (24-h output <250 mL and no air leak) Early urinary catheter removal. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Pre-ERAS Not described. |

Length of follow-up: 30 days

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Strength of the study is minimal missing data. No details reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality I: 2 (2%) C: 0 (0%)

Complications (any) I: 44 (34%) C: 36 (27%)

Postoperative length of stay Not reported.

readmissions I: 13 (10%) C: 11 (8%)

quality of life not reported

functional recovery not reported. |

Conclusion: In the first year of implementation, median LOS, complications, and 30-day outcomes did not differ significantly between the pre-ERAS and post- ERAS groups. |

|

Tiberi, 2022 |

Type of study: cohort

Setting and country: retrospective, Italy

Funding and conflicts of interest: |

Inclusion criteria: Patients were considered eligible for inclusion in E.P.C. program if: = 18 years of age, American Society of Anesthesiologists score = 3, and scheduled for elective surgery.

Exclusion criteria: patients undergoing pneumonectomy, conversion to open surgery, planned postoperative intensive-care monitoring, lack of care-giver, inability to collaborate (language barriers, psychiatric pathology).

N total at baseline: Intervention: 182 Control: 182

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 66.2 (10.1) C: 66.7 (9.8)

Sex: I: 56% M C: 53.3% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes (matched)

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

ERAS protocol - preoperative: patients meets the multidisciplinairy team and were informed about all aspects. In particular, preoperative behavioral changes were persecuted requiring smoking cessation and implmeneting physical activity and nutriotnal programs. Patietns were screened for nutritional status and oral nutrition supplements were given if malnourished. Patients received specific chest physiotherapy instruction and a home training protocol was delivered. Patients received a booklet describing all aspects and the procedures included in the program.

- perioperative: antibiotic and venous thromboembolism were optimized and standardized. Procedrures aimed at preventing hypothermia were implemented, including the use of hot air warming blankets and thermic mattresses. Standard monitoring of vital signs was applied in all patients and it was implemented by the applicaiton of BIS for hypnosis depth and TOF for the depth of miorisolulution in EPC. Anesthesia was inducted by the administration of Propofol 1–2 mg/kg, Rocuronium 1.2 mg/kg and Fentanyl 3 mcg/kg, followed by continuous administration of desflurane and remifentanil for the maintenance. Sugammadex 100–200 mg was administered at the end of intervention, based on TOF monitoring, to prevent a Post-Operative Residual Curarisation syndrome. It was provided for a “protective” One Lung of the dependent lung in the E.P.C. group characterized by a tidal volume of 4–5 ml/kg, respiratory rate of 10 Breaths/min and a PEEP of 5 cmH2O.

Perioperative and operative protocols for opioid-free pain management were systematically adopted in the E.P.C. group, based on specific loco-regional anesthetic techniques such as paravertebral thoracic (T5) erector spinae plane block by the anesthetist associated with local wound infiltration with ropivacaine 0.75% by the surgeon. Monitoring by urinary and arterial catheter was exclusively reserved to patients undergoing anatomical resections and removed the morning after surgery. All patients were extubated at the end of the procedure and transferred to thoracic surgery ward if clinically stable after a 30 min period of monitoring in the preoperative room.

- postoperative: Early mobilization of the patients and postoperative chest physiotherapy program started 4–6 h after surgery as well as the oral intake of fluid and solid foods. Opioid-free pain management was maintained during the postoperative phase, switching from fractionated intravenous to oral painkillers administration as soon as possible. The use of paravertebral or peri-dural catheters were avoided. In the early first post operative day, any form of monitoring was suspended unless for complicated patients. Twice daily the expected goals and the achievements of each day were discussed among patients and all the components of the multidisciplinary team. The single tube was removed in the second postoperative day if no air leak was registered during the previous 12 h by a digital chest drainage system and pleural effusion was less than 400 ml/24 h. In case of persistent air leak during the third postoperative day, the patient was discharged with a chest tube connected to a portable chest drainage device, as previously discussed and agreed during the preoperative counseling.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Pre-ERAS Not described. |

Length of follow-up: 30 days after the operation

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality Not reported.

Overall complications Not reported, only cardiopulmonary complications.

Postoperative length of stay mean (SD) Not reported.

Readmissions I: 3 (1.6%) C: 9 (4.9%)

quality of life not reported.

functional recovery not reported |

|

|

Bellas-Cotán (2021) |

Type of study: cohort

Setting and country: ambispective (prospective ERAS, retrospective control), Spain

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: patients undergoing lobectomy

Exclusion criteria: Patients who refused to take part or were under 18 years of age.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 50 Control: 50

Important prognostic factors2: For example age (IQR) I: 64 (57 – 70.8) C: 64.5 (53.5 – 70)

Sex: I: 50% M C: 62% M

Groups comparable at baseline? A higher number of patients in the standard cohort had hypertension and COPD. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

ERAS Our center’s ERAS program includes different strate- gies for the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative periods. During the preoperative period, the patients and their families received comprehensive multidisciplinary information about the protocol, the steps to be taken during each day of hospitalization, and the expected discharge date. Patients were taught a series of pulmonary expan- sion exercises to be performed until surgery by a team specialized in treating lung diseases. Smoking cessation interventions and nutritional screening were also performed at this stage.

