Autoantibody testing in myositis

Uitgangsvraag

What is the role of antibody testing in diagnosing idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM)?

Wat is de plaats van het testen op antilichamen bij het diagnosticeren van idiopathische inflammatoire myopathie (IIM)?

Aanbeveling

Aanbeveling JDM:

Bepaal myositis auto-antistoffen inclusief anti-HMGCR in kinderen als de diagnose JDM wordt overwogen.

Aanbeveling IBM:

Overweeg het bepalen van anti-cN1A bij patiënten met verdenking op IBM als er geen spierbiopt wordt genomen of als het spierbiopt geen duidelijk resultaat geeft. Een positief testresultaat ondersteunt de klinische diagnose. Een negatief testresultaat sluit de diagnose IBM niet uit.

Aanbeveling IIM (exclusief JDM en IBM):

Test voor myositis auto-antistoffen (inclusief anti HMGCR) wanneer de diagnose IIM overwogen wordt.

Myositis specifieke en myositis geassocieerde antistoffen kunnen de diagnose ondersteunen, informeren over specifieke ziektekarakteristieken en prognose, richting geven aan verder aanvullend onderzoek, en de behandeling op maat laten aanpassen. Interpretatie van resultaten van de immunoblot dient gedaan te worden in de context van de ziektepresentatie.

Er is vooralsnog geen plaats voor routinematige vervolging van titers.

Overwegingen

Considerations – from evidence to recommendation

Pros and cons of the intervention and the quality of the evidence

Myositis-specific antibody testing has become routine practice in recent years in JDM, IBM and in IIM. In this module, its use for making the diagnosis is evaluated. In case of high accuracy, MSA testing could make other, more invasive, expensive and time- consuming ancillary investigations, such as imaging and pathology, redundant. However, in order to be clinically meaningful, MSA testing qualities should be investigated using well-defined control patients that are relevant in clinical practice. Id est, a diagnostic test should be able to differentiate (subtypes of) IIM from clinically similar conditions. For instance, a diagnostic test for IIM (excluding IBM) and JDM should differentiate these disorders from the absence of disease, rheumatic diseases and muscular dystrophies. A diagnostic test for IBM should differentiate this disease from motor neuron disease. In case of conditions not readily confused clinically with IBM, such as SLE and Sjögren’s syndrome, the specificity of the test – such as anti-cN1A testing, which has been shown to be often positive in these patients – is of lesser importance.

With a high pre-test probability for IIM, for instance when all clinical signs of dermatomyositis are present, the finding of an MSA will not have much additional value in establishing the diagnosis dermatomyositis. On the other side, if a patient has a very low pre-test probability, the presence of an MSA will also be of lesser diagnostic value, since the test can be false positive. Requesting of MSA analysis is in these cases discouraged. The dialogue between diagnostic laboratory and clinicians in the interpretation of the results should not be underestimated. With the possibility of false positive and false negative results, antibody testing should only be performed in centres with experience in diagnosing IIM. Screening in patients with vague symptoms and complaints results in limited information for the diagnosis. The value of sequential MSA-testing is unknown.

With the newly developed myositis line immunoassay (LIA), antibodies against anti-HMGCR and anti-cN1A can be tested in addition to the previous mentioned MSA and MAA which have been researched in included studies. This lineblot can be used as a diagnostic test when suspecting an inflammatory myopathy in adults.

When suspecting IBM, anti-cN1A antibody presence can be determined using either an ELISA test or the LIA.

Values and preferences of patients

Testing of myositis specific and associated antibodies is relatively easy and of limited additional burden to patients, as these can be determined from blood samples. Testing could help in making the right diagnosis early and thereby enable early aggressive treatment to prevent irreversible damage. In specific situations, a positive test could make a muscle biopsy unnecessary for diagnosis. More studies should be performed on the value of antibody testing to monitor treatment effect and the value of sequential testing.

Costs

Using line immunoassay, the presence of MSA or MAA can be detected in a quick fashion (usually within a week) and is less expensive compared to traditional methods, such as individual ELISA testing or immunoblotting and protein immunoprecipitation. The test is offered in several centers in The Netherlands. Since many clinicians already use the lineblot, a significant increase in testing volume (and therefore costs) is not expected.

Acceptability, feasibility and implementation

MSA testing is part of routine practice in (expert neurological) medical centers, and no large barriers with regard to its applicability, acceptability or feasibility are foreseen.

Recommendations

- Recommendations JDM

In JDM, no studies meeting our criteria could be identified. However, the prevalence of myositis-specific antibodies (by immunoprecipitation and ELISA) has been investigated in large cohorts of patients with juvenile inflammatory myositis (JIM) – the majority of which had juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) – compared to patients with juvenile inflammatory arthritis (JIA), juvenile Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (JSLE), muscular dystrophy and healthy controls. MSA-positivity was found in just over half the patients with JDM, and also in patients with other forms of juvenile myositis, but not in any of the other patient groups (Tansley, 2017). Of note, this prevalence was also found in children with very mild disease.

- Recommendations IBM

As described in the literature analysis above, anti-cN1A antibodies have fairly consistently been reported to show low sensitivity but sufficient specificity for the diagnosis IBM. If there is a high a priori probability of IBM, a positive test result may be considered sufficient to make the diagnosis in patients in whom a muscle biopsy is relatively contraindicated (e.g., abundant fatty replacement of muscle tissue on MRI, or increased risk of bleeding complications). However, the evidence from these studies is graded as very low for various reasons, see above. Furthermore, inadequate patient-control groups were investigated: DM and other non-IBM IIMs, and rheumatic diseases that are not readily confused with IBM clinically. Only the study by Herbert (2016) included a large group of various other genetic and acquired neuromuscular diseases.

- Recommendations IIM

The presence of myositis specific and myositis associated antibodies when suspecting an IIM can help facilitate diagnosis. A negative line immunoassay, however, does not exclude the diagnosis of IIM. Line immunoassay is a quick and easy method with fair false positive and negative ratios. Anti-HMCGR antibody ELISA should be performed if the antibody is not already part of the line immunoassay. In an IIM-overlap syndrome, onse should consider combining the assessment of MSA/MAA with a HEp-2 IFA After diagnosis, presence of certain antibodies can determine subgroups characteristics, malignancy association, and prognosis (see modules Cancer screening in myositis, Screening for pulmonary and cardiac IIM involvement, and Immunosuppression and immunomodulation for further information). Treatment can be optimized and tailor-made. The diagnostic value of the line immunoassay when the result is weak-positive, is very limited, and interpretation should be made with caution. The value of sequential testing is unknown.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM), or myositis, encompass a heterogenous group of rare autoimmune diseases characterized by muscle weakness and inflammation. To diagnose IIM, a muscle biopsy – a relatively invasive procedure – is considered the gold standard for most types. Recent literature suggests that certain myositis specific antibodies are associated with subtypes of IIM, and with comorbidities such as interstitial lung disease and cancer. Determining myositis specific and associated antibodies can be helpful in the diagnostic and treatment phase.

Anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) by indirect immunofluorescent assays (IFA) with HEp-2 cells

as substrate has very limited added value in the diagnostic work-up of IIM and MSA are only poorly detected by HEp-2 IFA. Clinical suspicion of IIM is best to be followed directly by testing for MSA panels (Damoiseaux, 2022). The Hep-2 IFA is therefore not included in the literature search.

For this guideline module, IIMs are categorized into three groups: (a) juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM); (b) inclusion body myositis (IBM); and (c) other subtypes of adult idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (excluding IBM). The aim was to assess the test accuracy of myositis-specific antibodies (MSA) in diagnosing JDM, IBM and other subtypes of IIMs.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Juvenile dermatomyositis

|

No GRADE |

No conclusions can be drawn on the diagnostic test accuracy of antibody testing in JDM patients. |

2. Inclusion body myositis

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is uncertain about the diagnostic value of anti-cN1A antibody testing in differentiating the presence of inclusion body myositis from other inflammatory myopathies, autoimmune disorders, other neuromuscular diseases, or healthy individuals.

Source: Mavroudis 2021; Lucchini 2021 |

3. IIM

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that myositis specific antibody testing has a relatively low sensitivity in patients suspected of having a idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. The specificity seems reasonable.

Source: Beaton 2021, Lecouffe-Desprets 2018, Montagnese 2019, Platteel 2019, To 2020 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

1. Juvenile dermatomyositis

No literature matching our selection criteria was found on the subject of MSA in JDM.

2. Inclusion body myositis

Two articles (one systematic review and one case-control study) were included.

Mavroudis (2021) performed a systematic review to study the diagnostic accuracy of anti-cN1A antibodies for sporadic IBM in comparison with other inflammatory myopathies, autoimmune disorders and motor neuron disease. Seven case-control studies with a cumulative 599 IBM patients and 1676 controls (with polymyositis, dermatomyositis, other neuromuscular disorders and other autoimmune conditions including systemic lupus erythematous, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis) were included in the review. Various methods of detecting anti-cN1A antibodies were used in the different case-control studies, and standard reference testing through muscle biopsy was not performed in all patients and controls. Specific characteristics of included patients, such as age and gender, were not described.

Lucchini (2021) assessed the sensitivity and specificity of anti-cN1A antibodies in sporadic IBM patients compared to controls, to find a potential correlation with clinical disease severity. In this case-control study, 62 consecutive patients with sporadic IBM and 62 patients with other inflammatory myopathies were included, yet patients treated with intravenous immunoglobulins, or with immunosuppressant use in the past 6 months (> 5 mg prednisolone) were excluded. Mean age in the IBM group was 67.3 years (SD 9.6), of whom 63% were men, and in the control group 63.6 years (SD 14.0) with 39% men. The control group consisted of patients with immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM, n = 28), dermatomyositis (DM, n =20), polymyositis (PM, n = 10), and overlap myositis (OM, n = 4). Creatine Kinase (CK) baseline levels for the controls, and clinical severity of disease were not reported. Sera from all included participants were tested for anti-cN1A antibodies using Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA). Patients with sporadic IBM had undergone a previous muscle biopsy for confirmation of diagnosis, which was assessed based on previously reported diagnostic criteria.

3. (Other subtypes of) IIM

Five articles (all retrospective cohorts) were included in the analysis.

All studies used a myositis line immunoassay (LIA) (myositis profile 3 or autoimmune inflammatory myopathies 16Ag) for the detection of MSA and MAA, testing for the following MSA: anti-MDA5, TIF1γ, SAE, NXP2, anti-Jo-1, PL-7, PL-12, EJ, OJ, SRP, Mi-2α and Mi-2β; and the following MAA: Ro52, Ku, PM/Scl-100, and PM/Scl-75. All authors described having used the cut-off values according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, scoring negative (- or score < 11), weakly positive (1+ or score 11 to 25), positive (2+), or strongly positive (3+ or score > 25).

Beaton (2021) evaluated a myositis LIA for the diagnosis of suspected IIM. Consecutive patients who had MSA-testing performed or who had an MSA identified by extractable nuclear antigen testing using counter immune electrophoresis were included. Additional ELISA was performed in patients for reporting of anti-HMGCA antibodies. These tests were ordered by hospital specialty teams, with no prespecified criteria. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) was performed to assess the expected IIF pattern for certain MSA. Charts were retrospectively reviewed for the diagnosis of IIM through the ACR/EULAR classification criteria for IIM (which can include muscle biopsy). Patients with a subclassification of sporadic IBM were excluded. Information on funding or conflict of interest are not provided.

The study by Lecouffe-Desprets (2018) aimed to evaluate the contribution of extended myositis-related antibodies determination to the diagnosis, classification, and prognosis of IIM. All patients in whom myositis-related antibody determination was requested over a one-year period were included, yet repeated determinations were excluded. Anti-Jo-1 antibodies were confirmed by an ELISA and IIF was performed to correlate clinico-serological patterns with clinical symptoms. Medical records were analysed for symptoms of IIM and muscle biopsy records. How the diagnosis of IIM was made was unclear.

Montagnese (2019) assessed the utility of MAA and MSA in detecting IIM among a retrospective cohort of neuromuscular patients. All patients that had been tested for MSA and MAA antibodies as part of the diagnostic process were included and for whom clinical data was available. Diagnosis, symptoms at onset, Creatine Kinase (CK) levels, electromyography (EMG) findings and muscle biopsy results were retrospectively collected. The Peter and Bohan criteria were adopted for the diagnosis of IMM (which can include muscle biopsy). Additional stratification in analysis was performed excluding patients with sporadic IBM.

Platteel (2019) evaluated the frequencies and clinical associations of MSA and MAA in routine diagnostics. A retrospective analysis was performed of all patients in the Netherlands in whom extended myositis-related antibody determination was requested between July 2016 and June 2017. In case of duplicate samples, only the first sample was included, and patients solely positive for anti-Ro52 or of whom no clinical data was available, were excluded. IIM diagnosis was made based on the judgement of the treating physician, which could have included a muscle biopsy.

To (2020) evaluated the clinical performance of LIA for MSA and MAA testing. All patients that were tested through the myositis LIA 16Ag between January 2016 and July 2018 were included. Patients without clinical data available were excluded. The diagnosis of IIM was made by the expert treating clinician (possibly based on EMG and muscle biopsy results), and verified by the authors based on available clinical information.

