Dubbele chirurgische handschoenen

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen in het kader van infectiepreventie?

Aanbeveling

- Het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen ter voorkoming van zorggerelateerde infecties wordt niet aanbevolen.

- Gebruik module Chirurgische handschoenen voor de indicaties voor het routinematig vervangen van enkele chirurgische handschoenen.

- Overweeg het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen bij contact met bot of andere scherpe weefsels om de kans op perforatie van de binnenste handschoen te verminderen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Postoperatieve wondinfecties en door bloedoverdraagbare infecties

Er zijn drie systematische reviews gevonden met daarin twaalf relevante gerandomiseerde, gecontroleerde studies die het dragen van twee paar chirurgische handschoenen (dubbele handschoenen) door het chirurgische team hebben vergeleken met het dragen van één paar chirurgische handschoenen. In geen van deze studies is het effect op POWI’s bij de patiënt of door bloedoverdraagbare infecties bij de patiënt of het chirurgisch team onderzocht. Er is dus geen conclusie te trekken met betrekking tot het effect van het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen op de cruciale uitkomstmaten POWI’s bij de patiënt of door bloedoverdraagbare infecties bij de patiënt of het chirurgisch team.

Perforaties van de chirurgische handschoen

In alle twaalf gevonden studies is het effect van het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen op de belangrijke uitkomstmaten perforaties van de binnenste en buitenste handschoen onderzocht in laag-risico chirurgische specialismen. Het dragen van twee in plaats van één paar standaard chirurgische handschoenen resulteerde in een klinisch relevante relatieve reductie van 76% (van 20,5% naar 4,6%) in het optreden van perforaties van de binnenste handschoen.

Overige overwegingen

De aanbevelingen in internationale richtlijnen zijn niet eenduidig. Het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen tijdens invasieve/chirurgische procedures wordt aanbevolen door de Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN), de American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) en de National Institute of Health (NIH) (AORN, 2007; AAOS, 2012; Anderson, 2014) om de kans op perforatie te verkleinen. Terwijl de WHO geen aanbeveling doet, omdat er enerzijds geen trials zijn gevonden over door bloedoverdraagbare infecties in relatie tot handschoen gebruik, en anderzijds omdat er onvoldoende bewijs is ten aanzien van het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen om POWI’s te verminderen. (WHO, 2009; WHO, 2018).

Het dragen van twee paar chirurgische handschoenen (dubbele handschoenen) wordt in de praktijk vooral toegepast bij orthopedische en traumachirurgische ingrepen, omdat scherp instrumentarium en bot de kans op perforatie kunnen verhogen.

Bij andere chirurgische specialismen is het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen minder gebruikelijk en wordt, naast het niet bewezen nut, vanwege negatieve effecten op de tastgevoeligheid en behendigheid de voorkeur gegeven aan het dragen van een enkel paar handschoenen (Patterson, 1998; St. Germaine, 2003; Matta, 1988).

Voor prik-, snij- en spataccidenten wordt verwezen naar de richtlijn Accidenteel bloedcontact.

De indicaties voor het routinematig wisselen van chirurgische handschoenen staan in module Chirurgische handschoenen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Het voorkomen van POWI’s is in het belang van de patiënt. Nu er geen bewijs is voor het gebruik van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen op wondinfecties, maar ook geen duidelijk nadelig effect, zijn de waarden van patiënt niet in het gedrang.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen brengt kosten met zich mee.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen tijdens operaties is een wijdverbreid gebruik binnen de orthopedie en traumatologie. Het is twijfelachtig of deze praktijk gewijzigd zal worden. Wel is het van belang te benadrukken dat er geen enkele onderbouwing in het kader van infectiepreventie is voor het gebruik van dubbele handschoenen. Dit vergt aandacht bij de implementatie van deze richtlijn.

Duurzaamheid en hergebruik

Uit duurzaamheidsoogpunt moet worden voorkomen dat er onnodig dubbele chirurgische handschoenen worden gedragen. Het is daarom belangrijk om bewustwording te creëren over de afwezigheid van het risico op zorggerelateerde infecties.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De literatuur toont op dit moment geen bewijs dat het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen door de operateur postoperatieve wondinfecties voorkomt. Ook is er geen literatuur over het beschermende effect op bloedoverdraagbare aandoeningen. Er is bewijs dat het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen zorgt voor een lager aantal perforaties van de binnenste handschoen. Er is geen aanwijzing dat dit ook voor een reductie in postoperatieve wondinfecties of bloedoverdraagbare aandoeningen zorgt.

De werkgroep is van mening dat er, om andere redenen dan deze, gekozen kan worden voor het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen, zoals het voorkomen van contact met bloed van de patiënt, bijvoorbeeld bij gebruik van scherp instrumentarium zoals een zaag of contact met scherpe weefsels. Daarin moet op individuele basis een afweging worden gemaakt of dit voordeel opweegt tegen de verhoogde kosten, de lagere duurzaamheid en de verminderde tactiliteit.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Steriele chirurgische handschoenen behoren tot de persoonlijke beschermingsmiddelen van het chirurgisch team. Handschoenen vormen een beschermende barrière tussen het chirurgisch team en de patiënt, die enerzijds contaminatie van de operatiewond voorkomt en anderzijds blootstelling van het chirurgisch team aan onder andere het bloed van de patiënt.

Intra-operatieve perforaties van chirurgische handschoenen komen voor en zijn vaak onzichtbaar. Naast intra-operatief ontstane perforaties kunnen ook in nog niet gebruikte handschoenen perforaties aanwezig zijn (Thomas, 2001). In de literatuur wordt perforatie van de handschoen soms als indirecte maat voor postoperatieve wondinfectie (POWI’s) genomen. Er zijn echter op dit moment geen studies beschikbaar die deze relatie in klinisch verband aantonen (Jahangiri, 2022; Jid, 2017; Junker, 2012; Kang, 2018; Lee, 2017). Ten aanzien van door bloedoverdraagbare infecties: in het verleden is een transmissie kans van 0,3% genoemd bij een percutane blootstelling aan bloed van een patiënt met hiv (Henderson, 1990). Dit was vóór de tijd van effectieve hiv-medicatie. Bij gebruik van post-exposure profylaxe op indicatie is in een grote studie geen enkele transmissie gevonden (Lee, 2023). De transmissie kans voor hepatitis B is 10% bij een niet-gevaccineerde medewerker en voor hepatitis C 1,5% (Tarantola, 2006). Deze getallen moeten worden beschouwd in het licht van onderrapportage van prikaccidenten en het feit dat dankzij goede medicatie de virale load van hiv nu veelal laag is en veel medewerkers gevaccineerd zijn tegen hepatitis B. Het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen vermindert de kans dat bloed en lichaamsvochten in aanraking komen met de handen van de medewerker in geval van perforatie. Toch wordt in de richtlijn van de World Health Organization (WHO) (Global guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2018) genoemd dat er geen trials zijn gevonden over bloedoverdraagbare infecties in relatie tot handschoengebruik. De conclusie is dat er onvoldoende bewijs is om een aanbeveling te doen voor het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen en het wisselen van handschoenen tijdens operaties om postoperatieve infecties te verminderen.

In deze module wordt gesproken over dubbele chirurgische handschoenen. Hiermee worden dubbele steriele, chirurgische handschoenen bedoeld.

Praktijkvariatie

Het dragen van twee paar chirurgische handschoenen (dubbele handschoenen) wordt in de praktijk vooral toegepast bij orthopedische en traumachirurgische ingrepen, omdat contact met scherp instrumentarium zoals een zaag en contact met bot de kans op perforatie kan verhogen. Ook bij andere chirurgische handelingen zoals knopen leggen bij stugge weefsels ontstaan regelmatig perforaties van handschoenen (Enz, 2022). Bij andere chirurgische specialismen is het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen minder gebruikelijk en wordt, naast het niet bewezen nut, vanwege negatieve effecten op de tastgevoeligheid en behendigheid de voorkeur gegeven aan het dragen van een enkel paar handschoenen (Patterson, 1998; St. Germaine, 2003; Matta, 1988).

In de praktijk wordt bij perforatie van de buitenste handschoen alleen de buitenste handschoen vervangen. De binnenste handschoen wordt alleen vervangen wanneer deze zichtbaar geperforeerd is.

De indicaties voor het routinematig wisselen van chirurgische handschoenen staan in module Chirurgische handschoenen).

De aanbevelingen in internationale richtlijnen zijn niet eenduidig. Het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen tijdens invasieve/chirurgische procedures wordt aanbevolen door de Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN), de American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) en de National Institute of Health (NIH) (AORN, 2007; AAS, 2012; Anderson, 2014), terwijl de WHO geen aanbeveling doet (WHO, 2009; WHO, 2018).

Afbakening

Om perforatie detectie te verbeteren worden soms gekleurde onderhandschoenen gebruikt, deze noemt men indicatorhandschoenen. Deze voldoen meestal aan dezelfde norm als standaardhandschoenen. Om pragmatische redenen is de literatuursearch uitgevoerd met zoekterm standaard dubbele chirurgische handschoenen.

Het dragen van dubbele chirurgische handschoenen voor de toediening van bijvoorbeeld cytostatica is geen infectiepreventie en valt daarom buiten de scope van deze richtlijn.

Voor prik-, snij- en spataccidenten wordt verwezen naar de richtlijn Accidenteel bloedcontact.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found for the effect of double gloving of the surgical team with standard sterile surgical gloves on the risk of surgical site infections in surgical patients when compared with single gloving with standard sterile surgical gloves.

Source: - |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found for the effect of double gloving of the surgical team with standard sterile surgical gloves on the risk of bloodborne infections in surgical patients when compared with single gloving with standard sterile surgical gloves.

Source: - |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found for the effect of double gloving of the surgical team with standard sterile surgical gloves on the risk of bloodborne infections in surgical team members when compared with single gloving with standard sterile surgical gloves.

Source: - |

|

Low GRADE |

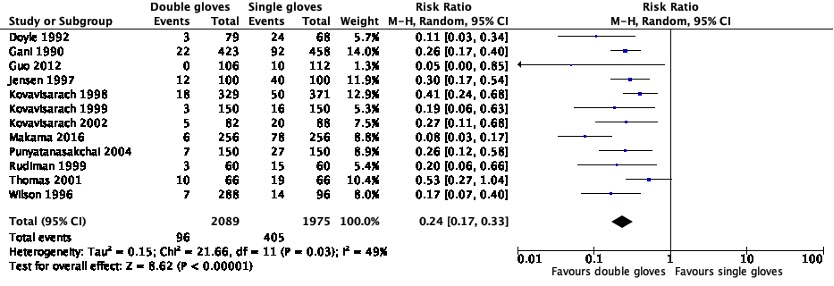

The evidence suggests that double gloving of the surgical team with standard sterile surgical gloves reduces the risk of inner glove perforations when compared with single gloving with standard sterile surgical gloves.

Source: Doyle, 1992; Gani, 1990; Guo, 2012; Jensen, 1997; Kovavisarach, 1998; Kovavisarach, 1999; Kovavisarach, 2002; Makama, 2016; Punyatanasakchai, 2004; Rudiman, 1999; Thomas, 2001; Wilson, 1996 |

Samenvatting literatuur

The review by Tanner (2009) is the second update of a Cochrane systematic review on double gloving of the surgical team compared with single gloving to reduce surgical cross-infections (Tanner, 2002).

For the second update, the Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (June 2009), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Issue 2, 2009), Ovid MEDLINE (1950 to May Week 5, 2009), Ovid EMBASE (1980 to 2009 Week 22, and Ovid CINAHL (1982 to May Week 4 2009) were searched for randomized controlled trials.

Criteria for inclusion of studies were: 1) RCT, irrespective of language or publication status; 2) study includes any member of the surgical team (surgeon, second or assistant surgeon and scrub staff) practicing in a designated surgical theatre, in any surgical specialty, in any country; 3) study compares two or more glove types (single gloves, double gloves, glove liners, colored perforation indicator systems, cloth outer gloves, steel outer gloves, triple gloves); 4) study describes at least surgical site infections in surgical patients, glove perforations, or bloodborne infections in post-operative patients or the surgical team as an outcome.

In total, 31 RCTs were included, 20 of which compared double with single gloving (Aarnio, 2001; Avery, 1999; Berridge, 1998; Caillot, 1999; Doyle, 1992; Gani, 1990; Jensen, 1997; Kovavisarach, 1998; Kovavisarach, 1999; Kovavisarach, 2002; Laine, 2001; Laine, 2004A; Laine, 2004B; Marín Bertolin, 1997; Naver, 2000; Punyatanasakchai, 2004; Rudiman, 1999; Thomas, 2001; Turnquest, 1996; Wilson, 1996). Studies were assessed for methodological quality, including the method of randomisation, allocation concealment, blinded outcome assessment, and methods for outcome assessment.

The review by Mischke (2014) is a Cochrane systematic review on using extra gloves or special types of gloves by healthcare workers compared with single standard gloves to reduce percutaneous exposure incidents. The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, NHSEED, Science Citation Index Expanded, CINAHL, OSH-update (NIOSHTIC and CISDOC), and PsycINFO were searched for randomized controlled trials from inception to September 2013. In addition, the databases of WHO, the UK National Health Service (NHS) and the International Healthcare Worker Safety Center were searched from inception until September 2013.

Criteria for inclusion of studies were: 1) RCT, irrespective of language, publication status or blinding; 2) study includes healthcare workers (at least 75% of study population); 3) study compares the number of glove layers and/or special gloves; 4) study describes at least needlestick injury, sharps injury, blood stains inside the gloves or on the skin, glove perforations or dexterity as an outcome.

In total, 34 RCTs were included, 20 of which compared double with single gloving (Aarnio,2001; Avery, 1999; Berridge, 1998; Doyle, 1992; Gani, 1990; Jensen, 1997; Kovavisarach, 1998; Kovavisarach, 1999; Kovavisarach, 2002; Laine, 2001; Laine, 2004A; Laine, 2004B; Marín Bertolin, 1997; Naver, 2000; Punyatanasakchai, 2004; Quebbeman, 1992; Rudiman, 1999; Thomas, 2001; Turnquest, 1996; Wilson, 1996). The authors excluded one study from the meta-analysis because 28% of the participants switched from the intervention to the control group or vice versa (Quebbeman, 1992). Risk of bias in the included studies was assessed with the RevMan 5 ‘Risk of bias’ tool for the following domains, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data and selective outcome reporting.

Zhang (2021) performed a systematic review on the effect of double gloving of the surgical team compared with single gloving on the surgical glove perforation rate. The electronic databases Embase, CINAHL, OVID, Medline, Pubmed, Web of Science and Foreign Medical Literature Retrieval Service (FRMS) were searched from inception to March 18, 2020, for randomized controlled trials. Criteria for inclusion of studies were: 1) RCT; 2) study includes surgical patients in the operating room (not surgical patients in clinical treating room or animals); 3) study compares double gloving with single gloving (not indicator gloving system, special gloves or changing of gloves); 4) study describes glove perforations as an outcome; and 5) study is published in English.

In total, 7 RCTs were included, all comparing double with single gloving (Guo 2012, Kovavisarach 1998, Kovavisarach 1999, Kovavisarach 2002, Makama 2016, Punyatanasakchai 2004, Thomas 2001). The Cochrane Collaboration tool (Cochrane Library Handbook 5.1.0) was used to assess the risk of bias for the following domains: randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data and selective outcome reporting.

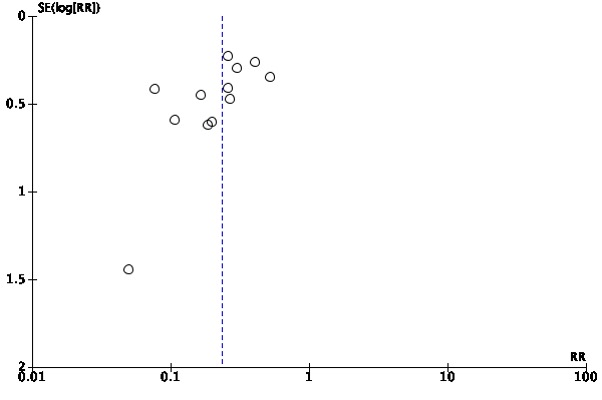

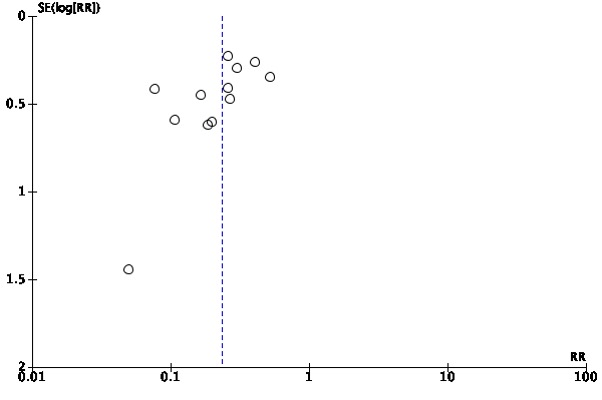

To answer the search question of the current module, ten of 20 studies from the systematic review by Tanner (2009) that compared double with single gloving were eligible. Ten studies were excluded: six studies had indicator inner gloves as the intervention (Aarnio, 2001; Avery, 1999; Laine, 2001; Laine, 2004A; Laine, 2004B; Naver, 2000), one study had vinyl inner gloves as the intervention (Marín Bertolin, 1997), one study had orthopedic gloves as the comparator (Turnquest 1996), one study did not report the type of gloves used (Berridge, 1998), and one study did not report sufficient data on the number of gloves and inner glove perforations (Caillot, 1999). Ten of 19 studies from the systematic review by Mischke (2014) that compared double with single gloving were eligible. Nine studies were excluded: six studies had indicator inner gloves as the intervention (Aarnio, 2001; Avery, 1999; Laine, 2001; Laine, 2004A; Laine, 2004B; Naver, 2000), one study had vinyl inner gloves as the intervention (Marín Bertolin, 1997), one study had orthopedic gloves as the comparator (Turnquest 1996), and one study did not report the type of gloves used (Berridge, 1998). All seven studies included in the systematic review by Zhang (2021) were eligible. In total, 12 studies from the three systematic reviews were included. All studies were performed in low-risk surgical specialties, the majority in low-income countries, and all had inner and/or outer glove perforation as the outcome (Table 1). Most studies provided insufficient information on random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of the outcome assessor and/or frequency of missing data (see Evidence tables). All studies were judged to be at high risk of bias because of the impossibility to blind the participants for the intervention; knowledge of wearing single our double gloves may have influenced performance and herewith the study outcomes. In addition, two studies used the patients hospital number (odd or even) for randomization (Gani, 1990; Rudiman, 1999), two studies had the outcome assessed by the glove wearer (self-evaluation) (Gani, 1990; Rudiman, 1999), in four studies gloves were labelled with the gloving method prior to outcome assessment (Guo, 2012; Kovavisarach, 1998; Kovavisarach, 1999; Punyatanasakchai, 2004), and one study had a high frequency of missing outcome data (Rudiman, 1999). Funnel plots were symmetric, suggesting the absence of publication bias (see Funnel plots).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies |

||||||||

|

Study |

Systematic review |

Country |

Type of surgery |

Procedure |

Participants |

Glove manufacturer |

Outcome |

Outcome assessment |

|

Doyle, 1992 |

TM |

United Kingdom |

Obstetric and gynecology surgery |

Procedures involving sharp instruments |

Surgeons Surgeon assistants |

Not reported |

Inner and outer glove perforation |

Water leak method (500 ml, squeeze) |

|

Gani, 1990 |

TM |

Australia |

General surgery |

Different types of procedures, excluding microsurgical procedures |

Surgeons Surgeon assistants Scrub nurses |

Ansell |

Inner and outer glove perforation |

Water leak method (500 ml) |

|

Guo, 2012 |

Z |

China (Hongkong) |

Multiple surgical specialties (no orthopedic surgery) |

Different abdominal procedures |

Scrub nurses |

Ansell |

Inner and outer glove perforation |

Air inflation method Water leak method (no further details) |

|

Jensen, 1997 |

TM |

Denmark |

Abdominal surgery |

Not specified |

Surgeons Surgeon assistants |

Ansell |

Inner and outer glove perforation |

Water leak method (no further details) |

|

Kovavisarach, 1998 |

TMZ |

Thailand |

Obstetric and gynecology surgery |

Perineorrhaphy |

Surgeons |

Not reported |

Inner and outer glove perforation |

Air inflation method |

|

Kovavisarach, 1999 |

TMZ |

Thailand |

Obstetric and gynecology surgery |

Caesarean section |

Surgeons |

Ansell |

Inner and outer glove perforation |

Air inflation method |

|

Kovavisarach, 2002 |

TMZ |

Thailand |

Obstetric and gynecology surgery |

Abdominal hysterectomy |

Surgeons |

Ansell |

Inner and outer glove perforation |

Air inflation method |

|

Makama, 2016 |

Z |

Nigeria |

Multiple surgical specialties (no orthopedic surgery) |

Different types of procedures |

Surgeons Surgeon assistants Scrub nurses |

Ideal Medical Industries |

Inner and outer glove perforation |

Air inflation method Water leak method (no further details) |

|

Punyatanasakchai, 2004 |

TMZ |

Thailand |

Obstetric and gynecology surgery |

Perineorrhaphy |

Surgeons |

Medigloves |

Inner and outer glove perforation |

Water leak method (500 ml, squeeze) |

|

Rudiman, 1999 |

TM |

Indonesia |

General surgery |

Laparotomy |

Surgeons Surgeon assistants |

Johnson and Johnson |

Inner and outer glove perforation |

Water leak method (500 ml) |

|

Thomas, 2001 |

TMZ |

India |

General surgery |

Surgical procedure lasting more than 1 hour |

Surgeons Surgeon assistants |

Dial Rubber Industries |

Inner and outer glove perforation |

Air inflation method Water leak method (no further details) |

|

Wilson, 1996 |

TM |

Oman |

Multiple surgical specialties |

Different types of procedures |

Surgeons |

Not reported |

Inner glove perforation |

Water leak method (squeeze) |

T = Tanner, 2009; M = Mischke, 2014; Z = Zhang, 2021

Results

Surgical site infection in surgical patients

None of the 12 studies comparing single and double gloving with standard sterile surgical gloves reported on the occurrence of surgical site infections in surgical patients.

Bloodborne infection in surgical patients

None of the 12 studies comparing single and double gloving with standard sterile surgical gloves reported on the occurrence of bloodborne infections in surgical patients.

Bloodborne infection in surgical team members

None of the 12 studies comparing single and double gloving with standard sterile surgical gloves reported on the occurrence of bloodborne infections in surgical team members.

Inner glove perforation

Twelve studies, all carried out in low-risk surgical specialties, compared the rate of inner glove perforations between single and double gloving with standard sterile surgical gloves. The inner glove pair perforation rate, calculated as the proportion of inner glove pairs that was perforated, was 20.5% (405/1,975; range 8.9% to 40.0%) for single gloving compared with 4.6% (96/2,089; range 0.0% - 15.2%) for double gloving. A random effects model showed a clinically relevant 76% relative risk reduction in the inner glove perforation rate in favor of double gloving (RRpooled 0.24; 95% CI 0.17 to 0.33).

Figure 1. Forest plot of inner glove pair perforations for standard single gloves versus standard double gloves (pooled risk ratio, random effects model).

Level of evidence of the literature

Surgical site infection in surgical patients

For surgical site infections in surgical patients, the level of evidence could not be assessed due to the absence of relevant studies.

Bloodborne infection in surgical patients

For bloodborne infections in surgical patients, the level of evidence could not be assessed due to the absence of relevant studies.

Bloodborne infection in surgical team members

For bloodborne infections in surgical team members, the level of evidence could not be assessed due to the absence of relevant studies.

Inner glove perforation

For inner glove perforations, the level of evidence started at high and was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations, including the impossibility of blinding of participants, and the lack of blinding of outcome assessors (risk of bias; -1), and indirectness of the outcome measure (indirectness; -1).

Zoeken en selecteren

Search questions

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effect of double gloving (wearing two pairs of standard sterile surgical gloves) by the surgical team compared with single gloving (wearing one pair of standard sterile surgical gloves) on the occurrence of surgical site infections and bloodborne infections in surgical patients, bloodborne infections in surgical team members, and inner and outer glove perforations?

P: Surgical team members (surgeon, second or assistant surgeon and scrub staff)

I: Double gloving (wearing two pairs of standard sterile surgical gloves)

C: Single gloving (wearing one pair of standard sterile surgical gloves)*

O: Surgical site infection in surgical patients, bloodborne infection in surgical patients, bloodborne infection in surgical team members, inner glove perforation (indirect measure of the risk of surgical site infection and bloodborne infection)

* Single glove pairs serve as the comparator for both inner and outer glove pair perforations

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered surgical site infections in surgical patients and bloodborne infections in surgical patients or surgical team members as critical outcome measures for decision-making, and inner glove perforations as important outcome measures for decision-making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies. Inner glove perforations are considered an indirect measure of the risk of infection.

For surgical site infections in surgical patients, the working group defined a 25% relative difference for dichotomous outcomes (RR < 0.8 or > 1.25) as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

For bloodborne infections in surgical patients, the working group defined a 25% relative difference for dichotomous outcomes (RR < 0.8 or > 1.25) as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

For bloodborne infections in surgical team members, the working group defined a 25% relative difference for dichotomous outcomes (RR < 0.8 or > 1.25) as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

For inner glove perforations, the working group defined a 25% relative difference for dichotomous outcomes (RR < 0.8 or > 1.25) as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

For outer glove perforations, the working group defined a 25% relative difference for dichotomous outcomes (RR < 0.8 or > 1.25) as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (methods)

Embase, Ovid/Medline, Cinahl and Web of Science databases were searched with relevant search terms for systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials on double gloving until March 7, 2023. The detailed search strategy is available upon reasonable request via info@sri-richtlijnen.nl. The systematic literature search resulted in 282 unique hits.

Studies were selected based on the following eligibility criteria:

- Systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (with detailed search strategy, search in at least two relevant databases, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available) or RCT.

- Study includes surgical patients or surgical team members in any surgical specialty in any country.

- Study compares double gloving of the surgical team with single gloving.

- Study describes surgical site infection, bloodborne infection in surgical patients,

- Bloodborne infection in surgical team members, or glove perforation as an outcome.

- Full text is available.

- Full text is written in English or Dutch.

Thirty-one studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 28 studies were excluded (see Table of Excluded studies), and three studies were included. The reference lists of excluded reviews were checked for studies that fulfilled the eligibility criteria but were not retrieved in the systematic literature search. This did not result in additional studies.

Results

Three systematic reviews were included in the analysis of the literature. The quality assessment of the systematic reviews is summarized in the Quality assessment table. Important study characteristics and results for the individual studies are summarized in the Evidence table.

Referenties

- Aarnio P, Laine T. Glove perforation rate in vascular surgery--a comparison between single and double gloving. Vasa. 2001 May;30(2):122-4. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526.30.2.122. PMID: 11417282.

- Avery CM, Gallagher P, Birnbaum W. Double gloving and a glove perforation indication system during the dental treatment of HIV-positive patients: are they necessary? Br Dent J. 1999 Jan 9;186(1):27-9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800009. PMID: 10028739.

- Berridge DC, Starky G, Jones NA, Chamberlain J. A randomized controlled trial of double-versus single-gloving in vascular surgery. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1998 Feb;43(1):9-10. PMID: 9560497.

- Caillot JL, Côte C, Abidi H, Fabry J. Electronic evaluation of the value of double gloving. Br J Surg. 1999 Nov;86(11):1387-90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01266.x. PMID: 10583283.

- Doyle PM, Alvi S, Johanson R. The effectiveness of double-gloving in obstetrics and gynaecology. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992 Jan;99(1):83-4. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb14402.x. PMID: 1547183.

- Enz A, Klinder A, Bisping L, Lutter C, Warnke P, Tischer T, Mittelmeier W, Lenz R. Knot tying in arthroplasty and arthroscopy causes lesions to surgical gloves: a potential risk of infection. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023 May;31(5):1824-1832. doi: 10.1007/s00167-022-07136-7. Epub 2022 Sep 1. PMID: 36048202; PMCID: PMC10089991.

- Gani JS, Anseline PF, Bissett RL. Efficacy of double versus single gloving in protecting the operating team. Aust N Z J Surg. 1990 Mar;60(3):171-5. PMID: 2327922.

- Guo YP, Wong PM, Li Y, Or PP. Is double-gloving really protective? A comparison between the glove perforation rate among perioperative nurses with single and double gloves during surgery. Am J Surg. 2012 Aug;204(2):210-5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.08.017. Epub 2012 Feb 17. PMID: 22342011.

- Jensen SL, Kristensen B, Fabrin K. Double gloving as self protection in abdominal surgery. Eur J Surg. 1997 Mar;163(3):163-7. PMID: 9085056.

- Kovavisarach E, Jaravechson S. Comparison of perforation between single and double-gloving in perineorrhaphy after vaginal delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998 Feb;38(1):58-60. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1998.tb02959.x. PMID: 9521392.

- Kovavisarach E, Vanitchanon P. Perforation in single- and double-gloving methods for cesarean section. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999 Dec;67(3):157-61. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(99)00159-9. PMID: 10659898.

- Kovavisarach E, Seedadee C. Randomised controlled trial of glove perforation in single and double-gloving methods in gynaecologic surgery. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002 Nov;42(5):519-21. doi: 10.1111/j.0004-8666.2002.00519.x. PMID: 12495099.

- Laine T, Aarnio P. How often does glove perforation occur in surgery? Comparison between single gloves and a double-gloving system. Am J Surg. 2001 Jun;181(6):564-6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00626-2. PMID: 11513787.

- Laine T, Aarnio P. Glove perforation in orthopaedic and trauma surgery. A comparison between single, double indicator gloving and double gloving with two regular gloves. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004 Aug;86(6):898-900. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b6.14821. PMID: 15330033. A Laine T, Kaipia A, Santavirta J, Aarnio P. Glove perforations in open and laparoscopic abdominal surgery: the feasibility of double gloving. Scand J Surg. 2004;93(1):73-6. doi: 10.1177/145749690409300116. PMID: 15116826.

- BMakama JG, Okeme IM, Makama EJ, Ameh EA. Glove Perforation Rate in Surgery: A Randomized, Controlled Study To Evaluate the Efficacy of Double Gloving. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2016 Aug;17(4):436-42. doi: 10.1089/sur.2015.165. Epub 2016 Mar 16. PMID: 26981792.

- Marín-Bertolín S, González-Martínez R, Giménez CN, Marquina Vila P, Amorrortu-Velayos J. Does double gloving protect surgical staff from skin contamination during plastic surgery? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997 Apr;99(4):956-60. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199704000-00003. PMID: 9091940.

- Naver LP, Gottrup F. Incidence of glove perforations in gastrointestinal surgery and the protective effect of double gloves: a prospective, randomised controlled study. Eur J Surg. 2000 Apr;166(4):293-5. doi: 10.1080/110241500750009113. PMID: 10817324.

- Punyatanasakchai P, Chittacharoen A, Ayudhya NI. Randomized controlled trial of glove perforation in single- and double-gloving in episiotomy repair after vaginal delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004 Oct;30(5):354-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2004.00208.x. PMID: 15327447.

- Rudiman R, Karnadihardja W, Ruchiyat Y, Hanafi B. Efficacy of double versus single gloving in laparotomy procedures. Asian J Surg 1999;22:85-8.

- Tanner J, Parkinson H. Double gloving to reduce surgical cross-infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Jul 19;2006(3):CD003087 (update 2009). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003087.pub2. PMID: 16855997; PMCID: PMC7173754.

- Thomas S, Agarwal M, Mehta G. Intraoperative glove perforation--single versus double gloving in protection against skin contamination. Postgrad Med J. 2001 Jul;77(909):458-60. doi: 10.1136/pmj.77.909.458. PMID: 11423598; PMCID: PMC1760980.

- Turnquest MA, How HY, Allen SA, Voss DH, Spinnato JA. Perforation rate using a single pair of orthopedic gloves vs. a double pair of gloves in obstetric cases. J Matern Fetal Med. 1996 Nov-Dec;5(6):362-5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(199611/12)5:6<362::AID-MFM14>3.0.CO;2-J. PMID: 8972416.

- Wilson SJ, Sellu D, Uy A, Jaffer MA. Subjective effects of double gloves on surgical performance. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1996 Jan;78(1):20-2. PMID: 8659967; PMCID: PMC2502654.

- Zhang Z, Gao X, Ruan X, Zheng B. Effectiveness of double-gloving method on prevention of surgical glove perforations and blood contamination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2021 Sep;77(9):3630-3643. doi: 10.1111/jan.14824. Epub 2021 Mar 17. PMID: 33733484.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Information statement. Preventing the transmission of bloodborne pathogens. 2001, revised 2012. Available at: www.aaos.org/about/bylaws-policies/statements--resolutions/information-statements

- Anderson DJ, Podgorny K, Berríos-Torres SI, Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Greene L, Nyquist AC, Saiman L, Yokoe DS, Maragakis LL, Kaye KS. Strategies to prevent surgical site infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014 Jun;35(6):605-27. doi: 10.1086/676022. PMID: 24799638; PMCID: PMC4267723.

- Association of periOperative Registered Nurses. Recommended practices for prevention of transmissible infections in the perioperative practice setting. AORN J. 2007 Feb;85(2):383-96. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(07)60049-0. PMID: 17328148; PMCID: PMC7111149.

- Henderson DK, Fahey BJ, Willy M, Schmitt JM, Carey K, Koziol DE, Lane HC, Fedio J, Saah AJ. Risk for occupational transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) associated with clinical exposures. A prospective evaluation. Ann Intern Med. 1990 Nov 15;113(10):740-6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-10-740. PMID: 2240876.

- Jahangiri M, Choobineh A, Malakoutikhah M, Hassanipour S, Zare A. The global incidence and associated factors of surgical gloves perforation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work. 2022;71(4):859-869. doi: 10.3233/WOR-210286. PMID: 35253703.

- Jid LQ, Ping MW, Chung WY, Leung WY. Visible glove perforation in total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2017 Jan;25(1):2309499017695610. doi: 10.1177/2309499017695610. PMID: 28228047.

- Junker T, Mujagic E, Hoffmann H, Rosenthal R, Misteli H, Zwahlen M, Oertli D, Tschudin-Sutter S, Widmer AF, Marti WR, Weber WP. Prevention and control of surgical site infections: review of the Basel Cohort Study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012 Sep 4;142:w13616. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13616. PMID: 22949137.

- Kang MS, Lee YR, Hwang JH, Jeong ET, Son IS, Lee SH, Kim TH. A cross-sectional study of surgical glove perforation during the posterior lumbar interbody spinal fusion surgery: Its frequency, location, and risk factors. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Jun;97(22):e10895. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010895. PMID: 29851813; PMCID: PMC6393005.

- Lee JH, Cho J, Kim YJ, Im SH, Jang ES, Kim JW, Kim HB, Jeong SH. Occupational blood exposures in health care workers: incidence, characteristics, and transmission of bloodborne pathogens in South Korea. BMC Public Health. 2017 Oct 18;17(1):827. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4844-0. PMID: 29047340; PMCID: PMC5648449.

- Matta H, Thompson AM, Rainey JB. Does wearing two pairs of gloves protect operating theatre staff from skin contamination? BMJ. 1988 Sep 3;297(6648):597-8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6648.597. PMID: 3139230; PMCID: PMC1834526.

- Mischke C, Verbeek JH, Saarto A, Lavoie MC, Pahwa M, Ijaz S. Gloves, extra gloves or special types of gloves for preventing percutaneous exposure injuries in healthcare personnel. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Mar 7;(3):CD009573. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009573.pub2. PMID: 24610769.

- Patterson JM, Novak CB, Mackinnon SE, Patterson GA. Surgeons' concern and practices of protection against bloodborne pathogens. Ann Surg. 1998 Aug;228(2):266-72. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199808000-00017. PMID: 9712573; PMCID: PMC1191469.

- St Germaine RL, Hanson J, de Gara CJ. Double gloving and practice attitudes among surgeons. Am J Surg. 2003 Feb;185(2):141-5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)01217-5. PMID: 12559444.

- Tanner J, Parkinson H. Double gloving to reduce surgical cross-infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(3):CD003087. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003087. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD003087. PMID: 12137673.

- Tarantola A, Abiteboul D, Rachline A. Infection risks following accidental exposure to blood or body fluids in health care workers: a review of pathogens transmitted in published cases. Am J Infect Control. 2006 Aug;34(6):367-75

- World Health Organization. WHO Guideline for safe surgery. 2009. Available at: www.who.int.

- World Health Organization. WHO Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infections. 2018. Available at: www.who.int

Evidence tabellen

Evidence-tabel

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?

Yes/no/unclear/ not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough Similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Tanner, 2009 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

SR: no Individual studies: yes or unclear |

|

Mischke, 2014 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

SR: no Individual studies: yes or unclear |

|

Zhang, 2021 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

SR: no Individual studies: yes or unclear |

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Tanner, 2009 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to June 2009

Studies1 A: Doyle, 1992 B: Gani, 1990 C: Jensen, 1997 D: Kovavisarach, 1998 E: Kovavisarach, 1999 F: Kovavisarach, 2002 G: Punyatanasakchai, 2004 H: Rudiman, 1999 I: Thomas, 2001 J: Wilson, 1996

Study design RCT

Setting Hospital

Country A: United Kingdom B: Australia C: China D: Thailand E: Thailand F: Thailand G: Thailand H: Indonesia I: India J: Oman

Source of funding and conflicts of interest SR: Funding by Theatre Nurses Trust Fund, The University of Leeds, Derby Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and The National Association of Theatre Nurses; no conflicts of interest A: Not reported B: Not reported C: Gloves provided by manufacturer; conflicts of interest not reported D: Not reported E: Not reported F: Not reported G: Not reported H: Full text not available I: Not reported J: Not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR 1) Randomized controlled trial, irrespective of language or publication status 2) Study includes any member of the surgical team (surgeon, second or assistant surgeon and scrub staff) practicing in a designated surgical theatre, in any surgical specialty, in any country 3) Study compares two or more glove types (single gloves, double gloves, glove liners, coloured perforation indicator systems, cloth outer gloves, steel outer gloves, triple gloves) 4) Study describes at least surgical site infections in surgical patients, glove perforations, or bloodborne infections in post- operative patients or the surgical team as an outcome

31 studies included by the authors, 20 of which compared single and double standard sterile surgical latex gloves. Of those, 10 were excluded from the meta-analysis to answer the search question - indicator inner glove as intervention (n=6) - vinyl inner glove as intervention (n=1) - orthopedic glove as comparator (n=1) - type of glove not reported (n=1) - insufficient data on number of gloves and glove perforations (n=1)

N glove pairs A: 226 B: 1,317 C: 300 D: 1,029 E: 450 F: 252 G: 450 H: 180 I: 198 J: 384

Type of surgery A: Obstetrics and gynecology B: General C: Abdominal D: Obstetrics and gynecology E: Obstetrics and gynecology F: Obstetrics and gynecology G: Obstetrics and gynecology H: General I: General J: Multiple specialties

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported |

Intervention Double standard surgical latex glove |

Control Single standard surgical latex glove |

Endpoint of follow-up End of surgical procedure

For how many glove pairs were no complete outcome data available? (n/N) A: 3/150 B: 15/233 C: Not reported D: Not reported E: Not reported F: Not reported G: Not reported H: 12/72 I: Not reported J: Not reported

|

Inner glove pair perforations

Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: A: 0.11 [0.03 to 0.34] B: 0.26 [0.17 to 0.40] C: 0.30 [0.17 to 0.54] D: 0.41 [0.24 to 0.68] E: 0.19 [0.06 to 0.63] F: 0.27 [0.11 to 0.68] G: 0.26 [0.12 to 0.58] H: 0.20 [0.06 to 0.66] I: 0.53 [0.27 to 1.04] J: 0.17 [0.07 to 0.40]

Pooled effect(random effects model: 0.28 [0.22 to 0.36] favoring double gloves Heterogeneity (I2): 12%

Outer glove pair perforations

Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: A: 0.75 [0.46 to 1.23] B: 1.05[0.81 to 1.36] C: 1.18 [0.86 to 1.61] D: 0.88 [0.59 to 1.30] E: 1.25 [0.67 to 2.32] F: 0.86 [0.48 to 1.54] G: 1.26 [0.80 to 1.98] H: 0.80 [0.41 to 1.56] I: 1.16 [0.70 to 1.93]

Pooled effect(random effects model): 1.03 [0.90 to 1.19] favoring single gloves Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

|

Authors’ conclusions Wearing two pairs of latex surgical gloves is associated with significantly fewer inner glove perforations.

There does not appear to be an increase in the number of outer glove perforations when two pairs of gloves are worn.

Risk of bias Random sequence generation A, E, J: Definitely yes C, D, F, G, I: Unclear B, H: Definitely no

Concealment of allocation E, C, I: Definitely yes A, B, D, F, G, H, J: Unclear

Blinding of participants A - J: Definitely no

Blinding of outcome assessor F: Definitely yes A, C, I, J: Unclear B, D, E, G, H: Definitely no

Missing data infrequent A, B: Definitely yes C, D, E, F, G, I, J: Unclear H: Definitely no

Free of selective reporting A - J: Definitely yes

Other bias – free of CoI A, B, D, E, F, G, H, I, J: Unclear C: Probably no

|

|

Mischke, 2014 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to September 2013

Studies2 A: Doyle, 1992 B: Gani, 1990 C: Jensen, 1997 D: Kovavisarach, 1998 E: Kovavisarach, 1999 F: Kovavisarach, 2002 G: Punyatanasakchai, 2004 H: Rudiman, 1999 I: Thomas, 2001 J: Wilson, 1996

Study design RCT

Setting Hospital

Country A: United Kingdom B: Australia C: China D: Thailand E: Thailand F: Thailand G: Thailand H: Indonesia I: India J: Oman

Source of funding and conflicts of interest SR: No conflicts of interest A: Not reported B: Not reported C: Gloves provided by manufacturer; conflicts of interest not reported D: Not reported E: Not reported F: Not reported G: Not reported H: Full text not available I: Not reported J: Not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR 1) Randomized controlled trial, irrespective of language, publication status or blinding 2) Study includes healthcare workers (at least 75% of study population) 3) Study compares the number of glove layers and/or special gloves 4) Study describes at least needlestick injury, sharps injury, blood stains inside the gloves or on the skin, glove perforations or dexterity as an outcome

34 studies included by the authors, 19 of which compared single and double standard sterile surgical latex gloves. Of those, 9 were excluded from the meta-analysis to answer the search question: - indicator inner glove as intervention (n=6) - vinyl inner glove as intervention (n=1) - orthopedic glove as comparator (n=1) - type of glove not reported (n=1)

N glove pairs A: 226 B: 1,317 C: 300 D: 1,029 E: 450 F: 252 G: 450 H: 180 I: 198 J: 384

Type of surgery A: Obstetrics and gynecology B: General C: Abdominal D: Obstetrics and gynecology E: Obstetrics and gynecology F: Obstetrics and gynecology G: Obstetrics and gynecology H: General I: General J: Multiple specialties

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported |

Intervention Double standard surgical latex glove |

Control Single standard surgical latex glove |

Endpoint of follow-up End of surgical procedure

For how many glove pairs were no complete outcome data available? (n/N) A: 3/150 B: 15/233 C: Not reported D: Not reported E: Not reported F: Not reported G: Not reported H: 12/72 I: Not reported J: Not reported

|

Inner glove pair perforations

Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: A: 0.11 [0.03 to 0.34] B: 0.26 [0.17 to 0.40] C: 0.30 [0.17 to 0.54] D: 0.41 [0.24 to 0.68] E: 0.19 [0.06 to 0.63] F: 0.27 [0.11 to 0.68] G: 0.26 [0.12 to 0.58] H: 0.20 [0.06 to 0.66] I: 0.53 [0.27 to 1.04] J: 0.17 [0.07 to 0.40]

Pooled effect(random effects model): 0.28 [0.22 to 0.36] favoring double gloves Heterogeneity (I2): 12%

Outer glove pair perforations

Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: A: 0.75 [0.46 to 1.23] B: 1.05[0.81 to 1.36] C: 1.18 [0.86 to 1.61] D: 0.88 [0.59 to 1.30] E: 1.25 [0.67 to 2.32] F: 0.86 [0.48 to 1.54] G: 1.26 [0.80 to 1.98] H: 0.80 [0.41 to 1.56] I: 1.16 [0.70 to 1.93]

Pooled effect(random effects model): 1.03 [0.90 to 1.19] favoring single gloves Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

|

Authors’ conclusions There is moderate- quality evidence that double gloving compared to single gloving during surgery reduces perforations, indicating a decrease in percutaneous exposure incidents.

There was moderate- quality evidence that double gloves have a similar number of outer glove perforations as single gloves, indicating that there is no loss of dexterity with double gloves.

Risk of bias Random sequence generation A, E, J: Definitely yes C, D, F, G, I: Unclear B, H: Definitely no

Concealment of allocation E, C, I: Definitely yes A, B, D, F, G, H, J: Unclear

Blinding of participants A - J: Definitely no

Blinding of outcome assessor F: Definitely yes A, C, I, J: Unclear B, D, E, G, H: Definitely no

Missing data infrequent A, B: Definitely yes C, D, E, F, G, I, J: Unclear H: Definitely no

Free of selective reporting A - J: Definitely yes

Other bias – free of CoI A, B, D, E, F, G, H, I, J: Unclear C: Probably no

|

|

Zhang, 2021 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to March 2020

Studies1 A: Guo, 2012 B: Kovavisarach, 1998 C: Kovavisarach, 1999 D: Kovavisarach, 2002 E: Makama, 2016 F: Punyatanasakchai, 2004 G: Thomas, 2001

Study design RCT

Setting Hospital

Country A: France B: Thailand C: Thailand D: Thailand E: Nigeria F: Thailand G: India

Source of funding and conflicts of interest SR: No financial support; no conflicts of interest A: Funding by Hongkong Polytech University B: Not reported C: Not reported D: Not reported E: No funding; no conflicts of interest F: Not reported G: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria SR 1) Randomized controlled trial 2) Study includes surgical patients in the operating room (not surgical patients in clinical treating room or animals) 3) Study compares double gloving with single gloving (not indicator gloving system, special gloves or changing of gloves) 4) Study describes glove perforations as an outcome 5) Study is published in English

N glove pairs A: 324 B: 1,029 C: 450 D: 252 E: 768 F: 450 G: 198

Type of surgery A: Multiple specialties (no orthopedics) B: Obstetrics and gynecology C: Obstetrics and gynecology D: Obstetrics and gynecology E: Multiple specialties (no orthopedics) F: Obstetrics and gynecology G: General

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported |

Intervention Double standard surgical latex glove |

Control Single standard surgical latex glove |

Endpoint of follow-up End of surgical procedure

For how many glove pairs were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: Not reported B: not reported C: Not reported D: Not reported E: Not reported F: Not reported G: Not reported

|

Inner glove pair perforations

Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: A: 0.05 [0.00 to 0.85] B: 0.41 [0.24 to 0.68] C: 0.19 [0.06 to 0.63] D: 0.27 [0.11 to 0.68] E: 0.08 [0.03 to 0.17] F: 0.26 [0.12 to 0.58] G: 0.53 [0.27 to 1.04]

Pooled effect(random effects model): 0.24 [0.13 to 0.43] favoring double gloves Heterogeneity (I2): 67%

Outer glove pair perforations

Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: A: 1.27 [0.57 to 2.81] B: 0.88 [0.59 to 1.30] C: 1.25 [0.67 to 2.32] D: 0.86 [0.48 to 1.54] E: 1.81 [1.46 to 2.24] F: 1.26 [0.80 to 1.98] G: 1.16 [0.70 to 1.93]

Pooled effect(random effects model): 1.21 [0.93 to 1.59] favoring single gloves Heterogeneity (I2): 59%

|

Authors’ conclusions Findings of this systematic review indicate that double gloving could reduce the rate of surgical glove perforation.

Risk of bias Random sequence generation A, C: Definitely yes B, D, E, F, G: Unclear

Concealment of allocation C, G: Definitely yes A, B, D, E, F: Unclear

Blinding of participants A - G: Definitely no

Blinding of outcome assessor D: Definitely yes E, G: Unclear A, B, C, F: Definitely no

Missing data infrequent A - G: Unclear

Free of selective reporting A - G: Definitely yes

Other bias – free of CoI A - G: Unclear |

1 Ten of 31 studies were included in the meta-analysis to answer the search question of this module.

2 Ten of 34 studies were included in the meta-analysis to answer the search question of this module.

Exclusie-tabel

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

AIDS/TB Committee of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Management of healthcare workers infected with hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus, or other bloodborne pathogens. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1997 May;18(5):349-63. PMID: 9154481. |

No detailed search strategy No risk of bias assessment Individual study results not available |

|

Al Maqbali MA. Using double gloves in surgical procedures: a literature review. Br J Nurs. 2014 Nov 27-Dec 10;23(21):1116-22. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2014.23.21.1116. PMID: 25426524. |

Includes non-randomized studies No risk of bias assessment |

|

Baldock TE, Bolam SM, Gao R, Zhu MF, Rosenfeldt MPJ, Young SW, Munro JT, Monk AP. Infection prevention measures for orthopaedic departments during the COVID-2019 pandemic: a review of current evidence. Bone Jt Open. 2020 Oct 27;1(4):74-79. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.14.BJO-2020-0018.R1. PMID: 33215110; PMCID: PMC7659659. |

Out of scope Double gloving to increase safety during doffing personal protective equipment |

|

Banaee S, Que Hee SS. Glove permeation of chemicals: The state of the art of current practice-Part 2. Research emphases on high boiling point compounds and simulating the donned glove environment. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2020 Apr;17(4):135-164. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2020.1721509. Epub 2020 Mar 25. PMID: 32209007; PMCID: PMC7960877. |

Simulation study O does not meet PICO O = glove permeation |

|

Barr SP, Topps AR, Barnes NL, Henderson J, Hignett S, Teasdale RL, McKenna A, Harvey JR, Kirwan CC; Northwest Breast Surgical Research Collaborative. Infection prevention in breast implant surgery - A review of the surgical evidence, guidelines and a checklist. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016 May;42(5):591-603. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.02.240. Epub 2016 Feb 27. PMID: 27005885. |

No risk of bias assessment Individual study results not available Includes same studies as Tanner (2009)

|

|

Battersby CL, Battersby NJ, Hollyman M, Hunt JA. Double-Gloving Impairs the Quality of Surgical Knot Tying: A Randomised Controlled Trial. World J Surg. 2016 Nov;40(11):2598-2602. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3577-z. PMID: 27230397. |

O does not meet PICO

O = quality of surgical knot tying |

|

Berridge DC, Starky G, Jones NA, Chamberlain J. A randomized controlled trial of double-versus single-gloving in vascular surgery. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1998 Feb;43(1):9-10. PMID: 9560497. |

Included in Tanner (2009) and Mischke (2014) |

|

Bosch-Amate X, Morgado-Carrasco D, Riera-Monroig J, Ferrando J. What Should We Use? Recommendations on Appropriate Gloves for Dermatologic Surgery. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2019 Mar;110(2):160-161. English, Spanish. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2017.12.018. Epub 2018 Jun 29. PMID: 30853066. |

I does not meet PICO C does not meet PICO I = sterile gloves C = non-sterile gloves |

|

Childs T. Use of double gloving to reduce surgical personnel's risk of exposure to bloodborne pathogens: an integrative review. AORN J. 2013 Dec;98(6):585-596.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2013.10.004. PMID: 24266931. |

Includes non-randomized studies

|

|

Ding BTK, Soh T, Tan BY, Oh JY, Mohd Fadhil MFB, Rasappan K, Lee KT. Operating in a Pandemic: Lessons and Strategies from an Orthopaedic Unit at the Epicenter of COVID-19 in Singapore. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020 Jul 1;102(13):e67. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.00568. PMID: 32618915; PMCID: PMC7396219. |

Out of scope Double gloving to increase safety during doffing personal protective equipment |

|

Doyle PM, Alvi S, Johanson R. The effectiveness of double-gloving in obstetrics and gynaecology. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992 Jan;99(1):83-4. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb14402.x. PMID: 1547183. |

Included in Tanner (2009) and Mischke (2014) |

|

Elgafy H, Raberding CJ, Mooney ML, Andrews KA, Duggan JM. Analysis of a ten step protocol to decrease postoperative spinal wound infections. World J Orthop. 2018 Nov 18;9(11):271-284. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v9.i11.271. PMID: 30479974; PMCID: PMC6242729. |

Out of scope Double gloving with glove change to prevent contamination of implants with patient’s skin flora |

|

Guo YP, Wong PM, Li Y, Or PP. Is double-gloving really protective? A comparison between the glove perforation rate among perioperative nurses with single and double gloves during surgery. Am J Surg. 2012 Aug;204(2):210-5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.08.017. Epub 2012 Feb 17. PMID: 22342011. |

Included in Zhang (2021) |

|

Hardison SA, Pyon G, Le A, Wan W, Coelho DH. The Effects of Double Gloving on Microsurgical Skills. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Sep;157(3):419-423. doi: 10.1177/0194599817704377. Epub 2017 May 2. PMID: 28462609. |

Simulation study O does not meet PICO

O = performance of microsurgical task |

|

Lammers MJW, Lea J, Westerberg BD. Guidance for otolaryngology health care workers performing aerosol generating medical procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 Jun 3;49(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s40463-020-00429-2. PMID: 32493489; PMCID: PMC7269420. |

Out of scope Double gloving to increase safety during doffing personal protective equipment |

|

Lee SY. What Role Does a Colored Under Glove Have in Detecting Glove Perforation in Foot and Ankle Procedures? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2022 Dec 1;480(12):2327-2334. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000002268. Epub 2022 Jun 2. PMID: 35695671; PMCID: PMC9653181. |

C does not meet PICO C = colored indicator underglove |

|

Louis SS, Steinberg EL, Gruen OA, Bartlett CS, Helfet DL. Outer gloves in orthopaedic procedures: a polyester/stainless steel wire weave glove liner compared with latex. J Orthop Trauma. 1998 Feb;12(2):101-5. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199802000-00006. PMID: 9503298. |

C does not meet PICO C = polyester/stainless steel wire weave outer glove (PSSWWG) with latex inner glove

|

|

Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control. 1999 Apr;27(2):97-132; quiz 133-4; discussion 96. PMID: 10196487. |

Expired guideline No detailed search strategy No risk of bias assessment Individual study results not available |

|

McHugh SM, Corrigan MA, Hill AD, Humphreys H. Surgical attire, practices and their perception in the prevention of surgical site infection. Surgeon. 2014 Feb;12(1):47-52. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2013.10.006. Epub 2013 Nov 20. PMID: 24268928. |

Includes non-randomized studies No risk of bias assessment Individual study results not available |

|

Marín-Bertolín S, González-Martínez R, Giménez CN, Marquina Vila P, Amorrortu-Velayos J. Does double gloving protect surgical staff from skin contamination during plastic surgery? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997 Apr;99(4):956-60. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199704000-00003. PMID: 9091940. |

Included in Tanner (2009) and Mischke (2014) |

|

Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Intraoperative transmission of blood-borne disease in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 1998 Mar;4(2):75-8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.1998.00164.x. PMID: 9873841. |

No detailed search strategy No risk of bias assessment Individual study results not available |

|

Sarmey N, Kshettry VR, Shriver MF, Habboub G, Machado AG, Weil RJ. Evidence-based interventions to reduce shunt infections: a systematic review. Childs Nerv Syst. 2015 Apr;31(4):541-9. doi: 10.1007/s00381-015-2637-2. Epub 2015 Feb 17. PMID: 25686893. |

Out of scope Double gloving with glove change to prevent contamination of shunt with patient’s skin flora |

|

Tanner J, Parkinson H. Surgical glove practice: the evidence. J Perioper Pract. 2007 May;17(5):216-8, 220-2, 224-5. doi: 10.1177/175045890701700504. PMID: 17542391. |

Duplicate (report of findings of first update Cochrane review (Tanner, 2006)) |

|

Walek KW, Rajski M, Sastry RA, Mermel LA. Reducing ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection with intraoperative glove removal. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2023 Feb;44(2):234-237. doi: 10.1017/ice.2022.70. Epub 2022 Apr 19. PMID: 35438070; PMCID: PMC9929712. |

Out of scope Double gloving with glove change to prevent contamination of shunt with patient’s skin flora |

|

Watt AM, Patkin M, Sinnott MJ, Black RJ, Maddern GJ. Scalpel safety in the operative setting: a systematic review. Surgery. 2010 Jan;147(1):98-106. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.08.001. Epub 2009 Oct 13. PMID: 19828169. |

I does not meet PICO C does not meet PICO I = cut-resistant gloves C = glove liners |

|

Watters DA. Surgery, surgical pathology and HIV infection: lessons learned in Zambia. P N G Med J. 1994 Mar;37(1):29-39. PMID: 7863725. |

Narrative review/case report No detailed search strategy No risk of bias assessment Individual study results not available |

|

Webb JM, Pentlow BD. Double gloving and surgical technique. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1993 Jul;75(4):291-2. PMID: 8379636; PMCID: PMC2497939. |

Simulation study O does not meet PICO O = tactile discrimination; dexterity |

|

Yang L, Mullan B. Reducing needle stick injuries in healthcare occupations: an integrative review of the literature. ISRN Nurs. 2011;2011:315432. doi: 10.5402/2011/315432. Epub 2011 Mar 31. PMID: 22007320; PMCID: PMC3169876. |

Includes non-randomized studies Individual study results not available |

Funnelplots

Funnelplot for studies included for the outcome inner glove pair perforation

Funnelplot for studies included for the outcome outer glove pair perforation

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 01-07-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 19-09-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd door het ministerie van VWS. De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep samengesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij het toedienen van medicatie.

De werkgroep bestaat uit:

- Dr. D.A.A. Lamprou, vaatchirurg, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde (NVvH), voorzitter (tot maart 2023)

- Drs. M.C. Gordinou de Gouberville, chirurg, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde (NVvH), voorzitter (vanaf maart 2023)

- Dr. F. Daams, chirurg, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde (NVvH)

- Prof. Dr. M.H.J. Verhofstad, chirurg, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde (NVvH)

- Drs. D. Kadouch, dermatoloog, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Dermatologie en Venereologie (NVDV) (tot november 2022)

- Dr. S. van der Geer-Rutten, dermatoloog, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Dermatologie en Venereologie (NVDV) (vanaf januari 2023)

- Ir. R. Wientjes, klinisch fysicus, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Klinische Fysica (NVKF)

- Dr. I.J.B. Spijkerman, arts-microbioloog, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Medische Microbiologie (NVMM)

- Drs. S.P.M. Dumont-Lutgens, arts-microbioloog, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Medische Microbiologie (NVMM)

- Dr. E.S. Veltman, orthopedisch chirurg, Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging (NOV)

- Dr. P. Segers, cardiothoracaal chirurg, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Thoraxchirurgie (NVT)

- Drs. S. Bons, anesthesioloog, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Anesthesiologie (NVA)

- A. Kranenburg, deskundige infectiepreventie, Vereniging voor Hygiëne & Infectiepreventie in de Gezondheidszorg (VHIG)

- D.A. Oosterom, deskundige infectiepreventie, Vereniging voor Hygiëne & Infectiepreventie in de Gezondheidszorg (VHIG)

- A. van Wandelen, stafmedewerker kwaliteit en beleid OK/CSDA, Verpleegkundigen & Verzorgenden Nederland (V&VN) (tot maart 2023)

- N.H.B.C. Dreessen, afdelingshoofd OK, Landelijke Vereniging Operatieassistenten (LVO)

- J. Jaspers-Spits, arbeidshygiënist, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Arbeidshygiëne (NVvA)

Met ondersteuning van:

- I. van Dusseldorp, literatuurspecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. A.E. Sussenbach, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Bc. A. Eikelenboom, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Dr. D.A.A. Lamprou |

Vaatchirurg |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Drs. M.C. Gordinou de Gouberville |

Chirurg, ChiCoN (WZA en Treant) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Dr. F. Daams |

Chirurg, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Prof. Dr. M.H.J. Verhofstad |

- Chirurg, Erasmus MC - Bestuurslid diverse wetenschappelijke verenigingen - Voorzitter Richtlijncommissie |

Onafhankelijk deskundige voor gezondheidsschade in civielrechtelijk verband |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Drs. D. Kadouch |

Dermatoloog, Centrum Oosterwal |

Oprichter Tenue de Soleil |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Dr. S. van der Geer-Rutten |

Dermatoloog, MohsA huidcentrum |

Bestuurder, MohsA Huidcentrum |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Ir. R. Wientjes |

Klinisch fysicus |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Dr. I.J.B. Spijkerman |

Arts-microbioloog, met aandachtsgebied infectiepreventie, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Drs. S.P.M. Dumont-Lutgens |

Arts-microbioloog, Jeroen Bosch ziekenhuis |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Dr. E.S. Veltman |

Orthopedisch chirurg, Erasmus MC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Dr. P. Segers |

Cardiothoracaal chirurg |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

S. Bons |

Anesthesioloog |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

A. Kranenburg |

Deskundige infectiepreventie, Rijnstate Ziekenhuis Arnhem |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

D.A. Oosterom |

Deskundige infectiepreventie, Haaglanden Medisch Centrum |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

A. van Wandelen |

Stafmedewerker kwaliteit en beleid OK/CSDA, UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

N.H.B.C. Dreessen |

Teamleider OK, Medisch Centrum Zuyderland |

Voorzitter LVO |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

J. Jaspers-Spitz |

Arbeidshygiënist, Maastricht UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door uitnodigen van Patiëntfederatie Nederland (PFNL) voor de knelpunteninventarisatie. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan PFNL en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Dubbele chirurgische handschoenen |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg m.b.t. infectiepreventie op het OK-complex. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijn op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door NVZ, NGG (NOG), VCCN, NOV, SVN, NVMM, VHIG, VDSMH, NVKF, BRV, NVT, THI-werkgroep, NVA en NVAB via de knelpunteninventarisatie. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (zie www.gradeworkinggroup.org). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

· Er is hoge zekerheid dat het ware effect van behandeling dicht bij het geschatte effect van behandeling ligt; · Het is zeer onwaarschijnlijk dat de literatuurconclusie klinisch relevant verandert wanneer er resultaten van nieuw grootschalig onderzoek aan de literatuuranalyse worden toegevoegd. |

|

Redelijk |

· Er is redelijke zekerheid dat het ware effect van behandeling dicht bij het geschatte effect van behandeling ligt; · Het is mogelijk dat de conclusie klinisch relevant verandert wanneer er resultaten van nieuw grootschalig onderzoek aan de literatuuranalyse worden toegevoegd. |

|

Laag |

· Er is lage zekerheid dat het ware effect van behandeling dicht bij het geschatte effect van behandeling ligt; · Er is een reële kans dat de conclusie klinisch relevant verandert wanneer er resultaten van nieuw grootschalig onderzoek aan de literatuuranalyse worden toegevoegd. |

|

Zeer laag |

· Er is zeer lage zekerheid dat het ware effect van behandeling dicht bij het geschatte effect van behandeling ligt; · De literatuurconclusie is zeer onzeker. |

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |