Immunotherapie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van immunotherapie in de behandeling van kinderen met een IgE-gemedieerde koemelkallergie?

Aanbeveling

Momenteel is immunotherapie onvoldoende bewezen en geeft risico’s op allergische reacties. Geef het daarom niet als behandeling voor IgE-gemedieerde koemelkallergie. Als patiënten en hun ouders dit graag willen, ga dan als behandelaar na of immunotherapie in studieverband wordt gegeven in Nederland en overleg/verwijs naar het studiecentrum.

Pas geen melkladder toe; dit is een instrument voor niet-IgE-gemedieerde koemelkallergie en valt dus buiten deze richtlijn.

Bied wel een provocatie met baked milk aan bij kinderen met een bewezen IgE-gemedieerde koemelkallergie (zie de aanbevelingen in de module Baked Milk); dit biedt een mogelijkheid voor de uitbreiding van het dieet, maar is los te zien van immunotherapie.

Overwegingen

Er zijn 11 studies gevonden in een systematisch literatuuronderzoek naar de effectiviteit van immunotherapie in de behandeling van kinderen met IgE-gemedieerde koemelkallergie. Zeven studies vergeleken immunotherapie met een placebo- of controlegroep. Vier studies vergeleken twee vormen van immunotherapie. Deze twee groepen zijn los beoordeeld.

Immunotherapie vergeleken met placebo of controlegroep

Alle studies beschreven tolerantie, waarbij de meeste een klinisch relevant verschil vonden in het voordeel van immunotherapie. Logischerwijs werden er wel meer reacties gevonden in de immunotherapiegroep ten opzichte van de placebo of controlegroep. Ook was er bij de immunotherapie vaker de noodzaak voor adrenaline, maar het stoppen met de immunotherapie leek niet vaak noodzakelijk. De kwaliteit van het bewijs is echter laag (door methodologische beperkingen en onnauwkeurigheid); dit betekent dat we onzeker zijn over het gevonden effect.

Vergelijking tussen twee vormen van immunotherapie

Vier studies vergeleken twee verschillende vormen van immunotherapie. Vanwege het verschil in interventies en de definitie van de uitkomstmaten konden deze resultaten niet samen worden genomen. Zie de resultatensectie voor details. De overall kwaliteit van bewijs is zeer laag (door methodologische beperkingen, onnauwkeurigheid en verschillen in uitkomstmaten en interventies tussen studies); dit betekent dat we zeer onzeker zijn over het gevonden effect.

Balans tussen gewenste en ongewenste effecten

Op basis van de gevonden resultaten (Klok, 2023) denkt de werkgroep dat immunotherapie veelbelovend is. Ook bij andere voedselallergieën lijkt immunotherapie effectief (Vickery, 2017; Jones, 2022). Momenteel wordt immunotherapie niet gegeven in Nederland aan kinderen met IgE-gemedieerde koemelkallergie, maar er loopt wel een studie waarin de effecten van immunotherapie worden uitgezocht. De eerste resultaten hiervan zijn nog niet gepubliceerd, maar worden op korte termijn verwacht (zie ook ClinicalTrialRegister).

In de gevonden studies worden verschillende manieren van immunotherapie vergeleken. Er is geen vast protocol hoe immunotherapie gegeven moet worden. Dit kan met “gewone” koemelk, maar ook met baked milk of andere vormen van melk. De Nederlandse melkladder (DAVO, 2019) is geschikt voor het introduceren van melk bij een niet-IgE-gemedieerde koemelkallergie, maar kan niet gebruikt worden voor het geven van immunotherapie bij een IgE-gemedieerde koemelkallergie.

Over de kwaliteit van leven werden geen duidelijke resultaten gevonden, zeker niet op de lange termijn. De verwachting is wel dat die toeneemt bij het kunnen uitbreiden van het dieet en geen angst meer te hebben voor een allergische reactie.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun naasten/verzorgers)

In de praktijk wordt gezien dat ouders en kinderen graag immunotherapie willen. Dit komt omdat immunotherapie de kans vergroot dat je over je allergie heen komt, en dit proces ook versnelt. Helaas is in Nederland immunotherapie voor IgE-gemedieerde koemelkallergie nog geen standaard zorg. Er loopt ten tijde van schrijven (februari 2025) een multicenterstudie in Nederland (Deventer), waarbij kinderen tot 30 maanden gerandomiseerd worden in een immunotherapie en een controlegroep.

Indien de wens tot immunotherapie zeer sterk speelt bij ouders en kinderen, kan de behandelaar bekijken of er studies lopen waar de patiënt voor in aanmerking zou komen. Immunotherapie is echter wel belastend: zoals deze in de studies wordt gegeven, betreft het minimaal 2 dagopnames in het ziekenhuis waarbij een provocatie met koemelk plaatsvindt. Afhankelijk van de tolerantie van het kind bij de eerste provocatie, wordt een behandelschema met thuisexpositie uitgezet, en wordt langzaam opgehoogd. Er zijn meerdere bezoeken nodig aan het ziekenhuis om de maintenance dose te bereiken.

Kostenaspecten

Aan immunotherapie zijn kosten verbonden omdat het kort maar intensief is. Elke dosisophoging van expositie aan het allergeen moet plaatsvinden in het ziekenhuis met een provocatietest, waarvoor een dagopname nodig is. Ziekenhuizen zullen dus meer tijd in moeten plannen voor provocaties, er moet 24-uurs monitoring beschikbaar zijn (telefonische bereikbaarheid van een assistent), en er is meer uitvoerend en supervisiepersoneel nodig. Dit is een korte termijn kostenintensivering. Dit zal echter naar verwachting op de lange termijn niet tot een verschil in kosten leiden, omdat bij het succesvol doorlopen van de immunotherapie kosten worden bespaard: SEH-bezoek bij anafylaxie, polibezoeken van oudere kinderen, receptuur antihistamine en adrenaline en vermindering van ziekteverzuim. Op maatschappelijk niveau worden belastinginkomsten verhoogd, omdat de aftrekbare post voor dieetkosten zal vervallen bij succesvolle immunotherapie.

Gelijkheid (health equity)

Immunotherapie wordt alleen nog in studieverband in Nederland uitgevoerd. Hierdoor is de toegankelijkheid nu beperkt. Als in de toekomst op basis van wetenschappelijke uitkomsten (van de Nederlandse studie of studies in het buitenland) wordt besloten dat immunotherapie in Nederland aangeboden gaat worden, zal het afhankelijk zijn van de precieze protocollen, werkwijzen en beschikbare centra hoe dit de toegankelijkheid van de zorg beïnvloedt.

Aanvaardbaarheid:

Ethische aanvaardbaarheid

Bij immunotherapie spelen ethische overwegingen een rol. Enerzijds het goed doen, omdat je een kind van zijn allergie wil afhelpen: dit kan de kwaliteit van leven verhogen omdat er geen dieetbeperking is, en je kan op latere leeftijd allergische reacties voorkomen of verminderen. Anderzijds speelt het principe van niet schaden: wat is aanvaardbaar qua allergische reacties die optreden bij immunotherapie, die het kind anders niet zou krijgen bij het vermijden van koemelk?

Duurzaamheid

Duurzaamheidsoverwegingen spelen niet primair een rol in de keuze voor het geven van immunotherapie voor IgE-gemedieerde koemelkallergie.

Haalbaarheid

Het duurt nog even voordat de Nederlandse studieresultaten over immunotherapie beschikbaar komen (zie ook ClinicalTrialRegister). Mogelijk over een paar jaar, als de resultaten positief blijken, kan immunotherapie breder in Nederland worden aangeboden. Er moet dan goed landelijk worden gekeken hoe immunotherapie veilig geïmplementeerd kan worden, en welke centra dat gaan uitvoeren. De komende paar jaar zal er een richtlijn of protocol moeten komen voor orale immunotherapie (OIT) bij voedselallergie bij jonge kinderen in het algemeen. OIT zal dan eerst voor pinda- en notenallergie ingevoerd worden, omdat internationaal de bewijskracht al verder is, en daarna pas voor andere allergieën zoals koemelkallergie.

Het zal inspanning en tijd vergen van centra om deze behandeling in goede banen te leiden. Het aanbieden van immunotherapie zal leiden tot een andere organisatie van zorg:

- Er zullen meer dagdelen en bedden beschikbaar moeten komen om de toename aan provocaties uit te voeren

- Er moet een 24-uurs telefonische bereikbaarheid van een assistent worden georganiseerd voor eventuele vragen en reacties die optreden;

- Er zijn meer provocatiematerialen nodig;

- Er is meer uitvoerend personeel en supervisiepersoneel voor de provocaties nodig.

Dit is een grote verandering ten opzichte van de huidige zorg. Momenteel krijgen kinderen een provocatie, waarmee de diagnose wordt gesteld. Vervolgens worden ze vervolgd tot ze 18 jaar zijn en worden er in deze periode regelmatig provocatietesten uitgevoerd. Bij het aanbieden van immunotherapie zal een verschuiving plaatsvinden naar het intensiever behandelen van jongere kinderen, waarbij minder zorg en medicatie nodig zal zijn voor tieners en volwassenen; dit effect is echter pas in de verdere toekomst te observeren.

Precieze protocollen en werkwijzen zullen moeten worden uitgewerkt, waarbij moet worden nagedacht over het volgende:

- Welke centra zullen immunotherapie voor voedselallergieën gaan aanbieden, en is het wenselijk voor een centrum om de zorg te verschuiven? De werkgroep is van mening dat OIT alleen in gespecialiseerde centra kan.

- Is het wenselijk om ook aan oudere kinderen immunotherapie aan te bieden? Uit een review blijkt dat de effecten van immunotherapie bij kinderen <3 jaar gunstig zijn, omdat het immuunsysteem dan nog goed veranderbaar is. Bij oudere kinderen lijkt dit minder het geval (Barten, 2023). Een provocatie met baked milk kan wel al in Nederland worden aangeboden, om te kijken of uitbreiding van het dieet mogelijk is, en mogelijk kan bijdragen aan tolerantieontwikkeling, ook voor oudere kinderen (zie de module Baked Milk).

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Momenteel is er nog geen behandeling voor IgE-gemedieerde koemelkallergie. Melkladders zijn instrumenten voor niet-IgE gemedieerde koemelkallergie, en vallen dus buiten deze richtlijn. De gevonden studies over IgE-gemedieerde koemelkallergie zijn allemaal verschillend met betrekking tot interventie, controle en uitkomsten, en kunnen dus niet samen worden genomen. De werkgroep verwacht dat binnen enkele jaren immunotherapie een behandelingsmogelijkheid zal worden. De werkgroep is van mening dat dit in gespecialiseerde centra moet worden uitgevoerd, maar dat hiervoor nieuwe afspraken over capaciteit en kosten moeten worden gemaakt. Afhankelijk van de studieresultaten moeten precieze protocollen en werkwijzen worden uitgewerkt.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

The current treatment methods for IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy primarily involve avoiding cow's milk and cow's milk products. This can be challenging and may impact the quality of life of the child and their family. Immunotherapy offers a new approach that could potentially provide benefits such as promoting long-term tolerance, reducing the frequency and severity of allergic reactions, cost savings, and improving quality of life. Understanding and exploring the role of immunotherapy is therefore of critical importance.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Comparison 1: Immunotherapy compared to placebo or control group

|

Outcome |

Study results and measurements |

Absolute effect estimates |

Certainty of the evidence (Quality of evidence) |

Conclusions |

|

|

Immunotherapy |

Control or placebo |

||||

|

Tolerance (crucial) |

Defined differently by authors.

RRs varying from 1.22 to 23.00, all in favour of immunotherapy

Based on data from 300 participants in 7 studies |

Data could not be pooled due to heterogeneity in outcome, intervention and control. See results section for details. |

Low Due to serious risk of bias, due to serious imprecision1 |

Immunotherapy may result in an increase of tolerance when compared with placebo or control in children with cow’s milk allergy.

(Dantzer, 2022; Maeda, 2021; Martorell, 2011; Pajno, 2010; Petroni, 2024; Salmivesi, 2013; Skripak, 2008) |

|

|

Mild IgE-Symptoms (important) |

Based on data from 7 studies |

Symptoms were reported in different ways by different studies. Therefore, data was not pooled. See results section for details. |

Low Due to serious risk of bias, due to serious imprecision1 |

Immunotherapy may result in an increase of mild IgE-mediated reactions when compared with placebo or control in children with cow’s milk allergy.

(Dantzer, 2022; Maeda, 2021; Martorell, 2011; Pajno, 2010; Petroni, 2024; Salmivesi, 2013; Skripak, 2008) |

|

|

Adverse events (important) |

Defined as the need for epinephrine of discontinuation from OIT.

Based on data from 114 participants in 5 studies |

Data were not pooled. See result section for details. |

Very Low Due to serious risk of bias, due to serious imprecision2 |

Immunotherapy may result in an increase of adverse events when compared with placebo or control in children with cow’s milk allergy.

(Dantzer, 2022; Maeda, 2021; Pajno, 2010; Salmivesi, 2013; Skripak, 2008) |

|

|

Quality of life (important) |

- |

- |

No GRADE (no evidence was found) |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of immunotherapy on quality of life in children with cow’s milk allergy. |

|

- Risk of Bias: serious. Inadequate/lack of blinding of participants and personnel, resulting in potential for performance bias, Inadequate/lack of blinding of outcome assessors, resulting in potential for detection bias; Imprecision: serious. The confidence interval overlaps one boundary of clinical relevance.

- Risk of Bias: serious. Inadequate/lack of blinding of participants and personnel, resulting in potential for performance bias, Inadequate/lack of blinding of outcome assessors, resulting in potential for detection bias; Imprecision: serious. The confidence interval overlaps two boundaries of clinical relevance.

Comparison 2: Comparisons between two types of immunotherapy

|

Outcome

|

Study results and measurements |

Absolute effect estimates |

Certainty of the evidence (Quality of evidence) |

Conclusions |

|

|

Immunotherapy |

Other type of immunotherapy |

||||

|

Tolerance (crucial) |

Defined differently by authors.

Based on results from 174 participants in 4 studies. |

Different comparisons:

See results section for details. |

Very low Due to serious risk of bias, due to very serious imprecision, due to serious inconsistency 1 |

The evidence is very uncertain about a difference in effect of different immunotherapies on tolerance in children with cow’s milk allergy.

(Keet, 2012; Nagakura, 2021; Nowak, 2018; Ogura, 2020) |

|

|

Mild IgE-symptoms (important)

|

Based on results from 3 studies |

No large differences were observed. Data were not pooled due to difference in comparisons |

Very low Due to serious risk of bias, due to very serious imprecision, due to serious inconsistency1 |

The evidence is very uncertain about a difference in effect of different immunotherapies on mild IgE-reactions in children with cow’s milk allergy.

(Keet, 2012; Nagakura, 2021; Ogura, 2020) |

|

|

Adverse events (important) |

Defined as the need for epinephrine of discontinuation from OIT.

Based on results from 89 participants in 3 studies. |

No large differences were observed. Data were not pooled due to difference in comparisons. |

Very low Due to serious risk of bias, due to very serious imprecision, due to serious inconsistency1 |

The evidence is very uncertain about a difference in effect of different immunotherapies on adverse events in children with cow’s milk allergy.

(Keet, 2012; Nagakura, 2021; Ogura, 2020) |

|

|

Quality of life (important) |

- |

- |

No GRADE (no evidence was found) |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of immunotherapy on quality of life in children with cow’s milk allergy. |

|

- Risk of Bias: serious. Inadequate/lack of blinding of participants and personnel, resulting in potential for performance bias, Inadequate/lack of blinding of outcome assessors, resulting in potential for detection bias; due to high loss to follow-up; Imprecision: very serious. The confidence interval overlaps both boundaries of clinical relevance. Inconsistency: serious. Due to conflicting results.

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Eleven studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in table 2 and 3. The assessment of risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables (under the tab ‘Evidence tabellen’).

Comparison 1: Immunotherapy compared to placebo or control (table 2)

Six studies reported on oral immunotherapy (OIT) compared to placebo.

- With regard to the intervention: Five performed OIT with unheated cow’s milk as an intervention (Maeda, 2021; Martorell, 2011; Pajno, 2010; Salmivesi, 2013; Skripak, 2008) and one study used baked milk (Dantzer, 2022).

- With regard to the comparator: Four studies used placebo in the control group. This was either non-dairy milk (Paino, 2010; Salmivesi, 2024; Skripak, 2008) or tapioca (Dantzer, 2022). The other two studies used a control group that eliminated all cow’s milk (Maeda 2021, Pajno, 2010).

Another study compared three dosages of epicutaneous immunotherapy (CM patches) with a placebo control (Petroni, 2024).

Comparison 2: Comparisons between two types of immunotherapy (table 3)

Four studies compared two types of immunotherapy:

- Ogura (2020) compared OIT with high target dose to a low target dose.

- Nagakura (2021) compared OIT with heated milk to an OIT with unheated milk.

- Keet (2012) compared sublingual immunotherapy with sublingual immunotherapy followed by OIT.

- Nowak-Wegrzyn (2018) compared the introduction of more allergenic forms of milk in a faster (every 6 months) with a slower (every 12 months) fashion.

Follow-up ranged from 18 weeks (Paino, 2010) to 3 years (Nowak-Wegrzyn, 2018; Salmivesi, 2013).

In- and exclusion criteria of the studies are described in a table under the tab “evidence tabellen”.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies for Comparison 1: Immunotherapy compared to placebo or control

|

Study |

Participants |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison (C) |

Follow-up + outcome measures |

Comments |

Risk of bias * |

|

Dantzer, 2022

RCT |

N: 30 (children 3-18 years) I: 15 | C: 15

Age (median [range]) I: 13 [4 to 18] | C: 7 [3 to 14]

Sex (% male) I: 46% | C: 60%

Age at CMA diagnosis (median [range]): I: 8 [4 to 14] | C: 9 [4 to 14]

Tolerated dose of baked milk at screening ³144 mg (n, %): I: 6 (40%) | C: 10 (67%) |

Baked milk oral immunotherapy

|

Placebo (tapioca powder) immunotherapy (with same phases as baked milk OIT) |

12 months: Tolerance

IgE-mediated reactions

Quality of life |

Funding by charity organization. Authors declare no conflicts of interest. |

Low |

|

Maeda, 2021

RCT, Japan |

N: 28 I: 14| C: 14

Age (mean ± SD) I: 5.5 ± 2.4 | C: 5.4 ± 2.3

Sex (% male) I: 50 | C: 50

|

Oral immunotherapy (OIT) with monthly outpatients visits, and reduction in dose when symptoms appeared

Group 1: 2 week ‘rush OIT’ in hospital: start with 10-4 mL CM increased daily.

Group 2: ‘Slow OIT’ at home, daily CM ingestion, volume increased by 10-20% every 2weeks. |

Observation

Complete elimination of CM for 1 year |

12 months: Tolerance to DBPCFC (Sampson <2 at 100mL CM)

Adverse events |

Therapy was discontinued and the patient was regarded as a dropout if the ingest volume of undiluted cow's milk was <5 mL at this point. If the ingest volume was _5 mL, the patient was switched to slow OIT at home. |

Some concerns |

|

Martorell, 2011

RCT, Spain |

N: 60 I: 30 | C: 30

Age (median [range]) I: 26.5 [26 to 32.25] months C: 25.75 [24 to 35] months

Sex (% male) I: 50% | C: 63.3% |

Oral desensitization

|

Milk-free diet for 1 year |

12 months: Oral tolerance

Adverse reactions

|

Nothing is reported about funding and potential conflicts of interest.

Authors’ conclusion: Results of this study strongly suggest that the oral desensitization protocol could be indicated in allergic children from 2 years of age who have not yet achieved tolerance to CMP. |

Some concerns |

|

Pajno, 2010

RCT, Italy |

N: 30 I: 15 | C: 15

Age (median [range]) I: 9 [4 to 12] years | C: 10 [4 to 13] years

Sex (% male) I: 53.3% | C: 60%

Duration of CM allergy (mean ± SD) I: 6.9 ± 3.2 years | C: 7.4 ± 3.7 years

History of anaphylaxis (n) I: 2 | C: 1 |

Oral immunotherapy with CM

|

Oral immunotherapy with soy milk |

18 weeks: Tolerance

Adverse events |

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Nothing is reported about funding.

Authors’ conclusion: The weekly up-dosing desensitization protocol for CMA was effective and reasonably safe and induced consistent immunologic changes. |

Some concerns |

|

Salmivesi, 2013

Finland |

N: 28 I: 18 | C: 10

Age (median [range]) I: 10.1 [7 to 14] | C: 9.8 [7 to 13]

Sex (% male) I: 44| C: 40 |

Milk ladder (OIT) lasting 24 weeks, starting with 0.06 mg milk protein increasing to 6400 mg. First 9 doses in clinic, others at home. |

Soy, oat or rice milk depending on allergy status. |

3 years: Adverse events

|

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by two research foundations (allergy and pediatric) and a university research fund. No tolerance test is performed at the end of the trial. |

Some concerns |

|

Skripak, 2008

RCT 2 hospitals in the United States |

N: 20 I: 13 | C: 7

Age (mean ± SD) I: 9.3 ± 3.3 | C: 10.2 ± 3.3

Sex (% male) I: 62 | C: 57

Baseline CM IgE (median [range]) I: 34.8 [1.86 to 314] kUA/L C: 14.6 [0.93 to 133.4] KUA/L |

OIT with CM - Initial dosing in clinical research facility: starting with 0.4 mg mil protein, then doubling doses every 30 min to max 50mg. - When 12 mg was tolerated, participants continued home dosing - Home dosing: highest dose from facility 1 to 2 weeks, then increased dose at research facility. - When 500 mg was reached, 13 weeks continuation, then DBPCFC. |

OIT with placebo (soy or rice milk) |

23 weeks: Tolerance

Adverse events |

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

No commercial funding of the study. |

Low |

|

Petroni, 2024

RCT, USA and Canada |

N: 198 I: 145 (49/49/47)| C: 53

Age (mean) 8 years

Sex (% male) 62.6% |

Epicutaneous immunotherapy with Viaskin Milk doses 150mg, 300mg or 500mg

|

Placebo |

12 months Tolerance

Adverse events |

The study was funded by DBV technologies. The sponsor participated in the design and conduct of the study. Potential conflicts of interest are reported.

Authors’ conclusion: EPIT with Viaskin Milk may be a viable therapeutic treatment option for IgE-mediated CM allergy. |

Low |

Table 3. Characteristics of included studies for Comparison 2: Comparisons between two types of immunotherapy

|

Study |

Participants |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison (C) |

Follow-up + outcome measures |

Comments |

Risk of bias * |

|

Ogura, 2020

RCT, 9 hospital allergy units in Japan |

N: 26 (CM only) I: 13 | C: 13

Age (median [IQR]) 6.4 [6.0 to 7.7] 7.6 [6.1 to 10.4]

Sex (% male) I: 54 | C: 85

History of anaphylaxis (%) I: 69.2 | C: 38.5 |

OIT - target dose 3400 mg CM protein (100 mL unheated milk)

- build up phase (10 mg protein to start) –in 20 doses, min 125 days. - reduce ingestion at symptoms grade 2 or 3. - maintenance phase |

OIT - 25% target dose (25ML unheated milk)

- build up phase (10 mg protein to start) - maintenance phase |

1 and 2 years: Tolerance (OFC with total 3400 mg of milk after 2 weeks of ingestion cessation)

Symptoms

Adverse events |

|

Some concerns |

|

Nagakura, 2021

RCT, Japan |

N: 33 I: 17 | C: 16

Age (median [rangea]) I: 7.6 [5.2 to 11.2] C: 6.1 [5.3 to 10.8]

Sex (% male) I: 82.4 | C: 68.8

|

OIT heated milk - 5 d. hospitalization. - start with ½ DBPCFC threshold. Increased in 8 steps to 3 ML. (with loratadine 10 mg) - at home (12 months) - Increase to 3 mL if possible. - 1 month reaction free at 3Ml: loratadine was stopped. |

OIT unheated milk (see intervention)

|

12 months: Oral tolerance (3mL and 25 mL OIT with HM)

Symptoms (symptom severity, symptoms per ingestion) |

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No commercial funding received.

|

Low |

|

Keet, 2012

Open-label randomized study |

N: 30 I: 10 | C: 20

Age (median [range]) I: 8 [6 to 11] C: 8 [6 to 16]

Sex (% male) I: 40 | C: 70

History of anaphylaxis (n, %): I: 8 (80%) | C: 15 (75%) |

Sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT)

Then further increase dose |

Sublingual immunotherapy followed by OIT

Then further increase dose |

12 and 60 weeks: Tolerance of 8g milk protein

Systemic reactions |

One author has extensive relations with commercial organizations. Other authors no conflicts of interest. Study received non-commercial funding.

Authors’ conclusion: SLIT followed by OIT was much more effective at desensitization than SLIT alone but was accompanied by an increased risk of systemic side effects. |

Some concerns |

|

Nowak-Wegrzyn, 2018 |

N: 85 I: 41 | C: 44

Age (mean ± SD) Approx. 7.0 (±2.1)

Sex (% male) Approx. 70%

History of anaphylaxis (%): Approx. 37% |

Introduction of more allergenic forms of milk (MAFM, less heat-denatured) with dose escalation every 6 months

|

Introduction of MAFM with dose escalation every 12 months |

36 months: Tolerance to non-baked-liquid-milk

Adverse events |

Selection bias: Included only children who already tolerated baked milk at baseline.

Non-commercial funding received. No significant conflicts of interest reported. |

High |

|

Abbreviations: C = comparison; CM = cow’s milk; CMA = cow’s milk allergy; DBPCFC = double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge; I = intervention; MAFM = more allergenic forms of milk; OFC = oral food challenge; OIT = oral immunotherapy; SOTI = specific oral tolerance induction; SPT = skin prick test. *For further details, see risk of bias table in the appendix a Unclear whether IQR or range (min-max) is presented based on the original study. |

||||||

Results

Results are presented separately for studies that compared immunotherapy to a control group or placebo (comparison 1) and for studies that compared two types of immunotherapies (comparison 2).

Comparison 1: Immunotherapy compared to placebo or control

1. Tolerance

Authors defined tolerance differently:

- As ingestion of 4044 mg cumulative amount of baked milk protein without dose-limiting symptoms at 12 months (Dantzer, 2022)

- As Sampson symptoms <2 at 100mL CM (Maeda, 2021)

- As tolerating 200mL of CM (Martorell, 2011 and Pajno, 2010)

- As tolerating 6400 mg of CM protein (Salmivesi, 2013)

- No definition, but reporting the milk threshold steps in milligrams (Skripak, 2008). For the sake of this review, we used the individuals reaching a milk threshold of over 4140 mg as tolerant.

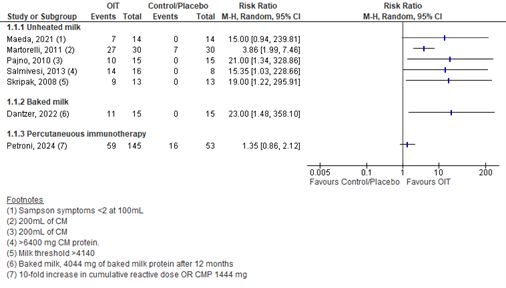

Results are presented in Figure 1. Results are not pooled due to differences in definition of tolerance, differences in interventions and studies with placebo or other control. In general, studies show a risk ratio in favor of the immunotherapy.

Figure 1. Tolerance in OIT vs placebo/control

2. Mild IgE-symptoms or reactions

All authors reported on (mild) IgE-symptoms, but very heterogeneously. See table 4.

Table 4. Mild reactions to OIT or control treatment in children with IgE-mediated CMA.

|

Study |

Reactions (in number of patients) |

Information |

|

|

OIT |

Control |

||

|

Maeda (2021) |

12 of 14 (86%) |

3 of 14 (21%) |

In the control group all 3 mild; in OIT group 2 mild (no intervention required), 8 moderate, 2 severe (requiring intervention with referral to specialist) |

|

Martorell (2011) |

24 of 30 (80%) |

0 of 30 (0%) |

14 children moderate reaction (47%), 10 mild reaction (33%). symptoms were controlled in each case by oral steroids, antihistamines and/or b2-agonists |

|

Pajno (2010) |

7 of 15 (47%) |

0 of 15 (0%) |

Reactions were mostly abdominal pain, throat pruritus, and gritty eyes. Most reactions were transient and required no treatment. |

|

Skripak (2008) |

Median frequency for total reactions in each participant |

most common types of reactions in the active group were local (mostly oral pruritus) and gastrointestinal (mostly abdominal pain) |

|

|

35% (range 1% to 95%) |

1% (range 0% to 53%) |

||

|

Salmivesi (2013) |

24 reactions in 16 children |

9 reactions in 8 children |

In the OIT group mostly intestinal and oral symptoms; in the control group mostly intestinal and dermal symptoms. |

|

Petroni, (2024) |

150mg: 39/49 (80%) 300mg: 39/49 (80%) 500mg: 37/47 (79%) |

27 of 53 (50.9%) |

Number of participants with at least 1 treatment-related adverse event |

|

Study |

Mild reactions (in number or % of doses) |

Information |

|

|

OIT |

Control |

||

|

Dantzer (2022) |

2222 of 5277 (42.1%) |

94 of 5132 (1.8%) |

Mostly oropharyngeal and gastrointestinal symptoms, nearly all mild. |

|

Martorell (2011) |

114 of 738 (15.4%) |

none |

The most common manifestations were urticaria-angioedema, followed by cough |

|

Skripak (2008) |

1107 of 2437 (45.4%) |

134 of 1193 (11.2%) |

most common types of reactions in the active group were local (mostly oral pruritus) and gastrointestinal (mostly abdominal pain) |

3. Adverse events (leading to epinephrine use or discontinuation of OIT)

Five studies reported on adverse events. The results on the use of epinephrine or discontinuation of OIT due to adverse events, are shown in table 5.

Table 5. Adverse events during OIT, leading to epinephrine use or discontinuation of OIT.

|

Author |

Use of epinephrine |

|

|

Intervention (OIT) |

Control |

|

|

Dantzer (2022) |

4/15 (27%) |

0/15(0%) |

|

Maeda (2021) |

|

Not reported |

|

Rush OIT |

1/14 patients (7%) 2/822 CM intake (0.2%)

|

|

|

Slow OIT |

6/12 patients (50%) 19/1409 CM intake (0.5%) |

|

|

Skripak (2008) |

4/13 (31%) |

0/13 (0%) |

|

|

Discontinuation |

|

|

Intervention (OIT) |

Control |

|

|

Pajno (2010) |

3/15 (20%) |

0/15 (0%) |

|

Salmivesi (2013) |

2/18 (11%) both because of abdominal complaints |

2/10 (20%) 1 because of lacking motivation, 1 accidental CM-induced anaphylaxis |

4. Quality of life

Dantzer (2022) is the only study to report on quality of life. They reported on the Food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaire (FAQOL)-Parent Form (PF) after 12 months. The FAQOL questionnaires contain 3 to 4 domains (food anxiety, social and dietary limitations, emotional impact, risk of accidental ingestion, allergen avoidance) and include 23 to 30 questions. Higher scores indicate worse food allergy quality of life. The FAQOL-PF was completed for all children younger than 18 years. Dantzer (2022) reports no significant difference in overall or domain-specific change between or within groups, except for a significant difference in categorical change (improved vs no change) between groups for the emotional impact domain (P= .036), with a higher proportion with improvement in the placebo group. No absolute numbers were reported.

Comparison 2: Comparisons between two types of immunotherapy

1. Tolerance

Again, authors defined tolerance differently:

- As being unreactive to an 8-g milk protein challenge (Keet, 2012)

- As being tolerant to non-baked-liquid milk (Nowak, 2018)

- As short-term unresponsiveness to 3400mg of milk protein (Ogura, 2020)

- As being tolerant to 3mL OFC and to 25mL OFC (Nagakura, 2021)

The results are shown in table 6. Differences in tolerance are observed, favoring oral immunotherapy over sublingual immunotherapy, favoring a lower target dose (25mL of unheated milk) over a higher target dose (100mL of unheated milk), and favoring the use of unheated milk over heated milk.

Table 6. Tolerance in for different forms of immunotherapy after different periods of time.

|

Author |

Follow-up |

OIT-1 |

OIT-2 |

Relative risk (RR or OR) |

|

Keet (2012) |

60 weeks |

Sublingual IT (SLIT) |

OIT |

RR: 0.14 95% CI 0.02 to 0.94 |

|

1/10 (10%) |

14/20 (70%) |

|||

|

Nowak (2018) |

36 months |

Rapid escalation (+1 ladder every 6 months) |

Slow escalation (+1 ladder every 12 months) |

OR: 0.77* 95%CI 0.31 to 1.94 |

|

Ogura (2020) |

2 years |

High-dose (100%) |

Low-dose (25%) |

RR: 0.33 95% CI 0.04 to 2.80 |

|

1/13 (7.7%) |

3/13 (23.1%) |

|||

|

Nagakura (2021) |

1 year |

Heated milk |

Unheated milk |

|

|

3mL OFC 6/17 (35%) |

3mL OFC 8/16 (50%) |

RR: 0.71 95% CI 0.31 to 1.59 |

||

|

25mL OFC 3/17 (18%) |

25mL OFC 5/16 (31%) |

RR: 0.56 95% CI 0.16 to 1.99 |

*all participants randomized were already baked milk tolerant, n = 85

2. Mild IgE-symptoms or reactions

Three studies comparing different immunotherapies reported on IgE-symptoms or reactions, but differently. No large differences are observed in reactions for different forms of immunotherapy (table 7).

Table 7. Mild reactions to of immunotherapy treatment in children with IgE-mediated CMA.

|

Study |

Mild reactions (in number or % of doses) |

Information |

|||

|

OIT-1 |

OIT-2 |

||||

|

Keet (2012) |

SLIT 1802 of 6246 (29%) |

OIT 2402 of 10645 (23%) |

significantly more multisystem symptoms in the OIT group compared to SLIT (IRR, 11.5; P < .001) |

||

|

Ogura (2020) |

High-dose (100%) 15.4% |

Low-dose (25%) 10.3% |

Grade 1* (14.4% vs 9.5%) |

Grade 2* (0.9% vs 0.7%) |

Grade 3* (both 0.2%) |

|

Nagakura (2021) |

Heated milk 396 of 4916 (8.1%) |

Unheated milk 419 of 4383 (9.6%) |

Mild symptoms (7.4% vs 8.1%) |

Moderate (0.7% vs 1.4%) |

Severe (0.02% vs 0.0%) |

*Score based on Sampson scale

3. Adverse events (leading to epinephrine use or discontinuation of OIT)

All four studies reported on adverse events. The results on the use of epinephrine or discontinuation of OIT due to adverse events, are shown in table 8.

Table 8. Adverse events during different forms of immunotherapy, leading to epinephrine use or discontinuation of the immunotherapy.

|

Author |

Use of epinephrine |

Relative effect |

|

|

OIT-1 |

OIT-2 |

||

|

Keet (2012) |

Sublingual OIT (SLIT) 2/10 (20%) |

OIT 4/20 (20%) |

RR: 1.00 (95% CI 0.22 to 4.56) |

|

Ogura (2020) |

High-dose 1/13 (8%) |

Low-dose 1/13 (8%) |

RR: 1.00 (95% CI 0.07 to 14.34) |

|

Nagakura (2021) |

Unheated milk 1/17 (6%) |

Heated milk 1/16 (6%) |

RR: 0.89 (95% CI: 0.06 to 14.25) |

|

|

Discontinuation |

Relative effect |

|

|

OIT-1 |

OIT-2 |

||

|

Ogura (2020) |

High-dose 3/13 (23%) |

Low-dose 4/13 (31%) |

RR: 0.75 (95% CI: 0.21 to 2.71) |

Nowak (2018) reported no AEs to baked milk at home treated with epinephrine. There were 2 serious AEs: ovarian torsion and hospitalization for a virally-induced asthma exacerbation, both deemed unrelated to the study intervention.

4. Quality of life

No studies were included that compared two types of immunotherapies reported on quality of life.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question(s):

What are the benefits and risks of immunotherapy for children with an IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy?

Table 1. PICO

|

Patients |

Children with IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy |

|

Intervention |

Immunotherapy (e.g. milk ladder, baked milk, and epicutaneous immunotherapy) |

|

Control 1 Control 2 |

No immunotherapy, standard care Another form of immunotherapy |

|

Outcomes |

Tolerance, IgE-mediated symptoms or reactions, adverse events, quality of life |

|

Other selection criteria |

Study design: systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials Age up to 18 years |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline panel considered tolerance as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and IgE-mediated symptoms, adverse events, and quality of life as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the guideline panel did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The guideline panel defined 25% (0.8 ≥ RR ≥ 1.25) for dichotomous outcomes, 0.5 SD for continuous outcomes and standardized mean difference (0.5 ≥ SMD ≥ 0.5) as minimal clinically (patient) important differences.

Search and select (Methods)

A systematic literature search was performed by a medical information specialist using the bibliographic databases Embase.com and Ovid/Medline. Both databases were searched from 2000 to June 19th, 2024 for systematic reviews, RCTs and observational studies. Systematic searches were completed using a combination of controlled vocabulary/subject headings (e.g., Emtree-terms, MeSH) wherever they were available and natural language keywords. The overall search strategy was derived from three primary search concepts: (1) cow’s milk allergy; (2) children; (3) immunotherapy. Duplicates were removed using EndNote software. After deduplication, a total of 426 records were imported for title/abstract screening. Initially, 42 studies were selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 31 studies were excluded (see the exclusion table under the tab ‘Evidence tabellen’), and 11 studies were included.

Referenties

- Barten LJC, Zuurveld M, Faber J, Garssen J, Klok T. Oral immunotherapy as a curative treatment for food-allergic preschool children: Current evidence and potential underlying mechanisms. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2023 Nov;34(11):e14043. doi: 10.1111/pai.14043. PMID: 38010006.

- Dantzer J, Dunlop J, Psoter KJ, Keet C, Wood R. Efficacy and safety of baked milk oral immunotherapy in children with severe milk allergy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022 Apr;149(4):1383-1391.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.10.023. Epub 2021 Nov 2. PMID: 34740607.

- DAVO; Diëtisten Alliantie VoedselOvergevoeligheid. Melkladder – Geleidelijke introductie van koemelk bij niet-IgE gemedieerde allergie. 2019. Available via: https://allergiedietist-davo.nl/voor-professionals/melkladder/

- Jones SM, Kim EH, Nadeau KC, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Wood RA, Sampson HA, Scurlock AM, Chinthrajah S, Wang J, Pesek RD, Sindher SB, Kulis M, Johnson J, Spain K, Babineau DC, Chin H, Laurienzo-Panza J, Yan R, Larson D, Qin T, Whitehouse D, Sever ML, Sanda S, Plaut M, Wheatley LM, Burks AW; Immune Tolerance Network. Efficacy and safety of oral immunotherapy in children aged 1-3 years with peanut allergy (the Immune Tolerance Network IMPACT trial): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2022 Jan 22;399(10322):359-371. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02390-4. PMID: 35065784; PMCID: PMC9119642.

- Keet CA, Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA, Thyagarajan A, Schroeder JT, Hamilton RG, Boden S, Steele P, Driggers S, Burks AW, Wood RA. The safety and efficacy of sublingual and oral immunotherapy for milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Feb;129(2):448-55, 455.e1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.10.023. Epub 2011 Nov 30. PMID: 22130425; PMCID: PMC3437605.

- Klok T, Faber J, Verhoeven D, Kamps A, Brand HK. Oral immunotherapy in young children with food allergy (ORKA-NL Studie) – Study protocol version 3. ClinicalTrials.gov. Available via: https://cdn.clinicaltrials.gov/large-docs/98/NCT05738798/Prot_SAP_001.pdf

- Maeda M, Imai T, Ishikawa R, Nakamura T, Kamiya T, Kimura A, Fujita S, Akashi K, Tada H, Morita H, Matsumoto K, Katsunuma T. Effect of oral immunotherapy in children with milk allergy: The ORIMA study. Allergol Int. 2021 Apr;70(2):223-228. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2020.09.011. Epub 2020 Nov 25. PMID: 33248880.

- Martorell A, De la Hoz B, Ibáñez MD, Bone J, Terrados MS, Michavila A, Plaza AM, Alonso E, Garde J, Nevot S, Echeverria L, Santana C, Cerdá JC, Escudero C, Guallar I, Piquer M, Zapatero L, Ferré L, Bracamonte T, Muriel A, Martínez MI, Félix R. Oral desensitization as a useful treatment in 2-year-old children with cow's milk allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011 Sep;41(9):1297-304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03749.x. Epub 2011 Apr 11. PMID: 21481024.

- Nagakura KI, Sato S, Miura Y, Nishino M, Takahashi K, Asaumi T, Ogura K, Ebisawa M, Yanagida N. A randomized trial of oral immunotherapy for pediatric cow's milk-induced anaphylaxis: Heated vs unheated milk. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021 Jan;32(1):161-169. doi: 10.1111/pai.13352. Epub 2020 Sep 24. PMID: 32869399; PMCID: PMC7821001.

- Nowak-Węgrzyn A, Lawson K, Masilamani M, Kattan J, Bahnson HT, Sampson HA. Increased Tolerance to Less Extensively Heat-Denatured (Baked) Milk Products in Milk-Allergic Children. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018 Mar-Apr;6(2):486-495.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.10.021. Epub 2017 Dec 7. PMID: 29226808; PMCID: PMC5881948.

- Ogura K, Yanagida N, Sato S, Imai T, Ito K, Kando N, Ikeda M, Shibata R, Murakami Y, Fujisawa T, Nagao M, Kawamoto N, Kondo N, Urisu A, Tsuge I, Kondo Y, Sugai K, Uchida O, Urashima M, Taniguchi M, Ebisawa M. Evaluation of oral immunotherapy efficacy and safety by maintenance dose dependency: A multicenter randomized study. World Allergy Organ J. 2020 Sep 29;13(10):100463. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2020.100463. PMID: 33024480; PMCID: PMC7527748.

- Pajno GB, Caminiti L, Ruggeri P, De Luca R, Vita D, La Rosa M, Passalacqua G. Oral immunotherapy for cow's milk allergy with a weekly up-dosing regimen: a randomized single-blind controlled study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010 Nov;105(5):376-81. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.03.015. Epub 2010 Jul 31. PMID: 21055664.

- Petroni D, Bégin P, Bird JA, Brown-Whitehorn T, Chong HJ, Fleischer DM, Gagnon R, Jones SM, Leonard S, Makhija MM, Oriel RC, Shreffler WG, Sindher SB, Sussman GL, Yang WH, Bee KJ, Bois T, Campbell DE, Green TD, Rutault K, Sampson HA, Wood RA. Varying Doses of Epicutaneous Immunotherapy With Viaskin Milk vs Placebo in Children With Cow's Milk Allergy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2024 Apr 1;178(4):345-353. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.6630. Erratum in: JAMA Pediatr. 2024 Apr 1;178(4):421. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2024.0706. Erratum in: JAMA Pediatr. 2024 Jul 1;178(7):731. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2024.1288. PMID: 38407859; PMCID: PMC10897821.

- Salmivesi S, Korppi M, Mäkelä MJ, Paassilta M. Milk oral immunotherapy is effective in school-aged children. Acta Paediatr. 2013 Feb;102(2):172-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02815.x. Epub 2012 Sep 7. PMID: 22897785.

- Skripak JM, Nash SD, Rowley H, Brereton NH, Oh S, Hamilton RG, Matsui EC, Burks AW, Wood RA. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of milk oral immunotherapy for cow's milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Dec;122(6):1154-60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.030. Epub 2008 Oct 25. PMID: 18951617; PMCID: PMC3764488.

- Vickery BP, Berglund JP, Burk CM, Fine JP, Kim EH, Kim JI, Keet CA, Kulis M, Orgel KG, Guo R, Steele PH, Virkud YV, Ye P, Wright BL, Wood RA, Burks AW. Early oral immunotherapy in peanut-allergic preschool children is safe and highly effective. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 Jan;139(1):173-181.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.027. Epub 2016 Aug 10. PMID: 27522159; PMCID: PMC5222765.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference

|

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? |

Was the allocation adequately concealed? |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented? Were patients | healthcare providers | data collectors | outcome assessors | data analysts blinded? |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

|

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

|

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

|

Overall risk of bias If applicable/ necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Dantzer, 2022 |

Definitely yes

Reason: random code was generated using computer-generated sheets with block-stratified assignment of block size of 6, 1:1 distribution of active to placebo. |

Definitely yes

Reason: The participants were randomized using the next available slot on the random code by research pharmacist. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Patients, study coordinators, nurses, and clinicians were blinded to treatment arm assignment. The pharmacist and nutritionist remained unblinded and had access to the randomization log. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Two subjects (one in each group) dropped out. No imputation methods were used. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Study outcomes same as registered protocol. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other problems noted. |

Low

|

|

Keet, 2012 |

Probably yes

Reason: computerized block-stratified randomization program using a block size of 6 |

No information |

Definitely no

Reason: Open label study |

Definitely yes

Reason: Two subjects dropped out (both in OIT group). No imputation methods were used. |

Probably yes

Reason: All outcomes from methods reported, yet no previously published study protocol available. |

Probably yes

Reason: Absence of placebo group. |

Some concerns - No blinding - Missing information about allocation concealment |

|

Nowak-Wegrzyn, 2018 |

Unclear

Reason: study only reports “Randomization was stratified based on the initial food that was tolerated during baseline-OFC” |

No information |

Probably no

Reason: not reported, assumed is no blinding. |

Definitely no

Reason: 32 participants (37.6%) discontinued; similar between arms. Major reason scheduling conflicts and long-distance travel. LOCF was used for ITT. |

Probably yes

Reason: All outcomes from methods reported, yet no previously published study protocol available. |

Definitely no

Reason: selection bias due to the inclusion of only baked-milk tolerant participants in the randomization groups. |

High - Unclear if randomization was adequate - No blinding - Frequent discontinuations, inadequate imputation methods used - Selection bias |

|

Martorell, 2011 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Random numbers table was used. |

No information |

Definitely no

Reason: Absence of blinding for the control group. |

Probably no

Reason: 2 participants (7%) in the intervention group dropped out, and 7 participants (23%) in the control group. ITT was used. |

Probably yes

Reason: Trial is registered (NCT01199484), but not available. All outcomes from methods reported. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other problems noted. |

Some concerns - No blinding - Loss to follow-up |

|

Maeda, 2021 |

Probably yes

Reason: “randomly allocated” but not specified how |

Probably yes

Reason: Randomization was managed by a data center independent of the rater and subjects. |

Definitely no

Reason: No placebo for the control group. |

Probably no

Reason: 2 participants (14%) in the intervention group dropped out due to developing symptoms three or more times. No drop-outs in control group. No imputation methods were used |

Definitely yes

Reason: registered trial (UMIN 000005784); all predetermined outcomes reported. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other problems noted. |

Some concerns - No blinding - Missing information about randomization procedure - Missing outcome data

|

|

Nagakura, 2021 |

Definitely yes

Reason: random number generator. |

No information |

No information

Authors state that the study is double-blind in the title, however no information on blinding is provided.

|

Probably yes

Reason: 1 participant (6%) in the intervention group dropped out. |

Probably yes

Reason: All outcomes from methods reported, yet no previously published study protocol available |

Probably yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

Low |

|

Ogura, 2020 |

Probably yes

Reason: stratified random assignment |

No information |

Probably no

Reason: no blinding reported, unclear if patients were aware of other group dosage |

Probably no

Reason: 5 participants (38%) in the 100%-dose group and 1 particpant (8%) in the 25%-dose group were lost to follow- up. Additionally, 3 participants (23%) discontinued due to AD in the 100%-dose group compared to 4 (30%) in the 25%-dose group. An intention to treat analysis was performed |

Probably yes

Reason: All outcomes from methods reported, yet no previously published study protocol available. |

|

Some concerns - No blinding - Loss to follow up high, but ITT |

|

Pajno, 2010 |

Probably yes

Reason: Computer-generated randomization list was used. |

No information |

Definitely no

Reason: Single-blind study. Participants were not blinded, investigators were. |

Probably yes

Reason: 2 participants (13%) in the intervention group dropped out, and 1 participant (7%) in the control group. No imputation methods were used. |

Probably yes

Reason: All outcomes from methods reported, yet no previously published study protocol available. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other problems noted. |

Some concerns - No blinding of participants - Missing information about allocation concealment

|

|

Petroni, 2024 |

Probably yes

Reason: Participants were randomized in a 1:1:1:1 ratio. |

No information |

Definitely yes

Reason: Double-blind trial. |

Probably yes

Reason: 1 participant (2%) in placebo group discontinued, and 2 (4%), 4 (8%), and 2 (4%) participants discontinued the different intervention groups. ITT was used. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Trial is registered (NCT02223182). Outcomes are reported as prespecified. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other problems noted. |

Low |

|

Skripak, 2008 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Randomized by a 2:1 block randomization |

No information |

Probably yes

Reason: Double-blind trial, but blinding is not described. Both placebo and CM were sweetened. |

Probably yes

Reason: 1 participant in the intervention group discontinued. |

Probably yes

Reason: All outcomes from methods reported, yet no previously published study protocol available. |

Probably yes

Reason: No other problems noted. |

Low |

|

Salmivesi, 2013 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Randomized by a 2:1 block randomization, 6 p blocks (28 participants). |

No information |

Probably yes;

Reason: milk was prepared separately an packed in identical bottles, all products were flavoured with sugar. However, participants might have noticed a difference in taste. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Probably no;

No subgroup reports for symptoms or long term success |

Probably no

Reason: parents reported symptoms for dose 10 to end of trial. |

Some concerns - Symptoms (parent -reported) - No subgroup reports

|

Tabel. In- en Exclusiecriteria van de geïncludeerde studies

|

Author, year |

Study design and goal |

Inclusion criteria |

Exclusion criteria |

|

Comparison 1: Immunotherapy compared to placebo or control |

|||

|

Dantzer (2022) |

an RCT to evaluate the safety and efficacy of baked milk oral immunotherapy |

Children aged 3 to 18 years were included:

|

Participants were excluded if they had a history of severe anaphylaxis resulting in hypotension, neurological compromise, or mechanical ventilation, severe or poorly controlled asthma, poorly controlled atopic dermatitis, and/or a history of eosinophilic esophagitis in the past 3 years. |

|

Maeda (2021) |

RCT to evaluate the efficacy of OIT in Japanese children with severe cow's milk allergy whom spontaneous acquisition of tolerance was unlikely |

Children aged <13 years were included:

|

Children were excluded if they had a history of anaphalaxic shock, uncontrolled asthma, or uncontrolled atopical dermatitis.

|

|

Martorell (2011) |

RCT to evaluate the safety and efficacy of oral desensitization – as a treatment alternative to elimination diet. |

Infants aged 24 to 36 months were included:

|

Exclusion criteria were non-IgE-mediated or non-immunological adverse reactions to cow’s milk, clinical manifestations of anaphylactic shock after ingestion, immunosuppressor therapy, b-blockers, malignant or immunopathological diseases and/or primary or secondary immune deficiencies, and associated diseases contraindicating the use of epinephrine. |

|

Pajno (2010) |

RCT to evaluate a patient-friendly desensitization regime with weekly up-dosing |

Children aged 4 to 10 years were included with demonstrated IgE-mediated CM allergy were included (diagnosis was based on clinical history, the presence of CM specific IgE by means of skin testing and CAP-RAST assay, and positive DBPCFC result) |

To ensure safety of DBPCFC and the desensitization protocol with soy formula, none of the participants had a positive clinical history or suspected adverse reactions to soy formula, or positive SPT or sIgE levels to soy. Sensitization to other foods was an exclusion criteria as well |

|

Salmivesi (2013) |

double-blind RCT to evaluate if OIT can lead to tolerance. Participants were randomized to an OIT group or a placebo group (soy, oat or ice milk) in 2:1 ratio. |

Children between 6 and 14 years of age were included:

|

|

|

Skripak (2008) |

double-blind RCT (milk or placebo group in 2:1 ratio) to evaluate the safety and efficacy of OIT in children with IgE-mediated CM allergy. |

Children were included:

|

Exclusion criteria were a history of anaphylaxis requiring hospitalization, history of intubation related to asthma, or current diagnosis of severe asthma. |

|

Petroni (2024) |

RCT to evaluate the efficacy and safety of epicutaneous immunotherapy with Viaskin Milk |

Children aged 2 to 17 years were included:

|

Participants were excluded if they had a history of severe anaphylaxis to CM or persistent uncontrolled asthma. |

|

Comparison 2: Comparisons between two types of immunotherapy |

|||

|

Ogura (2020) |

open-label RCT to evaluate efficacy of target dosed OIT compared to reduced dose OIT |

children with IgE mediated egg- wheat or CM allergy between 3 and 15 years of age were included:

No skin prick test was performed. The thresholds for CM allergy were: > 102 mg of milk protein (3 mL of unheated milk) and ≤ 850 mg (25 mL of unheated milk). |

Exclusion criteria were no allergic symptoms at baseline OFC, anaphylaxis with adrenaline injection at baseline OFC, uncontrolled underlying desease, previous treatment with other immunotherapy and developmental or mental disorder. |

|

Nagakura (2021) |

double-blind RCT to compare OIT with heated milk with an OIT with unheated milk. |

Patients ≥5 years of age were included with symptom onset during an DBPCFC with 3-ML heated milk. |

Exclusion criteria were a negative DBPCFC, uncontrolled atopic dermatitis, asthma, or another ongoing immunotherapy. |

|

Keet (2012) |

RCT to evaluate the efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy with or without following oral immunotherapy |

Children were included:

|

Exclusion criteria were severe persistent asthma, use of greater than 400 or 600 μg/d fluticasone, a history of intubation for asthma, and a history of a severe episode of anaphylaxis to CM, which was defined as a reaction with hypoxia, incontinence, syncope, or requirement for admission to the intensive care unit. |

|

Nowak-Wgrzyn (2018) |

RCT to evaluate the effects of more or less frequent introduction of more allergenic forms of milk (MAFM) |

children 4-10 years of age were included:

|

Children were excluded if they had a history (within the past 2 years) of life-threatening anaphylaxis, poorly controlled asthma or atopic dermatitis, eosinophilic esophagitis caused by CM, immunotherapy with anti-IgE antibody within 1 year of enrollment, participation in any food allergy therapeutic trial, or CM-IgE levels greater than 35 kUA/L. |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Bognanni A, Chu DK, Firmino RT, Arasi S, Waffenschmidt S, Agarwal A, Dziechciarz P, Horvath A, Jebai R, Mihara H, Roldan Y, Said M, Shamir R, Bozzola M, Bahna S, Fiocchi A, Waserman S, Schünemann HJ, Brożek JL; WAO DRACMA Guideline Group. World Allergy Organization (WAO) Diagnosis and Rationale for Action against Cow's Milk Allergy (DRACMA) guideline update - XIII - Oral immunotherapy for CMA - Systematic review. World Allergy Organ J. 2022 Sep 8;15(9):100682. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2022.100682. PMID: 36185550; PMCID: PMC9474924. |

No IgE-mediated allergy conform definition |

|

Brożek JL, Terracciano L, Hsu J, Kreis J, Compalati E, Santesso N, Fiocchi A, Schünemann HJ. Oral immunotherapy for IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012 Mar;42(3):363-74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03948.x. PMID: 22356141. |

Unclear definition of IgE-mediated CMA. Systematic review that also includes observational studies |

|

Caminiti L, Passalacqua G, Barberi S, Vita D, Barberio G, De Luca R, Pajno GB. A new protocol for specific oral tolerance induction in children with IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2009 Jul-Aug;30(4):443-8. doi: 10.2500/aap.2009.30.3221. Epub 2009 Mar 13. PMID: 19288980. |

Wrong study design; not an RCT. |

|

d'Art YM, Forristal L, Byrne AM, Fitzsimons J, van Ree R, DunnGalvin A, Hourihane JO. Single low-dose exposure to cow's milk at diagnosis accelerates cow's milk allergic infants' progress on a milk ladder programme. Allergy. 2022 Sep;77(9):2760-2769. doi: 10.1111/all.15312. Epub 2022 Apr 22. PMID: 35403213; PMCID: PMC9543429. |

Wrong comparison |

|

de Boissieu D, Dupont C. Sublingual immunotherapy for cow's milk protein allergy: a preliminary report. Allergy. 2006 Oct;61(10):1238-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01196.x. PMID: 16942579. |

Wrong study design; not an RCT. |

|

de Silva D, Rodríguez Del Río P, de Jong NW, Khaleva E, Singh C, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Muraro A, Begin P, Pajno G, Fiocchi A, Sanchez A, Jones C, Nilsson C, Bindslev-Jensen C, Wong G, Sampson H, Beyer K, Marchisotto MJ, Fernandez Rivas M, Meyer R, Lau S, Nurmatov U, Roberts G; GA2LEN Food Allergy Guidelines Group. Allergen immunotherapy and/or biologicals for IgE-mediated food allergy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2022 Jun;77(6):1852-1862. doi: 10.1111/all.15211. Epub 2022 Jan 19. PMID: 35001400; PMCID: PMC9303769. |

No IgE-mediated allergy conform definition. Unclear definition of in- and exclusion criteria. |

|

Esmaeilzadeh H, Alyasin S, Haghighat M, Nabavizadeh H, Esmaeilzadeh E, Mosavat F. The effect of baked milk on accelerating unheated cow's milk tolerance: A control randomized clinical trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2018 Nov;29(7):747-753. doi: 10.1111/pai.12958. Epub 2018 Sep 12. PMID: 30027590. |

Wrong study design; not an RCT. Included children are already tolerant. |

|

Fisher HR, du Toit G, Lack G. Specific oral tolerance induction in food allergic children: is oral desensitisation more effective than allergen avoidance?: a meta-analysis of published RCTs. Arch Dis Child. 2011 Mar;96(3):259-64. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.172460. Epub 2010 Jun 3. PMID: 20522461. |

No IgE-mediated allergy conform definition |

|

Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA, Masilamani M, Gu W, Brittain E, Wood R, Kim J, Nadeau K, Jarvinen KM, Grishin A, Lindblad R, Sampson HA. Mechanistic correlates of clinical responses to omalizumab in the setting of oral immunotherapy for milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 Oct;140(4):1043-1053.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.03.028. Epub 2017 Apr 13. PMID: 28414061; PMCID: PMC5632581. |

Wrong study design; not an RCT. |

|

García-Ara C, Pedrosa M, Belver MT, Martín-Muñoz MF, Quirce S, Boyano-Martínez T. Efficacy and safety of oral desensitization in children with cow's milk allergy according to their serum specific IgE level. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013 Apr;110(4):290-4. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.01.013. Epub 2013 Feb 14. PMID: 23535095. |

Wrong study design; not an RCT. |

|

Gunaydin NC, Azarsiz E, Susluer SY, Kutukculer N, Gunduz C, Gulen F, Aksu G, Tanac R, Demir E. Immunologic changes during desensitization with cow's milk: How it differs from natural tolerance or nonallergic state? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022 Dec;129(6):751-757.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2022.07.022. Epub 2022 Jul 30. PMID: 35914664. |

Wrong study design; not an RCT. |

|

Kaneko H, Teramoto T, Kondo M, Morita H, Ohnishi H, Orii K, Matsui E, Kondo N. Efficacy of the slow dose-up method for specific oral tolerance induction in children with cow's milk allergy: comparison with reported protocols. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2010;20(6):538-9. PMID: 21243943. |

Wrong study design; not an RCT. |

|

Kauppila TK, Paassilta M, Kukkonen AK, Kuitunen M, Pelkonen AS, Makela MJ. Outcome of oral immunotherapy for persistent cow's milk allergy from 11 years of experience in Finland. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2019 May;30(3):356-362. doi: 10.1111/pai.13025. Epub 2019 Feb 18. PMID: 30685892. |

Wrong study design; not an RCT. |

|

Kim JS, Nowak-Węgrzyn A, Sicherer SH, Noone S, Moshier EL, Sampson HA. Dietary baked milk accelerates the resolution of cow's milk allergy in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Jul;128(1):125-131.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.036. Epub 2011 May 23. PMID: 21601913; PMCID: PMC3151608. |

Wrong study design; not an RCT. |

|

Longo G, Barbi E, Berti I, Meneghetti R, Pittalis A, Ronfani L, Ventura A. Specific oral tolerance induction in children with very severe cow's milk-induced reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Feb;121(2):343-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.029. Epub 2007 Dec 26. PMID: 18158176. |

No IgE-mediated allergy conform definition |

|

Martorell Calatayud C, Muriel García A, Martorell Aragonés A, De La Hoz Caballer B. Safety and efficacy profile and immunological changes associated with oral immunotherapy for IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2014;24(5):298-307. PMID: 25345300. |

Non-recent systematic review |

|

Miura Y, Nagakura KI, Nishino M, Takei M, Takahashi K, Asaumi T, Ogura K, Sato S, Ebisawa M, Yanagida N. Long-term follow-up of fixed low-dose oral immunotherapy for children with severe cow's milk allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021 May;32(4):734-741. doi: 10.1111/pai.13442. Epub 2021 Jan 24. PMID: 33393118. |

Wrong study design; not an RCT. |

|

Morisset M, Moneret-Vautrin DA, Guenard L, Cuny JM, Frentz P, Hatahet R, Hanss Ch, Beaudouin E, Petit N, Kanny G. Oral desensitization in children with milk and egg allergies obtains recovery in a significant proportion of cases. A randomized study in 60 children with cow's milk allergy and 90 children with egg allergy. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007 Jan;39(1):12-9. PMID: 17375736. |

No IgE-mediated allergy conform definition |

|

Paassilta M, Salmivesi S, Mäki T, Helminen M, Korppi M. Children who were treated with oral immunotherapy for cows' milk allergy showed long-term desensitisation seven years later. Acta Paediatr. 2016 Feb;105(2):215-9. doi: 10.1111/apa.13251. Epub 2015 Nov 17. PMID: 26503614. |

Wrong study design; not an RCT. |

|

Rigbi NE, Goldberg MR, Levy MB, Nachshon L, Golobov K, Elizur A. Changes in patient quality of life during oral immunotherapy for food allergy. Allergy. 2017 Dec;72(12):1883-1890. doi: 10.1111/all.13211. Epub 2017 Jun 15. PMID: 28542911. |

No subgroup analysis for CMA |

|

Riggioni C, Oton T, Carmona L, Du Toit G, Skypala I, Santos AF. Immunotherapy and biologics in the management of IgE-mediated food allergy: Systematic review and meta-analyses of efficacy and safety. Allergy. 2024 Aug;79(8):2097-2127. doi: 10.1111/all.16129. Epub 2024 May 15. PMID: 38747333. |

No clear definition of IgE-mediated CMA. |

|

Staden U, Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Brewe F, Wahn U, Niggemann B, Beyer K. Specific oral tolerance induction in food allergy in children: efficacy and clinical patterns of reaction. Allergy. 2007 Nov;62(11):1261-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01501.x. PMID: 17919140. |

No subgroup analysis for CMA. |

|

Sugiura S, Kitamura K, Makino A, Matsui T, Furuta T, Takasato Y, Kando N, Ito K. Slow low-dose oral immunotherapy: Threshold and immunological change. Allergol Int. 2020 Oct;69(4):601-609. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2020.03.008. Epub 2020 May 20. PMID: 32444309. |

No subgroup analysis for CMA. |

|

Takahashi M, Taniuchi S, Soejima K, Hatano Y, Yamanouchi S, Kaneko K. Two-weeks-sustained unresponsiveness by oral immunotherapy using microwave heated cow's milk for children with cow's milk allergy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2016 Aug 26;12(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s13223-016-0150-0. Erratum in: Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2016 Oct 31;12:57. doi: 10.1186/s13223-016-0160-y. PMID: 27570533; PMCID: PMC5002153. |

Wrong study design; not an RCT. |

|

Takaoka Y, Yajima Y, Ito YM, Kumon J, Muroya T, Tsurinaga Y, Shigekawa A, Takahashi S, Iba N, Tsuji T, Nishikido T, Yoshida Y, Doi S, Kameda M. Single-Center Noninferiority Randomized Trial on the Efficacy and Safety of Low- and High-Dose Rush Oral Milk Immunotherapy for Severe Milk Allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2020;181(9):699-705. doi: 10.1159/000508627. Epub 2020 Jun 22. PMID: 32570237. |

No IgE-mediated allergy conform definition |

|

Tang L, Yu Y, Pu X, Chen J. Oral immunotherapy for Immunoglobulin E-mediated cow's milk allergy in children: A systematic review and meta analysis. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2022 Oct;10(10):e704. doi: 10.1002/iid3.704. PMID: 36169249; PMCID: PMC9476891. |

No IgE-mediated allergy conform definition |

|

Tosca MA, Olcese R, Marinelli G, Schiavetti I, Ciprandi G. Oral Immunotherapy for Children with Cow's Milk Allergy: A Practical Approach. Children (Basel). 2022 Nov 30;9(12):1872. doi: 10.3390/children9121872. PMID: 36553316; PMCID: PMC9777117. |

Wrong study design: retrospective. No subgroup analysis for IgE-mediated CMA |

|

van Boven FE, Arends NJT, Sprikkelman AB, Emons JAM, Hendriks AI, van Splunter M, Schreurs MWJ, Terlouw S, Gerth van Wijk R, Wichers HJ, Savelkoul HFJ, van Neerven RJJ, Hettinga KA, de Jong NW. Tolerance Induction in Cow's Milk Allergic Children by Heated Cow's Milk Protein: The iAGE Follow-Up Study. Nutrients. 2023 Feb 27;15(5):1181. doi: 10.3390/nu15051181. PMID: 36904179; PMCID: PMC10005260. |

No IgE-mediated allergy conform definition |

|

Weinbrand-Goichberg J, Benor S, Rottem M, Shacham N, Mandelberg A, Levine A, Sade K, Kivity S, Dalal I. Long-term outcomes following baked milk-containing diet for IgE-mediated milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017 Nov-Dec;5(6):1776-1778.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.04.018. Epub 2017 Jun 2. PMID: 28583481. |

Wrong design; letter to the editor |

|

Xiong L, Lin J, Luo Y, Chen W, Dai J. The Efficacy and Safety of Epicutaneous Immunotherapy for Allergic Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2020;181(3):170-182. doi: 10.1159/000504366. Epub 2019 Dec 4. PMID: 31801149. |

Systematic review that only includes one study with children with CMA |

|

Yeung JP, Kloda LA, McDevitt J, Ben-Shoshan M, Alizadehfar R. Oral immunotherapy for milk allergy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Nov 14;11(11):CD009542. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009542.pub2. PMID: 23152278; PMCID: PMC7390504. |

Non-recent systematic review |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 14-07-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 14-07-2025

Algemene gegevens

De herziening van deze richtlijn werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kinderen met een IgE-gemedieerde koemelkallergie.

Werkgroep

- Mevr. dr. E.C. (Eva) Koffeman, kinderarts-allergoloog, namens de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde (NVK) (voorzitter)

- Mevr. dr. L.J. (Lonneke) Landzaat, kinderarts-allergoloog, namens de NVK

- Mevr. dr. M.M.J. (Marjoke) Verweij, kinderarts, namens de NVK

- Mevr. drs. K. (Kelly) van de Vorst-van der Velde, kinderarts-allergoloog, namens de NVK

- Mevr. dr. L. (Lonneke) van Onzenoort-Bokken, kinderarts, namens de NVK

- Mevr. drs. M.F. (Maartje) van Velzen, kinderarts, namens de NVK

- Mevr. dr. B. (Berber) Vlieg-Boerstra, diëtist, namens de Nederlandse Vereniging van Diëtisten (NVD/DAVO)

- Mevr. O. (Olga) Benjamin-Aalst, diëtist, namens de NVD/DAVO

- Mevr. E. (Erna) Botjes, voedselallergie en niet-allergische voedselovergevoeligheid belangenbehartiger, namens Stichting Voedselallergie

- Mevr. C. (Chantal) Janssen, verpleegkundig specialist, namens het Netwerk van Allergie Professionals (NAPRO)

Klankbordgroep

- Mevr. drs. D.A. (Dana-Anne) de Gast-Bakker, kinderarts, namens de NVK

- Mevr. drs. E.A. (Ellen) Croonen, kinderlongarts, namens de NVK

- Mevr. drs. E. (Ester) Rijks, jeugdarts, namens AJN Jeugdartsen Nederland

- Mevr. D.G. (Daphne) Philips, verpleegkundig specialist, namens NAPRO

- Mevr. (M.) Mathilde Serné, lactatiekundige, namens de Nederlandse Vereniging van Lactatiekundigen (NVL)

- Mevr. M. (Maria) Oligschläger-Lindelauf, lactatiekundige, namens de NVL

Met ondersteuning van

- Mevr. dr. M.M.J. (Machteld) van Rooijen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mevr. drs. L.C. (Laura) van Wijngaarden, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Koffeman (voorzitter) |

kinderarts-allergoloog, Rijnstate Arnhem |

Geen. |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: 1. Onderzoeksproject SinFoNIA: Specialist Infant Formulas in non-IgE mediated cow's milk allergy. In 2018 financiering toegezegd gekregen (Health Holland met behulp van Nutricia Research) maar geannuleerd door stopzetting project (maart 2020). Het project heeft niet geleid tot publicaties. 2. Lokale hoofdonderzoeker voor BAT koemelk bij koemelkallergie, gefinancierd met de beurs van ZonMW Veelbelovende Zorg.

Presentaties koemelkallergie, voedselallergie en FPIES (in brede zin: het gehele ziektebeeld in het kader van congres of nascholing) wanneer deze onderwijskundig belang dienen. - 2020 Mead Johnson, webinar voor kinderartsen en jeugdartsen - 2021 NVK congres (sessie gesponsord door Nestle) De eventuele honoraria die voortvloeien uit deze presentaties werden tot start van de richtlijn gestort aan het Vriendenfonds Rijnstate t.b.v. opleiding en onderzoek binnen de kinderallergologie. Gedurende voorzitterschap richtlijn is voor deze presentaties geen honorarium meer aangenomen. . |

Geen restricties |

|

Landzaat |

Kinderarts-allergoloog, Elisabeth-Tweesteden ziekenhuis Tilburg |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties. |

|

Verweij |

Kinderarts, VieCurie Medisch centrum |

Geen. |

In het VieCurie wordt gewerkt aan uitbreiding van het kinderallergiecentrum. |

Geen restricties. |

|

Van der Vorst- van der Velde |

Kinderarts-allergoloog, Maasstad ziekenhuis Rotterdam |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties. |

|

Onzenoort |

Kinderarts, Máxima Medisch centrum Eindhoven |

Financiële vergoeding voor deze werkzaamheden. |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: Lokale hoofdonderzoeker voor 3 projecten: 1. D-CAAP studie: onderzoek naar 0- toepassing corticosteroïden naast IVIG en acetylsalicylzuur (gefinancierd door UCL) 2. COPP studie: onderzoek naar covid infecties in kinderen (gefinancierd door LUMC/ ZonMW) 3. SVSpread: observationeel onderzoek naar RSV infecties (gefinancierd door UMCU/ ZonMW)

Presentaties koemelkeiwitallergie (gehele ziektebeeld en behandeling daarvan, geen invloed van sponsor op inhoud) in het kader van scholingen of congressen (Nutricia). |

Geen restricties. |

|

Van Velzen |

Kinderarts, Meander MC Amerstfoort |

Geen. |

Presentaties voedselallergie (gehele ziektebeeld en behandeling daarvan, geen invloed van sponsor op inhoud) in het kader van scholing, waarvoor honorarium beschikbaar werd gesteld. Bewuste samenwerking met alle spelers op de Nederlandse markt om binding met enkel bedrijf te voorkomen (o.a. Nutricia, Mead Johnson, Friso/Hero). |

Geen restricties. |

|

Vlieg-Boerstra |

Diëtist, Rijnstate Arnhem |

Lid Advisory board: Nestle, Nutricia, Vini Mini (producent pindapoeder), tot 1-1-2023: Marfo Food Groups (waarvoor vergoeding) |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: 1. Principal investigator van Groei studie: studie over de groei bij kinderen met allergie (sponsoring Nutricia) 2. Principal investigator van studie voeding bij borstvoeding, waarin voedingspatroon van moeder en HMO's in moedermelk worden onderzocht. Studie is volledig onafhankelijk opgezet en de resultaten worden niet beïnvloedt door de sponsor (Nutricia betaalt enkel de HMO bepalingen)

Expertise voedselprovocaties en dieetbehandeling van koemelkallergie via eigen praktijk (maatschap Vlieg Diëtisten)

Presentaties voedselallergie (inclusief koemelkallergie, en indicatie over typen voedingen in het algemeen; vrije invulling van inhoud) in het kader van scholing, waarvoor honorarium beschikbaar werd gesteld (Nestle, Nutricia). |

Geen restricties. Studies (externe onderzoeken) hebben geen invloed op de modules in de richtlijn, De studies gaan over de bestanddelen van moedermelk. |

|

Benjamin- van Aalst |

Diëtist-onderzoeker, OLVG Amsterdam Diëtist, Noordwest ziekenhuisgroep |

Lid dagelijks bestuur Netwerk Kinderdiëtisten. |

Presentaties voedselallergie (gehele ziektebeeld en behandeling daarvan) in het kader van scholing, waarvoor honorarium beschikbaar werd gesteld. Bewuste samenwerking met alle spelers op de Nederlandse markt om binding met enkel bedrijf te voorkomen (Nutricia, Reckitt, Abbott). |

Geen restricties. |

|

Janssen |

Verpleegkundig specialist kinderallergologie, Zuyderland Medisch centrum, Heerlen |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties. |

|

Botjes |

Voedselallergie belangenbehartiger, Stichting Voedselallergie |

Geen. |

Geen. |