Indicaties CT-scan hersenen volwassenen

Uitgangsvraag

Welke volwassen patiënten komen in aanmerking voor een CT-scan hersenen na licht THL in de acute fase?

Om de uitgangsvraag te beantwoorden is deze vraag onderverdeeld in twee deelvragen:

- Welke klinische beslisregel(s) kan/kunnen worden gebruikt in de klinische praktijk om te beoordelen of patiënten een CT-scan hersenen behoeven?

- Is het gebruik van de nieuwe antistollingsmiddelen (DOAC’s), laagmoleculaire heparines in therapeutische doseringen, clopidogrel en combinaties van trombocytenaggregatieremmers een risicofactor voor het optreden van traumatische intracraniële hemorragische afwijkingen bij patiënten met een doorgemaakt licht THL?

Aanbeveling

Maak gebaseerd op de CCHR een CT-scan hersenen bij patiënten ≥ 16 jaar die < 24u na licht THL op de SEH komen en indien er sprake is van ten minste één van de volgende factoren (zie flowchart):

- Leeftijd 65 jaar of ouder

- EMV-score < 15 twee uur na trauma

- Neurologische uitvalsverschijnselen

- Post-traumatisch insult

- Gevaarlijk mechanisme: focaal high impact letsel#, hoogenergetisch traumamechanisme*, val van > 1 m hoogte

- Verdenking op open of impressie schedelfractuur

- Tekenen van schedelbasisfractuur

- Braken: 2 of meer episodes

- Amnesie voor ongeluk (retrograde amnesie) van 30 min of langer

- Gebruik van VKA’s, DOAC’s, trombocytenaggregatieremmers (behoudens acetylsalicylzuur monotherapie), of therapeutisch heparine.

# onder focaal high impact letsel wordt uitwendig zichtbaar letsel verstaan ten gevolge van: bijvoorbeeld een klap met een knuppel of fles op het hoofd, een golf/hockeybal met hoge snelheid tegen het hoofd.

* Onder een hoogenergetisch traumamechanisme wordt verstaan: Hoog risico auto-ongeval (> 30cm indeuking aan zijde slachtoffer; > 45cm indeuking op andere plaats; uit voertuig geslingerd; overlijden in zelfde compartiment). Auto versus voetganger/fietser. Bestuurder/berijder gescheiden van transport medium met significante impact (bijv. motorfiets, paard). Overig trauma met vergelijkbare energie overdracht.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een systematische literatuur analyse uitgevoerd naar de verschillende beslisregels voor het verrichten van een CT-scan hersenen bij volwassen patiënten met een licht THL in de acute fase. Naar mening van de werkgroep is het belangrijk om een beslisregel toe te passen die gevalideerd is in de praktijk, enerzijds om te zorgen voor uniformiteit van beleid, anderzijds om zorgverleners in de acute fase te ondersteunen in de besluitvorming omtrent het maken van een CT-scan hersenen.

De vraag welke beslisregel de voorkeur heeft, is een afweging van factoren. Er wordt enerzijds gestreefd naar een zo hoog mogelijke sensitiviteit, echter dit dient te worden afgewogen tegen het aantal patiënten dat een CT-scan hersenen moet ondergaan. Voor neurochirurgisch ingrijpen dient de sensitiviteit zeer hoog te zijn, omdat het missen van deze afwijkingen naar verwachting negatieve gezondheidseffecten heeft voor de patiënt. In het geval van de detectie van intracraniële afwijkingen hoeft de sensitiviteit niet 100% te zijn, omdat dit vaak geen directe gevolgen heeft voor de behandeling, maar wel van invloed is op het opname en ontslagbeleid. Mogelijk is niet elke intracraniële traumatische afwijking relevant. Het is voorstelbaar dat patiënten met een kleine contusiehaard of geringe hoeveelheid traumatisch arachnoïdaal bloed, een veel kleinere kans hebben op een klinische achteruitgang. De vraag is of deze patiënten veilig naar huis kunnen worden ontslagen, wanneer er geen andere risicofactoren aanwezig zijn die een indicatie om patiënt op te nemen. Een duidelijke definitie van wat een relevante intracraniële afwijkingen is ontbreekt. Dit moet worden beschouwd als een kennislacune.

In het geval van licht THL-patiënten met stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie is het belangrijk om te trachten intracraniële traumatische afwijkingen uit te sluiten, omdat bij deze patiëntengroep de intracraniële afwijkingen invloed kunnen hebben op het beleid; namelijk het wel of niet staken/couperen van stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie. Het risico van stralingsbelasting die een CT-scan hersenen met zich meebrengt is laag, maar is een aspect dat wel moet worden meegewogen. De extra kans op het optreden van fatale kanker door een eenmalige CT-scan is hersenen zeer laag (0,02% zie ook richtlijn “Beeldvorming met ioniserende straling”.

Uit de literatuur blijken meerdere beslisregels een zeer hoge sensitiviteit voor neurochirurgisch ingrijpen te hebben. Voor alle beslisregels is dit in de meeste studies vrijwel 100%. In de studie van Foks (2018), welke gedaan is in de Nederlandse populatie ligt de sensitiviteit iets lager voor de CCHR (0.89), NICE (0.89) en CHIP (0.94) dan voor de NOC (1.00). De hoge sensitiviteit van de NOC-criteria gaat echter ten koste van een zeer lage specificiteit. Dit betekent in het geval van de NOC dat verhoudingsgewijs bij meer patiënten een CT-scan hersenen gemaakt dient te worden wat niet leidt tot neurochirurgisch ingrijpen.

Uitsluitend de CCHR en de NOC zijn uitgebreid gevalideerd in verschillende studies en in verschillende populaties. De CCHR is weliswaar oorspronkelijk alleen gevalideerd voor patiënten na een licht THL mét PTA en/of bewustzijnsverlies en/of verwardheid, maar is zowel met de oorspronkelijke in- en exclusiecriteria als met ‘adjusted’ criteria, waarbij de beslisregel op alle patiënten is toegepast, in meerdere studies onderzocht en lijkt daardoor ook toepasbaar op de gehele groep patiënten met licht THL. Het is van belang om een beslisregel te hebben die toepasbaar is op de gehele populatie omdat intracraniële traumatische afwijkingen ook voorkomen bij patiënten zonder PTA, bewustzijnsverlies of verwardheid en ook neurochirurgisch ingrijpen noodzakelijk kan zijn bij deze patiënten.

In de vorige richtlijn werden de scan criteria gebaseerd op de CHIP-beslisregel. De sensitiviteit voor neurochirurgisch ingrijpen van de CHIP is echter in de meest onderzoeken niet hoger dan de CCHR en is de CCHR uitgebreider gevalideerd dan de CHIP. Daarnaast is CCHR een internationaal geaccepteerde en praktisch toepasbare beslisregel. Dit maakt deze beslisregel ook gemakkelijk toepasbaar in de Nederlandse situatie. Deze beslisregel is gezien de hoge sensitiviteit en de relatief hoge specificiteit naar mening van de werkgroep de beste keuze van de bestaande beslisregels.

De werkgroep vindt het wel nodig om enkele verduidelijkingen in de CCHR aan te brengen voor deze richtlijn. De CCHR spreekt bij gevaarlijk trauma mechanisme specifiek over enkele ongevalsmechanismen (val > 1m, auto versus voetganger, uit auto geslingerd). Andere ongevalsmechanismen met een vergelijkbare energieoverdracht (bijvoorbeeld auto versus fietser) worden niet benoemd. In de studie van Foks (2018) werden negen patiënten met traumatische intracraniële afwijkingen met een indicatie voor neurochirurgisch ingrijpen gemist door de CCHR vanwege deze definitie van het ongevalsmechanisme. Dit kan naar verwachting grotendeels ondervangen worden door de risicofactor gevaarlijk ongevalsmechanisme te verduidelijken en hieronder ook focaal high impact letsel en ieder hoogenergetisch traumamechanisme te verstaan. In de studie van Foks (2018) zou de verduidelijking van de definitie van ‘gevaarlijk trauma mechanisme’ betekenen dat tenminste vijf van deze negen patiënten niet gemist waren. De sensitiviteit voor potentieel neurochirurgisch ingrijpen zou hierdoor in deze studie stijgen van 87.8% naar 94.6%. Bij een hoogenergetisch trauma mechanisme (HET) is er sprake van hoge energieoverdracht waardoor intracraniële afwijkingen of andere (inwendige) letsels kunnen optreden. Een strikte definitie is niet te geven. Voorbeelden van een HET zijn:

- Hoog risico auto-ongeval (> 30cm indeuking aan zijde slachtoffer; > 45cm indeuking op andere plaats; uit voertuig geslingerd; overlijden in zelfde compartiment).

- Auto versus voetganger/fietser

- Bestuurder/berijder gescheiden van vervoersmiddel met significante impact (bijv. geslingerd van een motorfiets, paard etc.)

- Overig trauma met vergelijkbare energie overdracht

Onder focaal high impact letsel wordt bijvoorbeeld verstaan: uitwendig zichtbaar letsel ten gevolge van een klap op het hoofd met een knuppel of fles, een golf/hockeybal met hoge snelheid tegen het hoofd.

Toelichting specifieke risicofactoren:

Leeftijd: Op basis van de CCHR krijgen alle patiënten met een licht THL van 65 jaar of ouder altijd een CT-scan hersenen. Dit betekent dat ten opzichte van de eerdere richtlijn patiënten van 40-65 jaar minder vaak een CT-scan hersenen moeten ondergaan. Er is enig bewijs dat dit criterium nog verder verhoogd zou kunnen worden naar 75 jaar (Fournier, 2019). Dit is echter naar mening van de werkgroep vooralsnog nog onvoldoende onderbouwd om aan te passen.

Stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie: Het gebruik van stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie wordt niet of onvoldoende meegenomen in de bestaande beslisregels. Dit komt doordat patiënten met stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie werden geëxcludeerd bij de ontwikkeling van beslisregels en doordat er sinds de ontwikkeling van de beslisregels nieuwe stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie, zoals clopidogrel en DOAC’s, beschikbaar is gekomen. Daarom is ervoor gekozen om hiervoor een aparte literatuur analyse te doen. Bij patiënten met een licht THL met stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie is het van belang om een zeer hoge sensitiviteit voor zowel neurochirurgisch ingrijpen als traumatische intracraniële afwijkingen te hebben. Dit is enerzijds van belang omdat stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie mogelijk gecoupeerd kan worden. Anderzijds hebben patiënten die stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie gebruiken bij traumatische intracraniële afwijkingen mogelijk een groter risico op achteruitgang dan patiënten zonder stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie. Uit de literatuur blijkt dat trombocytenaggregatie remmers mogelijk een verhoogd risico geven op traumatisch intracranieel letsel (Fiorelli, 2020; Foks, 2018). Echter is de bewijskracht van dit gevonden effect laag. In het onderzoek van Fiorelli (2020) werd er geen verhoogd risico gevonden op intracraniële afwijkingen bij gebruik van alleen acetylsalicylzuur. Aangezien acetylsalicylzuur monotherapie in tegenstelling tot andere trombocytenaggregatieremmers ook al op grote schaal toe werd gepast ten tijde van de ontwikkeling van de belangrijkste beslisregels voor licht THL en dit geen exclusiecriterium was (Stiell, 2010), is de werkgroep van mening dat acetylsalicylzuur monotherapie niet als afzonderlijke risicofactor beschouwd dient te worden voor het verrichten van een CT-scan hersenen na licht THL. Over DOAC’s zijn nog weinig data bekend, aangezien ze relatief kortgeleden als medicijn op de markt zijn gekomen. In de systematische review en meta-analyse van Santing (2022) leidde DOAC gebruik niet tot meer risico op neurochirurgisch ingrijpen in vergelijking met vitamine K antagonisten en trombocytenaggregatieremmers. Momenteel is er nog veel onzekerheid over de mate waarin het gebruik van DOAC risicoverhogend is voor een intracraniële bloeding na een trauma, in afwachting van verder onderzoek heeft de werkgroep besloten om DOAC toch als risicofactor te beschouwen Zowel het gebruik van VKA’s, DOAC’s als trombocytenaggregatie remmers, of therapeutisch heparine, uitgezonderd acetylsalicylzuur monotherapie, dient volgens de werkgroep daarom te worden meegenomen als criterium voor het verrichten van een CT-scan hersenen na een licht THL. Stollingsstoornissen worden niet meegenomen in de bestaande beslisregels. Dit komt zelden voor en ons advies altijd te overleggen met een hematoloog om het risico op intracraniële afwijkingen of neurochirurgisch ingrijpen in te schatten en op basis hiervan te beslissen wel of geen CT-scan hersenen te maken.

Triviaal letsel: In het addendum van de vorige richtlijn (2019) werd triviaal letsel apart gedefinieerd. Sinds het verschijnen van dit addendum zijn een drietal studies verschenen waar bij binnenkomst op de SEH na een val vanuit stand 3% minder CT-afwijkingen aanwezig waren t.o.v. een hoogenergetisch trauma, met vergelijkbare ziekenhuismortaliteit (Lecky 2021). In een cohort met laag- en hoogenergetische trauma werden er bij een laag energetisch trauma, een leeftijd <60 jaar en geen gebruik van stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie geen intracraniële afwijkingen gerapporteerd (Vedin, 2019). Hogere leeftijd en gebruik van stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie waren duidelijke risicofactoren (Lecky, 2021; Vedin, 2019). Deze factoren worden door middel van de CCHR en het meenemen van gebruik van stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie als criterium voldoende meegenomen.

Biomarkers: In deze richtlijn zijn biomarkers niet meegenomen, aangezien het gebruik hiervan in de meeste ziekenhuizen niet standaard beschikbaar is en er vooralsnog nauwelijks ervaring mee is opgedaan in de Nederlandse praktijk. Biomarkers lijken echter veelbelovend, met name om laag-risico patiënten te identificeren en het aantal verwijzingen en CT-scans in deze groep te reduceren. Ontwikkelingen op dit gebied dienen te worden meegenomen bij de toekomstige herziening van deze richtlijn.

Klinische beslisregels zoals de CCHR zijn ten dele bedoeld om het gebruik van de CT-scan te reduceren. Of dit ook op de Nederlandse situatie van toepassing is onduidelijk. Na het invoeren van de vorige richtlijn licht THL, gebaseerd op de CHIP-beslisregel (original), is het gebruik van de CT-scan hersenen toegenomen (Van den Brand, 2017). Echter, de verwachting is dat met het toepassen van de CCHR-beslisregels het gebruik van de CT-scan hersenen t.o.v. de vorige richtlijn juist zal dalen. Uit de data van een studie onder 4557 patiënten in de Nederlandse setting zou toepassing van de CCHR tot een relatieve vermindering van ongeveer 27% CT-scans hersenen leiden ten opzichte van de CHIP (Foks 2018). De absolute vermindering betrof bijna 22% (79.8% - 58.0%).

Ten slotte hebben alle klinisch beslisregels mede als doel de interobserver variatie en subjectieve beoordelingen te reduceren en met name onervaren zorgaanbieders een houvast te geven.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het is niet wenselijk en vaak ook niet goed mogelijk om de beslissing om wel of geen CT-scan hersenen te verrichten bij de patiënt neer te leggen, omdat een licht THL-patiënt in het acute posttraumatische stadium veelal niet in staat is om een afgewogen beslissing te nemen.

De positieve bijdrage van CT-scan hersenen dient altijd te worden afgewogen tegen de nadelen. Belangrijkste nadeel van CT-scan hersenen is de toepassing van ioniserende straling. Daarnaast kan een CT-scan hersenen nevenbevindingen aan het licht brengen die veelal gepaard zullen gaan met extra vervolgonderzoeken en onzekerheid bij de patiënt, terwijl dit meestal niet bijdragend is voor de gezondheid. Daarnaast is het belangrijk om uit te leggen aan de patiënt waarom een CT-scan in bepaalde situaties niet nodig is.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Het gebruik van CT-scans hersenen is de laatste jaren toegenomen zonder dat dit bewezen extra voordeel voor de patiënt heeft opgeleverd. Met deze richtlijnherziening wordt verwacht dat er minder CT-scans hersenen nodig zijn, met een verwachte reductie van begeleidende kosten, zonder dat dit risico’s voor de patiënt oplevert. Wat betreft kosteneffectiviteit van het verrichten van een CT-scan hersenen zijn een aantal studies bekend waarbij is gesteld dat scannen op basis van een sensitieve beslisregel goedkoper is dan kosten van een opname of de kosten van zorg bij uitgestelde behandeling (Smits 2010, Holmes 2012).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Stiell (2010) heeft de potentiële barrières van implementatie van de CCHR onderzocht door kwalitatief onderzoek. Hieruit bleek dat bekendheid met, en het onthouden van de beslisregel de grootste barrière was. Daarnaast zijn de ideeën in het veld over het nut, het doel en het belang van de CT-scan hersenen heterogeen, bijvoorbeeld ten aanzien van documentatie en ontslag naar huis. Tenslotte bleek het gemakkelijk om de beslisregel zonder gevolgen te negeren. Zo kunnen zorgverleners ten aller tijde een CT-scan hersenen aanvragen. Voor hen is capaciteit of toegang geen belemmering.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de diagnostische procedure

De werkgroep is van mening dat op basis van de beschikbare literatuur de CCHR de beste keuze van de bestaande beslisregels is. De CCHR is een simpele beslisregel, die over de hele wereld wordt gebruikt en gemakkelijk toepasbaar is in de Nederlandse situatie. Hierbij dienen de ‘adjusted’ criteria te worden gebruikt, waarbij de beslisregel op alle patiënten van toepassing is. Om de sensitiviteit te verbeteren dient echter wel het mechanisme van het ongeval aangepast te worden. Ook dient bij gebruik van VKA’s, DOAC’s, trombocytenaggregatieremmers (behoudens acetylsalicylzuur monotherapie), of therapeutisch heparine standaard een CT-scan hersenen verricht te worden na een licht THL vanwege de mogelijke therapeutische consequenties. Deze criteria zijn opgenomen in een flowchart.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Bij de eerste opvang van patiënten met licht THL is een CT-scan hersenen de eerste keuze van beeldvormende diagnostiek. Het doel is om traumatische intracraniële afwijkingen te detecteren om te beoordelen of er een indicatie bestaat voor neurochirurgisch ingrijpen en/of het staken van stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie.

In een onderzoek op SEH-afdelingen in Nederland tussen 2015-2017 werd bij 8,4% van de patiënten afwijkingen op de CT-scan gezien, bij 1,6% een afwijking met potentieel neurochirurgisch ingrijpen (zoals bijvoorbeeld een epiduraal hematoom of een groot subduraal hematoom) (van den Brand, 2022).

