Voorkomen van postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI’s) in de operatiekamer

Uitgangsvraag

Van welk luchtbehandelingsysteem moet een operatiekamer voorzien zijn om postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI’s) zo veel mogelijk te voorkomen?

Aanbeveling

Om postoperatieve wondinfecties zoveel mogelijk te voorkomen is een operatiekamer klasse 1 of 2 voorzien van een luchtbehandelingsysteem dat (ongeacht het type luchtinblaassysteem) tenminste voldoet aan de minimale criteria genoemd in de module 'Criteria voor luchtkwaliteit in de operatiekamer'.

Voor electieve grote gewrichtsvervangende operaties (knie, heup, schouder) heeft de Nederlandse Orthopedische Vereniging de voorkeur voor het voortzetten van de bestaande praktijk om te opereren in een operatiekamer die voldoet aan de criteria van een operatiekamer klasse 1+ (module Criteria voor luchtkwaliteit in de operatiekamer).

Overwegingen

Kwaliteit van bewijs

De algehele kwaliteit van het bewijs is (zeer) laag vanwege het observationele karakter van de studies, de aanwezigheid van statistische heterogeniteit en de onzekerheid van de extrapoleerbaarheid van de studieresultaten naar de Nederlandse situatie.

Waarden en voorkeuren

Niet van toepassing, omdat de aanbevelingen niet op het niveau van de individuele patiënt zijn.

Kosten en middelen

Bij de kosten van luchtbehandelingsystemen wordt onderscheid gemaakt in operationele kosten en investeringskosten. Operationele kosten zijn de kosten om een luchtbehandelingsysteem operationeel te houden. Energiekosten en personeelskosten voor controle en onderhoud zijn hierbij de grootste kostenposten. In de WIP-richtlijn ‘Luchtbehandeling in operatiekamer en opdekruimte in operatieafdeling klasse 1’ uit 2014 concludeerde de expertgroep dat op basis van het beschikbare bewijs geen uitspraak kan worden gedaan over de kosten van een mengend ten opzichte van een verticaal UDF systeem. Ook de huidige werkgroep kan niet inschatten of er een verschil is in operationele kosten tussen het gebruik van een UDF en een mengend system, omdat de grootte van deze kostenposten afhangt van veel verschillende lokale factoren. Hetzelfde geldt ook voor de schatting van de investeringskosten.

Concluderend: op basis van het beschikbare bewijs kan de werkgroep geen uitspraak doen over de kosten van een mengend luchtbehandelingssysteem ten opzichte van andere luchtbehandelingsystemen.

Duurzaamheid

Van de twee meest toegepaste luchtinblaassystemen, mengend en verdringend, lijken er op het gebied van duurzaamheid voordelen voor gebruik van een mengend luchtinblaassysteem. Exacte gegevens hierover kunnen niet worden gegeven omdat de milieubelasting van meer factoren dan alleen het type luchtinblaassysteem afhangt. Wel leidt gebruik van een mengend systeem in de regel tot minder energieverbruik omdat de hoeveelheid ingeblazen lucht lager is.

Professioneel perspectief

Het luchtbehandelingsysteem kan niet los worden gezien van het gehele pakket aan maatregelen gericht op het voorkómen van POWI, zoals strenge naleving van werkafspraken, kledingvoorschriften, deurbeleid, juiste plaatsing operatielampen en andere apparatuur, gedisciplineerd gedrag op de operatiekamer en infectieregistratie en monitoring.

De luchtbehandelingsystemen dienen volgens vastgelegde criteria (zie de module 'Criteria voor luchtkwaliteit in de operatiekamer') periodiek gecontroleerd en onderhouden te worden om de kwaliteit te waarborgen. Dit wordt lokaal vastgelegd in een luchtbeheersplan (zie de module 'Luchtbeheersplan in de operatiekamer').

Algemene chirurgische ingrepen

Er is onvoldoende bewijs om een specifiek luchtbehandelingsysteem aan te bevelen.

Orthopedische implantaatchirurgie

Voor orthopedische implantaatchirurgie zijn in de onderzochte literatuur geen aanwijzingen gevonden dat het plaatsen van een prothese in een operatiekamer voorzien van een mengend systeem geassocieerd is met meer diepe postoperatieve wondinfecties dan wanneer een prothese geplaatst wordt in een operatiekamer voorzien van een UDF. De kwaliteit van bewijs ten faveure van een mengend of een verdringend luchtinblaassysteem ter preventie van POWI’s is (zeer) laag. Protheseregisterstudies lijken niet altijd betrouwbaar als databron voor prothese-infecties. De studie van Hooper (2011) laat bijvoorbeeld 0,09% infecties zien, terwijl wereldwijd minimaal 1% gezien wordt. Daarnaast blijkt het rapporteren door chirurgen van welk luchtinblaassysteem aanwezig is op de OK ook niet altijd betrouwbaar (gemiddeld in 12% van de totale heupvervangingen verkeerd gerapporteerd) (Langvatn 2019). In geval van infecties van implantaten, zoals bijvoorbeeld knie- en heupprotheses, zijn de consequenties van een POWI groot voor de patiënt en gaan POWI’s gepaard met hoge kosten. Het kan zijn dat een prothese verwijderd moet worden, lange ziekenhuisopnames nodig zijn en/of langdurige antibioticatherapie gegeven moet worden. POWI’s kunnen zelfs leiden tot weefseldestructie, amputatie en mortaliteit. De bewijskracht van de studies gebaseerd op de uitkomstmaat POWI is (zeer) laag. Derhalve wordt gesuggereerd dat het zinvol kan zijn in geval van implantaten te kijken naar een afgeleide uitkomstmaat als contaminatie van het wondgebied tijdens operaties. Theoretisch biedt een verdringend systeem bij goed gebruik hier voordelen. In de praktijk zijn er echter tijdens de operatie verstorende factoren aanwezig die dit theoretische voordeel zouden kunnen verminderen.

Voor electieve grote gewrichtsvervangende operaties (knie, heup, schouder) heeft de Nederlandse Orthopedische Vereniging de voorkeur voor het voortzetten van de bestaande praktijk om te opereren in een operatiekamer die voldoet aan de criteria van een operatiekamer met ultraschone lucht - klasse 1+ (zie module Criteria voor luchtkwaliteit in de operatiekamer), conform NICE (2020).

Er is geen literatuur gevonden voor andere implantaatchirurgie, zoals voor ingrepen in de urologie, plastische chirurgie of thoraxchirurgie.

Aanbevelingen ten aanzien van luchtbehandelingsysteem in internationale richtlijnen

Ook in de internationale richtlijnen WHO (2016), CDC (2017), NICE (2020) wordt geconstateerd dat het onderzoek op dit gebied ernstige tekortkomingen heeft en dat deze lage tot zeer lage bewijskracht een keuze voor het uitrusten van een operatiekamer met een UDF of een mengend systeem niet ondersteunt. Enkele voorbeelden van dergelijke aanbevelingen zijn te vinden in de bijlagen. Technische richtlijnen en wetenschappelijke onderzoeken naar luchtbehandelingsystemen zijn niet in het literatuuronderzoek betrokken.

Aanvaardbaarheid van de aanbeveling

In de aanbeveling wordt geen voorkeur uitgesproken voor een bepaald luchtinblaassysteem vanwege het ontbreken van overtuigend wetenschappelijk bewijs voor het ene of het andere luchtinblaassysteem. Verder zijn momenteel nieuwe luchtinblaassystemen verkrijgbaar die niet exact onder een van deze beide typen systeem kunnen worden geschaard. Derhalve is er voor gekozen dat ongeacht het type luchtinblaassysteem gebruik dient te worden gemaakt van een luchtbehandelingssysteem waarbij de luchtkwaliteit minimaal voldoet aan de criteria genoemd in de module 'Criteria voor luchtkwaliteit in de operatiekamer'.

Haalbaarheid van de te implementeren aanbeveling

De aanbeveling is haalbaar omdat deze aansluit op de huidige praktijk. Er wordt niet voorgeschreven dat er één bepaald luchtinblaassysteem moet zijn.

Kennishiaat

Er is geen gerandomiseerd onderzoek waarin het effect van de verschillende luchtbehandelingsystemen (inclusief systeemkarakteristieken) op postoperatieve wondinfecties vergeleken is ongeacht het type van de ingreep. Meer en vooral kwalitatief beter onderzoek naar het effect van verschillende luchtbehandelingsystemen op postoperatieve wondinfecties is dringend gewenst.

Rationale van de aanbeveling

Leidend bij het opstellen van de aanbevelingen was het feit dat in de literatuur geen bewijs is dat het gebruik van een verdringend systeem zich vertaalt in een lager aantal (diepe) postoperatieve wondinfecties. Hierbij was de bewijskracht van de literatuur zeer laag (retrospectieve observationele cohort studies). De werkgroep heeft geen gewicht toegekend aan de kosten, omdat deze afhangen van lokale factoren. De aanbevelingen zijn in lijn met veel van de internationale medische richtlijnen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Een zo schoon mogelijke chirurgische werkplek wordt in algemene zin van groot belang geacht ter voorkoming van postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI’s). Luchtbehandeling is een van de mogelijkheden om luchtreinheid te beïnvloeden. Hoe groot de bijdrage van luchtbehandeling hieraan is, is - vergeleken met andere hygiënemaatregelen - niet bekend. Er zijn vele aanbieders van luchtbehandelingssystemen met verschillende (lucht)inblaastechnieken. Globaal is er onderscheid te maken tussen mengende en verdringende inblaassystemen. Het is van belang om te weten wat het effect is van de verschillende inblaassystemen op preventie van POWI’s. De keuze voor een systeem en de gebruikte luchtcirculatie heeft zowel organisatorische als klinische implicaties.

De gebruikte definities zijn te vinden in de Algemene inleiding.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Heupprothese

Diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie Het is onzeker of het plaatsen van een heupprothese in een operatiekamer voorzien van een UDF geassocieerd is met meer diepe ‘surgical site’ infecties in vergelijking met het plaatsten van een heupprothese in een operatiekamer voorzien van een mengend systeem.

Bron Bischoff et al., 2017; Pinder et al., 2016 |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Knieprothese

Diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie Er lijkt geen verschil te zijn in het optreden van diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie wanneer een knieprothese geplaatst wordt in een operatiekamer voorzien van een UDF of in een operatiekamer voorzien van een mengend systeem.

Bron Bischoff et al., 2017 |

|

Laag GRADE |

Orthopedische traumachirurgie

Diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie Het is onzeker of er minder diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie optreden wanneer orthopedische traumachirurgie verricht wordt in een operatiekamer voorzien van een mengend systeem.

Bron Bischoff et al., 2017 |

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Abdominale chirurgie, open vasculaire chirurgie en dorsale spondylodese

Totale ‘surgical site’ infectie Er lijkt geen verschil te zijn in het optreden van totale ‘surgical site’ infectie wanneer schone ingrepen respectievelijk niet-schone ingrepen verricht worden in een operatiekamer voorzien van een UDF of van een mengend systeem.

Bron Bischoff et al., 2017; Gruenberg et al., 20014 |

|

__ |

Er werden geen studies geïdentificeerd die een UDF of mengend luchtbehandelingsysteem vergeleken hebben met een systeem op basis van een temperatuur gecontroleerde luchtstroom en POWI als uitkomstmaat. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Zie de evidence tabellen voor gedetailleerde informatie betreffende studiepopulatie, interventie, uitkomstmaten en resultaten. Voor gedetailleerde informatie over het risico op bias per studie zie de risk of bias tabellen.

De systematic review van Bischoff (2017) werd als uitgangspunt genomen en ge-update met twee recent gepubliceerde studies (Agarwal et al., 2017 en Pinder et al., 2016). Tevens werden door de werkgroep aan de review van Bischoff nog twee oudere studies toegevoegd (Gruenberg et al., 2004; Fitzgerald et al., 1992), die in de review van Bischoff geëxcludeerd werden. De redenen van exclusie door Bischoff et al. waren: de studie van Fitzgerald (1992) is weliswaar na 1990 gepubliceerd, echter voor 1990 uitgevoerd*. In de studie van Gruenberg (2004) is in de behandelarm UDF een additionele interventie toegevoegd, i.e. zogenaamde maanpakken waarbij volledige lichaam- en hoofdbedekking wordt gerealiseerd, in de controlegroep is deze additionele interventie niet toegevoegd (zie de evidence tabellen). De werkgroep besliste om deze twee oudere studies wel mee te nemen in tegenstelling tot de auteurs in de review van Bischoff. De redenen hiervoor waren dat de werkgroep het exclusiecriterium “publicatie voor 1990” strikter hanteerde en dat de werkgroep van mening was dat het in de literatuur bewezen is dat het toevoegen van de interventie “total body exhaust gowns” geen effect heeft op POWI. Ter info: het artikel van Fitzgerald was in Nederland niet verkrijgbaar en is daarom uiteindelijk niet meegenomen in de analyse.

* In de review van Bischoff werden studies die voor 1 januari 1990 gepubliceerd werden, geëxcludeerd.

In de review van Bischoff zijn de volgende 12 studies opgenomen: Bosanquet et al., 2013; Brandt et al., 2008; Breier et al., 2011; Dale et al., 2009; Hooper et al., 2011; Jeong et al., 2013; Kakwani et al., 2007; Miner et al., 2007; Namba et al., 2012; Namba et al.; 2013; Pedersen et al., 2010; Song et al., 2012.

Onderzoeksdesign

Alle 15 studies betreffen observationele cohortstudies. De meesten hiervan waren retrospectief.

Land waar studie is verricht

|

Studie verricht in |

Aantal studies |

|

Argentinië |

1 studie: Gruenberg et al.; 2004 |

|

Denemarken |

1 studie: Pedersen et al.,2010 |

|

Duitsland |

2 studies: Brandt et al., 2008; Breier et al., 2011 |

|

Nieuw-Zeeland |

1 studie: Hooper et al., 2011 |

|

Noorwegen |

1 studie: Dale et al., 2009 |

|

UK |

3 studies: Kakwani et al.; 2007; Pinder et al., 2016; Agarwal et al.; 2017 |

|

Verenigde Staten |

3 studies: Namba et al., 2012; Miner et al., 2007; Namba et al., 2013 |

|

Wales |

1 studie: Bosanquet et al., 2013 |

|

Zuid Korea |

2 studies: Song et al., 2012; Jeong et al., 2013 |

Studiepopulaties

De studies onderzochten patiënten die de volgende ingrepen ondergingen:

|

Ingreep |

Aantal studies |

|

Totale heupprothese |

9 studies: Brandt et al., 2008; Breier et al., 2011; Dale et al., 2009; Hooper et al., 2011; Kakwani et al., 2007; Namba et al., 2012; Pedersen et al., 2010; Pinder et al., 2016; Song et al., 2012. |

|

Totale knieprothese |

6 studies: Brandt et al., 2008; Breier et al., 2011; Hooper et al., 2011; Miner et al., 2007; Namba et al.; 2013; Song et al., 2012. |

|

Orthopedische traumachirurgie |

2 studies: Agarwal et al., 2017 en Pinder et al., 2016 |

|

Appendectomie |

1 studie: Brandt et al., 2008 |

|

Colonchirurgie |

1 studie: Brandt et al., 2008 |

|

Cholecystectomie |

1 studie: Brandt et al., 2008 |

|

Herniorafie |

1 studie: Brandt et al., 2008 |

|

Open vasculaire chirurgie |

1 studie: Bosanquet et al., 2013 |

|

Maagoperatie |

1 studie: Jeong et al., 2013 |

|

Dorsale spondylodese |

1 studie: Gruenberg et al., 2004 |

Interventies

Alle 15 studies vergeleken een UDF (interventie) met een niet-UDF (controle). De controlegroep werd in sommige studies beschreven als een conventionele (turbulente) luchtbehandeling. Drie studies rapporteerden de aanwezigheid van HEPA-filtratie in zowel de interventie- als de controlegroep (Brandt et al., 2008; Breier et al., 2011; Song et al., 2012). Geen van de auteurs rapporteerde de technische specificaties van de gebruikte luchtbehandelingsystemen.

Nieuwe systemen:

Temperatuurgecontroleerde luchtinblaas anders dan via een plenum: geen van de studies onderzocht een systeem op basis van temperatuurgecontroleerde luchtinblaas anders dan via een plenum.

Studiekarakteristieken van de 15 geïncludeerde studies

Studiekarakteristieken voor diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie

|

|

Aantal ingrepen (interventie/controle) |

Follow-up |

Puntschatter (95% BI) voor UDF

|

|

Totale heupprothese |

|||

|

Kakwani (2007) |

435 (212/223) |

1 jaar |

RR 0,06 (0,00–0,95)* |

|

Brandt (2008) |

28 623 (17 657/10 966) |

1 jaar |

OR 1,63 (1,06–2,52) |

|

Dale (2009) |

93 958 (45 620/48 338) |

dood / loss to follow-up/ revisie |

RR 1,3 (1,1–1,5) |

|

Pedersen (2010) |

80 756 (72 423/8333) |

dood / loss to follow-up/ revisie |

HR 0,9 (0,7–1,14) |

|

Breier (2011) |

41 212 (29 530/11 682) |

1 jaar |

Artrose OR 1,10 (0,56–2,17); Fractuur OR 1,28 (0,67–2,43) |

|

Hooper (2011) |

51 485 (16 990/34 495) |

6 maanden |

RR 2,42 (1,35–4,32)* |

|

Namba (2012) |

30 491 (8478/22 013) |

1 jaar |

HR 1,08 (0,77–1,53) |

|

Song (2012) |

3186 (2037/1149) |

1 jaar |

RR 1,2 (0,6–2,16)* |

|

Pinder (2016) |

98 064 (85 567/12 497) |

3 maanden |

Na installatie UDF: OR 1,55 (1,17 to 2,00) Altijd LAF: OR 1,45 (1,17 to 1,80) |

|

Totale knieprothese |

|||

|

Miner (2007) |

8288 (3513/4775) |

90 dagen |

RR 1,57 (0,75–3,31) |

|

Brandt (2008) |

9396 (5993/3403) |

1 jaar |

OR 1,76 (0,80–3,85) |

|

Breier (2011) |

20 554 (14 456/6098) |

1 jaar |

OR 0,95 (0,37–2,41) |

|

Hooper (2011) |

36 826 (13 994/22 832) |

6 maanden |

RR 1,92 (1,10–3,34)* |

|

Song (2012) |

3088 (2151/937) |

1 jaar |

RR 0,51 (0,29–0,89) † |

|

Namba (2013) |

56 216 (16 693/39 523) |

1 jaar |

HR 0,91 (0,71–1,16) |

|

Orthopedische traumachirurgie |

|||

|

Pinder (2016) |

660631 (555 884/104 747) |

3 maanden |

OR 0,71 (0,46–1,09) |

|

Agarwal (2017) |

159 (85/74) |

minstens 6 maanden |

OR 2,64 (0,11–65,92)* |

RR=relatief risico. HR=hazard ratio. OR=odds ratio. *Niet gecorrigeerd (puntschatter berekend met ruwe data, geen multivariate analyse). † Niet gecorrigeerd (relatief risico (RR) berekend met ruwe data, niet significant in multivariaat analyse).

Drie studies onderzochten alleen vroege prothese-infecties (follow-up korter dan een jaar) (Hooper et al., 2011; Pinder et al., 2016; Miner et al., 2007).

Studiekarakteristieken voor totale ‘surgical site’ infectie

|

|

Aantal ingrepen (interventie/controle) |

Follow-up |

Gecorrigeerde OR (95% BI) voor UDF |

|

Appendectomie |

|||

|

Brandt (2008) |

10 969 (7193/3776) |

1 jaar |

2,09 (1,08–4,02) |

|

Colonchirurgie |

|||

|

Brandt (2008) |

8696 (6201/2495) |

1 jaar |

1,17 (0,65–2,11) |

|

Cholecystectomie |

|||

|

Brandt (2008) |

20 676 (12 419/8257) |

1 jaar |

1,53 (0,9–2,45) |

|

Herniorafie |

|||

|

Brandt (2008) |

20 870 (12 667/8203) |

1 jaar |

1,67 (0,9–2,91) |

|

Open vasculaire chirurgie |

|||

|

Bosanquet 2013 |

170 (56/114) |

Niet gerapporteerd |

0,38 (0,12–1,19)* |

|

Maagoperatie |

|||

|

Jeong (2013) |

2091 (1919/172) |

1 maand |

0,13 (0,08–0,22)* |

|

Dorsale spondylodese |

|||

|

Gruenberg (2004) |

179 (40/139) |

> dan 2 jaar |

OR 0.08 (0.00–1.38)* |

OR=odds ratio. *Niet gecorrigeerd (puntschatter berekend met ruwe data, geen multivariate analyse).

Resultaten

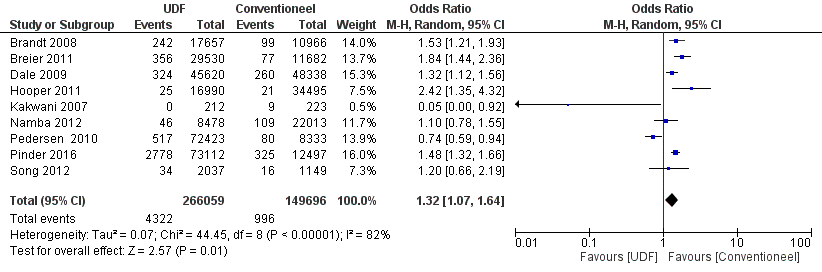

Diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie na plaatsen heupprothese

In negen studies werd diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie als uitkomstmaat onderzocht. Pooling laat zien dat de kans op een diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie hoger is wanneer een heupprothese geplaatst wordt in een operatiekamer voorzien met een UDF (zie figuur 1).

Figuur 1 Diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie na plaatsen heupprothese

Het vóórkomen van diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie neemt toe van 7 per 1000 naar 9 per 1000 wanneer een heupprothese geplaatst wordt in een operatiekamer voorzien met een UDF in plaats van met een mengend systeem.

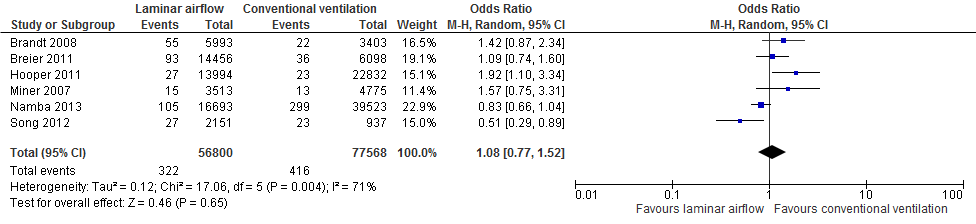

Diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie na plaatsen knieprothese

In zes studies werd diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie als uitkomstmaat onderzocht. Pooling laat geen verschil zien in het aantal diepe ‘surgical site’ infecties tussen wanneer een knieprothese geplaatst wordt in een operatiekamer voorzien met een UDF of een mengend systeem (zie figuur 2).

Figuur 2 Diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie na plaatsen knieprothese

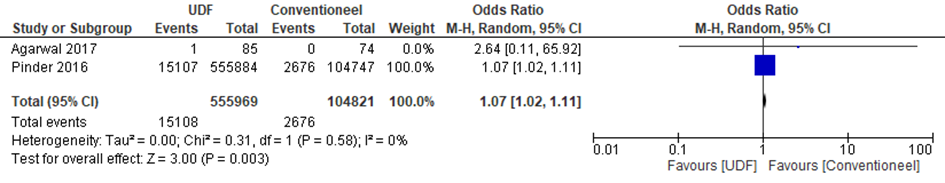

Diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie na orthopedische traumachirurgie

In twee studies werd diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie als uitkomstmaat onderzocht. Pooling laat een (zeer) klein voordeel zien in het aantal diepe ‘surgical site’ infecties wanneer orthopedische traumachirurgie verricht wordt in een operatiekamer voorzien met een mengend systeem (zie figuur 3).

Figuur 3 Diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie na Orthopedische traumachirurgie

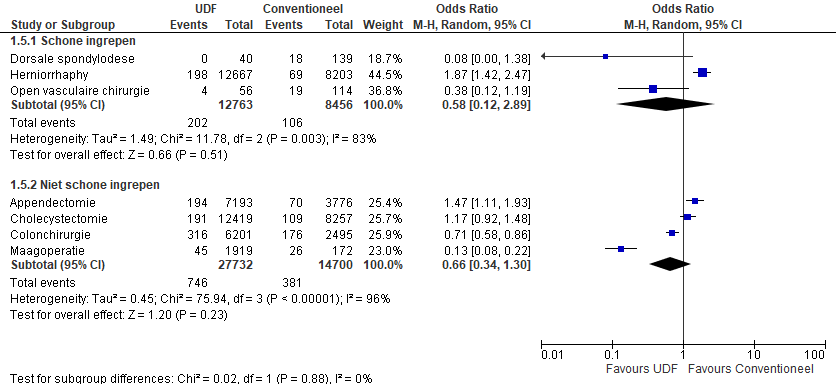

Totale POWI

In vier studies werd totale ‘surgical site’ infectie als uitkomstmaat onderzocht voor uiteenlopende chirurgische ingrepen (Brandt et al., 2008; Bosanquet et al., 2013; Jeong et al., 2013; Gruenberg et al., 2004). Pooling van schone ingrepen respectievelijk niet-schone ingrepen laat geen statistisch significant verschil zien in het totale aantal ‘surgical site’ infecties tussen wanneer deze ingrepen verricht worden in een operatiekamer voorzien met een UDF of een mengend systeem (zie figuur 4).

Figuur 4 Totale ‘surgical site’ infecties na abdominale chirurgie, open vasculaire chirurgie en dorsale spondylodese

Kwaliteit van bewijs

De werkgroep heeft de kwaliteit van bewijs beoordeeld volgens de GRADE-methodiek. Voor studies over interventies (het toepassen van een ander luchtbehandelingsysteem is een interventie) starten gerandomiseerde onderzoeken in de categorie hoog en observationele studies in de categorie laag. De evidence werd per uitkomstmaat getoetst aan de criteria beperkingen in onderzoeksopzet, inconsistentie, indirectheid, onnauwkeurigheid en publicatiebias.

Voor de uitkomstmaten diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie na plaatsen heupprothese / na plaatsen knieprothese / na orthopedische traumachirurgie; totale ‘surgical site’ infecties na abdominale chirurgie, open vasculaire chirurgie en dorsale spondylodese

Vanwege het observationele karakter van de onderzoeken start de kwaliteit van bewijs voor de uitkomstmaat diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie als laag. De bewijskracht werd afgewaardeerd van laag naar zeer laag vanwege de aanwezigheid van statistische heterogeniteit (inconsistentie) (I2 = 82%; 71%; 83% respectievelijk 96%). Daarnaast is het onzeker of de studieresultaten extrapoleerbaar zijn naar de Nederlandse situatie, omdat in Nederland de huidige eisen voor een mengend/verdringend systeem mogelijk anders zijn dan de eisen die in de studies werden toegepast.

Ter info: in de bijlagen kunt u de kwaliteitsbeoordeling van de individuele observationele studies zien.

Voor de uitkomstmaten diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie na orthopedische traumachirurgie

Vanwege het observationele karakter van de onderzoeken is de kwaliteit van bewijs voor de uitkomstmaat diepe ‘surgical site’ infectie laag.

Zoeken en selecteren

Om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden heeft de werkgroep een systematische literatuuranalyse verricht met de volgende PICO-vraagstelling:

Wat is het verschil in effect van de verschillende luchtbehandelingsystemen (zie tabel 1) ten opzichte van elkaar op de uitkomstmaat postoperatieve wondinfectie (POWI) bij patiënten die een chirurgische ingreep ondergaan?

In de databases Medline (OVID), Embase and Cochrane is in april 2018 een systematische search verricht voor deze PICO-vraagstelling. Zie de zoekverantwoording.

Tabel 1 Selectiecriteria

|

Type studies |

|

|

Type patiënten |

|

|

Interventie/control |

versus

versus

|

|

Type uitkomstmaten* |

|

|

Type setting |

|

|

Exclusiecriteria |

|

* De werkgroep heeft de uitkomstmaat ‘contaminatie van de OK-lucht en de instrumenten’ niet meegenomen, omdat dit geen patiëntgerelateerde uitkomstmaat is en derhalve niet beslissend werd geacht bij het formuleren van de aanbeveling.

De literatuurzoekactie leverde 682 treffers op. Zesendertig studies werden geselecteerd op basis van titel en abstract. Na het lezen van de volledige artikelen voldeden hiervan uiteindelijk vijf studies aan de selectiecriteria en werden meegenomen in de literatuuranalyse (Bischoff et al., 2017; Agarwal et al., 2017; Pinder et al., 2016; Gruenberg et al., 2004; Fitzgerald et al., 1992), waaronder de systematic review van Bischoff (2017). In de exclusietabel staan de redenen van exclusie van de andere 31 studies vermeld.

Referentiecheck leverde geen extra artikelen op.

De systematic review van Bischoff (2017) voldeed aan de vereiste AMSTAR-kwaliteitscriteria (zie bijlagen). De systematic review van Evans (2011), die aanvankelijk geselecteerd werd, voldeed niet aan de vereiste AMSTAR-kwaliteitscriteria en werd daarom geëxcludeerd (zie exclusietabel).

Referenties

- Advies van de Hoge Gezondheidsraad nr. 8573. Aanbevelingen voor de beheersing van de postoperatieve infecties in het operatiekwartier. Mei 2013 – Update 23/07/2014

- Agarwal, S. K., et al. Hip fracture surgery in mixed-use emergency theatres: is the infection risk increased? A retrospective matched cohort study. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 2017. 99(8): 641-644.

- Bischoff, P., et al. Effect of laminar airflow ventilation on surgical site infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2017. 17(5): 553-561.

- CDC guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, USA, 2017

- Fitzgerald RH Jr. Total hip arthroplasty sepsis. Prevention and diagnosis. Orthop Clin North Am 1992; 23: 259–64.

- Gruenberg MF, Campaner GL, Sola CA, Ortolan EG. Ultraclean air for prevention of postoperative infection after posterior spinal fusion with instrumentation: a comparison between surgeries performed with and without a vertical exponential fi ltered air-fl ow system. Spine 2004; 29: 2330–34.

- Langvatn H, Bartz-Johannessen C, Schrama JC, et al. Operating room ventilation - Validation of reported data on 108 067 primary total hip arthroplasties in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. J Eval Clin Pract. 2019;1-8 https://doi.org/ 10.1111/jep.13271.

- NICE guideline Surgical site infection, UK, 2013

- NICE guideline Joint replacement (primary): hip, knee and shoulder, UK, 2020

- Pinder E. M., et al. Does laminar flow ventilation reduce the rate of infection? an observational study of trauma in England. Bone & Joint Journal 2016. 98-B(9): 1262-1269.

- Robert Koch-Instituut. Prävention postoperativer Wundinfektionen Empfehlung der Kommission für Krankenhaushygiene und Infektionsprävention (KRINKO) beim Robert Koch-Institut, 2018

- WHO Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 2016

Evidence tabellen

AMSTAR-beoordeling review Bischoff

(Effect of laminar airflow ventilation on surgical site infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2017)

|

Was an 'a priori' design provided? |

Yes The authors followed the PRISMA guidelines. |

|

Was there duplicate study selection and data extraction? |

Yes Two independent reviewers (PB and PG) screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved references for potentially relevant studies. The full text of all potentially eligible articles was obtained and then reviewed independently by two authors (PB and PG) or eligibility. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or after consultation with NZK, when necessary. |

|

Was a comprehensive literature search performed? |

Yes We searched MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and WHO regional medical databases. We used a comprehensive list of search terms—ie, “ventilation”, “surgical wound infection”, and “operating rooms”—including Medical Subject Headings (appendix pp 1, 2), for studies published between Jan 1, 1990, and Jan 31, 2014. We updated the search for MEDLINE for the period between Feb 1, 2014, and May 25, 2016. |

|

Was the status of publication (i.e. grey literature) used as an inclusion criterion? |

Unclear The authors did not report whether they searched for grey literature. Unpublished studies were not included in the analysis. |

|

Was a list of studies (included and excluded) provided? |

Partly The authors didn’t provide a list of the excluded studies and they didn’t reference the excluded studies in a clear way.

109 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. The authors reported that 97 full-text articles were excluded. The reasons were: 89 studies were not relevant to PICO question; in 4 studies the intervention were combined with additional measures (ref: 41, 42, 43, 44), in 1 study the study period was out of date (ref 17), 1 review (ref?), 1 primary data not available (ref 45), 1 full text not available (ref?). |

|

Were the characteristics of the included studies provided? |

Yes See evidence tables in supplement. |

|

Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented? |

Yes Quality was assessed with the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) for cohort studies (appendix p 18). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or after consultation with NZK, when necessary. |

|

Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? |

No The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) method (GRADEpro software) was used to assess the quality of evidence retrieved as appropriate.

The evidence for laminar airflow ventilation vs. conventional ventilation for patients undergoing THA and TKA, was graded very low (see Grade tables, supplement). However, in the conclusions the authors didn’t account for the level of evidence (i.e. very low). They should have stated that “laminar airflow compared to conventional ventilation may increase the risk of deep surgical site infection after total hip arthroplasty. However, we are unsure because the level of evidence is very low and we cannot exclude a null effect”.

They should have stated that “laminar airflow compared to conventional ventilation may not increase the risk of deep surgical site infection after total knee arthroplasty. However, we are unsure because the level of evidence is very low and we cannot exclude harm [appreciable harm (OR≥1.25) crosses the confidence interval (0.77-1.52)”. |

|

Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate? |

Yes Meta-analyses of available comparisons were done with RevMan (version 5.3) as appropriate. Crude estimates were pooled as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs by use of a DerSimonian and Laird random eff ect model for each comparison. |

|

Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed? |

Yes Funnel plots were created to assess whether publication bias occurred. |

|

Was the conflict of interest included? |

Yes The authors have declared that no competing interests exist. |

AMSTAR-beoordeling review Evans 2011

(Current Concepts for Clean Air and Total Joint Arthroplasty: Laminar Airflow and Ultraviolet Radiation)

|

Was an 'a priori' design provided? |

No The author didn’t refer to an a priori protocol and there is no method paragraph.

The research question is unclear (comparator to LAF?; study design?) and there are no selection criteria reported.

Just the search strategy is presented. |

|

Was there duplicate study selection and data extraction? |

No There was just one author. |

|

Was a comprehensive literature search performed? |

Yes The author searched in several databases.

Remark: the string does not include the term “ventilation”. |

|

Was the status of publication (i.e. grey literature) used as an inclusion criterion? |

Unclear The authors did not report whether they searched for grey literature. Unpublished studies were not included in the analysis. |

|

Was a list of studies (included and excluded) provided? |

No

|

|

Were the characteristics of the included studies provided? |

No |

|

Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented? |

No

|

|

Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? |

No

|

|

Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate? |

No |

|

Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed? |

No

|

|

Was the conflict of interest included? |

Yes The author has received research support from Cubist Pharmaceuticals (Boston, MA) and is a consultant with DePuy (Warsaw, IN) and Smith and Nephew (Memphis, TN). |

Evidence tabellen

|

Authors (year) |

Design |

Objective |

Population, Type of surgery |

Setting, Scope |

Control, Intervention |

Methods |

Results |

Limitations |

|

Namba et al (2013) |

Retro-spective review of a pro-spectively followed cohort |

To evaluate risk factors associated with deep surgical site infection (SSI) following total knee arthroplasty in a large U.S. integrated health care system |

No. of Patients: Total: N=56216 Control group: N=39523 (70.3%) Intervention group: N=16693 (29.7%)

Patient characteristics: Adult patients: average age: 67.4 yrs

Procedures: Primary elective total knee arthroplasties only |

Location: 45 locations in 6 regions in the USA Dates: April 1, 2001 – Dec 30, 2009 Scope: mutlicentre

N=52034 patients (92.6%) received surgical antibiotic prophylaxis (SAP). |

Control group: Operating rooms (ORs) without laminar airflow (LAF)

Intervention group: Laminar airflow in the operating room. |

Definitions: The CDC definitions were used for identifying deep surgical site infections (dSSI). Superficial wound infections were not considered.

Statistical analysis: Chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test) was used to compare patient, surgeon/ hospital and procedure characteristics between groups with or without dSSI. Continuous variables were compared by using t-test for two independent samples. Univariable Cox proportional hazard models (CpHm) of the association between variables and dSSI were built. All factors found to be independently associated with dSSI were included in the multivariable CpHm. Collinearity and potential confounding by covariables were assessed.

Data collected by a total joint replacement registry were combined with data from the patient’s electronic health records. |

Follow-up period: until the date of diagnosis of dSSI (CDC: 12 months) lost-to-follow-up: until date of termination of the insurance policy or death

Control group: dSSI: 299/39523 (0.8%) (calculated)

Intervention group: dSSI: 105/16693 (0.6%)

LAF: no dSSI: N=16588 (29.7%) (compared with total of no dSSI)

dSSI: N=105 (26%) (compared with total of dSSI), P= 0.102

Unvariable (CpHm): Hazard Ratio (HR): 0.83 (95% CI: 0.66-1.04), P=0.1

Multivariable (CpHm): Hazard Ratio (HR): 0.91 (95% CI: 0.71-1.16), P=0.436 |

Infection risk factors that are not collected in the registry cannot be evaluated (i.e. postoperative wound classification). The investigators did not provide additional information about the ventilation system of the ORs without LAF. Upon request they reported that they have regarded LAF as a “preventive measure” during the surgical procedure within their dataset. |

|

Namba et al (2012) |

Retro-spective review of a pro-spectively followed cohort |

To evaluate risk factors associated with dSSI following total hip replacement in a large U.S. integrated health care system |

No. of Patients: Total: N=30491 Control group: N=22013 (72.2%) Intervention group: N=8478 (27.8%)

Patient characteristics: Adult patients: average age: 65.5 yrs

Procedures: Primary elective total hip replacement only |

Location: 46 locations in 6 regions in the USA Dates: April 1, 2001 – Dec 30, 2009 Scope: mutlicentre

N=27943 patients (91.6%) received SAP. |

Control group: ORs without LAF

Intervention group: The use of LAF in the operating room. |

Definitions: The CDC definitions were used for identifying dSSI.

Statistical analysis: Chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test) was used to compare patient, surgeon/ hospital and procedure characteristics between groups with or without dSSI. Continuous variables were compared by using t-test for two independent samples. Univariable CpHm of the association between variables and dSSI were built. All factors found to be independently associated with dSSI were included in the multivariable CpHm. Collinearity and potential confounding by covariables were assessed.

Data collected by a total joint replacement registry were combined with data from the patient’s electronic health records. |

Follow-up period: until the date of diagnosis of dSSI (CDC: 12 months) lost-to-follow-up: until date of termination of the insurance policy or death: Attrition rate of 2.7% (N=826)

Control group: dSSI: 109/22013 (0.5%) (calculated)

Intervention group: dSSI: 46/8478 (0.5%)

LAF: no dSSI: N=8432 (27.8%) (compared with total of no dSSI)

dSSI: N=46 (29.7%) (compared with total of dSSI) P= 0.602

Unvariable (CpHm): Hazard Ratio (HR): 1.08 (95% CI: 0.77-1.53) P=0.651 |

Infection risk factors that are not collected in the registry cannot be evaluated (i.e. postoperative wound classification). The investigators did not provide additional information about the ventilation system of the ORs without LAF. Upon request they reported that they have regarded LAF as a “preventive measure” during the surgical procedure within their dataset. |

|

Song et al (2012) |

Retro-spective cohort study |

To characterize and identify the risk factors for SSIs after total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in a nationwide survey using shared case detection and recording systems |

No. of Patients: Total: N=6848 THA: N=3422 TKA: N=3426

Patient characteristics: Mostly adult patients: average age: 67 yrs; range: 15 – 107 yrs

Procedures: Total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty |

Location: 26 hospitals (300 or more beds), Republic of Korea Dates: 2006 – 2009: total of 396 months Scope: multicentre

N=6341 patients (92.6%) received SAP. |

Group 1: HEPA filter and LAF ventilation

Group 2: HEPA filter and conventional turbulent ventilation

Group 3: no artificial ventilation

No. of interventions: THA: Group 1: N=2037 Group 2: N=1149 Group 3: N=236

TKA: Group 1: N=2151 Group 2: N=937 Group 3: N=338 |

Definitions: The CDC definitions were used for identifying SSIs.

Statistical analysis: Differences between patients with or without SSI were analyzed using the x²-test for categorical variables and the t-test for continuous variables. A stepwise multiple logistic regression model was used to identify independent risk factors for SSI. In univariable analysis variables with p<0.1 were included in further analysis. Significance threshold in multivariable analysis was p<0.05.

Data were provided by the Korean Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System.

|

Follow-up period: 12 months

Univariable Analysis: THA: Superficial AND deep SSIs: Total: N=78 Group 1: 50/78 (64%) “Reference” Group 2: 20/78 (26%) OR: 0.7 (95% CI: 0.47-1.19) Group 3: 8/78 (10%) OR: 1.39 (95% CI: 0.65-2.98)

TKA: Superficial AND deep SSIs: Total: N=83 Group 1: 37/83 (45%) “Reference” Group 2: 29/83 (35%) OR: 1.83 (95% CI: 1.12-2.99) Group 3: 17/83 (20%) OR: 3.03 (95% CI: 1.68-5.44)

Multivariable Analysis: TKA: Group 1: “Reference” Group 2: Not significant Group 3: Superficial AND deep SSIs: OR: 2.82 (95% CI: 1.45-5.49) DSSIs only: OR: 2.81 (95% CI: 1.30-6.07)

The author kindly provided data and numbers of dSSIs upon request for further calculation. |

The investigators considered “HEPA filter and LAF ventilation” as the reference ventilation system. Thus, they compared “no artificial ventilation” with “HEPA filter and LAF ventilation”. They did not compare “no artificial ventilation” with “conventional turbulent ventilation” in their analyses. Possible selection bias as smaller hospitals with <300 beds were excluded. No information about patients that were lost to follow-up/ attrition; 113 patients (of a total of N=6961 operations within the study) who did not complete the 1-year-follow-up period were not counted as attrition but excluded from the study.

|

|

Jeong et al (2013) |

Prospective cohort study |

To determine the incidence of and risk factors for SSI in patients undergoing gastric surgery |

No. of Patients: Total: N=2091

Patient characteristics: Adult patients: average age: 60.1 yrs (SSI group) 58.5 yrs (non-SSI group)

Procedures: Gastric surgery due to gastric tumor (99.5%), other (0.05%) |

Location: 10 hospitals (>500 beds; 9 tertiary care, 1 secondary hospital), Republic of Korea Dates: June 1, 2010 – Aug 31, 2011 Scope: multicentre

N=1998 patients (95.6%) received SAP

|

Hospital data about the operating room environment were evaluated for (1) presence of LAF ventilation, (2) presence of HEPA-filters and other variables.

Intervention group: N=1919 patients operated in ORs with LAF ventilation

|

Definitions: The CDC definitions were used for identifying SSIs.

Statistical analysis: All variables were compared between the SSI group and the non-SSI group either using the t-test or the chi-square test. The associated effects of various variables on SSIs were assessed by a logistic regression model. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The authors reported results for the Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact but they did not include the tests in their methods section.

Data were provided by an SSI Surveillance Program. |

Follow-up period: 1 month

Presence of LAF:

no SSI: N=1874 (92.8%) (compared with total of no SSI)

SSI: N=45 (63.4%) (compared with total SSI) P<0.001

Multivariable analysis: Absence of LAF: OR: 2.45 (95% CI: 1.13-5.31) P=0.024 |

Almost all operations were performed in ORs with LAF ventilation (N=1919) and ORs equipped with HEPA filters (N=1963). The investigators did not provide additional information about the ventilation system of the ORs without LAF (N=172).

Possible selection bias as smaller hospitals with <500 beds) were excluded. No information about patients that were lost to follow-up/ attrition.

|

|

Bosanquet et al (2013) |

Retro-spective review of a pro-spectively maintained database |

To identify factors influencing the rate of infection after open vascular surgery. |

No. of Patients: Total: N=170 Control group: N=114 Intervention group: N=56

Patient characteristics: Adult patients: average age: 64.8 yrs (non-laminar flow group) 69.1 yrs (laminar flow group)

Procedures: Open vascular procedures (arterial and venous) including arterial bypasses |

Location: 1 hospital (570 beds), Wales, United Kingdom Dates: not reported Scope: single centre

All patients N=170 received SAP. Narrated that all patients underwent the same preparation procedure prior to surgery. Surgery was performed by the same surgeon and assisting team.

|

Surgery was performed in both LAF and conventional ORs with allocation randomly assigned via the waiting list. Surgery in LAF environment was considered as intervention. |

Definitions: The CDC definitions were used for identifying SSIs.

Statistical analysis: To compare both groups a two-tailed student’s t-test was used for continuous variables and a two tailed chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The effects of various variables on SSIs were assessed by a logistic regression model. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to assess model goodness of fit. p<0.05 was considered significant. |

Follow-up period: not reported

Control group: SSI: 19/114 (16.7%)

Intervention group: SSI: 4/56 (7.1%)

Of the 23 SSIs, 14 were superficial and 9 were deep infections. The investigators did not state how many of the superficial and deep SSIs were in the control or in the intervention group.

Comparison (SSI) between groups: P=0.1

Non-LAF room: no SSI: N=95 (64.6%) (compared with total of no SSI)

SSI: N=19 (82.6%) (compared with total SSI) P=0.108

Multivariable analysis: Absence of LAF: OR: 4.02 (95% CI: 1.18-13.69) P=0.026

Patients undergoing arterial graft insertion: Co: SSI: 15/46 (32.6%) In: SSI: 4/35 (11.4%) P=0.034

Non-LAF room: no SSI: N=31 (50%) (compared with total of no SSI)

SSI: N=15 (78.9%) (compared with total SSI) P=0.04

Multivariable analysis: Absence of LAF: OR: 3.47 (95% CI: 1.02-11.88) P=0.047 |

Very high SSI rate. Small number of patients and large confidence intervals. Most likely some SSIs were not detected because the study lacked of a defined follow-up period. The authors note that the case mix is heterogeneous and not equally matched between the two OR environments, i.e. all five axillary bypass procedures were undertaken in a non-LAF room. The percent of patients that received SAP differed by group. The investigators did not describe the number of patients that were lost to follow-up or the attrition rate.

|

|

Pedersen et al (2010)36 |

Population-based follow-up study using prospective data |

To examine potential patient- and surgery-related risk factors for revision due to infection after primary total hip arthroplasty (THA)

|

No. of Patients: Total: N=80756 THAs in N=74639 patients

Patient characteristics: Adult patients

Procedures: Revision following primary elective total hip arthroplasties due to infection only

|

Location: hospitals (N=52) in Denmark Dates: Jan 1 1995 – Dec 31 2008 Scope: multicentre |

Operations performed in ORs with a conventional ventilation system served as reference/ control.

Intervention group: Primary elective total knee arthroplasties performed in ORs with LAF ventilation.

|

Definitions: Infections were classified according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-8 up to 1995; ICD-10 after 1995). SSIs were identified by the surgeon.

Statistical analysis: Cox’s regression analysis was used to examine the association between variables and risk of revision due to infection. A hazard ratio was estimated as a measure of relative risk with 95% CI for each risk factor, crude and adjusted. Bilateral THAs were treated as 2 independent cases.

Data were obtained from the Danish Hip Arthroplasty Register. |

Follow-up period: average 5 yrs (range 0-14) Follow up started on the day of primary THA until death, emigration or the day of revision.

Revisions due to infection: Total: N=597/80756 (0.74%)

Control group: 80/8333 (0.96%) Crude and adjusted (adj) HR: 1 “reference”

Intervention group: 517/72423 (0.71%) Crude HR: 0.81 (95% CI: 0.64-1.03) Adj HR: 0.9 (95% CI: 0.7-1.14) |

The effect of prior surgical procedures and systemic antibiotics were not studied due to the small sample size and low number of revisions. No data on SSI in general: severe infections leading to revision operation were assessed. Some possible confounders related to risk factors and infection rate that were not available in the dataset (i.e. weight, height, smoking, alcohol intake, medication) may have influenced the risk estimates in this study. Lack of registration of revisions may have caused underestimation of the overall revision rate. Inconsistent coding practices may have introduced residual confounding. |

|

Dale et al (2009) |

Observa-tional cohort study |

To assess the risk factors for revision due to deep infection after primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) |

No. of Patients: Total: N=97344 THAs in N=79820 patients

Patient characteristics: Adult patients; males 30%, females 70 %

Procedures: Revision following primary elective total hip arthroplasties (cemented or not) due to infection only

|

Location: hospitals in Norway Dates: Sept 15, 1987 – Jan 1, 2008 Scope: multicentre

The endpoint in analysis was removal or exchange of the whole or parts of the prosthesis due to infection. If infections were cured with the prosthesis in situ (i.e. isolated soft tissue revision) it was not considered.

92% (1987-1992) to 100% (1993-2007) of the patients received SAP. |

Operations performed in ORs with (1) LAF and (2) in “green-house” environment were analyzed. Operations performed in ORs with a conventional ventilation system served as the reference for each variable.

|

Definitions: Definitions used for identifying dSSI were not reported.

The infection was reported by the surgeon.

Statistical analysis: As the follow-up period was 20 years, 4 time periods were compared. Revision rate ratios and p-values are relative to the first time period. It was adjusted for differences over time concerning various risk factors. Cox regression analyses with stratification factors were used to construct cumulative revision curves at mean values of the covariates, and to assess 5-year survival percentages. Risk ratio analyses were performed for the different risk factors. P<0.5 was considered significant.

Data were obtained from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register.

|

Follow-up period: range 0-20 yrs Follow up was until death, emigration or the day of revision.

Revisions due to deep infection: Total: N=614/97344 (0.63%)

In analyses the variables are adjusted for all the other risk factors in addition to year of surgery:

Control group: The relative revision risk for operations performed in ORs with a conventional ventilation system was used as reference. 260/48338 (0.54%) RR: 1 “reference”

Intervention group: LAF 324/45620 (0.71%) RR: 1.3 95% CI: 1.1 – 1.5 P=0.006

“greenhouse” environment 30/3386 (0.89%) RR: 1.3 (95% CI: 0.9-2.0), P=0.2 |

Possible confounders related to risk factors and the infection rate which were not available in the dataset (i.e. obesity, diabetes) may have influenced the risk estimates in this study. ASA-score was only registered from 2005-2008. No data on SSI in general: severe infections leading to revision operation were assessed. Information about the AP application and possible changes over the years was not analyzed. |

|

Brandt et al (2008) |

Retro-spective cohort study |

To evaluate whether OR ventilation with LAF effects SSI rates. |

No. of Patients: Total: N=99230 THAs: N=28623 TKAs: N=9396 Appendectomy: N=10969 Cholecystectomy: N=20676 Colon surgery: N=8696 Herniorrhaphy: N=20870

Patient characteristics: not described but adjusted for patient characteristics in analysis

Procedures: Total hip arthroplasty (THA), Total knee arthroplasty (TKA), Appendectomy (App), Cholecystectomy (Chole), Colon surgery (Colon), Herniorrhaphy (Hern) |

Location: 63 surgical departments in 55 hospitals in Germany Dates: Jan 2000 – June 2004 Scope: multicentre

SAP administa-tion was not documented in the surveillance data for each patient, but the authors reported that SAP was routinely administered in Germany. In 2004 98.3% of patients undergoing THA and 98.2% of patients undergoing TKA received PAP.

|

Control group: Operations performed in ORs equipped with a conventional ventilation system

Intervention: Operations performed in ORs equipped with a LAF ventilation system

HEPA filters had been installed in both settings. |

Definitions: The CDC definitions were used for identifying SSIs.

Statistical analysis: Univariable analysis was performed and data were stratified by OR ventilation type. Comparison of these results by Fisher exact test. Multivariable analyses were performed using the generalized estimating equations method to control for potentially confounding variables. Separate multiple logistic regression analyses were carried out for each operative procedure.

Data were provided by the German National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Additional data were obtained with a questionnaire in 08/2004. |

Follow-up period: until the date of SSI diagnosis (dSSI); CDC: 1 (12) month(s), but post discharge surveillance was not complete

Total SSI: 1901/99230 (1.92%)

THA: Control group: total SSI: N=144/10966 (1.31%) dSSI: N=99/10966 (0.9%) Intervention group: total SSI: N=326/17657 (1.85%) adj OR: 1.44 (95% CI: 0.93-2.23) dSSI: N=242/17657 (1.37%) adj OR: 1.63 (95% CI: 1.06-2.52)

TKA: Control group: total SSI: N=28/3403 (0.82%) dSSI: N=22/3,403 (0.65%) Intervention group: total SSI: N=80/5993 (1.33%) adj OR: 2.38 (95% CI: 0.89-6.33) dSSI: N=55/5993 (0.92%) adj OR: 1.76 (95% CI: 0.8-3.85)

App: Control group: total SSI: N=70/3776 (1.85%) dSSI: N=41/3776 (1.09%) Intervention group: total SSI: N=194/7193 (2.70%) adj OR: 2.09 (95% CI: 1.08-4.02) dSSI: N=95/7193 (1.32%) adj OR: 1.52 (95% CI: 0.91-2.53)

Chole: Control group: total SSI: N=109/8257 (1.32%) dSSI: N=40/8257 (0.48%) Intervention group: total SSI: N=191/12419 (1.54%) adj OR: 1.53 (95% CI: 0.95-2.45) dSSI: N=87/12419 (0.7%) adj OR: 1.37 (95% CI: 0.63-2.97)

Colon: Control group: total SSI: N=176/2495 (7.1%) dSSI: N=68/2495 (2.73%) Intervention group: total SSI: N=316/6201 (5.1%) adj OR: 1.17 (95% CI: 0.65-2.11) dSSI: N=158/6201 (2.55%) adj OR: 0.85 (95% CI: 0.49-1.49)

Hern: Control group: total SSI: N=69/8203 (0.84%) dSSI: N=29/8203 (0.35%) Intervention group: total SSI: N=198/12667 (1.56%) adj OR: 1.67 (95% CI: 0.95-2.91) dSSI: N=73/12667 (0.58%) adj OR: 1.48 (95% CI: 0.67-3.25) |

Whether SAP was administered was not documented individually for each patient in the surveillance data. Possible critical confounders such as smoking, obesity, intraoperative temperature, glycaemia or cautery, are also missing in the surveillance data. The investigators did not describe the number of patients that were lost to follow-up or the attrition rate.

|

|

Breier et al (2011) |

Retro-spective cohort study |

To determine the effect of LAF systems on SSI rates with emphasis on the size of the LAF ceiling.

|

No. of Patients: Total: N=61766 THAs due to arthrosis: N=33463 THAs due to fracture: N=7749 TKAs: N=20554

Patient characteristics: not described but adjusted for patient characteristics in analysis

Procedures: elective hip prosthesis procedures due to arthrosis, urgent hip prosthesis procedures due to fracture, knee prosthesis |

Location: 48 hospitals included in the final analysis for HIP-A, 41 for HIP-F, and 38 for TKA in Germany Dates: July 2004 – June 2009 Scope: multicentre

SAP administa-tion was not documented in the surveillance data for each patient, but the authors reported that SAP was routinely administered in Germany. In 2008, SAP was given for 99.2% of hip prosthesis procedures and for 99.4% of knee prosthesis procedures. |

Control group: Operations performed in ORs equipped with a conventional ventilation system

Intervention: Operations performed in ORs equipped with a LAF ventilation system

HEPA-filters had been installed in both settings. |

Definitions: The CDC definitions were used for identifying SSIs.

Statistical analysis: Univariable and multivariable analyses assessed the association of the following variables: sex, age, duration of operation, and American Association of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score. The size of the ceiling was considered in the group of hospitals with LAF (at least 3.2 m x 3.2 m vs less than 3.2 m x 3.2 m). In addition, large ceilings were compared with no LAF. For each operative procedure, separate multiple logistic regression analyses were performed with the generalized estimating equations method. Data were provided by the German National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. An online survey was sent to all departments to obtain information on the ventilation technology installed and routinely used in their ORs. The survey data on the ventilation techniques and the SSI surveillance data were merged.

|

Follow-up period: until the date of diagnosis of dSSI (CDC); 12 months, but post discharge surveillance was not complete

THAs due to arthrosis: Control group: dSSI: N=52/10446 (0.5%)

Intervention group: total dSSI: N=196/23017 (0.85%) LAF ceiling size <3.2 m x 3.2m: N=61/7291 (0.84%) LAF ceiling size ≥ 3.2 m x 3.2m: N=135/15726 (0.86%)

adj OR for LAF/dSSI: 1.10 (95% CI: 0.56-2.17)

THAs due to fracture: Control group: dSSI: N=25/1236 (2.02%) Intervention group: total dSSI: N=160/6513 (2.46%) LAF ceiling size <3.2 m x 3.2m: N=63/2326 (2.71%) LAF ceiling size ≥3.2 m x 3.2m: N=97/4187 (2.32%)

adj OR for LAF/dSSI: 1.28 (95% CI: 0.67-2.43)

TKA: Control group: dSSI: N=36/6098 (0.59%) Intervention group: total dSSI: N=93/14456 (0.64%) LAF ceiling size <3.2 m x 3.2m: N=23/4564 (0.5%) LAF ceiling size ≥ 3.2 m x 3.2m: N=70/9892 (0.71%)

adj OR for LAF/dSSI: 0.95 (95% CI: 0.37-2.41) |

Whether SAP was administered was not documented individually for each patient in the surveillance data. Possible critical confounders such as smoking, obesity, intraoperative temperature, glycaemia or cautery, are also missing in the surveillance data. The investigators did not describe the number of patients that were lost to follow-up or the attrition rate.

|

|

Hooper et al (2011) |

Retro-spective cohort study |

To determine, if the use of LAF and protective suits with hoods and self-contained exhaust systems (space suits) reduce the rate of early deep infections requiring revision procedures following total hip and knee replacement |

No. of Patients: Total: N=88311 THA: N=51485 TKA: N=36826

Patient characteristics: not reported but the investigators stated that there were no significant differences between the groups

Procedures: THA, TKA |

Location: 64 hospitals in New Zealand Dates: 1999 – 2008 Scope: multicentre

The registry indicated that in 96% of the procedures SAP was administered and in 60% of the procedures anti-microbial agents were used in the cement. |

Control group: 1: operation performed without space suit 2: operation performed in conventional ORs 3: operation performed in conventional ORs with no space suit

Intervention: 1: space suits used 2: operation performed in ORs equipped with a LAF ventilation system 3: space suits and LAF

LAF: all hospitals confirmed that they had a regular maintenance program for filters. |

Definitions: Any revision performed within 6 months of the initial operation for infection.

Statistical analysis: The Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, when expected frequencies were low, were used to compare the percent of procedures in each group with revision for deep infection. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Data were obtained from the New Zealand Joint Registry. The registry captures 98% of both primary and revision arthroplasties performed in New Zealand and records revision procedures secondary to deep infection. |

Follow-up period: minimum 6 months

ORs equipped with LAF ventilation system were used for 33% of all THAs and for 38% of all TKAs.

Note: Authors only provide percentages; “n” was calculated for analyis.

THA: Early revision for deep infection: 46/51485 (0.089%)

Intervention 1- space suit: 0.186% Control 1- no space suit: 0.064% (P<0.0001)

Intervention 2 - LAF: 0.148% Control 2 - conventional ORs: 0.061% (P<0.003)

Intervention 3 - space suit + LAF: 0.198% Control 3 - no space suit + conventional ORs: 0.053% (P<0.001)

TKA: Early revision for deep infection: 50/36826 (0.136%)

Intervention 1- space suit: 0.243% Control 1- no space suit: 0.098% (P<0.001)

Intervention 2 - LAF: 0.193% Control 2 - conventional ORs: 0.100% (P<0.019)

Intervention 3 - space suit + LAF: 0.25% Control 3 - no space suit + conventional ORs: 0.087% (P<0.001) |

Authors only provide percentages; “n” was calculated. Infection risk factors that are not collected in the registry cannot be evaluated. The investigators did not describe the number of patients that were lost to follow-up or the attrition rate. |

|

Miner et al (2007) |

Retro-spective cohort study |

To assess the effects of LAF systems and body exhaust suits on the risk of deep infection after TKA |

No. of Patients: TKA: N=8288

Patient characteristics: not reported

Procedure: Unilateral primary TKA |

Location: 256 hospitals in Illinois, Ohio, North Carolina and Tennessee, USA Dates: January 1 – August 30, 2000 Scope: multicentre

The percent of procedures for which SAP was used was not reported

|

Control group: 1) Patients in hospitals that used exhaust suits at frequencies of “not at all”, “used in less than 26% of procedures,” “used in 26%-75% of procedures” 2) Patients in hospitals that used LAF at frequencies of “not at all”, “used in less than 26% of procedures,” “used in 26%-75% of procedures”

Intervention: 1: Patients in hospitals that used exhaust suits in more than 75% of procedures 2: Patients in hospitals that used LAF in more than 75% of procedures

Use of LAF and exhaust suit was distributed roughly independently among hospitals. Most hospitals reported that these methods were either part of their standard infection control practices (used>75% of time) or not at all. |

Definitions: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision (ICD-9) diagnosis and procedures codes for evidence of postoperative deep infection that required additional operative procedures. Reoperations within 90 days

Data were used from Medicare claims. |

Follow-up period: 90 days

Overall 90-day cumulative incidence of deep infection requiring reoperation: 28/8288 (0.34%)

1) Body exhaust suit Control group: dSSI N=18/4750 Intervention group: dSSI: N=10/3538

RR for use of body exhaust suit/dSSI: 0.75 (95% CI: 0.34-1.62)

2) LAF Control group: dSSI N=13/4775 Intervention group: dSSI: N=15/3513

RR for LAF/dSSI: 1.57 (95% CI: 0.75-3.31) |

Not adjusted for clustering of events within hospitals, because 22 of 25 hospitals with infections reported only one infection and because no hospital reported more than two infections. Very limited number of events. The focus of the investigators on the hospitals’ standard practice could have led to misclassification of individual procedures. Infections associated with hospitals that were classified as using one of the investigated techniques most of the time could have affected patients for whom the technique was not used. Limited information about each hospital’s case mix. The investigators did not provide additional information about the ventilation system of the ORs without LAF. The investigators did not describe the number of patients that were lost to follow-up or the attrition rate. |

|

Kakwani et al (2007) |

Cohort study |

To assess the difference in the re-operation rate following Austin-Moore hemi-arthroplasty between procedures performed under LAF to those performed in conventional (non-LAF) ORs |

No. of Patients: TKA: N=435

Patient characteristics: 337 females and 96 males Adults, mean age > 80 years

Procedure: Austin-Moore hemiarthroplasty |

Location: 1 hospital in the United Kingdom Dates: August 2000 – July 2004 Scope: single centre

SAP (three doses of intravenous cefuroxime, 1.5 g at induction and two post-operative doses of 750 mg at 8 and 16 h after the procedure) and water-impervious surgical gowns and drapes were used in all cases. |

Control group: Operations performed in ORs equipped with a conventional ventilation system

Intervention: Operations performed in ORs equipped with a LAF ventilation system |

Definitions: Any revision for infection.

Statistical analysis: The Fisher’s exact test and Wilcoxon test were used to evaluate the difference in outcomes between the groups |

Follow-up period: 1 year

Control group: Reoperation for infection: N=9/223 (4%)

Intervention group: Reoperation for infection: N=0/212 (0%) |

Very limited number of events. The investigators did not describe the number of patients that were lost to follow-up or the attrition rate. |

|

Pinder et al (2016) |

Retrospective review of a prospectively maintained database |

To determine how frequently orthopaedic trauma operations are performed in LF and PVtheatres in England; to identify any difference in the rate of SSI90 between these ventilation systems and to determine if the risk of SSI90 is altered following the installation of LF |

No. of Patients: Total N: 759134

Patient characteristics: Age: 45% 65+ Gender: 55% female

Procedure: Orthopaedic trauma operations; subgroupanalysis for hip hemiarthroplasty. |

Location: NHS hospitals providing adult trauma services in England

Dates: April 2008 – March 2013

Scope: Multicenter; 184 hospitals

No information on patients having received surgical antibiotic prophylaxis (SAP) was reported |

Control group: Plenum ventilation

Intervention: Operations per-formed in ORs equipped with a LAF ventilation system. LAF ventilation system was divided into four categories, taking into account the time of installation relative to the operation: always LAF; installed LAF-before; installed LAF-year of installment; installed LAF-after |

Definitions: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision (ICD-10): T814, T845-T847, and T857 was used to identify SSI.

Statistical analysis: Patient characteristics were compared across the groups using descriptive statistics. Simple comparisons of before versus after installation of LF are valid only in the absence of temporal trends in the rate of SSI90. Therefore tested for these trends in each group. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the groups were derived using hierarchical logistic regression, with plenum ventilation acting as the reference group. Models were fitted with and without adjustment for financial year. |

Follow-up period: 90 days

Lost-to-follow-up: Not reported

Control group: All orthopaedic trauma surgery: SSI: 2.4%

Patients undergoing hemiarthroplasty: SSI: 2.6%

Intervention groups: All orthopaedic trauma surgery SSI: LAF group before install: 3.1% LAF group year of install: 3.0% LAF group after install: 2.9% Always LAF: 2.7%

OR after installation (regression analysis): 0.71 (0.46 to 1.09)

Hemiarthroplasty SSI: LAF group before install: 4.3% LAF group year of install: 4.4% LAF group after install: 3.9% Always LAF: 3.8%

OR after installation (regression-analysis): 1.55 (1.17 to 2.00)

OR always LAF (regression analysis): 1.45 (1.17 to 1.80) |

Private hospitals (n=89), those where < 20 hemiarthroplastiesperformed annually (n=67), elective hospitals (n=21), children’shospitals (n=7), treatment centres (n=6), non-orthopaedic hospital (n=1), hospital no longer exists (n=1), invalid hospital code (n=10) were excluded. Therefore, selection bias can not be excluded.

Only early infections were captured by the study design. |

|

Agarwal et al (2017) |

Retrospective matched cohort study |

Our null hypothesis is that patients who had their hip fracture surgery in a mixed-use plenum ventilated theatre have the same infection rate as those operated in an orthopaedic dedicated laminar flow operating theatre. We tested this by comparing the infection rate and other surrogate outcome measures with a matched group. |

No. of Patients: N=159 patients for surgery for a proximal femur fracture. Patients in the “CEPOD” group were preceded by drainage of an abscess, laparotomy or other ‘dirty case‘.

Patient characteristics: “CEPOD” group: age: 85.1y gender: 52/74 female

Matched group: age: 84.8y gender: 60/85 female

matching variables: age, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade, abbreviated Mental Test score and residence status

Procedure: Surgery for a proximal femur fracture |

Location: 1 hospital in the UK

Dates: August 2010 and July 2014

Scope: Single centre

N=159 patients (100%) received surgical antibiotic prophylaxis to the standard protocol. |

Control group: Dedicated orthopaedic laminar flow theatre

Intervention (“CEPOD”-group): Shared emergency theatre without laminar flow |

Definitions: Any documentation of wound leakage, treatment with antibiotics and any microbiology culture or swabs from the hip, readmission or reoperation.

Statistical analysis: Chi-square test |

Follow period: At least 6 months

Lost-to-follow-up: Not reported

Control group: dSSI: 1/85 (repeat surgery)

Intervention group: dSSI: 0/74

|

Very limited number of events

No statistical analyses that corrected for known confounders were conducted. |

|

Gruenberg et al. (2004) |

Retrospective cohort study |

To evaluate if the use of ultraclean air technology could decrease the infection rate after posterior spinal arthro-desis with instrumentation |

No. of Patients: TOTAL N=179

Patient characteristics (according to type of operating room, conventional [c] or laminar flow [l]):

Age: 47.3[c] – 40.9y[l]

Females: 51[c]– 72.5%[I]

Preoperative diagnosis: trauma (37%[c]-8%[I]); degenerative conditions (41%[c]-13%[I])

Procedure: Posterior spinal arthrodesis with instrumentation |

Location: Italian Hospital of Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Dates: May 1996 – December 2001

Scope: single centre

All patients received prophylactic intravenous antibiotics: 1 g cephalothin before skin incision and every 6 hours until drains were removed; those allergic to penicillin received 500 mg vancomycin before skin incision and every 12 hours until drains were removed |

Control group: conventional operating room

Intervention: Vertical exponential laminar flow operating room (Exflow 90, Howorth Airtech Ltd., BL, U.K.) in which the surgical team wore total body exhaust gowns (Kimberly Clark Corp., Roswell, GA). |

Definitions: Any patient with positive cultures from wound exploration or aspiration was considered infected. The same criteria were applied in patients with spontaneous dehiscence of incision with purulent drainage, both with or without positive cultures. Not distinguished between superficial or deep wound infection, because this can sometimes be difficult to determinate and they can both depend on intraoperative wound seeding.

Statistical analysis: Discrete variables were analyzed with the chi-squared test whereas continuous, nonparametric data were studied with the Mann-Whitney Utest. A P <0.05 was considered statistically significant. |

Follow-up period: 34.9 [c] - 28.4 months [l]

Lost-to-follow-up: Not reported

Control group: Wound infection (totale SSI): 12.9% (18/139) (calculated from table 1)

Intervention group: Wound infection (totale SSI): 0% (0/40) (calculated from table 1) There were no significant differences between both groups for age, diabetes, steroid therapy, previous surgeries, tumor cases, or previous radiotherapy. The number of levels fused, utilization of allograft, and operative time were significantly higher in the intervention group.

|

Very few events. No multivariate analysis controlling for confounders was conducted. |

|

Exclusie na discussie met werkgroepleden |

||||||||

|

Knobben et al. (2006) |

Before-after study |

The aim of this study was to evaluate whether behavioural and systems measures decrease intraoperative contamination as monitored during 207 total hip or knee replacements. The influence of these measures on subsequent prolonged wound discharge, superficial surgical site infection and deep periprosthetic infection was also investigated during an 18-month follow-up period |

No. of Patients: TKA, THA: N=207

Patient characteristics: not reported

Procedure: total hip or knee arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis |

Location: University Medical Centre Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands

Dates: July 2001 - January 2004

Scope: single centre

All patients received antimicrobial prophylaxis (cefazoline, 1000 mg intravenously) 20 min before the operation |

Control group: original conditions (among other things: old conventional airflow)

Intervention: 1. Correct use of plenum (Instrumentation unpacking in plenum ventilation alone, Instrumentation unpacking just before surgery, Instrumentation never leaves plenum, else considered unsterile, Head of patient always out of plenum) Old conventional airflow

2. Work up in preparation room, not in operating room (Anaesthetic work up, Shaving, Putting on blood bands and blankets, Positioning patient with leg support), Proper wearing of body coverage (No hair visible, No nose visible, Beard mask and safety glasses for people working in plenum, Renew mouth mask after every operation, Change clothes each time after leaving the operating complex) Limiting needless activity (Number of people in operating room kept to minimum, Opening of doors kept to minimum, Use only smallest door to washing room, Movement of people kept to minimum, No changing of personnel during an operation, If other equipment necessary, use intercom, All communication with world outside via intercom, Only conversation if needed for surgery) New laminar airflow |

Definitions: SSI definition of the Surgical Infection Study Group. This definition relies solely on clinical observations in the absence of microbiological confirmation; dSSI defined by an increase of infection parameters caused by the prosthesis site, as judged by the orthopaedic surgeon.

Statistical analysis: Pearson’s Chi-square test for categorical data was used to test differences between the experimental groups and the control group when all cells of the contingency table contained at least five people. Otherwise, Fisher’s Exact test was used. |

Follow-up period: 18 months

Lost-to-follow-up: None

Control group: superficial SSI: eight 11.4% (8/70)

deep periprosthetic infection: 7.1% (5/70)

Intervention group 1: superficial surgical site infection: 14.9% (10/67)

deep periprosthetic infection: 4.5% (3/67)

Intervention group 2: superficial surgical site infection: 1.4% (1/70)

deep periprosthetic infection: 1.4% (1/70) |

Limited number of events for outcome measure deep prosthetic infection.

No statistical analyses that corrected for known confounders were conducted.

|

|

Simsek Yavuz et al. (2006) |

Prospective cohort study |

To determine the incidence of and identify risk factors for sternal surgical site infection (SSI). |

No. of Patients: TOTAL N=991 CABG (n=748), other cardiac surgery (n=243)

Patient character-istics (according to presence [p] or absence [a] of SSI): Age: 56y [p]–57y [a]

Females: 46% [p]-27% [a]

BMI: 26 (both]

ASA 3 or 4: 68% [p]-58% [a]

Procedure: Cardiac surgery with sternotomy |

Location: Siyami Ersek Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery Hospital (Uskudar, Turkey)

Dates: January 1, 2002 - June 1, 2002

Scope: single centre

For antimicrobial prophylaxis, patients were given cefazolin (1 g every 8 hours) or, for patients who had hypersensitivity or suspected colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin (1 g twice per day); prophylaxis was started at the induction of anesthesia and stopped 24-48 hours after the operation. |

Control group: plenum ventilation (which includes a positive pressure air supply from clean to less clean areas, with a total of 27 changes of high-efficiency filtered air per hour. Although the doors of the older operating theaters were automatic, they did not function properly any more and were generally left open.

Intervention: laminar-flow ventilation systems. The doors of the newer operating theaters were automatic and were always kept closed except, occasionally, when there was movement through them.

|

Definitions: SSI was defined according to the criteria established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Statistical analysis: Comparison of means was done with Student’s t test. For categorical variables, the x2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used. Risk factors for sternal SSI were investigated by logistic regression analysis. All variables with a P value of <0.05 in the univariate analysis or that have been shown to be a risk factor for sternal SSI in the literature were included in logistic regression analysis. Discrete variables (eg, use of inotropic agents) were entered into the analysis only if they were present prior to the occurrence of the sternal SSI. Similarly, continuous variables (eg, duration of mechanical ventilation) were entered into the analysis according to duration of patient exposure to these variables before the onset of sternal SSI. |

Follow-up period: 3 months

Lost-to-follow-up: (9 patients died within 4 days after surgery)

Control group: Sternal SSI: 6.7% (30/445) (calculated from table 1)

Intervention group: Sternal SSI: 2.0% (11/546) (calculated from table 1)

Results from logistic regression analysis:

Surgery in older operating theater: OR=3.46 (95% CI: 1.72-7.11) controlled for other indepently associated factors: female sex, diabetes mellitus, duration of surgery > 5hr., and second surgery required

|

Some flaws in statistical procedures (p value in univariate analysis as a selection criterion for logistic regression was set too low).

|

|

Van Griethuysen 1996 |

Before-after study |