Antistolling

Uitgangsvraag

Hoe dient het antistollingsbeleid eruit te zien tijdens de behandeling van patiënten met veno-veneuze en veno-arteriële extracorporele membraanoxygenatie?

- Welk type antistollingsmiddel heeft de voorkeur bij de behandeling van veno-veneuze en veno-arteriële extracorporele membraanoxygenatie patiënten?

- Hoe dient de monitoring van de effecten van antistolling eruit te zien tijdens de behandeling van veno-veneuze en veno-arteriële extracorporele membraanoxygenatie patiënten?

Aanbeveling

Behandel extracorporele membraanoxygenatie (ECMO) patiënten bij voorkeur met ongefractioneerde heparine.

Leg, per ECMO centrum, vast op welke wijze de antistolling wordt gemonitord en welke waarden men nastreeft.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Type antistollingsmedicatie

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de effectiviteit van alternatieve antistollingsmiddelen ter vervanging van ongefractioneerde heparine bij volwassen patiënten die VV- of VA-ECMO behandeling ondergaan. Daartoe werden drie vergelijkingen gemaakt: 1) bivalirudine versus ongefractioneerde heparine, 2) argatroban versus ongefractioneerde heparine, en 3) laagmoleculairgewicht heparine (LMWH) versus ongefractioneerde heparine. Er zijn één systematische review en drie retrospectieve cohortstudies geïncludeerd die deze drie vergelijkingen hebben onderzocht. Alle geïncludeerde studies betroffen retrospectieve cohortstudies.

Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat mortaliteit kunnen geen conclusies worden getrokken vanwege de zeer lage bewijskracht. De overall bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten is dan ook zeer laag. Dit wordt voornamelijk veroorzaakt door imprecisie door een breed betrouwbaarheidsinterval rondom te puntschatter, dan wel het niet halen van de optimale steekproefgrootte.

De belangrijke uitkomstmaten kunnen maar zeer beperkt verdere richting geven aan de conclusies. Er kunnen geen conclusies worden getrokken over de uitkomstmaten grote bloedingen, patiënt-gerelateerde en pomp-gerelateerde trombose vanwege een zeer lage bewijskracht, met uitzondering van pomp-gerelateerde trombose voor vergelijking 1 (bivalirudine versus ongefractioneerde heparine). Voor deze uitkomstmaat en vergelijking lijkt het risico op in-circuit trombose verlaagd wanneer bivalirudine wordt gegeven. De bewijskracht hiervoor was laag. De lage tot zeer lage bewijskracht werd veelal veroorzaakt door imprecisie rondom de puntschatter door het overschrijden van de klinisch relevante grenzen/zeer wijde betrouwbaarheidsintervallen, of door tegenstrijdige resultaten. In sommige gevallen werd tevens de optimale steekproefgrootte niet gehaald. Daarnaast hadden sommige studies een hoog risico op vertekening, waar in sommige gevallen ook voor is afgewaardeerd. Ten aanzien van het verschil in effectiviteit van anti-stollingsmedicatie bestaat een kennislacune.

Heparine is het meest gebruikte middel voor antistolling van patiënten aan de ECMO. Voordelen zijn de uitgebreide ervaring met het middel, de mogelijkheid tot titreren, de reversibiliteit middels protamine, de korte werkingsduur en de lage kosten.

Er zitten echter enkele nadelen aan het gebruik van heparine, zoals de afhankelijkheid van antitrombine en de binding aan circulerende eiwitten, welke de farmacokinetiek en individuele respons bepalen. Daarnaast kan een heparine-geïnduceerde trombocytopenie (HITT) optreden in < 5% (Jiritano 2020). Dit laatste is in de praktijk momenteel één van de belangrijkste redenen om over te gaan op een ander anticoagulantium in plaats van heparine. De alternatieven voor heparine, te weten bivalirudine, argatroban en LMWH, hebben zo ook elk hun specifieke nadelen, zoals het gebrek aan specifieke monitoring, het gebrek aan antidota en hogere kosten.

Monitoring

Hoewel niet systematisch onderzocht, wordt naast het type medicament voor antistolling het praktisch belang van monitoring van antistolling door de werkgroep onderkend. Het effect van de behandeling met antistolling dient gemonitord te worden om de balans te bepalen tussen bloeding en stolling waardoor de dosering aangepast kan worden. Er is geen gouden standaard voor het monitoren voor antistolling. Er wordt gestreefd naar een voldoende ontstolling van het extracorporele systeem zonder (grote) bloedingen bij de patiënt. De behandelstrategie voor de individuele patiënt bestaat uit het afwegen van de inflammatoire status, bijkomend orgaanfalen, trombocytenfunctie en de kans op bloeding en stolling. De behandeld arts moet de resultaten van de monitoring wegen in het licht van de patiënt en het circuit qua kans op complicaties. Bij een bloedende patiënt kan (veilig) gekozen worden voor een (tijdelijke) run zonder antistolling. Ook kan het circuit gewisseld worden in het geval van stolling in de oxygenator in het geval van een run zonder antistolling, terwijl een grote bloeding soms desastreuze gevolgen voor de patiënt kan hebben. Routinematige behandeling zonder antistolling is niet onderzocht. Tijdelijk staken van de antistolling vanwege een procedure of bloeding wordt vaak toegepast in de praktijk, maar er zijn geen data om de duur en risico´s hiervan in te schatten.

De activated clotting time (ACT) is vanuit historisch perspectief de eerste keuze voor de monitoring van heparine, maar in de huidige praktijk wordt deze test buiten de OK en HCK weinig meer gebruikt. De activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) wordt van oudsher gebruikt om de behandeling met heparine te monitoren op de IC. Er wordt gestreefd naar een 1.5-2.5x verlenging van de baseline aPTT, maar deze waarde is niet bevestigd in een RCT die is uitgevoerd in een ECMO populatie. Als alternatief voor de aPTT kan gekozen worden voor de Anti-Xa bepaling. Anti-Xa gebaseerde monitoring zou de uitkomsten mogelijk gunstig kunnen beïnvloeden door een verlaagd risico op bloeding zonder groter risico op stolling (Willems 2021). Het is belangrijk om de anti-Xa essay in het eigen centrum goed te kennen (toevoeging van exogeen antitrombine of aanwezigheid van dextran sulfaat in het reagens). De equivalente waarde van anti-Xa ligt tussen de 0.35-0.7 IU/ml (Levine, 1994). Een systematische review die het verschil in effect tussen aPTT en anti-XA onderzocht voor de uitkomst van bloeding en trombose rapporteert geen verschil in uitkomst van bloeding of trombose in het monitoren van therapeutische UFH met in de uitkomst van bloeding of trombose (Swaygim 2021).

Andere monitoringsmethoden zijn visco-elastische testen (whole-blood point of care testen), zoals thromboelastometrie (ROTEM) en thromboelastografie (TEG). Deze testen worden momenteel vooral gebruikt om de toediening van bloedproducten en stollingsfactoren te sturen bij bloedingen in het kader van (hart)chirurgie en na trauma, en niet zo zeer in de monitoring van antistolling bij ECMO.

De werkgroep heeft niet systematisch onderzocht welke mate van antistolling moet worden nagestreefd. Een internationale richtlijn over het gebruik van antistolling adviseert om heparine te doseren op geleide van anti Xa streef 0,3-0,7 IU/ml of op aPTT van 1.5-2.5x verlenging van de baseline aPTT (Helms 2022).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

ECMO is een behandeling die gepaard gaat met een hoge mortaliteit. Vanuit patiëntenperspectief is het van belang om de kans op overleving te optimaliseren. Bij het gebruik van antistolling is het voor de patiënt van belang dat de juiste balans tussen bloeding en stolling wordt gevonden. Het type antistolling lijkt hierin geen belangrijke rol te spelen. De gevolgen van een majeure bloeding zijn hoogstwaarschijnlijk met meer gevolgen voor de patiënt dan die van stollingsprobleem. Het is van belang om het doel van antistolling en de bijbehorende risico’s met patiënt en/of naasten te bespreken.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De behandeling met antistolling is qua kosten in het licht van alle gemaakte kosten van een patiënt aan de ECMO zeer beperkt.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De meeste centra zullen reeds een lokaal protocol voor het gebruik van antistolling hebben. Een lokaal protocol is naar mening van de werkgroep van belang om de variatie in behandeling en monitoring binnen het centrum te beperken. Er worden geen problemen verwacht t.a.v. de aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Door de afwezigheid van sterk bewijs voor de effectiviteit van alternatieven van heparine, heeft de werkgroep de voorkeur om heparine de eerste keuze te laten zijn. De uitgebreide ervaring met het middel, de mogelijkheid tot titreren, de reversibiliteit middels protamine, de korte werkingsduur en de lage kosten zijn hier argumenten voor. In individuele gevallen zoals bij patiënten waarbij een HITT ontstaat kan gekozen worden voor een alternatief middel, zoals bivalirudine, argatroban of laag-moleculaire heparines.

