Optimale type lijn

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het optimale type lijn voor een centraal veneuze toegang bij volwassen patiënten?

Aanbeveling

Kies bij het plaatsen van een centraal veneuze katheter:

- bij kortdurend gebruik (tot twee weken) voor een PICC of een niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter zonder cuff;

- bij middellang gebruik (twee weken tot drie maanden) bij voorkeur voor een PICC;

- bij langdurig intermitterend gebruik (langer dan drie maanden) in overleg met de patiënt voor een PICC of een poortkatheter;

- bij langdurig dagelijks gebruik (langer dan drie maanden) voor een PICC of een getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter met cuff.

Voor patiënten met chronische nierschade stadium 4 en 5 (eGFR <30 mL/min) zijn aanvullende aanbevelingen opgenomen in de richtlijn ‘Zorg bij eindstadium nierfalen’ (Module Vaatpreservatie).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd naar het optimale type lijn voor een centraal veneuze toegang. Mortaliteit, complicaties (waaronder infecties, diep veneuze trombose, katheter-gerelateerde bloedbaaninfecties, longembolieën) en patiënttevredenheid werden gedefinieerd als cruciale uitkomstmaten. Het aantal katheter-gerelateerde ingrepen per jaar en kwaliteit van leven werden als belangrijke uitkomstmaat gedefinieerd. De module is opgebouwd uit vier verschillende PICO’s. Perifeer geplaatste centrale veneuze katheters (PICC) werden vergeleken met poortkatheters (PAC; PICO 1), getunnelde centraal veneuze katheters met cuff ( PICO 2) en niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheters zonder cuff (PICO 3). Tenslotte werden getunnelde centraal veneuze katheters met niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheters vergeleken (PICO 4).

Er werden vijf studies geïncludeerd die een PICC vergeleken met een poortkatheter bij patiënten die gedurende drie tot twaalf maanden chemotherapie kregen. Er was een klinisch relevant verschil in het optreden van complicaties (alle complicaties samen) in het voordeel van poortkatheters. Ten aanzien van specifieke complicaties was er minder kans op een diep veneuze trombose, maar meer kans op een infectie (inclusief katheter-gerelateerde bloedbaaninfectie) en een longembolie bij een poortkatheter. Eén studie rapporteerde een hogere mortaliteit bij patiënten met een poortkatheter dan bij patiënten met een PICC. De belangrijke uitkomstmaat ‘katheter-gerelateerde ingrepen per jaar’ werd niet gerapporteerd. De bewijskracht voor de uitkomsten in het voordeel van PICCs is zeer laag, wat betekent dat de gevonden klinisch relevante verschillen voorzichtig geïnterpreteerd moeten worden. De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaten in het voordeel van poortkatheters is laag. De voornaamste reden voor de lage en zeer lage bewijskracht is het gebrek aan blindering van patiënten en de kleine aantallen patiënten in de geïncludeerde studies. We concluderen dat een poortkatheter mogelijk resulteert in minder complicaties en diepe veneuze trombose in vergelijking met een PICC.

Voor de vergelijking van een PICC met een getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter met cuff werd één studie geïncludeerd met patiënten die gedurende drie tot twaalf maanden chemotherapie kregen. Er was geen klinisch relevant verschil in het optreden van complicaties (alle complicaties samen) tussen de twee soorten vaattoegangen. Ten aanzien van specifieke complicaties was er meer kans op infectie (inclusief katheter-gerelateerde bloedbaaninfectie) en minder kans op diep veneuze trombose bij getunnelde centraal veneuze katheters. De bewijskracht voor deze uitkomsten varieerde echter van laag tot zeer laag. De cruciale uitkomstmaat mortaliteit en de belangrijke uitkomstmaat ‘katheter-gerelateerde ingrepen per jaar’ werden niet gerapporteerd. We concluderen dat er met het literatuuronderzoek geen belangrijke verschillen werden gevonden tussen getunnelde centraal veneuze katheters en PICCs.

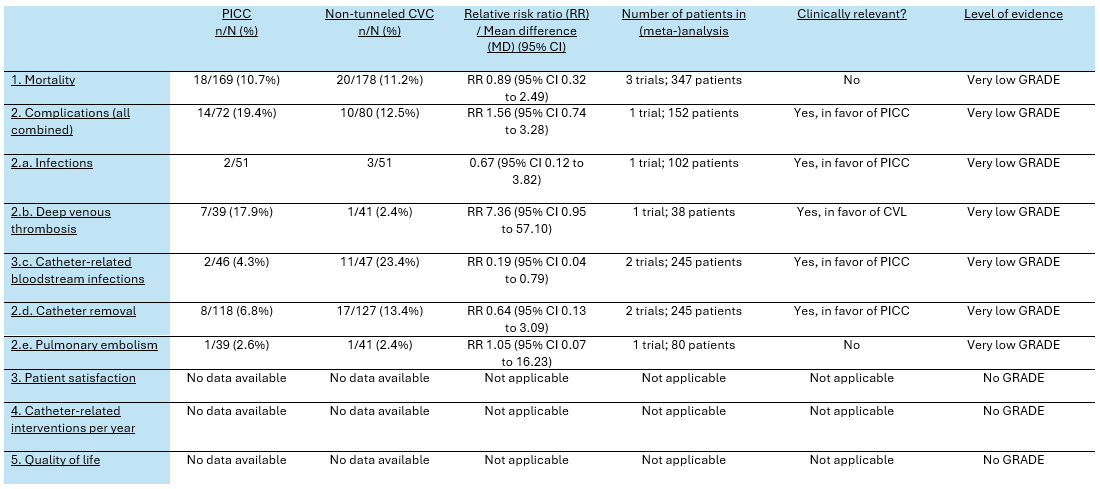

Er werden vier studies geïncludeerd die een PICC vergeleken met een niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter zonder cuff bij diverse patiëntengroepen die overwegend kortdurend een centraal veneuze toegang nodig hadden. De bewijskracht voor alle uitkomstmaten was zeer laag. De klinisch relevante verschillen die werden gevonden voor het optreden van complicaties (alle complicaties samen, diep veneuze trombose en katheter-gerelateerde bloedbaaninfecties) en mortaliteit moeten daarom voorzichtig worden geïnterpreteerd. De belangrijke uitkomstmaat ‘katheter-gerelateerde ingrepen per jaar’ werd niet gerapporteerd. We concluderen dat er met het literatuuronderzoek geen belangrijke verschillen werden gevonden tussen niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheters en PICCs.

Voor de vergelijking tussen getunnelde en niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheters werden vijf studies geïncludeerd. In geen van deze studies werd een getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter met cuff vergeleken met een niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter zonder cuff. De studies werden in diverse situaties uitgevoerd: twee studies vonden plaats op de intensive care unit bij patiënten die een centraal veneuze katheter in v. jugularis of in v. femoralis kregen met een gemiddelde gebruiksduur van een week, twee studies werden uitgevoerd bij patiënten die een PICC in de arm kregen voor chemotherapie met een gemiddelde gebruiksduur van twee tot drie maanden, en één studie werd uitgevoerd bij patiënten die een centraal veneuze katheter in v. subclavia kregen voor chemotherapie met een gemiddelde gebruiksduur van vier maanden. In deze gerandomiseerde studies hadden patiënten met getunnelde centraal veneuze katheters mogelijk minder infecties dan patiënten met niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheters. De bewijskracht voor dit voordeel van getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter is echter zeer laag, omdat er weinig katheter-gerelateerde infecties optraden waardoor de effectgrootte niet precies kon worden vastgesteld en omdat er een grote klinische heterogeniteit was tussen de studies.

In meerdere studies werd de cruciale uitkomstmaat patiënttevredenheid en de belangrijke uitkomstmaat kwaliteit van leven beschreven. Slechts één studie rapporteerde deze informatie op een manier die bruikbaar was voor de systematische literatuuranalyse. De informatie over deze uitkomstmaten wordt kwalitatief geïnterpreteerd in de sectie ‘Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten’.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Enkele onderzoeken die geïncludeerd zijn in de literatuuranalyse hebben de tevredenheid van patiënten met de vaattoegang gemeten (Clatot, 2020; Moss, 2021; Taxbro, 2019; Xiao 2021). Hoewel deze gegevens niet gebruikt konden worden voor een meta-analyse, geven deze onderzoeken wel inzicht in de waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten bij het maken van een keuze tussen een PICC en een poortkatheter. In één onderzoek zorgde het maken van een kort subcutaan tunneltraject niet tot meer discomfort tijdens het inbrengen van een PICC. In een ander onderzoek was zowel het inbrengen als het gebruik van een poortkatheter pijnlijker dan een PICC. In drie onderzoeken gaf een poortkatheter meer gemak bij persoonlijke hygiëne (douchen en baden) dan een PICC. In twee onderzoeken ervaarden patiënten een poortkatheter als meer comfortabel dan een PICC (bijvoorbeeld bij slapen, aankleden, intimiteit en sport). Als onderdeel van de CAVA studie werd een kwalitatief onderzoek uitgevoerd bij 42 patiënten in zes focus groepen (Ryan, 2019). Hoewel de deelnemers tevreden waren met elk van de vaattoegangen, hadden poortkatheters in de beleving van de patiënten praktische voordelen: ze zijn minder opvallend en verstorend en eenvoudiger te onderhouden, waardoor er meer vrijheid en minder indringing in persoonlijke relaties wordt ervaren. Deze voordelen hadden een belangrijke invloed op het psychologisch en emotioneel welzijn van de deelnemers. Metingen van algemene of ziekte-specifieke kwaliteit van leven in de onderzoeken van de literatuuranalyse (Clatot, 2020; Moss, 2021; Patel, 2013) lieten echter geen verschil zien tussen PICCs en poortkatheters. Waarschijnlijk werd de kwaliteit van leven in deze onderzoeken meer bepaald door de onderliggende ziekte en haar behandeling dan door het soort vaattoegang.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

In de CAVA studie werden de kosten van een PICC, centraal ingebrachte getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter en poortkatheter met elkaar vergeleken (Moss, 2021). Een poortkatheter was gemiddeld €1915,- duurder dan een PICC en een centraal ingebrachte getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter was gemiddeld €1786,- duurder dan een PICC. Voor kortdurend gebruik bij patiënten die parenterale voeding nodig hebben lijkt een niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter goedkoper te zijn dan een PICC (€15,- versus €21,- per dag; Cowl, 2010).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

In de MAGIC studie werden verschillende scenario’s waarin patiënten een intraveneuze toegang nodig hadden voorgelegd aan een panel van vijftien experts (Chopra, 2015). Wanneer medicatie moest worden toegediend waarvoor een centraal veneuze toegang nodig was, vond het panel dat een niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter gepast was voor kortdurend gebruik tot twee weken. Voor een langere periode werd de voorkeur gegeven aan een getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter (vanaf twee weken) of een poortkatheter (vanaf één maand). Een PICC werd beschouwd als een gepaste vaattoegang voor iedere gebruiksduur.

Door het tunnelen van een centraal veneuze katheter komt de katheter op een andere plaats uit de huid dan de plaats waar de katheter in de vene gaat. Hierdoor kan de operateur een huidpoort kiezen die minder gevoelig is voor infectie, die eenvoudiger te verzorgen is of die comfortabeler is voor de patiënt. Zo wordt een centraal veneuze katheter in v. jugularis doorgaans getunneld tot onder het sleutelbeen en wordt een getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter in v. femoralis naar de laterale zijde van het bovenbeen geleid. Een cuff is bedoeld om de katheter te fixeren en om infectie tegen te gaan. De cuff ligt bij voorkeur twee centimeter voorbij de huidpoort, zodat deze vanuit de huidpoort kan worden losgemaakt bij het verwijderen van de centraal veneuze katheter maar toch diep genoeg ligt om niet spontaan naar buiten te komen. Het tunnelen van een PICC kan zinvol zijn bij patiënten met smalle venen in de bovenarm. Door het maken van een subcutaan tunneltraject is het soms mogelijk om een grotere vene proximaal in de bovenarm aan te prikken en de katheter toch op een comfortabele plaats halverwege de bovenarm uit de huid te laten komen. Deze techniek leidt mogelijk tot minder veneuze trombose.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Voor kortdurend gebruik (minder dan twee weken; bijvoorbeeld voor postoperatieve parenterale voeding) is er keuze tussen een PICC of een niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter. Een niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter zonder cuff heeft in deze situatie de voorkeur boven een getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter met cuff, vanwege de lagere complexiteit van het plaatsen en verwijderen van deze katheters. Het wetenschappelijk bewijs geeft geen richting bij de keuze tussen PICC en niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter omdat het bewijs van zeer lage kwaliteit is en zich vooral richt op specifieke patiënten populaties (neurologische intensive care unit en hematologische maligniteit). Omdat de duur van het gebruik niet altijd goed is in te schatten en een niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter minder geschikt is voor gebruik buiten het ziekenhuis lijkt een PICC in veel gevallen de aangewezen keuze.

Voor middellang gebruik (twee weken tot drie maanden; bijvoorbeeld voor toediening van antibiotica) is er keuze tussen een PICC of een getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter met cuff. Een getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter met cuff heeft in deze situatie de voorkeur boven een niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter zonder cuff, vanwege de mogelijke reductie van het aantal infecties, de verminderde kans op dislocatie van de katheter wanneer de cuff (een manchet rond de katheter) na enkele weken is ingegroeid in het omringende weefsel, en de mogelijkheid om de uittredeplaats van de katheter zo te plaatsen dat deze het meest comfortabel is voor de patiënt. De CAVA studie suggereert dat er meer infecties optreden bij getunnelde centraal veneuze katheters dan bij PICCs, terwijl er vaker mechanische problemen zijn bij PICCs. Er is geen verschil in patiënttevredenheid en kwaliteit van leven bij gebruik van een PICC of een getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter. Het is goedkoper en in veel ziekenhuizen logistiek eenvoudiger om een PICC te plaatsen dan een getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter. We adviseren daarom om in deze situatie voor een PICC te kiezen.

Voor langdurig intermitterend gebruik (langer dan drie maanden; bijvoorbeeld voor toediening van chemotherapie) is er keuze tussen een PICC of een poortkatheter. De meta-analyse suggereert dat er minder complicaties optreden bij een poortkatheter dan bij een PICC. Dit verschil betreft met name het optreden van diep veneuze trombose. Het plaatsen, verzorgen, gebruiken en verwijderen van een PICC en een poortkatheter verschilt aanzienlijk. Dit maakt dat de voorkeuren van individuele patiënten een belangrijke rol kunnen spelen bij de keuze. Kwalitatief onderzoek laat zien dat poortkatheters voor veel patiënten praktische voordelen hebben.

Voor langdurig dagelijks gebruikt is er keuze tussen een PICC of een getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter met cuff; de argumenten die bij middellang gebruik werden genoemd zijn hier ook van toepassing. Wanneer de vaattoegang mogelijk levenslang nodig is (bijvoorbeeld bij chronische parenterale voeding), is een getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter met cuff echter de aangewezen keuze. Een diep veneuze trombose als gevolg van een PICC (ook wanneer deze geen symptomen geeft) kan het aanleggen van een arterioveneuze vaattoegang in de arm veel moeilijker maken. Zo’n vaattoegang kan nodig zijn wanneer er recidiverende infecties optreden van centraal veneuze katheters.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Wanneer een patiënt een centraal veneuze toegang nodig heeft, kan er een keuze worden gemaakt tussen vier verschillende soorten lijnen: een perifeer ingebrachte centrale katheter (PICC), een poortkatheter, een getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter met cuff en een niet-getunnelde centraal veneuze katheter zonder cuff. Elke soort lijn heeft voor- en nadelen bij het inbrengen, gebruiken en verwijderen van de lijn en heeft een eigen kans op complicaties (met name veneuze trombose en infectie). De verwachte gebruiksduur (kortdurend [tot twee weken], middellang [twee weken tot drie maanden], of langdurend [meer dan drie maanden]) en de gebruiksfrequentie (dagelijks of intermitterend) spelen mee bij de keuze voor een bepaald soort lijn. In deze module worden aanbevelingen gedaan over de keuze voor het soort lijn in verschillende klinische situaties.

Voor patiënten op de intensive care wordt verwezen naar de Richtlijn Centraal veneuze lijn van de NVIC. De aanleg van een vaattoegang voor hemodialyse valt buiten de afbakening van deze richtlijn en wordt beschreven in de richtlijn ‘Vaattoegang voor hemodialyse’.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

PICO 1. Peripherally inserted central (venous) catheters (PICC) versus Port catheter (PAC)

1. Mortality (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

A peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter may reduce overall mortality when compared with a port catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source: Taxbro, 2019 |

2. Complications (all combined) (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

A port catheter may reduce the number of complications (all combined) when compared with a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Sources: Moss, 2021; Patel, 2013; Taxbro, 2019; Clemons, 2020 |

2a. Infections

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter on infections when compared with a port catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Sources: Clatot, 2020; Clemons, 2020; Moss, 2021; Patel, 2013; Taxbro, 2019 |

2b. Deep venous thrombosis

|

Low GRADE |

A port catheter may reduce the number of deep venous thromboses when compared with a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Sources: Clatot, 2020; Clemons, 2020; Moss, 2021; Patel, 2013; Taxbro, 2019 |

2c. Catheter-related bloodstream infections

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter on catheter-related bloodstream infections when compared with a port catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Sources: Moss, 2021; Taxbro, 2019 |

2d. Catheter removal

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter on catheter removals when compared with a port catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Sources: Clatot, 2020; Clemons, 2020 |

2e. Pulmonary embolism

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter on pulmonary embolism when compared with a port catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Sources: Clemons, 2020; Moss, 2021 |

3. Patient satisfaction (critical)

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of relevant literature, it was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome patient satisfaction for treatment with a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter versus a port catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source(s): - |

4. Catheter-related interventions per year (important)

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of relevant literature, it was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome catheter-related interventions per year for treatment with a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter versus a port catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source(s): - |

5. Quality of life (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter on quality of life when compared with a port catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source: Moss, 2021 |

PICO 2. Peripherally inserted central (venous) catheters (PICC) versus tunneled venous catheter (CVC)

1. Mortality (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

Due to a lack of relevant literature, it was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome mortality for treatment with a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter versus a tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source(s): - |

2. Complications (all combined) (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter on complications (all combined) when compared with a tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source: Moss, 2021 |

2a. Infections

|

Low GRADE |

A peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter may reduce infections when compared with a tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source: Moss, 2021 |

2b. Deep venous thrombosis

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter on deep venous thrombosis when compared with a tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source: Moss, 2021 |

2c. Catheter-related bloodstream infections

|

Low GRADE |

A peripherally central (venous) catheter may reduce catheter-related bloodstream infections when compared with a tunneled venous catheter in adult patients given central venous access.

Source: Moss, 2021 |

2d. Catheter removal

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of relevant literature, it was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome catheter removal for treatment with a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter versus a tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source(s): - |

2e. Pulmonary embolism

|

Very low GRADE |

Due to a lack of relevant literature, it was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome pulmonary embolism for treatment with a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter versus a tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source(s): - |

3. Patient satisfaction (critical)

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of relevant literature, it was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome patient satisfaction for treatment with a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter versus a tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source(s): - |

4. Catheter-related interventions per year (important)

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of relevant literature, it was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome catheter-related interventions per year for treatment with a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter versus a tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source(s): - |

5. Quality of life (important)

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of relevant literature, it was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome quality of life for treatment with a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter versus a tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source(s): - |

PICO 3. Peripherally inserted central (venous) catheters (PICC) versus non-tunneled CVC

1. Mortality (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter on mortality when compared with a non-tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Sources: Brandmeir, 2020; Picardi, 2019; Chopra, 2013; Cowl, 2000 |

2. Complications (all combined) (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter on complications (all combined) when compared with a non-tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access

Source: Brandmeir, 2020 |

2a. Infections

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter on infections when compared with a non-tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Sources: Chopra, 2013; Cowl, 2000 |

2b. Deep venous thrombosis

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter on deep venous thrombosis when compared with a non-tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source: Fletcher, 2016 |

2c. Catheter-related bloodstream infections

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter on catheter-related bloodstream infections when compared with a non-tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source: Picardi, 2019 |

2d. Catheter removal

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter on catheter removal when compared with a non-tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Sources: Brandmeir, 2020; Picardi, 2019 |

2e. Pulmonary embolism

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter on pulmonary embolism when compared with a non-tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source: Fletcher, 2016 |

3. Patient satisfaction (critical)

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of relevant literature, it was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome patient satisfaction for treatment with a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter versus a non-tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source(s): - |

4. Catheter-related interventions per year (important)

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of relevant literature, it was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome catheter-related interventions per year for treatment with a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter versus a non-tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source(s): - |

5. Quality of life (important)

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of relevant literature, it was not possible to draw a conclusion with regards to the outcome quality of life for treatment with a peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter versus a non-tunneled venous catheter in adult patients with a central venous access.

Source(s): - |

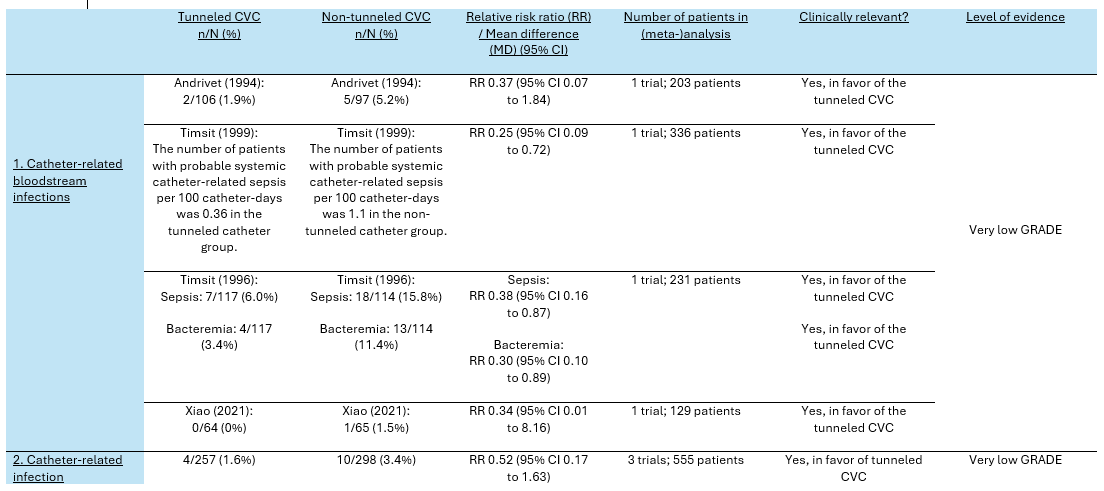

PICO 4. Tunneled CVC versus non-tunneled CVC

1. Catheter-related bloodstream infection (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of tunneled catheterization on catheter-related bloodstream infections when compared with non-tunneled catheterization in adult patients given central venous access.

Sources: Andrivet, 1994; Timsit, 1996; Timsit, 1999; Xiao, 2021 |

2. Catheter-related infection (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of tunneled catheterization on catheter-related infections when compared with non-tunneled catheterization in adult patients given central venous access.

Sources: Andrivet, 1994); Dai, 2020; Xiao, 2021 |

Samenvatting literatuur

PICO 1. PICC versus PAC

Systematic review(s)

-

Randomized controlled trial(s)

The randomized controlled phase II trial of Clatot (2020) aimed to compare the safety between peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC) with implanted port catheters (PAC) in patients with early breast cancer who were eligible for adjuvant chemotherapy administration. Catheters were used intermittently for nine months. In total, 256 participants were included and randomly allocated to either a PICC (n=128) or PAC (n=128). The median (IQR) age of the study population was 56.0 (30.0 to 74.0) years. The PICCs were removed on the day of the last chemotherapy administration, whereas PACs were removed four weeks after the last chemotherapy administration and before the start of radiation therapy. Outcomes were measured on the first day of each cycle of chemotherapy and at three weeks and six months after the last chemotherapy administration. None of the participants in the study were lost to follow-up. The reported outcomes in Clatot (2020) were complications (deep vein thrombosis (diagnosis based on clinical suspicion), infections, catheter removal), and quality of life.

The randomized controlled trial of Clemons (2020) aimed to compare PICCs versus PACs in patients receiving trastuzumab-based chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. Catheters were used intermittently for one year. In total, 56 participants were included and randomly allocated to either a PICC (n=29) or PAC (n=27). The median (IQR) age of the study population was 53.0 (32.0 to 84.0) years. The length of follow-up was not reported. No patients were lost to follow-up. The reported outcomes in Clemons (2020) were complications (deep venous thrombosis, infections, catheter removal).

The randomized controlled trial of Moss (2021) aimed to compare the safety of PICCs and PACs in patients who were expected to receive systemic anticancer treatment via a central vein. Catheters were used intermittently for more than 3 months. In total, 1061 participants were included. Of these, 346 participants were randomized to PICC (n=199) versus PAC (n=147). The mean age in each group was 61.0 years. Outcomes were measured after device removal, withdrawal or one year follow-up. All patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. The reported outcomes in Moss (2021) were complications (such as deep venous thrombosis, infections, pulmonary embolism, catheter-related bloodstream infections, catheter removal).

The randomized controlled trial of Patel (2013) aimed to compare the safety of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC) with port catheters (PAC) in the delivery of chemotherapy in patients with non-hematological malignancies. In total, 70 participants were included and randomly allocated to either a PICC (n=36) or PAC (n=34). The median (IQR) age of the included participants in the PICC group was 59 (29 to 84) years compared to 60.0 (34.0 to 78.0) years in the PAC group. Outcomes were measured every three weeks until central venous catheter removal or six months, whichever was sooner. None of the participants in the study were lost to follow-up. The reported outcomes in Patel (2013) were complications (such as deep vein thrombosis (diagnosed based on clinical suspicion), infections).

The randomized controlled trial of Taxbro (2019) aimed to investigate the safety of PICCs and PACs in non-hematological cancer patients. In total, 399 participants were included and randomly allocated to either a PICC (n=201) or PAC (n=198). The median (IQR) age of the included participants in the PICC group was 66 (19 to 84) years compared to 65.0 (30.0 to 89.0) years in the PAC group. Outcomes were measured after one, three, six and twelve months. None of the participants in the study were lost to follow-up. The reported outcomes in Taxbro (2019) were complications (deep venous thrombosis (diagnosis based on clinical suspicion)).

PICO 2. PICC versus tunneled CVC

Systematic review(s)

-

Randomized controlled trial(s)

The randomized controlled trial of Moss (2021) aimed to compare the safety of PICCs and CVC in patients who were expected to receive intermittent systemic anticancer treatment via a central vein for at least three months. In total, 424 participants were randomized to PICC versus a tunneled central venous catheter. The mean age between the group ranged from 61.0 to 62.0 years. Outcomes were measured after device removal, withdrawal or one year follow-up. All patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. The reported outcomes in Moss (2021) were complications (such as deep venous thrombosis, infections, pulmonary embolism, catheter-related bloodstream infections, and catheter removal).

PICO 3. PICC versus non-tunneled CVC

Systematic review(s)

The systematic review of Chopra (2013) aimed to compare the safety between peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC) with non-tunneled central venous catheters in patients receiving parental nutrition. Chopra (2013) searched the electronic databases of Medline, Cinahl, Scopus, Embase, and Cochrane Central registry up to the 1st of February 2013. Studies were included if they involved participants eighteen years of age or older and when they systematically compared the frequency of central line–associated bloodstream infection between PICCs and non-tunneled CVCs. Studies that involved neonates or children, compared infection rates associated with PICCs to those associated with devices that were not CVCs, and case reports, case-control studies, editorials, reviews or studies that did not report central-line associated bloodstream infections were excluded. In total, Chopra (2013) included 23 studies. Of these, only one study matched our PICO and was therefore included in the analysis of the literature of this guideline (Cowl, 2000). All other studies were excluded because of their observational study design. Cowl (2000) included 102 hospitalized patients and compared a peripherally inserted central catheter with a non-tunneled catheter (placed in the subclavian vein) to deliver parenteral nutrition for a median of ten days. The reported outcomes in the study of Cowl (2000) were mortality, and complications (such as infections).

Randomized controlled trial(s)

The randomized controlled trial of Brandmeir (2020) aimed to compare the safety of PICCs and non-tunneled central venous catheters in patients admitted to an intensive care unit who required central venous access. In total, 152 participants were included and randomly allocated to either a PICC (n=72) or non-tunneled CVC (n=80). The mean (SD) age of the study population was 61.4 (15.9) years. The length of follow-up was not reported. Catheters were used continuously for one week and placed in the jugular or subclavian vein. None of the participants in the study were lost to follow-up. The reported outcomes in Brandmeir (2020) were deep vein thrombosis (diagnosis based on clinical suspicion), catheter-related bloodstream infections, mechanical failure, catheter removal, length of stay on the intensive care unit, and mortality.

The randomized controlled trial of Picardi (2019) aimed to compare the safety of PICCs versus non-tunneled central venous catheters in patients with acute myeloid leukemia who underwent intensive chemotherapy for hematologic remission induction. In total, 93 participants were included and randomly allocated to either a PICC (n=46) or a non-tunneled CVC (n=47). The median (IQR) age of the study population was 53.8 (18 to 80) years. Outcomes were measured after 30 days. None of the participants in the study were lost to follow-up. Catheters were used continuously for more than one month and were placed in the jugular or subclavian vein. The reported outcomes in Picardi (2019) were mortality and complications (deep venous thrombosis (diagnosis based on ultrasound screening), catheter-related bloodstream infections, catheter removal).

The randomized controlled trial of Fletcher (2016) aimed to compare the safety of PICCs and non-tunneled central venous catheters in critically ill neurologic patients. In total, 80 participants were included and randomly allocated to either a PICC (n=39 or non-tunneled CVC (n=41). The mean (SD) age of the study population was 60.0 (14.0) years. Outcomes were measured after 15 days or death. None of the participants in the study were lost to follow-up. Catheters were used continuously for two weeks and were placed in the jugular or subclavian vein. The reported outcomes in Fletcher (2016) were mortality and complications (venous thrombosis (diagnosis based on ultrasound screening of deep and superficial veins), catheter-related bloodstream infections, pulmonary embolism, catheter removal).

PICO 4. Tunneled CVC versus non-tunneled CVC

Systematic review(s)

-

Randomized controlled trial(s)

The randomized controlled trial of Andrivet (1994) investigated the efficacy of subcutaneous tunneled catheters in comparison with non-tunneled catheters in immunocompromised patients with malignancies who needed a long-term central venous access. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the treatment groups. For patients allocated in the tunneled catheters group (n=107), tunneling (for seven or eight centimeter) was performed each time with the same dilator and introducer by using the Powell-Tuck technique. In de non-tunneled catheter group (n=105), polyurethane catheters were inserted instead of silicone catheters. This type of catheter includes an integrated hub that cannot be tunneled easily. The mean (standard error) life span of the catheters used in the entire study population was 116 (6.5) days, during which 3.7 (0.2) antineoplastic sources per patient were administered. Catheters were used for 45 (2.6) days in inpatients and for 71 (5.6) days in outpatients. Fifty-one catheters were used in subjects who were inpatients only and remained in place for 40.5 (7.5) days in the tunneled group and 45.0 (6.4) days in the non-tunneled group. The central venous catheters were inserted in the subclavian vein. The tunneled catheters were non-cuffed. Five patients in the tunneled catheter group and one patient in the non-tunneled catheter group were lost the follow-up. The reported outcome was incidence of catheter-related infection.

The randomized controlled trial of Dai (2020) investigated the efficacy of tunneled and non-tunneled peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) placement under B-mode ultrasound for oncological patients. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the treatment groups. The tunneled group (n=87) received tunneled PICC placement with B-mode ultrasound and modified Seldinger technique for which the puncture site was three centimeter above the catheter exit site. The non-tunneled group (n=87) receive routine non-tunneled PICC placement with B-mode ultrasound guidance and modified Seldinger technique for which the puncture site and catheter exit site were at the same position. The PICCs were inserted in the basilic or brachial vein. The tunneled catheters were non-cuffed. The study did not report how long the catheters remained in place. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The reported outcome was catheter-related infection.

The randomized controlled trial of Timsit (1999) investigated the effect of tunneled or non-tunneled femoral catheters in critically ill patients on the intensive care unit. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the treatment groups. The tunneled catheter group (n=168) received polyurethane monolumen or bilumen tunneled catheters, inserted by using the Seldinger method. The non-tunneled catheter group (n=168) received the same polyurethane catheters as used in the tunneled catheter group with the same external diameter. The central venous catheters were inserted in the femoral vein. The tunneled catheters were non-cuffed. The mean (standard deviation) duration of catheter maintenance in the tunneled-catheter group was 8.2 (4.7) days, compared to 7.6 (4.5) days in the non-tunneled catheter group. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The reported outcomes were incidence of catheter-related bloodstream infection and catheter-related infection.

The randomized controlled trial of Timsit (1996) investigated the effect of tunneled or non-tunneled catheters in critically ill patients on the intensive care unit. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the treatment groups. The tunneled catheter group (n=117) received polyurethane monolumen or bilumen tunneled catheters, inserted by using the Seldinger method. The non-tunneled catheter group (n=114) received the same polyurethane catheters used in the tunneled catheter group with the same internal and external diameter. The central venous catheters were inserted in the jugular vein. The tunneled catheters were non-cuffed. The mean (standard deviation) duration of catheter placement was about the same in both groups (8.48 (4.8) days in the tunneled group and 8.19 (4.8) days in the non-tunneled group). None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The reported outcome was incidence of catheter-related infection.

The randomized controlled trial of Xiao (2021) investigated the effect of subcutaneous tunneling versus the normal technique in patients undergoing chemotherapy with peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC). Participants were randomly assigned to one of the treatment groups. The subcutaneous tunneling group (n=64) received subcutaneous tunneling technique combined with the normal PICC placement technique for which the puncture site was located five centimeter above the catheter exit site on the patient’s upper arm. Participants who were allocated to the control group (n=65) received non-tunneled PICC catheterization by using the normal PICC placement technique under B-mode ultrasound guidance combined with the modified Seldinger technique. The PICCs were inserted in the basilic or brachial vein. The tunneled catheters were non-cuffed. The median (interquartile range) duration of catheter placement in the subcutaneous tunneling group was 88 (8 to 191) days, compared to 72 (15 to 192) days in the non-tunneled group. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. The reported outcomes were incidence of catheter-related bloodstream infection and catheter-related infection.

Results

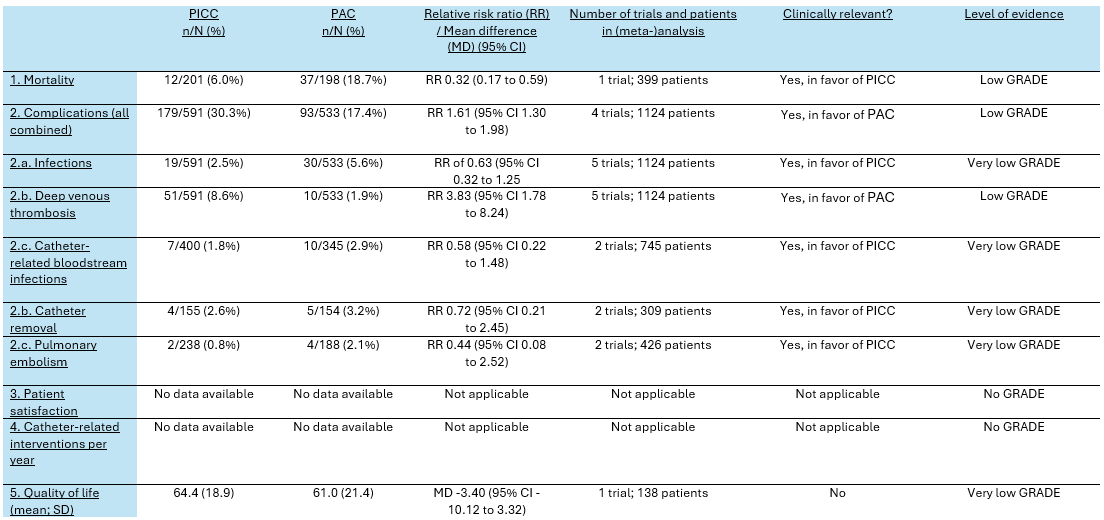

PICO 1. Peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter (PICC) versus Port catheter (PAC)

1. Mortality rates (critical)

Overall mortality was reported in one trial (Taxbro, 2019). The mortality rate in the PICC group was 12/201 (6.0%), compared to 37/198 (18.7%) in the PAC group. This resulted in a RR of 0.32 (95% CI 0.17 to 0.59), in favor of the PICC group. This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

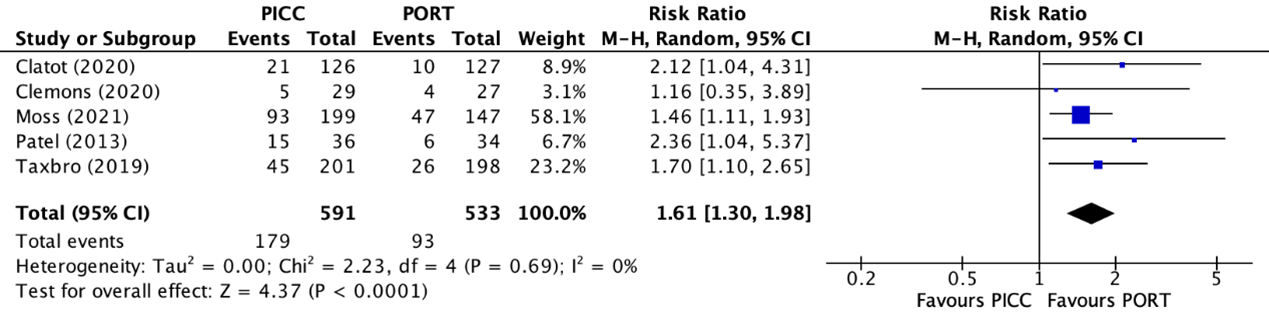

2. Complications (all combined) (critical)

Five trials reported the combined number of complications (Clatot, 2020; Clemons, 2020; Moss, 2021; Patel, 2013; Taxbro, 2019). The total number of combined complications in the PICC group was 179/591 (30.3%), compared to 93/533 (17.4%) in the PAC group. This resulted in a relative risk ratio (RR) of 1.61 (95% CI 1.30 to 1.98), in favor of the PAC group (figure 1). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 1. Forest plot showing the comparison between PICC and PAC for all combined complications

Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity

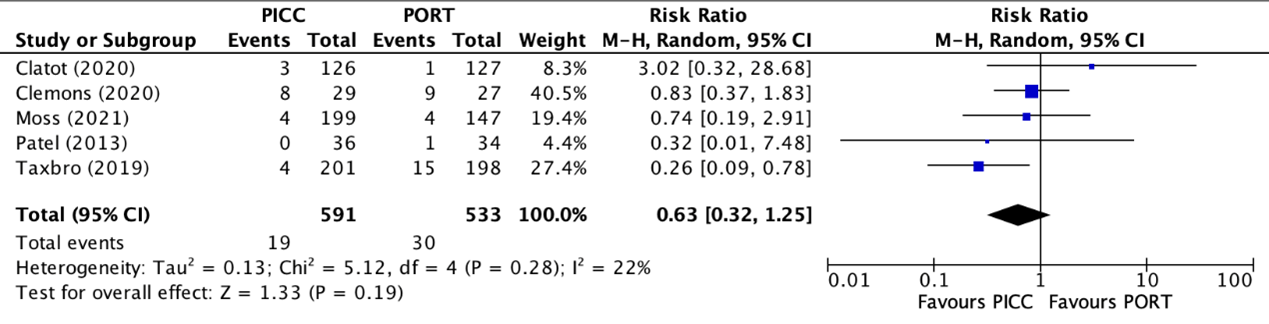

2a. Infection rate

Infection rates were reported in five trials (Clatot, 2020; Clemons, 2020; Moss, 2021; Patel, 2013; Taxbro, 2019). Clatot (2020), Moss (2021), and Taxbro (2019) defined infections as pocket/exit site infections. Clemons (2020) and Patel (2013) did not specify the definition of infections in their studies. The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled infection rate in the PICC group was 19/591 (2.5%), compared to 30/533 (5.6%) in the PAC group. This resulted in a pooled RR of 0.63 (95% CI 0.32 to 1.25), in favor of the PICC group (figure 2). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the comparison between PICC and PAC for infections

Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity

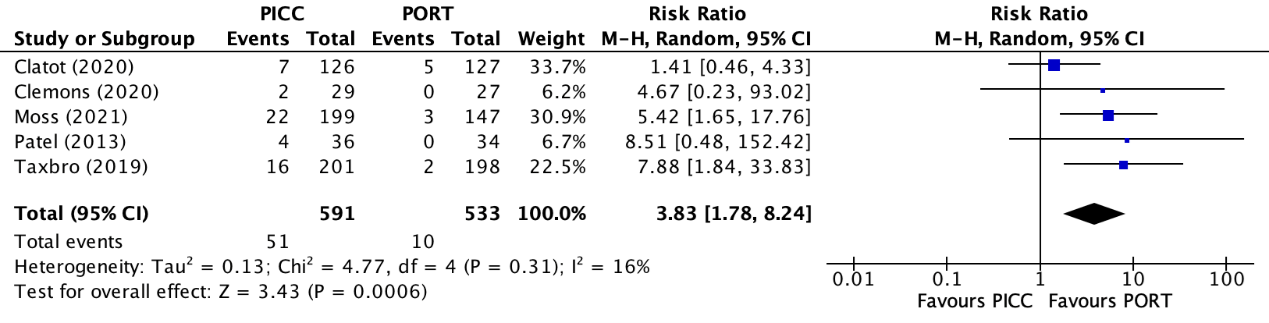

2b. Deep venous thrombosis

Deep venous thrombosis was reported in five trials (Clatot, 2020; Clemons, 2020; Moss, 2021; Patel, 2013; Taxbro, 2019). Clatot (2020) reported deep venous thrombosis without local infection or septicaemia. Patel (2013) reported the combined number of patients wiFCIth deep venous thrombosis and/or line occlusion, which must be considered when interpreting the results. The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of patients with deep venous thrombosis in the PICC group was 51/591 (8.6%), compared to 10/533 (1.9%) in the PAC group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 3.83 (95% CI 1.78 to 8.24), in favor of the PAC group (figure 3). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the comparison between PICC and PAC for deep venous thrombosis

Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity

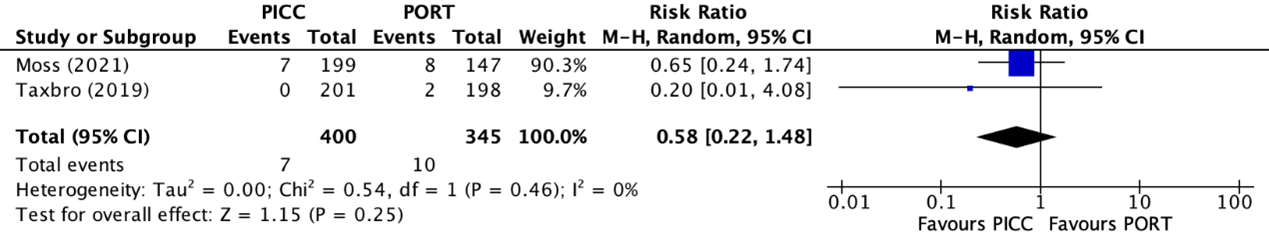

2c. Catheter-related bloodstream infections rates

The catheter-related bloodstream infection rates were reported in two trials (Moss, 2021; Taxbro, 2019). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled catheter-related bloodstream infection rate in the PICC group was 7/400 (1.8%), compared to 10/345 (2.9%) in the PAC group. This resulted in a pooled RR of 0.58 (95% CI 0.22 to 1.48), in favor of the PICC group (figure 4). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 4. Forest plot showing the comparison between PICC and PAC for catheter-related bloodstream infections

Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity

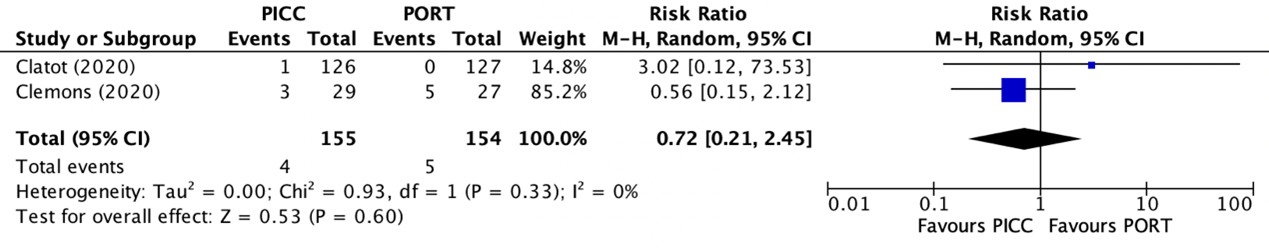

2d. Catheter removals

Catheter removals were reported in two trials (Clatot, 2020; Clemons, 2020). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of catheter removals in the PICC group was 4/155 (2.6%), compared to 5/154 (3.2%) in the PAC group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.72 (95% CI 0.21 to 2.45), in favor of the PICC group (figure 5). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 5. Forest plot showing the comparison between PICC and PAC for catheter removals

Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity

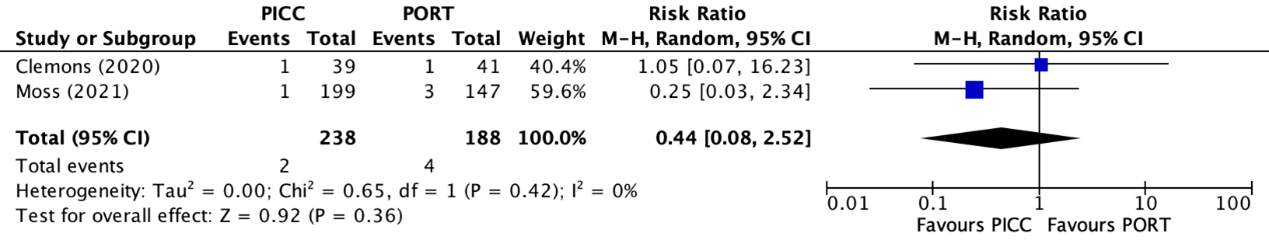

2e. Pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolisms were reported in two trials (Clemons, 2020; Moss, 2021). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of pulmonary embolisms in the PICC group was 2/238 (0.8%), compared to 4/188 (2.1%) in the PAC group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.44 (95% CI 0.08 to 2.52), in favor of the PICC group (figure 6). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 6. Forest plot showing the comparison between PICC and PAC for pulmonary embolism

Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity

3. Patient satisfaction (critical)

None of the included studies reported information regarding patient satisfaction for treatment with a PICC or PAC.

4. Catheter-related interventions per year (important)

None of the included studies reported information regarding catheter-related interventions per year for treatment with a PICC or PAC.

5. Quality of life (important)

One trial reported quality of life (Clatot, 2020). Quality of life was measured with the QLQ-C30. The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a disease-specific measurement tool for use in patients with or cured of cancer that describes several aspects of quality of life on a zero (minimum) to 100 (maximum) numeric scale. A higher score indicates better quality of life.

The mean (SD) QLQ-C30 score in the PICC group (n=66) was 64.4 (18.9) points, compared to 61.0 (21.4) points in PAC group (n=72). This resulted in a mean difference of -3.40 (95% -10.12 CI to 3.32), in favor of the PICC group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

PICO 1. PICC versus PAC

1. Mortality (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome mortality was derived from a randomized controlled trial and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as low.

2. Complications (all combined) (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome complications (all combined) was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1) and the small number of events (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as low.

2a. Infections

The level of evidence regarding the outcome complications (all combined) was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1), the wide confidence interval crossing both boundaries of clinical relevance, and the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

2b. Deep venous thrombosis

The level of evidence regarding the outcome deep venous thrombosis was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1) and the small number of events (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as low.

2c. Catheter-related bloodstream infections

The level of evidence regarding the outcome catheter-related bloodstream infections was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1), the wide confidence interval crossing both boundaries of clinical relevance, and the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

2d. Catheter removal

The level of evidence regarding the outcome catheter removal was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1), the wide confidence interval crossing both boundaries of clinical relevance, and the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

2e. Pulmonary embolism

The level of evidence regarding the outcome pulmonary embolism was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1), the wide confidence interval crossing both boundaries of clinical relevance, and the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

3. Patient satisfaction (critical)

Because of a lack of data, it was not possible to grade the literature for the outcome patient satisfaction for treatment with PICC versus PAC.

4. Catheter-related interventions per year (important)

Because of a lack of data, it was not possible to grade the literature for the outcome catheter-related interventions per year for treatment with PICC versus PAC.

5. Quality of life (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome quality of life was derived from a randomized controlled trial and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the included study (risk of bias, -1), the wide confidence interval crossing the lower boundary of clinical relevance, and the small number of included patients (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

Table 1. Summary of findings PICO 1

PICO 2. PICC versus tunneled CVC

1. Mortality (critical)

None of the included studies reported information regarding mortality for treatment with a PICC or tunneled CVC.

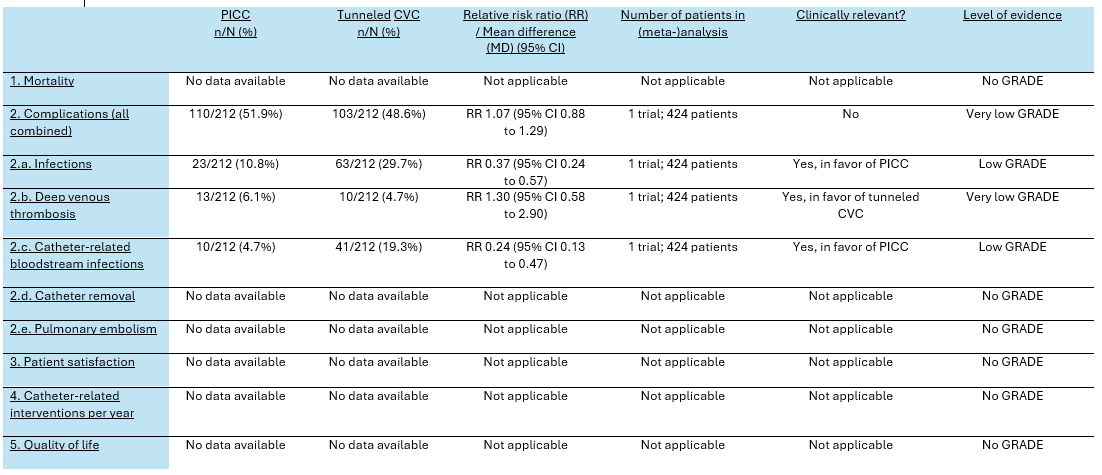

2. Complications (critical)

One trial reported the combined number of complications (Moss, 2021). The number of combined complications in the PICC group was 110/212 (51.9%), compared to 103/212 (48.6%) in the CVC group. This resulted in a RR of 1.07 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.29), in favor of the tunneled CVC group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

2a. Infections

Infections were reported in one trial (Moss, 2021). The number of infections in the PICC group was 23/212 (10.8%), compared to 63/212 (29.7%) in the tunneled CVC group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.37 (95% CI 0.24 to 0.57), in favor of the PICC group. This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

2b. Deep venous thrombosis

Deep venous thrombosis was reported in one trial (Moss, 2021). The number of patients with deep venous thrombosis in the PICC group was 13/212 (6.1%), compared to 10/212 (4.7%) in the tunneled CVC group. This resulted in a RR of 1.30 (95% CI 0.58 to 2.90), in favor of the tunneled CVC group. This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

2c. Catheter-related bloodstream infections

Catheter-related bloodstream infections were reported in one trial (Moss, 2021). The number of catheter-related bloodstream infections in the PICC group was 10/212 (4.7%), compared to 41/212 (19.3%) in the tunneled CVC group. This resulted in a RR of 0.24 (95% CI 0.13 to 0.47), in favor of the PICC group. This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

2d. Catheter removal

None of the included studies reported information regarding catheter removal for treatment with a PICC or tunneled CVC.

2e. Pulmonary embolism

None of the included studies reported information regarding pulmonary embolism for treatment with a PICC or tunneled CVC.

3. Patient satisfaction (critical)

None of the included studies reported information regarding patient satisfaction for treatment with a PICC or tunneled CVC.

4. Catheter-related interventions per year (important)

None of the included studies reported information regarding catheter-related interventions per year for treatment with a PICC or tunneled CVC.

5. Quality of life (important)

None of the included studies reported information regarding quality of life for treatment with a PICC or tunneled CVC.

Level of evidence of the literature

PICO 2. PICC versus tunneled CVC

1. Mortality (critical)

Because of a lack of data, it was not possible to grade the literature for the outcome mortality for treatment with PICC versus tunneled CVC.

2. Complications (all combined) (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome complications (all combined) was derived from a randomized controlled trial and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1), the wide confidence interval crossing the upper boundary of clinical relevance, and the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

2a. Infections

The level of evidence regarding the outcome infections was derived from a randomized controlled trial and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1) and the small number of events (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as low.

2b. Deep venous thrombosis

The level of evidence regarding the outcome deep venous thrombosis was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1), the wide confidence interval crossing both boundaries of clinical relevance, and the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

2c. Catheter-related bloodstream infections

The level of evidence regarding the outcome catheter-related bloodstream infections was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1) and the small number of events (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was considered as low.

2d. Catheter removal

Because of a lack of data, it was not possible to grade the literature for the outcome catheter removal for treatment with PICC versus tunneled CVC.

2e. Pulmonary embolism

Because of a lack of data, it was not possible to grade the literature for the outcome pulmonary embolism for treatment with PICC versus tunneled tunneled CVC.

3. Patient satisfaction (critical)

Because of a lack of data, it was not possible to grade the literature for the outcome patient satisfaction for treatment with PICC versus tunneled tunneled CVC.

4. Catheter-related interventions per year (important)

Because of a lack of data, it was not possible to grade the literature for the outcome catheter-related interventions per year for treatment with PICC versus tunneled CVC.

5. Quality of life (important)

Because of a lack of data, it was not possible to grade the literature for the outcome quality of life for treatment with PICC versus tunneled CVC.

Table 2. Summary of findings PICO 2

PICO 3. Peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter (PICC) versus non-tunneled central venous catheter

1. Mortality (critical)

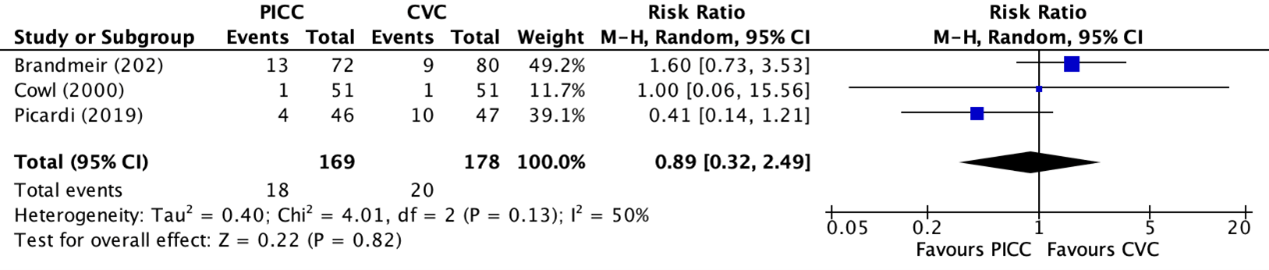

Mortality was reported in one trial, retrieved from the systematic review of Chopra (2013) (Cowl, 2000) and in two individual trials (Brandmeir, 2020; Picardi, 2019). Picardi (2019) reported the 30-day mortality. Brandmeir (2020) and Cowl (2000) did not specify the length of follow-up for mortality. The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of mortalities in the PICC group was 18/169 (10.7%), compared to 20/178 (11.2%) in the non-tunneled CVC group. This resulted in a RR of 0.89 (95% CI 0.32 to 2.49), in favor of the non-tunneled CVC group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 7. Forest plot showing the comparison between PICC and non-tunneled CVC for mortality

Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity

2. Complications (critical)

One trial reported the combined number of complications (Brandmeir, 2020). The number of combined complications in the PICC group was 14/72 (19.4%), compared to 10/80 (12.5%) in the non-tunneled CVC group. This resulted in a RR of 1.56 (95% CI 0.74 to 3.28), in favor of the non-tunneled CVC group. This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

2a. Infection rates

One trial, retrieved from the systematic review of Chopra (2013) reported the combined number of infections (Cowl, 2000). The number of infections in the PICC group was 2/51 (3.9%), compared to 3/51 (5.9%) in the non-tunneled CVC group. This resulted in a RR of 0.67 (95% CI 0.12 to 3.82), in favor of the PICC group. This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

2b. Deep venous thrombosis

Deep venous thrombosis was reported in one trial (Fletcher, 2016). The number of patients with deep venous thrombosis in the PICC group was 7/39 (17.9%), compared to 1/41 (2.4%) in the non-tunneled CVC group. This resulted in a RR of 7.36 (95% CI 0.95 to 57.10), in favor of the non-tunneled CVC group. This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

2c. Catheter-related bloodstream infections

Catheter-related bloodstream infections were reported in one trial (Picardi, 2019). The number of catheter-related bloodstream infections in the PICC group was 2/46 (4.3%), compared to 11/47 (23.4%) in the non-tunneled CVC group. This resulted in a RR of 0.19 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.79), in favor of the PICC group. This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

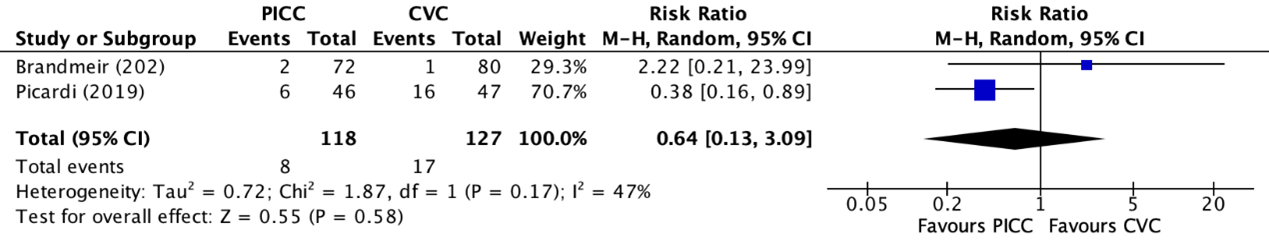

2d. Catheter removal

Catheter removal was reported in two trials (Brandmeir, 2020; Picardi, 2019). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The number of catheter removals in the PICC group was 8/118 (6.8%), compared to 17/127 (13.4%) in the non-tunneled CVC group. This resulted in a RR of 0.64 (95% CI 0.13 to 3.09), in favor of the PICC group (figure 10). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 8. Forest plot showing the comparison between PICC and non-tunneled CVC for catheter removal

Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity

2e. Pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolisms were reported in one trial (Fletcher, 2016). The number of pulmonary embolisms in the PICC group was 1/39 (2.6%), compared to 1/41 (2.4%) in the non-tunneled CVC group. This resulted in a RR of 1.05 (95% CI 0.07 to 16.23), in favor of the CVL group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

3. Patient satisfaction (critical)

None of the included studies reported information regarding patient satisfaction for treatment with a PICC or non-tunneled CVC.

4. Catheter-related interventions per year (important)

None of the included studies reported information regarding catheter-related interventions per year for treatment with a PICC or non-tunneled CVC.

5. Quality of life (important)

None of the included studies reported information regarding quality of life for treatment with a PICC or non-tunneled CVC.

Level of evidence of the literature

PICO 3: PICC versus non-tunneled CVC

1. Mortality (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome mortality was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of the wide confidence interval crossing the upper boundary of clinical relevance, the small number of events (imprecision, -2), and heterogeneity in the study results (inconsistency, -1). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

2. Complications (all combined) (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome complications (all combined) was derived from a randomized controlled trial and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1), the wide confidence interval crossing the upper boundary of clinical relevance, and the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

2a. Infections

The level of evidence regarding the outcome infections was derived from a randomized controlled trial and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of the lack of blinding in the included study (risk of bias, -1), the wide confidence interval crossing the lower and upper boundaries of clinical relevance, the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

2b. Deep venous thrombosis

The level of evidence regarding the outcome deep venous thrombosis was derived from a randomized controlled trial and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1), the wide confidence interval crossing the upper boundary of clinical relevance, and the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

2c. Catheter-related bloodstream infections

The level of evidence regarding the outcome catheter-related bloodstream infections was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1), the wide confidence interval crossing the lower boundary of clinical relevance, and the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

2d. Catheter removal

The level of evidence regarding the outcome catheter removal was derived from a randomized controlled trial and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1), the wide confidence interval crossing both boundaries of clinical relevance, and the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

2e. Pulmonary embolism

The level of evidence regarding the outcome pulmonary embolism was derived from a randomized controlled trial and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1), the wide confidence interval crossing the upper boundary of clinical relevance, and the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

3. Patient satisfaction (critical)

Because of a lack of data, it was not possible to grade the literature for the outcome patient satisfaction for treatment with PICC versus non-tunneled CVC.

4. Catheter-related interventions per year (important)

Because of a lack of data, it was not possible to grade the literature for the outcome catheter-related interventions per year for treatment with PICC versus non-tunneled CVC.

5. Quality of life (important)

Because of a lack of data, it was not possible to grade the literature for the outcome quality of life for treatment with PICC versus non-tunneled CVC.

Table 3. Summary of findings PICO 3

PICO 4. Tunneled CVC versus non-tunneled CVC

1. Catheter-related bloodstream infection

Catheter-related bloodstream infection was reported in four trials (Andrivet, 1994; Timsit; 1996; Timsit, 1999; Xiao, 2021). Catheter-related sepsis and catheter-related bacteremia were also categorized under catheter-related bloodstream infections. Andrivet reported the number of catheter-related bacteremia. Timsit (1999) reported the incidence of catheter-related bloodstream infections and the incidence of catheter-related sepsis per 100 catheter-days. Xiao (2021) reported the absolute number of catheter-related bloodstream infections between tunneled- and non-tunneled catheters.

Andrivet (1994) reported the incidence of catheter-related bacteremia, which was categorized under catheter-related bloodstream infections for the purpose of this guideline.

The number of patients with catheter-related bloodstream infections in the tunneled catheter group was 2/106 (1.9%), compared to 5/97 (5.2%) in the non-tunneled catheter group. This resulted in a RR of 0.37 (95% CI 0.07 to 1.84), in favor of the tunneled catheter group. This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Timsit (1999) reported the incidence of probable catheter-related sepsis and catheter-related bloodstream infections. For this guideline, both outcomes were categorized under catheter-related bloodstream infections. Due to the absence of a standard deviation for both outcomes, it was impossible to pool both outcome measures into a pooled incidence rate. The results were therefore separately reported.

The number of patients with probable systemic catheter-related sepsis per 100 catheter-days in Timsit (1999) in the tunneled catheter group (n=168) was 0.36, compared to 1.1 in the non-tunneled catheter group (n=168). This resulted in a RR of 0.25 (95% CI 0.09 to 0.72), in favor of the tunneled catheter group. This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

The number of patients with catheter-related bloodstream infections per 100 catheter-days in Timsit (1999) in the tunneled catheter group was 0.073, compared to 0.23 in the non-tunneled catheter group. This resulted in a RR of 0.28 (95% CI 0.03 to 1.92), in favor of the tunneled catheter group. This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Timsit (1996) reported the incidence of catheter-related sepsis and catheter-related bacteremia.

The number of patients with catheter-related sepsis in Timsit (1996) in the tunneled catheter group was 7/117 (6.0%), compared to 18/114 (15.8%) in the non-tunneled catheter group. This resulted in a RR of 0.38 (95% CI 0.16 to 0.87), in favor of the tunneled catheter group.

The number of patients with catheter-related bacteremia in Timsit (1996) in the tunneled catheter group was 4/117 (3.4%), compared to 13/114 (11.4%) in the non-tunneled catheter group. This resulted in a RR of 0.30 (95% CI 0.10 to 0.89), in favor of the tunneled catheter group.

Both results showed that there was a clinically relevant difference in catheter-related bloodstream infections between the tunneled- and non-tunneled cathether group.

Xiao (2021) reported the absolute incidence of catheter-related bloodstream infections. The number of patients with catheter-related bloodstream infections in Xiao (2021) in the tunneled catheter group was 0/64 (0%), compared to 1/65 (1.5%) in the non-tunneled catheter group. This resulted in a RR of 0.34 (95% CI 0.01 to 8.16), in favor of the tunneled catheter group. This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

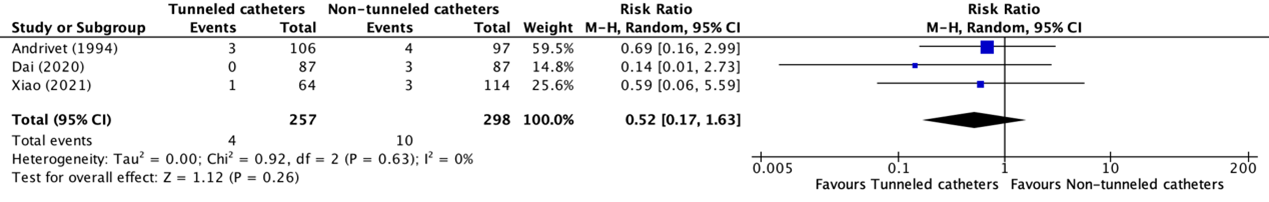

2. (Catheter-related) infection

(Catheter-related) infection was reported in three trials (Andrivet, 1994; Dai, 2020; Xiao, 2021). Andrivet (1994) reported non-bacteremic catheter-related infection, while Dai (2020), and Xiao (2021) reported regular infections. The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of patients with (catheter-related) infections in the tunneled catheter group was 4/257 (1.6%), compared to 10/298 (3.4%) in the non-tunneled catheter group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.52 (95% CI 0.17 to 1.63), in favor of the tunneled catheter group. This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 9. Forest plot showing the comparison between tunneled catheters and non-tunneled catheters for (catheter-related) infection

Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Level of evidence of the literature

1. Catheter-related bloodstream infection

The level of evidence regarding the outcome catheter-related bloodstream infection was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of the wide confidence interval crossing both boundaries of clinical relevance (both imprecision, -2) and because of clinical heterogeneity in the included studies (heterogeneity, -1). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

2. Catheter-related infection

The level of evidence regarding the outcome catheter-related infection was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the included studies (risk of bias, -1) and the wide confidence interval crossing both boundaries of clinical relevance (both imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low.

Table 4. Summary of findings PICO 4

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

- What are the (un)beneficial effects of a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) compared to a port catheter and a tunneled central venous catheter

- What is the additional value for reducing the risk of infectious complications of tunneled vs non-tunneled central venous catheters placement?

PICO 1: Peripherally inserted central (venous) catheters (PICC) versus Port catheter (PAC)

| P: |

Adult patients given central venous access |

| I: |

Peripherally inserted central (venous) catheter |

| C: |

Port catheter |

| O: |

Quality of life, patient satisfaction, complications (such as infections, deep venous thrombosis, catheter-related bloodstream infections, catheter removal, pulmonary embolism), catheter-related intervention rate, and mortality |

PICO 2: Peripherally inserted central (venous) catheters (PICC) versus tunneled venous catheter (CVC)

| P: |

Adult patients given central venous access |

| I: |

Peripherally inserted central (venous) catheters |

| C: |

Tunneled central venous catheter |

| O: |

Quality of life, patient satisfaction, complications (such as infections, deep venous thrombosis, catheter-related bloodstream infections, catheter removal, pulmonary embolism), catheter-related intervention rate, and mortality |

PICO 3: Peripherally inserted central (venous) catheters (PICC) versus non-tunneled central venous line (CVL)

| P: |

Adult patients given central venous access |

| I: |

Peripherally inserted central (venous) catheters |

| C: |

Non-tunneled central venous catheter |

| O: |

Quality of life, patient satisfaction, complications (such as infections, deep venous thrombosis, catheter-related bloodstream infections, catheter removal, pulmonary embolism), catheter-related intervention rate, and mortality |

PICO 4: Tunneled central venous catheters versus non-tunneled central venous catheters

| P: |

Adult patients given central venous access |

| I: |

Tunneled (or cuffed) central venous access |

| C: |

Non-tunneled (or non-cuffed) central venous access |

| O: |

Catheter-related bloodstream infection (i.e., catheter-related sepsis, catheter-related bacteremia) and catheter-related infection |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered mortality, complications (such as infections, deep venous thrombosis, catheter-related bloodstream infections, catheter removal, pulmonary embolism), and patient satisfaction as critical outcome measures for decision making and catheter-related intervention rate, catheter-related infection, and quality of life as important outcome measures for decision making.

As minimal clinically (patient) important differences, the working group used 5% for mortality (risk ratio; RR), 25% for other RR, 10% of the maximum score for continuous outcomes (quality of life scales) and 0.5 for standardized mean differences.

Search and select (Methods)

Two separate literature searches were conducted. For the first search, the databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until the 23rd of August 2022 to investigate the (un)beneficial effects of a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) compared to a port catheter and a tunneled central venous catheter (PICO 1, PICO 2 and PICO 3 of this guideline). The systematic literature search resulted in 536 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials for the optimal type of line for central venous access. Twenty-nine studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, twenty studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and nine studies were included.

Secondly, the databases [Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com)] were searched with relevant search terms until the 10th of January 2023 to investigate the additional value of tunneled versus non-tunneled central venous catheter placement (PICO 4 of this guideline). The systematic literature search resulted in 149 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) about the place of tunneled (versus non-tunneled) CVL to reduce infection risk. Eight studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, three studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five studies were included.

The detailed search strategies are depicted under the tab Methods.

Results

Fourteen studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Andrivet P, Bacquer A, Ngoc CV, Ferme C, Letinier JY, Gautier H, Gallet CB, Brun-Buisson C. Lack of clinical benefit from subcutaneous tunnel insertion of central venous catheters in immunocompromised patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1994 Feb;18(2):199-206. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.2.199. PMID: 8161627.

- Benezra D, Kiehn TE, Gold JW, Brown AE, Turnbull AD, Armstrong D. Prospective study of infections in indwelling central venous catheters using quantitative blood cultures. Am J Med. 1988 Oct;85(4):495-8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(88)80084-6. PMID: 3177396.

- Bjornson HS, Colley R, Bower RH, Duty VP, Schwartz-Fulton JT, Fischer JE. Association between microorganism growth at the catheter insertion site and colonization of the catheter in patients receiving total parenteral nutrition. Surgery. 1982 Oct;92(4):720-7. PMID: 6812229.

- Bozzetti F, Terno G, Camerini E, Baticci F, Scarpa D, Pupa A. Pathogenesis and predictability of central venous catheter sepsis. Surgery. 1982 Apr;91(4):383-9. PMID: 6801797.

- Brandmeir NJ, Davanzo JR, Payne R, Sieg EP, Hamirani A, Tsay A, Watkins J, Hazard SW, Zacko JC. A Randomized Trial of Complications of Peripherally and Centrally Inserted Central Lines in the Neuro-Intensive Care Unit: Results of the NSPVC Trial. Neurocrit Care. 2020 Apr;32(2):400-406. doi: 10.1007/s12028-019-00843-z. PMID: 31556001.

- Chopra V, O'Horo JC, Rogers MA, Maki DG, Safdar N. The risk of bloodstream infection associated with peripherally inserted central catheters compared with central venous catheters in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013 Sep;34(9):908-18. doi: 10.1086/671737. Epub 2013 Jul 26. PMID: 23917904.

- Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S, Woller SC, O'Grady NP, Safdar N, Trerotola SO, Saran R, Moureau N, Wiseman S, Pittiruti M, Akl EA, Lee AY, Courey A, Swaminathan L, LeDonne J, Becker C, Krein SL, Bernstein SJ; Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenouse Catheters (MAGIC) Panel. The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC): Results From a Multispecialty Panel Using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Sep 15;163(6 Suppl):S1-40. doi: 10.7326/M15-0744. PMID: 26369828.

- Clatot F, Fontanilles M, Lefebvre L, Lequesne J, Veyret C, Alexandru C, Leheurteur M, Guillemet C, Gouérant S, Petrau C, Théry JC, Rigal O, Moldovan C, Tennevet I, Rastelli O, Poullain A, Savary L, Bubenheim M, Georgescu D, Gouérant J, Gilles-Baray M, Di Fiore F. Randomised phase II trial evaluating the safety of peripherally inserted catheters versus implanted port catheters during adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2020 Feb;126:116-124. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.11.022. Epub 2020 Jan 10. PMID: 31931269.