Patients underwent VATS whenever possible, placing a chest tube for drainage at the end of the surgery. All subjects received antibiotics and antithrombotic prophylaxis. We performed general anesthesia combined with regional techniques for pain control, avoiding benzodi- azepines and opioids. The anesthesiologist was free to choose between thoracic epidural analgesia, intercostal block, and erector spinae block. If a thoracic epidural catheter was placed, it was left in for postoperative patient-controlled analgesia. We also used a hot air system to warm patients during surgery to maintain normothermia. In both groups, no more than 2 mL.kg-1.h-1fluids were administered. Extubation was performed as soon as possible after the end of the surgery, and we encouraged early removal of the urinary catheter.

After extubation, patients started oral intake, respira- tory physiotherapy exercises, and early ambulation. Patients were discharged when they were free of complications, without severe pain, and the urinary catheter or chest tube had been removed.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Standard care (not specified)

None of the patients in either group fasted for more than 2 hours before surgery. |

Length of follow-up: We followed up patients for 30 days after surgery using hospital and primary care medical records.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality I: 0 (0%) C: 2 (4%)

Overall complications Not reported, surgical complications and other complications are reported separately. unknown whether this is in different patients.

Postoperative length of stay not reported.

readmissions I: 6 (12%) C: 15 (30%)

quality of life not reported

functional recovery not reported |

|

|

Del Calvo, 2020 |

Type of study: case-control

Setting and country: retrospective, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. |

Inclusion criteria: All patients who underwent elective minimally invasive pulmonary resection.

Exclusion criteria: diagnostic wedge procedures, emergent or urgent pulmonary resections, and pulmonary resections as part of the “two-step” procedure for cardiac sarcoma with pulmonary resection.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 90 Control: 221

Important prognostic factors2: For example age (IQR) I: 67 (58-73) C: 67 (57-73)

Sex: I: 60% F C: 52.5% F

Groups comparable at baseline? There was a higher number of patients with diabetes in the control group. There was a significant higher number of patients in the ERS group compared to control who underwent robot assisted surgery. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

ERAS protocol The pre-operative stage was developed to get the patient ready for surgery, with an emphasis on quitting smoking, learning to use the incentive spirometer, and walking 1 mile per day.

The operative stage included intravenous anesthesia, minimizing fluids and minimally invasive surgery. In addition, all patients received a direct injection of undiluted liposomal bupivacaine block of the 2nd to 10th intercostal nerves from inside of the chest cavity.

The post-operative stage included an around-the Clock scheduled analgesic and emphasis on early mobility, including an incentive spirometer. We also transitioned to prescribing tramadol as a default discharge pain medication for all patients at discharge from hydrocodone/ acetaminophen.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Control No pre-operative regimen No intra-operative regimen Post-operative regimen: hydromorphone PCA Default discharge medication: hydrocodone / acetaminophen. |

Length of follow-up: 4 weeks after surgery

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality Not reported

Overall complications I: 21 (23.3%) C: 84 (38%)

Postoperative length of stay not reported.

readmissions I: 3 (3.3%) C: 25 (11.3%)

quality of life not reported

functional recovery not reported |

|

|

Wu, 2020 |

Type of study: cohort

Setting and country: retrospective, China

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding is not reported. The authors declare no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: 1) patients definitely diagnosed with lung cancer through preoperative fiberopti bronchoscopy or intraoperative frozen pathology and receiving no radiotherapy or chemotherapy; 2) those who could tolerate surgery based on the physical status, with the Karnofsky Performance Score (KPS) score =70 points; 3) those who were able to tolerate surgery according to heart and lung functions and had basically normal liver and kidney functions; and 4) those who had no metastases or severe diseases of other organ systems as indicated by whole-body PET or CT examinations.

Exclusion criteria: 1) patients with tumors which were too large or involved the vessels and trachea; 2) those with cancer cells found in the pleural effusion; 3) those who encountered conversion to thoracotomy since extensive pleural adhesions were found intraoperatively; 4) those for whom single-hole thoracoscopic surgery was converted to thoracotomy due to uncontrolled intraoperative bleeding; 5) those with distant metastases or severe anemia; 6) those complicated with severe heart, lung, liver or kidney dysfunction; 7) those complicated with other malignancies; or 8) those with poor compliance.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 76 Control: 76

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 65.11 (10.43) C: 63.94 (10.59)

Sex (M/F): I: 41/35 C: 46/30

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

- preoperative health education and mental support were completed.

- before operation, patients were informed, physical exercise and respiratory function exercise were performed, malnourished patients were given appropriate nutritional support, all patients were fasted for food 6h before operation, allowed to drink 300-500 ml of water 4h before operation and IV dripped with antibiotics 30 min before operation.

- intraoperative: The patients were kept warm during routine disinfection and generally anesthetized using drugs with a short half-life. The incision was protected by an incision protection sleeve, and the operations should be gentle to avoid excessively pulling and squeezing lung tissues. Moreover, restricted fluid infusion was conducted, with the fluid volume <1,000 mL, and vasoactive drugs were used to raise the blood pressure. Finally, a pleural drainage catheter was indwelled and led out from the incision.

- postoperative: On the day of operation, the patients were instructed to do sit-ups on the bed for 2-3 times. Additionally, they were encouraged to actively move their lower limbs or their family members massaged the patients’ lower limb muscles, combined with the adjutant pneumatic pump therapy, to prevent deep-vein thrombosis. At 6 h after operation, the patients were given water and liquid food

- day 1 postoperative: the patients ate normally eat in the morning, and they were encouraged to get off bed and ambulate for 4-6 times (about 10 min/time). The ambulation time was extended 2 days after operation. Additionally, the patient-controlled analgesia pump was applied to ease pain, and the patients were encouraged to cough and expectorate.

- extubation indications: The chest tube was squeezed once every 30 min to avoid blocking tube opening and ensure the smooth drainage of intrapleural fluid thereby accelerating the recovery of pulmonary function. Finally, the tube was removed when there was no air leak of the closed thoracic drainage bottle, and no bloody, chylous or purulent pleural effusion, X-ray chest imaging indicated favorable lung recruitment, with the 24 h-pleural drainage volume <200 mL, and the postoperative daily intravenous fluid infusion was controlled to be <800 mL.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

- patients and their family members were informed of the preoperative smoking cessation and breathing exercise.

- day 1 before operation: patients and family were routinely informed and on the evening the patients ate liquid food.

- 10h before operation patients deprived of food and water.

- intraoperatively: blood volume was routinely enlarged to increase BP.

- 24h after surgery: patients were given food and water, analgesics and provided with rehabilitation guidance.

- extubation indications: no air leak, pleural effusion was not bloody, chylous or purulent, chest x-ray imaged indicated complete lung recruitment, pleural drainage volume <100 ml. |

Length of follow-up: Not reported.

Loss-to-follow-up: Unknown, not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Unknown, not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality Not reported.

Overall complications not reported, complications are reported separately. However unknown if they occurred in the same patients. Length of stay (postoperative) I: 5.2 (+/-0.8) C: 7.2 (+/-1.1)

Readmissions Not reported

Quality of life Not reported

Functional recovery Not reported. |

|

|

Author, year |

Selection of participants

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population?

|

Exposure

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?

|

Outcome of interest

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study?

|

Confounding-assessment

Can we be confident in the assessment of confounding factors?

|

Confounding-analysis

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these confounding variables? |

Assessment of outcome

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome?

|

Follow up

Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? In particular, was outcome data complete or imputed?

|

Co-interventions

Were co-interventions similar between groups?

|

Overall Risk of bias

|

|

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Low, Some concerns, High |

|

|

Wang, 2021 |

Definitely no

Reason: Participants were selected from different time periods. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Protocols differed significantly, washout period was applied. |

Probably yes

Reason: however patients with previous lung resections were not excluded on beforehand. |

Probably yes

Reason: data was collected from hospital records, similar data was obtained for both time periods. |

Probably yes

Reason: multivariable analyses were performed to assess the risk to postoperative pulmonary comlications. |

Probably yes

Reason: data was obtained from medical records. |

Unclear

Reason: Nothing was reported on follow-up. |

Definitely no

Reason: The surgical approach was different between the groups (more VATS versus open) which may have biased the results. |

High (all outcomes)

|

|

Tiberi, 2022 |

Definitely no

Reason: Participants were selected from different time periods. |

Probably no

Reason: No transition period was used.

|

Probably yes

Reason: however patients with previous lung resections were not excluded on beforehand. |

Probably yes

Reason: data was collected from hospital records, similar data was obtained for both time periods. |

Probably yes

Reason: propensity-score matching was used to adjust for confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: data was obtained from medical records. |

Probably yes

Reason: 30-day follow-up.

|

Probably yes

Reason: patients were matched according to their type of surgery (among other variables). |

High (all outcomes)

|

|

Peng, 2021 |

Definitely no

Reason: Participants were selected from different time periods. |

Probably no

Reason: No transition period was used.

|

Probably yes