Indicaties CT-scan hersenen kinderen

Uitgangsvraag

Welke kinderen komen in aanmerking voor een CT-scan hersenen na licht THL in de acute fase?

Aanbeveling

Bij kinderen < 2 jaar: Maak een CT-scan hersenen bij presentatie op de SEH < 24 uur na licht THL met minimaal 1 van de volgende symptomen:

- EMV-score < 15 (zie Tabel Pediatrische EMV-score)

- Verwardheid, agitatie, somnolentie

- Palpabele schedelfractuur

- Neurologische uitvalsverschijnselen

- Posttraumatisch epileptisch insult

Bij kinderen < 2 jaar: Maak een CT-scan hersenen of neem een kind op bij presentatie < 24 uur na licht THL bij minimaal 1 van de volgende symptomen:

- Gevaarlijk traumamechanisme (val vanaf > 1 meter, ‘focaal high impact’, hoogenergetisch traumamechanisme* etc.)

- Bewustzijnsverlies ≥ 5 seconden

- Schedelhematoom pariëtaal/temporaal/occipitaal

- Afwijkend gedrag volgens ouders (dit kan zowel een verandering zijn in bewustzijn als gedrag)

- Stollingsstoornissen**

*Onder hoogenergetisch traumamechanisme (HET) wordt verstaan: Hoog risico auto-ongeval (> 30cm indeuking aan zijde slachtoffer; > 45cm indeuking op andere plaats; uit voertuig geslingerd; overlijden in zelfde compartiment; telemetrie data passend bij ernstig letsel). Auto versus voetganger/fietser. Bestuurder/berijder gescheiden van transport medium met significante impact (bijv. motorfiets, paard). Overig trauma met vergelijkbare energie overdracht waar bij een leeftijd < 2 jaar een val van > 1m ook als een HET kan worden beschouwd.

Overweeg opname of een CT-scan als er geen ooggetuige van het trauma of bij onduidelijke toedracht. Dit is een toevoeging aan de PECARN-beslisregel.

Kies laagdrempelig voor een CT-scan hersenen als er meerdere van bovenstaande symptomen zijn, met name wanneer tijdens observatie het kind achteruitgaat en wanneer het kind jonger dan 3 maanden is.

Bij kinderen 2 jaar t/m 15 jaar: maak een CT-scan hersenen bij presentatie op de SEH < 24 uur na licht THL met minimaal 1 van de volgende symptomen:

- EMV-score < 15 (zie Tabel Pediatrische EMV-score)

- Verwardheid, agitatie, somnolentie

- Tekenen van schedelbasisfractuur

- Neurologische uitvalsverschijnselen

- Posttraumatisch epileptisch insult

Bij kinderen 2 jaar t/m 15 jaar: maak een CT-scan hersenen of neem een kind op bij presentatie < 24 uur na licht THL bij minimaal 1 van de volgende symptomen:

- Braken (2 of meer episodes)

- Gevaarlijk traumamechanisme (val vanaf > 1 meter, focaal high impact, hoogenergetisch traumamechanisme etc.)

- Ernstige hoofdpijn

- Bewustzijnsverlies

- Stollingsstoornissen**

Kies laagdrempelig voor een CT-scan hersenen als er meerdere van bovenstaande symptomen zijn of wanneer symptomen verslechteren of het kind achteruitgaat tijdens observatie.

Indien het traumamechanisme niet voldoende verklarend is voor de letsels of het traumamechanisme niet passend is bij de ontwikkelingsleeftijd van het kind overweeg dan ook een CT-scan hersenen.

Gebruik de flowcharts om te bepalen of een CT-scan hersenen gewenst is.

**Overleg altijd met een kinderarts-hematoloog als een kind een stollingsstoornis heeft of stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie gebruikt.

Vermijd de ogen en het halsgebied bij het maken van een CT-scan hersenen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een systematische literatuuranalyse uitgevoerd naar de verschillende beslisregels voor het verrichten van een CT-scan hersenen bij kinderen met een licht THL in de acute fase. Naar mening van de werkgroep is het belangrijk om een beslisregel toe te passen, enerzijds om te zorgen voor uniformiteit van beleid, anderzijds om zorgverleners in de acute fase te ondersteunen in de besluitvorming omtrent het maken van een CT-scan hersenen.

De vraag welke beslisregel de voorkeur heeft, is een afweging van factoren. Er wordt enerzijds gestreefd naar een zo hoog mogelijke sensitiviteit, echter dit dient te worden afgewogen tegen het aantal kinderen dat een CT-scan hersenen (en dus straling) moet ondergaan. Voor het detecteren van afwijkingen waarvoor neurochirurgisch ingrijpen nodig is, dient de sensitiviteit zeer hoog te zijn (95%-100%), omdat het missen hiervan naar verwachting negatieve gezondheidseffecten heeft voor het kind. Wanneer het gaat om het opsporen van intracraniële afwijkingen in het algemeen, is het belang van een sensitiviteit van 100% minder groot, omdat dit vaak geen directe behandelconsequenties heeft voor het beleid op korte termijn, maar wel van invloed is op opnamebeleid. Bovendien zijn intracraniële afwijkingen wel degelijk geassocieerd met nadelige gevolgen op de lange termijn (Gardner, 2019; Königs, 2019). Er is geen definitie van relevante intracraniële afwijkingen, dit moet beschouwd worden als een kennislacune.

Op grond van de literatuur blijken twee beslisregels een sensitiviteit van 100% te hebben wanneer er gekeken wordt naar het opsporen van afwijkingen waarvoor neurochirurgisch ingrijpen geïndiceerd is, namelijk de UCD en de PECARN. Hierbij ligt de specificiteit voor UCD weliswaar iets hoger dan voor PECARN, maar het verschil is marginaal (0,65 vs. 0,59-0,61). Dit betekent dat bij gebruik van PECARN er verhoudingsgewijs bij iets meer kinderen een CT-scan hersenen gemaakt wordt, zonder dat dit leidt tot neurochirurgisch ingrijpen. Echter, de criteria om een CT-scan hersenen te maken zijn voor beide beslisregels op enkele factoren na vergelijkbaar. Wanneer er beoordeeld wordt op ‘level of evidence’, dan blijkt deze het hoogst te zijn bij de CATCH beslisregel. Bij deze beslisregel ligt de sensitiviteit echter beduidend lager (0,75-1), evenals de specificiteit (0,4 en 0,8).

Wanneer de UCD- en PECARN-beslisregels worden vergeleken met betrekking tot het detecteren van intracraniële afwijkingen, dan ligt de sensitiviteit in combinatie met de specificiteit het hoogst bij de PECARN (≥2 jaar sens 0,95-1, spec 0,46-0,8; < 2 jaar sens 0,87-1, spec 0,54-0,71). Hierbij is ‘level of evidence’ geduid als moderate. De sensitiviteit van de UCD verschilt weliswaar weinig (0,91 – 1,0), maar de specificiteit is opvallend lager (0,12 - 0,43). Bovendien is de PECARN-beslisregel in meer verschillende studies gevalideerd.

Daarnaast is er door Abid in 2021 een studie verricht waarbij de diagnostische impact van de PECARN-beslisregel onderzocht is. In deze studie werd de uitkomst bekeken van 1081 kinderen die wel en niet in aanmerking kwamen voor een CT-scan hersenen op basis van de CT-criteria. Hieruit bleek dat slechts bij 1 van de 514 kinderen (0.19%) die niet in aanmerking kwam voor een CT-scan hersenen alsnog sprake was van klinisch relevant hersenletsel.

De PECARN is een beslisregel welke gemakkelijk toepasbaar is in de Nederlandse situatie. Deze beslisregel berekent op basis van symptomen zoals EMV-score < 15, braken of bewustzijnsverlies, het risico op klinisch relevant traumatisch hersenletsel. Er wordt hierbij nog altijd onderscheid gemaakt tussen kinderen jonger dan 2 jaar en vanaf 2 jaar en er kan in bepaalde situaties gekozen worden voor óf een CT-scan hersenen óf opname ter observatie. Deze PECARN is gezien de combinatie van hoge sensitiviteit en relatief hoge specificiteit naar mening van de werkgroep de beste keuze uit de bestaande beslisregels.

