ALK fusies

Uitgangsvraag

Welke (nieuwe) behandelingen hebben de voorkeur bij ALK fusies?

Aanbeveling

De algemene aanbevelingen die voor alle zeldzame mutaties gelden staan in de hoofdmodule ‘Behandeling incurabel NSCLC met (zeldzame) mutaties’.

ALK:

Behandel patiënten met een ALK-translocatie met een ALK-TKI in de eerste lijn bij voorkeur met alectinib, brigatinib of lorlatinib.

Behandel patiënten in de tweede lijn en verder afhankelijk van de gegeven TKI in de eerste lijn en het gevonden resistentiepatroon (specifieke ALK-mutatie).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De algemene overwegingen die voor alle zeldzame mutaties gelden staan in de hoofdmodule ‘Behandeling incurabel NSCLC met (zeldzame) mutaties’.

ALK

Eerste lijn: het is al eerder aangetoond dat ORR en PFS significant beter zijn met ALK-TKI (crizotinib danwel ceritinib) dan met platinum-bevattende chemotherapie. De verbetering in mediane PFS is klinisch relevant (HR < 0.7 en verbetering 16 weken of meer). Het percentage graad 3 of hoger bijwerkingen is gelijk tot hoger met ALK-TKIs, het soort bijwerkingen is echter verschillend (met name biochemisch en gastro-intestinaal voor de ALK-TKIs en hematologisch voor de chemotherapie). Echter, ondanks geen evidente verschillen in ernstige bijwerkingen, verbeteren zowel crizotinib als ceritinib de kwaliteit van leven/patiënt gerapporteerde uitkomsten vergeleken met chemotherapie. Totale overleving verbeterde niet in de studies, waarschijnlijk doordat het merendeel van de patiënten in latere lijnen nog met een ALK-TKI werd behandeld. Belangrijk is verder dat patiënten met hersenmetastasen (niet-significante) betere uitkomsten hebben met ALK-TKIs dan met chemotherapie (zowel ORR als PFS).

In de eerstelijnsbehandeling zijn zowel alectinib, brigatinib, lorlatinib als ensartinib (de laatste is niet verkrijgbaar in Nederland) met crizotinib vergeleken bij patiënten met een ALK rearrangement. De verbetering in mediane PFS is klinisch relevant (HR < 0.7 en verbetering 16 weken of meer) en tevens is er door de cerebrale penetratie van de nieuwere TKIs een betere controle van hersenmetastasen, of preventie van het ontstaan van hersenmetastasen. De nieuwere TKIs zijn niet met elkaar vergeleken als eerstelijnsbehandeling, en het is op dit moment niet duidelijk of eerst een tweede generatie ALK-TKI gevolgd door lorlatinib bij progressie, of direct eerste lijn lorlatinib zorgt voor een betere overleving. Op basis van patiënt karakteristieken en het toxiciteitsprofiel kan gekozen worden voor een specifieke nieuwere generatie ALK-TKI in de eerste lijn.

Na progressie op een tweede of derde generatie ALK-TKI kan er, afhankelijk van het resistentiepatroon en de eerder gegeven ALK-TKI, geswitcht worden naar een andere ALK-TKI (te selecteren op basis van de specifieke gevonden ALK-mutatie) danwel (platinum-doublet) chemotherapie, danwel studiedeelname.

Aanbevelingen

De algemene aanbevelingen die voor alle zeldzame mutaties gelden staan in de hoofdmodule ‘Behandeling incurabel NSCLC met (zeldzame) mutaties’.

Onderbouwing

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Overall survival, Adverse events, Quality of Life

|

VERY LOW GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of targeted therapy (ensartinib, brigatinib, lorlatinib, alectinib) versus crizotinib on overall survival, objective response rate, adverse events, and quality of Life in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer stage IIIB/IV and an ALK-fusion.

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of targeted therapy (crizotinib or ceritinib) versus chemotherapy on overall survival, objective response rate, adverse events, and quality of life in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer stage IIIB/IV and an ALK-fusion. |

Objective response rate

|

VERY LOW GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of targeted therapy (ensartinib, brigatinib, lorlatinib, alectinib) versus crizotinib on objective response rate in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer stage IIIB/IV and an ALK-fusion.

Targeted therapy (crizotinib or ceritinib) may increase the objective response rate compared to chemotherapy in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer stage IIIB/IV and an ALK-fusion but the evidence is very uncertain. |

Progression free survival

|

VERY LOW GRADE |

Targeted therapy (ensartinib, brigatinib, lorlatinib, alectinib) may increase progression free survival compared to crizotinib in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer stage IIIB/IV and an ALK-fusion but the evidence is very uncertain.

Targeted therapy (crizotinib or ceritinib) may increase progression free survival compared to chemotherapy in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer stage IIIB/IV and an ALK-fusion but the evidence is very uncertain. |

Samenvatting literatuur

A systematic review that reviewed clinical outcomes after targeted therapy or chemotherapy in NSCLC patients with an ALK fusion was included in this literature analysis.

