Follow-up na cholesteatoomchirurgie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de beste follow-up strategie ten behoeve van detectie van residu cholesteatoom bij patiënten die cholesteatoomchirurgie hebben ondergaan?

Deelvragen

- Kan de MRI inclusief non-epi DWI gebruikt worden in de follow-up na cholesteatoomchirurgie?

- Wanneer kan de follow-up bestaan uit MRI inclusief non-epi DWI en wanneer uit een second look?

- Wat is een goede timing van de follow-up MRI inclusief non-epi DWI en hoe vaak moet dit herhaald worden?

Aanbeveling

Aanbeveling 1

Overweeg een second look (met eventueel ketenreconstructie) uit te voeren als eerste follow-up moment na cholesteatoomchirurgie indien:

- er een klinische verdenking is op cholesteatoom; en/of

- een operatieve gehoorverbetering mogelijk of gewenst is; en/of

- dit de voorkeur heeft van de patiënt.

Zie ook de Beslisboom (zie bijlagen).

Overweeg om een MRI inclusief non-epi DWI uit te voeren als eerste follow-up moment circa 12 maanden na cholesteatoomchirurgie indien:

- er geen klinische verdenking is op cholesteatoom; en

- een operatieve gehoorverbetering niet mogelijk of niet gewenst is; en/of

- dit de voorkeur heeft van de patiënt.

Zie ook de Beslisboom (zie bijlagen).

Kies voor een MRI inclusief non-epi DWI op circa 12 maanden na cholesteatoomchirurgie als eerste keuzemodaliteit voor de follow-up indien er cholesteatoomchirurgie middels mastoidobliteratie of subtotale petrosectomie is verricht en er geen klinische verdenking is op residu cholesteatoom.

Zie ook de Beslisboom (zie bijlagen).

Aanbeveling 2

Overweeg onderstaand schema te gebruiken voor de timing en duur van de follow-up indien MRI inclusief non-epi DWI wordt gekozen als follow-up strategie.

Overweeg MRI inclusief non-epi DWI te gebruiken als follow-up strategie na:

- circa 1 jaar na operatie;

- circa 3 jaar na operatie;

- circa 5 jaar na operatie.

Overweeg bij kinderen onder de 16 jaar om ook circa 2 jaar na de operatie een MRI scan uit te voeren vanwege de mogelijk snellere en agressievere groei van het cholesteatoom.

NB: de ideale timing van de follow-up staat momenteel nog ter discussie. Dit schema is daarom niet bindend, maar kan als handvat worden aangehouden.

Aanbeveling 3

De volgende aanbevelingen zijn van toepassing na het uitvoeren van MRI inclusief non-epi DWI:

Indien een MRI een positieve uitslag heeft voor cholesteatoom

- Voer een hersanering uit.

- Zet de follow-up voort door middel van het herhalen van MRI inclusief non-epi DWI om progressie te kunnen monitoren indien (in eerste instantie) van chirurgie wordt afgezien vanwege patiëntgebonden factoren.

Indien een MRI een negatieve uitslag heeft voor cholesteatoom

- Continueer de follow-up volgens eerder genoemd schema (zie aanbeveling 2).

Indien een MRI een dubieuze uitslag heeft voor cholesteatoom

- Overweeg om de MRI inclusief non-epi DWI te herhalen afhankelijk van de lokalisatie en omvang van de radiologische laesie, de bevindingen van voorgaande OK, de kliniek en voorkeur van de patiënt.

- Verricht een second look indien de MRI niet wordt herhaald.

Zie ook de Beslisboom (zie bijlagen).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Follow-up door middel van MRI inclusief non-epi DWI kan een residu cholesteatoom opsporen en daarmee mogelijk een deel van de second look operaties vervangen. Het is dan wel van belang accurate informatie te hebben over de betrouwbaarheid van de MRI inclusief non-epi DWI ten opzichte van een second look bij het opsporen van residu cholesteatoom. Er is een literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de betrouwbaarheid van MRI inclusief non-epi DWI ten opzichte van een second look voor de detectie van residu cholesteatoom in patiënten die eerder een operatie voor cholesteatoom hebben ondergaan.

Diagnostische accuratesse

Op basis van de geselecteerde literatuur blijkt dat de diagnostische accuratesse per studie verschilt. De spreiding wat betreft de sensitiviteit (40 tot 100%) en specificiteit (50 tot 100%) is groot. Een ruime meerderheid (15 van de 17 studies) laat een sensitiviteit en specificiteit van boven de 80% zien. Dit komt overeen met de resultaten van een recente meta-analyse waarin een gepoolde sensitiviteit en specificiteit van >90% werd gerapporteerd (Lingam, 2017). Echter, deze studies zijn onderhevig aan een serieuze selectiebias. De prevalentie van residu cholesteatoom in de geïncludeerde studies varieerde tussen de 42% en 100%. Normaliter worden in de literatuur residu percentages genoemd van 9 tot 70% na een gesloten techniek (CWU) en tussen de 4 en 17% na toepassing van een open techniek (CWD) (Tomlin, 2018). De grote verschillen tussen de percentages uit de meta-analyse van Tomlin (2018) en de geïncludeerde studies in deze literatuursamenvatting zijn voornamelijk te verklaren doordat deze studies patiënten hebben geïncludeerd waarbij er reeds een klinische verdenking was op een residu cholesteatoom, maar ook door de verschillen in follow-up duur. De hoge a priori kans op residu cholesteatoom in de geïncludeerde studies beïnvloedt waarschijnlijk de uitkomsten, meest waarschijnlijk in de richting van een hoge diagnostische accuratesse. Op dit moment ontbreekt een grote studie waarbij álle patiënten (met en zonder klinische verdenking) routinematig zowel een MRI inclusief non-epi DWI als second look hebben ondergaan. Er ligt hier een kennislacune.

Timing en duur van follow-up

Follow-up na cholesteatoomchirurgie middels MRI inclusief non-epi DWI kan aanleiding geven tot vals-positieve bevindingen op de gemaakte scans. In de literatuur worden hiervoor verschillende oorzaken genoemd, waaronder cerumen, mucoïde impactie, kraakbenige reconstructie of cholesterol granuloom. Daarnaast zou bijvoorbeeld ook een abces aanleiding kunnen geven tot een vals-positieve bevinding. Om de kans op een vals-positieve bevinding zoveel mogelijk te verkleinen zouden ook de ADC, T1 en T2 sequenties meegenomen moeten worden bij de uiteindelijke beoordeling van de scans.

De MRI inclusief non-epi DWI kan ook aanleiding geven tot vals-negatieve bevindingen. Dit betreft dan doorgaans residu cholesteatomen met een kleine diameter (vaak < 3mm), of retractiepockets zonder keratine inhoud. Belangrijk is te vermelden dat een vals-negatieve bevinding op de MRI op zich niet erg hoeft te zijn mits de follow-up middels MRI inclusief non-epi DWI wordt gecontinueerd en het cholesteatoom later alsnog gedetecteerd wordt zonder veel schade aan te richten. Een belangrijke vraag blijft wat het optimale schema met betrekking tot de timing en de frequentie van de MRI inclusief non-epi DWI na cholesteatoomchirurgie is en hoe lang deze follow-up gecontinueerd dient te worden. Enerzijds is het belangrijk dat er geen overbodige MRI’s inclusief non-epi DWI worden verricht en anderzijds dat er geen residu cholesteatoom wordt gemist of er door forse groei complicaties ontstaan. Dit is natuurlijk ook afhankelijk van de groeisnelheid van het residu cholesteatoom. Er is op dit moment nog geen consensus over de timing en frequentie van de scans en verschillende klinieken in Nederland hanteren hiervoor verschillende schema’s. Ook hier ligt dus een kennislacune.

Er zijn enkele studies met betrekking tot duur van follow-up beschikbaar, maar deze betreffen relatief kleine patiëntgroepen (Horn, 2019; Pai, 2019; Steens, 2016). De studie van Pai (2019) rapporteerde een gemiddelde duur van 3,8 jaar tussen een initieel negatieve MRI inclusief non-epi DWI na de oorspronkelijke chirurgie gevolgd door een positieve scan. Deze tijdsduur varieerde in deze studie tussen de 1,6 en 7,9 jaar. Sommige patiënten hadden zelfs meerdere negatieve scans alvorens toch een residu kon worden aangetoond. De meeste residu cholesteatomen werden aangetoond tussen de 2 en 4 jaar na de oorspronkelijke operatie. De gemiddelde groeisnelheid van het residu betrof 4 mm/jaar, en varieerde tussen 0 en 18 mm/jaar. Op basis van deze studie adviseren de auteurs van dit artikel een eerste postoperatieve scan na 9 tot 12 maanden. Op basis van de gemeten groeisnelheid adviseren ze daarnaast om de MRI inclusief non-epi DWI dan elke 2 tot 3 jaar te herhalen met een duur van minimaal 5 jaar, aangezien er ook nog enkele late residuen werden gevonden na eerdere negatieve bevindingen bij MRI inclusief non-epi DWI. Ook in de studie van Steens, (2016) zijn er enkele patiënten die twee negatieve MRI-scans hadden maar waar bij toeval (bijvoorbeeld bij MRI inclusief non-epi DWI van het andere oor) op een derde scan toch een residu werd aangetoond. De studie van Horn (2019) laat zien dat er bij een eerste MRI inclusief non-epi DWI 9 maanden na de oorspronkelijke operatie sprake is van een vrij lage negatief voorspellende waarde (53%) voor de detectie van residu cholesteatoom omdat de diameter van het eventuele residu dan vaak nog minder dan 3 mm bedraagt en dan op de MRI inclusief non-epi DWI nog niet zichtbaar is. Een eerste MRI inclusief non-epi DWI 9 maanden na de operatie lijkt dus te vroeg.

Bij kinderen is de kans op een residu groter dan bij volwassenen en een residu gedraagt zich ook agressiever vanwege een hogere groeisnelheid (Plouin-Goudon, 2010; Steens, 2016). Het valt dan ook te overwegen om bij kinderen niet eerder te starten, maar om juist het interval tussen de MRI-scans te verkorten.

Het is in dit verband goed om het verschil tussen residu en recidief cholesteatoom nogmaals te benoemen. Een residu (aanwezigheid van cholesteatoom matrix in middenoor, mastoid of os temporale na een eerdere cholesteatoom verwijdering zonder connectie met het epidermaal epitheel van het trommelvlies) heeft niet per definitie een relatie met het trommelvlies en kan soms alleen met MRI inclusief non-epi DWI of second look gediagnosticeerd worden. Voor detectie van een residu is een controle middels second look of adequate MRI inclusief non-epi DWI strategie onontbeerlijk. Van een residu wordt aangenomen dat dit binnen een bepaalde tijd na de operatie detecteerbaar moet zijn geworden op MRI inclusief non-epi DWI. De follow-up periode moet lang genoeg zijn om betrouwbaar tot detectie te kunnen komen. Er is nog geen wetenschappelijke overeenstemming over de maximale duur waarbinnen een residu tot detecteerbare omvang uitgroeit. Een grote studie waarbij patiënten langer dan de nu vaak gebruikelijke 5 jaar na de oorspronkelijke operatie middels MRI inclusief non-epi DWI worden vervolgd ontbreekt helaas nog. Ook dit is een duidelijke kennislacune. Een recidief (het opnieuw ontstaan van een onoverzichtelijke retractiepocket van de pars flaccida, pars tensa, of beide met accumulatie van keratine debris na een cholesteatoom verwijdering) kan in feite gedurende het hele leven en dus ook ná 5 jaar follow-up nog ontstaan, maar zou door de relatie met het trommelvlies in de regel ook otoscopisch te diagnosticeren moeten zijn. Een langdurige follow-up middels MRI inclusief non-epi DWI wordt daarom niet aangeraden voor de detectie van een recidief cholesteatoom.

Vanwege bovengenoemde residu percentages is het noodzakelijk patiënten na een cholesteatoom operatie te vervolgen om een eventueel residu cholesteatoom tijdig te identificeren voordat dit tot schade kan leiden. Op basis van de literatuur (Horn, 2019; Pai, 2019; Steens, 2016) en op basis van expert opinion heeft de werkgroep een schema voorgesteld (tabel 2) als leidraad voor de timing en duur van de follow-up indien de follow-up plaatsvindt middels MRI inclusief non-epi DWI. Op indicatie kan de follow-up verlengd of geïntensiveerd worden, bijvoorbeeld wanneer er sprake is van een zeer infiltratieve groei of bij een klinische verdenking op residu. Dit schema is geen bindend advies, maar kan als handvat worden aangehouden. Vanwege de snellere en agressievere groei valt het te overwegen om bij kinderen onder de 16 jaar ook op 2 jaar na de operatie een MRI uit te voeren.

Tabel 2. Voorgesteld schema voor de timing en duur van follow-up middels MRI inclusief non-epi DWI voor het detecteren van een residu cholesteatoom*.

|

Circa 1 jaar na operatie |

|

Circa 3 jaar na operatie |

|

Circa 5 jaar na operatie |

*Voor kinderen onder de 16 kan worden overwogen om ook 2 jaar na de operatie een MRI inclusief DWI uit te voeren vanwege de mogelijk snellere en agressievere groei.

Indien er wordt gekozen voor follow-up middels second look, dan wordt standaard 1 jaar na operatie aangehouden voor de timing van een second look om een residu cholesteatoom op te sporen. In de paragraaf hieronder wordt de keuze van de follow-up strategie besproken.

Keuze van de follow-up strategie

De arts dient de patiënt in te lichten over alle voor- en nadelen van zowel een follow-up middels second look als follow-up middels MRI inclusief non-epi DWI. In eerste instantie bepaalt het type ingreep van de laatst uitgevoerde cholesteatoom operatie welke follow-up strategie het beste gekozen kan worden (zie hiervoor ook de Beslisboom behorend bij deze module). Daarnaast speelt de voorkeur van de patiënt natuurlijk ook een belangrijke rol. Het is belangrijk dat de patiënt in samenspraak met de arts een weloverwogen keuze maakt (shared decision making). Hieronder wordt de follow-up strategie per type laatst uitgevoerde cholesteatoom ingreep besproken:

Follow-up na CWU zonder mastoidobliteratie

Na een CWU procedure is het mogelijk middels otoscopie een recidief cholesteatoom vast te stellen. In geval van aanwezigheid van een recidief cholesteatoom of sterke klinische verdenking daarop is een hersanerende ooroperatie geïndiceerd. Het is na een CWU procedure bijna nooit mogelijk het middenoor, mastoid en epitympanum middels otoscopie te controleren op aanwezigheid van residu cholesteatoom. Dit is wel mogelijk middels een second look of door middel van een MRI inclusief DWI. De keuze tussen een van deze modaliteiten wordt onder andere bepaald door het gehoor na de voorafgaande sanerende ooringreep. Als operatieve gehoorverbetering mogelijk is en de patiënt dit ook wenst, kan de ketenreconstructie gecombineerd worden met een inspectie van mastoid en middenoor om de aanwezigheid van residu cholesteatoom uit te sluiten. Met deze second look kan dan niet alleen worden vastgesteld of er sprake is van een residu, maar kan het residu ook gelijk worden verwijderd. In dat geval is een MRI inclusief non-epi DWI van weinig toegevoegde waarde. Een argument om in hierbij toch een MRI inclusief non-epi DWI voorafgaand aan de heroperatie te doen is om beter geïnformeerd te zijn over de aanwezigheid van residu cholesteatoom zodat de patiënt beter voorgelicht kan worden en hiermee rekening gehouden kan worden met de planning van de operatietijd. Als gehoorverbetering niet mogelijk is, of als dit wel mogelijk is maar patiënt geen operatie wenst, is een MRI inclusief non-epi DWI aangewezen om residu cholesteatoom aan te tonen of uit te sluiten. Het voordeel van een MRI inclusief non-epi DWI is dat een patiënt geen operatie behoeft te ondergaan indien er geen radiologische verdenking op cholesteatoom bestaat.

Follow-up na CWD/CRH zonder mastoidobliteratie

De follow up na CWD/CRH bestaat in principe uit periodieke otoscopie en oortoilet. Bij deze ingreep kan het operatiegebied goed otoscopisch gecontroleerd worden op aanwezigheid van residu cholesteatoom in het middenoor of de radicaalholte. Bij twijfel hierover, kan een MRI inclusief non-epi DWI ingezet worden om meer zekerheid te verkrijgen voordat overgegaan wordt tot een hersanering. Bij (klinische verdenking op) aanwezigheid van een recidief of residu cholesteatoom is in principe een hersanering geïndiceerd. Als operatieve gehoorverbetering mogelijk is en de patiënt dit ook wenst, kan een ketenreconstructie uitgevoerd worden. Gelijktijdig kan dan ook een inspectie van middenoor en indien nodig ook de mastoidholte uitgevoerd worden om aanwezigheid van residu cholesteatoom uit te sluiten. Er kunnen verschillende overwegingen zijn om in overleg met de patiënt bij (verdenking op) aanwezigheid van een recidief of residu cholesteatoom af te wachten en otoscopische follow-up te continueren, waaronder bepaalde patiënt gebonden factoren (zie paragraaf ‘De uitslag van een MRI’).

Follow-up na CWU of CWD/CRH met mastoidobliteratie

In tegenstelling tot de situatie na CWU zonder mastoidobliteratie waarbij een eventuele ketenreconstructie aangegrepen kan worden om niet alleen het middenoor, maar ook het mastoid te controleren op aanwezigheid van residu cholesteatoom, is controle van het mastoid na CWU of CWD/CRH met mastoidobliteratie niet mogelijk zonder het obliteratiemateriaal uit te nemen. Dit is niet in lijn met de doelstelling van deze techniek zodat controle op aanwezigheid van residu cholesteatoom na elke sanerende ooroperatie met mastoidobliteratie middels MRI inclusief non-epi DWI uitgevoerd dient te worden ook wanneer er een ketenreconstructie uitgevoerd gaat worden.

Follow-up na subtotale petrosectomie (STP)

Na een STP is de externe gehoorgang afgesloten en dus is otoscopische controle niet meer mogelijk. Controle op aanwezigheid van residu cholesteatoom na een STP dient met een MRI onderzoek gedaan te worden.

De uitslag van een MRI

De uitslag van de MRI kan opgedeeld worden in de volgende categorieën:

- Positief voor aanwezigheid van cholesteatoom: bij een positieve uitslag van de MRI is doorgaans een hersanering geïndiceerd. Er kunnen echter verschillende overwegingen zijn om in overleg met de patiënt hiervan af te wijken en ervoor te kiezen de MRI op een later tijdstip te herhalen. Voorbeelden hiervan zijn onder andere patiënt gebonden factoren zoals voorkeur van de patiënt, (hoge) leeftijd, co-morbiditeit eventueel in combinatie met cholesteatoom gerelateerde factoren zoals lokalisatie en omvang van de radiologische laesie, de bevindingen bij de voorgaande ingreep en klinische verschijnselen.

- Dubieus, waarbij aanwezigheid van cholesteatoom niet met zekerheid kan worden aangetoond of uitgesloten: bij een dubieuze uitslag van de MRI kan ervoor worden gekozen de MRI te herhalen of een hersanerende ooroperatie uit te voeren. Factoren die de keuze mede bepalen zijn de hierboven genoemde patiënt gebonden factoren.

- Negatief voor aanwezigheid van cholesteatoom: bij een negatieve uitslag van de MRI wordt poliklinische follow-up met otoscopie gecontinueerd en wordt de MRI herhaald omdat een residu cholesteatoom kleiner dan de detectiegrens van de gebruikte scanner mogelijk gemist kan zijn bij het eerste controle moment.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

De afweging voor follow-up middels second look of MRI inclusief non-epi DWI wordt altijd in goed overleg met de patiënt gemaakt. Het belangrijkste doel van MRI inclusief non-epi DWI is een adequate controle van het oor met betrekking tot het diagnosticeren van residu cholesteatoom. Een groot voordeel van MRI is dat een patiënt niet geopereerd hoeft te worden. Hierdoor hoeft een patiënt geen narcose te ondergaan, wordt de patiënt niet blootgesteld aan (kleine) operatierisico’s en heeft de patiënt geen ongemak van herstel of verzuim van werk of school. Een nadeel van MRI inclusief DWI is dat een klein residu cholesteatoom mogelijk gemist kan worden en eventueel conductief gehoorverlies niet met MRI kan worden verholpen. Een voordeel van een second look operatie is dat in geval van afwezigheid van residu cholesteatoom er minder twijfel is over de betrouwbaarheid van deze bevinding vergeleken met MRI inclusief non-EPI DWI vanwege de kans op een vals negatieve uitslag. Hierdoor hoeft een second look waarbij geen residu cholesteatoom wordt aangetroffen niet herhaald te worden. Dit betekent echter niet dat geen follow-up meer nodig is, aangezien otoscopische follow-up ter uitsluiting van recidief cholesteatoom geïndiceerd blijft.

Er dient onderscheid gemaakt te worden tussen patiënten met en zonder persisterend (conductief) gehoorverlies na een voorgaande operatie. Mogelijk hebben patiënten met een persisterend conductief gehoorverlies de wens om dit operatief te verbeteren. Indien er geen obliteratie heeft plaatsgevonden, kan het mastoid ook eenvoudig worden gecontroleerd tijdens deze operatie en is een MRI mogelijk van weinig toegevoegde waarde (behalve misschien voor het plannen van de operatieduur).

Ook bij patiënten met een klinisch evident recidief of residu cholesteatoom heeft een second look de voorkeur en heeft een extra MRI waarschijnlijk weinig meerwaarde (behalve misschien voor het evalueren van de omvang van het recidief/ residu en het plannen van de operatieduur).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Over de impact op de kosten is op dit moment nog weinig bekend. Belangrijk is om het gehele traject in ogenschouw te nemen. Bij een second look operatie is er voor de controle in principe één operatie nodig om vast te stellen of er sprake is van een residu cholesteatoom, tenzij er tijdens de ingreep een residu wordt aangetroffen. Bij een MRI strategie zullen er naar alle waarschijnlijkheid meerdere scans worden gemaakt om een residu cholesteatoom vast te stellen dan wel uit te sluiten. Indien cholesteatoom wordt aangetroffen is alsnog een operatie nodig. Of de MRI strategie voordeliger is hangt af van de lokale kosten van een MRI inclusief non-epi DWI, de lokale kosten van een second look, het aantal MRI’s dat gemaakt moet worden en het residupercentage, ofwel het aantal maal dat er na MRI inclusief non-epi DWI alsnog een operatie moet volgen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er worden geen grote barrières verwacht wat betreft de aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie van MRI inclusief non-epi DWI in het follow-up traject na cholesteatoomchirurgie omdat dit al deel uitmaakt van de huidige praktijk in de meeste ziekenhuizen. Voor deze richtlijn wordt de aanname gemaakt dat de kwaliteit van MRI inclusief non-epi DWI in elk ziekenhuis voldoende is. Wellicht is scholing van radiologen (en/of KNO-artsen) nodig om in alle ziekenhuizen accuratesse van MRI inclusief non-epi DWI techniek te optimaliseren. Daarnaast heeft wellicht niet elk centrum voldoende MRI capaciteit om dit voor follow-up na cholesteatoomchirurgie in te voeren. Indien in een centrum de juiste MRI techniek en/of radiologische expertise niet beschikbaar is, maar er wel een indicatie voor is, dient overwogen te worden om een patiënt te verwijzen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Aanbeveling-1

De keuze voor de follow-up strategie wordt in goed overleg met de patiënt gemaakt. De arts dient hierbij de patiënt te informeren over de voor- en nadelen van zowel de second look als de MRI inclusief non-epi DWI-strategie. Het type ingreep van de laatst uitgevoerde cholesteatoomoperatie bepaalt in eerste instantie welke follow-up strategie het beste gekozen kan worden. Daarnaast zullen ook aanvullende potentiële overwegingen zoals de bevindingen bij de laatst uitgevoerde operatie, lokalisatie van de laesie op de MRI, de omvang van de laesie, voorkeur van de patiënt en patiëntgebonden factoren zoals leeftijd, comorbiditeit en eventuele contra-indicaties voor MRI een rol spelen in de uiteindelijke keuze van modaliteit voor follow-up na cholesteatoomchirurgie. Omdat de bewijskracht vanuit de literatuur niet eenduidig is, is gekozen voor een zwakke aanbeveling.

Aanbeveling-2

In de studie van Pai (2019) werden de meeste residu cholesteatomen aangetoond tussen de 2 en 4 jaar na de oorspronkelijke operatie. De gemiddelde groeisnelheid van het residu betrof 4 mm per jaar en varieerde tussen de 0 en 18 mm per jaar. Op basis van deze studie wordt geadviseerd om een eerste postoperatieve scan circa 12 maanden na de operatie uit te voeren. Op basis van de gemeten groeisnelheid wordt geadviseerd dit dan elke 2 tot 3 jaar te herhalen met een minimale duur van 5 jaar. Uit de studie van Horn (2019) blijkt voorts dat een MRI inclusief non-epi DWI 9 maanden na de cholesteatoomoperatie een lage negatief voorspellende waarde heeft. Mede op basis van deze gegevens komt de werkgroep tot het voorstel om de eerste MRI inclusief non-epi DWI na de laatst uitgevoerde operatie na circa 12 maanden te verrichten. Omdat al deze gegevens afkomstig zijn uit kleine studies wordt deze aanbeveling zwak geformuleerd. Gezien de mogelijke grotere groeisnelheid van een residu cholesteatoom bij kinderen en de grotere kans op een residu heeft de werkgroep ervoor gekozen ter overweging mee te geven om het tijdsinterval tussen de scans bij kinderen in het begin van de follow-up periode kleiner te maken dan bij volwassenen. Dit schema geeft een indicatie van wat de werkgroep als zinvol acht qua timing en duur van de follow-up indien DWI MRI wordt gekozen als follow-up strategie. Op indicatie kan de follow-up verlengd of geïntensiveerd worden bijvoorbeeld bij klinische verdenking op residu.

Aanbeveling-3

Deze aanbeveling is van toepassing indien MRI inclusief non-epi DWI is uitgevoerd. De uiteindelijke strategie na het uitvoeren van een MRI inclusief non-epi DWI hangt af van de uitslag van de MRI (positief, dubieus of negatief). De aanbeveling voor een positieve en negatieve scan is sterk geformuleerd omdat dit de enige logische vervolgstap is. Natuurlijk spelen hier nog steeds aanvullende potentiële overwegingen zoals de lokalisatie van de laesie op de MRI, de omvang van de laesie, bevindingen tijdens de voorgaande operatie, voorkeur van de patiënt en patiëntgebonden factoren zoals leeftijd, comorbiditeit en eventuele contra-indicaties voor MRI een rol in de uiteindelijke keuze van modaliteit voor follow-up na cholesteatoomchirurgie. Bij een dubieuze uitslag spelen deze aanvullende potentiële overwegingen een grotere rol, vandaar de zwakke formulering van deze aanbeveling.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Het gebruik van MRI inclusief DWI voor het opsporen van residu cholesteatoom vindt reeds veel opgang, maar de vraag of een MRI daadwerkelijk even betrouwbaar is als een second look voor het opsporen van residu cholesteatoom is nog onvoldoende beantwoord. Ook is er sprake van praktijkvariatie wat betreft de plaats en timing van de MRI in de follow-up na een cholesteatoomoperatie en hoe lang follow up middels MRI zou moeten worden voortgezet.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Diagnostic accuracy

|

Low GRADE |

Non-echo planar diffusion weighted MRI may be a valid follow-up modality for patients who underwent cholesteatoma surgery.

Sources: (Allam, 2019, Bakaj, 2016; De Foer, 2008; Foti, 2019; Garrido, 2014; Horn, 2019; Huins, 2010; Ilica, 2012; Khemani, 2012; Lecler, 2015; Lingam, 2013; Lips, 2019; Nash, 2015; Osman, 2017; Patel, 2018; Pizzini, 2010; Profant, 2012) |

False positive findings

|

Low GRADE |

Non-echo planar diffusion weighted MRI may yield false positive findings during follow-up of patients who underwent cholesteatoma surgery. The differential diagnosis for false positive findings seems broad.

Sources: (Allam, 2019, De Foer, 2008; Garrido, 2014; Huins, 2010; Ilica, 2012; Khemani, 2012; Lecler, 2015, Pizzini, 2010; Profant, 2012) |

False negative findings

|

Low GRADE |

Non-echo planar diffusion weighted MRI may yield false negative findings during follow-up of patients who underwent cholesteatoma surgery. The majority of false negative findings may be related to a small cholesteatoma size (< 3 mm).

Sources: (Allam, 2019, Bakaj, 2016; De Foer, 2008; Foti, 2019; Horn, 2019; Huins, 2010; Khemani, 2012; Lecler, 2015; Lingam, 2013; Lips, 2019; Nash, 2015; Patel, 2018) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Observational studies

The prospective observational study performed by Horn (2019) evaluated the reliability of MRI including non-epi DWI to rule out residual cholesteatoma in patients scheduled for second look surgical exploration. All patients who were scheduled for a second look surgery and who were at least six months after cholesteatoma surgery were included. Patients were excluded when they had contraindications for MRI. In total, 33 patients underwent both MRI and second look surgery and were previously treated by canal wall up (CWU) primary cholesteatoma repair. As a reference, the observations during canal wall up (CWU) surgery were used.

The prospective observational study performed by Allam (2019) assessed the reliability of MRI including non-epi DWI to detect recurrent cholesteatoma in patients who underwent canal wall up mastoidectomy. Patients with suspected cholesteatoma recurrence after canal wall up mastoidectomy were included. Exclusion criteria were motion artefacts during the MRI. In total, 56 patients underwent both MRI and second look surgery. Final diagnoses were based on revision or second look surgery.

The prospective observational study performed by Foti (2019) compared the diagnostic accuracy of MRI including non-epi DWI to identify residual and recurrent cholesteatoma using the second look surgery as the reference standard. Patients who previously underwent cholesteatoma surgery (CWU and CWD technique) and who received MRI were included in the study. Patients were excluded if they had a non-MRI-compatible pacemaker, incomplete MRI protocol, claustrophobia, or when there was no surgical correlation. In total, 19 patients underwent both MRI and second look surgery. Five patients were treated on both ears, resulting in 24 ears that were included in the analysis. Final diagnosis was based on revision or second look surgery.

The retrospective observational study performed by Lips (2019) compared the performance of 1.5 T versus 3 T MRI including non-epi DWI with or without additional T1 and T2 sequences in the detection of residual and/or recurrent cholesteatoma. Patients previously underwent CWU or CWD primary cholesteatoma surgery. Patients with postoperative routine survey MRI who subsequently underwent second look surgery were included. Patients were excluded due to the following reasons: inaccurate or incomplete MRI protocol, abundant artefacts because of dental braces, and alternative diagnosis (2 metastasis, 1 neurofibroma, 1 encephalocele, 1 neuroendocrine tumor and 1 Langerhans cell histiocytosis). In total, 135 patients underwent both MRI and second look surgery. Because of renewed suspicion of recurrent disease, 28 patients underwent multiple MRI scans which were all followed by second look surgery. Definite surgical diagnosis was used as gold standard.

The prospective observational study performed by Patel (2018) evaluated the performance of MRI including non-epi DWI in the detection of residual or recurrent disease in patients who have had a previous canal wall down (CWD) mastoidectomy. Patients with a CWD mastoidectomy subsequently having at least one further MRI or surgery for suspected or confirmed cholesteatoma were included. Exclusion criteria were not described. In total, 13 patients underwent both MRI and second look surgery. As some patients underwent multiple mastoid explorations, a total of 20 patient episodes were included. Final diagnoses were based on second look surgery.

The prospective observational study performed by Osman (2017) evaluated the accuracy and sensitivity of MRI including non-epi DWI in the detection of recurrent cholesteatoma in patients who have had a previous CWD or CWU mastoidectomy. Patients with clinical and CT suspicion of recurrence and were scheduled for second look operation were included. Exclusion criteria were unclear operative history, active infection or mastoid abscess. In total, 30 patients underwent both MRI and second look surgery.

The prospective observational study performed by Bakaj (2016) investigated the correlation between preoperative MRI including non-epi DWI with surgical findings of recidivous middle ear cholesteatoma after canal wall up and canal wall down mastoidectomy. The study included all patients requiring second look surgery based on clinical suspicion of recurrence. Exclusion criteria were not described. In total, 24 patients were included that underwent both MRI and second look or revision surgery. As some patients underwent multiple surgical procedures, a total of 27 ears was included, of which 12 were second look surgery cases after CWU and 15 were revision surgeries after CWD.

The prospective observational study performed by Lecler (2015) compared the residual cholesteatoma detection accuracy of MRI including non-epi DWI at one year postoperative with second look surgery in pediatric patients who have undergone primary middle ear surgery for cholesteatoma. The study did not describe which primary surgical technique was used. All children with cholesteatoma requiring second look surgery based on clinical suspicion of recurrence were included. Exclusion criteria were not described. In total, 24 children underwent both MRI and second look surgery. Histological evaluation was systematically performed.

The retrospective observational study performed by Nash (2015) evaluated the performance of MRI including non-epi DWI in post-operative cholesteatoma. The study did not describe which primary surgical technique was used. Patients were included when they previously underwent cholesteatoma surgery. Patients were excluded when operative findings were not available. In total, 158 patients underwent both MRI and second look surgery.

The prospective observational study performed by Garrido (2014) evaluated the accuracy of MRI including non-epi DWI in the diagnosis of recurrent cholesteatoma in patients with clinical suspicion of cholesteatoma. The study did not describe which primary surgical technique was used. Patients were included when they had a clinical suspicion of recurrent or residual cholesteatoma during follow-up after previous surgery. Exclusion criteria were not described. In total, 27 patients with a clinical suspicion of recurrent or residual cholesteatoma were included and underwent both MRI and second look surgery. Final diagnosis was established with surgical findings in all cases.

The retrospective observational study performed by Lingam (2013) evaluated the accuracy of MRI including non-epi DWI of postoperative middle ear cleft cholesteatoma. The study did not describe which primary surgical technique was used. Patients who previously underwent surgery for cholesteatoma and underwent MRI prior to surgery were included. The final diagnosis for presence and location of cholesteatoma was made at surgery with histologic confirmation. Patients were excluded when they had contraindications for MRI. In total, 56 patients underwent both MRI and second look surgery. As some patients underwent multiple surgical procedures with prior MRI, a total of 71 episodes were included.

The prospective observational study of Ilica (2012) assessed the detection efficiency of MRI including non-epi DWI imaging for patients with suspected recurrent cholesteatoma. Patients were included when they underwent primary cholesteatoma surgery and had clinically suspected recurrence. Exclusion criteria were not described. The diagnosis of all recurrent cholesteatomas were confirmed by histopathological examination. In total, 5 patients with clinical suspicion of recurrent cholesteatoma underwent both MRI and second look surgery.

The prospective observational study performed by Profant (2012) compared the reliability of MRI including non-epi DWI against surgery for detecting residual cholesteatoma among patients who previously underwent cholesteatoma surgery. Included patients had a clinical suspicion of residual cholesteatoma after CWD/CWU surgery. Exclusion criteria were not described. In total, 17 patients were included who underwent MRI and second look surgery.

The prospective observational study performed by Khemani (2011) assessed the accuracy of MRI including non-epi DWI in the detection of cholesteatoma in patients who previously underwent canal wall up surgery. All patients were included when they previously underwent canal wall up surgery for cholesteatoma and were offered second look surgery to assess for residual or recurrent disease as part of routine follow-up. In total, 38 patients were included who underwent MRI and second look surgery.

The prospective observational study performed by Huins (2010) evaluated the diagnostic performance of MRI including non-epi DWI in the detection of cholesteatoma among patients suspected with residual cholesteatoma. Patients with suspected residual cholesteatoma were included in the study. Patients were excluded when they had incomplete episodes (not both DWI MRI and operative data), when they were medically unfit for further surgery or MRI, or when they refused further intervention. In total, 18 patients underwent both MRI and second look surgery.

The retrospective observational study performed by Pizzini (2010) evaluated the value of MRI including non-epi DWI in the diagnosis of relapsing cholesteatoma. Patients with possible relapsing cholesteatoma after CWU or CWD tympanoplasty were included. In total 13 patients were included in the study and underwent DWI MRI. Two patients did not receive second look surgery and were excluded from the analyses. The study did not describe why these patients did not underwent second look surgery.

The prospective observational study performed by De Foer (2008) analysed the role of MRI including non-epi DWI for the detection of residual cholesteatoma after CWU mastoidectomy before eventual second look surgery. Patients who underwent first-stage cholesteatoma surgery between 10 and 18 months earlier and were clinically followed by micro-otoscopy and audiometry. Exclusion criteria were not described. In total, 19 patients underwent both MRI and second look surgery.

Results

Diagnostic accuracy (crucial)

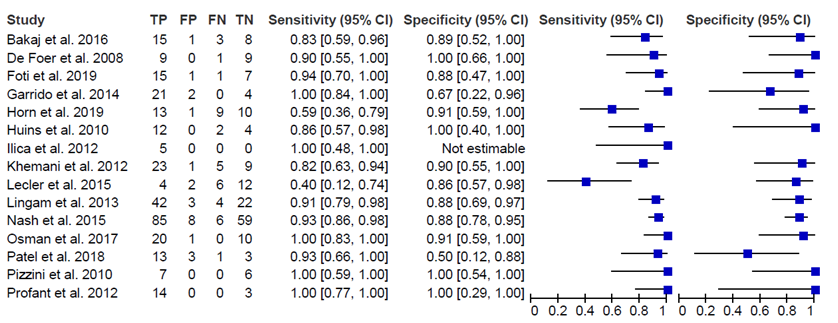

The outcomes sensitivity and specificity of MRI including non-epi DWI were reported in all 17 studies. In Table 1 the results of the 17 studies are summarized. Figure 1 shows the results of 15 of these studies. The sensitivity varied between 0.40 and 1.00. The specificity varied between 0.50 and 1.00. The positive predictive value (PPV) varied between 87% and 97%, the negative predictive value (NPV) varied between 53% and 100%.

Allam (2019) and Lips (2019) did not report the number of true positive findings, false positive findings, false negative findings, and true negative findings, but only reported the sensitivity and specificity of MRI including non-epi DWI . Allam (2019) reported a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 94%. Lips (2019) reported a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 59% when 1.5T was used in the MRI protocol, and a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 46% when 3.0T was used in the MRI protocol.

Some studies also reported results from a second reader. Lips (2019) reported the results from a second reader, a well-trained fellow neuroradiology with 5 years of experience in head and neck radiology. This second reader had a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 62% for the 1.5T MRI protocol, and sensitivity of 76% and specificity of 55% for the 3.0T MRI protocol. When also the T1 and T2 images were included in the protocol, a sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 76% was reported for the 1.5T MRI protocol, and sensitivity of 68% and specificity of 64% for the 3.0T MRI protocol. Leclerc (2016) reported data from a second reader, which resulted in a sensitivity of 30% and specificity of 86%. Both studies reported a moderate interobserver agreement of 0.7 and 0.647, respectively.

Figure 1. Forest plot of the sensitivity and specificity of the included studies

TP: true positive findings, FP: false positive findings, FN: false negative findings, TN: true negative findings, CI: confidence interval

Differential diagnosis among false positive findings (important)

In 8 studies, the authors reported the differential diagnosis for the false positive findings. Horn (2019) reported 1 false positive finding due to an increased signal because of a small piece of cartilage. Foti (2019) reported 1 false positive finding due to the presence of squamous cell carcinoma. Lips (2019) reported three false positive findings using the 3.0T MRI protocol due to extensive postoperative changes that showed restricted diffusion, such as haemorrhagic changes, fibrosis, glue, and granulation tissue. Patel (2018) reported 3 false positive findings due to a mixture of wax and keratin. Osman (2017) reported one false positive finding due to bone graft placed during the initial surgery to seal a lateral semi-circular canal fistula. Bakaj (2016) reported 1 false positive finding due to an artefact on air-bone interface. Nash (2015) reported 8 false positive findings due to cholesterol granuloma, calcified cartilage, and atypical purulent/proteinaceous fluid found in the mastoid during surgery. Lingam (2013) reported three false positive cases due to extensive cerumen in the medial external auditory canal that abutted against a retracted tympanic membrane, or due to mucosal disease.

The remaining 9 studies did not report any false positive findings (De Foer, 2008; Huins, 2010; Ilica, 2012; Pizzini, 2010; Profant, 2012) or did not report why their findings were false positive (Allam, 2019; Garrido, 2014; Khemani, 2012; Lecler, 2015).

Explanations for false negative findings (important)

In 12 studies, the authors reported the false negative findings. Horn (2019) reported 9 false negative cases, in 5 of them the residual cholesteatoma size was ≤ 3 mm. The size of the 4 remaining false negative cases ranged from 4 to 40 mm. Foti (2019) reported 1 false negative finding due to a small (size was not reported) cholesteatoma lacking clinical aggressiveness. Lips (2019) reported 11 false negative findings using the 3T MRI protocol, but only one of them was due to a small size. The other false negative findings were due to technical issues (no restricted diffusion and low or high signal on other images). Patel (2018) reported 1 false negative finding due to a small size (2 mm). Bakaj (2016) reported 3 false negative findings with a size of 2.5 mm, 2 mm and 1 mm. Lecler (2015) reported 6 false negative findings which were all less than 3 mm. Nash (2015) reported 6 false negative findings all due to small cholesteatoma sizes. Lingam (2013) reported 4 false negative cases all due to their small size (<3 mm). Khemani (2011) reported 5 false negative cases, of which 4 of them had a size < 2 mm. The remaining case related to a keratin-filled retraction pocket measuring 5 mm in size in close relation to the lateral external auditory canal. Huins (2010) reported 2 false negative findings due to small size (< 2 mm) and movement artefacts.

The remaining 6 studies did not report any false negative findings (Garrido, 2014; Ilica, 2012; Osman, 2017; Pizzini, 2010; Profant, 2012) or did not report why their findings were false negative (Allam, 2019).

Level of evidence of the literature

Diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV)

Because we included diagnostic accuracy studies, the level of evidence regarding all outcome measures started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias regarding patient selection and large interval between MRI including non-epi DWI and second look surgery) and number of included patients (imprecision). The level of evidence was therefore ‘low’.

False positive findings

Because we included diagnostic accuracy studies, the level of evidence regarding the false positive findings started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias regarding patient selection and large interval between MRI including non-epi DWI and second look surgery) and number of included patients (imprecision). The level of evidence was therefore ‘low’.

False negative findings

Because we included diagnostic accuracy studies, the level of evidence regarding the false negative findings started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias regarding patient selection and large interval MRI including non-epi DWI and second look surgery) and number of included patients (imprecision). The level of evidence was therefore ‘low’.

Table 1. Summary of the most important characteristics of the included studies

|

Study |

N |

Minimal detected size |

Prevalence |

PPV |

NPV |

|

Horn, 2019 |

33 |

2.0 mm |

67% |

93% |

53% |

|

Allam, 2019 |

56 |

2.1 mm |

68% |

97% |

90% |

|

Foti, 2019 |

24 |

5.0 mm |

67% |

94% |

88% |

|

Lips, 2019 |

164 |

4.0 mm |

1.5T = 77% 3.0T = 69% |

1.5T = 89% 3.0T = 78% |

1.5T = 81% 3.0T = 50% |

|

Patel, 2018 |

20 |

NR |

70% |

87% |

75% |

|

Osman, 2017 |

30 |

7.0 mm |

67% |

95% |

100% |

|

Bakaj, 2016 |

27 |

3.0 mm |

67% |

94% |

73% |

|

Lecler, 2015 |

24 |

3.0 mm |

42% |

1 = 67% 2 = 60% |

1 = 67% 2 = 63% |

|

Nash, 2015 |

158 |

NR |

54% |

91% |

91% |

|

Garrido, 2014 |

27 |

NR |

78% |

91% |

100% |

|

Lingam, 2013 |

71 |

3.0 mm |

65% |

93% |

85% |

|

Ilica, 2012 |

5 |

NR |

100% |

NR |

NR |

|

Profant, 2012 |

17 |

3.0 mm |

82% |

NR |

NR |

|

Khemani, 2011 |

38 |

3.0 mm |

48% |

96% |

64% |

|

Huins, 2010 |

18 |

NR |

67% |

NR |

67% |

|

Pizzini, 2010 |

13 |

2.0 mm |

55% |

NR |

NR |

|

De Foer, 2008 |

19 |

2.0 mm |

47% |

NR |

90% |

|

Total |

744 |

|

66% |

88% |

77% |

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the validity/accuracy of MRI including non-epi DWI follow-up of patients who underwent cholesteatoma surgery?

P (patients): patients who underwent cholesteatoma surgery;

I (intervention): MRI including non-epi DWI;

R (reference): second look or revision surgery;

O (outcome measure): diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV)), differential diagnosis among false positive findings, explanations for false negative findings.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered the diagnostic accuracy as critical outcome measure for decision making; and the differential diagnosis among false positive findings and the explanation for false negative findings as important outcome measures for decision making.

The guideline committee defined the outcome measures as follows:

- False positive findings on MRI: the guideline committee was interested in the differential diagnosis of false positive findings.

- False negative findings on MRI: the guideline committee was especially interested in the size of the undetected lesions.

For the remaining outcome measures, the guideline committee did not define the outcome measures a priori, but used the definitions used in the studies.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase via Embase.com were searched with relevant search terms until 23 January 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 247 hits when we limited our search to studies categorized as systematic reviews, RCT’s and observational studies. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: randomized controlled trials, comparative observational studies, or systematic reviews on the validity/accuracy of MRI including non-epi DWI compared to second look/revision surgery in patients who underwent primary cholesteatoma surgery. In total, 50 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 33 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and 17 studies were included.

Results

In total, 17 observational studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Allam HS, Abdel Razek AAK, Ashraf B, Khalek M. Reliability of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in differentiation of recurrent cholesteatoma and granulation tissue after intact canal wall mastoidectomy. J Laryngol Otol. 2019 Dec;133(12):1083-1086. doi: 10.1017/S0022215119002421. Epub 2019 Nov 18. PubMed PMID: 31735177.

- Bakaj T, Zbrozkova LB, Salzman R, Tedla M, Starek I. Recidivous cholesteatoma: DWI MR after canal wall up and canal wall down mastoidectomy. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2016;117(9):515-520. PubMed PMID: 27677195.

- De Foer B, Vercruysse JP, Bernaerts A, Deckers F, Pouillon M, Somers T, Casselman J, Offeciers E. Detection of postoperative residual cholesteatoma with non-echo-planar diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Otol Neurotol. 2008 Jun;29(4):513-7. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31816c7c3b. PubMed PMID: 18520587.

- Foti G, Beltramello A, Minerva G, Catania M, Guerriero M, Albanese S, Carbognin G. Identification of residual-recurrent cholesteatoma in operated ears: diagnostic accuracy of dual-energy CT and MRI. Radiol Med. 2019 Jun;124(6):478-486. doi: 10.1007/s11547-019-00997-y. Epub 2019 Feb 2. PubMed PMID: 30712164.

- Garrido L, Cenjor C, Montoya J, Alonso A, Granell J, Gutiérrez-Fonseca R. Diagnostic capacity of non-echo planar diffusion-weighted MRI in the detection of primary and recurrent cholesteatoma. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2015 Jul-Aug;66(4):199-204. doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2014.07.006. Epub 2015 Feb 26. English, Spanish. PubMed PMID: 25726148.

- Horn RJ, Gratama JWC, van der Zaag-Loonen HJ, Droogh-de Greve KE, van Benthem PG. Negative Predictive Value of Non-Echo-Planar Diffusion Weighted MR Imaging for the Detection of Residual Cholesteatoma Done at 9 Months After Primary Surgery Is not High Enough to Omit Second Look Surgery. Otol Neurotol. 2019 Aug;40(7):911-919. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002270. PubMed PMID: 31219966.

- Huins CT, Singh A, Lingam RK, Kalan A. Detecting cholesteatoma with non-echo planar (HASTE) diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Jul;143(1):141-6. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.02.021. PubMed PMID: 20620633.

- Ilıca AT, Hıdır Y, Bulakbaşı N, Satar B, Güvenç I, Arslan HH, Imre N. HASTE diffusion-weighted MRI for the reliable detection of cholesteatoma. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2012 Mar-Apr;18(2):153-8. doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.4246-11.3. Epub 2011 Sep 29. PubMed PMID: 21960134.

- Khemani S, Lingam RK, Kalan A, Singh A. The value of non-echo planar HASTE diffusion-weighted MR imaging in the detection, localisation and prediction of extent of postoperative cholesteatoma. Clin Otolaryngol. 2011 Aug;36(4):306-12. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2011.02332.x. PubMed PMID: 21564557.

- Lecler A, Lenoir M, Peron J, Denoyelle F, Garabedian EN, Pointe HD, Nevoux J. Magnetic resonance imaging at one year for detection of postoperative residual cholesteatoma in children: Is it too early? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015 Aug;79(8):1268-74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.05.028. Epub 2015 May 29. PubMed PMID: 26071017.

- Lingam RK, Khatri P, Hughes J, Singh A. Apparent diffusion coefficients for detection of postoperative middle ear cholesteatoma on non-echo-planar diffusion-weighted images. Radiology. 2013 Nov;269(2):504-10. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130065. Epub 2013 Jun 25. PubMed PMID: 23801772.

- Lingam, R. K., & Bassett, P. (2017). A Meta-Analysis on the Diagnostic Performance of Non-Echoplanar Diffusion-Weighted Imaging in Detecting Middle Ear Cholesteatoma: 10 Years On. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology, 38(4), 521–528. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000001353

- Lips LMJ, Nelemans PJ, Theunissen FMD, Roele E, van Tongeren J, Hof JR, Postma AA. The diagnostic accuracy of 1.5 T versus 3 T non-echo-planar diffusion-weighted imaging in the detection of residual or recurrent cholesteatoma in the middle ear and mastoid. J Neuroradiol. 2019 Apr 2. pii: S0150-9861(18)30332-8. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2019.02.013. (Epub ahead of print) PubMed PMID: 30951771.

- Nash R, Wong PY, Kalan A, Lingam RK, Singh A. Comparing diffusion weighted MRI in the detection of post-operative middle ear cholesteatoma in children and adults. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015 Dec;79(12):2281-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.10.025. Epub 2015 Oct 27. PubMed PMID: 26547234.

- Osman NM, Rahman AA, Ali MT. The accuracy and sensitivity of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging with Apparent Diffusion Coefficients in diagnosis of recurrent cholesteatoma. Eur J Radiol Open. 2017 Mar 23;4:27-39. doi: 10.1016/j.ejro.2017.03.001. eCollection 2017. PubMed PMID: 28377947; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5369335.

- Patel B, Hall A, Lingam R, Singh A. Using Non-Echoplanar Diffusion Weighted MRI in Detecting Cholesteatoma Following Canal Wall Down Mastoidectomy – Our Experience with 20 Patient Episodes. J Int Adv Otol. 2018 Aug;14(2):263-266. doi: 10.5152/iao.2018.5033. PubMed PMID: 30256200; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6354465.

- Pizzini FB, Barbieri F, Beltramello A, Alessandrini F, Fiorino F. HASTE diffusion-weighted 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of primary and relapsing cholesteatoma. Otol Neurotol. 2010 Jun;31(4):596-602. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181dbb7c2. PubMed PMID: 20393373.

- Plouin-Gaudon, I., Bossard, D., Fuchsmann, C., Ayari-Khalfallah, S., & Froehlich, P. (2010). Diffusion-weighted MR imaging for evaluation of pediatric recurrent holesteatomas. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology, 74(1), 22–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.09.035

- Profant M, Sláviková K, Kabátová Z, Slezák P, Waczulíková I. Predictive validity of MRI in detecting and following cholesteatoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012 Mar;269(3):757-65. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1706-8. Epub 2011 Jul 23. PubMed PMID: 21785975.

- Tomlin J, Chang D, McCutcheon B, Harris J. Surgical technique and recurrence in cholesteatoma: a meta-analysis. Audiol Neurootol. 2013;18(3):135‐142. doi:10.1159/000346140

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for diagnostic test accuracy studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Horn, 2019 |

Type of study[1]: Prospective observational study.

Setting and country: Secondary teaching hospital, The Netherlands.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors disclose disclose no conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: All patients who were scheduled for a second look surgery between September 2009 and May 2015, and who were at least 6 months after cholesteatoma-surgery. In our practice, all patients were scheduled for a second look operation after primary surgery, regardless of the presence or absence of clinical suspicion for a residual cholesteatoma. Exclusion criteria: Excluded were patients with contra-indications for MR imaging.

N= 33 patients.

Prevalence: 67%

Mean age ± SD: 31 years (18), range 10-72.

Sex: 70% M

Other important characteristics: All patients were treated by CWU-type primary cholesteatoma repair. |

Describe index test: Non-EPI DWI MRI

Cut-off point(s): Residual cholesteatoma was confirmed if there was a focus of high signal intensity of any size in the mastoid or middle ear on non-EPI DWI b1000 sequence, in comparison to brain tissue/grey matter.

Comparator test[2]: NA

Cut-off point(s): NA.

|

Describe reference test[3]: Second look surgery

Cut-off point(s): not used.

|

Time between the index test and reference test: Patients were operated on after a median time span of 39 days following MR imaging.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? None.

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available)4:

MRI: Cholesteatoma was found in 22/33 patients (67%).

TN: 10 cases FN: 9 cases NPV: 53% (95%CI 32-73%) In 5/9 false negative cases, residual cholesteatoma was small (≤3 mm). Sizes of the latter false negatives ranged from 4 to 40mm

TP: 13 cases FP: 1 PPV: 93% (95% CI: 69-99%) False positive: small piece of cartilage. The smallest cholesteatoma correctly detected was 2 mm. Sens: 59% (39-77%) Spec: 91% (62-98%).

When the threshold was increased from 0 to 3 mm: improved sensitivity and NPV. Sens = 76% (95%CI 53-90%) Spec = 94% (95%CI 72-99%) NPV = 79% (95%CI 57-91%) PPV = remained unchanged. |

At the time of study, otoscopes were not in use.

Timing: Mean time between primary surgery and MRI was 259 days (SD 108).

Size: Cholesteatoma size varied between 0,5 and 40 mm (median 9,3 mm).

|

|

Allam, 2019 |

Type of study: prospective observational study

Setting and country: Egypt.

Funding and conflicts of interest: none declared. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with suspected recurrent or residual cholesteatoma after intact canal wall mastoidectomy.

Exclusion criteria: motion artefacts in the MRI.

N= 56 patients.

Prevalence: 38/56 = 68%

Mean age ± SD: 26.8 (14.5 years), range 16-45.

Sex: unknown

Other important characteristics: Canal wall mastoidectomy. |

Describe index test:

Non-echo-planar diffusion-weighted imaging and delayed contrast MRI of the petrous bone.

Cut-off point(s): Restricted diffusion with high signal intensity of a lesion on diffusion-weighted imaging was interpreted as recurrent cholesteatoma

Comparator test: NA

Cut-off point(s): NA

|

Describe reference test: Revision or second look surgery.

Cut-off point(s): not used.

|

Time between the index test and reference test: unknown.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? None. Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Recurrent cholesteatoma in 38/56 patients (68%).

Sensitivity: 94.7% Specificity: 94.4% PPV: 97.3% NPV: 89.5% For the first reading.

|

Timing: The mean time between primary surgery and MRI was not reported.

Size: The cholesteatoma size varied between 2.1 and 10.3 mm (mean 7.7 mm).

|

|

Foti, 2019 |

Type of study: prospective observational study

Setting and country: Italy

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients who previously underwent cholesteatoma surgery (CWU and CWD technique) and who received MRI.

Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded when they had a non-MRI-compatible pacemaker, incomplete MRI protocol, claustrophobia, or when there was no surgical correlation.

N=19

Prevalence: 16/24 ears (66.6%).

Mean age ± SD: 62.2 (range 34-80)

Sex: 57.9% M

Other important characteristics: 14/24 CWU technique 10/24 CWD technique |

Describe index test: Non-EPI MRI

Cut-off point(s): At MRI images, cholesteatoma was diagnosed in the presence of hyperintense tissue on DWI sequence, with absence of T1 hyperintensity and absence of contrast enhancement.

Comparator test: NA

Cut-off point(s): NA

|

Describe reference test: Revision or second look surgery.

Cut-off point(s): not used.

|

Time between the index test and reference test: not described.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? None

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

The analysis of MRI images demonstrated the presence cholesteatoma in 15/16 cases (93.7% sensitivity).

A FP case (87.5% specificity) was due to the presence of a squamous cell carcinoma, showing DWI hyperintensity but only subtle peripheral enhancement. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy of MRI were 93.7, 87.5, 93.7, 87.5, and 91.6%.

|

Timing: The mean time between primary surgery and MRI was not reported

Size: The cholesteatoma size varied between 5 and 22 mm (mean 11.1 mm).

|

|

Lips, 2019 |

Type of study: retrospective observational study

Setting and country: academic hospital, NL

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported.

|

Inclusion criteria: Only patients evaluated for the presence of residual/recurrent cholesteatoma in a postoperative setting were included. Eligible for the study were patients who had a definitive positive or negative surgical diagnosis of cholesteatoma before August 16.

Exclusion criteria: Patients suspected of a primary cholesteatoma were excluded. total of 16 patients were excluded due to the following reasons: inaccurate or incomplete MRI protocol (n = 9), abundant artefacts because of dental braces (n = 1), alternative diagnosis (2 metastasis, 1 neurofibroma, 1 encephalocele, 1 neuroendocrine tumor and 1 Langerhans cell histiocytosis). N= 135 patients, 164 ears. 1.5T = 128 3.0T = 36

Prevalence: 1.5T = 77.3% 3.0T = 69.4%

Mean age ± SD: 1.5T = 29 (7 – 77) 3.0 T = 29 (6 - 70)

Sex: 1.5T = 62% male 3.0 T = 64% male

Other important characteristics: |

Describe index test: multi-shot turbo spin-echo DWI sequences (non-EPI DWI MRI).

Cut-off point(s): The diagnosis of cholesteatoma on MRI examination was based on the presence of restricted diffusion (marked DWI hyperintensity compared to brain tissue, with low ADC signal in the correspond- ing area) in the middle ear and/or mastoid on either the transversal or coronal non-EPI DWI sequence, unless the same lesion showed hyperintensity on T1 imaging, which strongly suggested cholesterol granuloma, fatty tissue or proteinaceous fluid

Comparator test: NA

Cut-off point(s): NA

|

Describe reference test: surgical diagnosis.

Cut-off point(s): not used

|

Time between the index test and reference test: Median age was 29 years (range 6–77 years), 31 years (6–77 years) for men and 28 (7–65 years) for women. A median of 107 days passed between the MRI scan and subsequent operation (range 5–2895 days).

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? None

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Of the 164 ears included in the study 124 had surgically confirmed residual/recurrent cholesteatoma (prevalence 75%). Forty ears were suspected of having cholesteatoma residue or recurrence based on the MRI examination, though were cholesteatoma free during surgical exploration.

At 1.5 T, sensitivity for the expert reader and fellow was 96% resp. 88%, specificity was 59% resp. 62%, PPV was 89% resp. 89%, NPV was 81% resp. 60%. At 3 T, sensitivity for the expert reader and fellow was 80% resp. 76%, specificity is 46% resp. 55%, PPV was 78% resp. 79%, NPV was 50% resp. 50%.

Non-EPI met T1 en T2: T1.5 (expert) Sens: 91% (83-95) PPV: 90% (83-95) NPV: 68% (49-83) T3 (expert): Sens: 72% (51-86) Spec: 46% (19-74) PPV:75% (54-89) NPV: 41% (19-68)

|

Timing: The mean time between primary surgery and MRI was not reported.

Size: The cholesteatoma size varied between 4 and 23 mm at 1.5T and 5 and 27 mm at 3.0T (mean 9.0 mm for both field strengths).

|

|

Patel, 2018 |

Type of study: Prospective observational study.

Setting and country: Belgium

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. The authors declared that this study has received no financial support. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with a CWD mastoidectomy subsequently having at least one further DWI prior to further mastoid exploration.

Exclusion criteria: unknown.

N= 13 patients

Mean age ± SD: 16.7 years ( range 6.7-40.9)

Sex: 90% M

Other important characteristics: CWD mastoidectomy |

Describe index test: Non-echo planar DWI sequence (HASTE-DWI).

Cut-off point(s): A diagnosis of cholesteatoma was made if the lesion demonstrated a high signal on the b0 and b1000 images and a low signal on the ADC map and T1-weighted images.

Comparator test: NA

Cut-off point(s): NA

|

Describe reference test: surgery

Cut-off point(s): not used.

|

Time between the index test and reference test: DWI was requested pre-operatively in these patients to aid in surgical decision making.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? None

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Sensitivity: 93% Specificity: 60% PPV: 87% NPV: 75% Prevalence: 14/20 = 70%

|

Timing: The mean time between primary surgery and MRI was not reported.

Size: the variation in cholesteatoma size was not described. But a false negative case was found in a patient who has a 2 mm cholesteatoma. |

|

Osman, 2017 |

Type of study: prospective observational study

Setting and country: Egypt Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Patient with history of tympanomastoid surgery for cholesteatoma with clinical suspicion of recurrent cholesteatoma or infection during follow-up.

Exclusion criteria: patient with unclear operative his-tory, active infection or mastoid abscess.

N= 30 patients (31 ears)

Prevalence: 20/30 = 66.7%

Mean age ± SD: 27 years (range 9-45)

Sex: 20 females, 10 males.

Other important characteristics: CWD mastoidectomy (14 ears) or a CWU mastoidectomy (17 ears) |

Describe index test: SS-EP MR DWI

Cut-off point(s): the diagnosis of cholesteatoma was based on identifying area of restricted diffusion in the form of marked hyperintense signal in comparison with brain tissue on the b = (800, 1000) images of diffusion-weighted.

Comparator test: NA

Cut-off point(s): NA

|

Describe reference test: second look surgery

Cut-off point(s): not used.

|

Time between the index test and reference test: Mean time interval between the primary surgery and CT examination was 12-30 months. Patients were further assessed by MRI imaging on an average of 1-2 weeks after CT examination. Second look surgery was performed within 2-3 weeks after MR imaging.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? None

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Prevalence: 20/30 = 66.7%

Sensitivity: 100% Specificity: 90.0% PPV: 95.2% NPV: 100% |

Timing: The mean time interval between the primary surgery and CT examination was 12-30 months and all patients underwent MRI on an average of 1-2 weeks after CT examination.

Size: The size of recurrent/residual cholesteatoma mass was 7-15 mm. |

|

Bakaj, 2016 |

Type of study: prospective observational study

Setting and country: single center, Czech Republic

Funding and conflicts of interest: not described.

|

Inclusion criteria: patients after CWU operations requiring second look surgery and patients who underwent CWD procedures were included.

Exclusion criteria: not described.

N= 27 ears, 12 cases were second look after CWU, 15 cases were revision surgeries after CWU.

Prevalence: 67%

Mean age ± SD:

Sex:

Other important characteristics:

|

Describe index test: HASTE DWI MRI

Cut-off point(s): As cholesteatoma were considered soft tissue lesion with a low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, an increased signal intensity on T2 and a high signal intensity in comparison with brain tissue on non-EPI DWI. The size of the lesions in its maximal transversal diameter was determined on DWI sequence.

Comparator test: NA

Cut-off point(s): NA

|

Describe reference test: second look surgery

Cut-off point(s): not used.

|

Time between the index test and reference test: The interval between MR examination and surgery was 0–232, mean 33 days. Majority (56 %) of the patients were operated on within 3 weeks after MR.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? None

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Prevalence: In the whole sample of 27 operated ears, cholesteatoma was histologically diagnosed in 18 (67 %) cases

In the group of patients, 15/27 (55 %) were true positive, 8/27 (30 %) true negative, 1/27 (4 %) false positive and 3/27 (11 %) false negatives.

Three false negative cases were residual cholesteatomas after CWU surgery 2.5 mm, 2 mm and 1 mm in size. One false positive DWI MR scan in a revision surgery after CWD was caused by an artefact on air-bone interface.

The overall sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value of non-EPI DWI for this disease were 83.3 %, 88.8 %, 93.8% and 72.7 % respectively |

Patient inclusion: Decision for the second look surgery was made by the surgeon on the basis of findings at the first stage surgery and on clinical follow-up (19, 20), for the revision surgery after CWD mastoidectomy on postoperative clinical findings or DWI MR results. Indication for a revision surgery after CWD in patients with a complete cavity closure were made on positive DWI MR finding.

Timing: second look after CWU was performed 9-14 months after the initial operation. Revison surgery after CWD, performed 12-248 *mean 72) months after the primary surgery.

Size: The detected cholesteatomas had an average size of 9 mm, the smallest diameter was 3 mm and the largest was 23 mm. |

|

Lecler, 2015 |

Type of study: prospective observational study Setting and country: monocentric study in a tertiary academic referral center, France

Funding and conflicts of interest: None reported. |

Inclusion criteria: All consecutive children with cholesteatoma requiring second look surgery and managed in our institution between June and October 2010 were retrospectively included.

Exclusion criteria: not described.

N= 24

Prevalence: 41,6%

Mean age ± SD: 10.5 years (range 4-18)

Sex: 22 males, 2 females

Other important characteristics: |

Describe index test:

SE-DW

Cut-off point(s): Criteria for diagnosis of residual cholesteatoma was very high signal intensity in the middle ear or in the mastoid cavity on DWI sequence compared with brain tissue, corresponding to restricted diffusion on ADC maps.

Comparator test: NA

Cut-off point(s): NA

|

Describe reference test: second look surgery with histological conformation.

Cut-off point(s): not used.

|

Time between the index test and reference test: MRI to surgery delay was very short: less than a week for 15 patients (63%) and over 2 weeks for only 5 patients (21%). The mean delay was 12.8 days.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? None

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Prevalence: 41,6%

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of MRI were of 40%, 86%, 67%, and 67%, respectively, for the first observer and 30%, 86%, 60%, and 63%, respectively, for the second observer. Interobserver agreement was substantial (k = 0.647).

|

Timing: MR imaging was programmed 12 months after initial surgery.

Size: the cholesteatoma size varied between 0 and 8 mm (median 2 mm). |

|

Nash, 2015 |

Type of study: prospective observational study

Setting and country: UK

Funding and conflicts of interest: None to declare. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with post-operative cholesteatoma.

Exclusion criteria: Patients without operative findings.

N= 158

Prevalence: 85/158 = 54%

Mean age ± SD: 38.3 years (range 18.1-76.0)

Sex: 46.3% male

Other important characteristics: 104 adults, 54 children. |

Describe index test: HASTE DW-MRI

Cut-off point(s): not used.

Comparator test: NA

Cut-off point(s): NA

|

Describe reference test: Operative findings

Cut-off point(s): not used.

|

Time between the index test and reference test: not described

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? 5 cases, 162 scans.

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Operative findings were not available. |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Adults: Sens: 91% Spec: 85% PPV: 88% NPV: 89%

Children: Sens: 97% Spec: 95% PPV: 97%: NPV: 95% |

Timing: The mean time interval between primary surgery and MRI was not described

Size: The average size of detected cholesteatomas was not reported. |

|

Garrido, 2014 |

Type of study: prospective observational study

Setting and country: Spain

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: patients with clinical suspicion of recurrent cholesteatoma during follow-up after previous surgery.

Exclusion criteria: not described.

N= 27

Prevalence: 21/27 = 77.8%

Mean age ± SD: not described.

Sex: not described.

Other important characteristics: |

Describe index test: Non-EPI DW-MRI

Cut-off point(s): The criteria for the diagnosis of cholesteatoma at non-EPI DWI MRI was based on the evidence of a hyperintense middle ear and/or mastoid lesion, compared with the signal intensity of the brain, on b=0 s/mm² images that persists or increases on high b value (800 s/mm²) images.

Comparator test: NA

Cut-off point(s): NA

|

Describe reference test: surgical findings + histological confirmation.

Cut-off point(s): not used.

|

Time between the index test and reference test: not reported.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? None.

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Prevalence: 21/27 = 77.8%

TP: 21 FP: 2 TN: 4 FN: -

Sens: 1 Spec: 0.667 PPV: 0.913 NPV: 1 |

Timing: The mean time interval between primary surgery and MRI was not described.

Size: The average size of detected cholesteatomas was not described. |

|

Lingam, 2013 |

Type of study: retrospective observational study

Setting and country: UK

Funding and conflicts of interest: None to declare. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with post-operative cholesteatoma who underwent HASTE DWI MRI prior to surgery.

Exclusion criteria: Contraindications for MRI.

N= 56 patients with 72 episodes.

Prevalence: 46/71 = 65% Mean age ± SD: Range: 6-74. Sex: 33 male, 23 women

Other important characteristics:

|

Describe index test: HASTE DW-MRI

Cut-off point(s): The presence of postoperative cholesteatoma on DW images was diagnosed qualitatively if the lesion had high signal intensity compared with brain tissue on images with a b value of 1000 sec/mm2 and a corresponding area of low signal.

Comparator test: NA

Cut-off point(s): NA

|

Describe reference test: Operative findings with histologic confirmation.

Cut-off point(s): not used.

|

Time between the index test and reference test: The median time interval between DW imaging and surgery was 5.4 months (interquartile range, 4.0 months).

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? 71 episodes.

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Substantial movement during the imaging with consequent misregistration of the images for accurate analysis to be performed. |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

The sensitivity and specificity for our subjective analysis was 0.91 (955% CI: 0.79, 0.97) and 0.88 (95% CI: 0.69, 0.97), respectively.

False negative findings were below 3 mm.

Prevalence: 46/71 = 65%

|

Timing: The mean time interval between primary surgery and MRI was not described.

Size: The average size of detected cholesteatomas was not described. |

|

Illica, 2012 |

Type of study: prospective observational study

Setting and country: Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria: patients previously treated surgically for cholesteatoma of the middle ear.

Exclusion criteria:

N = 5

Prevalence: 100%

Mean age ± SD: not described.

Sex: not described.

Other important characteristics:

|

Describe index test: HASTE DW-MRI

Cut-off point(s): A diagnosis of cholesteatoma was based on evidence of a hyperintense lesion in the middle ear or mastoid cavity at b-1000 on the HASTE DWI. Axial CISS sequences and coronal TSE T2W sequences were used for anatomical localization of the cholesteatomas observed during the HASTE DWI sequence.

Comparator test: NA

Cut-off point(s): NA.

|

Describe reference test: Surgery + histopathological examination.

Cut-off point(s): not used.

|

Time between the index test and reference test: not described.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? None

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): HASTE DWI MRI successfully detected all 5 recurrent lesions of cholesteatoma.

TP = 5 FP = 0 FN = 0 TN = 0