De werkgroep is van mening dat elk ECMO centrum lokaal vast zou moeten leggen in een protocol op welke wijze de antistolling wordt gemonitord en welke waarden men nastreeft.

De werkgroep adviseert een aPTT van 1.5-2.5x verlenging van de baseline aPTT of anti Xa 0,3-0,7 bij het gebruik van heparine op de IC indien de patiënt geen contra-indicaties voor therapeutische antistolling heeft (ref Helms 2022). Voor ARDS patiënten die behandeld worden met VV-ECMO kan overwogen worden om een lager target te hanteren (aPTT 40-55 seconden of anti Xa 0.2-0.3 IU/ml bij de behandeling met heparine (Combes, 2018).

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Anticoagulation is necessary for most patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) to prevent circuit clotting. As a result, bleeding is the most common complication in patients on ECMO. Anticoagulation during ECMO has to balance normal hemostasis in the critical ill patient with changes due to the interactions between the patient and the ECMO circuit, and the inflammatory responses of the patient to illness and to the ECMO circuit.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Comparison 1: bivalirudin versus UFH

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of bivalirudin on mortality, major bleeding, minor bleeding and patient-related thrombosis when compared with unfractionated heparin in patients on VV- or VA-ECMO.

Source: M’Pembele, 2022; Uricchio, 2022. |

|

Low GRADE |

Bivalirudin may reduce in-circuit thrombosis when compared with unfractionated heparin in patients on VV- or VA-ECMO.

Source: M’Pembele, 2022; Uricchio, 2022. |

Comparison 2: argatroban versus UFH

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of argatroban on mortality, major bleeding, minor bleeding, patient-related thrombosis and in-circuit thrombosis when compared with unfractionated heparin in patients on VV- or VA-ECMO.

Source: M’Pembele, 2022. |

Comparison 3: LMWH versus UFH

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of low-molecular weight heparin on mortality, major bleeding, patient-related thrombosis and in-circuit thrombosis when compared with unfractionated heparin in patients on VV- or VA-ECMO.

Source: Wiegele, 2022; Piwowarczyk, 2021. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

M’Pembele (2022) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate clinical outcomes in patients treated with heparin compared to different direct thrombin inhibitors (DTI) during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). A systematic search was conducted in multiple medical libraries (Pubmed/Medline, Cochrane library, CINAHL, Embase) from 18th August 2021 to 20th January 2022. Pediatric and adult patients treated with veno-arterial or veno-venous ECMO were included. DTI were divided into bivalirudin and argatroban. A total of eighteen retrospective cohort studies were included. For the current summary of literature, only ten out of eighteen studies were included (see evidence table for reasons). Note that Seelhammer (2021) (M’Pembele, 2022) included children and adults, but did make a distinction between those groups. Therefore, data on adults was separately subtracted from the individual studies. Follow-up time was not reported. Six of the ten studies had a high risk of bias, and four studies had a low risk of bias.

In addition to the studies described in M’Pembele (2022), three individual studies were selected. One study (Uricchio, 2022) was published after the publication date of M’Pembele (2022), and two studies (Wiegele, 2022; Piwowarczyk, 2021) comparing low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH) with unfractionated heparin (UFH), who were not included in the review of M’Pembele (2022).

Wiegele (2022) conducted a retrospective observational cohort study to evaluate the use of enoxaparin as an alternative to unfractionated heparin in adult COVID-19 patients with respiratory failure, who were treated with ECMO. A total of 98 patients were evaluated, of whom 62 patients had received enoxaparin and 36 UFH. Outcome measures of interest were clinically relevant thromboembolic events, major bleeding complications, and laboratory parameters. Follow-up time was not reported. The study had a high risk of bias due to issues with confounding assessment and analysis and provided no information on co-interventions.

Piwowarczyk (2021) conducted a retrospective observational cohort study to evaluate the safety and feasibility of anticoagulation with subcutaneous nadroparin compared with unfractionated heparin during veno-venous ECMO in patients. A total of 67 patients were evaluated, of whom 35 received nadroparin and 32 received UFH. Outcomes of interest were thrombotic complications and number of bleeding and life-threatening bleeding events. The follow-up period ended at the time of death or discharge from ICU. The study had a high risk of bias due to issues with confounding assessment and analysis and provided no information on co-interventions.

Uricchio (2022) conducted a retrospective observational cohort study to evaluate differences in efficacy and safety outcomes with bivalirudin compared to UFH in patients with cardiogenic shock requiring Veno-arterial ECMO. A total of 143 patients were evaluated, from whom 54 received bivalirudin, and 89 received UFH. Outcomes of interest were ECMO-associated thrombotic events normalized to duration of ECMO support, major bleeding (per ELSO criteria). The study had a high risk of bias due to issues with confounding assessment and analysis and provided no information on co-interventions. Also, the specific follow-up time was not reported, and it was not clear whether the endpoints were present at the start of the study.

Table 1. An overview of the included studies

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Comparison 3: low-molecular-weight heparin versus unfractionated heparin |

||||||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|||||

* Study included in M’Pembele (2022)

** Veno-venous cannulation accounted for the majority of patients in both groups, and veno-arterial or veno-veno-arterial, as used in situations of combined cardiac and respiratory failure, for the remainder.

Abbreviations: N.R., not reported; ECMO, extracorporeal life support; aPTT, Activated Partial Thromboplastin Clotting Time.

N.B. Only adult patients were included. Results from Seelhammer (2021) were subtracted from the original study publication to obtain data of only adult patients.

Results

Mortality

Comparison 1: bivalirudin versus UFH

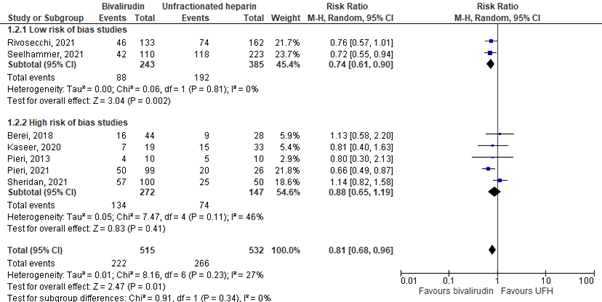

Seven studies in M’Pembele (2022) reported in-hospital mortality. As there was inconsistency among the results and five out of seven studies had a high risk of bias (Berei, 2018; Kaseer, 2020; Pieri, 2013; Pieri, 2021; Sheridan, 2021), sensitivity analyses were performed. For this outcome, the results from both subgroups are depicted, but the level of evidence will only be assessed for the results from the studies with a low risk of bias as the pooled RR from the low risk of bias studies differs from the overall pooled RR including also the studies with a high risk of bias.

The meta-analysis is shown in Figure 1. The subgroup with studies with a low risk of bias showed that a total of 88 out of 243 (36.2%) patients died in the bivalirudin group, versus 192 out of 385 (49.9%) patients in the UFH group. The pooled risk ratio (RR) was 0.74 (95% CI 0.61 to 0.90). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of the bivalirudin group.

Figure 1. In-hospital mortality; bivalirudin versus UFH.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; UFH: unfractionated heparin.

Comparison 2: argatroban versus UFH

Two studies in M’Pembele (2022) reported in-hospital mortality. The results are depicted in table 2. Both studies reported a clinically relevant lower mortality in the argatroban group.

Table 2. In-hospital mortality; argatroban versus UFH.

|

Study |

Argatroban Events/total |

UFH Events/total |

Risk ratio (95% CI) |

|

Cho, 2021 |

1/11 (9%) |

5/24 (21%) |

0.44 (0.06 to 3.31) |

|

Fisser, 2021 |

9/39 (23%) |

31/78 (40% |

0.58 (0.31 to 1.10) |

CI: confidence interval; UFH: unfractionated heparin.

Comparison 3: LMWH versus UFH

Wiegele (2022) reported mortality during oxygenation. In the enoxaparin group, 20 out of 62 patients (32.3%) died, versus 10 out of 36 patients (27.8%) in the UFH group. The RR was 1.16 (95% 0.61 to 2.20), in favor of UFH. This was considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Bleeding complications

1. Major bleeding

Comparison 1: bivalirudin versus UFH

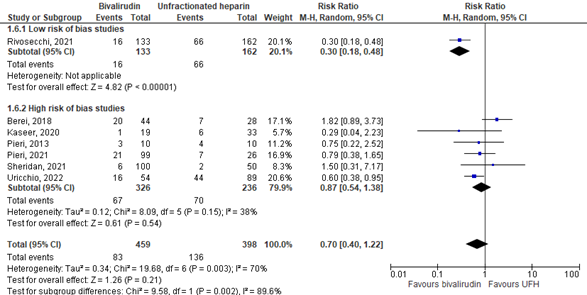

Uricchio (2022) and six studies in M’Pembele (2022) reported major bleeding. As there was inconsistency among the results, and Uricchio (2022) and five studies in M’Pembele (2022) had a high risk of bias (Berei, 2018; Kaseer, 2020; Pieri, 2013; Pieri, 2021; Sheridan, 2021), sensitivity analyses were performed. For this outcome, the results from both subgroups are depicted, but the level of evidence will only be assessed for the results from the study with a low risk of bias as the pooled RR from the low risk of bias studies differs from the overall pooled RR including also the studies with a high risk of bias.

The results are pooled in Figure 2. In the low risk of bias subgroup, Rivosecchi (2021)(M’Pembele, 2022) reported major bleeding in 15 out of 133 patients (11.3%) in the bivalirudin group, versus in 66 out of 162 patients (40.7%) in the UFH group. The RR was 0.30 (95% CI 0.18 to 0.48). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of the bivalirudin group.

Figure 2. Major bleeding; bivalirudin versus UFH.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; UFH: unfractionated heparin.

Comparison 2: argatroban versus UFH

Two studies in M’Pembele (2022) reported major bleeding. The results are depicted in table 3. The results were inconclusive.

Table 3. Major bleeding; argatroban versus UFH.

|

Study |

Argatroban Events/total |

UFH Events/total |

Risk ratio (95% CI) |

|

Cho, 2021 |

1/11 (9%) |

2/24 (8%) |

1.09 (0.11 to 10.79) |

|

Fisser, 2021 |

27/39 (69%) |

63/78 (81%) |

0.86 (0.68 to 1.08) |

CI: confidence interval; UFH: unfractionated heparin.

Comparison 3: LMWH versus UFH

Wiegele (2022) reported the number of patients with major bleeding and bleeding into a critical organ (which was intracranial in all cases). Piwowarczyk (2022) reported the number of bleeding events and the number of life-threatening bleeding events. The results are depicted in Table 4. All RR’s were considered to be clinically relevant in favor of LMWH.

Table 4. Major bleeding; LMWH versus UFH.

|

Study |

Outcome |

LMWH Events/total (%) |

UFH Events/total (%) |

Risk ratio (95% CI) |

|

Wiegele (2022) |

Number of patients with major bleeding |

7/62 (11.3%) |

8/36 (22.2%) |

0.51 (0.20 to 1.28) |

|

Wiegele (2022) |

Bleeding into a critical organ |

1/62 (1.6%) |

5/36 (13.9%) |

0.12 (0.01 to 0.96) |

|

Piwowarczyk (2022) |

Number of bleeding events |

12/35 (34.3%) |

17/32 (53.1%) |

0.65 (0.37 to 1.13) |

|

Piwowarczyk (2022) |

Number of life-threatening bleeding events |

1/35 (2.8%) |

3/32 (9.3%) |

0.30 (0.03 to 2.78) |

CI: confidence interval; UFH: unfractionated heparin.

Thrombotic complications

Patient-related thrombosis

Comparison 1: bivalirudin versus UFH

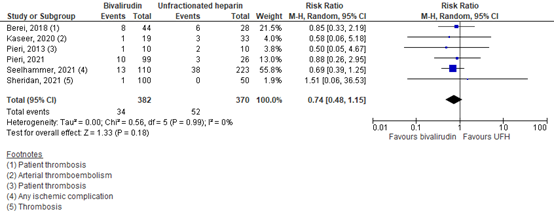

Six studies in M’Pembele (2022) reported patient-related thrombosis. The results are pooled in Figure 3. A total of 34 out of 382 patients (8.9%) reported patient-related thrombosis in the bivalirudin group, versus 52 out of 370 patients (14.1%) in the UFH group. The pooled RR was 0.74 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.15), in favor of bivalirudin. This was considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 3. Patient-related thrombosis; bivalirudin versus UFH.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; UFH: unfractionated heparin.

Moreover, Uricchio (2022) reported systemic thromboembolism, divided in ischemic stroke, deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism, and postdecannulation thrombus. Results are depicted in table 5. These outcomes could not be pooled, as patients who have had more than one of the outcomes in table 5 were likely to be counted more than one time and these patients could not be distracted from the data.

Table 5. Systemic thromboembolism outcome measures, reported in Urrichio (2022).

|

Outcome |

Bivalirudin Events/total |

UFH Events/total |

Risk ratio (95% CI) |

|

Ischemic stroke |

1/54 (x%) |

10/89 |

0.16 (0.02 to 1.25) |

|

DVT/PE |

1/54 |

5/89 |

0.33 (0.04 to 2.75) |

|

Postdecannulation thrombus |

4/54 |

5/89 |

1.32 (0.37 to 4.70) |

CI: confidence interval; UFH: unfractionated heparin; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; PE: pulmonary embolism.

Comparison 2: argatroban versus UFH

Two studies in M’Pembele (2022) reported patient-related thrombosis. The results are depicted in Table 6. The results were inconclusive.

Table 6. Patient-related thrombosis; argatroban versus UFH.

|

Study |

Argatroban Events/total |

UFH Events/total |

Risk ratio (95% CI) |

|

Cho, 2021 |

0/11 (0%) |

2/24 (8%) |

0.42 (0.02 to 8.02) |

|

Fisser, 2021 |

22/39 (56%) |

32/78 (41%) |

1.38 (0.94 to 2.02) |

CI: confidence interval; UFH: unfractionated heparin.

Comparison 3: LMWH versus UFH

Wiegele (2022) reported pulmonary embolism/deep vein thrombosis (incidental findings were not taken into account). A total of two out of 62 patients (3.2%) developed pulmonary embolism/deep vein thrombosis in the enoxaparin group, versus no patients in the UFH group. The risk difference was 0.03 (95% CI -0.03 to 0.09). This was not considered to be clinically relevant.

2. In-circuit thrombosis

Comparison 1: bivalirudin versus UFH

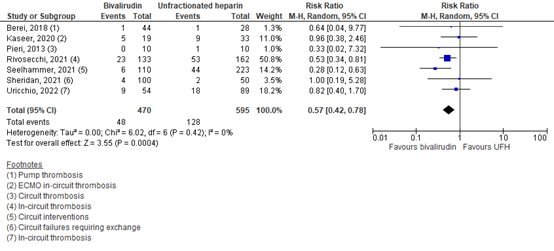

Uricchio (2022) and six studies in M’Pembele (2022) reported in-circuit thrombosis. The results are pooled in Figure 4. A total of 48 out of 470 patients (10.2%) reported in-circuit thrombosis in the bivalirudin group, versus 128 out of 595 patients (21.5%) in the UFH group. The pooled RR was 0.57 (95% CI 0.42 to 0.78), in favor of bivalirudin. This was considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 4. In-circuit thrombosis; bivalirudin versus UFH.

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; UFH: unfractionated heparin.

Comparison 2: argatroban versus UFH

Two studies in M’Pembele (2022) reported in-circuit thrombosis. The results are depicted in Table 7. Both studies show a clinically relevant difference in favor of argatroban.

Table 7. In-circuit thrombosis; argatroban versus UFH.

|

Study |

Argatroban Events/total |

UFH Events/total |

Risk ratio (95% CI) |

|

Cho, 2021 |

6/11 (55%) |

15/24 (63%) |

0.87 (0.47 to 1.63) |

|

Fisser, 2021 |

1/39 (3%) |

5/78 (6%) |

0.40 (0.05 to 3.31) |

CI: confidence interval; UFH: unfractionated heparin.

Comparison 3: LMWH versus UFH

Wiegele (2022) reported exchange of the oxygenator. Indications for oxygenator exchange included: extracorporeal membrane circulation stop due to acute occlusion; visible clots within the system; and / or a significant drop in platelet count plus fibrinogen levels as a sign of active consumption. In the enoxaparin group, exchange of the oxygenator occurred in three out of 62 patients (4.8%), versus in eight out of 36 patients (22.2%) in the UFH group. The RR was 0.22 (95% CI 0.06 to 0.77), in favor of enoxaparin.

Piwowarczyk (2022) reported the number of acute thromboses in the circuit. The number of acute thrombotic events in the nadroparin group was one out of 35 patients (2.8%), versus four out of 32 patients (12.5%) in the UFH group. The RR was 0.10 (95% CI 0.01 to 1.82), in favor of nadroparin.

Both RR’s were clinically relevant in favor of the LMWH group.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for all outcome measures was based on observational cohort studies and therefore started at low.

Mortality

Comparison 1: bivalirudin versus UFH

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘mortality’ (low risk of bias studies) was downgraded to very low, because the optimal information size has not been met (imprecision, -1).

Comparison 2: argatroban versus UFH

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘mortality’ was downgraded to very low, because the confidence intervals around the point estimates crossing the lower and upper boundary for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

Comparison 3: LMWH versus UFH

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘mortality’ was downgraded to very low, because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the lower and upper boundary for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

Major bleeding complications

Comparison 1: bivalirudin versus UFH

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘major bleeding’ (low risk of bias studies) was downgraded to very low, because the optimal information size has not been met (imprecision, -1).

Comparison 2: argatroban versus UFH

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘major bleeding’ was downgraded to very low, because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1).

Comparison 3: LMWH versus UFH

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘major bleeding’ was downgraded to very low, because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and the confidence intervals around the point estimates crossing the lower and upper boundary for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

Thrombotic complications

Patient-related thrombosis

Comparison 1: bivalirudin versus UFH

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘patient-related thrombosis’ was downgraded to very low, because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the both thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

Comparison 2: argatroban versus UFH

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘patient-related thrombosis’ was downgraded to very low, because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1).

Comparison 3: LMWH versus UFH

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘patient-related thrombosis’ was downgraded to very low, because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1).

In-circuit thrombosis

Comparison 1: bivalirudin versus UFH

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘in-circuit thrombosis’ was not downgraded and therefore remained low.

Comparison 2: argatroban versus UFH

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘in-circuit thrombosis’ was downgraded to very low, because of the very wide confidence intervals around the point estimate (the two boundaries of the confidence interval suggest very different inferences) (imprecision, -3).

Comparison 3: LMWH versus UFH

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘in-circuit thrombosis’ was downgraded to very low, because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and the wide confidence intervals around the point estimate (imprecision, -2).

Zoeken en selecteren

The working group decided to give priority to the first sub question as this question was the most relevant for clinical practice. Additional searches for the second question should be performed during updates of this module.

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effect of anticoagulation (bivalirudin, argatroban or low-molecular weight heparin) when compared with unfractionated heparin on mortality, with respect to bleeding complications and thrombotic complications in the treatment of adult patients on veno-venous (VV) and veno-arterial (VA) extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)?

P: Patients on VV- or VA-ECMO

I: Anticoagulation (bivalirudin, argatroban, or low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH))

C: Unfractionated heparin (UFH)

O: Mortality, major bleeding complications and thrombotic complications

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered mortality as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and major bleeding and thrombotic complications as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows: for major bleeding complications the definition of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) was used. Major bleeding was defined as clinically overt bleeding with a decrease in hemoglobin of at least 1,24 mmol/L (2 g/dl)/24 hours, or a transfusion requirement of ≥ 3 EH RBC over that same time period. Retroperitoneal bleedings, pulmonary or bleedings that involve the central nervous system, or require surgical intervention were also considered as major bleeding (Lequier, 2014). Thrombotic complications were defined as patient-related thrombosis (ischemic stroke, pulmonary embolism/deep vein thrombosis and post decannulation thrombus) and in-circuit thrombosis. For mortality, definitions in the studies were used.

The working group defined 0.95 > relative risk (RR) ≥ 1.05 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for mortality, and 0.91 > RR ≥ 1.10 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for bleeding and thrombotic complications.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2009 until 12-10-2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 413 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic reviews, RCTs and observational studies;

- Comparing anticoagulation (bivalirudin, argatroban or LMWH) with unfractionated heparin (UFH) in patients undergoing VA- or VV-ECMO;

- Reporting at least the following outcome measures: mortality, bleeding and/or thrombotic complications.

A total of 22 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, eighteen studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and four studies were included.

Results

Four studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Dhamija A, Thibault D, Fugett J, Hayanga HK, McCarthy P, Badhwar V, Awori Hayanga JW. Incremental effect of complications on mortality and hospital costs in adult ECMO patients. Perfusion. 2022 Jul;37(5):461-469. doi: 10.1177/02676591211005697. Epub 2021 Mar 26. PMID: 33765884.

- Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G, Demoule A, Lavoué S, Guervilly C, Da Silva D, Zafrani L, Tirot P, Veber B, Maury E, Levy B, Cohen Y, Richard C, Kalfon P, Bouadma L, Mehdaoui H, Beduneau G, Lebreton G, Brochard L, Ferguson ND, Fan E, Slutsky AS, Brodie D, Mercat A; EOLIA Trial Group, REVA, and ECMONet. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 24;378(21):1965-1975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800385. PMID: 29791822.

- Helms J, Frere C, Thiele T, Tanaka KA, Neal MD, Steiner ME, Connors JM, Levy JH. Anticoagulation in adult patients supported with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: guidance from the Scientific and Standardization Committees on Perioperative and Critical Care Haemostasis and Thrombosis of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2023 Feb;21(2):373-396. doi: 10.1016/j.jtha.2022.11.014. Epub 2022 Dec 22. PMID: 36700496.

- Jiritano F, Serraino GF, Ten Cate H, Fina D, Matteucci M, Mastroroberto P, Lorusso R. Platelets and extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation in adult patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020 Jun;46(6):1154-1169. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06031-4. Epub 2020 Apr 23. PMID: 32328725; PMCID: PMC7292815.

- Lequier L, Annich G, Al-Ibrahim O, et al. ELSO Anticoagulation Guidelines 2014. Available at: https://www.elso.org/ecmo-resources/elso-ecmo-guidelines.aspx.

- Levine MN, Hirsh J, Gent M, Turpie AG, Cruickshank M, Weitz J, Anderson D, Johnson M. A randomized trial comparing activated thromboplastin time with heparin assay in patients with acute venous thromboembolism requiring large daily doses of heparin. Arch Intern Med. 1994 Jan 10;154(1):49-56. PMID: 8267489.

- M'Pembele R, Roth S, Metzger A, Nucaro A, Stroda A, Polzin A, Hollmann MW, Lurati Buse G, Huhn R. Evaluation of clinical outcomes in patients treated with heparin or direct thrombin inhibitors during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb J. 2022 Jul 28;20(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12959-022-00401-2. PMID: 35902857; PMCID: PMC9330661.

- Piwowarczyk P, Borys M, Kutnik P, Szczukocka M, Sysiak-S?awecka J, Szu?drzy?ski K, Ligowski M, Drobi?ski D, Czarnik T, Czuczwar M. Unfractionated Heparin Versus Subcutaneous Nadroparin in Adults Supported With Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: a Retrospective, Multicenter Study. ASAIO J. 2021 Jan 1;67(1):104-111. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001166. PMID: 32404610.

- Seelhammer TG, Bohman JK, Schulte PJ, Hanson AC, Aganga DO. Comparison of Bivalirudin Versus Heparin for Maintenance Systemic Anticoagulation During Adult and Pediatric Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Crit Care Med. 2021 Sep 1;49(9):1481-1492. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005033. PMID: 33870916.

- Swayngim R, Preslaski C, Burlew CC, Beyer J. Comparison of clinical outcomes using activated partial thromboplastin time versus antifactor-Xa for monitoring therapeutic unfractionated heparin: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2021 Dec;208:18-25. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2021.10.010. Epub 2021 Oct 15. PMID: 34678527.

- Uricchio MN, Ramanan R, Esper SA, Murray H, Kaczorowski DJ, D'Aloiso B, Gomez H, Sciortino C, Sanchez PG, Sappington PL, Rivosecchi RM. Bivalirudin Versus Unfractionated Heparin in Patients With Cardiogenic Shock Requiring Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2023 Jan 1;69(1):107-113. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001723. Epub 2022 Apr 11. PMID: 35412480.

- Wiegele M, Laxar D, Schaden E, Baierl A, Maleczek M, Knöbl P, Hermann M, Hermann A, Zauner C, Gratz J. Subcutaneous Enoxaparin for Systemic Anticoagulation of COVID-19 Patients During Extracorporeal Life Support. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Jul 11;9:879425. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.879425. PMID: 35899208; PMCID: PMC9309531.

- Willems A, Roeleveld PP, Labarinas S, Cyrus JW, Muszynski JA, Nellis ME, Karam O. Anti-Xa versus time-guided anticoagulation strategies in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Perfusion. 2021 Jul;36(5):501-512. doi: 10.1177/0267659120952982. Epub 2020 Aug 29. PMID: 32862767; PMCID: PMC8216320.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

M’Pembele, 2022

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of cohort studies

Literature search up to January 2022

Note 1: only 10 out of the 18 studies included in M’Pembele et al. were included Note 2: outcome data from Seelhammer (2021) is retrieved from the original study publication, as this study included pediatric and adult patients.

A: Pieri, 2021 B: Sheridan, 2021 C: Seelhammer, 2021 D: Rivosecchi, 2021 E: Fisser, 2021 F: Cho, 2021 G: Kaseer, 2020 H: Macielak, 2019 I:Berei, 2018 J: Pieri, 2013

Study design: All studies were retrospective cohort studies

Setting and Country: All studies were single-center studies.

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research received no external funding. The authors declare no competing interests. |

Inclusion criteria SR: Published and unpublished randomized controlled trials, prospective or retrospective cohort studies and case–control studies investigating DTI (argatroban or bivalirudin) versus heparin in adult and pediatric VV- or VA-ECMO patients.

Exclusion criteria SR: Poster presentations, conference abstracts, systematic reviews and meta-analysis, studies not comparing DTI to heparin in ECMO patients, studies in which patients received DTI only as secondary anticoagulation strategy and studies not reporting on any of the endpoints were excluded.

10/18 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

Indication for ECMO: A: ARDS only B: CS: 58 Resp. fail.: 59 PE: 10 CPB weaning: 11 Others: 12 C: Post cardiotomy: 162 CS: 100 Resp. fail.: 86 eCPR: 69 Transplant: 5 D: Resp. fail.: 145 Pre/post-transplant: 108 Post cardiotomy: 20 Others: 22 E: ARDS only F: Not reported G: CS:15 ARDS:24 Transplant: 17 Others:1 H: Salvage: 61% CS: 46% ARDS:29% Resp. fail.: 29% CPB weaning: 23% Others: 12% I: CS: 51 Sepsis: 11 Resp. fail.: 4 Others: 6 J: Not reported

Mean age ± SD (unless otherwise reported) A: Not reported B: Total: 53 ±14.5 Hep.: 53 ±14 Biv.: 54 ±15 C: Not reported D: Hep.: 49 (36,61) Biv.: 49 (36,61) (median, IQR) E: Hep.: 56 (48,63) Arg.: 55 (46,61) (median, IQR) F: Total: 46 ±17 Hep.: 45 ±16 Arg.: 49 ±20 G: Total: 55 (18, 83) Hep.: 53 (21, 83) Biv.: 56 (18, 71) (median, IQR) H: Total: 52.8 ±14.2 Hep.: 51.4 ±14.0 Biv.: 57.9 ±13.8 I: Hep.: 55.9 ±13.1 Biv.: 55.2 ±15.2 J: Hep.: 54 ±12.7 Biv.: 59.5 ±14.4

Sex, male: A: Total: 93 B: Total: 106 Hep.: 32 Biv.: 74 C: Total: 265 Hep.: 183 Biv.: 82 D: Total: 146 Hep.: 95 Biv.: 81 E: Total: 80 Hep.: 51 Arg.: 29 F: Total: 22 Hep.: 15 Arg.: 7 G: Total: 37 Hep.: 25 Biv.: 12 H: Total: 127 I: Total: 47 Hep.: 18 Biv.: 29 J: Total: 16 Hep.: 9 Biv.: 7

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention:

A: Bivalirudin B: Bivalirudin C: Bivalirudin D: Bivalirudin E: Agratroban F: Argatroban G: Bivalirudin H: Bivalirudin I: Bivalirudin J: Bivalirudin |

Describe control:

A: Heparin B: Heparin C: Heparin D: Heparin E: Heparin F: Heparin G: Heparin H: Heparin I: Heparin J: Heparin |

End-point of follow-up: Follow-up times were not reported in the review.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported. However, authors of studies were contacted for missing data.

|

Mortality Defined as in-hospital mortality Events/total A: I: 50/99 C: 20/26 B: I: 57/100 C: 25/50 C: I: 42/110 C: 118/223 D: I: 46/133 C: 74/162 E: I: 9/39 C: 31/78 F: I: 1/11 C: 5/24 G: I: 7/19 C: 15/33 I: I: 16/44 C: 9/28 J: I: 4/10 C: 5/10 Pooled effect (random effects model): see literature summary.

Bleeding events Major bleeding events Events/total A: B: I: 6/100 C: 2/50 D: I: 16/133 C: 66/162 E: I: 27/39 C: 63/78 F: I: 1/11 C: 2/24 G: I: 1/19 C: 6/33 I: I: 20/44 C: 7/28 J: I: 3/10 C: 4/10 Pooled effect (random effects model): see literature summary.

Minor bleeding events Events/total A: I: 37/99 C: 15/26 B: I: 4/100 C: 4/50 E: I: 7/39 C: 8/78 F: I: 4/11 C: 13/24 I: I: 10/44 C: 7/28 J: I: 0/10 C: 2/10 Pooled effect (random effects model): see literature summary.

Thrombosis Patient-related thrombosis Events/total A: I: 10/99 C: 3/26 B: I: 1/100 C: 0/50 C: I: 13/110 C: 38/223 E: I: 22/39 C: 32/78 F: I: 0/11 C: 2/24 G: I: 1/19 C: 3/33 I: I: 8/44 C: 6/28 J: I: 1/10 C: 2/10 Pooled effect (random effects model): see literature summary.

Pump-related thrombosis Events/total B: I: 4/100 C: 2/50 C: I: 6/110 C: 44/223 Defined as circuit interventions D: I: 23/133 C: 53/162 E: I: 1/39 C: 5/78 F: I: 6/11 C: 15/24 G: I: 5/19 C: 9/33 I: I: 1/44 C: 1/28 J: I: 0/10 C: 1/10 Pooled effect (random effects model): see literature summary.

Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) Not reported. |

Author’s conclusion In conclusion, the present meta-analysis revealed that the use of DTI for anticoagulation in patients undergoing ECMO is associated with reduced in-hospital mortality as well as a reduced incidence of major bleeding and thrombotic events. Especially the use of bivalirudin showed positive efects on these outcomes in comparison with the standard therapy heparin. Before drawing fnal conclusions if DTI are really superior to the standard therapy heparin, well designed prospective (randomized) studies are urgently needed. Until these data are available, DTI may at least be regarded as a safe, efective and potentially benefcial strategy for anticoagulation in this cohort. |

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Wiegele, 2022 |

Type of study: investigator-initiated, retrospective, observational cohort study

Setting and country: Patient data were collected from six ICUs associated with three departments (Anesthesia, Intensive Care Medicine and Pain Medicine; Medicine I; Medicine III) the University Hospital Vienna.

Funding and conflicts of interest: This work was supported by departmental funds of the Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine Division of General Anesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine, Medical University of Vienna and the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute Digital Health and Patient Safety, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. |

Inclusion criteria: Adult (>18 years) COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory failure who had been admitted to one of the six ICUs for ECMO between 1 March 2020, and 20 May 2021.

Exclusion criteria: Patients whose extracorporeal circuit was anticoagulated by substances other than enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin, or in whom ECMO had been started before in-house ICU admission.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 62 Control: 36

Important prognostic factors: I: 57 (53-62.8) C: 57 (50.8-61)

Sex, male, n (%): I: 48 (77%) M C: 21 (58%) M

BMI, median (IQR) I: 29.2 (26.3-36.3) C: 30.9 (26.7-33.3)

SOFA score, median (IQR) I: 7.0 (6.0-8.0) C: 8.0 (7.0-9.0)

Length of ICU stay, median (IQR) I: 31 (19-46 days) C: 35 (23-59 days)

ICU mortality, n (%) I: 28 (45.2%) C: 11 (30.5%)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Subcutaneous administration of LMWH (enoxaparin), initiated at 4000 IU twice daily (aiming for anti-factor Xa peak levels of 0.3–0.5 IU/ml)

|

Continuous intravenous administration of UFH, adjusted based on activated partial thromboplastin time or anti-factor Xa levels, determined twice or three times daily and aiming for 50–60 s and / or 0.2–0.3 IU/ml |

Length of follow-up: Observation spans were defined as time from cannulation to either (i) cessation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, (ii) occurrence of a defined endpoint event, (iii) switching to a different anticoagulant drug, or (iv) surgery requiring transfusion of > two units of packed red blood cells within 24 h.

Loss-to-follow-up: In total, three patients were lost to follow-up due to transfer to another hospital.

Incomplete outcome data: Number not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality, n/total (%) Defined as mortality during oxygenation I: 20/62 (32.2%) C: 10/36 (27.8%*) * Note: fault in study, they reported 38.5%.

Bleeding events, n/total (%) Major bleeding I: 7/62 (11.3%) C: 8/36 (22.2%)

Bleeding into critical organ (intracranial) I: 1/62 (1.6%) C: 5/36 (13.9%)

Thromboembolic events, n (%) Pulmonary embolism I: 2 (3.2) C: 0 (0)

Deep vein thrombosis I: 0 (0) C: 0 (0)

Heparin induced thrombocytopenia I: 0 (0) C: 1 (2.8)

Exchange of oxygenator I: 3 (4.8) C: 8 (22.2)

|

|

|

Piwowarczyk, 2021 |

Type of study: retrospective, multicenter, observational study

Setting and country: five university hospitals in Poland

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. Funding is not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: patients who were supported with V-V ECMO between February 2014 and April 2019. Inclusion criteria for initiation of ECMO included: adult patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2)/fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) ratio (PFR) below 80 resistant to conventional treatment, potentially reversible cause of respiratory failure, and duration of mechanical ventilation not exceeding 10 days.

Exclusion criteria: Patients receiving anticoagulation, in addition to that required by ECMO, were not eligible for the study.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 35 Control: 32

Important prognostic factors: I: 50.3 (41-58.5) C: 46.8 (35-59)

Sex, male, n (%): I: 28 (80%) M C: 25 (78%) M

BMI, median (IQR) I: 28 (25.3-38.5) C: 26.7 (23.1-31)

Groups comparable at baseline? The UFH group had a somewhat lower BMI than the nadroparin group. Also, ECMO duration was longer.

|

A single dose of 5,700 international units (IU) of nadroparin (GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals, Poznan, Poland) subcutaneously once daily if body weight was below 100 kg. If patient body weight was 100–120 kg, 7,600 IU of nadroparin was injected, whereas patients weighing >120 kg received 9,500 IU

|

A continuous infusion to target the therapeutic APTT (60–80 s) or activated clotting time (ACT) (140–160 s), as advised by the ELSO Red Book. UFH was administered as a bolus (60–70 IU/kg) at initiation of therapy (maximum 5000 IU), followed by continuous intravenous infusion of 12–15 IU/kg/h.

|

Length of follow-up: The follow-up period ended at the time of death or discharge from ICU.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: There was missing data, but not reported how much.

|

Mortality Not reported.

Bleeding events Number of bleeding events, n (%) I: 12 (34%) C: 17 (53%)

Number of life-threatening bleeding events, n (%) I: 1 (2.8%) C: 3 (9.3%)

Thromboembolic events Thrombosis in circuit/number of acute thrombotic events, n (%) I: 1 (2.8%) C: 4 (12.5%)

Change in resistance to flow in the oxygenator during treatment I: 8.03% [−8.15 to 21.01] C: 11.6% [−5.7 to 38.3] |

|

|

Uricchio, 2022 |

Type of study: retrospective observational study

Setting and country: The UPMC Presbyterian Hospital

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. Funding is not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients greater than 18 years of age and supported with VA ECMO due to refractory cardiogenic shock without a previous requirement of cardiopulmonary bypass.

Exclusion criteria: - Patients requiring VV ECMO, VA ECMO for alternative indications or managed without anticoagulation - Patients that transitioned between anticoagulants defined as receiving greater than 6 hours of the comparative anticoagulant.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 54 Control: 89

Important prognostic factors: I: 53 (42-62) C: 53 (40-60)

Sex, male, n (%): I: 39 (72%) M C: 63 (71%) M

BMI, median (IQR): I: 30 (24-35) C: 28 (25-36)

Groups comparable at baseline? A greater number of patients in the bivalirudin cohort had arterial hypertension (65% vs. 35%, respectively; P = 0.001) and a previous major bleed before initiation of VA ECMO cannulation (16% vs. 2%, respectively; P = 0.003). Additionally, patients in the bivalirudin cohort had a longer median duration of VA ECMO when compared with the UFH cohort (128 [IQR, 63–187] hours vs. 88 [IQR, 51–144] hours; P = 0.12) |

Bivalirudin (for details see appendix 1 of the study)

|

UFH (for details see appendix 1 of the study)

|

Length of follow-up: Not reported.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality Not reported.

Bleeding events Major bleeding event, n (%) I: 16 (29%) C: 44 (49%)

Thromboembolic events Any thrombosis on ECMO, n (%) I: 11 (20%) C: 31 (35%)

In-circuit thrombosis, n (%) I: 9 (17%) C: 18 (20%)

Systemic thromboembolism, N (%): Ischemic stroke I: 1 (2%) C: 10 (11%) DVT/PE I: 1 (2%) C: 5 (6%) Postdecannulation thrombus I: 4 (7%) C: 5 (6%)

|

|

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

M’Pembele, 2022 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Unclear |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Risk of bias tables

|

Author, year |

Selection of participants

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population?

|

Exposure

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?

|

Outcome of interest

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study?

|

Confounding-assessment

Can we be confident in the assessment of confounding factors?

|

Confounding-analysis

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these confounding variables?

|

Assessment of outcome

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome?

|

Follow up

Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? In particular, was outcome data complete or imputed?

|

Co-interventions

Were co-interventions similar between groups?

|

Overall Risk of bias

|

|

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Low, Some concerns, High |

|

|

Wiegele, 2022 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Patient data were collected from six ICUs associated with three departments. Two investigators (DL, MM) extracted information from the IntelliSpace Critical Care and Anesthesia (ICCA; Philips Healthcare, Amsterdam, Netherlands) patient data management system by Structured Query Language.

|

Definitely yes

Reason: Data on anticoagulation were extracted from the patient data management system. |

Probably yes

Reason: Exclusion criteria were: |

Probably no

Reason: The study mentions that to avoid potential confounders, only patients with complete documentation of anticoagulant medication after in-house cannulation were included. However, only complete documentation of anticoagulation might not be enough. |

Probably no

Reason: Not reported. |

Probably yes

Reason: The same two investigators also performed automated screening both of the medical histories (for events predating the in-house ICU admissions) and of the daily clinical notes for keywords indicative of relevant thromboembolic or bleeding complications. |

Probably yes

Reason: Missing data was processed, but not mentioned how this was done. |

No information

|

HIGH (all outcome measures) |

|

T Piwowarczyk, 2021 |

Probably yes

Reason: No source was reported, only that patient data were obtained from five university hospitals in Poland. |

Probably yes

Reason: No source was reported, only that patient data were obtained from five university hospitals in Poland. |

Probably yes

Reason: Not specifically reported. However, all outcomes were assessed during the first 7 days of ECMO support. |

Probably no

Reason: Not reported. |

Probably no

Reason: Not reported. |

Probably yes

Reason: Circuits were inspected twice daily by the ECMO intensivist for signs of thrombotic scaling. General clinical data and bleeding signs were examined and documented every 12 hours. |

No information

Reason: No follow-up time reported. |

No information

|

HIGH (all outcome measures) |

|

Uricchio, 2022 |

Probably yes

Reason: Patients were identified through review of an internal ECMO database maintained by perfusion services at UPMC Presbyterian Hospital between January 2009 and February of 2021. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Anticoagulation protocol published. |

Probably no

Reason: Both primary and secondary endpoints were only evaluated after the initiation of either UFH or bivalirudin. However, it was not sure if these were present beforehand. |

Probably no

Reason: Not reported. |

Probably no

Reason: Covariates were put in the Cox proportional hazards model to control for. However, this was only done for the outcome measure ‘Time to thrombotic event’.

Citation from study: “Our study was conducted at a single center with established local protocols, and as such our results may not be able to be generalized nor extrapolated to all ECMO centers or other indications for VA-ECMO. However, this study does represent a homogenous cohort of patients that strengthen our findings and allows for a less confounding evaluation of thrombotic and bleeding complications of VA-ECMO.”

|

Probably yes

Reason: All relevant demographic and ECMO related variables were extracted from the internal ECMO database or obtained through review of the electronic medical record. We collected ECMO-associated systemic thrombosis (deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or ischemic stroke) as well as ECMO in-circuit thrombosis defined as a visible thrombosis on any portion of the ECMO circuit that was determined to require a change in either ECMO cannula tubing, pump, and/or oxygenator. Information regarding hemorrhagic events and blood product administration were also obtained through review of the electronic medical record, as well as a previous history of major bleeding defined as intracranial hemorrhage or hemodynamically significant gastrointestinal bleeding. |

No information

Reason: No follow-up time reported. |

No information

|

HIGH (all outcome measures) |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Berei TJ, Lillyblad MP, Wilson KJ, Garberich RF, Hryniewicz KM. Evaluation of Systemic Heparin Versus Bivalirudin in Adult Patients Supported by Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2018 Sep/Oct;64(5):623-629. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000691. PMID: 29076942. |

Also included in included systematic review |

|

Cho AE, Jerguson K, Peterson J, Patel DV, Saberi AA. Cost-effectiveness of Argatroban Versus Heparin Anticoagulation in Adult Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Patients. Hosp Pharm. 2021 Aug;56(4):276-281. doi: 10.1177/0018578719890091. Epub 2019 Dec 13. PMID: 34381261; PMCID: PMC8326861. |

Also included in included systematic review |

|

Fisser C, Winkler M, Malfertheiner MV, Philipp A, Foltan M, Lunz D, Zeman F, Maier LS, Lubnow M, Müller T. Argatroban versus heparin in patients without heparin-induced thrombocytopenia during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a propensity-score matched study. Crit Care. 2021 Apr 29;25(1):160. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03581-x. PMID: 33910609; PMCID: PMC8081564. |

Also included in included systematic review |

|

Giuliano K, Bigelow BF, Etchill EW, Velez AK, Ong CS, Choi CW, Bush E, Cho SM, Whitman GJR. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Complications in Heparin- and Bivalirudin-Treated Patients. Crit Care Explor. 2021 Jul 13;3(7):e0485. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000485. PMID: 34278315; PMCID: PMC8280085. |

Study does not meet the PICO, as patients were switched between heparin and bivalirudin

|

|

Kaseer H, Soto-Arenall M, Sanghavi D, Moss J, Ratzlaff R, Pham S, Guru P. Heparin vs bivalirudin anticoagulation for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Card Surg. 2020 Apr;35(4):779-786. doi: 10.1111/jocs.14458. Epub 2020 Feb 12. PMID: 32048330. |

Also included in included systematic review |

|

Krueger K, Schmutz A, Zieger B, Kalbhenn J. Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation With Prophylactic Subcutaneous Anticoagulation Only: An Observational Study in More Than 60 Patients. Artif Organs. 2017 Feb;41(2):186-192. doi: 10.1111/aor.12737. Epub 2016 Jun 3. PMID: 27256966. |

Wrong comparison (no UFH as control) |

|

Macielak S, Burcham P, Whitson B, Abdel-Rasoul M, Rozycki A. Impact of anticoagulation strategy and agents on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy. Perfusion. 2019 Nov;34(8):671-678. doi: 10.1177/0267659119842809. Epub 2019 May 6. PMID: 31057056. |

Also included in included systematic review |

|

Menk M, Briem P, Weiss B, Gassner M, Schwaiberger D, Goldmann A, Pille C, Weber-Carstens S. Efficacy and safety of argatroban in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome and extracorporeal lung support. Ann Intensive Care. 2017 Dec;7(1):82. doi: 10.1186/s13613-017-0302-5. Epub 2017 Aug 3. PMID: 28776204; PMCID: PMC5543012. |

pECLA does not fit the PICO, and no difference made between VV-ECMO and pECLA |

|

Pieri M, Agracheva N, Bonaveglio E, Greco T, De Bonis M, Covello RD, Zangrillo A, Pappalardo F. Bivalirudin versus heparin as an anticoagulant during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a case-control study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2013 Feb;27(1):30-4. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2012.07.019. Epub 2012 Oct 1. PMID: 23036625. |

Also included in included systematic review |

|

Ranucci M, Ballotta A, Kandil H, Isgrò G, Carlucci C, Baryshnikova E, Pistuddi V; Surgical and Clinical Outcome Research Group. Bivalirudin-based versus conventional heparin anticoagulation for postcardiotomy extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):R275. doi: 10.1186/cc10556. Epub 2011 Nov 20. PMID: 22099212; PMCID: PMC3388709. |

No difference made between children and adults. |

|

Rivosecchi RM, Arakelians AR, Ryan J, Murray H, Ramanan R, Gomez H, Phillips D, Sciortino C, Arlia P, Freeman D, Sappington PL, Sanchez PG. Comparison of Anticoagulation Strategies in Patients Requiring Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: Heparin Versus Bivalirudin. Crit Care Med. 2021 Jul 1;49(7):1129-1136. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004944. PMID: 33711003. |

Also included in included systematic review |

|

Seelhammer TG, Bohman JK, Schulte PJ, Hanson AC, Aganga DO. Comparison of Bivalirudin Versus Heparin for Maintenance Systemic Anticoagulation During Adult and Pediatric Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Crit Care Med. 2021 Sep 1;49(9):1481-1492. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005033. PMID: 33870916. |

Also included in included systematic review |

|

Sheridan EA, Sekela ME, Pandya KA, Schadler A, Ather A. Comparison of Bivalirudin Versus Unfractionated Heparin for Anticoagulation in Adult Patients on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2022 Jul 1;68(7):920-924. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001598. Epub 2022 Oct 19. PMID: 34669620. |

Also included in included systematic review |

|

Pieri M, Donatelli V, Calabrò MG, Scandroglio AM, Pappalardo F, Zangrillo A. Eleven Years of Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: From H1N1 to SARS-CoV-2. Experience and Perspectives of a National Referral Center. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2022 Jun;36(6):1703-1708. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2021.09.029. Epub 2021 Sep 24. PMID: 34686438; PMCID: PMC8461266. |

Also included in included systematic review |

|

Hasegawa D, Sato R, Prasitlumkum N, Nishida K, Keaton B, Acquah SO, Im Lee Y. Comparison of Bivalirudin Versus Heparin for Anticoagulation During Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2023 Apr 1;69(4):396-401. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001814. Epub 2022 Apr 10. PMID: 36194483. |

Meets the PICO, but another review was selected that had better characteristics (it was not certain if unfractionated heparin was used as a control, or LMWH, and the search strategy not very clearly described, this SR and meta-analysis also included children) |

|

Huang D, Guan Q, Qin J, Shan R, Wu J, Zhang C. Bivalirudin versus heparin anticoagulation in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Perfusion. 2023 Sep;38(6):1133-1141. doi: 10.1177/02676591221105605. Epub 2022 May 26. PMID: 35616224. |

Meets the PICO, but another review was selected that had better characteristics (this SR and meta-analysis also included children) |

|

Li DH, Sun MW, Zhang JC, Zhang C, Deng L, Jiang H. Is bivalirudin an alternative anticoagulant for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2022 Feb;210:53-62. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2021.12.024. Epub 2021 Dec 31. PMID: 35007937. |

Meets the PICO, but another review was selected that had better characteristics (this SR and meta-analysis also included children) |

|

Ma M, Liang S, Zhu J, Dai M, Jia Z, Huang H, He Y. The Efficacy and Safety of Bivalirudin Versus Heparin in the Anticoagulation Therapy of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Apr 14;13:771563. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.771563. PMID: 35496287; PMCID: PMC9048024. |

Meets the PICO, but another review was selected that had better characteristics (this SR and meta-analysis also included children) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 07-11-2024

De richtlijn zal modulair onderhouden worden in het cluster “Intensive Care” en frequent worden beoordeeld op de geldigheid van de aanbeveling vanaf 2026. Meer informatie over werken in clusters en modulair onderhoud vindt u hier.

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten die extracorporele membraanoxygenatie (ECMO) ondergaan.

Werkgroep

Dhr. dr. L.C. (Luuk) Otterspoor (voorzitter), cardioloog-intensivist, Catharina Ziekenhuis, Eindhoven; NVIC

Mw. dr. J.M.D. (Judith) van den Brule, cardioloog-intensivist, Radboudumc, Nijmegen; NVIC

Dhr. drs. C.V. (Carlos) Elzo Kraemer, internist-intensivist, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden; NVIC

Mw. dr. A. (Annemieke) Oude Lansink-Hartgring, internist-intensivist, Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen, Groningen; NVIC

Dhr. drs. J.E. (Jorge) Lopez Matta, longarts-intensivist, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden; NVALT

Dhr. dr. M. (Meindert) Palmen, cardiothoracaal chirurg, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden; NVT

Dhr. dr. K. (Kadir) Çaliskan, cardioloog, Erasmus Medisch Centrum, Rotterdam; NVVC

Dhr. dr. (Krischan) Sjauw (vanaf januari 2023), interventiecardioloog, St. Antonius Ziekenhuis, Nieuwegein; NVVC

Dhr. M.A. (Michel) de Jong, klinisch perfusionist, Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht, Utrecht; NeSECC

Dhr. drs. E. (Erik) Scholten, anesthesioloog-intensivist, St. Antonius Ziekenhuis, Nieuwegein; NVA

Mw. K.S.M. (Kimberley) Amatdasim (vanaf februari 2023), intensive care verpleegkundige, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht; V&VN

Mw. J. (Juul) van de Steeg (tot 30 oktober 2023), verpleegkundig specialist intensive- en medium care, St. Antonius Ziekenhuis, Nieuwegein; V&VN

Mw. J. (José) Joustra, patiëntvertegenwoordiger; FCIC/IC Connect

Klankbordgroep

Dhr. dr. F.J. (Erik) Slim, revalidatiearts, Ziekenhuis Rivierenland, Tiel; VRA

Mw. drs. M.P. (Marijn) Mulder, technisch geneeskundige en docent-onderzoeker, Universiteit Twente, Twente; NVvTG

Dhr. R. (Robert) van der Stoep, fysiotherapeut, Erasmus Medisch Centrum, Rotterdam; KNGF, NVZF

Met ondersteuning van

Mw. drs. I. (Ingeborg) van Dusseldorp, senior medisch informatiespecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

Mw. drs. F.M. (Femke) Janssen, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

Mw. dr. J.C. (José) Maas, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

Mw. drs. L.H.M. (Linda) Niesink-Boerboom, medisch informatiespecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Annemieke Oude Lansink - Hartgring |

Intensivist bij Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen |

Bestuurslid bij Stichting Venticare - vrijwilligersvergoeding |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Carlos Elzo Kraemer |

Internist-Intensivist volwassen IC, LUMC |

Geen |

Toegevoegd 24-1-24 |

Geen restricties |

|

Erik Scholten |

Anesthesioloog-intensivist st Antonius ziekenhuis |

Geen |

Deelgenomen aan de INCEPTION trial (rol: lokale onderzoeker, PI Antonius ziekenhuis; geen overkoepelend projectleider) |

Geen restricties |

|

Jorge E. Lopez Matta |

Longarts-Intensivist. Werkzaam als full time intensivist in het Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum. |

Longarts-intensivist in het LUMC: Betaald. Full time. Behalve regulier IC, ook actief betrokken bij het opstellen van protocollen en onderwijs rondom ECMO en point of care ultrasound. |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Jose Joustra |

Ervaringsdeskundige |

Communicatiemedewerker gemeente Purmerend |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Judith van den Brule |

Cardioloog-intensivist Radboudumc |

- |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Juul van de Steeg, vertrokken 30-10-2023 |

Verpleegkundig Specialist Intensive- en Medium Care |

Literatuur selecteren |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Kadir Çaliskan |

Cardioloog |

Werkgroep MCS |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Kimberley Amatdasim |

Intensive Care Verpleegkundige, Maastricht UMC+ |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Krischan Sjauw |

Interventiecardioloog Medisch Centrum Leeuwarden. |

Afgevaardigde NVVC - inhoudelijk voorzitter ZiN/Programma Uitkomstgerichte zorg, project "Samen beslissen in Acuut coronaire syndromen"; vacatie/uren vergoeding |

- 1. Industry initiated international trial Philips/Volcano: DEFINE-GPS trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04451044); Multi-center, prospective, randomized controlled study comparing PCI guided by angiography versus iFR Co-Registration using commercially available Philips pressure guidewires and the SyncVision co-registration system, employing an adaptive design study for interim sample size re-estimation; rol Nationale PI en local PI MCL; betaling trial patient fees aan Research afdeling Cardiologie/HAVA.

|

Geen restricties. Onderwerp van industrie gesponsorde onderzoek valt buiten bestek van de richtlijn. |

|

Luuk Otterspoor (voorzitter) |

Intensivist (50%) Cardioloog (50%), Catharina Ziekenhuis |

Geen |

1EURO-ICE Toegev (restricted grant, geen PI) INCEPTION. Deze werd deels gefinancierd door Getinge. ON SCENE trial, initiatiefnemer is Erasmus MC. |

Geen restricties |

|

Meindert Palmen |

Cardiothoracaal chirurg LUMC. Uit hoofde van deze functie leid ik het LVAD programma in het LUMC |

Geen. |

Cytosorbents voor inclusie patiënten cytosorb tijdens hartfalen studie. Zoals hierboven aangegeven komen alle financiële vergoedingen ten bate van het afdelingsfonds van de afdeling cardiothoracale chirurgie van het LUMC

|

Geen restricties. Onderwerp van industrie gesponsorde onderzoek valt buiten bestek van de richtlijn. |

|

Michel de Jong |

Klinisch perfusionist UMCU, betaald ( niet in loondienst maar vanuit de maatschap heartbeat)

|

LVAD specialist, betaald

|

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Erik Slim |

Revalidatiearts |

n.v.t. |

Geen |

Geen restricties

|

|

Marijn Mulder |

Docent/onderzoeker - Universiteit Twente (1.0 FTE) |

n.v.t. |

Betrokken bij research consultancy voor Maquet Critical Care, AB, maar krijg daarvoor geen persoonlijke vergoeding, deze wordt uitbetaald aan de universiteit.

De scope van dit onderzoeksproject valt buiten de scope van de richtlijn.

|

Geen restricties

|

|

Robert van der Stoep |

Fysiotherapeut Erasmus Medisch Centrum (36 uur per week, betaald) |

Gastdocent voor het Nederlands Paramedisch Instituut bij verschillende cursussen over fysiotherapie op de IC. (2 à 3 keer per jaar, betaald). |

Visual incentivised and monitored rehabilitation for early mobilisation in the Intensive Care Unit - ICMOVE

|

Geen restricties

|

|

Valentijn Schweitzer

NVMM heeft zich teruggetrokken uit klankbordgroep, omdat voor NVMM geen relevante modules zijn opgenomen in het definitieve raamwerk |

AIOS MMB |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties

|

|

Nelianne Verkaik, Vertrokken 22-11-2023

NVMM heeft zich teruggetrokken uit klankbordgroep, omdat voor NVMM geen relevante modules zijn opgenomen in het definitieve raamwerk |

Arts-microbioloog Erasmus MC |

Deelnemersraad Stichting Werkgroep Antibiotica Beleid onbetaald |

Intellectueel gewin in zin van meer kennis opdoen/expertise opbouwen omtrent antibiotica bij ECLS, zonder mogelijkheden voor vermarkting

|

Geen restricties

|

|

Femke Janssen |

Junior adviseur kennisinstituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties

|

|

José Maas |

Adviseur kennisinstituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties

|

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van Family and Patient Centered Intensive Care/IC Connect (FCIC/IC Connect), Harteraad en het Longfonds voor deelname aan de invitational conference. Een afgevaardigde van Family and Patient Centered Intensive Care/IC Connect (FCIC/IC Connect) nam deel aan de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan FCIC/IC Connect, Harteraad, het Longfonds en de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijnmodule is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd om te beoordelen of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Antistolling |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en zal daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die extracorporele membraanoxygenatie (ECMO) ondergaan. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door verschillende partijen/vertegenwoordigers via een invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs