Interventies gericht op fysieke doelen

Uitgangsvraag

Welke (combinaties van) vormen van fysieke training zijn het meest geschikt om de specifieke fysieke hartrevalidatiedoelen te behalen bij patiënten met hart- en vaatziekten?

Aanbeveling

Maak gebruik van stroomschema’s op basis van de persoonlijke hartrevalidatiedoelen en fysieke capaciteit (bepaald met behulp van een symptoom-gelimiteerde inspanningstest) van de deelnemer aan de hartrevalidatie om een trainingsinterventie vorm te geven.

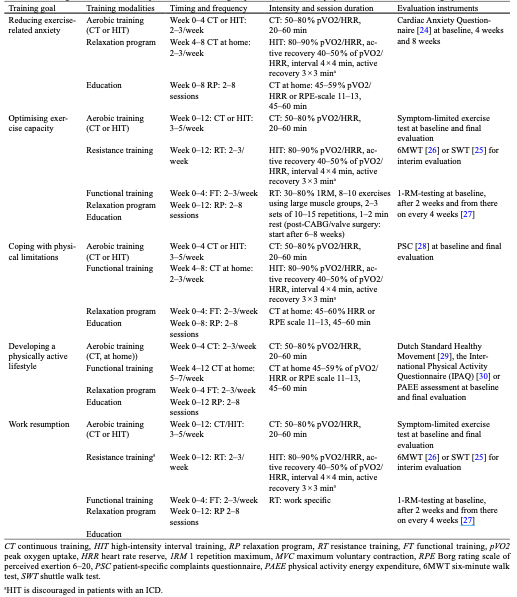

Bepaal de gewenste trainingsvormen, intensiteit, duur en progressie aan de hand van de stroomschema’s (zie tabel 7) en kies bij keuze voor meerdere clusters van hartrevalidatiedoelen voor de meest uitgebreide en intensieve vormen van training.

Pas bij de volgende clusters de genoemde oefenvormen toe:

|

Cluster van doelen |

Oefenvormen |

|

Vermindering van inspanningsgebonden angst |

Aerobe duur- of intervaltraining, ontspanningsoefeningen en beweeginstructie |

|

Optimalisering van het inspanningsvermogen |

Aerobe duur- of intervaltraining, krachttraining, functionele training, ontspanningsoefeningen en beweeginstructie |

|

Leren kennen van fysieke grenzen en omgaan met fysieke beperkingen |

Aerobe duur- of intervaltraining, functionele training, ontspanningsoefeningen en beweeginstructie |

|

Ontwikkelen en onderhouden van een fysieke actieve leefstijl |

Aerobe duur- of intervaltraining, ontspanningsoefeningen en beweeginstructie |

|

Optimale werkhervatting |

Aerobe duur- of intervaltraining, krachttraining, functionele training, ontspanningsoefeningen en beweeginstructie

Voor het individualiseren van de intensiteit (kracht en statische belasting) van de training gerelateerd aan de werkbelasting wordt verwezen naar de NVAB-richtlijn Ischemische hartziekten. |

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Voor deze module wordt gebruik gemaakt van een systematische review en meta-analyse die bij personen met coronaire ziekten hoog-intensieve intervaltraining vergelijkt met matig intensieve duurtraining ten aanzien van fysieke capaciteit (kritieke uitkomstmaat) en kwaliteit van leven (Du 2021). De uitkomstmaten fysieke activiteit, angst, zelfredzaamheid, werkhervatting en rolfunctioneren zijn niet beoordeeld in deze review. Van de fysieke hartrevalidatiedoelen ‘leren kenen van grenzen’, leren omgaan met fysieke beperkingen’, optimaliseren van inspanningsvermogen’, overwinnen van angst voor inspanning’ en ontwikkelen en onderhouden van een actieve leefstijl’ kan alleen ‘optimaliseren van het inspanningsvermogen’ met deze studie worden beoordeeld. Voor de overige fysieke hartrevalidatiedoelen worden de aanbevelingen gebaseerd op een synthese van nationale en Europese richtlijnen en standpunten ten aanzien van fysieke oefenvormen en alle hartrevalidatiedoelen zoals deze in deze richtlijn zijn geformuleerd (Achttien, 2015). Er is uit gegaan van vijf clusters van hartrevalidatiedoelen die met een fysieke interventie zijn te benaderen: 1) vermindering van inspanningsgebonden angst, 2) optimalisering van het inspanningsvermogen, 3) leren kennen van fysieke grenzen en omgaan met fysieke beperkingen, 4) ontwikkelen en onderhouden van een fysieke actieve leefstijl en 5) optimale werkhervatting. Op basis van deze clusters en de karakteristieken van de patiënt wordt een specifiek advies voor de trainingsinterventie gegeven. Verschillende factoren zoals beperkte mentale belastbaarheid of sociale factoren kunnen maken dat genoemde trainingsintensiteit of -frequentie niet haalbaar is.

Tabel 7 Overzicht van aanbevelingen per cluster van beweegdoelen (overgenomen uit Achttien (2015))

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Regelmatige fysieke training kan de algehele gezondheid en het welzijn van patiënten verbeteren door bijvoorbeeld het verminderen van symptomen zoals vermoeidheid en kortademigheid. Patiënten kunnen zich zelfverzekerder en krachtiger voelen door deel te nemen aan fysieke activiteiten, wat hun emotioneel welzijn kan bevorderen.

Sommige patiënten kunnen terughoudend zijn om deel te nemen aan fysieke training uit angst voor verergering van hun symptomen of mogelijke complicaties. Conform module Screening fysieke doelen is hier aandacht voor.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Fysieke training kan helpen bij het verminderen van ziekenhuisopnames en medische kosten op lange termijn door het verbeteren van de algemene gezondheid van de patiënt en het verminderen van de behoefte aan medicatie. Er zijn naar verwachting geen initiële kosten zijn voor het opzetten van programma's voor fysieke training, zoals het inhuren van gespecialiseerde trainers of het aanschaffen van apparatuur, aangezien deze programma reeds ingericht zijn in Nederland.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Aanvaardbaarheid

Patiënten kunnen gemotiveerd zijn om hun behandelingsregime beter te volgen wanneer fysieke training als onderdeel van hun behandeling wordt aanbevolen, vooral als ze de voordelen ervan ervaren. Sommige patiënten kunnen fysieke training niet als een aanvaardbare vorm van behandeling beschouwen vanwege culturele overtuigingen, persoonlijke voorkeuren of gebrek aan interesse. Door de training op maat te geven komt er tegemoet aan eventuele voorkeuren.

Haalbaarheid

Fysieke training kan worden aangepast aan de individuele capaciteiten en behoeften van patiënten, waardoor het haalbaar is voor verschillende niveaus van capaciteit en ernst van de aandoening.

Implementatie

Effectieve implementatie van fysieke training vereist betrokkenheid en ondersteuning van artsen, fysiotherapeuten en andere zorgverleners om patiënten te begeleiden en te motiveren.

Het is belangrijk om een gebalanceerd perspectief te behouden en rekening te houden met de individuele behoeften en omstandigheden van elke patiënt bij het overwegen van fysieke training als onderdeel van de behandeling voor hart- en vaatziekten.

Rationale van de aanbeveling

Belangrijk is een individueel afgestemde benadering van fysieke training als onderdeel van de behandeling voor hart- en vaatziekten. Voordelen van fysieke training omvatten verbeteringen in gezondheid, welzijn, en mogelijk kostenbesparingen op lange termijn. Patiënten kunnen gemotiveerd zijn door positieve ervaringen, maar culturele, persoonlijke, of interesse gerelateerde obstakels kunnen aanvaardbaarheid beïnvloeden. Haalbaarheid wordt benadrukt door aanpassingen aan individuele capaciteiten en ondersteuning van zorgverleners. Implementatie vereist betrokkenheid van medisch personeel.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Interventies gericht op fysieke doelen

Voor interventies die gericht zijn op het behalen van fysieke doelen zijn bewegingsprogramma’s en een ontspanningsprogramma ontwikkeld. Deze kunnen zowel individueel als in een groep worden toegepast. De verwachting is dat de verschillende beweeg gerelateerde hartrevalidatiedoelen (ingedeeld in vijf clusters) verschillende vormen van fysieke training vereisen. Voor deze module is een systematische search uitgevoerd om de effectiviteit van (combinaties van) verschillende vormen van fysieke training op cardiovasculaire, fysieke en psychische uitkomstmaten te onderzoeken.

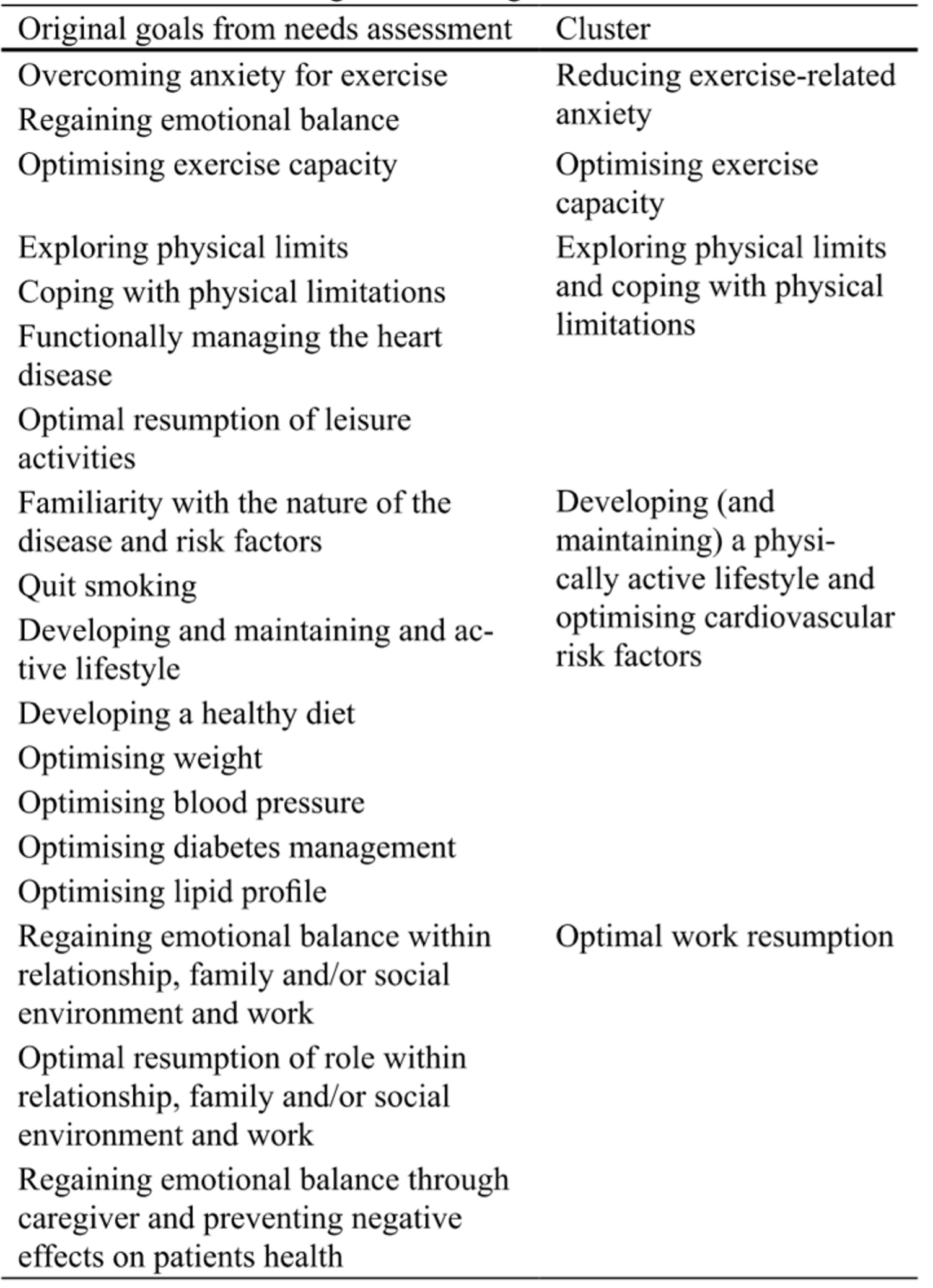

Tabel 1 Overzicht van doelen en bijbehorend cluster

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Fitness

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear what the effect is of high-intensity interval training on fitness, compared to moderate-intensity continuous training in patients with coronary artery disease, without impaired left ventricular ejection fraction or heart failure.

Sources: Du, 2021 |

Quality of life

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear what the effect is of high-intensity interval training on quality of life, compared to moderate-intensity continuous training in patients with coronary artery disease, without impaired left ventricular ejection fraction or heart failure.

Sources: Du, 2021 |

Mortality, cardiovascular disease, hospitalization, physical activity, weight, anxiety, depression, self-efficacy, resumption of work and role functioning

|

- GRADE |

Due to lack of data, no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of HIT compared to MICT on mortality, cardiovascular disease, hospitalization, physical activity, weight, anxiety, depression, self-efficacy, resumption of work and role functioning in patients with coronary artery disease, without impaired left ventricular ejection fraction or heart failure.

Sources: Du, 2021 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Du (2021) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the physical health benefits of High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), compared to moderate-intensity continuous training (MCIT) in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), without impaired Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF) or heart failure. Several databases were searched up to December 2020, including PubMed, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus, Cochrane Library and CNKI. Du (2021) included 25 eligible RCTs with a total of 1272 patients. Data of 1002 males and 201 females were included (gender not reported: N=69). The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool. Table 3 lists more details of the interventions that were applied in the included studies. Duration of exercise ranged from four to 16 weeks, with a frequency of two to three times a week. Drop-out ranged from 0% to 38% (HIT) and 0% to 28% (MICT).

Table 3 Description of the interventions that were applied in the studies in Du (2021).

|

Author, year |

N (M/F) |

Disease |

HIT |

MICT |

Duration and frequency |

|

Abdelhalem, 2018 |

H: 18M/2F Mi: 16M/4F |

CAD |

40–45 min: 1: 5 min WU 2: 2–5 min at 95% of HR reserve 3: 2–5 min 40–60% of HR reserve 4: 5 min CD |

40–45 min: 1: 5 min WU 2: 30–35 min exercise at 40–60%of HR reserve 3: 5min CD |

12 weeks, 2 days a week |

|

Amundsen, 2008 Rognmo, 2004 |

H: 6M/2F Mi: 8M/1F |

CAD |

33 min: 1: 5 min WU at 50–60% of VO2peak (65–75% of HRpeak) 2: 4×4 min intervals at 80–90 % of VO2peak (85–95% HRpeak) 3: 3×3 min pauses at 50–60% of VO2peak 4: 3 min CD at 50–60% of VO2peak |

41 min: 41 min exercise at 50–60% of VO2peak |

10 weeks, 3 days a week |

|

Cardozo, 2015 |

H: 15M/5F Mi: 16M/8F |

CAD |

40 min: 1: 5 min WU 2: 8×2 min intervals at 90% of peak HR 3: 7×2 min pauses at 60% of peak HR 4: 5 min CD |

40 min: 1: 5 min WU 2: 30 min exercise at 70 to 75% of peak HR 3: 5 min CD |

16 weeks, 3 days a week |

|

Choi, 2018 |

H: 21M/2F Mi: 18M/3F |

MI |

48 min: 1: 10 minutes of stretching, 5 min WU at 40%–50% of HRpeak 2: 4×4 min intervals at 85%–100% of HRpeak 3: 4×3 min pauses at 50%–60% of HRpeak 4: 5 min CD at 40%–50% of HRpeak |

48 min: 1: 10 minutes of stretching, 5 min WU at 40%–50% of HRpeak 2: 28 min exercise at 60%–70% of HRpeak 3: 5 min CD at 40%–50% of HRpeak |

9–10 weeks, 1– 2 days a week |

|

Conraads, 2015; Pattyn, 2017; Van de Heyning, 2018 |

H: 81M/4F Mi: 80M/9F |

CAD |

38 min: 1: 10 min WU at 50–60% of VO2peak (60–70% of HRpeak) 2: 4 ×4 min intervals at 85–90% of VO2peak (90–95% of HRpeak) 3: 4×3 min pauses at 50%–70% of VO2peak |

47 min: 1: 5 min WU at 50–60% of VO2peak (60–70% of HRpeak) 2: 37 min exercise at 60%–70% of VO2peak (65–75% of HRpeak) 3: 5 min CD at 50–60% of VO2peak (60–70% of HRpeak) |

12 weeks, 3 days a week |

|

Currie, 2013A |

H: 7M Mi: 7M |

CAD |

49–54 min: 1: 10–15 min WU and CD 2: 10×1 min intervals at 80%-99% of PPO at week 1–4 3: 10×1 min intervals at 105% ± 12% of PPO at week 5- 8 4: 10×1 min intervals at 107% ± 12% of PPO at week 9- 12 5: 9×1 min pauses at 10% of PPO |

40–65 min: 1: 10–15 min WU and CD 2: 30 min exercise at 55–65% of PPO for week 1–4 3: 40 min exercise at 55–65% of PPO for week 5–8 4: 50 min exercise at 55–65% of PPO for week 9–12 |

12 weeks, 2 days a week |

|

Currie, 2013B |

H: 10M/1F Mi: 10M/1F |

CAD |

49–54 min: 1: 10–15 min WU and CD 2: 10×1 min intervals at 89% of PPO for week 1–4 3: 10×1 min intervals at 102% of PPO for week 5- 8 4: 10×1 min intervals at 110% of PPO for week 9- 12 5: 9×1 min pauses at 10% of PPO |

40–65 min: 1: 10–15 min WU and CD 2: 30 min exercise at 51–65% of PPO for week 1–4 3: 40 min exercise at 51–65% of PPO for week 5–8 4: 50 min exercise at 51–65% of PPO for week 9–12 |

12 weeks, 2 days a week |

|

Eser, 2020 |

H: N=34 Mi: N=35 |

MI |

36 min: 1: 8 min WU at 0 to VT1 2: 4 ×4 min intervals at VT2 3: 3×3 min pauses at 0 to VT1 4: 3 min CD at 0 to VT1 |

38 min: 1: 5 min WU at 50% of VT1 2: 30 min exercise at VT1 3: 3 min CD at 50% of VT1 |

12 weeks, 3 days a week |

|

Ghardasi-Afousi, 2018 |

H: 14M Mi: 14M |

CABG |

50 min: 1: 5 min WU at 0 to 40% of HRpeak 2: 10×2 min intervals at 85–95% of HRpeak 3: 10×2 min pauses at 50% of HRpeak 4: 5 min WU at 40% of HRpeak |

50 min: 1: 5 min WU at 0 to 40% of HRpeak 2: 40 min running at 70% of HRpeak 3: 5 min WU at 50% of HRpeak |

