Cancer screening in myositis

Uitgangsvraag

What should screening for malignancies in patients with a recent diagnosis of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) look like?

Hoe dient screening op maligniteiten eruit te zien bij recent gediagnosticeerde myositis patiënten?

Aanbeveling

Aanbeveling

Screen patiënten met een recente of nieuwe diagnose myositis (IIM) voor maligniteiten, behoudens bij JDM en IBM.

Op basis van aanwezige risicofactoren kan de screeningsstrategie worden bepaald:

- Geen hoog-risicofactoren: voer de basisscreening uit bij diagnose

- 1 hoog-risicofactor: voer de uitgebreide screening uit bij de diagnose

- ≥2 hoog-risicofactoren: voer de uitgebreide screening uit bij de diagnose, waarna jaarlijks de basisscreening moet worden herhaald gedurende 3 jaar

Bepaal lokaal welke strategie (PET/CT of een set van conventionele screeningsmethoden, zie gekaderde rationale) voor de uitgebreide screening op maligniteiten bij patiënten met een recente myositis diagnose ingezet moet worden. Neem hierbij de patiëntvoorkeuren, kosten, en huidige praktijk in overweging. Weeg bij de aanwezigheid van intermediaire risicofactoren af of deze leiden tot een andere screeningsstrategie (Oldroyd, 2023).

Moedig patiënten aan en informeer over het belang om te (blijven) participeren in landelijke en/of regionale leeftijds- of geslachtsgebonden screeningsprogramma’s.

Overwegingen

Considerations – from evidence to recommendation

Pros and cons of the intervention and the quality of the evidence

18F-FDG PET/CT imaging and conventional screening seem to have a similar performance in detecting malignancies in patients with recently diagnosed IIM, in which sensitivity for PET/CT varies from 0.0 to 0.67, and for conventional screening from 0.85 to 0.98. For NPV the estimates vary from 0.94 (PET/CT) to 0.96-1.0 (conventional screening). These marginal differences do not translate into a clinically relevant improvement for patients. The level of evidence for these found diagnostic accuracy estimates is low, as these are based on only two studies with low patient numbers and a very low prevalence of malignancies. This means that the conclusion can change if new evidence is presented. In addition, as this module focused on screening after IIM diagnosis was established, the results of PET/CT and conventional screening in detecting cancer-associated myositis within 3 years before IIM diagnosis is unclear.

The studies report that the advantage of PET/CT for screening of malignancies is that it is only a single test, compared to the several different tests that are part of conventional screening. Therefore, PET/CT is more convenient for both the patient and the physician. However, both screening strategies have potential harmful effects due to the patient being exposed to radioactive radiation. When multiple tests are applied during conventional screening, it might be considered to leave out a CT-examination, yet this is not possible in a single PET/CT-examination. The use of radioactive glucose in a PET/CT-examination should not be an objection to perform the test, as the patient clears the radioactive contrast within a day, and it does not contribute to a higher effective dose of radiation exposure (RIVM, 2011).

Values and preferences of patients

From the patient perspective, conventional screening and PET/CT both have their (dis)advantages: conventional screening is in general considered to be more demanding (because of more tests and more invasive tests), whereas PET/CT is a single screening method that results in less traveling expenses to the hospital and is completed more quickly. However, PET/CT in general is less available and can have longer waiting times. From the limited evidence, both strategies seem to have similar diagnostic performance in detecting malignancies. Therefore, the preferred screening strategy should be decided upon in continuous dialogue with the patient. General (dis)advantages of oncologic screening should also be discussed.

Costs

The cost-effectiveness of the screening for malignancies in patients with IIM remains unknown. Costs for diagnostic modalities (among which tests in both basic- and extensive screening, and PET/CT) differ per hospital. A cost calculation of a screening strategy with conventional tests and one with PET/CT can lead to different outcomes on the local level, and therefore lead to other cost-effectiveness conclusions.

Acceptability, feasibility and implementation

Both diagnostic procedures (PET/CT and conventional tests in the basic and extensive screening strategy) are acceptable and feasible in current clinical practice. Screening of malignancies in patients with newly diagnosed IIM is already standard practice, and every centre should be able to organise adequate care for these patients. Local availability of PET/CT might influence the choice for screening strategy (not every centre has its own PET/CT, yet service level agreements should be in place to have access to this diagnostic modality), but as both strategies seem to perform equally, the focus should be on the patient preference for screening strategy.

Recommendations

Rationale

Uitgebreidere screeningshandvatten zijn te vinden in Oldroyd (2023).

|

Bij de screening van patiënten met nieuw-gediagnosticeerde idiopathische inflammatoire myopathie (IIM) spelen in de praktijk 3 vragen: wie doet het, wanneer moet het gebeuren, en hoe dient het te gebeuren?

Wie De verantwoordelijkheid van de behandeling en screening ligt bij de hoofdbehandelaar. Deze schakelt zelf de expertise van andere specialismen in als hij dat nodig acht.

Wanneer en hoe De indicatiestelling voor de screening strategie hangt af van de aanwezige risicofactoren (Oldroyd, 2021):

De weging van de eventuele aanwezigheid van gedefinieerde intermediate risicofactoren in andere (buitenlandse) literatuur ligt bij het expertise-behandelteam.

PET/CT en conventionele screening (bestaande uit meerdere onderzoeken) lijken van gelijke diagnostische waarde te zijn. Er kan een onderscheid worden gemaakt in basisscreening en uitgebreide screening: Basis:

Uitgebreid (NB: op basis van patiëntvoorkeuren en lokale beschikbaarheid van aanvullende diagnostiek, kan overwogen worden het beeldvormend onderzoek van de uitgebreide screening te vervangen door een PET-CT):

Indien één of meerdere van bovenstaande aanvullende onderzoeken <6 maanden vóór het moment van screenen is verricht, EN geen alarmsymptomen bij anamnese/lichamelijk onderzoek zijn, kan overwogen worden dit onderzoek niet te herhalen.

Overig aanvullend onderzoek is op indicatie bij gerichte verdenking op basis van screening |

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

An increased incidence of malignancies is found in adult patients with a recent diagnosis of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM, “myositis”), with a Standardized Incidence Ratio (SIR) varying between 2.0-2.5 (for IIM in general) to 2.0-8.0 (for dermatomyositis, DM) (Tiniakou & Mammen, 2017). Cancer-associated myositis is defined as a malignancy occurring within 3 years before or after the diagnosis of IIM (Lilleker, 2018). This timeframe is corroborated by the finding that 72% of cancers occur within five years of IIM diagnosis (Leatham, 2018). Survival of patients with “cancer-associated myositis” is worse than in those with non-cancer-associated myositis or malignancies in absence of IIM (Kang, 2016). The incidence of cancer is different between subtypes (e.g. DM and IMNM), and within subtypes, in part related the presence of an MSA. Therefore, screening for malignancies during the period of, or direct after, diagnosing IIM is important and part of usual care, yet what this screening consists of, varies in practice. This variation might be attributed to different factors; among others the availability of new diagnostic instruments (e.g. PET/CT), costs, and patient acceptance. How screening should take place for recently diagnosed IIM patients, should be established.

IBM and JDM are not associated with increased cancer risk, and are therefore not included in the review of the literature and recommendations in this module (Shelly, 2021; Morris, 2010).

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that 18F-FDG PET/CT examination has little to no difference in diagnostic performance compared to conventional screening* in detecting malignancies in patients with recently diagnosed idiopathic inflammatory myopathy.

Source: Maliha (2019), Selva – O’Callaghan (2010) |

* conventional screening as performed in the studies through complete physical examination, blood tests with serum tumor marker analysis, CT thorax/abdomen/pelvis, endoscopy, and in women mammography and gynaecological examination including endovaginal ultrasound.

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

One retrospective cohort study and one prospective cohort study were included in the analysis.

Maliha (2019) compared the performance of PET/CT to conventional tests for cancer screening in autoimmune inflammatory myopathy patients. A retrospective cohort of 63 patients who had undergone PET/CT and who had a confirmed diagnosis of IIM was examined. Those patients that had a known malignancy before their IIM diagnosis or who had had a cancer diagnosis before the PET/CT scan, were excluded. The scan was performed from the base of the skull to the upper thighs, on patients who had fasted for 6 hours, with barium sulfate oral contrast and 18F-FDG injected intravenously. Conventional screening for these patients consisted of physical and gynaecological examination (in women), blood tests, urine analysis, X-thorax, gastroscopy, colonoscopy, CT thorax/abdomen/pelvis, mammography, endovaginal ultrasound (in women), and serum tumor marker analysis. Both the PET/CT and conventional screening were classified as True Positive (TP), False Positive (FP), True Negative (TN), or False Negative (FN), based on whether a malignancy was suspected on initial testing, and histopathological results as reference test. All results were retrieved from the patients’ medical records.

In the prospective cohort of Selva – O’Callaghan (2010), the aim was to determine the value of PET/CT for diagnosing occult malignant disease in patients with IIM compared with broad conventional cancer screening. Consecutive adult patients with a recent diagnosis of polymyositis (PM) or dermatomyositis (DM) were included in the study. After inclusion patients underwent PET/CT scan 60 to 90 minutes after tracer injection. The results of the PET/CT were interpreted by an experienced nuclear medicine physician blinded to the conventional screening results, and a radiologist. The score for the PET/CT went from 1 to 5 (1 = definitely malignant, 2 = probably malignant, 3 = equivocal, 4 = probably benign, 5 = definitely benign), based on consensus of both assessors. For the analysis, scores were considered as either positive (score 1 or 2), negative (score 4 or 5), or inconclusive (score 3). Inconclusive results were analysed as negative. The conventional screening consisted of one or more of the following: complete physical examination, laboratory tests, thoracoabdominal CT, tumor marker analysis, and in women mammography, gynaecologic examination including ultrasonography. To confirm malignancy, histological evidence through biopsy or resection was obtained. The median follow-up of patients with a negative or inconclusive PET/CT was 14 months (interquartile range 8 to 30 months).

Results

Maliha (2019) included 63 patients (31 with DM, 25 with OM, 1 with IBM, 1 with PM, 1 with orbital myositis and 4 with unspecified myositis). Three tumors were found: squamous skin cell carcinoma, ductal carcinoma of the breast, and multiple myeloma, none of which were found by PET/CT.

Selva – O’Callaghan (2010) included 55 patients in the analysis (49 with DM, 6 with PM), in whom 9 tumors were found. They were located in the breast (n = 5), or in the lung, pancreas, vagina, and colon (n = 1 each). PET/CT identified 6 of these correctly, conventional screening identified 7 correctly.

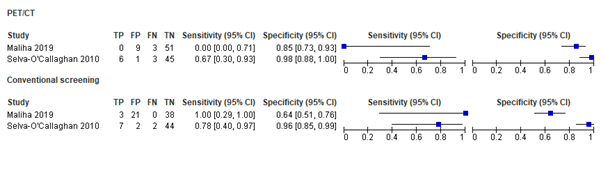

The findings from both studies for sensitivity and specificity (with respective 95% confidence intervals) on cancer diagnosis are graphically depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Sensitivity and specificity found in different studies for PET/CT and conventional screening in diagnosing malignancies.

The findings on positive predictive value and negative predictive value (with respective 95% confidence intervals) are shown in Table 1.

|

|

18F-FDG PET/CT examination |

Conventional screening |

||

|

Maliha (2019) |

Selva (2010) |

Maliha (2019) |

Selva (2010) |

|

|

PPV |

0.0 (0.0 to 0.71) |

0.86 (0.42 to1.00) |

0.13 (0.0 to 0.26) |

0.78 (0.40 to 0.97) |

|

NPV |

0.94 (0.88 to 1.00) |

0.94 (0.83 to 0.99) |

1.00 (0.29 to 1.00) |

0.96 (0.85 to 0.99) |

Table 1. Positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of cancer screening in IIM patients.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV was downgraded by 2 levels because of possible issues in applicability regarding patient population in one of the studies (-1, bias due to indirectness); and a low number of included studies and patients with a low prevalence of malignancies (-1, imprecision).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the value of positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) examination in the detection of malignancies compared to conventional screening, in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM)?

P: Patients with IIM

I: 18F-FDG PET/CT examination

C: Conventional screening (usually consisting of physical examination, laboratory tests, thoracoabdominal/pelvic CT, tumor maker analysis, and in women gynaecological examination and mammography)

R: Histopathological examination/ biopsy

O: Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV)

Timing and setting: screening for malignancies occurring within the first 3 years after the diagnosis of IIM, in the hospital setting.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered sensitivity and NPV as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and specificity and PPV as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined minimal clinically important values as 80% or more for both sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV for the screening of malignancies in IIM patients.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2005 until the 4th of November 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 473 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- (a) study design (due to the type of question (diagnostic), not only systematic reviews, but also other comparative research (cohort studies, case-control studies), randomized controlled trials if fitting design;

- (b) Study population (patients with IIM);

- (c) index test (18F-FDG PET/CT examination);

- (d) comparator ((multimodal) conventional screening);

- (e) language (English)

- (f) publication date (between 2005 and November 2021)

Articles were screened based on title and abstract, which resulted in 15 articles. After reading the full text, two articles were eligible for inclusion. A table with reasons for exclusion is presented under the tab Methods.

Results

Two studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Kang EH, Lee SJ, Ascherman DP, Lee YJ, Lee EY, Lee EB, Song YW. Temporal relationship between cancer and myositis identifies two distinctive subgroups of cancers: impact on cancer risk and survival in patients with myositis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016 Sep;55(9):1631-41. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew215. Epub 2016 May 31. PMID: 27247435.

- Leatham H, Schadt C, Chisolm S, Fretwell D, Chung L, Callen JP, Fiorentino D. Evidence supports blind screening for internal malignancy in dermatomyositis: Data from 2 large US dermatology cohorts. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Jan;97(2):e9639. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009639. PMID: 29480875; PMCID: PMC5943873.

- Lilleker JB, Vencovsky J, Wang G, Wedderburn LR, Diederichsen LP, Schmidt J, Oakley P, Benveniste O, Danieli MG, Danko K, Thuy NTP, Vazquez-Del Mercado M, Andersson H, De Paepe B, deBleecker JL, Maurer B, McCann LJ, Pipitone N, McHugh N, Betteridge ZE, New P, Cooper RG, Ollier WE, Lamb JA, Krogh NS, Lundberg IE, Chinoy H; all EuroMyositis contributors. The EuroMyositis registry: an international collaborative tool to facilitate myositis research. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Jan;77(1):30-39. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211868. Epub 2017 Aug 30. PMID: 28855174; PMCID: PMC5754739.

- Maliha PG, Hudson M, Abikhzer G, Singerman J, Probst S. 18F-FDG PET/CT versus conventional investigations for cancer screening in autoimmune inflammatory myopathy in the era of novel myopathy classifications. Nucl Med Commun. 2019 Apr;40(4):377-382. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000981. PMID: 30664602.

- Morris P, Dare J. Juvenile dermatomyositis as a paraneoplastic phenomenon: an update. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010 Apr;32(3):189-91. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181bf29a2. PMID: 20057323.

- Oldroyd AGS, Allard AB, Callen JP, Chinoy H, Chung L, Fiorentino D, George MD, Gordon P, Kolstad K, Kurtzman DJB, Machado PM, McHugh NJ, Postolova A, Selva-O'Callaghan A, Schmidt J, Tansley S, Vleugels RA, Werth VP, Aggarwal R. A systematic review and meta-analysis to inform cancer screening guidelines in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Jun 18;60(6):2615-2628. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab166. Erratum in: Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Nov 3;60(11):5483. PMID: 33599244; PMCID: PMC8213426.

- Oldroyd AGS, Callen JP, Chinoy H, Chung L, Fiorentino D, Gordon P, Machado PM, McHugh N, Selva-O'Callaghan A, Schmidt J, Tansley SL, Vleugels RA, Werth VP; International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group Cancer Screening Expert Group; Aggarwal R. International Guideline for Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathy-Associated Cancer Screening: an International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) initiative. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2023 Dec;19(12):805-817. doi: 10.1038/s41584-023-01045-w. Epub 2023 Nov 9. PMID: 37945774.

- Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (RIVM). Inventarisatie van ontwikkelingen van PET-CT. Rapport 300080008/2011, door H. Bijwaard. 2011. Beschikbaar via: https://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/300080008.pdf

- Selva-O'Callaghan A, Grau JM, Gámez-Cenzano C, Vidaller-Palacín A, Martínez-Gómez X, Trallero-Araguás E, Andía-Navarro E, Vilardell-Tarrés M. Conventional cancer screening versus PET/CT in dermatomyositis/polymyositis. Am J Med. 2010 Jun;123(6):558-62. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.11.012. PMID: 20569766.

- Shelly S, Mielke MM, Mandrekar J, Milone M, Ernste FC, Naddaf E, Liewluck T. Epidemiology and Natural History of Inclusion Body Myositis: A 40-Year Population-Based Study. Neurology. 2021 May 25;96(21):e2653-e2661. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012004. Epub 2021 Apr 20. PMID: 33879596; PMCID: PMC8205447.

- Tiniakou E, Mammen AL. Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies and Malignancy: a Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017 Feb;52(1):20-33. doi: 10.1007/s12016-015-8511-x. PMID: 26429706.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Maliha, 2019 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort

Setting and country: Single centre, Canada

Funding and conflicts of interest: No conflict of interests, one author funded by Fonds de Recherche du Quebec-Santé (funding agency not involved in study) |

Inclusion criteria: (1) Having had a 18F-FDG PET/CT examination, (2) confirmed diagnosis of autoimmune inflammatory myopathy (AIM), (2) sufficient (not specified) follow up Between Apr 2005 and Feb 2018.

Exclusion criteria: (1) known malignancy before diagnosis of AIM, (2) cancer diagnosis before 18F-FDG-PET/CT scan

N= 63

Prevalence: 4.8%

Mean age ± SD: 54 ± 15

Sex: 21% M / 79% F

Other important characteristics: DM: 49%, OM 40%, PM 2%, IBM 2%, Orbital myositis 2%, unspecified myositis 6% |

Index test: 18F-FDG PET/CT scan on patient who had fasted for 6 hours, with barium sulfate oral contrast and 18F-FDG injected intravenously. From base of skull to upper thighs. Additional images if clinically indicated.

Comparator test: Conventional screening (physical and gynaecological examination, blood test, urine analysis, X-thorax, gastroscopy, colonoscopy, CT thorax/abdomen/pelvis, mammography, endovaginal ultrasound, serum tumor markers)

Cut-off point(s): Both index and comparator test were classified as TP, FP, TN or FN:

|

Reference test: Histopathological examination from biopsies + follow-up

Cut-off point(s): Not described.

|

Time between the index test and reference test: Index test before reference test.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N = 3 (4.5%)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Lack of sufficient follow-up. |

Outcome measures and effect size (including 95%C):

Sensitivity (95% CI) PET/CT: 0.0 (0.0 to 0.71) Conventional screening: 1.0 (0.29 to 1.0)

Specificity (95% CI) PET/CT: 0.85(0.73 to 0.93) Conventional screening: 0.64 (0.51 to 0.76)

PPV (95% CI) PET/CT: 0.0 (0.0 to 0.71) Conventional screening: 0.13 (0.0 to 0.26)

NPV (95% CI) PET/CT: 0.94 (0.88 to 1.00) Conventional screening: 1.00 (0.29 to 1.00) |

All PET/CT examinations from database were extracted, consequently patients with AIM were included. Indication for PET/CT unclear or patients with higher suspect of malignancies, therefore possibly issues in applicability concerning patient population. |

|

Selva – O‘Callaghan, 2010 |

Type of study: Prospective cohort

Setting and country: Multicentre academic, Spain

Funding and conflicts of interest: No conflict of interest. Grand from Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs (non-commercial). |

Inclusion criteria: (1) consecutive adult patients, (2) with recent PM or DM diagnosis based on Peter & Bohan criteria. Between Feb 2006 and Jan 2009.

Exclusion criteria: (1) previous cancer, (2) active infection that could produce misleading FDG-PET uptake (e.g. tuberculosis), (3) critical clinical situation making additional examinations dangerous (e.g. respiratory failure)

N=55

Prevalence: 16.36%

Median age (IQR): 57.5 (46.1 to 68.9)

Sex: 32.7% M / 67.3% F

Other important characteristics: DM 49, PM 6.

|

Index test: 18F-FDG PET/CT, 60-90 minutes after tracer injection, by experienced nuclear medicine physician blinded to conventional screening results. Usually within 6 months after diagnosis, and <4 weeks after conventional screening.

Cut-off point(s): 1 to 5 by visual interpretation (1 = definitely malignant, 2 = probably malignant, 3 = equivocal, 4 = probably benign, 5 = definitely benign) based on consensus of nuclear medicine physician and radiologist. Then split up as either positive (score 1 or 2), negative (score 4 or 5), or inconclusive (score 3). Inconclusive results are analysed as negative.

Comparator test: Conventional screening: complete physical examination, laboratory tests (blood count and serum chemistry panel), thoracoabdominal CT, tumor marker analysis (CA125, CA19.9, CEA, PSA); and in women mammography, gynaecolocic examination incl. ultrasonography

Cut-off point(s): Assessed as either positive or negative. |

Reference test: Histological evidence (biopsy or resection when appropriate. (except for 1 patient) + follow-up

Cut-off point(s): Not described.

|

Time between the index test and reference test: Reference test performed after index test

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N 6 (10.9%)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Administrative difficulties in performing PET/CT (n=4) and severe disease with progression to death (n=2) |

Outcome measures and effect size ( including 95%CI):

Sensitivity (95% CI) PET/CT: 0.67 (0.30 to 0.93) Conventional screening: 0.78 (0.40 to 0.97)

Specificity (95% CI) PET/CT: 0.98 (0.88 to 1.00) Conventional screening: 0.96 (0.85 to 0.99)

PPV (95% CI) PET/CT: 0.86 (0.42 to 1.00) Conventional screening: 0.78 (0.40 to 0.97)

NPV (95% CI) PET/CT: 0.94 (0.83 to 0.99) Conventional screening: 0.96 (0.85 to 0.99) |

|

Abbreviations: 18F-FDG PET/CT: (18F)-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography, AIM: autoimmune inflammatory myopathy, CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen, CI: confidence interval, CT: computed tomography, DM: dermatomyositis, FN: false negatives, FP: false positives, IBM: inclusion body myositis, NPV: negative predictive value, OM: overlap myositis, PM: polymyositis, PPV: positive predictive value, PSA: prostate-specific antigen, SD: standard deviation, TN: true negatives, TP: true positives

Risk of Bias table

|

Study reference |

Patient selection |

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Maliha, 2019 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Unclear: 3 patients with lack of sufficient follow-up excluded (seems appropriate)

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes, sort of. Difficult for different malignancies to provide one threshold value.

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? No, because reference standard is performed as indicated by index test result.

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? No; yet in the case a malignancy is not suspected, it is hard to determine from what material histological probes should be taken, so in this case it seems appropriate.

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes, histopathological examination (depending on which tissue is suspected of having been affected).

Were all patients included in the analysis? No, patients with lack of sufficient follow-up were excluded |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? Yes, all patients who have had PET/CT scan, and of those, the ones with myositis. As PET/CT is usually done on indication, this suggests that patients included in this study have higher likelihood of malignancy compared to “regular” myositis patients.

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW-INTERMEDIATE |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

||

|

Selva -O’Callaghan, 2010 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Unclear; 6 patients were excluded due to administrative difficulties in performing PET/CT (n=4) and severe disease with progression to death (n=2) |

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? No, because reference standard is performed as indicated by index test result.

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? No; yet in the case a malignancy is not suspected, it is hard to determine from what material histological probes should be taken, so in this case it seems appropriate.

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes, histopathological examination (depending on which tissue is suspected of having been affected).

Were all patients included in the analysis? No, patients in whom PET/CT could not be performed or who died were excluded. |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Alias A, Rodriguez EJ, Bateman HE, Sterrett AG, Valeriano-Marcet J. Rheumatology and oncology: an updated review of rheumatic manifestations of malignancy and anti-neoplastictherapy. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2012;70(2):109-14. PMID: 22892000. |

Wrong study design (scoping review) |

|

Amoura Z, Duhaut P, Huong DL, Wechsler B, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Francès C, Cacoub P, Papo T, Cormont S, Touitou Y, Grenier P, Valeyre D, Piette JC. Tumor antigen markers for the detection of solid cancers in inflammatory myopathies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005 May;14(5):1279-82. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0624. PMID: 15894686. |

Wrong intervention, absence of comparison |

|

Aussy A, Fréret M, Gallay L, Bessis D, Vincent T, Jullien D, Drouot L, Jouen F, Joly P, Marie I, Meyer A, Sibilia J, Bader-Meunier B, Hachulla E, Hamidou M, Huë S, Charuel JL, Fabien N, Viailly PJ, Allenbach Y, Benveniste O, Cordel N, Boyer O; OncoMyositis Study Group. The IgG2 Isotype of Anti-Transcription Intermediary Factor 1γ Autoantibodies Is a Biomarker of Cancer and Mortality in Adult Dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Aug;71(8):1360-1370. doi: 10.1002/art.40895. Epub 2019 Jul 8. PMID: 30896088. |

Wrong study design (prognostic design) |

|

Dutton K, Soden M. Malignancy screening in autoimmune myositis among Australian rheumatologists. Intern Med J. 2017 Dec;47(12):1367-1375. doi: 10.1111/imj.13556. PMID: 28742270. |

Wrong study design (questionnaire study) |

|

Field C, Goff BA. Dermatomyositis - key to diagnosing ovarian cancer, monitoring treatment and detecting recurrent disease: Case report. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017 Nov 28;23:1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2017.11.009. PMID: 29255784; PMCID: PMC5725216. |

Wrong study design (case report) |

|

Gkegkes ID, Minis EE, Iavazzo C. Dermatomyositis and colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Ir J Med Sci. 2018 Aug;187(3):615-620. doi: 10.1007/s11845-017-1716-7. Epub 2017 Nov 22. PMID: 29168152. |

Wrong intervention, wrong outcome (no reporting of diagnostic accuracy outcomes) |

|

Khanna U, Galimberti F, Li Y, Fernandez AP. Dermatomyositis and malignancy: should all patients with dermatomyositis undergo malignancy screening? Ann Transl Med. 2021 Mar;9(5):432. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-5215. PMID: 33842653; PMCID: PMC8033297. |

Wrong study design (non-systematic review) |

|

Kidambi TD, Schmajuk G, Gross AJ, Ostroff JW, Terdiman JP, Lee JK. Endoscopy is of low yield in the identification of gastrointestinal neoplasia in patients with dermatomyositis: A cross-sectional study. World J Gastroenterol. 2017 Jul 14;23(26):4788-4795. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i26.4788. PMID: 28765700; PMCID: PMC5514644. |

Wrong intervention |

|

Leatham H, Schadt C, Chisolm S, Fretwell D, Chung L, Callen JP, Fiorentino D. Evidence supports blind screening for internal malignancy in dermatomyositis: Data from 2 large US dermatology cohorts. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Jan;97(2):e9639. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009639. PMID: 29480875; PMCID: PMC5943873. |

Wrong outcome reporting (presence of screening in patients with cancer instead of presence of cancer in screened patients) |

|

Li Y, Zhou Y, Wang Q. Multiple values of 18F-FDG PET/CT in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Clin Rheumatol. 2017 Oct;36(10):2297-2305. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3794-3. Epub 2017 Aug 22. PMID: 28831580. |

Wrong study design (case-control) |

|

Lim CH, Tseng CW, Lin CT, Huang WN, Chen YH, Chen YM, Chen DY. The clinical application of tumor markers in the screening of malignancies and interstitial lung disease of dermatomyositis/polymyositis patients: A retrospective study. SAGE Open Med. 2018 Jun 18;6:2050312118781895. doi: 10.1177/2050312118781895. PMID: 29977547; PMCID: PMC6024348. |

Wrong intervention, absence of comparison |

|

Oldroyd AGS, Allard AB, Callen JP, Chinoy H, Chung L, Fiorentino D, George MD, Gordon P, Kolstad K, Kurtzman DJB, Machado PM, McHugh NJ, Postolova A, Selva-O'Callaghan A, Schmidt J, Tansley S, Vleugels RA, Werth VP, Aggarwal R. A systematic review and meta-analysis to inform cancer screening guidelines in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Jun 18;60(6):2615-2628. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab166. Erratum in: Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Nov 3;60(11):5483. PMID: 33599244; PMCID: PMC8213426. |

Wrong study design (narrative review) |

|

Vaidyanathan S, Pennington C, Ng CY, Poon FW, Han S. 18F-FDG PET-CT in the evaluation of paraneoplastic syndromes: experience at a regional oncology centre. Nucl Med Commun. 2012 Aug;33(8):872-80. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e3283550237. Erratum in: Nucl Med Commun. 2012 Sep;33(9):1006. PMID: 22669052. |

Wrong patient population (only 1 patient with myositis) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 07-02-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 07-02-2024

Algemene gegevens

The development of this guideline module was supported by the Knowledge Institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists (www.demedischspecialist.nl/ kennisinstituut) and was financed from the Quality Funds for Medical Specialists (SKMS). The financier has had no influence whatsoever on the content of the guideline module.

Samenstelling werkgroep

A multidisciplinary working group was set up in 2020 for the development of the guideline module, consisting of representatives of all relevant specialisms and patient organisations (see the Composition of the working group) involved in the care of patients with IIM/myositis.

Working group

- Dr. A.J. van der Kooi, neurologist, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie (chair)

- Dr. U.A. Badrising, neurologist, LUMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. C.G.J. Saris, neurologist, Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. S. Lassche, neurologist, Zuyderland MC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. J. Raaphorst, neurologist, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. J.E. Hoogendijk, neurologist, UMC Utrecht. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Drs. T.B.G. Olde Dubbelink, neurologist, Rijnstate, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Dr. I.L. Meek, rheumatologist, Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Reumatologie

- Dr. R.C. Padmos, rheumatologist, Erasmus MC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Reumatologie

- Prof. dr. E.M.G.J. de Jong, dermatologist, werkzaam in het Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Dermatologie en Venereologie

- Drs. W.R. Veldkamp, dermatologist, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Dermatologie en Venereologie

- Dr. J.M. van den Berg, pediatrician, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde

- Dr. M.H.A. Jansen, pediatrician, UMC Utrecht. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde

- Dr. A.C. van Groenestijn, rehabilitation physician, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging van Revalidatieartsen

- Dr. B. Küsters, pathologist, Radboudumc. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Pathologie

- Dr. V.A.S.H. Dalm, internist, Erasmus MC. Nederlandse Internisten Vereniging

- Drs. J.R. Miedema, pulmonologist, Erasmus MC. Nederlandse Vereniging van Artsen voor Longziekten en Tuberculose

- I. de Groot, patient representatieve. Spierziekten Nederland

Advisory board

- Prof. dr. E. Aronica, pathologist, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. External expert.

- Prof. dr. D. Hamann, Laboratory specialist medical immunology, UMC Utrecht. External expert.

- Drs. R.N.P.M. Rinkel, ENT physician, Amsterdam UMC, locatie VUmc. Vereniging voor Keel-Neus-Oorheelkunde en Heelkunde van het Hoofd-Halsgebied

- dr. A.S. Amin, cardiologist, werkzaam in werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Cardiologie

- dr. A. van Royen-Kerkhof, pediatrician, UMC Utrecht. External expert.

- dr. L.W.J. Baijens, ENT physician, Maastricht UMC+. External expert.

- Em. Prof. Dr. M. de Visser, neurologist, Amsterdam UMC. External expert.

Methodological support

- Drs. T. Lamberts, senior advisor, Knowledge institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists

- Drs. M. Griekspoor, advisor, Knowledge institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists

- Dr. M. M. J. van Rooijen, advisor, Knowledge institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists

Belangenverklaringen

The ‘Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling’ has been followed. All working group members have declared in writing whether they have had direct financial interests (attribution with a commercial company, personal financial interests, research funding) or indirect interests (personal relationships, reputation management) in the past three years. During the development or revision of a module, changes in interests are communicated to the chairperson. The declaration of interest is reconfirmed during the comment phase.

An overview of the interests of working group members and the opinion on how to deal with any interests can be found in the table below. The signed declarations of interest can be requested from the secretariat of the Knowledge Institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

van der Kooi |

Neuroloog, Amsterdam UMC |

|

Immediate studie (investigator initiated, IVIg behandeling bij therapie naive patienten). --> Financiering via Behring. Studie januari 2019 afgerond |

Geen restricties (middel bij advisory board is geen onderdeel van rcihtlijn) |

|

Miedema |

Longarts, Erasmus MC |

Geen. |

|

Geen restricties |

|

Meek |

Afdelingshoofd a.i. afdeling reumatische ziekten, Radboudumc |

Commissaris kwaliteit bestuur Nederlandse Vereniging voor Reumatologie (onkostenvergoeding) |

Medisch adviseur myositis werkgroep spierziekten Nederland |

Geen restricties |

|

Veldkamp |

AIOS dermatologie Radboudumc Nijmegen |

|

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Padmos |

Reumatoloog, Erasmus MC |

Docent Breederode Hogeschool (afdeling reumatologie EMC wordt hiervoor betaald) |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Dalm |

Internist-klinisch immunoloog Erasmus MC |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Olde Dubbelink |

Neuroloog in opleiding Canisius-Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis, Nijmegen |

Promotie onderzoek naar diagnostiek en outcome van het carpaletunnelsyndroom (onbetaald) |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

van Groenestijn |

Revalidatiearts AmsterdamUMC, locatie AMC |

Geen. |

Lokale onderzoeker voor de I'M FINE studie (multicentre, leiding door afdeling Revalidatie Amsterdam UMC, samen met UMC Utrecht, Sint Maartenskliniek, Klimmendaal en Merem. Evaluatie van geïndividualiseerd beweegprogramma o.b.v. combinatie van aerobe training en coaching bij mensen met neuromusculaire aandoeningen, NMA). Activiteiten: screening NMA-patiënten die willen participeren aan deze studie. Subsidie van het Prinses Beatrix Spierfonds. |

Geen restricties |

|

Lassche |

Neuroloog, Zuyderland Medisch Centrum, Heerlen en Sittard-Geleen |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

de Jong |

Dermatoloog, afdelingshoofd Dermatologie Radboudumc Nijmegen |

Geen. |

All funding is not personal but goes to the independent research fund of the department of dermatology of Radboud university medical centre Nijmegen, the Netherlands |

Geen restricties |

|

Hoogendijk |

Neuroloog Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht (0,4) Neuroloog Sionsberg, Dokkum (0,6) |

beide onbetaald |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Badrising |

Neuroloog Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum |

(U.A.Badrising Neuroloog b.v.: hoofdbestuurder; betreft een vrijwel slapende b.v. als overblijfsel van mijn eerdere praktijk in de maatschap neurologie Dirksland, Het van Weel-Bethesda Ziekenhuis) |

Medisch adviseur myositis werkgroep spierziekten Nederland |

Geen restricties |

|

van den Berg |

Kinderarts-reumatoloog/-immunoloog Emma kinderziekenhuis/ Amsterdam UMC |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

de Groot |

Patiënt vertegenwoordiger/ ervaringsdeskundige: voorzitter diagnosewerkgroep myositis bij Spierziekten Nederland in deze commissie patiënt(vertegenwoordiger) |

|

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Küsters |

Patholoog, Radboud UMC |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Saris |

Neuroloog/ klinisch neurofysioloog, Radboudumc |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties |

|

Raaphorst |

Neuroloog, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen. |

|

Restricties m.b.t. opstellen aanbevelingen IvIg behandeling. |

|

Jansen |

Kinderarts-immunoloog-reumatoloog, WKZ UMC Utrecht |

Docent bij Mijs-instituut (betaald) |

Onderzoek biomakers in juveniele dermatomyositis. Geen belang bij uitkomst richtlijn. |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Attention was paid to the patient's perspective by offering the Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland to take part in the working group. Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland has made use of this offer, the Dutch Artritis Society has waived it. In addition, an invitational conference was held to which the Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland, the Dutch Artritis Society nd Patiëntenfederatie Nederland were invited and the patient's perspective was discussed. The report of this meeting was discussed in the working group. The input obtained was included in the formulation of the clinical questions, the choice of outcome measures and the considerations. The draft guideline was also submitted for comment to the Vereniging Spierziekten Nederland, the Dutch Artritis Society and Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, and any comments submitted were reviewed and processed.

Qualitative estimate of possible financial consequences in the context of the Wkkgz

In accordance with the Healthcare Quality, Complaints and Disputes Act (Wet Kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen Zorg, Wkkgz), a qualitative estimate has been made for the guideline as to whether the recommendations may lead to substantial financial consequences. In conducting this assessment, guideline modules were tested in various domains (see the flowchart on the Guideline Database).

The qualitative estimate shows that there are probably no substantial financial consequences, see table below.

|

Module |

Estimate |

Explanation |

|

Module diagnostische waarde ziekteverschijnselen |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Optimale strategie aanvullende diagnostiek myositis |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Autoantibody testing in myositis |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Screening op maligniteiten |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Screening op comorbiditeiten |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Immunosuppressie en -modulatie bij IBM |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Treatment with Physical training |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Treatment of dysphagia in myositis |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Treatment of dysphagia in IBM |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Topical therapy |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Treatment of calcinosis |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

|

Module Organization of care |

No substantial financial consequences |

Outcome 1 No financial consequences. The recommendations are not widely applicable (<5,000 patients) and are therefore not expected to have any substantial financial consequences on collective expenditures. |

Werkwijze

Methods

AGREE

This guideline module has been drawn up in accordance with the requirements stated in the Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 report of the Advisory Committee on Guidelines of the Quality Council. This report is based on the AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Clinical questions

During the preparatory phase, the working group inventoried the bottlenecks in the care of patients with IIM. Bottlenecks were also put forward by the parties involved via an invitational conference. A report of this is included under related products.

Based on the results of the bottleneck analysis, the working group drew up and finalized draft basic questions.

Outcome measures

After formulating the search question associated with the clinical question, the working group inventoried which outcome measures are relevant to the patient, looking at both desired and undesired effects. A maximum of eight outcome measures were used. The working group rated these outcome measures according to their relative importance in decision-making regarding recommendations, as critical (critical to decision-making), important (but not critical), and unimportant. The working group also defined at least for the crucial outcome measures which differences they considered clinically (patient) relevant.

Methods used in the literature analyses

A detailed description of the literature search and selection strategy and the assessment of the risk-of-bias of the individual studies can be found under 'Search and selection' under Substantiation. The assessment of the strength of the scientific evidence is explained below.

Assessment of the level of scientific evidence

The strength of the scientific evidence was determined according to the GRADE method. GRADE stands for Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (see http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). The basic principles of the GRADE methodology are: naming and prioritizing the clinically (patient) relevant outcome measures, a systematic review per outcome measure, and an assessment of the strength of evidence per outcome measure based on the eight GRADE domains (downgrading domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias; domains for upgrading: dose-effect relationship, large effect, and residual plausible confounding).

GRADE distinguishes four grades for the quality of scientific evidence: high, fair, low and very low. These degrees refer to the degree of certainty that exists about the literature conclusion, in particular the degree of certainty that the literature conclusion adequately supports the recommendation (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

Definitie |

|

|

High |

|

|

Moderate |

|

|

Low |

|

|

Very low |

|

When assessing (grading) the strength of the scientific evidence in guidelines according to the GRADE methodology, limits for clinical decision-making play an important role (Hultcrantz, 2017). These are the limits that, if exceeded, would lead to an adjustment of the recommendation. To set limits for clinical decision-making, all relevant outcome measures and considerations should be considered. The boundaries for clinical decision-making are therefore not directly comparable with the minimal clinically important difference (MCID). Particularly in situations where an intervention has no significant drawbacks and the costs are relatively low, the threshold for clinical decision-making regarding the effectiveness of the intervention may lie at a lower value (closer to zero effect) than the MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Considerations

In addition to (the quality of) the scientific evidence, other aspects are also important in arriving at a recommendation and are taken into account, such as additional arguments from, for example, biomechanics or physiology, values and preferences of patients, costs (resource requirements), acceptability, feasibility and implementation. These aspects are systematically listed and assessed (weighted) under the heading 'Considerations' and may be (partly) based on expert opinion. A structured format based on the evidence-to-decision framework of the international GRADE Working Group was used (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). This evidence-to-decision framework is an integral part of the GRADE methodology.

Formulation of conclusions

The recommendations answer the clinical question and are based on the available scientific evidence, the most important considerations, and a weighting of the favorable and unfavorable effects of the relevant interventions. The strength of the scientific evidence and the weight assigned to the considerations by the working group together determine the strength of the recommendation. In accordance with the GRADE method, a low evidential value of conclusions in the systematic literature analysis does not preclude a strong recommendation a priori, and weak recommendations are also possible with a high evidential value (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). The strength of the recommendation is always determined by weighing all relevant arguments together. The working group has included with each recommendation how they arrived at the direction and strength of the recommendation.

The GRADE methodology distinguishes between strong and weak (or conditional) recommendations. The strength of a recommendation refers to the degree of certainty that the benefits of the intervention outweigh the harms (or vice versa) across the spectrum of patients targeted by the recommendation. The strength of a recommendation has clear implications for patients, practitioners and policy makers (see table below). A recommendation is not a dictate, even a strong recommendation based on high quality evidence (GRADE grading HIGH) will not always apply, under all possible circumstances and for each individual patient.

|

Implications of strong and weak recommendations for guideline users |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Strong recommendation |

Weak recommendations |

|

For patients |

Most patients would choose the recommended intervention or approach and only a small number would not. |

A significant proportion of patients would choose the recommended intervention or approach, but many patients would not. |

|

For practitioners |

Most patients should receive the recommended intervention or approach. |

There are several suitable interventions or approaches. The patient should be supported in choosing the intervention or approach that best reflects his or her values and preferences. |

|

For policy makers |

The recommended intervention or approach can be seen as standard policy. |

Policy-making requires extensive discussion involving many stakeholders. There is a greater likelihood of local policy differences. |

Organization of care

In the bottleneck analysis and in the development of the guideline module, explicit attention was paid to the organization of care: all aspects that are preconditions for providing care (such as coordination, communication, (financial) resources, manpower and infrastructure). Preconditions that are relevant for answering this specific initial question are mentioned in the considerations. More general, overarching or additional aspects of the organization of care are dealt with in the module Organization of care.

Commentary and authtorisation phase

The draft guideline module was submitted to the involved (scientific) associations and (patient) organizations for comment. The comments were collected and discussed with the working group. In response to the comments, the draft guideline module was modified and finalized by the working group. The final guideline module was submitted to the participating (scientific) associations and (patient) organizations for authorization and authorized or approved by them.

References

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, . GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekopbrengst

Search date: 4 November 2021

|

|

EMBASE |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SRs |

59 |

23 |

67 |

|

RCTs |

95 |

37 |

111 |

|

Observationele studies |

230 |

154 |

295 |

|

Totaal |

384 |

214 |

473 |

Zoekstrategie

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Embase

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medline (OVID)

|

1 exp Myositis/ or Dermatomyositis/ or myositi*.ti,ab,kf. or ((auto-immun* or autoimmun* or immunemediat* or immune mediat* or idiopathic inflammat*) adj3 myopath*).ti,ab,kf. or inmn.ti,ab,kf. or antisynthetase syndrome.ti,ab,kf. or dermatomyositi*.ti,ab,kf. or polymyositi*.ti,ab,kf. (27943) 2 exp Neoplasms/ or adenoma*.ti,ab,kf. or anticarcinogen*.ti,ab,kf. or blastoma*.ti,ab,kf. or cancer*.ti,ab,kf. or carcinogen*.ti,ab,kf. or carcinom*.ti,ab,kf. or carcinosarcoma*.ti,ab,kf. or chordoma*.ti,ab,kf. or germinoma*.ti,ab,kf. or gonadoblastoma*.ti,ab,kf. or hepatoblastoma*.ti,ab,kf. or (hodgkin* adj1 disease).ti,ab,kf. or leukemi*.ti,ab,kf. or lymphangioma*.ti,ab,kf. or lymphangiomyoma*.ti,ab,kf. or lymphangiosarcoma*.ti,ab,kf. or lymphom*.ti,ab,kf. or malignan*.ti,ab,kf. or melanom*.ti,ab,kf. or meningioma*.ti,ab,kf. or mesenchymoma*.ti,ab,kf. or mesonephroma*.ti,ab,kf. or metasta*.ti,ab,kf. or neoplas*.ti,ab,kf. or neuroma*.ti,ab,kf. or nsclc.ti,ab,kf. or oncogen*.ti,ab,kf. or oncolog*.ti,ab,kf. or paraneoplastic.ti,ab,kf. or plasmacytoma*.ti,ab,kf. or precancerous.ti,ab,kf. or sarcoma*.ti,ab,kf. or teratocarcinoma*.ti,ab,kf. or teratoma*.ti,ab,kf. or tumor*.ti,ab,kf. or tumour*.ti,ab,kf. (4839203) 3 exp Positron Emission Tomography Computed Tomography/ or exp X-Rays/ or exp Mammography/ or exp Ultrasonography/ or exp Gastroscopy/ or exp Colonoscopy/ or exp Biomarkers/ or (pet or tomograph* or mammograph* or echograph* or ultrasonograph* or gastroscop* or colonoscop* or gynecolo* or marker* or biomarker*).ti,ab,kf. (2709036) 4 1 and 2 and 3 (975) 5 limit 4 to ((english or dutch) and yr="2005-Current") (652) 6 5 not (comment/ or editorial/ or letter/ or ((exp animals/ or exp models, animal/) not humans/)) (615) 7 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (metaanaly* or meta-analy* or metanaly*).ti,ab,kf. or systematic review/ or cochrane.jw. or (prisma or prospero).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or scoping or umbrella or "structured literature") adj3 (review* or overview*)).ti,ab,kf. or (systemic* adj1 review*).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or literature or database* or data-base*) adj10 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((structured or comprehensive* or systemic*) adj3 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((literature adj3 review*) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ti,ab,kf. or (("data extraction" or "data source*") and "study selection").ti,ab,kf. or ("search strategy" and "selection criteria").ti,ab,kf. or ("data source*" and "data synthesis").ti,ab,kf. or (medline or pubmed or embase or cochrane).ab. or ((critical or rapid) adj2 (review* or overview* or synthes*)).ti. or (((critical* or rapid*) adj3 (review* or overview* or synthes*)) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ab. or (metasynthes* or meta-synthes*).ti,ab,kf.) not (comment/ or editorial/ or letter/ or ((exp animals/ or exp models, animal/) not humans/)) (528036) 8 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (2163730) 9 Epidemiologic studies/ or case control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or Case control.tw. or cohort.tw. or Cohort analy$.tw. or (Follow up adj (study or studies)).tw. or (observational adj (study or studies)).tw. or Longitudinal.tw. or Retrospective*.tw. or prospective*.tw. or consecutive*.tw. or Cross sectional.tw. or Cross-sectional studies/ or historically controlled study/ or interrupted time series analysis/ (Onder exp cohort studies vallen ook longitudinale, prospectieve en retrospectieve studies) (3936155) 10 6 and 7 (23) – SRs 11 (6 and 8) not 10 (37) - RCTs 12 (6 and 9) not (10 or 11) (154) - observationeel 13 10 or 11 or 12 (214)

|