Description of studies

Peng (2023) performed a systematic review and network meta-analysis of studies to investigate the relative safety and efficacy of all first‐line treatments for patients with ALK‐positive NSCLC. The literature search covered the period 2013–2021. The review included

published/unpublished phase 2/3 randomized clinical trials in patients with histopathologically confirmed advanced (III/IV/recurrent) NSCLC with ALK gene fusions. Articles were included if there was a comparison of any two or more arms of first‐line treatments for patients with advanced NSCLC with ALK gene fusions, and reported on at least one of the following clinical outcome measures: progression‐free survival (PFS), Overall survival (OS), objective response rate (ORR), grade ≥3 treatment‐related adverse events. The following studies were excluded: Trials in which patients with ALK‐positive NSCLC were analyzed as a subgroup, trials of ALK‐TKIs not as first‐line therapy, but as maintenance or neoadjuvant therapy or sequential therapy with chemotherapy or radiotherapy; and trials comparing treatments that have not been approved by any Food and Drug Administration. In total, nine randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included. All trials were industry sponsored or designed in cooperation with the industry. Important study characteristics of the included RCTs are described in table 1. For more details about the included studies, please see Peng (2023).

|

Study (author, year) |

Study design and setting |

Patients |

Intervention |

Control |

Reported outcomes |

Follow-up |

|

Horn, 2021

eXalt3 |

Open-label, multicenter, randomized, phase 3 trial conducted in 120 centers in 21 countries. |

Patients aged ≥18 years and had advanced, recurrent, or metastatic ALK-positive NSCLC. |

Ensartinib 225 mg po qd N=121. |

Crizotinib 250 mg po bid N=126 |

|

Median follow-up: I: 23.8 months (range, 0-44) C: 20.2 months (range, 0-38). |

|

Camidge, 2021 Camidge, 2018

ALTA‐L1 |

A randomized, open-label, phase 3, multicenter, international study. |

Patients aged ≥18 years with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC who had not received ALK-targeted therapy. |

Brigatinib 90 mg po qd for 7 days, then 180 mg po qd N = 137 |

Crizotinib 250 mg po bid N=138 |

|

Median (range) follow-up: I: 40.4 (0–52.4) months C: 15.2 (0.1–51.7) months. |

|

Shaw, 2020

CROWN |

A global, randomized, phase 3 trial. |

Patients age 18 or ≥20 years (according to local regulations) with previously untreated advanced ALK-positive NSCLC. |

Lorlatinib 100 mg po qd N=149 |

Crizotinib 250 mg po bid N=147 |

|

Median follow-up for PFS I: 18.3 months C: 14.8 months

|

|

Mok, 2020 Peters, 2017

ALEX |

Phase III, global, randomized study. |

Patients aged 18 years with previously untreated stage III/IV ALK positive NSCLC. |

Alectinib 600 mg PO bid N = 152 |

Crizotinib 250 mg po bid N=151 |

|

Median duration of survival follow-up for investigator-assessed PFS: I: 37.8 months (range 0.5- 50.7) C: 23.0 months (range 0.3-49.8).

Median duration of survival follow-up for OS I: 48.2 months (range 0.5-62.7) C: 23.3 months (range 0.3-60.6).

|

|

Zhou, 2019

ALESIA |

Randomised, open-label, phase 3 study done at 21 investigational sites in China, South Korea, and Thailand |

Asian patients, aged ≥18 years, with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. |

Alectinib 600 mg po bid N = 125. |

Crizotinib 250 mg po bid N=62 |

|

Median duration of follow-up: I: 16·2 months (IQR 13·7–17·6) C: 15·0 months (12·5–17·3) |

|

Hida, 2017

J‐ALEX |

A multicentre, randomised, open-label phase III trial.

41 study sites in Japan. |

ALK inhibitor-naive Japanese patients with ALK-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer, who were chemotherapy-naive or had received one previous chemotherapy regimen. |

Alectinib 300 mg po bid N=103 |

Crizotinib 250 mg po bid N=104 |

|

Median follow-up in months I: 12·0 (IQR 6·5–15·7) C: 12·2 (8·4–17·4)

The funder decided to immediately release the trial results on the basis of a recommendation from the IDMC. |

|

Wu, 2018

PROFILE1029 |

Open-label phase III study, at 35 centers in China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, the Republic of China, and Thailand. |

East Asian patients with ALK-positive advanced NSCLC. |

Crizotinib 250 mg po bid N=104 |

Pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 + cisplatin 75 mg/m2 OR pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 + carboplatin (AUC 5–6) N=103 |

|

Median follow-up for OS: I: 22.5 months (95% CI: 20.5–23.3) C: 21.6 months (95% CI: 20.7–23.0). |

|

Solomon, 2018 Solomon, 2014

PROFILE1014 |

A randomized, open-label, phase 3 study. |

Patients with locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC positive for an ALK rearrangement with no previous systemic treatment of advanced disease. |

Crizotinib 250 mg po bid N=172 |

Pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 + cisplatin 75 mg/m2 OR pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 + carboplatin (AUC 5–6) |

|

At final OS analysis, follow-up for OS I: 45.7 months (95% CI, 42.7 to 48.8 months) C: 45.5 months (95% CI, 43.4 to 49.1 months). |

|

Soria, 2017

ASCEND‐4 |

A randomised, open-label, global, phase 3 study, in 134 sites across 28 countries. |

Patients (aged ≥18 years) with stage IIIB/IV ALK-rearranged nonsquamous NSCLC. |

Ceritinib 750 mg po qd N=189 |

Pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 + cisplatin 75 mg/m2 OR pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 + carboplatin (AUC 5–6) followed by maintenance pemetrexed N=187 |

• PFS • OS • Overall response • AEs

|

Median duration between randomisation and PFS analysis for all patients was 19∙7 months. |

Study results

Overall survival - Critical outcome

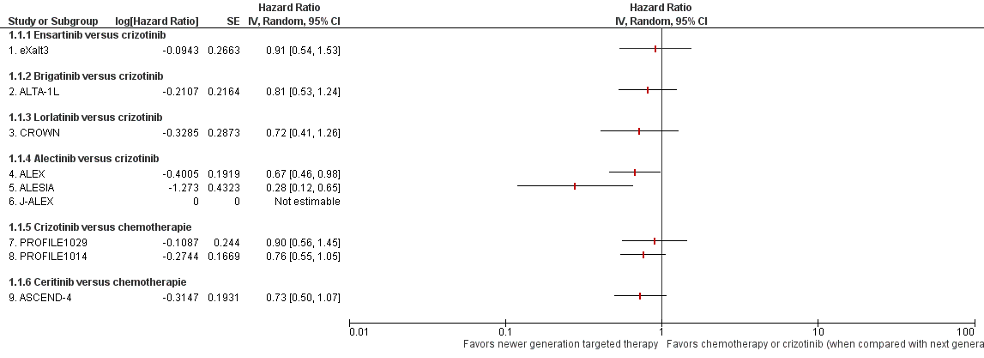

Nine of the nine studies included in the systematic review by Peng (2023) reported on overall survival (Figure 1).

In the eXalt3 study, data about the effect of ensartinib versus crizotinib on overall survival remained immature at data cutoff. In the modified intention to treat (mITT) population, 62 patients died (24.8% in the ensartinib group and 25.4% in the crizotinib group; HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.54-1.54). This difference was not considered clinically relevant. The 2-year overall survival rate was 78% in both groups. Median interim OS was not reached in either group.

In the ALTA-1L study, data about the effect of brigatinib versus crizotinib on overall survival remained immature at data cutoff. At the end of the study, 92 patients had died (30% in the brigatinib arm and 37% in the crizotinib arm). The 3-year estimated OS rate was 71% (95% CI: 62%–78%) in the brigatinib arm and 68% (95% CI: 59%–75%) in the crizotinib arm without adjustment for patients who crossed over from crizotinib to brigatinib (HR = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.53–1.22, log-rank p = 0.33). This difference was not considered clinically relevant.

In the CROWN study, data about the effect of lorlatinib versus crizotinib on overall survival remained immature at data cutoff. At data cutoff 51 patients died (15% in the lorlatinib

group and 19% in the crizotinib group).

Three studies (ALEX, ALESIA, J-ALEX) reported the effect of alectinib versus crizotinib on overall survival. In the ALEX study, OS data remained immature with 37% of events recorded (stratified HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.46-0.98). At data cutoff, 113 patients died (33.6% in the alectinib group versus 41.1% in the crizotinib group). Median OS was not reached in the alectinib arm and was 57.4 months in the crizotinib arm (95% CI 34.6-NR). The 5-year OS rate was 62.5% (95% CI 54.3-70.8) with alectinib and 45.5% (95% CI 33.6- 57.4) with crizotinib. In the ALESIA study, OS data remained immature, with 8 deaths (6%) reported in the alectinib group and 13 deaths (21%) reported in the crizotinib group. In the J-ALEX study, OS data remain immature, with only nine events reported (2% in the crizotinib group and 7% in the alectinib group).

Two studies (PROFILE1029 and PROFILE1014) reported the effect of crizotinib versus chemotherapy on overall survival. In the PROFILE1029 study, 72 patients died 35 (33.7%) in the crizotinib arm and 37 (35.9%) in the chemotherapy arm). Median OS was 28.5 months (95% CI: 26.4–not reached) with crizotinib and 27.7 months (95% CI: 23.9–not reached) with chemotherapy. In the PROFILE1014 study, median OS was not reached (NR; 95% CI, 45.8 months to NR) for the crizotinib group and was 47.5 months (95% CI, 32.2 months to NR) for the chemotherapy group.

In the ASCEND-4 study, data about the effect of ceritinib versus chemotherapy on overall survival remained immature at data cutoff. At data cutoff, 48 events occurred in the

ceritinib group and 59 events in the chemotherapy group, representing 42% of the required events for final OS analysis. The median overall survival was not reached in the ceritinib group (95% CI 29∙3 to not estimable) and was 26∙2 months (22∙8 to not estimable)

in the chemotherapy group (HR 0∙73 [95% CI 0∙50–1∙08]; p=0∙056). This difference was not considered clinically relevant. The 2-year estimated OS rates were 70∙6% (95% CI 62.2–77.5) in the ceritinib group and 58.2% (47.6–67.5) in the chemotherapy group.

Figure 1. Forest plot Overall survival newer generation targeted therapy versus chemotherapy or crizotinib (when compared with next generation TKI)

Progression free survival (PFS) - Important outcome

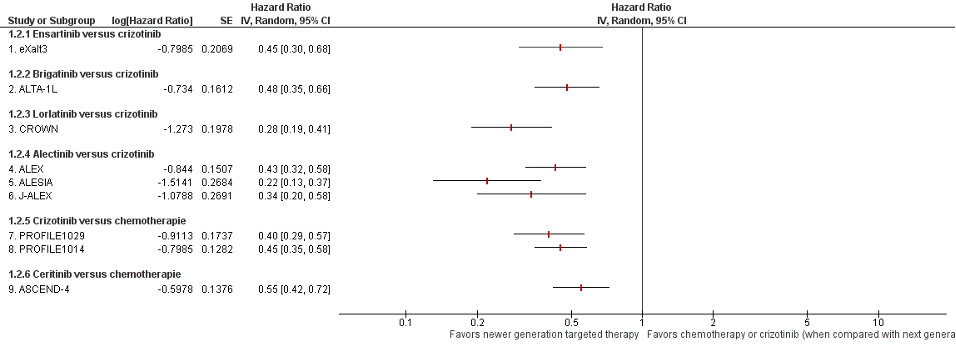

Nine of the nine studies included in the systematic review by Peng (2023) reported on progression free survival (Figure 2).

In the eXalt3 study, 119 PFS events occurred in the mITT population (62.6% of the 190 expected PFS events). The median PFS was not reached in the ensartinib group (95% CI, 20.2 months to not reached) and 12.7 months in the crizotinib group (95 CI%: 8.9-16.6; HR: 0.45 95%CI: 0.30-0.66; log-rank P < .001). This difference was considered clinically relevant.

In the ALTA-1L study, 166 PFS events occurred, of which 73 in the brigatinib arm (53%) and 93 in the crizotinib arm (67%). The estimated 3-year PFS was 43% (95% CI: 34%–51%) in the brigatinib arm and 19% (95% CI: 12%–27%) in the crizotinib arm (HR = 0.48, 95% CI: 0.35–0.66). This difference was considered clinically relevant. Blinded independent review showed a 4-year PFS 36% (26%–46%) in the brigatinib arm and 18% (11%–26%) in the crizotinib arm. However, this result was limited by a high rate of censoring and few patients at risk in each group.

In the CROWN study, 127 PFS events occurred at data cutoff, of which 41 in the lorlatinib group (28%) and 86 in the crizotinib group (59%). The 12-month PFS was 78% (95% CI: 70–84) in the lorlatinib group and 39% (95% CI: 30–48) in the crizotinib group. HR for disease progression or death= 0.28 (95% CI, 0.19–0.41). This difference was considered clinically relevant

Three studies (ALEX, ALESIA, J-ALEX) reported the effect of alectinib versus crizotinib on PFS. In the ALEX study, 203 patients experienced a PFS event, of which 81 (53.3%) in the alectinib group and 122 (80.8%) in the crizotinib group. Median PFS was 34.8 months (95% CI: 17.7- not evaluable) in the alectinib group and 10.9 months (95% CI: 9.1-12.9) in the crizotinib group. In the ALESIA study, investigator assessed PFS showed that 63 PFS events occurred, of which 26 (21%) in the alectinib group and 37 (60%) in the crizotinib group. Median PFS was not evaluable (95% CI 20·3–NE) for the alectinib group and 11·1 months (95%CI: 9·1–13·0) for the crizotinib group. In the J-ALEX study, 83 PFS events occurred at the second preplanned interim analysis (25 in the alectinib group and 58 in the crizotinib group). Median PFS was not evaluable (95% CI 20·3–NE) in the alectinib group versus 10·2 months (8·2–12·0) with crizotinib (HR 0·34 [99·7% CI 0·17–0·71). The funder decided to release the results immediately, as advised by the independent data monitoring committee. The pooled results of the three RCTS concerning alectinib versus crizotinib showed a hazard ratio of 0.33 (95% CI: 0.22 to 0.49) for PFS favoring alectinib. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

Two studies (PROFILE1029 and PROFILE1014) reported the effect of crizotinib versus chemotherapy on PFS. In the PROFILE1029 study, 166 patients experienced a PFS event (77 in the crizotinib arm and 89 treated with chemotherapy). Median PFS was 11.1 months (95% CI: 8.3–12.6) in the crizotinib group and 6.8 months (95% CI: 5.7–7.0) in the chemotherapy group. In the PROFILE1014 study, median PFS was 10.9 months (95% CI: 8.3 to 13.9) in the crizotinib group and 7.0 months (95% CI: 6.8 to 8.2) in the chemotherapy group. The pooled results of the two RCTS concerning crizotinib verus chemotherapy showed a hazard ratio of 0.43 (95% CI: 0.35 to 0.53) for PFS favoring crizotinib. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

In the ASCEND-4 study, median PFS as assessed by the blinded independent review committee was 16∙6 months (95% CI: 12∙6–27∙2) in the ceritinib group versus 8∙1 months

(5∙8–11∙1) in the chemotherapy group (HR 0.55; 95% CI: 0.42–0.73). This difference was considered clinically relevant.

Figure 2. Forest plot Progression free survival of newer generation targeted therapy versus chemotherapy or crizotinib (when compared with next generation TKI)

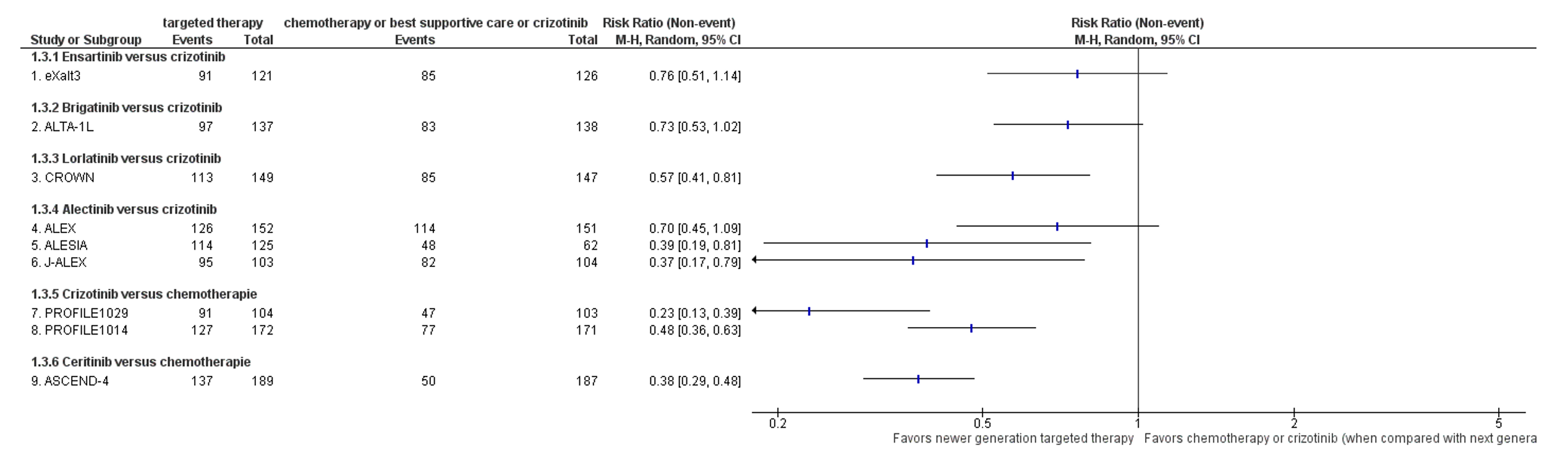

Objective response rate (ORR) - Important outcome

Nine of the nine studies included in the systematic review by Peng (2023) reported on ORR (Figure 3). The HR for ORR in patients treated with ensartinib, brigatinib, and alectinib compared to patients treated with crizotinib was 1.11 (95% CI: 0.95 to 1.31), 1.18 (95% CI: 0.99 to 1.40), and 1.14 (95% CI: 1.07 to 1.23) respectively. These differences were not considered clinically relevant. The ORR was higher in patients treated with lorlatinib compared to patients treated with crizotinib (HR 1.31; 95% CI: 1.11 to 1.55). This differences was considered clinically relevant. The ORR was higher in patients treated with crizotinib (pooled HR 1.75 ; 95% CI: 1.51 to 2.04) or ceritinib (HR 2.71; 95% CI: 2.11 to 3.49) compared to patients treated with chemotherapy. These differences were considered clinically relevant.

Figure 3. Forest plot objective response rate of newer generation targeted therapy versus chemotherapy or crizotinib (when compared with next generation TKI)

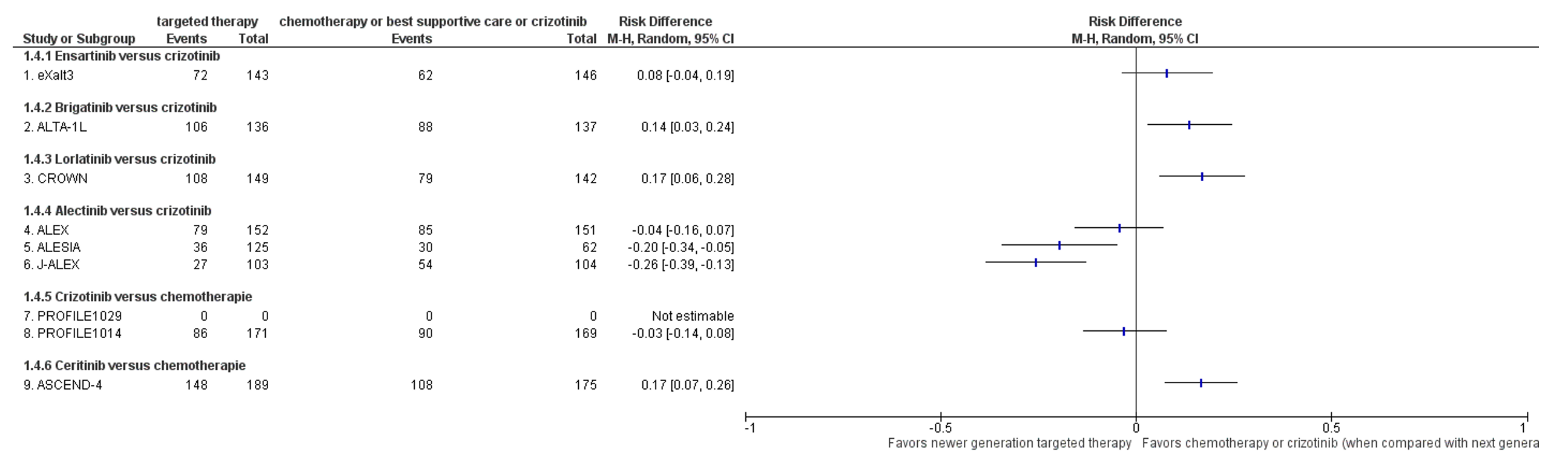

Adverse events (AEs) Grade ≥3 - Important outcome

Nine of the nine studies included in the systematic review by Peng (2023) reported on adverse events grade ≥3. Most studies reported a high number of patients with adverse events grade ≥3.

The Risk difference for AEs grade ≥3 in patients treated with ensartinib, brigatinib, and lorlatinib compared to patients treated with crizotinib was 0.08 (-0.04, 0.19), 0.14 (0.03, 0.24), and 0.17 (0.06, 0.28) respectively. These differences were not considered clinically relevant.

Combining the data from the three RCTs (ALEX, ALESIA, J-ALEX), the occurrence of grade≥ 3 adverse events was 142 in 380 patients treated with alectinib (37%) and 169 events in 317 patients treated with crizotinib (53%). The pooled risk difference was -0.16 (95% CI: -0.30 to -0.03). This difference was not considered clinically relevant.

The Risk difference for AEs grade ≥3 in patients treated with crizotinib compared to patients treated with chemotherapy was -0.03 (-0.14, 0.08). The Risk difference for AEs grade ≥3 in patients treated with ceritinib compared to patients treated with chemotherapy was 0.17 (0.07, 0.26). These differences were not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 4 Forest plot of newer generation targeted therapy versus chemotherapy or crizotinib (when compared with next generation TKI) outcome safety, defined as number of grade ≥3 adverse events

Quality of life (QoL) - Important outcome

Five of the nine studies included in the systematic review by Peng (2023) reported on quality of life (QoL).

In the ALTA-1L study, median time to worsening of GHS/QoL was 26.7 months in the brigatinib arm versus 8.3 months in the crizotinib arm (HR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.49–0.98). The authors also reported that the time to worsening of emotional and social functioning and symptoms of fatigue, nausea and vomiting, appetite loss, and constipation was significantly delayed by brigatinib.

In the CROWN study, mean baseline scores of global quality of life were 64.6 (SE 1.82) in the lorlatinib group and 59.8 (SE 1.90) in the crizotinib group. A significantly greater overall improvement was observed among patients in the lorlatinib group compared to patients in the crizotinib group (estimated mean difference, 4.65; 95% CI: 1.14 to 8.16). The authors state that this difference was not considered clinically meaningful.

In the PROFILE1029 study, significantly greater improvement in global QoL scores from baseline was observed in patients in the crizotinib group compared to patients in the chemotherapy group(p < 0.001). Statistically significantly greater improvements were also observed with regard to physical functioning, role functioning, social functioning, and cognitive functioning (assessed by the QLQC30) and in general health status scores (assessed by the EQ-5D-3L visual analog scale). In patients treated with crizotinib significantly greater reductions from baseline were observed compared to patients in the chemotherapy group for symptoms of fatigue, pain, insomnia, appetite loss, alopecia, pain in the arm/shoulder, pain in other body parts, coughing, dyspnea, and pain in the chest. Differences in mean changes in overall quality of life score were not reported.

In the PROFILE1014 study, Solomon (2014) suggested a greater reduction from baseline in the symptoms of pain, dyspnea, and insomnia (assessed by the QLQ-C30) and in the symptoms of dyspnea, cough, chest pain, arm or shoulder pain, and pain in other parts of the body as assessed with the use of the QLQ-LC13 with crizotinib than with chemotherapy. The results, however, were only plotted in a figure. The authors reported that significantly greater improvement in global QoL scores from baseline was observed in patients in the crizotinib group compared to patients in the chemotherapy group(p < 0.001). Statistically significantly greater improvements were also observed with regard to physical functioning, social, emotional and role functioning domains. Differences in mean changes in overall quality of life score were not reported.

In the Ascend-4 study, lung cancer-specific symptoms and quality of life measures with the EuroQol (EQ-5D-5L) were significantly improved for ceritinib versus chemotherapy. No mean quality of life scores per treatment group were reported; results were only plotted in a figure.

In the eXalt3 study, the ALEX study, and the ALESIA study, and the J-ALEX study QoL outcomes were not reported.

Level of evidence

We did not assess the certainty of the evidence for each outcome separately based on the individual studies by using GRADE, but described the main limitations of the systematic reviews or the studies included in the systematic reviews to provide an indication of the overall certainty of the evidence. The risk of bias assessment for the individual included studies was adopted from the systematic review by Peng (2023).

There are four levels of evidence: high, moderate, low, and very low. RCTs start at a high level of evidence.

Targeted therapy (ensartinib, brigatinib, lorlatinib, or alectinib) versus crizotinib

The levels of evidence for OS, PFS, ORR, AEs, and QoL were downgraded with three levels because of limitations in the study design (risk of bias: no blinding of patients and physicians and unclear whether outcome data was complete and unclear if the study was free of other bias), inconsistency of results (heterogeneity), imprecision (OIS not reached).

Crizotinib or ceritinib versus chemotherapy:

The levels of evidence for OS, PFS, ORR, AEs, and QoL were downgraded with three levels because of limitations in the study design (risk of bias: no blinding of patients and physicians and limited information on concealment of allocation), inconsistency of results (heterogeneity), and imprecision (OIS not reached).

Zoeken en selecteren

The search and selection methods can be found in the main module ‘Behandeling incurabel NSCLC met (zeldzame) mutaties’.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 01-01-2023

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodules werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodules.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met niet kleincellig longcarcinoom. Deze werkgroep is ingesteld in het kader van het cluster longoncologie.

Werkgroep

• dr. A. (Annemarie) Becker (voorzitter), Longarts, Amsterdam UMC, NVALT

• dr. A.J. (Anthonie) van der Wekken, Longarts, UMCG, NVALT

• dr. A. (Annemarieke) Bartels – Rutten, Radioloog, AVL, NVvR

• prof. dr. V. (Volkher) Scharnhorst, Klinisch chemicus, Catharina Ziekenhuis, NVKC

• prof. dr. E.F.I. (Emile) Comans, Nucleaire geneeskundige, Amsterdam UMC, NVNG

• prof. dr. J.J.C. (Joost) Verhoeff, Radiotherapeut-Oncoloog, Amsterdam UMC, NVRO

• prof. dr. J. (Jerry) Braun, Hoogleraar Cardio-thoracale chirurgie, LUMC, NVT

• dr. K.J. (Koen) Hartemink, Chirurg, AVL, NVvH

• dr. R.A.M. (Ronald) Damhuis, Arts-onderzoeker, IKNL

• drs. L.A. (Lidia) Barberio, Directeur Longkanker Nederland

• dr. B.J.M. (Bas) Peters, Ziekenhuisapotheker, St. Antonius Ziekenhuis, NVZA

• dr. R. (Rob) ter Heine, Ziekenhuisapotheker- klinisch farmacoloog, Radboudumc, NVZA

• drs. D.C.M. (Desirée) Verheijen, Klinisch geriater, ZGV, NVKG

• dr. J.H. (Jan) von der Thüsen, Patholoog, Erasmus MC, NVVP

• dr. W. (Wouter) van Geffen, Longarts, MCL, NVALT

• dr. L.E.L. (Lizza) Hendriks, Longarts, MUMC+, NVALT

• dr. A. (Arifa) Moons-Pasic, Longarts, OLVG, NVALT

• dr. I. (Idris) Bahce, Longarts, Amsterdam UMC, NVALT

• prof. dr. E. (Ed) Schuuring, Hoogleraar in de Moleculaire Oncologische Pathologie, UMCG, NVVP

• dr. J.M.J. (Josephine) Stoffels, Internist Ouderengeneeskunde, NIV

• dr. J.W. (Joost) van den Berg, Internist Ouderengeneeskunde i.o., NIV

In het kader van het cluster longoncologie

Met ondersteuning van

• dr. J.S. (Julitta) Boschman, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (tot december 2023)

• M.L. (Miriam) te Lintel Hekkert, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

• dr. L.C. (Lisanne) Verbruggen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

• dr. D. (Dagmar) Nieboer, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

• A. (Alies) Oost, medisch informatiespecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de volgende clustercyclus.

De NVALT heeft vastgesteld dat het niet mogelijk was werkgroepleden af te vaardigen met voldoende expertise zonder potentiële belangenverstrengeling. Het gaat daarbij met name om werkgroepleden die deelnemen aan adviesraden/kennisuitwisselingsbijeenkomsten met de farmaceutische industrie. Gedurende de ontwikkeling van de modules heeft daarom afstemming plaatsgevonden tussen de werkgroepvoorzitter, de belangencommissie van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en de NVALT over passende acties naar aanleiding van de gemelde belangen.

Restricties voor de modules over onderwerpen (medicamenteuze behandeling) waar de adviesraden betrekking op hebben:

• Werkgroeplid werkt niet als enige inhoudsdeskundige aan de module;

• Werkgroeplid werkt tenminste samen met een werkgroeplid met een vergelijkbare expertise in alle fasen (zoeken, studieselectie, data-extractie, evidence synthese, Evidence-to-decision, aanbevelingen formuleren) van het ontwikkelproces. Indien nodig worden werkgroepleden toegevoegd aan de werkgroep;

• In alle fasen van het ontwikkelproces is een onafhankelijk methodoloog betrokken;

• Overwegingen en aanbevelingen worden besproken en vastgesteld tijdens een werkgroepvergadering onder leiding van een onafhankelijk voorzitter (zonder gemelde belangen).

Aansluitend op de reguliere commentaarronde bij de achterban van de bij de richtlijn betrokken wetenschappelijke verenigingen, hebben (een aantal) leden van de richtlijn- en kwaliteitscommissie van de NVALT en een methodoloog van het Kennisinstituut die niet betrokken waren bij ontwikkeling van de modules, aanvullend beoordeeld of de aanbevelingen logischerwijs aansluiten bij het gevonden bewijs en de overwegingen, om de onafhankelijkheid van de richtlijn te waarborgen.

Wellicht ten overvloede willen wij erop wijzen dat medisch specialistische richtlijnen niet worden vastgesteld door de betreffende richtlijnwerkgroep maar door de besturen/ledenvergadering van de betrokken verenigingen.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Becker |

Longarts Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: SYMPRO studie Project over beeldvorming in de follow-up na behandeling voor longkanker gaat nog starten (gefinancierd door ZIN) |

geen |

|

Bartels-Rutten |

Radioloog, NKI-AVL (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

geen |

|

van der Wekken |

UMCG - longarts |

Geen |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: Lid bestuur Sectie oncologie NVALT Lid dure geneesmiddelen commissie NVALT Lid Cie Geneesmiddelen FMS Specialisten panel Longkanker Nederland Consortium partner 3D modeling in MTB Adviesraden voor UMCG bij Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Roche, Janssen |

restricties |

|

Comans |

Nucleair geneeskundige HMC Den Haag (0.6 FTE) |

Hoogleraar nucleaire geneeskunde Amsterdam UMC lokatie VUmc (0.4 FTE). |

Geen |

geen |

|

Braun |

Hoogleraar Cardio-thoracale Chirurgie, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum en Amsterdams Universitair Medisch Centrum. |

Lid bestuur Nederlandse Vereniging voor Thoraxchirurgie (onbetaald). |

Geen |

geen |

|

Verhoeff |

Radiation oncologist and professor of radiotherapy at the Amsterdam UMC |

Niet van toepassing |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: 1. STOPSTORM H2020, bestraling van hartritmestoornissen |

geen |

|

Hartemink |

Chirurg NKI-AVL, Amsterdam |

Onbetaald: |

KWF-grant ontvangen (2021) voor het doen van onderzoek naar radiotherapie en chirurgie bij het vroeg-stadium NSCLC. |

geen |

|

Scharnhorst |

Klinisch chemicus, Catharina Ziekenhuis Eindhoven |

Deeltijdhoogleraar klinische chemie TU/e |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: |

geen |

|

Moons -Pasic |

Longarts OLVG Amsterdam |

Niet van toepassing |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: |

geen |

|

Peters |

Ziekenhuisapotheker |

Niet van toepassing |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: * Abbvie - Systematic evaluation of the efficacy-effectiveness gap of systemic treatmens in extensive disease - Geen projectleider |

geen |

|

Verheijen |

Klinisch geriater, voor 0,8 fte. |

Geen |

Geen |

geen |

|

Schuuring |

Senior staflid en lid van MT (Management Team) van de afdeling Pathologie van het Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen. |

Adviseur/KMBP voor Moleculaire Pathologie voor de Stichting Pathologie Friesland in Leeuwarden, voor Martini Ziekenhuis te Groningen, voor Treant Zorggroep Bethesda ziekenhuis in Hoogeveen en voor ADCNV to Curacao (allen onbetaald) |

Adviseur/consultant m.b.t. (moleculaire) diagnostiek voor firma's (2019-2023): MSD/Merck, AstraZeneca, Astellas Pharma, Roche, Novartis, Bayer, BMS, Lilly, Amgen, Illumina, Agena Bioscience, Janssen Cilag (Johnson&Johnson), GSK, Diaceutics, CC Diagnostics (honoraria op UMCG rekening) Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: In UMCG-team heb ik financiele ondersteuning voor onderzoek ontvangen van: |

restricties |

|

Bahce |

Commissielid |

Geen |

Geen dienstverband, eigendom, patent of anderszins Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: Diverse investigator-initiated onderzoeken op de longafdeling van het Amsterdam worden gefinancierd door de bedrijven Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca en BMS |

restricties |

|

von der Thüsen |

Patholoog |

Geen |

Honoraria en consulting fees van: Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: |

restricties |

|

Barberio |

Directeur patiëntenorganisatie Longkanker Nederland (betaald) |

lid RvT Stichting Agora, leven tot het einde (betaald) |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: |

geen |

|

Hendriks |

Longarts |

mede-auteur geweest van ESMO richtlijn SCLC |

Betaling voor webinars Benecke, MedTalks, VJOncology Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: chair metastatic NSCLC systemic therapy EORTC secretaris stichting NVALT studies adviesraden (betaald aan instituut niet aan mij): Amgen, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and Takeda betaling voor educational webinars (betaald aan instituut niet aan mij) Janssen, podcasts Takeda, invited speaker AstraZeneca, Bayer, high5oncology, Lilly en Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), interview sessies Roche betaling aan instituut voor lokale PI farma studies van AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Blueprint Medicines, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Merck Serono, Mirati, MSD, Novartis, Roche en Takeda |

restricties |

|

ter Heine |

Ziekenhuisapotheker-klinisch farmacoloog, Radboudumc |

Geen |

Ik heb een onkostenvergoeding ontvangen voor het geven van een scholing over de klinische farmacologie van sotorasib, een nieuw middel in de behandeling van longkanker, van de firma AMGEN. Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: |

geen |

|

Damhuis |

Onderzoeker IKNL (betaald) |

Lid wetenschappelijke commissie DLCA-S (onbetaald) |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: |

geen |

|

van Geffen |

Medisch Centrum Leeuwarden |

NVALT bestuur |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: * Projectleider |

restricties |

|

Stoffels |

Internist ouderengeneeskunde Amsterdam UMC |

freelance nieuwsschrijver Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde

|

Amsterdam UMC innovatiefonds |

geen |

|

van den Berg |

Arts assistent Inwendige Geneeskunde Amsterdam UMC |

Betaalde nevenfunctie: * Post-doctoraal onderzoek Professional Performance and Compassionate Care-onderzoeksgroep AmsterdamUMC (niet extern gefinancierd) |

Geen |

geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Longkanker Nederland heeft bijgedragen aan de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie voor het cluster Longoncologie. Daarnaast werd er aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door de afvaardiging van Longkanker Nederland in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptmodule werden tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd bij Longkanker Nederland (in afstemming met de Nederlandse Federatie van Kankerpatiëntenorganisaties).

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse werden verschillende partijen uitgenodigd om input te geven op een concept-raamwerk voor de richtlijnen niet kleincellig longcarcinoom en kleincellig longcarcinoom. Deze richtlijnen zijn dermate verouderd, dat een grotere herziening noodzakelijk is om uiteindelijk goed mee te kunnen draaien in het modulair onderhoud zoals in de Koploperprojecten wordt beoogd.

Het doel van deze stakeholderraadpleging was om te inventariseren welke knelpunten men ervaart rondom de te herziene richtlijnen. De benoemde knelpunten werden vervolgens door de richtlijnwerkgroep geprioriteerd en vertaald in uitgangsvragen.

De volgende vijf modules kregen prioriteit bij het uitvoeren van onderhoud aan de richtlijn Niet kleincellig longcarcinoom:

- (Neo)adjuvante immuuntherapie

- Dubbele immuuntherapie

- Behandeling na (chemo-)immuuntherapie

- Eerstelijnsbehandeling incurabel NSCLC met EGFR exon 19/21 mutatie

- Behandeling incurabel NSCLC met (zeldzame) mutaties

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model (Review Manager 5.4). De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule wordt aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren worden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren wordt de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule wordt aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.