Results

1. Juvenile dermatomyositis

As no relevant literature for JDM was found, no estimates for sensitivity, specificity, or positive predictive value can be given.

2. Inclusion body myositis

Mavroudis (2021) used both a hierarchical bivariate approach and a Bayesian approach to determine pooled sensitivity and specificity of the seven included studies in the meta-analysis. These test characteristics are calculated for differentiating IBM from all other diseases, from PM or DM, from other autoimmune disorders, and from other neuromuscular diseases (NMD).

Twenty-three out of the 62 IBM patients included in the study from Lucchini (2021) tested positive for anti-CN1A (37.1%), whereas in two patients of the 62 IIM-controls antibodies against cN1A were found (3.2%).

The results from Lucchini (2021) and the pooled results from Mavroudis (2021) for sensitivity and specificity are shown in Table 1.

|

|

IBM Anti-cN1A antibodies |

|

|

|

Mavroudis (2021) |

Lucchini (2021) |

|

Sensitivity |

46% (95% CI 36 to 58) |

37.1% (95% CI: 25.1 to 49.1) |

|

Specificity |

91% (95% CI 88 to 95) |

96.8% (95% CI: 92.4 to 100) |

Table 1. Sensitivity and specificity of antibody testing in IBM

3. (Other subtypes of) IIM

Despite the inclusion of MAA on the used lineblot in all studies, the diagnostic value of MSA (excluding MAA) was assessed.

Beaton (2021) included 195 patients, of which 32 (16.4%) were diagnosed with IIM: 13 with DM, five with PM, 8 with anti-synthetase syndrome (ASS) and six with IMNM.

In the study of Lecouffe-Desprets (2018), 280 samples were analysed, of which 237 were included (20 samples were repeated determinations, in eight no final diagnosis was available, and 15 were solely positive for Ro52). Out of the 33 positive tests, 19 were diagnosed with IIM (ten with DM, nine with OM).

Montagnese (2019) included the results of 1229 samples, of which 141 had a final confirmed diagnosis of IIM (11.5%). IMNM was diagnosed in 38 patients, sIBM in 29 patients, PM in 26 patients, DM in 24 patients, and overlap myositis (OM) in 24 patients.

Reference testing through muscle biopsy was performed in 582 of all 1229 patients (47%).

A total of 819 patients were included by Platteel (2019). 187 patients (22.8%) were diagnosed with IIM. No subgroup classification was provided.

To (2020) assessed the outcomes of LIA in 342 patients. IIM was diagnosed in 67 patients (19.6%), which consisted of DM an IMNM (each in 11 patients), ASS (in 7 patients), DM and PM (each in 4 patients) and IBM (in 2 patients).

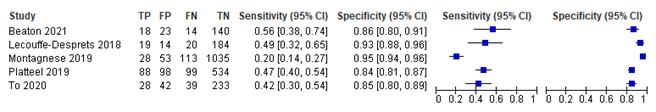

Results from above studies on subtypes of IIM other than JDM or IBM are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Diagnostic accuracy measures found in different studies on MSA testing.

Pooled results for sensitivity and specificity from all studies on IIM are shown in Table 2.

|

|

IIM Myositis-specific antibodies (anti-MDA5, TIF1γ, SAE, NXP2, anti-Jo-1, PL-7, PL-12, EJ, OJ, SRP, Mi-2α, Mi-2β and HMGCR) |

|

Sensitivity |

39.29% (95% CI 28.93 to 50.71) |

|

Specificity |

89.15% (95% CI 83.91 to 92.83) |

Table 2. Pooled sensitivity and specificity of antibody testing in IIM.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. Juvenile dermatomyositis

No GRADE assessment was performed for JDM, as no studies were included in the analysis.

2. Inclusion body myositis

The evidence was derived from (systematic reviews of) case control studies. The level of evidence for all reported outcome measures started at ‘high quality’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures sensitivity and specificity was downgraded by three levels because of unclear methods in patient and control selection, and selective reference testing (-2, risk of bias) and large variation in outcome estimates (-1, inconsistency).

3. (Other subtypes of) IIM

The evidence was derived from retrospective cohort studies. The level of evidence for all reported outcome measures started at ‘high quality’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure sensitivity and specificity was downgraded by two levels because of the risk of the index test having been used in the reference test, and inappropriate reference testing took place in all studies (-1, risk of bias); and because of clinical heterogeneity due to unclear indication for antibody testing and statistical heterogeneity in effect estimates of sensitivity (-1, inconsistency).

Zoeken en selecteren

Search and select

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the diagnostic test accuracy of antibody testing in patients with suspected idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM)?

P: patients in whom any form of IIM is suspected

I: autoantibody testing

C: -

R: muscle biopsy

O: sensitivity, specificity

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered sensitivity and specificity as critical outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined minimal clinically important values for sensitivity and specificity:

- 90% or more is considered a good performance of the diagnostic test;

- 70% to 90% is a reasonable performance and might have potential clinical relevance

Despite being additional diagnostic accuracy measures, the working group decided not to assess positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV). These values depend strongly on the pretest probability of disease in the researched population, and therefore, in order to make generalizable recommendations from the study data, the probabilities of the study population and Dutch population should resemble sufficiently, which is often questionable.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched using relevant search terms until August 2nd 2021. The detailed search strategy is available upon request. The systematic literature search resulted in 490 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- (a) study design (due to the type of question (diagnostic), not only systematic reviews, but also other comparative research (cohort studies, case-control studies), randomized controlled trials if fitting design;

- (b) study population (patients with suspected juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM), inclusion body myositis (IBM) or other subtypes of IIM);

- (c) index test (antibody testing);

- (d) language (English or Dutch);

- (e) publication date (between 2002 and July 2021); and

- (f) availability of full text.

In addition, the working group deemed articles on MSA of interest for JDM and IIM (excluding IBM), whereas anti-cN1A (anti-NT5C1A, anti-mup44) were deemed informative for IBM. As IIM makes up a heterogeneous patient group, articles describing a mixed IIM patient group with a maximum of 10% JDM or IBM were eligible for inclusion.

Articles were screened based on title and abstract. This resulted in 30 articles. After reading the full text, seven articles were eligible for inclusion. A table with reasons for exclusion is presented under the tab Evidence tables.

Results

No articles on patients with JDM, two articles on patients with IBM, and five on patients with other subtypes of IIM were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Beaton TJ, Gillis D, Prain K, Morwood K, Anderson J, Goddard J, Baird T. Performance of myositis-specific antibodies detected on myositis line immunoassay to diagnose and sub-classify patients with suspected idiopathic inflammatory myopathy, a retrospective records-based review. Int J Rheum Dis. 2021 Sep;24(9):1167-1175. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.14174. Epub 2021 Jul 11. PMID: 34250724.

- Damoiseaux J, Mammen AL, Piette Y, Benveniste O, Allenbach Y; ENMC 256th Workshop Study Group. 256th ENMC international workshop: Myositis specific and associated autoantibodies (MSA-ab): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 8-10 October 2021. Neuromuscul Disord. 2022 Jul;32(7):594-608. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2022.05.011. Epub 2022 May 20. PMID: 35644723.

- Herbert MK, Stammen-Vogelzangs J, Verbeek MM, Rietveld A, Lundberg IE, Chinoy H, Lamb JA, Cooper RG, Roberts M, Badrising UA, De Bleecker JL, Machado PM, Hanna MG, Plestilova L, Vencovsky J, van Engelen BG, Pruijn GJ. Disease specificity of autoantibodies to cytosolic 5'-nucleotidase 1A in sporadic inclusion body myositis versus known autoimmune diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Apr;75(4):696-701. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206691. Epub 2015 Feb 24. PMID: 25714931; PMCID: PMC4699257.

- Lecouffe-Desprets M, Hémont C, Néel A, Toquet C, Masseau A, Hamidou M, Josien R, Martin JC. Clinical contribution of myositis-related antibodies detected by immunoblot to idiopathic inflammatory myositis: A one-year retrospective study. Autoimmunity. 2018 Mar;51(2):89-95. doi: 10.1080/08916934.2018.1441830. Epub 2018 Feb 20. PMID: 29463118.

- Lucchini M, Maggi L, Pegoraro E, Filosto M, Rodolico C, Antonini G, Garibaldi M, Valentino ML, Siciliano G, Tasca G, De Arcangelis V, De Fino C, Mirabella M. Anti-cN1A Antibodies Are Associated with More Severe Dysphagia in Sporadic Inclusion Body Myositis. Cells. 2021 May 10;10(5):1146. doi: 10.3390/cells10051146. PMID: 34068623; PMCID: PMC8151681.

- Mavroudis I, Knights M, Petridis F, Chatzikonstantinou S, Karantali E, Kazis D. Diagnostic Accuracy of Anti-CN1A on the Diagnosis of Inclusion Body Myositis. A Hierarchical Bivariate and Bayesian Meta-analysis. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2021 Sep 1;23(1):31-38. doi: 10.1097/CND.0000000000000353. PMID: 34431799.

- Montagnese F, Baba?i? H, Eichhorn P, Schoser B. Evaluating the diagnostic utility of new line immunoassays for myositis antibodies in clinical practice: a retrospective study. J Neurol. 2019 Jun;266(6):1358-1366. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09266-4. Epub 2019 Mar 6. PMID: 30840145.

- Platteel ACM, Wevers BA, Lim J, Bakker JA, Bontkes HJ, Curvers J, Damoiseaux J, Heron M, de Kort G, Limper M, van Lochem EG, Mulder AHL, Saris CGJ, van der Valk H, van der Kooi AJ, van Leeuwen EMM, Veltkamp M, Schreurs MWJ, Meek B, Hamann D. Frequencies and clinical associations of myositis-related antibodies in The Netherlands: A one-year survey of all Dutch patients. J Transl Autoimmun. 2019 Aug 23;2:100013. doi: 10.1016/j.jtauto.2019.100013. PMID: 32743501; PMCID: PMC7388388.

- Tansley SL, Simou S, Shaddick G, Betteridge ZE, Almeida B, Gunawardena H, Thomson W, Beresford MW, Midgley A, Muntoni F, Wedderburn LR, McHugh NJ. Autoantibodies in juvenile-onset myositis: Their diagnostic value and associated clinical phenotype in a large UK cohort. J Autoimmun. 2017 Nov;84:55-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2017.06.007. Epub 2017 Jun 26. PMID: 28663002; PMCID: PMC5656106.

- To F, Ventín-Rodríguez C, Elkhalifa S, Lilleker JB, Chinoy H. Line blot immunoassays in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: retrospective review of diagnostic accuracy and factors predicting true positive results. BMC Rheumatol. 2020 Jul 20;4:28. doi: 10.1186/s41927-020-00132-9. PMID: 32699830; PMCID: PMC7370419.

Evidence tabellen

Evidencetabellen IBM

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mavroudis, 2021

|

Systematic review and meta-analysis

Literature search up to Dec 2020

A: Amlani, 2019 B: Salajegheh, 2011 C: Pluk, 2013 D: Herbert, 2016 E: Lloyd, 2016 F: Tawara, 2017 G: Muro, 2017

Study design: case-control

Setting and Country: UK, Greece

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: no conflict of interest reported; information on funding not disclosed

|

Inclusion criteria SR: (1) study design (case-control); (2) patients should meet diagnostic criteria for included diseases; (3) accessible data from each study; (4) comparing anti-CN1A levels in IBM and other diseases

Exclusion criteria SR: Review studies, studies on familial IBM or in-vitro studies

7 studies included

Important patient characteristics: not reported

N, mean age not reported

Sex: not reported |

Describe index and comparator tests and cut-off point(s):

Index test: Anti-CN1A antibody testing (exact method not reported, cut-off value not reported)

Comparator test: Not reported.

|

Describe reference test and cut-off point(s): Not reported

Prevalence (%) Not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? n.a. |

Endpoint of follow-up: Not reported |

Outcome measures and effect size:

Sensitivity (%) Comparing IBM with different control(sub)groups:

Pooled sensitivity (bivariate random effects model) IBM to all other 45% (95% CI 37 to 53)

Pooled sensitivity (Bayesian approach) IBM to all other 46% (95% CI 36 to 58)

Specificity (%) Comparing IBM with different control(sub)groups:

Pooled specificity (bivariate random effects model) IBM to all other 91% (95% CI 88 to 93)

Pooled specificity (Bayesian approach) IBM to all other 91% (95% CI 88 to 95)

Positive predictive value 0.25 in general population; 0.75 for over 50 years of age |

Authors’ conclusion: “anti-CN1A antibodies are not useful for the diagnosis of IBM.”

General remark: All included studies are of low quality, low patient numbers, and high risk of bias (see bias assessment in article). Therefore results from this review should be interpreted with the utmost caution.

Study design: anti-CN1A antibodies were meant to be researched for their diagnostic value, yet case-control study design for this research purpose increases likelihood of bias.