Er zijn diverse klinische beslisregels beschikbaar om te besluiten of een CT-scan hersenen is geïndiceerd. Deze beslisregels zijn gebaseerd op uiteenlopende risicofactoren die zijn geassocieerd met het optreden van traumatische intracraniële afwijkingen die leiden tot medisch beleid (opname, observatie, medicatie, poliklinische follow-up) of een indicatie vormen tot neurochirurgisch ingrijpen. Het is belangrijk om te beseffen dat deze beslisregels gebruikt worden om te bepalen of een CT-scan hersenen bij een patiënt op de SEH geïndiceerd is en dat dit niet hetzelfde is als verwijscriteria van de huisarts (zie module Verwijscriteria). Na introductie van de voorgaande richtlijn licht THL (2010), gebaseerd op de CHIP-beslisregels, is het gebruik van CT-scans hersenen fors toegenomen. Een reden hiervoor zou enerzijds de hoeveelheid geformuleerde risicofactoren en anderzijds de striktere adherentie aan de richtlijn na het invoeren daarvan kunnen zijn. Onder andere de leeftijdsgrens van 40 jaar als minor criterium werd als een knelpunt gezien.

Voorts werden na de introductie van de vorige richtlijn licht THL aanvullende factoren vastgesteld die een rol spelen in de besluitvorming om wel/geen CT-scan hersenen uit te voeren, zoals triviaal hoofdletsel (2019) en stollingsbeïnvloedende medicatie (2017) die nu zullen worden opgenomen in de huidige module.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Conclusions

1. Neurosurgery

Canadian CT Head Rule (CCHR); 2. New Orleans Criteria (NOC)

|

Low GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the CCHR and the NOC may be accurate for predicting neurosurgery.

Source: Foks, 2018; Papa, 2012; Rosengren, 2004; Smits, 2005; Stein, 2009; Fabbri 2005; Stiell, 2005. |

NICE Head Injury Guideline Recommendations; 4. Scandinavian guideline; 5. The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II (NEXUS II); 6. CT in head injury patients (CHIP)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence about diagnostic accuracy of the NICE, Scandinavian guideline, NEXUS-II and the CHIP for predicting neurosurgery is very uncertain.

Source: Fabbri, 2005; Foks, 2018; Smits, 2007; Stein, 2009; van den Brand, 2022. |

2. Intracranial injury

Canadian CT Head Rule (CCHR)

|

Moderate GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the CCHR is likely accurate for predicting intracranial injury (sensitivity range 0.80 – 1.00; specificity range 0.35 – 0.50).

Sources: Foks, 2018; Ibanez, 2014; Papa, 2012; Rosengren, 2004; Smits, 2005; Stein, 2009; Stiell, 2001; Stiell, 2005. |

New Orleans Criteria (NOC)

|

Moderate GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the NOC is likely accurate for predicting intracranial injury (sensitivity range 0.95 – 1.00; specificity range 0.03 – 0.33).

Source: Foks, 2018; Haydel, 2000; Ibanez, 2004; Papa, 2012; Rosengren, 2004; Smits, 2005; Stein, 2009; Stiell, 2005. |

NICE Head Injury Guideline Recommendations; 4. Scandinavian guideline; 5. The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II (NEXUS II); 6. CT in head injury patients (CHIP)

|

Low GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the NICE, Scandinavian guideline, NEXUS-II and the CHIP may be accurate for predicting intracranial injury.

Source: Fabbri, 2005; Foks, 2018; Smits, 2007; Stein, 2009; Ibanez, 2004; Mower, 2005; van den Brand, 2022. |

Conclusions

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the impact of the Canadian CT Head Rule on clinically (un)important brain injury, neurosurgical intervention, death from brain injury and admission to hospital in patients with mTBI within 24h after the accident.

Source: Stiell (2010) |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found about the impact of the New Orleans Criteria, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Scandinavian guideline, the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II and the CT in Head Injury Patients on patient important outcomes after mTBI within 24h after the accident.

Source: - |

Conclusions Antiplatelet medication and anticoagulation as a criterium for CT scanning

Outcome Need for neurosurgical intervention (critical)

DOACS

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the association between usage of new anticoagulants (DOACS) and the need for neurosurgical intervention in patients with mTBI within 24h after the accident.

Source: Cull, 2015; Grandhi, 2015; Joseph, 2014; Robinson, 2021; Suehiro, 2019; Sumiyoshi, 2017; Tollefsen, 2018; Wettervik, 2021 |

Antiplatelet therapy

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the association between antiplatelet therapy and the need for neurosurgical intervention in patients with mTBI within 24h after the accident.

Source: Beynon, 2015; Galliazzo, 2019; Parra, 2013; Pred, 2018. |

Outcome Intracranial injury (critical)

Antiplatelet therapy

|

Low GRADE |

Usage of antiplatelet therapy may be associated with intracranial injury in patients with mTBI within 24h after the accident.

Source: Galliazzo, 2019; Gonzalez, 2020; Hamden, 2014; Nishijma, 2018; O’Brien, 2020; Probst, 2020; Riccardi, 2013; Spektor, 2003; Uccella, 2018. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

- Clinical decision rules and additional criteria for CT scanning

- Diagnostic performance studies

Harnan (2011) conducted a systematic review on clinical decision rules for adults with mTBI for determining intracranial injuries or necessity of neurosurgical intervention. In total 22 articles were included in the systematic review, representing 19 studies, reporting 25 decision rules. To answer the clinical question for this module, only the following validated clinical prediction rules for CT assessment were extracted: The Canadian CT Head Rule (CCHR), New Orleans criteria (NOC), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Scandinavian guideline, National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II (NEXUS-II) and CT in Head Injury Patients (CHIP).

Pandor (2011) conducted a systematic review on the diagnostic accuracy of clinical decision rules and individual characteristics for predicting intracranial injury, including need for neurosurgery in adults and children with mTBI. In total, 93 papers were included in the systematic review. In the analyses, the diagnostic accuracy of individual clinical characteristics, biomarkers and clinical decision rules were assessed. To answer the clinical question for this module, only the validated clinical prediction rules for CT assessment were extracted: CCHR, NOC, NICE, Scandinavian guideline, NEXUS-II and CHIP.

Foks (2018) performed a prospective multicenter cohort study on the diagnostic performance of the NOC, CHIP, CCHR and NICE guidelines in the Netherlands (n=4557).

Mower (2017) performed a prospective observational study on the validation of the NEXUS Head CT instrument and compared this with the Canadian Head CT decision rule (n=11770).

Papa (2012) performed a prospective observational cohort study on the diagnostic performance of the CCHR and NOC in the United States (n=656).

Van den Brand (2022) performed a secondary analysis of the data from Foks (2018) on the diagnostic performance of the CHIP (n=4557). - Diagnostic impact studies

Stiell (2010) performed a matched-pair cluster-design trial on the impact of the Canadian Ct Head Rule. Patients were included when corresponding to the following criteria: 1) blunt trauma to the head resulting in witnessed loss of consciousness; 2) amnesia or witnessed disorientation; 3) an initial Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13 or greater; and 4) occurrence of the injury within the previous 24 hours. Patients were excluded if 1) younger than 16 years of age; 2) penetrating skull injury; 3) focal neurologic deficit; 4) suffered a seizure before arrival at the emergency department; 5) bleeding disorder or used warfarin; or 6) returned for reassessment of the same head injury. The Canadian CT Head Rule was implemented at six intervention sites (n=1049), while in the six control sites (n=876) no specific intervention were introduced to alter the CT-scan-ordering behavior. The following outcomes were assessed: referral for CT scan of the head, cases of brain injury, number of deaths from head injury and return visits to emergency department within 30 days. - Association studies

In total, 19 observational studies assessed the association between individual clinical (baseline) variables and presence of intracranial injury or the need for neurosurgical intervention to determine whether CT scanning is needed.

- Antiplatelet medication and anticoagulation as a criterium for CT scanning

Cheng (2022) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis about the impact of preinjury use of antiplatelet drugs on outcomes of traumatic brain injury. A systematic literatures search was performed in Pubmed, Embase and Google Scholar from inception up to May 15th, 2021. Cohort studies, in patients sustaining TBI; comparing preinjury use of an antiplatelet drug to no preinjury use of antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs; on mortality, functional outcome, need for surgical intervention or length of stay as outcomes, were included (n=20). The studies assessing need for surgical intervention as an outcome were extracted for this module (Joseph, 2014; Cull, 2015; Grandhi, 2015; Sumiyoshi, 2017; Tollefsen, 2018; Suehiro, 2019; Robinson, 2021; Wettervik, 2021). It is important to note that these studies did not (only) include mild TBI patients, but (also) moderate and severe TBI patients.

Fiorelli (2020) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis about the risk of intracranial hemorrhage after mild traumatic brain injury in patients on antiplatelet therapy. A systematic literature search was performed on MEDLINE and EMBASE from inception up to April 2020. Prospective and retrospective studies 1) comparing mild TBI patients on antiplatelet medication to those without antiplatelet medication nor antithrombotic therapy; and 2) assessing intracranial hemorrhage as outcome, were included. (n=9). All studies were extracted for this module (Probst, 2020; O’Brien, 2020; Gonzalez, 2020; Galliazoo, Uccella, 2018; Nishijma, 2018; Hamden, 2014; Riccardi, 2013; Spektor, 2003).

Santing (2022) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis about the relationship between pre-injury direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) use and traumatic hemorrhagic complications in elderly mTBI patients. A systematic literature search was performed in PubMed and Embase for retrospective and prospective observational cohort studies and case-control studies. Studies were included if 1) the relationship between (any type of) DOAC and traumatic intracranial hemorrhage after mTBI was assessed; 2) patients aged ≥60 were included; 3) mTBI was defined as a GCS score of 13-15. Studies were excluded when 1) there was no control group; 2) studies involved also non-TBI patients; only composite outcomes were reported. A total of 16 studies concerning 3671 elderly mTBI patients were included in the systematic review. For this module, only the studies comparing DOAC use, and no antithrombotic therapy use were extracted (Beynon, 2014; Galliazzo, 2019; Parra, 2013; Prexi, 2018). Effects were evaluated by assessing the outcome neurosurgical intervention.

Results

- Clinical decision rules and additional criteria for CT scanning

The inclusion criteria for the selected clinical prediction rules were shown in table 1.

Table 1. Inclusion- and exclusion criteria per clinical decision rule

|

Clinical decision rule |

Inclusion criteria |

Exclusion criteria |

|

Canadian CT head rule |

GCS score of 13-15, loss of consciousness, definite amnesia or witnessed disorientation, no neurological deficit, no seizure, no anticoagulation, aged ≥16 yr. |

Aged <16 yrs, minimal head injury, no clear history of trauma as the primary event, obvious penetrating skull injury or depressed fracture, acute focal neurological deficit, unstable vital signs associated with major trauma, seizure before assessment in the emergency department, bleeding disorder or usage of oral anticoagulants, return for reassessment of the same injury, pregnancy. |

|

New Orleans Criteria |

GCS score of 15, loss of consciousness, no neurological deficit, aged > 3 yr. |

Patients who declined CT, had concurrent injuries that precluded the use of CT, or reported no loss of consciousness or amnesia for the traumatic event. |

|

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines |

Patient who had attended the emergency department with any trauma to the head (except superficial injuries to the face). |

Any patient episode that was a reattendance. |

|

Scandinavian guidelines |

GCS 14-15, presence/absence of LOC, aged > 14 yrs, evaluated in the emergency department. |

- |

|

National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II |

All blunt trauma patients undergoing cranial CT. |

Patients with penetrating trauma, those with delayed presentations (greater than 24 hours after injury), patients undergoing imaging for reasons unrelated to trauma.

|

|

CT in Head Injury Patients |

Initial presentation <25h of blunt head injury to the head, ≥16 years, GCS 13-15, at least 1 risk factor (history of LOC, short-term memory deficit, amnesia for the traumatic event, posttraumatic seizure, vomiting, severe headache, clinical evidence of intoxication with alcohol or drugs, use of anticoagulants or history of coagulopathy, external evidence of injury above the clavicles, and neurologic deficit.

|

Transfer from another hospital, contraindications for CT, or concurrent injuries precluding a head CT at presentation. |

Abbreviations: GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; LOC: loss of consciousness; CT: computed tomography.

- Diagnostic performance studies

An overview of the clinical factors included in the selected clinical decision rules is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Overview of clinical factors included in clinical decision rules for requirement of head CT

|

|

CCHR |

NOC |

NICE guidelines |

Scandinavian guidelines |

NEXUS-II |

CHIP (simple)

|

CHIP (detailed) |

|

GCS score |

13-15 |

14-15 |

|

14-15 |

|

13-15 or a change 1 h after presentation |

13-15 |

|

Vomiting |

≥2 |

x |

|

≥2 |

X |

x |

≥2 |

|

Age |

>65 yr |

>60 yr |

>65 + LOC or PTA |

>65 yr |

≥65 |

per 10 yrs>16 |

per year >16 |

|

PTA |

x |

x |

|

|

|

x |

x |

|

Dangerous injury mechanism |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

Headache |

|

x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Injury above clavicles |

|

x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Posttraumatic seizure |

|

x |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

Coagulopathy |

|

|

x + LOC or PTA |

x |

X |

|

|

|

Focal neurological deficit |

|

x |

|

x |

X |

x |

x |

|

Shunt-treated hydrocephalus |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

|

|

Anticoagulants |

|

|

warfarin |

x |

|

x |

|

|

Use of antiplatelets |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

x |

|

Loss of consciousness |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

x |

x |

|

serum S1008 analysis |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

|

|

Scalp hematoma |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Altered level of alertness |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Abnormal behaviour |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Fall from any elevation |

|

|

|

|

|

x |

x |

|

Pedestrian or person versus vehicle |

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

|

Ejected from vehicle |

|

|

|

|

|

x |

|

|

Any sign of basal skull fracture |

x |

|

|

x |

|

x |

x |

|

Suspected open or depressed skull fracture |

x |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

|

Retrograde amnesia |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intoxication |

|

x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Persistent anterograde amnesia |

|

x |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

Significant extracerebral injury |

|

|

|

x |

|

|

|

|

Contusion skull |

|

|

|

|

|

x |

x |

Abbreviations: GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; LOC: loss of consciousness; CT: computed tomography; CCHR: Canadian CT Head Rule; NOC: New Orleans criteria; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NEXUS II: National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study II; CHIP: CT in Head Injury Patients.

Figure 1-16 show the diagnostic accuracy for each clinical decision rule.

1. Canadian CT Head Injury/Trauma Rule (CCHR)

1. Neurosurgery

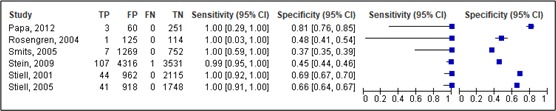

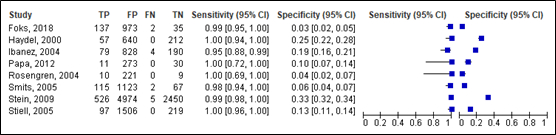

For neurosurgery, sensitivity of the original CCHR ranged between 0.99 and 1.00 (95% CI range was 0.03 – 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.37 and 0.81 (95% CI range was 0.35 – 0.85). The spread in sensitivity was caused by the use of only high-risk criteria in some studies (for example in Papa (2012)) and using high risk and medium risk criteria in the other studies.

For the adapted CCHR, sensitivity ranged between 0.89 and 1.00 (95% CI range was 0.78 – 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.37 and 0.40 (95% CI was 0.36 – 0.42). Results are shown in Figure 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Sensitivity and specificity of the original CCHR for neurosurgery.

Adapted

Figure 2. Sensitivity and specificity of the adapted CCHR for neurosurgery.

2. Intracranial injury

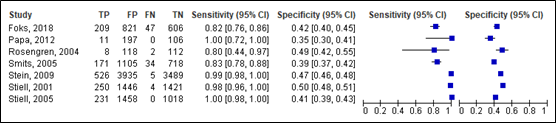

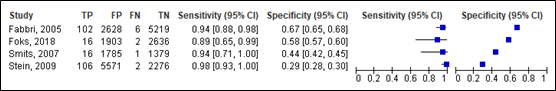

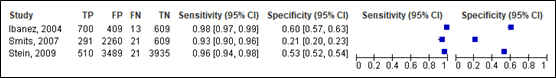

For intracranial injury, sensitivity of the original CCHR ranged between 0.80 and 1.00 (95% CI range was 0.44 – 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.35 and 0.50 (95% CI range was 0.30 – 0.55). For the adapted CCHR, sensitivity ranged between 0.82 and 0.85 (95% CI range was 0.76 – 0.92). Specificity ranged between 0.40 and 0.50 (95% range was 0.38 – 0.54). Results are shown in Figure 3 and 4.

Original

Figure 3. Sensitivity and specificity of the original CCHR for intracranial injury.

Adapted

Figure 4. Sensitivity and specificity of the adapted CCHR for intracranial injury.

2. New Orleans criteria (NOC)

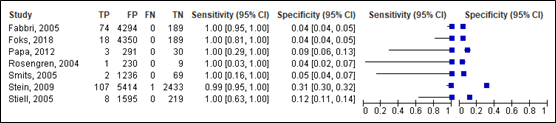

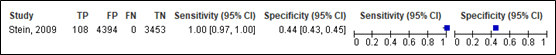

3. Neurosurgery

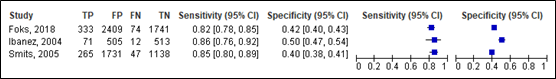

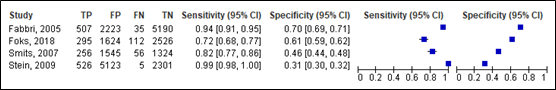

For neurosurgery, sensitivity of the NOC ranged between 0.99 and 1.00 (95% CI range was 0.03 – 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.04 and 0.31 (95% CI range was 0.02 and 0.32). Results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Sensitivity and specificity of the NOC for neurosurgery.

4. Intracranial injury

For intracranial injury, sensitivity of the NOC ranged between 0.95 and 1.00 (95% CI range was 0.69 -1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.03 and 0.33 (95% CI range was 0.02 – 0.34). Results are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Sensitivity and specificity of the NOC for intracranial injury.

3. NICE Head Injury Guideline Recommendations

5. Neurosurgery

For neurosurgery, sensitivity for the NICE ranged between 0.89 and 0.94 (95% CI range was 0.65 – 0.93). Specificity ranged between 0.29 and 0.67 (95% CI range was 0.28 – 0.68). Results are shown in Figure 7.

Lenient criteria

Figure 7. Sensitivity and specificity of the NICE for neurosurgery.

6. Intracranial injury

For intracranial injury, sensitivity for the NICE ranged between 0.72 and 0.99 (95% CI range was 0.68 – 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.31 and 0.70 (95% CI range was 0.30 – 0.71). Results are shown in Figure 8.

Lenient criteria

Figure 8. Sensitivity and specificity of the NICE for intracranial injury.

4. Scandinavian guideline

7. Neurosurgery

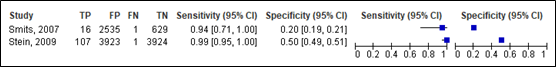

For neurosurgery, sensitivity of the Scandinavian guideline ranged between 0.94 and 0.99 (95% CI range was 0.71 – 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.20 and 0.50 (95% CI range was 0.19 – 0.51). Results are shown in Figure 9.

Lenient criteria

Figure 9. Sensitivity and specificity of the Scandinavian lenient and strict criteria for neurosurgery.

8. Intracranial injury

For intracranial injury, sensitivity of the Scandinavian guideline ranged between 0.93 and 0.98 (95% CI range was 0.90 – 0.97). Specificity ranged between 0.21 and 0.60 (95% CI range was 0.20 – 0.63). Results are shown in Figure 10.

Lenient criteria

Figure 10. Sensitivity and specificity of the Scandinavian lenient and strict criteria for intracranial injury.

5. The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II (NEXUS II)

9. Neurosurgery

For neurosurgery, sensitivity of the NEXUS-II was 1.00 (95% CI 0.97 – 1.00). Specificity was 0.44 (95% CI 0.43 – 0.45). Results are show in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Sensitivity and specificity of NEXUS II rule for neurosurgery.

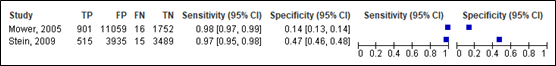

10. Intracranial injury

For intracranial injury, sensitivity of the NEXUS-II ranged between 0.98 and 0.98 (95% CI range was 0.95 – 0.99). Specificity ranged between 0.14 and 0.47 (95% CI range was 0.13 and 0.48). Results are shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Sensitivity and specificity of NEXUS II rule for intracranial injury.

6. CT in head injury patients (CHIP)

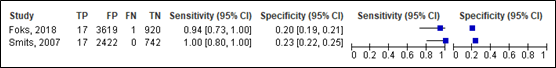

11. Neurosurgery

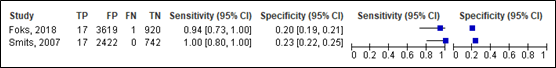

For neurosurgery, sensitivity of the CHIP simple decision rule ranged between 0.94 and 1.00 (95% CI range was 0.73 – 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.20 and 0.23 (95% CI 0.19 – 0.25). Results are shown in Figure 13.

Simple decision rule

Figure 13. Sensitivity and specificity of CHIP simple decision rule for neurosurgery.

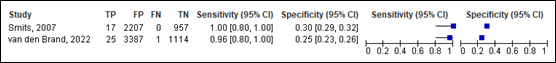

For neurosurgery, sensitivity of the CHIP detailed decision rule ranged between 0.93 and 1.00 (95% CI was 0.80 – 1.00). Specificity ranged between 0.27and 0.30 (95% range was 0.26 and 0.32). Results are shown in Figure 14.

Detailed decision rule

Figure 14. Sensitivity and specificity of CHIP detailed decision rule for neurosurgery.

12. Intracranial injury

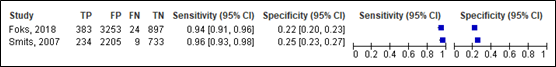

For intracranial injury, sensitivity of the CHIP simple decision rule ranged between 0.94 and 0.96 (95% CI 0.91 – 0.98). Specificity ranged between 0.22 and 0.25 (95% CI range was 0.20 and 0.27). Results are shown in Figure 15.

Simple decision rule

Figure 15. Sensitivity and specificity of CHIP simple decision rule for intracranial injury.

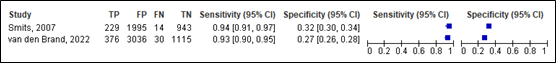

For intracranial injury, sensitivity of the CHIP detailed decision rule ranged between 0.93 and 0.94 (95% CI 0.91 – 0.97). Specificity ranged between 0.27 and 0.32 (95% CI range was 0.26 and 0.34). Results are shown in Figure 16.

Detailed decision rule

Figure 16. Sensitivity and specificity of CHIP detailed decision rule for intracranial injury.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. Neurosurgery

The level of evidence in the literature started at high because it was based on diagnostic test accuracy studies. For the CCHR and the NOC, the level of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to verification bias and methodological shortcomings (-2, risk of bias). The final level is low. For the NICE, the Scandinavian guideline, NEXUS-II and the CHIP, the level of evidence was downgraded by three levels due to a short follow-up, verification bias and methodological shortcomings (<30 days in most studies) (-2, risk of bias) and low number of included studies (-1, imprecision). The final level is very low.

2. Intracranial injury

The level of evidence in the literature started at high because it was based on diagnostic test accuracy studies. For the CCHR and the NOC, the level of evidence was downgraded due to methodological shortcoming (-1, risk of bias). The final level is moderate. For the NICE, the Scandinavian guideline, NEXUS-II and the CHIP, the level of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to methodological shortcomings (-1, risk of bias) and low number of included studies (-1, imprecision). The final level is low.

Conclusions

1. Neurosurgery

Canadian CT Head Rule (CCHR); 2. New Orleans Criteria (NOC)

|

Low GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the CCHR and the NOC may be accurate for predicting neurosurgery.

Source: Foks, 2018; Papa, 2012; Rosengren, 2004; Smits, 2005; Stein, 2009; Fabbri 2005; Stiell, 2005. |

NICE Head Injury Guideline Recommendations; 4. Scandinavian guideline; 5. The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II (NEXUS II); 6. CT in head injury patients (CHIP)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence about diagnostic accuracy of the NICE, Scandinavian guideline, NEXUS-II and the CHIP for predicting neurosurgery is very uncertain.

Source: Fabbri, 2005; Foks, 2018; Smits, 2007; Stein, 2009; van den Brand, 2022. |

2. Intracranial injury

Canadian CT Head Rule (CCHR)

|

Moderate GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the CCHR is likely accurate for predicting intracranial injury (sensitivity range 0.80 – 1.00; specificity range 0.35 – 0.50).

Sources: Foks, 2018; Ibanez, 2014; Papa, 2012; Rosengren, 2004; Smits, 2005; Stein, 2009; Stiell, 2001; Stiell, 2005. |

New Orleans Criteria (NOC)

|

Moderate GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the NOC is likely accurate for predicting intracranial injury (sensitivity range 0.95 – 1.00; specificity range 0.03 – 0.33).

Source: Foks, 2018; Haydel, 2000; Ibanez, 2004; Papa, 2012; Rosengren, 2004; Smits, 2005; Stein, 2009; Stiell, 2005. |

NICE Head Injury Guideline Recommendations; 4. Scandinavian guideline; 5. The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II (NEXUS II); 6. CT in head injury patients (CHIP)

|

Low GRADE |

The diagnostic accuracy of the NICE, Scandinavian guideline, NEXUS-II and the CHIP may be accurate for predicting intracranial injury.

Source: Fabbri, 2005; Foks, 2018; Smits, 2007; Stein, 2009; Ibanez, 2004; Mower, 2005; van den Brand, 2022. |

b. Diagnostic impact studies

The trial from Stiell (2010) assessed the impact of applying the Canadian CT Head Rule compared to not applying this rule in mTBI patients by assessing the following clinical outcomes:

- Clinically important brain injury (epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, intracerebral hematoma, cerebellar hematoma, diffuse cerebral edema, cerebral contusion, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intraventricular hemorrhage, pneumocephalus, depressed skull fracture), requiring hospital admission and neurosurgical follow-up;

- Clinically unimportant brain injury;

- Neurosurgical intervention (craniotomy, elevation of skull fracture, isolated intubation for head injury, isolated intracranial pressure monitoring);

- Death from brain injury;

- Admitted to hospital.

Results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Impact of the Canadian CT Head rule on patients’ outcomes (extracted from Stiell, 2010)

|

|

Intervention hospitals, n (%) |

Control hospitals, n (%) |

||

|

|

Before |

After |

Before |

After |

|

Rate of CT-imaging |

62.8% |

76.2% |

67.5% |

74.1% |

|

Clinically important brain injury |

55 (5.2%) |

92 (6.0%) |

50 (6.8%) |

55 (5.1%) |

|

Clinically unimportant brain injury |

39 (3.7%) |

40 (2.6%) |

21 (2.4%) |

25 (2.3%) |

|

Neurosurgical intervention |

9 (0.9%) |

8 (0.5%) |

8 (0.9%) |

8 (0.7%) |

|

Death from brain injury |

1 (0.1%) |

1 (0.1%) |

3 (0.3%) |

1 (0.1%) |

|

Admitted to hospital |

214 (20.4%) |

386 (25.2%) |

177 (20.2%) |

168 (16.5%) |

The impact of the New Orleans Criteria, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Scandinavian guideline, the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II and the CT in Head Injury Patients was not assessed.

The level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures started at high because they were based on a randomized controlled trial. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels due to lack of randomization, low physician compliance with the requisition form and unbalanced baseline characteristics (-2, risk of bias) and low number of events (-1, imprecision). The final level is very low.

Conclusions

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the impact of the Canadian CT Head Rule on clinically (un)important brain injury, neurosurgical intervention, death from brain injury and admission to hospital in patients with mTBI within 24h after the accident.

Source: Stiell (2010) |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found about the impact of the New Orleans Criteria, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Scandinavian guideline, the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II and the CT in Head Injury Patients on patient important outcomes after mTBI within 24h after the accident.

Source: - |

c. Association studies

From the 19 observational studies, the following variables were significantly associated with intracranial injury or neurosurgical intervention in addition to the criteria that were included in the clinical decision rules. Table 4 shows an overview of the included studies assessing clinical variables that are significantly associated with intracranial injury:

- Alcohol/drugs abuse;

- Head laceration or bruise;

- New abnormalities found on neurologic examination;

- Chronic kidney disease;

- Duration since injury is 6 hours or less;

- Anisocoria.

There were no clinical variables that were significantly associated with need for neurosurgical intervention (apart from the variables included in clinical decision rules).

Table 4. Additional criteria to clinical decision rules for CT scanning

|

Study |

Population |

Analysis |

All criteria significantly associated with outcome |

Criteria significantly associated with outcome, not included in clinical decision rules |

|

Intracranial injury |

||||

|

Fabbri, 2010 |

Consecutive subjects aged 10 years or more who attended the emergency department (ED) (n=48000) |

Multivariable model to assess variables that are independently associated with intracranial lesions. |

GCS 14, suspected skull fracture, vomiting, age ≥ 65, age ≥ 75, coagulopathy, neurological deficit, seizure, LOC

|

-

|

|

Frabbri, 2005 |

All patients attending for acute MHI within 24 h from trauma (n=7955) |

Multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis |

GCS 14 or <14 at any time, suspected skull fracture, neurological deficits, vomiting, amnesia, LOC, coagulopathy, alcohol/drugs abuse, post-traumatic seizures, dangerous mechanism, age ≥ 65. |

Alcohol/drugs abuse. |

|

Brewer, 2011 |

Trauma registry patients with minor head injury (n=140) |

Forward and backward unconditioned logistic regression analysis to assess predictors for a positive CT finding. |

LOC |

- |

|

Claudia, 2011 |

Adult patients with minor head injuries evaluated by the Emergency Department (n=1554) |

Multiple linear regression for the association between the variable and outcome. |

Clinical evidence of skull fracture |

-

|

|

De Wit, 2020 |

Patients were identified by ED research staff or the emergency physician during the patient’s ED visit following a fall (n=1753) |

Multivariable logistic regression with a penalized maximum likelihood approach to account for the small number of events was used to investigate the relationship between the variables and intracranial bleeding. |

New abnormalities found on neurologic examination, head laceration or bruise, chronic kidney disease and reduced GCS compared to normal. |

Head laceration or bruise, new abnormalities found on neurologic examination and chronic kidney disease. |

|

Ibanez, 2004 |

Patients with MHI who were older than 14 years and had been evaluated in the emergency department at our institution by any of the four participating neurosurgeons (n=1101) |

Binary logistic regression analysis was performed using the backward stepwise method together with the Wald statistic for variable selection. |

LOC, headache, signs of basilar skull fracture. |

- |

|

Ibanez Perez de la Blanca, 2018 |

patients aged ≥ 60 years admitted to the emergency department within 24 h of an MTBI (n=504) |

A multivariate stepwise logistic regression model was constructed, with ICL as dependent variable and variables demonstrating significance in bivariate analyses as independent variables, calculating odds ratios (Ors) with 95% confidence intervals (Cis). |

GCS 14, LOC, nausea, vomiting, headache, amnesia. |

- |

|

Jeanmonod, 2019 |

geriatric patients (aged ≥ 65) presenting to 3 Eds with a chief complaint of fall (n=711) |

Multiple logistic regression analysis. |

Age ≥ 80, LOC, signs of head trauma. |

- |

|

Mishra, 2017 |

Patient with head injury with GCS 15 (n=453) |

Logistic regression analysis was applied to arrive at the equation to find the probability of having an abnormal head CT scan based on the clinical predictors. |

Duration since injury is 6 hours or less, vomiting or a combination of LOC/vomiting/bleeding/seizure. |

Duration since injury is 6 hours or less. |

|

Pöyry, 2013 |

Patients with traumatic brain injury and ground-level falls (n=575) |

Multivariable logistic regression analysis to assess factors significantly associated with acute positive head CT. |

- |

- |

|

Sadegh, 2016 |

Patients medium- or high-risk minor head injury (n=500) |

Stepwise linear regression after univariate analysis to assess the association between each risk factor and an abnormal CT scan. |

GCS < 15, signs of baseal skull fracture, drug history of warfarin, vomiting > 1, LOC, focal neurologic deficit, age > 65. |

- |

|

Zhang, 2017 |

Patients with initially diagnosed mTBI in the emergency department (n=13327) |

Logistic multivariate regression analysis to assess factors significantly associated with intracranial injury. |

Age, anisocoria, nausea/vomiting, skull fracture. |

Anisocoria |

|

Yuksen, 2018 |

Patients aged > 15 years and having received a head CT scan after presenting with mild TBI (n=708). |

Multivariable logistic regression to assess clinical predictors for positive head CT with discriminate performance. |

Posttraumatic vomiting more than 2 times, severe headache, transient loss of consciousness, posttraumatic amnesia, focal neurological signs, clinical signs of skull fracture, base of skull fracture. |

- |

|

Need for neurosurgical intervention |

||||

|

Fabbri, 2005 |

All patients attending for acute MHI within 24 h from trauma (n=7955) |

Multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis |

GCS 14 or <14 at any time, suspected skull fracture, neurological deficits, vomiting. |

-

|

Abbreviations: LOC, loss of consciousness; INR, internal normalized ratio; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; ISS, injury severity score; AIS, abbreviated injury score; MVC, motor vehicle crash; ICH, intracranial haemorrhage; TAO, thromboangiitis obliterans

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence was not assessed because it is a descriptive overview of the literature. No GRADE assessment could be performed since no studies were included with at least internal validation of the prediction models.

Antiplatelet medication and anticoagulation as a criterium for CT scanning

Outcome Need for neurosurgical intervention (critical)

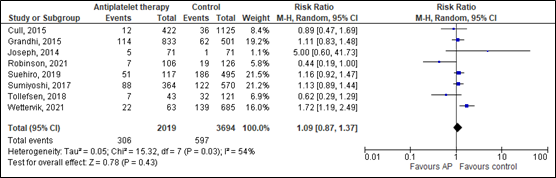

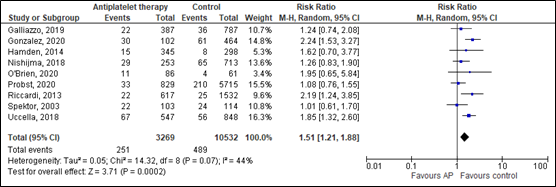

The systematic review of Cheng (2022) compared the need for neurosurgical intervention between patients with mild, moderate and severe TBI on antiplatelet medication and patients with TBI without antiplatelet medication in eight studies (n=2437). Data resulted in a RR of 1.09 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.37) favoring the intervention group receiving antiplatelet therapy (figure 17). This effect was considered clinically relevant (although non-significant).

Figure 17. Effects of antiplatelet therapy (AP) on the need to neurosurgical intervention compared to controls.

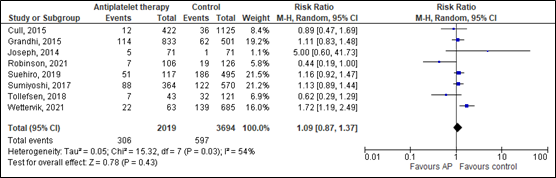

The systematic review of Santing (2022) assessed the need for neurosurgical intervention in elderly mTBI patients using direct oral anticoagulants (DOACS) versus elderly mTBI patients using no antithrombotic therapy in four studies (n=224). Data resulted in a RR of 0.84 (95% CI 0.25 to 2.88) favoring the intervention group receiving DOACS (figure 18). This effect was considered clinically relevant (although non-significant).

Figure 18. Effects of DOACS on the need to neurosurgical intervention compared to controls.

Outcome Intracranial injury (critical)

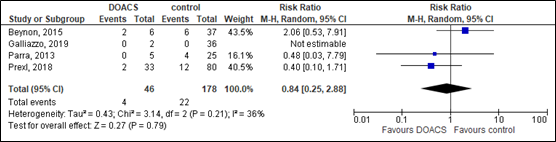

The systematic review of Fiorelli (2020) compared incidence of intracranial injury between patients with TBI on antiplatelet medication and patients with TBI without antiplatelet medication in nine studies (n=13791). Data resulted in a RR of 1.51 (95% CI 1.21 to 1.88) favoring the control group (figure 19). This significant difference was considered clinically relevant.

In addition, Fiorelli (2020) performed a subgroup analysis for the patients taking aspirin alone and for patients on dual antiplatelet therapy. In the aspirin subgroup, data resulted in a RR 1.27 (95% CI 1.00 – 1.61) favoring the control group. In the dual antiplatelet therapy subgroup, data resulted in an RR of 3.21 (95% 2.15 – 4.76) favoring the control group. These (borderline) significant differences were considered clinically relevant. Since the review only showed the pooled effects of these subgroup analyses, no forest plot was created.

Figure 19. Effects of antiplatelet therapy on the incidence of intracranial injury compared to controls.

The level of evidence in the literature

For both outcome measures, the level of evidence started at high because it was based on two systematic reviews with prognostic observational studies.

Outcome Need for neurosurgical intervention (critical)

Antiplatelet therapy

The level of evidence was downgraded by four levels due to retrospective design of all included studies, causing selection bias (-1, risk of bias); confidence intervals crossing both borders of clinical relevance (-2, imprecision); and indirect evidence for the effects of antiplatelet medication in mild TBI specifically (-1, indirectness). The final level is very low.

DOACS

The level of evidence was downgraded by four levels due to retrospective design of all included studies, causing selection bias (-1, risk of bias); confidence intervals crossing both borders of clinical relevance (-2, imprecision); and indirect evidence for the effects of antiplatelet medication in mild TBI specifically (-1, indirectness). The final level is very low.

Outcome Intracranial injury (critical)

Antiplatelet therapy

The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to the retrospective design of half of the included studies, a lack of analyzing potential confounders and the lack of evaluating the risk of intracranial injury in patients who did not receive a CT scan (-2, risk of bias). The final level is low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

1. What is the diagnostic accuracy of clinical decision rules for determining whether a CT scan is needed in patients with mTBI within 24h after the accident for identifying intracranial injury and/or need for neurosurgery?

| P: | Adult patients with mTBI within 24 hours after accident; |

| I: |

Clinical decision rules: The Canadian CT Head Rule (CCHR), New Orleans criteria (NOC), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Scandinavian guideline, National Emergency X-Radiography Utilisation Study II (NEXUS-II) and CT in Head Injury Patients (CHIP); |

| C: | CT scanning based on coincidence/decision by the doctor; |

| R: |

CT scanning applied to all patients; |

| O: |

Diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, true positives, false negatives, false positives and true negative) for need for neurosurgery or intracranial injury. |

Timing and setting: emergency physician, radiologist, neurologist within 24 hours after mTBI.

2. Is the use of new anticoagulants (DOACS), low molecular wight heparins in therapeutic doses, clopidogrel and combinations of platelet aggregation inhibitors associated with an increased risk for intracranial complications or need for neurosurgical interventions after mTBI within 24h after the accident?

| P: | Adult patients with mTBI within 24 hours after accident; |

| I: | Use of new anticoagulants (DOACS), low molecular wight heparins in therapeutic doses, clopidogrel and combinations of platelet aggregation inhibitors; |

| C: | no use of new anticoagulants (DOACS), low molecular wight heparins in therapeutic doses, clopidogrel and combinations of platelet aggregation inhibitors; |

| O: | Need for neurosurgical intervention, intracranial injury |

Timing and setting: emergency physician, radiologist, neurologist within 24 hours after mTBI.

Relevant outcome measures

- The guideline development group considered sensitivity as a critical outcome measure for decision making and specificity as an important outcome measure for decision making. Sensitivity was considered clinically accurate when being ≥95% for the outcome neurosurgical intervention. No minimally clinical accuracy of specificity was determined. For intracranial injury, no minimally important differences for sensitivity and specificity were determined.

- The guideline development group considered need for neurosurgical intervention as a critical outcome measure for decision making. Intracranial injury was considered important. For both outcomes, a relative difference of 3% was considered clinically relevant (risk ratio (RR) of < 0.97 or > 1.03).

Search and select (Methods)

- The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were first searched for systematic reviews with relevant search terms from 2000 until August 9th, 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 95 systematic reviews, 507 studies were labeled as RCTs and 635 as observational studies.

A total of 60 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 38 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 22 studies were included.

Studies were divided into the following categories:

1. Diagnostic performance studies about the performance of validated clinical decision rules to identify intracranial injury or neurosurgical intervention.

2. Diagnostic impact studies about the impact of applying validated clinical decision rules on patient relevant outcome measures.

3. Association studies about the relationship between clinical criteria and intracranial injury or neurosurgical intervention. The level of evidence was not assessed because it is a descriptive overview of the literature. No GRADE assessment could be performed since no studies were included with at least internal validation of the prediction models. Thus, no risk of bias nor evidence tables were included for this part of the literature overview. - The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched for systematic reviews with relevant search terms from 2000 until May 19th, 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 72 systematic reviews. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic reviews including a systematic evaluation of all included studies (meta-analysis) and risk of bias assessment;

- Including adult (16+ years) patients with mild traumatic brain injury using antiplatelet medication before injury;

- Described at least one of the outcome measures as described in the PICO;

- Included at least 20 patients.

Five studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, two studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and three systematic reviews were included.

Results

- Clinical decision rules and additional criteria for CT scanning: 22 studies were included in the analysis of the literature:

a. Diagnostic performance studies: Two systematic reviews and four observational studies.

b. Diagnostic impact studies: One non-randomized controlled trial.

c. Association studies: 19 observational studies. - Antiplatelet medication and anticoagulation as a criterium for CT scanning: three systematic reviews were included in the analysis of the literature.

Referenties

- van den Brand, C. L., Foks, K. A., Lingsma, H. F., van der Naalt, J., Jacobs, B., de Jong, E., den Boogert, H. F., Sir, Ö., Patka, P., Polinder, S., Gaakeer, M. I., Schutte, C. E., Jie, K. E., Visee, H. F., Hunink, M. G., Reijners, E., Braaksma, M., Schoonman, G. G., Steyerberg, E. W., Dippel, D. W., … Jellema, K. (2022). Update of the CHIP (CT in Head Injury Patients) decision rule for patients with minor head injury based on a multicenter consecutive case series. Injury, 53(9), 2979–2987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2022.07.001

- van den Brand, C. L., van der Naalt, J., Hageman, G., Bienfait, H. P., van der Kruijk, R. A., & Jellema, K. (2017). Addendum richtlijn licht traumatisch hoofd-hersenletsel [Addendum to the Dutch guideline for minor head/brain injury]. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde, 161, D2258.

- Brewer, E. S., Reznikov, B., Liberman, R. F., Baker, R. A., Rosenblatt, M. S., David, C. A., & Flacke, S. (2011). Incidence and predictors of intracranial hemorrhage after minor head trauma in patients taking anticoagulant and antiplatelet medication. The Journal of trauma, 70(1), E1–E5. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e5e286

- Cheng, L., Cui, G., & Yang, R. (2022). The Impact of Preinjury Use of Antiplatelet Drugs on Outcomes of Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in neurology, 13, 724641. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.724641

- Claudia, C., Claudia, R., Agostino, O., Simone, M., & Stefano, G. (2011). Minor head injury in warfarinized patients: indicators of risk for intracranial hemorrhage. The Journal of trauma, 70(4), 906–909. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3182031ab7

- Fabbri, A., Servadei, F., Marchesini, G., Stein, S. C., & Vandelli, A. (2010). Predicting intracranial lesions by antiplatelet agents in subjects with mild head injury. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 81(11), 1275–1279. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2009.197467

- Fabbri, A., Servadei, F., Marchesini, G., Dente, M., Iervese, T., Spada, M., & Vandelli, A. (2005). Clinical performance of NICE recommendations versus NCWFNS proposal in patients with mild head injury. Journal of neurotrauma, 22(12), 1419–1427. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2005.22.1419

- Fiorelli, E. M., Bozzano, V., Bonzi, M., Rossi, S. V., Colombo, G., Radici, G., Canini, T., Kurihara, H., Casazza, G., Solbiati, M., & Costantino, G. (2020). Incremental Risk of Intracranial Hemorrhage After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Patients on Antiplatelet Therapy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of emergency medicine, 59(6), 843–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.07.036

- Foks, K. A., van den Brand, C. L., Lingsma, H. F., van der Naalt, J., Jacobs, B., de Jong, E., den Boogert, H. F., Sir, Ö., Patka, P., Polinder, S., Gaakeer, M. I., Schutte, C. E., Jie, K. E., Visee, H. F., Hunink, M. G. M., Reijners, E., Braaksma, M., Schoonman, G. G., Steyerberg, E. W., Jellema, K., … Dippel, D. W. J. (2018). External validation of computed tomography decision rules for minor head injury: prospective, multicentre cohort study in the Netherlands. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 362, k3527. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k3527

- Harnan, S. E., Pickering, A., Pandor, A., & Goodacre, S. W. (2011). Clinical decision rules for adults with minor head injury: a systematic review. The Journal of trauma, 71(1), 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e31820d090f

- Holmes, M. W., Goodacre, S., Stevenson, M. D., Pandor, A., & Pickering, A. (2012). The cost-effectiveness of diagnostic management strategies for adults with minor head injury. Injury, 43(9), 1423–1431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2011.07.017

- Ibañez, J., Arikan, F., Pedraza, S., Sánchez, E., Poca, M. A., Rodriguez, D., & Rubio, E. (2004). Reliability of clinical guidelines in the detection of patients at risk following mild head injury: results of a prospective study. Journal of neurosurgery, 100(5), 825–834. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2004.100.5.0825

- Ibañez Pérez De La Blanca, M. A., Fernández Mondéjar, E., Gómez Jimènez, F. J., Alonso Morales, J. M., Lombardo, M. D. Q., & Viso Rodriguez, J. L. (2018). Risk factors for intracranial lesions and mortality in older patients with mild traumatic brain injuries. Brain injury, 32(1), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2017.1382716

- Jeanmonod, R., Asher, S., Roper, J., Vera, L., Winters, J., Shah, N., Reiter, M., Bruno, E., & Jeanmonod, D. (2019). History and physical exam predictors of intracranial injury in the elderly fall patient: A prospective multicenter study. The American journal of emergency medicine, 37(8), 1470–1475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.10.049

- Laic, R. A. G., Verhamme, P., Vander Sloten, J., & Depreitere, B. (2023). Long-term outcomes after traumatic brain injury in elderly patients on antithrombotic therapy. Acta neurochirurgica, 165(5), 1297–1307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-023-05542-5

- Lecky, F. E., Otesile, O., Marincowitz, C., Majdan, M., Nieboer, D., Lingsma, H. F., Maegele, M., Citerio, G., Stocchetti, N., Steyerberg, E. W., Menon, D. K., Maas, A. I. R., & CENTER-TBI Participants and Investigators (2021). The burden of traumatic brain injury from low-energy falls among patients from 18 countries in the CENTER-TBI Registry: A comparative cohort study. PLoS medicine, 18(9), e1003761. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003761

- Mishra, R. K., Munivenkatappa, A., Prathyusha, V., Shukla, D. P., & Devi, B. I. (2017). Clinical predictors of abnormal head computed tomography scan in patients who are conscious after head injury. Journal of neurosciences in rural practice, 8(1), 64–67. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-3147.193538

- Mower, W. R., Gupta, M., Rodriguez, R., & Hendey, G. W. (2017). Validation of the sensitivity of the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) Head computed tomographic (CT) decision instrument for selective imaging of blunt head injury patients: An observational study. PLoS medicine, 14(7), e1002313. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002313

- Pandor, A., Goodacre, S., Harnan, S., Holmes, M., Pickering, A., Fitzgerald, P., Rees, A., & Stevenson, M. (2011). Diagnostic management strategies for adults and children with minor head injury: a systematic review and an economic evaluation. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England), 15(27), 1–202. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta15270

- Papa, L., Stiell, I. G., Clement, C. M., Pawlowicz, A., Wolfram, A., Braga, C., Draviam, S., & Wells, G. A. (2012). Performance of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria for predicting any traumatic intracranial injury on computed tomography in a United States Level I trauma center. Academic emergency medicine: official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 19(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01247.x

- Pöyry, T., Luoto, T. M., Kataja, A., Brander, A., Tenovuo, O., Iverson, G. L., & Öhman, J. (2013). Acute assessment of brain injuries in ground-level falls. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation, 28(2), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0b013e318250eadd

- Sadegh, R., Karimialavijeh, E., Shirani, F., Payandemehr, P., Bahramimotlagh, H., & Ramezani, M. (2016). Head CT scan in Iranian minor head injury patients: evaluating current decision rules. Emergency radiology, 23(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-015-1349-y

- Santing, J. A. L., Lee, Y. X., van der Naalt, J., van den Brand, C. L., & Jellema, K. (2022). Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Elderly Patients Receiving Direct Oral Anticoagulants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of neurotrauma, 39(7-8), 458–472. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2021.0435

- Smits, M., Dippel, D. W., Nederkoorn, P. J., Dekker, H. M., Vos, P. E., Kool, D. R., van Rijssel, D. A., Hofman, P. A., Twijnstra, A., Tanghe, H. L., & Hunink, M. G. (2010). Minor head injury: CT-based strategies for management--a cost-effectiveness analysis. Radiology, 254(2), 532–540. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2541081672

- Spektor, S., Agus, S., Merkin, V., & Constantini, S. (2003). Low-dose aspirin prophylaxis and risk of intracranial hemorrhage in patients older than 60 years of age with mild or moderate head injury: a prospective study. Journal of neurosurgery, 99(4), 661–665. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2003.99.4.0661

- Stiell, I. G., Clement, C. M., Grimshaw, J. M., Brison, R. J., Rowe, B. H., Lee, J. S., Shah, A., Brehaut, J., Holroyd, B. R., Schull, M. J., McKnight, R. D., Eisenhauer, M. A., Dreyer, J., Letovsky, E., Rutledge, T., Macphail, I., Ross, S., Perry, J. J., Ip, U., Lesiuk, H., … Wells, G. A. (2010). A prospective cluster-randomized trial to implement the Canadian CT Head Rule in emergency departments. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne, 182(14), 1527–1532. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.091974

- Vedin, T., Svensson, S., Edelhamre, M., Karlsson, M., Bergenheim, M., & Larsson, P. A. (2019). Management of mild traumatic brain injury-trauma energy level and medical history as possible predictors for intracranial hemorrhage. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery: official publication of the European Trauma Society, 45(5), 901–907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-018-0941-8

- de Wit, K., Parpia, S., Varner, C., Worster, A., McLeod, S., Clayton, N., Kearon, C., & Mercuri, M. (2020). Clinical Predictors of Intracranial Bleeding in Older Adults Who Have Fallen: A Cohort Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(5), 970–976. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16338

- Yuksen, C., Sittichanbuncha, Y., Patumanond, J., Muengtaweepongsa, S., & Sawanyawisuth, K. (2018). Clinical predictive score of intracranial hemorrhage in mild traumatic brain injury. Therapeutics and clinical risk management, 14, 213–218. https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S147079

- Zhang, J., Xu, J., Shen, Y., Xu, Y. (2017). Risk factors for intracranial injury diagnosed by cranial CT in emergency department patients with mTBI. Int. Clin. Exp. Med, 10(7), 10995-11000

Evidence tabellen

Table of excluded studies

- Clinical decision rules and additional criteria for CT scanning

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Alzuhairy A. (2020). Accuracy of Canadian CT Head Rule and New Orleans Criteria for Minor Head Trauma; a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Archives of academic emergency medicine, 8(1), e79. |

Wrong study goal (diagnostic study). |

|

Arab, A. F., Ahmed, M. E., Ahmed, A. E., Hussein, M. A., Khankan, A. A., & Alokaili, R. N. (2015). Accuracy of Canadian CT head rule in predicting positive findings on CT of the head of patients after mild head injury in a large trauma centre in Saudi Arabia. The neuroradiology journal, 28(6), 591–597. https://doi.org/10.1177/1971400915610699 |

Wrong outcome measures (data not presented as TP, FN, TN and TN). |

|

Beynon, C., Potzy, A., Sakowitz, O. W., & Unterberg, A. W. (2015). Rivaroxaban and intracranial haemorrhage after mild traumatic brain injury: A dangerous combination? Clinical neurology and neurosurgery, 136, 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2015.05.035 |

Wrong study goal (risk of intracranial injury between different medication types assessed) |

|

Borg, J., Holm, L., Cassidy, J. D., Peloso, P. M., Carroll, L. J., von Holst, H., Ericson, K., & WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (2004). Diagnostic procedures in mild traumatic brain injury: results of the WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of rehabilitation medicine, (43 Suppl), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/16501960410023822 |

Wrong study goal (diagnostic study). |

|

Bouida, W., Marghli, S., Souissi, S., Ksibi, H., Methammem, M., Haguiga, H., Khedher, S., Boubaker, H., Beltaief, K., Grissa, M. H., Trimech, M. N., Kerkeni, W., Chebili, N., Halila, I., Rejeb, I., Boukef, R., Rekik, N., Bouhaja, B., Letaief, M., & Nouira, S. (2013). Prediction value of the Canadian CT head rule and the New Orleans criteria for positive head CT scan and acute neurosurgical procedures in minor head trauma: a multicenter external validation study. Annals of emergency medicine, 61(5), 521–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.07.016 |

Wrong population (aged ≥ 10) |

|

Van den Brand, C. L., Rambach, A.A.H.J.H., Postma, R., van de Craats, V.L., Lengers, F., Bénit, C.P., Verbree, F.C., Jellema, K. (2014). Richtlijn ‘Licht traumatisch hoofd-hersenletsel’ in de praktijk. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd.; 158:A6973 |

Wrong study design (evaluation of the previous version of this guideline) |

|

van den Brand, C. L., Tolido, T., Rambach, A. H., Hunink, M. G., Patka, P., & Jellema, K. (2017). Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Is Pre-Injury Antiplatelet Therapy Associated with Traumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage?. Journal of neurotrauma, 34(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2015.4393 |

Wrong population (antiplatelet therapy). |

|

Davey, K., Saul, T., Russel, G., Wassermann, J., & Quaas, J. (2018). Application of the Canadian Computed Tomography Head Rule to Patients With Minimal Head Injury. Annals of emergency medicine, 72(4), 342–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.03.034 |

Wrong outcome measures (data not presented as TP, FN, TN and TN). |

|

Easter, J. S., Haukoos, J. S., Meehan, W. P., Novack, V., & Edlow, J. A. (2015). Will Neuroimaging Reveal a Severe Intracranial Injury in This Adult With Minor Head Trauma?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review. JAMA, 314(24), 2672–2681. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.16316 |

Supplementary data not available. |

|

Fournier, N., Gariepy, C., Prévost, J. F., Belhumeur, V., Fortier, É., Carmichael, P. H., Gariepy, J. L., Le Sage, N., & Émond, M. (2019). Adapting the Canadian CT head rule age criteria for mild traumatic brain injury. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ, 36(10), 617–619. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2018-208153 |

Study was included in the selected review. |

|

Fuller, G. W., Evans, R., Preston, L., Woods, H. B., & Mason, S. (2019). Should Adults With Mild Head Injury Who Are Receiving Direct Oral Anticoagulants Undergo Computed Tomography Scanning? A Systematic Review. Annals of emergency medicine, 73(1), 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.07.020 |

Wrong study design (descriptive study). |

|

Franschman, G., Boer, C., Andriessen, T. M., van der Naalt, J., Horn, J., Haitsma, I., Jacobs, B., & Vos, P. E. (2012). Multicenter evaluation of the course of coagulopathy in patients with isolated traumatic brain injury: relation to CT characteristics and outcome. Journal of neurotrauma, 29(1), 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2011.2044 |

Wrong population (moderate and severe TBI patients) |

|