Doordat we in de huidige richtlijn deze beslisregel toepassen zullen de CT-criteria enigszins anders zijn dan in de vorige richtlijn uit 2010: Er wordt in de huidige richtlijn alleen nog maar onderscheid gemaakt in kinderen jonger dan 2 jaar en vanaf 2 jaar. Er wordt geen apart onderscheid meer gemaakt in kinderen vanaf 6 jaar.

De werkgroep vindt het wel nodig om enkele verduidelijkingen aan te geven. In de vorige richtlijn werd bij kinderen jonger dan 2 jaar bij afwezigheid van ooggetuige of bij trauma van onduidelijke toedracht geadviseerd een CT-scan hersenen te maken of te kiezen voor een opname. Deze criteria komen niet terug in de PECARN-beslisregel. Ook de aanwezigheid van neurologische uitvalsverschijnselen of een doorgemaakt posttraumatisch insult staan niet expliciet genoemd. De werkgroep is van mening dat dit desalniettemin belangrijke criteria zijn en voegen deze dan ook toe in de CT-aanbevelingen. De CT-criteria zijn weergegeven in een flowchart.

In de PECARN-beslisregels wordt gesproken over een gevaarlijk trauma mechanisme. Naar de mening van de werkgroep vallen onder dit begrip zowel een hoogenergetisch traumamechanisme (HET) als een focaal high impact letsel. Bij een HET is er sprake van hoge energieoverdracht waardoor intracraniële afwijkingen of andere (inwendige) letsels kunnen optreden. Een strikte definitie is niet te geven. Voorbeelden genoemd in de PECARN-beslisregels zijn: enkele ongevalsmechanismen (zoals gemotoriseerd voertuig versus voetganger of fietser zonder helm, uit auto geslingerd). De werkgroep beschouwd een val vanaf > 1m bij kinderen als een gevaarlijk trauma mechanisme. Dit een afwijkingen van de PECARN-beslisregels waarbij een hoogte vanaf 1.5m bij kinderen > 2 jaar als risicofactor wordt beschouwd. De PECARN calculator app is hierdoor niet optimaal betrouwbaar.

Onder focaal high impact letsel wordt bijvoorbeeld verstaan: uitwendig zichtbaar letsel ten gevolge van een klap met een knuppel of fles op het hoofd, een golf/hockeybal met hoge snelheid tegen het hoofd.

Wat betreft het optreden van braken kan braken ook een uiting zijn van pijn of schrik. Daarom heeft de werkgroep besloten dat meerdere keren braken (2 of meer) kan beschouwd worden als een risicofactor bij kinderen van ³2 jaar. Dit is ook in overeenstemming met de gereviseerde NICE richtlijn Assessment of Head Injury 2023.

Bij neonaten en zuigelingen jonger dan 3 maanden kunnen ondanks intracranieel letsel weinig waarneembare symptomen hebben, en de werkgroep is van mening dat er laagdrempelig voor een CT-scan hersenen moet worden gekozen als er meerdere risicofactoren zijn of wanneer de zuigeling tijdens de observatie achteruitgaat.

Het gebruik van stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie of bestaande stollingsstoornissen wordt niet meegenomen in de bestaande beslisregels. Dit omdat dit bij kinderen zelden voorkomt en hier bij kinderen geen literatuur over bestaat. In het geval dat een kind toch een stollingsstoornis heeft of stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie gebruikt is ons advies altijd te overleggen met een kinderarts-kinderhematoloog om het risico op intracraniële afwijkingen of neurochirurgisch ingrijpen in te schatten en op basis hiervan te beslissen wel of geen CT-scan hersenen te maken. De werkgroep heeft daarom besloten om stollingsstoornissen als aparte risicofactor toe te voegen aan het flowdiagram.

Tot slot moet worden vermeld dat bij verdenking op niet accidenteel letsel (2016) het advies is om bij kinderen een MRI-scan hersenen (en myelum) in de subacute fase te verrichten om hiermee eerder ontstane traumatische (axonale) schade te kunnen aantonen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het is niet wenselijk en vaak niet goed mogelijk om de beslissing omtrent het maken van CT-scan hersenen bij het kind of zijn of haar ouders/verzorgers neer te leggen, omdat deze – zeker in een acute situatie- niet in staat zijn deze beslissing te overzien. In de praktijk hebben ouders/verzorgers vaak de wens dat er een CT-scan hersenen gemaakt wordt vanwege zorgen dat er traumatische afwijkingen zijn in de hersenen van hun kind. Echter, het is belangrijk hierin de beslisregel te volgen om zo onnodige stralingsbelasting te voorkomen. Het is belangrijk om een goede uitleg te geven over de overwegingen om een CT-scan te maken of juist waarom deze niet is verricht. Dit kan goed aan ouders uitgelegd worden. Samenspraak met de ouders is mogelijk wanneer er een keuze is om een CT-scan hersenen te maken of een kind ter observatie op te nemen op basis van aanwezige risicofactoren. Wanneer symptomen toenemen of het kind achteruitgaan tijdens SEH-observatie, dan kan de clinicus ervoor kiezen om toch een CT-scan hersenen te maken.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Het aantal CT-scans hersenen dat gemaakt wordt bij kinderen met licht THL is de laatste jaren steeds verder toegenomen, evenals de kosten die daarmee gepaard gaan. Het terugbrengen van deze kosten – bij kwalitatief gelijkblijvende zorg– is essentieel. Dit is de reden dat er bij de keuze voor een beslisregel niet alleen rekening is gehouden met de sensitiviteit van de verschillende beslisregels, maar ook met de specificiteit. Hierdoor wordt gepoogd het aantal onnodige scans zo laag mogelijk gehouden. De criteria die binnen de verschillende onderzochte beslisregels gebruikt worden zijn echter voor een deel anders dan de criteria die in de vorige versie van deze richtlijn gebruikt werden. Het is dan ook niet goed te voorspellen of deze nieuwe richtlijn daadwerkelijk tot een vermindering van het aantal CT-scans hersenen (en de begeleidende kosten) zal leiden. Een Nederlandse multicenter studie (Niele, 2020) heeft wel laten zien dat toepassing van PECARN-regels in de Nederlandse situatie zou kunnen leiden tot een aanzienlijke reductie van verrichtte CT-scan hersenen bij kinderen. Ook werd gevonden dat bij de keuze tot observatie of een CT-scan hersenen bij 81% gekozen wordt voor observatie. Het is niet duidelijk of dit beleid vervolgens gaat leiden tot meer opnames en dit moet worden beschouwd als een kennislacune.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De PECARN-beslisregel die aangehouden wordt in deze richtlijn is makkelijk toepasbaar, er is nog wel onderscheid in CT-criteria voor kinderen < 2 jaar en ≥ 2 jaar. Echter in de vorige richtlijn bestonden er daarbij nog aparte CT-criteria voor kinderen vanaf 6 jaar. Dit is in deze richtlijn achterwege gelaten omdat de PECARN-beslisregel toepasbaar is tot de leeftijd van 18 jaar. In deze richtlijn wordt de beslisregel toegepast t/m de leeftijd van 16 jaar, vanaf 16 jaar wordt de volwassenen module aangehouden (Module Indicaties CT-scan hersenen volwassenen).

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de diagnostische procedure

De werkgroep is – op basis van een systematisch onderzoek van de beschikbare literatuur – van mening dat de PECARN-beslisregel de beste keuze is voor de besluitvorming omtrent het uitvoeren van CT-scans hersenen bij kinderen met licht THL. Hierbij spelen de sensitiviteit, de specificiteit en de mate van validatie een rol. Een bijkomend voordeel is dat de PECARN-beslisregel onderscheid maakt tussen kinderen < 2 jaar en ≥ 2 jaar. Zie ook flowchart voor te bepalen of een CT-scan hersenen gewenst is.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Indien beeldvorming in de acute fase van licht THL bij een kind gewenst is, zal in eerste instantie een CT-scan hersenen verricht worden. Het doel is om intracraniële afwijkingen te detecteren en te beoordelen of er een indicatie bestaat voor neurochirurgisch ingrijpen. Vroege detectie kan leiden tot betere begeleiding of eerdere interventie met een betere uitkomst. De beslisregels over de indicatie voor een CT-scan hersenen zijn gebaseerd op risicofactoren die zijn geassocieerd met de noodzaak tot neurochirurgisch ingrijpen en het optreden van intracraniële afwijkingen die leiden tot medisch beleid (opname, observaties, medicatie, poliklinische follow-up). Bij kinderen moet het risico op intracraniële afwijkingen echter afgewogen worden tegen de stralingsbelasting die een CT-scan hersenen met zich meebrengt. Het is de vraag in welke situatie een CT-scan hersenen (en de bijkomende stralingsbelasting) gerechtvaardigd is. Uit onderzoek is gebleken dat de vorige richtlijn resulteerde in het maken van te veel CT-scans (Lenstra 2017, Niele, 2019). Daarnaast was een knelpunt dat in de vorige richtlijn een indeling in drie leeftijdscategorieën is gemaakt met verschillende risicofactoren per leeftijdscategorie. De vraag is of deze indeling nog moet worden aangehouden. Voor kinderen is de leeftijd tot 16 jaar aangehouden. Vanaf deze leeftijd geldt de module CT-scan hersenen volwassenen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Neurosurgery

1. University of California – Davis (UCD) rule; 2. The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II (NEXUS II); 3. Children's Head injury Algorithm for the prediction of Important Clinical Events (CHALICE) rule; 4. Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) rule

|

Low GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the UCD, NEXUS II, CHALICE and the PECARN may be accurate for predicting neurosurgery.

Sources: Klemetti, 2009; Oman, 2006. |

5. Canadian Assessment of Tomography for Childhood Head injury (CATCH) rule

|

Moderate GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the CATCH is likely accurate for predicting neurosurgery (sensitivity range 0.75 – 1.00; specificity range 0.54 – 0.85).

Sources: Babl, 2017; Easter, 2014; Osmond, 2006; Osmond, 2018. |

Intracranial injury

1. University of California – Davis (UCD) rule

|

Moderate GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the UCD is likely accurate for predicting intracranial injury (sensitivity range 0.91 – 1.00; specificity range 0.09 – 0.45).

Sources: Klemetti, 2009; Palchak, 2003; Sun, 2007. |

2. The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II (NEXUS II)

|

Low GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the UCD may be accurate for predicting intracranial injury.

Sources: Klemetti, 2009; Oman, 2006. |

3. Children's Head injury Algorithm for the prediction of Important Clinical Events (CHALICE) rule

|

Moderate GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the CHALICE is likely accurate for predicting intracranial injury (sensitivity range 0.64 – 0.98; specificity range 0.05 – 0.87).

Sources: Babl, 2017; Dunning, 2006; Easter, 2014; Klemetti, 2009; Thiam, 2016. |

4. Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) rule

|

Moderate GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the PECARN is likely accurate for predicting intracranial injury in children < 2 yrs (sensitivity range 0.97 – 1.00; specificity range 0.54 – 0.71). and in children 2-18 yrs (sensitivity range 0.95 – 1.00; specificity range 0.46 – 0.72).

Sources: Babl, 2017; Bozan, 2019; Easter, 2014; Ide, 2020; Kuppermann, 2009; Kuppermann, 2009 (2); Lorton, 2016; Schonfeld, 2014; Thiam, 2015. |

5. Canadian Assessment of Tomography for Childhood Head injury (CATCH) rule

|

Moderate GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the CATCH is likely accurate for predicting intracranial injury (sensitivity range 0.47 – 1.00; specificity range 0.45 – 0.84).

Sources: Babl, 2017; Bozan, 2019; Easter, 2014; Osmond, 2006; Osmond, 2018; Thiam, 2015. |

Diagnostic impact studies

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the impact of the PECARN on clinically important brain injury, traumatic brain injury on CT and skull fracture in patients with mTBI within 48h after the accident.

Source: Abid, 2021 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found about the impact of the CHALICE, CATCH, UCD and NEXUS-II on patient important outcomes after mTBI within 48h after the accident.

Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

a. Diagnostic performance studies

Pandor (2011) described a systematic review about the diagnostic accuracy of clinical decision rules and individual characteristics for predicting intracranial injury, including need for neurosurgery in adults and children with mTBI. Also, a cross-sectional survey was performed to compare current practice in the NHS and an economic model was developed to estimate cost-effectiveness. A systematic literature search was performed in several electronic databases from inception to April 2009 and was updated in March 2010. Studies were included if 1) cohort studies included mTBI patients from which clinical decision rules were compared to a reference standard test; 2) controlled trials compared alternative strategies for mTBI. Methodological quality was assessed by the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies tool or criteria recommended by the Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group. In total, 93 papers were included in the systematic review. In the analyses, the diagnostic accuracy of individual clinical characteristics, biomarkers and clinical decision rules were assessed. In order to answer the question of this module, only the published clinical decision rules for identifying intracranial injury or the need for neurosurgery in children were extracted (n=14).

Babl (2017) performed a prospective cohort study on the diagnostic performance of the PECARN, CATCH and CHALICE head injury decision rules in children with head injury of any severity (n=20137).

Shavit (2019) performed a multicenter cohort study on the diagnostic performance of the PECARN rule and the Isreali Decision Algorithm for Identifying traumatic brain injury in children (IDITBIC) in children with a Glasgow coma score of <15 (n=18913).

Bozan (2019) performed a prospective cohort study on the diagnostic performance of the PECARN and CATCH clinical decision rules for identifying intracranial injury (defined as scalp fracture and/or intracranial bleeding) in children <18 years with an isolated blunt head trauma (GCS >13; n=256)

Easter (2014) performed a prospective cohort study on the diagnostic performance of the PECARN, CHALICE and CATCH decision rules for identifying intracranial injury (any injury on CT) and the need for neurosurgical intervention in children with a minor head injury (n=1062).

Ide (2020) performed a prospective cohort study on the diagnostic performance of the PECARN decision rule for identifying intracranial injury (clinically important traumatic brain injury) in children <16 with minor head trauma (n=6585).

Lorton (2016) performed a multicenter prospective study on the diagnostic performance of the PECARN decision rule for identifying intracranial injury (clinically important brain injury) in children <16 years who presented at the emergency department within 24h after a blunt head trauma (n=1499).

Osmond (2018) performed a multicenter cohort study on the diagnostic performance of the CATCH decision rule for identifying intracranial injury (brain injury on CT) and need for neurosurgical intervention in children with blunt head trauma and GCS 13-15 (n=4060).

Schonfeld (2014) performed a cross-sectional study on the diagnostic performance of the PECARN decision rule for identifying intracranial injury (clinically important traumatic brain injury) in children with minor blunt head trauma (n=2428)

Thiam (2015) performed a prospective observational cohort study on the diagnostic performance of the CATCH, CHALICE and PECARN decision rules for identifying intracranial injury (positive head CT finding) in children <16 years presenting complaints of head injury in the emergency department within 72 hours after injury (n=1179).

b. Diagnostic impact studies

Abid (2021) performed a secondary analysis of a prospective observational study about the impact of the PECARN decision rule by comparing patients who met the PECARN low-risk criteria for CT to patients who did not meet the PECARN low-risk criteria for CT (n=1081). The effects were evaluated on clinically important brain injury, traumatic brain injury on CT and skull fracture on CT.

c. Association studies

In total, three observational studies assessed the association between individual clinical (baseline) variables and presence of intracranial injury or the need for neurosurgical intervention in order to determine whether CT scanning is needed.

Di (2017) performed a retrospective study to identify the independent predictors of intracranial injuries in infants younger than 2 years old with mTBI (n=214). The results showed that characteristics of scalp hematomas and mechanism of injury were associated with intracranial injuries.

Obuchi (2017) performed a retrospective study to identify clinical predictors of intracranial injuries in infants <11 months with minor head trauma (n=549). Results showed that fall height, size and location of scalp hematoma were associated with intracranial injuries.

Bozan (2019) performed a prospective cohort study to determine computerized brain tomography indications for children <18 years that were referred to. The emergency department with minor blunt head trauma (n=256). The results showed that the indications from the PECARN decision rule and the CATCH decision rule were effective for determining the necessity of a computerized brain tomography in children with minor blunt head trauma.

Results

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selected clinical decision rules were shown in table 1.

Table 1. Inclusion- and exclusion criteria per clinical decision rule

|

Clinical decision rule |

Inclusion criteria |

Exclusion criteria |

|

Children's Head injury Algorithm for the prediction of Important Clinical Event |

Patients aged <16y with any history or signs of injury to the head. |

Refusal to consent. |

|

Canadian Assessment of Tomography for Childhood Head injury |

Patients aged <17y with all the following: initial GCS at least 13, injury within 24 hrs, blunt trauma with witnessed LOC, amnesia, witnessed disorientation, vomiting 2+ times at least 15 mins apart, persistent irritability if under 2 years old |

Penetrating skull injury, depressed skull fracture, focal neuro deficit, developmental delay, child abuse, re-eval after prior head injury, pregnant patient. |

|

Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network |

Patients aged <18y present with 24h of head injury. |

Trivial mechanism defined by ground-level fall or walking or running into stationary objects and no signs or symptoms of head trauma other than scalp abrasions and lacerations; Penetrating trauma; Known brain tumors; Pre-existing neurological disorder complicating assessment; Neuroimaging at an outside hospital before transfer; Patient with ventricular shunt; Patient with bleeding disorder; GCS <14. |

|

University of California–Davis rule |

Patients aged <18y presenting to the pediatric ED after a history of nontrivial blunt head trauma with historical or physical examination findings consistent with head trauma. |

Not applicable. |

|

National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study II |

All blunt trauma patients undergoing cranial CT. |

Patients with penetrating trauma, those with delayed presentations (greater than 24 hours after injury), patients undergoing imaging for reasons unrelated to trauma.

|

a. Diagnostic performance studies

An overview of the clinical factors included in the selected clinical decision rules is presented in Table 2. Figure 1-11 show the diagnostic accuracy for each clinical decision rule.

Table 2. Overview of clinical factors included in clinical decision rules for requirement of head CT

|

|

CHALICE |

CATCH (high risk) |

CATCH (medium risk) |

UCD |

NEXUS-II |

PECARN < 2 yrs |

PECARN ≥ 2 yrs |

|

GCS score |

<14 or <15 when aged <1 |

<15 at 2 hrs after injury |

|

|

|

<15 |

<15 |

|

Vomiting |

>2 |

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dangerous mechanism of injury |

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

Headache |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

Injury above clavicles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Posttraumatic seizure |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coagulopathy |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Focal neurological deficit |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Loss of consciousness |

>5 min |

|

|

|

|

≥5 min. |

any/suspected |

|

Scalp hematoma |

|

|

X |

in children ≤2 years |

X |

X |

|

|

Altered level of alertness |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Abnormal behaviour/ mental status |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

Any sign of basal skull fracture |

X |

|

X |

xX |

X |

|

X |

|

Suspected open or depressed skull fracture |

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Persistent anterograde amnesia |

>5 min |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Drowsiness |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-accidental injury suspicion |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Facial crepitus/serious facial injury |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bruise, swelling or laceration |

>5 cm if <1y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Irritability on examination |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not acting normally |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Other signs of altered mental status |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

Palpable or unclear skull fracture |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

1. University of California – Davis (UCD) rule

Neurosurgery

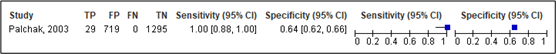

For neurosurgery, sensitivity of the UCD rule was 1.00 (95% CI 0.88 – 1.00). Specificity was 0.64 (95% CI 0.62 – 0.66). Results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Sensitivity and specificity of the UCD rule for neurosurgery.

Intracranial injury

For intracranial injury, sensitivity of the UCD rule ranged between 0.91 and 1.00 (95% range was 0.84 - 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.12 and 0.43 (95% CI range was 0.09 – 0.45). Results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Sensitivity and specificity of the UCD rule for intracranial injury.

2. The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II (NEXUS II)

Neurosurgery

For neurosurgery, sensitivity nor specificity of the NEXUS-II was assessed.

Intracranial injury

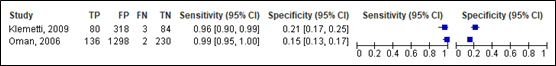

For intracranial injury, sensitivity of the NEXUS II ranged between 0.96 and 0.99 (95% CI range 0.90 – 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.15 and 0.21 (95% CI range 0.13 – 0.25). Results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Sensitivity and specificity of the NEXUS II for intracranial injury

3. Children's Head injury Algorithm for the prediction of Important Clinical Events (CHALICE) rule

Neurosurgery

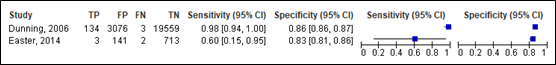

For neurosurgery, sensitivity of the CHALICE ranged between 0.60 and 0.98 (95% CI range was 0.15 and 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.83 and 0.86 (95% CI range was 0.81 and 0.87). Results are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Sensitivity and specificity of the CHALICE rule for neurosurgery

Intracranial injury

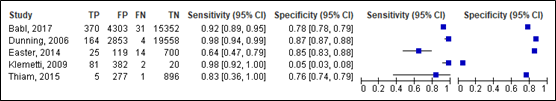

For intracranial injury, sensitivity of the CHALICE ranged between 0.64 and 0.98 (95% CI range was 0.36 – 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.05 and 0.87 (95% CI range was 0.03 – 0.88). Results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Sensitivity and specificity of the CHALICE rule for intracranial injury

4. Paediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) rule

Neurosurgery (≥ 2 years, < 18 years)

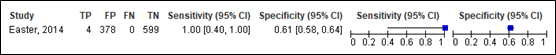

For neurosurgery, sensitivity of the PECARN in children aged between 2 and 18 years was 1.00 (95% CI of 0.40 – 1.00). Specificity was 0.61 (95% CI of 0.58 – 0.64). Results are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Sensitivity and specificity of the PECARN rule for neurosurgery

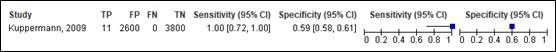

Neurosurgery (> 2 years)

For neurosurgery, sensitivity of the PECARN in children aged < 2 was 1.00 (95% CI 0.71 – 1.00). Specificity was 0.59 (95% CI 0.58 – 0.61). Results are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Sensitivity and specificity of the PECARN rule for neurosurgery

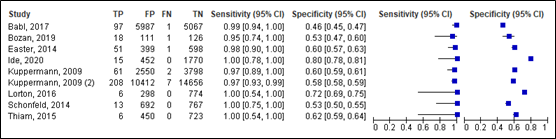

Intracranial injury (≥ 2 years, < 18 years)

For intracranial injury, sensitivity of the PECARN rule in children aged between 2 and 18 years ranged between 0.95 and 1.00 (95% CI range was 0.54 – 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.46 and 0.80 (95% CI range was 0.45 – 0.81). Results are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Sensitivity and specificity of the PECARN rule for intracranial injury

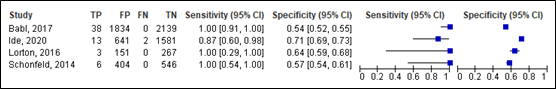

Intracranial injury (< 2 years)

For intracranial injury, sensitivity of the PECARN rule in children aged < 2 years ranged between 0.87 and 1.00 (95% CI range was 0.20 – 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.54 (95% CI range was 0.52 – 0.73). Results are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Sensitivity and specificity of the PECARN rule for intracranial injury

5. Canadian Assessment of Tomography for Childhood Head injury (CATCH) rule

Neurosurgery

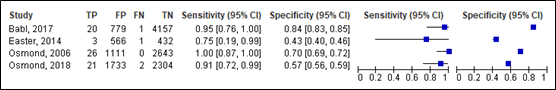

For neurosurgery, sensitivity of the CATCH ranged between 0.75 and 1.00 (95% CI range was 0.19 – 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.43 and 0.84 (95% range was 0.40 – 0.85). Results are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Sensitivity and specificity of the CATCH rule for neurosurgery.

Intracranial injury

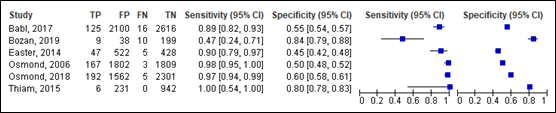

For intracranial injury, sensitivity of the CATCH rule ranged between 0.47 and 1.00 (95% CI range was 0.24 – 0.95). Specificity ranged between 0.43 and 0.84 (95% CI range was 0.42 and 0.88). Results are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Sensitivity and specificity of the CATCH rule for intracranial injury

Level of evidence in the literature

Neurosurgery

The level of evidence in the literature started at high because it was based on diagnostic test accuracy studies. For the CATHCH, the level of evidence was downgraded due to methodological shortcomings only (-1, risk of bias). The final level is moderate. For the UCD, CHALICE, PECARN and the NEXUS-II, the level of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to methodological shortcomings (-1, risk of bias) and low number of included studies (-1, imprecision). The final level is low.

Intracranial injury

The level of evidence in the literature started at high because it was based on diagnostic test accuracy studies. For the UCD, CHALICE, PECARN and te CATHCH the level of evidence was downgraded due to methodological shortcomings only (-1, risk of bias). The final level is moderate. For the NEXUS-II, the level of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to methodological shortcomings (-1, risk of bias) and low number of included studies (-1, imprecision). The final level is low.

Conclusions

Neurosurgery

1. University of California – Davis (UCD) rule; 2. The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II (NEXUS II); 3. Children's Head injury Algorithm for the prediction of Important Clinical Events (CHALICE) rule; 4. Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) rule

|

Low GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the UCD, NEXUS II, CHALICE and the PECARN may be accurate for predicting neurosurgery.

Sources: Klemetti, 2009; Oman, 2006. |

5. Canadian Assessment of Tomography for Childhood Head injury (CATCH) rule

|

Moderate GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the CATCH is likely accurate for predicting neurosurgery (sensitivity range 0.75 – 1.00; specificity range 0.54 – 0.85).

Sources: Babl, 2017; Easter, 2014; Osmond, 2006; Osmond, 2018. |

Intracranial injury

- University of California – Davis (UCD) rule

|

Moderate GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the UCD is likely accurate for predicting intracranial injury (sensitivity range 0.91 – 1.00; specificity range 0.09 – 0.45).

Sources: Klemetti, 2009; Palchak, 2003; Sun, 2007. |

- The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II (NEXUS II)

|

Low GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the UCD may be accurate for predicting intracranial injury.

Sources: Klemetti, 2009; Oman, 2006. |

- Children's Head injury Algorithm for the prediction of Important Clinical Events (CHALICE) rule

|

Moderate GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the CHALICE is likely accurate for predicting intracranial injury (sensitivity range 0.64 – 0.98; specificity range 0.05 – 0.87).

Sources: Babl, 2017; Dunning, 2006; Easter, 2014; Klemetti, 2009; Thiam, 2016. |

- Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) rule

|

Moderate GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the PECARN is likely accurate for predicting intracranial injury in children < 2 yrs (sensitivity range 0.97 – 1.00; specificity range 0.54 – 0.71). and in children 2-18 yrs (sensitivity range 0.95 – 1.00; specificity range 0.46 – 0.72).

Sources: Babl, 2017; Bozan, 2019; Easter, 2014; Ide, 2020; Kuppermann, 2009; Kuppermann, 2009 (2); Lorton, 2016; Schonfeld, 2014; Thiam, 2015. |

- Canadian Assessment of Tomography for Childhood Head injury (CATCH) rule

|

Moderate GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the CATCH is likely accurate for predicting intracranial injury (sensitivity range 0.47 – 1.00; specificity range 0.45 – 0.84).

Sources: Babl, 2017; Bozan, 2019; Easter, 2014; Osmond, 2006; Osmond, 2018; Thiam, 2015. |

- Diagnostic impact studies

Abid (2021) showed the impact of the PECARN by comparing patients who did not meet the PECARN low-risk criteria to patients who met the PECARN low-risk criteria on the following clinical outcome measures: clinically important brain injury, traumatic brain injury on CT and skull fracture on CT (n=1081). The differences in incidence were considered clinically relevant in favour of applying the PECARN. Results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Impact of the PECARN low risk criteria on patients’ outcomes (extracted from Abid, 2021)

|

|

Did not meet PECARN Low-Risk Criteria* |

Met PECARN Low-Risk Criteria* |

|

Clinically important brain injury |

24/567 (4.2%) |

1/514 (0.19%) |

|

Traumatic brain injury on CT |

93/436 (21.3%) |

10/197 (5.1%) |

|

Skull fracture on CT |

122/436 (28%) |

9/197 (4.6%) |

* Low-risk criteria include nonsevere mechanism of injury, Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15, absence of the following: other signs of altered mental status, palpable skull fracture, loss of consciousness ≤5 seconds, parental report of acting abnormally, and nonfrontal scalp hematoma.

The diagnostic impact of the CHALICE, CATCH, UCD and NEXUS-II was not assessed.

The level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures started at low because they were based on observational studies. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to methodological shortcomings (-2, risk of bias). The final level is very low.

Conclusions

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the impact of the PECARN on clinically important brain injury, traumatic brain injury on CT and skull fracture in patients with mTBI within 48h after the accident.

Source: Abid, 2021 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found about the impact of the CHALICE, CATCH, UCD and NEXUS-II on patient important outcomes after mTBI within 48h after the accident.

Source: - |

- Association studies

From the three observational studies, the one variable (non-frontal hematoma) was found to be significantly associated with intracranial injury in addition to the criteria that were included in the clinical decision rules. Table 4.4 shows an overview of the included studies assessing clinical variables that are significantly associated with intracranial injury.

There were no clinical variables that were significantly associated with need for neurosurgical intervention.

Table 4. Additional criteria to clinical decision rules for CT scanning

|

Study |

Population |

Analysis |

All criteria significantly associated with outcome |

Criteria significantly associated with outcome, not included in clinical decision rules |

|

Intracranial injury |

||||

|

Di, 2017 |

Infants younger than 2 years old with mild TBI (n=214) |

Multivariate logistic regression analysis |

Mechanism of injury, scalp hematoma. |

- |

|

Obuchi, 2017 |

Infants with minor head trauma (0-11 months old) (n=549) |

Multivariable logistic regression analysis |

Scalp hematoma |

- |

|

Bozan, 2019 |

Children <18 yrs old with isolated blunt head trauma (GCS > 13) (n=256) |

Multivariate regression analyses |

Age, GCS, Non-frontal hematoma |

Non-frontal hematoma |

Abbreviations: TBI: traumatic brain injury; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence was not assessed because it is a descriptive overview of the literature. No GRADE assessment could be performed since no studies were included with at least internal validation of the prediction models.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the diagnostic accuracy of clinical decision rules for determining whether a CT scan is needed in pediatric patients with mTBI within 48h after the accident for identifying intracranial injury and/or need for neurosurgery?

| P: | Children (< 16 yrs) with mTBI within 48 hours after accident; |

| I: | Clinical decision rules: Children's Head injury Algorithm for the prediction of Important Clinical Events (CHALICE); Canadian Assessment of Tomography for Childhood Head injury (CATCH); Paediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN); University of California–Davis rule (UCD); National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study II (NEXUS II); |

| C: | CT scanning based on coincidence/decision by the doctor; |

| R: | CT scanning applied by all patients; |

| O: | Diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, true positives, false negatives, false positives and true negative) for need for neurosurgery or intracranial injury. |

Timing and setting: emergency physician, radiologist, neurologist within 24 hours after mTBI.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered sensitivity as a critical outcome measure for decision making and specificity as an important outcome measure for decision making. Sensitivity was considered clinically accurate when being as close to 100% as possible. No minimally clinical accuracy of specificity was determined.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched for systematic reviews with relevant search terms from 2000 until August 9th, 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 95 hits.

After selection of the systematic reviews, the observational studies published from 2010 until August 9th, 2022, were added to the results of the search. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. This resulted in an addition of 635 hits.

A total of 47 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 33 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and fourteen studies were included.

Studies were divided into the following categories:

- Diagnostic performance studies about the performance of validated clinical decision rules to identify intracranial injury or neurosurgical intervention.

- Diagnostic impact studies about the impact of applying validated clinical decision rules on patient relevant outcome measures.

- Association studies about the relationship between clinical criteria and intracranial injury or neurosurgical intervention. The level of evidence was not assessed because it is a descriptive overview of the literature. No GRADE assessment could be performed since no studies were included with at least internal validation of the prediction models. Thus, no risk of bias nor evidence tables were included for this part of the literature overview.

Results

Clinical decision rules and additional criteria for CT scanning: Seven studies were included in the analysis of the literature:

- Diagnostic performance studies: One systematic review and nine observational cohort studies.

- Diagnostic impact studies: One observational study.

- Association studies: Three observational studies.

Referenties

- Bozan, Ö., Aksel, G., Kahraman, H. A., Giritli, Ö., & Eroğlu, S. E. (2019). Comparison of PECARN and CATCH clinical decision rules in children with minor blunt head trauma. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery: official publication of the European Trauma Society, 45(5), 849–855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-017-0865-8

- Easter, J. S., Bakes, K., Dhaliwal, J., Miller, M., Caruso, E., & Haukoos, J. S. (2014). Comparison of PECARN, CATCH, and CHALICE rules for children with minor head injury: a prospective cohort study. Annals of emergency medicine, 64(2), 145–152.e1525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.01.030

- Gardner JE, Teramoto M, Hansen C. Factors Associated With Degree and Length of Recovery in Children With Mild and Complicated Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurosurgery. 2019 Nov 1;85(5):E842-E850. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyz140. PMID: 31058994.

- Ide, K., Uematsu, S., Hayano, S., Hagiwara, Y., Tetsuhara, K., Ito, T., Nakazawa, T., Sekine, I., Mikami, M., & Kobayashi, T. (2020). Validation of the PECARN head trauma prediction rules in Japan: A multicenter prospective study. The American journal of emergency medicine, 38(8), 1599–1603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.158439

- Königs M, Pouwels PJ, Ernest van Heurn LW, Bakx R, Jeroen Vermeulen R, Goslings JC, Carel Goslings J, Poll-The BT, van der Wees M, Catsman-Berrevoets CE, Oosterlaan J. Relevance of neuroimaging for neurocognitive and behavioral outcome after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018 Feb;12(1):29-43. doi: 10.1007/s11682-017-9673-3. Erratum in: Brain Imaging Behav. 2019 Aug;13(4):1183. Carel Goslings J [corrected to Goslings JC]. PMID: 28092022; PMCID: PMC5814510.

- Lenstra JJ, Pikstra ARA, Fock JM, Metting Z, van der Naalt J. Influence of guidelines on management of paediatric mild traumatic brain injury: CT-assessment and admission policy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2017 Nov;21(6):816-822. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2017.07.019. Epub 2017 Aug 3. PMID: 28811137.

- Lorton, F., Poullaouec, C., Legallais, E., Simon-Pimmel, J., Chêne, M. A., Leroy, H., Roy, M., Launay, E., & Gras-Le Guen, C. (2016). Validation of the PECARN clinical decision rule for children with minor head trauma: a French multicenter prospective study. Scandinavian journal of trauma, resuscitation and emergency medicine, 24, 98. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-016-0287-3

- <p align="left">Niele N, van Houten MA, Boersma B, Biezeveld MH, Douma M, Heitink K, Ten Tusscher GW, Tromp E, van Goudoever JB, Plötz FB. Multi-centre study found that strict adherence to guidelines led to computed tomography scans being overused in children with minor head injuries. Acta Paediatr. 2019 Sep;108(9):1695-1703. doi: 10.1111/apa.14742. Epub 2019 Mar 4. PMID: 30721540.

- <p align="left">Niele, N., van Houten, M., Tromp, E., van Goudoever, J. B., & Plötz, F. B. (2020). Application of PECARN rules would significantly decrease CT rates in a Dutch cohort of children with minor traumatic head injuries. European journal of pediatrics, 179(10), 1597–1602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-020-03649-w

- Niele N, Plötz FB, Tromp E, Boersma B, Biezeveld M, Douma M, Heitink K, Tusscher GT, van Goudoever HB, van Houten MA. Young children with a minor traumatic head injury: clinical observation or CT scan? Eur J Pediatr. 2022 Sep;181(9):3291-3297. doi: 10.1007/s00431-022-04514-8. Epub 2022 Jun 24. PMID: 35748958; PMCID: PMC9395303.

- Osmond, M. H., Klassen, T. P., Wells, G. A., Davidson, J., Correll, R., Boutis, K., Joubert, G., Gouin, S., Khangura, S., Turner, T., Belanger, F., Silver, N., Taylor, B., Curran, J., Stiell, I. G., & Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) Head Injury Study Group (2018). Validation and refinement of a clinical decision rule for the use of computed tomography in children with minor head injury in the emergency department. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne, 190(27), E816–E822. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170406

- Pandor, A., Goodacre, S., Harnan, S., Holmes, M., Pickering, A., Fitzgerald, P., Rees, A., & Stevenson, M. (2011). Diagnostic management strategies for adults and children with minor head injury: a systematic review and an economic evaluation. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England), 15(27), 1–202. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta15270

- Schonfeld, D., Bressan, S., Da Dalt, L., Henien, M. N., Winnett, J. A., & Nigrovic, L. E. (2014). Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network head injury clinical prediction rules are reliable in practice. Archives of disease in childhood, 99(5), 427–431. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2013-305004

- Shavit, I., Rimon, A., Waisman, Y., Borland, M. L., Phillips, N., Kochar, A., Cheek, J. A., Gilhotra, Y., Furyk, J., Neutze, J., Dalziel, S. R., Lyttle, M. D., Bressan, S., Donath, S., Hearps, S., Oakley, E., Crowe, L., Babl, F. E., & Paediatric Research in Emergency Departments International Collaborative (PREDICT) (2020). Performance of Two Head Injury Decision Rules Evaluated on an External Cohort of 18,913 Children. The Journal of surgical research, 245, 426–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2019.07.090

- Thiam, D. W., Yap, S. H., & Chong, S. L. (2015). Clinical Decision Rules for Paediatric Minor Head Injury: Are CT scans a Necessary Evil? Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 44(9), 335–341.

Evidence tabellen

a. Diagnostic performance studies

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Pandor, 2011 |

SR and meta-analysis of cohort studies.

Literature search up to March, 2010

A: Dunning, 2006 B: Klemetti, 2009 C: Kupperman, 2009 D: Kupperman, 2009 (2) E: Oman, 2006 F: Osmond, 2006 G: Palchak, 2003 H: Sun, 2007

Study design: cohort studies

Setting and Country: UK

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Authors declared no competing interests; Funded by The National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme.

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR: n.r.

8 studies included.

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

Patients with CT (n) A: 772 B: 485 C: 283 D: 8502 E: 1666 F: n.r. G: 2043 H: 283 |

Clinical decision rule

A: CHALICE B: CHALICE, NEXUS-II, UCD C: PECARN, NEXUS-II D: PECARN, NEXUS-II E: NEXUS-II, UCD F: CATCH G: UCD H: UCD

|

Reference standard used for intracranial injury.

A: All patients treated according to RCS guidelines. This recommends admission. for those at high risk and CT scan for those at highest risk B: Hospital records C: CT scans, medical records, and telephone follow-up. D: CT scans, medical records, and telephone follow-up. E: CT scan F: CT scan G: CT or performance of intervention H: CT scan

Reference standard used for neurosurgery: A: n.r. |

Endpoint of follow-up: n.r.

|

Intracranial injury Effect measure: Sensitivity [95% CI] / Specificity [95% CI]

Clinical decision rule: UCD B: 0.99 [0.93 – 1.00] / 0.12 [0.09 – 0.16]

Clinical decision rule: NEXUS II B: 0.96 [0.90 – 0.99] / 0.21 [0.17 – 0.25] E: 0.99 [0.95 – 1.00] / 0.15 [0.13 – 0.17]

Clinical decision rule: CHALICE A: 0.98 [0.94 – 0.99] / 0.87 [0.87 -0.88] B: 0.98 [0.92 – 1.00] / 0.05 [0.03 – 0.08]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN 2-18 years C: 0.97 [0.89 – 1.00] / 60 [0.59 – 0.61]

Clinical decision rule: CATCH F: 0.98 [0.95 – 1.00] / 0.50 [0.48 – 0.52]

Neurosurgery Effect measure: Sensitivity [95% CI] / Specificity [95% CI]

Clinical decision rule: CATCH F: 1.00 [0.87 – 1.00] / 0.70 [0.69 – 0.72]

Clinical decision rule: CHALICE A: 0.98 [0.94 – 1.00] / 0.86 [0.86 – 0.87]

Clinical decision rule: UCD G: 1.00 [0.88 – 1.00] / 0.64 [0.62 – 0.66]

|

Risk of bias A: verification bias and test review bias. |

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention/Control

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Babl, 2017 |

Type of study: Prospective cohort study.

Setting and country: Multicentre, Australia/New Zealand.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The funders of this study had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. FEB, CM, KJ, and SDo had access. to the raw data. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication; We declare no competing interests. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: PECARN <2 yrs: 4011 PECARN ≥ 3 yrs: 11152 CATCH: 4957 CHALICE: 20029

|

|

Length of follow-up: n.r.

Loss-to-follow-up: 10%

Reason: lost to telephone follow-up.

Incomplete outcome data: n.r.

|

Intracranial injury Defined as clinically important traumatic brain injury.

Effect measure: Sensitivity [95% CI] / Specificity [95% CI]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN <2 years 1.00 [0.92 – 1.00] / 0.59 [0.58 – 0.61]

Clinical decision rule PECARN 2-18 years 0.99 [0.95 – 1.00] / 0.52 [0.51 – 0.53]

Clinical decision rule: CATCH 0.92 [0.87 – 0.96] / 0.70 [0.70 – 0.71]

Clinical decision rule: CHALICE 0.93 [0.87 - 0.96] / 0.79 [0.78 – 0.79]

Neurosurgery Defined as

Effect measure: Sensitivity [95% CI] / Specificity [95% CI]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN <2 years 1.00 [0.54 – 1.00] / 0.59 [0.57 – 0.60]

Clinical decision rule PECARN 2-18 years 1.00 [0.82 – 1.00] / 0.52 [0.51 – 0.52]

Clinical decision rule: CATCH 0.96 [0.79 – 1.00] / 0.70 [0.69 – 0.71]

Clinical decision rule: CHALICE 0.92 [0.73 – 1.00] / 0.78 [0.78 – 0.79]

|

Author’s conclusion The sensitivities of three clinical decision rules for head injuries in children were high when used as designed. The findings are an important starting point for clinicians considering the introduction of one of the rules. |

|

Bozan, 2019 |

Type of study: Prospective cohort study.

Setting and country: Single-centre, Turkey.

Funding and conflicts of interest: No competing interests. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 278

Important prognostic factors2: age (IQR): 3 (1 – 7.75) Sex: 59.8% M

Groups comparable at baseline? N.a. |

|

Length of follow-up: n.r.

Loss-to-follow-up: 22 (7.9%)

Incomplete outcome data: n.r.

|

Intracranial injury Defined by scalp fracture and/or intracranial bleeding in CBT.

Effect measure: Sensitivity [95% CI] / Specificity [95% CI]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN 0.95 [0.72 – 1.00] / 0.53 [0.47 – 0.60]

Clinical decision rule: CATCH 0.48 [0.25 – 0.71] / 0.83 [0.79 – 0.88]

|

Author’s conclusion The results of this study show that the implementation of clinical decision rules reduce the number of unnecessary CBT scans. While both PECARN and CATCH were found to be effective in determining the necessity of CBT for children with minor blunt head trauma, PECARN proved to be more useful for emergency services because of its higher sensitivity. The authors suggest that conducting a CBT scan based on clinical decision rules may be a suitable approach for early detection of the presence of intracranial acute pathologies in young children with minor blunt head trauma, GCS score is < 15 and non-frontal hematomas are present. |

|

Easter, 2014 |

Type of study: Prospective cohort study.

Setting and country: Single-centre, Colorado.

Funding and conflicts of interest: Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views. No authors had financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; Funding by JSE (K12HS019464) and JSH (K02HS017526) had financial support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for the submitted work. JSE was also supported by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR001082. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 1526

|

|

Length of follow-up: n.r.

Loss-to-follow-up: n.r.

Incomplete outcome data: n.r.

|

Intracranial injury Defined by any injury on CT.

Effect measure: Sensitivity [95% CI] / Specificity [95% CI]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN 0.98 [0.89 – 1.00] / 0.64 [0.61 – 0.67]

Clinical decision rule: CATCH 0.90 [0.79 – 0.97] / 0.45 [0.42 – 0.48]

Clinical decision rule: CHALICE 0.64 [0.47 – 0.79] / 0.86 [0.83 – 0.88]

Neurosurgery Defined by any injury requiring neurosurgical intervention.

Effect measure: Sensitivity [95% CI] / Specificity [95% CI]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN 1.00 [0.40 – 1.00] / 0.61 [0.58 – 0.64]

Clinical decision rule: CATCH 0.75 [0.19 – 0.99] / 0.43 [0.40 – 0.46]

Clinical decision rule: CHALICE 0.75 [0.19 – 0.99] / 0.84 [ 0.81 – 0.86]

|

Author’s conclusion In summary, for identifying clinically significant TBI in children presenting to an urban paediatric ED for minor closed head injury, PECARN and physician practice were the only approaches to identify all clinically important TBIs, with PECARN being slightly more specific. CHALICE was incompletely sensitive but the most specific of all rules. CATCH was incompletely sensitive and had the poorest specificity of all modalities. |

|

Ide, 2020 |

Type of study: Multicentre prospective study.

Setting and country: Multicentre, Japan.

Funding and conflicts of interest: This work was supported by the Foundation. for Growth Science (26-44) and MEXT KAKENHI JP16K11436; The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 2237

Age: Median (IQR) months <2yrs: 13 (7-18) ≥2yrs: 56 (37-90)

|

|

Length of follow-up: n.r.

Loss-to-follow-up: n.r.

Incomplete outcome data: n.r.

|

Neurosurgery Defined by any injury requiring neurosurgical intervention.

Effect measure: Sensitivity [95% CI] / Specificity [95% CI]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN < 2 years 0.87 [0.60 – 0.98] / 0.71 [0.69 – 0.73]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN ≥ 2 years 1.00 [0.63 – 1.00] / 0.80 [0.78 – 0.81]

|

Author’s conclusion The PECARN rules seemed to be safely applicable to children with minor head trauma in Japan. Further studies are required to show safety in the hospitals where physicians do not have expertise in managing. children. |

|

Lorton, 2016 |

Type of study: multicentre prospective study.

Setting and country: Multicentre, France.

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding information is not available; The authors declare that they have no competing interests. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 1499

Age: Median (IQR) months 3 (1.7 – 6)

|

|

Length of follow-up: n.r.

Loss-to-follow-up: 66%

Incomplete outcome data: n.r.

|

Neurosurgery Defined by any injury requiring neurosurgical intervention.

Effect measure: Sensitivity [95% CI] / Specificity [95% CI]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN < 2 years 1.00 [0.29 – 1.00] / 0.64 [0.59 – 0.69]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN ≥ 2 years 1.00 [0.54 – 1.00] / 0.72 [0.69 – 0.75]

|

Author’s conclusion We conducted a prospective multicentre validation study of the PECARN clinical decision rule for detection of ciTBI in children with minor head trauma, according to the methodological standards. The PECARN rule successfully identified all of the patients with ciTBI, with a limited use of CT scans. A broad validation study with a large cohort is needed to allow sufficient statistical power before authorizing its implementation and generalization. Such a study is currently underway, with recruitment taking place in nine French general and paediatric EDs (ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier: NCT02357186). |

|

Osmond, 2018 |

Type of study: prospective multicentre cohort study

Setting and country: Multicentre, Canada.

Funding and conflicts of interest: No competing interests: This study was funded by a peer reviewed. grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR funding reference no. MOP-43911). |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 4060

Age: Mean (SD) years 9.7 (4.8)

|

|

Length of follow-up: n.r.

Loss-to-follow-up: 434/4494 (9.7%)

Incomplete outcome data: n.r.

|

Neurosurgery Defined by any injury requiring neurosurgical intervention.

Effect measure: Sensitivity [95% CI] / Specificity [95% CI]

Clinical decision rule: CATCH 0.91 [0.72 – 0.99] / 0.57 [0.56 – 0.59]

Clinical decision rule: CATCH 0.98 [0.94 – 0.99] / 0.60 [0.58 – 0.61]

|

Author’s conclusion Among children presenting to the emergency department with the signs and symptoms of acute minor head injury, the CATCH rule was highly sensitive for identifying those children requiring. neurosurgical intervention and those with any brain injury on CT. The CATCH rule should be further validated in an implementation study designed to assess its clinical impact. |

|

Schonfeld, 2014 |

Type of study: Cross-sectional study.

Setting and country: Multicentre, USA, Italy.

Funding and conflicts of interest: No competing interests; Funding: Hood Childhood Research Grant, Boston Children’s Hospital House-officers Grant. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 2439

|

|

Length of follow-up: n.r.

Loss-to-follow-up: n.r.

Incomplete outcome data: n.r.

|

Intracranial injury Clinically important brain injury.

Effect measure: Sensitivity [95% CI] / Specificity [95% CI]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN < 2 years 1.00 [0.63 – 1.00] / .43 [0.40 – 0.46]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN ≥ 2 years 1.00 [0.79 – 1.00] / 0.48 [0.46 – 0.51]

|

Author’s conclusion In our external validation study, the PECARN TBI age-based clinical predication rules performed well by accurately identifying. children who are at very low risk for a clinically important TBI who can safely avoid a CT scan. These can be used to assist with clinical decision making for children with minor head trauma. Prospective implementation of the PECARN TBI rules must be carefully studied to determine the impact on CT rates as well as missed injuries. |

|

Shavit, 2020 |

Type of study: Evaluation of an external dataset (APHIRST)

Setting and country: Multicentre, New Zealand.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council; The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any concept discussed in this article. The authors have no financial relationships to disclose. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 18913

|

|

Length of follow-up: 72h post-discharge.

Loss-to-follow-up: n.r.

Incomplete outcome data: n.r.

|

Intracranial injury Clinically important traumatic brain injury.

Effect measure: Sensitivity [95% CI] / Specificity [95% CI]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN < 2 yrs 1.00 [0.92 – 1.00] / 0.59 [0.58 – 0.61]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN 2 - 18 yrs 1.00 [0.95 – 1.00] / 0.52 [0.51 – 0.53]

|

Author’s conclusion The clinical decision rules demonstrated high accuracy in identifying ciTBI. As a screening tool, the PECARN rule outperformed IDITBIC. The findings suggest that clinicians should strongly consider directing children with GCS <15 at presentation to CT scan. |

|

Thiam, 2015 |

Type of study: Observational cohort study Setting and country: Single centre, Singapore

Funding and conflicts of interest: The ongoing prospective head injury surveillance is supported by the Paediatrics Academic Clinical Program (Paeds ACP) Young Researcher Pilot Grant. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: CATCH: 3866 CHALICE: 22 772 PECARN: 42 412

|

|

Length of follow-up: 72h post-discharge.

Loss-to-follow-up: n.r.

Incomplete outcome data: n.r.

|

Intracranial injury Clinically important brain injury.

Effect measure: Sensitivity [95% CI] / Specificity [95% CI]

Clinical decision rule: CATCH 1.00 [0.54 – 1.00] / 0.80 [0.78 – 0.83]

Clinical decision rule: CHALICE 0.83 [0.36 – 1.00] / 0.76 [0.74 – 0.79]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN high and intermediate risk 1.00 [0.54 – 1.00] / 0.62 [0.59 – 0.64]

Clinical decision rule: PECARN high-risk only 1.00 [0.54 – 1.00] / 0.97 [0.96 – 0.98] |

Author’s conclusion The CDRs demonstrated high accuracy in detecting. children with positive CT findings but its direct application would likely lead to a significant increase in unnecessary CT scans in our population. Clinical observation in most cases are a viable alternative. |

b. Diagnostic impact studies

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy – otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

|

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

|

Abid, 2021 |

Type of study: A phase II prospective, randomised study.

Setting and country: Multi-centre, United States.

Funding and conflicts of interest: By Annals policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). The authors have stated that no such relationships exist. The authors report this article did not receive any outside funding or support. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 514 Control: 567

Important prognostic factors2: Age: <1 mo: 26.1%^ 1-2 mo: 41.2% 2-3 mo: 32.8%

Sex: 47.5% F

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Patients who met the PECARN low-risk criteria that were developed for children younger than 2 years.

|

Patients who did not meet those PECARN low-risk criteria. |

Length of follow-up: ≥ 2 nights of hospitalisation.

Loss-to-follow-up: 65/1147 (5.7%)

Reason: PECARN low-risk variables missing.

Incomplete outcome data: 1/1147 (0.09%

Reason: missing clinically important traumatic brain injury data.

|

Clinically important traumatic brain injury Defined as death from the traumatic brain injury, traumatic brain injuries requiring neurosurgical procedures, intubation for at least 24 hours for the traumatic brain injury, or hospitalization for 2 or more nights because of head trauma and ongoing signs/symptoms in association with traumatic brain injury on CT.

Effect measure: n/N (%) I: 1/514 (0.19%) C: 24/456 (4.2%)

Traumatic brain injury on CT Defined as any acute traumatic intracranial findings or skull fractures depressed by at least the width of the table of the skull.

Effect measure: n/N (%) I: 10/197 (5.1%) C: 93/436 (21.3%)

Skull fracture on CT Defined as any skull fracture seen on CT, including basilar skull fractures, depressed skull fractures, and other fractures meeting the definition of traumatic brain injury on CT, or those requiring neurosurgical intervention (eg, depressed fractures requiring elevation).

Effect measure: n/N (%) I: 9/197 (4.6%) C: 122/436 (28%) |

Author’s conclusion In conclusion, the PECARN traumatic brain injury low risk criteria accurately identified infants younger than 3 months at low risk of clinically important traumatic brain injuries. However, infants at low risk for clinically important traumatic brain injuries remained at risk for traumatic brain injuries on CT, suggesting the need for a cautious approach in these youngest infants. |

Risk of bias tables

a. Diagnostic performance studies

Risk of bias table for systematic review of diagnostic test accuracy studies

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?5

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?8

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Pandor, 2011 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No Due to clinical heterogeneity and lack of studies (n<5) data was not suitable for pooling in a forest plot. |

Unclear |

No |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate (in relation to the research question to be answered in the clinical guideline) and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to the research question (PICO) should be reported

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (preferably QUADAS-2; COSMIN checklist for measuring instruments) and taken into account in the evidence synthesis

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, diagnostic tests (strategy) to allow pooling? For pooled data: at least 5 studies available for pooling; assessment of statistical heterogeneity and, more importantly (see Note), assessment of the reasons for heterogeneity (if present)? Note: sensitivity and specificity depend on the situation in which the test is being used and the thresholds that have been set, and sensitivity and specificity are correlated; therefore, the use of heterogeneity statistics (p-values; I2) is problematic, and rather than testing whether heterogeneity is present, heterogeneity should be assessed by eye-balling (degree of overlap of confidence intervals in Forest plot), and the reasons for heterogeneity should be examined.

- There is no clear evidence for publication bias in diagnostic studies, and an ongoing discussion on which statistical method should be used. Tests to identify publication bias are likely to give false-positive results, among available tests, Deeks’ test is most valid. Irrespective of the use of statistical methods, you may score “Yes” if the authors discuss the potential risk of publication bias.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS II, 2011)

|

Study reference |

Patient selection

|

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Babl, 2017 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Unclear

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Unclear

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? No

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? No

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? Unclear

|

|

Bozan, 2019 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Unclear

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? No

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? No

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? No

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

Easter, 2014 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Unclear

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? No

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? No

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? No

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

Ide, 2020 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Unclear

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? No

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? No

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

Lorton, 2016 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Unclear

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear