Fluoxetine

Uitgangsvraag

Wat zijn de effecten van fluoxetine op het herstel na een herseninfarct en/of hersenbloeding?

Aanbeveling

Schrijf geen fluoxetine voor bij patiënten met een herseninfarct of hersenbloeding voor het bevorderen van het functionele herstel.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Op dit moment is er sterk bewijs dat het geven van dagelijks 10 tot 20 mg fluoxetine geen voordelen heeft voor wat betreft de dagelijkse activiteiten 6 of 12 maanden na een beroerte. Het is echter niet uitgesloten dat er wel op drie maanden na een herseninfarct of hersenbloeding tijdelijk klinisch relevante, gunstige effecten worden gevonden van fluoxetine voor wat betreft het functionele herstel (mRS score) en het motorisch herstel in termen van synergiën (FMMS-score). Eveneens is niet een indirect effect uitgesloten dat bij mensen met aanvankelijk een depressie baat kunnen hebben van fluoxetine op motorisch herstel van de bovenste extremiteit. Echter de bewijskracht van deze laatste conclusie is laag.

Er waren geen data beschikbaar voor motorisch herstel na 6 of 12 maanden. De overall bewijskracht van de effecten voor motorisch herstel op 3 maanden is laag. De belangrijkste redenen hiervoor zijn een kleine studieomvang en de overlap van de 95% betrouwbaarheidsgrenzen met een neutraal effect. Theoretisch is het mogelijk dat fluoxetine het beloop versnelt maar niet van invloed is op het uiteindelijk herstel, echter meer onderzoek is hiervoor nodig. Een mogelijke interactie tussen hoge dosering oefentherapie en fluoxetine op het sensomotorisch beloop is daarmee nog onduidelijk. Hier ligt een kennislacune.

Wel zijn er sterke aanwijzingen dat fluoxetine een gunstig effect heeft op verbetering van de stemming van de patiënt. Er werd namelijk een klinisch relevant gunstig effect gevonden op het aantal patiënten met een (nieuwe) depressie 6 maanden na de beroerte, met name bij de patiënten met depressie. Deze bevinding had een hoge bewijskracht.

Hiertegenover staat dat de grote onderzoeken eenduidig aangeven dat het dagelijks innemen van 10 of 20mg fluoxetine schadelijk kan zijn voor de patiënt in de vorm van valincident al dan niet met botfracturen, epilepsie of ontregeling van de elektrolyten- en/of glucose-huishouding. De kans hierop is klein, maar wel significant groter dan in de controlegroep. Er is voldoende bewijs dat fluoxetine de kans op bovengenoemde complicaties vergroot wanneer dit wordt afgezet tegenover placebo in 6 of 12 maanden na een herseninfarct of hersenbloeding.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Voor patiënten is het belangrijk dat de behandeling met fluoxetine veilig is en een positief resultaat oplevert. Echter lijkt behandeling met fluoxetine, gezien de risico’s, geen veilige optie. De patiënt dient duidelijk en volledig over deze risico’s te worden geïnformeerd (zie ook module Organisatie van zorg, informatievoorziening en informatieoverdracht). Een subgroep waarbij behandeling met fluoxetine toch overwogen zou kunnen worden is de groep die na zes maanden een (nieuwe) depressie heeft ontwikkeld. Goed overleg tussen de behandelend arts en de patiënt hierover is noodzakelijk, waarin de voor- en nadelen van de interventie worden besproken (‘Samen Beslissen’).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Alhoewel fluoxetine een goedkoop middel is, zijn de mogelijke lage kosten niet in verhouding tot de nadelen van het medicijn.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Overwegingen met betrekking tot de aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie zijn niet van toepassing.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Voorschrijven van fluoxetine wordt afgeraden voor patiënten met een herseninfarct of hersenbloeding zonder klinische depressie op basis van een geringe effectiviteit en bijwerkingen met een verhoogde kans op complicaties zoals vallen, al dan niet met grotere kans op botfracturen en metabole ontregeling.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Aangenomen wordt dat fluoxetine, een selectieve serotonine reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), naast een gunstig effect op stemming, ook het motorisch herstel na een beroerte gunstig zou kunnen beïnvloeden en daarmee zou kunnen leiden tot betere functionele uitkomsten. Dierexperimenteel onderzoek laat zien dat dagelijks toedienen van fluoxetine tijdens de eerste weken na een herseninfarct de synaptogenese en daarmee de hersenplasticiteit stimuleert (Kwan, 2015). Ook in een eerste fase II trial bij 118 patiënten met een eerste herseninfarct werden gunstige effecten gevonden op het motorisch herstel van de bovenste extremiteit bij dagelijks gebruik van 10 of 20 mg fluoxetine (in vergelijking met een placebo) gemeten met een Fugl-Meyer Motor Score (FMMS) en modified Rankin Scale (mRS) schaal (Chollet, 2011). Dit effect werd nog eens bevestigd in een andere fase II trial (Asadollahi, 2018). Dit laatste suggereert dat het dagelijks nemen van 10 tot 20 mg fluoxetine het motorisch herstel en vaardigheden gunstig kan beïnvloeden na een herseninfarct of hersenbloeding, naast andere gunstige effecten, zoals een verbeterde stemming ten opzichte van de controle groep die een placebo kreeg. Bembenek (2020) liet echter geen differentieel effect zien van fluoxetine op functioneel/motorisch herstel in een fase II trial met 30 patiënten. Vooralsnog werden in deze fase II trials geen nadelige effecten gerapporteerd van het dagelijks voorschrijven van fluoxetine (10 tot 20 mg per dag) voor patiënten met een herseninfarct of hersenbloeding. De vraag is of dit gunstige effect uit verschillende fase II onderzoeken ook wordt gevonden in grotere fase III of IV gerandomiseerd onderzoeken bij patiënten met een herseninfarct of hersenbloeding.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Motor recovery (crucial)

At 3 months

|

Low GRADE |

Fluoxetine may improve motor recovery when compared to placebo treatment at three months after stroke.

Sources: (Chollet, 2011; Marquez-Romero, 2013; Asadollahi, 2018) |

2. Global activities of daily living (crucial)

2.1 At 3 months

|

Low GRADE |

Fluoxetine may improve global activities of daily living when compared to placebo treatment at three months after stroke.

Sources: (Chollet, 2011; Marquez-Romero, 2013) |

2.2 At 6/12 months

|

High GRADE |

Fluoxetine results in little to no difference in global activities of daily living when compared to placebo treatment at six months after stroke.

Sources: (AFFINITY trial Collaboration, 2020; EFFECTS trial Collaboration, 2020; FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2019; Bembenek 2020) |

3. Self-reported health status (important)

At 6 months

|

Moderate GRADE |

Fluoxetine likely results in little to no difference in self-reported health status when compared to placebo treatment at six months after stroke.

Sources: (AFFINITY trial Collaboration, 2020; EFFECTS trial Collaboration, 2020; FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2019) |

4. Mood (important)

4.1 At 3 months

|

Low GRADE |

Fluoxetine may improve mood in stroke patients when compared to placebo treatment within the first three months after stroke.

Sources: (Chollet, 2011) |

4.2 At 6 months

|

High GRADE |

Fluoxetine improves mood when compared to placebo treatment within the first six months after stroke.

Sources: (AFFINITY trial Collaboration, 2020; EFFECTS trial Collaboration, 2020; FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2019) |

5. Complications (important)

5.1 Bone fractures

At 6 months

|

Moderate GRADE |

Fluoxetine likely results in an increase of bone fractures when compared to placebo treatment within the first six months after stroke.

Sources: (AFFINITY trial Collaboration, 2020; EFFECTS trial Collaboration, 2020; FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2019) |

5.2 Uncontrolled diabetes

At 6 months

|

Moderate GRADE |

Fluoxetine likely results in a decreased incidence of uncontrolled diabetes six months when compared to placebo treatment within the first 6 months after stroke.

Sources: (AFFINITY trial Collaboration, 2020; EFFECTS trial Collaboration, 2020; FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2019) |

5.3 Epileptic seizures

At 3 months

|

Low GRADE |

Fluoxetine may enhance incidence of epileptic seizures three months after treatment in stroke patients, compared to placebo treatment.

Sources: (Chollet, 2011; Marquez-Romero, 2013; He, 2016) |

At 6 months

|

Very low GRADE |

We are uncertain about the effect of fluoxetine on epileptic seizures six months after stroke when compared to placebo treatment.

Sources: (AFFINITY trial Collaboration, 2020; EFFECTS trial Collaboration, 2020; FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2019) |

5.4 Falls with injury

At 6 months

|

Moderate GRADE |

Fluoxetine likely increases the number of falls with injury six months after treatment in stroke patients, compared to placebo treatment.

Sources: (AFFINITY trial Collaboration, 2020; FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2019) |

5.5 Hyponatremia

At 3 months

|

Low GRADE |

Fluoxetine may result in little to no difference in hyponatraemia incidence when compared to placebo treatment three months after stroke. Sources: (Chollet, 2011) |

At 6 months

|

Low GRADE |

Fluoxetine may increase incidence of hyponatremia when compared to placebo treatment within the first six months after stroke.

Sources: (AFFINITY trial Collaboration, 2020; EFFECTS trial Collaboration, 2020; FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2019) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The Cochrane systematic review of Legg (2019) describes the effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) on stroke recovery. In total 63 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), comprising 9168 participants were included in the review, comparing different SSRIs with placebo treatment. To answer our clinical question, only the data of three studies comparing fluoxetine treatment with placebo treatment was extracted from this review (Chollet, 2011; Marquez-Romero, 2013; He, 2016). 31 studies used other SSRIs than fluoxetine. Two studies did not meet our inclusion criteria (Birchenall, 2018; Pariente, 2001). 25 studies did not report relevant outcome measures. One study was already included as a separate RCT (FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2018) and will be explained in the next paragraph.

Phase II trials

Chollet (2011) describes a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, including 118 patients who had ischaemic stroke and hemiplegia or hemiparesis. Patients in the FLAME trial were allocated to two groups between 5 days and 10 days after onset. The two groups were well balanced in terms of baseline and demographic characteristics and stroke severity. However, mean age was slightly higher (66.4 versus 62.9) and previous history of stroke was more frequent in the fluoxetine group than in the control group (17% versus 7%). FMSS score at inclusion was higher in the fluoxetine group (17.1 ± 11.7) than in the placebo group (13.4 ± 8.8), but the study controlled for this in the analyses. The experimental group received 20 mg fluoxetine and the control group received placebo orally once daily for 90 days. All patients received physiotherapy during the treatment period. The effects were evaluated on patients’ motor recovery, global activities of daily living, mood, epileptic seizures and hyponatremia at 3 months.

Marquez-Romero (2013) describes a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial, including 86 adult patients with acute intracerebral haemorrhage. Patients were allocated to two groups 0 and 10 days after onset. The experimental group received 20 mg fluoxetine and the control group received placebo orally once daily for 90 days. The effects were evaluated on patients’ motor recovery and activities of daily living.

He (2016) describes a randomized controlled single-blind clinical study, including 350 participants afflicted with ischaemic stroke. Patients were allocated to two groups within one week after onset. The experimental group received 20 mg fluoxetine and the control group received placebo orally once daily for 90 days. The effects were evaluated on number of patients with epileptic seizures within six months after allocation.

Asadollahi (2018) describes a double-blind placebo controlled randomized controlled trial. A total of 90 patients with acute ischaemic stroke, hemiplegia or hemiparesis were randomly allocated to one of the three groups: fluoxetine, citalopram and placebo. To answer our clinical question, we compared the effects of the fluoxetine group (n=30) and the placebo (n=30) group. The fluoxetine group received 20 mg/day fluoxetine. The placebo group received microcrystalline cellulose. Patients were treated for 90 days. The effects were evaluated on patients’ motor recovery after three months follow-up.

Bembenek (2020) describes a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study based on the FOCUS trial protocol. A total of 61 ischaemic or haemorhagic stroke patients with persisting neurological deficit, measured with the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), were randomly assigned between two and 15 days after stroke onset. The experimental group received 20 mg fluoxetine and the control group received a placebo once daily for six months. The effects were evaluated on patients’ global activities of daily living, self-reported health status and mood after 12 months follow-up.

Phase III and IV trials

The FOCUS Collaboration trial (2018) describes a pragmatic double-blind randomized controlled trial. A total of 3127 adult patients with a clinical diagnosis of acute intracerebral haemorhage or ischaemic stroke including a normal brain scan) and focal neurological deficits participated and were allocated to two groups between 2 days and 15 days after onset. The experimental group received 20 mg fluoxetine and the control group received matching placebo orally once daily for 6 months. The effects were evaluated on patients’ motor recovery, global activities of daily living, self-reported health status, mood, falls with injury, epileptic seizures, bone fractures and hyponatremia at 6 months.

The AFFINITY Collaboration trial (2020) describes a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. A total of 1280 adult patients with a clinical diagnosis of acute ischaemic or intracerebral haemorrhage within the previous 2-15 days and focal neurological deficits participated and were allocated to two groups between 2 days and 15 days after onset. The experimental group received 20 mg fluoxetine and the control group received matching placebo orally once daily for 6 months. The effects were evaluated on patients’ motor recovery, global activities of daily living, self-reported health status, falls with injury, epileptic seizures, bone fractures and hyponatremia at 6 months.

The EFFECTS Collaboration trial (2020) describes a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. A total of 1500 adult patients with a clinical diagnosis of acute ischaemic or intracerebral haemorrhage within the previous 2-15 days and focal neurological deficits participated and were allocated to two groups between 2 days and 15 days after onset. The experimental group received 20 mg fluoxetine and the control group received matching placebo orally once daily for 6 months. The effects were evaluated on patients’ motor recovery, global activities of daily living, self-reported health status, epileptic seizures, bone fractures, hyponatremia and uncontrolled diabetes at 6 months.

Results

1. Motor recovery (crucial)

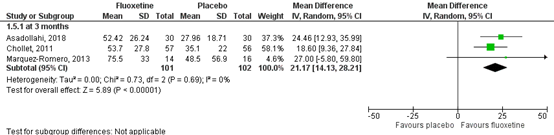

Motor recovery was assessed by the motor deficit score (Fugl-Meyer Motor Score; FMMS). Results for the included studies are shown in a forest plot (Figure 1). 2 RCTs from the systematic review of Legg (2019) (Chollet, 2011; Marquez-Romero, 2013) and one RCT (Asadollahi, 2018) reported motor recovery at three months, comprising 101 patients. Data resulted in a mean difference of 21.17 (95% CI: 14.13 to 28.21), favoring fluoxetine. This difference was clinically relevant.

Level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence in the literature regarding the outcome motor recovery at three months started at high, because it was based on randomized controlled trials, but was downgraded by two levels due to limited number of included patients (imprecision, -2). The overall level is low.

Figure 1 Forest plot for the effect of fluoxetine when compared to placebo or conventional therapy on outcome of motor recovery measured at 3 months

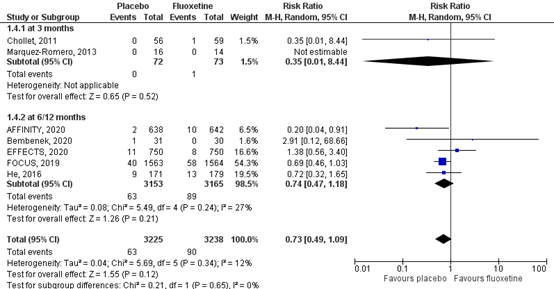

2. Global activities of daily living (crucial)

2.1 At 3 months

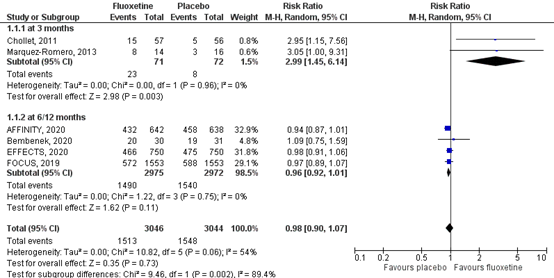

Global activities of daily living were assessed by the number of participants scoring ‘independent’ on the mRS score, meaning a score of 0 to 2 out of a maximum score of six. Results for the included studies are shown in a forest plot (Figure 2). Two RTCs in the review of Legg (2019) (Chollet, 2011; Marquez-Romero, 2013) reported global activities of daily living at three months, comprising 31 patients. Data resulted in a RR of 2.99 (95% CI: 1.45 to 6.14), favoring fluoxetine. This difference was clinically relevant.

2.2 At 6/12 months

Three RCTs (FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2018; AFFINITY trial Collaboration, 2020; EFFECTS trial Collaboration, 2020) reported global activities of daily living following the mRS at six months and one RCT reported global activities of daily living of daily living at 12 months, comprising 3127 patients. Data resulted in a RR of 0.96 (95% CI: 0.92 to 1.01), favoring placebo. This confidence interval does not cross the boundary of clinical relevance at both sides, indicating no difference between the two groups in terms of mRS.

The level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome global activities of daily living started at high as it was based on randomized controlled trials. At three months the level of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to limited number of included patients (imprecision, -2). The overall level is low. At six months, the level of evidence was not downgraded. The overall level is high.

Figure 2 Forest plot for the effect of fluoxetine on global independency (mRS 0 to 2) or dependency including death (mRS 3 to 6) when compared with placebo measured at three, six and 12 months

3. Self-reported health status (important)

Self-reported health status was assessed by using the mean score of the following domains of the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS): Strength, hand ability, mobility and daily activities. Four RTCs (FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2018; AFFINITY trial Collaboration, 2020; EFFECTS trial Collaboration, 2020; Bembenek, 2020) assessed self-reported health status, comprising 5968 patients. Neither of the studies showed a difference between fluoxetine and placebo treatment. Results are shown in Table 1. Since data was not equally distributed, these results could not be pooled in a forest plot.

Table 1 Effect of fluoxetine in self-reported health status, assessed with the four domains of the SIS. Values are expressed as median (interquartile range)

|

|

Fluoxetine |

Placebo |

Significance |

|

FOCUS trial, 2018 |

56.8 (IQR: 30.4-84.3) |

58.8 (IQR: 30.6-84.1) |

p=0.52 |

|

AFFINITY trial, 2020 |

85.5 (IQR: 66.2-94.9) |

83.8 (IQR: 63.4-93.8) |

p=0.24 |

|

EFFECT trial, 2020 |

76.7 (IQR: 56.3-90.2) |

77.4 (IQR: 55.5-91) |

p=0.81 |

|

Bembenek, 2020 |

68.78 (IQR: 49.50-72.22) |

66.11 (IQR: 46.56-73.65) |

p=0.88 |

Level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome self-reported health status at six months started at high as it was based on randomized controlled trials but was downgraded by two levels due to study heterogeneity (imprecision, -1). The overall level is moderate.

4. Mood (important)

4.1 At 3 months

Mood was assessed by the MADRS score or the number of patients experiencing depression. One phase II trial, comprising 118 patients, assessed depression at three months (Chollet, 2011) and reported a mean difference of -3.0 (95% CI: -5.47 to -0.53) of the MADRS score, favoring fluoxetine. However, this difference was not clinically relevant.

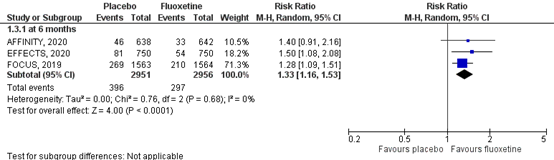

4.2 At 6 months

Three phase III trials assessed depression at six months (FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2018; AFFINITY trial Collaboration, 2020; EFFECTS trial Collaboration, 2020) by the number of depressed patients, comprising 5907 patients. Data resulted in a RR of 1.33 (95% CI: 1.16 to 1.53), favoring fluoxetine. Results for the included studies reporting the number of depressions at 6 months are shown in a forest plot (Figure 4). Overall, the pooled difference of fluoxetine compared to placebo was statistically significant and clinically relevant.

Level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence regarding depression started at high as it was based on randomized controlled trials. At three months, the level of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to limited number of included patients (imprecision, -2). The overall level is low. At six months, the level of evidence was not downgraded. The overall level is high.

Figure 4 Forest plot for the effect of fluoxetine on the number of new depressions within 6 months

5. Complications (important)

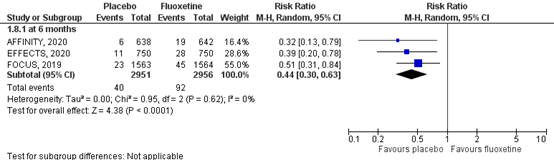

5.1 Bone fractures

Bone fractures were assessed by the number of individuals who had bone fractures during follow-up. Results of the studies are showed in a forest plot (Figure 5). Three RCTs (FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2018; AFFINITY trial Collaboration, 2020; EFFECTS trial Collaboration, 2020), comprising 5907 patients, assessed the number of bone fractures at six months. Data resulted in a RR of 0.44 (95% CI: 0.30to 0.63), favoring placebo. Overall, the pooled difference of risk for bone fractures disfavoring use of fluoxetine was statistically significant and clinically relevant.

Level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence regarding the complication bone fractures started at high as it was based on randomized controlled trials but was downgraded by one level due to low number of events (imprecision, -1). The overall level is moderate.

Figure 5 Forest plot for the effect of fluoxetine on bone fractures within six months post stroke

5.2 Uncontrolled diabetes

Uncontrolled diabetes was assessed by the number of individuals who had uncontrolled diabetes at the end of follow-up. One RCT, comprising 1500 patients, assessed the number of participants with uncontrolled diabetes at six months (EFFECTS trial Collaboration, 2020). Data resulted in a RR of 3.00 (95% CI: 1.10 to 8.21), favoring fluoxetine. Overall, the summary effects size favoring fluoxetine was statistically significant and clinically relevant.

Level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence regarding the complication uncontrolled diabetes started at high as it was based on a randomized controlled trial but was downgraded by one level due to low number of events and only one study reporting on the outcome uncontrolled diabetes (imprecision, -1). The overall level is moderate.

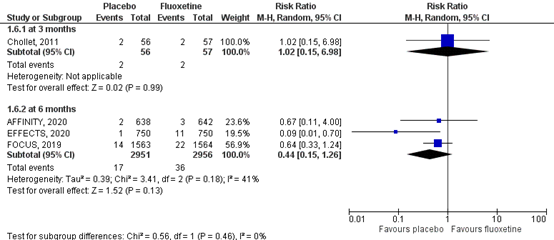

5.3 Epileptic seizures

Epileptic seizures were assessed by the number of individuals who had epileptic seizures during follow-up. Results of the studies are showed in a forest plot (Figure 6). Two RCTs reported epileptic seizures at three months (Chollet, 2011; Marquez-Romero, 2013), comprising 145 patients. Data resulted in a RR of 0.35 (95% CI: 0.01 to 8.44) and a Risk Difference of -0.01 (95% CI: -0.06 to 0.03), favoring placebo. This difference was not statistically significant and therefore not considered clinically relevant. Four RCTs reported the number of epileptic seizures at six months and one RCT reported the number of epileptic seizures at 12 months (FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2018; AFFINITY trial Collaboration, 2020; EFFECTS trial Collaboration, 2020; He, 2016; Bembenek, 2020), comprising 6318 patients. Data resulted in a RR of 0.74 (95% CI: 0.47 to 1.18), favoring placebo. This difference was not statistically significant and therefore not considered clinically relevant. Overall, the pooled effect resulted in a RR of 0.73 (95%CI: 0.49 to 1.09), favoring placebo. This difference was not statistically significant and therefore not clinically relevant.

Level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence in the literature regarding the complication epileptic seizures started at high as it was based on randomized controlled trials. At three months, the level of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to limited number of included patients and low number of events (imprecision, -2). The overall level is low. At six months, the level of evidence was downgraded by two levels duo to crossing the borders of clinical relevance and low number of events (imprecision, -2). The overall level is low.

Figure 6 Forest plot for the effect of fluoxetine when compared to placebo or conventional therapy on the incidence of epileptic seizures within three months and at six months

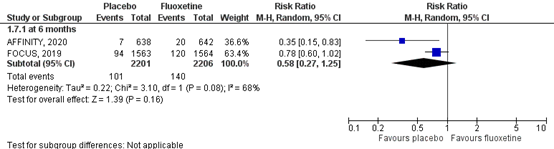

5.4 Falls with injury

Falls with injury was assessed by the number of individuals who had falls with injury during follow-up. Results of the studies are shown in a forest plot (Figure 7). Two RCTs assessed the number of falls with injury at six months (FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2019; AFFINITY trial collaboration), comprising 4407 patients. Data resulted in an incidence of falls with injuries of 140/2206 (6.3%) in the fluoxetine group, compared to 101/2201 (4.6%) in the placebo group. This corresponds to a RR of 0.58 (95% CI: 0.27 to 1.25) in favor of placebo. This difference was clinically relevant.

The level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence regarding the complication falls with injury at six months started at high as it was based on randomized controlled trials but was downgraded by one level due to crossing the borders of clinical relevance and low number of events (imprecision, -1). The overall level is moderate.

Figure 7 Forest plot for the effect of fluoxetine when compared to placebo on the risk of falls with injury at six months

5.5 Hyponatraemia

Hyponatremia was assessed by the number of individuals who had hyponatremia at the end of follow-up. Results of the studies are showed in a forest plot (Figure 8). One RTC in the review (Legg, 2019) reported hyponatremia at three months (Chollet 2011), comprising 113 patients. Data resulted in a RR of 1.02 (95% CI: 0.15 to 6.98), favoring fluoxetine. This difference was not clinically relevant. Three RTCs reported hyponatremia at six months (FOCUS trial Collaboration, 2018; AFFINITY trial Collaboration, 2020; EFFECTS trial Collaboration, 2020), comprising 5907 patients. Hyponatremia was differently defined in all studies. FOCUS trial Collaboration (2018) and EFFECTS trial collaboration (2020) defined hyponatremia as blood sodium < 125 mmol/L, while the AFFINITY trial collaboration (2020) defined hyponatremia as blood sodium < 130 mmol/L. Data resulted in a RR of 0.44 (95% CI: 0.15 to 1.26), favoring placebo. The difference was clinically relevant, but the confidence interval crossed the border of clinical relevance.

Level of evidence in the literature

The level of evidence following GRADE regarding the complication hyponatremia was high based on three phase II/IV randomized controlled trials. At three months, the level of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to limited number of included patients and low number of events (imprecision, -2). The overall level is low. At six months, the level of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to crossing the borders of clinical relevance and low number of events (imprecision, -2). The overall level is low.

Figure 8 Forest plot for the effect of fluoxetine on hyponatremia when compared to placebo measured at three months and at six months

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the effects of fluoxetine on motor recovery, global activities of daily living, self-reported health status, mood and complications in patients after stroke?

P: stroke patients with at least one (focal) neurological deficit;

I: treatment with fluoxetine;

C: treatment with placebo and/or usual care;

O: motor recovery, global activities of daily living, self-reported health status, mood

and complications.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered motor recovery and global activities of daily living as critical outcome measures for decision making; and self-reported health status, mood and complications as important outcome measures for decision making.

Definitions

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

1. Motor recovery: Fugl-Meyer Motor Score (FMMS, range 0 to 100).

2. Global activities of daily living: modified Rankin Scale (mRS, range 0 to 6).

3. Self-reported health status: Stroke Impact Scale (SIS) physical functioning: strength, hand ability, mobility and daily activities (range 0 to 100).

4. Mood: Montgomery Åsberg depression rating scale (MADRS) score (range 0 to 60) or the number of patients taking antidepressant medication or were diagnosed with depression by the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9).

5. Complications: Epileptic seizures, hyponatraemia, falls with injury, bone fractures and uncontrolled diabetes.

For each outcome measure, the working group defined a ‘clinically important difference’. In case of dichotomous outcomes this was based on a calculated risk ratio (RR). For continuous outcomes, the clinically important difference was based on a mean difference (MD) if studies used the same outcome measure and pooling was possible. In case of pooling of different outcomes measuring the same underlying construct, the clinically important difference was based on a standardized mean difference (SMD).

1. Motor recovery: a difference of 10% on the FMMS (RR: ≤ 0.91 of ≥ 1.1; MD: ≤ -10 of ≥ 10).

2. Global activities of daily living: a difference between fluoxetine and placebo (or no medication) group of 1 point on the mRS or a difference in proportion of 10% between the fluoxetine or placebo group (or no medication) in terms of a favourable (mRS 0 to 2) or unfavourable outcome (mRS: 3 to 6) (RR: ≤ 0.91 of ≥ 1.1; MD: ≤ -10 of ≥ 10).

3. Self-reported health status: a difference of 10% on the stroke specific, self-reported, health measure assessed with the SIS physical functioning (RR: ≤ 0.91 of ≥ 1.1; MD: ≤ -10 of ≥ 10).

4. Mood: a difference of 6 points on the MADRS score or a proportional difference of 10% in number of depressions between fluoxetine and placebo or no medication group (RR: ≤ 0.91 of ≥ 1.1; MD: ≤ -6 of ≥ 6).

5. Complications: a statistically significant difference disfavouring fluoxetine treatment when compared to placebo or no medication group

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2010 until the 1st of February 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 94 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: RCTs, randomized trials with cross-over design, including at least 10 participants per treatment arm and treatment with 20mg fluoxetine.

15 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, nine studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and six studies were included.

Results

Six studies were included in the analysis of the literature, including one systematic review (Legg, 2019). Data from three phase I and phase II studies were extracted from the review and included in our analysis (Chollet, 2011, n=118; Marquez-Romero, 2013; n=86; He, 2016, n=360). Furthermore, five RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature, including three recent phase III and phase IV trials (FOCUS Collaboration trial 2018, n=3127; AFFINITY Collaboration trial 2020, n=1280; EFFECTS Collaboration trial 2020, n=1500) and two fase II trials (Asadollahi, 2018, n=90; Bembenek, 2020, n=90). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- AFFINITY Trial Collaboration. Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional outcome after acute stroke (AFFINITY): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020 Aug;19(8):651-660. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30207-6. PMID: 32702334.

- Asadollahi M, Ramezani M, Khanmoradi Z, Karimialavijeh E. The efficacy comparison of citalopram, fluoxetine, and placebo on motor recovery after ischemic stroke: a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2018 Aug;32(8):1069-1075. doi: 10.1177/0269215518777791. Epub 2018 May 21. PMID: 29783900.

- Bembenek JP, Niewada M, Kłysz B, Mazur A, Kurczych K, Głuszkiewicz M, Członkowska A. Fluoxetine for stroke recovery improvement - the doubleblind, randomised placebo-controlled FOCUS-Poland trial. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2020;54(6):544-551. doi: 10.5603/PJNNS.a2020.0099. Epub 2020 Dec 29. PMID: 33373036.

- Chollet F, Tardy J, Albucher JF, Thalamas C, Berard E, Lamy C, Bejot Y, Deltour S, Jaillard A, Niclot P, Guillon B, Moulin T, Marque P, Pariente J, Arnaud C, Loubinoux I. Fluoxetine for motor recovery after acute ischaemic stroke (FLAME): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2011 Feb;10(2):123-30. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70314-8. Epub 2011 Jan 7. Erratum in: Lancet Neurol. 2011 Mar;10(3):205. PMID: 21216670.

- EFFECTS Trial Collaboration. Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional recovery after acute stroke (EFFECTS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020 Aug;19(8):661-669. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30219-2. PMID: 32702335

- FOCUS Trial Collaboration. Effects of fluoxetine on functional outcomes after acute stroke (FOCUS): a pragmatic, double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2019 Jan 19;393(10168):265-274. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32823-X. Epub 2018 Dec 5. PMID: 30528472; PMCID: PMC6336936.

- He YT, Tang BS, Cai ZL, Zeng SL, Jiang X, Guo Y. Effects of Fluoxetine on Neural Functional Prognosis after Ischemic Stroke: A Randomized Controlled Study in China. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016 Apr;25(4):761-70. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.11.035. Epub 2016 Jan 25. PMID: 26823037.

- Ng KL, Gibson EM, Hubbard R, Yang J, Caffo B, O'Brien RJ, Krakauer JW, Zeiler SR. Fluoxetine Maintains a State of Heightened Responsiveness to Motor Training Early After Stroke in a Mouse Model. Stroke. 2015 Oct;46(10):2951-60. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010471. Epub 2015 Aug 20. PMID: 26294676; PMCID: PMC4934654.

- Legg LA, Tilney R, Hsieh CF, Wu S, Lundström E, Rudberg AS, Kutlubaev MA, Dennis M, Soleimani B, Barugh A, Hackett ML, Hankey GJ, Mead GE. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for stroke recovery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Nov 26;2019(11):CD009286. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009286.pub3. PMID: 31769878; PMCID: PMC6953348.

- Marquez-Romero JM, Arauz A, Ruiz-Sandoval JL, Cruz-Estrada Ede L, Huerta-Franco MR, Aguayo-Leytte G, Ruiz-Franco A, Silos H. Fluoxetine for motor recovery after acute intracerebral hemorrhage (FMRICH): study protocol for a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Trials. 2013 Mar 19;14:77. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-77. PMID: 23510124; PMCID: PMC3652770.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

AFFINITY Trial Collaboration, 2020 |

Type of study:

Setting and country: Funded by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria: N total at baseline: Intervention: 642 Control: 638

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 63,5 ± 12,5 C: 64,6 ± 12,2

Sex: I: 64% M C: 62% M

Stroke diagnosis:

Period between stroke and intervention:

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Fluoxetine 20 mg capsules were administered orally, once daily, for 6 months. Serum sodium concentration, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and liver function were measured at the follow-up visit 28 days after randomisation if clinically appropriate. Adherence to trial medication was assessed by asking: “On average, since the last follow-up, how many times per week was the trial medication taken? 0, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, or 7 times per week?” and by pill counts and collection of returned trial bottles. Bottle and pill counts were done by hospital trial pharmacists and entered on a drug accountability form. Any interruption to trial medication was recorded as temporary or permanent, together with the dates and reasons for stopping and restarting. All patients received organised, interdisciplinary care and rehabilitation in stroke units; organised stroke unit care is provided in hospital by nurses, doctors, and therapists who specialise in looking after patients with stroke and work as a coordinated team. |

Matching placebo capsules were administered orally, once daily, for 6 months. Serum sodium concentration, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and liver function were measured at the follow-up visit 28 days after randomisation if clinically appropriate. Adherence to trial medication was assessed by asking: “On average, since the last follow-up, how many times per week was the trial medication taken? 0, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, or 7 times per week?” and by pill counts and collection of returned trial bottles. Bottle and pill counts were done by hospital trial pharmacists and entered on a drug accountability form. Any interruption to trial medication was recorded as temporary or permanent, together with the dates and reasons for stopping and restarting. All patients received organised, interdisciplinary care and rehabilitation in stroke units; organised stroke unit care is provided in hospital by nurses, doctors, and therapists who specialise in looking after patients with stroke and work as a coordinated team. |

Length of follow-up: 6 months.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 30 (4,7%) Reasons:

Control: 17 (2,7 %) Reasons:

Incomplete outcome data: Not applicable.

|

Functionele status (mRS 0 - 6) Defined as the number of participants scoring 0 -2 (independent).

Effect measure: risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p value.

at 6 months: 0.94 (0.87 – 1.01) (p-value = 0.53)

Motor function:

n.r.

Self-reported health status: Defined as the median (IQR) score of 4 domains of the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS).

At 6 months: P value: 0.24

Depression

Effect measure: risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) COMPLICATIONS:

Epileptic seizures: Defined as the number of participants having epileptic seizures.

Effect measure: Risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p-value.

At 6 monts: 4.97 (1.09 – 22.59) (p-value= 0.038)

Hyponatremia (<125 mmol/L) Defined as the number of participants having hyponatremia.

Effect measure: risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p-value.

At 6 months: 1.49 (0.25 – 8.99) (p-value = P value: 1.00)

Fall with injury: Defined as the number of participants having falls with injury.

Effect measure: Risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p -value

At 6 months:

Bone fractures: Defined as the number of participants with bone fractures.

Effect measure: Risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p-value. At 6 months: 3.15 (1.27 – 7.83) (p-value = 0.014)

Epileptic seizures at 6 months: Defined as the number of participants having epileptic seizures.

Effect measure: Risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p-value.

4.97 (1.09 – 22.59) (p-value= 0.038)

Uncontrolled diabetes Defined as the number of participants with uncontrolled diabetes.

n.r. |

Author’s conclusion:

|

|

FOCUS trial collaboration, 2019 |

Type of study:

Setting and country:

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funded by UK Stroke Association and NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme. None of the funding organisations had any role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of this report, or the decision to publish. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 1564

Important prognostic factors2: age (% >70y):

Sex:

Stroke diagnosis:

Period between stroke and intervention:

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Fluoxetine 20 mg was administered to patients orally once daily for 6 months. Patients were supplied with 186 capsules and were prescribed the study medication (20 mg capsules of fluoxetine to be taken daily. Our primary measure of adherence was the best estimate of the interval between the first and last dosebased on all the information available. Therefore, for a particular patient a capsule count might lead us to modify the estimate of the timing of the last dose. |

Placebo was administered to patients orally once daily for 6 months. Patients were supplied with 186 capsules and were prescribed the study medication (20 mg capsules of fluoxetine to be taken daily. Our primary measure of adherence was the best estimate of the interval between the first and last dosebased on all the information available. Therefore, for a particular patient a capsule count might lead us to modify the estimate of the timing of the last dose. |

Length of follow-up: 6 months.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 140 (9,0%)

Control: 140 (9,0%)

Incomplete outcome data: Not applicable

|

Global activities of daily living (mRS 0 - 6) Defined as the number of participants scoring 0 -2 (independent).

Effect measure: risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p value.

At 6 months: 0.97 (0.89 – 1.07) (p-value = 0.439)

Motor recovery:

n.r.

Self-reported health status: Defined as the median (IQR) score of 4 domains of the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS).

At 6 months:

Depression Defined as the number of new depressions.

Effect measure: risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p-value.

At 6 months: 0.78 (0.66 – 0.92) (p-value = 0.0033)

COMPLICATIONS Epileptic seizures Defined as the number of participants having epileptic seizures.

Effect measure: Risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p-value.

At 6 months: 1.45 (0.97 – 2.15) (p-value = 0.0651)

Hypotraemia (<125 mmol/L) Defined as the number of participants having hyponatremia.

Effect measure: risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p-value.

At 6 months: 1.57 (0.79 – 6.49) (p-value = 0.1805)

Fall with injury: Defined as the number of participants having falls with injury.

Effect measure: Risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p -value

At 6 months 1.28 (0.98 – 1.66) (p-value = 0.0663)

Fractured bone: Defined as the number of participants with bone fractures.

Effect measure: Risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p-value.

At 6 months 1.96 (1.19 – 3.22) (p-value = 0.0070)

Uncontrolled diabetes Defined as the number of participants having hypoglyceamia (<3 mmol/L)

Effect measure: Risk ratio (RR) (95% CI)

At 6 months 0.80 (0.16 – 4.12) (p-value = 0.0940) |

Author’s conclusion: |

|

EFFECTS Trial collaboration, 2020 |

Type of study: Trial.

Setting and country:

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Important prognostic factors2: Sex: Stroke diagnosis: Period between stroke and intervention:

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

The intervention was initiated as soon as possible after randomisation. At the local stroke and rehabilitation centre, fluoxetine 20 mg was administered as one oral capsule daily for 6 months. We did not titrate the dose and we recommended the patient take it in the morning. At randomisation, study medication for the first 90 days was dispensed as a bottle of 100 capsules (bottle 1), which included 10 capsules as a reserve in case of delayed follow-up. When the patient was discharged, the trial medication was continued and documented on the discharge summary as well as on the patient’s list of ongoing medication. After up to 7 days before 90 days, the patient was given the last 100 capsules (bottle 2) at a faceto-face follow-up at the same local centre. Patients were instructed to bring bottle 1 to this follow-up. The research nurses counted the capsules returned and recorded this in the case report form. |

The placebo was initiated as soon as possible after randomisation. At the local stroke and rehabilitation centre, matching placebo was administered as one oral capsule daily for 6 months. We did not titrate the dose and we recommended the patient take it in the morning. At randomisation, study medication for the first 90 days was dispensed as a bottle of 100 capsules (bottle 1), which included 10 capsules as a reserve in case of delayed follow-up. When the patient was discharged, the trial medication was continued and documented on the discharge summary as well as on the patient’s list of ongoing medication. After up to 7 days before 90 days, the patient was given the last 100 capsules (bottle 2) at a faceto-face follow-up at the same local centre. Patients were instructed to bring bottle 1 to this follow-up. The research nurses counted the capsules returned and recorded this in the case report form. |

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up

Incomplete outcome data:

Control: 29 (3,9%) |

Global activities of daily living (mRS 0 - 6) Defined as the number of participants scoring 0 -2 (independent).

Effect measure: risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p value.

At 6 months: 0.89 (0.91 – 1.06) (p-value = p=0·42)

Motor recovery: n.r.

Self-reported health status: Defined as the median (IQR) score of 4 domains of the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS).

At 6 months: P value: 0.81

Depression Defined as the number of new depressions.

Effect measure: risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p value.

At 6 months: 0.78 (0.66 – 0.92) Epileptic seizures Defined as the number of participants having epileptic seizures.

Effect measure: Risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p-value.

At 6 months 0.73 (0.29 – 1.80) (p-value = 0.49)

Hyponatremia (<130 mmol/L): Defined as the number of participants having hyponatremia.

Effect measure: risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p-value.

At 6 months: 11.00 (1.42 – 84.99) (p-value =

Fall with injury: Defined as the number of participants having falls with injury.

Bone fractures Defined as the number of participants with bone fractures.

Effect measure: Risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p-value.

At 6 months 2.55 (1.28 – 5.08) (p-value = 0.0058)

Uncontrolled diabetes: n.r. |

Author’s conclusion: |

|

Asadollahi, 2018 |

Type of study: placebo-controlled randomized controlled trial

Setting and country: with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. |

Inclusion criteria - hemiplegia/ hemiparesis after first=time acute ischemic stroke within past 24 hours

Exclusion criteria

N total at baseline:

Important prognostic factors2: Sex: FMMS at baseline (± SD) Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Group A received 20 mg PO of fluoxetine daily, The duration of the therapy was 90 days. In addition to the medications, all of the participants received physiotherapy.

Group B received 20 mg PO of citalopram daily, but this group was not included in the analysis. |

Group C received placebo (microcrystalline cellulose) PO daily. The duration of the therapy was 90 days. In addition to the medications, all of the participants received physiotherapy. |

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up Incomplete outcome data: |

Global activities of daily living (mRS 0 - 6) n.r.

Motor recovery:

At 3 months:

Self-reported health status: n.r.

Depression n.r.

Epileptic seizures n.r.

Hyponatremia (<130 mmol/L): n.r.

Fall with injury:

Bone fractures n.r.

Uncontrolled diabetes: n.r. |

Author’s conclusion: that, at least in the short term, selective serotonin inhibitors are beneficial for improving post-stroke motor recovery. But the long-term risks or benefits of this treatment are not completely elucidated, and further prospective studies are necessary to exactly determine the consequences of using different types of selective serotonin inhibitors in acute ischemic stroke. |

|

Bembenek, 2020 |

Type of study: randomized placebo-controlled FOCUS-Poland trial

Setting and country: No conflict of interest.

fluoxetine and placebo for this study. Anna Członkowska, Jan Bembenek, and Katarzyna Kurczych were supported by statutory activity of the Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology, Warsaw, Poland. |

Inclusion criteria The ability to randomise the patient 2-15 days from the onset of stroke and the presence of persisting focal neurological deficit at randomisation. The deficit had to be severe enough to justify fluoxetine treatment from the patient’s or the caregiver’s perspective. All patients signed informed consent.

Exclusion criteria secondary to intracerebral bleeding); current or recent depression (up to one month) requiring treatment with SSRIs. current use of drugs that cause significant interactions with fluoxetine: the use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOi) up to five weeks prior to study enrollment (e.g., phenelzine, isocarboxazide, tranylcypromine, moclobemide, selegiline and rasagiline) or pimozide; high probability that the patient would not be available during follow-up (e.g., another life-threatening illness); being unable to understand spoken or written Polish (e.g., aphasia hindering communication); history of epileptic seizures; history of allergy to fluoxetine; suicide attempt or self-harm. hepatic impairment (ALT > 3 above the upper normal limit) and renal impairment (creatinine > 180 micromol/L).

N total at baseline:

Important prognostic factors2: Sex: Groups comparable at baseline? |

Fluoxetine 20 mg was administered orally once daily for six months. Patients received 186 capsules and were recommended to take the study medication once a day (in the morning). Adherence to the study medication was measured by recording the date of the first and last dose taken and the number of 546 missed doses. Unused capsules were returned. The reasons for stopping the study medication early were recorded. Those patients who developed post-stroke depression during the study period received a higher dose of fluoxetine (40 mg daily instead of 20 mg) or another SSRI was added to fluoxetine. |

Placebo was administered orally once daily for six months. Patients received 186 capsules and were recommended to take the study medication once a day (in the morning). Adherence to the study medication was measured by recording the date of the first and last dose taken and the number of 546 missed doses. Unused capsules were returned. The reasons for stopping the study medication early were recorded. Those patients who developed post-stroke depression during the study period received a higher dose of fluoxetine (40 mg daily instead of 20 mg) or another SSRI was added to fluoxetine. |

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up

Incomplete outcome data: |

Global activities of daily living (mRS 0 - 6) Defined as the number of participants scoring 0 -2 (independent).

Effect measure: risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p value.

At 12 months: 1.09 (0.75 – 1.59)

Motor recovery:

At 6 months:

Self-reported health status: n.r.

Depression n.r.

Epileptic seizures Defined as the number of participants having epileptic seizures.

Effect measure: Risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p-value.

At 12 months

Hyponatremia (<130 mmol/L): n.r.

Fall with injury:

Bone fractures n.r.

Uncontrolled diabetes: n.r. |

Our results add to a growing and consistent body of evidence that does not support the routine use of fluoxetine within six months post-stroke to promote motor recovery and general outcome after stroke. |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors(((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Legg, 2019

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to (July 2018)

A: Chollet, 2011 D: He, 2016 G: Marquez-Romero, 2013 Study design: Setting and Country: A: France D: China Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Maree L Hackett: during the completion of this work Maree Hackett was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Career Development Fellowship, Population Health (Level 2), APP1141328 (1/1/18-31/12/21) Graeme J Hankey: in the past three years, GJH has a project grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia to lead a trial of fluoxetine for stroke recovery (AFFINITY trial). He has also received honoraria from the American Heart Assocaition for serving |

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

3 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

Number of participants (n): A: I: 59

age ± SD: Sex: Stroke diagnosis: Period between stroke and intervention: Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention:

A: 20 mg fluoxetine; once daily for 3 months. D: 20 mg fluoxetine; once daily for 90 days. G: 20 mg fluoxetine; once daily for 90 days. |

Describe control:

A: Matching placebo. D: Usual care. G: Matching placebo. |

Endpoint of follow-up:

A: 3 months. D: 90 days and 180 days. G: 90 days. For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? A: 5 D: 24 G: 2

|

Global activities of daily living (mRS 0 - 6) Defined as the number of participants scoring 0 -2 (independent).

Effect measure: risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p value.

At 3 months

Motor recovery:

At 3 months:

Self-reported health status: n.r.

Depression Defined by the MADRS score.

Effect measure: mean difference (MD) (95% CI)

A: -3.0 (-5.47 - -0.53)

Epileptic seizures Defined as the number of participants having epileptic seizures.

Effect measure: Risk ratio (RR) (95% CI) and p-value.

At 3 months:

At 6 months:

Hyponatremia (<130 mmol/L): Defined by the number of patients with hyponatremia.

Effect measure: Risk ratio (RR) (95% CI)

Falls with injury:

Bone fractures n.r.

Uncontrolled diabetes: n.r. |

Brief description of author’s conclusion: of bias indicate that SSRIs do not improve recovery from stroke. We identified potential improvements in disability only in the analyses which included trials at high risk of bias. A further meta-analysis of large ongoing trials will be required to determine the generalisability of these findings.

|

Risk-of-bias tabellen

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? a

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?b

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?c

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?d

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?e

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?f

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measureg

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

AFFINITY Trial Collaboration, 2020 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: The allocation sequence was generated by a unique study identification number and treatment pack number corresponding to fluoxetine or placebo in a 1:1 ratio. A minimisation algorithm15 was used to achieve balance between the treatment groups in four predictors of mRS score: time after stroke onset (2–8 versus 9–15 days); presence of a motor deficit (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) questions 5 and 6); presence of aphasia (NIHSS question 9); and probability of survival free of dependency (mRS score 0–2) at 6 months (0·00–0∙15 versus 0∙16–1·00) calculated using a validated prognostic model comprising six baseline variables (age, living alone before the stroke, independent in activities of daily living before the stroke, and able to talk, lift both arms off the bed, and walk unassisted at the time of randomisation). |

Definitely yes;

Reason: The allocation sequence was generated by a secure, password-protected, centralised, webbased randomisation system. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All patients, carers, investigators, and outcome assessors were masked to the allocated treatment by use of placebo capsules that were visually identical to the fluoxetine capsules even when broken open. Success of masking was not assessed. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Follow-up for the primary outcome was high and there was no difference between groups in withdrawals from treatment, minimising the possibility of attrition bias. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Adherence to trial medication was high and similar between treatment groups, which also minimised possible performance bias |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems reported. |

LOW |

|

FOCUS Trial Collaboration, 2019 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive fluoxetine or placebo, by use of a centralised randomisation system. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: the system generated a unique study identification number and a treatment pack number, which corresponded to either fluoxetine or placebo. A minimisation algorithm was used to achieve optimum balance between treatment groups for the following factors: delay since stroke onset (2–8 days versus 9–15 days), computer-generated prediction of 6-month outcome (probability of mRS8 0 to 2 was ≤0∙15 versus >0∙15 based on the six simple variable (SSV) model9), and presence of a motor deficit or aphasia (according to the NIHSS). |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Patients, their families, and the health-care team including the pharmacist, staff in the coordinating centre, and anyone involved in outcome assessments were all masked to treatment allocation by use of a placebo capsule that was visually identical to the fluoxetine capsules even when broken open. An emergency unblinding system was available but was designed so that those in the coordinating centre and those doing follow-up remained masked to treatment allocation. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: There were few losses to follow-up (<1%). |

Definitely yes;

Reason: The primary outcome was global activities of daily living, measured with the mRS, at the 6-month follow-up. We used the simplified mRS questionnaire (smRSq) delivered by post. Among those without a complete postal questionnaire, a telephone interview was done for any further clarification, for completion of missing items, or for the whole questionnaire. Those doing telephone assessments (chief investigators or other staff at the coordinating centre) were trained in their use. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems reported. |

LOW |

|

EFFECTS Trial Collaboration, 2020 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive fluoxetine or placebo, by use of a centralised randomisation system. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: The randomisation system was set up so that the investigator could not see the next assignment in the sequence. The minimisation algorithm randomly allocated the first patient to treatment, with each subsequent patient being allocated to the treatment that led to the least difference between the treatment groups with respect to the prognostic factors. To ensure a random element to treatment allocation, patients were allocated to the group that minimised differences between groups with a probability of 0·8. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Patients, their families, health-care personnel, investigators, outcomes assessors, and staff in the coordinating centre (Karolinska Institute, Department of Clinical Sciences Danderyd Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden), and the pharmacy were masked to treatment allocation. The placebo capsules were visually identical to the fluoxetine capsules, even when broken open. The success of the masking procedure was not assessed. An emergency unmasking system was available but was designed so that the coordinating centre and staff doing follow-up continued to be masked throughout the study. |

Probably yes: |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems reported. |

LOW |

|

Asadollahi, 2018 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: A computer-generated schedule was used by investigators to assign the patients into one of three groups by block randomization: Group A—20 mg P.O. daily of citalopram, Group B—20 mg P.O. daily of fluoxetine, and Group C—a placebo (microcrystalline cellulose). |

No information;

Reason: A computer-generated schedule was used by investigators to assign the patients into one of three groups by block randomization: Group A—20 mg P.O. daily of citalopram, Group B—20 mg P.O. daily of fluoxetine, and Group C—a placebo (microcrystalline cellulose). |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All of the drugs for each group of subjects were over-encapsulated by a pharmacist. All of the patients had physiotherapy sessions (1 hour per day, five days per week) at the same center. |

Probably no;

Reason: Six patients in the fluoxetine group, four patients in the citalopram group, and five patients in the placebo group left the study. The last observation of the patients who left the study was at day 60. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably no;

Reason: Thus, in order to be pragmatic, an intention-to-treat analysis was performed, with the last observation of the patients who did not adhere to the study protocol considered as their final outcome. |

Some concerns (loss to follow-up) |

|

Bembenek, 2020 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either fluoxetine or a placebo, by use of a computer-based permuted block randomisation. Optimum balance between treatment groups was controlled for age (≤ 70 versus > 70 years) and NIHSS (≤ 7 versus > 7).

|

Definitely yes;

Reason: Clinicians involved in randomisation and outcome assessments, the patients, and their families, were all masked so as to be unaware of treatment allocation. The placebo capsules were visually identical to the fluoxetine capsules, even when broken open. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Clinicians involved in randomisation and outcome assessments, the patients, and their families, were all masked so as to be unaware of treatment allocation. The placebo capsules were visually identical to the fluoxetine capsules, even when broken open. |

Probably yes;

Reason: The proportion of our patients who completed 6-month follow-up visits was high (88.5%) and acceptable. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems reported. |

LOW |

- Randomization: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomization process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomization (performed at a site remote from trial location). Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomization procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments, but this should not affect the risk of bias judgement. Blinding of those assessing and collecting outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignment influences the process of outcome assessment or data collection (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is usually not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary. Finally, data analysts should be blinded to patient assignment to prevents that knowledge of patient assignment influences data analysis.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up or the percentage of missing outcome data is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up or missing outcome data differ between treatment groups, bias is likely unless the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk is not enough to have an important impact on the intervention effect estimate or appropriate imputation methods have been used.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available (in publication or trial registry), then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- Problems may include: a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used (e.g. lead-time bias or survivor bias); trial stopped early due to some data-dependent process (including formal stopping rules); relevant baseline imbalance between intervention groups; claims of fraudulent behavior; deviations from intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; (the role of the) funding body. Note: The principles of an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

- Overall judgement of risk of bias per study and per outcome measure, including predicted direction of bias (for example favors experimental, or favors comparator). Note: the decision to downgrade the certainty of the evidence for a particular outcome measure is taken based on the body of evidence, i.e. considering potential bias and its impact on the certainty of the evidence in all included studies reporting on the outcome.

|

Study

|

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

|

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

|

Description of included and excluded studies?3

|

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7 |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

|

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

|

|

Legg, 2019 |

Yes. OBJECTIVE: |

Yes. We developed the MEDLINE search strategy with the help of the Cochrane Stroke Group Information Specialist and adapted it for the other databases. |

Yes. The flow of search results for the previous version of the review are reported in Mead 2012. We report details of the search for this update in a PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1). |

Yes. For substantive descriptions of studies see: Characteristics of included studies, characteristics of excluded studies, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification, and Characteristics of ongoing studies. |

Not applicable. |

Yes. Only three of the included trials were at low risk of bias across the key 'Risk of bias' domains |

Unclear. The results of the meta-analysis of the three trials at low risk of bias are applicable to clinical practice, although the meta-analysis is dominated by the UK FOCUS trial which recruited participants from the National Health Service (FOCUS Trial Collaboration 2018). Nevertheless, FOCUS had broad inclusion criteria, and the demographics of those recruited are similar to UK patients with stroke. Chollet 2011 recruited participants from France and Marquez Romero 2013 recruited participants from Mexico. FOCUS Trial Collaboration 2018 included participants with both haemorrhagic and ischaemic stroke, Chollet 2011 recruited participants with ischaemic stroke, and Marquez Romero 2013 recruited participants with haemorrhagic stroke. |

Yes. Publication bias was taken into account but was not identified in the included studies fort his analysis. |

Yes. Maree L Hackett: during the completion of this work Maree Hackett was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Career Development Fellowship, Population Health (Level 2), APP1141328 (1/1/18-31/12/21) Graeme J Hankey: in the past three years, GJH has a project grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia to lead a trial of fluoxetine for stroke recovery (AFFINITY trial). He has also received honoraria from the American Heart Association for serving |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported.

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs).

- Quality for individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table et cetera).

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (for example Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (for example funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (for example Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Exclusietabel

Tabel Exclusie na het lezen van het volledige artikel

|

Auteur en jaartal |

Redenen van exclusie |

|

Mead, 2012 |

Niet full-tekst beschikbaar |

|

Dennis, 2019 |

Verkeerde subgroep analyse uitgevoerd. |

|

Cook, 2019 |

Beschrijft resultaten van FOCUS trial (al geïncludeerd). |

|

Cramer, 2011 |

Verkeerd studiedesign. |

|

He, 2018 |

Verkeerde uitkomstmaten beschreven. |

|

Lundström, 2020 |

Niet full-tekst beschikbaar. |

|

Lundström, 2020 (correctie) |

Correctie op al geëxcludeerde studie. |

|

Mikami, 2011 |

Verkeerde uitkomstmaten gerapporteerd. |

|

Mead, 2019 |

Minder volledig en recent dan de geïncludeerde review van Legg (2019) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 09-01-2023

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 12-09-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2021 een doorstart gemaakt met de multidisciplinaire werkgroep, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met een herseninfarct of hersenbloeding.

Kerngroep

- Dr. B. (Bob) Roozenbeek (voorzitter), neuroloog, Erasmus MC Rotterdam, namens de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie (NVN)

- Prof. dr. R.M. (Renske) van den Berg-Vos, neuroloog, OLVG West Amsterdam, namens de NVN

- Prof. dr. J. (Jeannette) Hofmeijer, neuroloog, Rijnstate ziekenhuis Arnhem, namens de NVN

- Prof. dr. J.M.A. Visser-Meilij, revalidatiearts, UMC Utrecht, namens de VRA

- A.F.E. (Arianne) Verburg, huisarts, namens het Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap (NHG)

- Prof. dr. H.B. (Bart) van der Worp, neuroloog, UMC Utrecht, namens de NVN

- Dr. S.M. (Yvonne) Zuurbier, neuroloog, Amsterdam UMC, namens de NVN

- Prof. dr. W. (Wim) van Zwam, radioloog, Maastricht UMC, namens de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Radiologie (NVvR)

- Prof. dr. G. (Gert) Kwakkel, hoogleraar neurorevalidatie, Amsterdam UMC, namens de Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap foor Fysiotherapie (KNGF)

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. M.L. Molag, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. F. Ham, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Van den Berg-Vos |

Neuroloog |

Geen |

Voorzitter werkgroep CVA van het Transmuraal Platform Amsterdam (betaald d.m.v. vacatiegelden) Lid focusgroep CVA ROAZ Noord-Holland (onbetaald) ‘Medical lead' Experiment Uitkomstindicatoren VWS (namens Santeon) aandoening CVA, via Santeon betaald voor 4 uur per week Projectleider “Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) voor waardegedreven zorg" (SKMS-project met subsidie FMS, betaald d.m.v. vacatiegelden) Projectleider "Regionale auditing voor kwaliteit van zorg bij patiënten met een herseninfarct” (SKMS-project met subsidie FMS , betaald dmv vacatiegelden) Voorzitterschap (namens de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie) van werkgroep CVA van het programma Uitkomstgerichte Zorg ‘Meer inzicht in uitkomsten’ (betaald d.m.v. vacatiegelden) |

Geen |

|

Hofmeijer |

Neuroloog (0,6 fte) |

Hoogleraar universiteit Twente (0,4 fte) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Kwakkel |

Hoogleraar Neurorevalidatie |

Europees Editor NeuroRehabilitation and Neural Repair

|