6 weeks, 3 days a week |

|

Jaureguizar, 2016; Jaureguizar, 2019 |

H: 28M/8F Mi: 33M/3F H: 50M/7F Mi: 42M/11F |

IHD |

40 min: 1: 12, 10, 7, 5 min WU at 25 watt for week 1, 2, 3, 4–8 week respectively 2: 15×20s intervals at 50% of PPO with 15×40s pauses at of 10% of PPO (reached in the first SRT) for week 1 3: 20×20s intervals at 50% of PPO with 20×40s pauses at 10% of PPO (reached in the first SRT) for week 2 4: 25×20s intervals at 50% of PPO with 25×40s pauses at 10% of PPO (reached in the first SRT) for week 3 5: 30×20s intervals at 50% of PPO with 30×40s pauses at 10% of PPO (reached in the first SRT) for week 4 6: 30×20s intervals at 50% of PPO with 30×40s pauses at 10% of PPO (reached in the second SRT) for week 4 7: 13, 10, 8, 5 min WU at 25 watt for week 1, 2, 3, 4–8 week respectively |

40 min: 1: 12, 10, 7, 5 min WU at 25 watt for week 1, 2, 3, 4–8 respectively 2: 15, 20, 25, 30 min exercise at VT1 for week 1–4 3: 30 min exercise at (VT1 + 10%) for week 5–8 4: 13, 10, 8, 5 min WU at 25 watt for week 1, 2, 3, 4–8 week respectively |

8 weeks, 3 days a week |

|

Keteyian, 2014 |

H: 11M/5F Mi: 12M/1F |

CAD |

40 min: 1: 5 min WU 2: 4×4 min intervals at 80–90% of HR reserve 3: 3×5 min pauses at 60–70% of HR reserve 4: 4 min CD |

40 min: 1: 5 min WU 2: 30 min exercise at 60–80% of HR reserve 3: 5 min CD |

10 weeks, 3 days a week |

|

Kim, 2015 |

H: 12M/2F Mi: 10M/4F |

AMI |

45 min: 1: 10 min WU at 50–70% HR reserve 2: 4×4 min intervals at 85–95% HR reserve 3: 3×3 min pauses at 50–70% HR reserve 4: 10 min CD at 50–70% HR reserve |

45 min: 1: 10 min WU 2: 25 min walking at 70–85% HR reserve 3: 10 min CD |

6 weeks, 3 days a week |

|

Moholdt, 2009 |

H: 24M/4F Mi: 24M/7F |

CABG |

38 min: 1: 8 min WU 2: 4×4 min intervals at 90% of HRpeak 3: 3×3 min pauses at 70% of HRpeak 4: 5 min CD |

46min: 46 min walking at 70% of HRpeak |

4 weeks, 5 days a week |

|

Moholdt, 2012 |

H: 25M/5F Mi: 49M/10F |

MI |

38 min: 1: 8 min WU 2: 4×4 min intervals at 85–95% of HRpeak 3: 3×3 min pauses at 70% of HRpeak 4: 5 min CD |

50 min: 1: 10 min WU 2: 35 min walking, jogging, lunges and squats 3: 5 min CD |

12 weeks, 3 days a week |

|

Prado, 2016 |

H: 14M/3F Mi: 14M/4F |

CAD |

52 min: 1: 5 min WU 2: 7×3 min intervals at RCP 3: 7×3 min pauses at AT 4: 5 min CD |

60 min: 1: 5 min WU 2: 50 min exercise at AT 3: 5 min CD |

12 weeks, 3 days a week |

|

Reed, 2021 |

H: 36M/7F Mi: 38M/6F |

CAD |

38 min: 1: 5 min WU at 60–70% of HRpeak 2: 4×3 min intervals at 85–95% of HRpeak (RPE 15–18) 3: 7×3 min pauses at 60–70% of HRpe |

60 min: 1: 10–15 min WU at 60–70% of HRpeak 2: 10–15 min exercise (walking or jogging, cycling, elliptical, rowing) for week 1–3 3: 30 min exercise (walking or jogging, cycling, elliptical, rowing) for week 4–12 4: 15 min CD |

12 weeks, 2 days a week |

|

Taylor, 2020 |

H: 39M/7F Mi: 39M/8F |

CAD |

25 min: 1: 4×4 intervals at RPE 15–18 2: 3×3 min pauses at RPE 11–13 |

40 min: 40 min exercise at RPE 11–13 |

4 weeks, 3 days a week |

|

Trachsel, 2019 |

H: 15M/8F Mi: 15M/3F |

ACS |

38–50 min: 1: 5 min WU at 30% PPO 2: 2–3 sets of 6–10 minutes with repeated bouts of 15–30s at 100% of PPO alternating with 15 to 30s of passive recovery 3: 5-minute active recovery phase at 30% of PPO between sets 4: 5 min CD at 30% PPO |

34 min: 1: 5 min WU at 30% of PPO 2: 24 min exercise at 60% of PPO 3: 5 min CD at 30% of PPO |

12 weeks, 2– 3 days a week |

|

Warburton, 2005 |

H: 7M Mi: 7M |

CAD |

50 min: 1: 10 min WU 2: 8×2 min intervals at 85–95% of HR/VO2 reserve 3: 7×2 min intervals at 35–45% of HR/VO2 reserve 4: 10 min CD |

50 min: 1: 10 min WU 2: 30 min exercise at 65% of HR/VO2 reserve 3: 10 min CD |

16 weeks, 2 days a week |

|

Ye, 2020 |

H: 43M/17F Mi: 40M/20F |

Stroke + CAD |

45 min: 1: 5 min WU 2: 10×3 min intervals at 80% of PPO 3: 10×1 min of passive |

45 min: 1: 5 min WU 2: 40 min cycling at 60% of PPO |

12 weeks, 3 days a week |

|

Gao, 2015 |

H: 18M/4F Mi: 16M/5F |

PCI |

50 min: 1: 5 min WU 2: 10×3 min intervals at 80% of PPO 3: 10×1 min of passive recovery 4: 5 min CD |

50 min: 1: 5 min WU 2: 40 min cycling at 60% of PPO 3: 5 min CD |

2 weeks, 3 days a week |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; MI, myocardial infarction; IHD, ischemic heart disease; PCI, percutaneous transluminal coronary intervention; H: High-intensity interval training; Mi: moderate intensity continuous training; F, female; M, male; WU, warm-up; CD, cool-down; PPO, peak power output; HR, heart rate; HRpeak, peak heart rate; VO2peak, peak oxygen uptake; RPE, rating of perceived exertion; VT1, first ventilatory threshold; VT2, second ventilatory threshold; AT, anaerobic threshold; SRT, steep ramp test; RCP, respiratory compensation point.

Results

Du (2021) did not report on the outcome measures mortality, cardiovascular disease, hospitalization, physical activity, weight, anxiety, depression, self-efficacy, resumption of work and role functioning.

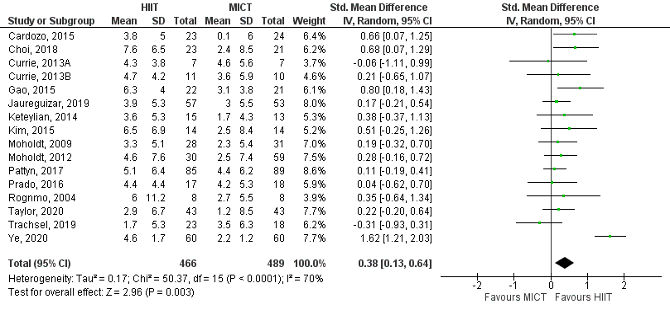

Fitness

Du (2021) reported on the outcome measure VO2peak, which was studied in 16 of the included trials. Standardized mean difference (95%CI) in changes in VO2peak between the HIIT group (N=466) and the MICT group (N=489) was 0.38 (0.13 to 0.64), in favour of the HIIT group (Figure 4). This difference was considered as a small clinically relevant difference.

Figure 4 Changes in VO2peak between high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), without impaired left ventricular ejection fraction or heart failure. Adapted from Du (2021).

Quality of life

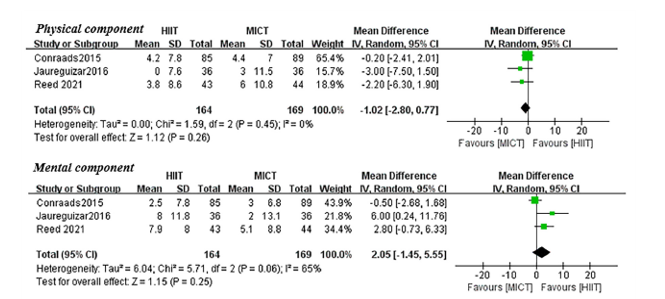

Du (2021) reported on the outcome measure QoL, which was studied in five of the included RCTs. They used various instruments to evaluate changes in QoL. Two RCTs used the SF-36, one RCT the SF-12 and three RCTs the MacNew tool. The results are depicted in Figure 5 and 6.

SF-36 and SF-12

Mean difference (95%CI) in changes on the physical component between the HIIT group (N=164) and the MICT group (N=169) was -1.02 (-2.80 to 0.77), in favor of the MICT group (Figure 5a). This difference corresponds to a standardized mean difference (95%CI) of -0.14 (-0.35 to 0.08), which was not considered clinically relevant. Mean difference (95%CI) in changes on the mental component between the HIIT group (N=164) and the MICT group (N=169) was 2.05 (-1.45 to 5.55), in favour of the MICT group (Figure 5b). This difference corresponds to a standardized mean difference (95%CI) of 0.21 (-0.14 to 0.55), which was considered as a small clinically relevant difference.

Figure 5 Differences in changes in QoL as evaluated with the SF-36 or SF-12 (physical component and mental component) between high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) in patients with coronary artery disease, without impaired left ventricular ejection fraction or heart failure. Adapted from Du (2021).

