Diagnostiek lagere luchtweginfectie

Uitgangsvraag

Wordt point-of-care-ultrasound (POCUS) als add-on of vervanging aanbevolen voor het diagnosticeren van lagere luchtweginfectie bij kinderen (0-16 jaar) met koorts op de Spoedeisende Hulp?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg bij beschikbaarheid POCUS van de longen, indien beschikbaar als sneldiagnostiek op de SEH, als alternatief voor X-thorax om een pneumonie uit te sluiten bij patiënten met koorts zonder duidelijke focus. Overweeg POCUS van de longen te gebruiken om een pneumonie aan te tonen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Op basis van drie systematische reviews en een observationele studie is het niet overduidelijk wat de diagnostische waarde van POCUS is bij het diagnosticeren van een lagere luchtweginfectie. Er waren grote verschillen tussen de populaties in de studies (prevalentie pneumonie 23-100%) en de te verwachten patiëntenpopulatie op een Nederlandse SEH-afdeling (verwachte prevalentie pneumonie 5%). Uiteindelijk presenteert POCUS van de longen gelijkwaardig aan een thoraxfoto, maar de bewijskracht hiervoor is zeer laag.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Op basis van de studies die POCUS van de longen met een thoraxfoto hebben vergeleken al dan niet in combinatie met kliniek voor de diagnose pneumonie lijkt POCUS vergelijkbare diagnostische waarde te hebben als de thoraxfoto. Daarbij heeft POCUS het voordeel dat het laagdrempelig ingezet kan worden met zeer beperkte belasting voor de patiënt, met name minder stralingsbelasting. Op basis van de huidige studies kan er geen conclusie getrokken worden dat POCUS beter is dan een thoraxfoto in het vaststellen van een pneumonie, noch om de indicatie voor beeldvorming bij verdenking pneumonie bij koorts scherper te stellen. Er zijn geen subgroepen bekend die het gebruik van POCUS van de longen anders zouden kunnen ervaren. POCUS maakt geen onderscheid tussen bacteriële of virale infectie van de longen, waardoor daar niet mee bepaald kan worden of er antibiotica gestart moet worden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Op de meeste spoedeisende hulpen is er tegenwoordig een echoapparaat beschikbaar met de benodigde echokoppen om POCUS van de longen te kunnen uitvoeren. Daarom hoeft er op dit vlak geen aanvullende investering gedaan worden. Het belangrijkste middelenbeslag zit in het opleiden van artsen en/of physician assistants om POCUS van de longen betrouwbaar uit te kunnen voeren. Mogelijke reductie van kosten bestaat uit dat er potentieel minder ander aanvullend onderzoek wordt ingezet. Echter, voor deze bewering is geen wetenschappelijke onderbouwing bekend bij de werkgroep, noch blijkt dit uit de vermelde studies. Er zijn geen subgroepen bekend waarvoor andere argumenten gelden.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er is geen kwantitatief of kwalitatief onderzoek gedaan naar de aanvaardbaarheid en haalbaarheid van POCUS van de longen. Echter, er is wel veel ervaring met POCUS in kader van andere ziektebeelden op de spoedeisende hulp waaruit blijkt dat het aanvaardbaar en haalbaar is.

De belangrijkste beperking van implementatie van POCUS van de longen zit hem in de beperkte ervaring om een pneumonie ermee aan te tonen of uit te sluiten. Om POCUS van de longen betrouwbaar uit te voeren is kennis en ervaring met POCUS van de longen nodig. De geïdentificeerde studies tonen heterogeniteit in ervaring en training. De studie van Zhan (2016) heeft één arts-assistent met beperkte ervaring en training met POCUS van de longen waardoor die in vergelijking tot de andere studies een opvallend lagere NPV en PPV heeft.

In principe heeft iedere patiënt toegang tot POCUS mits er een echoapparaat beschikbaar is op de spoedeisende hulp en er een geschoolde zorgverlener aanwezig is die de POCUS kan uitvoeren. Een mogelijk voordeel van POCUS van de longen is dat er eventueel ook complicaties van de pneumonie aangetoond kunnen worden zoals longeffusie of een pneumothorax, maar dit valt buiten het bestek van deze richtlijn

De geïncludeerde studies hebben POCUS van de longen uitgevoerd bij patiënten met verdenking pneumonie en met variatie in de regio’s van de thorax die onderzocht zijn. Bij de populatie die onder deze richtlijn valt is er sprake van koorts zonder evident focus. Gezien de screenende functie van POCUS van de longen in de populatie met koorts zonder evident focus is het advies om de volgende thoracale regionen beiderzijds te onderzoeken: anterieur, lateraal en posterieur. Bij patiënten met thoraxdeformiteiten of een voorgeschiedenis van longschade (bv. longfibrose) moeten de resultaten mogelijk anders geïnterpreteerd worden.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Indien er sprake is van een reële verdenking voor pneumonie na de initiële work-up dan dient de NVK richtlijn onderste luchtweginfecties gevolgd te worden.

POCUS van de longen lijkt een aanvullende waarde te hebben in het aantonen van een pneumonie in patiënten met koorts zonder duidelijk focus die zich presenteren op de SEH, waarbij de positief voorspellende waarde varieert tussen 0.20 en 1.00, afhankelijk van de prevalentie. Deze brede spreiding wordt grotendeels veroorzaakt door de studie van Zhan (2016), waarbij de POCUS van de longen door een arts-assistent wordt uitgevoerd met zeer beperkte ervaring in POCUS. Bij uitsluiting van deze studie is de range van de positief voorspellende waarde 0.46-1.00.

POCUS van de longen lijkt zeer betrouwbaar om een pneumonie uit te sluiten met een negatief voorspellende waarde van 0.90-1.00 (afhankelijk van de prevalentie).

Bovenstaande resultaten worden beïnvloed door de kennis en ervaring van diegene die de POCUS uitvoert; en welke delen van de thorax in beeld worden gebracht (met name de thorax anterieur, lateraal en posterieur). Derhalve dient POCUS van de longen uitgevoerd te worden door een gecertificeerd zorgverlener.

Concluderend kan POCUS van de longen aanvullend uitgevoerd worden als sneldiagnostiek op de SEH om een pneumonie uit te sluiten of om richting te geven in waarschijnlijkheid van het hebben van een pneumonie, waarbij aanvullend onderzoek aangepast kan worden aan de bevindingen. Alhoewel de X-thorax lage stralingsbelasting heeft, blijkt POCUS van de longen bij beschikbaarheid een gelijkwaardig alternatief te zijn.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Lagere luchtweginfecties zijn in principe een ontsteking van de longen, en worden klinisch gediagnosticeerd (zie richtlijn onderste luchtweginfecties). Meestal wordt er alleen aanvullend beeldvormend onderzoek verricht indien er geen duidelijk focus is voor de koorts of aanwijzingen zijn voor complicaties. Vaak wordt er dan gekozen om een X-thorax te vervaardigen. Thans zijn er in de literatuur aanwijzingen dat POCUS van de longen ook gebruikt kan worden om een pneumonie te diagnosticeren. Het voordeel van gebruik van POCUS ten opzichte van een X-thorax is dat het kind niet aan röntgenstraling blootgesteld wordt en/of diagnostisch accurater is dan een X-thorax om een pneumonie te diagnosticeren. De aanvullende diagnostische waarde van POCUS bij patiënten van 0 – 16 jaar met koorts zonder duidelijk focus na anamnese en lichamelijk onderzoek is heden onduidelijk.

De vraag in deze module is of POCUS van de longen van toegevoegde waarde is om een pneumonie te diagnosticeren of uit te sluiten. En welke aspecten belangrijk zijn bij implementatie van deze techniek in de routine zorg.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Very low GRADE |

The diagnostic value of point-of-care lung ultrasound in diagnosing lower respiratory tract infections in children (0-16 years old) presenting to a Dutch emergency department with fever without a clear source is unclear.

Sources: Wang, 2019; Orso, 2018; Pereda, 2015; Çağlar, 2019; Amatya, 2023 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Wang (2019) performed a systematic review comparing the accuracy of lung ultrasonography with chest radiography in diagnosing community acquired pneumonia (CAP) in children. They searched PubMed and Embase databases up to December 2018, and included studies reporting results from children (<18 years) with clinically suspected CAP in emergency department settings, which included data from both lung ultrasonography and chest radiography, with a clinical reference standard, reporting the frequency of true-positive, false-positive, true-negative and false-negative observations. They excluded editorials, letters, comments, reviews, conference abstracts, and case reports. In total, they included six studies, three of which we excluded: Ianniello (2016) was a retrospective study, Guerra (2016) and Biagi (2018) did not report the frequency of true-positive, false-positive, true-negative and false-negative observations as compared to a reference standard. Three studies included in Wang (2019) (Boursiani, 2017; Copetti, 2008; Yilmaz, 2017, total n=308) were deemed relevant for this guideline.

Orso (2018) performed a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of lung ultrasonography in diagnosing pneumonia in children. They searched Medline, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, SPORTDiscus, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science databases up to September 2017 for published papers including patients under 18 in any hospital department or setting. They excluded conference abstracts, reviews, studies written

in languages other than English, study protocols, policy statements, and guidelines. They also excluded studies that included diagnoses other than pneumonia. They included 17 studies, three of which (Samson, 2016; Shah, 2013; Zhan, 2016, total n=573) were deemed relevant for this guideline. Boursiani (2017), Yilmaz (2017), and Copetti (2008) were included in Wang (2019). Nine studies were excluded: Iorio (2015) and Man (2017) were retrospective studies, Liu (2014) was a case-control study, Caiulo (2013), Claes (2016), Ellington (2017), Urbankowska (2015), Esposito (2014), and Reali (2014) were performed in inpatient settings, Ambroggio (2016) did not report setting.

Pereda (2015) performed a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of lung ultrasonography in diagnosing pneumonia in children. They searched PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, Scopus, Global Health, World Health Organization–Libraries, and Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature databases up to July 2014. They included studies including children with suspected pneumonia and/or pneumonia confirmed with chest radiography or CT. Studies that enrolled adults (≥18 years), conference abstracts, and unpublished studies were not included. In total Pereda (2015) included eight studies in their meta-analysis, one of which (Iuri, 2009, total n=28) was relevant for this guideline and not included in Wang (2019) or Orso (2018).

Çağlar (2019) conducted a prospective observational study aiming to test the diagnostic accuracy of lung ultrasonography in diagnosing pneumonia in children in emergency settings. They included patients under 18 years who attended a pediatric emergency department in Turkey with suspected pneumonia (n=91, median age 3.0 years, IQR 1.0-5.0). Patients with chronic pulmonary disease, external thoracic wall malformations, thoracic trauma, congenital lung malformations, and patients who did not undergo both chest radiography and lung ultrasonography were excluded. Lung ultrasonography was evaluated against the reference standard, which was defined as clinical symptoms (temperature >38°C cough; tachypnea; dyspnea; retractions; nasal flaring; grunting; wheezing; and pulse oximetry measurement <90%) or chest radiography findings (alveolar, interstitial, mixed pneumonia) indicating pneumonia. The reference standard was assessed by an emergency pediatrician blinded to lung ultrasonography findings. Lung ultrasonography was performed by a different emergency pediatrician, blinded to clinical and chest radiography findings. It was unclear if the authors included a consecutive sample of patients, and also unclear how many patients were screened and excluded from the study, resulting in risk of bias.

Amatya (2023) conducted a prospective cross-sectional study of children presenting in the ED with respiratory complaints in Nepal. Children aged under 5 years who presented with cough, fever or difficulty breathing and received a conventional radiograph of the chest were included. A bedside lung ultrasound was performed on all children prior to chest X-ray being performed. The reference standard was conventional radiograph of the chest. A total of 360 children were included. The median age was 16,5 months (IQR 22) with 57.3% male.

Results

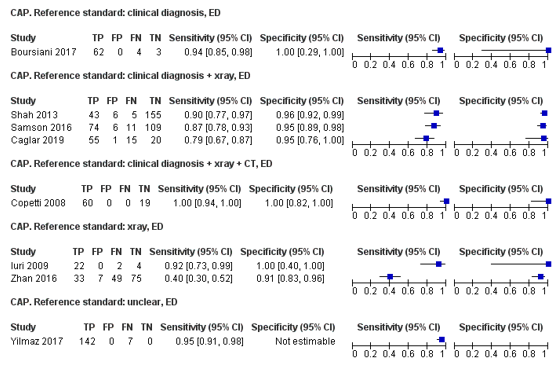

Sensitivity and specificity of POCUS in diagnosing community acquired pneumonia (CAP) in emergency department settings

Boursiani (2017) used clinical diagnosis as reference standard in an emergency department sample, and reported a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 100%. Prevalence of CAP was 96%.

Three studies used clinical diagnosis supported by chest radiography findings as reference standard in emergency department samples, and reported sensitivities ranging from 79% (Çağlar, 2019) to 90% (Shah, 2013), and specificities ranging from 95% (Samson, 2016; Çağlar, 2019) to 96% (Shah, 2013). Prevalence of CAP ranged from 23% (Shah, 2013) to 77% (Çağlar, 2019).

Copetti (2008) used clinical diagnosis supported by chest radiography and chest CT findings as reference standard in an emergency department sample, and reported a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 100%. Prevalence of CAP was 76%.

Two studies used chest radiography findings as reference standard in emergency department samples, and reported sensitivities ranging from 40% (Zhan, 2016) to 92% (Iuri, 2009), and specificities ranging from 91% (Zhan, 2016) to 100% (Iuri, 2009). Prevalence of CAP ranged from 50% (Zhan, 2016) to 86% (Iuri, 2009).

Amatya (2023) used conventional radiograph of the chest as reference standard and reported a sensitivity of 89.3% (95% CI 81-95)% and specificity of 86.1% (95% CI 82-90). The prevalence of CAP was 23%.

Figure 1. Sensitivity and specificity of lung ultrasonography in emergency settings

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures sensitivity and specificity started high (diagnostic studies) and was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (poorly defined reference standard); and two levels because of applicability (indirectness: great differences between study populations and Dutch ED population), resulting in a very low GRADE.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the diagnostic accuracy of a (point-of-care) lung ultrasound in diagnosing lower respiratory tract infection in children (0-16 years old)?

P: Children (0-16 years) with fever in secondary care, with a possible lower respiratory infection

I: (point-of-care) lung ultrasound

C: -

R: Chest radiograph for pneumonia, PCR for viral infections, CT-scan, sputum culture

O: Diagnostic accuracy in diagnosing lower respiratory tract infection

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value, positive predictive value) for diagnosing a lower respiratory infection as a critical outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined a negative and positive predictive value of 0.80 as thresholds for clinical (patient) importance to give direction to the possible source of the fever and a negative and positive predictive value of 0.95 as thresholds for clinical (patient) importance to utilize POCUS as a definite diagnostic mean.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 18 November 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 245 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, and observational studies of the diagnostic accuracy of a (point of care) lung ultrasound in diagnosing lower respiratory tract infections in children (0-16 years old). Twenty-three studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 19 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and four studies were included.

The search was repeated on 24 March 2023 with the aim to identify landmark studies. None of the newly identified studies are likely to change the conclusion. One study that met the in-/exclusion criteria was identified (Amatya, 2023) and the results of this study were added to the summary of literature.

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Amatya Y, Russell FM, Rijal S, Adhikari S, Nti B, House DR. Bedside lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children presenting to an emergency department in a resource-limited setting. Int J Emerg Med. 2023 Jan 9;16(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12245-022-00474-w. PMID: 36624366; PMCID: PMC9828356.

- Çağlar, A., Ulusoy, E., Er, A., Akgül, F., Çitlenbik, H., Yılmaz, D., & Duman, M. (2019). Is lung ultrasonography a useful method to diagnose children with community-acquired pneumonia in emergency settings?. Hong Kong Journal of Emergency Medicine, 26(2), 91-97.

- Orso, D., Ban, A., & Guglielmo, N. (2018). Lung ultrasound in diagnosing pneumonia in childhood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of ultrasound, 21(3), 183-195.

- Pereda, M. A., Chavez, M. A., Hooper-Miele, C. C., Gilman, R. H., Steinhoff, M. C., Ellington, L. E., ... & Checkley, W. (2015). Lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 135(4), 714-722.

- Wang, L., Song, W., Wang, Y., Han, J., & Lv, K. (2019). Lung ultrasonography versus chest radiography for the diagnosis of pediatric community acquired pneumonia in emergency department: a meta-analysis. Journal of thoracic disease, 11(12), 5107.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics

|

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Balk, 2018

(individual)Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise)

|

SR and meta-analysis (MA)

Literature search up to August 2017

12 studies included: A: Boursiani, 2017 B: Caiulo, 2013 C: Copetti, 2008 D: Dianova, 2015 E: Guerra, 2016 F: Ho, 2015 G: Ianniello, 2016 H: Iorio, 2015 I: Reali, 2014 J: Shah, 2013 K: Yadav, 2017 L: Yilmaz, 2017

>90% prevalence

Study design: MA of observational studies: - 9 prospective: A-E, I-L - 3 retrospective: F-H

Setting: - 6 emergency department: A, C, E, G, J, L - 6 inpatient: B, D, F, H, I, K

Countries: Greece: A Italy: B, C, E, G-I Russia: D Taiwan: F USA: J India: K Turkey: L

MA authors are from USA and Israel

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Unspecified for both SR and included studies.

|

Inclusion criteria SR: - pediatric patients (<18), - bacterial pediatric community acquired pneumonia (pCAP) assessed - both chest X-ray (CXR) and lung ultrasound (LUS) performed - having a set gold standard of expert pediatrician clinical diagnosis for diagnosis of pCAP

Exclusion criteria SR: - Abstract only publications - Concern for bias based on evaluation with QUADAS tool - Results not of interest to SR

Included: 12 studies with total n = 1510 patients.

Important patient characteristics:

Number of patients: A: 69 B: 102 C: 79 D: 154 E: 222 F: 163 G: 84 H: 52 I: 107 J: 209 K: 118 L: 160 .

Age (Mean): A: 4.5 yrs (median) B: 5 yrs C: 5.1 yrs D: only age-based subgroups with n are provided: 0-3 mo: 14 3 mo-3 yrs: 60 4-7 yrs: 49 7-18 yrs: 31 E: 4.9 yrs F: 6.1 yrs G: 6 yrs H: 3.5 yrs I: 4 yrs J: 3 yrs (median) K: 2.2 yrs L: 3.3 yrs

Sex as % male: A: 39% B: unspecified C: unspecified D: 56% E: unspecified F: 56% G: 52% H: unspecified I: 57% J: 54% K: 55% L: 49% |

Describe index and comparator tests* and cut-off point(s):

The primary objective of this meta-analysis was to evaluate the accuracy of LUS compared to CXR for the diagnosis of pCAP: in all 12 studies (A-L) these tests were compared.

LUS findings considered diagnostic for pCAP: Consolidations: A-L Focal B-Lines: A, B, I, K Pleural line abnormality: B Pleural effusion: K

Lung consolidation, described as an ill-defined, hypoechogenic region communicating with the pleural line, also described as hepatization due to organ-like appearance, is considered diagnostic for pCAP in all the included articles in this meta-analysis. This is described both with and without air bronchograms, defined as hyperechogenic linear abnormalities contained within the consolidation, or fluid bronchograms, defined as hypoechogenic or anechoic linear abnormalities within the consolidation.

All studies evaluated LUS and CXR for the presence of pleural effusion, however this was not independently sufficient for the diagnosis of pCAP in eleven of the twelve studies.

|

Describe reference test and cut-off point(s):

- The reference standard in all studies was expert pediatrician diagnosis based primarily on a clinical course consistent with bacterial pCAP: A-L.

- 8 studies included CXR as part of the reference Standard (a negative CXR did not rule out the diagnosis of pCAP): A-D, G-J

- 2 studies (C, D) included chest computed tomography (CT) in cases where there was diagnostic uncertainty: C, D D: performed chest CT in all patients (28) with clinical diagnosis of bacterial pCAP and a negative CXR; CT was positive in all 28 cases and LUS was positive in 21 of these CXR negative cases.

pCAP prevalence (%): A: 95,7% B: 87,3% C: 75,9% D: 100% E: 96,4% F: 100% G: 72,6% H: 55,8% I: 75,7% J: 23% K: 100% L: 93,1%

Nine of the 12 studies included a subset of patients who were found to be negative for pCAP; the remainder only included patients diagnosed with pCAP

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%) Not reported

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Not reported

|

Endpoint of follow-up: N/A |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

LUS sensitivity (95%CI) / specificity (95%CI) for pCAP A: 93.9% (85.2-98.3) / 100% (29.2-100) B: 98.9% (93.9-100) / 100% (75.3-100) C: 100% (94.0-100) / 100% (82.4-100) D: 95.5% (90.0-98.2) / NA E: 96.7% (93.4-98.7) / 100% (63.1-100) F: 97.5% (93.8-99.3) / NA G: 98.4% (91.2-100) / 100% (85.2-100) H: 96.6% (82.2-99.9) / 95.7% (78.1-99.9) I: 93.8% (86.2-98.0) / 96.2% (80.4-99.9) J: 89.6% (77.3-96.5) / 96.3% (92.1-98.6) K: 89.0% (81.9-94.0) / NA L: 95.3% (90.6-98.1) / 63.6% (30.8-89.1)

Pooled LUS sensitivity (random effects model): 95.5% (93.6-97.1) Heterogeneity (cutoff p < 0.05 to determine inconsistency significance): I2 = 53.7%, not significant.

Pooled LUS specificity (random effects model): 95.3% (91.1-98.3) Heterogeneity (cutoff p < 0.05 to determine inconsistency significance): I2 = 34.4%, not significant.

|

Study quality (ROB): assessed by the authors with the QUADAS-2 tool (individual results not reported).

Eleven studies specified discordance between LUS and CXR results. In total among these 11 studies, there were 112 cases of pCAP found on LUS but not on CXR. There were 35 cases of pCAP identified on CXR but not on LUS.

LUS was performed on all patients by trained sonographers. Sonographers were identified as experts in eight studies. Two studies did not specify sonographer experience: D, G One study included only novice radiologist sonographers following 4 h of LUS training and performance of 15 LUS exams: K One study evaluated both expert and novice pediatric emergency medicine sonographers, with novice being defined as fewer than 25 LUS exams.21 In this study, novices were responsible for four operator errors found on LUS review, two false negatives, and two false positives.

Ten studies used linear probes to perform LUS; five of these used convex probes in addition. One study used only convex probes; one used only microconvex probes.

Technique for lung ultrasound for pCAP was similar across studies.

There was heterogeneity across the studies regarding LUS findings diagnostic for pCAP. These findings included subcentimeter consolidations, focal b-lines, pleural line abnormalities, and pleural effusions.

There was heterogeneity with regard to ages enrolled.

While there is growing evidence for the accuracy of LUS over CXR in the diagnosis of pCAP, more research is needed to define the differentiation between bacterial and viral etiologies. The heterogeneity across studies highlights the need for better understanding of ultrasound findings that fall in this gray zone., including pleural line abnormalities, subcentimeter consolidations, and focal confluent blines. It is important to be able to make the distinction between bacterial and viral etiologies as they are treated very differently.

Article conclusion: This meta-analysis suggests superior sensitivity of LUS over CXR for the diagnosis of pCAP. Despite a significantly better sensitivity, values for specificity, NPV, and PPV were comparable between LUS and CXR. Further studies are needed to evaluate the diagnostic utility of LUS for pCAP without inclusion of CXR as a portion of the reference standard. Additionally, further data is needed regarding the specificity of particular LUS findings for pCAP, namely subcentimeter consolidations, pleural line abnormalities and isolated focal confluent b-lines. |

|

Orso, 2018

(individual)Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis

Literature search up to September 2017

17 studies included: A: Boursiani, 2017 B: Ellington, 2017 C: Man, 2017 D: Yadav, 2017 E: Yilmaz, 2017 F: Ambroggio, 2016 G: Claes, 2016 H: Samson, 2016 I: Zhan, 2016 J: Iorio, 2015 K: Urbankowska, 2015 L: Esposito, 2014 M: Liu, 2014 N: Reali, 2014 O: Shah, 2013 P: Caiulo, 2013 Q: Copetti, 2008

Study design: - 15 prospective: A, B, D-I, K-Q - 2 retrospective: C, J

Setting: 1. Pediatric Emergency Department 2. pediatric ward 3. outpatients 4. radiology department 5. emergency department 6. Pediatric Intensive Care Unit 7. Neonatal Intensive Care Unit 8. Pediatric Pulmenary Department 9: Emergency department 10. Not reported

A: 1 B: 1, 2, 3 C: 2 D: 1, 2, 4 E: 1 F: 10 G: 2 H: 1 I: 1 J: 2 K: 8 L: 6 M: 7 N: 2 O: 9 P: 2 Q: 9

Countries are not reported.

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: No funding mentioned. The authors declare that they have no conflict of Interest. Unspecified for included studies. |

Inclusion criteria SR: - studies that evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of LUS in determining the presence of pneumonia - patients under 18 years of age - any hospital departments or settings - only published articles.

Exclusion criteria SR: - conference abstracts - review articles - other language than English - non-human studies - protocols or policy statements, and guidelines - studies that dealt with other diagnoses besides pneumonia

Included: 17 studies, with total n = 2612 patients.

Important patient characteristics:

Number of patients: A: 69 B: 812 C: 81 D: 118 E: 160 F: 36 G: 143 H: 200 I: 164 J: 52 K: 106 L: 103 M: 80 N: 107 O: 200 P: 102 Q: 79

Age range (months): A: 6-24 B: 2-59 C: Not reported D: 2-59 E: 1-216 F: 3-18 G: 0-192 H: 0-180 I: 0-180 J: Not reported K: 1-? L: 1-168 M: 0-1 N: 0-192 O: 0-252 P: 12-192 Q: 6-192

The age of the pooled sample population ranged from 0 to about 21 years old.

Sex (% male) is not reported. |

LUS

Diagnostic criteria: Consolidations: A-F, H-Q Interstitial pattern: A, F, K, M, N, P Bronchogram: D, E, H, J, L, O, Q Focal B-Lines: D, L, O, Q Not reported: G |

Reference test: - Adjudication: A, N, P - Clinical diagnosis: J, K, M, Q - CXR: B-E, G-I, L, O CT: F

N, prevalence of pneumonia (%): A: 96% B: 52% C: 89% D: 85% E: 93% F: 34% G: 31% H: 43% I: 50% J: 56% K: 71% L: 47% M: 50% N: 76% O: 18% P: 87% Q: 76%

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%) Not reported

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Not reported

|

Endpoint of follow-up: N/A |

LUS sensitivity (interquartile range) / specificity (IQR) for pneumonia: A: 0.94 (0.87, 0.98) / 0.95 (0.60, 1.00) B: 0.90 (0.87, 0.93) / 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) C: 0.80 (0.70, 0.88) / 0.53 (0.24, 0.79) D: 0.97 (0.93, 0.99) / 0.69 (0.47, 0.86 E: 0.96 (0.91, 0.98) / 0.21 (0.06,0.43) F: 0.66 (0.40, 0.86) / 0.76 (0.58, 0.89) G: 0.97 (0.90, 0.99) / 0.92 (0.86, 0.96) H: 0.88 (0.80, 0.93) / 0.95 (0.90, 0.98) I: 0.42 (0.32, 0.53) / 0.91 ( 0.84, 0.96) J: 0.96 (0.86, 0.99) / 0.95 (0.82, 0.99) K: 0.94 (0.87, 0.97) / 0.98 (0.90, 1.00) L: 0.97 (0.90, 0.99) / 0.94 (0.87, 0.98) M: 0.99 (0.93, 1.00) / 0.99 (0.93, 1.00) N: 0.94 (0.88, 0.98) / 0.95 (0.84, 0.99) O: 0.87 (0.75, 0.95) / 0.89 (0.84, 0.93) P: 0.98 (0.94, 1.00) / 0.98 (0.83, 1.00) Q: 0.99 (0.95, 1.00) / 0.98 (0.87, 1.00)

Pooled LUS sensitivity (type of statistical analysis is not mentioned): 0.94 (IQR: 0.89, 0.97)

Pooled LUS specificity (type of statistical analysis is not mentioned): 0.94 (IQR: 0.86, 0.98)

The overall diagnostic accuracy of LUS was expressed as a summary AUC of 0.98 (IQR: 0.94–0.99), using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.

Heterogeneity (reasons): Not expressed in I2, the data were analysed with forest plots.

To determine the components most responsible for the high degree of heterogeneity found, the data were analysed with forest plots. A significant difference was found between the amount of specificity in the group in which the CXR was used as the reference standard and the group in which only the clinical diagnosis by the attending physician was considered to be the reference standard (non-overlapped confidence Intervals).

|

Study quality (ROB): assessed by the authors with the QUADAS-2 tool (L low risk; ? Uncertain risk; H high risk)

Pt selection/Index Test /Ref standard/Flow & timing

A: ? L ? L B: L L ? L C: H ? ? ? D: ? L ? ? E: L L ? L F: L L L ? G: L L ? ? H: ? L ? L I: L L ? L J: H H ? ? K: L L ? L L: L L ? L M: ? L ? ? N: L L L L O: L L ? ? P: L L L ? Q: ? L ? L

The retrospective selection of patients was judged to be at a high risk of bias. Four studies considered a convenience sample: authors felt uncertain about the risk of bias. A funnel plot showed that studies with a small sample size achieved a considerably better effect than studies with a wider sample size, in terms of a possible publication bias. Most studies used CXR as a reference standard. Authors considered these studies’ risk of bias to be uncertain. The clinical diagnosis of the attending physicians as the only reference standard was considered a potential source of bias. Some studies did not specify whether LUS was performed before or after other imaging techniques. Some studies considered LUS within a 24- up to 36-h period from the first patient evaluation. This wide range of time could be a source of bias. The level of experience of the sonographers in the considered studies was rather variable: it ranged from a 1-h training course up to 25 years of professional experience. In almost all the studies the sonographer was unaware of the results of the reference standard. There was no blindness at all in one study (K). This parameter was not reported in 5 studies (C, G, J, M, Q)

NB: Some mistakes / print errors in this article: - Caiulo 2013 is falsely reported as Caiulo 2012 in all tables and figures. - Sensitivity and specificity mentioned in table 1 of this article do not match the ones mentioned in results figures and test: calculation unclear. We copied the numbers that were stated in article figures and text and in agreement with our own calculations.

Article conclusion: LUS seemed to be a promising method to diagnose pneumonia in the pediatric population; however, the high heterogeneity found across the individual studies and the absence of a reliable reference standard make the pooled results questionable. More methodologically rigorous studies are needed. More stringent criteria are also required for the reference standard and the diagnostic definition of pneumonia through LUS. |

|

Pereda, 2015

(individual)Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis

Literature search up to July 2014

8 studies included: A: Reali, 2014 B: Liu, 2014 C: Esposito, 2014 D: Shah, 2013 E: Caiulo, 2013 F: Seif El Dien, 2013 G: Iuri, 2009 H: Copetti, 2008

Study design: All, A-H were prospective studies. In all but one (F) studies, LUS operators were blinded to outcomes of CR before LUS performance and Interpretation.

Setting: - Emergency department: D, G, H - Hospital ward: A, E - Pediatric intensive care unit: C - Neonatal intensive care unit: B, F

Country: - Italy: A, C, E, G, H - China: B - USA: D - Egypt: F

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Financial disclosure: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. Funding: Miguel Chavez and Catherine C Hooper-Miele were both supported by the Fogarty International Center (5R25TW009340), United States National Institutes of Health. William Checkley was supported by a Pathway to Independence Award (R00HL096955) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, United States National Institutes of Health. Conflicts of interest: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose. Unspecified for included studies. |

Inclusion criteria SR: - Children < 18 yrs with clinical suspicion (signs and symptoms) of pneumonia and/or confirmation with CR or chest CT scan. The evaluation of pneumonia was based on a combination of clinical data, laboratory results, and chest imaging by CR or chest CT scan.

Exclusion criteria SR: -Studies that enrolled adults (≥ 18 years)

8 studies included with total n = 765

Important patient characteristics:

Number of patients: A: 107 B: 80, C: 103 D: 191 E: 102 F: 75 (NB: table 1 in article wrongfully states 95) G: 28 H: 79

Age (mean ± SD): A: 4 ± 3 B: not mentioned C: 5.6 ± 4.6 D: 2.9 ± 6.2 E: 5 ± 3 F: 0.03 ± 0.02 G: 4.5 ± 4.9 H: 5.1 ± 5

Sex (%male): A: 57% B: 54 % C: 54% D: 55% E: 52% F: 48% G: 61% H: 47%

|

LUS

Diagnostic criteria: Consolidations: A, F-H Alveolar and interstitial pattern: B-E. |

Reference test: - Clinical diagnosis: A, B, E, F, H - CR: A-H - Blood results: A, B, F

Chest CT scan was not used as a gold standard in any of the studies; however, 3 studies used chest CT scan for clinical purposes: A, F, H

Prevalence (%) A: 76% B: 50% C: 47% D: 18% E: 87% F: 77% G: 86% H: 76%

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%) Not reported

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Not reported |

Endpoint of follow-up: N/A |

LUS sensitivity (95%CI) / specificity (95%CI) for pneumonia A: 93.8 (86.2-98) / 96.2 (80.4-99.9) B: 100 (91-100) / 100 (91.2-100) C: 97.9 (88.9-99.9) / 94.5 (84.9-98.9) D: 85.7 (69.7-95.2) / 88.5 (82.4-93) E: 98.9 (93.9-100) / 100 (75.3-100) F: 93.2 (84.7-97.7) / 100 (15.8-100) G: 91.7 (73-99) / 100 (39.8-100) H: 100 (94-100) / 100 (82.4-100)

Pooled LUS sensitivity (random effects model): 95.8 (93.5-97.4) Heterogeneity (I2 >20% was considered as indicative of significant variation): I2 = 65.5%, significant.

Pooled LUS specificity (random effects model): 93 (89.6-95.6) Heterogeneity (I2 >20% was considered as indicative of significant variation): I2 = 47.8%, significant.

The overall diagnostic accuracy of LUS was expressed as a summary AUC of 0.98 (95% CI: 0.96-1.00), using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.

Estimate of pooled measurements of diagnostic accuracy: Pooled sensitivity and specificity with the use of the Mantel-Haenszel method (=random effects model)

Subgroup sensitivity analyses were also conducted by reference standard, acute care setting, age of child, and level of expertise in sonography to determine the robustness of findings: - in all 8 studies (A-H), only using the CR results LUS had a sensitivity of 96% (94%–98%) and a specificity of 84% (80%–88%) - in the 6 studies A, C-E, G, H) that enrolled children excluding neonates, LUS had a sensitivity of 96% (93%–98%) and a specificity of 92% (88%–95%) - in the 2 studies (B, F) that were limited to only neonates, LUS had a sensitivity of 96% (90%–98.5%) and a specificity of 100% (92%–100%). - in the 3 studies (D, G, H) that were conducted in emergency departments LUS had a sensitivity of 94% (88%–98%) and specificity of 90% (85%–94%). - in the 5 studies (A-C, E, F) that were conducted in hospital settings other than in an emergency department, LUS had a sensitivity of 96% (94%–98%) and a specificity of 97% (93%–99%). - in the 4 studies (B, E-G) that reported having an experienced physician or radiologist perform LUS, LUS had a sensitivity of 97% (93%–99%) and a specificity of 99% (94%–100%). - in the 4 studies (A, C, D, H) that used emergency department physicians, general practitioners, residents, or health care professionals otherwise not specified, LUS had a pooled sensitivity of 95% (95% CI: 91%–97%) and a specificity of 91% (87%–95%). |

Study quality (ROB): assessed by the QUADAS-2 tool: (L low risk; ? Uncertain risk; H high risk)

Pt selection/Index Test /Ref standard/Flow & timing

A: L L L L B: H L L U C: H L L L D: L L L L E: L L L L F: H H L H G: L L L L H: L L L L

In subgroup analysis when the reference standard was limited to findings based on CR alone, the authors found that the sensitivity of LUS was similar to that when both clinical criteria and CR were used to define childhood pneumonia, but specificity decreased to 84%, likely reflecting that CR alone is inadequate for the diagnosis of pneumonia.

Relevant mentioned limitations: - most studies included did not have large numbers of children - the total number of studies was small - there was significant heterogeneity between studies. - contributing to heterogeneity: not all studies compared LUS results with a clinical diagnosis and, in some studies, the final diagnosis was based solely on CR findings without the influence of clinical data (C, D, G). Three studies used a nonstandard technique to perform LUS (B,F,G).

Article conclusion: Despite significant heterogeneity across studies, LUS performed well for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children. Although the sensitivity and specificity are best in the hands of expert users, our study provides evidence of good diagnostic accuracy even in the hands of nonexperts. |

|

Wang, 2019

(individual)Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis

Literature search up to December 2018

6 studies included: A: Copetti, 2008 B: Guerra, 2016 C: Ianniello, 2016 D:Boursiani, 2017 E: Yilmaz, 2017 F: Biagi, 2018

Study design: - 6 prospective with blinding: A, B, D-F - 1 retrospective: C

Setting: Emergency department

Country: - Italy: A-C, F - Greece: D - Turkey: E

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: No funding mentioned. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Unspecified for included studies. |

Inclusion criteria SR: - pediatric patients aged <18 years with clinically suspected pCAP in ED Setting - inclusion of both LU and CR in diagnostic work-up - expert pediatrician clinical diagnosis as gold standard for diagnosis of pCAP - sufficient data to calculate the true-positive (TP), false-positive (FP), true negative (TN) and false-negative (FN) values.

Exclusion criteria SR: Editorials, letters, comments, reviews, conference abstract, case reports and animal experimental studies.

6 studies included with total n = 701

Important patient characteristics:

Number of patients: A: 79 B: 222 C: 84 D: 69 E: 160 F: 87

Median age in years: A: 5.1 B: 4.9 C: 6.0 D: 4.5 E: 1.4 F: 0.5

Sex (% male): A: Stated as “not available” B: Stated as “not available” C: 52% D: 39% E: 55% F: 49% |

Lung Ultrasonography (LU)

LU diagnostic criteria for pCAP: Consolidation: All studies (A-F) B-line artifact: 3 studies (C-E)

Chest radiography (CR)

CR Diagnostic criteria for pCAP: not mentioned

|

Reference Standard: - Clinical: All studies (A-F) - Clinical ex-post diagnosis: the final diagnosis is established by external physicians not involved in the clinical case by using all available data: 2 studies (D, F) - CT: 2 studies (A, B)

The criteria for pCAP diagnosis were not clearly reported. CR was probably included as part of the diagnostic criteria for pCAP in addition to clinical presentation and clinical course.

Prevalence of pCAP: A: 76% B: 96% C: 73% D: 96% E: 93% F: 29%

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%) Not reported

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Not reported |

Endpoint of follow-up: N/A |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p < 0.05):

LU sensitivity (95%CI) / specificity (95%CI) for pCAP A: 1.00 (0.94-1.00) / 1.00 (0.82-1.00) B: 0.97 (0.93-0.99)/ 1.00 (0.63-1.00) C: 0.98 (0.91-1.00) / 1.00 (0.85-1.00) D: 0.94 (0.85-0.98) / 1.00 (0.29-1.00) E: 0.95 (0.91-0.98) / 0.45 (0.17-0.77) F: Not reported / 0.84 (0.72-0.92)

Pooled LU sensitivity (random effects model): 96.7% (95% CI, 94.9–98.0%) Heterogeneity (I2 >50% was considered as indicative of significant variation): I2 = 40.7%, not significant.

Pooled LU specificity (random effects model): 87.3% (95% CI, 80.2–92.6%) Heterogeneity (I2 >50% was considered as indicative of significant variation): I2 = 80.7%), significant. Significant threshold effect was not found for LU (P=0.397). (heterogeneity caused by the threshold effect; if there is a strong positive correlation in Spearman’s correlation coefficient between the logit of sensitivity and logit of 1-specialty, threshold effects were considered to exist)

The overall diagnostic accuracy of LU was expressed as a summary AUC of 0.99 (95% CI, 0.98–1.00), using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.

There was substantial heterogeneity among studies, as indicated by I2. Meta-regression analysis was performed to explore the potential sources of heterogeneity. It included study design (prospective vs. retrospective), sample size of patients (>100 vs. <100), reference standard (ex-post diagnosis vs. non-ex-post diagnosis), LU sonographer (pediatrician vs. radiologist) and LU criteria for pCAP [consolidation vs. consolidation + B-line artifact (BLA)]. Meta-regression analysis failed to provide evidence of heterogeneity related to the potential effects of all above five confounding covariates. Also, sensitivity analysis revealed that the pooled sensitivity, specificity and SROC showed little change compared with the previous results when excluding the 6 studies one by one. |

Study quality (ROB): QUADAS-2 tool: (L low risk; ? Uncertain risk; H high risk)

Pt selection/Index Test /Ref standard/Flow & timing

A: U L U L B: L L U L C: L L U U D: L L L L E: L L U L F: L L L L

The suboptimal quality of included studies could introduce a source of heterogeneity into the present meta-analysis.

Study limitations: - articles in languages other than English were not included. - considerable heterogeneity was present. - small number of studies included. - in addition to accuracy, the cost-effectiveness of LU and CR is another significant concern for diagnosing pCAP in emergency departments (having limited medical resource); this was beyond the aim of the study. - a major limitation is the question of the reference standard. Four/six studies probably included CR as part of the diagnostic criteria for pCAP in addition to clinical presentation and clinical course. This likely skews the analysis of CR results towards higher specificity, which may be the underlying cause for the significant threshold effect found for CR in the meta-analysis (P=0.000).

Errors in the SR article: LU sensitivity results of one study not in figure / not reported. Figure reports specificity results of all studies as sensitivity results.

Article conclusion: Our meta-analysis suggests that LU is an accurate tool in the diagnosis of pCAP in the ED setting with a superior sensitivity over CR. However, the specificity of LU is lower than that of CR, which may be attributable to the unspecific LU finding of sub-centimeter consolidation or the inclusion of CR as part of the diagnostic criteria for pCAP.

|

|

Tsou, 2021

|

Results not reported: All included studies can be found in other SRs Research question does not match our interests. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

*comparator test equals the C of the PICO; two or more index/ comparator tests may be compared; note that a comparator test is not the same as a reference test (golden standard)

Evidence table for diagnostic test accuracy studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics

|

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Çağlar, 2019 |

Type of study: Prospective with LUS operator blinded to clinical and CXR findings and CXR evaluator blinded to clinical and LUS findings.

Setting and country: Pediatric emergency department (ED) in Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: For the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article, the author(s) received no financial support and declared no potential conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: - patients < 18 years of age with suspicion of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)

Exclusion criteria: - Patients with chronic pulmonary disease (based on probability of scar tissue) - patients with external thoracic wall malformations and thoracic trauma that can preclude optimal evaluation, or congenital lung malformations - patients who did not undergo both CXR and LUS on admission were not included.

N = 91

Prevalence of CAP based on clinical and chest X-ray findings: 71 (78%)

The median (IQR) age of the patients was 3.0 (1.0–5.0) years

Sex: % M 59% of the subjects were boys

Other important characteristics: 11 (12.0%) patients with fever and respiratory distress were diagnosed to have bronchiolitis, while 10 patients (11.0%) were diagnosed to have asthma. Cough and fever were the most observed symptoms in all patients (84.6% and 73.6%, respectively). There was respiratory distress in 62.6% of patients.

|

Lung ultrasonography (LUS)

Diagnostic criteria for (different types of) CAP: - Patients with shred sign, air bronchogram, or hepatization were diagnosed with alveolar pneumonia. - Patients with B lines (>3 in intercostal region) were classified as having interstitial pneumonia. Pleural effusion was diagnosed if the patient had sinusoidal and quad signs.

LUS was performed by a pediatric emergency physician who had taken course on LUS theory and had at least 150 LUS practice on patients before the study.

|

Clinical

Diagnostic criteria for suspicion of CAP: fever (>38°C), signs of respiratory distress, or symptoms of pneumonia (cough, tachypnea, dyspnea, retractions, nasal flaring, grunting, wheezing, and pulse oximetry measurement <90%)

and then, when positive on clinical/suspicion of CAP,

Chest X-ray

The findings of CXR were classified as alveolar, interstitial, mixed pneumonia, or normal and the presence of pleural effusion was also noted.

|

Time between the index test and reference test: not reported.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%) = 0 => patients who did not undergo both CXR and LUS on admission were not included. LUS was performed on alle patients, CXR on all patients with clinical suspicion of CAP.

|

LUS sensitivity for CAP % (95% CI): 78.5 (67.1–87.4)

LUS specificity for CAP % (95% CI): 95.2 (76.1–99.8)

Shred sign, air bronchogram, and hepatization were significantly more frequent in patients with CAP (p < 0.01, p < 0.01, and p = 0.01, respectively). The most observed LUS finding was shred sign (in 50 of the 70 CAP+ cases; in 1 of the 21 CAP- cases)

There was a statistically significant concordance between LUS and CXR in both determination of lesion localization and characterization of the lesion. |

- CXR was part of their reference standard, together with clinical findings, hindering comparison between LUS and CXR. - CT was not part of their reference standard. - The study only examined sens/spec for CAP, not other lower respiratory tract infections. |

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of diagnostic studies

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?5

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?8

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Balk, 2018 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Unclear (QUADAS used but not reported) |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Najgrodzka, 2019 |

Yes |

Unclear |

No |

No |

No |

Unclear |

No |

Yes |

|

Orso, 2018 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Pereda, 2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Wang, 2019 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Xin, 2018 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Heuvelings, 2019 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Tsou, 2019 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate (in relation to the research question to be answered in the clinical guideline) and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to the research question (PICO) should be reported

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (preferably QUADAS-2; COSMIN checklist for measuring instruments) and taken into account in the evidence synthesis

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, diagnostic tests (strategy) to allow pooling? For pooled data: at least 5 studies available for pooling; assessment of statistical heterogeneity and, more importantly (see Note), assessment of the reasons for heterogeneity (if present)? Note: sensitivity and specificity depend on the situation in which the test is being used and the thresholds that have been set, and sensitivity and specificity are correlated; therefore, the use of heterogeneity statistics (p-values; I2) is problematic, and rather than testing whether heterogeneity is present, heterogeneity should be assessed by eye-balling (degree of overlap of confidence intervals in Forest plot), and the reasons for heterogeneity should be examined.

- There is no clear evidence for publication bias in diagnostic studies, and an ongoing discussion on which statistical method should be used. Tests to identify publication bias are likely to give false-positive results, among available tests, Deeks’ test is most valid. Irrespective of the use of statistical methods, you may score “Yes” if the authors discuss the potential risk of publication bias.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

|

Study reference |

Patient selection

|

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Çağlar, 2019 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Unclear

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Unclear

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

Judgments on risk of bias are dependent on the research question: some items are more likely to introduce bias than others, and may be given more weight in the final conclusion on the overall risk of bias per domain:

Patient selection:

- Consecutive or random sample has a low risk to introduce bias.

- A case control design is very likely to overestimate accuracy and thus introduce bias.

- Inappropriate exclusion is likely to introduce bias.

Index test:

- This item is similar to “blinding” in intervention studies. The potential for bias is related to the subjectivity of index test interpretation and the order of testing.

- Selecting the test threshold to optimise sensitivity and/or specificity may lead to overoptimistic estimates of test performance and introduce bias.

Reference standard:

- When the reference standard is not 100% sensitive and 100% specific, disagreements between the index test and reference standard may be incorrect, which increases the risk of bias.

- This item is similar to “blinding” in intervention studies. The potential for bias is related to the subjectivity of index test interpretation and the order of testing.

Flow and timing:

- If there is a delay or if treatment is started between index test and reference standard, misclassification may occur due to recovery or deterioration of the condition, which increases the risk of bias.

- If the results of the index test influence the decision on whether to perform the reference standard or which reference standard is used, estimated diagnostic accuracy may be biased.

- All patients who were recruited into the study should be included in the analysis, if not, the risk of bias is increased.

Judgement on applicability:

Patient selection: there may be concerns regarding applicability if patients included in the study differ from those targeted by the review question, in terms of severity of the target condition, demographic features, presence of differential diagnosis or co-morbidity, setting of the study and previous testing protocols.

Index test: if index tests methods differ from those specified in the review question there may be concerns regarding applicability.

Reference standard: the reference standard may be free of bias but the target condition that it defines may differ from the target condition specified in the review question.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Balk, 2018 |

RCT's reported in included systematic reviews. Risk of bias |

|

Basile, 2015 |

Wrong O |

|

Malla, 2020 |

Wrong P |

|

Caiulo, 2011 |

Wrong O |

|

Lovrenski, 2013 |

Wrong O |

|

Ahmad, 2019 |

Wrong study design |

|

Biagi, 2018 |

Included in Wang, 2019 |

|

Bloise, 2020 |

Wrong reference standard |

|

Claes, 2017 |

Included in Orso, 2018 |

|

Di Mauro, 2019 |

Wrong O |

|

Heuvelings, 2019 |

RCT's reported in included systematic reviews. Risk of bias |

|

Jones, 2016 |

Wrong O |

|

Lissaman, 2019 |

Wrong reference standard |

|

Najgrodzka, 2019 |

RCT's reported in included systematic reviews. Risk of bias |

|

Tsou, 2019 |

RCT's reported in included systematic reviews |

|

Xin, 2018 |

RCT's reported in included systematic reviews |

|

Ambroggio, 2016 |

Included in Orso, 2018 |

|

Saraya, 2017 |

Wrong reference standard |

|

Schot, 2018 |

Wrong I |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 13-03-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kinderen met koorts op de Spoedeisende Hulp.

Werkgroep

- Dr. R. (Rianne) Oostenbrink, kinderarts, werkzaam in het ErasmusMC te Rotterdam, NVK (voorzitter)

- Dr. E.P. (Emmeline) Buddingh, kinderarts- infectioloog/immunoloog, werkzaam in het LUMC te Leiden, NVK

- Drs. J. (Joël) Israëls, kinderarts/pulmonoloog, werkzaam in het LUMC te Leiden, NVK

- Dr. A.E. (Anna) Westra, algemeen kinderarts, werkzaam in het Flevoziekenhuis te Almere, NVK

- Drs. E.P.M. (Erika) van Elzakker, arts-microbioloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVMM

- Dr. M.R.A. (Matthijs) Welkers, arts-microbioloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVMM, vanaf 25-04-2022

- Dr. C.R.B. (Christian) Ramakers, laboratoriumspecialist Klinische Chemie, werkzaam in het ErasmusMC te Rotterdam, NVKC

- Dr. G. (Jorgos) Alexandridis, spoedeisende hulp-arts, werkzaam in het Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland te Rotterdam, NVSHA

- Drs. K.M.A. (Karlijn) Meys, kinderradioloog, werkzaam in het UMC Utrecht te Utrecht, NVvR

- Dr. E (Eefje) de Bont, Huisarts, NHG

- I.J.M. (Ingrid) Vonk, verpleegkundig specialist, werkzaam in het Maasstad ziekenhuis te Rotterdam, V&VN

Klankbordgroep

- R. (Rowy) Uitzinger, junior projectmanager en beleidsmedewerker, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis, tot 01-06-2022

- E. (Esen) Doganer, junior projectmanager en beleidsmedewerker, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis, vanaf 01-06-2022

- Dr. A. (Annelies) Riezebos-Brilman, arts-microbioloog, werkzaam in het UMC Utrecht te Utrecht, NVMM, tot 25-04-2022

Met ondersteuning van:

- Dr. J. (Janneke) Hoogervorst – Schilp, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. M. (Mattias) Göthlin, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. T. (Tim) Christen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- M. (Miriam) van der Maten, MSc, junior medisch informatiespecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Tabel 1: Samenstelling van de werkgroep

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Werkgroep |

||||

|

* Voorzitter werkgroep Oostenbrink |

Kinderarts afd. algemene kindergeneeskunde Erasmusmc Rotterdam |

onbetaald: Member PEM-NL network |

Als wetenschapper betrokken bij de ontwikkeling en toepassing van de feverkidstool, predictie model voor kinderen met koorts, zonder financiele belangen.

|

Geen actie |

|

Buddingh |

Kinderarts infectioloog/ |

SWABID kinderen kerngroeplid (onbetaald) |

Principle investigator landelijke studie naar COVID-19 en MIS-C bij kinderen (COPP-studie, www.covidkids.nl)

|

Geen actie |

|

Israëls |

Kinderarts/pulmonoloog LUMC, Leiden |

APLS instructeur bij Stichting Spoedeisende hulp bij kinderen (onkostenvergoeding) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Vonk |

Maasstad Ziekenhuis |

Columnist Magazine Kinderverpleegkunde (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Alexandridis |

AIOS SEH te Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland |

APLS instructeur bij Stichting SHK (onkostenvergoeding) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Westra |

Algemeen Kinderarts Flevoziekenhuis / De Kinderkliniek Almere |

Lid NVK expertisegroep acute kindergeneeskunde, onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Ramakers |

Laboratoriumspecialist klinische chemie |

ISO 15189 vakdeskundige klinische chemie, Raad van Accreditatie, betaald. |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

van Elzakker |

Tot mei 2021: Arts-microbioloog HagaZiekenhuis en Juliana Kinderziekenhuis Den Haag, aandachtsgebied infecties bij kinderen Mei 2021-heden: arts-microbioloog AUMC, aandachtsgebied bacteriologie, infecties bij kinderen. |

Tot mei 2021 Auditor Raad voor Accreditatie (vakdeskundige) (betaald). Docent cursus antibiotica bij kinderen (betaald).

|

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

de Bont |

Zelfstandig Huisarts 0.6 FTE |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Welkers |

Arts-microbioloog, AmsterdamUMC 0,5 FTE) en GGD streeklaboratorium Amsterdam (0,5 FTE). 100% in dienst bij AmsterdamUMC en 0,5FTE gedetacheerd naar GGD streeklaboratorium. |

|

|

|

|

Klankbordgroep |

||||

|

Riezebos-Brilman |

Arts-microbioloog met aandachtsgebied virologie UMCU |

Voorzitter Richtlijn behandeling influenza (NVMM) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Uitzinger |

Junior projectmanager en beleidsmedewerker |

geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Doganer |

Junior projectmanager en beleidsmedewerker |

geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis uit te nodigen voor de klankbordgroep en voor de knelpunteninventarisatie. Het verslag van de knelpunteninventarisatie is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Diagnostiek lagere luchtweginfectie |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor kinderen met koorts op de Spoedeisende Hulp. Tevens was er mogelijkheid om knelpunten aan te dragen via een schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie. Een overzicht van de binnengekomen reacties is opgenomen in de bijlagen.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Prognostisch onderzoek: studiedesign en hiërarchie

Bij het beoordelen van literatuur is er een hiërarchie in de kwaliteit van individuele studies. Bij voorkeur wordt de effectiviteit van een klinisch beslismodel geëvalueerd in een klinische trial. Helaas zijn deze studies zeer zeldzaam. Indien niet beschikbaar, hebben studies waarin voorspellingsmodellen worden ontwikkeld en gevalideerd in andere samples van de doelpopulatie (externe validatie) de voorkeur aangezien er meer vertrouwen is in de resultaten van deze studies in vergelijking met studies die niet extern gevalideerd zijn. De meeste samples geven de karakteristieken van de totale populatie niet volledig weer, wat resulteert in afwijkende associaties, die mogelijk gevolgen hebben voor conclusies die getrokken worden. Studies die voorspellingsmodellen intern valideren (bijvoorbeeld door middel van bootstrapping of kruisvalidatie) kunnen ook worden gebruikt om de onderzoeksvraag te beantwoorden, maar het verlagen van het bewijsniveau ligt voor de hand vanwege het risico op bias en/of indirectheid, aangezien het niet duidelijk is of modellen voldoende presteren bij doelpopulaties. Het vertrouwen in de resultaten van niet-gevalideerde voorspellingsmodellen is erg laag. Over het algemeen leidt dit tot geen GRADE of Zeer lage GRADE. Dit geldt ook voor associatiemodellen. De risicofactoren die uit dergelijke modellen worden geïdentificeerd, kunnen worden gebruikt om patiënten of ouders te informeren over de inschatting van het risico op ernstige bacteriëmie, bacteriële meningitis of urineweginfectie, maar ze zijn minder geschikt om te gebruiken bij klinische besluitvorming.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.