Heterogeneity: in included studies is much heterogeneity with regard to included patients (different control groups, ages and gender unknown), in index testing (no standardized methodology among studies to detect anti-CN1A antibodies), and in reference testing (unknown if all patients underwent muscle biopsy for reference testing)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lucchini, 2021 |

Type of study: Case-control (62 s-IBM patients and 62 patients with other inflammatory myopathies)

Setting and country: Italy

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial grant, no conflict of interest |

Inclusion criteria: Not reported

Exclusion criteria: Treatment with IVIg, or immunosuppressants in the past 6 months (>5mg prednisolone)

N= 124

Mean age ± SD: 67.3 (9.6) and 63.6 (14.0)

Sex: 63 and 39% M / 37 and 61% F

|

Describe index test: ELISA assay for anti-cN1A

Cut-off point(s): Positive and negative control provided by manufacturer of assays

Comparator test: none

|

Describe reference test: Muscle biopsy

Cut-off point(s): (based on ENMC research diagnostic criteria)

|

Time between the index test en reference test: Reference test before index test

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%) not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (95% CI):

Sensitivity 37.1% (25.1 to 49.1)

Specificity 96.8% (92.4 to 100)

PPV 92% (81.4 to 100)

NPV 60.6% (51.0 to 70.2) |

Unclear how controls were selected, possible bias in patient selection. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Abbreviations: UK: United Kingdom, SR: systematic review, IBM: Inclusion Body Myositis, CI: confidence interval, IVIg: intravenous immunoglobulins, ELISA: Enzyme Linked Immuno Sorbent Assay, ENMC: European Neuromuscular Centre

Evidence tabellen IIM

Abbreviations (alphabetical): ACR/EULAR: American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism, CI: Confidence Interval, CIEP: counter immune electrophoresis, ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, IBM: Inclusion Body Myositis, IIF: indirect immunofluorescence, IIM: Idiopathic inflammatory myopathy, LIA: Line immunoassay, MAA: Myositis Associated antibody, MSA: Myositis Specific antibody

Risk of Bias tables

For IBM

Risk of bias for systematic reviews

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Mavroudis, 2021 |

No |

Unclear |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Unclear |

Unclear (no funding reported) |

Risk of bias for other studies

|

Study reference |

Patient selection |

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Lucchini, 2021 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? No

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Unclear

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? No

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Unclear: each test included a positive and negative control provided by the manufacturer, but specific threshold is unlcear.

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? No

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? No (only cases, not controls)

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias? RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias? RISK: HIGH |

Comment: Patients with known disease were included; therefore no real conclusion can be made on the diagnostic value of anti-NT5C1A, as this was not researched as a diagnosticum. |

For IIM

|

Study reference |

Patient selection |

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Beaton, 2021 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Unclear: patients with a sub-classification of sporadic IBM were excluded from diagnosis

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Probably no: index testing occurred before “reference testing”, possibly aiding in making diagnosis

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes (but only part of patients underwent muscle biopsy)

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? Yes: patients that undergo MSA testing might not necessarily be suspected of IIM

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No, yet the inappropriate reference test was applied, pre-specified was a muscle biopsy. The used reference can include muscle biopsy but is not mandatory |

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

||

|

Lecouffe-Desprets, 2018 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Unclear: patients who tested positive for anti-Ro52 were excluded instead of the performance of a sensitivity analysis, and patients in whom no final diagnosis was established were excluded.

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Unclear: not clearly defined how diagnosis was made.

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes (but only part of patients underwent muscle biopsy)

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? No |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? Yes: patients that undergo MSA testing might not necessarily be suspected of IIM

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No, yet the inappropriate reference test was applied, golden standard is a muscle biopsy. Current diagnosis is not objectifiable. |

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias? RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

||

|

Montagnese, 2019 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes; yet patients without available clinical data were excluded

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Probably no: index testing occurred before “reference testing”, possibly aiding in making diagnosis

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes (but only part of patients underwent muscle biopsy, 582 (47%))

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? No: patients without available clinical data were excluded |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? Yes: patients that undergo MSA testing might not necessarily be suspected of IIM

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No, yet the inappropriate reference test was applied, pre-specified was a muscle biopsy. The used reference can include muscle biopsy but is not mandatory |

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

|

|

Platteel, 2019 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes; yet patients without available clinical data were excluded

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Unclear: IIM diagnosis was made based on the judgement of the treating physician (not objectifiable)

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Probably no: index testing occurred before “reference testing”, possibly aiding in making diagnosis |

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes (but unclear whether patients underwent golden standard of muscle biopsy)

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Unclear how diagnosis was made, therefore unclear whether it was made with the same measures

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes: only patients without available clinical data were excluded (yet this was pre-specified in methods) |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? Yes: patients that undergo MSA testing might not necessarily be suspected of IIM

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No, yet the inappropriate reference test was applied, golden standard is a muscle biopsy. Current diagnosis is not objectifiable. |

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias? RISK: HIGH |

|

|

To, 2020 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? No: limited to patients being reviewed in tertiary IIM, systemic sclerosis and neuromuscular outpatient clinics

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes; yet patients without available clinical data were excluded

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Unclear: IIM diagnosis was made based on the judgement of the treating physician, and verified by authors based on review of clinical information (not objectifiable)

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Probably no: index testing occurred before “reference testing”, possibly aiding in making diagnosis |

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes (but only part of patients underwent muscle biopsy)

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Unclear how diagnosis was made, therefore unclear whether it was made with the same measures

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes: only patients without available clinical data were excluded (yet this was pre-specified in methods) |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No, yet the inappropriate reference test was applied, golden standard is a muscle biopsy. Current diagnosis is not objectifiable. |

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias? RISK: HIGH |

Table of excluded studies

For JDM

|

Author, year |

Reason of exclusion |

|

Tansley 2017 |

Wrong population (patients with JIIM, not specifically JDM) |

|

Yu 2016 |

Wrong antibodies of interest (MAA's = myositis-associated autoantibodies) |

|

Iwata 2018 |

No control group |

|

Hou 2021 |

Wrong population (patients with JIIM, not specifically JDM) |

|

Pachman 2018 |

Wrong study design (narrative review) |

|

Kwiatkowska 2021 |

Wrong study design (non-systematic review) |

For IBM

|

Author, year |

Reason of exclusion |

|

Greenberg, 2014 |

Outcome of interest non-calculable, no reference testing |

|

Herbert, 2016 |

Is included in systematic review Mavroudis, 2021 |

|

Muro, 2017 |

Is included in systematic review Mavroudis, 2021 |

|

Ronja-Undomsart, 2012 |

Wrong antibodies of interest (only anti-cN1A) |

|

Rietveld, 2018 |

Wong population (Sjögren or SLE) |

|

Felice, 2018 |

No control group |

|

Lloyd, 2016 |

Is included in systematic review Mavroudis, 2021 |

For IIM

|

Author, year |

Redenen van exclusie |

|

Ghirardello, 2010 |

Wrong study design (case-control, therefore wrong population) |

|

Hengstman, 2005 |

Wrong study design (case-control, therefore wrong population) |

|

Hoshino, 2010 |

Wrong study design (case-control, therefore wrong population) |

|

Kao, 2004 |

Wrong study design (nested case-control, therefore wrong population) |

|

Lackner, 2020 |

No separate analysis for MSA |

|

Li, 2017 |

Wrong type of included studies (case-controls) |

|

Li, 2021 |

Wrong type of included studies (case-controls) |

|

Mammen, 2015 |

Wrong study design (case-control, therefore wrong population) |

|

Richards, 2019 |

Wrong study design (case-control, therefore wrong population) |

|

Tan, 2016 |

Insufficient data for separate assessment of MSA |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 07-02-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 07-02-2024

Algemene gegevens

The development of this guideline module was supported by the Knowledge Institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists (www.demedischspecialist.nl/ kennisinstituut) and was financed from the Quality Funds for Medical Specialists (SKMS). The financier has had no influence whatsoever on the content of the guideline module.

Samenstelling werkgroep

A multidisciplinary working group was set up in 2020 for the development of the guideline module, consisting of representatives of all relevant specialisms and patient organisations (see the Composition of the working group) involved in the care of patients with IIM/myositis.

Working group

- Dr. A.J. van der Kooi, neurologist, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie (chair)

- Dr. U.A. Badrising, neurologist, LUMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. C.G.J. Saris, neurologist, Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. S. Lassche, neurologist, Zuyderland MC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. J. Raaphorst, neurologist, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. J.E. Hoogendijk, neurologist, UMC Utrecht. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Drs. T.B.G. Olde Dubbelink, neurologist, Rijnstate, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. I.L. Meek, rheumatologist, Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Reumatologie

- Dr. R.C. Padmos, rheumatologist, Erasmus MC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Reumatologie

- Prof. dr. E.M.G.J. de Jong, dermatologist, werkzaam in het Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Dermatologie en Venereologie

- Drs. W.R. Veldkamp, dermatologist, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Dermatologie en Venereologie

- Dr. J.M. van den Berg, pediatrician, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde

- Dr. M.H.A. Jansen, pediatrician, UMC Utrecht. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde

- Dr. A.C. van Groenestijn, rehabilitation physician, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging van Revalidatieartsen

- Dr. B. Küsters, pathologist, Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Pathologie

- Dr. V.A.S.H. Dalm, internist, Erasmus MC. Nederlandse Internisten Vereniging

- Drs. J.R. Miedema, pulmonologist, Erasmus MC. Nederlandse Vereniging van Artsen voor Longziekten en Tuberculose

- I. de Groot, patient representatieve. Spierziekten Nederland

Advisory board

- Prof. dr. E. Aronica, pathologist, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. External expert.

- Prof. dr. D. Hamann, Laboratory specialist medical immunology, UMC Utrecht. External expert.

- Drs. R.N.P.M. Rinkel, ENT physician, Amsterdam UMC, locatie VUmc. Vereniging voor Keel-Neus-Oorheelkunde en Heelkunde van het Hoofd-Halsgebied

- dr. A.S. Amin, cardiologist, werkzaam in werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Cardiologie

- dr. A. van Royen-Kerkhof, pediatrician, UMC Utrecht. External expert.

- dr. L.W.J. Baijens, ENT physician, Maastricht UMC+. External expert.

- Em. Prof. Dr. M. de Visser, neurologist, Amsterdam UMC. External expert.

Methodological support

- Drs. T. Lamberts, senior advisor, Knowledge institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists

- Drs. M. Griekspoor, advisor, Knowledge institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists

- Dr. M. M. J. van Rooijen, advisor, Knowledge institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists

Belangenverklaringen

The ‘Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling’ has been followed. All working group members have declared in writing whether they have had direct financial interests (attribution with a commercial company, personal financial interests, research funding) or indirect interests (personal relationships, reputation management) in the past three years. During the development or revision of a module, changes in interests are communicated to the chairperson. The declaration of interest is reconfirmed during the comment phase.

An overview of the interests of working group members and the opinion on how to deal with any interests can be found in the table below. The signed declarations of interest can be requested from the secretariat of the Knowledge Institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

van der Kooi |

Neuroloog, Amsterdam UMC |

|

Immediate studie (investigator initiated, IVIg behandeling bij therapie naive patienten). --> Financiering via Behring. Studie januari 2019 afgerond |

Geen restricties (middel bij advisory board is geen onderdeel van rcihtlijn) |

|

Miedema |

Longarts, Erasmus MC |

Geen. |

|

Geen restricties |

|

Meek |

Afdelingshoofd a.i. afdeling reumatische ziekten, Radboudumc |

Commissaris kwaliteit bestuur Nederlandse Vereniging voor Reumatologie (onkostenvergoeding) |

Medisch adviseur myositis werkgroep spierziekten Nederland |

Geen restricties |

|

Veldkamp |

AIOS dermatologie Radboudumc Nijmegen |

|

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Padmos |

Reumatoloog, Erasmus MC |

Docent Breederode Hogeschool (afdeling reumatologie EMC wordt hiervoor betaald) |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Dalm |

Internist-klinisch immunoloog Erasmus MC |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Olde Dubbelink |

Neuroloog in opleiding Canisius-Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis, Nijmegen |

Promotie onderzoek naar diagnostiek en outcome van het carpaletunnelsyndroom (onbetaald) |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

van Groenestijn |

Revalidatiearts AmsterdamUMC, locatie AMC |

Geen. |

Lokale onderzoeker voor de I'M FINE studie (multicentre, leiding door afdeling Revalidatie Amsterdam UMC, samen met UMC Utrecht, Sint Maartenskliniek, Klimmendaal en Merem. Evaluatie van geïndividualiseerd beweegprogramma o.b.v. combinatie van aerobe training en coaching bij mensen met neuromusculaire aandoeningen, NMA). Activiteiten: screening NMA-patiënten die willen participeren aan deze studie. Subsidie van het Prinses Beatrix Spierfonds. |

Geen restricties |

|

Lassche |

Neuroloog, Zuyderland Medisch Centrum, Heerlen en Sittard-Geleen |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

de Jong |

Dermatoloog, afdelingshoofd Dermatologie Radboudumc Nijmegen |

Geen. |

All funding is not personal but goes to the independent research fund of the department of dermatology of Radboud university medical centre Nijmegen, the Netherlands |

Geen restricties |

|

Hoogendijk |

Neuroloog Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht (0,4) Neuroloog Sionsberg, Dokkum (0,6) |

beide onbetaald |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Badrising |

Neuroloog Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum |

(U.A.Badrising Neuroloog b.v.: hoofdbestuurder; betreft een vrijwel slapende b.v. als overblijfsel van mijn eerdere praktijk in de maatschap neurologie Dirksland, Het van Weel-Bethesda Ziekenhuis) |

Medisch adviseur myositis werkgroep spierziekten Nederland |

Geen restricties |

|

van den Berg |

Kinderarts-reumatoloog/-immunoloog Emma kinderziekenhuis/ Amsterdam UMC |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

de Groot |

Patiënt vertegenwoordiger/ ervaringsdeskundige: voorzitter diagnosewerkgroep myositis bij Spierziekten Nederland in deze commissie patiënt(vertegenwoordiger) |

|

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Küsters |

Patholoog, Radboud UMC |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Saris |

Neuroloog/ klinisch neurofysioloog, Radboudumc |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Raaphorst |

Neuroloog, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen. |

|

Restricties m.b.t. opstellen aanbevelingen IvIg behandeling. |

|

Jansen |

Kinderarts-immunoloog-reumatoloog, WKZ UMC Utrecht |

Docent bij Mijs-instituut (betaald) |

Onderzoek biomakers in juveniele dermatomyositis. Geen belang bij uitkomst richtlijn. |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Attention was paid to the patient's perspective by offering the Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland to take part in the working group. Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland has made use of this offer, the Dutch Artritis Society has waived it. In addition, an invitational conference was held to which the Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland, the Dutch Artritis Society nd Patiëntenfederatie Nederland were invited and the patient's perspective was discussed. The report of this meeting was discussed in the working group. The input obtained was included in the formulation of the clinical questions, the choice of outcome measures and the considerations. The draft guideline was also submitted for comment to the Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland, the Dutch Artritis Society and Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, and any comments submitted were reviewed and processed.

Qualitative estimate of possible financial consequences in the context of the Wkkgz

In accordance with the Healthcare Quality, Complaints and Disputes Act (Wet Kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen Zorg, Wkkgz), a qualitative estimate has been made for the guideline as to whether the recommendations may lead to substantial financial consequences. In conducting this assessment, guideline modules were tested in various domains (see the flowchart on the Guideline Database).

The qualitative estimate shows that there are probably no substantial financial consequences, see table below.

|

Module |

Estimate |

Explanation |

|

Module diagnostische waarde ziekteverschijnselen |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Optimale strategie aanvullende diagnostiek myositis |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Autoantibody testing in myositis |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Screening op maligniteiten |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Screening op comorbiditeiten |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Immunosuppressie en -modulatie bij IBM |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Treatment with Physical training |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Treatment of dysphagia in myositis |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Treatment of dysphagia in IBM |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Topical therapy |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Treatment of calcinosis |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Organization of care |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

Werkwijze

Methods

AGREE

This guideline module has been drawn up in accordance with the requirements stated in the Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 report of the Advisory Committee on Guidelines of the Quality Council. This report is based on the AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Clinical questions

During the preparatory phase, the working group inventoried the bottlenecks in the care of patients with IIM. Bottlenecks were also put forward by the parties involved via an invitational conference. A report of this is included under related products.

Based on the results of the bottleneck analysis, the working group drew up and finalized draft basic questions.

Outcome measures

After formulating the search question associated with the clinical question, the working group inventoried which outcome measures are relevant to the patient, looking at both desired and undesired effects. A maximum of eight outcome measures were used. The working group rated these outcome measures according to their relative importance in decision-making regarding recommendations, as critical (critical to decision-making), important (but not critical), and unimportant. The working group also defined at least for the crucial outcome measures which differences they considered clinically (patient) relevant.

Methods used in the literature analyses

A detailed description of the literature search and selection strategy and the assessment of the risk-of-bias of the individual studies can be found under 'Search and selection' under Substantiation. The assessment of the strength of the scientific evidence is explained below.

Assessment of the level of scientific evidence

The strength of the scientific evidence was determined according to the GRADE method. GRADE stands for Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (see http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). The basic principles of the GRADE methodology are: naming and prioritizing the clinically (patient) relevant outcome measures, a systematic review per outcome measure, and an assessment of the strength of evidence per outcome measure based on the eight GRADE domains (downgrading domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias; domains for upgrading: dose-effect relationship, large effect, and residual plausible confounding).

GRADE distinguishes four grades for the quality of scientific evidence: high, fair, low and very low. These degrees refer to the degree of certainty that exists about the literature conclusion, in particular the degree of certainty that the literature conclusion adequately supports the recommendation (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

Definitie |

|

|

High |

|

|

Moderate |

|

|

Low |

|

|

Very low |

|

When assessing (grading) the strength of the scientific evidence in guidelines according to the GRADE methodology, limits for clinical decision-making play an important role (Hultcrantz, 2017). These are the limits that, if exceeded, would lead to an adjustment of the recommendation. To set limits for clinical decision-making, all relevant outcome measures and considerations should be considered. The boundaries for clinical decision-making are therefore not directly comparable with the minimal clinically important difference (MCID). Particularly in situations where an intervention has no significant drawbacks and the costs are relatively low, the threshold for clinical decision-making regarding the effectiveness of the intervention may lie at a lower value (closer to zero effect) than the MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Considerations

In addition to (the quality of) the scientific evidence, other aspects are also important in arriving at a recommendation and are taken into account, such as additional arguments from, for example, biomechanics or physiology, values and preferences of patients, costs (resource requirements), acceptability, feasibility and implementation. These aspects are systematically listed and assessed (weighted) under the heading 'Considerations' and may be (partly) based on expert opinion. A structured format based on the evidence-to-decision framework of the international GRADE Working Group was used (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). This evidence-to-decision framework is an integral part of the GRADE methodology.

Formulation of conclusions

The recommendations answer the clinical question and are based on the available scientific evidence, the most important considerations, and a weighting of the favorable and unfavorable effects of the relevant interventions. The strength of the scientific evidence and the weight assigned to the considerations by the working group together determine the strength of the recommendation. In accordance with the GRADE method, a low evidential value of conclusions in the systematic literature analysis does not preclude a strong recommendation a priori, and weak recommendations are also possible with a high evidential value (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). The strength of the recommendation is always determined by weighing all relevant arguments together. The working group has included with each recommendation how they arrived at the direction and strength of the recommendation.

The GRADE methodology distinguishes between strong and weak (or conditional) recommendations. The strength of a recommendation refers to the degree of certainty that the benefits of the intervention outweigh the harms (or vice versa) across the spectrum of patients targeted by the recommendation. The strength of a recommendation has clear implications for patients, practitioners and policy makers (see table below). A recommendation is not a dictate, even a strong recommendation based on high quality evidence (GRADE grading HIGH) will not always apply, under all possible circumstances and for each individual patient.

|

Implications of strong and weak recommendations for guideline users |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Strong recommendation |

Weak recommendations |

|

For patients |

Most patients would choose the recommended intervention or approach and only a small number would not. |

A significant proportion of patients would choose the recommended intervention or approach, but many patients would not. |

|

For practitioners |

Most patients should receive the recommended intervention or approach. |

There are several suitable interventions or approaches. The patient should be supported in choosing the intervention or approach that best reflects his or her values and preferences. |

|

For policy makers |

The recommended intervention or approach can be seen as standard policy. |

Policy-making requires extensive discussion involving many stakeholders. There is a greater likelihood of local policy differences. |

Organization of care

In the bottleneck analysis and in the development of the guideline module, explicit attention was paid to the organization of care: all aspects that are preconditions for providing care (such as coordination, communication, (financial) resources, manpower and infrastructure). Preconditions that are relevant for answering this specific initial question are mentioned in the considerations. More general, overarching or additional aspects of the organization of care are dealt with in the module Organization of care.

Commentary and authtorisation phase

The draft guideline module was submitted to the involved (scientific) associations and (patient) organizations for comment. The comments were collected and discussed with the working group. In response to the comments, the draft guideline module was modified and finalized by the working group. The final guideline module was submitted to the participating (scientific) associations and (patient) organizations for authorization and authorized or approved by them.

References

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, . GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Literature search strategy

|

Richtlijn: NVN Myositis |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag: UV3 Wat is de plaats van het testen met antistoffen als aanvullende diagnostiek bij het vaststellen van de diagnose Myositis? |

|

|

Database(s): Ovid/Medline, Embase |

Datum: 2-8-2021 |

|

Periode: 2002- |

Talen: nvt |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Ingeborg van Dusseldorp |

|

|

BMI zoekblokken: voor verschillende opdrachten wordt (deels) gebruik gemaakt van de zoekblokken van BMI-Online https://blocks.bmi-online.nl/ Bij gebruikmaking van een volledig zoekblok zal naar de betreffende link op de website worden verwezen. |

|

|

Toelichting: Voor deze vraag is gezocht met de volgende elementen:

Myositis EN antistoffen EN diagnostische accuratesse

Van de 6 sleutelartikelen wordt het artikel van Benveniste wordt niet gevonden omdat het een algemeen diagnostisch artikel betreft. De overige 5 sleutelartikelen worden wel gevonden. Indien bij de selectie blijkt dat niet voldoende evidence wordt gevonden kan besloten worden om de zoekstrategie uit te breiden.

Niet gevonden:

1. Advances in serological diagnostics of inflammatory myopathies Benveniste O., Stenzel W., Allenbach Y. Current Opinion in Neurology (2016) 29:5 (662-673). Date of Publication: 2016 |

|

|

Te gebruiken voor richtlijnen tekst: In de databases Embase en Ovid/Medline is op 2 augustus 2021 met relevante zoektermen gezocht naar systematische reviews, RCTs en observationele studies over de plaats van het testen met antistoffen als aanvullende diagnostiek bij het vaststellen van de diagnose Myositis. Er is gezocht vanaf het jaar 2002. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 906 unieke treffers op. |

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

EMBASE |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SRs |

39 |

42 |

58 |

|

RCTs |

90 |

116 |

165 |

|

Observationele studies |

553 |

462 |

683 |

|

Overig |

|

|

|

|

Totaal |

|

|

906 |

Zoekstrategie

Embase

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#25 |

#7 NOT #24 |

1 |

|

#24 |

#7 AND #23 |

5 |

|

#23 |

#18 OR #19 OR #20 |

682 |

|

#22 |

#20 NOT #19 NOT #18 |

553 |

|

#21 |

#19 NOT #18 |

90 |

|

#20 |

#13 AND (#16 OR #17) |

641 |

|

#19 |

#13 AND #15 |

95 |

|

#18 |

#13 AND #14 |

39 |

|

#17 |

'controlled study'/de OR 'controlled clinical trial'/de OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/6 trial):ti,ab,kw) OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/6 study):ti,ab,kw) OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/1 active):ti,ab,kw) OR 'open label*':ti,ab,kw OR (((double OR two OR three OR multi OR trial) NEAR/1 (arm OR arms)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((allocat* NEAR/10 (arm OR arms)):ti,ab,kw) OR placebo*:ti,ab,kw OR 'sham-control*':ti,ab,kw OR (((single OR double OR triple OR assessor) NEAR/1 (blind* OR masked)):ti,ab,kw) OR nonrandom*:ti,ab,kw OR 'non-random*':ti,ab,kw OR 'quasi-experimental':ti,ab,kw OR crossover:ti,ab,kw OR 'cross over':ti,ab,kw OR 'parallel group*':ti,ab,kw OR 'factorial trial':ti,ab,kw OR 'phase 2 clinical trial'/de OR 'phase 3 clinical trial'/de OR 'phase 4 clinical trial'/de OR ((phase NEAR/5 (study OR trial)):ti,ab,kw) OR 'case control study'/de OR ((case* NEAR/6 (matched OR control*)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((match* NEAR/6 (pair OR pairs OR cohort* OR control* OR group* OR healthy OR age OR sex OR gender OR patient* OR subject* OR participant*)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((propensity NEAR/6 (scor* OR match*)):ti,ab,kw) OR (('major clinical study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/exp OR 'observational study'/de OR 'cross-sectional study'/de OR 'multicenter study'/de OR cohort*:ti,ab,kw OR 'follow up':ti,ab,kw OR followup:ti,ab,kw OR longitudinal*:ti,ab,kw OR prospective*:ti,ab,kw OR retrospective*:ti,ab,kw OR observational*:ti,ab,kw OR 'cross sectional*':ti,ab,kw OR cross?ectional*:ti,ab,kw OR multicent*:ti,ab,kw OR 'multi-cent*':ti,ab,kw OR consecutive*:ti,ab,kw) AND (group:ti,ab,kw OR groups:ti,ab,kw OR subgroup*:ti,ab,kw OR versus:ti,ab,kw OR vs:ti,ab,kw OR compar*:ti,ab,kw OR 'odds ratio*':ab OR 'relative odds':ab OR 'risk ratio*':ab OR 'relative risk*':ab OR aor:ab OR arr:ab OR rrr:ab OR ((('or' OR 'rr') NEAR/6 ci):ab))) OR versus:ti OR vs:ti OR compar*:ti OR 'comparative study'/exp OR ((compar* NEAR/1 study):ti,ab,kw) |

12280807 |

|

#16 |

'major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'case control study'/de OR 'family study'/de OR 'longitudinal study'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR 'prospective study'/de OR 'comparative study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR ((cohort NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('case control' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('follow up' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (observational NEAR/1 (study OR studies)) OR ((epidemiologic NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('cross sectional' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) |

6613890 |

|

#15 |