MacNew tool

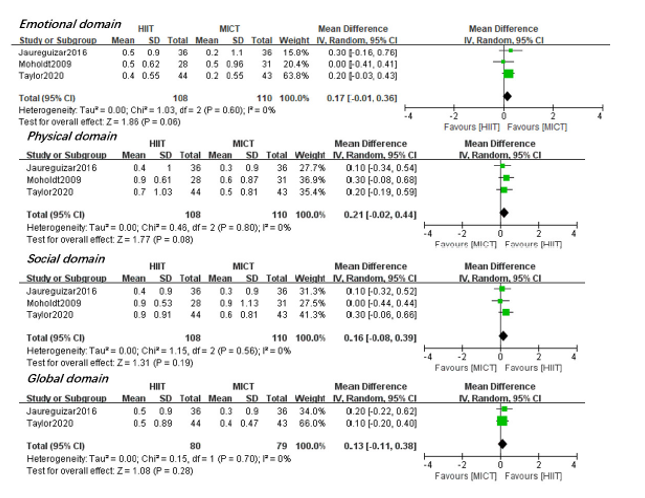

Mean difference (95%CI) in changes on the emotional domain between the HIIT group (N=108) and the MICT group (N=110) was 0.17 (-0.01 to 0.36) in favor of the MICT group (Figure 6a). This difference corresponds to a standardized mean difference (95%CI) of 0.24 (-0.03 to 0.51), which was considered as a small clinically relevant difference.

Mean difference (95%CI) in changes on the physical domain between the HIIT group (N=108) and the MICT group (N=110) was 0.21 (-0.02 to 0.44) in favor of the HIIT group (Figure 6b). This difference corresponds to a standardized mean difference (95%CI) of 0.22 (-0.04 to 0.49), which was considered as a small clinically relevant difference.

Mean difference (95%CI) in changes on the social domain between the HIIT group (N=108) and the MICT group (N=110) was 0.16 (-0.08 to 0.39) in favor of the HIIT group (Figure 6c). This difference corresponds to a standardized mean difference (95%CI) of 0.17 (-0.09 to 0.44), which was not considered clinically relevant.

Mean difference (95%CI) in changes on the global domain between the HIIT group (N=80) and the MICT group (N=79) was 0.13 (-0.11 to 0.38) in favor of the HIIT group (Figure 6d). This difference corresponds to a standardized mean difference (95%CI) of 0.18 (-0.14 to 0.49), which was not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 6a-d: Differences in changes in QoL as evaluated with the MacNew tool between high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) in patients with coronary artery disease, without impaired left ventricular ejection fraction or heart failure. Adapted from Du (2021).

Level of evidence of the literature

Du (2021) did not report on the outcome measures mortality, cardiovascular disease, hospitalization, physical activity, weight, anxiety, depression, self-efficacy, resumption of work and role functioning. Therefore, no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of HIT compared to MICT on those outcome measures in patients with CAD, without LVEF and heart failure.

Fitness

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure fitness was downgraded to very low. There was risk of bias (e.g. unclear randomization process and/or allocation concealment, deviation from intended interventions, missing outcome data, high drop-out rate which differed between the study groups, blinding was not possible, and females accounted for only one fifth of the total sample size, downgraded two levels). Furthermore, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, downgraded two levels). Finally, it is not clear whether all interventions were applied in the context of a cardiac rehabilitation program. This led to reduced applicability of the results (indirectness, downgraded one level).

Quality of life

The evidence comes for the outcome measure quality of life comes from RCTs and therefore started at high certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was risk of bias (e.g., unclear randomization process and/or allocation concealment, high drop-out rate which differed between the study groups, blinding was not possible, and females accounted for only one fifth of the total sample size, downgraded two levels). Furthermore, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed (one of) the thresholds for clinical relevance (downgraded one level). Finally, it is not clear whether all interventions were applied in the context of a cardiac rehabilitation program. This led to reduced applicability of the results (indirectness, downgraded one level).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effectiveness of resistance training, endurance training, interval training or functional training or a combination, in patients with an indication for cardiac rehabilitation?

Table 2 PICO

|

Patients |

patients with an indication for cardiac rehabilitation (for patients with heart failure, please see the KNGF guideline) |

|

Intervention |

resistance training, endurance training, interval training or functional training (or a combination of) |

|

Control

|

see intervention |

|

Outcomes |

all-cause mortality cardiovascular disease (defined as percutaneous transluminal coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass grafting or acute coronary syndrome) hospitalization for cardiovascular disease fitness physical activity weight anxiety depression self-efficacy return to work quality of life role functioning |

|

Other selection criteria |

Study design: systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered physical activity, self-efficacy, return to work, role functioning, anxiety, and cardiorespiratory fitness as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and all-cause mortality, CVD, hospitalization, QoL, weight, and depression as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the other outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined 2% points absolute difference in a 10-year period as a minimal clinically important difference for the outcome measure mortality.

The working group defined 1 ml/min/kg in absolute difference as a minimal clinically important difference for the outcome measure cardiorespiratory fitness.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until December 15th 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 1004 hits. Studies were selected based on the PICO (see table). 118 potential systematic reviews were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 117 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and a systematic review (Du, 2021) was included.

Results

One study was included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Achttien RJ, Vromen T, Staal JB, Peek N, Spee RF, Niemeijer VM, Kemps HM; multidisciplinary expert panel. Development of evidence-based clinical algorithms for prescription of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation. Neth Heart J. 2015 Dec;23(12):563-75.

- Du, L., Zhang, X., Chen, K., Ren, X., Chen, S., & He, Q. (2021). Effect of High-Intensity Interval Training on Physical Health in Coronary Artery Disease Patients: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 8(11), 158.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Du, 2021

Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR. |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to December 2020.

A: Abdelhalem, 2018 B: Amundsen, 2008 C: Rognmo, 2004 D: Cardozo, 2015 E: Choi, 2018 F: Conraads, 2015 G: Pattyn, 2017 H: Van De Heyning, 2018 I:Currie, 2013A J: Currie, 2013B K: Eser, 2020 L: Ghardasi-Afousi, 2018 M: Jaureguizar, 2016 N: Jaureguizar, 2019 O: Keteyian, 2014 P: Kim, 2015 Q: Moholdt, 2009 R: Moholdt, 2012 S: Prado, 2016 T: Reed, 2021 U: Taylor, 2020 V: Trachsel, 2019 W: Warburton, 2005 X: Ye, 2020 Y: Gao, 2015

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: America (N=8), Asia (N=5), Australia (N=1), Africa (N=1), Europe (40% of the trials).

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: SR was funded by Ministry of Education of Humanities and Social Science Project and the Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong University. Funding of individual studies not reported. |

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs compared the effectiveness of HIIT with MICT in participants with CAD without impaired LVEF; Intervention duration lasted for at least 4 weeks; At least one of the following outcomes were measured: VO2peak, peak O2 pulse, anaerobic threshold, the ventilatory efficiency slope, oxygen uptake efficiency slope, respiratory exchange ratio, peak power, peak heart rate, resting heart rate, heart rate recovery at 1 min, total Cholesterol, HDL-C, LDL-C, triglycerides, fasting blood glucose, resting SBP, resting DBP, QoL, LVEF, LVEDD, LVESD, LVEDV, LVESV; Written in English or Chinese.

Exclusion criteria SR: non-randomized or uncontrolled, cross-sectional studies; unpublished documents, dissertations; conference papers

25 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: For data on N, sex and age in individual studies, see Table 1 in Du (2021).

N Total:1272 HIIT: 621 MICT: 651

Sex: Total M: 1002 Total F: 201 Gender not reported: 69

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

For details on the interventions in the individual studies, see supplement of Du (2021), p3-p6.

|

For details on the interventions in the individual studies, see supplement of Du (2021), p3-p6.

|

End-point of follow-up: Duration of the interventions ranged from 4 to 16 weeks. For details on individual studies, see supplement of Du (2021), p3-p6.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Drop-out ranged from 0% to 38% in HIIT-group en 0 to 28% in MICT-group. For details on drop-out rate in individual studies, see Du (2021), Table 1.

|

Changes in VO2peak Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): 1.92 (1.30 to 2.53) favoring HIIT. Heterogeneity (I2): 9%

Changes in Anaerobic threshold Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): 0.59 (0.07 to 1.10) favoring MICT Heterogeneity (I2): 13%

Changes in Peak Power Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): 10.86 (7.63 to 14.09) favoring HIIT Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Changes in VE/VCO2 slope Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): -0.13 (-0.35 to 0.08) favoring MICT Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Changes in OUES Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): 0.09 (-0.12 to 0.29) favoring MICT Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Changes in Peak O2 pulse Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): 0.34 (-0.45 to 1.13) favoring MICT Heterogeneity (I2): 7%

Changes in resting heart rate Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): -1.10 (-2.52 to 0.32) favoring MICT Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Changes in peak heart rate Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): 2.20 (-0.47 to 4.88) favoring HIIT Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Changes in HRR1 min Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): -1.21 (-3.87 to 1.45) favoring MICT Heterogeneity (I2): 62%

Changes in respiratory exchange ratio Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): 0.00 (-0.01 to 0.02) favoring n.a. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Quality of life Physical component Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): -1.02 (-2.80 to 0.77) favoring MICT Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Mental component Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): 2.05 (-1.45 to 5.55) favoring HIIT Heterogeneity (I2): 65%

Emotional domain Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.17 (-0.01 to 0.36) favoring MICT Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Physical domain Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): 0.21 (-0.02 to 0.44) favoring HIIT Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Social domain Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): 0.16 (-0.08 to 0.39) favoring HIIT Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Global domain Pooled effect (95%CI, random effects model): 0.13 (-0.11 to 0.38) favoring HIIT Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Also reported: changes in resting blood pressure, changes in blood lipids, changes in fasting blood glucose, changes in left ventricular functioning and remodelling.

|

Authors conclusion This meta-analysis suggested that HIIT is superior to MICT in improving VO2peak, VO2 at AT and peak power in CAD patients. The optimal HIIT protocol in improving VO2peak might be those with mediate to longer intervals and higher work/rest ratios; it seemed that the efficacy of HIIT over MICT in improving VO2peak may not be influenced by intervention duration and training mode. In addition, the total energy consumption of exercise protocols determined the difference in VO2peak gain induced by HIIT and MICT, with the isocaloric protocol inducing similar effects. Both HIIT and MICT did not significantly influence resting BP, however, MICT seemed to be more effective in reducing resting SBP and DBP than HIIT. HIIT and MICT equally significantly improved HRrest, HRpeak, HRR 1min, OUES, LVEF%, QoL, while had no significant influence on VE/VCO2, peak O2 pulse, RER, and blood lipids. Further higher quality, large-sample, multicenter, long-term randomized interventional studies are needed to assess the effects of HIIT and MICT in CAD patients.

Remarks - females only accounted for about one-fifth of the total sample size; - drop-out rate was high in part of the studies and was different between the treatment groups (not consistent in all of the included studies);

Subgroup analysis - intervention duration (<12 weeks vs ≥ 12 weeks) - duration of HIIT interval (≤1 min, 1-3 min and ≥4 min) - Work/rest ratio (≤1 vs >1) - Energy consumption (isocaloric vs not isocaloric) - exercise mode (treadmill, cycle ergometer, others) For details and results, see supplement of Du (2021), p7. |

|

Fan, 2021

Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR. |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to December 2020.

A total of 38 trials were included. For details, see Fan, 2021.

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: America (N=8), Asia (N=5), Australia (N=1), Egypt (N=1), Europe (40% of the trials).

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: SR was funded by Ministry of Education of Humanities and Social Science Project and the Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong University. Funding of individual studies not reported. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Budnick K, Campbell J, Esau L, Lyons J, Rogers N, Haennel RG. Cardiac rehabilitation for women: a systematic review. Canadian journal of cardiovascular nursing = Journal canadien en soins infirmiers cardio-vasculaires. 2009;19(4):13-25. |

Wrong population (only women) |

|

Cornish AK, Broadbent S, Cheema BS. Interval training for patients with coronary artery disease: A systematic review. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2011;111(4):579-89. |

Included also non-RCTs |

|

Marzolini S, Oh PI, Brooks D. Effect of combined aerobic and resistance training versus aerobic training alone in individuals with coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. 2012;19(1):81-94. |

SR, published in 2012 |

|

Sandercock G, Hurtado V, Cardoso F. Changes in cardiorespiratory fitness in cardiac rehabilitation patients: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Cardiology. 2013;167(3):894-902. |

Wrong intervention (cardiac rehabilitation, no focus on exercise) |

|

Ismail H, McFarlane JR, Nojoumian AH, Dieberg G, Smart NA. Clinical Outcomes and Cardiovascular Responses to Different Exercise Training Intensities in Patients With Heart Failure. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC: Heart Failure. 2013;1(6):514-22. |

Wrong comparison (different training intensities) |

|

Jewiss D, Ostman C, Smart NA. The effect of resistance training on clinical outcomes in heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Cardiology. 2016;221:674-81. |

Wrong population (CHF with HFrEF) |

|

Yamamoto S, Hotta K, Ota E, Mori R, Matsunaga A. Effects of resistance training on muscle strength, exercise capacity, and mobility in middle-aged and elderly patients with coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cardiology. 2016;68(2):125-34. |

Wrong population (middle aged and elderly patients) |

|

Liou K, Ho S, Fildes J, Ooi SY. High Intensity Interval versus Moderate Intensity Continuous Training in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: A Meta-analysis of Physiological and Clinical Parameters. Heart Lung and Circulation. 2016;25(2):166-74. |

More recent review available |

|

Uddin J, Zwisler AD, Lewinter C, Moniruzzaman M, Lund K, Tang LH, et al. Predictors of exercise capacity following exercise-based rehabilitation in patients with coronary heart disease and heart failure: A meta-regression analysis. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2016;23(7):683-93. |

Wrong study design and wrong outcome (focus on predictors of exercise capacity) |

|

Pearson MJ, Smart NA. Aerobic Training Intensity for Improved Endothelial Function in Heart Failure Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiology Research and Practice. 2017;2017. |

Wrong comparison (different training intensities, control group is non-exercising patients) |

|

Ostman C, Jewiss D, Smart NA. The Effect of Exercise Training Intensity on Quality of Life in Heart Failure Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiology (Switzerland). 2017;136(2):79-89. |

Wrong comparison (different training intensities) |

|

Hollings M, Mavros Y, Freeston J, Fiatarone Singh M. The effect of progressive resistance training on aerobic fitness and strength in adults with coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2017;24(12):1242-59. |

More recent review available |

|

Xanthos PD, Gordon BA, Kingsley MIC. Implementing resistance training in the rehabilitation of coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Cardiology. 2017;230:493-508. |

More recent review available |

|

raal JJ, Vromen T, Spee R, Kemps HMC, Peek N. The influence of training characteristics on the effect of exercise training in patients with coronary artery disease: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. International Journal of Cardiology. 2017;245:52-8. |

Wrong comparison (training versus usual care), focus on role of several training characteristics on outcome |

|

Palmer K, Bowles K-A, Paton M, Jepson M, Lane R. Chronic Heart Failure and Exercise Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2018;99(12):2570-82. |

Wrong intervention (sole structured exercise program) |

|

Zhang Y, Qi L, Xu L, Sun X, Liu W, Zhou S, et al. Effects of exercise modalities on central hemodynamics, arterial stiffness and cardiac function in cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(7). |

Wrong comparison (comparison between exercise training and non-exercise training) |

|

Slimani M, Ramirez-Campillo R, Paravlic A, Hayes LD, Bragazzi NL, Sellami M. The effects of physical training on quality of life, aerobic capacity, and cardiac function in older patients with heart failure: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Physiology. 2018;9. |

Wrong population (older patients with HF) |

|

Hansen D, Niebauer J, Cornelissen V, Barna O, Neunhauserer D, Stettler C, et al. Exercise Prescription in Patients with Different Combinations of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: A Consensus Statement from the EXPERT Working Group. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ). 2018;48(8):1781-97. |

Wrong publication type (consensus statement), wrong population (CVD risk factors) |

|

Gomes Neto M, Durães AR, Conceição LSR, Saquetto MB, Ellingsen Ø, Carvalho VO. High intensity interval training versus moderate intensity continuous training on exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Cardiology. 2018;261:134-41. |

Patients with heart failure |

|

Hannan AL, Hing W, Simas V, Climstein M, Coombes JS, Jayasinghe R, et al. High-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training within cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open access journal of sports medicine. 2018;9:1-17. |

More recent review available |

|

Hansen D, Abreu A, Doherty P, Völler H. Dynamic strength training intensity in cardiovascular rehabilitation: is it time to reconsider clinical practice? A systematic review. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2019;26(14):1483-92. |

wrong comparison (different strength training intensities) |

|

Wang Z, Peng X, Li K, Wu CJJ. Effects of combined aerobic and resistance training in patients with heart failure: A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Nursing & health sciences. 2019;21(2):148-56. |

Wrong comparison (comparison between combined exercise and usual care) |

|

Long L, Mordi IR, Bridges C, Sagar VA, Davies EJ, Coats AJS, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with heart failure. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019;2019(1). |

wrong comparison (exercise-based rehabilitation versus no exercise based) |

|

Ballesta García I, Rubio Arias JÁ, Ramos Campo DJ, Martínez González-Moro I, Carrasco Poyatos M. High-intensity Interval Training Dosage for Heart Failure and Coronary Artery Disease Cardiac Rehabilitation. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Revista Espanola de Cardiologia. 2019;72(3):233-43. |

wrong comparison (different HIT dosages) |

|

Araújo BTS, Leite JC, Fuzari HKB, Pereira De Souza RJ, Remígio MI, Dornelas De Andrade A, et al. Influence of High-Intensity Interval Training Versus Continuous Training on Functional Capacity in Individuals with Heart Failure: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW and META-ANALYSIS. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2019;39(5):293-8. |

Patients with heart failure |

|

Pengelly J, Pengelly M, Lin KY, Royse C, Royse A, Bryant A, et al. Resistance Training Following Median Sternotomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Heart Lung and Circulation. 2019;28(10):1549-59. |

Also included non-RCTs |

|

Mitchell BL, Lock MJ, Davison K, Parfitt G, Buckley JP, Eston RG. What is the effect of aerobic exercise intensity on cardiorespiratory fitness in those undergoing cardiac rehabilitation? A systematic review with meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine. 2019;53(21):1341-51. |

Wrong comparison (focus on different intensities), wrong study design (also included observational studies) |

|

Lee J, Lee R, Stone AJ. Combined Aerobic and Resistance Training for Peak Oxygen Uptake, Muscle Strength, and Hypertrophy After Coronary Artery Disease: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Cardiovascular Translational Research. 2020;13(4):601-11. |

Control group is not clear |

|

de Souza JAF, Araújo BTS, de Lima GHC, Dornelas de Andrade A, Campos SL, de Aguiar MIR, et al. Effect of exercise on endothelial function in heart transplant recipients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Failure Reviews. 2020;25(3):487-94. |

Wrong outcome (endothelial function), wrong population (heart transplant recipients) |

|

Javaherian M, Dabbaghipour N, Mohammadpour Z, Attarbashi Moghadam B. The role of the characteristics of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation program in the improvement of lipid profile level: A systematic review and meta-analysis. ARYA Atherosclerosis. 2020;16(4):192-207. |

Wrong outcome (lipid profile) |

|

Bourscheid G, Just KR, Costa RR, Petry T, Danzmann LC, Pereira AH, et al. Effect of different physical training modalities on peak oxygeconsumptions in post-acute myocardial infarction patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Jornal Vascular Brasileiro. 2021;20. |

Control group could also be no exercise, usual treatment |

|

Qin Y, Kumar Bundhun P, Yuan ZL, Chen MH. The effect of high-intensity interval training on exercise capacity in post-myocardial infarction patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2021. |

Focus on MI patients; included non-RCTs |

|

Boulmpou A, Theodorakopoulou MP, Boutou AK, Alexandrou M-E, Papadopoulos CE, Bakaloudi DR, et al. Effects of different exercise programs on cardiorespiratory reserve in HFpEF: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hellenic journal of cardiology : HJC = Hellenike kardiologike epitheorese. 2021. |

Subgroupanalysis on resistance vs aerobic, HIT vs aerobic |

|

Sadek Z, Ramadan W, Khachfe H, Ajouz G, Baydoun H, Joumaa WH, et al. Meta-analysis on continuous and intermittent aerobic training comparison to assess the optimal exercise model in heart failure patients. Kinesitherapie. 2021;21(239):37-47. |

Other language (french) |

|

Fisher S, Smart NA, Pearson MJ. Resistance training in heart failure patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Failure Reviews. 2021. |

Patients with heart failure |

|

Clark RA, Conway A, Poulsen V, Keech W, Tirimacco R, Tideman P. Alternative models of cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2015;22(1):35-74. |

Wrong intervention (focus on alternative models of cardiac rehabilitation, no focus on exercise) |

|

Taylor-Piliae R, Finley BA. Benefits of Tai Chi Exercise Among Adults With Chronic Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of cardiovascular nursing. 2020;35(5):423-34. |

Wrong intervention (Tai Chi Exercise) |

|

Abreu RM, Rehder-Santos P, Simões RP, Catai AM. Can high-intensity interval training change cardiac autonomic control? A systematic review. Brazilian journal of physical therapy. 2019;23(4):279-89. |

Wrong outcome (cardiac autonomic control) |

|

Cook R, Davidson P, Martin R. Cardiac rehabilitation for heart failure can improve quality of life and fitness. The BMJ. 2019;367. |

Wrong publication type |

|

Lewin RJP, Brodie DA. Cardiac rehabilitation for refractory angina: Part one: An Introduction. British Journal of Cardiology. 2000;7(4):219-21. |

Wrong publication type |

|

Ribeiro GS, Melo RD, Deresz LF, Dal Lago P, Pontes MR, Karsten M. Cardiac rehabilitation programme after transcatheter aortic valve implantation versus surgical aortic valve replacement: Systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2017;24(7):688-97. |

Wrong comparison (focus on the effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation) |

|

Yang YL, Wang YH, Wang SR, Shi PS, Wang C. The effect of Tai Chi on cardiorespiratory fitness for coronary disease rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Physiology. 2018;8. |

Wrong comparsion (comparison between Tai Chi Exercise and other types of low-to moderate intensity/no exercise) |

|

Eijsvogels TMH, Molossi S, Lee DC, Emery MS, Thompson PD. Exercise at the extremes: The amount of exercise to reduce cardiovascular events. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016;67(3):316-29. |

Wrong study design (narrative review), wrong population (no cardiac rehabilitation patients) |

|

Porritt K. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. British journal of community nursing. 2020;25(9):460-1. |

No full tekst available |

|

Taylor RS, Long L, Mordi IR, Madsen MT, Davies EJ, Dalal H, et al. Exercise-Based Rehabilitation for Heart Failure: Cochrane Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Trial Sequential Analysis. JACC Heart failure. 2019;7(8):691-705. |

Wrong comparison (exercise-based programs vs control subjects) |

|

Shephard RJ. A Half-Century of Evidence-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Historical Review. Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine. 2020. |

Wrong study design (historical review) |

|

Perrier-Melo RJ, Figueira FAMS, Guimarães GV, Costa MC. High-intensity interval training in heart transplant recipients: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia. 2018;110(2):188-94. |

Wrong population (heart transplant recipients) |

|

Gomes-Neto M, Saquetto MB, da Silva e Silva CM, Conceição CS, Carvalho VO. Impact of Exercise Training in Aerobic Capacity and Pulmonary Function in Children and Adolescents After Congenital Heart Disease Surgery: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Pediatric Cardiology. 2016;37(2):217-24. |

Wrong population (children and adolescents) |

|

Tang H, Fu Z, Zhang Y, Zhang Y. [Meta-analysis of safety and efficacy on exercise rehabilitation in coronary heart disease patients post revascularization procedure]. Zhonghua xin xue guan bing za zhi. 2014;42(4):334-40. |

Foreign language |

|

Younge JO, Gotink RA, Baena CP, Roos-Hesselink JW, Hunink MGM. Mind-body practices for patients with cardiac disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2015;22(11):1385-98. |

Wrong intervention (mind-body practices) |

|

Bittencourt HS, Cruz CG, David BC, Rodrigues E, Abade CM, Junior RA, et al. Addition of non-invasive ventilatory support to combined aerobic and resistance training improves dyspnea and quality of life in heart failure patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical rehabilitation. 2017;31(11):1508-15. |

Wrong intervention (Non-invasive ventilation) |

|

Fernández-Rodríguez R, Álvarez-Bueno C, Ferri-Morales A, Torres-Costoso AI, Cavero-Redondo I, Martínez-Vizcaíno V. Pilates method improves cardiorespiratory fitness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019;8(11). |

Wrong population (no cardiac rehabilitation patients) |

|

Van Dixhoorn J, White A. Relaxation therapy for rehabilitation and prevention in ischaemic heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. 2005;12(3):193-202. |

Wrong intervention (relaxation therapy) |

|

Harwood AE, Russell S, Okwose NC, McGuire S, Jakovljevic DG, McGregor G. A systematic review of rehabilitation in chronic heart failure: evaluating the reporting of exercise interventions. ESC Heart Failure. 2021;8(5):3458-71. |

Wrong outcome (reporting of exercise interventions) |

|

Gu Q, Wu SJ, Zheng Y, Zhang Y, Liu C, Hou JC, et al. Tai Chi Exercise for Patients with Chronic Heart Failure: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2017;96(10):706-16. |

Wrong comparsion (comparison between Tai Chi Exercise and other types of aerobic exercise/no exercise) |

|

Huang R, Palmer SC, Cao Y, Zhang H, Sun Y, Su W, et al. Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs for Chronic Heart Disease: A Bayesian Network Meta-analysis. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2021;37(1):162-71. |

Wrong comparison (exercise-based rehabilitation vs cardiac rehabilitation) |

|

Ashur C, Cascino TM, Lewis C, Townsend W, Sen A, Pekmezi D, et al. Do Wearable Activity Trackers Increase Physical Activity among Cardiac Rehabilitation Participants? A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW and META-ANALYSIS. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2021;41(4):249-56. |

Wrong intervention (activity trackers) |

|

Li J, Li Y, Gong F, Huang R, Zhang Q, Liu Z, et al. Effect of cardiac rehabilitation training on patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of palliative medicine. 2021;10(11):11901-9. |

|

|

Ramachandran HJ, Jiang Y, Tam WWS, Yeo TJ, Wang W. Effectiveness of home-based cardiac telerehabilitation as an alternative to Phase 2 cardiac rehabilitation of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2021. |

Wrong comparison (home based rehabilitation vs usual care or centre-based cardiac rehabilitation) |

|

Huang J, Qin X, Shen M, Xu Y, Huang Y. The Effects of Tai Chi Exercise Among Adults With Chronic Heart Failure: An Overview of Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2021;8. |

Wrong comparison (Tai chi versus conventional medication alone) |

|

Fan Y, Yu M, Li J, Zhang H, Liu Q, Zhao L, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Resistance Training for Coronary Heart Disease Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. 2021;8:754794. |

|

|

Gonçalves C, Raimundo A, Abreu A, Bravo J. Exercise intensity in patients with cardiovascular diseases: Systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(7). |

Wrong comparison (comparison between different intensities programmes) |

|

Leggio M, Fusco A, Coraci D, Villano A, Filardo G, Mazza A, et al. Exercise training and atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and literature analysis. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2021;25(16):5163-75. |

Wrong comparison (comparison between exercise training and standard therapy or usual care) |

|

Abraham LN, Sibilitz KL, Berg SK, Tang LH, Risom SS, Lindschou J, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults after heart valve surgery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021;2021(5). |

Wrong comparison (comparison between cardiac rehabilitation (exercise) versus no exercise rehabilitation) |

|

Dibben G, Faulkner J, Oldridge N, Rees K, Thompson DR, Zwisler A-D, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2021;11:CD001800. |

Wrong comparison (comparison between cardiac rehabilitation (exercise) versus no exercise rehabilitation) |

|

Kaihara T, Intan-Goey V, Scherrenberg M, Falter M, Frederix I, Dendale P. Impact of activity trackers on secondary prevention in patients with coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2021. |

Wrong intervention (activity trackers) |

|

Guo R, Wen Y, Xu Y, Jia R, Zou S, Lu S, et al. The impact of exercise training for chronic heart failure patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2021;100(13):e25128. |

Wrong comparison (comparison between exercise training and standard therapy or usual care) |

|

Seo YG, Oh S, Park WH, Jang M, Kim HY, Chang SA, et al. Optimal aerobic exercise intensity and its influence on the effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: A systematic review. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2021;13(7):4530-40. |

Wrong comparison (comparison between different intensities programmes) |

|

Taylor JL, Bonikowske AR, Olson TP. Optimizing Outcomes in Cardiac Rehabilitation: The Importance of Exercise Intensity. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. 2021;8:734278. |

Wrong study design (narrative review) |

|

Babu AS, Arena R, Satyamurthy A, Padmakumar R, Myers J, Lavie CJ. Review of Trials on Exercise-Based Rehabilitation Interventions Following Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: OBSERVATIONS FROM THE WHO INTERNATIONAL CLINICAL TRIALS REGISTRY PLATFORM. Journal of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation and prevention. 2021;41(4):214-23. |

Wrong study design (focus on analysis of the protocols of studies in the WHO-ICTRP) |

|

Way KL, Vidal-Almela S, Moholdt T, Currie KD, Aksetøy ILA, Boidin M, et al. Sex Differences in Cardiometabolic Health Indicators after HIIT in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2021;53(7):1345-55. |

Wrong outcome (focus on sex differences) |

|

Manresa-Rocamora A, Sarabia JM, Sánchez-Meca J, Oliveira J, Vera-Garcia FJ, Moya-Ramón M. Are the Current Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs Optimized to Improve Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Patients? A Meta-Analysis. Journal of aging and physical activity. 2020;29(2):327-42. |

Wrong study design (pre-post scores) |

|

Gerlach S, Mermier C, Kravitz L, Degnan J, Dalleck L, Zuhl M. Comparison of Treadmill and Cycle Ergometer Exercise During Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2020;101(4):690-9. |

Wrong comparison (Comparison between treadmill and cycle ergometer, both aerobic training) |

|

Chen L, Tang L. Effects of interval training versus continuous training on coronary artery disease: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2020:1-10. |

More outcomes reported in another review |

|

Meyer M, Brudy L, García-Cuenllas L, Hager A, Ewert P, Oberhoffer R, et al. Current state of home-based exercise interventions in patients with congenital heart disease: A systematic review. Heart. 2019. |

Wrong intervention (focus on home-based exercise interventions) |

|

Cavalcante SL, Lopes S, Bohn L, Cavero-Redondo I, Alvarez-Bueno C, Viamonte S, et al. Effects of exercise on endothelial progenitor cells in patients with cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Revista portuguesa de cardiologia. 2019;38(11):817-27. |

Wrong outcome (endothelial progenitor cells), wrong comparison (no focus on differences in various exercise programmes) |

|

Pengelly J, Pengelly M, Lin KY, Royse C, Karri R, Royse A, et al. Exercise Parameters and Outcome Measures Used in Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs Following Median Sternotomy in the Elderly: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Heart Lung and Circulation. 2019;28(10):1560-70. |

Wrong population (elderly) |

|

Nielsen KM, Zwisler AD, Taylor RS, Svendsen JH, Lindschou J, Anderson L, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adult patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019;2019(2). |

Wrong comparison (comparison between exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation vs no exercise based, usual care or no intervention) |

|

Taylor RS, Walker S, Smart NA, Piepoli MF, Warren FC, Ciani O, et al. Impact of Exercise Rehabilitation on Exercise Capacity and Quality-of-Life in Heart Failure: Individual Participant Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73(12):1430-43. |

Wrong comparison (comparison between exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation vs no exercise based) |

|

Imran HM, Baig M, Erqou S, Taveira TH, Shah NR, Morrison A, et al. Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation Alone and Hybrid With Center-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019;8(16):e012779. |

Wrong comparison (home-based cardiac rehabilitation, hybrid) |

|

Doyle MP, Indraratna P, Tardo DT, Peeceeyen SCS, Peoples GE. Safety and efficacy of aerobic exercise commenced early after cardiac surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2019;26(1):36-45. |

Wrong intervention (exercise within the first two weeks postoperatively) |

|

Seo YG, Jang MJ, Lee GY, Jeon ES, Park WH, Sung JD. What Is the Optimal Exercise Prescription for Patients With Dilated Cardiomyopathy in Cardiac Rehabilitation? A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2019;39(4):235-40. |

Comparison is not clear, non-RCTs were included |

|

Kissel CK, Nikoletou D. Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Prescription in Symptomatic Patients with Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease—a Systematic Review. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2018;20(9). |

Wrong comparison (comparison between cardiac rehabilitation/exercise training versus control groups) |

|

Reed JL, Terada T, Chirico D, Prince SA, Pipe AL. The Effects of Cardiac Rehabilitation in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2018;34(10):S284-S95. |

Wrong comparison (comparison between cardiac rehabilitation versus control groups) |

|

Xia T-L, Huang F-Y, Peng Y, Huang B-T, Pu X-B, Yang Y, et al. Efficacy of Different Types of Exercise-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation on Coronary Heart Disease: a Network Meta-analysis. Journal of general internal medicine. 2018;33(12):2201-9. |

Wrong interventions (home based, centre-based, tele-based etc.) |

|

Long L, Anderson L, Dewhirst AM, He J, Bridges C, Gandhi M, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with stable angina. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;2018(2). |

Wrong comparison (comparison between exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation versus usual care) |

|

Yamamoto S, Hotta K, Ota E, Matsunaga A, Mori R. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for people with implantable ventricular assist devices. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;2018(9). |

Wrong comparison (comparison between exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation versus usual care) |

|

Wewege MA, Ahn D, Yu J, Liou K, Keech A. High-intensity interval training for patients with cardiovascular disease-is it safe? A systematic review. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2018;7(21). |

Wrong comparison (also included usual care as a control group) |

|

Wu C, Li Y, Chen J. Hybrid versus traditional cardiac rehabilitation models: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kardiologia polska. 2018;76(12):1717-24. |

Wrong intervention (focus on home based exercised intervention) |

|

Mahfood Haddad T, Saurav A, Smer A, Azzouz MS, Akinapelli A, Williams MA, et al. Cardiac Rehabilitation in Patients With Left Ventricular Assist Device: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS. Journal of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation and prevention. 2017;37(6):390-6. |

Wrong comparison (comparison between exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation versus usual care) |

|

Karagiannis C, Savva C, Mamais I, Efstathiou M, Monticone M, Xanthos T. Eccentric exercise in ischemic cardiac patients and functional capacity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Annals of physical and rehabilitation medicine. 2017;60(1):58-64. |

Wrong comparison (eccentric vs concentric training) |

|

Risom SS, Zwisler AD, Johansen PP, Sibilitz KL, Lindschou J, Gluud C, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017;2017(2). |

Wrong comparison (comparison between exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation vs no exercise based) |

|

Anderson L, Nguyen TT, Dall CH, Burgess L, Bridges C, Taylor RS. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in heart transplant recipients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017;2017(4). |

Wrong comparison (exercise training vs no exercise training) |

|

Ribeiro PAB, Boidin M, Juneau M, Nigam A, Gayda M. High-intensity interval training in patients with coronary heart disease: Prescription models and perspectives. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2017;60(1):50-7. |

Wrong study design (narrative review) |

|

Claes J, Buys R, Budts W, Smart N, Cornelissen VA. Longer-term effects of home-based exercise interventions on exercise capacity and physical activity in coronary artery disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2017;24(3):244-56. |

Wrong intervention (home-based exercise interventions) |

|

Gomes-Neto M, Saquetto MB, da Silva e Silva CM, Conceição CS, Carvalho VO. Impact of Exercise Training in Aerobic Capacity and Pulmonary Function in Children and Adolescents After Congenital Heart Disease Surgery: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Pediatric Cardiology. 2016;37(2):217-24. |

|

|

Almodhy M, Ingle L, Sandercock GR. Effects of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation on cardiorespiratory fitness: A meta-analysis of UK studies. International Journal of Cardiology. 2016;221:644-51. |

Wrong population (UK studies), wrong outcome (moderators of change in fitness) |

|

Neto MG, Oliveira FA, Dos Reis HFC, De Sousa Rodrigues E, Bittencourt HS, Carvalho VO. Effects of neuromuscular electrical stimulation on physiologic and functional measurements in patients with heart failure a systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2016;36(3):157-66. |

Wrong intervention (neuromuscular electrical stimulation) |

|

Zwisler AD, Norton RJ, Dean SG, Dalal H, Tang LH, Wingham J, et al. Home-based cardiac rehabilitation for people with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Cardiology. 2016;221:963-9. |

Wrong intervention (home-based exercise cardiac rehabilitation) |

|

Price KJ, Gordon BA, Bird SR, Benson AC. A review of guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation exercise programmes: Is there an international consensus? European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2016;23(16):1715-33. |

Wrong study design (review of guidelines) |

|

Ito S, Mizoguchi T, Saeki T. Review of high-intensity interval training in cardiac rehabilitation. Internal Medicine. 2016;55(17):2329-36. |

Wrong study design (narrative review) |

|

Rawstorn JC, Gant N, Direito A, Beckmann C, Maddison R. Telehealth exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2016;102(15):1183-92. |

Wrong intervention (telehealth interventions) |

|

Yang YJ, He XH, Guo HY, Wang XQ, Zhu Y. Efficiency of muscle strength training on motor function in patients with coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 2015;8(10):17536-50. |

|

|

Achttien RJ, Staal JB, van der Voort S, Kemps HM, Koers H, Jongert MWA, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with chronic heart failure: A dutch practice guideline. Netherlands Heart Journal. 2015;23(1):6-17. |

Wrong study design (KNGF guideline) |

|

Anderson L, Taylor RS. Cardiac rehabilitation for people with heart disease: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014(12):CD011273. |

Wrong comparisons (exercise based cardiac rehabilitation vs usual care, home based vs centre based) |

|

Gomes Neto M, Menezes MA, Oliveira Carvalho V. Dance therapy in patients with chronic heart failure: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Clinical rehabilitation. 2014;28(12):1172-9. |

Wrong intervention (dance therapy) |

|

Ismail H, McFarlane JR, Dieberg G, Smart NA. Exercise training program characteristics and magnitude of change in functional capacity of heart failure patients. International Journal of Cardiology. 2014;171(1):62-5. |

Wrong comparison (comparison between exercise programmes with different intensity) |

|

Sandercock GRH, Cardoso F, Almodhy M, Pepera G. Cardiorespiratory fitness changes in patients receiving comprehensive outpatient cardiac rehabilitation in the UK: A multicentre study. Heart. 2013;99(11):785-90. |

Wrong study design (no clinical trial, pre-post measurements) |

|

Soares FHR, de Sousa MBC. Different Types of Physical Activity on Inflammatory Biomarkers in Women With or Without Metabolic Disorders: A Systematic Review. Women and Health. 2013;53(3):298-316. |

Wrong population (women with or without metabolic disorders), wrong outcome (inflammatory markers) |

|

Achttien RJ, Staal JB, van der Voort S, Kemps HMC, Koers H, Jongert MWA, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with coronary heart disease: A practice guideline. Netherlands Heart Journal. 2013;21(10):429-38. |

Wrong study design (KNGF guideline) |

|

Giacomantonio NB, Bredin SSD, Foulds HJA, Warburton DER. A Systematic Review of the Health Benefits of Exercise Rehabilitation in Persons Living With Atrial Fibrillation. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2013;29(4):483-91. |

More recent reviews available |

|

Guiraud T, Nigam A, Gremeaux V, Meyer P, Juneau M, Bosquet L. High-intensity interval training in cardiac rehabilitation. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ). 2012;42(7):587-605. |

Wrong study design (narrative review) |

|

Lawler PR, Filion KB, Eisenberg MJ. Efficacy of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation post-myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. American heart journal. 2011;162(4):571-84.e2. |

Wrong comparison (comparison between exercise based cardiac rehabilitation vs control groups) |

|

Davies EJ, Moxham T, Rees K, Singh S, Coats AJ, Ebrahim S, et al. Exercise based rehabilitation for heart failure. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 2010;4:CD003331. |

Wrong population (patients with heart failure); wrong comparison (comparison between exercise based cardiac rehabilitation vs control groups) |

|

Dalal HM, Zawada A, Jolly K, Moxham T, Taylor RS. Home based versus centre based cardiac rehabilitation: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2010;340:b5631. |

Wrong intervention (home-based exercise cardiac rehabilitation) |

|

Clark AM, Haykowsky M, Kryworuchko J, MacClure T, Scott J, DesMeules M, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized control trials of home-based secondary prevention programs for coronary artery disease. European journal of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation : official journal of the European Society of Cardiology, Working Groups on Epidemiology & Prevention and Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology. 2010;17(3):261-70. |

Wrong intervention (home-based exercise cardiac rehabilitation) |

|

Amundsen BH, Wisloff U, Slordahl SA. [Exercise training in cardiovascular diseases]. Fysisk trening ved hjerte- og karsykdommer. 2007;127(4):446-8. |

Wrong study design (based on guidelines and searches in Pubmed) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 02-10-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 17-09-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met hart- en vaatziekten.

Werkgroep

- Prof. dr. A.W.J. (Arnoud) van ‘t Hof, cardioloog, werkzaam in het Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum te Maastricht en Zuyderland MC te Heerlen [NVVC] (voorzitter)

- Dr. T. (Tom) Vromen, cardioloog, werkzaam in het Máxima Medisch Centrum te Eindhoven [NVVC]

- Dr. M. (Madoka) Sunamura, cardioloog, werkzaam in het Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland en Stichting Capri Hartrevalidatie te Rotterdam [NVVC]

- Dr. V.M. (Victor) Niemeijer, sportarts, werkzaam in het Elkerliek ziekenhuis te Helmond [VSG]

- Dr. J.A. (Aernout) Snoek, sportarts, werkzaam in het Isalaziekenhuis te Zwolle [VSG]

- D.A.A.J.H. (Dafrann) Fonteijn, revalidatiearts, werkzaam in het Reade centrum voor revalidatie en reumatologie te Amsterdam [VRA]

- Dr. H.J. (Erik) Hulzebos, klinisch inspanningsfysioloog-fysiotherapeut, werkzaam in het Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht te Utrecht [KNGF]

- E.A. (Eline) de Jong, Gezondheidszorgpsycholoog, werkzaam in het VieCuri Medisch Centrum te Venlo en Venray [LVMP] (vanaf mei 2023)

- Dr. N. (Nina) Kupper, associate professor, werkzaam in de Tilburg Universiteit te Tilburg [LVMP] (vanaf juli 2022)

- S.C.J. (Simone) Traa, klinisch psycholoog, werkzaam in het VieCuri Medisch Centrum te Venlo [LVMP] (tot mei 2023)

- Dr. V.R. (Veronica) Janssen, GZ-psycholoog in opleiding tot klinisch psycholoog, werkzaam in het Leids Universitair medisch centrum te Leiden [LVMP] (tot maart 2022)

- I.G.J. (Ilse) Verstraaten MSc., beleidsadviseur, werkzaam bij Harteraad te Den Haag [Harteraad] (vanaf december 2021)

- H. (Henk) Olk, ervaringsdeskundige [Harteraad] (vanaf juni 2022)

- A. (Anja) de Bruin, beleidsadviseur, werkzaam bij Harteraad te Den Haag [Harteraad] (tot november 2021)

- Y. (Yolanda) van der Waart, ervaringsdeskundige [Harteraad] (tot maart 2022)

- K. (Karin) Verhoeven-Dobbelsteen, gedifferentieerde hart en vaat verpleegkundige werkzaam als hartrevalidatie verpleegkundige, werkzaam in het Bernhoven Ziekenhuis te Uden [NVHVV] (vanaf juni 2022)

- R. (Regie) Loeffen, gedifferentieerde hart en vaat verpleegkundige werkzaam als hartrevalidatie verpleegkundige, werkzaam in het Canisius Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis te Nijmegen [NVHVV] (vanaf juni 2022)

- M.J. (Mike) Kuyper, MSc, verpleegkundig specialist, werkzaam in de Ziekenhuisgroep Twente te Almelo [NVHVV] (tot juni 2022)

- K.J.M. (Karin) Szabo-te Fruchte, gedifferentieerde hart en vaat verpleegkundige werkzaam als hartrevalidatie verpleegkundige, werkzaam in het Medisch Spectrum Twente te Enschede [NVHVV] (tot juni 2022)

Meelezers:

- Drs. I.E. (Inge) van Zee, revalidatiearts, werkzaam in Revant te Goes [VRA]

- T. (Tim) Boll, GZ-psycholoog, werkzaam in het St Antonius Ziekenhuis te Nieuwegein [LVMP]

- K. (Karin) Keppel-den Hoedt, medisch maatschappelijk werker, werkzaam in de Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep te Den Helder [BPSW] (vanaf mei 2023)

- C. (Corrina) van Wijk, medisch maatschappelijk werker, werkzaam in het rode Kruis Ziekenhuis te Beverwijk [BPSW] (tot mei 2023)

- D. Daniëlle Conijn, beleidsmedewerker en richtlijnadviseur Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap Fysiotherapie [KNGF]

Meelezers bij de module Werkhervatting, vanuit de richtlijnwerkgroep Generieke module Arbeidsparticipatie:

- Jeannette van Zee (senior adviseur patiëntbelang, PFNL)

- Michiel Reneman (hoogleraar arbeidsrevalidatie UMCG)

- Theo Senden (klinisch arbeidsgeneeskundige)

- Asahi Oehlers (bedrijfsarts, namens NVAB)

- Frederieke Schaafsma (bedrijfsarts en hoogleraar AmsterdamUMC)

- Anil Tuladhar (neuroloog)

- Ingrid Fakkert (arts in opleiding tot verzekeringsarts)

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. B.H. (Bernardine) Stegeman, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. J.M.H. (Harm-Jan) van der Hart, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Mogelijke restrictie |

|

Van 't Hof (voorzitter) |

Hoogleraar Interventie Cardiologie Universiteit Maastricht |

|

|

Geen |

|

Fonteijn |

Revalidatiearts |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Hulzebos |

Klinisch Inspanningsfysioloog - (sport)Fysiotherapeut |

|

Geen |

Geen |

|

Jong |

GZ-psycholoog, betaald, (poli-)klinische behandelcontacten binnen het ziekenhuis. |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Kupper |

Associate professor bij Tilburg University (betaald) |

Associate editor bij Psychosomatic Medicine (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Loeffen |

Hartrevalidatieverpleegkundige |

werkgroep hartrevalidatie NVHVV |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Niemeijer |

Sportarts Elkerliek Ziekenhuis Helmond |

Dopingcontrole official Dopingautoriteit 4u/mnd betaald (tot eind 2023) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Olker |

Patiëntenvertegenwoordiger |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Snoek |

Sportarts |

|

Geen |

Geen |

|

Sunamura |

Cardioloog |

Cardioloog, verbonden aan Stichting Capri Hartrevalidatie |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Verhoeven |

Hartrevalidatieverpleegkundige |

NVHVV voorzitter werkgroep Hartrevalidatie |

Geen |

Geen |

|