Preoxygenatie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de optimale methode van preoxygenatie bij de vitaal bedreigde patiënt die geïntubeerd wordt?

Aanbeveling

Preoxygeneer de vitaal bedreigde patiënt die geïntubeerd moet worden met 100% zuurstof middels NIV, HFNO, masker-ballon of non-rebreathing mask gedurende tenminste 3 minuten.

Overweeg bij niet-coöperatieve patiënten delayed sequence inductie om preoxygenatie mogelijk te maken.

Gebruik NIV of HFNO voor preoxygenatie indien patiënt voor de beslissing tot intubatie reeds behandeld werd met een van deze vormen van ademhalingsondersteuning.

Gebruik bij voorkeur NIV voor preoxygenatie van patiënten met lage zuurstofsaturatie of hoge zuurstofbehoefte.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek gedaan naar verschillende methodes van pre- en peroxygenatie bij vitaal bedreigde patiënten die geïntubeerd worden buiten de operatiekamer. Peroxygenatie is beschreven in module Peroxygenatie. Omdat pre- en peroxygenatie vaak met elkaar verweven zijn, is in de analyse alleen gebruik gemaakt van publicaties waarin het effect van preoxygenatie kan worden onderscheiden. De gunstige en ongunstige effecten van preoxygenatie met non-invasieve beademing (NIV) en high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) werden met elkaar en met conventionele preoxygenatie met masker-ballon of non-rebreathing mask (NRM) vergeleken. Als cruciale uitkomstmaat werd incidentie van lage SpO2 meegenomen. Als belangrijke uitkomstmaten is gekeken naar de laagste SpO2 tijdens intubatie, hypotensie, hartstilstand en mortaliteit.

Bij de vergelijking tussen preoxygenatie met HFNO en conventionele preoxygenatie met masker-ballon of NRM leek er bij eerstgenoemde methode bij minder patiënten desaturatie op te treden tijdens intubatie (lage bewijskracht). Er is waarschijnlijk geen verschil in laagste SpO2 tussen de technieken (redelijke bewijskracht). De uitkomstmaten mortaliteit en hartstilstand konden geen richting geven aan de besluitvorming door de zeer lage bewijskracht. Hypotensie werd niet gerapporteerd.

Bij de vergelijking tussen preoxygenatie met NIV en conventionele preoxygenatie met masker-ballon of NRM leek bij eerstgenoemde methode bij minder patiënten desaturatie op te treden tijdens intubatie. Er is waarschijnlijk geen verschil in laagste SpO2 tussen de technieken (redelijke bewijskracht). De uitkomstmaat mortaliteit kon geen richting geven aan de besluitvorming door de zeer lage bewijskracht. Hypotensie en hartstilstand werden niet gerapporteerd.

Bij de vergelijking tussen preoxygenatie met NIV of HFNO leek bij eerstgenoemde methode bij minder patiënten desaturatie op te treden tijdens intubatie. Er is waarschijnlijk geen verschil in laagste SpO2 tussen de technieken (redelijke bewijskracht). De uitkomstmaten mortaliteit en hartstilstand konden geen richting geven aan de besluitvorming door de zeer lage bewijskracht. Hypotensie werd niet gerapporteerd. De bewijskracht van de cruciale uitkomstmaat is laag. Hier ligt een kennisvraag.

Bij vitaal bedreigde patiënten die geïntubeerd worden buiten de operatiekamer heeft, op basis van de literatuur, preoxygenatie met NIV de voorkeur boven preoxygenatie met HFNO en zijn deze beiden beter dan conventionele preoxygenatie met masker-ballon of NRM. Het betreft hier echter laaggradig bewijs dat uitsluitend gebaseerd is op een verschil in incidentie van desaturatie en niet op hardere eindpunten zoals opnameduur of mortaliteit. De werkgroep is daarom van mening dat het toepassen van preoxygenatie veel belangrijker is dan de techniek die daarvoor gebruikt wordt en dat andere overwegingen een rol mogen en soms dienen te spelen bij de keuze voor een bepaalde techniek.

Allereerst vereisen zowel NIV als HFNO specifieke apparatuur en materialen en ook expertise van de zorgverleners waardoor zij niet bij elke patiënt op elke locatie toegepast kunnen worden.

Daarnaast zal een deel van de patiënten voorafgaand aan de intubatie reeds behandeld worden met HFNO of NIV. Het ligt dan voor de hand om deze techniek met maximale zuurstofsuppletie te continueren bij wijze van preoxygenatie.

Patiënten met een insufficiënte ademhaling kunnen alleen optimaal gepreoxygeneerd worden middels beademing, hetgeen vraagt om NIV of masker-ballon beademing. Deze categorie patiënten is overigens in de meeste studies naar preoxygenatie technieken geëxcludeerd.

Wat ook een rol kan spelen bij de keuze voor een techniek is in hoeverre toepassing van positieve eind-expiratoire druk (PEEP) gewenst of gecontra-indiceerd is. Indien sprake is van respiratoir falen veroorzaakt door longoedeem of atelectase kan beter gepreoxygeneerd worden met PEEP. Dit leidt tot een hogere zuurstofsaturatie en tot een grotere functionele residuale longcapaciteit en daarmee tot een grotere zuurstofreserve in de longen. Indien de patiënt hypovolemisch of hypotensief is of pulmonale hypertensie heeft kan PEEP tot een toename van hemodynamische instabiliteit leiden en relatief gecontra-indiceerd zijn. NIV is de meest betrouwbare manier om PEEP toe te passen hetgeen ook in de voor deze module geselecteerde literatuur gezien wordt als de verklaring voor de betere resultaten van preoxygenatie met NIV.

Aan het eind van de ontwikkelingsfase van deze module verschenen de resultaten van de PREOXI studie (Gibbs, 2024). Deze studie vergeleek een combinatie van pre- en peroxygenatie met NIV enerzijds met preoxygenatie met een zuurstofmasker (NRM/BVM) anderzijds in 1301 vitaal bedreigde patiënten. De incidentie van desaturatie (SpO2 <85%) was in de NIV groep significant lager dan in de NRM/BVM groep (9,1% vs. 18,5%, p<0.001). Deze resultaten zijn niet meegenomen in de analyse maar zijn daarmee wel in lijn en geven een extra argument voor het gebruik van NIV.

Tot slot nog een opmerking over het preoxygeneren van geagiteerde, niet-coöperatieve patiënten. Het gaat hier slechts om een klein deel van de vitaal bedreigde patiënten die geïntubeerd worden. De literatuur suggereert om bij deze groep patiënten een 'delayed sequence inductie' toe te passen. Hiermee wordt bedoeld het geven van een vorm van sedatie t.b.v. de procedure ‘preoxygenatie’. Deze techniek moet bezien worden in het licht van optimale preoxygenatie bij niet-coöperatieve patiënten en staat los van de medicamenteuze inductie voor tracheale intubatie. Dit wordt beschreven in een cohort van 62 patiënten op de spoedeisende hulp en de intensive care (Weingart, 2015) en een RCT van 200 traumapatiënten (Bandyopadhyay, 2023). In beide studies worden de patiënten gesedeerd met op dissociatief effect getitreerde ketamine om preoxygenatie mogelijk te maken. Het voordeel van het wél goed kunnen preoxygeneren lijkt daarbij op te wegen tegen de potentiële risico's zoals aspiratie, ademdepressie en hemodynamische verslechtering.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het betreft hier de voorbereiding op een acute interventie in een levensbedreigende situatie. Het doel van preoxygenatie is het minimaliseren van de risico’s van de interventie, namelijk het luchtwegmanagement. De keuze voor de techniek wordt primair gebaseerd op wetenschappelijk bewijs, de beschikbaarheid van de materialen op de betreffende locatie en de ervaring van de zorgverleners. Indien er meerdere technieken geschikt en beschikbaar zijn, kan de techniek gekozen worden die de patiënt als minst belastend ervaart.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De geformuleerde adviezen zullen naar verwachting na implementatie leiden tot een uniformere manier van werken maar niet tot extra kosten ten aanzien van materialen of personele inzet.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Zowel NIV als HFNO vereisen specifieke apparatuur en materialen alsook expertise van de zorgverleners en kunnen daardoor niet bij elke patiënt en op elke locatie toegepast worden.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Op basis van de literatuur lijkt NIV de incidentie van desaturatie te verminderen ten opzichte van HFNO, en lijken beide beter dan beademing met masker-ballon bij vitaal bedreigde patiënten die geïntubeerd worden buiten de operatiekamer. De bewijskracht is echter laag.

De werkgroep is daarom van mening dat het toepassen van preoxygenatie veel belangrijker is dan de techniek die daarvoor gebruikt wordt. Het ligt voor de hand om bij patiënten die reeds met NIV of HFNO behandeld worden dit met 100% zuurstof te continueren bij wijze van preoxygenatie. Bij niet-coöperatieve patiënten kan sedatie overwogen worden om preoxygenatie mogelijk te maken.

NIV lijkt op basis van literatuur en pathofysiologie de beste preoxygenatietechniek. Deze techniek kan echter niet bij elke patiënt en op elke locatie toegepast worden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Preoxygenatie is een onderdeel van luchtwegmanagement. Hierbij wordt zuurstof toegediend met als doel om een zo groot mogelijk deel van het in de longen aanwezige stikstofgas (78% van de ons omringende lucht) te vervangen door zuurstof: denitrogenatie. De met zuurstof gevulde longen vormen dan een zuurstof reservoir van waaruit het bloed nog enige tijd geoxygeneerd kan worden nadat de patiënt is gestopt met ademen. Daardoor duurt het langer voordat de patiënt desatureert. Dit geeft tijd voor luchtwegmanagement en het starten van (effectieve) beademing. Deze veilige apneutijd kan bij gezonde volwassenen tot 8 minuten bedragen (Benumof, 1997), maar is bij vitaal bedreigde patiënt vrijwel altijd fors minder. Desalniettemin draagt goed preoxygeneren ook (of misschien wel juist) bij deze patiëntencategorie belangrijk bij aan de patiëntveiligheid bij luchtwegmanagement.

Over de vereiste duur van adequate preoxygenatie is weinig discussie. Voor adequate preoxygenatie (pulmonaal zuurstofgehalte >90%) is 3 minuten sufficiënte ademhaling (of beademing) met een FiO2 van 100% nodig (Benumof, 1999; Kang, 2010; Higgs, 2018).

Er is aanzienlijke praktijkvariatie in de techniek waarmee zuurstof toegediend wordt tijdens de preoxygenatiefase, variërend van masker-ballon en non-rebreathing masker (NRM) tot non-invasieve beademing (NIV) en high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO). Peroxygenatie technieken worden in de module Peroxygenatie uitgewerkt.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

HFNO versus NRM/BVM

Critical outcomes

|

Low GRADE |

Preoxygenation with high-flow nasal oxygen may reduce incidence of low SpO2 during intubation, when compared to preoxygenation with conventional oxygen therapy with non-rebreathing mask or bag-valve mask in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Fong, 2019; Chua, 2022. |

Important outcomes

|

Moderate GRADE |

Preoxygenation with high-flow nasal oxygen likely does not improve lowest SpO2 during intubation, when compared to preoxygenation with conventional oxygen therapy with non-rebreathing mask or bag-valve mask in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Fong, 2019; Chua, 2022. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of preoxygenation with high-flow nasal oxygen on hypotension, when compared with preoxygenation with conventional oxygen therapy with non-rebreathing mask or bag-valve mask in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of preoxygenation with high-flow nasal oxygen on cardiac arrest, when compared to preoxygenation with conventional oxygen therapy with non-rebreathing mask or bag-valve mask in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Fong, 2019; Chua, 2022. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of preoxygenation with high-flow nasal oxygen on mortality when compared to preoxygenation with conventional oxygen therapy with non-rebreathing mask or bag-valve mask in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Fong, 2019; Chua, 2022. |

NIV versus NRM/BVM

Critical outcomes

|

Low GRADE |

Preoxygenation with non-invasive ventilation may reduce incidence of low SpO2 during intubation, when compared to preoxygenation with conventional oxygen therapy with non-rebreathing mask or bag-valve mask in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Fong, 2019. |

Important outcomes

|

Moderate GRADE |

Preoxygenation with non-invasive ventilation likely does not improve lowest SpO2 during intubation, when compared to preoxygenation with conventional oxygen therapy with non-rebreathing mask or bag-valve mask in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Fong, 2019. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of preoxygenation with non-invasive ventilation on hypotension and cardiac arrest, when compared with preoxygenation with conventional oxygen therapy with non-rebreathing mask or bag-valve mask in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect preoxygenation with non-invasive ventilation on mortality when compared to preoxygenation with conventional oxygen therapy with non-rebreathing mask or bag-valve mask in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Source: Fong, 2019. |

NIV versus HFNO

Critical outcomes

|

Low GRADE |

Preoxygenation with non-invasive ventilation may reduce incidence of low SpO2 during intubation, when compared to preoxygenation with high-flow nasal oxygen in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Fong, 2019. |

Important outcomes

|

Moderate GRADE |

Preoxygenation with non-invasive ventilation likely does not improve lowest SpO2 during intubation, when compared to preoxygenation with high-flow nasal oxygen in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Fong, 2019. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of preoxygenation with non-invasive ventilation on hypotension, when compared with preoxygenation with high-flow nasal oxygen in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of preoxygenation with non-invasive ventilation on cardiac arrest, when compared to preoxygenation with high-flow nasal oxygen in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Fong, 2019. |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of preoxygenation with non-invasive ventilation on mortality when compared to preoxygenation with high-flow nasal oxygen in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room.

Sources: Fong, 2019. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Table 1 presents an overview of study characteristics of the included studies.

The systematic review and network meta-analysis by Fong (2019) summarizes the efficacy and safety of preoxygenation methods in adult patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. The authors searched PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library Central Register of Controlled Trials through April 2019 for randomized controlled trials (RCT) that studied the use of conventional oxygen therapy (COT), high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO), noninvasive ventilation (NIV), and HFNO and NIV as preoxygenation before intubation in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. The publication included seven RCTs (with 959 patients), six of which were relevant for the PICOs of the current analysis. The study by Jaber (2016) was excluded from the current analysis because it compared HFNO plus NIV with HFNO alone. Data in the current analysis were extracted from Fong (2019), unless stated otherwise. The primary outcome was the lowest SpO2 during the intubation procedure (from beginning of laryngoscopy to confirmation of endotracheal intubation by capnography). The secondary outcomes were proportion of patients with severe desaturation (SpO2 < 80%), intubation-related complications (aspiration or new infiltrate on post-intubation chest radiograph, hemodynamic instability, and cardiac arrest), and mortality. Risk of bias of the network meta-analysis was considered low. It is important to note that preoxygenation and peroxygenation were not strictly separated in all studies.

Table 1. Study characteristics

|

Study |

Setting |

Population |

Intervention |

Control |

PaO2 (mmHg) or PaO2/FiO2 ratio of the participants (mean ± SD or median [IQR]) |

|

Vourc’h, 2015 |

Six French ICUs (3 medical, 2 medical-surgical, one surgical) |

N = 119 Inclusion criteria: Adults (≥ 18 years) with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (RR > 30 bpm and FiO2 ≥ 50% to obtain > 90% oxygen saturation, and estimated PaO2/FiO2 < 300 mmHg) requiring endotracheal intubation in ICU after RSI Exclusion criteria: cardiac arrest, asphyxia, intubation without RSI, Cormack-Lehane grade 4 glottis |

HFNO 4-min preoxygenation with HFNO set to 60 L/min, of humidified oxygen flow (FiO2 100%); maintained in place throughout the endotracheal intubation |

NRM/BVM 4-min preoxygenation with high FiO2 facial mask (15 L/min O2 flow) |

PaO2/ FiO2: Facial mask, 115.7 ± 63 HFNO, 120.2 ± 55.7 |

|

Simon, 2016 |

Single center in Germany |

N = 40 Inclusion criteria: Respiratory failure with hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2 < 300 mmHg), indicated for endotracheal intubation, age ≥ 18 years Exclusion criteria: Difficult airway, nasopharyngeal obstruction or blockage |

HFNO 3-min preoxygenation using HFNO, oxygen flow 50 L/min, FiO2 1.0; left in place during the intubation procedure |

NRM/BVM 3-min preoxygenation using a BVM (adult size AMBU SPUR II disposable resuscitator with oxygen bag reservoir and without PEEP valve or pressure manometer), O2 10 L/min. No manual insufflation performed during apneic period. |

PaO2/ FiO2: BVM, 205 ± 59 HFNO, 200 ± 57 |

|

Guitton, 2019 |

Seven French ICU (4 medical, 2 medical-surgical, 1 surgical) |

N = 184 Inclusion criteria: Adults patients (age > 18) requiring intubation in the ICU, without severe hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2 < 200 mmHg) Exclusion criteria: Intubation without RSI (cardiac arrest), fiberoptic intubation, asphyxia, nasopharyngeal blockade, grade 4 glottis on Cormack-Lehane scale |

HFNO 4-min preoxygenation in a head-up position with HFNO (60 L/min flow of headed and humidified oxygen FiO2 1.0, large or medium nasal cannulae chosen according to patients’ nostril size) |

NRM/BVM 4-min preoxygenation in a head-up position with BVM (disposable self-inflating resuscitator with a reservoir bag, O2 set at 15 L/min) |

PaO2/ FiO2: BVM, 375 [276, 446] HFNO, 318 [242, 396] |

|

Chua, 2022 |

Two emergency departments in Singapore, (1 university hospital 1 general hospital) |

N=192 Inclusion criteria: patients aged ≥21 years requiring rapid sequence intubation due to any condition. Exclusion criteria: active “do-not-resuscitate” orders; crash, awake or delayed sequence intubations; requiring non-invasive positive pressure ventilation; cardiac arrest; suspicion or confirmed diagnosis of base of skull fractures or severe facial trauma that precluded placement of NC; pregnant women; and those incarcerated |

HFNO 60L/min of warm and humidified oxygen at 37°C and fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of more than 0.90 using the AIRVO 2 Humidifier with Integrated Flow Generator (Fisher & Paykel Healthcare Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand) during preoxygenation and apnoeic oxygenation phases. |

NRM/BVM usual care by preoxygenating using only NRM at flush rate, and then given at least 15L/min of non-humidified and nonheated oxygen from wall supply via NC for apnoeic oxygenation. Flush rate used for NRM preoxygenation reduces leak around the mask margins and is non-inferior to BVM, which is the other recommended modality. |

Not reported |

|

Baillard, 2006 |

Two medical surgical ICUs of 2 university hospitals in France |

N = 53 Inclusion criteria: Acute respiratory failure requiring intubation Hypoxemia (PaO2 < 100 mmHg with 10 L/min O2 mask Exclusion criteria: encephalopathy or coma, cardiac resuscitation, hyperkalemia (> 5.5 mEq/L) |

NIV 3-min preoxygenation with NIV (PSV delivered by an ICU ventilator through a face mask adjusted to obtain an expired tidal volume of 7–10 ml/kg, FiO2 100%, PEEP 5 cmH2O) |

NRM/BVM 3-min preoxygenation with a nonrebreather BVM driven by 15 L/min O2 Patient allowed to breathe spontaneously with occasional assistance |

PaO2: COT, 68 [60–79] NIV, 60 [57–89] |

|

Baillard, 2018 |

Six sites in France |

N = 201 Inclusion criteria: Adults patients (age > 18) with acute respiratory failure requiring intubation. Exclusion criteria: Encephalopathy or coma, cardiac resuscitation, decompensation of chronic respiratory failure |

NIV 3-min preoxygenation using NIV—pressure support mode delivered by an ICU ventilator through a face mask adjusted to obtain an expired tidal volume of 6–8 ml/kg, FiO2 1.0, PEEP 5 cmH2O |

NRM/BVM 3-min preoxygenation with non-rebreathing BVM with an oxygen reservoir driven by 15 L/min O2; patient allowed to breathe spontaneously with occasional assists |

PaO2/FiO2: BVM, 126 [95–207] HFNO, 132 [80–175] |

|

Frat, 2019 |

Twenty-eight ICUs in France |

N = 313 Inclusion criteria: Patients (age > 18) admitted to the ICU requiring intubation, had acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (RR > 25 bpm or signs of respiratory distress, PaO2/FiO2 < 300 mmHg regardless of oxygenation strategy) Exclusion criteria: Cardiac arrest, altered consciousness (GCS < 8) |

HFNO 3–5-min preoxygenation at 30° with HFNO with oxygen flow 60 L/min through a heated humidifier, FiO2 1.0. Clinicians performed a jaw thrust to maintain a patent upper airway, and continued high-flow oxygen therapy during laryngoscopy until endotracheal tube was placed into the trachea |

NIV 3–5-min preoxygenation at 30° with NIV—pressure support ventilation delivered via a face mask connected to an ICU ventilator, adjusted to obtain an expired tidal volume 6–8 ml/kg of predicted body weight with PEEP 5 cmH2O and FiO2 1.0 |

PaO2/FiO2: HFNO, 148 ± 70 NIV, 142 ± 65 |

|

BVM: bag-valve mask; HFNO: high flow nasal oxygen; ICU: intensive care unit; NIV: noninvasive ventilation; NRM: non-rebreathing mask |

|||||

Chua (2022) reported results of the Pre-AeRATE trial. This multicenter, open-label RCT investigated whether HFNO for preoxygenation and apneic oxygenation maintains higher oxygen saturation (SpO2) in patients during rapid sequence intubation in the emergency department compared to usual care. The study included 192 patients aged ≥21 years requiring rapid sequence intubation due to any condition and assigned 97 patients to HFNO and 95 to NRM. The intervention group using HFNO received 60L/min of warm and humidified oxygen at 37°C and fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of more than 0.90 using the AIRVO 2 Humidifier with Integrated Flow Generator during preoxygenation and apneic oxygenation phases. Control group was managed with usual care by preoxygenating using only NRM at flush rate, and then given at least 15L/min of non-humidified and non-heated oxygen from wall supply via NC for apneic oxygenation. The primary endpoint was lowest SpO2 during the first intubation attempt, defined as time taken from administration of paralytic agent until quantitative ETCO2 was detected post-intubation if successful, or until the start of the second attempt if failed. Main secondary outcomes were incidence of SpO2 falling below 90% and safe apnea time during intubation (duration of apnea where SpO2 remains ≥90% and censored at the time of successful intubation). Other secondary outcomes included number of intubation attempts, time (from induction) to successful intubation, peri-intubation AE, and various post-intubation clinical outcomes. Risk of bias of the study was considered low.

Results

1. HFNO versus NRM/BVM

Four studies (Chua, 2022; Guitton, 2019; Simon, 2016; Vourc’h, 2015) compared HFNO with conventional oxygen therapy. Data were extracted from Fong (2019), unless stated otherwise.

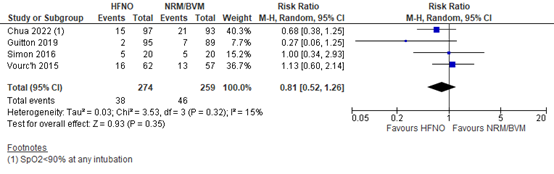

Incidence of low SpO2 during intubation (critical outcome)

Fong (2019) reported the incidence of SpO2 <80% during intubation. Chua (2022) reported SpO2 <90% at any intubation. Based on four studies, the pooled risk ratio (RR) of the incidence of low SpO2 during intubation between HFNO (N=274) and NRM/BVM (N=259) was 0.81 (95% CI 0.52 to 1.26), in favor of HFNO (Figure 1). The difference was considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Incidence of low SpO2 during intubation

Low SpO2 is <80% unless indicated otherwise. Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

Lowest SpO2 during intubation

Fong (2019) reported mean difference (MD) and standard deviation (SD) for lowest SpO2 during intubation. However, distribution of the data was highly skewed in the studies. Therefore, the data for this outcome measure were extracted from the original studies.

Guitton (2019) reported median and interquartile range (IQR) of 100% (97; 100) for the HFNO group versus 99% (95; 100) in the BVM group. Vourc’h (2015) reported a median (IQR) of 91.5% (80; 96) for the HFNO group versus 89.5% (81; 95) in the conventional oxygen therapy group. Simon (2018) reported a mean ± SD of 89 ± 18% in the HFNO group versus 86 ± 11% in the BVM group. In addition, Chua (2022) reported a median (IQR) of 100.0% (96.0; 100.0) in the HFNO group versus 100.0% (90.5; 100.0) in the NRM group. Overall, the differences were not considered clinically relevant.

Hypotension

Fong (2019) and Chua (2022) did not report incidence of hypotension.

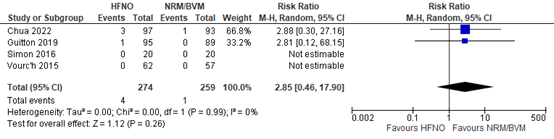

Cardiac arrest

Based on four studies, the pooled RR of cardiac arrest between HFNO (N=274) and NRM/BVM (N=259) was 2.85 (95% CI 0.46 to 17.90), in favor of NRM/BVM (Figure 2). The risk difference was 1%, with a 95% CI from -1% to 3%. Due to the very limited number of events, the estimation of the effect is very uncertain.

Figure 2. Cardiac arrest

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

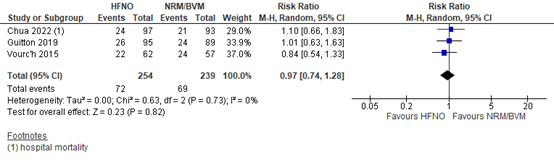

Mortality

Fong (2019) reported mortality at 28 days. Chua reported hospital mortality. Based on three studies, the pooled RR of mortality between HFNO (N=274) and NRM/BVM (N=259) was 0.97 (95% CI 0.74 to 1.28), in favor of HFNO (Figure 3). The difference was not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 3. Mortality at 28 days

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures was based on randomized controlled studies and therefore started at high.

For the outcome measure incidence of low SpO2 during intubation, the level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels to LOW because the confidence interval crossed both limits of clinical decision-making (imprecision, -2).

For the outcome measure lowest SpO2 during intubation, the level of evidence was downgraded by one level to MODERATE because the confidence interval crossed the limit of clinical decision-making (imprecision, -1).

For the outcome measure cardiac arrest, the level of evidence was downgraded by 3 levels to VERY LOW because the confidence interval was very wide, due to the limited number of events (imprecision, -3).

For the outcome measure mortality, the level of evidence was downgraded by 3 levels to VERY LOW because the confidence interval crossed both limits of clinical decision-making (imprecision, -3).

2. NIV versus NRM/BVM

Two studies (Baillard, 2006; Baillard, 2018) compared NIV with conventional oxygen therapy. Data were extracted from Fong (2019), unless stated otherwise.

Incidence of low SpO2 during intubation (critical outcome)

Baillard (2006) reported an incidence of SpO2 < 80% during intubation of 2/27 (7.4%) in the NIV group versus 12/26 (46.2%) in the NRM/BVM group. Baillard (2018) reported an incidence of 18/99 (18.2%) in the NIV group versus 28/102 (27.5%) in the NRM/BVM group. The RRs of 0.16 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.65) and 0.66 (95% CI 0.39 to 1.12), respectively, were considered clinically relevant in favor of NIV.

Lowest SpO2 during intubation

Fong (2019) reported mean difference (MD) and standard deviation (SD) for lowest SpO2 during intubation. However, distribution of the data was highly skewed in the studies. Therefore, the data for this outcome measure were extracted from the original studies.

Baillard (2006) reported mean ± SD lowest SpO2 of 93 ± 8% in the NIV group (N=27) versus 81 ± 5% in NRM/BVM group (N=26). Baillard (2018) reported 92% (84; 98) with NIV (N=99) versus 88% (79; 95) with NRM/BVM (N=102). The differences are not considered clinically relevant.

Hypotension

Fong (2019) did not report incidence of hypotension.

Cardiac arrest

Baillard (2006) and Baillard (2018) did not report cardiac arrest.

Mortality

Baillard (2006) reported an ICU mortality of 8/27 (29.6%) in the NIV group versus 13/26 (50%) in the NRM/BVM group. Baillard (2018) reported a 28-day mortality of 31/99 (31.3%) in the NIV group versus 38/102 (37.3%) in the NRM/BVM group. The RRs of 0.59 (95% CI 0.30 to 1.19) and 0.84 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.24), respectively, were considered clinically relevant in favor of NIV.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures was based on randomized controlled studies and therefore started at high.

For the outcome measure incidence of low SpO2 during intubation, the level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels to LOW because the confidence interval crossed both limits of clinical decision-making (imprecision, -2).

For the outcome measure lowest SpO2 during intubation, the level of evidence was downgraded by one level to MODERATE because the confidence interval crossed the limit of clinical decision-making (imprecision, -1).

For the outcome measure mortality, the level of evidence was downgraded by 3 levels to VERY LOW because the confidence intervals crossed both limits of clinical decision-making (imprecision, -3).

3. NIV versus HFNO

Fong (2019) found one publication (Frat, 2019) that compared NIV with HFNO.

Incidence of low SpO2 during intubation (critical outcome)

Incidence of SpO2 < 80% during intubation was 33/142 (23.2%) in the NIV group versus 47/171 (27.5%) in the HFNO group. The RR of 0.85 (95% CI 0.58 to 1.24) in favor of NIV was considered clinically relevant.

Lowest SpO2 during intubation

Lowest SpO2 during intubation was 87 ± 13% in the NIV group (N=142) versus 84 ± 16% in the HFNO group (N=171). The MD of 3.00 (95% CI -0.21 to 6.21) in favor of NIV was not considered clinically relevant.

Hypotension

Fong (2019) did not report incidence of hypotension.

Cardiac arrest

Incidence of cardiac arrest was 5/142 (3.5%) in the NIV group versus 1/171 (0.6%) in the HFNO group. The RR of 0.17 (95% CI 0.02 to 1.41) in favor of HFNO was considered clinically relevant.

Mortality

Frat (2019) reported a 28-day mortality of 53/142 (37.3%) in the NIV group versus 58/171 (33.9%) in the HFNO group. The RR of 1.10 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.48) in favor of HFNO was considered clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures was based on randomized controlled studies and therefore started at high.

For the outcome measures lowest SpO2 during intubation and incidence of low SpO2 during intubation, the level of evidence was downgraded by two levels to LOW because the confidence interval crossed both limits of clinical decision-making (imprecision, -2).

For the outcome measure hypotension, the level of evidence could not be determined due to a lack of data.

For the outcome measure cardiac arrest, the level of evidence was downgraded by 3 levels to VERY LOW because the confidence interval was extremely wide, due to the very limited number of events (imprecision, -3).

For the outcome measure mortality, the level of evidence was downgraded by 3 levels to VERY LOW because the confidence interval crossed both limits of clinical decision-making (imprecision, -2).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

1. What are the benefits and harms of preoxygenation with noninvasive ventilation (NIV) or high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) compared to conventional oxygen therapy with non-rebreathing mask (NRM) or bag-valve mask (BVM) in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room?

Pico 1

| P: | Critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room |

| I: | HFNO |

| C: | NRM/BVM |

| O: | Incidence of low SpO2, lowest SpO2 during intubation, hypotension, cardiac arrest, mortality |

Pico 2

| P: | Critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room |

| I: | NIV |

| C: | NRM/BVM |

| O: | Incidence of low SpO2, lowest SpO2 during intubation, hypotension, cardiac arrest, mortality |

Pico 3

| P: | Critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room |

| I: | HFNO |

| C: | NIV |

| O: |

Incidence of low SpO2, lowest SpO2 during intubation, hypotension, cardiac arrest, mortality |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered incidence of low SpO2 as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and lowest SpO2 during intubation, hypotension, cardiac arrest and mortality as important outcome measures for decision making.

The threshold for low SpO2 was not defined a priori but was based on the findings reported in literature.

The working group defined 5% as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for incidence of low SpO2, cardiac arrest and mortality (relative risk <0.95 or >1.05), and 10% for lowest SpO2 (mean difference). For hypotension, a relative difference of 25% between groups was considered clinically relevant.

Search and select (Methods)

On the 9th of May 2023, a systematic search was performed in the databases Embase.com and Ovid/Medline for systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials on different methods of preoxygenation. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The search resulted in 426 unique hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: randomized controlled trials or systematic reviews thereof, comparing different modalities of preoxygenation in critically ill patients intubated outside the operating room. Fourteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, twelve studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion in the Methods section), and two studies were included.

Results

Two studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Bandyopadhyay A, Kumar P, Jafra A, Thakur H, Yaddanapudi LN, Jain K. Peri-Intubation Hypoxia After Delayed Versus Rapid Sequence Intubation in Critically Injured Patients on Arrival to Trauma Triage: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesth Analg. 2023 May 1;136(5):913-919. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006171. Epub 2023 Apr 14. PMID: 37058727.

- Benumof JL, Dagg R, Benumof R. Critical hemoglobin desaturation will occur before return to an unparalyzed state following 1 mg/kg intravenous succinylcholine. Anesthesiology. 1997 Oct;87(4):979-82. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00034. PMID: 9357902.

- Benumof JL. Preoxygenation: best method for both efficacy and efficiency. Anesthesiology. 1999 Sep;91(3):603-5. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199909000-00006. PMID: 10485765.

- Chua MT, Ng WM, Lu Q, Low MJW, Punyadasa A, Cove ME, Yau YW, Khan FA, Kuan WS. Pre- and apnoeic high-flow oxygenation for rapid sequence intubation in the emergency department (the Pre-AeRATE trial): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2022 Mar;51(3):149-160. doi: 10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.2021407. PMID: 35373238.

- Gibbs KW, Semler MW, Driver BE, Seitz KP, Stempek SB, Taylor C, Resnick-Ault D, White HD, Gandotra S, Doerschug KC, Mohamed A, Prekker ME, Khan A, Gaillard JP, Andrea L, Aggarwal NR, Brainard JC, Barnett LH, Halliday SJ, Blinder V, Dagan A, Whitson MR, Schauer SG, Walker JE Jr, Barker AB, Palakshappa JA, Muhs A, Wozniak JM, Kramer PJ, Withers C, Ghamande SA, Russell DW, Schwartz A, Moskowitz A, Hansen SJ, Allada G, Goranson JK, Fein DG, Sottile PD, Kelly N, Alwood SM, Long MT, Malhotra R, Shapiro NI, Page DB, Long BJ, Thomas CB, Trent SA, Janz DR, Rice TW, Self WH, Bebarta VS, Lloyd BD, Rhoads J, Womack K, Imhoff B, Ginde AA, Casey JD; PREOXI Investigators and the Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group. Noninvasive Ventilation for Preoxygenation during Emergency Intubation. N Engl J Med. 2024 Jun 20;390(23):2165-2177. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2313680. Epub 2024 Jun 13. PMID: 38869091; PMCID: PMC11282951.

- Higgs A, McGrath BA, Goddard C, Rangasami J, Suntharalingam G, Gale R, Cook TM; Difficult Airway Society; Intensive Care Society; Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine; Royal College of Anaesthetists. Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. Br J Anaesth. 2018 Feb;120(2):323-352. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.10.021. Epub 2017 Nov 26. PMID: 29406182.

- Fong KM, Au SY, Ng GWY. Preoxygenation before intubation in adult patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care. 2019 Sep 18;23(1):319. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2596-1. PMID: 31533792; PMCID: PMC6751657.

- Kang H, Park HJ, Baek SK, Choi J, Park SJ. Effects of preoxygenation with the three minutes tidal volume breathing technique in the elderly. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010 Apr;58(4):369-73. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2010.58.4.369. Epub 2010 Apr 28. PMID: 20508794; PMCID: PMC2876858.

- Weingart SD, Trueger NS, Wong N, Scofi J, Singh N, Rudolph SS. Delayed sequence intubation: a prospective observational study. Ann Emerg Med. 2015 Apr;65(4):349-55. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.09.025. Epub 2014 Oct 23. PMID: 25447559.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: What are the benefits and harms of preoxygenation with bag-valve mask (with or without PEEP), noninvasive ventilation (with PEEP) and high-flow nasal oxygen compared to each other in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Fong, 2019

CRD42018085866 |

SR and network meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to April 2019

A: Vourc’h, 2015 B: Simon, 2016 C: Guitton, 2019

D: Baillard, 2006 E: Baillard, 2018

F: Frat, 2019

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: Single center, Hong Kong

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. |

Inclusion criteria SR: randomized controlled trials (RCT) of adult patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure investigating any form of preoxygenation devices during endotracheal intubation. Acute hypoxemic respiratory failure was defined by the individual authors in the included studies. Preoxygenation devices included COT via bag-valve mask or face mask, HFNO, or NIV. We defined preoxygenation as oxygen delivery during the period before induction of anesthesia, till initiation of laryngoscopy.

Exclusion criteria SR: We excluded studies focusing only on apneic oxygenation. The following were excluded: studies evaluating only the duration of preoxygenation, decision on ventilation or preoxygenation during anesthesia or interventional procedures or enrolling healthy volunteers or animals.

7 studies included, 6 used for current analysis.

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N A: 119 B: 40 C: 184

D: 53 E: 201

F: 313

Age: Not reported

Sex: Not reported

PaO2 (mmHg) or PaO2/ FiO2 ratio of the participants (mean ± SD or median [IQR]) A: PaO2/ FiO2: Facial mask, 115.7 ± 63 HFNO, 120.2 ± 55.7 B: PaO2/ FiO2: BVM, 205 ± 59 HFNO, 200 ± 57 C: PaO2/ FiO2: BVM, 375 [276, 446] HFNO, 318 [242, 396]

D: PaO2: COT, 68 [60–79] NIV, 60 [57–89] E: PaO2/FiO2: BVM, 126 [95–207] HFNO, 132 [80–175]

F: PaO2/FiO2: HFNO, 148 ± 70 NIV, 142 ± 65 |

HFNO versus BVM A: 4-min preoxygenation with HFNO set to 60 L/min, of humidified oxygen flow (FiO2 100%); maintained in place throughout the endotracheal intubation B: 3-min preoxygenation using HFNO, oxygen flow 50 L/min, FiO2 1.0; left in place during the intubation procedure C: 4-min preoxygenation in a head-up position with HFNO (60 L/min flow of headed and humidified oxygen FiO2 1.0, large or medium nasal cannulae chosen according to patients’ nostril size)

NIV versus BVM D: 3-min preoxygenation with NIV (PSV delivered by an ICU ventilator through a face mask adjusted to obtain an expired tidal volume of 7–10 ml/kg, FiO2 100%, PEEP 5 cmH2O) E: 3-min preoxygenation using NIV—pressure support mode delivered by an ICU ventilator through a face mask adjusted to obtain an expired tidal volume of 6–8 ml/kg, FiO2 1.0, PEEP 5 cmH2O

NIV versus HFNO F: 3–5-min preoxygenation at 30° with NIV—pressure support ventilation delivered via a face mask connected to an ICU ventilator, adjusted to obtain an expired tidal volume 6–8 ml/kg of predicted body weight with PEEP 5 cmH2O and FiO2 1.0

|

HFNO versus BVM A: 4-min preoxygenation with high FiO2 facial mask (15 L/min O2 flow) B: 3-min preoxygenation using a BVM (adult size AMBU SPUR II disposable resuscitator with oxygen bag reservoir and without PEEP valve or pressure manometer), O2 10 L/min. No manual insufflation performed during apneic period. C: 4-min preoxygenation in a head-up position with BVM (disposable self-inflating resuscitator with a reservoir bag, O2 set at 15 L/min)

NIV versus BVM D: 3-min preoxygenation with a nonrebreather bag-valve mask driven by 15 L/min O2 Patient allowed to breathe spontaneously with occasional assistance E: 3-min preoxygenation with non-rebreathing BVM with an oxygen reservoir driven by 15 L/min O2; patient allowed to breathe spontaneously with occasional assists

NIV versus HFNO F: 3–5-min preoxygenation at 30° with HFNO with oxygen flow 60 L/min through a heated humidifier, FiO2 1.0. Clinicians performed a jaw thrust to maintain a patent upper airway, and continued high-flow oxygen therapy during laryngoscopy until endotracheal tube was placed into the trachea |

End-point of follow-up: Not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported

|

Critical outcome measures Lowest SpO2 during intubation Mean ± SD

A: HFNO 86.2 ± 15.2%, N=62 COT 85.9 ± 12.9%, N=57 B: HFNO 89 ± 18%, N=20 COT 86 ± 11%, N=20 C: HFNO 97 ± 5%, N=95 COT 95 ± 12%, N=89

D: NIV 93 ± 8%, N=27 COT 81 ± 5%, N=26 E: NIV 91.33±10.53%, N=99 COT 87.33 ± 12.03%, N=102

F: NIV 87 ± 13%, N=142 HFNO 84 ± 16%, N=171

Incidence of SpO2 < 80% during intubation n (%) A: HFNO 16 (25.8) COT 13 (22.8) B: HFNO 5 (25.0) COT 5 (25.0) C: HFNO 2 (2.1) COT 7 (7.9)

D: NIV 2 (7.4) COT 12 (46.2) E: NIV 18 (18.2) COT 28 (27.5)

F: NIV 33 (23.2) HFNO 47 (27.5)

Duration of SpO2 < 80% Not reported

Important outcome measures Hypotension Not reported

Cardiac arrest A: HFNO 0, COT 0 B: HFNO 0, COT 0 C: HFNO 1, COT 0

D: NR E: NR

F: HFNO 5, NIV 1

Mortality n (%)

28d mortality A: HFNO 22 (35.5) COT 24 (42.1) B: NR C: HFNO 26 (27.4) COT 24 (27.0)

D: NIV 8 (29.6) COT 13 (50), ICU mortality E: NIV 31 (31.3) COT 38 (37.3), 28d mortality

28d mortality F: NIV 53 (37.3) HFNO 58 (33.9)

NR=not reported |

Risk of bias (high, some concerns or low): Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials

Author’s conclusions: In adult patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, NIV is a safe and probably the most effective preoxygenation method. Further research should be performed to evaluate the benefits of the combination strategy of NIV plus HFNO.

Abbreviations COT: Conventional oxygen therapy; NIV: Noninvasive ventilation; HFNC: High-flow nasal cannula |

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

Research question: What are the benefits and harms of preoxygenation with bag-valve mask (with or without PEEP), noninvasive ventilation (with PEEP) and high-flow nasal oxygen compared to each other in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room?

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Fong, 2019 |

Yes |

Yes |

No Excluded studies were not described. |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Unclear Not specified for included studies. |

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])

Research question: What are the benefits and harms of preoxygenation with bag-valve mask (with or without PEEP), noninvasive ventilation (with PEEP) and high-flow nasal oxygen compared to each other in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Chua, 2022

Pre-AeRATE trial

NCT 03396094 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Two-centre, Singapore

Funding and conflicts of interest: This study is funded by the Clinician Scientist Individual Research Grant, New Investigator Grant from National Medical Research Council, Singapore.

Dr Mui Teng Chua received the Clinician Scientist Individual Research Grant, New Investigator Grant from National Medical Research Council, Singapore for the conduct of this investigator-initiated trial. Dr Matthew Edward Cove reports consultancy fees from Baxter and Medtronic paid directly to the National University Hospital, Singapore. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare did not participate in the design of the study or the decision to submit this article for publication. |

Inclusion criteria: ED patients aged ≥21 years requiring RSI due to any condition.

Exclusion criteria: Active “do-not-resuscitate” orders; crash, awake or delayed sequence intubations; requiring non-invasive positive pressure ventilation; cardiac arrest; suspicion or confirmed diagnosis of base of skull fractures or severe facial trauma that precluded placement of NC; pregnant women; and those incarcerated.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 97 Control: 95

Important prognostic factors2: Age, mean (SD): I: 60.4 (15.4) C: 61.9 (14.7)

Sex: I: 60.8% M C: 69.9% M

Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 I: 23.4 (4.0) C: 24.5 (4.7)

Glasgow Coma Scale, median (Q1, Q3) I: 7 (6, 14) C: 10 (6, 14)

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

High-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO)

60L/min of warm and humidified oxygen at 37°C and fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of more than 0.90 using the AIRVO 2 Humidifier with Integrated Flow Generator (Fisher & Paykel Healthcare Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand) during preoxygenation and apnoeic oxygenation phases.

N=97 |

Non-rebreather mask (NRM)

usual care by preoxygenating using only NRM at flush rate, and then given at least 15L/min of non-humidified and nonheated oxygen from wall supply via NC for apnoeic oxygenation. Flush rate used for NRM preoxygenation reduces leak around the mask margins and is non-inferior to BVM, which is the other recommended modality

N=93 |

Length of follow-up: Hospital discharge

Loss-to-follow-up: none

Incomplete outcome data: N/A

|

Critical outcome measures Desaturation: lowest SpO2 Lowest SpO2 during first attempt, %, median (Q1, Q3) I: 100.0 (96.0, 100.0) C: 100.0 (91.0, 100.0) Median diff (95% CI) [P value] 0 (0–4.0) [0.138]

Lowest SpO2 during all intubation attempts, %, median (Q1, Q3) I: 100.0 (96.0, 100.0) C: 100.0 (90.5, 100.0) Median diff (95% CI) [P value] 0 (0–4.0) [0.072]

Desaturation: incidence of low SpO2 Incidence of SpO2 <90%, no. (%) at first attempt I: 15 (15.5) C: 21 (22.6) Adj RR (95% CI) [P value] 0.68 (0.37–1.25) [0.213]

no. (%) at any attempt I: 15 (15.5) C: 22 (23.7) Adj RR (95% CI) [P value] 0.65 (0.36–1.19) [0.156]

Duration of SpO2 < 80% Not reported

Important outcome measures Hypotension no. (%) I: 4 (4.3) C: 3 (3.1) Adj RR (95% CI) [P value] 1.42 (0.33, 6.18) [0.714]

Cardiac arrest no. (%) I: 3 (3.3) C: 1 (1.0) Adj RR (95% CI) [P value] 3.20 (0.34, 30.17) [0.356]

Mortality Mortality in ICU, no. (%) I: 14 (15.4) C: 11 (13.3) Adj RR (95% CI) [P value] 1.17 (0.56–2.42) [0.682]

Mortality on discharge, no. (%) I: 24 (25.8) C: 21 (23.9) Adj RR (95% CI) [P value] 1.08 (0.65–1.79) [0.770] |

Authors’ conclusions: We found that HFNO use for preoxygenation and apnoeic oxygenation, when compared to usual care, did not show improvement in median lowest SpO2 achieved during the first intubation attempt. However, such HFNO use may prolong safe apnoea time. Our study showed that patients without neurological indications for intubation were likely to desaturate faster, or have a more challenging intubation, and may benefit from the longer apnoea time that HFNO provides. |

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

Research question: What are the benefits and harms of preoxygenation with bag-valve mask (with or without PEEP), noninvasive ventilation (with PEEP) and high-flow nasal oxygen compared to each other in critically ill patients who are intubated outside the operating room?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded? Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Chua, 2022 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Subjects were randomised at 1:1 ratio into intervention and control groups, stratified by study site, with variable blocks of 4 and 6 via a web-based randomisation service generated by an independent statistician. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Allocation concealment was maintained until completion of randomisation. Clinicians in the admitting ICUs were blinded to the study allocation. |

Definitely no

Reason: Blinding of the ED team and patient was not possible due to the intervention. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Probably yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW

Relevant outcome measures are not likely affected by lack of blinding. |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Baillard C, Prat G, Jung B, Futier E, Lefrant JY, Vincent F, Hamdi A, Vicaut E, Jaber S. Effect of preoxygenation using non-invasive ventilation before intubation on subsequent organ failures in hypoxaemic patients: a randomised clinical trial. Br J Anaesth. 2018 Feb;120(2):361-367. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.11.067. Epub 2017 Nov 23. PMID: 29406184. |

data extracted from SR Fong |

|

Baillard C, Fosse JP, Sebbane M, Chanques G, Vincent F, Courouble P, Cohen Y, Eledjam JJ, Adnet F, Jaber S. Noninvasive ventilation improves preoxygenation before intubation of hypoxic patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006 Jul 15;174(2):171-7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1507OC. Epub 2006 Apr 20. PMID: 16627862. |

data extracted from SR Fong |

|

Cabrini L, Landoni G, Baiardo Redaelli M, Saleh O, Votta CD, Fominskiy E, Putzu A, Snak de Souza CD, Antonelli M, Bellomo R, Pelosi P, Zangrillo A. Tracheal intubation in critically ill patients: a comprehensive systematic review of randomized trials. Crit Care. 2018 Jan 20;22(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1927-3. Erratum in: Crit Care. 2019 Oct 21;23(1):325. PMID: 29351759; PMCID: PMC5775615. |

More recent SR used |

|

Chaudhuri D, Granton D, Wang DX, Einav S, Helviz Y, Mauri T, Ricard JD, Mancebo J, Frat JP, Jog S, Hernandez G, Maggiore SM, Hodgson C, Jaber S, Brochard L, Burns KEA, Rochwerg B. Moderate Certainty Evidence Suggests the Use of High-Flow Nasal Cannula Does Not Decrease Hypoxia When Compared With Conventional Oxygen Therapy in the Peri-Intubation Period: Results of a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 2020 Apr;48(4):571-578. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004217. PMID: 32205604. |

More recent SR used |

|

Frat JP, Ricard JD, Quenot JP, Pichon N, Demoule A, Forel JM, Mira JP, Coudroy R, Berquier G, Voisin B, Colin G, Pons B, Danin PE, Devaquet J, Prat G, Clere-Jehl R, Petitpas F, Vivier E, Razazi K, Nay MA, Souday V, Dellamonica J, Argaud L, Ehrmann S, Gibelin A, Girault C, Andreu P, Vignon P, Dangers L, Ragot S, Thille AW; FLORALI-2 study group; REVA network. Non-invasive ventilation versus high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy with apnoeic oxygenation for preoxygenation before intubation of patients with acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure: a randomised, multicentre, open-label trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Apr;7(4):303-312. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30048-7. Epub 2019 Mar 18. PMID: 30898520. |

data extracted from SR Fong |

|

Guitton C, Ehrmann S, Volteau C, Colin G, Maamar A, Jean-Michel V, Mahe PJ, Landais M, Brule N, Bretonnière C, Zambon O, Vourc'h M. Nasal high-flow preoxygenation for endotracheal intubation in the critically ill patient: a randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2019 Apr;45(4):447-458. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05529-w. Epub 2019 Jan 21. PMID: 30666367. |

data extracted from SR Fong |

|

Jaber S, Monnin M, Girard M, Conseil M, Cisse M, Carr J, Mahul M, Delay JM, Belafia F, Chanques G, Molinari N, De Jong A. Apnoeic oxygenation via high-flow nasal cannula oxygen combined with non-invasive ventilation preoxygenation for intubation in hypoxaemic patients in the intensive care unit: the single-centre, blinded, randomised controlled OPTINIV trial. Intensive Care Med. 2016 Dec;42(12):1877-1887. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4588-9. Epub 2016 Oct 11. PMID: 27730283. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Li Y, Yang J. Comparison of Transnasal Humidified Rapid-Insufflation Ventilatory Exchange and Facemasks in Preoxygenation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2022 Jul 13;2022:9858820. doi: 10.1155/2022/9858820. PMID: 35872871; PMCID: PMC9300319. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Rodriguez M, Ragot S, Coudroy R, Quenot JP, Vignon P, Forel JM, Demoule A, Mira JP, Ricard JD, Nseir S, Colin G, Pons B, Danin PE, Devaquet J, Prat G, Merdji H, Petitpas F, Vivier E, Mekontso-Dessap A, Nay MA, Asfar P, Dellamonica J, Argaud L, Ehrmann S, Fartoukh M, Girault C, Robert R, Thille AW, Frat JP; REVA Network. Noninvasive ventilation vs. high-flow nasal cannula oxygen for preoxygenation before intubation in patients with obesity: a post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intensive Care. 2021 Jul 22;11(1):114. doi: 10.1186/s13613-021-00892-8. PMID: 34292408; PMCID: PMC8295638. |

Wrong study design |

|

Russotto V, Cortegiani A, Raineri SM, Gregoretti C, Giarratano A. Respiratory support techniques to avoid desaturation in critically ill patients requiring endotracheal intubation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care. 2017 Oct;41:98-106. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.05.003. Epub 2017 May 8. PMID: 28505486. |

More recent SR used |

|

Simon M, Wachs C, Braune S, de Heer G, Frings D, Kluge S. High-Flow Nasal Cannula Versus Bag-Valve-Mask for Preoxygenation Before Intubation in Subjects With Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure. Respir Care. 2016 Sep;61(9):1160-7. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04413. Epub 2016 Jun 7. PMID: 27274092. |

data extracted from SR Fong |

|

Vourc'h M, Asfar P, Volteau C, Bachoumas K, Clavieras N, Egreteau PY, Asehnoune K, Mercat A, Reignier J, Jaber S, Prat G, Roquilly A, Brule N, Villers D, Bretonniere C, Guitton C. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen during endotracheal intubation in hypoxemic patients: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2015 Sep;41(9):1538-48. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3796-z. Epub 2015 Apr 14. PMID: 25869405. |

data extracted from SR Fong |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 24-02-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 23-02-2025

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor vitaal bedreigde patiënten die geïntubeerd worden buiten de OK.

Werkgroep

Dr. J.A.M. (Joost) Labout (voorzitter tot september 2023), intensivist, NVIC

Drs. J.H.J.M. (John) Meertens (interim-voorzitter), intensivist, NVIC

Drs. P. (Peter) Dieperink (interim-voorzitter), intensivist, NVIC

Drs. M.E. (Mengalvio) Sleeswijk (interim-voorzitter), intensivist, NVIC

Dr. F.O. (Fabian) Kooij, anesthesioloog/MMT-arts, NVA

Drs. Y.A.M. (Yvette) Kuijpers, anesthesioloog-intensivist, NVA

Drs. C. (Caspar) Müller, anesthesioloog/MMT-arts, NVA

Drs. M.E. (Mark) Seubert, internist-intensivist, NIV

Drs. S.J. (Sjieuwke) Derksen, internist-intensivist, NIV

Dr. R.M. (Rogier) Determann, internist-intensivist, NIV

Drs. H.J. (Harry) Achterberg, anesthesioloog-SEH-arts, NVSHA

Drs. M.A.E.A. (Marianne) Brackel, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, FCIC/IC Connect

Klankbordgroep

Dr. C.L. (Christiaan) Meuwese, cardioloog-intensivist, NVVC

Drs. J.T. (Jeroen) Kraak, KNO-arts, NVKNO

Drs. H.R. (Harry) Naber, anesthesioloog, NVA

Drs. H. (Huub) Grispen, anesthesiemedewerker, NVAM

Met ondersteuning van

dr. M.S. Ruiter, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

drs. I. van Dijk, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Caspar Müller |

Anesthesioloog/MMT-arts ErasmusMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Fabian Kooij |

Anesthesioloog/MMT-arts, Amsterdam UMC |

Chair of the Board, European Trauma Course Organisation |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Harry Achterberg |

SEH-arts, Isala Klinieken, fulltime - 40u/w (~111%) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

John Meertens |

Intensivist-anesthesioloog, Intensive Care Volwassenen, UMC Groningen |

Secretaris Commissie Luchtwegmanagement, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Intensive Care |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Joost Labout |

Intensivist |

Redacteur A & I |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Marianne Brackel |

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger Stichting FCIC en patiëntenorganisatie IC Connect |

Geen |

Voormalig voorzitter IC Connect |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mark Seubert |

Internist-intensivist, |

Waarnemend internist en intensivist |

Lid Sectie IC van de NIV |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mengalvio Sleeswijk |

Internist-intensivist, Flevoziekenhuis |

Medisch Manager ambulancedienst regio Flevoland Gooi en Vecht / TMI Voorzitter Commissie Luchtwegmanagement, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Intensive Care |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Peter Dieperink |

Intensivist-anesthesioloog, Intensive Care Volwassenen, UMC Groningen |

Lid Commissie Luchtwegmanagement, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Intensive Care |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Rogier Determann |

Intensivist, OLVG, Amsterdam |

Docent Amstelacademie en Expertcollege |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Sjieuwke Derksen |

Intensivist - MCL |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Yvette Kuijpers |

Anesthesioloog-intensivist, CZE en MUMC + |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Klankbordgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Christiaan Meuwese |

Cardioloog intensivist, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Section editor Netherlands Journal of Critical Care (onbetaald) |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: - REMAP ECMO (Hartstichting) - PRECISE ECLS (Fonds SGS) |

Geen restricties. |

|

Jeroen Kraak |

KNO-arts & Hoofd-halschirurgie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Huub Grispen |

Anesthesiemedewerker Zuyderland MC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

|

Harry Naber |

Anesthesioloog MSB Isala |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van FCIC/IC Connect voor de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie en deelname aan de werkgroep. Het verslag hiervan [zie aanverwante producten] is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. Ter onderbouwing van de module Aanwezigheid van naaste heeft IC Connect een achterbanraadpleging uitgevoerd. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan FCIC/IC Connect en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijnmodule is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd om te beoordelen of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Preoxygenatie

|

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor vitaal bedreigde patiënten die geïntubeerd worden buiten de OK. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door verschillende stakeholders via een schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Literature search strategy

|

Cluster/richtlijn: Luchtwegmanagement bij de vitaal bedreigde patiënt buiten de OK-setting |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag/modules: Wat is de optimale methode van pre-oxygenatie bij de vitaal bedreigde patiënt die geïntubeerd wordt? |

|

|